Abstract

A hairpin ribozyme, RzCR2A, directed against position 323 of the hepatitis C virus 5′-untranslated region (HCV 5′-UTR) was used to establish and validate a novel method for the detection of cellular target molecules for hairpin ribozymes, termed C-SPACE (cleavage-specific amplification of cDNA ends). For C-SPACE, HeLa mRNA containing the transcript of interest was subjected to in vitro cleavage by RzCR2A in parallel with a control ribozyme, followed by reverse transcription using a modified SMART cDNA amplification method and cleavage-specific PCR analysis. C-SPACE allowed identification of the RzCR2A target transcript from a mixture containing the entire cellular mRNA while only requiring knowledge of the ribozyme binding sequence for amplification. In a similar approach, C-SPACE was used successfully to identify human 20S proteasome α-subunit PSMA7 mRNA as the cellular target RNA of Rz3′X, a ribozyme originally designed to cleave the negative strand HCV 3′-UTR. Rz3′X was found to substantially inhibit HCV internal ribosome entry site (IRES) activity and PSMA7 was subsequently confirmed to be involved in HCV IRES-mediated translation. Thereby, C-SPACE was validated as a powerful tool to rapidly identify unknown target RNAs recognized and cleaved by hairpin ribozymes.

INTRODUCTION

Ribozymes (Rz) are small catalytic RNA molecules that have been developed and designed to specifically recognize and efficiently cleave RNA molecules with sequences complementary to the ribozyme substrate-binding arms. The cleaved target mRNA is destabilized and subjected to intracellular degradation. Consequently, expression of this specific gene and synthesis of the encoded protein are prevented. Most investigators have utilized hammerhead and hairpin ribozymes, because their small sizes (35–65 nt) are easily manipulated or synthesized chemically. Because of their simple structures and site-specific cleavage activity, ribozymes have been widely exploited in studies of genes relevant to a broad spectrum of diseases, including cancer development, metastasis, drug resistance and viral infections (reviewed in 1–4). Ribozymes can be used as a tool for RNA/gene inactivation in vitro, in cell culture (5–8) and in animals (9). These studies have significantly improved our knowledge about target-specific optimization, delivery, stability and intracellular localization of ribozymes required for successful clinical application (10–12). Optimal design and experimental protocols for a hairpin ribozyme to specifically cleave the target sequence have been developed (13–15). Additionally, techniques have been presented for in vitro selection of ribozymes with improved characteristics from complex starting populations (most based on two RNA-catalyzed reactions, cleavage and ligation) (16–19). Intracellular ribozyme-mediated cleavage of substrate RNAs can be assessed indirectly by the use of non-cleaving ribozymes or non-cleavable substrates as controls, and directly by analysis of RNA expression using northern blotting (20), RNase protection assays (21), reverse transcription–PCR (RT–PCR) (22,23), reverse ligation-mediated PCR (RL–PCR) (24) or real-time RT–PCR (25). However, even though RT–PCR-based methods are generally very sensitive, rapid degradation of the 5′- and 3′-ribozyme cleavage products reduces their abundance compared with uncleaved substrate, making accurate quantification difficult. Furthermore, all these methods require knowledge of the sequence of the 5′- and 3′-cleavage products and are therefore not suitable for the detection of unknown genes. The aim of our study was to rapidly identify unknown target RNAs recognized and cleaved by hairpin ribozymes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction

Plasmid pHyg-5′-C was constructed as described previously (26). To generate plasmid RL-5′C-FL, PCR amplification was performed with oligonucleotide primers P1 (5′-gcaagcttgaattcgccagccccctgatgggggcg-3′) and P3 (5′- ctgatctcatgaaggctgaagcgggcacagtcag-3′), then digested with EcoRI and BspHI and inserted into pGL3RL (kindly provided by Anne E. Willis, Department of Biochemistry, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK) following digestion with EcoRI and NcoI. The Moloney retroviral genome-based expression plasmid pLHPM contains a ribozyme expression cassette driven by the tRNAVal promoter as described previously (26).

