Abstract

Study design

This study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of a concentrated PACs compound (36 mg/capsule), in veterans with SCI and neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction (NLUTD) requiring intermittent catheterization (IC) over a 15-day period.

Objectives

The objective of this study was to evaluate the acute effects of concentrated proanthocyanidins (PACs) in the cranberry supplement ellura® on bacteriuria, leukocyturia, and subjective urine quality in catheter-dependent veterans with SCI.

Setting

Spinal cord injury center (outpatient clinic and inpatient unit).

Methods

Participants with positive urine bacterial colonization (≥50 K CFU/ml) were randomized to once daily concentrated PACs or identical placebo and followed with daily (in-patients) or twice weekly (out-patients) urine cultures with colony forming units per milliliter (cfu/ml) range (bacteriuria), microscopic urine white blood cells per high-powered field (wbc/hpf) quantification (leukocyturia), and surveys assessing urine clarity, odor, color, sediment, and overall satisfaction. A repeated measure analysis of variance was used to compare treatment vs. control and evaluate serial trends.

Results

A total of 13 male participants (7 randomized to concentrated PACs, 6 to placebo) completed the trial. There was no significant decrease over the study period in colony forming units per milliliter (cfu/ml) or log(wbc/hpf) in the treatment vs. the control group. Patients receiving concentrated PACs rated the clarity, odor, color, sediment, and overall satisfaction of their urine as insignificantly improved compared to placebo.

Conclusions

Acutely, there was no reduction of bacteriuria and pyuria or improvement in subjective urine quality for SCI patients treated with daily concentrated PACs.

Introduction

Persons with spinal cord injury (SCI) commonly develop neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction (NLUTD). These individuals frequently require intermittent or indwelling urinary catheterization for bladder management. Unfortunately, this practice is associated with high rates of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), which results in a significant morbidity for this patient population. UTIs are the most frequent type of infection seen in this patient population, with an average of 2.5 episodes occurring yearly per patient [1].

Individuals with SCI who utilize intermittent urinary catheterization (IC) typically have varying degrees of bacteriuria and pyuria at baseline. Prophylactic treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria with antibiotics is not recommended due to rapid re-colonization rates and the development of bacterial resistance [2].

Furthermore, the differentiation between asymptomatic bacteriuria and CAUTI requiring antibiotic treatment rather than conservative management is challenging in this population of patients because of a lack of consensus regarding what constitutes CAUTI symptoms. These symptoms are diverse in both type and severity amongst patients with SCI, including fever, rigors, chills, nausea and vomiting, abdominal discomfort, sweating, muscular spasms, fatigue, and autonomic dysreflexia [3]. Typical symptoms of dysuria, urinary frequency, and urinary urgency may not be present [4, 5]. Finally, clinical signs of UTI correlate poorly with urine quantitative colony counts (CFU/ml) and white blood cell count (wbc/hpf), for which there remain no clear thresholds [6]. Therefore, there is a pressing need to identify novel, non-antibiotic agents for the prophylactic reduction of CAUTI rates in individuals with SCI.

Cranberry extract has been shown to decrease uropathogenic Escherichia coli’s ability to adhere to the urothelial lining in a dose-dependent manner, thus preventing colonization of the urinary tract [7, 8]. Cranberry’s biochemical effects on other pathogens have not been characterized, to our knowledge. The cranberry supplement utilized in our study, ellura® (Trophikos, LLC) contains an extract from the American cranberry juice concentrate that is rich in proanthocyanidins (PACs). PACs have been shown to have the highest bioactivity measured compared to any other component of cranberry extract [9]. Each capsule contains precisely 36 mg PAC measured by the BL-DMAC method. This is the daily amount that has been suggested to be effective in urinary tract health. Its highest bioavailability is measured 6–8 h after ingestion. This compound has been validated by the French food security administration, as well as the French drug regulatory administration on several occasions. Botto et al. [10] found that this product had a dramatic effect at reducing asymptomatic bacteriuria in persons with an ileal enterocystoplasty, regardless of organism. However, the duration of the study, was quite long, on average 18.5 months. It is not known what acute effects this product could have on bacterial counts. In addition, it is not known whether any secondary effects, such as reduction in urinary white blood cells, indicative of the degree of bladder inflammation, could occur as well. If decreased bacterial bladder wall adherence can occur with PACs, this could potentially result in reduction of bladder wall inflammation. Finally, although patients frequently report benefits of cranberry usage, there is no data in the literature evaluating effects on patient reported urine quality characteristics.

