ABSTRACT

Purpose

Community-level group participation is a structural aspect of social capital that may have a contextual influence on an individual’s health. Herein, we sought to investigate a contextual relationship between community-level prevalence of sports group participation and depressive symptoms in older individuals.

Methods

We used data from the 2010 Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study, a population-based, cross-sectional study of individuals 65 yr or older without long-term care needs in Japan. Overall, 74,681 participants in 516 communities were analyzed. Depressive symptoms were diagnosed as a 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale score of ≥5. Participation in a sports group 1 d·month−1 or more often was defined as “participation.” For this study, we applied two-level multilevel Poisson regression analysis stratified by sex, calculated prevalence ratios (PR), and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

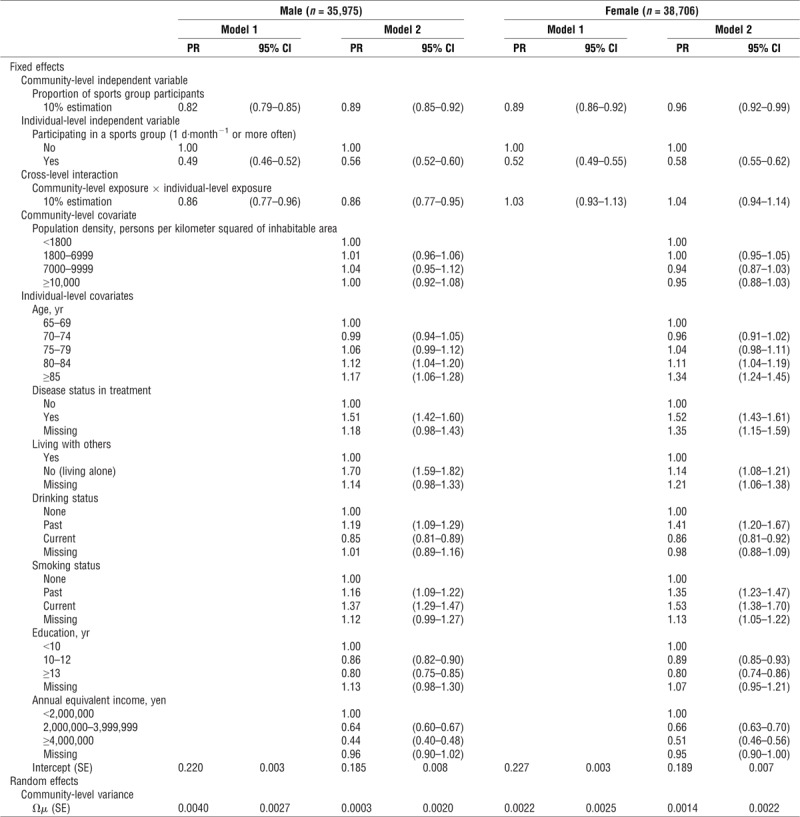

Overall, 17,420 individuals (23.3%) had depressive symptoms, and 16,915 (22.6%) participated in a sports group. Higher prevalence of community-level sports group participation had a statistically significant relationship with a lower likelihood of depressive symptoms (male: PR, 0.89 (95% CI, 0.85–0.92); female: PR, 0.96 (95% CI, 0.92–0.99), estimated by 10% of participation proportion) after adjusting for individual-level sports group participation, age, diseases, family form, alcohol, smoking, education, equivalent income, and population density. We found statistically significant cross-level interaction terms in male participants only (PR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.77–0.95).

Conclusions

We found a contextual preventive relationship between community-level sports group participation and depressive symptoms in older individuals. Therefore, promoting sports groups in a community may be effective as a population-based strategy for the prevention of depression in older individuals. Furthermore, the benefit may favor male sports group participants.

