Abstract

Purpose

Skeletal muscle wasting is an independent predictor of health-related quality of life and survival in patients with COPD, but the complexity of molecular mechanisms associated with this process has not been fully elucidated. We aimed to determine whether an impaired ability to repair DNA damage contributes to muscle wasting and the accelerated aging phenotype in patients with COPD.

Patients and methods

The levels of phosphorylated H2AX (γH2AX), a molecule that promotes DNA repair, were assessed in vastus lateralis biopsies from 10 COPD patients with low fat-free mass index (FFMI; COPDL), 10 with preserved FFMI and 10 age- and gender-matched healthy controls. A panel of selected markers for cellular aging processes (CDKN2A/p16ink4a, SIRT1, SIRT6, and telomere length) were also assessed. Markers of oxidative stress and cell damage and a panel of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines were evaluated. Markers of muscle regeneration and apoptosis were also measured.

Results

We observed a decrease in γH2AX expression in COPDL, which occurred in association with a tendency to increase in CDKN2A/p16ink4a, and a significant decrease in SIRT1 and SIRT6 protein levels. Cellular damage and muscle inflammatory markers were also increased in COPDL.

Conclusion

These data are in keeping with an accelerated aging phenotype as a result of impaired DNA repair and dysregulation of cellular homeostasis in the muscle of COPDL. These data indicate cellular degeneration via stress-induced premature senescence and associated inflammatory responses abetted by the senescence-associated secretory phenotype and reflect an increased expression of markers of oxidative stress and inflammation.

Keywords: COPD, skeletal muscle wasting, aging, inflammation, apoptosis

Introduction

COPD is associated with several extra-pulmonary effects. Among these, peripheral skeletal muscle wasting1 is common and can be present even in those patients with normal body weight.2 This has a significant impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL),3 health care utilization,4 morbidity and mortality.5 The molecular mechanisms underlying skeletal muscle wasting are not fully understood and are likely to be multifactorial. Several mechanisms have been shown to be linked to muscle wasting in COPD, including systemic inflammation,6 oxidative stress,7 cell hypoxia,8 physical inactivity9 and nutritional depletion.10

It has recently been reported that the maintenance of peripheral muscle mass in COPD may be compromised due to accelerated aging11 and exhaustion of the regenerative potential of the muscles.12 In addition, upregulation of genes involved in the inhibition of cell growth and cell cycle arrest in COPD patients with muscle wasting,13 particularly the expression of CDKN1A/p21WAF1/Cip1 at both the transcript and protein level, has been related to downregulation of histone methyltransferase DOT1L.13,14 Activation of CDKN1A/p21WAF1/Cip1 (signaled by the downregulation of DOTL1) and the concomitant DNA damage response (DDR)15 leads to cell cycle arrest, potentially providing time to repair cellular damage through engagement of compensatory or repair mechanisms,16 such as DNA repair mediated by H2AX.15 It has been shown that CDKN1A/p21WAF1/Cip1 inactivates H2AX phosphorylation and promotes DNA instability.17 Phosphorylated H2AX (γH2AX) promotes assembly of DNA repair complexes at damaged sites on chromosomes. In turn, decreased phosphorylation of H2AX contributes to the impairment of DNA repair and has been linked to cellular senescence and accumulation of DNA damage.15

In situations of irreparable damage, CDKN1A/p21WAF1/Cip1 promotes cellular degeneration by initiating stress-induced premature senescence triggered by oxidative stress,8,18 which is a feature of skeletal muscle in COPD. In turn, senescent cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines as part of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).19 These alter the tissue microenvironment, attract immune cells and induce, via paracrine mediated changes in nearby cells, a decrease in the replacement of damaged cells, as has been reported in aging skeletal muscle.20

We hypothesized that cell cycle arrest mediated by CDKN1A/p21WAF1/Cip1,13,14 in combination with the downregulation of H2AX, contributes to the impairment of DNA repair, promoting cellular degeneration by initiating stress-induced premature senescence. This facilitates a SASP that further interferes with the replacement of damaged cells in patients with COPD and muscle wasting. To test this hypothesis, we assessed γH2AX protein levels in the vastus lateralis muscle of patients with COPD with and without low fat-free mass index (FFMI), as a surrogate of muscle mass wasting, and in a group of age- and gender-matched healthy controls. Several markers of cellular aging and stress (telomere length, CDKN2A/p16ink4a, Sirtuin 1 and Sirtuin 6) were also assessed to confirm any cellular senescence phenotype, while markers of oxidative stress and cytokine expression were assessed to confirm the stress-induced premature senescence and the SASP. We also hypothesized that these chains of events would further interfere with the replacement of damaged cells, potentially leading to programmed cell death in the muscle of COPD patients with low FFMI (COPDL). Correspondingly, we also assessed the expression of MyoD and markers of apoptosis.

Patients and methods

Study group and patient’s characteristics

A total of 20 stable patients with COPD, 10 with low FFMI and 10 with normal FFMI, and 10 age-, gender- and smoking status-matched healthy subjects with normal FFMI were included in the study (Table 1). All patients had been diagnosed with COPD according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.21 Patients were clinically stable and free of exacerbations for 4 weeks before inclusion in the study. All participants were informed of any risks and discomfort associated with the study, and written informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the Lothian Regional Ethics Committee. The following baseline assessments were performed for each study participant: anthropometric measurements, body composition measured by bioimpedance (TBF-300M; Tanita Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), spirometry (Alpha Spirometer; Vitalograph, Buckingham, UK), blood gases (Ciba Corning 800; Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA), 6-minute walking distance, quadriceps maximal voluntary contraction (QMVC; Chatillon® K-MSC 500; Ametek, Doral, FL, USA), HRQoL questionnaires (St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, SGRQ), modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale and physical activity levels using the Voorrips physical activity questionnaire and the London Chest Activity of Daily Living Scale for patients with COPD. The number of exacerbations in the previous year was recorded. Low FFMI was defined as <16 kg·m−2 for male COPD patients and <15 kg·m−2 for female COPD patients.22

Table 1.

