Abstract

Adverse reactions to local anesthetics are usually a reaction to epinephrine, vasovagal syncope, or overdose toxicity. Allergic reactions to local anesthetics are often attributed to additives such as metabisulfite or methylparaben. True allergic reactions to amide local anesthetics are extremely rare but have been documented. Patients with true allergy to amide local anesthetics present a challenge to the dental practitioner in providing adequate care with appropriate intraoperative pain management. Often, these patients may be treated under general anesthesia. We report a case of a 43-year-old female patient that presented to NYU Lutheran Medical Center Dental Clinic with a documented history of allergy to amide local anesthetics. This case report reviews the use of 1% diphenhydramine with 1:100,000 epinephrine as an alternative local anesthetic and reviews the relevant literature.

Key Words: Diphenhydramine, Local anesthetic, Allergy, Lidocaine

Reports of adverse reactions to local anesthetics are usually attributed to a reaction to epinephrine, vasovagal syncope, or overdose toxicity. Patients may then interpret adverse reactions as an allergy to local anesthetic. True allergy to amide local anesthetics is considered to be rare.1

All injectable local anesthetics are composed of 3 different structural parts: (a) an aromatic or lipophilic portion, necessary for the drug to penetrate the lipid-rich nerve membrane; (b) an amino terminus, ensuring solubility in aqueous medium; and (c) an intermediate chain connecting the aromatic and amino termini. The latter structure divides the local anesthetic into 2 different groups: esters (-COO-) and amides (-NHCO-). Esters, such as procaine and tetracaine, are metabolized by plasma pseudocholinesterase.2 This group of dental local anesthetics is no longer available in dental cartridges. However, a nasal spray formulation to provide maxillary anesthesia containing 3% tetracaine and 0.05% oxymetazoline, a vasoconstrictor, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration on June 29, 2016, for a single restorative procedure on maxillary second premolars to central incisors. It has not been approved for root canals or extractions.3

Allergies to local anesthetics have been reported for ester-type local anesthetics. Hydrolysis of ester-type local anesthetics by cholinesterase results in the release of para-aminobenzoic acid, a known allergen, as a metabolite. However, recent pivotal studies of ester agents for US Food and Drug Administration approval and marketing claims report no cases of this phenomenon.3–6 Amide-type local anesthetics are metabolized in the liver and are essentially free from producing allergic phenomena.4–7 However, although they are rare, there have been documented cases of amide-type local anesthetic allergy.6,8

Additionally, local anesthetics may contain known allergens such as methylparaben and metabisulfite. Methylparaben is a bacteriostatic agent added to many multidose vials and is chemically related to para-aminobenzoic acid. Currently, methylparabens are no longer utilized in dental cartridges, as they are single-patient–use medications. However, metabisulfite is still an added antioxidant in all solutions containing epinephrine or levonordefrin.9

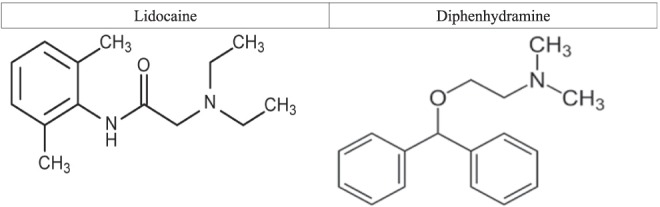

Patients with true local anesthetic allergies have been treated in the past with the use of antihistamines as a local anesthetic. Their use was initially described in 1939 by Rosenthal and Minard.10 Diphenhydramine's (DPH's) anesthetic properties are thought to be due to its similar structure to other neural blocking agents.11 DPH contains an aromatic ring, an intermediate chain, and an amino terminus in its molecular structure. Figure 1 compares the structures of lidocaine and DPH. For patients with local anesthetic allergies, DPH has been utilized in dermal anesthesia, podiatric surgery, and gastroenterologic, urologic, and anesthesiologic treatments.11–14 DPH has historically also been successfully used as a local anesthetic in dentistry. Welborn and Kane15 first reported use of DPH to perform a mandibular block in 25 patients requiring third-molar extraction. Uckan and Guler16 achieved adequate anesthesia with DPH in 16 patients requiring extractions. Efficacy of DPH was compared to that of prilocaine in their study. Adequate pulpal anesthesia was achieved with DPH, albeit with a prolonged onset and decreased duration of effect.16 In many studies, however, analgesia was based on the subjective report of the patient or operating dentist.

