Abstract

Background

Guidelines recommend, and Medicare requires, shared decision-making between patients and clinicians before referring individuals at high risk of lung cancer for chest CT screening. However, little is known about the extent to which shared decision-making about lung cancer screening is achieved in real-world settings.

Objective

To characterize patient and clinician impressions of early experiences with communication and decision-making about lung cancer screening and perceived barriers to achieving shared decision-making.

Design

Qualitative study entailing semi-structured interviews and focus groups.

Participants

We enrolled 36 clinicians who refer patients for lung cancer screening and 49 patients who had undergone lung cancer screening in the prior year. Participants were recruited from lung cancer screening programs at four hospitals (three Veterans Health Administration, one urban safety net).

Approach

Using content analysis, we analyzed transcripts to characterize communication and decision-making about lung cancer screening. Our analysis focused on the recommended components of shared decision-making (information sharing, deliberation, and decision aid use) and barriers to achieving shared decision-making.

Key Results

Clinicians varied in the information shared with patients, and did not consistently incorporate decision aids. Clinicians believed they explained the rationale and gave some (often purposely limited) information about the trade-offs of lung cancer screening. By contrast, some patients reported receiving little information about screening or its trade-offs and did not realize the CT was intended as a screening test for lung cancer. Clinicians and patients alike did not perceive that significant deliberation typically occurred. Clinicians perceived insufficient time, competing priorities, difficulty accessing decision aids, limited patient comprehension, and anticipated patient emotions as barriers to realizing shared decision-making.

Conclusions

Due to multiple perceived barriers, patient-clinician conversations about lung cancer screening may fall short of guideline-recommended shared decision-making supported by a decision aid. Consequently, patients may be left uncertain about lung cancer screening’s rationale, trade-offs, and process.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-018-4350-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: shared decision-making, patient-clinician communication, lung cancer screening

INTRODUCTION

Because of the potential to reduce mortality,1 multiple organizations recommend low-dose CT screening (LCS) for individuals at high risk of lung cancer.2–6 But LCS can also cause harm. In the largest trial over 25% of participants had a pulmonary nodule detected, with potential harms from nodule evaluation, including radiation exposure, distress, and physical complications.1 In real-world practice, the potential for harm is greater, as nodule detection and invasive evaluation occur more frequently.7, 8

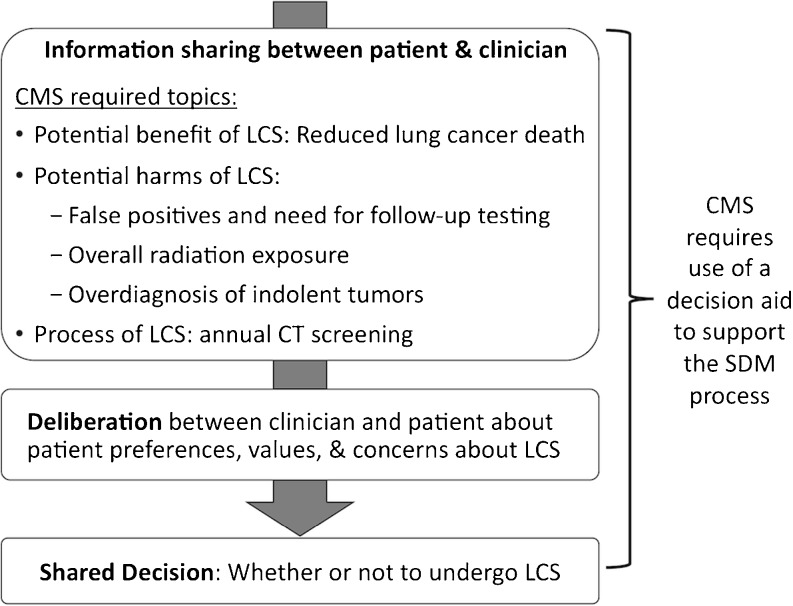

Recognizing possible harms and benefits of LCS, guidelines recommend shared decision-making (SDM) with patients before pursuing screening.2–6 Moreover, in unprecedented policy, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) require a documented SDM discussion with use of a decision aid (a tool to educate patients about clinical options and clarify their values and preferences9). CMS policy enumerates required discussion topics, including potential benefits (reduced lung cancer death), harms (false positives, follow-up testing, overall radiation exposure, overdiagnosis of indolent tumors), and process of LCS.10 As formulated by Charles and colleagues,11 SDM entails steps of information sharing and deliberation before making a decision (Fig. 1). During information sharing, clinicians provide information about the problem (increased cancer risk), options (performing LCS or not), and trade-offs (benefits and harms of LCS), while patients ask questions to ensure their understanding. During deliberation, patients and clinicians explore the patient’s values, preferences, and concerns to identify which option best matches those preferences.

