Abstract

Objectives

Limited research exists on multilevel influences of intimate partner violence (IPV) among immigrant groups in the United States, particularly South Asians. Using a socioecological framework, this study examined risk and protective factors of IPV among a diverse group of South Asian immigrant survivors of IPV and identified their perceived need for services.

Method

Sixteen South Asian immigrant survivors were recruited from New York; Maryland; Virginia; and Washington, DC, using a snowball sampling method. Participants were 1st-generation and 2nd-generation immigrants born in India (n = 4), Bangladesh (n = 4), Pakistan (n = 5), the United States (n = 2), and Sri Lanka (n = 1). Data were collected using in-depth interviews (n = 16) and a focus group (n = 1). A thematic analysis procedure was used to analyze the data and to identify themes across different ecological levels.

Results

IPV was related to factors at multiple levels, such as cultural normalization of abuse, gender role expectations, need to protect family honor, arranged marriage system, abusive partner characteristics, and women’s fear of losing children and being on own. Protective factors included supportive family and friends, religion, safety strategies, education, and empowerment. Women highlighted the need for community education and empowerment efforts and culturally responsive services for addressing IPV in South Asian communities.

Conclusions

South Asian survivors of IPV have experienced, and some continue to experience, abuse due to factors operating at multiple levels of the ecological framework. Consideration of culturally specific risk and protective factors for IPV at multiple contexts in women’s lives could inform culturally responsive IPV prevention and intervention strategies for South Asian communities in the United States.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, South Asian immigrant women, protective factors, risk factors, ecological framework

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a serious, yet preventable, public health problem that occurs among all socioeconomic, religious, and cultural groups. Globally, 10% to 69% of women have reported experiencing physical violence by an intimate partner at some point in their life (Weil, 2016). Although IPV is experienced globally, the prevalence across countries varies. The global lifetime prevalence of IPV among ever-partnered women has been found to be 30%, with the highest prevalence of IPV (i.e., 37.7%) occurring in Southeast Asia (World Health Organization [WHO], 2013).

According to a U.S. Census Bureau (Hoeffel, Rastogi, Kim, & Shahid, 2012) report, approximately 3.2 million million South Asians live in the United States, their community having grown 81% from 2000 to 2010 (South Asian Americans Leading Together & Asian American Federation, 2012). Studies using community-based samples of South Asian immigrant women have reported past-year IPV prevalence up to 40% (Mahapatra, 2012; Raj & Silverman, 2003). This high prevalence rate may be attributed to patriarchal cultural norms, gendered racism, the arranged marriage system, cultural resistance to disclosing IPV to protect family honor, and societal views that normalize or support IPV under certain circumstances (e.g., inability to do household chores; Kallivayalil, 2004, 2010; Patel, 2007; Sabri, 2014).

South Asian immigrant women face complex issues, such as immigration threats from their partners, financial dependence on partners due to their immigrant status, and abuse from in-laws or extended families (Dasgupta, 2000). The patriarchal cultural system leads to financial dependence of women and pressure to uphold family values and honor (Kallivayalil, 2004). Unique cultural aspects of arranged marriages and community discourse on family behavior contribute to the mental and physical sufferings of South Asian immigrant women survivors of IPV (Kallivayalil, 2010). Violence by an intimate partner has been associated with a number of adverse health outcomes, such as depression, anxiety, traumatic brain injuries, HIV/sexually transmitted infection, and gynecological disorders (Breiding, Black, & Ryan, 2008; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015; Edwards, Black, Dhingra, McKnight-Eily, & Perry, 2009; WHO, 2012).

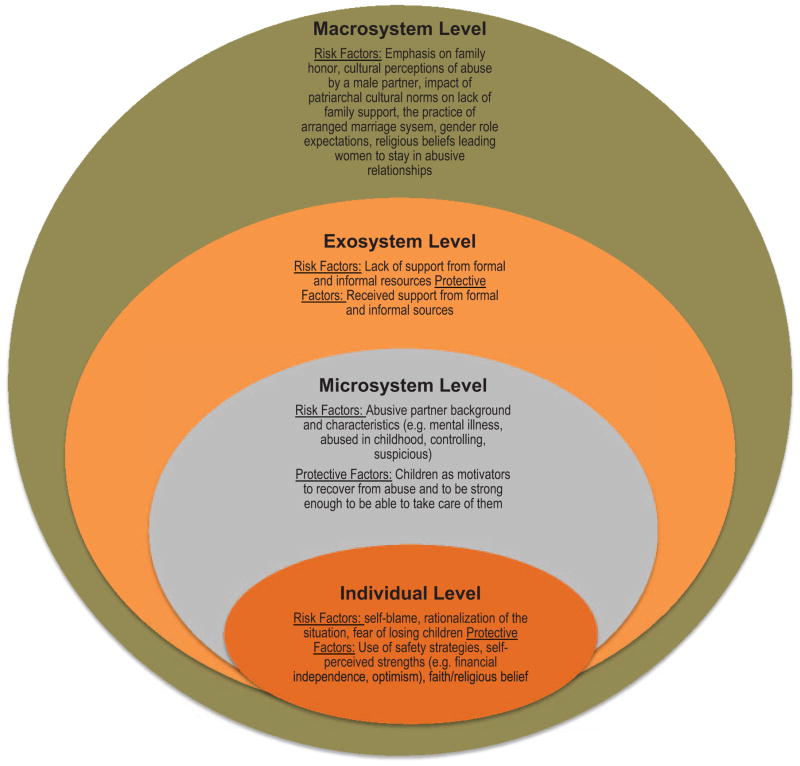

With such a high prevalence of IPV in the South Asian community and adverse effects of IPV on overall health and well-being of the victim, there is a need for culturally responsive IPV prevention and intervention strategies for South Asian immigrants. Because effective prevention and intervention of IPV requires reducing risk factors and strengthening protective factors, this study investigated risk and protective factors of IPV in a diverse sample of South Asian immigrant women. A socioecological framework (Heise, 1998) was used to identify risk and protective factors in multiple contexts: on the macrosystem, exosystem, microsystem, and individual levels. The framework by Heise (1998) was specifically applied to intimate partner violence against women.

