Short abstract

Voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.7 is a key molecule in nociception, and its dysfunction has been associated with various pain disorders. Here, we investigated the regulation of Nav1.7 biophysical properties by Fyn, an Src family tyrosine kinase. Nav1.7 was coexpressed with either constitutively active (FynCA) or dominant negative (FynDN) variants of Fyn kinase. FynCA elevated protein expression and tyrosine phosphorylation of Nav1.7 channels. Site-directed mutagenesis analysis identified two tyrosine residues (Y1470 and Y1471) located within the Nav1.7 DIII-DIV linker (L3) as phosphorylation sites of Fyn. Whole-cell recordings revealed that FynCA evoked larger changes in Nav1.7 biophysical properties when expressed in ND7/23 cells than in Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK) 293 cells, suggesting a cell type-specific modulation of Nav1.7 by Fyn kinase. In HEK 293 cells, substitution of both tyrosine residues with phenylalanine dramatically reduced current amplitude of mutant channels, which was partially rescued by expressing mutant channels in ND7/23 cells. Phenylalanine substitution showed little effect on FynCA-induced changes in Nav1.7 activation and inactivation, suggesting additional modifications in the channel or modulation by interaction with extrinsic factor(s). Our study demonstrates that Nav1.7 is a substrate for Fyn kinase, and the effect of the channel phosphorylation depends on the cell background. Fyn-mediated modulation of Nav1.7 may regulate DRG neuron excitability and contribute to pain perception. Whether this interaction could serve as a target for developing new pain therapeutics requires future study.

Keywords: Voltage-gated sodium channel, Fyn, patch clamp, tyrosine kinase, phosphorylation

Introduction

Voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSCs) play essential roles in initiation and propagation of action potentials (APs) in excitable cells. VGSCs are transmembrane protein complexes composed of one pore-forming α subunit associated with one or more auxiliary β subunits.1 The intrinsic properties of the sodium channel α-subunit determine the voltage dependence and gating properties of VGSCs. Nine genes have been identified to encode sodium channel α-subunits, producing Nav1.1 to Nav1.9 channels. Different sodium channel isoforms exhibit unique biophysical properties, protein expression, and tissue distribution.1

Encoded by SCN9A, Nav1.7 is preferentially expressed in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons and sympathetic ganglion neurons in peripheral nervous system.2 Hyperpolarized activation and slow kinetics of closed-state fast inactivation of Nav1.7 allows it to act as a threshold channel for AP firing in nociceptive DRG neurons and as a key player in nociception.3 Dysfunction of Nav1.7 has been associated to several pain disorders. For example, nonsense mutations of SCN9A prevent mutation carriers from experiencing pain (congenital insensitive to pain).4 In contrast, gain-of-function mutations of Nav1.7 could reduce AP threshold and increase neuronal excitability in DRG neurons, causing painful disorders including erythromelalgia and paroxysmal extreme pain disorder.5 The preferential expression in peripheral sensory neurons has made Nav1.7 channel a prime target for the development of new analgesics, with the expectation that isoform-specific blockers of Nav1.7 might effectively attenuate pain without causing dose-limiting central nervous system side effects. Numerous efforts have been invested in developing Nav1.7-selective blockers over the last decade, but only a few compounds have been tested in clinical studies.6–8

The Nav1.7 polypeptide of 1977 amino acids includes a plethora of sites or motifs subject to various post-translational modifications (PTMs), which modulate expression, trafficking, stability, and gating properties of the channel, and therefore are expected to alter neuronal excitability.9 Nav1.7 is phosphorylated by PKA, PKC, and ERK1/2.10–12 Activation of these kinases alters Nav1.7 properties and impacts its physiological or pathological functions. For example, both protein expression and tyrosine phosphorylation of Nav1.7 channels were elevated in DRG neurons of STZ-induced diabetic rat, which would contribute to the development of thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia in painful diabetic neuropathy.13 Activated ERK1/2 (phosphorylated ERK1/2, pERK1/2), which is present within DRG neurons, shifts activation and steady-state fast inactivation of Nav1.7 channels in a hyperpolarizing direction.11 Blocking ERK1/2 activity in cultured DRG neurons reduced AP firing frequency, implicating a positive regulation of neuronal excitability by pERK1/2.11 In experimental rat neuromas, pERK1/2 is elevated and colocalizes with Nav1.7 within transected axons, which would be expected to facilitate initiation of APs and contribute to hypersensitivity and spontaneous firing in injured fibers in the neuromas.14 These studies support important roles of PTMs in regulating Nav1.7 biophysical properties and contribution to regulating DRG neuron excitability.

Fyn kinase is a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase belonging to Src family kinases, which regulates many neuronal properties, including myelination, neurite outgrowth, and synaptic plasticity.15 The human brain Fyn kinase is a 59-kDa protein composed of 537 amino acids, and its kinase activity is closely associated with the phosphorylation/dephosphorylation states of two critical tyrosine residues—Y420 and Y531. The phosphorylation of Y420 stabilizes the active state of Fyn kinase, whereas phosphorylation of the C-terminal Y531 locks the kinase in an inactive state.15 It is well known that Fyn kinase interacts with NMDA receptors and AMPA receptors, modulating synaptic activity.16,17 Fyn kinase phosphorylates Nav1.2 and Nav1.5 channels and alters gating properties of both channels.18,19 Recently, Dustrude et al. reported that Fyn-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of collapsing response mediator protein 2 (CRMP2) impairs CRMP2 SUMOylation, which triggers Nav1.7 internalization and attenuates neuronal excitability.20 However, a direct effect of Fyn kinase on Nav1.7 channel properties has not been reported.

Here, we investigated whether Nav1.7 channel is a substrate for Fyn kinase using constitutively active (FynCA) and dominant negative (FynDN) variants of Fyn kinase. Our results demonstrate FynCA-mediated upregulation of Nav1.7 protein expression and tyrosine phosphorylation and identify two tyrosine residues within the DIII-DIV linker (L3) as Fyn phosphorylation sites. Whole-cell recordings reveal that FynCA differentially modulates Nav1.7 biophysical properties in Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK) 293 cells and in ND7/23 cells, suggesting a cell background-specific modulation of Nav1.7 properties by Fyn kinase. Our study provides new information to the regulation of Nav1.7 channels, which may improve our understandings of the molecular mechanism of nociception and contribute to new therapeutic approaches for pain management.

Materials and methods

Plasmid preparation

At the present, there is no selective activator/blocker of Fyn kinase; therefore, vectors expressing constitutively active (FynCA) or dominant-negative (FynDN) Fyn kinase were introduced into cells to manipulate Fyn activity. The expression vectors encoding human wild-type (WT) and catalytically inactive (FynDN) Fyn kinases were obtained from Addgene (Cambridge, MA), and the construct encoding a constitutively active Fyn variant (FynCA) was generated from expression vector of WT by site-direct mutagenesis. The stop codons were mutated and the coding regions of FynCA or FynDN were then introduced into pLVX-IRES-mCherry upstream of the coding region of mCherry to obtain vectors expressing FynCA-mCherry and FynDN-mCherry fusion proteins.

The plasmid pcDNA3-Nav1.7r (referred as Nav1.7r) encodes the full-length human Nav1.7 channel that has been described previously.21 Nav1.7r contains a Y362S substitution, which converts the tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive channel into TTX-resistant channels. Nav1.7rG was constructed by mutating Nav1.7r stop codon and inserting the cDNA of enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (eGFP) downstream the coding region of Nav1.7r. Expression vectors encoding Nav1.7rG-Y1470F, Nav1.7rG-Y1471F, and Nav1.7rG-Y1470F/Y1471F (Nav1.7rG-YYFF) mutants were generated by site-direct mutagenesis with primers listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used for site mutagenesis of Nav1.7 expression vector in the study.

