Abstract

Objectives

NHS England recently announced a consultation seeking to discourage the use of treatments it considers to be low-value. We set out to produce an interactive data resource to show savings in each NHS general practice and to assess the current use of these treatments, their change in use over time, and the extent and reasons for variation in such prescribing.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis.

Setting

English primary care.

Participants

English general practices.

Main outcome measures

We determined the cost per 1000 patients for prescribing of each of 18 treatments identified by NHS England for each month from July 2012 to June 2017, and also aggregated over the most recent year to assess total cost and variation among practices. We used mixed effects linear regression to determine factors associated with cost of prescribing.

Results

Spend on low-value treatments was £153.5 m in the last year, across 5.8 m prescriptions (mean, £26 per prescription). Among individual treatments, liothyronine had the highest prescribing cost at £29.6 m, followed by trimipramine (£20.2 m). Over time, the overall total number of low-value prescriptions decreased, but the cost increased, although this varied greatly between treatments. Three treatment areas increased in cost and two increased in volume, all others reduced in cost and volume. Annual practice level spending varied widely (median, £2262 per thousand patients; interquartile range £1439 to £3298). Proportion of patients over 65 was strongly associated with low-value prescribing, as was Clinical Commissioning Group. Our interactive data tool was deployed to OpenPrescribing.net where monthly updated figures and graphs can be viewed.

Conclusions

Prescribing of low-value treatments is extensive but varies widely by treatment, geographic area and individual practice. Despite a fall in prescription numbers, the overall cost of prescribing for low-value items has risen. Prescribing behaviour is clustered by Clinical Commissioning Group, which may represent variation in the optimisation efficiency of medicines, or in some cases access inequality.

Keywords: NHS England, low-priority, prescribing, epidemiology

Introduction

In July 2017, NHS England announced a list of 19 ‘low-value’ treatments, which in their view should not routinely be prescribed in primary care, for wider consultation.1 The stated goal of the consultation was to reduce unwarranted variation, provide clear guidance and reduce unnecessary spending.2 The treatments listed were regarded as either ineffective, harmful or low-value. The list of treatments consists of: co-proxamol, dosulepin, doxazosin modified release, fentanyl immediate release, glucosamine and chondroitin, gluten-free products, homeopathy, lidocaine plasters, liothyronine, lutein and antioxidants, omega-3 fatty acid compounds, oxycodone and naloxone combination product, paracetamol and tramadol combination, perindopril arginine, rubefacients, tadalafil once daily, travel vaccines, trimipramine and herbal treatments.

The reasons for identifying each of the treatments as low-priority are explained by NHS England in their guidance document. Examples include: glucosamine and chondroitin, which are prescribed for osteoarthritis associated pain, but have only weak evidence of efficacy and are specifically recommended against by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence;3 doxazosin modified release, which is around six times the cost of doxazosin immediate release, but without known benefits; omega-3 fatty acid compounds, which are thought to have limited efficacy and co-proxamol, a painkiller which was withdrawn in 2005 after safety concerns, but continues to be prescribed ‘off license’ at very high cost.

In order to facilitate informed discussion of this topic, we aimed to summarise the current state of prescribing of these treatments in England in terms of overall spending, trends over time, regional variation and individual practice-level variation. We also aimed to determine what practice level factors are associated with high prescribing of these low-value treatments. Lastly, we set out to add accessible measures describing the use of these low-value treatments to our widely used OpenPrescribing.net service, which provides open access to monthly data on treatments prescribed in each individual NHS general practice.

Methods

Study design

Our analysis is reported in compliance with the STROBE statement.4 It was a retrospective cohort study incorporating English general practices, measuring variation in prescribing of low-value treatments over time, geographically and determining factors associated with the total cost of prescribing at the practice level. We use mixed effects linear regression to investigate correlation of total low-value prescribing cost with various practice characteristics. The low-priority treatments included are: co-proxamol, dosulepin, doxazosin modified release, fentanyl immediate release, glucosamine and chondroitin, gluten-free products, homeopathy, lidocaine plasters, liothyronine, lutein and antioxidants, omega-3 fatty acid compounds, oxycodone and naloxone combination product, perindopril arginine, rubefacients, tadalafil once daily, paracetamol and tramadol combination, travel vaccines and trimipramine.

