Abstract

The caspase-activated DNase CAD (DFF40/CPAN) degrades chromosomal DNA during apoptosis. Chemical modification with DEPC inactivates the enzyme, suggesting that histidine residues play a decisive role in the catalytic mechanism of this nuclease. Sequence alignment of murine CAD with four homologous apoptotic nucleases reveals four completely (His242, His263, His304 and His308) and two partially (His127 and His313) conserved histidine residues in the catalytic domain of the enzyme. We have changed these residues to asparagine and characterised the variant enzymes with respect to their DNA cleavage activity, structural integrity and oligomeric state. All variants show a decrease in activity compared to the wild-type nuclease as measured by a plasmid DNA cleavage assay. H242N, H263N and H313N exhibit DNA cleavage activities below 5% and H308N displays a drastically altered DNA cleavage pattern compared to wild-type CAD. Whereas all variants but one have the same secondary structure composition and oligomeric state, H242N does not, suggesting that His242 has an important structural role. On the basis of these results, possible roles for His127, His263, His304, His308 and His313 in DNA binding and cleavage are discussed for murine CAD.

INTRODUCTION

The caspase-activated DNase CAD (syn. DFF40/CPAN, DNA fragmentation factor 40 kDa subunit/caspase-activated nuclease) and the inhibitory protein and specific chaperone ICAD-L (inhibitor of CAD large form) (syn. DFF45, DNA fragmentation factor 45 kDa subunit) together form a heterodimeric complex known as the DNA fragmentation factor or DFF (1–3). This complex is involved in chromatin condensation and degradation of chromosomal DNA during apoptosis (4,5). In the course of programmed cell death CAD is released from the DFF complex by proteolytic cleavage of the ICAD-L subunit by caspase 3 or caspase 7, which induces oligomerisation of the free nuclease, leading to an active enzyme capable of cleaving chromosomal DNA into nucleosomal units (1,2,6,7). The nucleolytic activity of CAD has been shown to be activated by direct binding of histone H1 and it is also stimulated by chromatin-associated proteins, e.g. HMG1 and HMG2, a finding which suggests that CAD is directed to its physiological target with the help of these proteins (7,8). Interestingly, CAD also binds to topoisomerase IIα, pointing to a functional link of these two proteins in chromatin condensation during programmed cell death (9).

On the basis of a deletion analysis of CAD it has been concluded that the nuclease is composed of a C-terminal catalytic domain and an N-terminal regulatory domain, confirming the results of a primary structure analysis of CAD and ICAD-L which had revealed significant sequence homology of the N-terminal parts of both proteins with those of the hitherto unknown CIDE proteins (cell death-inducing DFF-like effectors) (10,11). Structural and mutational analyses of these ‘CIDE-N’ or ‘CAD domains’ demonstrated that they account for the ability of CAD and ICAD-L to form a heterodimeric complex, which is a prerequisite for the generation of a properly folded and catalytically competent nuclease (12–15).

In spite of its importance as the cell autonomous DNA degrading enzyme of apoptotic cells, very little is known as yet about the mechanism of DNA hydrolysis by CAD. In order to identify amino acid residues essential for the catalytic activity of the apoptotic nuclease, we started a mutational analysis of murine CAD based on the results of a chemical modification study of wild-type CAD with the histidine-specific reagent diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) which showed that histidine residues are essential for CAD activity. Six conserved histidine residues in CAD were identified using sequence information of homologous apoptotic nucleases from five different organisms, including mouse, rat, human, zebrafish and fruitfly (see Fig. 1). In the present study we have exchanged four completely and two partially conserved histidine residues of murine CAD for asparagine by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis of the murine CAD gene and characterised the variants as GST fusion proteins expressed in Escherichia coli with respect to their DNA cleavage activity and biochemical properties. On the basis of our results, possible roles of the critical histidine residues in the mechanism of DNA cleavage by CAD are discussed.

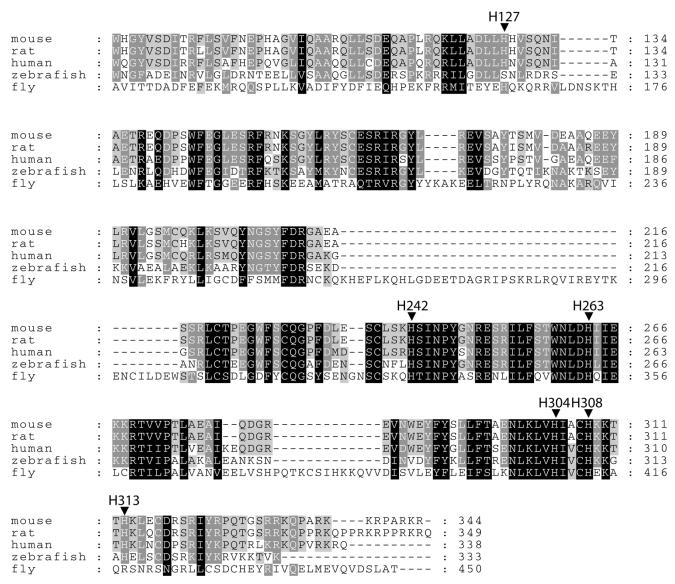

Figure 1.

Conserved histidine residues in the sequences of the apoptotic nuclease CAD from five different organisms. Alignment of the C-terminal region (amino acid residues 81–344 of murine CAD) of mouse (Mus musculus, GenBank accession nos AB009377, NM_007859), rat (Rattus norvegicus, GenBank accession no. AF136598), human (Homo sapiens, GenBank accession nos AF064019, AF039210, AB013918, NM_004402), zebrafish (Danio rerio, GenBank accession no. AF286179) and fruitfly (Drosophila melanogaster, GenBank accession nos AF149797, AB036773) CADs is shown. Completely conserved residues are shaded in black, partially conserved residues are in grey (dark grey corresponds to 80% identity and light grey to 60% identity, with amino acid residues of similar groups considered identical). The conserved histidine residues which were substituted by asparagine in the mutational analyses described here are indicated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

cDNA cloning

To isolate the cDNA for murine CAD (mCAD), total RNA was extracted from NIH 3T3 cells with a RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and used for first-strand cDNA synthesis and subsequent amplification of the mCAD gene with the SuperScript One-Step RT–PCR system (Life Technologies). The open reading frame for mCAD was inserted in-frame into the NcoI and NotI sites of pTriEx1 (Novagen) such that a coding region for an N-terminal His6 tag was produced at the 5′-end of the mCAD gene, resulting in plasmid pHis-mCAD. To isolate the cDNA for human ICAD-L/DFF45 (hICAD-L), total RNA was extracted from HeLa cells with a RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and used for first-strand cDNA synthesis and subsequent amplification of the hICAD-L gene with the Access RT–PCR system (Promega). The coding region for hICAD-L (DFF45) was inserted in-frame as an NcoI–SalI fragment into the NcoI and XhoI sites of the bacterial expression vector pET15b (Novagen). Hamster caspase 3 cDNA was a kind gift of Dr X. Wang (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Dallas, TX).

