Abstract

Despite the abundance, ubiquity and impact of environmental viruses, their inherent genomic plasticity and extreme diversity pose significant challenges for the examination of bacteriophages on Earth. Viral metagenomic studies have offered insight into broader aspects of phage ecology and repeatedly uncover genes to which we are currently unable to assign function. A combined effort of phage isolation and metagenomic survey of Chicago’s nearshore waters of Lake Michigan revealed the presence of Pbunaviruses, relatives of the Pseudomonas phage PB1. This prompted our expansive investigation of PB1-like phages. Genomic signatures of PB1-like phages and Pbunaviruses were identified, permitting the unambiguous distinction between the presence/absence of these phages in soils, freshwater and wastewater samples, as well as publicly available viral metagenomic datasets. This bioinformatic analysis led to the de novo assembly of nine novel PB1-like phage genomes from a metagenomic survey of samples collected from Lake Michigan. While this study finds that Pbunaviruses are abundant in various environments of Northern Illinois, genomic variation also exists to a considerable extent within individual communities.

Keywords: bacteriophage, Pbunaviruses, Pseudomonas phage PB1, uncultivated phage genomes

1. Introduction

Research on bacterial viruses (bacteriophages) has progressed remarkably over the last 100 years [1], and phages are now regarded as ubiquitous engineers of bacterial community structure and metabolism [2,3,4,5]. Despite this, the quantity of phage-related information stored in biological sequence repositories is meager. To date there are less than 2000 distinct species represented in GenBank, which is largely a reflection of the many challenges of working with phages in the laboratory [6]. High-throughput sequencing platforms have been instrumental in advancing current understanding of microbial community diversity [7]. Viral metagenomic studies of phage communities have significantly improved our ability to examine and understand viral diversity in the wild [8,9,10]. Meta-analyses have expanded the viral catalogue postulating new branches of the evolutionary tree for viruses [11,12,13]. Furthermore, metagenomics has permitted a glimpse into viral biogeography (e.g., [11,14,15,16]; see review [17]).

Methods for molecular [18,19,20] and computational [21,22,23] assessment of viral communities are being continuously developed and refined. The aforementioned methods, as well as other approaches employed in studies (e.g., clustering contigs based upon nucleotide usage and/or coverage (see review [24]), have resulted in the generation of numerous complete or near complete genomes of uncultivated prokaryotes [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37] and viruses [11,28,30,34,38,39,40]. Additionally, complete phage genomes have been assembled from viral metagenomes through manual curation and BLAST searches [11,15,33,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. Given the advances in DNA sequencing technology throughput, high-quality genomes derived solely from metagenomes are anticipated to become commonplace, challenging the way in which we classify new viruses [49]. Nevertheless, with the recent assemblies of the largest phage genome to date [11] and the first genomes of freshwater Actinobacteria-infecting phages [48], metagenomics has greatly expanded our understanding of phage genomic diversity.

The study presented here was initially informed by our previous work, in which four Pseudomonas aeruginosa-infecting PB1-like phages (genus: Pbunavirus) were isolated from the nearshore waters of Lake Michigan [50]. Other members of this genus have been isolated from freshwater, sewage and soil and predominately infect Pseudomonas species [51]. While Pseudomonas phage PB1 is the type species for Pbunavirus, over 40 members of this genus have been suggested on the basis of homology assessments [52]. Currently there are 31 Pbunavirus species with RefSeq genomes publicly available. These dsDNA viruses have a genome ~66 Kbp in length with 88 to 97 predicted coding regions. Given its lack of a recognizable integrase, it is presumed to be obligately lytic [53]. Recently, PB1-related phages have been isolated from sewage samples in Germany [54], Poland [55], and Portugal [56], wastewater in France [57], and river water in Brazil [58].

While Pseudomonas is a truly multi-faceted microorganism and is generally regarded as having a high presence in the aquatic environment, it is not a dominant member of freshwater habitats [59,60], from which we previously isolated four PB1-like phages [50]. Nevertheless, Pbunaviruses have been found in a variety of ecological niches across the globe [51,54,55,56,57,58]. This parallels observations for several marine phages that have been found across large geographic distances [11,13,61]. This led us to hypothesize that Pbunaviruses are widespread in nature. Integrating molecular and computational methods, the presence and abundance of PB1-like phages was assessed in soil, freshwater, and sewage samples.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

Samples were collected from three bodies of freshwater: (1) Lake Defiance (42°19′19.4″ N 88°13′37.5″ W) in Moraine Hills State Park (McHenry, IL, USA) is an isolated lake/bog; (2) Grass Lake/Fox River (42°26′46.4″ N 88°10′50.2″ W) in the Chain O’Lakes State Park (Spring Grove, IL, USA) is located within a large interconnected chain of lakes and waterways; and (3) Lake Michigan’s Hartigan Beach Park (42°00′06.3″ N 87°39′22.3″ W). Two biological replicates, each 4 L, were collected from Lake Defiance and Grass Lake in August 2015. Five temporal replicates, each 4 L, were collected from the Hartigan Beach site (June–August 2015). Additionally, four samples of activated sludge, in triplicate (50 mL) were collected from the aeration basins of O’Brien Water Reclamation Plant (Skokie, IL, USA) in October 2014. Four replicate soil samples (50 g) were collected from the Loyola Lakeshore campus in August 2015. Each sample of activated sludge and soil were diluted with 500 mL phosphate buffered saline (PBS), agitated in a shaking incubator overnight. Sample locations are shown in Figure S1.

2.2. Viral DNA Extraction

Virus-like particles were purified from the collected samples through successive filtration: initially, through a sterile 0.45 μm bottle-top cellulose acetate membrane filter (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) to remove plant matter, sand, debris, and eukaryotic cells, then through a 0.22 μm polyethersulfone membrane filter (MO BIO Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to remove bacterial cells. The filtrate was then filtered and concentrated using a 0.10 μm polypropylene filter (EMD Millipore Corp, Billerica, MA, USA) with the Labscale™ tangential flow filtration (TFF) system (EMD Millipore Corp, Billerica, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was extracted from the TFF fraction using the MO BIO Laboratories UltraClean® DNA Isolation Kit (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The protocol recommended by the manufacturer was followed with the exception of an additional heat treatment at 70 °C for 20 min prior to initial vortexing.