Clinical and experimental cohort characteristics

| Characteristics | Controls | Diff | COPDN | Diff | COPDL | Diff | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male/female | 8/2 | A | 8/2 | A | 8/2 | A | ns |

| Age (years) | 68.3±4.4 | 68.9±4.6 | 66.7±5.9 | ns | |||

| Height (m) | 1.74±0.08 | A | 1.70±0.09 | A | 1.67±0.08 | A | ns |

| Weight (kg) | 89.93±15.63 | A | 76.1±12.65 | A | 51.71±5.71 | B | 0.0001 |

| BMI (kg·m−2) | 30.6±6.9 | A | 26.0±2.2 | A | 18.9±1.9 | B | <0.0001 |

| FFM (kg) | 62.55±11.35 | A | 54.13±10.13 | A | 43±5.69 | B | <0.005 |

| FFMI (kg·m−2) | 20.4±2.7 | A | 18.6±1.4 | A | 15.3±0.7 | B | <0.0001 |

| Active/ex-smokers | 2/8 | A | 2/8 | A | 2/8 | A | ns |

| Number of cigarettes (pack-years) | 31.9±15.8 | A | 48.7±21 | A | 64.3±39.8 | A | ns |

| Average smoking cessation (years) | 23.2±17.3 | A | 8.4±7 | B | 5.4±7.4 | B | <0.01 |

| Age at smoking cessation (years) | 45.1±15.5 | A | 60.5±7.6 | B | 61.3±7.8 | B | <0.01 |

| mMRC | 2.9±1.3 | 4.1±1.1 | ns | ||||

| FEV1 (L) | 2.8±0.6 | A | 1.2±0.5 | B | 0.9±0.4 | B | <0.0001 |

| FEV1 (% predicted) | 94.4±12.6 | A | 44.1±18.3 | B | 33.2±13.7 | B | <0.0001 |

| FVC (L) | 3.9±0.7 | A | 2.7±1.1 | B | 2.6±1 | B | <0.01 |

| FVC (% predicted) | 103.7±10.1 | A | 87.8±28.5 | AB | 76.5±18.2 | B | <0.05 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.7±0 | A | 0.4±0.1 | B | 0.3±0.1 | B | <0.0001 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 73.1±5.4 | A | 70.2±9.8 | 75.2±13.1 | ns | ||

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 41.8±1.7 | A | 41±3.4 | 43.1±5.2 | ns | ||

| Physical activity (V) | 11.0±4.6 | A | 7.2±6 | B | 1.1±1 | C | <0.0001 |

| Physical activity (L) | 30±15.8 | 43.5±10.4 | ns | ||||

| QMVC (N) | 366.6±84.8 | A | 323.3±81 | A | 202.2±51.8 | B | <0.005 |

| 6MWD (m) | 523.8±120.1 | A | 411±158.4 | B | 327±134.1 | B | <0.01 |

| Exacerbation | 1.8±1.5 | A | 4±2.2 | B | <0.05 | ||

| BODE index | 4±2.7 | A | 6.2±2.3 | A | ns | ||

| SGRQ symptoms | 60.1±13.4 | A | 78.3±15.2 | B | <0.05 | ||

| SGRQ activity | 52.1±29.2 | A | 86.2±13.4 | B | <0.005 | ||

| SGRQ impact | 33±24.4 | A | 59.5±20.8 | B | <0.05 | ||

| SGRQ total | 43.5±21.7 | A | 70.7±16.4 | B | <0.01 | ||

| Type I fiber (%) | 38.5±11 | A | 23.9±9.3 | B | 24.7±13.5 | B | <0.05 |

| Type II area (μ2) | 2,564±783.8 | AB | 2,978±785.9 | A | 2,034±498.8 | B | <0.05 |

Notes: Physical activity (V): Voorrips questionnaire; physical activity (L): London Chest Activity of Daily Living Scale. Comparisons among groups were performed using ANOVA and Student–Newman–Keuls as a post hoc test. Diff among the three different groups are stated using letters A, B and C, where sharing a letter implies no differences between these groups and having a different letter implies a statistical difference in the post hoc test.

Abbreviations: 6MWD, 6-minute walking distance; ANOVA, analysis of variance; BMI, body mass index; BODE index, Body-mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea, and Exercise; COPDL, COPD patients with low FFMI; COPDN, COPD patients with normal FFMI; Diff, differences; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FFM, fat-free mass; FFMI, fat-free mass index; FVC, forced vital capacity; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; ns, not significant; PaCO2, arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure; PaO2, arterial oxygen partial pressure; QMVC, quadriceps maximal voluntary contraction; SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

Muscle biopsy

An open muscle biopsy of the vastus lateralis was collected in the Clinical Research Facility using a standard surgical technique. Immediately after collection, samples were divided into three groups: 1) fixed in formaldehyde and paraffin embedded, 2) perfused with RNA stabilization reagent (RNAlater®; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and stored at −20°C and 3) immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for further analyses.

Vastus lateralis muscle protein extraction

Total protein was extracted and purified from ~0.1 g vastus lateralis muscle by homogenization of tissue in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer using standard procedures. Total protein was measured by the bicinchoninic acid method.

Skeletal muscle fiber composition

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections (5 μm) were de-waxed and rehydrated through graded ethanol using standard procedures. Five images per patient were included in the analysis. A total of 959.6±146.4, 715.0±89.2 and 918.6±95.2 fibers in control subjects, COPD patients with normal FFMI (COPDN) and COPDL, respectively, were assessed. Type I, type II and hybrid fibers were counted using a manual tag protocol using Image-Pro® Plus (Media Cybernetics, Inc., Bethesda, MD, USA) and expressed as a proportion of total fibers assessed.

