Abstract

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome refers to a spectrum of connective tissue disorders typically caused by mutations in genes responsible for the synthesis of collagen. Patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome often exhibit hyperflexibility of joints, increased skin elasticity, and tissue fragility. Vascular Ehlers-Danlos (vEDS) is a subtype of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome with a predilection to involve blood vessels. As such, it often manifests as vascular aneurysms and vessel rupture leading to hemorrhage. There are few reports describing primary prevention of aneurysms in the setting of undiagnosed, suspected vEDS. We present a case of a 30-year-old woman who presents with a pulsatile neck mass found to have multiple arterial aneurysms on imaging, hyperflexibility, and characteristic facial features consistent with vEDS. As described in this case, management of a suspected connective tissue disorder is a multidisciplinary approach including vascular surgery, medical therapy, and genetic testing to confirm the diagnosis. We review literature regarding the care of patients with vascular Ehlers-Danlos as it might pertain to hospitalized patients.

KEY WORDS: vascular, Ehlers-danlos, aneurysm

INTRODUCTION

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is a heterogeneous group of rare connective tissue disorders that often manifest with increased skin elasticity, joint hypermobility, and tissue fragility. Vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (vEDS) accounts for fewer than 5% of all Ehlers-Danlos cases 1. It is associated with an autosomal dominant mutation in COL3A1, responsible for the synthesis of type III collagen 2–4. Type III collagen composes connective tissue found within all organs. It provides tensile strength for organs that must resist permanent dilation from fluctuations in pressure. Consequently, vEDS typically presents as rapidly progressive arterial aneurysms, arterial rupture, bowel perforation, and uterine fragility 5–7. Suspicion often arises when incidental findings are identified on routine imaging studies 6. Definitive diagnosis requires identification of a heterozygous COL3A1 pathogenic genotype. We report the case of a young woman who was diagnosed with a rapidly enlarging arterial pseudoaneurysm, ultimately found to have vEDS, managed with open ligation of her external carotid artery.

CASE PRESENTATION

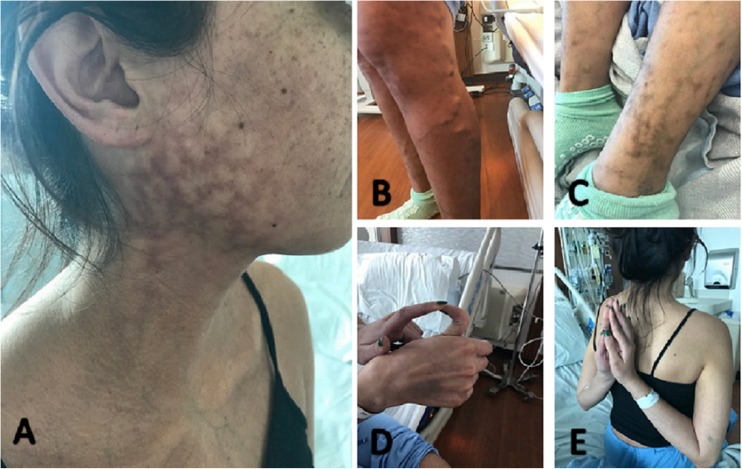

A 30-year-old woman with a history of bilateral varicose veins was admitted from otolaryngology clinic with a 3-week history of a painful, rapidly growing right neck mass. The patient was previously diagnosed with parotitis at an outside hospital but the neck mass continued to grow despite completion of a two-week course of cephalexin. She denied trauma or injury to her neck, jaw, or face. She denied fevers, chills, weight loss, visual changes, and arthralgias. The patient had a medical history of persistent bilateral varicose veins despite uncomplicated endovenous ablation 1 year prior to admission. She also had a remote history of colonic perforation secondary to a low-speed motor vehicle accident which required laparotomy and repair. She did note a history of easy bruising throughout her life. She had no family history of bleeding diathesis or connective tissue disease. On admission, her vitals were within normal limits. Her physical exam was significant for a 3-cm diameter pulsatile mass with surrounding edema of the right neck and mandible. There was a violaceous, reticular rash overlying the mass (Fig. 1a). Skin elasticity was normal. Her face had large eyes, a thin nose, thin lips and a small chin. She had bilateral severe varicose veins without lower extremity edema (Fig. 1b). Distal interphalangeal joints and shoulders were hyperextensible with multiple movements (Fig. 1d, e). Metacarpophalangeal joints hyperextended > 90°, hyperflexion of wrists approached 140°, and her knees achieved hyperextension > 15°. Cardiovascular, pulmonary, abdominal, and neurologic examinations were unremarkable. Complete blood count, electrolytes, serum creatinine, liver function tests, and international normalized ratio were within normal limits. Blood cultures were negative. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein were not elevated. Anti-nuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and complement levels were unremarkable.

