Short abstract

The endogenous neuropeptide opioid growth factor, chemically termed [Met5]-enkephalin, has growth inhibitory and immunomodulatory properties. Opioid growth factor is distributed widely throughout most tissues, is autocrine and paracrine produced, and interacts at the nuclear-associated receptor, OGFr. Serum levels of opioid growth factor are decreased in patients with multiple sclerosis and in animals with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis suggesting that the OGF-OGFr pathway becomes dysregulated in this disease. This study begins to assess other cytokines that are altered following opioid growth factor or low-dose naltrexone modulation of the OGF-OGFr axis in mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis using serum samples collected in mice treated for 10 or 20 days and assayed by a multiplex cytokine assay for inflammatory markers. Cytokines of interest were validated in mice at six days following immunization for experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. In addition, selected cytokines were validated with serum from MS patients treated with low-dose naltrexone alone or low-dose naltrexone in combination with glatiramer acetate (Copaxone®). Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice had elevated levels of 7 of 10 cytokines. Treatment with opioid growth factor or low-dose naltrexone resulted in elevated expression levels of the IL-6 cytokine, and significantly reduced IL-10 values, relative to saline-treated experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice. TNF-γ values were increased in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice relative to normal, but were not altered by opioid growth factor or low-dose naltrexone. IFN-γ levels were reduced in opioid growth factor- or low-dose naltrexone-treated experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice relative to saline-treated mice at 10 days, and elevated relative to normal values at 20 days. Validation studies revealed that within six days of immunization, opioid growth factor or low-dose naltrexone modulated IL-6 and IL-10 cytokine expression. Validation in human serum revealed markedly reduced IL-6 cytokine levels in MS patients taking low-dose naltrexone relative to standard care. In summary, modulation of the OGF-OGFr pathway regulates some inflammatory cytokines, and together with opioid growth factor serum levels, may begin to form a panel of valid biomarkers to monitor progression of multiple sclerosis and response to therapy.

Impact statement

Modulation of the opioid growth factor (OGF)–OGF receptor (OGFr) alters inflammatory cytokine expression in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). Multiplex cytokine assays demonstrated that mice with chronic EAE and treated with either OGF or low-dose naltrexone (LDN) had decreased expression of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 within 10 days or treatment, as well as increased serum expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6, relative to immunized mice receiving saline. Multiplex data were validated using ELISA kits and serum from MS patients treated with LDN and revealed decreased in IL-6 levels in patients taking LDN relative to standard care alone. These data, along with serum levels of OGF, begin to formulate a selective biomarker profile for MS that is easily measured and effective at monitoring disease progression and response to therapy.

Keywords: IL-6, IL-10, IFN-γ, cytokines, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, opioid growth factor, low-dose naltrexone

Introduction

The etiology and pathophysiology of multiple sclerosis (MS) are unclear despite significant research efforts at both the basic science and clinical levels. In the U.S. alone, healthcare costs approximate $100,000 annually per patient, with lifetime estimates per patient estimated at $4.1 million because of the early onset of disease and associated disability.1 Given that worldwide there are more than 2.5 million individuals have MS,2–4 the burden of MS places it near the top of the list for most costly diseases in the US.4 Many of the FDA-approved disease-modifying therapies (DMT) are expensive,1 have significant side effects, and often require lengthy infusions or painful injections making patients less compliant and seeking alternative therapy. An increasing number of prospective and retrospective studies have shown that individuals with autoimmune disorders including fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, or MS have benefitted from low-dose naltrexone (LDN).5–9 LDN appears to reduce fatigue, lessen pain, and confer a general feeling of well-being.10,11 The mechanisms underlying these changes in patient symptoms are not well understood. Preclinical investigations have shown that modulation of the opioid growth factor (OGF) – OGF receptor (OGFr) regulatory pathway effectively attenuates behavior and neuropathology associated with the mouse model of MS, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE).12 Establishment of mouse models of chronic EAE (CH-EAE) or relapsing-remitting EAE (RR-EAE) has enabled the study of associated behavior, immunology, spinal cord pathology, and endocrinology.6,13–17 Most recently, it has been reported that serum levels of OGF are reduced in mice with EAE,18 and restored in mice receiving LDN treatment.19 In particular, enkephalins are associated with inflammatory responses.20

LDN therapy, shown to reverse the progression of RR-EAE,17,18 works mechanistically by elevating enkephalins that can subsequently interact with OGFr,12 the specific receptor related to growth inhibition by OGF.21 OGF and LDN have also been shown to inhibit proliferation of activated T and B cells in vitro.22,23 OGF inhibits cell replication of T and B cells, stimulated in culture, isolated in vivo, or identified in mice with the chronic progressive form of autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE).22–25

Studies on enkephalins, including OGF, have reported that enkephalins suppress immune responses in clinical studies.5,8,20 Preclinical studies using mouse models of Ch-EAE or RR-EAE have reported that daily therapeutic regimens of direct injections with OGF, or biofeedback stimulation of OGF release following LDN resulted in attenuation of EAE disease, mitigated neuropathology, and restored levels of circulating enkephalins.13–17 Direct injections of OGF beginning either at the time of disease induction13,14 or given following established disease15 reversed the course of Ch-EAE. In mice with RR-EAE, OGF treatment reduced the number of relapses and prolonged the period of remissions in RR-EAE.16,17 A recent study demonstrated positive correlation between serum enkephalin levels and open field activity and sensitivity.18 As enkephalin levels increased, the mice had increased activity and restored sensitivity. Importantly, there was a strong correlation between serum enkephalin levels and clinical behavioral scores, such that as serum levels decreased, behavior became more disrupted, indicating progression of disease.18 LDN treatment of mice with RR-EAE resulted in the stabilization, if not reversal, of behavioral scores17,18 suggesting that the biofeedback mechanism resulting in elevated OGF levels was sufficient to inhibit the inflammatory cell replication22–25 associated with the autoimmune response. In another report measuring serum OGF, it was shown that OGF levels declined in mice within a few days of MOG35–55 immunization prior to the appearance of clinical disease.19 Following LDN treatment, serum OGF levels returned to baseline, and tactile and heat sensitivity was restored in the EAE mice.19 In humans with MS, serum [Met5]-enkephalin levels were reported to be lower relative to non-MS patients; MS patients prescribed LDN had more normal levels.19 LDN therapy had no effect on serum [Met5]-enkephalin or β-endorphin in normal mice. Thus, [Met5]-enkephalin (i.e. OGF) may be a reasonable candidate biomarker for MS, and may signal new pathways for treatment of autoimmune disorders.