Immunoblotting

Twenty micrograms of total protein was used per sample. The following primary antibodies were used: γH2AX (1:1,000, 2577S; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA); CDKN2A/p16ink4a (1:1,000, ab 81278; Abcam, Cambridge, UK); SIRT1 (1:1,000, ab 32441; Abcam); SIRT6 (1:1,000, ABE102; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA); anti-perilipin A (1:1,000, P1998-200UL; Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA); anti-MyoD1 (1:1,000; Abcam); cleaved caspase-3 (Asp175; 1:1,000, 9661S; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). GAPDH was used as a load control (1:5,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Dallas, TX, USA). The optical densities were quantified using a densitometer and Image-Pro Plus.

Relative telomere length measurement

DNA was isolated from vastus lateralis biopsies using Maxwell®16 machine (Promega Corporation, Fitchburg, WI, USA) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. DNA concentration and integrity were assessed by NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop® ND-1000; NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE, USA). Relative telomere length was measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) following the method described by Cawthon et al.23

Muscle oxidative stress markers

4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) levels were assessed by incubating the membrane with polyclonal anti-HNE antibody (1/3,000, AB5605; EMD Millipore). Specific proteins were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and a chemiluminescence kit.

Measurement of muscle inflammatory markers

Muscle cytokine levels were measured using Cytometric Bead Array (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) for simultaneous detection of 10 cytokines (TNFα, soluble receptor TNFRI, soluble receptor TNFRII, IFNγ, IL1β, IL5, IL6, IL8, IL10 and IL12p70) in tissue homogenate.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay

TUNEL assay was used to evaluate cell apoptosis in paraffin-embedded sections of vastus lateralis following the manufacturer’s instructions. Apoptotic nuclei were expressed as the percentage of the TUNEL-positive nuclei (red stain) from the total number of counted nuclei (blue). A total of 200 nuclei were the minimum amount counted in each paraffin-embedded section. Positive and negative controls were included for each section.

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Each variable was tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and statistical test selected accordingly. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Student–Newman–Keuls as a post hoc test was used for normally distributed variables, while a Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc test was applied to non-normally distributed variables. Correlation analysis was performed using Pearson or Spearman tests for normally and non-normally distributed variables, respectively. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data were analyzed using the statistical package program SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient’s characteristics

Anthropometric characteristics and pulmonary function data for the study subjects are summarized in Table 1. Both groups of COPD patients had airflow limitation compared to healthy controls, which had normal spirometry. There were no significant differences in spirometry between COPDN and COPDL. Detailed description of the study subjects with clinical and experimental parameters, methods and results is given in Supplementary materials.

The subjects with COPDL had lower body mass index (BMI), fat-free mass (FFM), FFMI (as expected by the study design), poorer HRQoL with higher values in all the domains of the SGRQ and worse muscle function as assessed by QMVC as compared to COPDN. No statistical differences in physical activity measured by the Voorrips questionnaire or activities of daily living (ADLs) assessed with the London Chest Activity of Daily Living were seen between the two groups of COPD patients, although there was a trend toward lower physical activity measured by London Chest Activity of Daily Living in COPDL.

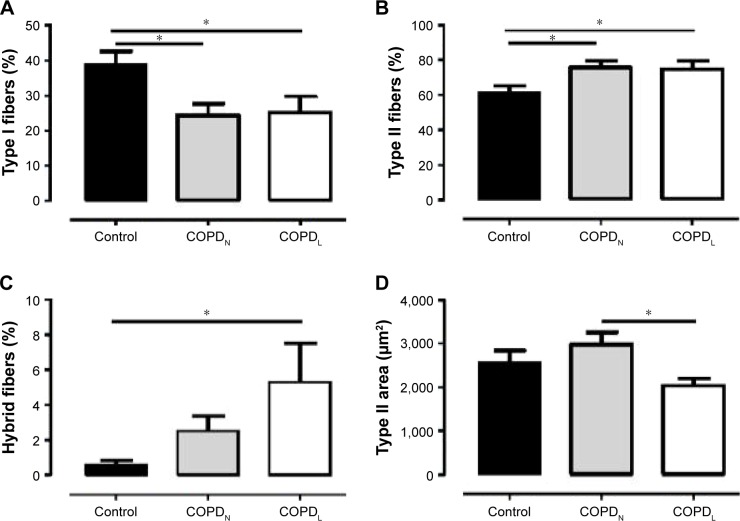

Both COPD groups showed a redistribution of muscle fiber type with a higher proportion of type II fibers and a lower proportion of type I in comparison to healthy controls. Type II fiber area was reduced in COPDL in comparison to COPDN and controls but only reached statistical significance difference with COPDN (Table 1; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Vastus lateralis fiber characteristics.

Notes: Mean (SEM) values for the percentage of type I fibers (A), the percentage of type II fibers (B), the percentage of hybrid fibers (C) and type II fiber size (area) (D) in healthy controls (■), COPDN [img] and COPDL (□). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05.

Abbreviations: COPDL, COPD patients with low FFMI; COPDN, COPD patients with normal FFMI; FFMI, fat-free mass index; SEM, standard error of the mean.

High percentage of hybrid fiber type was found in COPDL in comparison to COPDN and controls (statistically difference only vs controls), which suggests that the transformation from one fiber type to another could constitute a mechanism leading to the redistribution and atrophy of fibers seen in COPD.1 Vastus lateralis of patients with COPD and muscle wasting exhibit higher levels of lipid infiltration as shown by higher levels of perilipin A in comparison to both COPDN and healthy controls (Figure S1).