Fig. 1.

Idealized depiction of SDM between patients and clinicians about LCS, including SDM steps recommended in Charles model and CMS-required elements.

Little is known about LCS discussions and decision-making in real-world settings,12–14 including the degree to which guideline and policy recommendations for SDM have been realized. This study aims to characterize experiences of patients and clinicians from diverse early adopting LCS programs regarding communication and decision-making.

METHODS

We recruited patients who were screened in the prior year (randomly selected from each site’s LCS registry) and clinicians who refer patients for LCS (primary care providers [PCPs], pulmonologists, screening nurse coordinators; Table 1). Among those invited, 36/50 clinicians and 49/221 patients participated. The Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Affairs (VA) Hospital and Boston University Medical Campus institutional review boards approved this research.

Table 1.

Characteristics of LCS Programs and Participants

| Program | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | |

| LCS Program characteristics | ||||

| Hospital type | Large VA hospital | Large VA hospital | Medium VA hospital | Urban safety net hospital |

| Geographic region | Northeast | Northeast | South | Northeast |

| LCS program initiated | February 2012 | June 2013 | February 2014 | March 2015 |

| Volume of patients screened at time of patient recruitment | 212 | 1890 | 110 | 362 |

| LCS guidelines governing program at time of interviews | NCCN | USPSTF | USPTF | USPSTF, CMS |

| SDM performed by… | Referring clinician or LCS nurse coordinator | Referring clinician | Referring clinician or LCS nurse coordinator | Referring clinician or LCS nurse coordinator |

| Participant characteristics | ||||

| Clinician participants (n) | ||||

| Primary care providers | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 |

| Pulmonologist (s) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| LCS nurse coordinator(s) | 1 | 3 | 1 | – |

| Patient participants (n) | 13 | 11 | 13 | 12 |

| Male/female | 11/2 | 11/0 | 13/0 | 5/7 |

CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, NCCN National Comprehensive Cancer Network, USPSTF United States Preventive Services Task Force

Informed by the Charles model and recommendations for SDM in LCS, we developed interview guides to probe impressions of patient-clinician communication and decision-making surrounding LCS, as well as usual practices and barriers to realizing guideline recommendations; Online Appendix. Between October 2013 and March 2015, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 15 clinicians and 37 patients from three VA facilities. To increase diversity and capture practices in a program governed by CMS policy, we collected a second wave of qualitative data at an urban safety net hospital between February and June 2016, including 21 clinician interviews and two patient focus groups (n = 12). All sessions were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed.

Our analysis explored the degree to which participants’ depictions of LCS discussions reflected SDM, which had been widely recommended by study onset. Selected team members performed close readings of transcripts and coded segments representing important concepts, with all transcripts coded by at least two investigators (RSW, EK). Using a directed content analysis approach,15 we developed codes to capture attributes of decision-making, working both deductively (specifically looking for recommended SDM elements) and inductively (open to discerning additional attributes that were implicit in participants’ accounts). We compared similarities and differences in clinician versus patient accounts, and accounts across sites. Through constant comparison and discussion of findings by the team, coding was iteratively revised until we reached consensus on the codes and summary categories of patients’ and providers’ perceptions. Similar content was elicited from patient focus groups and interviews.