Setting and data

We used data from our OpenPrescribing.net project, which imports prescribing data from the monthly data files published by NHS Digital.5 These data files contain data on cost and volume prescribed for each drug, dose and preparation, for each month, for each English general practice. We identified all prescribing for each of the low-value treatments in each month and generated the composite prescribing measure described below. Each treatment was identified using British National Formulary codes (see online Appendix B for full code list). We also matched the prescribing data with publicly available demographic data on practices from Public Health England.6 These demographic data provided a means to stratify the rates of low-value prescribing to look at reasons for its variation at the practice level. Only standard English practices labelled within the data as a ‘GP practice’ were included within the analysis; this excluded prescribing in non-standard settings such as prisons. In addition, to exclude practices that are no longer active, those without a 2015/2016 Quality and Outcomes Framework score (in order to remove likely inactive practices) and those with a list size under 1000 were excluded. Quality and Outcomes Framework is a performance management metric used for general practitioners within the NHS, produced by NHS Digital. The composite score used here is made up of many procedural and outcome-based metrics, measuring factors such as the existence of disease registers and percentage of patient groups reaching specific clinical targets. Using largely inclusive criteria such as this reduced the likelihood of obtaining a biased sample. Of the 7605 standard general practices within the data, we included 7489 practices in the analysis, having excluded 110 practices that had fewer than 1000 registered patients, and a further six practices that did not have complete data.

Total cost of low-priority prescribing

For each low-priority treatment, we calculated the total number of prescriptions, total cost and cost per prescription for the period July 2015 to June 2016, and July 2016 to June 2017. We used the ‘actual cost’ field rather than ‘net ingredient cost’ and calculated the change in prescription numbers, cost and cost per prescription between the two time periods.

Low-priority measures and composite measure

We developed data queries to identify 18 of the treatments in the NHS Digital primary care prescribing data for England, as held in the OpenPrescribing database. We identified the drugs in the dataset using their British National Formulary codes. Each measure was calculated as the total cost of low-priority items each month for each practice, divided by practice list size, to derive the prescribing cost (British pounds) per thousand patients. The NHS England advice on use of herbal treatments was not included in our analysis as it could not practically be turned into a series of British National Formulary codes. We then generated a composite measure of all low-priority prescribing, which was defined as the total cost of all low-priority treatments for each practice, divided by each practice list size to produce a rate of cost per 1000 patients. For parts of the analysis where monthly data were not required (i.e. everything except monthly trends), and in order to smooth prescribing rates over a year, we aggregated 12 months together to generate a rate of cost per 1000 patient years.

Geographical variation at Clinical Commissioning Group level

For each low-priority prescribing measure, rates were aggregated by grouping each practice to its parent Clinical Commissioning Group and then described using a map in which each Clinical Commissioning Group’s prescribing was represented using a colour spectrum.

Monthly trends and variation across practices

For each low-priority prescribing measure, we described five years of monthly trends between July 2012 and June 2017 by calculating deciles at practice level for each month and plotting these deciles. We also used a histogram to describe the distribution of low-priority prescribing volume among practices.

Factors associated with low-value prescribing

We built a linear regression model to assess the extent to which variation in such prescribing was correlated with: composite Quality and Outcomes Framework score; practice list size (calculated as mean list size over the most recent year); Index of Multiple Deprivation score; patients with a long-term health condition (%); patients aged over 65 years (%); and whether each practice is a ‘dispensing practice’ with an in-house pharmacy service (yes or no). We used the total cost of all low-priority prescribing per 1000 patients, aggregated over the previous year as the dependent variable.

We created categorical variables from the available demographic data and used these categories to stratify the rate of low-priority prescribing according to the factors defined above. These factors were also entered into a linear regression model, then a mixed effects linear regression model with low-priority prescribing rate as the dependent variable, the above variables as fixed effect independent variables and the parent Clinical Commissioning Group of each practice as a random effect variable. Prescribing and other practice quality measures were divided a priori into quintiles for analysis, except for existing binary variables (i.e. dispensing practice status). This was done for ease of interpretation and to allow for variables having a non-linear effect on prescribing cost. Practices with missing data for a particular variable were not included in models containing that variable. From the resulting model, estimates of the change in spending were calculated, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. The level of missing data was determined and reported for each variable (reported in online Appendix C).

Interactive data tool

We imported all data onto OpenPrescribing.net and made a series of 19 standard measures, one for each of the treatments plus an ‘omnibus’ measure, which aggregates all the low-priority treatments together. Measures were calculated for each month as the total cost of the treatment divided by the population list size. Here, we report on the subsequent website access summary statistics and media coverage.

Software and reproducibility

Data management was performed using Google BigQuery and Python, with analysis carried out using Stata 13.1. Data and analytic code can be found here: https://figshare.com/s/1acc3609a854825cd930

Results

In this paper, we report on the aggregate of all low-priority prescribing combined and illustrative examples of trends and variation from individual treatments; our detailed report on trends and variation for prescribing of all individual treatments in the NHS England consultation can be found in online Appendix A. Individual Clinical Commissioning Group and practice level data can be explored further on the OpenPrescribing.net website, where all data are current and updated on a monthly cycle.