Bacterial expression of the mCAD–hICAD-L complex

For expression of the mCAD–hICAD-L complex a two plasmid system was used. The T7 promoter/terminator expression cassette including the hICAD-L (DFF45) coding region was excised from pET15b and cloned into the SphI and HindIII sites of the pACYC184 derivative pMQ393, providing chloramphenicol resistance and the pA15 origin of replication, giving plasmid pACET-DFF45. The mCAD open reading frame was amplified by PCR and inserted as a BglII–EcoRI fragment into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pGEX-2T (Pharmacia). Escherichia coli BL21Gold(DE3) cells were consecutively transformed with plasmids pACET-DFF45, coding for wild-type hICAD-L, and pGEX-2T, coding for wild-type GST–mCAD or the mutant versions, respectively. Cells were cultured in 500 ml of LB broth at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.5. Induction was achieved by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 1 mM and culturing cells at 28°C overnight. The bacterial pellet was washed with 1× STE (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA), resuspended in 10 ml buffer A (20 mM HEPES–HCl, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 10% glycerol and 0.01% Triton X-100 and lysed by sonication. After centrifugation the supernatant was applied to 1 ml of a suspension of glutathione–Sepharose 4B resin and bound protein was washed twice with 14 ml of the buffer described above. Then the beads were resuspended in 1 ml of buffer A supplemented with 10 mM DTT, 10% glycerol and 0.01% CHAPS. To store the GST–mCAD–hICAD-L complex, glycerol to a final concentration of 25% was added and the protein bound to the beads was kept at –20°C.

Expression of recombinant caspase 3

For bacterial expression truncated caspase 3 cDNA (16), devoid of the coding region for amino acid residues 1–28, was inserted into the NdeI and BamHI sites of the vector pBB (a derivative of pET3d) such that a coding region for an N-terminal His6 tag was fused to the truncated caspase 3 open reading frame. Recombinant caspase 3 was expressed in BL21(DE3)(pLysS) cells similarly to as described above for the GST–mCAD–hICAD-L complex. To purify the recombinant enzyme, the bacterial pellet was washed with 1× STE (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA), resuspended in 20 ml buffer B (20 mM HEPES–HCl, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.01% CHAPS) and lysed by sonication. After centrifugation the supernatant was applied to 1 ml of a Ni2+–NTA resin. Bound caspase 3 was washed with 20 ml of buffer B containing 20 mM imidazole and then with buffer B containing 500 mM NaCl. Elution was performed using buffer B supplemented with 200 mM imidazole and the eluted caspase 3 was dialysed against buffer B containing 10 mM DTT and 10% glycerol.

Preparation of free GST–mCAD

GST–mCAD–hICAD-L complex bound to glutathione–Sepharose 4B beads was incubated with a 10 µl per ml beads suspension of recombinant caspase 3 for 60 min at 37°C. Subsequently, the beads were washed twice using 1 ml buffer A supplemented with 5 mM DTT, 10% glycerol and 0.01% Triton X-100. Elution of the free nuclease was performed using buffer A supplemented with 10 mM DTT, 0.01% Triton X-100 and 20 mM reduced glutathione. To store the eluted free nuclease, glycerol was added to a final concentration of 20% and the GST–mCAD solution was kept at –20°C.

Chemical modification of wild-type GST–mCAD

For chemical modification GST–mCAD was dialysed against buffer C (50 mM Na-phosphate, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 1 mM DTT). Chemical modification of GST–mCAD by DEPC was performed using a 0.05 or 0.1 mM final concentration of freshly diluted DEPC in a buffer consisting of 10 mM MES–HCl, pH 6.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol and 0.01% CHAPS in the absence or presence of 120 ng/µl plasmid DNA (pBSK-VDEX; New England Biolabs). To analyse the residual activity of DEPC-modified GST–mCAD, aliquots of the modification reaction mix were transferred to buffer D (12 mM MES–HCl, pH 6.8, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, 0.01% CHAPS and 5 mM MgCl2) after defined time intervals and, in the case of modification in the absence of DNA, supplemented with plasmid pBSK-VDEX as substrate. This reaction mix was then incubated for 10 min at 37°C and the cleavage products were analysed on a 0.8% TBE (100 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.3, 100 mM borate, 2.5 mM EDTA)–agarose gel containing 0.05 µg/ml ethidium bromide. In initial experiments the DEPC modification reaction was quenched with 10 mM (final concentration) imidazole to inactivate DEPC before the DNA cleavage assay was carried out. However, this proved to be unnecessary, as the plasmid DNA substrate in the cleavage reaction mix protected the enzyme from further modifiation (see below).

In vitro mutagenesis of the murine CAD gene

In vitro mutagenesis of GST–mCAD was performed as described by Kirsch and Joly (17). In brief, a first PCR was performed using a mutagenic primer and an appropriate reverse primer with pGEX-2T-mCAD as template and Pfu DNA polymerase. Then a second PCR was performed using the purified product from the first reaction as megaprimer for an inverse PCR following the recommendations of the QuikChange protocol (Stratagene).