RESULTS

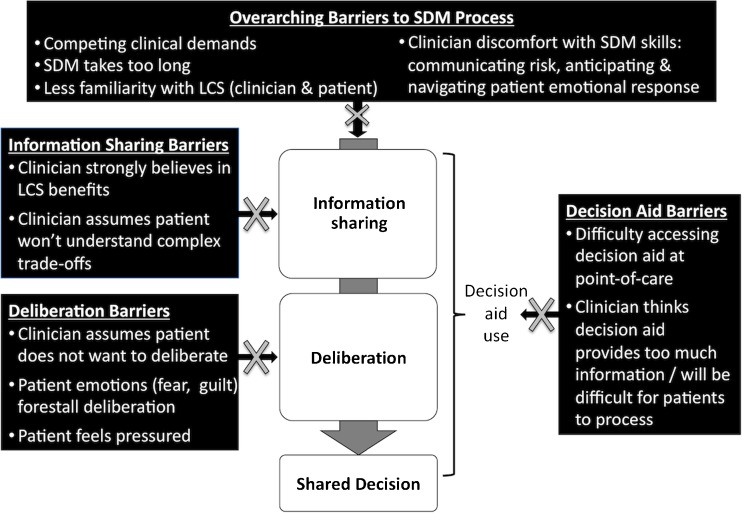

Our results are structured to illustrate how our findings map onto the recommended SDM elements (Fig. 1), with contrasting perspective of clinicians and patients in each section: (1) information sharing, (2) deliberation and decision-making, and (3) decision aids. The fourth section presents our findings on clinician-perceived barriers to shared decision-making, including overarching barriers as well as barriers associated with each recommended SDM element (Fig. 2). Except where noted, there were no obvious differences in participant accounts across sites.

Fig. 2.

Barriers to achieving guideline recommendations for SDM about LCS.

Information Sharing

Clinicians

Clinicians reported variable degrees of information sharing with patients (Table 2). Some offered a comprehensive description of LCS and provided a decision aid. These clinicians felt confident their patients understood the information, “They understand totally”. At the other extreme, some clinicians offered minimal information about LCS, its rationale, trade-offs, or process. Others focused primarily on benefits, with little acknowledgment of potential harms: “I’m supposed to talk about the radiation exposure and the anxiety that’s provoked by having some kind of lesion…but I don’t necessarily go into all the details.” Clinicians tended to emphasize harms related to nodule detection, rather than more abstract harms of radiation exposure or overdiagnosis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Spectrum of Information Clinicians Provide to Patients About LCS

| CMS informational element depicted in quote* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinician quote | Benefit: early detection/reduces lung cancer death | Harm: false positives/nodules | Harm: distress from nodule | Harm: overall radiation exposure | Process of LCS | Offers decision aid |

| “I tell people…it’s similar to the screening that one might do for breast cancer with mammography, women get regular mammography to detect early cancer, now we offer it to our veterans who have had history of smoking.”—Pulmonologist, site A | ✓ | |||||

| “I usually say, ‘The recommendation is to screen for lung cancer. …If we find something, then there’s a team of doctors who will help you to figure out if this is something serious or not. The reason we’re doing this is so that we can detect [cancer] early so that we can treat early, prevent it from advancing to more serious illness.”—PCP, site D | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| “I say, ‘We have the screening tools that have been proven to be effective to find asymptomatic disease early…to screen for lung cancer. You’re at high risk. I would order this special CAT scan that doesn’t quite have as much radiation as the old traditional CT’s…There’s a good chance we’ll find something, we may need more tests, or we may find nothing and still we’d recommend screening annually for a period of time.”—PCP, site A | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| “I tell them that they have certain health factors that place them at high risk for…lung cancer. …The benefits of screening are…you can detect lung cancer within stage 1 or 2 where the treatments options are cure, versus stage 3 or 4 when the patient becomes symptomatic and the treatment options are usually for life extension only…Then I go over the nodules, about how frequent they are, I tell them, ‘Don’t freak out. If we do find something we’re going to watch it really closely. We have time frames depending on your nodule, the size, the shape, the density.’…Then I give them my example about breast mammograms and how it can cause anxiety and I’m like, ‘I’m here to talk to you. We have counselors, we have mental health people if you start feeling depressed or anxious, call me.’ And I give them my direct line so they feel like there’s a safety net.”—Screening nurse coordinator, site C | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| “I say, ‘Lung cancer screening has been shown to decrease the risk of dying from lung cancer.…Before you agree I want you to know that 96% of abnormal CAT scans that show a little shadow are not going to be cancer. Could be from old infections you’ve had or other causes. So there’s a 96% chance if you have a shadow that we’re going to get another CAT scan down the road in either 3 or 6 months or a year to see if it changes..…Are you psychologically of mind where you can deal, you know, not freak out by knowing that you have a shadow that may or may not be bad for 3 or 6 months? Not all patients can handle that. These are low-dose CAT scans which are lower [radiation]…but still we don’t know exactly the long-term effects of getting yearly low-dose CAT scans for many years. So what do you think, Joe? I also can print out the VA information sheet if you’re interested in reading about this further.”—PCP, site B | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

*CMS also requires discussion of potential harm of overdiagnosis, but no clinician described reviewing this with patients

Those clinicians who reported limiting information provided different reasons for doing so. First, clinicians were uncertain of patients’ comprehension, particularly of potential LCS harms: “I think [for] patients in general, it’s hard to grasp the concept of false-positive catches on screening that can lead to interventions that can have negative consequences.” Some were worried that patients might be overwhelmed by the complexity of LCS trade-offs and thus highlighted only benefits: “I think for most [patients] the idea of…finding cancer so you don’t die of cancer is enough for them to take away.” Finally, some clinicians did not present much information about harms because of their own passionate belief in screening’s benefits: “We are screening a high-risk population. I personally feel the benefits outweigh the risk, so I don’t often go into that so much with the patients.”

