Abstract

Applications for bacteriophages as antimicrobial agents are increasing. The industrial use of these bacterial viruses requires the production of large amounts of suitable strictly lytic phages, particularly for food and agricultural applications. This work describes a new approach for phage production. Phages H387 (Siphoviridae) and A511 (Myoviridae) were propagated separately using Listeria ivanovii host cells immobilised in alginate beads. The same batch of alginate beads could be used for four successive and efficient phage productions. This technique enables the production of large volumes of high-titer phage lysates in continuous or semi-continuous (fed-batch) cultures.

Keywords: Listeria ivanovii, bacteriophages, alginate, production, disinfection, phagodisinfection

1. Introduction

Listeria monocytogenes is responsible for fatal cases of listeriosis in humans via contaminated food products [1]. This bacterial species is ubiquitous in nature and can contaminate the food processing line at any critical point. The increasing resistance of these pathogens to disinfectants under certain conditions requires the use of higher concentrations of chemical products [2]. Furthermore, bacteria exposed to disinfectants may be more likely to develop antibiotic resistance [3,4]. Despite strict regulatory policies, the occurrence of L. monocytogenes still has detrimental consequences for the food industry.

The search for alternatives to overcome these challenges has rekindled interest for bacterial viruses (bacteriophages) in agriculture [5], aquaculture [6], food safety [7], and even in infectious diseases [8,9]. The use of strictly lytic (i.e., virulent) phages infecting Listeria as biosanitisers represents an ecological alternative that could reduce the use of chemical compounds and lower the concentrations of toxic residues in the environment [10]. Specific biodisinfectants consisting of suspensions of phages can provide a natural means to control pathogens in processed foods and on contact surfaces. For example, the virulent phage A511 has a very broad host range against several strains of Listeria spp. [11,12,13] and could be included in the formulation of this type of biodisinfectants.

Phage biocontrol of L. monocytogenes strains was first introduced in 2006 with the commercial product ListShield, which contained a cocktail of phages applicable to various foods. Another product is Phageguard Listex P100, which also aimed to reduce L. monocytogenes in a range of food products [14,15,16,17,18]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that different virulent phages can reduce the L. monocytogenes population after adhesion to stainless steel or polypropylene surfaces, and a synergistic effect has been observed by combining phages with quaternary ammonium [19,20,21].

However, even if virulent phages have shown great potential for killing pathogenic or opportunistic food-borne bacteria [22], their production on a large scale often remains challenging. Phage production still involves traditional methods using tubes or Erlenmeyer flasks, or it is done in bioreactors as a batch process [23]. High phage titers can be obtained [24,25], but batch processes require significant manpower and non-operational periods of time that may be limiting [26].

Attempts have been made to overcome the disadvantages of the batch process with continuous phage production. Studies involving chemostats [25,27] have been conducted, as well as two-stage continuous processes or cellstat [25,28,29,30], which consists of culturing bacteria, separately, in the first stage to feed to a second stage when phages are produced. Although chemostat allows the cultivation of microorganisms at a physiological steady state [31], the bacterial culture may be less genetically stable, as mutations can occur [32]. Cellstat is recognised as a phage production system for strictly lytic phages [33] that avoids direct phage exposure and pressure but requires the use of two different bioreactors [34].

With the aim of reducing production time and costs, we investigated here a different phage production procedure that employs host bacteria entrapped in a porous gel matrix. Alginate gel was selected for the matrix because of its low cost and widespread use in a range of applications in medicine, pharmacy, biotechnology, and the food industry [35,36]. An alginate matrix with entrapped bacterial cells can be produced in a single-step process and has virtually no impact on the viability of the cells. Alginate can also form a gel in the presence of divalent cations, such as calcium, which are also often necessary as co-factors for phage multiplication [37,38].