Figure 1.

Structures of lidocaine and diphenhydramine.

Malamed17 reported use of DPH as a local anesthetic on 25 occasions on patients reporting an allergy to procaine (Novocain) or other local anesthetics. Patients were administered no more than 50 mg of DPH at 1 sitting. The most common adverse event reported by Malamed was a burning sensation during inferior alveolar blocks. In some cases, postoperative edema and erythema were seen. These adverse reactions were more common in the mandible than the maxilla, likely because of the increased volume of DPH used. Swelling subsided spontaneously in 2–3 days in most cases. This case report demonstrates the use of DPH as a local anesthetic to complete multiple dental treatments on a 43-year-old patient with a documented lidocaine allergy.

CASE REPORT

Patient Background

A 43-year-old female patient presented to our dental clinic for comprehensive dental treatment. The patient brought a report from her allergist, who had diagnosed anaphylactic reaction to lidocaine over 5 years earlier. A new consult was sent to test the patient for ester-type local anesthetics, but because of previous anaphylactic reaction to amide-type anesthetic during allergy testing, the patient's allergist declined to test for ester-type local anesthetics. Therefore, treatment with ester local anesthetics, such as chloroprocaine or tetracaine, was not considered. The patient had received dental treatment in the past at another hospital under general anesthesia. The patient was hoping to avoid general anesthesia if possible.

Preparation of DPH Local Anesthetic

DPH local anesthetic was administered as 1% DPH with 1:100,000 epinephrine, based on the Malamed17 protocol. DPH is supplied as 50 mg/mL in 1-mL vials/ampules. Epinephrine hydrochloride is supplied as 1:1000 concentration in 1-mL ampules. To prepare the DPH anesthetic solution, 2 mL of DPH 50 mg/mL was loaded into a 10-mL BD syringe to which 7.9 mL of normal saline was added. Then, 0.1 mL of epinephrine 1:1000 was added into the syringe. Contents were mixed well. This provided 10 mL of 1% DPH with 1:100,000 epinephrine.

Treatment

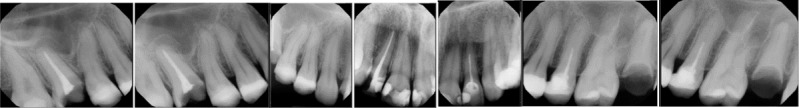

The following treatments were performed based on radiographic (Figure 2) and clinical examination.

Figure 2.

X-rays.

Visit 1: Extraction of tooth 3, tooth 2 occlusal composite, and tooth 6 distolingual composite. The patient was initially sedated with 4 mg of intravenous midazolam. Then, 8 mL of 1% DPH with epinephrine local anesthetic was infiltrated using a tuberculin syringe and 25-gauge needle into the buccal vestibule at sites 2, 3, and 6, with palatal infiltration at site 3. Adequate anesthesia was achieved. On this visit and all subsequent visits, anesthetic effect was based on patient report of no to minimal discomfort.

Visit 2: Extraction of tooth 15 because of gross decay. Five milliliters of 1% DPH with epinephrine local anesthetic was infiltrated into the upper left buccal vestibule and palate adjacent to teeth 14 and 15. Anesthesia was achieved. No intravenous sedation was used during this or subsequent visits.

Visit 3: Restoration on tooth 14 occlusal composite. Four milliliters of 1% DPH with epinephrine local anesthetic was infiltrated into the buccal vestibule with adequate pulpal anesthesia.

Visit 4: Root canal retreatment of tooth 13. At this visit, 2.5 mL of 1% DPH with epinephrine local anesthetic was infiltrated into the buccal vestibule with adequate pulpal anesthesia.

Visit 5: Root canal retreatment of tooth 10. At this visit, 2.5 mL of 1% DPH with epinephrine local anesthetic was infiltrated into the buccal vestibule with adequate pulpal anesthesia.

Visit 6: Prefabricated post and cores were placed in teeth 7 and 10. No local anesthetic was used.

Visit 7: Teeth 7, 8, 9, and 10 were prepared for temporary crowns. Five milliliters of 1% DPH with epinephrine local anesthetic was infiltrated into the buccal vestibule of teeth 8 and 9 with adequate pulpal anesthesia.