In vitro cleavage of HCV substrates by hairpin ribozymes

Plasmid pT7-5′-C (27) [containing a T7 RNA promoter recognition sequence upstream of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) 5′-UTR and core sequence] digested with EcoRI was used for in vitro transcription of long CR2A substrate RNA (892 nt) as described previously (28). Similarly, long substrate RNA (202 nt) for CR13 cleavage was generated by in vitro transcription from a PCR fragment (M1, 5′-gttaatacgactcactataggtacccttggcccctctatgg-3′; M2, 5′-agcgcctccaagaggggcgcc-3′). Short substrates for in vitro cleavage and ribozymes were generated by annealing specific oligonucleotides for each ribozyme with a ‘universal’ oligonucleotide containing the recognition sequence for the T7 RNA polymerase promoter as a template for in vitro transcription (26) (MEGAShortScript T7 in vitro transcription kit; Ambion, Austin, TX). In vitro cleavage of substrate RNA by hairpin ribozymes (Rz, 40 nM) was performed with the substrate (Sub, 200 nM) in a buffer containing 12 mM MgCl2, 2 mM spermidine, 40 mM Tris–HCl in a final volume of 10 µl. Following incubation at 37°C for 3 h, reactions were terminated by addition of 1 vol of formamide gel loading buffer (80% formamide, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 0.1% xylene cyanol, 2 mM EDTA). Products of the cleavage reactions were resolved by electrophoresis on 15% (short substrate) or 5% (long substrate) denaturing polyacrylamide/7 M urea gels. Analysis was performed by autoradiography and phosphorimager analysis (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) with computer-assisted densitometry (ImageQuant Software).

Cell culture and transfections

Human cervical carcinoma cells (HeLa) and hepatoblastoma cells (Huh7) were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (HyClone), 1% penicillin–streptomycin, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, non-essential amino acids (all Gibco). Plasmid pHyg-5′-C was transfected into HeLa cells using a calcium phosphate technique (CalPhos; Clontech). Stable clones were selected and characterized for core protein expression and a clone with moderate expression was chosen to harvest mRNA for cleavage-specific amplification of cDNA ends (C-SPACE). For luciferase assays Huh7 cells were transfected with plasmids pRL-5′C-FL (0.3 µg/cm2) and pLHPM (0.3 µg/cm2). Renilla and firefly luciferase expression were analyzed by dual luciferase assay (Promega) 72 h after transfection in a luminometer (Lumat LB9507; Perkin Elmer Life Sciences) and the ratio of Renilla/firefly luciferase measured compared with control RzBR1-transfected cells.

Ribozyme cleavage-based target gene identification using C-SPACE

Total RNA was extracted from HeLa cells stably expressing the bicistronic transcript Hyg-5′-C (expressing the transcript targeted by RzCR2A). mRNA was purified using an oligo(dT)–magnetic bead technique according to the manufacturer’s instructions (polyATtract mRNA isolation system; Promega) and quantified spectrophotometrically. In vitro cleavage was performed using the following conditions: denaturation of 750 ng mRNA and 300 ng ribozyme RNA (total volume 7 µl) at 75°C for 5 min; addition of 1 mM DTT, 40 U RNase inhibitor and cleavage buffer (12 mM MgCl2, 2 mM spermidine, 40 mM Tris–HCl, final volume 10 µl) and incubation for 10 subsequent cycles at 37°C for 20 min, then 70°C for 60 s. First strand reaction of this (cleaved) poly(A)+ RNA template was primed by a modified oligo(dT) primer [oligo(dT)-TAG, 0.67–1 µM; IDT, Coralville, IA] in the presence of the switching mechanism at 5′-end of RNA template (SMART) II oligonucleotide (0.67 µM; Clontech) and catalyzed by MMLV reverse transcriptase (Superscript II; Gibco) using standard conditions. Following cDNA synthesis, RNase H treatment was performed using DNase-free RNase H (Promega) at a concentration of 0.2 U/µl at 37°C for 20 min. cDNA was purified using a PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and resuspended in 100 µl of water. Amplification was performed using the single-stranded cDNA as a template with primers derived from the sequence of the ribozyme substrate-binding domain linked to the SMART oligonucleotide sequence together with the TAG primer. Primers for C-SPACE on Rz3′X-cleaved mRNA are described in detail elsewhere (M.Krüger et al., Mol. Cell. Biol., in press). Oligonucleotide primers CR2A, M2, TAG, SMCR2A-27/2, SMCR2A-8/8 and SMCR2A-5/6 (IDT) were used for PCR amplification (Table 1). PCR was carried out with 5 µl of cDNA, 1 µl of each primer (3 µM), 2.5 µl of 10× PCR buffer without MgCl2 (PE Biosystems), 2.5 µl of MgCl2 (25 mM), 100µm dNTP, 2.5 µl of DMSO (100%) and 0.5 µl of AmpliTaq Gold (PE Biosystems) in a final volume of 25 µl. The temperature profile was initial denaturation at 94°C for 7 min followed by 50 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 60°C for 30 s and 72°C for 150 s, with terminal extension at 72°C for 7 min (GeneAmp PCR System 2400; PE Biosystems). PCR products were separated by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and recovered by gel extraction (Qiagen). Fragments were cloned into T/A-type PCR cloning vectors (pCR2.1; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) analyzed by restriction digestion and sequenced using Sequenase (US Biochemical) as well as automated sequencing.