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Y1470F-Fw | GAAGAAATTCTATAATGCAATGAAAAAGCTGGGGTCCAAG |

| Y1470F-Re | GCATTATAGAATTTCTTCTGTTCTTCTGTCATAAAGATGTCTTG |

| Y1471F-Fw | GAAGAAATACTTTAATGCAATGAAAAAGCTGGGGTCCAAG |

| Y1471F-Re | GCATTAAAGTATTTCTTCTGTTCTTCTGTCATAAAGATGTCTTG |

| YYFF-Fw | GAAGAAATTCTTTAATGCAATGAAAAAGCTGGGGTCCAAG |

| YYFF-Re | GCATTAAAGAATTTCTTCTGTTCTTCTGTCATAAAGATGTCTTG |

Cell culture and transfection

HEK 293 or ND7/23 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (100 µg/ml) (Invitrogen). HEK 293 cell line stably expressing Nav1.7r protein (referred to as HEK-Nav1.7st cell hereinafter) was maintained by addition of G418 (600 µg/ml) into the culture medium. Transient transfections were carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or Hieff Trans™ Liposomal Transfection Reagent (Yeasen Bio Tech, Shanghai). The coding regions of all constructs used in this study were sequenced before experiments to ensure the absence of unintended mutations.

Western blot

To examine the effect of Fyn kinase on Nav1.7 expression, HEK-Nav1.7st cells were transfected with FynCA-mCherry or FynDN-mCherry, respectively. At 24–36 h after transfection, cells were harvested and lysed in freshly prepared RIPA buffer containing (mM) 150 NaCl, Tris/HCl 50, EDTA 0.5, pH7.4, complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche), and 1% Triton X-100. After a centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatants were collected, and the protein concentration was measured by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce Biotechnology). Aliquots were mixed with 4× NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) plus 100 mM Dithiothreitol (DTT), incubated at 37°C for 20 min, separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis , and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare). The membrane was then blocked with 10% dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 overnight at 4°C, probed with antibodies against VGSCs (PanNav, Sigma), Fyn (Santa Cruz), or glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, ABclonal), and detected with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Pierce). Band intensities were quantified using Image-Pro Plus software. Unless specified, the intensity of Nav1.7 immunoreactive band was normalized by the intensity of GAPDH in the corresponding lanes to eliminate sample loading variability.

Cell surface biotinylation

Membrane protein expression was examined by cell surface biotinylation. HEK-1.7st cells or ND7/23 cells were transiently transfected with FynCA-mCherry or FynDN-mCherry, respectively. At 36 h after transfection, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 8.0) for three times and incubated with 0.4 mM Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin (Thermo Scientific) at room temperature for 30 min. The biotinylation reaction was terminated by adding Tris solution (30 mM, pH 8.0) or glycine (20 mM in PBS, pH 8.0) after aspirating the Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin. Cells were washed again and lysed using RIPA buffer described above. The supernatants of cell lysates were rotated with NeutrAvidin Agarose Resins (Thermo Scientific) at 4°C for 3 h. The resins were centrifuged and the pellet was washed with Triton X-100-free RIPA buffer. The biotinylated membrane proteins were eluted with NuPAGE LDS sample buffer plus DTT, and the expression of membrane Nav1.7 was examined by Western blot. The equal membrane protein loadings were indicated by Na/K-ATPase signals.

Immunoprecipitation assay

For coimmunoprecipitation experiment, HEK 293 and HEK-Nav1.7st cells were transiently transfected with FynCA-mCherry. At 36 h after transfection, transfected cells together with one dish of untransfected HEK-Nav1.7st cells were washed and cell lysates were collected using RIPA buffer as described above. The supernatants of cell lysates were incubated with antisodium channel antibody (PanNav, Sigma) at 4°C for 5 h, followed by the addition of Protein A/G Agarose (Pierce) and a subsequent 3 h incubation at 4°C. The beads were washed with Triton X-100-free RIPA buffer, and proteins coimmunoprecipitated with Nav1.7 were eluted with NuPAGE LDS sample buffer plus DTT and examined by Western blot.

To examine Fyn-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of Nav1.7 channels, HEK-Nav1.7st cells were transfected with FynCA-mCherry or FynDN-mCherry. At 36 h after transfection, cells were washed and lysed using freshly prepared RIPA buffer with additional phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Scientific) added. The supernatants of cell lysates were incubated with PanNav antibody (Sigma) at 4°C for 5 h, followed by a 3 h-incubation with Protein A/G Agarose (Pierce) at 4°C. The beads were washed with Triton X-100-free RIPA buffer, and the immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted with NuPAGE LDS sample buffer plus DTT, and examined by Western blot. The antiphosphotyrosine 4G10 antibody (Millipore) was used to detect tyrosine phosphorylation level of Nav1.7 channels. After the ECL detection, the blot was stripped using Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Scientific) and reprobed with PanNav antibody. In the phosphorylation experiments of Nav1.7rG mutant channels, PanNav antibody was replaced with anti-GFP antibody (Roche) because the epitope recognized by PanNav antibody was interrupted by substitution of the two tyrosine residues, which severely impair the binding affinity of PanNav antibody to mutant channels (data not shown). At least three experiments were performed for each Nav1.7rG constructs. The phosphorylation level of Nav1.7rG-WT cotransfected with FynCA-mCherry (WT/FynCA) was set as 100% in each experiment, and the phosphorylation levels of mutant constructs/FynCA were presented as the percentages of that of WT/FynCA. The phosphorylation levels of samples expressing FynDN were not quantified due to extremely low total amount of sodium channels immunoprecipitated by anti-GFP antibody.

Electrophysiology

HEK 293 or ND7/23 cells were transiently transfected with Nav1.7r (Nav1.7rG for ND7/23) plus FynCA-mCherry or FynDN-mCherry. Voltage-gated sodium currents were examined at 24 h after transfection by whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices). Fire-polished electrodes (0.6–1.3 MΩ) were fabricated from 1.6 mm outer diameter borosilicate glass micropipettes (World Precision Instruments). Pipette potential was adjusted to zero before seal formation, and liquid junction potential was not corrected. Capacity transients were cancelled and voltage errors minimized with 75%–90% series resistance compensation. Voltage-dependent currents were acquired with Clampex 10.5 at 5 min after establishing whole-cell configuration, sampled at 50 or 100 kHz, and filtered at 5 kHz.

For current–voltage relationships, cells were held at −120 mV and stepped to a range of potentials (−80 to +60 mV in 5 mV increments with 5-s intervals) for 100 ms. Peak inward currents (I) were plotted as a function of depolarization potential to generate I-V curves. Activation curves were obtained by converting I to conductance (G) at each voltage (V) using the equation G = I/(V−Vrev), where Vrev is the reversal potential that was determined for each cell individually. Activation curves were fit with Boltzmann functions:

where Gmax is maximal sodium conductance, V1/2,act is the potential of half-maximal activation, V is the test potential, and k is the slope factor.

Steady-state fast inactivation was achieved with a series of 500-ms prepulses (−130 to −10 mV in 10 mV increments) and the remaining noninactivated channels were activated by a 40-ms step depolarization to −10 mV. Steady-state slow inactivation was determined with 30-s prepulses at voltages ranging from −130 to 10 mV followed by a 100-ms hyperpolarization at −120 mV to remove fast inactivation. Remaining available channels were activated by a 20-ms test pulse to −10 mV. Peak inward currents obtained from steady-state fast inactivation and slow inactivation protocols were normalized with the maximal peak current (Imax) and fit with Boltzman functions:

where V represents the inactivating prepulse potential and V1/2 represents the inactivation midpoint. V1/2,fast and V1/2,slow represent the midpoints for steady-state fast inactivation and slow inactivation, respectively. Rresist is the fraction of channels that are resistant to steady-state fast or slow inactivation.