Patients

Echoing clinician reports, patient accounts reflected a range of information received about LCS. Some reported receiving minimal information (“My PCP wasn’t really all that communicative”) and were not even told the indication for the CT. Faced with a vague explanation from their clinician (“We just want to check if you have any problems with your lungs”), some patients “figured it would be for cancer,” while others were left in the dark (“it didn’t even dawn on me that he could be looking for cancer”). Patients reported a preference for an explicit explanation (“A cancer screening! Well I wish I knew that’s what it was for”), noting it to be “a shock” to find out the indication from another source. Some patients received information about benefits, but knew little about harms: “what’s the downside? There is none.” This was frustrating for patients who subsequently experienced an unexpected outcome, such as finding a screen-detected nodule that required evaluation: “the thing that upset me is that I wasn’t told.”

By contrast, other patients reported successful information sharing with their clinicians, and were aware of the rationale (“My PCP asked if I wanted a low-dose radiation CT for lung cancer screening because I was a heavy smoker”), some trade-offs, and the process of LCS (Table 3). Some patients at one site who received counseling from the screening nurse coordinator reported a more thorough discussion of LCS trade-offs, compared with reports of patients counseled by other clinicians.

Table 3.

Patient Perspectives on Information Clinicians Provided About LCS

| CMS informational element depicted in quote* | Patient quote describing LCS trade-offs explained by clinicians |

|---|---|

| Benefit: early detection/reduces lung cancer death | “They were looking for the possibility of lung cancer [because]…the sooner they find it, the better the chances are to cure it”—Veteran, site C |

| Harm: false positives/nodules | “Deadly black spots. ….She actually had warned me when she made the appointment that they may see the beginnings of things.”—Safety net hospital patient, site D |

| Harm: distress from nodule | “She told me…some people have said that…if they found out they had something wrong with them, it bothered them afterwards.”—Veteran, site C |

| Process of LCS | “They said, ‘We’ll run a CT scan on you, and if we see anything there, we’ll do something about it, and if not, a year from now we’ll run another one’”—Veteran, site A |

*CMS also requires discussion of potential harms of overall radiation exposure and overdiagnosis of indolent tumors, but no patient discussed receiving this information

Deliberation and Decision-making

Clinicians

Clinicians discussed the challenges of engaging patients in deliberation. Some clinicians tried to elicit patients’ values regarding LCS trade-offs by describing experiences of other patients who had a screen-detected nodule:

“I tell [patients], ‘That doesn’t mean that you have cancer just because [screening] found some spot …Some patients, they’ve gone through the scans [or] biopsy and it turns out its normal. Some people [are] okay with that. They just want to be sure. …Other people are like, I don’t want to have to go through all that worry and that procedure just to find out that it wasn’t really cancer.’”

However, clinicians acknowledged that probing patients’ anticipated emotional reactions to potential surveillance of a screen-detected nodule—before even knowing whether a nodule would be found—could be difficult: “you have to make sure that a patient can psychologically deal with being told they have a shadow that may or not be cancer, [but] we’re not going to do anything about it except for repeat CAT scan…That takes some finesse.” Some clinicians perceived that patients’ fear of cancer forestalled attempts at deliberation: “some people are so freaked out about the potential for lung cancer, that no matter what, they completely discount the risks. They just want the scan.” Finally, some clinicians reported that despite their efforts, patients were not always receptive to engaging in deliberation, preferring either to defer the decision to their clinician or to decide for themselves without clinician input: “There are those that [answer] ‘whatever you say, Doc.’ …And there are those, ‘I don’t have any symptoms, I don’t want this, I don’t care what you tell me.’”

Patients

Patients also noted barriers to deliberation. Mirroring clinician accounts, some patients reported simply accepting their clinician’s strong recommendation without significant deliberation: “I only know it was recommended and I had it done.” One patient reported that although his doctor engaged him in a discussion, he ultimately felt pressured into accepting LCS despite his misgivings: “My doctor recommended it…and I kind of hesitated. …[After] a long conversation she says, ‘Just remember I’m the doctor, I know better,’ and I said, ‘Okay Doc.’”