Figure 1.

a Neck mass with overlying reticular rash. b Prominent varicose veins. c Easily identified veins suggestive of thin skin. d Interphalangeal joint hypermobility of the 1st digit. e Increased range of motion of shoulders.

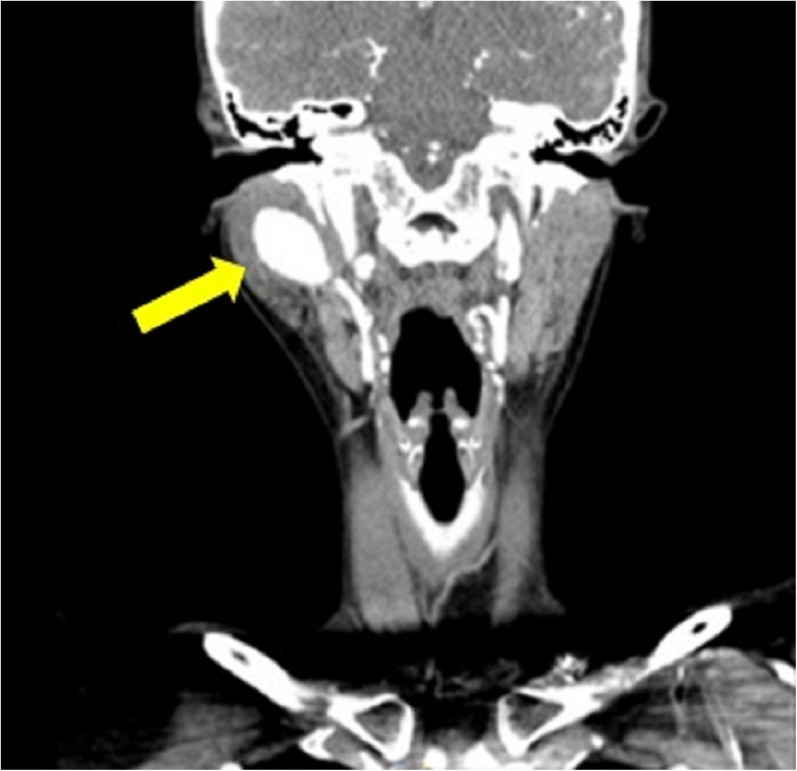

Computer tomography angiography (CTA) of the neck revealed a 2.7-cm aneurysm arising from the proximal right internal maxillary artery (Fig. 2) as well as a 4-mm aneurysm in the proximal right internal carotid artery. Brain CTA showed a 3-mm aneurysm of the left middle cerebral artery. Chest, abdomen, and pelvis CTA did not reveal any other aneurysms. Transthoracic echocardiography did not show mitral valve prolapse or other abnormalities.

Figure 2.

CTA demonstrating a large pseudoaneurysm of the maxillary artery.

Rheumatology, otolaryngology, interventional radiology, and vascular surgery were consulted. The patient’s clinical picture was thought to be most consistent with vEDS. After multidisciplinary discussions, the patient underwent an urgent open ligation of the maxillary and temporal artery via vascular surgery. The surgery was uncomplicated and the patient made a full recovery. Genetic testing was sent to confirm the diagnosis of vEDS. She was started on carvedilol, oral contraception, and was discharged with genetics follow-up and a CTA head and neck planned for 3 months after discharge.