Entrapped cells will still grow because nutrients diffuse through the gel matrix [39], and while microcolonies spread deeper in the beads, the bacterial density has been shown to be higher near to or at the surface of the beads [40,41,42]. Such a growth pattern leads to bacterial cell release in the medium by micro-fracture events in the matrix. Only bacterial cells released from the gel become infected and contribute to the propagation of virulent phages. Those cells remaining in the gel have been shown to be protected from the phages, as the bacterial viruses do not migrate into the beads because of their size [43,44,45]. Protein diffusion through the matrix is highly reduced when molecular weight is above 150 kDa [46].

Relevant advantages of using entrapped cells to produce strictly lytic phages are that the phage lysate can be easily recovered and the alginate beads can be reused for successive phage propagations. Multiple phage lytic cycles can also be favoured, because this protective system prevents the rapid decline of the phage-sensitive host population. This process also provides an opportunity to produce phages in continuous or semi-continuous (fed-batch) cultures. Taken together, the use of calcium alginate immobilised cells (in spheres or fibers) to produce phages is a bi-phasic technique that controls the bacterial population and preserves the integrity of the cells, as long as they remain entrapped in the matrix.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacteria, Phages, and Media

Listeria ivanovii WSLC 3009 and the broad-host-range virulent myovirus A511 [47] were obtained from the Institut für Mikrobiologie, ZIEL Institute for Food and Health, Technische Universität München (Germany). The siphovirus H387 [48,49] was obtained from the Félix d’Hérelle Reference Center for Bacterial Viruses (www.phage.ulaval.ca) of the Université Laval (Québec, Canada). Bacterial strains were grown in Trypticase soy broth (TSB) or plated on Trypticase soy agar (TSA) at 30 °C. Phage titration was done using the double-layer plating technique [50] on TSA. Phage stocks (>1 × 108 Plaque Forming Unit (PFU) mL−1) were stored at 4 °C prior to use.

2.2. Alginate Gels and Cell Immobilisation by Entrapment

A 2–4% (w/v) aqueous solution of sodium alginate was prepared by suspending the polymer in distilled water. Solutions were sterilised by autoclaving (121 °C, 15 min). L. ivanovii cells were harvested by centrifugation (8000 rpm, 10 min) and resuspended in sterile TSB (3 mL). The cell suspensions were then mixed with sterile alginate [51]. Beads were formed by the dropwise addition of the alginate-cell mixtures into sterile CaCl2 (200 mM) using a syringe and a 20 Gauge (G) needle. The cell-containing beads, 2 to 3 mm in diameter, were allowed to solidify for 1 to 2 h before CaCl2 was replaced by fresh TSB containing 0.5 mM CaCl2 to maintain the integrity of the alginate beads.

2.3. Morphology of Cells Immobilised in Beads

Alginate beads were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to visualise entrapped Listeria cells. The alginate beads were cut in half, and the specimens were fixed by immersion in glutaraldehyde (2.5% v/v) in 0.1 M sterile cacodylate buffer (pH 7.0) for 4 h. The samples were washed twice in 0.1 M sterile cacodylate for 20 min. Post-fixation was done in osmium tetroxide (2% v/v) in sterile cacodylate buffer for 30 min at 30 °C, and dehydration was completed using CO2 in a critical point dryer (Model 3000 CPD, Bio-Rad, Mississauga, ON, Canada). The samples were mounted on stubs and covered with 15 nm of gold using a sputter coater (Emscope, Bio-Rad). A Nanolab LE 2100 (Vickers Instruments, Bausch and Lomb, Nepean, ON, Canada) scanning electron microscope operating at 15 hV was used to examine the bead surfaces.

2.4. Phage Adsorption

A set of alginate beads was made as described above but omitting the bacterial cells. Ten grams of pure alginate beads was transferred into TSB. Aliquots of phage suspensions (0.1 and 1 mL) were added and incubated at 30 °C for 12 h. The adsorption of phages on alginate beads was monitored by determining phage titers every 4 h. Two independent experiments were performed.

2.5. Biomass Concentration

To estimate the population of immobilised bacteria, 1 mL of alginate beads was dissolved in 9.0 mL of Na+ citrate (50 mM), a sequestrant for Ca++. The number of viable cells in the dissolved alginate gel was determined by direct plating on TSA for two independent experiments.