The macrosystem-level risks represent the cultural views and attitudes toward IPV (see Figure 1), such as patriarchal cultural norms supporting use of violence in intimate partner relationships (Heise & Kotsadam, 2015; Pinnewala, 2009; Sabri, 2014). South Asian women may feel pressured to stay in an abusive relationship because of family reputation or honor (Ahmed, Reavey, & Majumdar, 2009). Research in South Asian Indian immigrant communities has reported a conscious effort by the South Asian families to resist or control the course of acculturation, thus maintaining certain traditional attitudes and values (Dasgupta, 1998).

Figure 1.

An ecological framework for domestic violence among South Asian immigrant women. See the online article for the color version of this figure.

Acculturation is a multidimensional process consisting of the merging of immigrants’ home country’s cultural practices and host country’s cultural practices (e.g., language use), values (e.g., individualistic vs. collectivist), and identifications (i.e., ethnic identity and national identity) as a result of continued exposure (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010). In acculturation, an immigrant adopts some (or all) aspects of the host country’s cultural streams and retains some (or all) aspects of the heritage country’s cultural streams (Sam & Berry, 2010; Schwartz et al., 2015). South Asian women, in the process of acculturation, may begin to adopt egalitarian gender role beliefs, assert their rights in relationships, and seek help to address abuse. This may place South Asian immigrant women at risk for further IPV and violence from other family members, depending upon the values and attitudes their families maintain. The gendered racism reflected in the South Asian womanhood objectifies them as weak, passive, exotic, and submissive (Patel, 2007).

The exosystem represents the social structures, both formal and informal, such as neighborhood, extended family, social networks, the state, and other social institutions (Pinnewala, 2009). At the exosystem level, factors such as language barriers and situational circumstances make it difficult for South Asian women to utilize supportive services (Finfgeld-Connett & Johnson, 2013). The microsystem includes family and marital relationships. Factors such as family interactions rooted in gendered racism (Patel, 2007), as well as partners’ and in-laws’ need to control, can be classified as risk factors at the microsystem level. The individual level represents the personal history of the partner or the woman (Pinnewala, 2009). A partner’s personal history of witnessing marital violence as a child, experiencing child abuse, having a personality disorder, and problem with alcohol use have been identified as risk factors for IPV in prior research (Brem, Florimbio, Elmquist, Shorey, & Stuart, 2018; Heise, 1998; Pinnewala, 2009). Women married at a younger age with little education and low socioeconomic status are likely to adhere to norms justifying IPV (Jesmin, 2015), which places them at risk for exposure to IPV.

Regarding protective factors at multiple levels, the existing research on abused South Asian immigrant women in Canada (Ahmad, Rai, Petrovic, Erickson, & Stewart, 2013) has reported protective influences of faith; seeking help through friends, family, and acquaintances; and using the Internet to find support such as shelters, language classes, immigration advice, and legal aid. Women cope with or recover from abuse by realizing their strengths, keeping busy, finding hobbies, and learning English (Ahmad et al., 2013). Studies on abused immigrant women from non-Asian groups in the United States (e.g., Africans and Mexicans) have reported protective factors such as female submissiveness or adherence to the female role in marriage and help received from family and friends and other members of the community (Kalunta-Crumpton, 2017; Kyriakakis, 2014). Submission to male authority and avoidance of confrontation or conflict in relationships (e.g., keeping quiet and not talking back, not saying or doing something to make the abuser angry) have been reported to protect women by preventing escalation of abuse. Survivors have reported that African and Mexican immigrant women often seek help from family and friends or even a pastor in more severe cases (Kyriakakis, 2014; Mose & Gillum, 2016). However, evidence on protective factors for abuse among South Asian immigrant women in the United States has been minimal.

There is a dearth of scholarly knowledge on multilevel risk and protective influences of IPV among diverse groups of South Asian immigrant women in the United States. To address this gap, this qualitative study used a socioecological framework to explore risk and protective factors of IPV in multiple contexts in South Asian immigrant women’s lives and identified their needs for services. The qualitative approach allowed an in-depth understanding of risk and protective factors of IPV among South Asian immigrant women that could not be gained by a quantitative study alone. The findings could inform culturally responsive IPV prevention and intervention strategies in South Asian communities in the United States.

Method

In this qualitative study, 16 in-depth interviews and one focus group (n = 5 participants) were conducted with South Asian immigrant survivors of IPV chosen using purposive and snowball sampling methods. Five participants in the focus group, who expressed interest in the interview portion of the study, also participated in the in-depth interviews. We concluded data collection when it appeared we had reached saturation and no new findings were emerging. Participants were recruited from organizations serving South Asian IPV survivors using verbal and written invitations to participate and through snowball sampling approach. Eligible women were English-speaking, first- or second-generation immigrant women from South Asia above 18 years of age who had experienced IPV within the past 2 years. Participants were residents in four regions of the United States: Maryland; Virginia; New York; and Washington, DC. With the exception of two participants who were second-generation immigrants, all participants were foreign-born (88%, n = 14/16). The countries of origin were India (n = 4), Bangladesh (n = 4), Pakistan (n = 7), and Sri Lanka (n = 1).

After oral consent was obtained, participants were interviewed in their homes. The focus group was also held in one of the participants’ home. Semistructured interview and focus group guides were used for data collection. A focus group allows researchers to gain insight into people’s shared understanding of a phenomenon (Bloor, Frankland, Thomas, & Robson, 2001) and was therefore useful in identifying relationship safety issues and areas of IPV prevention and intervention efforts for abused South Asian immigrant women. The focus group guide included questions on general risk and protective factors for IPV among South Asian women, characteristics of dangerous abusive relationships, perceptions or definitions of abuse in the South Asian culture, barriers to seeking help, and women’s needs for services. The in-depth interview guide focused on women’s own experiences in intimate partner relationships, their coping strategies, needs for services, and health concerns. We chose interviews versus focus groups for exploring women’s personal experiences and related issues because the women may not have been comfortable discussing these issues in a group setting. We kept detailed field notes to capture our thoughts and feelings toward the process and outcomes of the focus group and interview sessions. The sessions were recorded using digital recorder and transcribed verbatim. Women were provided with $30 incentive for participation and a list of resources. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the home institution of the study investigators.