Key Words: DEPRESSION, ELDERLY, MULTILEVEL ANALYSIS, SOCIAL CAPITAL, EXERCISE EPIDEMIOLOGY, JAPAN GERONTOLOGICAL EVALUATION STUDY

Depression in older adults is strongly associated with being house bound and isolated (1), which may lead to a decline in physical and cognitive function and eventually to premature death (2). Physical activity, which is a modifiable behavior, can prevent or alleviate depressive symptoms in older individuals (3–6). In particular, group participation in sports may have positive effects of physical activity and social participation on mental health (7–11), leading to enjoyment, enhanced self-esteem, and decreased stress (8). Increasing the frequency of sports group participation may alleviate the worsening depressive symptoms among older individuals who walk at an even rate compared with those who increase their daily walking time (11). Participation in a sports group may also lower the risk of functional disability compared with participation in other kinds of social activities (e.g., local community, volunteer, industry, or politics) (12). Therefore, growing evidence suggests that sports group participation may have preventive effects on psychological and physical functional decline in older individuals.

The definition of social participation mostly focuses on a “person’s involvement in activities that provide interaction with others in society or the community” and is an index of social capital (13). There has been an increasing application of social capital in public health (14). According to Putnam (15), social capital refers to “features of social organization, such as trust, norms, and networks, that can improve the efficacy of society by facilitating coordinated actions” (p. 167). It is also described as “resources that are accessed by individuals as a result of their membership of a network or a group” (p. 291) (16). Social capital has two levels: individual level, which refers to resources accessed by the individual through their ego-centered networks, and group level, which pertains to a characteristic of the whole social network (16). Findings among studies investigating the relationship between group (community)-level social capital or social participation and older individuals’ mental health were inconsistent. Although community-level bonding social capital (perceived homogeneous network) and bridging social capital (perceived heterogeneous network) do not necessarily improve mental health in older individuals (17), Saito and colleagues (18) revealed that a composite score of community-level social participation had a protective relationship for individual-level poor self-rated health and depressive symptoms in older individuals after adjusting for individual-level social participation. Inconsistent with this study, community-level formal group participation did not correlate with older depressed individuals’ symptoms in another study with small samples (19). There is little evidence to support an association between community-level sports group participation and depressive symptoms in older individuals.

The present study investigated whether older individuals living in community areas with a higher prevalence of sports group participation among older individuals are less likely to have depressive symptoms compared with those living in community areas with a lower prevalence of such participation after controlling for individual-level sports group participation. We performed community- and individual-level multilevel analyses to clarify the contextual relationship between community-level sports group participation and depressive symptoms in older individuals.

METHODS

Study sample

We used cross-sectional data from the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES). The JAGES project is an ongoing cohort study investigating social and behavioral factors related to the loss of health with respect to functional decline or cognitive impairment among individuals 65 yr or older (20). Between August 2010 and January 2012, a total of 169,215 community-dwelling people 65 yr or older were randomly selected from 31 municipalities including metropolitan, urban/semiurban, and rural communities in 12 prefectures from as far north as Hokkaido (i.e., the northernmost prefecture) and as far south as Okinawa (i.e., the southernmost prefecture) in Japan and were mailed a set of questionnaires. Overall, 112,123 people participated (response rate, 66.3%). We used data from 74,681 respondents (valid response rate, 44.1%) in 516 community areas, after excluding (i) 46 community areas with ≤30 respondents each (a total of 980 respondents), (ii) 4099 respondents whose areas of residence were unknown, and (iii) 32,363 respondents whose status of sex, age, depressive symptoms, or extent of sports group participation were unknown. One community area was essentially equivalent to one elementary or junior high school district. Generally, a school district represents a geographical scale in which the Japanese elderly can travel easily by foot or bicycle (21). Therefore, the present study used the community area as a proxy for the neighborhoods of people in our sample. JAGES participants were informed that participation in the study was voluntary and that completing and returning the questionnaire via mail indicated their consent to participate in the study. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee at Nihon Fukushi University, Japan (Approval No.: 10-05).