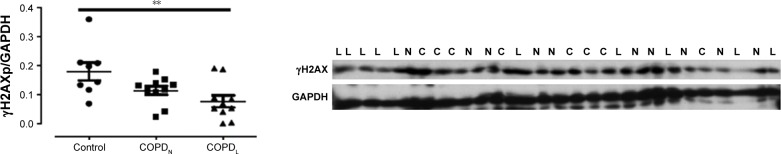

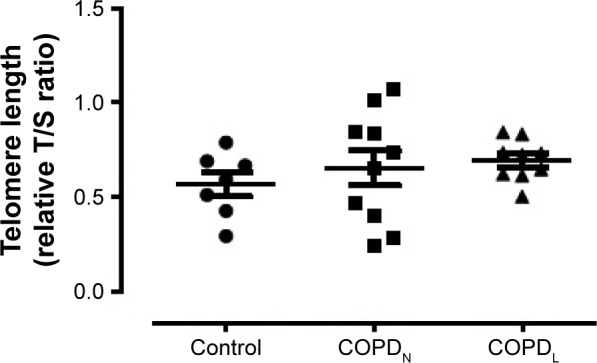

DNA repair and biomarkers of aging

γH2AX levels were reduced in COPDN in comparison to controls and further reduced in COPDL patients, but only the latter reached statistical significance (Figure 2). Both COPD groups displayed an increase in CDKN2A/p16ink4a levels, although statistical significance was not reached when compared to controls (Figure 3A). Furthermore, SIRT1 levels were decreased in COPDL in comparison to COPDN and controls (Figure 3B) but only reached statistical significance against controls. In turn, reduced levels of SIRT6 were seen in COPDL in comparison to both COPDN and controls (p<0.05) (Figure 3C). No significant differences in the relative telomere length between analyzed groups were noted (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Protein levels of γH2AX in vastus lateralis muscle of COPDL, COPDN, and healthy controls.

Notes: Data are presented as mean ± SEM; ANOVA **p<0.01, post hoc test showed statistical differences between COPDL and healthy controls. L represents COPDL; N represents COPDN; and C represents healthy controls.

Abbreviations: γH2AX, phosphorylated H2AX; ANOVA, analysis of variance; COPDL, COPD patients with low FFMI; COPDN, COPD patients with normal FFMI; FFMI, fat-free mass index; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Figure 3.

Protein levels of CDKN2A/p16ink4a (A) (p=0.27), SIRT1 (B) and SIRT6 (C) in vastus lateralis of COPDL (□), COPDN [img] and healthy controls (■).

Notes: Data are presented as mean ± SEM, *p<0.05; **p<0.01. L represents COPDL; N represents COPDN; and C represents healthy controls.

Abbreviations: COPDL, COPD patients with low FFMI; COPDN, COPD patients with normal FFMI; FFMI, fat-free mass index; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Figure 4.

Relative telomere length in vastus lateralis muscle of COPDL, COPDN, and healthy controls.

Notes: Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Relative T/S ratio: repeat copy number to single copy gene number.

Abbreviations: COPDL, COPD patients with low FFMI; COPDN, COPD patients with normal FFMI; FFMI, fat-free mass index; SEM, standard error of the mean.

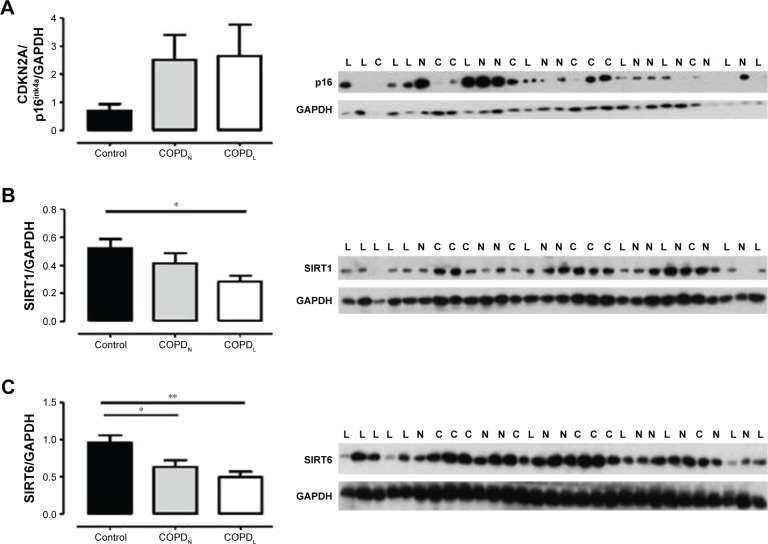

Oxidative stress in COPD

The anti-HNE antibody detected five positive protein bands with apparent mass ranging from 30 to 150 kDa. The intensities of all the HNE-positive bands and total HNE optical densities were greater in muscles of COPDL compared to COPDN and control subjects. However, only one band (band 3) reached statistical significance against COPDN (p<0.05; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Assessment of lipid peroxidation; protein levels of HNE (bands 1–5, molecular weight ranging from 30 to 150 kDa) in vastus lateralis muscle of COPDL, COPDN, and healthy controls.

Note: Data are presented as mean ± SEM, *p<0.05.

Abbreviations: COPDL, COPD patients with low FFMI; COPDN, COPD patients with normal FFMI; FFMI, fat-free mass index; HNE, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal; SEM, standard error of the mean.