Table 1. Sequences of primers used for C-SPACE.

| Primer name |

Primer sequence (5′→3′) |

| Oligo(dT)-TAG | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTACTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTVa |

| TAG | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTACT |

| M2 | CCCTGTTGCGTAGTTCACGCCGTC |

| CR2A | CGGGAGGTCTCGTAGACC |

| SMCR2A-27/2 | AAGCAGTGGTAACAACGCAGAGTACGCGGGGTCTC |

| SMCR2A-8/8 | GAGTACGCGGGGTCTCGTAGAC |

| SMCR2A-5/6 | TACGCGGGGTCTCGTAG |

aV, any nucleotide except T.

RESULTS

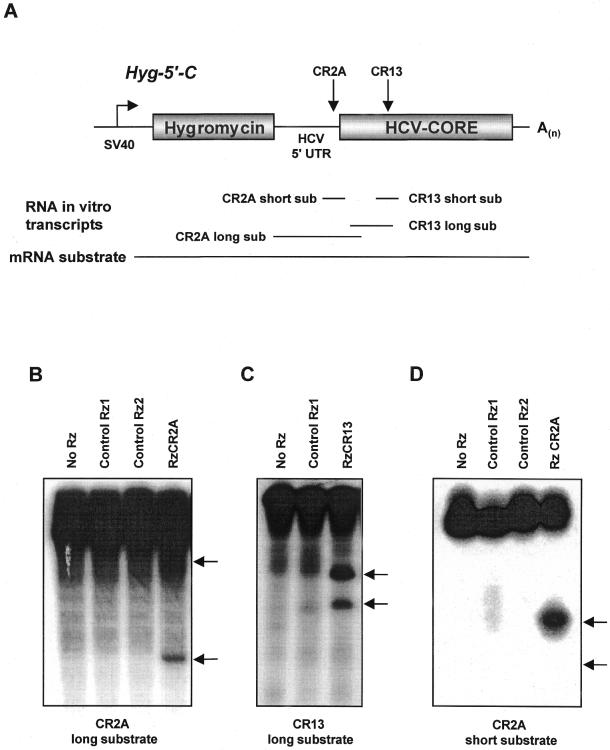

Identification of a hairpin ribozyme with high catalytic activity on HCV RNA

We have tested various hairpin ribozymes directed against conserved hairpin recognition sites (GUC triplet) within the HCV genome for their in vitro and in vivo cleavage activities on corresponding short or long RNA substrates (data not shown; 27). Two ribozymes were particularly active against HCV RNA, RzCR2A (position 323 of HCV consensus sequence, 5′-UTR) and RzCR13 (position 705, within the core coding region) (Fig. 1A). Both ribozymes substantially cleaved long substrate RNA in vitro (Fig. 1B and C) as well as short substrate RNA (Fig. 1D, data not shown for RzCR13). Additionally, the intracellular cleavage activity of these ribozymes was confirmed in co-transfection experiments on a bi-cistronic reporter system with cap-dependent translation of the Renilla luciferase gene and HCV 5′-UTR allowing for internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-mediated translation of the HCV core and firefly luciferase genes (data not shown).

Figure 1.