Although OGF and LDN can directly inhibit immune system proliferation of T and B cells, little is known about the interactions of OGF and LDN with other cytokine regulatory pathways. A number of preclinical and clinical investigations and reviews have reported changes in gene and protein expression of inflammatory cytokines in rat or mouse models of EAE,26–28 as well as in patients with MS.29,30 In particular, cytokines regulating the balance of Th1, Th2, and Th17 cytokine expression, as well as IFNγ, are implicated as being major factors in pro-inflammatory events and flares.27–29 Parkitny and Younger9 have recently shown that LDN therapy for fibromyalgia reduces expression levels of several pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-12p70, TFN-α, and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (GC-SF).

In this study, we continue our investigation for potential biomarkers, and begin to identify immune regulatory factors that are responsive to modulation of the OGF-OGFr axis by LDN or OGF. Several cohorts of mice were immunized in separate experiments to induce EAE and treated with either OGF or LDN. Whole trunk blood was collected at various times following inoculation of MOG35–55 and serum assayed using a 10-cytokine multiplex assay platform. Selected cytokines that were altered by short-term OGF or LDN therapy were then validated with ELISA kits using serum from humans with MS and prescribed LDN, and EAE mice treated with OGF or LDN. In general, modulation of the OGF-OGFr pathway altered the protein expression of IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and IFN-γ cytokines.

Materials and methods

Induction of EAE and treatment

To induce Ch-EAE, six-to seven-week-old female C57BL/6J mice (stock 000664) from Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME were acclimated for one week prior to being inoculated with an emulsion of 400 μg myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein 35–55 (MOG35–55) dissolved in 0.2 ml sterile phosphate-buffered saline. Incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was supplemented with 750 μg mycobacterium tuberculosis (H37RA, Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI), and adjuvant was mixed with saline containing MOG35–55. Mice were sedated by 3% isoflurane (Vedco, Inc., St. Joseph, MO) for the multiple subcutaneous injections into the flank. A second injection of MOG emulsion was injected into the contralateral flank seven days later. To enhance responsiveness, mice received an intraperitoneal injection of 500 ng pertussis toxin (List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, CA) on days 0 and 2. Some mice received injections of pertussis and Complete Freund’s adjuvant, but not MOG (PTX + CFA group; n = 10), and other mice received only saline injections and were considered “normal” (n = 8). All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institute of Health guidelines on animal care and approved by the Penn State Hershey Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All mice were housed in standard laboratory animal facilities maintained at 21 ± 0.5°C with a relative humidity of 50 ± 10%, with a complete exchange of air 15–18 times per hour, and a 12-h light-dark cycle with no twilight. Food and water were available ad libitum.

MOG35–55 immunized mice were randomly assigned to three groups and injected daily (i.p. 0.1 ml) with 0.1 mg/kg naltrexone (Ch-EAE + LDN; n = 16), 10 mg/kg OGF (Ch-EAE + OGF; n = 16), or sterile saline (n = 16). Both OGF (chemically termed [Met5]-enkephalin) and naltrexone were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO at ≥ 95% purity. All injections were initiated at 0800 h. Mice used in the Multiplex assay were euthanized after 10 or 20 days of treatment corresponding to disease onset and peak disease, respectively.

Clinical disease severity

In order to assess the EAE disease severity at 10 and 20 days post immunization, behavioral observations were completed. Symptoms such as: wobbly gait, tail drag, limb deficits, and righting reflex were scored on a 10-point scale.15 Clinical behavioral scores were noted only at the time of blood collection.

Serum collection and cytokine multiplex assay

On specified days at, 1600 h, mice were humanely euthanized using CO2 asphyxiation; this time was selected to maximize the effect of LDN and the circadian rhythm of cytokines. Mice were exsanguinated through terminal cardiac puncture and whole trunk blood collected, centrifuged at 14,000 r/min at 4°C, and stored at −80°C until assayed. Blood samples from two mice of the same treatment were pooled to order to obtain sufficient serum.

Serum samples were analyzed in duplicate using a Multiplex assay from Meso Scale Diagnostics (Rockville, MD). The V-Plex Mouse Inflammatory Panel 1 assay kit tested for measurable levels of the following analytes: IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, TNFα, IFNγ, and CXCL-1.

Cytokine validation

Data from the Cytokine V-Plex assay were validated in separate experiments using human and mouse blood samples.31

Human blood samples

Human blood samples from volunteering patients enrolled at the Neurology Clinic were obtained through the Institute for Personalized Medicine, Penn State University College of Medicine, Hershey, PA. Specimens were de-identified and assigned sample ID numbers by the coordinator. The consent form used by the Institute for Personalized Medicine for collection of blood from MS patients for research purposes provided medical information on gender, age, and name and length of treatment and disease. Four cohorts of blood samples were assayed including those from MS patients receiving glatiramer acetate (Copaxone®) and LDN, Copaxone® alone, LDN alone, or patients who were considered controls and did not present with autoimmune disorders (non-MS Controls).