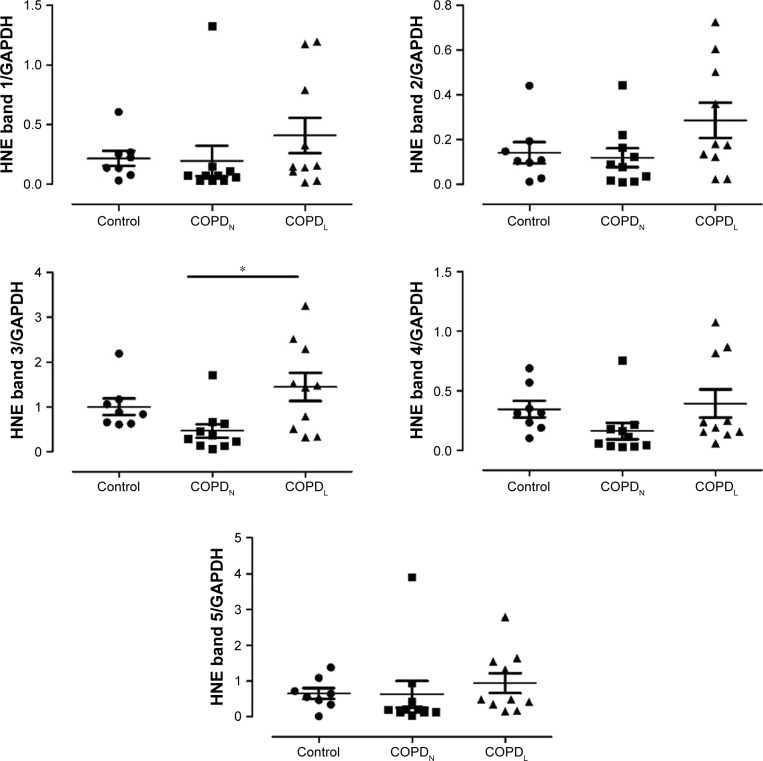

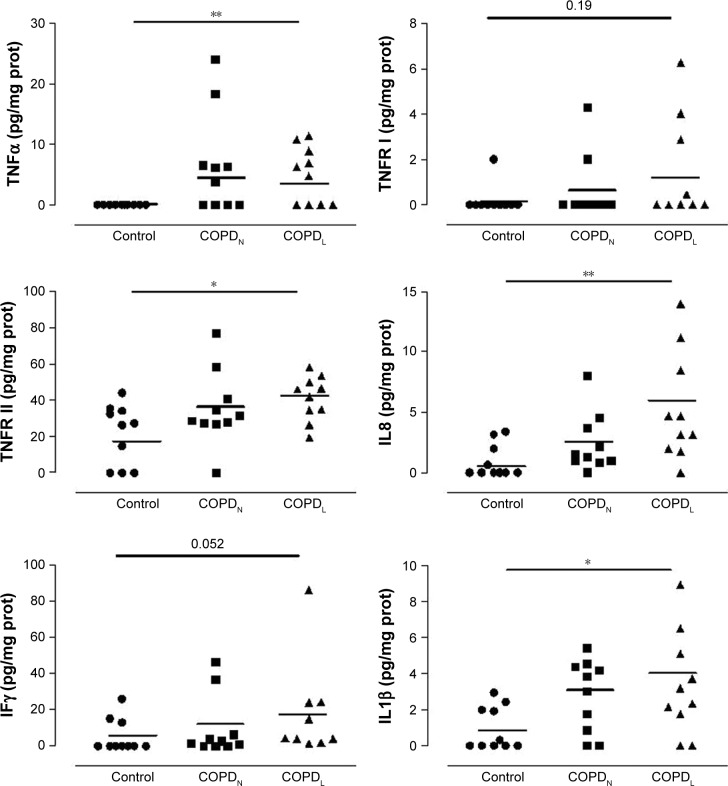

Markers of inflammation in vastus lateralis

Figure 6 shows cytokine expressions in all three groups. COPDL patients showed higher levels of TNFRII, IL8, IL1β and IL10 in comparison to COPDN and controls but reached statistical significance only against controls.

Figure 6.

Vastus lateralis cytokine profiling in COPDL, COPDN and healthy controls.

Notes: Data are presented as mean ± SEM; *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Abbreviations: COPDL, COPD patients with low FFMI; COPDN, COPD patients with normal FFMI; FFMI, fat-free mass index; prot, protein; SEM, standard error of the mean.

TNFα was increased in both COPD groups in comparison to controls but only COPDL reached statistical significance.

A strong tendency toward increased levels of TNFRI (p=0.1), IFNγ (p=0.052) and IL12p70 (p=0.09) was noted in COPD patients compared to healthy controls, most notably in the COPDL group. IL12p70 was also increased in both COPD groups in comparison to controls but this did not reach statistical significance. IL5 was statistically significantly increased in both COPD groups in comparison to healthy controls.

Several cytokines were correlated with lung function parameters, exercise tolerance and muscle function and structure (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlations between muscle cytokine levels and clinical parameters

| IL5 | IL8 | IL1β | IL10 | TNFα | TNFRI | TNFRII | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1 | |||||||

| r | −0.49 | −0.52 | −0.50 | −0.40 | −0.51 | −0.57 | |

| p-value | <0.01 | <0.005 | <0.005 | <0.05 | <0.005 | <0.001 | |

| QMVC | |||||||

| r | −0.41 | −0.48 | −0.46 | −0.39 | −0.55 | −0.41 | −0.54 |

| p-value | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.01 | <0.05 | <0.005 | <0.05 | <0.005 |

| 6MWD | |||||||

| r | −0.46 | −0.59 | −0.40 | −0.58 | −0.42 | −0.53 | |

| p-value | <0.05 | <0.005 | <0.05 | <0.005 | <0.05 | <0.005 |

Note: Correlations (r- and p-values) between vastus lateralis cytokines and parameters of lung function, exercise tolerance and muscle function.

Abbreviations: 6MWD, 6-minute walking distance; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; QMVC, quadriceps maximal voluntary contraction.