In vitro cleavage of long or short HCV RNA transcripts by RzCR2A and RzCR13. To analyze ribozyme activity in vitro, long and short RNA transcripts (sub) comprising recognition sites for hairpin ribozymes RzCR2A and RzCR13 were generated as schematically depicted (A). Ribozymes RzCR2A, RzCR13 as well as two control ribozymes (40 nM) were incubated separately with long (200 nM) (B and C) or short (200 nM) substrate (D) at 37°C for 3 h. Reactions were resolved on 5% (long substrate) or 15% (short substrate) denaturing polyacrylamide/7 M urea gels. Uncleaved substrate RNA and the 5′- and 3′-cleavage products are indicated. The 3′-fragment of CR2A short substrate is not visible on the gel since it does not contain radiolabeled rUTP (D).

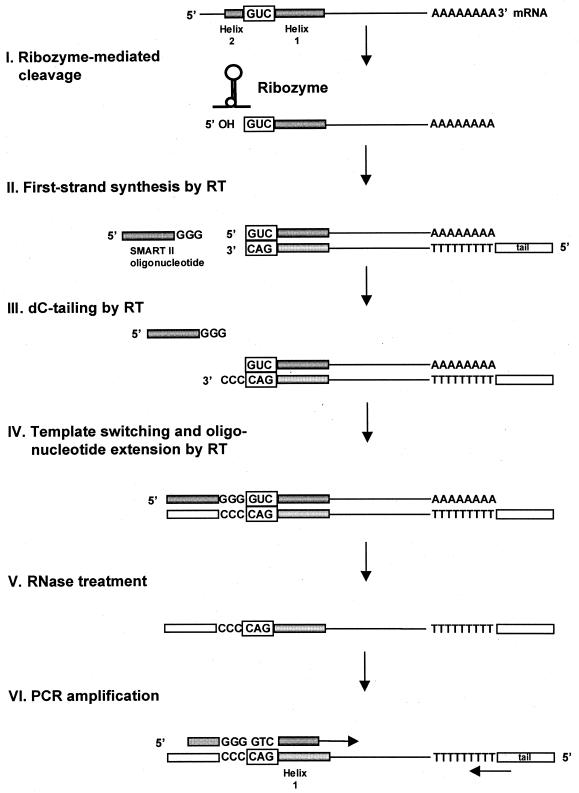

C-SPACE: ribozyme cleavage-based target gene identification

The aim of C-SPACE was to facilitate the identification of unknown genes targeted by particular ribozymes. Therefore, cellular mRNA was isolated and in vitro cleavage was performed (Fig. 2, I), presumably generating multiple cleaved RNAs with GUC triplets at the 5′-end. First strand reaction of this poly(A)+ RNA template was primed by a modified oligo(dT) primer in the presence of the SMART II oligonucleotide and catalyzed by MMLV reverse transcriptase (Fig. 2, II). When the reverse transcriptase reaches the 5′-end of the mRNA, the terminal transferase activity of the enzyme adds a few deoxycytidine (dC) nucleotides to the 3′-end of the cDNAs derived from both cleaved and uncleaved RNAs, (Fig. 2, III). Annealing of the SMART II oligonucleotide with the C-rich motif and template switching by MMLV reverse transcriptase result in single-stranded cDNA containing the complete 5′-end of the mRNA template, as well as the sequence complementary to the SMART II oligonucleotide (Fig. 2, IV). For cleaved RNA fragments, this attached sequence is located next to the ‘CAG’ reverse transcribed from the ribozyme recognition triplet ‘GUC’ at the cDNA 3′-end. Following RNase treatment (Fig. 2, V), the SMART II oligonucleotide sequence, attached C residues, and the known sequence of the adjacent helix 1 serve as a binding site for oligonucleotide primers. Finally, PCR amplification is performed using this primer together with a primer binding to the tail (tag) of the oligo(dT) primer (TAG) (Fig. 2, VI).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of C-SPACE for ribozyme-mediated target gene identification. HeLa mRNA containing the transcript of interest is subjected to in vitro cleavage by a particular hairpin ribozyme along with a control ribozyme reaction. Ribozyme-mediated cleavage is followed by reverse transcription using a modified SMART cDNA amplification method (Clontech) and cleavage-specific PCR analysis (for details see text).