Dependent variable

We assessed depressive symptoms using the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (22,23). Following previous research (22–24), mild or severe depressive symptoms (GDS ≥ 5) were set as an outcome of the present study. Cronbach’s α for internal consistency of the scale was 0.80 (24), and the cutoff point was previously validated as a screening instrument for major depressive disorder with 96% sensitivity and 95% specificity (24).

Community- and individual-level independent variables

Participants were queried on their frequency of sports group participation. Possible answers were ≥4 d·wk−1, 2–3 d·wk−1, 1 d·wk−1, 1–3 d·month−1, a few times a year, or zero. We defined participating 1 d·month−1 or more often as “participation” in a sports group (18,25) and aggregated individual-level sports group participation by community area as a community-level independent variable. Previous research (18) indicates that the correlation of the proportion of older individuals with depressive symptoms (GDS ≥ 5) in areas with community-level sports group participation 1 d·month−1 or more often (r = −0.355) tended to be strong compared with that with community-level sports group participation 1 d·wk−1 or more often (r = −0.314).

Covariates

Sex was controlled by conducting a stratified analysis. Age groups were categorized as 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, and ≥85 yr. To gather information on disease status in treatment, participants were asked if they were currently receiving any medical treatment; answer choices were yes and no. Participants were asked about household members living with and were categorized as living with others or living alone. Drinking status (none, past, or current), smoking status (none, past, or current), and education (<10, 10–12, or ≥13 yr) were classified by each answer choice. Annual equivalent income was calculated by dividing household income by the square root of the number of household members and categorized into three groups: <2,000,000; 2,000,000–3,999,999; or ≥4,000,000 yen. If participants did not respond to the individual-level covariates, corresponding observations were assigned to “missing” categories. As a community-level covariate, we calculated population density per square kilometer of inhabitable area for each community area and categorized into quartile categories (<1800, 1800–6999, 7000–9999, and ≥10,000 persons per kilometer squared).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the participants and community areas. In the data set, 35,975 men and 38,706 women were nested in 516 community areas (community level). Having depressive symptoms (GDS ≥ 5) was the outcome variable, and after adjusting for individual- and community-level covariates, the effect of community-level sports groups was inferred. To examine the contextual relationship of community-level prevalence of sports group participation to individual-level depressive symptoms, we applied two-level multilevel Poisson regression analysis (the individual as level 1 and the community as level 2) with random intercepts and fixed slopes and calculated the multilevel prevalence ratio (PR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Because percentages of individuals with depressive symptoms (23.3%) were >10%, adjusted odds ratio derived from logistic regression can no longer approximate the PR (26). Two models of analysis were used. Both community- and individual-level sports group participation and cross-level interaction terms were included in model 1. In model 2, all individual- and community-level covariates were added. The PR and 95% CI of community-level sports group participation were estimated by 10% of participation proportion. We used STATA 13/SE (StataCorp, College Station, TX) for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