The pipette solution contained (in mM) 140 CsF, 10 NaCl, 1 EGTA, 10 HEPES, pH 7.3 with CsOH (adjusted to 308 mOsm with dextrose). For recordings on HEK 293 cells, the extracellular solution contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 dextrose, pH 7.3 with NaOH (adjusted to 315mOsm with sucrose). For recordings on ND7/23 cells, TEACl (20 mM), CdCl2 (0.1 µM), and CsCl (5 mM) were included in extracellular solution to block endogenous voltage-gated potassium channels and calcium channels. TTX (300 nM) was added into both extracellular bath solutions to eliminate endogenous voltage-gated sodium currents.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Clampfit 10.5 (Molecular Devices) and OriginPro 8.5 (Microcal Software) and presented as means ± SE. For samples obeying a normal distribution, statistical significance was examined using the two-sample student t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by least significant difference post hoc test. For samples that failed to fall into a normal distribution, nonparametric Mann–Whitney test or Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunnett’s post hoc comparisons was used.

Results

FynCA elevates total protein level and cell surface expression of Nav1.7 channels

The effect of Fyn kinase on Nav1.7 expression was examined in HEK 293 cells stably expressing Nav1.7r channels (HEK-Nav1.7st cells). Vectors encoding FynCA or FynDN were transiently transfected in HEK-Nav1.7st cells. An additional blank control was included by transfecting empty pLVX-mCherry vectors to examine the effect of FynDN on Nav1.7 expression. Cells were collected at 24–36 h after transfection, and the total protein expression of Nav1.7 was examined by Western blot. Cells transfected with FynDN showed similar Nav1.7 expression to cells expressing the mCherry blank control (FynDN/mCherry: 1.02 ± 0.1 folds, n = 5), while FynCA dramatically increased the total Nav1.7 expression (FynCA/mCherry: 7.98 ± 1.68, n = 5, p < 0.05 vs. FynDN/mCherry) (Figure 1(a) and (b)). The similar level of Nav1.7 expression between cells transfected with mCherry blank control and cells expressing FynDN indicates very low activity of endogenous Fyn kinase in HEK-Nav1.7st cells. Therefore, the mCherry blank control was not included in the following experiment, and Fyn-mediated modulation of Nav1.7 was evaluated by directly comparing cells expressing FynCA with those expressing FynDN. To further confirm the upregulatory effect of FynCA on Nav1.7, PP2, an inhibitor of active Src family kinases, was added to the culture medium for 24 h before cell collection. FynCA-mediated upregulation of Nav1.7 was clearly attenuated by PP2 (FynCA/FynDN: 1.73 ± 0.36, n = 4 with PP2 compared to 7.06 ± 1.53 of control, p < 0.05, Figure 1(a) and (b)), supporting an upregulatory effect of FynCA on Nav1.7 expression.

Figure 1.

FynCA increases protein expression of Nav1.7 in HEK 293 cells stably expressing Nav1.7r channels (HEK-Nav1.7st cells). (a) Representative Western blot image of cells transfected with FynCA or FynDN with or without incubation of PP2 (a blocker of Src family kinases). The expression of Nav1.7 was detected using antisodium channel antibody (PanNav) and the sample loading variability was corrected by normalizing the intensity of Nav1.7 bands with that of GAPDH of the corresponding lane. FynCA increased the total protein expression of Nav1.7, which was almost completely eliminated by PP2. (b) The histograms of the Nav1.7 protein expression in cells expressing FynCA or FynDN, as well as the mean effect of PP2 on FynCA-induced upregulation of Nav1.7 channels. Data are presented as means ± SE, *p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA or two-sample student t test. (c) Representative Western blot image of cell surface biotinylation experiment. The PanNav antibody revealed two distinguishable bands (labeled with filled and open arrowheads) from the biotinylated samples. This probably reflects the different glycosylation levels of Nav1.7 channels. FynCA elevated cell surface expression of Nav1.7, with the majority channels not fully glycosylated. (d) The histograms of total expression and surface expression of Nav1.7 in cells transfected with FynCA or FynDN. Na/K-ATPase and GAPDH were used to correct sample loading variability for biotinylated samples and total lysates, respectively. FynCA increased surface expression of Nav1.7 for ∼3.23 ± 0.80 folds (n = 6), which was relatively less than that of total Nav1.7 expression (7.80 ± 1.75 folds, n = 6). Data are presented as means ± SE, *p < 0.05 by two-sample student t test. GAPDH: glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase.

VGSCs need to be inserted in the cell membrane to exert their functions in AP electrogenesis. Thus, we examined cell surface expression of Nav1.7 by biotinylation. Sample loading variance was eliminated by normalizing the intensity of Nav1.7 band to that of corresponding Na/K-ATPase or GAPDH band of the same sample. Cells expressing FynCA showed much higher surface expression of Nav1.7 (Figure 1(c)). Quantitation of the biotinylated protein fraction showed that the expression of FynCA also increased the Nav1.7 channels at the plasma membrane: (FynCA/FynDN: 3.23 ± 0.80 folds, n = 6, Figure 1(d)). Since the upregulation of total Nav1.7 expression was higher than the increase in membrane-bound channels (FynCA/FynDN of total Nav1.7 expression: 7.80 ± 1.75 folds, n = 6), the elevated cell surface expression of Nav1.7 is probably due to increased total protein expression.

Interestingly, two distinguishable bands of Nav1.7 were detected from the membrane fractions compared to one dominant band from total cell lysates (Figure 1(c)). This may result from differential glycosylation of membrane-bound Nav1.7 channels. Sodium channels at the cell surface undergo extensive glycosylation, increasing channel’s molecular weight by covalent attached N-acetylglucosamine and oligosaccharide chain.22 The upper bands (solid red arrowheads) may come from the fully glycosylated channels in plasma membrane, while the lower band (open red arrowheads) corresponds to core-glycosylated Nav1.7 channels (Figure 1(c)). The single dominant Nav1.7 band of total cell lysates indicates that only a small percent of Nav1.7 channels could be translocated to plasma membrane, and the majority of Nav1.7 proteins remain inside the cells and are not fully glycosylated (open red arrowheads).

FynCA kinase interacts with and phosphorylates Nav1.7 channels

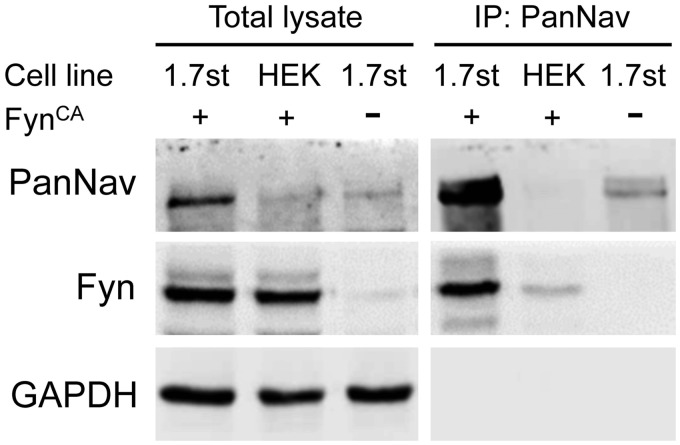

Early studies have shown that Fyn kinase interacts with Nav1.2 and Nav1.5 and phosphorylates both channels.18,19 To examine whether Fyn is also associated with Nav1.7 channels, coimmunoprecipitation experiments were carried out using anti-sodium channel antibody (PanNav). Fyn was detected from the pull-down sample of HEK-Nav1.7st cells transfected with FynCA but not from untransfected HEK-Nav1.7st cells (Figure 2). A weak Fyn band was observed from the pull-down sample of HEK 293 cells transfected with FynCA alone, probably due to residual nonspecific binding of Fyn to the agarose beads (Figure 2). These results demonstrate that Fyn kinase is associated with Nav1.7 channels in heterologous expression system.

Figure 2.