The age range of participants was 31–48 years (M = 38, SD = 5.30). Except for the two second-generation immigrants, participants had been in the United States for an average of 13 years (SD = 6.45, range = 4–23 years). Most of them were separated or divorced from their partners (n = 11). Five were still married and living with their abuser. The majority of the participants were educated and had either completed college (62.5%, n = 10) or had some college (12.5%, n = 2) and were employed (75%, n = 12). The most common IPV experiences reported by women were both physical and psychological abuse (87.5%, n = 14). A large proportion of physically abused women also reported sexual abuse (78.6%, n = 11). Almost half reported severe physical abuse such as strangulation (50%, n = 8).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using a theoretical thematic analysis procedure (Braun & Clarke, 2006) and a constructionist perspective, where meanings and experiences of the participants are socially produced. Thematic analysis conducted with a constructionist perspective seeks to theorize the sociocultural and structural contexts that drive the individual accounts that are provided (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Individual experiences were analyzed and organized into overarching codes and themes that reflected contextual dimensions of women’s experiences. The analysis aimed to uncover interdependent risk and protective factors of IPV at multiple levels in women’s lives. The socioecological framework guided the analysis to identify risk and protective factors of IPV at each level of the ecological model and participants’ perceived needs for resources.

Using the recommended steps for thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), the analysis started with reading and rereading of the interview transcripts. This was followed by independent coding by two members of the research team to generate initial codes, search for themes, and group themes based on emerging patterns and similarities. Data analysis was cyclical and involved continuous development of new codes and constant comparison of themes. The participant responses were tallied, and prevalent codes describing different social ecological levels were grouped by similarity and relevance into themes. The themes were separated into macrosystem, exosystem, microsystem, and individual categories.

The qualitative analysis team included two professionals from social work and nursing fields: a qualitative senior researcher with a doctorate degree and a nursing student enrolled in the nursing master’s degree program. To ensure trustworthiness and credibility of the findings, the two team members met at multiple time points to discuss and compare generated codes and themes and to reconcile any discrepancies. The researchers engaged in a systematic process of reflexivity that included peer debriefing and field notes to ensure that data collection and analysis reflected the participants’ thoughts and opinions, not overly influenced by researchers’ bias.

Results

Macrosystem Level

The influence of societal and cultural contexts, part of the macrosystem (Heise, 1998), was reflected in participants’ discussions of the influences of cultural practices and beliefs on their abusive situations, such as emphasis on family honor, cultural perceptions of abuse by a male partner, impact of cultural norms on family support, the practice of arranged marriages, gender role expectations, and the double burden of working at a job and taking care of the housework.

Emphasis on family honor (n = 5)

The notion of family honor and stigma of IPV in South Asian communities play a role in devaluation of the social status of a family’s going through an IPV situation. The responsibility of abuse is placed on the woman, which is why her leaving the abuser is not considered an option. The abuse is considered a family affair, and if the community members come to know about it, it negatively impacts not only the survivor but also the future of her children.

As the cultural Indian girl, I’m not allowed to leave him, because I can change the man by changing my tactics. It will be a disgrace to the family. The children will have a black spot on their name, and no one will marry them when they grow older.

(Aruna, age 41, India)1

Describing an incident where she had a conflict with her husband in a public location, the same participant shared:

When my dad heard about the episode [in the public place], he told my colleague, “This is a black stain on the family.” My colleague said, “Your dad is not worried about your safety … the fact that your husband could kill you … that you need to get home safely. He’s worried about the black stain on the family.”

Another participant shared how abuse by a partner is a private family issue in South Asian communities: “It’s a very private thing. People do not even see it as an abuse. The South Asian community call it a family affair, so it should be dealt with in the family” (Jayanti, age 35, India). A participant in the focus group shared how men from her country of origin have killed or burnt their wives because they brought shame to the family.

Cultural perceptions of abuse (n = 5)

Survivors shared that abuse in the South Asian culture is largely overlooked or considered normal. For instance, two participants in the survivors’ focus group discussed how in some parts of South Asian culture, hitting is considered normal, so other forms of abuse, such as verbal abuse or forced sex, are not even discussed among members of the community. Sex was considered the marital right of the husband. One survivor shared that it is okay for a husband to force her wife to have sex when she is not sick. Another survivor shared that she could never refuse to have sex with her husband, because she was brought up that way. Although beating was reported by survivors as unacceptable, it was not reported as the general mind-set of people in the community:

We do not have any awareness. I do not think South Asian women think that being pushed or being beaten is abuse, because in some parts of South Asia beating is acceptable if you didn’t make the food right. So when that occurs over here, people think, “It’s okay. It’s normal.” Or “I did something. I deserved it.”

(Malika, age 33, Pakistan)

One survivor shared her thoughts about wife beating in a situation where a woman engaged in an extramarital relationship. “I don’t think that’s right, although in our culture in India or South Asia it’s just accepted” (Abida, age 47, Pakistan).

Impact of patriarchal cultural norms on family support (n = 4)

The patriarchal cultural norms that emphasize male authority and ownership of women place women at risk for IPV. In such a situation, women have a low status in the family and are also seen as responsible for keeping the family together. Thus, they are blamed by their families for any marital conflict. Women who challenge male authority are rebelling against the norms and therefore are at risk for violence from both her parental family and the husband or in-laws. A survivor who confronts her abuser faces violence from her own family as well as her husband:

After [mother] was done hitting me, he [husband] took over. He ripped my clothes off, everything, even my undergarments. My grandmother went inside and closed the door, and then eventually my mom left, too. He dragged me on all three levels of the house with my arm … poured beer on my head. And then he threw me under a cold shower and put me under an AC vent.

(Deepika, age 34, India)

The responsibility for resolving a marital conflict is often placed on a woman. For instance, a participant stated:

My own parents said, “If he got upset, what did you do to fix it?” My own brothers said, “Did you ever try to make good food in the house? Did you ever try to fix yourself to make it better?”

(Jasmin, age 37, United States)

Family pressure often brings women back to their abuser, as reflected in the following quote:

I left at least four or five times … I would feel like I was a burden on my parents and not welcomed. There’s something wrong with me, and that’s why the marriage was not working, so I went back.

