Abstract

Background

Ethnic minority women are at increased risk of cervical cancer. Self-sampling for high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) is a promising approach to increase cervical screening among hard-to-reach populations.

Objective

To compare a community health worker (CHW)-led HPV self-sampling intervention with standard cervical cancer screening approaches.

Design

A 26-week single-blind randomized pragmatic clinical trial.

Participants

From October 6, 2011 to July 7, 2014, a total of 601 Black, Haitian, and Hispanic women aged 30–65 years in need of cervical cancer screening were recruited, 479 of whom completed study follow-up.

Interventions

Participants were randomized into three groups: (1) outreach by CHWs and provision of culturally tailored cervical cancer screening information (outreach), (2) individualized CHW-led education and navigation to local health care facilities for Pap smear (navigation), or (3) individualized CHW-led education with a choice of HPV self-sampling or CHW-facilitated navigation to Pap smear (self-swab option).

Main Measures

The proportion of women in each group whom self-reported completion of cervical cancer screening. Women lost to follow-up were considered as not having been screened.

Key Results

Of the 601 women enrolled, 355 (59%) were Hispanic, 210 (35%) were Haitian, and 36 (6%) were non-Haitian Black. In intent-to-treat analyses, 160 of 207 (77%) of women in the self-swab option group completed cervical cancer screening versus 57 of 182 (31%) in the outreach group (aOR 95% CI, p < 0.01) and 90 of 212 (43%) in the navigation group (aOR CI, p = 0.02).

Conclusions

As compared to more traditional approaches, CHW-facilitated HPV self-sampling led to increased cervical cancer screening among ethnic minority women in South Florida.

Trial Registration

Clinical Trials.gov Identifier: NCT02121548

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-018-4404-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

BACKGROUND

The widespread adoption of Pap smear screening has resulted in dramatic decreases in cervical cancer mortality.1 However, as compared with non-Hispanic white women, Black and Hispanic women in the United States (US) remain at increased risk.1, 2 These disparities are attributable to lower uptake of cervical cancer screening, which is recommended for women ages 21–65 once every 3 years. Multiple barriers to cervical cancer screening include lack of health insurance, limited access to care, low health literacy, immigration status, language barriers, and lack of awareness.3–5 Furthermore, as screening by Pap smear requires a pelvic examination, cultural beliefs as well as distrust of formalized health care systems may also contribute to such disparities.5, 6 In the US, interventions to address these disparities have primarily focused on culturally tailored approaches aimed at increasing Pap smear uptake. Many of these interventions include community health workers (CHWs).7, 8 CHWs are community members with limited formal health care training who understand local health beliefs, communicate in the language of the community, and understand the social and historical experiences shaping their communities. Yet, even with such programs, many women are not adequately screened.8, 9 Thus, additional strategies are warranted.

One alternative approach to cytology screening is testing for the presence of DNA from carcinogenic strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV), the primary cause of cervical cancers.10 This approach is now recommended as a primary screening strategy for women 25 and over by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), once every 5 years in maximal resource settings.11 In the US, in 2014, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved one high-risk HPV assay for such use.12 A strength of HPV screening is that when validated polymerase chain reaction tests are used, self-collected HPV specimens demonstrate similar sensitivity to physician-collected specimens.13, 14 HPV self-sampling is particularly promising because it is minimally invasive, involving only the self-collection of a swab without a speculum or vaginal exam.

In other countries, randomized studies of HPV self-sampling (most using mailed kits) have shown increased rates of screening.15, 16 In the US, several non-randomized studies17–19 and small pilot studies20 have also shown this approach has high acceptability among ethnic minority women. To determine if providing women with the option of HPV self-sampling would result in increased rates of cervical cancer screening among ethnic minority women, we conducted a randomized trial comparing this approach to more traditional outreach.