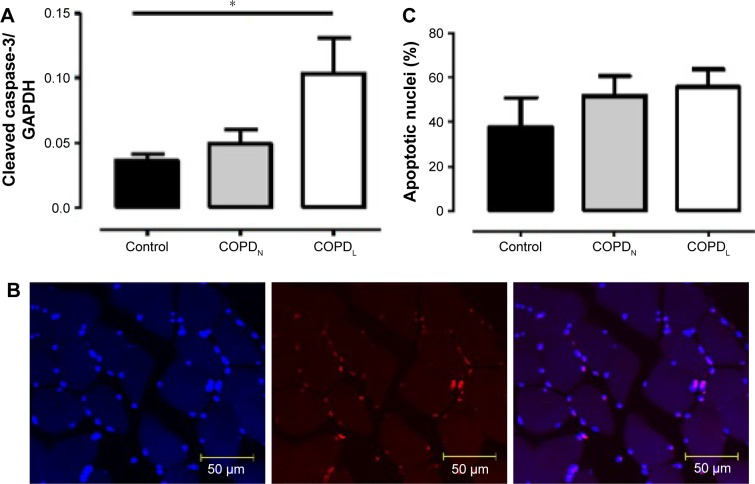

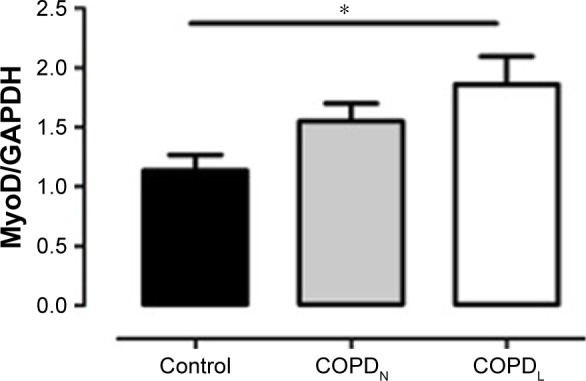

Muscle regeneration and apoptosis

An increase in MyoD protein content was observed in patients with COPDL in comparison to COPDN and healthy controls and only reached statistical significance against controls (p<0.05; Figure 7). Equally, COPDL showed significantly higher levels of the cleaved caspase-3 in comparison to healthy controls (p<0.05; Figure 8A). TUNEL assays showed that the percentage of apoptotic nuclei was higher in COPDL (55.7±25.48) in comparison to COPDN (51.6±25.49) and healthy controls (37.5±37.51) but this difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.42; Figure 8B and C).

Figure 7.

MyoD protein levels in vastus lateralis muscle of COPDL (□), COPDN [img] and healthy controls (■).

Notes: Data are presented as mean ± SEM; *p<0.05.

Abbreviations: COPDL, COPD patients with low FFMI; COPDN, COPD patients with normal FFMI; FFMI, fat-free mass index; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Figure 8.

(A) Protein levels of cleaved caspase-3 in vastus lateralis muscle of COPDL (□), COPDN [img] and healthy controls (■). (B) Confocal microscope images of TUNEL assay in paraffin-embedded sections of vastus lateralis muscle, blue stain (DAPI) normal nuclei; red stain (TUNEL stain); double stain (red + blue) apoptotic nuclei. (C) TUNEL assay. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; *p<0.05 COPDL patients compared to healthy controls.

Abbreviations: COPDL, COPD patients with low FFMI; COPDN, COPD patients with normal FFMI; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; FFMI, fat-free mass index; SEM, standard error of the mean; TUNEL, transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling.

Discussion

Our data are consistent with a decreased ability to repair DNA in the vastus lateralis of patients with COPD and muscle wasting. Increased markers of oxidative stress reflected a stress-induced premature senescence in keeping with our previous findings of increased CDKN1A/p21WAF1/Cip113 mediated by downregulation of DOT1L.14 Furthermore, reduced levels of Sirtuin 1 and Sirtuin 6, are consistent with this hypothesis. This leads to a SASP reflected by the increased levels of vastus lateralis cytokine expression. In turn, COPDL muscle showed evidence of structural and functional impairment, such as type II fiber atrophy, increased proportion of type II fibers, lipid infiltration (perilipin A) and reduced QMVC.

DNA damage triggers a response that aims to restore DNA integrity through repair. This DDR is initiated via the recognition of the damage by a number of protein kinases, where phosphorylation of H2AX promotes assembly of DNA repair complexes at damaged sites of chromosomes and phosphorylation of Chk1 and Chk2 kinases. The latter induces temporal cell cycle arrest via the p53/CDKN1A/p21WAF1/Cip1 and CDC25/cdk1 pathways. An increased activation of p53–CDKN1A/p21WAF1/Cip1 signaling, due to the persistent damage, would lead to an increased number of γH2AX foci and a permanent growth arrest or apoptosis. We have previously shown the upregulation of CDKN1A/p21WAF1/Cip113 concomitant with the downregulation of DOT1L in the same study population. In the current investigation, we have shown significantly lower levels of γH2AX only in COPD patients with muscle wasting in comparison to healthy controls. It is known that the downregulation of H2AX leads to a greater accumulation of CDKN1A/p21WAF1/Cip1, whereas the overexpression of CDKN1A/p21WAF1/Cip1 inactivates H2AX phosphorylation and promotes DNA instability.17 Our findings are consistent with previous studies which demonstrate that decreased levels of γH2AX focus formation were associated with increased DNA damage.17 Age-related deterioration of DDR can explain, at least in part, the inability of senescent cells to phosphorylate H2AX and form foci.17

To further investigate this hypothesis, we have assessed levels of proven markers of cellular stress and senescence, namely SIRT1 and SIRT6.24

Sirtuins are a family of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide+-dependent protein deacetylases involved in stress resistance and metabolic homeostasis.24 SIRT1 possesses multiple metabolic functions including the increase in cellular stress resistance and the suppression of apoptosis, which might indicate a beneficial role in longevity.25 SIRT6 is reported to influence genomic instability playing a role in DNA repair by modulating metabolic processes to minimize reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and DNA damage.25

We found a decrease in SIRT1 and SIRT6 protein levels in the COPDL group.

Decrease in SIRT1 and SIRT6 expression together with increased CDKN2A/p16ink4a expression (although not statistically significant) suggests the dysregulation of cellular homeostasis, activation of cellular damage responses and accelerated physiological senescence.

SIRT1 is a negative regulator of p53-induced damage responses.26 It has been reported that a lack of SIRT1 associates with a reduced ability to repair DNA damage.27 SIRT1 is markedly reduced in peripheral blood and lung tissue from patients with COPD as a result of excessive oxidative stress.28 SIRT6 is an important modulator of DNA repair26 and is also reduced in COPD lungs.29 Interestingly, SIRT6 action is complex and may reflect changes in metabolic status of cells.25 Low levels of SIRT1 and SIRT6 indicate more evidence of DNA damage confirmed by the downregulation of γH2AX and high levels of CDKN1A/p21WAF1/Cip1.

It is of note that, although COPDL showed the lowest levels of SIRT1 and SIRT6 and this was statistically significant in comparison to the control group, there was no statistically significant difference with COPDN. However, there was also no difference in these markers of aging between COPDN and controls. Despite this lack of statistical difference between COPDL and COPDN, there was a clear difference in FFMI, function (QMVC) and structure (type II atrophy, perilipin A expression) in the COPDL in comparison to COPDN. It can be hypothesized that these markers were not reduced enough below a “threshold” to initiate the aging process in the COPDN population, although this remained to be elucidated. The fact that CDKN1A/p21WAF1/Cip1 was increased only on the COPDL in the same population in our previous publication is in keeping with this. It is also possible that the reduced sample size precludes these differences to reach statistical significance as given in the “Limitations of the study” section.