The objective of this study, therefore, was to determine whether daily administration would result in an acute improvement in baseline bacteriuria, pyuria, and subjective urine quality vs. placebo in individuals with SCI and NLUTD who utilize IC.

Methods

This was a single-institution, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Veterans aged 18–65 with documented SCI in stable condition and NLUTD requiring intermittent urinary catheterization for bladder management were eligible. Both male and female veterans were eligible to participate; however, no female veterans could be recruited. All subjects performed IC at least twice daily. Some used an external catheter in between catheterizations. While we may have preferred some subjects to perform IC more frequently, we did not attempt to change their existing management for the purposes of this study.

The study was approved by the institutional review board at the Hunter Holmes McGuire (Richmond) Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Individuals over 65 years old were not included as previous (unpublished results) in this population showed limited efficacy of PAC prophylaxis. Persons with medical conditions associated with potentially altered immune status (including multiple sclerosis), cognitive impairment precluding informed consent, allergy to cranberry, or ongoing consumption of cranberry products were excluded. All subjects were screened for urolithiasis with renal and bladder ultrasound or computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis as part of their ongoing spinal cord injury care. Any subject found to have urolithiasis was excluded. Exclusion criteria also included any antibiotic therapy, urinary antiseptic supplements, or symptoms of CAUTI (including fevers, chills, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, generalized malaise, new or worsened spasticity, autonomic dysreflexia, or subjective sense of having a UTI) within 2 weeks prior to the start of the trial. Women were eligible for inclusion but would require pregnancy screening, if indicated. Recruits were screened with urine culture to detect at least one dominant bacterial organism growing at least 50,000 colony forming units per milliliter (CFU/ml) (Table 1). Urine cultures were performed prior to the study (screening, as above), at baseline prior to receiving any study medication, and then serially according to the protocol.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Be a Veteran ≥18 and <65 years of age who is an active patient at the McGuire veterans Affairs Hospital SCI Center | Have an immunocompromising condition (HIV, active steroid use, active chemotherapy, etc.) |

| Have a documented SCI >6 months post injury with NLUTD requiring intermittent catheterization | Require chronic antibiotic therapy for other conditions |

| Have a cognitive impairment precluding informed consent | |

| Have a positive urine culture with ≥50–75 K CFU of at least one bacterial agent >7 and ≤14 days of study initiation | Are pregnant or planning to become pregnant |

| Are allergic to cranberries or red fruit | |

| Be >2 weeks status-post antibiotic therapy, urinary antiseptic supplements, or symptomatic UTI at the time of initial screening | Routinely consume foods containing cranberry and are not willing to discontinue during the study |

Using an automated randomization table generator, eligible participants were randomized by one of our research pharmacists, who were not an investigator on the study, to receive either daily concentrated PACs or identical placebo, both provided by the manufacturer. Over a study period of 15 days, those participants who were in-patients at the Hunter Holmes McGuire Veterans Affairs Medical Center received daily assessments, while those who were out-patients received twice weekly assessments in order to facilitate adherence. All urine specimens from both settings were analyzed in a single-microbiology laboratory using the same methods. The same study coordinator collected all specimens and handled all specimens in an identical manner. Assessments consisted of a urine culture (UCx) with CFU/ml and speciation, and urinalysis (UA) with wbc/hpf. Urinary leukocytes were chosen as a surrogate for local inflammation, which can occur in the absence of clinical UTI. A urine quality assessment survey was generated for the purposes of the study. Subjective urine quality is often the sole indicator of UTI in patients with SCI and may be a valuable outcome measurement in this population. The survey evaluated urine clarity, odor, color, sediment, and overall satisfaction using a rating scale of 1–5, with 1 indicating much worse and 5 indicating much improved from baseline (Table 2). Baseline assessments were collected prior to the initiation of the study intervention.

Table 2.