Fyn kinase is associated with Nav1.7 channels in transfected HEK-Nav1.7st cells. Western blot result shows the protein expression profile of total cell lysates (left) and pull-down samples precipitated by antisodium channel antibody (PanNav, right). Strong Fyn signal was detected in immunoprecipitated sample from HEK-Nav1.7st cells expressing FynCA, suggesting an association between Nav1.7 channel and Fyn kinase. Experiments were repeated for three times. GAPDH: glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase; HEK: Human Embryonic Kidney.

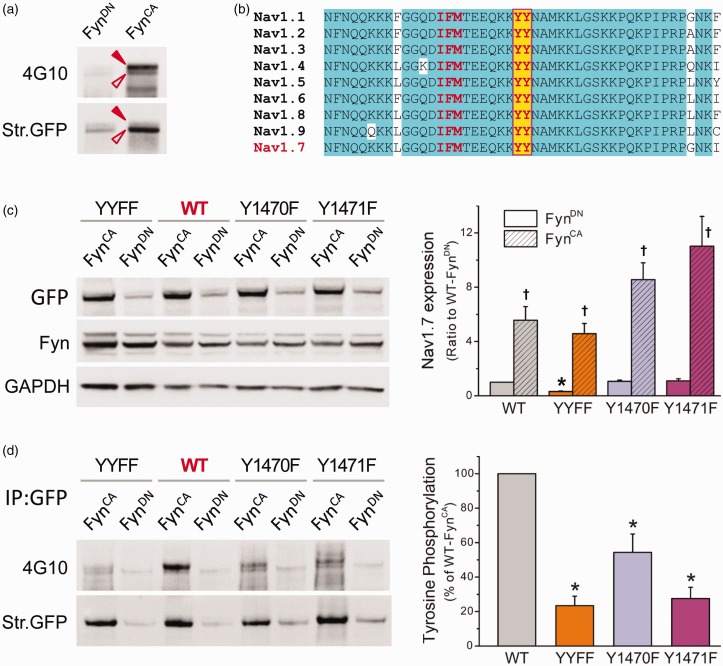

Next, we examined whether Nav1.7 was phosphorylated by FynCA. Nav1.7 channels were immunoprecipitated by PanNav antibody from total cell lysates of HEK-Nav1.7st cells transfected with FynCA or FynDN, and the tyrosine phosphorylation level of pull-down sodium channels was examined using 4G10 antiphosphotyrosine antibody. The blot was then stripped and reprobed with PanNav antibody to measure the total amount of immunoprecipitated Nav1.7 channels. Two distinguishable phosphotyrosine bands of Nav1.7 were detected, with the upper band being the major contributor to the phosphorylation signal (Figure 3(a)). It is known that the N-terminus of Fyn kinase contains residues for myristoylation and palmitoylation, which targets Fyn to lipid raft microdomain at the plasma membrane.23 Therefore, the membrane-bound Nav1.7 channels, some of which possess higher molecular weight due to glycosylation (Figure 1(c)), have more of a chance to interact with Fyn kinase and be phosphorylated. Weak phosphotyrosine signal was observed from Nav1.7 channels pulled down from cells expressing FynDN, probably due to background phosphorylation induced by other tyrosine kinases expressed in HEK 293 cells. FynCA caused a robust increase in Nav1.7 tyrosine phosphorylation (Figure 3(a)), suggesting that Nav1.7 is a substrate for Fyn kinase.

Figure 3.

Nav1.7 is subject to FynCA-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation. (a) FynCA or FynDN was transfected in HEK-Nav1.7st cells, and Nav1.7 channels were precipitated from cell lysate using antisodium channel antibody (PanNav). Tyrosine phosphorylation level was examined by antiphosphotyrosine antibody 4G10 (upper panel), the blot was then stripped and reprobed with PanNav antibody to reveal total Nav1.7 channels pulled down by PanNav (bottom panel). Two phosphotyrosine bands were detected, probably due to different glycosylation levels. The pull-down sample from cells expressing FynCA produced strong phosphotyrosine signal, demonstrating the contribution of Fyn to tyrosine phosphorylation of Nav1.7 channels. (b) The sequence alignment of the L3 of Nav1.7, which is highly conserved among human VGSCs. The tyrosine residues (highlighted with yellow color) are six residues away from the IFM inactivation motif. (c) Total protein expression of WT and mutant channels when cotransfected with FynCA or FynDN. The WT, Y1470F, and Y1471F channels exhibited similar total protein expressions when cotransfected with FynDN, while the expression of the YYFF double mutant was reduced. FynCA caused a significant increase in protein expression of all four constructs. Data are presented as means ± SE, *p < 0.05 versus total expression of WT/FynDN, †p < 0.05 versus corresponding channels cotransfected with FynDN, one-way ANOVA test. (d) The tyrosine phosphorylation levels of WT and mutant channels. The WT or mutant constructs were cotransfected with FynCA or FynDN in HEK 293 cells, and Nav1.7 channels were precipitated from cell lysate using anti-GFP antibody. Tyrosine phosphorylation level was examined by antiphosphotyrosine antibody 4G10 (upper panel), the blot was then stripped and reprobed with anti-GFP antibody to reveal total WT or mutant Nav1.7 channels immunoprecipitated by anti-GFP antibody (bottom panel). Substitution of either Y1470 or Y1471 or both dramatically reduced the phosphotyrosine levels of mutant channels, suggesting that both tyrosine residues are involved in Fyn-induced phosphorylation of Nav1.7 channels. The right panel is the histogram of FynCA-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of WT and mutant channels presented as the percentages of the phosphotyrosine level of WT channels. Data are presented as mean ± SE, *p < 0.05 versus WT/FynCA by one-way ANOVA test. WT: wild-type; YYFF: Nav1.7rG-Y1470F/Y1471F; GFP: Green Fluorescent Protein; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase.

FynCA phosphorylates Y1470 and Y1471 within the L3 of Nav1.7

Studies on Nav1.2 and Nav1.5 sodium channels identified that tyrosine residues located within the DIII-IV linker (L3) are phosphorylation sites for Fyn. The cytosolic L3 contains the key residues for sodium channel fast inactivation—IFM motif and is highly conserved in amino acid sequence among human VGSC isoforms (Figure 3(b)). We therefore examined the possibility that the two tyrosine residues located within the L3 of Nav1.7, Y1470, and Y1471 were phosphorylated by Fyn kinase. Because Y1470 and Y1471 are located at the middle of the recognition region for PanNav antibody (CTEEQKKYYNAMKKLGSKK), substitution of those residues impaired the binding of PanNav antibody to mutant channels (data not shown). Therefore, an eGFP-fused Nav1.7 expression construct—Nav1.7r-eGFP (hereinafter referred to as Nav1.7rG) was used for this experiment, with corresponding substitution of PanNav with anti-GFP antibody. Expression constructs carrying the desired mutations—Y1470F, Y1471F, or both (referred to as YYFF) were generated by site-directed mutagenesis. The expression constructs of WT or mutant channels were transiently cotransfected with FynCA or FynDN in HEK 293 cells. Cell lysates were collected at 36 h after transfection, total protein expression and tyrosine phosphorylation state of Nav1.7 channels were examined as described in “Methods” section. The protein expressions were similar among WT, Y1470F, and Y1471F when transfected with FynDN, while the expression of YYFF double mutant was reduced (Figure 3(c)). FynCA increased protein expression of all four channels, with the largest change seen in Y1471F. FynCA elevated phosphotyrosine level of transiently transfected WT channels, consistent with what we observed in HEK-Nav1.7st cells. In contrast, mutations dramatically impaired tyrosine phosphorylation of mutant channels (Figure 3(d)). FynCA-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of mutant channels was presented as the percentage of that of WT channels. All three mutations dramatically impaired tyrosine phosphorylation of Nav1.7, with YYFF double mutant exhibiting the lowest phosphorylation level (Figure 3(d)). Our results demonstrate that Y1470 and Y1471 within the L3 are phosphorylation sites for Fyn kinase.