METHODS

Study Design

Detailed methods of the study protocol have been previously described.21 In brief, the study was a single-blind pragmatic RCT in which women were randomized to one of three interventions: (1) culturally tailored public health outreach (outreach), (2) community health worker (CHW) navigation to local health care facilities for Pap smear screening (navigation), and (3) CHW-facilitated HPV self-sampling (self-swab option). Our sample size of 600 women was based on a priori power analysis which indicated that this sample size would achieve adequate power (> .80) to detect a 15–20% difference in cervical cancer screening uptake between our study groups.19 The study was approved by the University of Miami Institutional Review Board and registered at clinialtrials.gov (NCT02121548).

Study Population

From October 6, 2011 to July 7, 2014, we recruited 601 women living in three ethnic neighborhoods in Miami-Dade County: Little Haiti (Haitian, n = 200), Hialeah (Hispanic, n = 200), and South Dade (multiple races/ethnicities, n = 201). We included women who (1) self-identified as Hispanic, Black, or Haitian, (2) age 30–65 years, and (3) did not have a Pap smear within the past 3 years. We excluded women who (1) had a previous hysterectomy, (2) reported a history of cervical cancer, (3) planned to move in the following 6 months, and/or (4) were currently enrolled in another cervical cancer prevention/outreach study.

CHWs employed by community health centers (CHCs) in each neighborhood recruited potential participants at community venues (e.g., stores, community events, churches). They explained the study and assessed study eligibility. Detailed contact information was obtained from eligible women expressing interest in participating. CHWs provided this information to research assistants (RAs), who contacted participants to schedule a study intake visit at the participant’s home, the participating CHC, or another mutually agreed upon community venue. During this visit, participants provided free and voluntary informed consent in their primary language (English, Spanish, or Haitian Creole) and had all of their questions answered prior to signing. Following consent, a brief structured interview including items regarding sociodemographic characteristics, health care access, utilization, and cervical cancer knowledge22 was conducted by the RA. The cervical cancer knowledge questions included true/false items regarding causes and symptoms of cervical cancer, as well as items regarding the effectiveness of cervical cancer screening. All interview items were developed with substantial input from community partners and piloted prior to study implementation. After the study intake, participants were randomized to one of three interventions using a pre-generated randomization list from the study statistician. Randomization was stratified by study site.

At 6 months, the RA, who was blinded to group assignment, contacted participants to conduct a follow-up interview including self-reported data on whether participants had completed cervical cancer screening since study entry. Participants were reminded not to reveal their group assignment during the follow-up assessment. Women received a $25 gift card at the intake and follow-up visits. For women who were unable to come for the follow-up interview, we attempted to collect cervical cancer screening information by phone. When participants completed their follow-up interview, their particpation in the study ended. Study-wide follow-up was completed on February 17, 2015.

Study Intervention Groups

Outreach Group

During the study intake visit, all participants were provided a culturally tailored brochure in their preferred language (English, Spanish, or Haitian Creole). The brochure explained the importance of cervical cancer screening and community-specific information on how to obtain a Pap smear at the CHC or other local facilities offering free or low-cost Pap smears. These brochures were developed with input from the CHWs, clinical staff at the CHC, and neighborhood-specific community advisory boards. CHWs also provided women with additional information on health and social programs, resources, and initiatives available at the CHC for which they may be eligible.

Navigation Group

Participants randomized to the CHW navigation group received the outreach intervention and also had a one-on-one education session with the CHW (lasting 30 min) at a mutually agreed upon location. The one-on-one education reinforced the educational materials. The CHW was also actively involved in helping participants obtain appointments for Pap smear screening at the CHC or any other health care facilities and following up to ensure the test had been done. This included providing participants with information on how to obtain an appointment at a health care facility, answering participant questions regarding what to expect during their visit, and following up with participants to inquire as to whether appointments were scheduled, as well as addressing any unforeseen challenges in scheduling the screening. In each community, free Pap smear screening was available for any woman age 50 years and over and free or low-cost screening was available at each CHC for women under age 50 (sliding scale based on income).

