Abstract

Introduction:

Patient experience with emergency department (ED) care is an expanding area of focus, and recent literature has demonstrated strong correlation between patient experience and meeting several ED and hospital goals. The objective of this study was to perform a systematic review of existing literature to identify specific factors most commonly identified as influencing ED patient experience.

Methods:

A literature search was performed, and articles were included if published in peer-reviewed journals, primarily focused on ED patient experience, employed observational or interventional methodology, and were available in English. After a structured screening process, 107 publications were included for data extraction.

Result:

Of the 107 included publications, 51 were published before 2011, 57% were conducted by American investigators, and 12% were published in nursing journals. The most commonly identified themes included staff-patient communication, ED wait times, and staff empathy and compassion.

Conclusion:

The most commonly identified drivers of ED patient experience include communication, wait times, and staff empathy; however, existing literature is limited. Additional investigation is necessary to further characterize ED patient experience themes and identify interventions that effectively improve these domains.

Keywords: communication, emergency medicine, empathy, patient-/relationship-centered skills, patient expectations, patient satisfaction, quality improvement, wait times

Introduction

Patient experience with emergency department (ED) care is a rapidly expanding area of research and focus for health-care leaders, and recent literature has demonstrated a strong correlation between high overall patient experience and improved patient outcomes, profitability, and other health-care system goals (1 –3). An ED visit often represents the patient’s initial experience with a hospital system and thus a unique opportunity to establish a positive first impression. However, these visits frequently occur during times of stress and uncertainty for the patient and in an ED care environment that faces a myriad of challenges. Overcrowding, inadequate communication, a lack of patient privacy, poor pain control, and uncomfortable ED environments all continue to be issues that impact patients’ experiences of care and as a result remain areas of focus for ED leaders (4 –9).

These deficiencies not only lead to unsatisfactory experiences for ED patients but have important downstream effects as well. In 2005, Stelfox et al found that the frequency of both patient complaints and lawsuits was related to factors that strongly influence the patient experience; time spent with patients by physicians, the perception of concern about patients’ questions, and physician courtesy were all strongly associated (10). Prior work has also demonstrated that patients’ ratings of their health care correlate more strongly with experience factors rather than with technical quality of care (11). In addition, positive patient experience has also been shown to improve both medication compliance and objective clinical outcomes (1,12).

Beyond patient outcomes and malpractice risk, there also exist growing financial implications of poor patient experience in the ED. The development and deployment by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) Survey in 2006 has led to an increased emphasis on patient experience within inpatient medicine. Among the 27 items composing the survey are physician and nursing communication and responsiveness, adequacy of pain management, and hospital environmental factors such as cleanliness and quietness (13). With the anticipated release of the Emergency Department Patient Experiences with Care (EDPEC) Survey, CMS’s HCAHPS in the ED, many of the same factors will be measured for ED patients (14). Starting in 2017, HCAHPS total performance scores will be tied to a 2% incentive or penalty for Medicare reimbursement. Assuming similar incentives and penalties following the deployment of EDPEC, US EDs may be obliged to depend on competitive EDPEC scores to maintain adequate reimbursement and financial stability.

Finally, although the drivers of patient experience were studied extensively in the first decade of the 2000s, the relative value and importance of these themes was not established (4,7). Since that time, the regulatory environment and systems of ED care have also evolved, leading to potentially new areas of focus and themes related to ED patient experience. The objective of this study was to perform a systematic review of the extant literature to further define the current relative importance of factors contributing to patient experience in the ED and create a framework to direct future study of ED patient experience interventions.

Methods

Criteria for Review

Peer-reviewed articles that met all the following criteria were eligible for inclusion in this review: (1) predominantly focused on the patient experience or satisfaction; (2) ED primary study setting; (3) observational or interventional methodology, excluding articles reviewing prior literature; (4) full text available in English; and (5) published in peer-reviewed journal.