2.3. PCR Amplification and Amplicon Analysis

PCR primers were designed to target conserved regions among the Pbunaviruses within the DNA of the collected samples. Primers and their expected amplicons (within the PB1 genome, GenBank: NC_011810) were queried against the nr/nt database. Five primer pairs were selected given their specificity for Pbunaviruses (Table 1). PCR primers were obtained from Eurofins MWG (Louisville, KY, USA). Thermal cycling conditions were designed based upon the individual primer pair’s Tm and expected amplicon size. PCR amplicons were purified (E.Z.N.A.® Cycle Pure Kit, Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA) and sequenced in both directions via Sanger sequencing (Genewiz, South Plainfield, NJ, USA). Consensus sequences were queried via BLASTn. Sequences were aligned in Geneious, and consensus sequences were assessed for phylogenetic relatedness, visualized via a neighbor-joining tree created with the Geneious Tree Builder tool (v 8.0.5, Biomatters Limited, Auckland, NZ) using the Jukes-Cantor distance model with bootstrap resampling (100 replicates).

Table 1.

PCR primers used in this study. Expectation of amplification determined by querying the primer sequences via BLASTn to nr/nt database. HP = hypothetical protein.

| Primer Pair | Forward Primer (5′–3′) | Reverse Primer (3′–5′) | Annotated Coding Sequence (CDS) in Amplicon | Strains/Species Expected to Amplify |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CTACGGCCGTGCAGAC | CTCCATGTGTGGCATCC | PB1 gp10 (HP), PB1 gp11 (HP) | SPM-1, PB1, F8 |

| 2 | ACCTTCTTCGGCATCCTC | TGTGGTCACCGTATTCCA | PB1 gp23 (HP), PB1 gp24 (HP) | DL60, DL52, vB_PaeM_C1-14_Ab28, SPM-1, PB1, F8 |

| 3 | CGCCATAATAGGCTCCAA | CGAGACATTCGCTGATGA | PB1 gp55 (helicase) | SPM-1, PB1, F8 |

| 4 | ACCGACTCACGACGATGG | CGGCAAGGTGTTCGCTTA | PB1 gp68 (HP), PB1 gp69 (HP) | PB1 |

| 5 | CGTCGAGGATGCTGATGG | GGCAGGTCCGAAGGCTAC | PB1 gp84 (HP), PB1 gp85 (HP), PB1 gp86 (HP) | vB_PaeM_LS1, vB_PaeM_E215, KPP22M1, vB_PaeM_E217, NP3, phiKTN6, KPP22M3, KPP22M2, KP22, vB_Pae_PS44, LMA2, vB_PaeM_CEB_DP1, vB_PaeM_PAO1_Ab29, vB_PaeM_PAO1_Ab27, KPP12, NH-4, PB1 |

2.4. Determination of the Presence of PB1 and Pbunaviruses in Publicly Available Metagenomic Datasets

Raw sequence reads (fasta or fastq format) for publicly available viral metagenomes from freshwater, hot springs, wastewater, and soil samples were collected from the SRA database. Table S1 lists the datasets. Additional marine viromes were downloaded from the iMicrobe project (data.imicrobe.us), and datasets collected from open sea sampling expeditions, including raw read data from the Pacific Ocean Virome study [62], the Global Ocean Sampling Expedition [63], the Broad Marine Phage Sequencing Project (https://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/viral/phage/home.html), and the Ocean Viruses project [64]. For each individual sample, sequence reads were assembled using Velvet [65] with a hash size of 31. A local BLAST database was created for each dataset and again the PB1 amino acid sequences were compared via blastx.

The highest scoring hit (with respect to both sequence identity and query coverage, bitscore) for each PB1 gene and individual viral metagenome assemblage was next compared to the threshold of similarity for Pbunaviruses generated in our prior work [66]. Briefly, each PB1 gene was compared to all other Pbunavirus genomes and all non-Pbunavirus phage genomes via BLAST. Intragenus and intergenus sequence similarity scores (again assessed via the BLAST bitscore) were calculated to ascertain the “informativity” of a PB1 gene. PB1 genes exhibiting sequence similarity on par with or greater than that of its most distant Pbunavirus relative (BcepF1) were deemed “uninformative” as signatures for PB1 and Pbunavirus genomes. Each viral metagenome’s sequence similarity to PB1 informative genes are represented in the atlas as the average of the query coverage and sequence identity values.

2.5. Assembly and Annotation of Uncultivated PB1-Like Genomes

Each of the Chicago area Lake Michigan viral metagenomic datasets [67] was assembled individually using the Geneious assembler (Geneious (v 8.0.5), Biomatters Ltd., Auckland, NZ), the SPAdes assembler [68] using the “meta” flag for metagenomic samples, and the Velvet assembler [65]. Geneious assemblies repeatedly produced greater N50 scores and were selected for further analysis. Contigs of length ≥ 20 Kbp were queried against the complete nr/nt database via the BLAST web interface. Contigs returning high sequence similarity (e-value < 0.00001) to PB1 (GenBank: NC_011810) or other Pbunaviruses were investigated further. From this pool, each contig was then used as a “reference genome” to which the raw reads for individual viral metagenomic samples were mapped using Bowtie2 [69]. This additional second stage mapping process served to quantify genome coverage and in some cases extend contigs. At no time was the RefSeq PB1 genome or any other published Pbunavirus genome used to “fish” for reads: assembly to complete full genomes were generated a priori. Furthermore, in several cases the complete genome was produced during the initial assembly. All genomes were then manually inspected, and coverage was computed using BBMap (sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/). Genomes from five viral metagenomic datasets were removed from further consideration as they contained regions (≥100 bp) of low coverage (<5 paired end reads). Annotations were generated, using Geneious, according to the most recent PB1 annotation (GenBank: NC_011810), and manually inspected again. Genome sequences were deposited in GenBank, Accession numbers KT372690 through KT272698.