EAE mice

Validation of cytokines on day 6 required separate experimental paradigms. Adult female mice were immunized as described, and injected with OGF or LDN beginning at the time of immunization. On day 6 of treatment, mice were euthanized at 1600 h and blood collected. Day 6 was selected as a validation time point because it represented changes in cytokines that occurred prior to any behavioral changes, as well as a timepoint prior to the second immunization occurring on day 7. Day 6 was intentionally selected to provide a broad perspective (days 6, 10, and 20) on cytokine responses to MOG35–55 immunization, as well as any changes in cytokines in response to OGF or LDN therapy. Serum was frozen and tested using ELISA technology specified in the next paragraph. Serum samples from mice treated only with pertussis and Complete Freund’s adjuvant (PTX + CFA), as well as normal non-immunized mice were included.

ELISA assays

Serum levels of IL-6, IL-10, and INF-γ were assayed using ELISA kits (MyBiosource, San Diego, CA). Human interleukin 6 (IL-6) (kit MBS261259) and human interleukin 10 (IL-10) (kit MBS039075) were assayed in duplicate; sensitivity of both kits was 1 pg/ml. Mouse serum levels inflammatory cytokines INF-γ and IL-10 were measured using ELISA kit IL-6 (cat # ELISA kit IL-10 (cat # MBS268184) which had mouse sensitivity of 5 pg/ml and no stated cross-reactivity or mouse INF-γ ELISA kit (cat # MBS252163) with sensitivity of 1 pg/ml and detection range of 15.6–1000 pg/ml, and no stated cross-reactivity. Mouse serum levels for IL-6 were evaluated with the human IL-6 kit. Colorimetric output from the ELISA was read on a Biotek Epoch Plate Reader at 450 nm. Standard curve and concentration data were produced with Gen5 Microplate Reader and Software (Biotek).

Statistical analysis

Mouse blood samples were assayed in duplicate. Data from duplicates were averaged and converted to pg/ml based on the manufacturer’s kit; two or three independent samples were assayed. Baseline (normal) values are presented in Table 1 (means ± standard error of the mean). In Figure 1, values from EAE mice are graphed as the percentage of mean normal values; in Figures 2 and 4, actual cytokine levels are presented (means ± standard error of the mean). Human blood samples presented in Figure 3 were assayed individually and graphed as individual data points. Multiplex and ELISA data were analyzed using ANOVA with Newman–Kuels posttests. All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software Version 5.0 (La Jolla, CA, USA). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Table 1.

Cytokine expression levels in mice with EAE.

| Chemokine/cytokine | Normal | EAE + saline 10 days | EAE + saline 20 days |

|---|---|---|---|

| pg/ml | pg/ml | pg/ml | |

| IL-1β | 1.4 ± 0.13 | 4.4 ± 0.16 | 3.9 ± 0.46 |

| IL-2 | 0.9 ± 0.05 | 2.1 ± 0.35 | 2.5 ± 0.43 |

| IL-4 | 0.4 ± 0.09 | 0.6 ± 0.09 | 0.17 ± 0.07 |

| IL-5 | 8.7 ± 0.55 | 24.1 ± 1.73 | 7.2 ± 2.18 |

| IL-6 | 11.25 ± 1.5 | 529 ± 31.1 | 111.3 ± 26.95 |

| IL-10 | 20.0 ± 2.24 | 44.2 ± 1.4 | 30.0 ± 4.4 |

| Il-12p70 | na | 35.0 ± 0.0 | na |

| CXCL-1/KC-GRO | 106.0 ± 12.37 | 96.3 ±6.38 | 78.45 ± 18.12 |

| IFN-γ | 1.04 ± 0.22 | 54.96 ± 4.1 | 5.7 ± 0.35 |

| TNF-α | 6.94 ± 0.42 | 59.01 ±2.74 | 24.1 ± 1.23 |

Note: Values represent means ± SEM for measurements from two to six wells of pooled serum (n > 3 mice per group) from mice with established EAE for either 10 or 20 days.

EAE: experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; Na: insufficient data.

See figures 1-3 for statistical differences between Normal and Saline-treated mice with EAE, as well as changes following therapy with OGF or LDN.

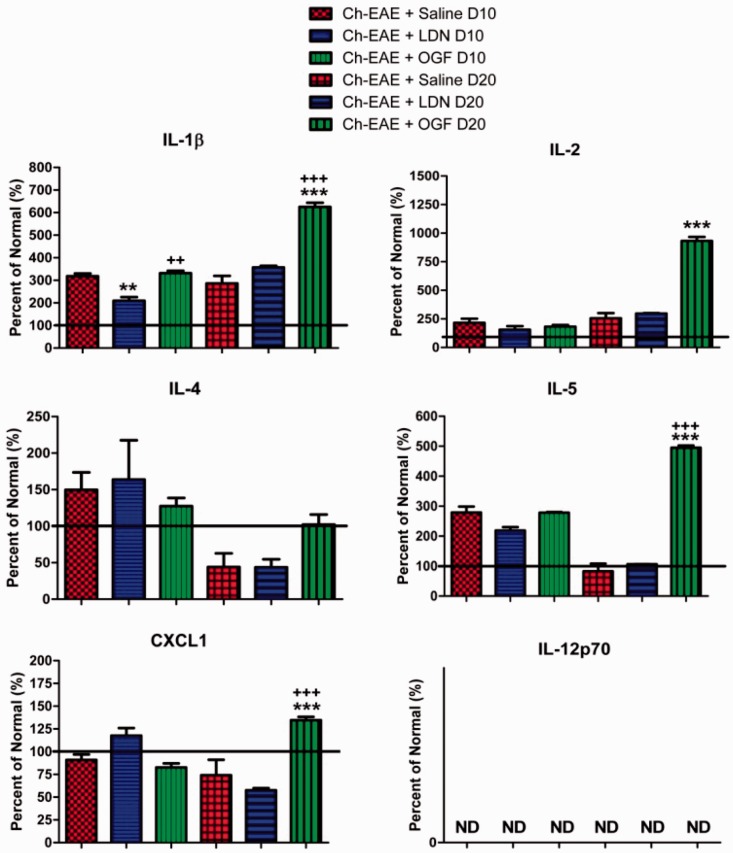

Figure 1.