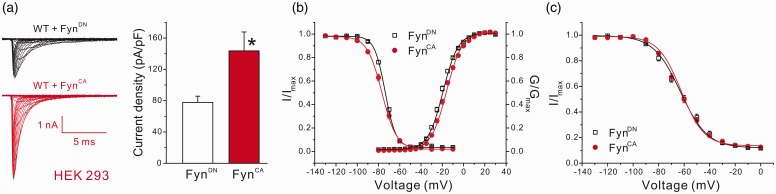

FynCA increased current density and slightly altered gating properties of Nav1.7 channels in HEK 293 cells, substituting both Fyn phosphorylation sites dramatically impaired sodium currents despite normal membrane expression of mutant channels

Fyn-mediated phosphorylation altered gating properties of Nav1.2 and Nav1.5 channels. To examine whether Fyn kinase also modulates the biophysical properties of Nav1.7 channels, Nav1.7r constructs were transiently transfected with FynCA or FynDN in HEK 293 cells, and whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed on transfected cells 24 h after transfection. Representative voltage-gated sodium currents recorded from cells expressing FynDN and FynCA are shown in Figure 4(a). Consistent with increased Nav1.7 expression on the cell surface, cells expressing FynCA produced significantly larger Nav1.7 currents (144 ± 24 pA/pF, n = 19, p < 0.05 vs. FynDN, Mann–Whitney test) than cells expressing FynDN (78 ± 8 pA/pF, n = 21) (Figure 4(a)). FynCA also caused small though statistically significant shift in Nav1.7 activation and steady-state fast inactivation (Table 2, Figure 4(b)). The midpoint of slow inactivation was not affected by FynCA despite a small change in the slope (Table 2, Figure 4(c)).

Figure 4.

FynCA increased current density and caused mild changes in Nav1.7 gating properties in HEK 293 cells. (a) Coexpression of FynCA increased current density of Nav1.7 in HEK 293 cells. The left panel shows the representative raw sodium currents of Nav1.7r cotransfected with FynCA or FynDN, and the right panel is the histogram of mean current densities. Data are presented as means ± SE, *p < 0.05, FynCA versus FynDN by Mann–Whitney test. (b) The activation and steady-state fast inactivation curves of Nav1.7 channels. Expression of FynCA caused a depolarized shift in activation but a hyperpolarized shift in steady-state fast inactivation of Nav1.7 channels in HEK 293 cells. (c) The steady-state slow inactivation of Nav1.7 channels. FynCA had little effect on slow inactivation of Nav1.7 in HEK 293 cells. Data are presented as means ± SE. HEK: Human Embryonic Kidney; WT: wild type.

Table 2.

The effects of Fyn kinase on the gating properties of Nav1.7 channels transiently transfected in HEK 293 and ND7/23 cells.

|

Activation |

Steady-state fast inactivation |

Steady-state slow inactivation |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1/2,act | k | n | V1/2,fast | k | n | V1/2, slow | k | Rresist (%) | n | |

| Nav1.7r-WT, HEK 293 | ||||||||||

| + FynDN | −20.6 ± 0.6 | 7.18 ± 0.15 | 16 | −74.0 ± 0.4 | 5.45 ± 0.13 | 16 | −63.1 ± 1.3 | 10.4 ± 0.4 | 12.6 ± 1.0 | 10 |

| + FynCA | −17.2 ± 0.6* | 7.34 ± 0.19 | 12 | −76.7 ± 0.9* | 7.26 ± 0.22* | 12 | −62.9 ± 1.6 | 11.9 ± 0.2* | 11.0 ± 0.9 | 8 |

| Nav1.7rG-WT, ND7/23 | ||||||||||

| + FynDN | −15.2 ± 0.9 | 7.56 ± 0.19 | 14 | −74.7 ± 1.4 | 6.56 ± 0.20 | 13 | −59.1 ± 0.7 | 11.2 ± 0.4 | 22.9 ± 1.8 | 12 |

| + FynCA | −20.4 ± 2.1* | 7.62 ± 0.40 | 11 | −82.8 ± 2.6* | 6.81 ± 0.31 | 11 | −65.9 ± 1.8* | 11.4 ± 0.7 | 16.4 ± 2.5* | 9 |

| Nav1.7rG-YYFF, ND7/23 | ||||||||||

| + FynDN | −15.0 ± 1.3 | 8.37 ± 0.25 | 10 | −74.5± 1.8 | 7.99 ± 0.34# | 10 | −60.9 ± 1.9 | 10.0 ± 0.5 | 16.6 ± 2.0# | 9 |

| + FynCA | −19.1 ± 1.2* # | 8.10 ± 0.33 | 15 | −82.4 ± 1.4* # | 8.69 ± 0.21# | 13 | −64.2 ± 0.9# | 11.0 ± 0.3 | 12.0 ± 1.1# | 14 |

Note: * p < 0.05 FynCA vs corresponding FynDNcontrol, two-sample student t test (HEK 293 cells) or one-way ANOVA test (ND7/23 cells); # p < 0.05 Nav1.7rG-YYFF/FynDN or Nav1.7rG-YYFF/FynCA vs Nav1.7rG-WT/FynDN, one-way ANOVA test (ND7/23 cells).

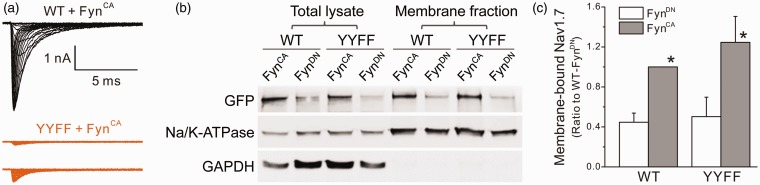

Since substitution of tyrosine residues (Y1470 and Y1471) dramatically impaired Fyn-mediated Nav1.7 phosphorylation, we examined the effect of FynCA on the biophysical properties of YYFF mutant channel. The Nav1.7rG-YYFF construct was cotransfected with FynCA or FynDN, and voltage-gated sodium currents were recorded. Surprisingly, none of the HEK 293 cells transfected with YYFF mutant plus FynDN produced sodium currents over 500 pA. For cells expressing FynCA, 3 of 18 cells produced sodium currents over 500 pA, with the maximal current amplitude around 650 pA (Figure 5(a)). To explore whether YYFF mutation impacted protein insertion into the plasma membrane and thus reducing sodium currents of mutant channels, we utilized a surface biotinylation assay. Figure 5(b) and (c) shows the representative Western blot image and the histogram of mean membrane expression of WT and mutant channels obtained from four experiments, respectively. Consistent to the increased current density (Figure 4(a)), FynCA doubled the level of membrane-bound WT channels in HEK 293 cells (WT/FynDN: 0.45 ± 0.09, normalized to the surface expression of WT/FynCA). Surprisingly, the YYFF mutant channels exhibited similar membrane expressions as WT channels (YYFF/FynCA: 1.25 ± 0.26, YYFF/FynDN: 0.50 ± 0.19) (Figure 5(b) and (c)), indicating that membrane trafficking and insertion in the plasma membrane were not the reasons for the reduced mutant currents in HEK 293 cells.

Figure 5.

Substitution of both tyrosine residues (Nav1.7rG-YYFF) dramatically reduced sodium currents recorded in HEK 293 cells, despite similar surface expressions between WT and mutant channels. (a) The representative sodium currents recorded from HEK 293 cells transfected by Nav1.7rG WT or YYFF plus FynCA. Cells expressing Nav1.7rG-WT channels generated decent sodium currents (representative raw traces in black), while sodium currents recorded from HEK 293 cells expressing Nav1.7rG-YYFF were extremely small (representative raw sodium currents of YYFF mutant recorded from two transfected HEK293 cells were shown in purple). (b) The representative Western blot image of total expression and cell surface expression of WT and YYFF mutant channels transiently transfected in HEK 293 cells with FynCA or FynDN. FynCA elevated the total and surface expressions of both WT and mutant channels, and the cell surface expression of YYFF mutant was not different to that of WT channels. (c) The histogram of membrane-bound WT and YYFF mutant channels expressed in HEK 293 cells. The surface expression level of WT channels cotransfected with FynCA was set as 1; and the membrane expression of WT/FynDN, YYFF/FynDN, and YYFF/FynCA was 0.45 ±0.09, 0.50 ± 0.19, and 1.25 ± 0.26, respectively. Data are obtained from four experiments and presented as mean ± SE, *p < 0.05 WT/FynCA or YYFF/FynCA versus corresponding channels cotransfected with FynDN by one-way ANOVA test. WT: wild type; YYFF: Nav1.7rG-Y1470F/Y1471F; GFP: Green Fluorescent Protein; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase.