(Aruna, age 41, India)

The in-laws’ involvement can further place a woman at risk for abuse. A survivor shared how in-laws contribute to violence in South Asian families:

If [the in-laws] become involved, they punish the girl. They ask their son to tell his wife “You’re ugly. You cannot do anything. You don’t know how to cook … how to take care of the elders. You have to respect my parents and the religion. You have to listen to your husband. You cannot say no to him.”

(Chandni, age 48, Bangladesh)

Arranged marriage system (n = 3)

According to some survivors, arranged marriage system is a normal occurrence in South Asian communities but prevents women from gaining independence because they are often married at a very young age. For example, a survivor shared:

I kept telling my family, “You’re marrying me off as an 18-year-old to somebody who was 14 years older than me.” Obviously, he’s going to be very controlling. He knows what he’s doing. He can manipulate a young child easily.

(Jasmin, age 37, United States)

Partners in arranged marriages sometimes do not know each other or want to get married, which can lead to conflict and abuse. Further, coresidence with abusive in-laws in arranged marriages can place women at risk for exposure to violence.

Some of our marriages are arranged so in-laws have a greater influence in marriage versus not having in-laws involved. If you’re living in a joint family system, then you have to deal with different people and situations. I do not think that the system that’s in place right now is equipped to deal with that … to identify issues or red flags where they can say, “Yes, this person is being abused.”

(Malika, age 33, Pakistan)

Prescribed gender norms and expectations surrounding women’s behavior and responsibilities in marriage (n = 8)

Prescribed gender norms in patriarchal societies and resulting expectations can place women at risk for exposure to violence. Women who do not fit the ideal image of a traditional South Asian woman are at risk for violence and being isolated from the community. One woman described how her growing up in the United States and adopting the U.S. lifestyle was portrayed in a negative way by her abusive partner: “I wear professional clothes … skirts and things because we grew up that way. He was trying to use this to paint a picture of me as like this bad loose woman” (Aruna, age 41, India).

Due to women’s low status in the family, working women face double burden. Whereas women are expected to earn on the job as well as take care of the house, men are not expected to share the household responsibilities. Working women, unable to cope with the demands of their jobs and traditional gender role expectations at home, are at risk for exposure to violence from husband and in-laws. Economic independence was reported as an added stress for women:

The woman has to earn plus have the babies plus do everything else. The men are losing any sense of taking care of the family, so they’re becoming more spineless. The guy expects his wife to work … to have the babies … to have food cooked and everything ready when he comes home.

(Aruna, age 41, India)

I did the laundry and forgot to put one sock away, and it laid upon the bed … and he’ll be like, “What is this?” “Just pick it up and put it in the drawer …” and he would just start hitting or pushing me. I would be like, “Stop it. I have stuff to do around the house. I have to cook. I have to put the baby to sleep.” It would just escalate.

(Pooja, age 36, India)

Roles of religion: Risk and protective (n = 11)

For some survivors, religion was a barrier that prevented them from moving out of the abusive relationship. Religion taught them that it was their responsibility to be there for their husbands. It was often used as a tool to get women to do what their husbands wanted. For instance, one participant mentioned, “You’re not allowed to refuse your husband to have sex except on your menstrual period, but if you are and he has a problem with it, he has a right to leave you” (Deepika, age 34, India). Another participant stated:

Religiously we’re taught that our responsibility is to be there for the husband. If that’s what your husband wants, be available to him, and I think it’s important. We shouldn’t always have the excuse of a headache. It becomes abusive because it leads to that severe abuse.

(Farah, age 33, United States)

Also, the religious belief in Hinduism that women can have only one husband in their lifetime is perceived as a barrier to leaving an abusive relationship.

For one survivor, religious guidelines brought awareness that abuse is not to be tolerated.

In the Islamic way, I can leave him, because in the book it says even if I do not enjoy him physically I do not have to be with him. That’s what opened my eyes. You have a right to be happy … to be treated well. You have a right to have a partner in your marriage and not an abuser.

(Aruna, age 41, India)

Women also reported religion as a protective factor and a source of strength that helped them cope with their abuse:

When I think there’s nobody there, I know that God’s there. I can go pray on the mat … read some Qur’an, and feel better, because ultimately we’re all going to die and go to him. You do not need anyone else. You make mistakes, but if you just hold onto his [God’s] rope and ask for him to help you, then you do not really need anyone else. Only he knows the whole truth of what you went through … I look at suffering as part of life. I always look at the people who have it worse.

(Aruna, age 41, India)

I started going to the church because of [abuse], and they are my family now. The amount of help you can get through the churches is tremendous.

(Meera, age 36, India)

I have faith in God. You have to have faith in God that it’s going to be okay.

(Chandni, age 48, Bangladesh)

Exosystem Level

The exosystem factors include social structures (formal and informal), such as the neighborhood, work, social networks, the state, and other social institutions (Pinnewala, 2009). The types of exosystems that marginalize South Asian immigrant women include social isolation and lack of access to support systems (Pinnewala, 2009). Participants discussed the different roles that formal and informal resources in their community played in their abusive situations.

Role of informal social networks (n = 8)

Lack of support was a big barrier in receiving help for abuse. According to two survivors, an abusive relationship can become a point of gossip with no concrete help from the community: “Community do not want to get involved … because men have the power, not women. Women can gossip with each other. They cannot help. The men think women are to blame” (Chandni, age 48, Bangladesh).

One survivor mentioned that leaving an abuser when there is no support is not the best step:

In some situations, life is worse for [survivors] when they leave. Because in [a relationship] they are dealing with one man who’s abusive toward them. In the situation out of that they are dealing with several men that are worse than that toward them. They do not have the education, a place to stay, [or] means of income and are very young. Life is much worse for them. It’s a compromise of your morals, of yourself, and of your body. In that situation it is probably better for them to stay and stabilize themselves than to leave.