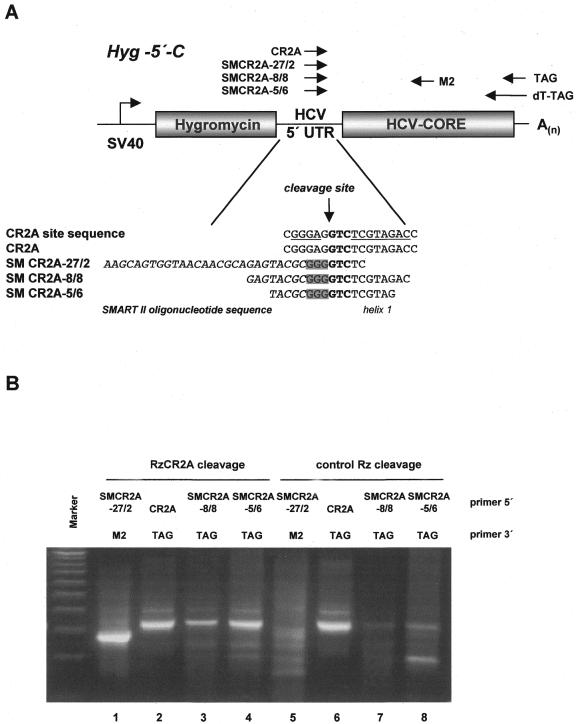

Optimization of C-SPACE using RzCR2A ribozyme-mediated cleavage as a model

To establish C-SPACE for detection of ribozyme target RNAs, we used RzCR2A to cleave the corresponding recognition sequence within the HCV 5′-UTR of a cellular RNA transcript. We generated a HeLa cell line stably expressing a bi-cistronic transcript consisting of the hygromycin B phosphotransferase gene (Hyg) followed by the HCV 5′-UTR directing translation of the HCV core gene (compare Fig. 1A). mRNA was extracted from this cell line and in vitro cleavage was performed with RzCR2A along with a control ribozyme (RzBR1) incubated under the same conditions. Following first strand synthesis, dC-tailing and SMART extension, a set of oligonucleotides (Fig. 3A) used for control amplification independent of transcript cleavage (CR2A-TAG) revealed a product for RzCR2A-cleaved samples as well as the control ribozyme reactions (Fig. 3B, lanes 2 and 6). In contrast, using a 5′-primer (SMCR2A-27/2) extending mainly into the SMART II oligonucleotide sequence together with a transcript-specific 3′-primer (M2), an amplification product was only obtained for RzCR2A-cleaved RNAs (Fig. 3B, lane 1) and not for control Rz-cleaved RNAs (Fig. 3B, lane 5), demonstrating the presence of a cleavage-derived transcript that contained the SMART II sequence. However, amplification of the RNAs with SMCR2A-27/2 and the 3′-TAG primer did not lead to a cleavage-specific band (data not shown), suggesting that this combination of primers lacks specificity.

Figure 3.

Optimization of C-SPACE using RzCR2A-mediated cleavage of HeLa mRNA. (A) mRNA was obtained from a HeLa cell line stably expressing a bi-cistronic hygromycin–HCV 5′-UTR–core RNA transcript. Several oligonucleotide primers were used for amplification of C-SPACE products derived from cleavage by RzCR2A or the control RzBR1. The RzCR2A recognition sequence within the HCV 5′-UTR is underlined. The cleavage site located 5′ of the GUC triplet (bold) is indicated by an arrow and G residues resulting from dC-tailing by reverse transcriptase are shaded. (B) C-SPACE amplification products were resolved on a 2% agarose gel and combinations of 5′- and 3′-oligonucleotides used for PCR are indicated. Control amplification for detection of uncleaved HCV substrate was performed with primers CR2A and TAG (lanes 2 and 6) or with CR2A and M2 (not shown). A 100 bp DNA ladder (Gibco BRL) is loaded to the left. Specific amplification was achieved using the 5′-primer SMCR2A5/6 with the 3′-universal TAG oligonucleotide (lane 4).

Therefore, different lengths of primers extending either into the region downstream of the RzCR2A cleavage site or upstream into the SMART II oligonucleotide sequence were tested for specific amplification of the target cDNA derived from RzCR2A cleavage in combination with an oligo(dT)–tag-specific primer (TAG) (Fig. 3A). Amplification products from the cellular RNA incubated with RzCR2A were compared with bands derived from reactions incubated with the control ribozyme (Fig. 3B). We found efficient amplification for RzCR2A-cleaved substrate using oligonucleotide SMCR2A5/6 with 6 nt 3′ of the GUC recognition triplet and 5 nt of the SMART II sequence 5′ of the G residues, whereas little amplification product was detected for cDNAs from the control reaction (Fig. 3B). Specific amplification products in RzCR2A-cleaved samples were recovered and confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing (data not shown). Thereby, based on the known binding sequence of RzCR2A, the target RNA (HCV 5′-UTR) preferentially cleaved by this ribozyme was identified from a complex mixture of cellular mRNAs.