2.6. Phage Production

2.6.1. Free Cells

TSB (100 mL) was inoculated (5%) with an overnight culture of L. ivanovii 3009 from the Weihenstephan Listeria collection (WSLC) and grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5–0.8. Phages were added at multiplicities of infection (MOIs) of 0.1 (1:10) and 1 (1:1), and the mixture was incubated for 16 h at 30 °C. Phage titers were measured every 4 h for two independent experiments.

2.6.2. Immobilised Cells Used for Single and Successive Phage Propagations

Beads containing entrapped microorganisms were transferred at least 2–4 times into prewarmed (30 °C) fresh TSB before phage production. Ten grams of beads containing L. ivanovii cells was added to 100 mL of TSB (OD600 of 0.5–0.8), and phage suspensions (at MOIs of 0.1 and 1) were added to the cultures. The flasks were incubated at 30 °C for 16 h, and phage titers were also determined as described above for two independent experiments. Between each successive production, the beads were stored overnight at 4 °C in sterile 2% (w/v) CaCl2. The beads were then washed twice with sterile 2% CaCl2 and reactivated as described above before each production.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Mean and standard deviation values were calculated using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphological Observations

For the efficient use of alginate microbeads, morphological characteristics such as size and shape are important [52]. The produced alginate beads had proper sphericality and were typically 2 to 3 mm in size (Figure 1). Scanning electron micrographs of entrapped Listeria revealed no major changes in cell morphology (Figure 1). The mechanical constraints of the polymer did not seem to interfere with cell growth.

Figure 1.

Observation of entrapped alginate bacteria. (Left) Visual appearance of alginate beads containing Listeria ivanovii WSLC 3009 (108 Colony Forming Unit (CFU) mL−1) in a Petri dish. (Right) Scanning electron micrograph of L. ivanovii WSLC 3009 immobilised in alginate beads (×10,000).

3.2. Phage Adsorption

Phage adsorption onto the gel matrix is a parameter that may impact the overall performance of the production system. The electrostatic adsorption of phages onto polymer beads could decrease the number and infectivity of phage particles in the medium. For this reason, the organic material selected for phage production should be tested for ionic attraction of viral particles. No decreases in the titers of phages A511 and H387 were observed in the medium after contact with the alginate beads. These results suggest that no major ionic interactions exist between the organic polymer and the phages.

3.3. Biomass Concentration

The concentration of entrapped cells in alginate beads has been studied for several types of bacteria [39,51,53,54]. Alginate is non-toxic to most living cells [55] and provides protection against external stresses such as temperature, pH, and toxic molecules. Figure 2 shows that three successive transfers (reactivations) of entrapped L. ivanovii cells in fresh TSB could raise the bacterial cell concentration inside the gel to almost 1 × 109 cells mL−1, while five transfers increased the bacterial counts to almost 1010 cells mL−1. Because the number of bacteria released into a medium is related to, among other parameters, the saturation level of the cells in the alginate structure, the yield of phage production will likely be influenced by the concentration of bacteria in the beads and at the bead surface.

Figure 2.

Transfers of Listeria ivanovii WSLC 3009 immobilised cells in fresh Trypticase soy broth (TSB) medium. Each reactivation was followed by an interval of 12 h. Bacterial concentrations were measured after 12 h of growth at 30 °C. Mean values were calculated from two independent experiments, and error bars correspond to standard deviations.

3.4. Phage Production

3.4.1. Free Cells

Phage productions in liquid medium were performed with both phages individually (Figure 3). All phage productions were characterized by a lag phase for the first 4 h, followed by a sharp increase in phage titers at 8 h. Maximal phage titers were close to 1010 PFU mL−1 of medium after 12 h. Very small variations in phage titers were observed at different MOIs. After 16 h, the titer of phage H387 decreased when using a 1:10 ratio. It is unclear at this time what caused this decrease in the phage titer, but it could have been due to phage adsorption to cell debris.