(Deepika, age 34, India)

Other survivors discussed the protective role of friends, neighbors, and work colleagues in dealing with their abusive situations. For instance, one survivor shared:

These girls [her friends] are a huge support. They help out a lot. Even staff from my business saw how [my husband] behaved with me, because at that time I didn’t realize I was being abused, because sometimes you get so used to the way things are that it’s just normal. They pointed out, “He should not behave that way toward you. That’s not the right way anybody should treat their wives. You need to get away.”

(Jasmin, age 37, United States)

Role of formal sources of support (n = 7)

Survivors had mixed experiences with seeking help from formal sources of support. One survivor’s experience with a social worker ended with her children’s being placed in the custody of her abusive partner, even after trying to explain her situation. Two women described that lack of compassion in the court system or domestic violence shelter could worsen the situation for survivors:

I felt there’s no compassion or understanding in the court system for people who are going through domestic violence. [The] legal system is hard anyway. The person who is being abused is in a very sensitive situation. It’s hard for them to deal with these things, so it’s twice harder.

(Jayanti, age 35, India)

Domestic violence shelters are very horrible. When you are going through an emotionally and physically challenging situation, you need people who have compassion, who can understand your situation, but the volunteers [at the shelter] are rude. So I was like, this is worse than being with my abusive husband.

(Meera, age 36, India)

Police were mentioned as both a protective resource and a resource that was not helpful, particularly when the abuser was able to manipulate the situation. Police, according to some survivors, allowed them to separate themselves from their abusers. For other survivors, the abuser would manipulate the situation when police were called, putting them at increased risk for abuse. One survivor mentioned legal protection order as a protective resource. Counseling was reported to be helpful by three survivors. Two survivors identified health care providers as protective resources because of reasons such as noticing abuse early on and providing needed advice.

Perceived needs for services

Culturally responsive services (n = 10)

Some survivors expressed the need for services or care that is culturally responsive for South Asian immigrant survivors. For instance, a survivor mentioned how drinking and going out with friends as a coping strategy for abuse was not an option for her:

Support system is needed, but not the mainstream American support system, because it’s not the same values. They’ll tell you anything is possible in your life. We know that’s not true. It goes against our cultural or religious values. It’s going to harm us later on. Go out with your friends, drink, have fun. When they drink it’s out of guilt. It leads into depression.

(Deepika, age 34, India)

Another participant shared her opinion about the cultural competence of a service provider conducting assessments: “I have a friend … she’s a social worker. They’re trained to ask certain questions, but that training is for a certain demographic [group, which is the U.S. majority cultural group]” (Deepika, age 34, India).

A survivor shared how the lack of cultural competence of a provider can be a barrier to seeking help or coping with abuse:

It wouldn’t make sense for me to go to an American psychologist or a therapist or a counselor and talk to them about my marriage, because our dynamics are very different. If, for example, my husband’s sister has been one of the main issues of our marriage not working and if I go to an American counselor or psychologist or a therapist, they will just tell me not to talk to her or to avoid her, and that’s not something I can do. Someone that doesn’t know about our culture or traditions cannot really help us.

(Malika, age 33, Pakistan)

Community education and empowerment efforts (n = 9)

Survivors expressed the need for education and overall empowerment efforts through financial support, shelter and housing for South Asian immigrant women, especially those with language barriers.

Most women do not know how to go after the court, how to talk in English and explain the problem. That’s why they are not getting help.

(Sadia, ae 40, Bangladesh)

Educate women who are not in [a] domestic violence situation, so they can identify when they see someone in a domestic violence situation, what it looks like. So teaching women, equipping women, is more important. The help is very important, but education is so much more important.

(Meera, age 36, India)

Microsystem Level

The microsystem concerns the immediate context in which the abuse takes place (Pinnewala, 2009). Abusive partner characteristics and presence of children were identified as factors that expose women to abuse as well as protect them from its negative effects.

Abusive partner’s background and characteristics (n = 16)

Partner characteristics such as psychologically abusive behaviors (e.g., control and suspicion), mental illness, and childhood abuse were identified as factors that contribute to abuse in relationships. One participant observed signs of mental illness in her partner, which she attributed to part of the cause of abuse. “I’ve definitely observed the different personalities, the automatic switching from being very happy to being very aggressive, so there’s definitely bipolarism in there” (Malika, age 33, Pakistan). Another participant stated that inconsistent use of medications caused her partner to become violent. “The psychiatrist diagnosed him with depression. He would always go on and off medications. When he was on the medication, things were just fine. When he was not on his medication, just a nightmare” (Jasmin, age 37, United States).

One participant believed that her partner witnessed abuse as a child, which may have normalized such behavior in his mind, resulting in his aggressive behavior toward her. “I met his brother in Pennsylvania, and his brother told me it’s been in the family for years. His dad was abusive to his mom” (Pooja, age 36, India).

Protective role of children in the family (n = 6)

Although abusers’ characteristics and behaviors reportedly place survivors at risk for violence and have a negative impact on their self-esteem and overall well-being, children are a protective resource for coping with abuse. Survivors felt that kids were the major part of their lives that “kept them going.” They believed that they needed to move forward in their lives for the sake of their children. For example, one participant shared:

I have a son, so I need to make sure he’s taken care of financially and emotionally, so that helps me go on.

(Malika, age 33, Pakistan)

My daughter said, “Why you pushed my mom? I will kick you. He is shaky in front of the kids. He put the chair down and said, “I’m sorry, mommy.

(Sadia, age 40, Bangladesh)

When something goes wrong, my son says, “Mommy, it’s okay.” And he makes me sit and think, and I’m like, “You’re right. It can be so worse.”

(Pooja, age 36, India)

Individual Level

Whereas self-blame, rationalization of the situation, and fear of losing their children deterred survivors from leaving their abuser, safety strategies and reported strengths had a protective effect in promoting women’s safety. Culturally, women are socialized to feel extreme shame and guilt if they seek help, and there is a stigma attached to disclosure (Pinnewala, 2009).

Self-blame and rationalization of the situation (n = 10)

Rationalization of the abusive situation and the belief that they were to blame for the abuse, not their partners, deterred some survivors from seeking help, as reflected in the following statements by survivors:

For me the physical abuse happened a total of five times, but I ended up making excuses for it. “Okay. He was angry. He punched me.” “Oh he was angry. He threw a plate at me.” If you’re already in an abusive situation, then you start giving degrees to physical abuse until you get that knock-down beating sometimes before you step out of it … call someone or do something.