Size exclusion chromatography with GST–mCAD variants

Size exclusion chromatography with GST–mCAD and its variants was performed on a Superdex-200 HR 10/30 gel filtration column (bed dimensions 10 × 300 mm) equilibrated with 20 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 200 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA and 2.5 mM MgCl2 using a Merck-Hitachi HPLC system. Aliquots of 15 µg of each variant were loaded onto the column in a volume of 100 µl and fractions of 1 ml were collected at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Aliquots of 700 µl were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (10% final concentration) and subjected to SDS–PAGE. Protein bands were visualised by silver staining of the gel. Aliquots of 15 µl of the fractions were incubated in buffer D for 1 h at 37°C with 20 ng/µl plasmid DNA (pBSK-VDEX). Cleavage products were analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis as described above.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of purified GST–mCAD variants

CD spectra of GST–mCAD were recorded on a Jasco J-710 dichrograph between 250 and 185 nm at 16°C in a cylindrical cuvette of 0.05 cm path length. GST–mCAD spectra were recorded at a protein concentration of 1.5 µM in buffer C. Concentrations of the proteins were determined by UV spectroscopy before recording the CD spectra using the method of Pace et al. (18).

In vitro GST–mCAD activity assays

For the in vitro CAD activity assay, free GST–mCAD was dialysed against buffer A supplemented with 5 mM DTT, 10% glycerol and 0.01% CHAPS. Aliquots of dialysed GST–mCAD were incubated in buffer D for defined time intervals at 37°C, using 25 ng/µl plasmid DNA (pBSK-VDEX). Cleavage products were analysed on a 0.8% TBE–agarose gel containing 0.05 µg/ml ethidium bromide.

RESULTS

Comparison of the protein sequence of CAD from five different species

In order to identify target residues for a mutational analysis of the putative active site of the apoptotic nuclease we have compared the primary structure of five related CAD proteins from different organisms, including mouse, rat, human, zebrafish and fruitfly (Fig. 1). As can be seen from the sequence alignment in Figure 1, six histidine residues out of ten in murine CAD, corresponding to His127, His242, His263, His304, His308 and His313, are completely or partially conserved in all five apoptotic nucleases. Since histidines are often involved in the mechanism of catalysis of nucleases (for reviews see 19,20) we decided to investigate, by chemical modification with DEPC, whether the nucleolytic activity of the apoptotic nuclease is affected by this histidine-specific reagent or not. The experiments to be described were carried out with recombinant GST-tagged murine CAD and human ICAD-L because murine CAD can be expressed at much higher yield in E.coli than its human homologue. Nevertheless, we could show that human CAD (DFF40), like murine CAD, is inhibited by DEPC and trinitrobenzenesulfonate (TNBS), suggesting that histidine and/or lysine residues are essential for phosphodiester bond cleavage by the human and murine apoptotic nuclease (S.R.Scholz and G.Meiss, unpublished results).

Preparation of free GST–mCAD

To obtain free and active GST–mCAD, we expressed the GST–mCAD–hICAD-L complex in E.coli as described in Materials and Methods and incubated the purified complex bound to glutathione–Sepharose beads with caspase 3. After caspase 3 treatment, bound GST–mCAD was washed and subsequently eluted from the Sepharose beads, resulting in a >95% pure protein preparation, as judged by SDS–PAGE analysis (see Fig. 4A).

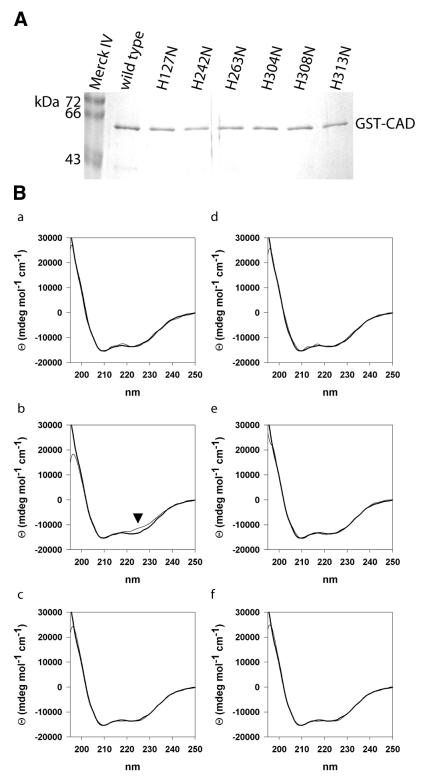

Figure 4.

(A) Preparation of variants of murine CAD with substitution of conserved histidine residues. Mutant forms of GST–mCAD with substitutions of conserved histidine residues in the C-terminal catalytic domain were expressed and purified as described in Materials and Methods. Analysis by SDS–PAGE shows the Merck IV protein standard in the outer left lane as well as wild-type GST–mCAD and variants H127N, H242N, H263N, H304N, H308N and H313N as indicated. (B) CD spectra of GST–mCAD variants. In order to verify that free activated wild-type GST–mCAD and the mutant forms retain their structural integrity, we recorded CD spectra of these proteins in a buffer consisting of 50 mM Na-phosphate, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT and 0.01% CHAPS. Whereas all but one variant show similiar CD spectra indistinguishable from the wild-type GST–mCAD spectrum, H242N produces a slightly but significantly different CD spectrum (marked by an arrow). The CD spectra of the variants (thin line) are superimposed on the spectrum of wild-type GST–mCAD (thick line). (a) H127N; (b) H242N; (c) H263N; (d) H304N; (e) H308N; (f) H313N.