Urine quality assessment survey

| Subject ID # ___________ | Date: ________________ | ||||

| This assessment is to characterize any CHANGE you have noticed in your urine since starting study medication. | |||||

| 1 = much worse | |||||

| 2 = slightly worse | |||||

| 3 = about the same | |||||

| 4 = slightly improved | |||||

| 5 = much improved | |||||

| How would you rate: please circle your choice. | |||||

| 1. The CLARITY of your urine (how clear your urine is)? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2. The ODOR of your urine? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3. The COLOR of your urine? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4. The amount of SEDIMENT (debris) in your urine? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5. Your OVERALL SATISFACTION with your urine? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Participants were censored if they developed a need for antibiotic therapy for any condition, including symptomatic CAUTI, defined as clinical signs and symptoms, bacterial colony count ≥100 × 103 CFU/ml, or urine leukocytosis ≥10 wbc/hpf (white blood cells per high-powered field). The intended primary outcome was to detect a reduction in urine colony count of the dominant bacterial organism by 50%, or 2 “range increments” (see below). Secondary outcomes were the reduction in urine leukocytosis and the improvement of subjective urine quality parameters.

Data were interpreted using a repeated measure analysis of variance to detect a significant difference in the average of each outcome measurement amongst all participants over the 15-day trial period. Significance was set at p = 0.05. Urine bacterial colony count was reported in increments according to ranges used in our microbiology laboratory. These increments were: no growth, 5–10 × 103 cfu/ml, 10–25 × 103 cfu/ml, 25–50 × 103 cfu/ml, 50–75 × 103, 75–100 k, >100 K. These were converted into discrete numbers based on the low end of the range to allow for statistical analysis as categorical variables. Due to its high variability, data for urine leukocytosis were graphed using a logarithmic scale.

Results

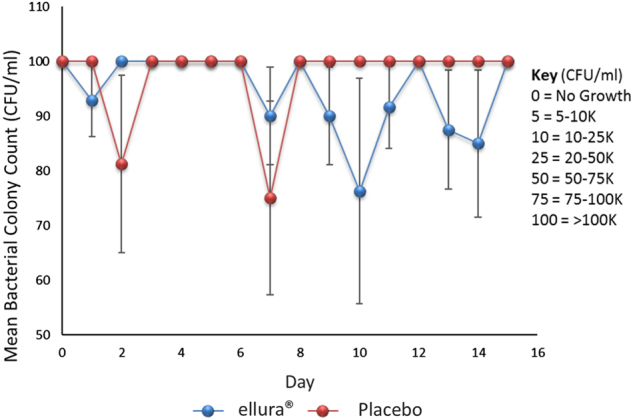

In total, 13 patients, all male, were recruited for the study. Of these, seven patients were randomly assigned to receive concentrated PACs, while six patients were randomly assigned to receive placebo. Subject characteristics are shown in Table 3. Urine culture predominant organisms did not change from screening through the end of the study period. Urine culture results were as follows: E. coli (n = 3), Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 7), Serratia marcescens (n = 1), Enterococcus faecalis (n = 1), and Proteus mirabilis (n = 1), There were no patients censored. There was no significant difference in bacteriuria detectable between the two cohorts over the study period (p = 0.65). The concentrated PACs cohort had an average of 94.26 × 103 ± 2.75 × 103 CFU/ml, while the placebo cohort had an average of 96.20 × 103 ± 3.17 × 103 CFU/ml (Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Patient characteristics

| Subject | Level | Age | Race | AIS | IC type | IC/day | 2nd BMM | UMN/LMN | NDO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | T9 | C | A | Self | 3 | None | EQUIV | Unknown | |

| 02 | T1 | AA | A | Self | 6 | None | UMN | Yes | |

| 03 | C6 | AA | A | Others | 4 | None | UMN | Yes | |

| 04 | C7 | C | A | Others | 2 | None | UMN | Unknown | |

| 05 | C6 | C | A | Others | 4–6 | None | UMN | Yes | |

| 06 | T5 | C | A | Self | 2–3 | None | UMN | Yes | |

| 07 | C5 | C | C | Others | 6 | None | UMN | Yes | |

| 09 | C7 | AA | B | Self | 6 | EC | UMN | Unknown | |

| 011 | T7 | AA | C | Self | 6 | None | UMN | Yes | |

| 012 | T7 | C | A | Self | 6 | None | UMN | Unknown | |

| 013 | C6 | AA | A | Self | 2 | EC | UMN | Unknown | |

| 015 | C7 | C | C | Self | 4 | None | UMN | Unknown | |

| 016 | T11 | AA | A | Self | 4 | None | LMN | No |

AIS American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale, IC intermittent catheterization, BMM bladder management method, UMN upper motor neuron, LMM lower motor neuron, NDO presence of neurogenic detrusor overactivity on urodynamic testing, Equiv equivocal, C Caucasian, AA African American, EC external catheter

Fig. 1.