Self-Swab Option Group

Women randomized to this group also received the outreach intervention and the same individualized education session as those in the navigation group. They were then offered the option of performing the HPV self-sampling at the time of the education visit or having the CHW help navigate them to obtaining a Pap smear (same as navigation group). When the study was designed, empirical support for HPV self-sampling was more limited, and our institutional reviewers felt that women in the experimental group should be allowed to choose between standard screening (i.e., the Pap smear) and HPV self-sampling.

Study Outcomes

Our primary study outcome was self-reported completion of any form of cervical cancer screening (either Pap smear or HPV self-sampling) based on responses at the 6-month follow-up interview. Our analysis was based on intention to treat and we assumed that women whom we were not able to contact for follow-up information did not complete such screening. Women in the HPV self-swab option group were considered screened whether they chose to have the HPV self-swab or completed a Pap smear. We also conducted two other primary outcome analyses: the first included women for whom partial follow-up information (e.g., cervical cancer screening completion) was available via phone (n = 523) and the second included only women for whom the complete follow-up interview information was available (n = 479). As pre-planned secondary outcomes, we report changes in cervical cancer knowledge22 (proportion of women answering greater than 50% of knowledge questions correctly). Additionally, we evaluated changes in health insurance coverage and having a usual source of care.

Based on external feedback received after study completion, two post hoc analyses are presented. The first is a subgroup analysis restricted to women age 50 and over, as these women had access to free Pap smear screening through existing Centers for Disease Control (CDC)-funded programs. An additional concern was that for women undergoing HPV self-sampling, we had laboratory confirmation of the screening being completed. However, for women reporting having had Pap smear, we relied on self-reports. To obtain confirmatory evidence, the CHWs retrospectively reviewed the electronic medical records at two of the sponsoring CHC sites.

Statistical Analyses

We summarize patient characteristics using descriptive statistics for overall sample as well as by randomization arm. For categorical variables, differences in percentages were examined using chi-square tests. For continuous variables such as age, we used one-way ANOVA. We then examined women screened in each group by fitting multivariable logistic regression models with and without potential covariates including age, race/ethnicity, prior history of having had a Pap smear, marital status, education, insurance, and immigration status. These models also took into account clustering by study site. Logistic regression analyses were also performed using randomization arm interacted with study site as predictors for each outcome. Differences were considered statistically significant at alpha of 0.05. For regression analysis, we report odds ratio (OR) at the 95% confidence interval (CI). Data management and statistical analyses were done with SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