Total expenditure for low-priority treatments

There was £153.5 m of total expenditure across all low-priority treatments between July 2016 and June 2017, from a total of 5.8 m items (Table 1). This represents £2.63 per person per year (total list size population 58.3 m), and around 1.7% of the overall NHS spend on primary care prescribing (£9.2bn in 2016, a slightly different time period to that used in our analysis).7 For individual treatments, there was a large range of total spend for each treatment, from £78k (homeopathy) to £29.6 m (liothyronine). The overall cost per item for all treatments was £26.28, which ranged from £2.55 (dosulepin) to £411.97 (liothyronine).

Table 1.

Total prescriptions, cost and cost per prescription in preceding two years for ‘low-priority’ treatments, along with change between 2015/2016 and 2016/2017 in English primary care.

| July 2015 to June 2016 |

July 2016 to June 2017 |

Change 2015/2016 to 2016/2017 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Cost | Cost per item | Items | Cost | Cost per item | Change in items | Change in cost | Change in cost per item | |

| Total | 6,813,926 | £148,941,731 | £21.86 | 5,840,951 | £153,483,224 | £26.28 | -972,975 | £4,541,493 | £4.42 |

| Liothyronine | 76,305 | £25,881,475 | £339.18 | 71,741 | £29,555,306 | £411.97 | −4564 | £3,673,832 | £72.79 |

| Trimipramine | 69,935 | £12,044,068 | £172.22 | 59,420 | £20,214,868 | £340.20 | −10,515 | £8,170,800 | £167.99 |

| Gluten-free products | 1,620,000 | £23,283,054 | £14.37 | 1,295,581 | £18,668,896 | £14.41 | −324,419 | −£4,614,159 | £0.04 |

| Lidocaine plasters | 241,457 | £16,944,866 | £70.18 | 258,696 | £17,970,517 | £69.47 | 17,239 | £1,025,651 | −£0.71 |

| Rubefacients | 1,654,125 | £11,716,651 | £7.08 | 1,481,642 | £11,271,027 | £7.61 | −172,483 | −£445,624 | £0.52 |

| Tadalafil once daily | 172,888 | £10,062,878 | £58.20 | 181,085 | £10,635,133 | £58.73 | 8197 | £572,255 | £0.53 |

| Fentanyl immediate release | 34,075 | £9,916,801 | £291.03 | 34,852 | £10,181,529 | £292.14 | 777 | £264,728 | £1.11 |

| Co-proxamol | 66,103 | £5,825,171 | £88.12 | 47,778 | £7,601,035 | £159.09 | −18,325 | £1,775,863 | £70.97 |

| Doxazosin modified release | 788,396 | £8,183,086 | £10.38 | 621,037 | £6,599,282 | £10.63 | −167,359 | −£1,583,804 | £0.25 |

| Omega-3 fatty acid compounds | 227,378 | £6,276,064 | £27.60 | 191,250 | £5,412,322 | £28.30 | −36,128 | −£863,742 | £0.70 |

| Oxycodone and naloxone combination | 74,489 | £4,823,104 | £64.75 | 68,337 | £4,461,059 | £65.28 | −6152 | −£362,045 | £0.53 |

| Travel vaccines | 322,368 | £5,218,067 | £16.19 | 236,840 | £3,613,876 | £15.26 | −85,528 | −£1,604,191 | −£0.93 |

| Dosulepin | 984,364 | £2,954,573 | £3.00 | 871,162 | £2,222,722 | £2.55 | −113,202 | −£731,851 | −£0.45 |

| Paracetamol and tramadol combination | 132,586 | £1,987,369 | £14.99 | 110,247 | £1,675,191 | £15.19 | −22,339 | −£312,178 | £0.21 |

| Lutein and antioxidants | 172,549 | £1,653,524 | £9.58 | 157,650 | £1,540,941 | £9.77 | −14,899 | −£112,583 | £0.19 |

| Perindopril arginine | 132,901 | £1,537,858 | £11.57 | 119,421 | £1,395,133 | £11.68 | −13,480 | −£142,725 | £0.11 |

| Glucosamine and chondroitin | 36,291 | £536,626 | £14.79 | 28,237 | £386,468 | £13.69 | −8054 | −£150,158 | −£1.10 |

| Homeopathy | 7716 | £96,497 | £12.51 | 5975 | £77,921 | £13.04 | −1741 | −£18,576 | £0.54 |