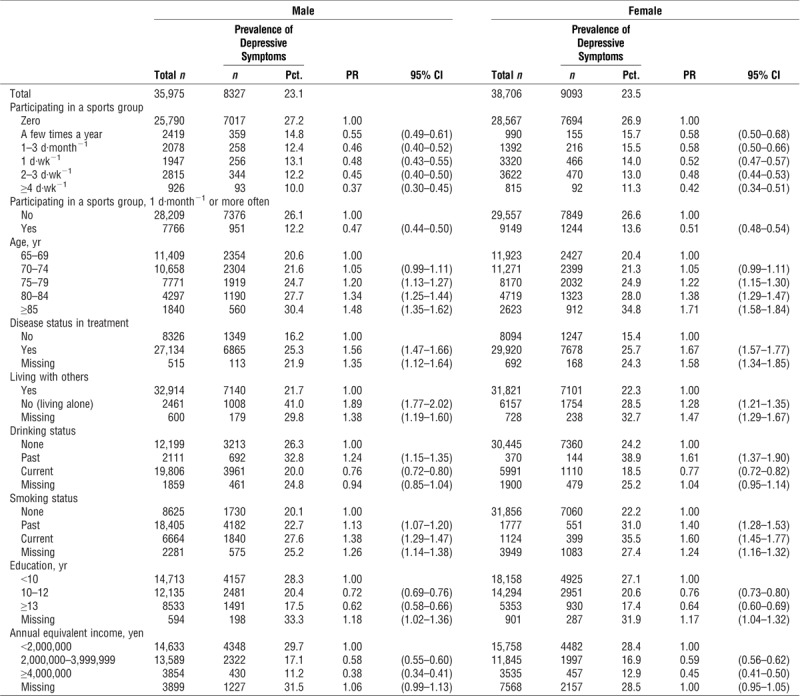

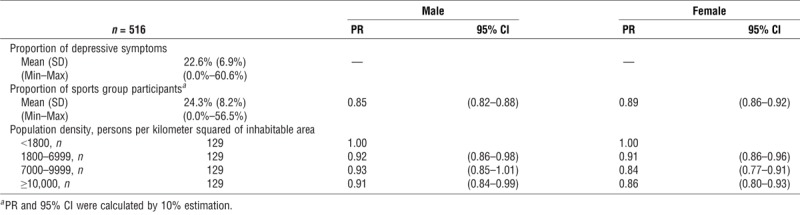

Of 74,681 analytic samples (mean age ± SD, 73.4 ± 6.0 yr in male and 73.8 ± 6.3 yr in female participants), 17,420 (23.3%) had depressive symptoms and 16,915 (22.6%) participated in a sports group 1 d·month−1 or more often. When the proportions of depressive symptoms and sports group participation were calculated for each community area, the ranges were 0.0%–60.6% and 0.0%–56.5%, respectively. Tables 1 and 2 show the descriptive statistics and crude PR (95% CI) for having depressive symptoms for the individual- and community-level variables by sex, respectively. Participants of both sexes with older age who had disease(s) under treatment, lived alone, were past drinkers, or were past/current smokers were more likely to have depressive symptoms. Participants of both sexes who were current drinkers, with higher educational levels, and higher equivalent incomes were less likely to have depressive symptoms. Compared with male and female participants who lived in community areas with first (lowest) quartile of population density, those who lived in areas with the second and fourth (highest) quartiles as well as female participants who lived in areas with the third quartile were less likely to have depressive symptoms. Mean proportions of sports group participants by population density categories were 18.9%, 25.6%, 26.2%, and 26.0% from the first, second, third, and fourth quartiles of population density, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of respondents and their associated PR for having depressive symptoms.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of community areas and their associated prevalence.

Table 3 shows the results of the multilevel Poisson regression analyses. Regardless of whether the model included covariates and sex, community-level higher prevalence of sports group participation had a statistically significant relationship with lower likelihood of depressive symptoms (male: PR, 0.89 (95% CI, 0.85–0.92); female, PR, 0.96 (95% CI, 0.92–0.99)) in the fully adjusted model estimated by 10% of participation proportion. Individual-level sports group participation also had a significant relationship with low likelihood of depressive symptoms (male: PR, 0.56 (95% CI, 0.52–0.60); female: PR, 0.58 (95% CI, 0.55–0.62), in the fully adjusted model). We found statistically significant cross-level interaction terms in male participants only (PR, 0.86 (95% CI, 0.77–0.95), in the fully adjusted model).

TABLE 3.

Association of depressive symptoms with community- and individual-level variables determined by multilevel Poisson regression.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to find the contextual relationship between community-level prevalence of sports group participation in older individuals and depressive symptoms in older individuals. A 10% increase in community-level sports group participation was associated with an 11% and 4% reduction in the prevalence of depressive symptoms after adjusting for individual-level sports group participation and covariates. Not all older individuals are able to participate in a sports group because of factors such as work, lower socioeconomic status (i.e., lower income and lower educational attainment), or less social support (27). Furthermore, not all of those individuals are physically active because of demographic and biological, psychosocial, behavioral, social and cultural, and environmental factors (28). The results of the present study suggested that promoting sports groups in a community may be effective for the prevention of depression not only in sports group participants but also in nonparticipants having those barriers.