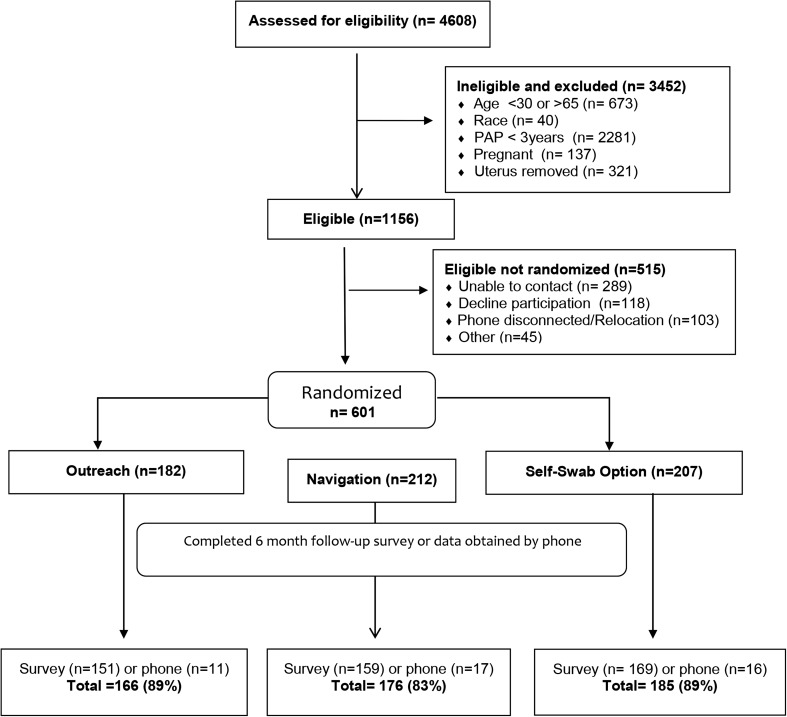

RESULTS

CHWs assessed 4608 women for potential study eligibility (Fig. 1). Of these, 75% were not eligible. Half of the ineligible women reported having had a Pap smear in the prior 3 years. Of the 1156 eligible women, we were unable to establish follow-up contact with 392 (34%) and 118 (10%) declined to participate. We obtained informed consent and randomized 601 women (outreach = 182, navigation = 212, and self-swab option = 207). Of those randomized to the navigation or self-swab option groups, 85 and 93% received the planned CHW educational session, respectively. Of those randomized to the self-swab option, 133 of 207 (64%) chose HPV self-sampling. At 6 months, we were able to conduct follow-up interviews with 479 (80%) women and were able to collect follow-up data by phone on an additional 44 (7%) women. By group assignment (including data collected by phone), follow-up data was available in 162 of 182 (89%) of women in outreach, 176 of 212 (83%) in the navigation group and 185 of 207 (89%) in the self-swab option group. By site, we were able to collect follow-up data on 181 of 200 (91%) of the women in Hialeah, 174 of 200 (87%) in Little Haiti, and 168 of 201 (83%) in South Dade.

Fig. 1.

Participant enrollment.

Among the 601 women, 355 (59%) were Hispanic, 210 (35%) were Haitian, and 36 (6%) were non-Haitian Black (Table 1). The mean age of study participants was 48.7 ± 9.1 years, 497 (83%) lacked health insurance, and 307 (51%) lacked a usual source of care. In addition, 202 (34%) reported being US citizens and 260 (43%) were permanent residents. Lastly, 101 (17%) reported never having had a Pap smear in their lifetime. The distribution of these characteristics was similar across all three groups.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Intervention Group

| Outreach N = 182 | Navigation N = 212 | Self-swab option N = 207 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age mean (SD) | 47.5 (9.0) | 48.3 (8.8) | 47.4 (9.5) |

| Income (% < $ 20,000/year) | 57.1 | 60.4 | 61.8 |

| Education (% < 12 years) | 37.9 | 42.9 | 37.7 |

| Uninsured (%) | 83.0 | 80.2 | 85.0 |

| With no usual source of care (%) | 50.5 | 51.9 | 50.7 |

| Marital status (% married) | 51.4 | 51.7 | 51.1 |

| Ever had PAP smear (% yes) | 79.1 | 84.9 | 85.0 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic (%) | 57.1 | 59.0 | 60.9 |

| Haitian (%) | 37.9 | 34.4 | 32.9 |

| Black (non-Haitian) (%) | 4.9 | 6.6 | 6.3 |

| Immigration status | |||

| US citizen (%) | 33.0 | 32.5 | 35.3 |

| Permanent resident (%) | 40.7 | 47.2 | 41.5 |

| Other (%) | 26.4 | 20.3 | 23.2 |

*There were no statistically significant differences in the distribution of these baseline characteristics across the three groups