Trends in low-value prescribing

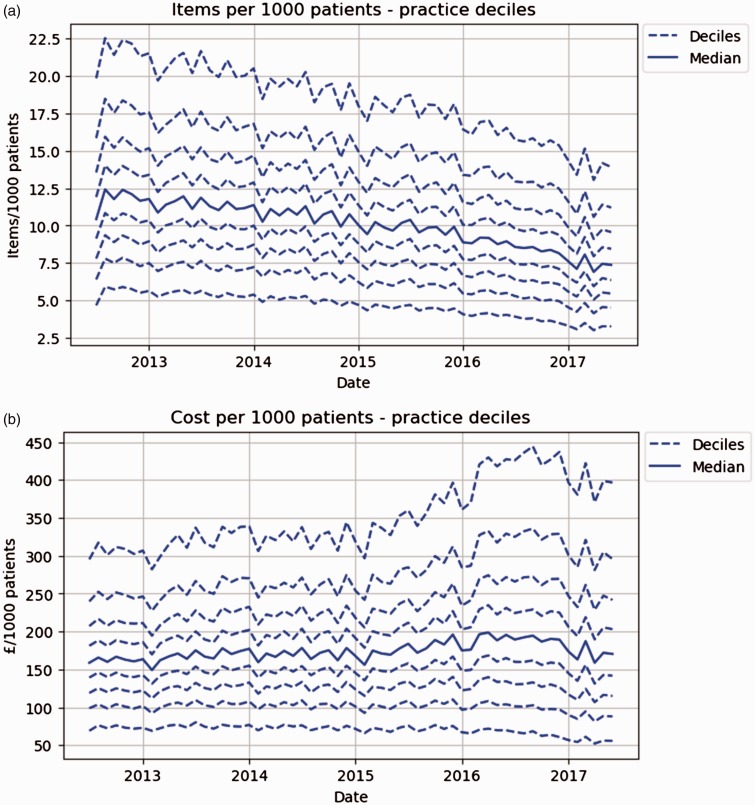

There has been an overall trend towards fewer low-value items being prescribed over time (Figure 1(a)), with almost one million fewer prescriptions (14% lower) between July 2016 and June 2017, compared to the previous year (Table 1). Despite the consistent downward trend in items, costs have risen, increasing by £4.5 m (3% higher) when comparing 2016/2017 with 2015/2016 (Table 1). While the cost per item has remained stable for most treatments, for liothyronine, trimipramine and co-proxamol, the cost per item has risen dramatically (by £73, £168 and £71 per prescription, respectively). In most individual practices, costs have risen (Figure 1(b)), although the value for higher deciles has risen more than that in lower deciles, where costs are relatively steady. For the individual measures, most are falling in prescribing volume, except for lidocaine plasters, tadalafil once daily and fentanyl immediate release, where small increases were observed between 2015/2016 and 2016/2017 (Table 1 and online Appendix A). Some costs have fallen a great deal in this time period (e.g. travel vaccines have fallen by 44%), but others have risen dramatically (e.g. trimipramine national costs have increased by 40%).

Figure 1.

Total items (a) and cost (b) of prescribing for all low-value treatments combined over time in English primary care. Solid line is the median and surrounding dashed lines are deciles.

Variation among practices and Clinical Commissioning Groups

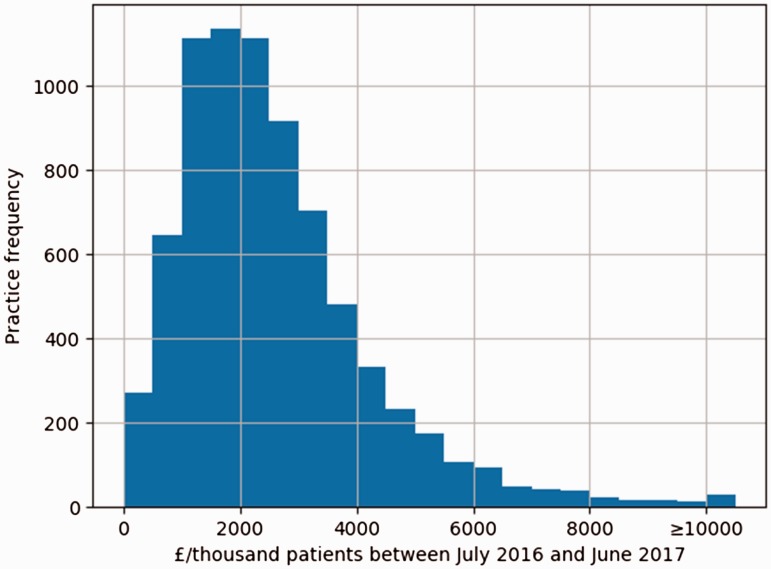

The distribution of overall spending on low-priority treatments among practices is shown in Figure 2. Around half of practices are clustered within £1000 of the median spend per 1000 patients (median, £2262; interquartile range £1439 to £3298). However, some practices spend very little per 1000 patients, including 261 practices that spend less than £500 per 1000 patients per year and 19 practices that prescribed zero items during this period; while 588 practices spend more than £5000 per 1000 patients per year.