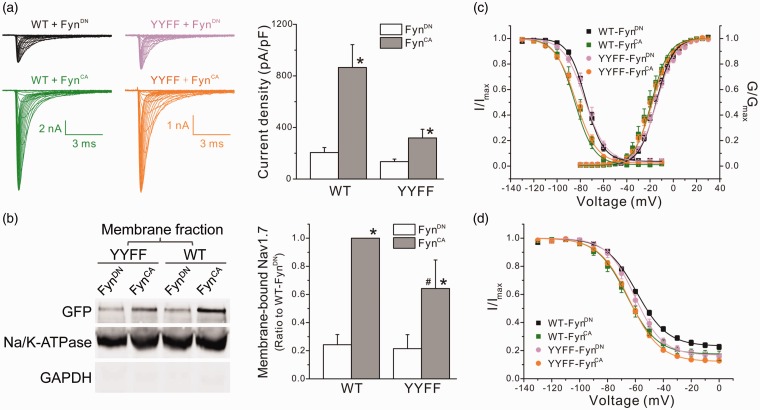

FynCA differentially altered Nav1.7 expression and gating properties in ND7/23 cells, indicating the presence of additional modulation(s) of Nav1.7 by Fyn kinase in neuronal cells

Nav1.7 is preferentially expressed in peripheral neurons and may undergo neuronal-specific modulations. To examine the possibility of cell-specific effects, we used ND7/23 cells, an immortalized hybrid neuronal cell line derived from rat DRG and mouse neuroblastoma, as a comparator. Because ND7/23 cells express endogenous TTX-sensitive sodium channels, TTX (300 nM) was added into the extracellular solution to isolate transfected Nav1.7rG currents from endogenous sodium currents. Large voltage-gated sodium currents were recorded from transfected ND7/23 cells (Figure 6(a)), with the peak current amplitude of some cells beyond the scale of accurate measurement. Eight of 30 cells transfected with Nav1.7rG WT plus FynCA, and 2 of 23 cells transfected with WT plus FynDN, produced currents over 20 nA, and were excluded from data analysis. Cells expressing WT/FynCA produced larger sodium currents, with the mean current density four times of that recorded from cells transfected with WT/FynDN (WT/FynCA: 865 ± 177 pA/pF, n = 22, p < 0.05 vs. WT/FynDN: 205 ± 39 pA/pF, n = 21, Mann–Whitney test) (Figure 6(a)). Unlike HEK 293 cells, ND7/23 cells transfected with YYFF mutant produced decent sodium currents. The mean current density was 135 ± 19 pA/pF (n = 13) for cells expressing YYFF/FynDN and a significantly larger current density for YYFF/FynCA (319 ± 67 pA/pF, n = 19, p < 0.05 vs. YYFF/FynDN, Mann–Whitney test) (Figure 6(a)). The cell surface biotinylation assay revealed similar membrane expression between WT and mutant channels when coexpressed with FynDN (WT/FynDN: 0.24 ±0.07; YYFF/FynDN: 0.21 ± 0.10, normalized to the surface expression of WT/FynCA) (Figure 6(b) and (c)). Consistent to the larger sodium currents recorded in ND7/23 cells expressing WT/FynCA, the level of membrane-bound sodium channels in cells transfected with WT/FynCA was four times of that in cells expressing WT/FynDN. However, unlike HEK 293 cells which exhibited similar surface expression between WT and YYFF mutant, the expression of membrane-bound mutant channels in ND7/23 cells expressing FynCA was less than that of WT channels (YYFF/FynCA: 0.64 ± 0.20, p < 0.05 vs. WT/FynCA, one-way ANOVA) (Figure 6(b) and (c)), which may partially contribute to the relatively small currents of mutant channels in ND7/23 cells expressing YYFF/FynCA. The difference in FynCA-mediated modulations in current density and membrane expression between sodium channels expressed in ND7/23 and in HEK 293 cells indicates the presence of additional modulation(s) of Nav1.7 channels in ND7/23 cells, which partially rescued the impaired sodium currents of mutant channels in HEK 293 cells.

Figure 6.

FynCA modulated the biophysical properties of Nav1.7 in ND7/23 cells through mechanisms unrelated to phosphorylation of Y1470 and Y1471. (a) The left panels shows the representative WT or YYFF mutant currents recorded from ND7/23 cells cotransfected with FynCA or FynDN. Cells expressing WT channels generated relative larger sodium currents when compared with cells expressing mutant channels. The right panel is the histogram of the mean current densities. FynCA increased current densities of both WT and YYFF mutant channels. Data are presented as means ± SE, *p < 0.05 versus corresponding FynDN control by Mann–Whitney test. (b) The left panel shows the representative Western blot image of membrane expression of WT and YYFF mutant channels cotransfected with FynCA or FynDN in ND7/23 cells. The right panel is the histogram of mean surface expressions of WT and YYFF channels normalized by the membrane expression level of WT/FynCA. Data are obtained from six experiments and presented as mean ± SE, *p < 0.05 WT/FynCA versus WT/FynDN or YYFF/FynCA versus YYFF/FynDN; #p < 0.05, YYFF/FynCA versus WT/FynCA, by one-way ANOVA test. (c) The activation and steady-state fast inactivation curves of WT and mutant channels cotransfected with FynCA or FynDN. FynCA shifted both activation and fast inactivation curves of WT channels to the hyperpolarizing direction in ND7/23 cells, which was remained in mutant channels. Data are presented as means ± SE. (d) The steady-state slow inactivation of WT and YYFF mutant channels. FynCA shifted the slow inactivation curve of both channels to the hyperpolarizing direction and reduced the percentage of channels that are resistant to slow inactivation (Rresist). Data are presented as means ± SE. WT: wild type; YYFF: Nav1.7rG-Y1470F/Y1471F; GFP: Green Fluorescent Protein; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase.

The relatively large currents of YYFF mutant expressed in ND7/23 cells allow us to analyze the gating properties of mutant channels. In ND7/23 cells, FynCA shifted both activation and fast inactivation curves of WT channels to hyperpolarizing direction (Table 2, Figure 6(c)). In addition, FynCA enhanced the steady-state slow inactivation of Nav1.7 channels, causing ∼ −6.8 mV shift in the midpoint of slow inactivation (V1/2,slow) and reducing the percentage of channels resistant to slow inactivation (WT/FynCA: Rresist = 16.4 ± 2.5%, n = 9, p < 0.05 vs. WT/FynDN: Rresist = 22.9 ± 1.8%, n = 12, one-way ANOVA) (Table 2, Figure 6(d)). Substitution for both Fyn phosphorylation sites had little effect on Fyn-mediated modulation of Nav1.7 gating properties. The midpoints of activation, steady-state fast and slow inactivation of YYFF mutant, were similar to those of WT channels when cotransfected with FynDN (Figure 6(c) and (d)), except for the fraction of channels resistant to slow inactivation (Rresist) which was smaller than that of WT channels (Table 2, Figure 6(d)). FynCA caused similar shifts in activation and inactivation of the YYFF mutant channels expressed in ND7/23 cells as it did for WT channels (Table 2, Figure 6(c) and (d)), suggesting that FynCA modulated Nav1.7 gating through mechanisms independent of Y1470 and Y1471 phosphorylation.