Chemical modification of a GST fusion protein of murine CAD by DEPC

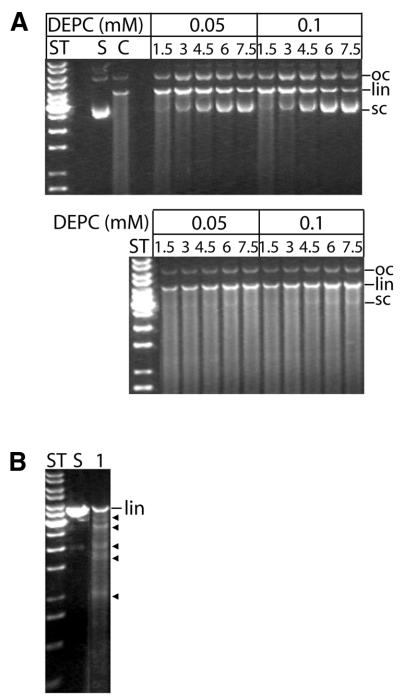

In order to determine whether histidine residues are involved in the hydrolysis of phosphodiester bonds catalysed by mCAD, we incubated wild-type GST–mCAD (free of hICAD-L) with varying amounts of DEPC in the absence and presence of plasmid DNA for different time intervals as indicated in Figure 2. Then the residual catalytic activity of the chemically modified nuclease was measured by cleavage of plasmid DNA for 10 min. As can be seen from Figure 2, DEPC inactivates GST–mCAD in a concentration- and time-dependent manner, indicating that histidine residues play a decisive role in the mechanism of DNA hydrolysis by the apoptotic nuclease (Fig. 2A). In order to see whether the DNA substrate protects the nuclease from inactivation by DEPC, we modified GST–mCAD with DEPC in the presence of plasmid DNA but in the absence of Mg2+, to prevent enzymatic turnover. In this case the rate of inactivation of GST–mCAD by DEPC was ∼10-fold slower (Fig. 2B), indicating that the substrate protects those histidine residues of GST–mCAD, which are involved in catalysis and sensitive to modification by DEPC from being chemically modified. A close inspection of the reaction products obtained by cleavage of DNA with DEPC-treated GST–mCAD showed that, in addition to non-specific cleavage products, defined fragments could also be observed upon prolonged hydrolysis of the DNA (Fig. 2B). This phenomenon was also, but much more clearly, observed with the H308N variant of GST–mCAD (see below Fig. 8). The results of the chemical modification experiments prompted us to generate mutant versions of murine CAD with substitutions of all conserved histidine residues in the catalytic domain of the enzyme and to investigate whether and to what extent they are inactivated by the amino acid change.

Figure 2.

Chemical modification of GST–mCAD with DEPC. Chemical modification of free GST–mCAD with DEPC was carried out in the absence and presence of 120 ng/µl substrate DNA. The modification mix was incubated with a 0.05 or 0.1 mM final concentration of freshly diluted DEPC for 1.5, 3, 4.5, 6 and 7.5 min. Aliquots withdrawn at the indicated times were then, in the case of modification in the absence of DNA, supplemented with substrate DNA and incubated at 37°C for 10 min in buffer D. The reaction products were analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis (S, substrate DNA; ST, DNA length standard; C, control, no modification). (A) The upper gel shows inactivation of GST–mCAD by DEPC in the absence of plasmid DNA, whereas the lower gel demonstrates protection of GST–mCAD from efficient inactivation by DEPC in the presence of 120 ng/µl plasmid DNA (pBSK-VDEX). (B) DEPC-modified nuclease produces fragments of defined length (black arrows) in addition to randomly cut DNA fragments.

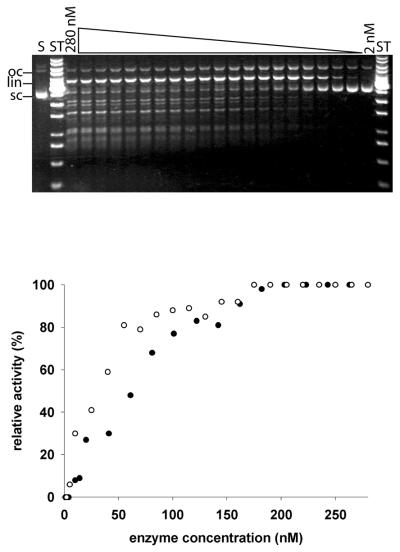

Figure 8.

Protein concentration dependence of the rate of plasmid DNA cleavage by the GST–mCAD variant H308N. Final concentrations of 2, 5, 10, 25, 40, 55, 70, 85, 100, 115, 130, 145, 160, 175, 190, 205, 220, 235, 250, 265 and 280 nM of the variant H308N of GST–mCAD were incubated for 30 min at 37°C in the same buffer as used in the experiment described in the legend to Figure 5. After incubation the cleavage products were analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis (upper). For comparison, the protein concentration dependence of plasmid DNA cleavage by wild-type CAD (open circle) and the CAD variant H308N (filled circle) are shown, normalised to the maximum rate of cleavage (lower). Note again (upper) the defined cleavage pattern produced by H308N, which resembles that of a restriction enzyme. Note also again the processive cleavage mode.

Generation of GST–mCAD variants by site-directed mutagenesis

In order to determine which of the conserved histidine residues in the catalytic domain of murine CAD might be involved in the mechanism of phosphodiester bond hydrolysis by this nuclease, we generated the GST–mCAD variants H127N, H242N, H263N, H304N, H308N and H313N. To exclude as far as possible local structural perturbations we chose His→Asn substitution, because asparagine is almost isosteric to histidine and has a similar polarity to unprotonated histidine. All nuclease variants were expressed as a GST–mCAD–hICAD-L complex in E.coli (data not shown). The fact that they could be isolated as a GST–mCAD–hICAD-L complex, from which they were liberated by caspase 3 treatment (see Fig. 4A), shows that the amino acid substitutions introduced do not impair the capability of the nuclease variants to bind firmly to hICAD-L.

Gel filtration analyses of GST–mCAD variants

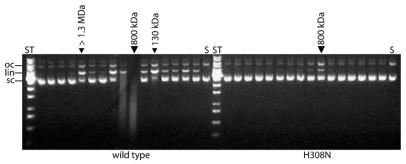

To determine to what extent homo-oligomerisation of CAD, which is a prerequisite for activity of this nuclease (7,21), is affected by the amino acid substitutions, gel filtration experiments were carried out on a Superdex-200 column with free GST–mCAD variants liberated from the complex by caspase 3 cleavage. All variants produced exhibited the same elution profile with a major peak at ∼800 kDa and a minor peak at the position of the void volume, except for variant H242N, which lacks the peak corresponding to the molecular mass of ∼800 kDa. This mutant exhibits a broad peak distributed over several fractions, corresponding to a molecular mass of between 130 and 800 kDa (data not shown). Aliquots of the fractions of wild-type GST–mCAD and one of the more active variants, H308N, were also subjected to plasmid DNA cleavage assay (Fig. 3). The highest activities of wild-type GST–mCAD and variant H308N, respectively, were observed in the fractions corresponding to an apparent molecular mass of ∼800 kDa, indicating that both variants are active as oligomers. Minor activity peaks were also observed in fractions representing the void volume of the gel filtration column (>1.3 MDa) and in fractions in which one would expect proteins of ∼130 kDa, corresponding to the molecular mass of dimeric GST–mCAD.

Figure 3.