Figure 2.

Distribution of total low-priority spending per practice, £ per 1000 patients per practice, between July 2016 and June 2017. Values over £10,000 are aggregated into the final column.

Prescribing of individual treatments

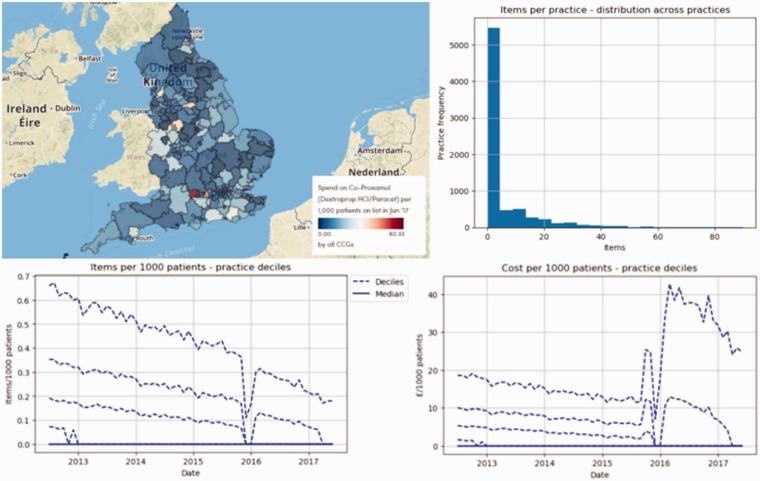

There are three treatments (liothyronine, trimipramine and co-proxamol) where the volume of prescribing has decreased, but the total cost has dramatically increased (Table 1). This is shown in more detail in Figure 3 for co-proxamol, and in online Appendix A for all individual treatments. Co-proxamol was withdrawn in 2005 and subsequently removed from the drug tariff. Prescribing has continued ‘off label’, in diminishing volumes, but the cost of the drug has risen dramatically over time: of note, there was a shortage at the end of 2015,8 hence the sudden drop in prescribing volume at this time, but with no reduction in linear downward trend in volume prescribed.

Figure 3.

Variation in prescribing of co-proxamol, from top left to bottom right: variation in cost geographically at Clinical Commissioning Group level (£ per 1000 patients, June 2017); variation in items across practices within the last year; practice level variation in items over time and practice level variation in cost over time.

Co-proxamol is also an example of a treatment with significant costs to the NHS that is only prescribed by a small proportion of NHS practices. There are many other individual treatments where over half of practices prescribe zero items per month, including: fentanyl immediate release, glucosamine and chondroitin, homeopathy, liothyronine, lutein and antioxidants, oxycodone and naloxone combination, paracetamol and tramadol combination, perindopril arginine and trimipramine. Full details on prescribing of all these treatments can be found in online Appendix A.

Factors associated with low-value prescribing spend

Overall, practices with a good Quality and Outcomes Framework score (highest quintile) spent slightly more per 1000 patients than those with a poor score in univariate analysis (£165 more for the highest score group vs. the lowest score 95% confidence interval £46 to £285). However, this effect is reversed in multivariable modelling, with only the ‘best’ vs. ‘worst’ comparison being significant. Being in an area with a more deprived Index of Multiple Deprivation score was associated with decreased spending in the univariable analysis, but not after multivariable adjustment. Practices with larger list sizes were associated with a slight increase in low-priority spending per 1000 patients (£352 more per 1000 patients in the largest practice group vs. the smallest, multivariable CI, £238 to £467). Dispensing practices also spent slightly more (£255) per 1000 patients than non-dispensing practices (multivariable CI, £133 to £377).

The percentage of patients aged over 65 years had by far the strongest association with low-priority spending, of the factors assessed (Table 2). Practices with the highest percentage of patients aged over 65 years (>22.5%) spent £1302 more than those with the lowest percentage (<10.8%) after adjustment (multivariable CI, £1139 to £1466). While the percentage of patients with a long-term health condition had a moderately strong association on low-priority spending in the univariable analysis, this effect was much reduced after multivariable modelling (Table 2). Within the mixed effects linear regression model, Clinical Commissioning Group as a random effect was found to be significantly associated with prescribing cost (p < 0.0001), indicating clustering of spend on low-value treatments by Clinical Commissioning Group.