Visit 8: Root canal treatment of tooth 12 was completed. Five milliliters of 1% DPH with epinephrine local anesthetic was infiltrated into the buccal vestibule of tooth 12. When files were placed in canals, the patient reported some discomfort. Therefore, intrapulpal injection of 0.5 mL of 1% DPH with epinephrine was given and the patient reported no more pain through the remainder of the procedure.

Visit 9: Prefabricated post and cores were placed in teeth 12 and 13. No local anesthetic was used.

Visit 10: Because of severe sensitivity of teeth 8 and 9 after initial crown preparations, root canal therapy on teeth 8 and 9 was completed. Five milliliters of 1% DPH with epinephrine local anesthetic was infiltrated into the buccal vestibule to achieve pulpal anesthesia. When files were placed in canals, the patient reported discomfort. Therefore, intrapulpal injection of 1.0 mL of 1% DPH with epinephrine was given in total for both teeth. Although the patient still reported some discomfort, she was able to tolerate the procedure.

Visit 11: Prefabricated post and cores were placed in teeth 8 and 9. No local anesthetic was used.

Visit 12: Teeth 12 and 13 were prepared for crowns. Size 1 gingival retraction cord was packed and an impression of teeth 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, and 13 was taken for crowns. Five milliliters of 1% DPH with epinephrine local anesthetic was infiltrated into the buccal vestibule to achieve soft tissue anesthesia.

Visit 13: Crowns 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, and 13 were cemented with glass ionomer cement. No local anesthetic used.

Postoperative Complications

Twenty-four hours after the first treatment session of the upper right quadrant, the patient presented to the clinic with diffuse right swelling (Figure 3). The patient reported no difficulty breathing or swallowing and no trismus. No treatment was rendered and patient was asked to present to the dental clinic for follow-up the next day. Forty-eight hours after treatment, the patient presented to the emergency room at NYU Lutheran Medical Center. Complete blood panel and computed tomography scan were performed. Tests revealed white blood cell count within normal limits, unremarkable computed tomography scan, and normal body temperature. No infection was suspected. Swelling decreased within the next 24 hours.

Figure 3.

Photograph of patient who received 8 mL of 1% diphenhydramine plus 1:100,000 epinephrine. Note the swelling on her right cheek.

A total of 8 mL of anesthetic was administered for the first treatment. Previous cases have shown edema and swelling to be a common side effect associated with the administration of 1% DPH,17 and after the first visit we limited the maximum amount of DPH solution used via infiltration to 5 mL. The patient did experience mild swelling at the injection sites without noticeable facial swelling at subsequent visits. The patient also exhibited remarkable drowsiness at visit 1 approximately 15 minutes after DPH administration. By the end of the procedure, however, the patient reported that the drowsiness had resolved, and she was discharged without incident.

DISCUSSION

Although most case reports involving DPH efficacy are over 20 years old, DPH may still serve as a viable alternative for patients with a true amide local anesthetic allergy. The duration of DPH anesthesia is between 15 and 75 minutes.17,18 It has no cross-reactivity with other local anesthetics and is inexpensive. It has been reported in an older study that DPH provides adequate anesthesia for erupted or minimally impacted third molars 80% of the time.18 Importantly, complete or adequate pain control was in the opinion of the operating dentist. In our case report, although the patient reported no surgical pain during dental extraction and restorative treatment, we did not test pulpal response with an electric pulp tester as a more quantitative measure of local anesthesia. Additionally, some procedures, such as endodontic treatment on nonvital teeth or previously endodontically treated teeth, may not have required effective local anesthesia. Our patient did need additional intrapulpal injection during root canal therapy. In some teeth, local anesthesia was not complete even with intrapulpal anesthesia with DPH during root canal treatment. Other studies have shown that DPH is not as effective as lidocaine to achieve adequate pulpal anesthesia.19 During each visit, our patient reported experiencing a slight burning sensation during administration of DPH at the site of injection, which has also been reported in previous studies.17,20 However, the patient reported no additional pain after the initial injection.

One limitation of DPH local anesthetic is its duration of action, as it may be too short for longer procedures. Although the effectiveness of DPH for mandibular blocks was not evaluated on this patient, previous studies have shown efficacy in providing inferior alveolar nerve anesthesia15,17,20 However, the volume of DPH must be limited per visit to reduce postoperative swelling and drowsiness. The administration technique with the 10-mL Becton Dickinson syringe that we used on this patient does not allow for ideal aspiration techniques, as provided by a typical dental syringe/cartridge apparatus. An aspirating Becton Dickinson syringe is available for use, if desired (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Aspirating Becton Dickinson syringes.