Mean bacterial colony count. Scatter plot with positive and negative error bars representing mean bacterial colony count for all patients over the 15-day trial period. Key indicates conversion of incremental lab reported values to discrete values for the purposes of statistical analysis

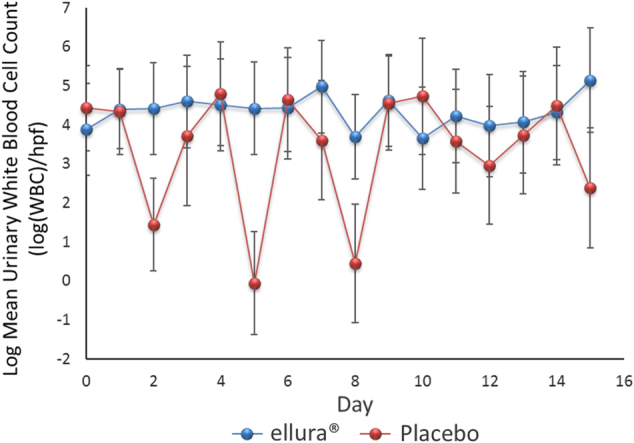

In addition, there was no significant difference in leukocyturia able to be detected between the two cohorts over the study period (p = 0.14). The concentrated PACs cohort had an average of 4.33 ± 0.40 log(wbc)/hpf, while the placebo cohort had an average of 3.36 ± 0.46 log(wbc)/hpf (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Logarithmic form of the mean urinary white blood cell count. Scatter plot with positive and negative error bars representing the mean urinary white blood cell count for all patients over the 15-day trial period. The logarithmic form of the data were used for statistical analysis because of the variability of the data

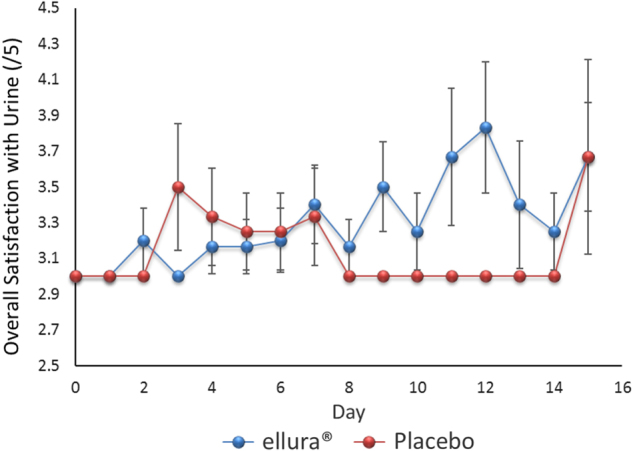

There was no significant difference in reported clarity (p = 0.18), odor (p = 0.09), color (p = 0.33), sediment (p = 0.28), or overall satisfaction (p = 0.27) between the two cohorts over the study period (Table 4). Overall satisfaction was rated on average at 3.27 ± 0.08 in the concentrated PACs cohort and 3.13 ± 0.09 in the placebo cohort (Fig. 3).

Table 4.

Urine quality assessment results

| ellura® | Placebo | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clarity | 3.26 | 3.10 | 0.18 |

| Odor | 3.11 | 3.00 | 0.09 |

| Color | 3.20 | 3.10 | 0.33 |

| Sediment | 3.30 | 3.13 | 0.28 |

Fig. 3.

Overall satisfaction with urine quality. Scatter plot with positive and negative error bars representing the mean rating of overall satisfaction with urine quality for all patients over the 15-day trial period. Rating scale of 1–5 was used, with 1 indicating much worse and 5 indicating much improved from baseline

Discussion

In this study, there was no acute reduction in bacteriuria, leukocyturia, or subjective urine quality in individuals with SCI and NLUTD receiving a concentrated PACS product compared to placebo. This contrasts with the results of Botto et al. described above, and argue for a longer duration of administration. Several trials have been published providing clinical evidence for the benefits of cranberry supplementation in different patient populations [11–13]. Jepson and Craig, in a 2008 Cochrane review, reported that “there is some evidence that cranberry juice may decrease the number of symptomatic CAUTI over a 12-month period, particularly for women with recurrent CAUTI. Its effectiveness for other groups is less certain [14].”