Table 2.

Stratification and modelling of annual low-priority cost between July 2016 and June 2017.

| Quintile/category boundaries | Mean cost (£) per 1000 people | Change in cost (£)a | 95% Confidence interval (£) | Multivariable change in cost (£)b | 95% Confidence interval (£) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality and Outcomes Framework score (max = 559) | <522 | 2494 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 522 to 541 | 2553 | 58 | −62 | 178 | −33 | −143 | 76 | |

| 541 to 550 | 2578 | 84 | −36 | 203 | −87 | −197 | 24 | |

| 550 to 556 | 2655 | 160 | 41 | 280 | −53 | −164 | 59 | |

| >556 | 2660 | 165 | 46 | 285 | −156 | −271 | −41 | |

| Index of Multiple Deprivation | Least deprived | 2859 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| | | 2754 | −105 | −225 | 14 | −108 | −224 | 9 | |

| | | 2579 | −280 | −400 | −161 | −125 | −253 | 2 | |

| | | 2413 | −446 | −565 | −327 | −150 | −290 | −9 | |

| Most deprived | 2337 | −522 | −641 | −403 | −114 | −274 | 46 | |

| Practice list size | <3784 | 2340 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 3785 to 5796 | 2531 | 191 | 72 | 311 | 220 | 112 | 329 | |

| 5798 to 8018 | 2666 | 326 | 207 | 446 | 279 | 169 | 389 | |

| 8020 to 11,165 | 2747 | 408 | 288 | 527 | 364 | 252 | 476 | |

| >11,165 | 2656 | 316 | 197 | 436 | 352 | 238 | 467 | |

| Dispensing practice? | No | 2512 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 3073 | 560 | 450 | 671 | 255 | 133 | 377 | |

| % of patients over 65 | <10.8% | 1788 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 10.8% to 15.4% | 2411 | 623 | 508 | 738 | 556 | 438 | 674 | |

| 15.4% to 18.8% | 2642 | 854 | 739 | 969 | 801 | 669 | 933 | |

| 18.8% to 22.4% | 2910 | 1121 | 1006 | 1236 | 1040 | 897 | 1184 | |

| >22.4% | 3191 | 1402 | 1287 | 1517 | 1302 | 1139 | 1466 | |

| % of patients with a long-term health condition | <47.0% | 2113 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 47.0% to 51.5% | 2557 | 444 | 326 | 563 | 194 | 82 | 307 | |

| 51.5% to 55.3% | 2680 | 567 | 448 | 686 | 221 | 106 | 337 | |

| 55.4% to 59.7% | 2757 | 645 | 526 | 763 | 165 | 44 | 285 | |

| >59.7% | 2839 | 726 | 607 | 844 | 216 | 89 | 342 | |

Note: Each independent variable is split into quintiles (except for the binary dispensing practice status), linear regression modelling was performed to determine the change in cost associated with being in different quintiles of each variable.

Linear regression.

Mixed effects linear regression, adjusted for all other variables in table as fixed effects, plus Clinical Commissioning Group as a random effect.

Interactive data tool

The online data tool to make the data more accessible for clinicians is now online on the OpenPrescribing website9 and can be explored at individual treatment level as well as practice and Clinical Commissioning Group level. All prescribing data online is updated on a monthly basis in order to remain current. The launch of the website led to various news stories being published10–14 and a good level of engagement with the data, including 1286 pageviews (983 unique pageviews) between the launch date (2 October 2017) and the most recent extraction of page view data (25 October 2017).

Discussion

Summary of findings

We found that prescribing of treatments identified as low-priority by NHS England cost a total of £153.5 m within the last year or 1.7% of total NHS spending on primary care prescribing.7 Despite a decrease in the total number of items prescribed over recent years, the total cost of these prescriptions has increased due to a large increase in the cost per prescription for some treatments. There was wide variation in the total cost of prescribing among the identified treatments over the most recent year, from £29.6 m for liothyronine to just £77,921 (and declining) for homeopathic products. The strongest association with the level of prescribing cost at practice level was with the proportion of patients aged over 65 years. This is perhaps not surprising given that older patients are generally more likely to receive prescriptions. Given the recent trends in treatments such as co-proxamol, glucosamine, homeopathy and trimipramine, it seems conceivable that prescribing of these treatments could approach zero within a few years. Our online interactive tool9 will continue to provide useful and up-to-date information (updated monthly) on the continuing prescribing of these treatments.