Multiplex cytokine assay of serum from mice immunized with MOG35–55 and treated with saline, LDN, or OGF for either 10 or 20 days beginning at the time of immunization. Values represent the mean percent of normal mice (± SEM). Whole body blood was pooled for three mice in each group at each time point and assayed in duplicate. Values were analyzed by ANOVA; significantly different from saline treatment of the corresponding age at P < 0.01 (**), P < 0.001 (***) and from the LDN treated mice at the corresponding age at P < 0.01 (++) or P < 0.001 (+++). (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

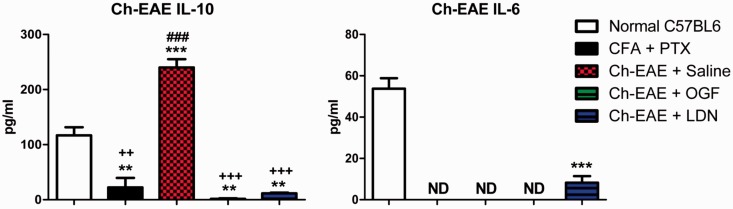

Figure 2.

Multiplex cytokine assay of four cytokines that were substantially altered in serum from mice immunized with MOG35–55 and treated with saline, LDN, or OGF. Values represent the mean (± SEM) serum levels (pg/ml) for normal mice, and mice immunized with Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) only, or immunized with MOG35–55 and CFA and treated with saline, LDN, or OGF for 10 or 20 days beginning at the time of immunization. Whole body blood was pooled for three mice in each group at each time point and assayed in duplicate. Values were analyzed by ANOVA. Significantly different from normal mice at P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**), P < 0.001 (***); significantly different from saline-treated EAE mice at P < 0.05 (+), P < 0.01 (++) or P < 0.001 (+++); and significantly different from LDN-treated EAE mice at P < 0.05 (#), P < 0.01 (##), and P < 0.001 (###). (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

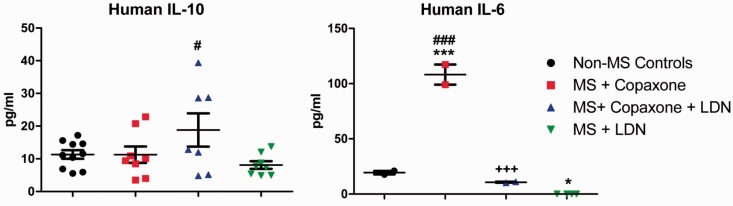

Figure 4.

Cytokine validation using ELISA kits of IL-6 and Il-10 in human serum. Serum samples from volunteer MS patients were obtained through the Institute of Personalized Medicine. MS patients were prescribed Copaxone®, Copaxone® + LDN, or LDN only; non-MS neurology patients were considered controls. Serum was assayed in duplicate and individual data points are expressed on the scattergrams. Significantly different from normal samples at P < 0.05 (*) or P < 0.001 (***); significantly different from expression levels in MS + Copaxone® patients at P < 0.001 (+++); and significantly different from MS + LDN at P < 0.05 (#) or P < 0.001 (###). (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

Figure 3.

Cytokine validation using ELISA kits of IL-6 and IL-10 expression in serum from mice immunized with MOG35–55 and treated with saline, LDN, or OGF. Values represent the mean (± SEM) serum levels (pg/ml) for normal mice, mice immunized with Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) only, or immunized with MOG35–55 and CFA and treated with saline, LDN, or OGF for six days beginning at the time of immunization. Whole body blood was pooled for three mice in each group at each time point and assayed in duplicate. Values were analyzed by ANOVA. Significantly different from normal mice at P < 0.01 (**) or P < 0.001 (***); significantly different from saline-treated EAE mice at P < 0.01 (++) or P < 0.001 (+++); and significantly different from LDN-treated EAE mice at P < 0.001 (###). (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal.)

Results

Multiplex cytokine arrays

Sixty-six C57Bl/6 mice were used in both the multiplex and validation studies, of which 48 were immunized with MOG35–55. No mouse died from EAE disease. For the multiplex cytokine assay, EAE mice were euthanized at 10 and 20 days of treatment and blood collected. Blood from five mice inoculated with only pertussis and CFA (CFA + PTX group) also was collected on day 10. Of the 10 cytokines evaluated, nine were elevated in mice immunized with MOG35–55 relative to normal, non-immunized mice; cytokine IL-12p70 was below detectable levels for all groups; 7 of 10 cytokines were elevated in mice with EAE receiving saline for 10 days, whereas after 20 days of disease, only 5 cytokines in the Ch-EAE + Saline mice were elevated over normal levels (Table 1). In mice from the CFA + PTX group, serum levels of IL-1β, IL-2, IL-5, and CXCL-1 were elevated from those recorded in normal mice. At 10 days following immunization and treatment, no changes in the expression levels of IL-2, IL4, IL-5, and CXCL-1 were noted between mice in the Normal group or those immunized with MOG35–55 (Table 1, Figure 1). At 20 days of OGF treatment, serum levels of IL-1β, IL-2, IL-5, and CXCL-1 were significantly elevated relative to those recorded in Ch-EAE + Saline mice. IL-1β, IL-5, and CXCL-1 were also significantly elevated in Ch-EAE + OGF-treated mice relative to EAE + LDN animals (Figure 1). Comparison of cytokine expression at the two time points indicated that cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-α had greater expression on day 10 of disease relative to day 20 (Table 1).