Literature Search and Article Selection

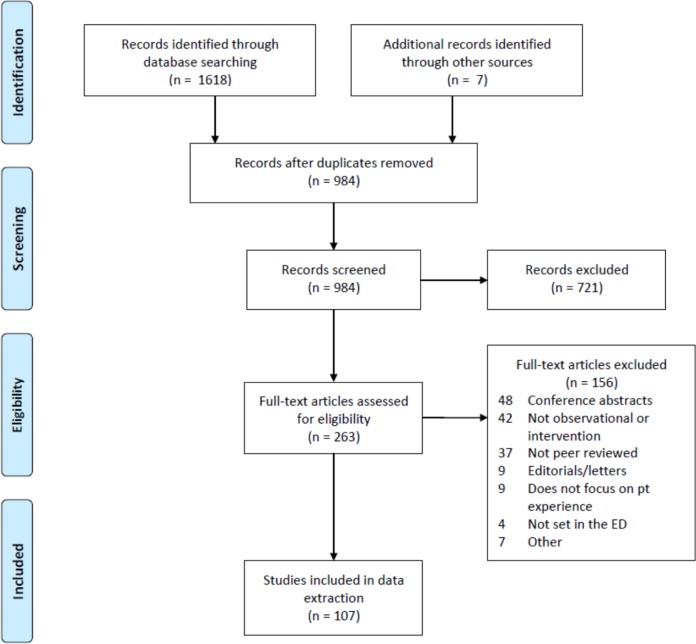

A literature search was performed by a medical librarian in the MEDLINE (Ovid), PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Embase, and Web of Science databases in June 2015. Search terms included free-text synonyms and controlled vocabulary for “emergency department,” “patient experience,” and “patient centered care.” A search filter was used to limit to English-language studies. No publication date or study type limits were used. After removal of duplicate citations using bibliographic software, interrater reliability was confirmed using a random sample of 66 citations. Titles and abstracts of the citations were reviewed for meeting inclusion criteria. In the next phase, the full texts of the remaining citations were subsequently assessed for eligibility, and the remaining publications were included for data extraction by 4 authors (J.D.S., E.A., R.L., and B.W.). All citations were independently reviewed by 2 screeners, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Citation chaining was used to identify additional articles for inclusion that were not discovered through the initial database searches. The full search and elimination process is detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart of identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of articles in review.

Data Extraction

Full-text PDFs of the remaining publications were uploaded to Dedoose version 7.1.3, a web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed-method research data (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC, Los Angeles, California). Each publication was then reviewed individually, and descriptor data including year of publication, publication location (US or other), journal type as identified by Medical Subject Headings term, and study design (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods) were recorded.

Thematic analysis was utilized to extract relevant content from each manuscript. Modified grounded theory was used to develop a set of codes related to ED patient experience. A set of 15 codes was developed and modified in an iterative fashion to allow for thematic saturation (Table 1). Using these codes, the full text of each citation was reviewed and tagged as appropriate. Finally, aggregate data were analyzed using thematic synthesis to identify the most common themes in the reviewed literature, and descriptive statistics were calculated for both coded data and descriptor data for the manuscripts.

Table 1.

Code Titles and Descriptions Used in Manuscript Review.

| Code Title | Description |

|---|---|

| ED Crowding | Related to the impact of, and programs to mitigate, high ED volume |

| ED Wait Times | Related to decreasing wait time, throughput, and the perception of wait time |

| ED Environment of Care | Related to amenities in the department, inclusive of privacy, blankets, pillows, food |

| ED Leadership & Policy Factors | Related to organizational structure impacts on patient experience |

| Patient Expectations | Related to patient’s inherent expectations or expectations set by ED |

| Patient Demographic Factors | Related to patient age, language, SES, and family support system |

| Patient Pain & Pain Control | Related to patients’ pain and pain management, inclusive of communication and expectations |

| Staff Medical Competence | Related to perceptions of staff skill, training, and competency |

| Staff Empathy & Compassion | Related to compassionate care and empathy (patient perception and staff training) |

| Staff Professionalism/CS | Related to disruptive behavior, respect, and dignity |

| Staff-Patient Communication | Related to communication between staff and patients—perception and skills training |

| Staff-Staff Communication | Related to communication between staff—perception and skills training—including handoffs |

| Patient Support | Related to patient advocacy, navigator programs, and care coordination |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; SES, socioeconomic status.

Results

Study Inclusion

The search yielded a total of 1625 citations; 641 duplicate citations were removed using bibliographic software, leaving a total of 984 citations for screening. The titles and abstracts of the 984 citations were reviewed for relevance, and 721 citations were excluded. The full texts of the remaining 263 citations were assessed for eligibility and 156 citations were excluded, leaving 107 publications included for data extraction by 4 authors (J.D.S., E.A., R.L., and B.W.). The most common reasons for exclusion of full-text articles included conference abstracts (48), not being an observational or interventional study (including prior review articles) (42), and not from a peer-reviewed journal (37).

Interrater reliability during the screening phase was high (κ = 0.87). Of the remaining 107 publications, 27 were published prior to 2004, 50 were published prior to 2010, and 51 were published between 2011 and 2016. Regarding publication location, 61 were published by American investigators, and 46 were published internationally. The most common types of journals included in the review were emergency medicine (50.5%), emergency nursing (12.1%), medicine (6.5%), quality of health care (5.6%), nursing care (4.7%), health services (4.7%), and pediatrics (2.8%). Regarding study design, 55 (51.4%) of the reviewed studies used quantitative methods, 21 (19.6%) used qualitative methods, and 30 (28.0%) used mixed methods. Table 2 summarizes the study design breakdown and descriptor results for the reviewed manuscripts.

Table 2.

Study Designs and Journal Types for Included Manuscripts.

| Study Design | Count | Journal Type (MeSH) | Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed methods | 30 | Emergency medicine | 54 |

| Qualitative | 21 | Emergency nursing | 13 |

| Quantitative | 55 | Pediatrics | 3 |

| Other (consensus) | 1 | Medicine | 7 |

| Pediatric emergency medicine | 0 | ||

| Cardiovascular diseases/nursing | 1 | ||

| Nursing care | 5 | ||

| Quality of health care | 6 | ||

| Behavioral medicine | 1 | ||

| Communication | 3 | ||

| Critical care | 1 | ||

| Counseling | 3 | ||

| Health services | 5 | ||

| Social medicine | 2 | ||

| Nursing, supervisory | 2 | ||

| Integrative medicine | 1 |

Frequency of Patient Experience Themes

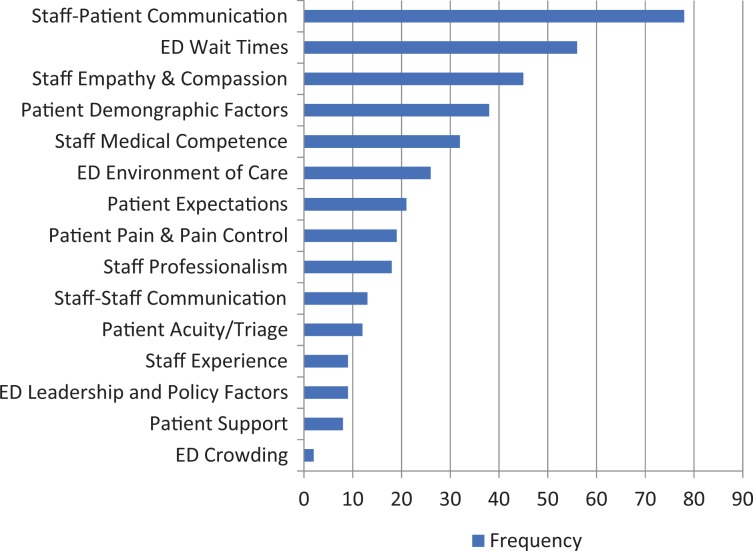

Figure 2 summarizes the most common patient experience themes by code. Staff–patient communication was cited 78 times in the reviewed studies. The next most commonly cited themes were wait times (56), staff empathy and compassion (45), patient demographic factors (38), ED environment of care (26), and patient expectations (21). The least common themes included patient acuity and triage (12), staff experience (9), ED leadership and policy factors (9), patient support (8), and ED crowding (2).

Figure 2.

Frequency of identified patient experience themes.

Discussion

This rigorous systematic review of patient experience literature in emergency medicine identified the most common themes in ED patient experience as staff–patient communication, ED wait times, staff empathy and compassion, patient demographic factors, and staff medical competence.

Several previous literature reviews have identified various factors contributing to ED patient experience. In 2004, Boudreaux and O’Hea reviewed 50 articles meeting selection criteria and found that the strongest predictor of ED patient satisfaction was the quality patient–ED provider interpersonal interaction (15). In the same year, Taylor and Benger identified a collection of service factors (eg, interpersonal skills, perceived staff attitudes, provision of information/explanation, aspects related to waiting times) with influence on patient experience (7). Also in 2004, Nairn et al summarized the extant ED patient experience literature in an international nursing journal and identified the 6 common themes: waiting times, communication, cultural aspects of care, pain, the environment, and dilemmas in accessing the patient experience (9). Finally, in a nonsystematic clinical review in 2010, Welch emphasized many of the same themes from the prior studies, with an emphasis on timeliness of care, empathy, technical competence, information dispensation, and pain management (4).

However, despite growing interest in ED patient experience, it has been several years since the last systematic review of the relevant literature, and our results suggest that at least 77 relevant articles have been published since that time. In addition, in the setting of an evolving landscape of patient preferences, ED systems of care, and regulatory environments, our understanding of ED patient experience may be changing. Given increasing consequences for hospitals and providers alike who do not provide excellent ED patient experience, review of the most current data is critical to directing future improvement efforts and research. Our systematic review identified yielded several important conclusions worthy of discussion.

First, staff–patient communication was by far the most frequent theme identified. The reasons for this are not entirely clear; however, this finding underscores the inherent value that patients place on appropriate and adequate communication. In addition, while “wait times” was not surprisingly the second most common theme, staff empathy and compassion were noted in almost half of the reviewed publications. Other factors including staff medical competence and experience were less often cited in our review. Prior evidence suggests patient-reported ratings of how well they were kept informed as well as physicians’ courtesy and concern for their worries correlated strongly with frequency of risk management episodes (10). Additionally, Chang et al showed that elderly patients’ own global ratings of their care were associated with provider communication, but not objective measures of technical quality of care (11). Given this evidence, our review suggests that ED patients who perceive that their providers are treating them with empathy and are communicating with them adequately may be less dissatisfied with other, less easily improved factors such as prolonged wait times and cramped ED spaces. For example, patients who feel that they are “treated as time wasters” or that staff does not “show interest in their life situation[s]” may be unable to appreciate the benefit of short wait times or spacious, clean departments (16,17). We therefore believe that formal staff communication and empathy training may be the highest yield intervention for ED leaders aiming to improve patient experience.

Second, our study demonstrates the importance of working across roles to improve ED patient experience. Given that the ED is a unique environment in which physicians, mid-level providers, nurses, clinical assistants, and other staff work together very closely to care for patients, it is imperative that efforts to improve ED patient experience include representation and perspective from all ED staff role groups. In our study, approximately 20% of reviewed articles came from nursing journals, reflecting the interdisciplinary approach to patient experience. Elder et al found that “there was a strong positive relationship between patient satisfaction with triage nurse caring behaviors, general satisfaction with the triage nurse, and intent to return to that ED,” supporting the important contribution of nonphysician staff to patient experience (18). Our review suggests that the responsibility of improving ED patient experience falls on both physician and nursing leadership, and future efforts may not be effective without the engagement of both groups.

Finally, despite increased public and governmental awareness of the importance of improving patient experience in the United States, only 57% of the reviewed articles were published by American investigators and less than half in the past 5 years. With the upcoming deployment of the EDPEC survey and potential financial implications of survey results for both individual providers and EDs in the United States, there will likely be more incentive for researchers to explore this topic over the next several years. We believe that it is important to drive focused US ED patient experience research efforts forward now to allow for quality improvement and better care for our patients as soon as possible.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, because 4 reviewers were included in the systematic review process, it is possible that there was discordance between reviewers during the coding process; however, our strong interrater reliability during the relevance screening phase suggests this may have had minimal impact. Additionally, we attempted to mitigate this through meeting frequently during the codebook development phase and during coding. Second, as a literature review, our study only reviewed the themes cited in prior literature. Thus, it is possible that there are themes that are of greater importance to patients which may not yet have been a focus of formal study. However, given the number of years for which this topic has been studied, the multiple methods used, and the broad scope of the extant literature, it is less likely that a significant contributing factor has been missed. Finally, our study focused only on manuscripts published in peer-reviewed journals. There may be additional unpublished or non-peer-reviewed data that are germane to this discussion, but these were not included in our conclusions.

Conclusion

Our systematic review reveals that the most commonly identified drivers of patient experience include factors related to communication, wait times, and staff empathy and compassion. However, existing literature is largely qualitative and limited in scope. Additional investigation is necessary both to further characterize important themes in the ED patient experience literature and to identify interventions that effectively improve these domains.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Diane Troderman for her support of this work.