Figure 3.

Production of phages A511 and H387 on Listeria ivanovii WSLC 3009 in liquid medium, using multiplicities of infection (MOIs) of 1 and 0.1. Phage counts were measured every 4 h. Mean values were calculated from two independent experiments, and error bars correspond to standard deviations.

3.4.2. Immobilised Cells Used for Single and Successive Phage Propagations

Microorganisms immobilised in polymers produce concentrated host bacteria that can be more easily and rapidly manipulated than free cells. Phage production using gel-entrapped host cells was compared to that of free cells in the same culture medium and under the same growing conditions. The highest production of virulent Listeria phages A511 and H387 was obtained after 12 h using a MOI of 1 (Figure 4). The maximum phage titers achieved using entrapped cells were slightly lower than for free cells. Some phage productions reached their maximum titer after 8 h of incubation, which was faster than for the free cells.

Figure 4.

Production of phages A511 and H387 on Listeria ivanovii WSLC 3009 immobilised in alginate beads, using 1 and 0.1 multiplicities of infection (MOIs). Phage titers were measured every 4 h. Mean values were calculated from two independent experiments, and error bars correspond to standard deviations.

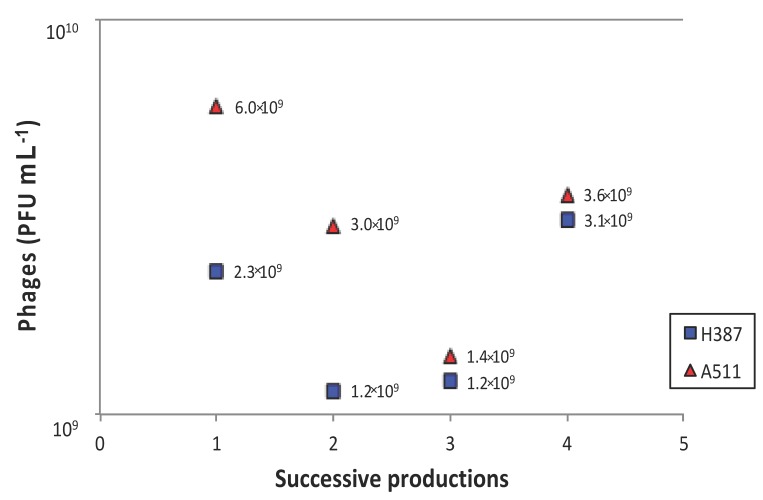

Two advantages of using gel-entrapped cells to produce virulent phages are that phage particles can be easily recovered by draining the culture medium (followed by centrifugation and filtration) and that phage propagation can be immediately resumed or pursued after a short or prolonged storage period. The same alginate beads with immobilised L. ivanovii cells were used for four successive phage productions. In all cases, phage titers were maintained at over 109 PFU mL−1 after the four productions (Figure 5). In general, the final phage titers of the virulent phage A511 were higher than for phage H387.

Figure 5.

Successive productions of the two phages, A511 and H387, on Listeria ivanovii WSLC 3009 using a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. Aliquots were withdrawn after 10 h of incubation. Mean values were calculated from two independent experiments.

It has been shown previously that phages infecting some lactic acid bacteria cannot penetrate calcium alginate gels [43,44]. Because Listeria phages are the same size as dairy phages and even larger in the case of A511 [56,57], bacterial cells are well protected from phage infection as long as they remain entrapped in the gel. It is likely that this physical constraint, protecting the integrity of the bacterial population, allows the gel beads to be reused for successive phage production in new media. This advantage cannot be provided by free-cell amplification. Only small molecules can diffuse through the alginate matrix [43]. L. ivanovii cells entrapped in alginate beads are, therefore, protected against phages as well as against contamination by other bacteria. The production of phages after infection of the host bacteria likely only takes place on the beads’ surface and in the medium after the cells have been released from the matrix. In fact, we noticed that the structure of the alginate gel was rather loose and easily broken up at the periphery of the beads, where cells usually most actively grow. These cells were likely released into the medium and infected by phages.