DISCUSSION

We have established a novel method of target gene identification based on in vitro ribozyme cleavage of cellular mRNA. A few attempts to detect ribozyme cleavage products have been described (20–25,29), but generally it is believed that ribozyme cleavage products are rapidly degraded intracellularly and are therefore difficult to detect. The system described here is based on in vitro cleavage with either the hairpin ribozyme of interest or a control ribozyme on poly(A)+ RNA extracted from a target cell. Cleavages are performed on full-length RNAs that (at least in part) maintain their secondary structures in vitro. Total RNA content of the cleavage reactions needs to be optimized, depending on the estimated abundance of the substrate transcript, since we found higher concentrations of cellular RNA (as well as higher Rz concentrations) to be inhibitory to the reaction. While developing this method, we explored the use of a tagged poly(G) oligonucleotide and terminal transferase to add C residues to the cDNA 3′-end. However, this reaction was found to be less reliable compared with dC-tailing by MMLV reverse transcriptase in combination with SMART II oligonucleotide in the RT reaction. We chose MMLV reverse transcriptase because it preferentially adds between three and five terminal C residues and is functional at 37–50°C.

Since we attempted to generate this method for unknown genes, we used a lock-docking tagged oligo(dT) primer instead of a sequence-specific primer for reverse transcription. The tag primer (TAG) was found to minimize non-specific amplification. The tag sequence can be optimized for false priming sites and potential hairpin or primer dimer formation and can be modified to match a desired melting temperature (Tm) for the target site of interest. We obtained the most specific amplification for primer SMCR2A-5/6, probably since 5 nt of the SMART sequence minimized non-specific amplification (the majority of cDNAs in this reaction share the SMART sequence at the 3′-end). In addition, the use of only 6 nt of helix 1 allowed us to detect targets with mismatches at the outer positions of helix 1 that might be recognized and efficiently cleaved by hairpin ribozymes (30). While short PCR products are more likely to be amplified and might therefore be over-represented in the PCR reaction, cycling conditions should allow sufficient extension of long products. The unique 5′-sequence of the first round amplification product (SMART II sequence flanking the G residues and helix 1 of the ribozyme) and the oligo(dT)–TAG 3′-sequence allows additional amplifications by nested/semi-nested primers to enhance the signal of low prevalent amplification products.

We have applied this system to successfully identify a gene involved in HCV IRES-mediated translation (M.Krüger et al., Mol. Cell. Biol., in press). In this study we have performed in vitro cleavage of HeLa mRNA by a ribozyme Rz3′X that inhibits HCV IRES activity and subsequently applied C-SPACE for identification of ribozyme cleavage-specific target RNAs. Again, we used 6 nt of helix 1 and 5 nt of the extended SMART II sequence in combination with the tag primer for oligo(dT). A 290 nt product unique to Rz3′X-cleaved mRNA was identified (data not shown). Cloning and sequencing of this band revealed partial sequence (nucleotides 652–893) of the human 20S proteasome α-subunit PSMA7 mRNA (31). Subsequently, involvement of PSMA7 in intracellular HCV IRES-mediated translation was demonstrated. Thereby, the predictive value of in vitro cleavage detection by C-SPACE was further validated. Although this system is primarily aimed at gene identification, combining C-SPACE with real-time quantitative RT–PCR might allow precise quantitation of ribozyme-mediated cleavage of given substrates.