The relative contribution of the p53/CDKN1A/p21WAF1/Cip1 and CDKN2A/p16ink4a effector pathways to the initial growth arrest can vary depending on the type of the stress.16 DNA damage initially halts cell cycle progression through the induction of CDKN1A/p21WAF1/Cip1, but if lesions persist, this activates CDKN2A/p16ink4a through p38-MAPK-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS production.30 We have previously demonstrated an upregulation of CDKN1A/p21WAF1/Cip1 in the subgroup of patients with muscle wasting.

The absence of changes in telomere length suggests that muscle cells are undergoing a stress-induced premature senescence rather than replicative senescence. It has been reported that stress induced premature senescence is independent of telomere attrition in keeping with the current findings. Moreover, several other stresses have been shown to induce a senescent growth arrest in vitro, including certain DNA lesions and ROS.31 In line with this, our data showed higher levels of oxidative stress markers (HNE). Interestingly, we have previously found the upregulation of heat shock protein beta-1 and alpha-crystallin B chain involved in oxidative stress protection in COPDL.14 Evidence of oxidative stress has previously been shown in peripheral muscle of COPD patients18,32 especially in patients with low BMI33 and hypoxemia.8 This suggests that oxidative stress may play a role as a trigger of stress-induced senescence in COPD patients with muscle wasting who display a reduced ability to protect against oxidative stress.34,35

Irrespective of the senescence-inducing stressor or mechanism,19 senescent cells express a SASP. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines are among the SASP components that are highly conserved across cell types and senescence-inducing stimuli, which suggest that attracting immune cells and inducing local inflammation are common properties of senescent cells. To further investigate the local release of cytokines, a panel of anti- and pro-inflammatory cytokines was assessed in the vastus lateralis of our population. The levels of the inflammatory markers were higher in the vastus lateralis of patients with COPD, particularly in the COPDL group.36 It is difficult to establish the relevance of the changes between the groups. Interestingly, when the relationship between cytokine levels and relevant clinical outcomes was explored (ie, forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1], QMVC, 6-minute walk test [6MWT]), there were significant correlations between these clinical outcomes and levels of cytokines in the muscle (Table 2).

It has been reported that severe stress induces apoptosis, whereas mild damage induces accelerated aging.37 However, increasing evidence has shown that the outcome of cell stress is not entirely dose dependent38 and that the responses of cells seem to be predetermined by their tissue of origin. Previous studies have shown increased markers of apoptosis in skeletal muscle of patients with COPD39 together with an increased mitochondrial cytochrome C release in response to stress.40 Our data showed higher levels of programmed cell death in the muscle of COPD patients. This suggests that cellular senescence and apoptosis are not mutually exclusive and can coexist in the muscle.

Our results are in keeping with previous studies showing that limb muscles of patients with COPD have increased number of senescent satellite cells and an exhausted muscle regenerative capacity, compromising the maintenance of muscle mass in these individuals.11 The higher expression of MyoD, the muscle-specific transcription factor associated with muscle differentiation seen in COPDL, may reflect an unsuccessful attempt to maintain muscle mass, which could be mediated by the downregulation of SIRT1.41

Limitations of the study

In this study, only the γH2AX has been measured. The ratio γH2AX/H2AX has, therefore, not been calculated. Although this would have added information on the relationship between the phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated form, it is the phosphorylation of histone H2AX that is implicated in the maintenance of DNA stability, and its levels strongly increase following DNA damage.17

Moreover, it is expected to find higher levels of γH2AX in cells exposed to genotoxic stresses as occurred in our population of COPD patients with muscle wasting. We believe that limiting our study to the γH2AX would not affect the validity of the findings.