With regard to cytokines that were modulated after 10 days of OGF or LDN treatment (Figure 2), expression levels of IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and IFN-γ were elevated relative to Normal values in all EAE mice regardless of treatment, except for IFN-γ values in LDN treated mice. IL-6 cytokine expression was elevated in EAE mice more than 45-fold (529 pg/ml for Ch-EAE + Saline) relative to that in control, non-immunized mice (11 pg/ml). Treatment with LDN or OGF for 10 days increased IL-6 cytokine levels an additional 30% and 62%, respectively. IL-10 cytokine values in the EAE mice were significantly elevated up to 120% (Ch-EAE + Saline) from normal values at day 10. However, OGF and LDN treatment reduced IL-10 cytokine expression relative to the Ch-EAE + Saline mice (Figure 2). With regard to TNF-α expression, all mice immunized with MOG35–55 had cytokine levels that were more than 4.7-fold greater than those for normal mice (7 pg/ml). LDN and OGF treatment for 10 days reduced TNF-α expression by approximately 40% relative to Ch-EAE + Saline values (Figure 2). IFN-γ expression was significantly increased in Ch-EAE mice receiving saline after 10 days; however, OGF or LDN treatment significantly reduced IFN-γ levels relative to values recorded for Ch-EAE + Saline mice.

At approximately 20 days post immunization, a time equivalent to peak EAE clinical disease, mice in each group were euthanized and serum collected for assay by the Multiplex kit. Behavioral scores for these mice on day 20 indicated that all Ch-EAE mice had some behavioral expression of disease. Profiles for most cytokines at 20 days were different from the patterns reported at 10 days (Figures 1 and 2). EAE mice had substantially elevated levels of IL-6 after 20 days of disease, and OGF- and LDN-treatments increased levels 6-fold and 2-fold more than those recorded in serum from Ch-EAE + Saline mice (Figure 2). IL-10 levels at 20 days were elevated above normal levels and comparable among all Ch-EAE mice (saline, OGF, or LDN treated). TNF-α values were elevated among all three groups of EAE mice, but were less than those recorded on day 10 (Figure 2). IFN-γ expression ranged from approximately 6 pg/ml for mice receiving saline-treatment to 9 pg/ml for mice receiving LDN-treatment and 23 pg/ml for mice receiving OGF; normal mice had a mean of 1 pg/ml IFN-γ (Figure 2).

Cytokine validation: Humans and Ch-EAE mice

MS patient demographics

Serum from 14 MS patients and 8 non-MS control subjects was used in the validation assays. Six MS patients were prescribed only Copaxone®; this cohort consisted of five females, four of whom had relapsing-remitting MS (RR-MS). The control population consisted of seven females and one male; these volunteers presented to the clinic with migraines or non-autoimmune-related disorders. The range of ages for all subjects in the study was 36–89 years for females and 37–73 years for males. Five MS patients received Copaxone® and LDN; this cohort consisted of two females with RR-MS and three males, one who was diagnosed with primary progressive MS and two with RR-MS. The cohort of patients on LDN alone was small and consisted of two males and one female, all with RR-MS. At the time of blood collection for the 7 patients in the MS + Copaxone group, the length of MS diagnosis was approximately 14 years with 6 years of treatment. Patients in the Copaxone + LDN treatment group had MS for approximately 13 years and were treated with Copaxone for 5.5 years and LDN for 5.4 years. MS patients receiving only LDN had MS for 10 years and were being treated with LDN only for 5.5 years; no information was provided on previous treatments.

ELISA cytokine validation

IL-6 and Il-10 cytokines were validated using ELISA kits with specificity for either mouse or human. IL-6 and IL-10 were selected for validation to represent pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory markers, respectively, in mice with Ch-EAE (Figure 3) and MS subjects (Figure 4). MOG35–55-injected mice were euthanized after six days of treatment and thus had received only one MOG immunization and had no clinical behavioral signs of EAE. IL-6 cytokine levels were not detectable in mice in the CFA + PTX, Ch-EAE + Saline, or Ch-EAE + OGF groups, and were markedly reduced from normal mice (54 pg/ml) in mice immunized with MOG and treated with LDN (8 pg/ml) (Figure 3). Validation of IL-10 cytokine levels in mice six days after immunization revealed a 2-fold elevation in mice immunized with MOG35–55 and receiving saline relative to normal mice (110 pg/ml), and more than 4-fold greater than CFA + PTX mice. IL-10 values in immunized mice receiving OGF or LDN were significantly reduced from Normal levels, as well as those in the Ch-EAE + Saline groups, with values in these treated groups ranging from 1 to 10 pg/ml (Figure 3).

Analysis of human blood samples revealed that mean levels of serum IL-10 values for non-MS controls and all MS patients on LDN alone and/or Copaxone® alone were comparable, due in part to sample variability. Subjects receiving both LDN and Copaxone® had a broad range of values that resulted in mean IL-10 cytokine levels that were significantly different from MS subjects receiving LDN only. IL-6 cytokines were significantly elevated in MS patients receiving only Copaxone® treatment in comparison to values from patients receiving LDN alone or LDN in combination with Copaxone® (Figure 4).