(Farah, age 33, United States)

Initially I didn’t want to talk to anyone about it because I thought that’s what a marriage is and maybe the issue was with me and not with him.

(Malika, age 33, Pakistan)

And then you will have no support, no medical health insurance. You’ll … basically … have to go look for a job, and … you may not even have a home. So all those scary thoughts like not only losing your husband, also losing everything else that comes with him … I rather be getting slapped around a little bit.

(Meera, age 36, India)

Fear of losing children (n = 8)

Having children with the abuser and the fear of losing children was identified as a barrier for women to break free from their abusive partner. For instance, one survivor shared:

When I met with the legal consultant, she said, “You need to get a job … so that you can make sure that you have the finances so that when you go to court you’ll get your custody.” I fell into fear of losing my kids. He has a job and he’s got money, and then his family is rich and my family is middle class, so then that just took me a step back.

(Farah, age 33, United States)

Use of safety strategies (n = 12)

Survivors reported a number of safety strategies to avoid the abuser, protect themselves, or prevent escalation of abuse. The reported strategies included sleeping with a knife under the bed, carrying a phone when alone, locking themselves in a room, and going to sleep at different times than does their abusive partner. Some survivors found it helpful to stay quiet and let their partners do as they wished. By staying quiet they believed they could minimize the arguments and abuse. For instance, one participant stated:

I couldn’t say anything to him. If I said anything back to him it would just escalate things to another level, so I just learned to keep my mouth shut. In order to keep the peace, you just keep your mouth shut, just become a yes person.

(Jasmin, age 37, United States)

One survivor was more proactive about her safety and went to court and got a restraining order. Another survivor intimidated her partner and hit back.

Self-perceived strengths (n = 9)

One survivor believed that financial independence and not caring about one’s image in the South Asian community allowed such participants to break free from abuse, as reflected in the following quote:

I’m very independent financially. I have a really good job, so I’m supporting myself financially, independent of my husband, so that’s definitely one of my biggest strengths. I’ve also stopped caring what people would think of me if I were to get divorced, or the stigma associated with divorce, so I have disassociated divorce from that stigma.

(Malika, age 33, Pakistan)

Laughter, confidence, optimism, and a general sense of happiness were identified as self-perceived strengths. These traits helped women stay mentally strong in the relationship despite the abuse. For example, a survivor shared: “I’m confident. I’m optimistic. Those two will carry you very far when you’re confident and you’re optimistic. I’m very social. That’s a huge strength” (Jasmin, age 37, United States).

Discussion

The South Asian immigrant women in this study experienced multiple forms of abuse. The perpetrators included intimate partners and women’s own family members, as well as their in-laws. Most women experienced all three forms of abuse (i.e., physical, psychological, and sexual), and almost half of them experienced severe physical abuse. Research has shown multiple forms of IPV relate to worse health outcomes, such as posttraumatic stress disorder and depression (Sabri et al., 2016), and extreme negative outcomes, such as injury and death (Sabri, Renner, Stockman, Mittal, & Decker, 2014). Factors involving multiple contexts appeared to have contributed to violence and served as barriers to addressing abuse in women’s lives.

At the macrolevel, normalization of abuse in some situations (e.g., failing to do household chores), arranged marriage system, patriarchal gender norms, and traditional gender role expectations from women, including those who were employed, contributed to abuse. The findings on roles of cultural patriarchal system, arranged marriages, and societal acceptance of IPV are consistent with findings among women in South Asia (Kallivayalil, 2004, 2010; Patel, 2007; Sabri, 2014). The need to protect the family image and the resulting lack of support from family were barriers to leaving the abuser. Women shared that causes of problems in relationships were often attributed to women’s failing to uphold their responsibilities in the relationship, taking the responsibility away from the male abuser.

Religion was discussed as both a risk and protective factor. Whereas some South Asian women identified religion as a barrier that restricted them from leaving their abusive partners, others found it a source of strength in their process of healing and finding safety from the abuser. In many communities in the United States and elsewhere (e.g., Black communities; Gillum, 2009b), religion can serve both as a roadblock by excusing or condoning abusive behavior and as a resource for survivors of violence (Fortune & Enger, 2005). Because religion plays an important role in South Asian communities, it is important to educate religious leaders so that they can participate in community awareness around issues of IPV and find resources to meet the needs of survivors. Faith-based interventions to address IPV have been implemented in other communities such as the African American community. For instance, the Faith-Based Community Domestic Violence Intervention, a four-session intervention, has provided resources to faith-based communities that want to provide education about domestic violence within their churches using a faith-based perspective (Bent-Goodley, 2006). Culturally specific faith-based interventions are needed to address IPV in South Asian communities.

At the macrosystem level, practitioners and policymakers must be aware of the cultural barriers to seeking help by South Asian immigrant women and develop relevant and sensitive outreach services. Education and awareness campaigns could focus on the definitions of IPV, its negative effects, and cultural factors that contribute to IPV in South Asian immigrant communities. Further, education could focus on reducing the stigma of being an IPV survivor.

Lack of compassion or support from police, the courts, and other services in the exosystem were barriers in dealing with the abuser. The federal law states that conviction of an IPV offense may lead an immigrant to being deported (Followill, 2017). This deters many immigrant women from seeking or receiving help (Breiding, Basile, Smith, Black, & Mahendra, 2015). At the exosystem level, policymakers and practitioners must address factors that exacerbate abusive situations and add to the stress for immigrant IPV survivors, such as inadequate resources and lack of cultural sensitivity of the service providers.

Programs must be in place to ensure availability of culturally specific trauma-informed services in the community for survivors. Culturally specific interventions have been found to be effective in addressing IPV among other groups of survivors such as African Americans (Gillum, 2009a). Also important is assuring privacy and confidentiality, because IPV is viewed as negatively impacting the family’s image and survivors might experience negative social outcomes for disclosing abuse. Many new immigrant survivors are not aware of the available resources. Educational material with information about available resources, including contact information and phone numbers, could help survivors who have limited knowledge of services in the community.