Strengths and weaknesses

We included all typical practices in England, thus minimising the potential for obtaining a biased sample. We used real prescribing and spending data which are sourced from pharmacy claims and therefore did not need to rely on the use of surrogate measures. Using these data rather than survey data also eliminates the possibility of recall bias. The analysis presented here uses more up-to-date data than that used in the NHS England guidance document,2 and further updates to the cost data can be found on the OpenPrescribing site.

We excluded a small number of practices without a Quality and Outcomes Framework score, as many of these practices are no longer active and we reasoned that any practice not participating in Quality and Outcomes Framework would be less representative of a ‘typical’ general practice. This may have excluded a small number of practices that opened since the 2015/2016 Quality and Outcomes Framework scores were calculated; however, there are no grounds to believe that such practices would have been systematically different to the rest of our population with respect to low-value prescribing or factors associated with it. Due to a large sample size and large effect sizes, we obtained a high level of statistical significance in many of the associations we observed.

Policy implications and interpretation

There are important implications to be considered in terms of making cost-savings in prescribing. Co-proxamol, liothyronine and trimipramine illustrate a concerning phenomenon, where despite successful efforts to limit prescribing numbers, costs have risen sharply. For example, co-proxamol is expensive as it was removed from the drug tariff, meaning that any prescriptions for it have to be sourced as a ‘special’ order.15 There is limited regulation of the cost of such special orders, making real world cost-savings on such drugs difficult until there are a very small number of total prescriptions.

The prescribing rate of liothyronine has been comparatively steady in recent years, though less than half practices prescribe it. However, the price has increased dramatically since the drug began being sold as a generic. It was noted in 2015 that the price had increased 40-fold to £152 for 28 tablets;16 however, our latest data show this to have further increased to £218 per 28 tablets/capsules (or £412 mean per prescription). The reason for this is likely to be lack of sufficient competition in the market, with its only UK manufacturer having been subject to investigation by the UK competition commission.17 It is possible that some manufacturers have increased prices for drugs such as trimipramine in response to decreased demand. It is also possible that such situations could be aided somewhat by provisions within the Health Service Medical Supplies (Costs) Bill.18

It is important to note that there is some variability in agreement on which treatments within this list should be considered low-value. For example, it is widely agreed that the evidence for the efficacy of glucosamine is limited19 and it is not recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.3 Liothyronine, conversely, has been restricted largely due to high cost rather than lack of efficacy. Similarly, gluten-free food prescribing is a controversial issue: guidelines and clinicians broadly agree that prescribing staple gluten-free foods such as bread and flour to patients with coeliac disease aids in adherence to a gluten-free diet, but prescribing has recently declined due to cost-saving measures initiated by NHS England and mediated by Clinical Commissioning Group policies.

Lastly, we are aware of no previous published work showing that Clinical Commissioning Group policy has an impact on prescribing. Many maps in online Appendix A show a large degree of variation according to Clinical Commissioning Group: while some variation may be due to demographic differences, it seems likely that much is due to variation in Clinical Commissioning Group policy. Substantiating this, Clinical Commissioning Group was significantly associated with prescribing behaviour in our mixed effects model. For treatments with limited efficacy, this merely represents Clinical Commissioning Groups varying in how quickly they can reduce prescribing and its resulting costs. However, for efficacious treatments like gluten-free foods and liothyronine, such policy variation represents inequality of access to treatment.

Conclusions

The detailed analysis of trends and variation in low-value prescribing presented here should be used to inform future debate about the use of such treatments. A certain proportion of current variation in many of the observed treatments is likely to be due to differences in policy between different Clinical Commissioning Groups and practices, rather than clinical need.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for Trends and variation in prescribing of low-priority treatments identified by NHS England: a cross-sectional study and interactive data tool in English primary care by Alex J Walker, Helen J Curtis, Seb Bacon, Richard Croker and Ben Goldacre in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine

Declarations

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare the following: BG has received research funding from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, the Wellcome Trust, the Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, the NHS National Institute for Health Research School of Primary Care Research, the Health Foundation and the World Health Organization; he also receives personal income from speaking and writing for lay audiences on the misuse of science. AJW, HJC, SB and RC are employed on BG’s grants for the OpenPrescribing project. RC is employed by a clinical commissioning group to optimise prescribing and has received income as a paid member of advisory boards for Martindale Pharma, Menarini Farmaceutica Internazionale SRL and Stirling Anglian Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

Funding

This work is supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford, by a Health Foundation grant (Award Reference Number 7599) and by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School of Primary Care Research (SPCR) grant (Award Reference Number 327). Funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Ethical approval

This study uses exclusively open, publicly available data and therefore no ethical approval was required.

Guarantor

BG.

