The use of intraoperative surgical navigation has improved the safety and efficacy of select sinus operations1 and has facilitated the expansion of endoscopic skull base approaches.2 Transoral surgery (TOS) has revolutionized management of tumors of the pharynx and larynx.3 Intraoperative surgical navigation may play a role in assessing tumor extent and avoidance of critical structures in TOS but has not been studied. Unlike the case with imaging acquired for sinus and skull base surgery, the upper aerodigestive tract anatomy changes once the patient undergoes general anesthesia and during suspension laryngoscopy, thus rendering preoperative imaging unusable. With the availability of intraoperative computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at an increasing number of medical centers, investigating the application of this technology for TOS is feasible. However, one challenge is that TOS instrumentation is made of stainless steel and is contraindicated in MRI and creates significant artifact on CT. In this report, we present a 3-dimensional (3D) printed laryngoscope made of biocompatible polymer that is compatible with both CT and MRI.

Methods

This report is part of a larger study examining airway deformation during laryngoscopy through intraoperative imaging and was approved by the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center Institutional Review Board. An adult Lindholm operating laryngoscope (8587A; KARL STORZ GmbH & Co KG, Tuttlingen, Germany) was rendered via SolidWorks CAD software (Dassault Systèmes SolidWorks Corporation, Waltham, Massachusetts). This rendering was printed on a Stratasys Objet Eden250 3D printer (Stratasys Ltd, Eden Prairie, Minnesota) with MED610 (Stratasys Ltd): a biocompatible photopolymer that meets ISO 1099301:2009 standards for biological evaluation of medical devices. It is approved for temporary contact with mucosal surfaces and is used for orthodontics, dental trays, denture try-ins, and surgical guides.4 Each scope was printed and processed via the biocompatibility protocol specified by the printer manufacturer.4 Mechanical load tests simulating intraoperative conditions were performed to evaluate device robustness. A CO2 laser (Ultra MD MD40; Laser Engineering Inc, Nashville, Tennessee) with a 125-mm hand piece was used to test the scope for flammability under room air conditions (21% oxygen) with laser energy delivered in ‘‘super pulse’’ mode (30–1000 pulses per second, depending on the power setting). A platform constructed of Plexiglas and PVC tubing was used to keep the scope in suspension.

A new scope was printed for each case and was sterilized with high-level disinfectant (Revital-Ox; Steris Corporation, Mentor, Ohio) or low-temperature sterilization (STERRAD; Advanced Sterilization Products, Irvine, California). Operations were performed at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Center for Surgical Innovation, which provides both intraoperative CT and MRI capabilities. After induction of general anesthesia and once the polymer laryngoscope was inserted and suspended, intraoperative imaging was performed. A comparison laryngoscopy without imaging was then performed with a standard Lindholm laryngoscope.

Results

The initial scope was designed to match the outer dimensions of the Lindholm. The walls of the scope were made thicker, and material (fillet) was added to the area between the scope handle and blade. Load testing of the initial prototype to 88 N demonstrated no evidence of failure. The final design was further loaded to 180 N, again without catastrophic failure. Plastic deformation (but no fracture) occurred only beyond 150 N. Russel et al report an average force of 5 to 11 N with a maximum of 41 N during laryngoscopy for intubation.5 Flammability testing with the CO2 laser demonstrated no combustion at 8 W applied over 20 seconds or 15 W applied over 15 seconds.