Although, there have been studies published evaluating the effectiveness of cranberry prophylaxis in patients with SCI, none have utilized a standardized, high-potency cranberry supplement. The results from these investigations have been inconsistent. Lee et al. [15] found no benefit of a cranberry supplement in incidence of CAUTI in persons with SCI in a 2-year study. Bladder management of participants included indwelling, intermittent, or reflex voiding with or without external/condom catheter use. Hess et al.[16] reported benefits in reduction of CAUTI in 47 patients with SCI for any given month while on cranberry over a 6-month period, but 75% of this group used condom catheters as their primary method of bladder management, making results difficult to interpret. Linsenmeyer et al. [17] found no difference in bacterial or leukocyte counts for patients with SCI randomized to cranberry supplementation in a 4-week study.

Although this study, in its present form, did not demonstrate any acute effects of 36 mg daily PAC treatment in this very-specific population, the original trial design required the recruitment of at least 24 participants to be powered to detect a 50% reduction in bacteriuria. However, this study had to be prematurely terminated after interim data analysis, conducted due to difficulties with recruitment and funding, showed no significant trends for any outcome measurements. Therefore, the study was under-powered to detect the primary outcome. Due to the limited funding provided for this study, we chose bacteriuria and leukocyturia as outcome measures. Changes in the parameters could potentially have been noticed within a few days, as might be seen with antimicrobial agents. Despite the limited number of subjects, serial assessments on each subject resulted in at least 65 data points per parameter. Had we chosen symptomatic CAUTI as our outcome measure, we would have needed far more time, subjects and funding.

Additionally, the reporting of bacterial colony counts by our facility’s microbiology laboratory in defined ranges, rather than absolute colony counts, may have limited the precision of the data collected to evaluate bacteriuria. Even though the study was open to men and women, only men participated, likely due to the predominance of male gender in the Veterans Affairs Health system, which is even higher than in the nonveteran population of persons with SCI.

Our study found no difference in urine quality parameters such as color, odor, clarity, sediment, or overall satisfaction. We created this survey for the purposes of the study, as we found nothing similar in the literature. Our rationale for use of a urine quality assessment is that patients often report benefit from use of cranberry products that might not otherwise be detected. Adding this type of patient-reported outcomes have not been frequently used in past studies but are being suggested with increasing frequency. We hope to perform validation of this survey using a large local sample of catheter-dependent persons with SCI.

Although there is evidence that PACs decrease bacterial adherence to the urothelial lining [7], this prospective study was unable to demonstrate a clinically significant benefit in patients with SCI and NLUTD. Despite being unable to report any positive results, the authors believe that it is important to share these findings to prevent repetition and to inform future studies. As the compound under study is available for purchase online without a prescription, clinicians should be aware of the status of evidence for its use. The next prospective study of PAC for the reduction of bacteriuria in patients with SCI and NLUTD should consider an increase the sample size, consider modifying the design to include more frequent (twice daily or more often) dosing, and allow for a longer period of administration. A study with clinical CAUTI, rather than simply leukocyturia or bacteriuria, as the primary outcome measure would require greater time and resources. A recent meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of clinical trials. [18] Supports the use of cranberry products to reduce the incidence of UTI. However, different populations might respond differently to these products, and persons with SCI, due to frequent heavy colonization, might require higher doses, or may not respond regardless of dose. Finally, a longer intervention period may be needed to reduce the likelihood of not finding an effect should one actually exist, i.e., a type II error.

We consider our study to be a preliminary investigation. If we had desired to start each patient with “clean” urine (i.e., with a negative urine culture) in these persons with chronic bladder colonization, we would have had to give a course of antimicrobials. Doing this would have been difficult to justify to an investigative review board, especially given that our subjects had asymptomatic bacteriuria, which is generally not treated. We excluded subjects with active clinical UTI.

The question of existing bacteriuria, and likely some degree of biofilm, is an important one. It is not known if cranberry could have an effect in reducing bacteriuria or bladder biofilm. We felt our study was novel in this regard, the study had the possibility of demonstrating something novel.