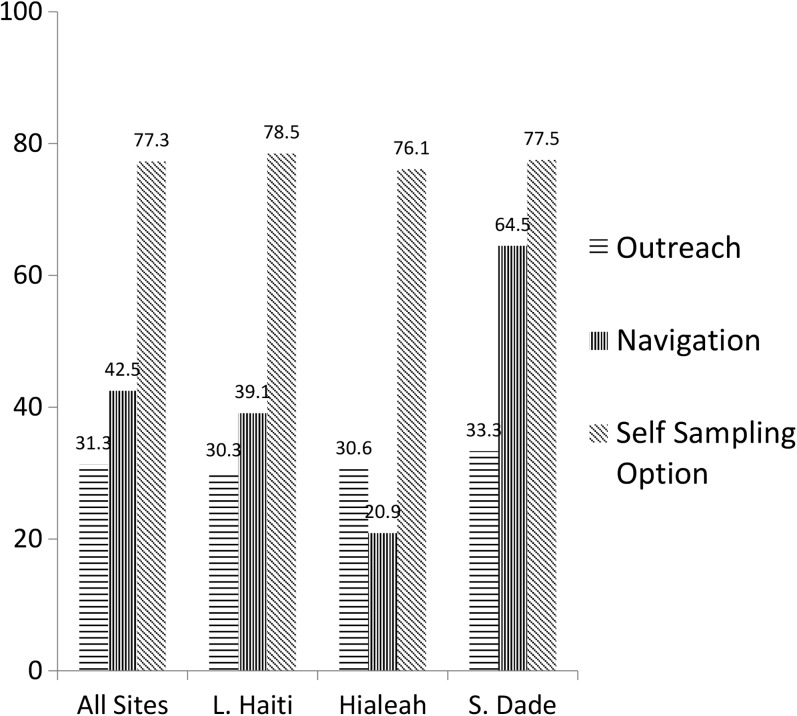

At 6 months, women in the self-swab option group were significantly more likely to report having had cervical cancer screening than women in the outreach group (77% (160 of 207) versus 31% (57 of 182), OR 7.47 CI 4.75–11.73, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2). Women in the navigation group were also significantly more likely to report having had a cervical cancer screening when compared with women in the outreach group (43% (90 of 212) versus 31% (57 of 182) OR 1.62, CI 1.07–2.45, p = 0.02; Table 2). The proportion of women screened in the self-swab option group was also significantly higher than the proportion screened in the navigation group (OR 4.61, CI 3.02–7.05, p < 0.01). Analysis restricted to the 523 women for whom partial follow-up information was available as well as to the 479 who completed the 6-month questionnaire yielded similar results (see Table 2). Multivariable models controlling for clustering by site, factors independently associated with having screening (income, marital and immigration status), other potential covariates (age, health insurance, education, ever having had a Pap smear, race/ethnicity), also found completion of any form of cervical cancer screening was higher among the self-swab option group than outreach (adjOR 7.69, CI 7.18–8.23) or navigation (adjOR 4.73, CI 1.92–11.68). For the comparison of the navigation versus outreach, the adjusted and un-adjusted odds ratio was similar, but after including the additional covariates, the relationship was no longer significant (navigation OR 1.63, CI 0.70–3.78; see online appendix table).

Fig. 2.

Percentage of women screened for cervical cancer: total and by community. *p < 0.01 for HPV versus outreach at all three sites, and for CHW versus outreach in South Dade.

Table 2.

Percentage of Women Reporting Having Cervical Cancer Screening (Pap Smear or HPV Self-Sampling)

| Outreach | Navigation | Self-swab option | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All women+ (N = 601) | 31.3 | 42.5* | 77.3** |

| Only women who completed 6-month follow-up survey (N = 479) | 35.2 | 51.1** | 86.5** |

| Women who completed 6-month survey or answered screening question by phone N = 523 | 35.8 | 51.6** | 89.3** |

*P < 0.05 for this group versus outreach

**P < 0.01 for this group versus outreach

†Assumes those missing follow-up data did not undergo cervical cancer screening

The post hoc analysis restricted to participants age 50 years and over found similar results; 75% (65 of 87) in the self-swab option group were screened, versus 46% (46 of 101) in the navigation group and 38% (27 of 72) in the outreach group. In addition, in the CHC medical record review for participants who self-reported having had a Pap smear, we were able to find documentation of it being done at the sponsoring CHC in 24 of 57 (43%) of women in the outreach group and 50 of 90 (56%) in the navigation group.