Our patient was diagnosed with the COL3A1 gene mutation, confirming the diagnosis of vEDS. Ongoing screening of vascular lesions was determined on an individual basis by vascular surgery. The interval and modality depends on the location and size of lesions. Genetics was also consulted to discuss the risk of inheritance and pregnancy with the patient and her family.

DISCUSSION

Diagnosis of vEDS is challenging because of variable penetrance within families. A family history of connective tissue disease can be absent as haploinsufficiency and biallelic sequence variants lead to variable clinical presentations and severity of illness 7,8. De novo mutations in the COL3A1 gene are also a possibility as was suspected in our patient 9.

There are 5 major and 12 minor criteria that distinguish vEDS from other forms of Ehlers-Danlos and help to establish a clinical diagnosis 10. Of the major criteria—arterial vasculopathy at < 40 years of age, spontaneous colon or uterine rupture, unexplained carotid-cavernous sinus fistulization, and family history—our patient had bowel perforation despite minimal trauma and early-onset vasculopathy. Several minor criteria were also present including easy bruising, thin skin (indicated by visible veins), characteristic facial features, joint hypermobility, and early-onset varicose veins 10–12. Typical facial features include large eyes, small chin, lobeless ears, and thin nose and lips. However, characteristic facial features are often subtle and can be absent 13. Joint hypermobility can be assessed by the Beighton score, a standardized evaluation for generalized joint hypermobility 14. In patients with these features, vEDS should be suspected and genetic testing should be completed to confirm the diagnosis.

The diagnosis of vEDS is frequently delayed until after patients present with devastating sequelae. In one study, 61% of patients had at least one severe vascular complication prior to the age of 40 years 15. Our patient was initially misdiagnosed with parotitis, but she was fortunate to return to care with a visible pulsatile mass that was treated prior to arterial rupture. However, most vascular abnormalities—including arterial aneurysms, dissections, and ectasias—are not visible on physical examination and occur in visceral arteries and deep arteries of the head and neck 16. As such, practitioners should be aware that many patients first present with hemodynamic instability secondary to emergent internal bleeding. Although our patient was not bleeding, she was at high risk of rupture and urgent treatment of her aneurysm was necessary to prevent a catastrophic bleed.

The management of vascular complications in patients with vEDS is difficult. Endovascular procedures carry a significant risk of arterial dissection and aneurysm formation and are not typically recommended 17. However, there are case reports of successful endovascular procedures in affected patients 18,19. Our patient underwent open ligation of the external carotid artery rather than an endovascular approach in order to avoid arterial rupture and iatrogenic arterial damage. There is little evidence for effective medical management in vEDS. One randomized control trial demonstrated a significant reduction in arterial dissection and rupture with use of celiprolol, a β1-β2 receptor antagonist 20. Our patient was discharged on carvedilol with the hope that other beta-blockers may offer a similar protective benefit. Oral contraception was warranted to help prevent pregnancy given the risk of uterine rupture. Combined oral contraception was preferred because progestin-only contraceptives have been associated with worsening joint hypermobility 21.

Vascular Ehlers-Danlos has a relatively poor prognosis. The average life expectancy is 48 to 50 years. Patients typically die from acute arterial rupture leading to exsanguination 22. Despite treatment, our patient has other aneurysms that pose a significant risk of bleeding and will require close outpatient follow-up. Following vascular lesions with non-invasive imaging has been shown to be an effective tool for counseling patients about the risks and benefits of elective surgical repair. However, patients should also be counseled that close monitoring does not change overall mortality, as fatal lesions are typically rapidly expansive 23.

CONCLUSION

We describe a case of vEDS in a woman presenting with a pulsatile neck mass. This diagnosis requires a high degree of clinical suspicion and aggressive management to prevent catastrophic consequences. Clinicians should be aware that the vascular subtype can present with findings relatively dissimilar to the classic phenotype of Ehlers-Danlos. Endovascular approaches must be completed with caution and open ligation should be reserved for ruptured vessels or vessels in which rupture is imminent. Wider recognition of this unusual diagnosis will be essential to reducing the high morbidity and mortality associated with vEDS.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

The original version of this article was revised due to an open access cancellation, the open access team requests this paper be updated so open access licensing can be deleted from the published paper.