Discussion

The use of multiplex technologies to profile cytokines before and after therapy is an effective means of determining efficacy and changes in relative disease states. Validation of the multi-analyte profile with specific ELISA immunoassays of patient and animal serum samples added confirmation of changes in select cytokines related to modulation of the OGF-OGFr pathway. The results of our ELISA assays corresponded to those indicated by the multiplex technology, and support evidence published on correlation between multiplex cytokine kits and ELISA measurements.31 This multiplex assay included pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines related to early stage inflammatory response. IL-1β, IL-4, and IL-5 are pro-inflammatory cytokines that were elevated within 10 days of MOG35–55 immunization, but not consistently responsive within that time frame to OGF or LDN. These cytokines stimulate B-cell proliferation, Th-2 differentiation, and eosinophil maturation by prolonging survival and delaying apoptosis. IL-2 was significantly increased only in Ch-EAE + OGF mice after 20 days and is related to cell-mediated immunity and auto-infections. This interleukin discriminates between foreign antigens and auto-immunity, and acts by promoting regulatory T cells, effector T cells, and memory T cells. Another cytokine that was activated only by OGF after 20 days of treatment was CXCL-1 or KC/GRO. CXCL-1 neutrophils and may be neuroprotective. Thus, OGF treatment for 20 days stimulated expression of 4 cytokines (IL-1β, IL-2, IL5, and CXCL-1) that are presumably involved in B cell production, Th-2 differentiation, and transitions from Th1 to Th2, a mechanistic pathway suggested to be neuroprotective. IL-12p70, a pro-inflammatory marker, was undetectable in most samples. This cytokine family is produced by dendritic cells, macrophages and monocytes, and induces differentiation of CD4+ T cells to Th1 cells.

The four cytokines that were altered following OGF or LDN treatment of mice with EAE were TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6, and IL-10, and represented both pro-inflammatory (e.g. IFN-γ) and anti-inflammatory markers (e.g. IL-10). The IL-6 cytokine has both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory properties with the latter often labeled as myokines.32 In our study, IL-6 levels were significantly elevated in all groups of mice receiving MOG35–55 immunization. Moreover, both OGF and LDN treatment increased IL-6 levels after 10 and 20 days of treatment, as well as after 6 days of treatment with OGF. These data suggest that IL-6, a pro-inflammatory marker is very responsive to OGF and LDN therapy, and thus may be involved in other mechanistic pathways associated with the OGF-OGFr axis. While the specific pathways targeted in EAE or MS need to be clarified, IL-6 is known to stimulate the production of B cells, antagonize production of regulatory T-cells and ultimately suppress inflammation.33 Thus, despite being pro-inflammatory, the accentuated response of IL-6 following OGF and LDN therapy may suggest the stimulation of a neuroprotective pathway. Interestingly, levels of IL-6 were undetectable within only six days of disease in most Ch-EAE mice. Whether the inability to measure IL-6 in mice receiving LDN is biologically relevant or related to sampling error is unknown, but validates pursuit of IL-6 as another marker related to modulation of the OGF-OGFr axis.

IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine that downregulates Th1 expression was elevated in all EAE mice, regardless of treatment, at 10 and 20 days.30,34 OGF and LDN treatment appeared to downregulate IL-10 expression at 10 days, but had little effect following 20 days of treatment. The downregulation was also recorded in EAE mice receiving LDN or OGF at six days of age in comparison to the both normal levels and those stimulated by EAE in the Ch-EAE + Saline mice. The interactions between the OGF-OGFr pathway and the mechanistic activity of this cytokine warrant further investigation.

In the case of IFN-γ and TNF-α, OGF and LDN reduced the expression of both cytokines implying that OGF and LDN treatment may reduce macrophage activation at least early (i.e. 10 days) in the EAE process relative to saline-treated EAE mice. IFN-γ promotes a biofeedback loop between Th1 cell production and IFN-γ secretion leading to increased natural killer cell activity and activated nitric oxide synthase.35,36 The relationship between Th1 and Th2 differentiation is well known as a pathway relevant to MS progression. This pathway now appears to be modified by modulation of the OGF-OGFr axis. Both IFN-γ and TNF-α are cytokines related to the acute phases of systemic inflammation, and the onset of autoimmune diseases such as IBD, fibromyalgia, and MS.35–37

These multiplex data represent very short-term periods of modulation by OGF or LDN, but are also data from one (6 days), two (10 days) and three weeks (20 days) post-immunization. Collectively, treatment with OGF or LDN appeared to have an impact on some cytokines within one or two weeks of exposure. Twenty days post immunization may represent a period late in the autoimmune process that cannot be further manipulated by OGF or LDN treatment.

Assays on human serum revealed that IL-10 cytokine levels were unchanged in humans with MS, regardless of treatment, in comparison to normals. IL-6 cytokine values were elevated in MS patients on Copaxone®, but reduced in MS patients on LDN. Endogenous stimulation of OGF by the LDN therapy resulting in reduction of IL-6 cytokines warrants additional research given our knowledge that OGF levels are reduced, possibly leading to IL-6 expression, in MS humans and animals with EAE.18,19 However, the study is far from being conclusive as the sample size is extremely low and blood samples were stored for various periods of time. Moreover, the variation in length of disease and length of treatment, as well as the lack of substantial patients in any one cohort was a contributing factor to the variable outcomes, but will always be a concern. Nonetheless, the preliminary data suggest that LDN, and by default the OGF, may be effective at providing some form of therapeutic modulation of cytokines.