The study by Botto et al. [10] mentioned above was similar to ours in that it looked at bacteriuria as an endpoint and used the same product. They used a longer duration of treatment which may be necessary to demonstrate reduction in bacteriuria and/or leukocyturia in persons with SCI who are chronically colonized.

Conclusion

This prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the standardized PAC supplement ellura® in veterans with SCI and NLUTD was unable to detect a significant improvement in bacteriuria, leukocyturia, or subjective urine quality assessment in the acute setting. The study was prematurely terminated and under-powered to detect the primary outcome. It is important to report this negative study to inform further studies. Future considerations include a larger sample size, more consistent outcome assessments, more frequent dosing, and a longer study period.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was funded in part by the Trophikos, LLC, the manufacturer of the cranberry supplement, ellura®.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Siroky MB. Pathogenesis of bacteriuria and infection in the spinal cord injured patient. Am J Med. 2002;113:67S–79S. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, Colgan R, Geerlings SE, Rice JC, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:625–63. doi: 10.1086/650482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goetz LL, Cardenas DD, Kennelly M, Bonne Lee BS, Linsenmeyer T, Moser C, et al. International spinal cord injury urinary tract infection basic data set. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:700–4. doi: 10.1038/sc.2013.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linsenmeyer TA, Oakley A. Accuracy of individuals with spinal cord injury at predicting urinary tract infections based on their symptoms. J Spinal Cord Med. 2003;26:352–7. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2003.11753705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massa LM, Hoffman JM, Cardenas DD. Validity, accuracy, and predictive value of urinary tract infection signs and symptoms in individuals with spinal cord injury on intermittent catheterization. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32:568–73. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2009.11754562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ronco E, Denys P, Bernède-Bauduin C, Laffont I, Martel P, Salomon J, et al. Diagnostic criteria of urinary tract infection in male patients with spinal cord injury. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25:351–8. doi: 10.1177/1545968310383432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavigne JP, Bourg G, Combescure C, Botto H, Sotto A. In-vitro and in-vivo evidence of dose-dependent decrease of uropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence after consumption of commercial Vaccinium macrocarpon (cranberry) capsules. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:350–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howell AB, Botto H, Combescure C, Blanc-Potard AB, Gausa L, Matsumoto T, et al. Dosage effect on uropathogenic Escherichia coli anti-adhesion activity in urine following consumption of cranberry powder standardized for proanthocyanidin content: a multicentric randomized double blind study. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White BL, Howard LR, Prior RL. Release of bound procyanidins from cranberry pomace by alkaline hydrolysis. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:7572–9. doi: 10.1021/jf100700p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Botto H, Neuzillet Y. Effectiveness of a cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) preparation in reducing asymptomatic bacteriuria in patients with an ileal enterocystoplasty. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2010;44:165–8. doi: 10.3109/00365591003636596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beerepoot MAJ, ter Riet G, Nys S, van der Wal WM, de Borgie CAJM, de Reijke TM, et al. Cranberries vs antibiotics to prevent urinary tract infections: a randomized double-blind noninferiority trial in premenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1270–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stothers L. A randomized trial to evaluate effectiveness and cost effectiveness of naturopathic cranberry products as prophylaxis against urinary tract infection in women. Can J Urol. 2002;9:1558–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wing DA, Rumney PJ, Preslicka CW, Chung JH. Daily cranberry juice for the prevention of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy: a randomized, controlled pilot study. J Urol. 2008;180:1367–72. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jepson RG, Williams G, Craig JC. Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD001321. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001321.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee BB, Haran MJ, Hunt LM, Simpson JM, Marial O, Rutkowski SB, et al. Spinal-injured neuropathic bladder antisepsis (SINBA) trial. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:542–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hess MJ, Hess PE, Sullivan MR, Nee M, Yalla SV. Evaluation of cranberry tablets for the prevention of urinary tract infections in spinal cord injured patients with neurogenic bladder. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:622–6. doi: 10.1038/sc.2008.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linsenmeyer TA, Harrison B, Oakley A, Kirshblum S, Stock JA, Millis SR. Evaluation of cranberry supplement for reduction of urinary tract infections in individuals with neurogenic bladders secondary to spinal cord injury. A prospective, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, crossover study. J Spinal Cord Med. 2004;27:29–34. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2004.11753727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luís Asystematicreviewwithmetaanalysisandtrialsequentialanalysisofc. J Urol. 2017;198:614–21. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]