Analysis of the oligomerisation state of wild-type GST–mCAD and GST–mCAD variant H308N by gel filtration. Aliquots of 15 µg recombinant wild-type GST–mCAD and variant H308N were fractionated by chromatography over a Superdex 200 gel filtration column at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Fractions of 1 ml were collected and aliquots of 15 µl were subjected to DNA cleavage assay in a buffer consisting of 12 mM MES–HCl, pH 6.8, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, 0.01% CHAPS and 5 mM MgCl2 for 1 h at 37°C, using 20 ng/µl plasmid DNA (pBSK-VDEX). After incubation the samples were analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The major activity peak is represented by the 800 kDa fraction for both wild-type CAD and the H308N variant. Minor activity peaks are observed for the >1.3 MDa and the 130 kDa fractions of wild-type CAD.

CD spectroscopy of murine CAD variants

All variants of GST–mCAD produced in this study bound to the inhibitor and chaperone hICAD-L (DFF45), which argues for integrity of the structure of GST–mCAD in the presence of hICAD-L. In order to exclude the possibility that the wild-type and mutant forms of free recombinant CAD lose their structural integrity when liberated from the complex with hICAD-L by caspase 3 treatment, we performed a CD spectroscopic analysis of these proteins. As can be seen from Figure 4B, all GST–mCAD variants but one, H242N, showed similar CD spectra, indicating that these variants have the same secondary structure as the wild-type enzyme, even after dissociation from the complex. This result makes it likely that the altered catalytic activities which we observed with these variants of murine CAD (see below), with the possible exception of H242N, were due to local effects at the site of amino acid substitution rather than global effects on the structural integrity of the enzyme. The CD spectrum of the variant H242N has a significantly increased CD signal at ∼220 nm, indicating a change in secondary structure compared to the wild-type enzyme. It is noteworthy that H242N is the only variant that shows aberrant chromatographic behaviour upon gel filtration (see above).

DNA cleavage activity of GST–mCAD variants with substitutions of conserved histidine residues in the catalytic domain of the enzyme

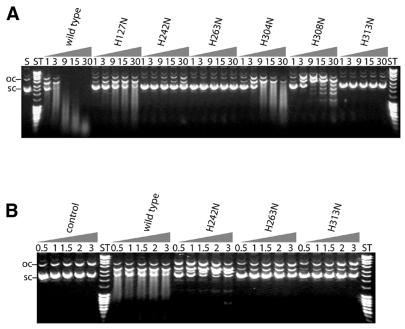

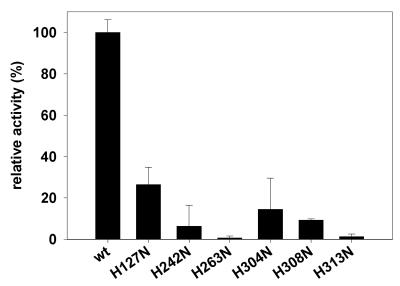

No assay exists for CAD allowing a rigorous steady-state kinetic analysis and thereby determination of the Km and kcat values. We have, therefore, determined relative activities of the free GST–mCAD variants by plasmid DNA cleavage assays under steady-state conditions after activation of the GST–mCAD–hICAD-L complexes with caspase 3 as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 5A and B). Relative activities determined from the plasmid cleavage assays revealed that all six His→Asn variants of GST–mCAD exhibit reduced catalytic activities (Fig. 6). The variants with reasonable activity (>10% of the wild-type activity as determined with the plasmid DNA cleavage assay), H127N, H304N and H308N, show a processive DNA cleavage mode, like the wild-type enzyme, as can be deduced from the DNA cleavage kinetics, in which substantial amounts of the supercoiled, open circular and linear forms of plasmid DNA remained uncleaved long after further DNA degradation had begun to take place. Variant H127N retained the highest catalytic activity among all mutants analysed, in the region of 25% of that of wild-type GST–mCAD, indicating that this residue is most likely not directly involved in the enzymatic reaction catalysed by CAD, but could be involved in binding the substrate. Variants H242N, H263N and H313N exhibited markedly reduced catalytic activities, which for variants H263N and H313N were ∼1% and for variant H242N were ∼5% of wild-type GST–mCAD activity. Whereas amino acid residue His313 of murine CAD is only partially conserved in the CAD sequences from the five species (Fig. 1), the amino acid residues His242 and His263 are located within highly conserved sequence blocks, similarly to residues His304 and His308, which, however, when substituted by asparagine exhibited catalytic activities only ∼10-fold lower than wild-type CAD. These results suggest that one highly conserved (His263) and one partially conserved histidine residue (His313) might be directly involved in the catalytic mechanism of DNA cleavage by CAD, whereas the other conserved histidine residues might be required for efficient substrate binding. For His242 we have evidence that it could play a structural role (see above).

Figure 5.

DNA cleavage activities of mutant forms of CAD variants with substitutions of conserved histidine residues in the catalytic domain of the nuclease. (A) Activities of the nuclease variants were determined using a plasmid DNA cleavage assay. The final concentration of wild-type GST–mCAD and the variant H127N was 54 nM, that of all other variants 540 nM. The nuclease variants were incubated at 37°C in the presence of 25 ng/µl plasmid DNA (pBSK-VDEX) in buffer D. Aliquots were withdrawn from the reaction mixture after the indicated time (min) and analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis as described in Materials and Methods (S, substrate DNA; ST, DNA length standard). (B) The variants with the lowest residual activities were incubated for a prolonged time (h) in order to distinguish between their relative activities. As a control, wild-type nuclease at a 100-fold lower concentration (5.4 nM) than the mutant enzymes (540 nM) and plasmid DNA (pBSK-VDEX) were also incubated under the same conditions (ST, DNA length standard). Note that H127N and H304N in (A) as well as wild-type GST–CAD in (B) show a processive cleavage behaviour: there is supercoiled, open circular and linear DNA remaining, in spite of the fact that the reaction has progressed, i.e. a ‘smear’ has already been produced.

Figure 6.

Relative activities of the different CAD variants as determined by plasmid DNA cleavage assay. The relative activities are given as the mean values of three independent experiments, determined from the rate of initial disappearance of supercoiled plasmid DNA substrate.