The individual-level relationship between sports group participation and mental health in adults has been frequently discussed in previous reports (7–10). A systematic review indicated consistent evidence that club- and team-based sports participation, when compared with individual forms of physical activity, was associated with improved psychological and social health (7). On the basis of a 6-yr longitudinal study using nationally representative data in Japan (10), adults 50–59 yr old who participated in exercise or sports activities were less likely to have worse mental health compared with those who did not participate. In the current study, we also found an individual-level preventive relationship of sports group participation with depressive symptoms in older individuals. The reciprocals of the PR for participating in a sports group were 1.79 (1/0.56) in male and 1.72 (1/0.58) in women. Male sports group participation may mitigate the adverse effects of living alone on depressive symptoms (PR, 1.70). In women, sports group participation may help in overcoming the adverse effects of disease status in treatment (PR, 1.52) and smoking (PR, 1.53). Furthermore, it is worth noting that the mitigational relationship of 10% increases in community-level sports group participation, which were estimated by the reciprocals of the PR (1.12 in men and 1.04 in women), was comparable with the age-related differences by 15 yr in men (PR, 1.12) and 10 yr in women (PR, 1.04).

Among fundamental dimensions of social capital, the previous report suggested that community-level social participation was more closely related to older individuals’ depressive symptoms than was social cohesion and reciprocity (18). In that study, community-level social participation was evaluated by merging sports group, volunteer group, and hobby activity participation. Those groups with egalitarian relationships could be categorized as horizontal social capital and had a stronger contextual association with individuals’ health status than were groups with hierarchical relationships (i.e., vertical social capital) (29,30). Even when extracting sports group participation in the present study, we found that the protective relationship with mental health remained.

Social contagion, informal social control, and collective efficacy are regarded as pathways from group-level social capital to individual-level health outcomes (16). Social contagion references the notion that behaviors spread more quickly through a tightly knit social network (16). Sometimes the behavior that spreads via the network can promote healthy lifestyle changes, that is, the spread of smoking cessation (31). Informal social control refers to the ability of adults in a community to maintain social order, that is, to step in and intervene when they witness deviant behavior (16). In relation to the present study, some older individuals may be encouraged by sports group participants to get more exercise or take up a sport irrespective of whether it is an individual or a team-based sport. Collective efficacy is the group-level analog of the concept of self-efficacy and refers to the ability of the collective to mobilize to undertake collective action (16,32). Facilities, systems, bylaws for health promotion, or sports business and management may develop to reflect the opinions and actions of communities with many sports groups and participants. Group-level mechanisms of widespread sports group participation may result in positive spillover effects.

In the present study, a statistically significant cross-level interaction term was observed in men only, suggesting that male sports group participants living in community areas with a higher prevalence of sports group participation might be less likely to have depressive symptoms compared with those living in community areas with a lower prevalence of sports group participation. One of the possible benefits in group sports is the opportunity to play key roles in those groups. Takagi and colleagues (21) reported that Japanese older men who held group leadership positions reported lower depressive symptoms than those who participated but did not have leadership roles. However, this interaction effect did not apply to women. Because Japanese society is characterized by strong patriarchal values, men seek meaning and identity by being valued in the workplace (21). Male retirees may feel rewarded by seeking positions of authority or responsibility within the social organizations in which they participate. It is assumed that a community with many sports group participants naturally also has many sports groups. Accordingly, leadership positions for managing such groups are necessary. Therefore, older male participants who live in an active area with sports groups may have opportunities to fill these key roles.