While the process described here still requires optimisation, the gel entrapment of cells to produce specific phages offers the potential for the large-scale and rapid production of phages. Successive phage productions have shown that entrapped cells can be reused for at least four propagation cycles. Although the viral titer of lysate produced with entrapped cells was nearly 10-fold reduced compared to that of free-cell production, successive productions with the same beads should be globally seen as an interesting advantage. Continuous phage production using entrapped cells could be enhanced and applied to a large variety of phages.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alpha-Biotech Inc. and DAAD (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst) for providing financial assistance for this study. We also thank Claude Champagne for discussion. S.M. holds the Canada Research Chair in Bacteriophages.

Author Contributions

B.R. and J.G. conceived and designed the experiments; B.R. performed the experiments; B.R., M.J.L., J.G., and S.M. analysed the data; B.R., C.P., and S.M. wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Radoshevich L., Cossart P. Listeria monocytogenes: Towards a complete picture of its physiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;16:32–46. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frank F.J., Koffe A.R. Surface-adherent growth of Listeria monocytogenes is associated with increased resistance to surfactant sanitizers and heat. J. Food Protect. 1989;53:550–554. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-53.7.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Directorate-General for Health and Consumers . Assessment of the Antibiotic Resistance Effects of Biocides, 28th Plenary. Commission Européenne, Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks; Bruxelles, Belgium: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearce H., Messager S., Maillard J.-Y. Effect of biocides commonly used in the hospital environment on the transfer of antibiotic-resistance genes in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Hosp. Infect. 1999;43:101–108. doi: 10.1053/jhin.1999.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buttimer C., McAuliffe O., Ross R.P., Hill C., O’Mahony J., Coffey A. Bacteriophages and bacterial plant diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:34. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stalin N., Srinivasan P. Efficacy of potential phage cocktails against Vibrio harveyi and closely related Vibrio species isolated from shrimp aquaculture environment in the south east coast of India. Vet. Microbiol. 2017;207:83–96. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bai J., Kim Y.-T., Ryu S., Lee J.-H. Biocontrol and rapid detection of food-borne pathogens using bacteriophages and endolysins. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:474. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abedon S.T. Phage therapy of pulmonary infections. Bacteriophage. 2015;5:e1020260. doi: 10.1080/21597081.2015.1020260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagens S., Loessner M.J. Phages of Listeria offer novel tools for diagnostics and biocontrol. Front. Microbiol. 2014;5:159. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin D.M., Koskella B., Lin H.C. Phage therapy: An alternative to antibiotics in the age of multi-drug resistance. World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017;8:162–173. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i3.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loessner M.J., Busse M. Bacteriophage typing of Listeria species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1990;56:1912–1918. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.6.1912-1918.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guenther S., Huwyler D., Richard S., Loessner M.J. Virulent bacteriophages for biocontrol of Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:93–100. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01711-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klumpp J., Dorscht J., Lurz R., Bielmann R., Wieland M., Zimmer M., Calendar R., Loessner M.J. The terminally redundant, non-permuted genome of Listeria bacteriophage A511: A model for the SPO1-like myoviruses of Gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:5753–5765. doi: 10.1128/JB.00461-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva E.N.G., Figueiredo A.C.L., Miranda F.A., de Castro Almeida R.C. Control of Listeria monocytogenes growth in soft cheeses by bacteriophage P100. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2014;45:11–16. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822014000100003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaitiemwong N., Hazeleger W.C., Beumer R.R. Inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes by disinfectants and bacteriophages in suspension and stainless-steel carrier tests. J. Food Protect. 2014;77:2012–2020. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chibeu A., Agius L., Gao A., Sabour P.M., Kropinski A.M., Balamurugan S. Efficacy of bacteriophage LISTEX™P100 combined with chemical antimicrobials in reducing Listeria monocytogenes in cooked turkey and roast beef. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013;167:208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miguéis S., Saraiva C., Esteves A. Efficacy of LISTEX P100 at different concentrations for reduction of Listeria monocytogenes inoculated in sashimi. J. Food Protect. 2017;12:2094–2098. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-17-098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greer G.G. Homologous bacteriophage control of Pseudomonas growth on beef spoilage. J. Food Protect. 1986;49:104–109. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-49.2.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganegama Arachchi G.J., Cridge A.G., Dias-Wanigasekera B.M., Cruz C.D., McIntyre L., Liu R., Flint S.H., Mutukumira A.N. Effectiveness of phages in the decontamination of Listeria monocytogenes adhered to clean stainless steel, stainless steel coated with fish protein, and as a biofilm. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013;10:1105–1116. doi: 10.1007/s10295-013-1313-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gray J.A., Chandry P.S., Kaur M., Kocharunchitt C., Bowman J.P., Fox E.M. Novel biocontrol methods for Listeria monocytogenes biofilms in food production facilities. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:605. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roy B., Ackermann H.-W., Pandian S., Picard G., Goulet J. Biological inactivation of adhering Listeria monocytogenes by listeriaphages and a quaternary ammonium compound. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993;59:2914–2917. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.9.2914-2917.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee S., Kim M.G., Lee H.S., Heo S., Kwon M., Kim G. Isolation and characterization of Listeria phages for control of growth of Listeria monocytogenes in milk. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2017;37:320–328. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2017.37.2.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agboluaje M., Sauvageau D. Bacteriophage production in bioreactors. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018;1692:173–193. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7395-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sargeant K., Yeo K.G., Lethbridge J.H., Shooter K.V. Production of bacteriophage T7. Appl. Microbiol. 1968;16:1483–1488. doi: 10.1128/am.16.10.1483-1488.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen B.Y., Lim H.C. Bioreactor studies on temperature induction of the Qmutant of bacteriophage λ in Escherichia coli. J. Biotechnol. 1996;51:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(96)01571-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sauvageau D., Cooper D.G. Two-stage, self-cycling process for the production of bacteriophages. Microb. Cell Fact. 2010;9:81. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-9-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Los M., Wegrzyn G., Neubauer P. A role for bacteriophage T4 rI gene function in the control of phage development during pseudolysogeny and in slow growing host cells. Res. Microbiol. 2003;154:547–552. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(03)00151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park S.H., Park T.H. Analysis of two-stage continuous operation of Escherichia coli containing bacteriophage λ vector. Bioprocess Eng. 2000;23:187–190. doi: 10.1007/s004499900194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen X.A., Cen P.L. A novel three-stage process for continuous production of penicillin G acylase by a temperature-sensitive expression system of Bacillus subtilis phage phi105. Chem. Biochem. Q. 2005;19:367–372. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh J.S., Cho D., Park T.H. Two-stage continuous operation of recombinant Escherichia coli using the bacteriophage λ Q-vector. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2005;28:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00449-005-0418-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ziv N., Brandt N.J., Gresham D. The use of chemostats in microbial systems biology. J. Vis. Exp. 2013;80:50168. doi: 10.3791/50168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chao L., Levin B.R., Stewart F.M. A complex community in a simple habitat: An experimental study with bacteria and phage. Ecology. 1977;58:369–378. doi: 10.2307/1935611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwienhorst A., Lindemann B.F., Eigen M. Growth kinetics of a bacteriophage in continuous culture. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1996;50:217–221. doi: 10.1002/bit.260500204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nabergoj D., Kuzmić N., Drakslar B., Podgornik A. Effect of dilution rate on productivity of continuous bacteriophage production in cellstat. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018;102:3649–3661. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-8893-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diviès C., Prévost H., Cavin J.F. Les bactéries immobilisées dans l’industrie laitière. Process. Mag. 1989;1041:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gacesa P. Alginates. Carbohydr. Polym. 1988;53:161–182. doi: 10.1016/0144-8617(88)90001-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ackermann H.