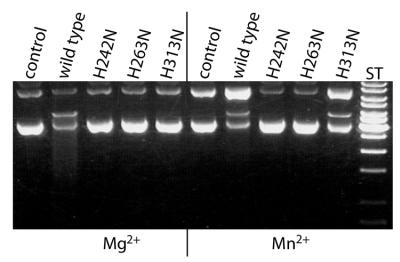

Several Mg2+-dependent nucleases accept Mn2+ as a cofactor and quite often nuclease variants that are inactive in the presence of Mg2+ can be partially rescued by Mn2+. This is the case with H313N, but not, however, with H242N and H263N (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Comparison of the DNA cleavage activity of wild-type GST–mCAD and the variants H242N, H263N and H313N in the presence of Mg2+ or Mn2+ as cofactor. Wild-type GST–mCAD (48 nM final concentration) and the variants H242N, H263N and H313N (600 nM final concentration) were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with 25 ng/µl plasmid DNA (pBSK-VDEX) with Mg2+ or Mn2+ as divalent metal ion cofactor. Cleavage products were analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis as described in Materials and Methods. Whereas no activity is detected under the conditions chosen for the three variants in the presence of Mg2+, activity is seen with H313N in the presence of Mn2+.

Mutant H308N of murine CAD exhibits an altered cleavage pattern when hydrolysing DNA

GST–mCAD, when cleaving plasmid DNA in vitro, produces an apparently random cleavage pattern, appearing as a ‘smear’ when analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis, indicating that CAD functions as a non-specific nuclease. During the chemical modification experiments we noticed that DEPC-modified GST–mCAD, when cleaving DNA, not only produces a random cleavage pattern, but superimposed on this pattern were also fragments of defined length (Fig. 2B). As can be seen from Figure 5A, the mutant form H308N of GST–mCAD produces fragments of defined length rather than a ‘smear’. A similar pattern was also observed in DNA cleavage experiments with the H242N variant (Fig. 5B), however, because of the much lower activity of this variant, it could not be analysed in detail. The pattern produced was observed using different substrates, like supercoiled plasmid DNA, linearised plasmid DNA and phage λ DNA (data not shown). These results suggest that His308 is most likely to be involved in substrate binding and not directly in catalysis.

A possible explanation for the more specific mode of DNA cleavage by the H308N variant compared to the wild-type enzyme could be that its quaternary structure (oligomeric state), which is the same as that of wild-type CAD in the absence of DNA (see above), is different from wild-type mCAD in the presence of DNA. To analyse whether the oligomeric state of H308N is different from wild-type mCAD in the presence of DNA, we have determined the enzyme concentration dependence of DNA cleavage for the H308N variant and the wild-type enzyme. The dependence of plasmid DNA cleavage activity of wild-type GST–mCAD and the variant H308N on enzyme concentration turned out to be linear over two orders of magnitude in the nanomolar range (Fig. 8) and gave no evidence for a concentration-dependent activity change, as one would expect if there was a diminished tendency of this variant to homo-oligomerise, correlated with enzymatic activity (22).

DISCUSSION

The principal aim of our present study was to identify amino acid residues that are essential for catalytic activity of the apoptotic nuclease CAD. As a result of a protein sequence alignment of homologous apoptotic nucleases from five different species, namely mouse, rat, human, zebrafish and fruitfly, we have identified six conserved histidine residues in the catalytic domain of these enzymes (Fig. 1): histidine residues His127 and His313 are only partially conserved, whereas His242, His263, His304 and His308 (numbering based on the murine CAD sequence) are completely conserved among the five organisms. His127 corresponds to a serine residue (Ser126) in the zebrafish sequence and His313 corresponds to an arginine residue (Arg418) in the Drosophila sequence. Histidines are known to occur in the active sites of several non-specific deoxyribonucleases, e.g. DNase I (23), Serratia nuclease (24) and colicin E9 endonuclease (25), where they act as the general base or general acid, respectively, in the mechanism of hydrolysis of phosphodiester bonds. In order to determine whether histidine residues are essential for activity of the apoptotic nuclease we have chemically modified murine CAD expressed in E.coli using the histidine-specific reagent DEPC. We have shown here, that the nucleolytic activity of murine CAD is inhibited by DEPC treatment, suggesting that histidine residues are essential for CAD activity. In order to determine which of the histidine residues conserved in the five available sequences of homologous apoptotic nucleases are important for catalytic function of the nuclease, we have exchanged the amino acid residues His127, His242, His263; His304, His308 and His313 for asparagine in murine CAD, expressed the variants in E.coli and characterised them with respect to their structural integrity and DNA cleavage activity.

All of the variants of CAD produced in the present study exhibit a more or less pronounced decrease in catalytic activity compared to the wild-type enzyme, but were not detectably affected in their interaction with hICAD-L, as they could be isolated as a stable GST–mCAD–hICAD-L complex. The alterations in activity are therefore most likely not due to major structural perturbations of GST–mCAD caused by the amino acid substitution, as the secondary structure (CD) and quaternary structure (oligomerisation state) of the variants show no significant differences compared to the wild-type enzyme, except for variant H242N, whose decrease in activity, therefore, may be due to alterations in structure, which become manifest after separation from its chaperone and inhibitor hICAD-L. We suppose that His242 has a structural role: its substitution by asparagine changes the secondary structure and in turn also the oligomeric state of the enzyme. The results of our structural analyses imply that the effects on DNA cleavage activity which are observed with all the other variants are most likely due to the absence of a functional group required for DNA binding and/or cleavage. Of course, we cannot exclude subtle structural effects of the amino acid substitutions which indirectly impair catalytic activity. It is noteworthy that the GST moiety (usually dimeric itself) of the CAD fusion proteins investigated in the present study does not seem to interfere with oligomerisation of the nuclease, which is similar to that observed with the human homologue of CAD (7).