Among the 479 women who completed the follow-up survey, we found significant increases in the percentage of women who reported having health insurance and a usual source of care (Table 3). However, women in the self-swab option group had similar increases in proportion reporting health insurance and a usual source of care to both the navigation and the outreach group. In the overall sample, the proportion of women who correctly answered over half of the cervical cancer knowledge questions increased from 25% at the initial survey to 44% at the 6-month survey. By group assignment, this increase in cervical cancer knowledge was significantly greater in the self-swab option group versus that in the other two groups (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Secondary Outcomes at Baseline and Follow-up by Intervention Group

| All women | Outreach | Navigation | Self-swab option | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary outcomes (N = 479) | % (N = 479) | % (N = 151) | % (N = 159) | % (N = 169) |

| Cervical cancer knowledge (% > 50% questions correct) | ||||

| Baseline | 25.3 | 33.1 | 25.2 | 18.3 |

| Follow-up | 44.3* | 45.0 | 41.5 | 46.2** |

| Have health insurance | ||||

| Baseline | 17.5 | 16.6 | 21.4 | 14.8 |

| Follow-up | 26.5* | 27.8 | 26.4 | 25.4 |

| Have usual source of care | ||||

| Baseline | 50.3 | 49.7 | 51.6 | 49.7 |

| Follow-up | 66.4* | 66.2 | 66.0 | 66.9 |

*P < 0.01 for increase from baseline to exit across all three groups

**P < 0.01 for interaction of increase in knowledge from baseline to follow-up for HPV group

HPV Screening Results

In total, there were 265 women in the study who completed HPV self-sampling. This included the 133 of 207 (64%) of women in the self-swab group who chose to have the HPV self-sampling. In addition, at study conclusion, there were 174 women in the outreach and navigation groups who reported not being screened. After their exit interview, we offered these women the opportunity to have HPV self-sampling; of these, 132 (76%) agreed. Thus, overall, there were 265 women who completed HPV self-sampling. Of these 265 women, 49 (19%) were found to be positive for high-risk HPV. By comparison, the US national HPV positivity rate is approximately 25%.23 Of the 49 women who were HPV positive, we successfully navigated 42 of these 49 (86%) women to follow-up Pap smear and/or colposcopy. Lastly, among the 265 women who completed HPV self-sampling, only two required repeat testing due to inadequate sample collection. On repeat testing, both women provided an adequate sample.

DISCUSSION

Among medically underserved minority women living in South Florida, we found that a CHW-led approach that included the option of HPV self-sampling resulted in higher rates of cervical cancer screening than CHW navigation or outreach alone. As previously described, HPV self-testing is a promising primary screening strategy, with greater sensitivity than traditional cytology, and similar sensitivity to physician-collected specimens.13–16 Furthermore, HPV self-sampling has repeatedly demonstrated high acceptability to women.17, 19 Previous studies in Europe also found that cervical cancer screening with HPV self-sampling was superior to standard outreach.15, 16 However, those studies used mailed self-sampling kits and completion rates ranged from only 10 to 35%. In Latin America, when CHWs recruited participants using a door-to-door approach and offered the test immediately, the uptake rates were much higher. 24, 25

We also found that women in the self-swab option group had greater increases in cervical cancer knowledge than women in either the navigation or the outreach group. This finding is particularly interesting because women in the self-swab option group received the same education as women in the navigation group. We believe that perhaps providing women a more active role in the screening process with the self-sampling procedure enhanced the effectiveness of the educational portion of the intervention.

We found that nearly a third of women in the outreach alone group were screened, suggesting tailored public health outreach by itself can have an important impact. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution as we relied on self-reports which may have led to over-reporting.26 We did find confirmation of cervical cancer screening completion for about half the women reporting such screening. But, this finding also needs to be interpreted with caution as women were free to have screening at any site and the location where the screening was done was not recorded at the follow-up interview. It is important to note that if the Pap smear completion was over-reported in the outreach alone and navigation groups, the true magnitude of the differences in screening between these approaches and the self-swab option group is greater than that of what we have reported.