The strength of the present study is its large, nationwide, population-based sample enabling sex-stratified community- and individual-level multilevel analysis for clarifying the contextual relationship of sports group participation. However, the study has several limitations. First, reverse causality could occur because of the nature of the cross-sectional design, and further longitudinal studies are needed to resolve this limitation. Second, the response rate and the valid response rate were 66.3% and 44.1%, respectively; therefore, selection bias may have affected the results. Several missing values may also bring systematic bias. In our previous study, we reported that both response rates and percentage of sports group participants with lower incomes were significantly lower than those in participants with higher incomes (33). Furthermore, respondents with unknown status of depressive symptoms or extent of sports group participation reported lower equivalent income compared with valid respondents in our survey (data not shown). The present study showed that respondents with lower income tended to have depressive symptoms. Therefore, nonrespondents or respondents who were excluded from the analysis might have worse depressive symptoms and be less likely to participate in sports groups compared with valid respondents. Although the results showed a significant relationship of sports group participation with depressive symptoms, this slightly low valid response rate might attenuate the relationship. Third, we could not discuss the preferable frequency of sports group participation because we set the cutoff point for participation/nonparticipation to only one time point: 1 d·month−1 or more often/less than 1 d·month−1. Although we attempted an analysis in which the cutoff was set to 1 d·wk−1 or more often/less than 1 d·wk−1, the models did not converge. However, we believe “at least 1 d·month−1” to be an adequate and feasible frequency for both individuals who are not familiar with sports and those who want to establish a leadership position and manage a sports group in their community.

CONCLUSIONS

Older individuals living in community areas with a higher prevalence of sports group participation in older individuals are less likely to have depressive symptoms compared with those living in a community area with lower prevalence of participation after adjusting for individual-level sports group participation and other covariates; that is, we found a contextual preventive relationship between community-level sports group participation and depressive symptoms in older individuals. Furthermore, the benefit may favor male sports group participants. Promoting sports groups in a community may be effective as a population-based strategy for the preventing depression in older individuals regardless of each individual’s participation status.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant of the Strategic Research Foundation Grant-aided Project for Private Universities from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport, Science, and Technology, Japan (MEXT), 2009–2013, for the Center for Well-being and Society, Nihon Fukushi University; a Health Labour Sciences Research Grant, Comprehensive Research on Aging and Health (H22-Choju-Shitei-008, H24-Junkankitou-Ippan-007, H24-Chikyukibo-Ippan-009, H24-Choju-Wakate-009, H25-Kenki-Wakate-015, H25-Irryo-Shitei-003 (Fukkou), H26-Choju-Ippan-006, H28-Chouju-Ippan-02, H28-Ninchisho-Ippan-002) from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; JSPS KAKENHI (22330172, 22390400, 23243070, 23590786, 23790710, 24390469, 24530698, 24653150, 24683018, 25253052, 25870573, 25870881, 15K18174, 15KT0007, 15H01972, 16K16595, 17K15822) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; a grant from the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (24-17, 24-23); the Research and Development Grants for Longevity Science from AMED; a grant from the Japan Foundation for Aging and Health; and also the World Health Organization Centre for Health Development (WHO Kobe Centre; WHO APW 2017/713981). The funding sources had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. We declare that the results of the present study are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation, and do not constitute endorsement by the American College of Sports Medicine.