2.6. Comparative Genomics

The nine uncultivated Lake Michigan PB1-like genome sequences were adjusted to the same frame as the PB1 RefSeq sequence. Genome alignments were performed using the progressive Mauve algorithm [70] and visualized in Geneious. These nine genomes were compared to other available Pseudomonas-infecting Pbunavirus genomes: phages LMA2 (GenBank: NC_011166), SN (GenBank: NC_011756), 14-1 (GenBank: NC_0111703), F8 (GenBank: NC_007810), PB1 (GenBank: NC_011810), LBL3 (GenBank: NC_011165), φVader (GenBank: KT254130), φMoody (GenBank: KT254131), φHabibi (GenBank: KT254132), and φFenriz (GenBank: KT254133). A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was created for the publicly available genomes, including the four Lake Michigan isolates [50], and the nine uncultivated PB1-like genomes based upon this alignment. This tree was created with the Geneious Tree Builder tool using the Jukes-Cantor distance model with bootstrap resampling (100 replicates).

3. Results

3.1. Hunting for Pbunaviruses in Soil, Freshwater and Activated Sludge

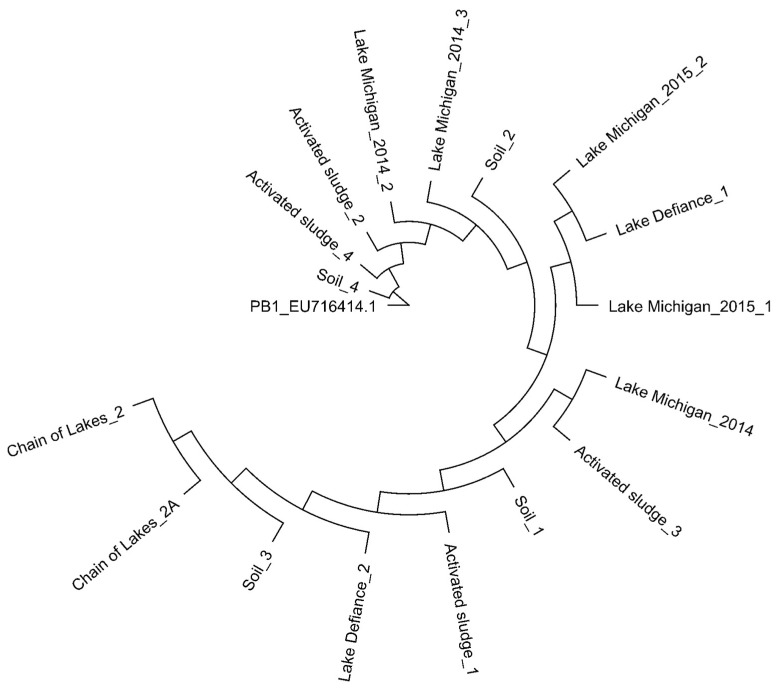

In our previous work, we evaluated the coding sequences of PB1 and Pbunaviruses to identify genes (called “informative genes”) that can be used as signatures of PB1 strains as well as other Pbunaviruses [66]. We designed primer pairs targeting five genomic regions (see Methods; Table 1). These genomic regions target genes encoding hypothetical proteins as well as the annotated helicase (primer pair 3 in Table 1). Primer sequences as well as expected amplicon sequences (using the PB1 genome, GenBank: NC_011810) were queried using BLASTn; resulting hits were only to Pbunavirus species. Replicate samples of soil, activated sludge, and freshwater were collected from locations throughout northern Illinois (see Methods). Samples were filtered and concentrated, and the community DNA extracted and amplified with each of the primer sets (see Methods). DNA isolated from three Lake Michigan collections, made the year prior (2014) and within our existing collection, were amplified as well. Sanger sequencing of the resulting amplicons confirmed specific amplification of genes belonging to the Pbunaviruses; sequences were found to have a coverage >99% and sequence identity >99% to a Pbunavirus sequence in GenBank. Sequenced amplicons produced by primer pair 5 (amplifying genes encoding hypothetical proteins PB1_gp84, 85, 86) were using to construct a neighbor joining phylogenetic tree (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic comparison of PCR amplicons of the genes encoding hypothetical proteins PB1_gp84, 85, 86 generated from environmental DNA. Neighbor-joining tree was generated based on the Jukes-Cantor distance method.