Contributorship

AJW and BG conceived and designed the study. AJW and HJC collected and analysed the data with methodological and interpretation input from RC, SB and BG. AJW drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript. SB was lead engineer on the associated website resource with input from RC, AJW, BG and HJC.

Acknowledgements

Lead engineer on the original OpenPrescribing tool was Anna Powell-Smith.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Janet Krska and Julie Morris.

References

- 1.NHS England. Items which should not routinely be prescribed in primary care: a consultation on guidance for CCGs. See www.engage.england.nhs.uk/consultation/items-routinely-prescribed/supporting_documents/Consultation%20Items%20not%20routinely%20prescribed%20in%20primary%20care%20FINAL1809.pdf (last checked 17 October 2017).

- 2.NHS England. Items which should not routinely be prescribed in primary care: guidance for CCGs. See www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/items-which-should-not-be-routinely-precscribed-in-pc-ccg-guidance.pdf (last checked 18 January 2016).

- 3.NICE. Osteoarthritis: care and management|guidance and guidelines|NICE. See www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg177/chapter/1-Recommendations#nutraceuticals (last checked 16 October 2017).

- 4.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gtzsche PC, Van-denbroucke JP. for the STROBE Initiative. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 2014; 12: 1495–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NHS Digital prescribing data. See http://content.digital.nhs.uk/gpprescribingdata (last checked 14 March 2017).

- 6.Public Health England – public health profiles. See https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/general-practice/data (last checked 31 July 2017).

- 7.Prescription cost analysis, England. See http://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB23631 (2016, last checked 13 October 2017).

- 8.Gregoriou M. Quantum announces co-proxamol shortage. See www.thegoodhealthsuite.co.uk/Pharmacist/specials/787-quantum-announces-co-proxamol-shortage (last checked 26 October 2017).

- 9.NHS England low priority treatment – all low priority treatments by all CCGs|OpenPrescribing. See https://openprescribing.net/measure/lpzomnibus/ (last checked 26 October 2017).

- 10.Devlin A. GPs spend millions on treatments identified as a waste of public cash. The Times, 2 October 2017. See www.thetimes.co.uk/article/gps-spend-millions-on-treatments-identified-as-a-waste-of-public-cash-m7j0qfl38 (last checked 26 October 2017).

- 11.Nick McDermott HE. More than 700 GPs prescribed homeopathic treatments last year. The Sun. See www.thesun.co.uk/news/4590872/more-than-700-gps-prescribed-homeopathic-treatments-last-year/ (2017, last checked 26 October 2017).

- 12.Waugh R. Hundreds of GPs are still prescribing ‘rubbish’ homeopathic treatments. See https://uk.news.yahoo.com/hundreds-gps-still-prescribing-rubbish-homeopathic-treatments-083927559.html (2017, last checked 26 October 2017).

- 13.New website reveals prescribing habits across general practice|Practicebusiness.co.uk. See http://practicebusiness.co.uk/new-website-reveals-prescribing-habits-across-general-practice/ (last checked 26 October 2017).

- 14.Gregory J. 700 GPs prescribed homeopathy in a year. Pulse Today. See www.pulsetoday.co.uk/news/clinical-news/700-gps-prescribed-homeopathy-in-a-year/20035402.article (last checked 26 October 2017).

- 15.GPs told by CCGs to find alternatives for co-proxamol prescriptions. Pulse Today. See www.pulsetoday.co.uk/clinical/prescribing/gps-told-by-ccgs-to-find-alternatives-for-co-proxamol-prescriptions/1/20031058.article?PageNo=4&SortOrder=dateadded&PageSize=10 (last checked 26 October 2017).

- 16.Harwood J. UK Drug 4000% price rise puts spotlight on soaring UK NHS drug costs. BMJ. Epub ahead of print 25 September 2015. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.h5114. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.McConaghie A. Concordia at centre of drug pricing probe. Pharmaphorum. See https://pharmaphorum.com/news/concordia-centre-drug-pricing-probe/ (2016, last checked 26 October 2017).

- 18.Health Service Medical Supplies (Costs) Act 2017 – UK Parliament. See https://services.parliament.uk/bills/2016-17/healthservicemedicalsuppliescosts.html (last checked 16 January 2018).

- 19.Stuber K, Sajko S, Kristmanson K. Efficacy of glucosamine, chondroitin, and methylsulfonylmethane for spinal degenerative joint disease and degenerative disc disease: a systematic review. J Can Chiropr Assoc 2011; 55: 47–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material for Trends and variation in prescribing of low-priority treatments identified by NHS England: a cross-sectional study and interactive data tool in English primary care by Alex J Walker, Helen J Curtis, Seb Bacon, Richard Croker and Ben Goldacre in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine