Abstract

Mammalian reproduction systems are largely regulated by the secretion of two gonadotropins, that is, luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). The main action of LH and FSH on the ovary is to stimulate secretion of estradiol and progesterone, which play an important role in the ovarian function and reproductive cycle control. FSH and LH secretions are strictly controlled by the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which is secreted from the hypothalamus into the pituitary vascular system. Maintaining normal secretion of LH and FSH is dependent on pulsatile secretion of GnRH. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) proteins, as the main components of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, are involved in the primary regulation of GnRH-stimulated transcription of the gonadotropins’ α subunit in the pituitary cells. However, GnRH-stimulated expression of the β subunit has not yet been reported. Furthermore, GnRH-mediated stimulation of ERK1 and ERK2 leads to several important events such as cell proliferation and differentiation. In this review, we briefly introduce the relationship between ERK signaling and gonadotropin secretion, and its importance in female infertility.

Keywords: dual-specificity phosphatases, ERK1-2 pathway, GnRH, FSHβ, infertility, LHβ

Introduction

Main functions of mammalian ovaries such as follicular evolvement, ovulation, luteinization, timely release of mature oocytes, and maintaining the implanted embryos are controlled by the pituitary gonadotropins follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) that are essential extra-ovarian factors.1 FSH and LH secretion is strictly controlled by hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) which is responsible for physiological patterns of gonadotropin hormones and reproductive cycles.2–4 FSH and LH are heterodimeric hormones consisting of α and β subunits.5 In both gonadotropins, the α subunits (αGSU) are the same, whereas β subunits are different and are responsible for distinct roles of these hormones.5 FSH and LH signaling implement several signaling pathways in ovarian granulosa cells such as mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular-signal-regu-lated kinase (MAPK/ERK)2,6,7 The MAPK pathway consists of protein kinases that are activated in a sequential order and couples extracellular signals to intracellular appropriate responses, including cell proliferation, inflammatory responses, development, differentiation, and apoptosis.8,9

Precise functions of MAPKs in the regulation of gonadotropins are not yet fully understood. Several studies have reported that activated ERK is involved in the primary regulation of GnRH-stimulated transcription of gonadotropins’ α subunit.10–12 However, other studies have reported controversial results about the regulatory effects of ERK on the β subunit.12–14 Regarding the critical role of MAPK/ERK signaling on the expression of essential genes involved in the regulation of gonadotropin hormones’ function, this study was conducted to review the recent findings on the specific role of ERK1/2 in female fertility, with a focus on regulation of pituitary gonadotropins’ secretion.

Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase intracellular signaling: an overview

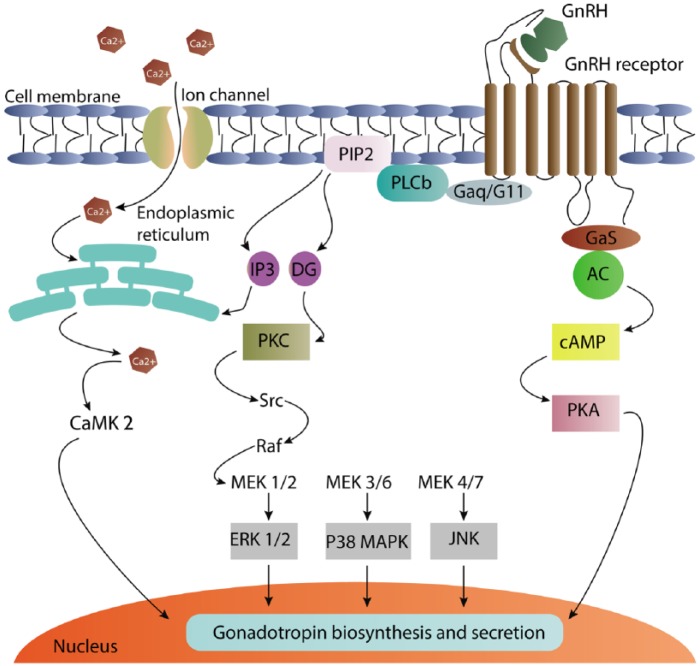

Human ERK1 and ERK2 genes are located on 16p11.2 and 22q11.21 chromosomes, respectively. Primary protein structure of ERK1 consists of 379 amino acids; however, this number in ERK2 primary protein structure is 360, with an 84% degree of identity.15 Activation of ERK signaling pathway is mostly initiated by cell membrane receptors, including receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), and ion channels. These receptors transduce extracellular signals to ERK1/2 by using adaptor proteins, such as growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (Grb2) and guanine nucleotide exchange factors like Son of Sevenless (SOS), causing activation of Ras kinase. Ras is then activated in guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-bonded conformation and transmits signals through activation of Raf-1, B-Raf, and A-Raf, leading to phosphorylation of MAPK/ERK kinases 1/2 (MEK1/2).16 Subsequently, MEK1/2 phosphorylate their specific substrates ERK1/2 on Thr and Tyr residues. Hence, MEK1/2 proteins are known as dual-specificity protein kinases (DUSPs) (Figure 1).17 ERK1/2 proteins are also identified as prodirected kinases that can phosphorylate Ser and Thr residues in the proximity of the amino acid proline.16,17

Figure 1.

Schematic activation of extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 1/2.

In response to extracellular stimuli, a kinase cascade is activated which leads to ultimate activation of ERK1/2. These central proteins can phosphorylate intracytoplasmic or nuclear substrates, mediating distinct cellular events.

ERK 1/2, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 1/2; Gα, G alpha subunit; GDP, guanosine diphosphate; GPCR, G-protein-coupled receptor; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; SOS, Son of Sevenless; Grb2, growth factor receptor-bound protein 2; MEK 1/2, MAPK/ERK kinase 1/2.

Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase signaling in hypothalamus–pituitary axis and ovarian physiology

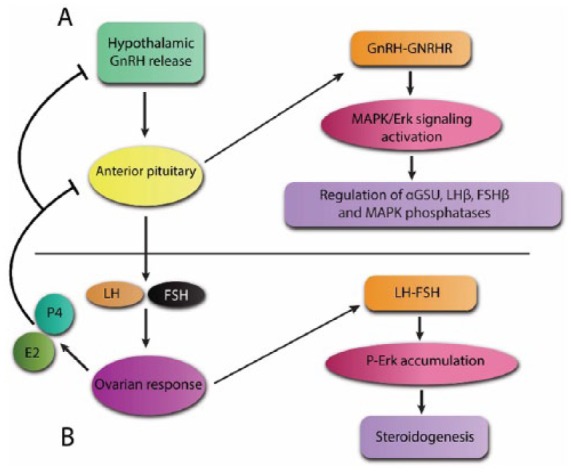

The pituitary gland is an endocrine tissue that regulates many aspects of mammalian physiology. The anterior pituitary consists of several hormone-producing cells such as gonadotropes, which produce LH and FSH in response to hypothalamic GnRH. These gonadotropins play a critical role in reproductive functions.18 ERK signaling pathway is activated following GnRH stimulation in gonadotropes. Also, several studies have shown the key role of ERK signaling in expression regulation of gonadotropes’ essential genes including αGSU, LHβ, and regulatory MAPK phosphatases (Figure 2).18

Figure 2.

Role of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular-signal-regulated kinase pathway in the pituitary and ovary.

(a) GnRH released from hypothalamus binds to GnRH receptor on anterior pituitary gonadotropic cells, leading to MAPK/ERK pathway activation. Activated ERK will regulate expression of genes involved in gonadotropin synthesis including αGSU, LHβ and FSHβ. The expression of MAPK phosphatases is also regulated by activated ERK in order to control ERK function; (b) pituitary-secreted LH and FSH in granulosa cell causes ERK activation and subsequent p-ERK accumulation and steroidogenesis. Synthesized steroids will inhibit pituitary and hypothalamic function in a negative feedback loop.

αGSU, gonadotropin α subunit; E2; estradiol, ERK, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; FSHβ, FSH beta; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; LHβ, LH beta; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; p-ERK, phosphorylated ERK; P4; progesterone; GNRHR, gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor.

In mammalian ovaries, oocytes are located in ovarian follicles and surrounded by granulosa cells (GCs) and cumulus cells, which exhibit endocrine and oocyte maturation control functions. Successful fertility outcome is strongly dependent on ovarian follicle growth, GC differentiation, oocyte maturity, and ovulation process.2,19 LH plays a crucial role in ovulation and has the capability of ERK1/2 activation. LH is also considered as an intrafollicular agent for cumulus-cell–oocyte complex (COC) expansion and oocyte maturation.20–22 Additionally, FSH promotes proliferation and differentiation of GCs and is a vital factor for successful fertility process as well as a key mediator of ERK phosphorylation.23 Fan and colleagues24 showed that female ERK1−/− and ERK2-germ-cell negative or negative (gc−/−) mice were fertile while ERK1/2gc−/− females could not ovulate and were completely infertile, with ovaries containing pre-ovulatory follicles but without corpora lutea (CLs). In addition, treatment of ERK1/2gc−/− immature females with exogenous hormones could not recover ovulation-associated events, including oocyte maturation, germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD), COC expansion, and follicle rupture, to form CLs. This treatment showed an elevated concentration of estradiol in serum with no increased progesterone level, representing endocrine changes in the ovaries of a mutant mouse. Targeted impairment of the Cebpb gene in GCs also demonstrated Cytosine Cytosine Adenine Adenine Thymine (CCAAT)/enhancer-binding protein–β (C/EBPβ) as a critical downstream mediator of ERK1/2 activation that forms together with an LH-regulated signaling pathway for ovulation control and luteinization-related processes.24

Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase signaling and gonadotropins interactions

Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase activation upon gonadotropin-releasing hormone intracellular signaling

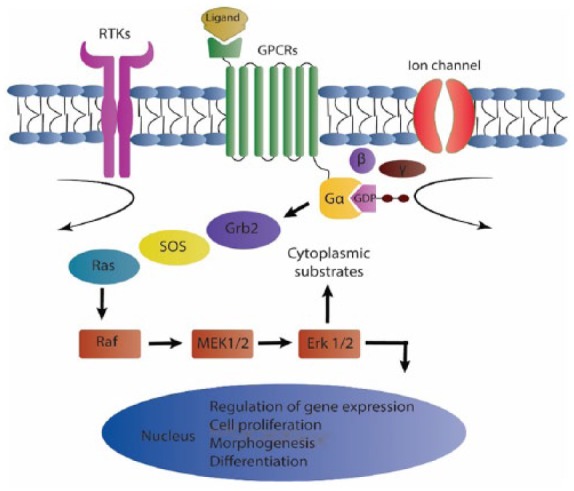

GnRH regulates the reproduction process through binding to GnRH receptor in pituitary gonadotrope cells, which produce and secrete gonadotropins, LH and FSH.25 The GnRH receptor is a member of the class A G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family.25,26 The initial phase of GnRH intracellular signaling includes the Gq/11-protein-mediated stimulation of phospholipase C (PLC), which leads to formation of 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). IP3 facilitates intracellular calcium release from endoplasmic reticulum (ER), whereas DAG activates protein kinase C (PKC) causing PKC-mediated ERK activation (Figure 3).26 Activation of MAPK proteins including ERK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), P38 MAPK, and ERK2 has been reported as implicated in GnRH-induced LH and FSH subunit expression.27 In addition, GnRH-mediated activated ERK also increases the expression of DUSPs, which lead to more rapid ERK-mediated negative-feedback loops, modulating the ERK responses to GnRH.26

Figure 3.

Schematic summary of gonadotropin-releasing hormone intracellular signaling.

Gq-protein-mediated stimulation of phospholipase Cβ (PLCb) is the initial phase of GnRH action, which leads to the formation of inositol-3-phosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). The release of intracellular calcium from endoplasmic reticulum is induced by IP3 and DAG activating protein kinase C (PKC) and ERK. GnRH also activates P38 MAPK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and calcium–calmodulin kinase II (CaMK II). Not predominantly, but GnRH is also coupled to GaS protein which are linked to adenylate cyclase and induces rapid cAMP production, which subsequently activates protein kinase A (PKA).

cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; ERK, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEK, MAPK/ERK kinase; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol biphosphate.

Role of extracellular-signal-regulated kinase in gonadotropin subunit gene expression

Despite the high degree of structural homology between these two kinases, different functions have been reported for ERK1 and ERK2.15,28 As we recently reported in our previous work,29 ERK2 downregulation by specific siRNAs could promote a higher chemosensitivity compared with an ERK1 knockdown in human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. Additionally, ERK2 knockdown resulted in a higher overexpression of ERK1 than that of ERK2 in ERK1 knockdown, suggesting the crucial role of ERK2 in cancer. Furthermore, it has been shown that ERK1-mutant mouse fibroblasts sustain ERK2 activation, resulting in c-fos and zif-268 overexpression and consequent elevated cell proliferation. These data indicate that ERK1 elimination can facilitate ERK2 signaling.30 For instance, the ERK1− mouse is viable and fertile whereas ERK2 knockout is embryonic lethal.31,32 Accordingly, ERK2 plays an important role in embryonic development.33 Bliss and colleagues18 reported that LHβ expression is significantly decreased in ERK1/2 double knockout (DKO) female mice, although the reduction in FSHβ expression was not statistically significant. Furthermore, early growth response factor-1 (egr-1) expression, a transcriptional factor playing an important role in the regulation of LHβ transcription, was not elevated in DKO female mice even after GnRH stimulation. However, little changes were observed in FSHβ expression following endogenous GnRH stimulation in male gonadotrope-specific ERK knockout mice. In contrast, ovariectomy led to a significant increase in FSHβ messenger ribonucleic acid, suggesting an enhancement in the function of GnRH.

Moreover, rapid and sustained ERK1/2 phosphorylation and activation following slow-pulse frequencies of GnRH was associated with higher levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2) compared with that following rapid GnRH frequencies. Distinct effects of GnRH pulses on patterns of ERK activation or deactivation may be responsible for different LHβ and FSHβ subunit expression levels.34 Armstrong and colleagues35 also reported ERK nuclear translocation after pulsatile treatment of GnRH in Hela cells. Although they concluded that ERK is not a GnRH signaling decoder, effects of ERK downstream translocation that may take a longer time to reach basal levels after each pulse can provide an explanation for differential response of gonadotropins to GnRH.

Previous studies have also introduced MAPK phosphatases (MKP) as critical mediators for different phosphorylation patterns of ERK1/2 following GnRH pulsatile stimulation.36 Donaubauer and colleagues23 in an animal model study reported that both MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK) and protein kinase A (PKA) are required for FSH-mediated ERK phosphorylation (Thr202/Tyr204) in rat GCs. Additionally, FSH causes ERK phosphatase’s inactivation through PKA, leading to cellular p-ERK accumulation.23 Evaluation of specific phosphatase inhibitors also revealed that MKP3 (DUSP6) is the main active phosphatase in GCs in the absence of FSH.23 According to other studies, MKP1 and MKP2 gene expressions are elevated in response to GnRH in gonadotrope cell lines and in vivo models.37 However, Hela cells transfected with GnRH and ERK-green-fluorescent protein (GFP) showed only a 10–20% increase in MKPs after continuous GnRH stimulation compared with controls.38 Studies on LβT2 cells have revealed a significant increase in expression of DUSP1 after fast GnRH pulses compared with its slow pulses. MAP3K1 overexpression causes overactivation of FSHβ and LHβ promoters in these cells, an effect that is inhibited in cotransfection of DUSP1 expression vectors.39 DUSP1 can also inhibit the expression of FSHβ and LHβ after GnRH pulsatile expression, indicating the role of this phosphatase and other MKPs in gonadotropins’ transcription.38

The role of mitogen-activated protein kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation status in the action of gonadotropins on steroidogenesis

The ERK1/2 signaling pathway is involved in steroidogenesis by regulation of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) expression. However, several inconsistencies have been reported in different steroidogenic tissues.40 For instance, ERK1/2 activation by human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) increases StAR and testosterone production in primary cultured rat Leydig cells. Meanwhile, ERK1/2 inhibition by MEK1/2-specific inhibitor U0126 reduces the mentioned parameters.41 In contrast, it has been demonstrated that LH-induced steroidogenesis is reduced in rat primary Leydig cells and mouse tumoral Leydig cell line following increased StAR expression after ERK1/2 inhibition by U0126 and PD98059.42 Reports obtained from women participating in an in vitro fertilization (IVF) program indicated that granulosa cells are highly steroidogenic because of previous gonadotropin hormones’ stimulation.43 Freshly prepared granulosa cells failed to exhibit a consistent response to hCG/LH and no response to FSH in short-term cultures. However, in prolonged cultures with media containing no gonadotropins, FSH response was reestablished.43 Tajima and colleagues43 showed that LH, FSH, and forskolin stimulation of human and rat granulosa cells leads to elevated production and expression of progesterone and StAR, respectively. In this regard, these effects were augmented in the presence of ERK1/2-specific inhibitors, PD98059 and U0126. No significant changes were observed in P450 side-chain cleaving (P450scc) expression levels following described treatments. Additionally, LH or forskolin treatment significantly increased phosphorylation level of ERK1 and ERK2, which were apparently suppressed in the presence of ERK1/2 inhibitors.

Conclusion

Successful mammalian fertility is determined by a variety of parameters including oocyte maturity, ovulation, embryo formation, and implantation. MAPK/ERK is considered one of the most important intracellular signaling pathways that plays critical roles in different cellular processes. ERK1/2 activation following pulsatile secretion of GnRH mediates distinct reproductive-related events including regulation of LHβ and FSHβ expression, oocyte maturation, GVBD, CLs formation, and expansion of COCs. Therefore, activity regulation of ERK1 and ERK2 by their related upstream kinases and phosphatases can be considered an important process in gonadotropin production and secretion.

In this review, we summarized the recent findings on the quickly developing field of the MAPK roles in female reproduction. Considering the failure of current knowledge for managing female infertility, the present review will probably facilitate future study designs.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge the Department of Biochemistry and Clinical Laboratories at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Iran) for their great help.

Footnotes

Funding: This work has been done as part of the MSc thesis for Samira Kahnamouyi. This study was supported by Stem Cell Research Center at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Iran (Grant No.: 93/1-4/4).

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ORCID iD: Amir Mehdizadeh  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3029-4172

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3029-4172

Contributor Information

Samira Kahnamouyi, Stem cell Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Mohammad Nouri, Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Institute, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Laya Farzadi, Women Reproductive Health Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Masoud Darabi, Department of Biochemistry and Clinical Laboratories, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Vahid Hosseini, Department of Biochemistry and Clinical Laboratories, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Amir Mehdizadeh, Endocrine Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

References

- 1. Richards JS, Russell DL, Ochsner S, et al. Novel signaling pathways that control ovarian follicular development, ovulation, and luteinization. Recent Prog Horm Res 2002; 57: 195–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hunzicker-Dunn M, Maizels ET. FSH signaling pathways in immature granulosa cells that regulate target gene expression: branching out from protein kinase A. Cell signal 2006; 18: 1351–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Crowley W, Jr, Filicori M, Spratt D, et al. The physiology of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion in men and women. Recent Prog Horm Res 1985; 41: 473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Levine JE, Ramirez VD. Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone release during the rat estrous cycle and after ovariectomy, as estimated with push-pull cannulae. Endocrinology 1982; 111: 1439–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pierce JG, Parsons TF. Glycoprotein hormones: structure and function. Annu Rev Biochem 1981; 50: 465–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wayne CM, Fan H-Y, Cheng X, et al. Follicle-stimulating hormone induces multiple signaling cascades: evidence that activation of Rous sarcoma oncogene, RAS, and the epidermal growth factor receptor are critical for granulosa cell differentiation. Mol Endocrinol 2007; 21: 1940–1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fan H-Y, Richards JS. Minireview: physiological and pathological actions of RAS in the ovary. Mol Endocrinol 2010; 24: 286–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Widmann C, Gibson S, Jarpe MB, et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinase: conservation of a three-kinase module from yeast to human. Physiol Rev 1999; 79: 143–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang W, Liu HT. MAPK signal pathways in the regulation of cell proliferation in mammalian cells. Cell Res 2002; 12: 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roberson MS, Misra-Press A, Laurance ME, et al. A role for mitogen-activated protein kinase in mediating activation of the glycoprotein hormone alpha-subunit promoter by gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Mol Cel Biol 1995; 15: 3531–3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sundaresan S, Colin IM, Pestell R, et al. Stimulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase by gonadotropin-releasing hormone: evidence for the involvement of protein kinase C. Endocrinology 1996; 137: 304–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weck J, Fallest PC, Pitt LK, et al. Differential gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulation of rat luteinizing hormone subunit gene transcription by calcium influx and mitogen-activated protein kinase-signaling pathways. Mol Endocrinol 1998; 12: 451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Call GB, Wolfe MW. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone activates the equine luteinizing hormone β promoter through a protein kinase C/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Biol Reprod 1999; 61: 715–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yokoi T, Ohmichi M, Tasaka K, et al. Activation of the luteinizing hormone β promoter by gonadotropin-releasing hormone requires c-Jun NH2-terminal protein kinase. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 21639–21647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mehdizadeh A, Somi MH, Darabi M, et al. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 in cancer therapy: a focus on hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Biol Rep 2016; 43: 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wortzel I, Seger R. The ERK cascade: distinct functions within various subcellular organelles. Genes Cancer 2011; 2: 195–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pearson G, Robinson F, Beers Gibson T, et al. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr Rev 2001; 22: 153–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bliss SP, Miller A, Navratil AM, et al. ERK signaling in the pituitary is required for female but not male fertility. Mol Endocrinol 2009; 23: 1092–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Matzuk MM, Burns KH, Viveiros MM, et al. Intercellular communication in the mammalian ovary: oocytes carry the conversation. Science 2002; 296: 2178–2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Park J-Y, Su Y-Q, Ariga M, et al. EGF-like growth factors as mediators of LH action in the ovulatory follicle. Science 2004; 303: 682–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hsieh M, Lee D, Panigone S, et al. Luteinizing hormone-dependent activation of the epidermal growth factor network is essential for ovulation. Mol Cel Biol 2007; 27: 1914–1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shimada M, Hernandez-Gonzalez I, Gonzalez-Robayna I, et al. Paracrine and autocrine regulation of epidermal growth factor-like factors in cumulus oocyte complexes and granulosa cells: key roles for prostaglandin synthase 2 and progesterone receptor. Mol Endocrinol 2006; 20: 1352–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Donaubauer EM, Law NC, Hunzicker-Dunn ME. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)-dependent regulation of extracellular regulated kinase (ERK) phosphorylation by the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase phosphatase MKP3. J Biol Chem 2016; 291: 19701–19712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fan H-Y, Liu Z, Shimada M, et al. MAPK3/1 (ERK1/2) in ovarian granulosa cells are essential for female fertility. Science 2009; 324: 938–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Flanagan CA, Manilall A. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor structure and GnRH binding. Front Endocrinol 2017; 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garner KL, Perrett RM, Voliotis M, et al. Information transfer in gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) signaling extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-mediated feedback loops control hormone sensing. J Biol Chem 2016; 291: 2246–2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Haj M, Wijeweera A, Rudnizky S, et al. Mitogen-and stress-activated protein kinase 1 is required for gonadotropin-releasing hormone-mediated activation of gonadotropin α-subunit expression. J Biol Chem 2017; 292: 20720–20731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mazzucchelli C, Vantaggiato C, Ciamei A, et al. Knockout of ERK1 MAP kinase enhances synaptic plasticity in the striatum and facilitates striatal-mediated learning and memory. Neuron 2002; 34: 807–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mehdizadeh A, Somi MH, Darabi M, et al. Liposome-mediated RNA interference delivery against ERK1 and ERK2 does not equally promote chemosensitivity in human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol 2017; 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vantaggiato C, Formentini I, Bondanza A, et al. ERK1 and ERK2 mitogen-activated protein kinases affect Ras-dependent cell signaling differentially. J Biol 2006; 5: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nekrasova T, Shive C, Gao Y, et al. ERK1-deficient mice show normal T cell effector function and are highly susceptible to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol 2005; 175: 2374–2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yao Y, Li W, Wu J, et al. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 is necessary for mesoderm differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100: 12759–12764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Newbern J, Zhong J, Wickramasinghe RS, et al. Mouse and human phenotypes indicate a critical conserved role for ERK2 signaling in neural crest development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105: 17115–17120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kanasaki H, Bedecarrats GY, Kam K-Y, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse frequency-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways in perifused LβT2 cells. Endocrinology 2005; 146: 5503–5513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Armstrong SP, Caunt CJ, Fowkes RC, et al. Pulsatile and sustained gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor signaling does the ERK signaling pathway decode GnRH pulse frequency? J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 24360–24371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ciccone NA, Kaiser UB. The biology of gonadotroph regulation. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2009; 16: 321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang T, Roberson M. Role of MAP kinase phosphatases in GnRH-dependent activation of MAP kinases. J Mol Endocrinol 2006; 36: 41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thompson IR, Kaiser UB. GnRH pulse frequency-dependent differential regulation of LH and FSH gene expression. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2014; 385: 28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Purwana IN, Kanasaki H, Mijiddorj T, et al. Induction of dual-specificity phosphatase 1 (DUSP1) by pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulation: role for gonadotropin subunit expression in mouse pituitary LbetaT2 cells. Biol Reprod 2011; 84: 996–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Manna PR, Stocco DM. The role of specific mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascades in the regulation of steroidogenesis. J Signal Trans 2010; 2011: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Martinelle N, Holst M, Soder O, et al. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases are involved in the acute activation of steroidogenesis in immature rat Leydig cells by human chorionic gonadotropin. Endocrinology 2004; 145: 4629–4634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Martinat N, Crépieux P, Reiter E, et al. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) 1, 2 are required for luteinizing hormone (LH)-induced steroidogenesis in primary Leydig cells and control steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) expression. Reprod Nutr Dev 2005; 45: 101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tajima K, Dantes A, Yao Z, et al. Down-regulation of steroidogenic response to gonadotropins in human and rat preovulatory granulosa cells involves mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and modulation of DAX-1 and steroidogenic factor-1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88: 2288–2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]