C-SPACE can also be used in combination with another powerful approach for gene discovery. Recently, we introduced a novel method of gene identification called ‘Inverse Genomics’ based on the use of a hairpin ribozyme library with randomized target recognition sequences cloned into retroviral vectors. We have used Inverse Genomics successfully in different experimental systems for the discovery of: (i) genes regulating the BRCA1 promoter (30); (ii) cellular cofactors for HCV IRES activity (26); (iii) genes involved in anchorage-independent cell growth control (32); and (iv) genes involved in suppression of fibroblast transformation (33). Ribozymes that repeatedly conferred distinct cellular phenotypes were amplified in these different cellular selection systems. Single ribozyme candidates were identified and the binding sequence flanking the GUC site required for ribozyme cleavage was used to obtain partial sequence information of the target gene responsible for the observed phenotype. However, for some ribozymes we failed to identify corresponding cellular target genes by database searches in non-redundant or EST databases or by using gene cloning strategies such as conventional 3′- or 5′-RACE with oligonucleotide primers derived from ribozyme binding sequences. Using the C-SPACE procedure described here, we were able to identify a cellular gene as target for a ribozyme that was involved in down-regulation of the BRCA1 gene in sporadic breast and ovarian cancer (C.Beger et al., manuscript in preparation). Thus, C-SPACE as a fast and easy to perform technique of hairpin ribozyme-mediated target gene identification underlines the potential of ribozymes as valuable tools for inhibiting the expression of genes relevant to a broad spectrum of human disorders.

References

- 1.Muotri A.R., da Veiga Pereira,L., dos Reis Vasques,L. and Menck,C.F. (1999) Ribozymes and the anti-gene therapy: how a catalytic RNA can be used to inhibit gene function. Gene, 237, 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beger C., Krüger,M. and Wong-Staal,F. (1998) Ribozymes in cancer gene therapy. In Lattime,E.C. and Gerson,S.L. (eds), Gene Therapy of Cancer. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, pp. 139–152.