Health care providers can play an important role in identifying IPV victims by asking routine screening questions (Waalen, Goodwin, Spitz, Petersen, & Saltzman, 2000). In health care settings, interventions such as screening for IPV, providing a wallet-size referral card, and nurse case management protocol have been shown to significantly lower the risk for future IPV among survivors (McFarlane, Groff, O’Brien, & Watson, 2006). Such interventions could be culturally adapted to meet the needs of South Asian immigrant survivors. Law enforcement and other key providers who come into contact with immigrant IPV survivors must be trained in the dynamics of IPV in immigrant communities; immigration-related stressors or barriers; and how abusers can manipulate the situation for survivors, especially those with language barriers.

In this study, lack of support from informal social networks or inability to access these sources of support were barriers. A participant shared how life can be much worse for a South Asian immigrant woman who leaves her abuser and does not receive help from the community. It is imperative that practitioners working with South Asian survivors of IPV thoroughly assess available social support from the community and its impact on survivors. Also critical is to consider abuse from both partners and family members. Research has shown that South Asian survivors of IPV are more likely to report abuse from in-laws, and in-law abuse has been positively and significantly related to women’s experiences of IPV (Raj, Livramento, Santana, Gupta, & Silverman, 2006).

In this study, some women highlighted protective roles of supportive friends, neighbors, and their own children. Only three survivors reported their own family members as protective resources against IPV. Educating families about the impact of IPV and violence from in-laws and other family members and about the role of contributing factors can prevent violence in South Asian families. Families also need to be educated about the double burden that employed women face when they are required to bear the same family responsibilities as do women who stay at home. Programs that address these traditional gender role expectations in the microsystem without threatening the husband’s position in the family could reduce violence by intimate partners and other family members in South Asian communities.

One study sought to raise awareness of IPV in an Asian Indian community in the Midwest specifically with campaign messages encouraging community members, families, and friends to discuss IPV (Yoshihama, Ramakrishnan, Hammock, & Khaliq, 2012). Campaign messages were communicated in the following ways: at local ethnic grocery stores; through weekly radio announcements; through advertisements in ethnic, cultural, and religious organization publications; and through presence at community events. Such awareness-generation campaigns could be useful for diverse groups of South Asian communities in various regions of the United States.

Perpetrator characteristics (e.g., control and suspicion), mental illness, and childhood abuse experiences were shared as risk factors for escalation of abuse in relationships. These characteristics are in line with research on other groups of IPV survivors (WHO & London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2010). At the individual level, women’s self-blame, rationalization of the situation, and fear of losing children were all barriers to addressing abuse, placing them at risk for further victimization.

Women in this study had been in the United States for different lengths of time and therefore may have been at different levels of acculturation. Acculturation can be both a risk and protective factor. Women who are highly acculturated and exposed to more egalitarian gender norms may not hold traditional gender role beliefs that can place them at risk for IPV (Kalunta-Crumpton, 2017). A high level of acculturation can also protect women from IPV because of their knowledge of the available resources for safety in the United States and how to access them. Most women in our study had a college education and could be more acculturated than were those who were educated till only high school or less. However, they still faced barriers to seeking or receiving help for IPV at multiple levels of the socioecological model.

In our findings, women’s positive qualities (e.g., optimism) and use of safety strategies (e.g., not confronting the abuser) were identified as factors that were protective and helped women deal with their abusive relationships. In a study on resilience and resources among South Asian immigrant survivors of IPV in Canada, transformations in self through self-actualization, keeping busy, exercising their willpower, being concerned for children’s well-being, having supportive family and friends, and altering their social networks by making new friends and reducing the influence of friends who promoted “cultural chauvinism (e.g., a real woman sacrifices one’s self in all circumstances, just or unjust)” were identified as protective factors (Ahmad et al., 2013, p. 1063). It is important to emphasize and strengthen such protective resources when working with South Asian immigrant survivors of IPV. Addressing IPV in South Asian immigrant communities requires strategies at multiple levels of the ecological framework that include increasing public awareness, provision of trauma-informed culturally responsive services, and empowering women to seek help.

The limitation of the study should be acknowledged. The findings of this study represent voices of a small group of immigrant women from selected South Asian countries and therefore may not be generalizable to immigrants from other South Asian countries, such as Afghanistan and Nepal. Despite the limitations, there are some notable strengths. The study includes immigrants from multiple South Asian regions and highlights multilevel risk and protective factors of IPV that must be considered in any efforts to address IPV among South Asian women.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health & Human Development Grant K99HD082350. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Institutes of Health or its affiliates.

Footnotes

To preserve anonymity and confidentiality of the survivors in the study, pseudonyms (Given, 2008) are used to describe survivors’ quotes.

References

- Ahmad F, Rai N, Petrovic B, Erickson PE, Stewart DE. Resilience and resources among South Asian immigrant women as survivors of partner violence. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2013;15:1057–1064. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9836-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed B, Reavey P, Majumdar A. Constructions of “culture” in accounts of South Asian women survivors of sexual violence. Feminism & Psychology. 2009;19:7–28. doi: 10.1177/0959353508098617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bent-Goodley TB. Domestic violence and the Black church: Challenging abuse one soul at a time. Hampton RL, Gullotta TP, Ramos JM, editors. Interpersonal violence in the African-American community: Evidence-based prevention & treatment practices. 2006:107–119. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-29598-5_5. [DOI]

- Bloor M, Frankland J, Thomas M, Robson K. Focus groups in social research. 2001 doi: 10.4135/9781849209175. [DOI]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breiding MJ, Basile KC, Smith SG, Black MC, Mahendra R. Intimate partner violence surveillance uniform definitions and recommended data elements. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/intimatepartnerviolence.pdf.

- Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Chronic disease and health risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violence—18 U.S. states/territories, 2005. Annals of Epidemiology. 2008;18:538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brem MJ, Florimbio AR, Elmquist J, Shorey RC, Stuart GL. Antisocial traits, distress tolerance, and alcohol problems as predictors of intimate partner violence in men arrested for domestic violence. Psychology of Violence. 2018;8:132–139. doi: 10.1037/vio0000088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Intimate partner violence: Consequences. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/consequences.html.