Discussion

In this study, we show that sodium channel Nav1.7 is regulated by Fyn kinase and identify two phosphorylation sites in the L3 of Nav1.7. Whole-cell recordings revealed cell background-specific modulation of Nav1.7 by FynCA, with more potent effect on the biophysical properties of Nav1.7 channels in ND7/23 cells than in HEK 293 cells. Substitution of both tyrosine residues diminished FynCA-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of Nav1.7, reduced current density, but had little effect on FynCA-induced shifts in channel gating. Taken together, our results demonstrate that Nav1.7 is a substrate for Fyn kinase, and FynCA modulates Nav1.7 expression and gating properties through different mechanisms independent of the phosphorylation sites within the L3 of Nav1.7 channels.

FynCA-mediated upregulation of Nav1.7 expression, together with the hyperpolarized shift in channel activation curve in ND7/23 cells, is expected to elevate neuronal excitability. In contrast, the enhanced fast inactivation and slow inactivation of Nav1.7 by FynCA in ND7/23 cells would attenuate neuronal firing by reducing the availability of functional channels. Computer simulations have previously shown that the hyperpolarizing shift in channel activation in mutant Nav1.7 channels has a dominant effect on neuronal excitability.24 In addition, the modulation of Nav1.7 channels by Fyn in DRG neurons may not be the same to what we observed in ND7/23 cells. Future investigation is required to determine the comprehensive impact of Fyn kinase on Nav1.7 channels and the neuronal excitability in DRG neurons.

The N-terminus of Fyn kinase contains residues that undergo myristoylation and palmitoylation, which targets Fyn to lipid rafts.25 This kind of distribution enables efficient and specific signal transduction by recruiting relevant proteins together while segregating molecules that may impede those signaling processes. For example, sodium channel β1 subunit contains a putative palmitoylation site. In cultured cerebellar granule cells, β1 subunit mediates neurite outgrowth through activation of Fyn kinase in lipid rafts.26 Nav1.8, another key sodium channel in nociception, has been shown to be associated with lipid rafts along the sciatic nerve as well as in DRG neurons, and dissociation between Nav1.8 and lipid rafts impaired neuronal excitability.27 It is not known, however, whether Nav1.7 resides within lipid rafts. It is possible that Nav1.7 channels within lipid rafts may differ in channel biophysical properties than channels in nonraft membranes because of the assembly of channel complexes with different components, which might activate different cellular signaling pathways and therefore result in different physiological or pathological functions.

Our study identified that Y1470 and Y1471, localized within the L3 of Nav1.7, are phosphorylation sites for Fyn kinase. The L3 linker contains the IFM motif that is critical for sodium channel fast inactivation and is highly conserved among human VGSCs. Studies in Nav1.2 and Nav1.5 have shown that the corresponding tyrosine residues are involved in Fyn-mediated regulation.18,19 Substitution of both tyrosine residues by phenylalanine had little effect on Nav1.5 biophysical properties in transfected tsA201 cells.28 Surprisingly, phenylalanine substitution for the corresponding tyrosines in Nav1.7, YYFF, dramatically impaired channel’s ability to produce sodium currents in HEK 293 cells. Since the cell surface expression of mutant channels was similar to that of WT channels, membrane trafficking of mutant channels cannot be the cause for reduced sodium currents. Interestingly, relatively large sodium currents were recorded from mutant channels transfected in ND7/23 cells, demonstrating that YYFF mutant channels are functional. Therefore, the defect in current production in HEK 293 cells may be due to the impaired open probability of YYFF channels, which was partially rescued by additional modulation(s) of Nav1.7 channels when expressed in ND7/23 cells.

Derived from rat DRG neurons, ND7/23 cells may possess molecules or signaling pathways specific to neurons, which partially rescued the defect of YYFF mutant in current generation compared to the fibroblast cells of the expression system (HEK 293 cell line). Phenylalanine substitutions had little effect on Fyn-mediated shifts in Nav1.7 gating properties, suggesting a mechanism unrelated to the phosphorylation of those two residues. The effects of double mutation on Fyn-mediated modulation of Nav1.2 and Nav1.5 were not reported. However, substitution of single tyrosine residue (Y1497F, Y1498F in Nav1.2, and Y1495F in Nav1.5) diminished or even abolished Fyn-induced shifts in channel inactivation, indicating an association between phosphorylation of those residues and Fyn-mediated shifts in fast inactivation of Nav1.2 and Nav1.5.18,19 The different effects of Fyn kinase on biophysical properties of Nav1.2, Nav1.5, and Nav1.7 sodium channels suggest an isoform-specific modulation of sodium channels by Fyn. It will thus be important to examine the effects of Fyn on other sodium channel isoforms expressed in DRG neurons in order to have a comprehensive understanding of the possible roles of Fyn-mediated modulation of sodium channels in nociception.

Nav1.7 is a key molecule in nociception, and its modulation by Fyn kinase is expected to influence neuronal excitability and thus to modulate pain perception. Fyn kinase is widely expressed in the nervous system, including DRG neurons.29 However, the function of Fyn kinase in DRG neurons has not been fully understood. Fyn kinase is essential for the NCAM-dependent neurite outgrowth of cultured DRG neurons.30 In SHRSP5/Dmcr rats, repeated cold stress (RCS) caused an upregulation of Fyn gene in DRGs, indicating a possible role of Fyn in RCS-induced hyperalgesia.31 We showed here that FynCA, a constitutively active Fyn variant, increased Nav1.7 protein levels and current density and enhanced channel’s activation and inactivation in the DRG-derived ND7/23 cell line, suggesting a possible proexcitatory effect on neuronal excitability. A recent study, however, suggested that Fyn-mediated phosphorylation of CRMP2 prevents SUMOylation of CRMP2, which enhances internalization of Nav1.7 channels and reduces TTX-sensitive current density in transfected DRG neurons, thereby reducing neuronal excitability.20 It is unclear what causes the different effects of activation of Fyn kinase on the expression levels, current density, and gating of Nav1.7 in our study and in the study by Dustrude et al.20 One possible explanation is different experimental conditions, we used constitutively active FynCA (ensured activation of Fyn kinase activity) and catalytically inactive FynDN in our study, while Dustrude et al. used CRMP2 phosphorylation-defective constructs, wildtype Fyn kinase (required autophosphorylation for optimal activity) and FynDN. It is not unreasonable to conclude that the net outcome of Fyn kinase activation in DRG neurons will be a balance of the effects of direct modulation of Nav1.7 increasing the current density and altering channel gating in a pro-excitatory manner, and the inhibition of CRMP2 SUMOylation and increasing internalization of Nav1.7, an antiexcitatory effect.

In summary, we demonstrate that Nav1.7 is subject to Fyn-mediated modulation. Activation of Fyn kinase increases Nav1.7 expression and alters the biophysical properties of Nav1.7 channels in a cell background-specific manner. Drugs targeting the PTMs of Nav1.7 might prove to be an alternative target for pain management.9 Future investigations are required to identify the underlying mechanisms and to explore the effect of Fyn-mediated regulation of sodium channels on neuronal excitability in DRG neurons. Nevertheless, our study reveals a novel regulation of Nav1.7 channels by Fyn, which may provide new insights to the molecular mechanisms of nociception and contribute to the development of therapeutic approaches in pain management.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Fadia Dib-Hajj and Ms Palak Shah (Yale University) for their technical assistance with this project.

Author contributions

X Cheng designed the project; Y Li, T Zhu, H Yang, and X Cheng performed experiments, collected and analyzed data; X Cheng, SD Dib-Hajj, SG Waxman, Y Yu, and TL Xu interpreted results and wrote manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by grants from Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (15ZR1424300, to XC), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31671051, to XC), the National Program on Key Basic Research Project of China (2014CB910300, to TLX; 2014CB910302, to YY), the Rehabilitation Research and Development Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs (to SGW and SDD-H), and the Erythromelalgia Association (to SGW and SDD-H).