Future use of DPH as a local anesthetic should confirm adequate local anesthesia with pre– and post–local anesthetic electric pulp testing to help verify the efficacy of true pulpal anesthesia.

CONCLUSION

For patients with a documented amide local anesthesia allergy in whom ester local anesthesia is also contraindicated, DPH with epinephrine may be a safe and somewhat effective alternative for maxillary infiltration. Limiting injection volumes to less than 5 mL of 1% DPH with 1:100,000 epinephrine may limit facial swelling and drowsiness. We report a case of a 43-year-old female who had dental treatment completed with minimal intraoperative dental surgical pain following the use of 1% DPH with 1:100,000 epinephrine for maxillary infiltration. Because of the short duration of action of DPH with 1:100,000 epinephrine and risk of postoperative edema, it may be prudent for dentists to limit treatment to 1 tooth at each treatment session. For extensive and longer procedures, treatment may be more suitable under intravenous sedation or general anesthesia.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rood JP, . Adverse reaction to dental local anaesthetic injection—“allergy” is not the cause. Br Dent J. 2000; 189.7: 380– 384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hersh EV, Condouris GA, . Local anesthetics: a review of their pharmacology and clinical use. Compendium. 1987; 8: 374, 376, 378– 381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hersh EV, Saraghi M, Moore PA, . Intranasal tetracaine and oxymetazoline: a newly approved drug formulation that provides maxillary dental anesthesia without needles. Curr Med Res Opin, 2016; 32: 1919– 1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Giannakopoulos H, Levin LM, Chou JC,et al. The cardiovascular effects and pharmacokinetics of intranasal tetracaine plus oxymetazoline: preliminary findings. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012; 143: 872– 880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hersh EV, Ciancio SG, Kuperstein AS,et al. An evaluation of 10 percent and 20 percent benzocaine gels in patients with acute toothaches: efficacy, tolerability and compliance with label dose administration directions. J Am Dent Assoc. 144: 517– 526, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hersh EV, Pinto A, Saraghi M,et al. Double-masked, randomized, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of intranasal K305 (3% tetracaine plus 0.05% oxymetazoline) in anesthetizing maxillary teeth. J Am Dent Assoc. : 278– 287, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen AH, . Toxicity and allergy to local anesthesia. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1998; 26: 683– 692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pallasch TJ, . Vasoconstrictors and the heart. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1998; 26: 668– 673, 676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Seng GF, Gay BJ, . Dangers of sulfites in dental local anesthetic solutions: warning and recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc. 1986; 113: 769– 770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosenthal SR, Minard D, . Experiments on histamine as the chemical mediator for cutaneous pain. J Exp Med. 1939; 70: 415– 425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haranath PSRK, . A comparative study of the local and spinal anesthetic actions of some antihistamines, mepyramine, and phenegran with procaine. Indian J Med Sci. 1954; 8: 547– 554. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pollack CV, Swindle GM, . Use of diphenhydramine for local anesthesia in “caine”-sensitive patients. J Emerg Med. 1989; 7: 611– 614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Green SM, Rothrock SG, Gorchynski J, . Validation of diphenhydramine as a local anesthetic. Ann Emerg Med. 1994; 23: 1284– 1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ernst AA, Anand P, Nick T, Wassmuth S, . Lidocaine versus diphenhydramine for anesthesia in the repair of minor lacerations. J Trauma. 1993; 34: 354– 357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Welborn JF, Kane JP, . Conduction anesthesia using diphenhydramine hydrochloride. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964; 69: 706– 709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Uckan S, Guler N, Sumer M, Ungor M, . Local anesthetic efficacy for oral surgery: comparison of diphenhydramine and prilocaine. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998; 86: 26– 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Malamed SF, . Diphenhydramine hydrochloride: its use as a local anesthetic in dentistry. Anesth Prog. 1973; 20: 76– 82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gallo WJ, Ellis E III., . Efficacy of diphenhydramine hydrochloride for local anesthesia before oral surgery. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987; 115: 263– 266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Willet J, Reader A, Drum M, Nusstein J, Beck M, . The anesthetic efficacy of diphenhydramine and the combination diphenhydramine/lidocaine for the inferior alveolar nerve block. J Endod. 2008; 34: 1446– 1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bass KD, . Tissue response to diphenhydramine hydrochloride. J Oral Surg. 1970; 28: 335– 345 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]