Variants H127N, H304N and H308N have between 10 and 25% of the activity of the wild-type enzyme. This level of residual activity is most likely too high for a variant with substitution of a truly catalytic residue. For example, the H134Q and H252Q variants of bovine DNase I have <0.01% of the wild-type activity (26). Likewise, the H89N variant of Serratia nuclease has ∼0.01% of the wild-type activity (27). A residual activity of 10–25% is much more compatible with a defect in binding. Examples are provided by the R9A variant of DNase I (26) or the variant R131A of Serratia nuclease (27), with ∼10% of wild-type activity. It could also be that His127, His304 and His308 exert long-range electrostatic effects on a histidine residue in the catalytic center, which are disturbed in the variants, as demonstrated for RNase A (28). On the other hand, for RNase T1 it has been demonstrated that replacement of the presumptive catalytic residue Glu58 by Asp or Gln leads to an activity drop of only 10 or 7%, respectively (29). In this case, however, it is suspected that His40 takes over the role of Glu58. Replacement of the other catalytic residue, His92, by Ala leads to an almost inactive mutant (30,31)

The substitution of His308 by an asparagine residue has another interesting consequence: it has a profound effect on the DNA cleavage pattern produced, which is well defined (see Fig. 8), rather than represented by a ‘smear’, as expected for a non-specific nuclease. A defined cleavage pattern was also observed, albeit not as clear, with the H242N variant and with DEPC-modified CAD. The generation of such defined fragments could be explained by more pronounced sequence preferences of the mutant enzyme compared to wild-type CAD, indicating that His308 might be involved in DNA binding by supplying a subsite in which interactions with the sugar–phosphate backbone of the DNA take place. If this subsite is affected by an amino acid substitution, some sequences are not cleaved, resulting in a defined cleavage pattern.

The very low DNA cleavage activities of the H263N and H313N variants of GST–mCAD suggest that histidine residues His263 and His313 might play an important role in the mechanism of phosphodiester bond hydrolysis by murine CAD. These residues could act as a general base or general acid, similarly to bovine pancreatic DNase I, where two histidine residues, His134 and His252, are essential for catalytic activity in providing general base (water activation) and general acid (leaving group protonation) catalysis, respectively (26). Other non-specific nucleases, like DNase II (32) and Serratia nuclease have only one catalytic histidine residue, which in the case of the latter enzyme provides general base catalysis (27). The fact that His313 of murine CAD in the Drosophila sequence is replaced by an arginine (R418) suggests that this residue most likely does not function as a general acid or general base in the catalytic mechanism of CAD, but rather points towards a function of this residue in transition state stabilisation. The observed residual activity of the H313N variant, ∼1% of wild-type CAD activity, is compatible with such a function of His313 in the wild-type enzyme. For Serratia nuclease a 200-fold reduction in activity compared to the wild-type enzyme was measured for the R57A variant. Arg57 in this enzyme is considered to be the principal residue responsible for transition state stabilisation (27). The fact that H313N can be slightly activated by Mn2+ as cofactor supports this conclusion, because asparagine could function as a Me2+ ligand, as shown for Serratia nuclease (33,34), as well as the homing endonuclease I-PpoI (35,36) and T4 endonuclease VII (37). In the H313N variant of mCAD a Mn2+ ion bound to Asn313 could serve to stabilise the transition state, similarly to as proposed for DNase I (26), where two Mg2+ ions bound to Glu39 and Asp168 might play this role. On the basis of our results it is tempting to speculate that His263 of murine CAD, and the corresponding homologous residues in the related enzymes, might act as the general base or general acid during phosphodiester bond hydrolysis by these nucleases. We are aware of the fact that neither chemical modification nor site-directed mutagenesis experiments can provide unequivocal evidence for catalytic involvement of a particular amino acid residue. This is only possible with reference to detailed structural information. In the absence of such information, however, experiments of the kind described here may help in obtaining an idea about possible mechanisms. For example, our experimental results argue for His263 of murine CAD being one of the key residues in the hydrolysis reaction catalysed by CAD. This must be further analysed by investigations into the specific role of this and the other histidine residues identified as important for CAD activity in the present study and into which other amino acid residues participate in DNA cleavage by the apoptotic nuclease. Of major importance will be identification of the Mg2+-binding amino acid(s) of the apoptotic nuclease.

NOTE ADDED IN PROOF

After submissin of this manuscript we learned that Sakahira et al. also studied the role of conserved histidine residues in the catalytic mechanism of the caspase-activated DNase (38).

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr X. Wang for hamster caspase 3 cDNA and Ms Ute Konradi for expert technical assistance. This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Pi 122/16-1) and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie. The stay of O.G. at Giessen was supported by the Deutsche Akademische Austauschdienst. S.R.S. is a member of the Graduiertenkolleg ‘Biochemie von Nukleoproteinkomplexen’.

References

- 1.Liu X., Zou,H., Slaughter,C. and Wang,X. (1997) DFF, a heterodimeric protein that functions downstream of caspase-3 to trigger DNA fragmentation during apoptosis. Cell, 89, 175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enari M., Sakahira,H., Yokoyama,H., Okawa,K., Iwamatsu,A. and Nagata,S. (1998) A caspase-activated DNase that degrades DNA during apoptosis and its inhibitor ICAD. Nature, 391, 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halenbeck R., MacDonald,H., Roulston,A., Chen,T.T., Conroy,L. and Williams,L.T. (1998) CPAN, a human nuclease regulated by the caspase-sensitive inhibitor DFF45. Curr. Biol., 8, 537–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu X., Li,P., Widlak,P., Zou,H., Luo,X., Garrard,W.T. and Wang,X. (1998) The 40-kDa subunit of DNA fragmentation factor induces DNA fragmentation and chromatin condensation during apoptosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 8461–8466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagata S. (2000) Apoptotic DNA fragmentation. Exp. Cell Res., 256, 12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakahira H., Enari,M. and Nagata,S. (1998) Cleavage of CAD inhibitor in CAD activation and DNA degradation during apoptosis. Nature, 391, 96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu X., Zou,H., Widlak,P., Garrard,W. and Wang,X. (1999) Activation of the apoptotic endonuclease DFF40 (caspase-activated DNase or nuclease). Oligomerization and direct interaction with histone H1. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 13836–13840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toh S.Y., Wang,X. and Li,P. (1998) Identification of the nuclear factor HMG2 as an activator for DFF nuclease activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 250, 598–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durrieu F., Samejima,K., Fortune,J.M., Kandels-Lewis,S., Osheroff,N. and Earnshaw,W.C. (2000) DNA topoisomerase II alpha interacts with CAD nuclease and is involved in chromatin condensation during apoptotic execution. Curr. Biol., 10, 923–9264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inohara N., Koseki,T., Chen,S., Wu,X. and Núñez,G. (1998) CIDE, a novel family of cell death activators with homology to the 45 kDa subunit of the DNA fragmentation factor. EMBO J., 17, 2526–2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inohara N., Koseki,T., Chen,S., Benedict,M.A. and Núñez,G. (1999) Identification of regulatory and catalytic domains in the apoptosis nuclease DFF40/CAD. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 270–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lugovskoy A.A., Zhou,P., Chou,J.J., McCarty,J.S., Li,P. and Wagner,G. (1999) Solution structure of the CIDE-N domain of CIDE-B and a model for CIDE-N/CIDE-N interactions in the DNA fragmentation pathway of apoptosis. Cell, 99, 747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uegaki K., Otomo,T., Sakahira,H., Shimizu,M., Yumoto,N., Kyogoku,Y., Nagata,S. and Yamazaki,T. (2000) Structure of the CAD domain of caspase-activated DNase and interaction with the CAD domain of its inhibitor. J. Mol. Biol., 297, 1121–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otomo T., Sakahira,H., Uegaki,K., Nagata,S. and Yamazaki,T. (2000) Structure of the heterodimeric complex between CAD domains of CAD and ICAD. Nature Struct. Biol., 7, 658–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou P., Lugovskoy,A.A., McCarty,J.S., Li,P. and Wagner,G. (2001) Solution structure of DFF40 and DFF45 N-terminal domain complex and mutual chaperone activity of DFF40 and DFF45. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 6051–6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu X., Kim,C.N., Yang,J., Jemmerson,R. and Wang,X. (1996) Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: requirement for dATP and cytochrome c. Cell, 86, 147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirsch R.D. and Joly,E. (1998) An improved PCR-mutagenesis strategy for two-site mutagenesis or sequence swapping between related genes. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 1848–1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pace C.N., Vajdos,F., Fee,L., Grimsley,G. and Gray,T. (1995) How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci., 4, 2411–2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerlt J.A. (1993) Mechanistic principles of enzyme-catalyzed cleavage of phosphodiester bonds. In Linn,S.M., Lloyd,R.S. and Roberts,R.J. (eds), Nucleases, 2nd Edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 1–34.