Another limitation of the study is the small sample size. Studies requiring invasive techniques such as a muscle biopsy are difficult to recruit. This may have influenced the lack of statistical difference in some of the assessments (ie, SIRT1 and SIRT6). Although a clear tendency was seen in the levels of these molecules, only statistical differences were reached between COPDL and controls. We believe that this could be due to a type II error. A sample size of 22 patients per group would have been necessary to reach statistical differences with a power of 90% (ie, for SIRT1).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates an impaired capacity for DNA repair and the differential expression of proteins related to cell cycle arrest and accelerated aging showing the evidence of cellular senescence in vastus lateralis of COPD patients with muscle wasting. High levels of oxidative stress suggest that this mechanism may be the trigger for stress-induced premature senescence in the muscle of COPD patients. High levels of inflammatory markers suggest the evidence of an SASP. Premature cellular senescence and subsequent exhaustion of the muscle regenerative potential may thus be related to the muscle abnormalities that are characteristics of these patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Mike Millar for his help on the fiber-type analysis. The authors would also like to thank the Chief Scientist Office (CSO 06/S1103/5), The British Lung Foundation (Trevor Clay, Tc07/09) and the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS 08/0320) for the financial support. Dr Ramzi Lakhdar was supported by a European Respiratory Society long-term research fellowship (LTRF 068-2012).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Rabinovich RA, Vilaro J. Structural and functional changes of peripheral muscles in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010;16(2):123–133. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328336438d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eid AA, Ionescu AA, Nixon LS, et al. Inflammatory response and body composition in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(8):1414–1418. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.8.2008109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pitta F, Troosters T, Spruit MA, Probst VS, Decramer M, Gosselink R. Characteristics of physical activities in daily life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):972–977. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200407-855OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Decramer M, Gosselink R, Troosters T, Verschueren M, Evers G. Muscle weakness is related to utilization of health care resources in COPD patients. Eur Respir J. 1997;10(2):417–423. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10020417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swallow EB, Reyes D, Hopkinson NS, et al. Quadriceps strength predicts mortality in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2007;62(2):115–120. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.062026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dentener MA, Creutzberg EC, Schols AM, et al. Systemic anti-inflammatory mediators in COPD: increase in soluble interleukin 1 receptor II during treatment of exacerbations. Thorax. 2001;56(9):721–726. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.9.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacNee W, Rahman I. Is oxidative stress central to the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Trends Mol Med. 2001;7(2):55–62. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)01912-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koechlin C, Maltais F, Saey D, et al. Hypoxaemia enhances peripheral muscle oxidative stress in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2005;60(10):834–841. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.037531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watz H, Waschki B, Meyer T, Magnussen H. Physical activity in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(2):262–272. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00024608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engelen MP, Schols AM, Baken WC, Wesseling GJ, Wouters EF. Nutritional depletion in relation to respiratory and peripheral skeletal muscle function in out-patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 1994;7(10):1793–1797. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07101793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Theriault ME, Pare ME, Maltais F, Debigare R. Satellite cells senescence in limb muscle of severe patients with COPD. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Theriault ME, Pare ME, Lemire BB, Maltais F, Debigare R. Regenerative defect in vastus lateralis muscle of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2014;15(1):35. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabinovich RA, Drost E, Manning JR, et al. Genome-wide mRNA expression profiling in vastus lateralis of COPD patients with low and normal fat free mass index and healthy controls. Respir Res. 2015;16:1. doi: 10.1186/s12931-014-0139-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lakhdar R, Drost EM, MacNee W, Bastos R, Rabinovich RA. 2D-DIGE proteomic analysis of vastus lateralis from COPD patients with low and normal fat free mass index and healthy controls. Respir Res. 2017;18(1):81. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0525-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niida H, Nakanishi M. DNA damage checkpoints in mammals. Mutagenesis. 2006;21(1):3–9. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gei063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Deursen JM. The role of senescent cells in ageing. Nature. 2014;509(7501):439–446. doi: 10.1038/nature13193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabai VL, Sherman MY, Yaglom JA. HSP72 depletion suppresses gammaH2AX activation by genotoxic stresses via p53/p21 signaling. Oncogene. 2010;29(13):1952–1962. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barreiro E. Protein carbonylation and muscle function in COPD and other conditions. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2014;33(3):219–236. doi: 10.1002/mas.21394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coppé J-P, Patil CK, Rodier F, et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(12):2853–2868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jang YC, Sinha M, Cerletti M, Dall’Osso C, Wagers AJ. Skeletal muscle stem cells: effects of aging and metabolism on muscle regenerative function. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011;76:101–111. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2011.76.010652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report. GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(5):557–582. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schols AM, Broekhuizen R, Weling-Scheepers CA, Wouters EF. Body composition and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(1):53–59. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cawthon RM, Smith KR, O’Brien E, Sivatchenko A, Kerber RA. Association between telomere length in blood and mortality in people aged 60 years or older. Lancet. 2003;361(9355):393–395. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saunders L, Verdin E. Sirtuins: critical regulators at the crossroads between cancer and aging. Oncogene. 2007;26(37):5489–5504. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lombard DB, Schwer B, Alt FW, Mostoslavsky R. SIRT6 in DNA repair, metabolism, and ageing. J Intern Med. 2008;263(2):128–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01902.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bosch-Presegué L, Vaquero A. Sirtuins in stress response: guardians of the genome. Oncogene. 2014;33(29):3764–3775. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang R-H, Sengupta K, Li C, et al. Impaired DNA damage response, genome instability, and tumorigenesis in SIRT1 mutant mice. Cancer Cell. 2008;14(4):312–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakamaru Y, Vuppusetty C, Wada H, et al. A protein deacetylase SIRT1 is a negative regulator of metalloproteinase-9. FASEB J. 2009;23(9):2810–2819. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-125468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takasaka N, Araya J, Hara H, et al. Autophagy induction by SIRT6 through attenuation of insulin-like growth factor signaling is involved in the regulation of human bronchial epithelial cell senescence. J Immunol. 2014;192(3):958–968. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freund A, Patil CK, Campisi J. p38MAPK is a novel DNA damage response-independent regulator of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. EMBO J. 2011;30(8):1536–1548. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim JS, Kim EJ, Kim HJ, Yang JY, Hwang GS, Kim CW. Proteomic and metabolomic analysis of H2O2-induced premature senescent human mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46(6):500–510. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fermoselle C, Rabinovich R, Ausin P, et al. Does oxidative stress modulate limb muscle atrophy in severe COPD patients? Eur Respir J. 2012;40(4):851–862. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00137211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agusti A, Morla M, Sauleda J, Saus C, Busquets X. NF-kappaB activation and iNOS upregulation in skeletal muscle of patients with COPD and low body weight. Thorax. 2004;59(6):483–487. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.017640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rabinovich RA, Ardite E, Troosters T, et al. Reduced muscle redox capacity after endurance training in COPD patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(7):1114–1118. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.7.2103065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rabinovich RA, Ardite E, Mayer AM, et al. Training depletes muscle glutathione in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and low body mass index. Respiration. 2006;73(6):757–761. doi: 10.1159/000094395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Itoh T, Nagaya N, Yoshikawa M, et al. Elevated plasma ghrelin level in underweight patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(8):879–882. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200310-1404OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burova E, Borodkina A, Shatrova A, Nikolsky N. Sublethal oxidative stress induces the premature senescence of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from endometrium. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:474931. doi: 10.1155/2013/474931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Childs BG, Baker DJ, Kirkland JL, Campisi J, van Deursen JM. Senescence and apoptosis: dueling or complementary cell fates? EMBO Rep. 2014;15(11):1139–1153. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agusti AG, Sauleda J, Miralles C, et al. Skeletal muscle apoptosis and weight loss in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(4):485–489. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2108013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Puente-Maestu L, Perez-Parra J, Godoy R, et al. Abnormal transition pore kinetics and cytochrome C release in muscle mitochondria of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40(6):746–750. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0289OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pardo PS, Boriek AM. The physiological roles of Sirt1 in skeletal muscle. Aging. 2011;3(4):430–437. doi: 10.18632/aging.100312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]