For some patients LCS discussions provoked an emotional response that hindered engaging in deliberation, raising fear and guilt they were uncomfortable expressing to their clinicians:

“My secret thought was…‘Smoking is catching up. ...Jesus, what you did, you should’ve been dead 20 years ago.’”

“I don’t know how I would handle telling me that I [might have] cancer”

“I don’t let a lot of my emotions show, I…keep it hidden.”

Some patients reflected clinicians’ observation: they were so eager to rule out cancer that they would never consider declining LCS and did not want to deliberate: “I thought it was a very good idea to get tested…But it seemed like the fear of God was put into you, like that something could happen to you by taking this test. I’m thinking, ‘what could possibly happen other than finding out something that you should know anyway?’”

By contrast, some patients recalled successful deliberation, reporting that their questions and concerns were addressed and that they felt supported in making the right decision for themselves: “She had me a little worried when she first brought it up and then she explained it good. …It was presented to me very clearly that I certainly did not have to do this.”

Decision Aids

Clinicians

Clinicians reported mixed experiences with decision aids. Some found that they facilitated discussion and improved patient comprehension, especially if trade-offs were presented visually: “The decision aids that I think people like are the ones [with] a thousand people and they color in [patient outcomes].” Others believed decision aids with specific risk information served as a barrier to engaging patients: “We don’t get very quantitative because…their eyes glaze over, and I’m not sure it has much meaning to them.” By contrast, some believed personalized risk information was useful to patients: “I have plugged in patients that have a 10% risk of lung cancer. …I feel like it would potentially change the patient’s decision.” Some non-VA clinicians admitted they only used decision aids because of CMS policy: “if I wasn’t required to, I probably would not be using any…tool.” Finally, some clinicians noted they have not incorporated decision aids, in part because of difficulty accessing them at the point of care: “There are these wonderful tools online, but when I’m sitting in front of a patient, I can never find them.”

Patients

Most patients did not mention decision aids when recounting communication and decision-making about LCS. Those who did reported mixed impressions. Some were positive (“I loved it, it was very helpful”) and found decision aids useful to understand potential harms: “She took me through a four-pager...[It] said it might show up spots in the lungs and what that might mean or not mean.” Other patients found them excessively detailed and the information on harms off-putting: “They sent you all this list of possibilities of what could happen, you’re thinking, ‘Holy Christ!’”

Clinician-Perceived Barriers to SDM

Most clinicians expressed awareness of guideline recommendations for SDM: “the whole concept is supposed to be shared decision-making.” But all clinicians, including those who embraced SDM, described challenges in achieving SDM. Systemic barriers like competing demands during brief clinic visits existed at all sites:

“The problem with most preventive screening is that it never gets addressed because there’s always something else that’s taking priority.”

Barriers specific to the LCS context were also raised. Lack of familiarity with LCS, which applied to clinicians and patients, made SDM more challenging:

“It’s new for me, I haven’t quite developed my shtick around it. …It will take more time initially [to discuss the] pluses and minuses.”

“Mammograms people know about. You order it. Done. With the lung cancer screen it feels like there’s a whole other discussion.”

Some noted that helping patients understand LCS trade-offs and gauging their values regarding its harms and potential emotional impact required skill, which not all clinicians had mastered: “[Abnormal results] could be very anxiety-provoking and if they don’t quite understand the risks of being screened and that they could have a nodule that’s discovered, I do have concerns about that. I think it’s on us as physicians to explain that risk. I don’t think we’re very good at [it].”

Overarching barriers to SDM and barriers associated with each recommended SDM element (described in preceding sections) are depicted in Fig. 2.

DISCUSSION

LCS is unique in the uniform emphasis placed by clinical guidelines and CMS policy on SDM 2–6 and 10. Despite these recommendations, in this qualitative study involving 85 clinicians and patients from four diverse sites, we found that SDM for LCS is not uniformly realized in real-world practice. Although there were examples reported by both patients and clinicians of discussions containing the core elements of SDM, participant accounts suggested that LCS conversations may fall short of true SDM.