-W., Dubow M.S. Viruses of Prokaryotes. Volume 1. CRC Press, Inc.; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 1987. Phage multiplication; pp. 49–85. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahony J., Tremblay D.M., Labrie S.J., Moineau S., van Sinderen D. Investigating the requirement for calcium during lactococcal phage infection. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015;201:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gosmann B., Rehm H.J. Influence of growth behaviour and physiology of alginate-entrapped microorganisms on the oxygen consumption. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1988;29:554–559. doi: 10.1007/BF00260984. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cachon R., Catté M., Nommé R., Prévost H., Diviès C. Kinetic behaviour of Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis bv. diacetylactis immobilized in calcium alginate gel beads. Process Biochem. 1995;6:503–510. doi: 10.1002/bit.260470509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prévost H., Diviès C., Rousseau E. Continuous yoghurt production with Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus entrapped in Ca-alginate. Biotechnol. Lett. 1985;4:247–252. doi: 10.1007/BF01042371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Audet P., Paquin C., Lacroix C. Immobilized growing lactic acid bacteria with κ-carrageenan—Locust bean gum gel. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1988;1:11–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00258344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steenson L.R., Klaenhammer T.R., Swaisgood H.E. Calcium alginate-immobilized cultures of lactic streptococci are protected from bacteriophages. J. Dairy Sci. 1987;70:1121–1127. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(87)80121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Champagne C.P., Morin N., Couture R., Gagnon C., Jelen P., Lacroix C. The potential of immobilized cell technology to produce freeze-dried, phage-protected cultures of Lactococcus lactis. Food Res. Intern. 1992;25:419–427. doi: 10.1016/0963-9969(92)90166-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Champagne C.P., Moineau S., Lafleur S., Savard T. The effect of bacteriophages on the acidification of a vegetable juice medium by microencapsulated Lactobacillus plantarum. Food Microbiol. 2017;63:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2016.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanaka H., Matsumura M., Veliky I.A. Diffusion characteristics of substrates in Ca alginate gel beads. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1984;1:53–58. doi: 10.1002/bit.260260111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zink R., Loessner M.J. Classification of virulent and temperate bacteriophages of Listeria spp. on the basis of morphology and protein analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992;58:296–302. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.1.296-302.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ackermann H.-W., Dubow M.S. Viruses of Prokaryotes. Volume 1. CRC Press, Inc.; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 1987. Description and identification of new phages; pp. 103–142. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ortel S., Ackermann H.-A. Morphologie von Neuen Listeriaphagen. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Mikrobiol. Hyg. Ser. A Med. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. Virol. Parasitol. 1985;260:423–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adams M.H. Bacteriophages. Interscience Publishers, Inc.; New York, NY, USA: 1959. Methods of study of bacterial viruses; pp. 443–457. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boyaval P., Lebrun A., Goulet J. Étude de l’immobilisation de Lactobacillus helveticus dans des billes d'alginate de calcium. Le Lait. 1985;65:185–199. doi: 10.1051/lait:1985649-65013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Börner R.A., Aliaga M.T.A., Mattiasson B. Microcultivation of anaerobic bacteria single cells entrapped in alginate microbeads. Biotechnol. Lett. 2013;35:397–405. doi: 10.1007/s10529-012-1094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kurosawa H., Matsumura M., Tanaka H. Oxygen diffusivity in gel beads containing viable cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1989;34:926–932. doi: 10.1002/bit.260340707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen K.-C., Huang C.-T. Effects of the growth of Trichosporon cutaneum in calcium alginate gel beads upon bead structure and oxygen transfer characteristics. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 1988;10:284–292. doi: 10.1016/0141-0229(88)90129-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ogbonna J.C., Amano Y., Nakamura K. Elucidation of optimum conditions for immobilization of viable cells by using calcium alginate. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1989;67:92–96. doi: 10.1016/0922-338X(89)90186-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klumpp J., Loessner M.J. Listeria phages: Genomes, evolution, and application. Bacteriophage. 2013;3:e26861. doi: 10.4161/bact.26861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ackermann H.-W. Bacteriophage taxonomy. Microbiol. Aust. 2011;32:90–94. [Google Scholar]