- 20.Cowan J.A. (1998) Metal activation of enzymes in nucleic acid biochemistry. Chem. Rev., 98, 1067–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Widlak P. and Garrard,W.T. (2001) Ionic and cofactor requirements for the activity of the apoptotic endonuclease DFF40/CAD. Mol. Cell. Biochem., 218, 125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedhoff P., Lurz,R., Lüder,G. and Pingoud,A. (2001) Sau3aI, a monomeric type II restriction endonuclease that dimerizes on the DNA and thereby induces DNA loops. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 23581–23585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suck D., Oefner,C. and Kabsch,W. (1984) Three-dimensional structure of bovine pancreatic DNase I at 2.5 Å resolution. EMBO J., 3, 2423–2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller M.D., Tanner,J., Alpaugh,M., Benedik,M.J. and Krause,K.L. (1994) 2.1 Å structure of Serratia endonuclease suggests a mechanism for binding to double-stranded DNA. Nature Struct. Biol., 1, 461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleanthous C., Kuhlmann,U.C., Pommer,A.J., Ferguson,N., Radford,S.E., Moore,G.R., James,R. and Hemmings,A.M. (1999) Structural and mechanistic basis of immunity toward endonuclease colicins. Nature Struct. Biol., 6, 243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones S.J., Worrall,A.F. and Connolly,B.A. (1996) Site-directed mutagenesis of the catalytic residues of bovine pancreatic deoxyribonuclease I. J. Mol. Biol., 264, 1154–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedhoff P., Kolmes,B., Gimadutdinow,O., Wende,W., Krause,K.-L. and Pingoud,A. (1996) Analysis of the mechanism of the Serratia nuclease using site-directed mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 2632–2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher B.M., Schultz,L.W. and Raines,R.T. (1998) Coulombic effects of remote subsites on the active site of ribonuclease A. Biochemistry, 37, 17386–17401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steyaert J., Hallenga,K., Wyns,L. and Stanssens,P. (1990) Histidine-40 of ribonuclease T1 acts as base catalyst when the true catalytic base, glutamic acid-58, is replaced by alanine. Biochemistry, 29, 9064–9072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishikawa S., Morioka,H., Kim,H.J., Fuchimura,K., Tanaka,T., Uesugi,S., Hakoshima,T., Tomita,K., Ohtsuka,E. and Ikehara,M. (1987) Two histidine residues are essential for ribonuclease T1 activity as is the case for ribonuclease A. Biochemistry, 26, 8620–8624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grunert H.P., Zouni,A., Beineke,M., Quaas,R., Georgalis,Y., Saenger,W. and Hahn,U. (1991) Studies on RNase T1 mutants affecting enzyme catalysis. Eur. J. Biochem., 197, 203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liao T.H. (1985) The subunit structure and active site sequence of porcine spleen deoxyribonuclease. J. Biol. Chem., 260, 10708–10713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller M.D., Cai,J. and Krause,K.L. (1999) The active site of Serratia endonuclease contains a conserved magnesium-water cluster. J. Mol. Biol., 288, 975–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shlyapnikov S.V., Lunin,V.V., Perbandt,M., Polyakov,K.M., Lunin,V.Y., Levdikov,V.M., Betzel,C. and Mikhailov,A.M. (2000) Atomic structure of the Serratia marcescens endonuclease at 1.1 Å resolution and the enzyme reaction mechanism. Acta Crystallogr., 56D, 567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flick K.E., Jurica,M.S., Monnat,R.J.Jr and Stoddard,B.L. (1998) DNA binding and cleavage by the nuclear intron-encoded homing endonuclease I-PpoI. Nature, 394, 96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galburt E.A., Chevalier,B., Tang,W., Jurica,M.S., Flick,K.E., Monnat,R.J.Jr and Stoddard,B.L. (1999) A novel endonuclease mechanism directly visualized for I-PpoI. Nature Struct. Biol., 6, 1096–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raaijmakers H., Toro,I., Birkenbihl,R., Kemper,B. and Suck,D. (2001) Conformational flexibility in T4 endonuclease VII revealed by crystallography: implications for substrate binding and cleavage. J. Mol. Biol., 308, 311–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakahira H., Takemura,Y. and Nagata,S. (2001) Enzymatic active site of caspase-activated DNase (CAD) and its inhibition by inhibitor of CAD. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 388, 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]