- Dasgupta SD. Gender roles and cultural continuity in the Asian Indian immigrant community in the U.S. Sex Roles. 1998;38:953–974. doi: 10.1023/A:1018822525427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta SD. Charting the course: An overview of domestic violence in the South Asian community in the United States. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless. 2000;9:173–185. doi: 10.1023/A:1009403917198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards VJ, Black MC, Dhingra S, McKnight-Eily L, Perry GS. Physical and sexual intimate partner violence and reported serious psychological distress in the 2007 BRFSS. International Journal of Public Health. 2009;54(Suppl 1):37–42. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finfgeld-Connett D, Johnson ED. Abused South Asian women in Westernized countries and their experiences seeking help. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2013;34:863–873. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2013.833318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Followill P. Domestic violence laws and penalties. 2017 Retrieved from http://www.criminaldefenselawyer.com/legal-encyclopedia/domestic-violence-laws-penalties.html#.

- Fortune M, Enger C. Violence against women and the role of religion. 2005 Retrieved from http://www.ncdsv.org/images/vawnet_vawandtheroleofreligion_3-2005.pdf.

- Gillum TL. Improving services to African American survivors of IPV: From the voices of recipients of culturally specific services. Violence Against Women. 2009a;15:57–80. doi: 10.1177/1077801208328375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum TL. The intersection of spirituality, religion and intimate partner violence in the African American community. 2009b Retrieved from http://www.communitysolutionsva.org/files/TheIntersectionofSpirituality%281%29.pdf.

- Given LM. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. 2008 Retrieved from http://methods.sagepub.com/reference/sage-encyc-qualitative-research-methods/n345.xml.

- Heise LL. Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women. 1998;4:262–290. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise LL, Kotsadam A. Cross-national and multilevel correlates of partner violence: An analysis of data from population-based surveys. Lancet Global Health. 2015;3:e332–e340. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeffel EM, Rastogi S, Kim MO, Shahid H. The Asian population: 2010 Census briefs. 2012 Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-11.pdf.

- Jesmin SS. Married women’s justification of intimate partner violence in Bangladesh: Examining community norm and individual-level risk factors. Violence and Victims. 2015;30:984–1003. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-14-00066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallivayalil D. Gender and cultural socialization in Indian immigrant families in the United States. Feminism & Psychology. 2004;14:535–559. doi: 10.1177/0959353504046871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kallivayalil D. Narratives of suffering of South Asian immigrant survivors of domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2010;16:789–811. doi: 10.1177/1077801210374209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalunta-Crumpton A. Attitudes and solutions toward intimate partner violence: Immigrant Nigerian women speak. Criminology & Criminal Justice. 2017;17:3–21. doi: 10.1177/1748895816655842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakakis S. Mexican immigrant women reaching out: The role of informal networks in the process of seeking help for intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2014;20:1097–1116. doi: 10.1177/1077801214549640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra N. South Asian women in the U.S. and their experience of domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2012;27:381–390. doi: 10.1007/s10896-012-9434-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane JM, Groff JY, O’Brien JA, Watson K. Secondary prevention of intimate partner violence: A randomized controlled trial. Nursing Research. 2006;55:52–61. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mose GB, Gillum TL. Intimate partner violence in African immigrant communities in the United States: Reflections from the ID-VAAC African Women’s Round Table on Domestic Violence. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2016;25:50–62. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2016.1090517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NR. The construction of South-Asian-American womanhood: Implications for counseling and psychotherapy. Women & Therapy. 2007;30(3–4):51–61. doi: 10.1300/J015v30n03_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinnewala P. Good women, martyrs, and survivors: A theoretical framework for South Asian women’s responses to partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2009;15:81–105. doi: 10.1177/1077801208328005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Livramento KN, Santana MC, Gupta J, Silverman JG. Victims of intimate partner violence more likely to report abuse from in-laws. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:936–949. doi: 10.1177/1077801206292935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Silverman JG. Immigrant South Asian women at greater risk for injury from intimate partner violence. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:435–437. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.3.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabri B. Domestic violence among South Asian women: An ecological perspective. In: Taylor MF, Pooley JA, Taylor RS, editors. Overcoming domestic violence: Creating a dialogue around vulnerable populations. New York, NY: Nova Science; 2014. pp. 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Sabri B, Holliday CN, Alexander KA, Huerta J, Cimino A, Callwood GB, Campbell JC. Cumulative violence exposures: Black women’s responses and sources of strength. Social Work in Public Health. 2016;31:127–139. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2015.1087917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabri B, Renner LM, Stockman JK, Mittal M, Decker MR. Risk factors for severe intimate partner violence and violence-related injuries among women in India. Women & Health. 2014;54:281–300. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2014.896445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sam DL, Berry JW. Acculturation: When individuals and groups of different cultural backgrounds meet. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5:472–481. doi: 10.1177/1745691610373075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Córdova D, Mason CA, Huang S, … Szapocznik J. Developmental trajectories of acculturation: Links with family functioning and mental health in recent-immigrant Hispanic adolescents. Child Development. 2015;86:726–748. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65:237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South Asian Americans Leading Together and Asian American Federation. A demographic snapshot of South Asians in the United States: July 2012 update. 2012 Retrieved from http://saalt.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Demographic-Snapshot-Asian-American-Foundation-2012.pdf.

- Waalen J, Goodwin MM, Spitz AM, Petersen R, Saltzman LE. Screening for intimate partner violence by health care providers: Barriers and interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;19:230–237. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil A. Intimate partner violence: Epidemiology and health consequences. 2016 Retrieved from http://www.uptodate.com/contents/intimate-partner-violence-epidemiology-and-health-consequences?source=search_result.

- World Health Organization. Intimate partner violence. 2012 Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/77432/1/WHO_RHR_12.36_eng.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization & London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: Taking action and generating evidence. 2010 doi: 10.1136/ip.2010.029629. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/violence/9789241564007_eng.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yoshihama M, Ramakrishnan A, Hammock AC, Khaliq M. Intimate partner violence prevention program in an Asian immigrant community: Integrating theories, data, and community. Violence Against Women. 2012;18:763–783. doi: 10.1177/1077801212455163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]