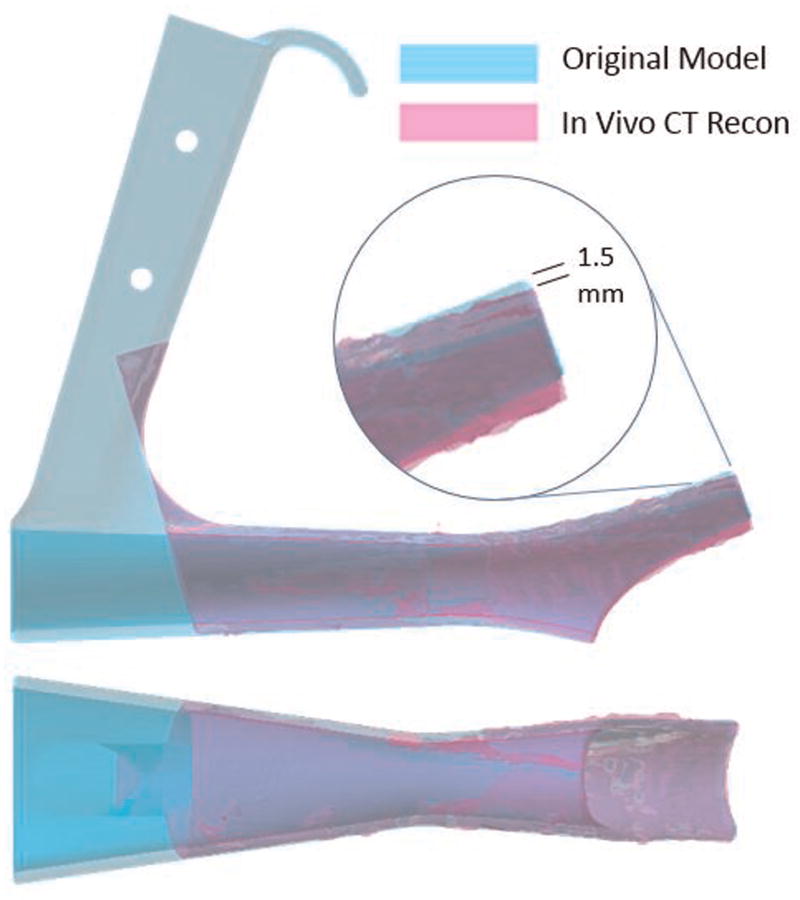

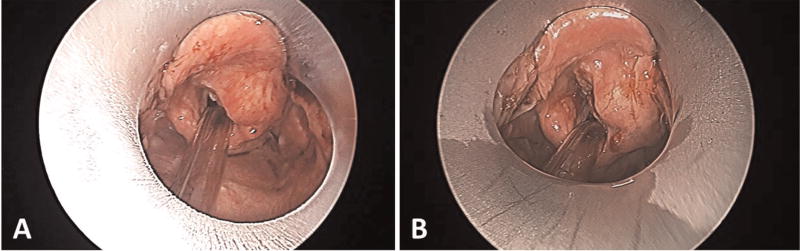

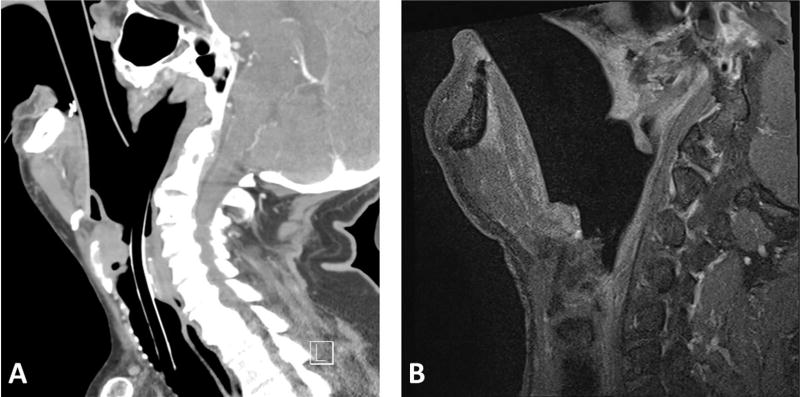

Nine patients scheduled to undergo diagnostic laryngoscopy were enrolled. Eight underwent intraoperative CT, and 1 underwent intraoperative MRI. There were no complications associated with use of the polymer laryngoscope. The scope underwent additional design modifications based on our experience with the first 2 cases, resulting in a longer scope with a wider lumen and reinforced lip (final design, Figure 1). Although distortion of the scope could not be visibly appreciated, slight distortion (maximum, 1.5 mm) of the lip of the scope was identified (Figure 2) by overlaying the in vivo 3D CT reconstruction during suspension laryngoscopy with the original design. During load testing, we observed that for loads <150 N, tip deflection was linearly proportional to the applied force at 0.083 mm/N and would account for this slight distortion. This did not affect visualization when compared with the Lindholm operating laryngoscope (Figure 3). The scope did not create any imaging artifact or distortion on CT or MRI (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Four views of the 3-dimensional printed MED610 polymer laryngoscope as compared with a standard adult Lindholm operating laryngoscope. Note the reinforcement of the handle as well as the thicker lip of the polymer scope.

Figure 2.

The original model with the in vivo computed tomography (CT) reconstruction superimposed. A slight deflection of the lip of the in vivo reconstruction (maximum, 1.5 mm) is noted. This deflection could not be appreciated during the endoscopy.

Figure 3.

View of a supraglottic carcinoma through (A) the polymer laryngoscope and (B) the standard Lindholm operating laryngoscope.

Figure 4.

Intraoperative sagittal (A) computed tomography and (B) magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating the scope in place during suspension laryngoscopy. Note the lack of artifact and image distortion.

Discussion

To study the feasibility of intraoperative surgical navigation for TOS, laryngoscopes that are MRI and CT compatible are necessary but currently do not exist. We have been able to 3D print a laryngoscope made of biocompatible polymer that fulfills these imaging requirements and demonstrate its safe and effective use during operative laryngoscopy. Preclinical load testing demonstrated that the scope easily withstands the normal forces that occur during laryngoscopy. It did not combust during preliminary flammability testing. Although the walls of the laryngoscope had to be reinforced, this did not impair our ability to perform laryngoscopy, nor did it impede visualization. Minimal distortion of the lip of the scope was identified; however, this did not affect exposure.

The ability to 3D print laryngoscopes that can effectively be used during operative laryngoscopy not only has significant benefits in advancing the study of image guidance in TOS but also opens up the very exciting possibilities of personalized laryngoscopes and other instrumentation specific to the patient’s anatomy and pathology.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorships: None.

Funding source: Research reported in this publication was supported by the Dartmouth SYNERGY Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UL1TR001086) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Joseph A. Paydarfar, design of study, design of scope, acquisition of data, drafting manuscript, final approval of version of manuscript to be published; Xiaotian Wu, acquisition and analysis of data, design of scope, critical revisions to manuscript, final approval of version to be published; Ryan J. Halter, design of study, analysis of data, critical revision of manuscript, final approval of version to be published.

Disclosures

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Citardi MJ, Batra PS. Intraoperative surgical navigation for endoscopic sinus surgery: rationale and indications. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;15:23–27. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3280123130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farag A, Rosen M, Evans J. Surgical techniques for sinonasal malignancies. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2015;26:403–412. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holsinger FC, Sweeney AD, Jantharapattana K, et al. The emergence of endoscopic head and neck surgery. Curr Oncol Rep. 2010;12:216–222. doi: 10.1007/s11912-010-0097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stratasys. [Accessed March 10, 2016];PolyJet photopolymers dental and bio-compatible materials spec sheets and SDS. http://www.stratasys.com/materials/material-safety-data-sheets/polyjet/dental-and-bio-compatible-materials.

- 5.Russell T, Khan S, Elman J, Katznelson R, Cooper RM. Measurement of forces applied during Macintosh direct laryngoscopy compared with GlideScope® videolaryngoscopy. Anaesthesia. 2012;67:626–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2012.07087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]