Author Biographies

Jonathan D. Sonis, MD. is an emergency medicine administration fellow and attending physician in the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Emergency Medicine. He serves on the ED Patient Experience Committee and his academic and fellowship work has focused on ED patient experience improvement.

Emily L. Aaronson, MD is an assistant professor of Emergency Medicine at Harvard Medical School and an attending physician in the Department of Emergency Medicine at MGH. She also serves as assistant chief Quality Officer in the MGH Lawrence Center for quality and Safety. Emily’s academic work has focused on safety event analysis, patient experience and communication.

Rebecca Y. Lee, MPH, served as a clinical research coordinator in the Department of Emergency Medicine at MGH during this study. She received her MPH from Boston University School of Public Health, and has academic interests in patient experience, emergency medicine, and clinical research.

Lisa L. Philpotts is the Knowledge specialist for Research and Instruction at Treadwell Library at Massachusetts General Hospital. She specializes in performing in depth literature searches in support of systematic reviews and evidence based practice. Lisa is the co-chair of the Patient Care Services Collaborative Governance Research and Evidence Based Practice Committee.

Benjamin A. White, MD is an assistant professor of Emergency Medicine at Harvard Medical School and an attending physician at the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Emergency Medicine. He also serves as the director of Clinical Operations, and is the co-chair of the ED Patient Experience Committee. Ben’s academic work has focused on ED operations and systems improvement, with an emphasis on systems engineering, process flow, and patient experience improvements.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors received philanthropic support for ED Patient Experience research.

References

- 1. Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med. 2011;86:359–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kelley JM, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L, Kossowsky J, Riess H. The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9: e94207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Richter JP, Muhlestein DB. Patient experience and hospital profitability: is there a link? Health Care Manage Rev. 2017;42:247–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Welch SJ. Twenty years of patient satisfaction research applied to the emergency department: a qualitative review. Am J Med Qual. 2010;25:64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pines JM, Iyer S, Disbot M, Hollander JE, Shofer FS, Datner EM. The effect of emergency department crowding on patient satisfaction for admitted patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:825–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bernstein SL, Aronsky D, Duseja R, Epstein S, Handel D, Hwang U, et al. ; Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Emergency Department Crowding Task Force. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taylor C, Benger JR. Patient satisfaction in emergency medicine. Emerg Med J. 2004;21:528–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thompson DA, Yarnold PR, Williams DR, Adams SL. Effects of actual waiting time, perceived waiting time, information delivery, and expressive quality on patient satisfaction in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:657–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nairn S, Whotton E, Marshal C, Roberts M, Swann G. The patient experience in emergency departments: a review of the literature. Accid Emerg Nurs. 2004;12:159–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stelfox HT, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, Gustafson ML. The relation of patient satisfaction with complaints against physicians and malpractice lawsuits. Am J Med. 2005;118:1126–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chang JT, Hays RD, Shekelle PG, MacLean CH, Solomon DH, Reuben DB, et al. Patients’ global ratings of their health care are not associated with the technical quality of their care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:665–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tamblyn R, Abrahamowicz M, Dauphinee D, Wenghofer E, Jacques A, Klass D, et al. Influence of physicians’ management and communication ability on patients’ persistence with antihypertensive medication. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1064–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. HCAHPS Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. 2016. Retrieved from: http://www.hcahpsonline.org/. Accessed November 7, 2016.

- 14. Emergency Department Patient Experiences with Care (EDPEC) Survey. 2016. Retrieved from: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/CAHPS/ed.html. Accessed November 7, 2016.

- 15. Boudreaux ED, O’Hea EL. Patient satisfaction in the emergency department: a review of the literature and implications for practice. J Emerg Med. 2004;26:13–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Palmer CD, Jones KH, Jones PA, Polacarz SV, Evans GW. Urban legend versus rural reality: patients’ experience of attendance at accident and emergency departments in west Wales. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:165–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Muntlin A, Gunningberg L, Carlsson M. Patients’ perceptions of quality of care at an emergency department and identification of areas for quality improvement. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:1045–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Elder R, Neal C, Davis BA, Almes E, Whitledge L, Littlepage N. Patient satisfaction with triage nursing in a rural hospital emergency department. J Nurs Care Qual. 2004;19:263–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]