Limitations

One caveat is that for women who elected to self-sample, there was no charge for the test. We worked with our local community partners and CHCs to establish systems to allow women in the other two groups access to free or low-cost Pap smears. However, for women who were not income-eligible for free Pap smears, even nominal co-payments may be a differential barrier to screening. To address this concern, we conducted a post hoc analysis of our participants over 50 years of age, all whom were eligible for free Pap smears. Our results in this subgroup were similar to our general findings. Furthermore, while we were able to collect data regarding how many participants were successfully navigated to follow-up care upon receiving a positive HPV result following a self-swab, we were unable to query medical records to examine how many women had abnormal Pap smear results, and of those, how many received appropriate follow-up care. Future research should examine the proportion of women with abnormal results who receive appropriate follow-up care for each of these screening approaches (e.g., Pap smear vs. self-sampling).

Additionally, while the option of self-sampling may increase cervical cancer screening overall, women who self-sample may potentially miss opportunities for identification of other gynecological issues by a clinician completing a physical exam. We acknowledge this inherent limitation to self-sampling approaches; however, we also note that no other approach has been as efficacious in improving cervical cancer screening. Thus, HPV self-sampling is an important option for those who do not have access to, or are not willing to undergo, Pap smear screening.

Finally, while our results demonstrated HPV self-sampling to be an efficacious cervical cancer screening strategy, we acknowledge that this finding may not apply to all groups of underserved and ethnic minority women. Our sample size was small, and the majority of our sample included Hispanic and Haitian immigrant women who were recruited from public areas. Thus, future research should examine HPV self-sampling as a potential screening strategy with larger, more diverse samples, and harder-to-reach women.

Conclusion

The elimination of cervical cancer disparities in the United States will require a multi-pronged prevention approach, including widespread and equitable uptake of cervical cancer screening, coupled with HPV vaccination of all children.27 Our findings show that a CHW-led HPV self-sampling approach can result in a high proportion of ethnic minority women being screened for cervical cancer.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 24 kb)

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank our study team staff having a critical role in ensuring completion of the study. These include our community health workers, Valentine Cesar (center for Haitian Studies), Maria Azqueta (Citrus Health), and Linabell Lopez (Community Health Inc.); data management and analysis team including Carmen Linarte and Feng Miao; and prior project coordinator Brendaly Rodriguez.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute Community Networks Program Center Grant U54 CAI53705.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The study was approved by the University of Miami Institutional Review Board and registered at clinialtrials.gov (NCT02121548). During this visit, participants provided free and voluntary informed consent in their primary language (English, Spanish, or Haitian Creole) and had all of their questions answered prior to signing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Olveen Carrasquillo, Phone: 305-243-2718, Email: oc6@med.miami.edu.

Julia Seay, Email: jseay@med.miami.edu.

Anthony Amofah, Email: SAmofah@chisouthfl.org.

Larry Pierre, Email: mlpierre@aol.com.

Yisel Alonzo, Email: YAlonzo@med.miami.edu.

Shelia McCann, Email: mccannsy@bellsouth.net.

Martha Gonzalez, Email: mgonzalez16@med.miami.edu.

Dinah Trevil, Email: DTrevil@med.miami.edu.

Tulay Koru-Sengul, Email: TSengul@med.miami.edu.

Erin Kobetz, Email: EKobetz@med.miami.edu.

References

- 1.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2013 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2016. Available at: www.cdc.gov/uscs. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- 2.Beavis AL, Gravitt PE, Rositch AF. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates reveal a larger racial disparity in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123:1044–1050. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Musselwhite W, Oliveira CM, Kwaramba T, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in cervical cancer screening and outcomes. Acta Cytologica. 2016;60:518–526. doi: 10.1159/000452240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin L, Benard VB, Greek A, Hawkins NA, Roland KB, Saraiya M. Racial and ethnic differences in human papillomavirus positivity and risk factors among low-income women in Federally Qualified Health Centers in the United States. Prev Med. 2015;81:258–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seay JS, Carrasquillo O, Campos NG, McCann S, Amofah A, Pierre L, et al. Cancer screening utilization among immigrant women in Miami, Florida. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. 2015;9 Suppl:11–20. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2015.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Downs LS, Smith JS, Scarinci I, Flowers L, Parham G. The disparity of cervical cancer in diverse populations. Gynecologic Oncology. 2008;109:S22–S30. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Brien MJ, Halbert CH, Bixby R, Susana Pimentel S, Shea J. Community health worker intervention to decrease cervical cancer disparities in Hispanic women. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:1186–1192. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1434-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Cancer Institute. Research-tested Intervention Programs (RTIPs): cervical cancer Available from: https://rtips.cancer.gov/rtips/programSearch.do Accessed February 2, 2018