The changes in cytokine expression levels recorded in animal EAE models are not unexpected as earlier reports on gene expression of relevant cytokines in both human and animal models of EAE are shown changes in pro-inflammatory genes such as IL-6, IL-17A, and IFN-γ as disease progresses.37–41 Several studies looking at dietary treatments reported that decreased IL-6 was related to improved disease following increased intake of vitamin D; unfortunately, there was no correlation with improved EDSS (Expanded Disability Status Scale).40 In a relapsing-remitting model of EAE, it was reported that resveratrol increased IL-10 and IL-17 producing T cells migrating to the CNS, and suppressed IL-6 pro-inflammatory macrophage expression.28 In a review on several autoimmune disorders including MS, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus, Ireland noted that IL-6 and IL-10 play roles in nearly all inflammatory disorders, discussing the fact that MS patients secrete higher levels of IL-6, and lower levels of IL-10 than normal subjects, presumably reflecting B cell activity.29 In this report, Copaxone® therapy attenuated B cell responses, modifying B cell cytokine production and leading to reduced T cell inflammatory responses. Arellano et al.26 report that IFN-γ may be protective in EAE by modulating effector T cell responses, as well as being pro-inflammatory; the positive effects of IFN-γ are stage-specific.

In summary, these experiments correlate well with literature on fluctuations in cytokines in patients with MS, and also support the measurement of these cytokines by multiplex assays and ELISAs. Whether IL-6 and IL-10 are appropriate markers to monitor progression of MS still needs to be studied with long-term human and mouse studies. Nonetheless, these experiments demonstrated that at least four cytokines – IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and IFN-γ, may be useful markers to monitor EAE and MS. In concert with our data that OGF levels are specific indicators of disease progression and response to therapy in mice with EAE18 and humans with MS,19 a panel of biomarkers is beginning to emerge that will be helpful for the diagnosis of disease, and management of MS.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Syndi Reed, Patient Recruitment Specialist, Institute for Personalized Medicine, for facilitating their access to the human serum samples.

Authors’ contributions

All authors participated in the design of the study, interpretation of data and/or review of the manuscript. MDL conducted the experiments as part of his doctoral studies, analyzed data, prepared the figures, and participated in preparation of the draft manuscript. MDL is currently an Assistant Professor of Anatomy at Franciscian Missionaries of Our Lady University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana. ISZ participated in the editing of draft and final manuscripts, interpretation of data, and assisted in the supervision of MDL. PJM supervised MDL with experimental design and data analyses, and participated in final data interpretation, and preparation of the draft and final manuscripts.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from The Paul K. and Anna M. Shockey Family Foundation (ISZ, PJM), and the LDN Surgery Fund (ISZ, PJM).

References

- 1.Owens GM. Economic burden of multiple sclerosis and the role of managed care organizations in multiple sclerosis management. Am J Manag Care 2016; 22:S151–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.www.nationalmssociety.org/about-multiple-sclerosis/index.aspx (accessed 23 October 2017)

- 3.Pietrangelo A, Higuera V. Multiple sclerosis by the numbers: facts, statistics, and you, www.healthline.com/health/multiple-sclerosis/facts-statistics-infographic (accessed 23 October 2017)

- 4.Browne P, Chandraratna D, Angood C, Tremlett H, Baker C, Taylor BV, Thompson AJ. Atlas of multiple sclerosis 2013: a growing global problem with widespread inequity. Neurology 2014; 83:1022–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharafaddinzadeh N, Moghtaderi A, Kashipazha D, Majdinasab N, Shalbafan B. The effect of low-dose naltrexone on quality of life of patients with multiple sclerosis: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Mult Scler 2010; 16:964–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raknes G, Smabrekke L. A sudden and unprecedented increase in low dose naltrexone (LDN) prescribing in Norway. Patient and prescriber characteristics, and dispense patterns. A drug utilization cohort study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2017; 26:136–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gironi M, Martinello-Boneschi F, Sacerdote P, Solaro C, Zaffaroni M, Cavarretta R, Moiola L, Bucello S, Radaelli M, Pilato V, Rodegher M, Cursi M, Franchi S, Martinelli V, Memni R, Comi G, Martino G. A pilot trial of low-dose naltrexone in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2008; 14:1076–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parkitny L, Younger J. Reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines after eight weeks of low-dose naltrexone for fibromyalgia. Biomedicines 2017; 5:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.https://www.ldnscience.org/lp/clinical-trials-jan-2017?gclid=CLuG8aqWldQCFV5YDQodZSwDnQ; https://druginfo.nlm.nih.gov/drugportal/name/Naltrexone (accessed 24 October 2017)