- 3.James H.A. (1999) The potential application of ribozymes for the treatment of hematological disorders. J. Leukoc. Biol., 66, 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welch P.J., Barber,J.R. and Wong-Staal,F. (1998) Expression of ribozymes in gene transfer systems to modulate target RNA levels. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., 9, 486–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Folini M., Colella,G., Villa,R., Lualdi,S., Daidone,M.G. and Zaffaroni,N. (2000) Inhibition of telomerase activity by a hammerhead ribozyme targeting the RNA component of telomerase in human melanoma cells. J. Invest. Dermatol., 114, 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuchida T., Kijima,H., Hori,S., Oshika,Y., Tokunaga,T., Kawai,K., Yamazaki,H., Ueyama,Y., Scanlon,K.J., Tamaoki,N. and Nakamura,M. (2000) Adenovirus-mediated anti-K-ras ribozyme induces apoptosis and growth suppression of human pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Gene Ther., 7, 373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki T., Anderegg,B., Ohkawa,T., Irie,A., Engebraaten,O., Halks-Miller,M., Holm,P.S., Curiel,D.T., Kashani-Sabet,M. and Scanlon,K.J. (2000) Adenovirus-mediated ribozyme targeting of HER-2/neu inhibits in vivo growth of breast cancer cells. Gene Ther., 7, 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macejak D.G., Jensen,K.L., Jamison,S.F., Domenico,K., Roberts,E.C., Chaudhary,N., von Carlowitz,I., Bellon,L., Tong,M.J., Conrad,A., Pavco,P.A. and Blatt,L.M. (2000) Inhibition of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-RNA-dependent translation and replication of a chimeric HCV poliovirus using synthetic stabilized ribozymes. Hepatology, 31, 769–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavco P.A., Bouhana,K.S., Gallegos,A.M., Agrawal,A., Blanchard,K.S., Grimm,S.L., Jensen,K.L., Andrews,L.E., Wincott,F.E., Pitot,P.A., Tressler,R.J., Cushman,C., Reynolds,M.A. and Parry,T.J. (2000) Antitumor and antimetastatic activity of ribozymes targeting the messenger RNA of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors. Clin. Cancer Res., 6, 2094–2103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donahue C.P., Yadava,R.S., Nesbitt,S.M. and Fedor,M.J. (2000) The kinetic mechanism of the hairpin ribozyme in vivo: influence of RNA helix stability on intracellular cleavage kinetics. J. Mol. Biol., 295, 693–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunkel M. and Reither,V. (1999) Synthesis of 2′-C-alpha-difluoromethylarauridine and its 3′-O-phosphoramidite incorporation into a hammerhead ribozyme. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 9, 787–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sioud M. and Sorensen,D.R. (1998) A nuclease-resistant protein kinase C alpha ribozyme blocks glioma cell growth. Nat. Biotechnol., 16, 556–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu Q. and Burke,J.M. (1997) Design of hairpin ribozymes for in vitro and cellular applications. Methods Mol. Biol., 74, 161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hampel A., DeYoung,M.B., Galasinski,S. and Siwkowski,A. (1997) Design of the hairpin ribozyme for targeting specific RNA sequences. Methods Mol. Biol., 74, 171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hendry P., McCall,M.J. and Lockett,T.J. (1997) Characterizing ribozyme cleavage reactions. Methods Mol. Biol., 74, 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.zu Putlitz J., Yu,Q., Burke,J.M. and Wands,J.R. (1999) Combinatorial screening and intracellular antiviral activity of hairpin ribozymes directed against hepatitis B virus. J. Virol., 73, 5381–5387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu Q., Pecchia,D.B., Kingsley,S.L., Heckman,J.E. and Burke,J.M. (1998) Cleavage of highly structured viral RNA molecules by combinatorial libraries of hairpin ribozymes. The most effective ribozymes are not predicted by substrate selection rules. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 23524–23533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burke J.M. and Berzal-Herranz,A. (1993) In vitro selection and evolution of RNA: applications for catalytic RNA, molecular recognition and drug discovery. FASEB J., 7, 106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sargueil B. and Burke,J.M. (1997) In vitro selection of hairpin ribozymes. Methods Mol. Biol., 74, 289–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxena S.K. and Ackerman,E.J. (1990) Ribozymes correctly cleave a model substrate and endogenous RNA in vivo. J. Biol. Chem., 265, 17106–17109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinecke P., Herget,T. and Schreier,P.H. (1992) Expression of a chimeric ribozyme gene results in endonucleolytic cleavage of target mRNA and a concomitant reduction of gene expression in vivo. EMBO J., 11, 1525–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantor G.H., McElwain,T.F., Birkebak,T.A. and Palmer,G.H. (1993) Ribozyme cleaves rex/tax mRNA and inhibits bovine leukemia virus expression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 10932–10936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perriman R. (1997) The detection of hammerhead ribozyme cleavage by RT-PCR methods. Methods Mol. Biol., 74, 301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bertrand E., Fromont-Racine,M., Pictet,R. and Grange,T. (1997) Detection of ribozyme cleavage products using reverse ligation-mediated PCR (RL-PCR). Methods Mol. Biol., 74, 311–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein D., Denis,M., Ricordi,C. and Pastori,R.L. (2000) Assessment of ribozyme cleavage efficiency using reverse transcriptase real-time PCR. Mol. Biotechnol., 14, 189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krüger M., Beger,C., Li,Q.X., Welch,P.J., Tritz,R., Leavitt,M., Barber,J.R. and Wong-Staal,F. (2000) Identification of eIF2Bgamma and eIF2gamma as cofactors of hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation using a functional genomics approach. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 8566–8571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welch P.J., Tritz,R., Yei,S., Leavitt,M., Yu,M. and Barber,J. (1996) A potential therapeutic application of hairpin ribozymes: in vitro and in vivo studies of gene therapy for hepatitis C virus infection. Gene Ther., 3, 994–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krüger M., Beger,C. and Wong-Staal,F. (1999) Use of ribozymes to inhibit gene expression. Methods Enzymol., 306, 207–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albuquerque Silva J., Houard,S. and Bollen,A. (1998) Tailing cDNAs with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase in RT–PCR assays to identify ribozyme cleavage products. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 3314–3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beger C., Pierce,L.N., Krüger,M., Marcusson,E.G., Robbins,J.M., Welcsh,P., Welch,P.J., Welte,K., King,M.C., Barber,J.R. and Wong-Staal,F. (2001) Identification of Id4 as a regulator of BRCA1 expression by using a ribozyme-library-based inverse genomics approach. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 130–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang J., Kwong,J., Sun,E.C. and Liang,T.J. (1996) Proteasome complex as a potential cellular target of hepatitis B virus X protein. J. Virol., 70, 5582–5591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welch P.J., Marcusson,E.G., Li,Q.X., Beger,C., Krüger,M., Zhou,C., Leavitt,M., Wong-Staal,F. and Barber,J.R. (2000) Identification and validation of a gene involved in anchorage-independent cell growth control using a library of randomized hairpin ribozymes. Genomics, 66, 274–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Q.X., Robbins,J.M., Welch,P.J., Wong-Staal,F. and Barber,J.R. (2000) A novel functional genomics approach identifies mTERT as a suppressor of fibroblast transformation. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 2605–2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]