References

- 1.Catterall WA. Voltage-gated sodium channels at 60: structure, function and pathophysiology. J Physiol (Lond) 2012; 590: 2577–2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dib-Hajj SD, Yang Y, Black JA, Waxman SG. The NaV1.7 sodium channel: from molecule to man. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013; 14: 49–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herzog RI, Cummins TR, Ghassemi F, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG. Distinct repriming and closed-state inactivation kinetics of Nav1.6 and Nav1.7 sodium channels in mouse spinal sensory neurons. J Physiol 2003; 551: 741–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox JJ, Reimann F, Nicholas AK, Thornton G, Roberts E, Springell K, Karbani G, Jafri H, Mannan J, Raashid Y, Al-Gazali L, Hamamy H, Valente EM, Gorman S, Williams R, McHale DP, Wood JN, Gribble FM, Woods CG. An SCN9A channelopathy causes congenital inability to experience pain. Nature 2006; 444: 894–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dib-Hajj SD, Geha P, Waxman SG. Sodium channels in pain disorders: pathophysiology and prospects for treatment. Pain 2017; 158: S97–S107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao L, MaDonnell A, Nitzsche A, Alexandrou A, Saintot PP, Loucif AJ, Brown AR, Young G, Mis M, Randall A, Waxman SG, Stanley P, Kirby S, Tarabar S, Gutteridge A, Butt R, McKernan RM, Whiting P, Ali Z, Bilsland J, Stevens E. Pharmacological reversal of a pain phenotype in iPSC-derived sensory neurons and patients with inherited erythromelalgia. Sci Transl Med 2016; 8: 335ra356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg YP, Price N, Namdari R, Cohen CJ, Lamers MH, Winters C, Price J, Young CE, Verschoof H, Sherrington R, Pimstone SN, Hayden MR. Treatment of Na(v)1.7-mediated pain in inherited erythromelalgia using a novel sodium channel blocker. Pain 2012; 153: 80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zakrzewska JM, Palmer J, Morisset V, Giblin GM, Obermann M, Ettlin DA, Cruccu G, Bendtsen L, Estacion M, Derjean D, Waxman SG, Layton G, Gunn K, Tate S. Safety and efficacy of a Nav1.7 selective sodium channel blocker in patients with trigeminal neuralgia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised withdrawal phase 2a trial. Lancet Neurol 2017; 16: 291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laedermann CJ, Abriel H, Decosterd I. Post-translational modifications of voltage-gated sodium channels in chronic pain syndromes. Front Pharmacol 2015; 6: 263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan Z-Y, Priest BT, Krajewski JL, Knopp KL, Nisenbaum ES, Cummins TR. Protein kinase C enhances human sodium channel hNav1.7 resurgent currents via a serine residue in the domain III-IV linker. FEBS Lett 2014; 588: 3964–3969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stamboulian S, Choi J-S, Ahn H-S, Chang Y-W, Tyrrell L, Black JA, Waxman SG, Dib-Hajj SD. ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylates sodium channel Na(v)1.7 and alters its gating properties. J Neurosci 2010; 30: 1637–1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vijayaragavan K, Boutjdir M, Chahine M. Modulation of Nav1.7 and Nav1.8 peripheral nerve sodium channels by protein kinase A and protein kinase C. J Neurophysiol 2004; 91: 1556–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong S, Morrow TJ, Paulson PE, Isom LL, Wiley JW. Early painful diabetic neuropathy is associated with differential changes in tetrodotoxin-sensitive and -resistant sodium channels in dorsal root ganglion neurons in the rat. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 29341–29350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Persson A-K, Gasser A, Black JA, Waxman SG. Nav1.7 accumulates and co-localizes with phosphorylated ERK1/2 within transected axons in early experimental neuromas. Exp Neurol 2011; 230: 273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schenone S, Brullo C, Musumeci F, Biava M, Falchi F, Botta M. Fyn kinase in brain diseases and cancer: the search for inhibitors. Curr Med Chem 2011; 18: 2921–2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abe T, Matsumura S, Katano T, Mabuchi T, Takagi K, Xu L, Yamamoto A, Hattori K, Yagi T, Watanabe M, Nakazawa T, Yamamoto T, Mishina M, Nakai Y, Ito S. Fyn kinase-mediated phosphorylation of NMDA receptor NR2B subunit at Tyr1472 is essential for maintenance of neuropathic pain. Eur J Neurosci 2005; 22: 1445–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu YN, Yang X, Suo ZW, Xu YM, Hu XD. Fyn kinase-regulated NMDA receptor- and AMPA receptor-dependent pain sensitization in spinal dorsal horn of mice. Eur J Pain 2014; 18: 1120–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahern CA, Zhang J-F, Wookalis MJ, Horn R. Modulation of the cardiac sodium channel NaV1.5 by Fyn, a Src family tyrosine kinase. Circ Res 2005; 96: 991–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beacham D, Ahn M, Catterall WA, Scheuer T. Sites and molecular mechanisms of modulation of Na(v)1.2 channels by Fyn tyrosine kinase. J Neurosci 2007; 27: 11543–11551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dustrude ET, Moutal A, Yang X, Wang Y, Khanna M, Khanna R. Hierarchical CRMP2 posttranslational modifications control NaV1.7 function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016; 113: E8443–E8452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummins TR, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG. Electrophysiological properties of mutant Nav1.7 sodium channels in a painful inherited neuropathy. J Neurosci 2004; 24: 8232–8236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laedermann CJ, Syam N, Pertin M, Decosterd I, Abriel H. β1- and β3- voltage-gated sodium channel subunits modulate cell surface expression and glycosylation of Nav1.7 in HEK293 cells. Front Cell Neurosci 2013; 7: 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kramer-Albers EM, White R. From axon-glial signalling to myelination: the integrating role of oligodendroglial Fyn kinase. Cell Mol Life Sci 2011; 68: 2003–2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheets PL, Jackson JO, Waxman SG, Dib-Hajj SD, Cummins TR. A Nav1.7 channel mutation associated with hereditary erythromelalgia contributes to neuronal hyperexcitability and displays reduced lidocaine sensitivity. J Physiol 2007; 581: 1019–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gottlieb-Abraham E, Gutman O, Pai GM, Rubio I, Henis YI. The residue at position 5 of the N-terminal region of Src and Fyn modulates their myristoylation, palmitoylation, and membrane interactions. Mol Biol Cell 2016; 27: 3926–3936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brackenbury WJ, Davis TH, Chen C, Slat EA, Detrow MJ, Dickendesher TL, Ranscht B, Isom LL. Voltage-gated Na+ channel beta1 subunit-mediated neurite outgrowth requires Fyn kinase and contributes to postnatal CNS development in vivo. J Neurosci 2008; 28: 3246–3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pristera A, Baker MD, Okuse K. Association between tetrodotoxin resistant channels and lipid rafts regulates sensory neuron excitability. PloS One 2012; 7: e40079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Leary ME, Chen LQ, Kallen RG, Horn R. A molecular link between activation and inactivation of sodium channels. J Gen Physiol 1995; 106: 641–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmutzler BS, Roy S, Pittman SK, Meadows RM, Hingtgen CM. Ret-dependent and Ret-independent mechanisms of Gfl-induced sensitization. Mol Pain 2011; 7: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beggs HE, Soriano P, Maness PF. NCAM-dependent neurite outgrowth is inhibited in neurons from Fyn-minus mice. J Cell Biol 1994; 127: 825–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kozaki Y, Umetsu R, Mizukami Y, Yamamura A, Kitamori K, Tsuchikura S, Ikeda K, Yamori Y. Peripheral gene expression profile of mechanical hyperalgesia induced by repeated cold stress in SHRSP5/Dmcr rats. J Physiol Sci 2015; 65: 417–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]