None of the authors have a conflict of interest in relation to this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Choi NG, McDougall GJ. Comparison of depressive symptoms between homebound older adults and ambulatory older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(3):310–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiske A, Wetherell JL, Gatz M. Depression in older adults. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5:363–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blake H, Mo P, Malik S, Thomas S. How effective are physical activity interventions for alleviating depressive symptoms in older people? A systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(10):873–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bridle C, Spanjers K, Patel S, Atherton NM, Lamb SE. Effect of exercise on depression severity in older people: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201(3):180–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauman A, Merom D, Bull FC, Buchner DM, Fiatarone Singh MA. Updating the evidence for physical activity: summative reviews of the epidemiological evidence, prevalence, and interventions to promote “active aging.” Gerontologist. 2016;56(2 Suppl):S268–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Windle G. Exercise, physical activity and mental well-being in later life. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2014;24(4):319–25. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eime RM, Young JA, Harvey JT, Charity MJ, Payne WR. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for adults: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanamori S, Takamiya T, Inoue S. Group exercise for adults and elderly: determinants of participation in group exercise and its associations with health outcome. J Phys Fitness Sports Med. 2015;4(4):315–20. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Street G, James R, Cutt H. The relationship between organised physical recreation and mental health. Health Promot J Austr. 2007;18(3):236–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeda F, Noguchi H, Monma T, Tamiya N. How possibly do leisure and social activities impact mental health of middle-aged adults in Japan? An evidence from a national longitudinal survey. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0139777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuji T, Sasaki Y, Matsuyama Y, et al. Reducing depressive symptoms after the Great East Japan Earthquake in older survivors through group exercise participation and regular walking: a prospective observational study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3):e013706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanamori S, Kai Y, Aida J, et al. Social participation and the prevention of functional disability in older Japanese: the JAGES cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levasseur M, Richard L, Gauvin L, Raymond E. Inventory and analysis of definitions of social participation found in the aging literature: proposed taxonomy of social activities. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(12):2141–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murayama H, Fujiwara Y, Kawachi I. Social capital and health: a review of prospective multilevel studies. J Epidemiol. 2012;22(3): 179–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Putnam RD. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press; 1993. pp. 167. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social capital, social cohesion, and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Glymour MM, editors. Social Epidemiology. 2nd ed New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2014. pp. 290–319. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murayama H, Nofuji Y, Matsuo E, et al. Are neighborhood bonding and bridging social capital protective against depressive mood in old age? A multilevel analysis in Japan. Soc Sci Med. 2015;124:171–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saito M, Kondo N, Aida J, et al. Development of an instrument for community-level health related social capital among Japanese older people: the JAGES project. J Epidemiol. 2017;27(5):221–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuasa M, Ukawa S, Ikeno T, Kawabata T. Multilevel, cross-sectional study on social capital with psychogeriatric health among older Japanese people dwelling in rural areas. Australas J Ageing. 2014;33(3):E13–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kondo K. Progress in aging epidemiology in Japan: the JAGES project. J Epidemiol. 2016;26(7):331–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takagi D, Kondo K, Kawachi I. Social participation and mental health: moderating effects of gender, social role and rurality. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tani Y, Sasaki Y, Haseda M, Kondo K, Kondo N. Eating alone and depression in older men and women by cohabitation status: the JAGES longitudinal survey. Age Ageing. 2015;44(6):1019–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schreiner AS, Hayakawa H, Morimoto T, Kakuma T. Screening for late life depression: cut-off scores for the Geriatric Depression Scale and the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia among Japanese subjects. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(6):498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nyunt MS, Fones C, Niti M, Ng TP. Criterion-based validity and reliability of the Geriatric Depression Screening Scale (GDS-15) in a large validation sample of community-living Asian older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(3):376–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yokobayashi K, Kawachi I, Kondo K, et al. Association between social relationship and glycemic control among older Japanese: JAGES cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280(19):1690–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamakita M, Kanamori S, Kondo N, Kondo K. Correlates of regular participation in sports groups among Japanese older adults: JAGES cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0141638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, et al. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet. 2012;380(9838):258–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aida J, Hanibuchi T, Nakade M, Hirai H, Osaka K, Kondo K. The different effects of vertical social capital and horizontal social capital on dental status: a multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(4):512–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engström K, Mattsson F, Jarleborg A, Hallqvist J. Contextual social capital as a risk factor for poor self-rated health: a multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(11):2268–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(21):2249–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277(5328):918–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kondo K. Exploring “inequalities in health”: a large-scale social epidemiological survey for care prevention in Japan. [In Japanese] Tokyo (Japan): Igaku-Shoin Ltd.; 2007. pp. 87, 124. [Google Scholar]