Clinicians from all sites reported challenges in achieving SDM, which may reflect a learning curve as hospitals struggle to implement this new and complex preventive health intervention.16, 17 Barriers to SDM in other contexts have been well-described and many are similar for LCS: clinicians reported limited time for SDM in the face of competing priorities, lacked risk communication skills, and perceived that patients do not always want to engage in SDM.12, 16, 18 The CMS policy to reimburse a separate SDM visit may help mitigate the barrier of limited time and competing priorities during clinical visits,10, 16 but such reimbursement incentives do not always succeed. For example, a similar CMS reimbursement code intended to increase rates of advance care planning has not been widely utilized.19

One of the most challenging barriers to achieving SDM may be the impression that some clinicians hold that patients cannot understand or do not want to discuss complex LCS trade-offs, especially potential harms.14, 18 Some studies suggest that individuals with lower education levels have misconceptions about LCS even after reviewing decision aids20 and engaging in SDM,13 highlighting the need for improved interventions to promote patient understanding. On the other hand, in our sample of patients served by VA and safety net hospitals (both socioeconomically disadvantaged populations in which many patients have limited health literacy21, 22), participants expressed a desire to know more about the rationale, process, and outcomes of LCS, and some were frustrated when clinicians had not communicated this information. The finding that clinicians did not uniformly engage patients in deliberation about their values and preferences is unfortunately consistent with other clinical decisions and represents a missed opportunity, as patients who report engaging in deliberation express greater satisfaction.23 Our study identified different ways in which patients’ emotions could forestall deliberation: fear of cancer could blind patients to consider possible LCS harms; and at times both patients and clinicians were reluctant to engage in discussions that might unleash an emotional response. Fear, guilt, and stigma are known barriers to patient participation in LCS,24–26 and the need for interventions to help modulate cancer fear to allow informed decision-making has been identified in other screening contexts.27

Fortunately, there are systems-level interventions that LCS programs can implement to promote SDM.28 In our study, some patients at one site who discussed LCS with a screening nurse coordinator recalled a full discussion of trade-offs. Not all PCPs are sufficiently familiar with LCS nuances yet to thoroughly counsel patients.14, 29, 30 LCS coordinators typically have more time to spend with patients and greater familiarity with the process and trade-offs of LCS, as well as available decision aids, than clinicians who have other competing clinical concerns to address.17 Empowering coordinators to conduct SDM has helped foster SDM in other LCS programs and is supported by CMS reimbursement policies if the coordinator is a mid-level provider or clinical nurse specialist.13, 31–33

Regardless of which clinician conducts SDM and that individual’s risk communication skills, making decision aids available at the point of care may help foster clear communication about LCS. Decision aids are designed to facilitate both the information sharing and deliberation steps of SDM and may help bridge the apparent disconnect between clinicians and patients.9 Clinicians in this study found pictographs useful for explaining LCS outcomes, but had mixed impressions of how much quantitative information patients could digest. Other studies have shown that LCS decision aids can increase patient knowledge, reduce decisional conflict, and improve concordance with patient’s values and preferences.20, 34, 35 Patients, including those with low literacy, value receiving clear LCS information from a decision aid, particularly when reviewed with a clinician.12, 20, 34, 36, 37 In particular, preparing patients for the possibility of a screen-detected nodule and the work-up that might ensue through clear, patient-centered communication may help mitigate future distress patients may experience if a nodule is found.38 In real-world settings, higher quality communication about incidental pulmonary nodules is associated with lower distress and improved adherence to evaluation.39, 40 Ongoing work in VA seeks to embed a web-based, personalized LCS decision tool that can be tailored to meet patient and clinician needs at the point of care.41

This study has limitations. We relied on participant recall of conversations, which may differ from what actually transpired. For example, clinicians may have overrepresented their use of SDM due to social desirability bias. Our inclusion of patients who had undergone LCS (versus those offered LCS) may have introduced bias. For example, Lillie and colleagues found that screened patients valued benefits over harms of LCS42; similarly, our patient participants may have been more likely to recall discussions of screening’s benefits than its harms. We purposely enrolled participants from diverse sites, but cannot conclude that our findings are generalizable to other settings. Interviews were conducted in the first few years after LCS was adopted into these settings. Communication and decision-making will likely continue to evolve as clinicians become more familiar with the evidence, guidelines, and policies surrounding LCS, and public awareness of LCS rises.

The recommendations for SDM about LCS are ethically sound: LCS trade-offs are real and informed individuals may decide differently about whether screening is right for them. For example, in the VA demonstration project the rates at which patients accepted LCS varied dramatically by site (34–66%).7 One explanation for these differences may lie in how clinicians discussed LCS and its trade-offs, and the degree to which true SDM occurred. Further work is needed to learn how to effectively overcome barriers to implementing this important recommendation.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 17 kb)

Acknowledgements

Prior Presentations

A preliminary version of portions of these results was presented at the American Thoracic Society conference, May 20, 2015.