3.2. Searching for PB1 in Soil, Freshwater, and Activated Sludge Viral Metagenomes

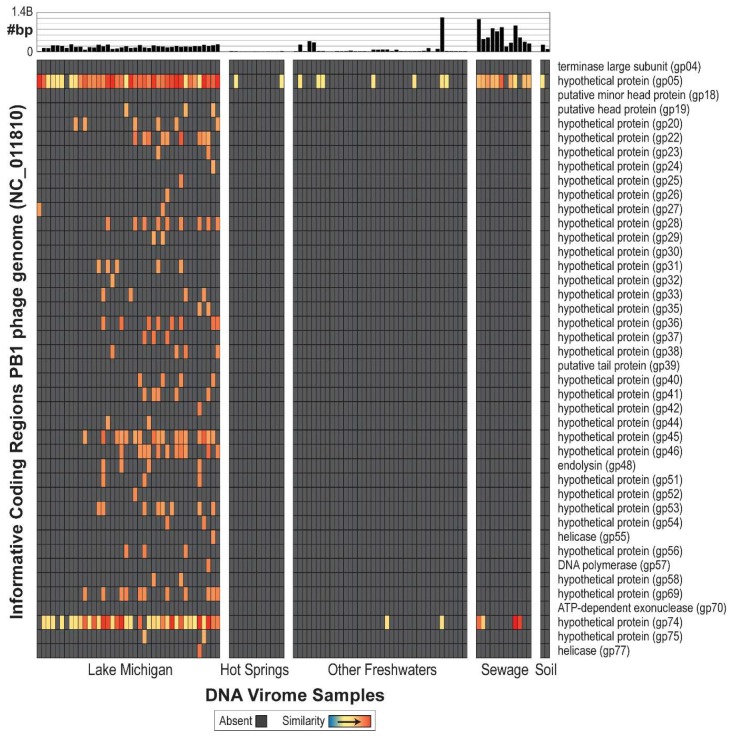

In total, 104 DNA viral metagenomes (from various environments) were inspected for the presence of PB1-like phages, including 40 from Lake Michigan nearshore waters (nine from collections made in 2013 [71] and 31 from 2014 [67]), 12 from hot springs, 38 from other freshwater sources, 12 from sewage, and two from soil (Table S1). Raw data was gathered for all data samples and assembled individually (see Methods). First, a purely BLAST-based approach was evaluated; all 104 viral metagenome samples produced high-quality hits to currently annotated PB1 genes (Figure S2). The 104 metagenomes were next re-evaluated considering only ORFs informative of PB1 genes listed in Figure 2. These genes are present within PB1 strains and do not exhibit sequence similarity to gene sequences within non-Pbunaviruses. As can be seen in Figure 2, many of metagenomes do not produce a signal (shown in gray) signifying that the viral metagenome did not include a sequence similar to the annotated gene sequences of PB1-like phages. Nevertheless, informative genes are detected within two hot spring samples, 47 freshwater samples, 11 sewage samples, and one soil sample. With the exception of the Lake Michigan samples, many of the samples identified only one informative gene. It is worth noting that comparable analyses were conducted for viral metagenome sets from marine environments, although no signal of the presence of PB1 was detected. To date, no Pseudomonas-infecting Pbunaviruses have been collected from marine/oceanic samples.

Figure 2.

PB1 genome atlas, demonstrating quality hits to the PB1 genome across environmental viral metagenomes. Genes for which no hit was detected are indicated by grey. The bar graph at the top of the figure represents amount of data collected for that sample.

3.3. Unique PB1-Like Phage Genomes Can Be Assembled and Closed from Viral Metagenome Data Generated from Lake Michigan

Given the abundance of informative genes within the 31 Lake Michigan datasets collected during 2014 (Figure 2), each was analyzed to determine the presence of complete or near-complete PB1-like phage genomes. De novo assemblies were performed for these 31 paired-end sequence datasets [67], exploring numerous different assemblers and parameters (see Methods). High-quality contigs were then queried via BLAST for the presence of PB1 genes. Hits were identified within contigs for 14 of these data sets. Further examination revealed that nine contained single contigs representative of complete, high coverage (15 to 220×) genomes of PB1-like phages. The five other datasets were excluded because of low coverage. The nine genomes ranged in size from 65,762 to 66,283 bp in length, each comprising 85–89 annotated genes (Table 2). Overall, the nine genomes had high nucleotide sequence identity to each other—greater than 99% (Table S2). In addition, each genome was assembled from a different water sample, either collected on different dates, at different locations or found within a different biological replicate (Table 2). Assembly did not require a subsequent laboratory-based effort to extend or close the genomes; rather each genome was fully assembled based on metagenomic data alone.

Table 2.

Descriptive information for the nine uncultivated PB1-like genomes from Lake Michigan samples.

| Phage | Isolation (Beach/Date) | Coverage (Average) | Length (bp) | # Annotated Genes | Accession Number | SRA Accession (Raw Reads) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallinipper | 95th Street/10 June 2014 | 30 | 65,917 | 89 | KT372690 | SRX956318 |

| Jollyroger | 57th Street/8 July 2014 | 200 | 65,795 | 90 | KT372691 | SRX995828 |

| Kraken | 95th Street/5 August 2014 (Biological Replicate 1) |

15 | 65,762 | 88 | KT372692 | SRX995836 |

| Kula | 95th Street/5 August 2014 (Biological Replicate 2) |

20 | 65,762 | 89 | KT372693 | SRX995836 |

| Nemo | 95th Street/5 August 2014 (Biological Replicate 3) |

20 | 66,283 | 88 | KT372694 | SRX995836 |

| Nessie | Wilmette/13 May 2014 | 220 | 65,762 | 89 | KT372695 | SRX995816 |

| Poseidon | Wilmette/5 August 2014 | 130 | 65,762 | 88 | KT372696 | SRX995833 |

| Smee | Montrose/8 July 2014 | 115 | 66,278 | 89 | KT372697 | SRX995827 |

| Triton | 57th/5 August 2014 | 125 | 65,762 | 85 | KT372698 | SRX995835 |

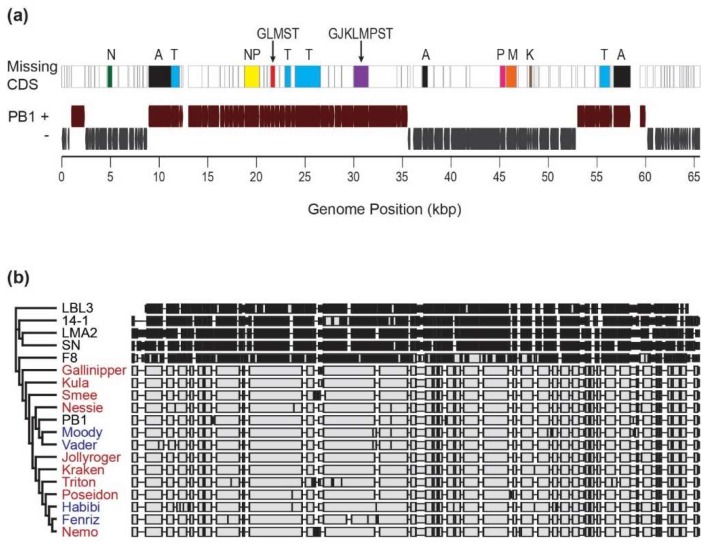

Comparing the uncultured PB1-like genomes to the PB1 RefSeq genome record revealed collinear blocks common to all, as well as open reading frames (ORFs) (all homologous to annotated hypothetical proteins) which were absent throughout the entire cohort (Figure 3a). The ORFs absent from or disturbed (often by a frameshift mutation or large indel) from one or more of the uncultivated Lake Michigan PB1-like viruses can be found in Table S3. A phylogenetic comparison of the candidate phages against other Pseudomonas-infecting members of the Pbunaviruses and the genomes of four PB1-like phages previously isolated from Lake Michigan [50] was performed (Figure 3b). The nine uncultivated Lake Michigan PB1-like viral genomes demonstrated closest similarities to PB1 and the previously isolated Lake Michigan phages and exhibited marked differences from the genomes of the other Pbunaviruses.