- 10.Turel AP, Oh KH, Zagon IS, McLaughlin PJ. Low dose naltrexone (LDN) for treatment of multiple sclerosis: a retrospective chart review of safety and tolerability. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2015; 35:609–11 PMID: PMID:26203498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ludwig MD, Turel AP, Zagon IS, McLaughlin PJ. Long-term treatment with low dose naltrexone maintains stable health in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J 2016; 2:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLaughlin PJ, Zagon IS. Duration of opioid receptor blockade determines clinical response. Biochem Pharmacol 2015; 97:236–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zagon IS, Rahn KA, Turel AP, McLaughlin PJ. Endogenous opioids regulate expression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: a new paradigm for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Exp Biol Med 2009; 234:1383–92 PMID: 19855075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahn KA, McLaughlin PJ, Zagon IS. Prevention and diminished expression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by low dose naltrexone (LDN) or opioid growth factor (OGF) for an extended period: therapeutic implications for multiple sclerosis. Brain Res 2011; 1381:243–53 PMID: 21256121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell AM, Zagon IS, McLaughlin PJ. Opioid growth factor arrests the progression of clinical disease and spinal cord pathology in established experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Brain Res 2012; 1472:138–48 PMID 22820301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammer LA, Zagon IS, McLaughlin PJ. Improved clinical behavior of established relapsing-remitting experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis following treatment with endogenous opioids: implications for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Brain Res Bull 2015; 112:42–51 PMID: 25647234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammer LA, Zagon IS, McLaughlin PJ. Low dose naltrexone treatment of established relapsing-remitting experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Mult Scler 2015; 2:1000136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ludwig MD, Zagon IS, McLaughlin PJ. Elevated serum enkephalins correlated with improved clinical outcomes in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Brain Res Bull 2017; 134:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludwig MD, Zagon IS, McLaughlin PJ. Serum [Met5]-enkephalin levels are reduced in multiple sclerosis and restored by low dose naltrexone. Exp Biol Med 2017; 242:1524–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jankovic BD. Enkephalins and immune inflammatory reactions. Acta Neurol 1991; 13:433–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Immonen JA, Zagon IS, McLaughlin PJ. Selective blockade of the OGF-OGFr pathway by naltrexone accelerates fibroblast proliferation and wound healing. Exp Biol Med 2014; 239:1300–9 PMID:25050485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zagon IS, Donahue RN, Bonneau RH, McLaughlin PJ. T lymphocyte proliferation is suppressed by the opioid growth factor ([Met5]-enkephalin)-opioid growth factor receptor axis: implication for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Immunobiology 2011; 216:579–90 PMID: 2096560635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zagon IS, Donahue RN, Bonneau RH, McLaughlin PJB. lymphocyte proliferation is suppressed by the opioid growth factor-opioid growth factor receptor axis: implication of the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Immunobiology 2011; 216:173–83 PMID: 20598772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLaughlin PJ, McHugh DP, Magister MJ, Zagon IS. Endogenous opioid inhibition of proliferation of T and B cell subpopulations in response to immunization for experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. BMC Immunol 2015; 16:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammer LA, Waldner H, Zagon IS, McLaughlin PJ. Opioid growth factor and low dose naltrexone impair CNS infiltration by CD4+ T lymphocytes in established experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Exp Biol Med 2016; 241:71–8 PMID: 26202376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arellano G, Ottum PA, Reyes LI, Burgos PI, Naves R. Stage-specific role of interferon-gamma in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol 2015; 6:492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cauvi DM, Cauvi G, Toomey CB, Jacquinet E, Pollard KM. Interplay between IFN-γ and IL-6 impacts the inflammatory response and expression of interferon-regulated genes in environmental-induced autoimmunity. Toxicol Sci 2017; 158:227–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imler TJ, Jr, Petro TM. Decreased severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis during resveratrol administration is associated with increased IL-17+IL-10+ T cells, CD4-IFN-γ+ cells, and decreased macrophage IL-6 expression. Int Immunopharmacol 2009; 9:134–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ireland SJ, Monson NL, Davis LS. Seeking balance: potentiation and inhibition of multiple sclerosis autoimmune responses by IL-6 and IL-10. Cytokine 2015; 73:236–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iyer SS, Cheng G. Role of interleukin 10 transcriptional regulation in inflammation and autoimmune disease. Crit Rev Immunol 2012; 32:23–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richens JL, Urbanowic RA, Metcalf R, Come J, O’shea P, Fairclough L. Quantitative validation and comparison of multiplex cytokine kits. J Biomol Screen 2010; 15:562–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferguson-Smith AC, Chen YF, Newman MS, May LT, Sehgal PB, Ruddle RH. Regional localization of the interferon-beta 2/B-cell stimulatory factor 2/hepatocyte stimulating factor gene to human chromosome 7p15-p21. Genomics 1988; 2:203–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunter CA, Jones SA. IL-6 as a keystone cytokine in health and disease. Nat Immunol 2015; 16:448–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozenci V, Kouwenhoven M, Huang YM, Xiao B, Kivisökk P, Fredrikson S, Link YH. Multiple sclerosis: levels of interleukin-10-secreting blood mononuclear cells are low in untreated patients but augmented during interferon-beta-1b treatment. Scand J Immunol 1999; 49:554–61 PMID: 10320650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Artis D, Sits H. The biology of innate lymphoid cells. Nature 2015; 517:293–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schoenborn JR, Wilson CB. Regulation of interferon-gamma during innate and adaptive immune responses. Adv Immunol 2007; 96:41–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brennan FM, Green P, Amjadi P, Robertshaw HJ, Alvarez-Iglesias M, Takata M. Interleukin-10 regulates TNF-alpha-converting enzyme (TACE/ADAM-17) involving a TIMP-3 dependent and independent mechanism. Eur J Immunol 2008; 38:1106–17 PMID: 18383040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lock C, Hermans G, Pedotti RA, Brendolan A, Schadt E, Garren H, Langer-Gould A, Strober S, Cannella B, Allard J, Klonowski P, Austin A, Lad N, Kaminski N, Galli SJ, Oksenberg JR, Raine CD, Heller R, Steinman L. Gene-microarray analysis of multiple sclerosis lesions yields new targets validated in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nat Med 2002; 8:500–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hedreul MT, Gillett A, Olsson T, Jogodic M, Harris RA. Characterization of multiple sclerosis candidate gene expression kinetics in rat experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol 2009; 210:30–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gargari BN, Behmanesth M, Farsani ZH, Kakhki MP, Azimi AR. Vitamin D supplementation up-regulates IL-6 and Il-17A gene expression in multiple sclerosis patients. Int Immunopharmacol 2015; 28:414–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kvarnström M, Ydrefors J, Ekerfelt C, Vrethem M, Ernerudh J. Longitudinal interferon-β effects in multiple sclerosis: differential regulation of IL-10 and IL-17A, while no sustained effects on IFN-γ, IL-4 or IL-13. J Neurol Sci 2013; 325:79–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]