Contributors

We thank Linda Kinsinger, MD, MPH, former Chief Consultant for Preventive Medicine, VHA National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention; Michael Kelley, MD, Director of the VA National Program Office for Oncology; and Marta Render, MD, former Director of the VA National Program Office for Pulmonary, Sleep, & Critical Care Medicine, for their role as operational partners during this work. We thank Nichole Tanner, MD, MSc, Hilary Cain, MD, Sue Yoon, ARNP, and Karin Sloan, MD for supplying a list of candidates to invite to participate in qualitative interviews and/or focus groups.

Funders

This study was funded by VA QUERI RRP 12-533, NIH 1UL1TR001430, and with resources from the Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial VA Hospital, the Portland VAMC, and the Puget Sound VAMC. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States government.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Au reports receiving payment from Novartis, Inc. for service on a data monitoring committee for a clinical trial. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Detterbeck FC, Mazzone PJ, Naidich DP, Bach PB. Screening for lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5 Suppl):e78S–92S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaklitsch MT, Jacobson FL, Austin JH, Field JK, Jett JR, Keshavjee S, et al. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery guidelines for lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography scans for lung cancer survivors and other high-risk groups. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144(1):33–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moyer Virginia A. Screening for Lung Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014;160(5):330–338. doi: 10.7326/M13-2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wender R, Fontham ET, Barrera E, Jr, Colditz GA, Church TR, Ettinger DS, et al. American Cancer Society lung cancer screening guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(2):107–17. doi: 10.3322/caac.21172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood DE, Kazerooni E, Baum SL, Dransfield MT, Eapen GA, Ettinger DS, et al. Lung cancer screening, version 1.2015: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015; 13(1):23–34; quiz 34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Kinsinger LS, Anderson C, Kim J, Larson M, Chan SH, King HA, et al. Implementation of Lung Cancer Screening in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Intern Med. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Okereke IC, Bates MF, Jankowich MD, Rounds SI, Kimble BA, Baptiste JV, et al. Effects of Implementation of Lung Cancer Screening at One Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Chest. 2016;150(5):1023–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stacey D, Legare F, Lewis K, Barry MJ, Bennett CL, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Decision Memo for Screening for Lung Cancer with Low Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT) (CAG-00439N. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=274. Accessed December 14 2017.

- 11.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango) Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(5):681–92. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanodra NM, Pope C, Halbert CH, Silvestri GA, Rice LJ, Tanner NT. Primary Care Provider and Patient Perspectives on Lung Cancer Screening: A Qualitative Study. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2016;13(11):1977–1982. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201604-286OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazzone PJ, Tenenbaum A, Seeley M, Petersen H, Lyon C, Han X, et al. Impact of a Lung Cancer Screening Counseling and Shared Decision-Making Visit. Chest. 2017;151(3):572–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffman RM, Sussman AL, Getrich CM, Rhyne RL, Crowell RE, Taylor KL, et al. Attitudes and Beliefs of Primary Care Providers in New Mexico About Lung Cancer Screening Using Low-Dose Computed Tomography. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E108. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.150112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Implementation of lung cancer screening: Proceedings of a workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gesthalter YB, Koppelman E, Bolton R, Slatore CG, Yoon SH, Cain HC, et al. Evaluations of Implementation at Early-adopting Lung Cancer Screening Programs: Lessons Learned. Chest. 2017; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Legare F, Witteman HO. Shared decision making: examining key elements and barriers to adoption into routine clinical practice. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(2):276–84. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.PerryUndem Research/Communication for The John A. Hartford Foundation, Cambia Health Foundation, and California Health Care Foundation. Physicians’ Views Toward Advance Care Planning and End-of-life Care Conversations: Findings from a National Survey among Physicians Who Regularly Treat Patients 65 and Older. April 2016. http://www.johnahartford.org/images/uploads/resources/ConversationStopper_Poll_Memo.pdf. Accessed December 14 2017.