Figure 3.

(a) Genome map of PB1-like genomes. CDS regions which are missing/disrupted in the new uncultivated viral genomes are indicated (A = All 9 genomes; G = Gallinipper; J = Jollyroger; K = Kraken; L = Kula; M = Nemo; N = Nessie; P = Poseidon; S = Smee; T = Triton). (b) Phylogenetic comparison of uncultivated Lake Michigan PB1-like viruses (red) to Pseudomonas-infecting Pbunaviruses. PB1 strains indicated in blue font are phages previously cultured and isolated from Lake Michigan [50].

4. Discussion

Given the ubiquity of Pseudomonas, it is not surprising that Pbunaviruses have been previously isolated from a vast array of environments [50,51,54,55,56,57,58]. By targeting a collection of species and genus specific genes, Pbunaviruses were detected within soil, freshwater, and activated sludge samples collected here. Comparison of these amplicon sequences revealed sequence diversity; contrary to our initial expectations, samples collected from the same geographical location or source (soil, freshwater, activated sludge) did not clade together. While the amplicon sequences indicate that Pbunaviruses (or very close relatives) are present in northern Illinois, the phylogenetic tree suggests genetic variation amongst the samples that is not dictated by the type of environment sampled. Comprehensive analysis determined that the PB1-like phages, are, in fact, very well represented throughout datasets collected from Lake Michigan (Figure 2). The samples sequenced from collections made in the summer of 2014 [67] included more “informative genes” than the sequences from the samples collected in the summer of 2013. Nevertheless, these are the same sites from which the PB1-like phages φVader, φMoody, φHabibi, and φFenriz were isolated during the summer of 2013 [50].

The evidence for the presence of Pbunaviruses in other freshwaters, soils, wastewater, and hot springs metagenomes, is however, tenuous (Figure 2). This may be a result of differences in the sample sites themselves (e.g., oligotrophy, season, depth, etc.), sample preparation, sequencing depth and/or technology, or PB1 abundance within the particular sample. Interestingly, PB1 gp05 (128 amino acids in length) and gp74 (150 amino acids in length), both annotated as hypothetical proteins, are detected—often at very high levels—within these samples. Both of these genes were found to be Pbunavirus-specific, not present in any other sequenced phage genome. Furthermore, each was queried (tBLASTn) against the complete nr/nt database; all hits returned were to Pbunaviruses. BLASTp analysis confirmed that gp05 is exclusively found with Pbunavirus sequences and PB1′s gp74 amino acid sequence exhibited only modest sequence homology (57% query coverage and 42% sequence identity) to a hypothetical protein within the T4-like Pseudomonas putida-infecting phage pf16 [72]. These proteins are of particular interest with regards to characterizing their function. The detection of these two hypothetical proteins in other viral metagenomic samples can be the result of: (1) the presence of distant Pbunavirus relatives; (2) evidence of prior gene sharing between Pbunaviruses and other viral species; or (3) these similar sequences originating independently.

During examination of a viral metagenomic survey of Lake Michigan, we were able to assemble nine separate PB1-like genomes, de novo from the data generated. Variation was observed between the uncultivated assembled viruses including size. Three of the genomes, Kraken, Kula and Nemo, came from biological replicates collected from the same site (Calumet Beach) on 5 August 2014. From the pairwise assembly of the genomes of Kula and Nemo, 529 nucleotide differences were observed (Table S2). This suggests that even within a niche (as replicates were collected within a 5 m area [67]), significant viral microdiversity exists. Interestingly, a complete PB1-like genome was unable to be assembled from the fourth biological replicate collected. Variation was also observed among the nine genomes with respect to the number of ORFs identified. It is important to note that reading frames and predicted functions were determined based upon the PB1 genome annotation. Regions which are missing/disrupted in the new uncultivated viral genomes were predominantly PB1 annotated hypothetical proteins (Figure 3A; Table S3). Nevertheless, disruptions were observed in all 9 genomes for the minor head protein (PB1 gp18) and helicase (PB1 gp77). Nevertheless, the genomes of all nine uncultivated viruses were more similar to PB1-like viruses than other members of the genus.

Significant sequence coverage suggests that these phages were present in the Lake Michigan samples in high abundance. The nine genomes essentially fell out of the data, providing a more genuine representation of viral abundance than the number of hits alone. Luo et al. [73] estimated genomes may be assembled most accurately from metagenomes with a coverage of 20×—the coverage of many of the genomes examined in this study far exceeded this measure (Table 2). As with the discovery of crAssphage, ubiquitous in human fecal metagenomes [39], ultimately the efficacy of assembling entire genomes from complex environmental datasets is reliant on the initial high abundance of the organism, or an alternative factor which effectively places it as the low hanging fruit in that data. However, as generating complete genomes of other characterized phage genomes from our data was not possible, the former is likely the case here.

We were unable to produce a complete genome assembly of a PB1-like virus from the nine viral metagenomic dataset from Lake Michigan collected the year before and hits to informative genes in the PB1 genome were low throughout (Figure 2). This suggests that the incidence of PB1-like viruses was considerably higher, for whatever reason, during the 2014 sampling effort, and that the presence of this group of viruses is likely to be, unsurprisingly, dynamic. Nevertheless, we are confident that PB1 viruses were present during 2013 as four were isolated and characterized from these very same samples [50]. The results of culture-independent and culture-dependent methods further supports the presence of a dynamic community.