Change history

9/4/2018

The article was originally published electronically on the publisher’s internet portal (currently SpringerLink) with open access.

Change history

10/10/2018

This paper was inadvertently published with open access; the authors have requested the copyright revert to the society. It has been re-published with appropriate licensing.

References

- 1.Germain DP, Herrera-Guzman Y. Vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Ann Genet. 2004;47:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anngen.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barabas AP. Heterogeneity of the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Description of clinical types and a hypothesis to explain the basic defect BMJ. 1967;2:612–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5552.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barabas AP. Vascular complications in the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, with especial reference to the “arterial type” or Sack’s syndrome. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1972;13:160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pope FM, Martin GR, Lichtenstein JR, et al. Patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV lack type III collagen. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1975;72(4):1314–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.4.1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oderich GS, Panneton JM, Bower TC, et al. The spectrum, management and clinical outcome of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV: a 30-year experience. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42(1):98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamiya K, Yoshizu A, Kashizaki F. Vascular-type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome incidentally diagnosed at surgical treatment for hemothorax; report of a case. Kyobu Geka. 2013;66(2):173–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leistritz DF, Pepin MG, Schwarze U, et al. COL3A1 haploinsufficiency results in a variety of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV with delayed onset of complications and longer life expectancy. Genet Med. 2011;13(8):717–22. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182180c89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jørgensen A, Fagerheim T, Rand-Hendriksen S, et al. Vascular Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome in siblings with biallelic COL3A1 sequence variants and marked clinical variability in the extended family. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(6):796–802. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pepin M, Byers P. Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, Vascular Type. Gene Reviews. Initial Posting: September 2, 1999; Last Update: May 3, 2011.

- 10.Malfait F, Francomano C, Byers P, et al. The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers–Danlos syndromes. Am J Med Genet Part C Semin. Med Genet. 2017;175C:8–26. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beighton P, De Paepe A, Steinmann B, et al. Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: revised nosology, Villefranche, 1997. Am J Med Genet. 1998;77:31–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19980428)77:1<31::AID-AJMG8>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank M, Says J, Denarié N, et al. Successful segmental thermal ablation of varicose saphenous veins in a patient with confirmed vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Phlebology. 2016;31(3):222–4. doi: 10.1177/0268355515585048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inokuchi R, Kurata H, Endo K, et al. Vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome without the characteristic facial features: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93(28):e291. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smits-Engelsman B, Klerks M, Kirby A. Beighton score: A valid measure for generalized hypermobility in children. J Pediatr. 2011;158(119–123123):e111–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oderich GS, Panneton JM, Bower TC, et al. The spectrum, management and clinical outcome of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV: a 30-year experience. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zilocchi M, Macedo T, Oderich G, et al. Vascular Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: Imaging Findings. Am J Rad. 2007;189:712–719. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergqvist D, Björck M, Wanhainen A. Treatment of vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a systematic review. Annals of Surgery. 2013;258(2):257–261. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31829c7a59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linfante I, Lin E, Knott E, et al. Endovascular repair of direct carotid-cavernous fistula in Ehlers-Danlos type IV. J Neurointerv Surg. 2015;7(1):e3. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2013-010990.rep. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iida Y, Obitsu Y, Komai H, et al. Successful coil embolization for rupture of the subclavian artery associated with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50(5):1191–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ong KT, Perdu J, De Backer J, et al. Effect of celiprolol on prevention of cardiovascular events in vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a prospective randomised, open, blinded-endpoints trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9751):1476–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60960-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hugon-Rodin J, Lebegue G, Becourt S, et al. Gynecologic symptoms and the influence on reproductive life in 386 women with hypermobility type ehlers-danlos syndrome: a cohort study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11(1):124. doi: 10.1186/s13023-016-0511-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shields LBE, Rolf CM, Davis GJ, et al. Sudden and unexpected death in three cases of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. J Forensic Sciences. 2010;55(6):1641–1645. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2010.01521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Callewaert B, Malfait F, Loeys B, et al. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and Marfan syndrome. Best Practice and Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 2008;22:165–189. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]