- 20.Crothers K, Kross E, Reisch LM, Shahrir S, Slatore CG, Zeliadt SB, et al. Patients’ Attitudes Regarding Lung Cancer Screening and Decision Aids: A Survey and Focus Group Study. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016;13(11):1992–2001. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201604-289OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Rudd RR. The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):175–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, Noorbaloochi S, Grill JP, Snyder A, et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):561–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Couper MP, Singer E, Ubel PA, Ziniel S, Fowler FJ, Jr, et al. Deficits and variations in patients’ experience with making 9 common medical decisions: the DECISIONS survey. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(5 Suppl):85S–95S. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10380466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quaife SL, Marlow LAV, McEwen A, Janes SM, Wardle J. Attitudes towards lung cancer screening in socioeconomically deprived and heavy smoking communities: informing screening communication. Health Expect. 2017;20(4):563–73. doi: 10.1111/hex.12481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carter-Harris L, Brandzel S, Wernli KJ, Roth JA, Buist DSM. A qualitative study exploring why individuals opt out of lung cancer screening. Fam Pract. 2017;34(2):239–44. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmw146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter-Harris L, Ceppa DP, Hanna N, Rawl SM. Lung cancer screening: what do long-term smokers know and believe? Health Expect. 2017;20(1):59–68. doi: 10.1111/hex.12433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young B, Bedford L, Kendrick D, Vedhara K, Robertson, JFR, das Nair R. Factors influencing the decision to attend screening for cancer in the UK: a meta-ethnography of qualitative research. J Public Health (Oxf). 2017; 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Wiener RS, Gould MK, Arenberg DA, Au DH, Fennig K, Lamb CR, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/American College of Chest Physicians policy statement: implementation of low-dose computed tomography lung cancer screening programs in clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(7):881–91. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201508-1671ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis JA, Petty WJ, Tooze JA, Miller DP, Chiles C, Miller AA, et al. Low-Dose CT Lung Cancer Screening Practices and Attitudes among Primary Care Providers at an Academic Medical Center. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(4):664–70. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajupet S, Doshi D, Wisnivesky JP, Lin JJ. Attitudes About Lung Cancer Screening: Primary Care Providers Versus Specialists. Clin Lung Cancer. 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Hunnibell LS, Slatore CG, Ballard EA. Foundations for lung nodule management for nurse navigators. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17(5):525–31. doi: 10.1188/13.CJON.525-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reid AE, Tanoue L, Detterbeck F, Michaud GC, McCorkle R. The Role of the Advanced Practitioner in a Comprehensive Lung Cancer Screening and Pulmonary Nodule Program. J. Adv. Pract. Oncol. 2014;5:440–446. doi: 10.6004/jadpro.2014.5.6.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kinsinger LS, Atkins D, Provenzale D, Anderson C, Petzel R. Implementation of a new screening recommendation in health care: the Veterans Health Administration’s approach to lung cancer screening. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(8):597–8. doi: 10.7326/M14-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Volk RJ, Linder SK, Leal VB, Rabius V, Cinciripini PM, Kamath GR, et al. Feasibility of a patient decision aid about lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography. Prev Med. 2014;62:60–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lau YK, Caverly TJ, Cao P, Cherng ST, West M, Gaber C, et al. Evaluation of a Personalized, Web-Based Decision Aid for Lung Cancer Screening. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(6):e125–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schapira MM, Aggarwal C, Akers S, Aysola J, Imbert D, Langer C, et al. How Patients View Lung Cancer Screening: The Role of Uncertainty in Medical Decision Making. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016;13(11):1969–1976. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201604-290OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mishra SI, Sussman AL, Murrietta AM, Getrich CM, Rhyne R, Crowell RE, et al. Patient Perspectives on Low-Dose Computed Tomography for Lung Cancer Screening, New Mexico, 2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E108. doi: 10.5888/pcd13.160093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van den Bergh KA, Essink-Bot ML, Borsboom GJ, Th Scholten E, Prokop M, de Koning HJ, et al. Short-term health-related quality of life consequences in a lung cancer CT screening trial (NELSON) Br J Cancer. 2010;102(1):27–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moseson EM, Wiener RS, Golden SE, Au DH, Gorman JD, Laing AD, et al. Patient and Clinician Characteristics Associated with Adherence. A Cohort Study of Veterans with Incidental Pulmonary Nodules. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(5):651–9. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201511-745OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slatore CG, Wiener RS, Golden SE, Au DH, Ganzini L. Longitudinal Assessment of Distress among Veterans with Incidental Pulmonary Nodules. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(11):1983–91. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201607-555OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.QUERI–Quality Enhancement Research Initiative. PrOVE: PeRsonalizing Options through Veteran Engagement. http://www.queri.research.va.gov/programs/personalized_care.cfm. Accessed December 14, 2017.

- 42.Lillie SE, Fu SS, Fabbrini AE, Rice KL, Clothier B, Nelson DB, et al. What factors do patients consider most important in making lung cancer screening decisions? Findings from a demonstration project conducted in the Veterans Health Administration. Lung Cancer. 2017;104:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 17 kb)