Although culture-based studies of phages can provide multiple key aspects of a phage’s ecology, the many challenges with working with phages in the laboratory [6] limit our understanding of their genetic diversity. Viral metagenomic studies, however, have the potential to uncover far more than just a phage’s genome [21]. Through comparative viral metagenomics we were able to identify samples for which PB1-like viruses were present as well as abundant, thereby providing insight into the phage’s ecology. Hypothesis-driven data mining coupled with experimental work, such as the approach presented here for the investigation of PB1-like viruses, has significant potential to greatly expand our understanding of phage ecology.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joy Watts for her comments on an early version of the manuscript. This work was funded by the NSF (1149387) (C.P.). E.S. was supported by a Mulcahy Research Fellowship from Loyola University Chicago.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/10/6/331/s1, Figure S1: Map of collection sites for this study. Figure S2: PB1 BLAST genome atlas. Bitscore values of BLAST queries for each PB1 gene in each metagenome is indicated. Table S1: Information about the viral metagenomic data sets evaluated for the presence of Pseudomonas phage PB1. Table S2: Sequence similarity between the nine uncultivated genomes assembled in this study. Table S3: List of coding sequences missing or disrupted genes in the nine uncultivated genomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C.W. and C.P.; Formal Analysis, S.C.W., E.S. and C.P., Data Curation, E.S. and C.P.; Writing, S.C.W. and C.P.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Salmond G.P.C., Fineran P.C. A century of the phage: Past, present and future. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015;13:777–786. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suttle C.A. Viruses in the sea. Nature. 2005;437:356–361. doi: 10.1038/nature04160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohwer F., Thurber R.V. Viruses manipulate the marine environment. Nature. 2009;459:207–212. doi: 10.1038/nature08060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balcazar J.L. Bacteriophages as vehicles for antibiotic resistance genes in the environment. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004219. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hargreaves K.R., Kropinski A.M., Clokie M.R. Bacteriophage behavioral ecology: How phages alter their bacterial host’s habits. Bacteriophage. 2014;4:e29866. doi: 10.4161/bact.29866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breitbart M. Marine viruses: Truth or dare. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2012;4:425–448. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hug L.A., Baker B.J., Anantharaman K., Brown C.T., Probst A.J., Castelle C.J., Butterfield C.N., Hernsdorf A.W., Amano Y., Ise K., et al. A new view of the tree of life. Nat. Microbiol. 2016;1:16048. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruder K., Malki K., Cooper A., Sible E., Shapiro J.W., Watkins S.C., Putonti C. Freshwater Metaviromics and Bacteriophages: A Current Assessment of the State of the Art in Relation to Bioinformatic Challenges. Evol. Bioinform. 2016;12:25–33. doi: 10.4137/EBO.S38549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perez Sepulveda B., Redgwell T., Rihtman B., Pitt F., Scanlan D.J., Millard A. Marine phage genomics: The tip of the iceberg. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2016;363:fnw158. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnw158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pratama A.A., van Elsas J.D. The “Neglected” Soil Virome–Potential Role and Impact. Trends Microbiol. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paez-Espino D., Eloe-Fadrosh E.A., Pavlopoulos G.A., Thomas A.D., Huntemann M., Mikhailova N., Rubin E., Ivanova N.N., Kyrpides N.C. Uncovering Earth’s virome. Nature. 2016;536:425–430. doi: 10.1038/nature19094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roux S., Hallam S.J., Woyke T., Sullivan M.B. Viral dark matter and virus–host interactions resolved from publicly available microbial genomes. eLife. 2015;4:e08490. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coutinho F.H., Silveira C.B., Gregoracci G.B., Thompson C.C., Edwards R.A., Brussaard C.P.D., Dutilh B.E., Thompson F.L. Marine viruses discovered via metagenomics shed light on viral strategies throughout the oceans. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15955. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clokie M.R., Millard A.D., Letarov A.V., Heaphy S. Phages in nature. Bacteriophage. 2011;1:31–45. doi: 10.4161/bact.1.1.14942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Labonté J.M., Suttle C.A. Metagenomic and whole-genome analysis reveals new lineages of gokushoviruses and biogeographic separation in the sea. Front. Microbiol. 2013;4:404. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson C.A., Marston M.F., Martiny J.B.H. Biogeographic Variation in Host Range Phenotypes and Taxonomic Composition of Marine Cyanophage Isolates. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:983. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chow C.-E.T., Suttle C.A. Biogeography of Viruses in the Sea. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2015;2:41–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-031413-085540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chow C.-E.T., Winget D.M., White R.A., Hallam S.J., Suttle C.A. Combining genomic sequencing methods to explore viral diversity and reveal potential virus-host interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:265. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez-Hernandez F., Fornas O., Gomez M.L., Bolduc B., de La Cruz Peña M.J., Martínez J.M., Anton J., Gasol J.M., Rosselli R., Rodriguez-Valera F., et al. Single-virus genomics reveals hidden cosmopolitan and abundant viruses. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15892. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De La Cruz Peña M.J., Martinez-Hernandez F., Garcia-Heredia I., Lluesma Gomez M., Fornas Ò., Martinez-Garcia M. Deciphering the human virome with single-virus genomics and metagenomics. Viruses. 2018;10:113. doi: 10.3390/v10030113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurwitz B.L., Westveld A.H., Brum J.R., Sullivan M.B. Modeling ecological drivers in marine viral communities using comparative metagenomics and network analyses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:10714–10719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319778111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roux S., Enault F., Hurwitz B.L., Sullivan M.B. VirSorter: Mining viral signal from microbial genomic data. PeerJ. 2015;3:e985. doi: 10.7717/peerj.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ren J., Ahlgren N.A., Lu Y.Y., Fuhrman J.A., Sun F. VirFinder: A novel K-MER based tool for identifying viral sequences from assembled metagenomic data. Microbiome. 2017;5:69. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0283-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garza D.R., Dutilh B.E. From cultured to uncultured genome sequences: Metagenomics and modeling microbial ecosystems. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2015;72:4287–4308. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2004-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iverson V., Morris R.M., Frazar C.D., Berthiaume C.T., Morales R.L., Armbrust E.V. Untangling genomes from metagenomes: Revealing an uncultured class of marine Euryarchaeota. Science. 2012;335:587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1212665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wrighton K.C., Thomas B.C., Sharon I., Miller C.S., Castelle C.J., VerBerkmoes N.C., Wilkins M.J., Hettich R.L., Lipton M.S., Williams K.H., et al. Fermentation, Hydrogen, and Sulfur Metabolism in Multiple Uncultivated Bacterial Phyla. Science. 2012;337:1661–1665. doi: 10.1126/science.1224041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inskeep W.P., Jay Z.J., Herrgard M.J., Kozubal M.A., Rusch D.B., Tringe S.G., Macur R.E., Boyd E.S., Spear J.R., Roberto F.F. Phylogenetic and Functional Analysis of Metagenome Sequence from High-Temperature Archaeal Habitats Demonstrate Linkages between Metabolic Potential and Geochemistry. Front. Microbiol. 2013;4:95. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharon I., Banfield J.F. Genomes from Metagenomics. Science. 2013;342:1057–1058. doi: 10.1126/science.1247023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Handley K.M., Bartels D., O’Loughlin E.J., Williams K.H., Trimble W.L., Skinner K., Gilbert J.A., Desai N., Glass E.M., Paczian T., et al. The complete genome sequence for putative H2- and S-oxidizer Candidatus Sulfuricurvum sp., assembled de novo from an aquifer-derived metagenome. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;16:3443–3462. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nielsen H.B., Almeida M., Juncker A.S., Rasmussen S., Li J., Sunagawa S., Plichta D.R., Gautier L., Pedersen A.G., Le Chatelier E., et al. Identification and assembly of genomes and genetic elements in complex metagenomic samples without using reference genomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:822–828. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown C.T. Strain recovery from metagenomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:1041–1043. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spang A., Saw J.H., Jørgensen S.L., Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka K., Martijn J., Lind A.E., van Eijk R., Schleper C., Guy L., Ettema T.J.G. Complex archaea that bridge the gap between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Nature. 2015;521:173–179. doi: 10.1038/nature14447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anantharaman K., Breier J.A., Dick G.J. Metagenomic resolution of microbial functions in deep-sea hydrothermal plumes across the Eastern Lau Spreading Center. ISME J. 2016;10:225–239. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta A., Kumar S., Prasoodanan V.P.K., Harish K., Sharma A.K., Sharma V.K. Reconstruction of Bacterial and Viral Genomes from Multiple Metagenomes. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:469. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haroon M.F., Thompson L.R., Parks D.H., Hugenholtz P., Stingl U. A catalogue of 136 microbial draft genomes from Red Sea metagenomes. Sci. Data. 2016;3:160050. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laczny C.C., Muller E.E.L., Heintz-Buschart A., Herold M., Lebrun L.A., Hogan A., May P., de Beaufort C., Wilmes P. Identification, Recovery, and Refinement of Hitherto Undescribed Population-Level Genomes from the Human Gastrointestinal Tract. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:884. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Svartström O., Alneberg J., Terrapon N., Lombard V., de Bruijn I., Malmsten J., Dalin A.-M., EL Muller E., Shah P., Wilmes P., et al. Ninety-nine de novo assembled genomes from the moose (Alces alces) rumen microbiome provide new insights into microbial plant biomass degradation. ISME J. 2017;11:2538–2551. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roux S., Krupovic M., Poulet A., Debroas D., Enault F. Evolution and Diversity of the Microviridae Viral Family through a Collection of 81 New Complete Genomes Assembled from virome reads. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e40418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dutilh B.E., Cassman N., McNair K., Sanchez S.E., Silva G.G.Z., Boling L., Barr J.J., Speth D.R., Seguritan V., Aziz R.K., et al. A highly abundant bacteriophage discovered in the unknown sequences of human faecal metagenomes. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4498. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smits S.L., Bodewes R., Ruiz-González A., Baumgärtner W., Koopmans M.P., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Schürch A.C. Recovering full-length viral genomes from metagenomes. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:1069. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andersson A.F., Banfield J.F. Virus population dynamics and acquired virus resistance in natural microbial communities. Science. 2008;320:1047–1050. doi: 10.1126/science.1157358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Labonté J.M., Suttle C.A. Previously unknown and highly divergent ssDNA viruses populate the oceans. ISME J. 2013;7:2169–2177. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mizuno C.M., Rodriguez-Valera F., Garcia-Heredia I., Martin-Cuadrado A.-B., Ghai R. Reconstruction of novel cyanobacterial siphovirus genomes from Mediterranean metagenomic fosmids. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79:688–695. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02742-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mizuno C.M., Rodriguez-Valera F., Kimes N.E., Ghai R. Expanding the marine virosphere using metagenomics. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bellas C.M., Anesio A.M., Barker G. Analysis of virus genomes from glacial environments reveals novel virus groups with unusual host interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:656. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Skvortsov T., de Leeuwe C., Quinn J.P., McGrath J.W., Allen C.C.R., McElarney Y., Watson C., Arkhipova K., Lavigne R., Kulakov L.A. Metagenomic characterisation of the viral community of Lough Neagh, the largest freshwater lake in Ireland. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0150361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Voorhies A.A., Eisenlord S.D., Marcus D.N., Duhaime M.B., Biddanda B.A., Cavalcoli J.D., Dick G.J. Ecological and genetic interactions between cyanobacteria and viruses in a low-oxygen mat community inferred through metagenomics and metatranscriptomics: Cyanobacteria-virus interactions in a low-O2 mat community. Environ. Microbiol. 2016;18:358–371. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghai R., Mehrshad M., Mizuno C.M., Rodriguez-Valera F. Metagenomic recovery of phage genomes of uncultured freshwater actinobacteria. ISME J. 2017;11:304–308. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simmonds P., Adams M.J., Benkő M., Breitbart M., Brister J.R., Carstens E.B., Davison A.J., Delwart E., Gorbalenya A.E., Harrach B., et al. Virus taxonomy in the age of metagenomics: Consensus statement. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017;15:161–168. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malki K., Kula A., Bruder K., Sible E., Hatzopoulos T., Steidel S., Watkins S.C., Putonti C. Bacteriophages isolated from Lake Michigan demonstrate broad host-range across several bacterial phyla. Virol. J. 2015;12:164. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0395-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ceyssens P.-J., Miroshnikov K., Mattheus W., Krylov V., Robben J., Noben J.-P., Vanderschraeghe S., Sykilinda N., Kropinski A.M., Volckaert G., et al. Comparative analysis of the widespread and conserved PB1-like viruses infecting Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;11:2874–2883. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krylov V.N., Tolmachova T.O., Akhverdian V.Z. DNA homology in species of bacteriophages active on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Arch. Virol. 1993;131:141–151. doi: 10.1007/BF01379086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lavigne R., Darius P., Summer E.J., Seto D., Mahadevan P., Nilsson A.S., Ackermann H.W., Kropinski A.M. Classification of Myoviridae bacteriophages using protein sequence similarity. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:224. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garbe J., Wesche A., Bunk B., Kazmierczak M., Selezska K., Rohde C., Sikorski J., Rohde M., Jahn D., Schobert M. Characterization of JG024, a pseudomonas aeruginosa PB1-like broad host range phage under simulated infection conditions. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:301. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Danis-Wlodarczyk K., Olszak T., Arabski M., Wasik S., Majkowska-Skrobek G., Augustyniak D., Gula G., Briers Y., Jang H.B., Vandenheuvel D., et al. Characterization of the Newly Isolated Lytic Bacteriophages KTN6 and KT28 and Their Efficacy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilm. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0127603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pires D.P., Sillankorva S., Kropinski A.M., Lu T.K., Azeredo J. Complete Genome Sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Phage vB_PaeM_CEB_DP1. Genome Announc. 2015;3:e00918-15. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00918-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pourcel C., Midoux C., Latino L., Petit M.-A., Vergnaud G. Complete Genome Sequences of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Phages vB_PaeP_PcyII-10_P3P1 and vB_PaeM_PcyII-10_PII10A. Genome Announc. 2016;4:e00916-16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00916-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Neves P.R., Cerdeira L.T., Mitne-Neto M., Oliveira T.G.M., McCulloch J.A., Sampaio J.L.M., Mamizuka E.M., Levy C.E., Sato M.I.Z., Lincopan N. Complete Genome Sequence of an F8-Like Lytic Myovirus (SPM-1) That Infects Metallo-Lactamase-Producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Genome Announc. 2014;2:e00061-14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00061-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zwart G., Crump B., Kamst-van Agterveld M., Hagen F., Han S. Typical freshwater bacteria: An analysis of available 16S rRNA gene sequences from plankton of lakes and rivers. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 2002;28:141–155. doi: 10.3354/ame028141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Newton R.J., Jones S.E., Eiler A., McMahon K.D., Bertilsson S. A Guide to the natural history of freshwater lake bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011;75:14–49. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00028-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brum J.R., Ignacio-Espinoza J.C., Roux S., Doulcier G., Acinas S.G., Alberti A., Chaffron S., Cruaud C., de Vargas C., Gasol J.M., et al. Ocean plankton. Patterns and ecological drivers of ocean viral communities. Science. 2015;348:1261498. doi: 10.1126/science.1261498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hurwitz B.L., Sullivan M.B. The Pacific Ocean Virome (POV): A Marine Viral Metagenomic Dataset and Associated Protein Clusters for Quantitative Viral Ecology. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e57355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yutin N., Suzuki M.T., Teeling H., Weber M., Venter J.C., Rusch D.B., Béjà O. Assessing diversity and biogeography of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in surface waters of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans using the Global Ocean Sampling expedition metagenomes. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;9:1464–1475. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Angly F., Rodriguez-Brito B., Bangor D., McNairnie P., Breitbart M., Salamon P., Felts B., Nulton J., Mahaffy J., Rohwer F. PHACCS, an online tool for estimating the structure and diversity of uncultured viral communities using metagenomic information. BMC Bioinform. 2005;6:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zerbino D.R., Birney E. Velvet: Algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 2008;18:821–829. doi: 10.1101/gr.074492.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Watkins S.C., Putonti C. The use of informativity in the development of robust viromics-based examinations. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3281. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sible E., Cooper A., Malki K., Bruder K., Watkins S.C., Fofanov Y., Putonti C. Survey of viral populations within Lake Michigan nearshore waters at four Chicago area beaches. Data Brief. 2015;5:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A.A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A.S., Lesin V.M., Nikolenko S.I., Pham S., Prjibelski A.D., et al. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Langmead B., Salzberg S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Darling A.C.E., Mau B., Blattner F.R., Perna N.T. Mauve: Multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Watkins S.C., Kuehnle N., Ruggeri C.A., Malki K., Bruder K., Elayyan J., Damisch K., Vahora N., O’Malley P., Ruggles-Sage B., et al. Assessment of a metaviromic dataset generated from nearshore Lake Michigan. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2016;67:1700–1708. doi: 10.1071/MF15172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Magill D.J., Krylov V.N., Shaburova O.V., McGrath J.W., Allen C.C.R., Quinn J.P., Kulakov L.A. Pf16 and phiPMW: Expanding the realm of Pseudomonas putida bacteriophages. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0184307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Luo C., Tsementzi D., Kyrpides N.C., Konstantinidis K.T. Individual genome assembly from complex community short-read metagenomic datasets. ISME J. 2012;6:898–901. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.