- 9.Community Preventive Services Task Force Updated recommendations for client- and provider-oriented interventions to increase breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:760–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, et al. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomized controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383:524–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeronimo J, Castle PE, Temin S, et al. Secondary prevention of cervical cancer: ASCO Resource-Stratified Clinical Practice Guideline. J Glob Oncol. 2017;3:635–657. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2016.006577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Food and Drug Administration. Meeting materials of the microbiology devices panel. 12 March 2014. FDA, Bethesda, MD. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170113191702/http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/MedicalDevices/MedicalDevicesAdvisoryCommittee/MicrobiologyDevicesPanel/UCM388564.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- 13.Arbyn M, Verdoodt F, Snijders PJ, Verhoef VM, Suonio E, Dillner L, et al. Accuracy of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples: a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:172–83. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70570-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belinson JL, Du H, Yang B, Wu R, Belinson SE, Qu X, et al. Improved sensitivity of vaginal self-collection and high-risk human papillomavirus testing. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:1855–60. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Racey CS, Withrow DR, Gesink D. Self-collected HPV testing improves participation in cervical cancer screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Public Health. 2013;104:e159–e166. doi: 10.1007/BF03405681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verdoodt F, Jentschke M, Hillemanns P, Racey CS, Snijders PJ, Arbyn M. Reaching women who do not participate in the regular cervical cancer screening program by offering self-sampling kits: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:2375–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barbee L, Kobetz E, Menard J, Cook N, Blanco J, Barton B, et al. Assessing the acceptability of self-sampling for HPV among Haitian immigrant women: CBPR in action. Cancer Causes & Control. 2010;21:421–31. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castle PE, Rausa A, Walls T, Gravitt PE, Partridge EE, Olivo V, et al. Comparative community outreach to increase cervical cancer screening in the Mississippi Delta. Prev Med. 2011;52:452–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ilangovan K, Erin Kobetz E, Koru-Sengul T, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of human papilloma virus self-sampling for cervical cancer screening. Journal Women’s Health. 2016;25:944–51. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sewali B, Okuyemi KS, Askhir A, et al. Cervical cancer screening with clinic-based Pap test versus home HPV test among Somali immigrant women in Minnesota: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Cancer Med. 2015;4:620–631. doi: 10.1002/cam4.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carrasquillo O, McCann S, Amofah A, et al. Rationale and Design of the Research Project of the South Florida Center for the Reduction of Cancer Health Disparities (SUCCESS): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:e299. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tiro JA, Meissner HI, Kobrin S, Chollette V. What do women in the U.S. know about human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer? Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, and Prevention. 2007;16:288–94. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hariri S, Unger ER, Strenberg M, et al. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus among females in the United States, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003–2006. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:566–573. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazcano-Ponce E, Lorincz A, Cruz-Valdez, et al. Self-collection of vaginal specimens for human papillomavirus testing in cervical cancer prevention (MARCH): a community-based randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1868–1873. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61522-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arrossi S, Thouyaret L, Herrero R, et al. Effect of self-collection of HPV DNA offered by community health workers at home visits on uptake of screening for cervical cancer (the EMA study): a population-based cluster-randomized trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e85–94. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70354-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montaño DE, Phillips WR. Cancer screening by primary care physicians: a comparison of rates obtained from physician self-report, patient survey, and chart audit. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:795–800. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.85.6.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han JJ, Beltran TH, Song JW. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus infection and human papillomavirus vaccination rates among US adult men National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2013-2014. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:810–816. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 24 kb)