Abstract

Aims: Cells have evolved a highly sophisticated web of cytoprotective systems to neutralize unwanted oxidative stress, but are challenged by unique modern day stresses such as cigarette smoking and ingestion of a high-fat diet (HFD). Age-related disease, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD), the most common cause of blindness among the elderly in Western societies, develops in part, when oxidative stress overwhelms cytoprotective systems to injure tissue. Since most studies focus on the protection by a single protective system, the aim of this study was to investigate the impact of more than one cytoprotective system against oxidative stress.

Results: Wingless (Wnt) and nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), two fundamental signaling systems that are vital to cell survival, decline after mice are exposed to chronic cigarette smoke and HFD, two established AMD risk factors, in a bidirectional feedback loop through phosphorylated glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta. Decreased Wnt and Nrf2 signaling leads to retinal pigment epithelial dysfunction and apoptosis, and a phenotype that is strikingly similar to geographic atrophy (GA), an advanced form of AMD with no effective treatment.

Innovation: This study is the first to show that chronic oxidative stress from common modern day environmental exposures reduces two fundamental and vital cytoprotective networks in a bidirectional feedback loop, and their decline leads to advanced disease phenotype.

Conclusion: Our data offer new insights into how combined modern oxidative stresses of cigarette smoking and HFD contribute to GA through an interactive decline in Wnt and Nrf2 signaling. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 29, 389–407.

Keywords: : aging, age-related macular degeneration, oxidative stress, Nrf2, smoking, high-fat diet, Wnt

Introduction

Age-related diseases significantly impact our society as the “baby boomers” age. While aging is a decline in the cumulative response to oxidative stress by its antioxidant defense network, age-related disease develops, in part, when these impaired cytoprotective pathways are severe enough to enable oxidative stress to permanently injure tissue. Since most studies have focused on a single antioxidant system, the function and interaction between cytoprotective systems during disease development are not known. Cigarette smoking and high-fat diet (HFD) have emerged as unique modern day oxidative exposome factors that stress an organism's cytoprotective responses. How these particular oxidative stresses influence cytoprotective pathways in age-related disease is poorly understood.

A prototypical, complex aging-related disease that is influenced by oxidative stress through cigarette smoke (CS) and HFD is age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (46, 61), the main cause for legal blindness in the industrialized world (8). By the mid-2000s, AMD developed into a major public health problem that has cost $30 billion annually in the United States (5), €597 million in Canada, €926 million in France, €1155 million in Germany, and €662 million in the United Kingdom (9). With the aging population, the number of people with advanced AMD in the United States alone will nearly double to 3 million people by 2020 (15). While treatment is available for the advanced wet form of AMD, no treatment exists for the advanced dry form of AMD called geographic atrophy (GA).

Innovation.

When evaluating protection against oxidative stress, most studies have focused on a single cytoprotective system. Since cytoprotective systems are likely an interactive web, we evaluated two essential systems and find that both the wingless (Wnt) and nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathways decline in a bidirectional feedback loop after chronic oxidative stress from cigarette smoke and high-fat diet. Importantly, this mechanism led to a phenotype strikingly reminiscent to geographic atrophy (GA), an advanced form of age-related macular degeneration without treatment, in mice. Future studies should consider assessing more than one cytoprotective system against oxidative stress. Our results provide potential treatment targets and a robust model for testing new therapy for GA.

A central feature of AMD is retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) degeneration. The RPE is a highly specialized cell that is sandwiched between the photoreceptors, which detect light, and the choriocapillaris, the highly vascular system that provides oxygen and essential nutrients to the photoreceptors. Because of its many specialized functions that maintain photoreceptor health, the RPE plays a pivotal role in maintaining normal vision and, in particular, central visual acuity from the macula.

Due to the high ambient oxygen tensions required for its high metabolism that is necessary to maintain the health and function of the overlying photoreceptors, and the unique, constant exposure to photo-oxidative stress, the RPE is armed with a robust antioxidant system (1, 57), making it a valuable model to study the oxidative stress response. Mild to moderate RPE cell dysfunction leads to photoreceptor impairment and visual loss in early AMD. As RPE dysfunction worsens, AMD severity progresses. When advanced, islands of RPE cell death develop, this defines GA (33). Since disease progression is related to the extent of the transition zone of damaged RPE surrounding the GA, understanding how the RPE degenerates will hasten therapeutic breakthroughs for GA.

We investigated the underlying molecular mechanism of how cytoprotective pathways guard the RPE against oxidative injury after exposure to CS and HFD, and the extent that a disease phenotype develops when these pathways become impaired. We chose to study wingless (Wnt) signaling because it is one of the first molecular responses to cellular stress, dysregulated Wnt signaling is implicated in age-related diseases (43, 69), and a single-nucleotide polymorphism in the Wnt receptor, lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (Lrp6) is associated with AMD risk (26), yet no studies have linked Wnt with AMD pathobiology.

In our study, we found that chronic CS and HFD treatment decreased Wnt signaling, which decreased the principal antioxidant network that revolves around the nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) transcription factor (TF) (27), and resulted in a phenotype strikingly similar to GA. Our data suggest that the combined modern oxidative stresses of CS and HFD contribute to a cooperative decline in Wnt and Nrf2 signaling and a severe age-related disease phenotype.

Results

Wnt5 is the predominant Wnt ligand expressed by the RPE/choroid in apoB100 mice

Our experimental plan was to chronically expose mice to a combination of HFD and CS to study the impact of chronic oxidative stress on cytoprotective pathways. Since mice predominantly express apolipoprotein (apo) B48 rather than apoB100, we selected “apoB100” mice, which have a mutation in the apoB48 editing codon that reduces the conversion of apoB100 to apoB48, to simulate in humans, lipid transport by apoB100 lipoproteins following an HFD (14). These mice produce physiological apoB100 lipoprotein levels in both the RPE and liver, which mimic humans (4, 16).

Wnt signaling is initiated after a Wnt ligand binds to the Frizzled-Lrp6 receptor complex. Since there are 19 known Wnt ligands, we used a Wnt PCR array to first identify the relative expression of relevant Wnt ligands that could activate Wnt signaling in the RPE/choroid of apoB100 mice relative to B6;129 wild-type (WT) mice, and secondarily, to determine the extent that Wnt ligands or other Wnt pathway genes have altered expression with aging. The mRNAs of all 17 Wnt ligands on the PCR array were detected and were not differentially expressed in the RPE/choroid of 2-month-old apoB100 and WT mice (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars).

Wnt5a, which can activate both canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling (47), was the most abundantly expressed Wnt ligand in the RPE/choroid of 2-month-old apoB100 mice, and was decreased in 11-month-old apoB100 mice compared with 11-month-old WT mice. By Western blot analysis, Wnt5 protein was decreased in the RPE/choroid of 2-month-old apoB100 mice compared with WT mice (p < 0.01; Supplementary Fig. S1), while the Wnt3 protein, with low expression on the array, was not detected using two different antibodies. In general, Wnt pathway gene expression in the RPE/choroid was similar between 2-month-old apoB100 and WT mice, although Lrp6 was among several Wnt genes with decreased expression in apoB100 mice (Supplementary Table S2). Likewise, Wnt pathway expression was unchanged in the RPE/choroid with aging in old apoB100 mice, except for a small group of genes, including Lrp6, that were decreased (Supplementary Table S2).

Wnt5 signaling is impaired in apoB100 mice exposed to chronic oxidative stress

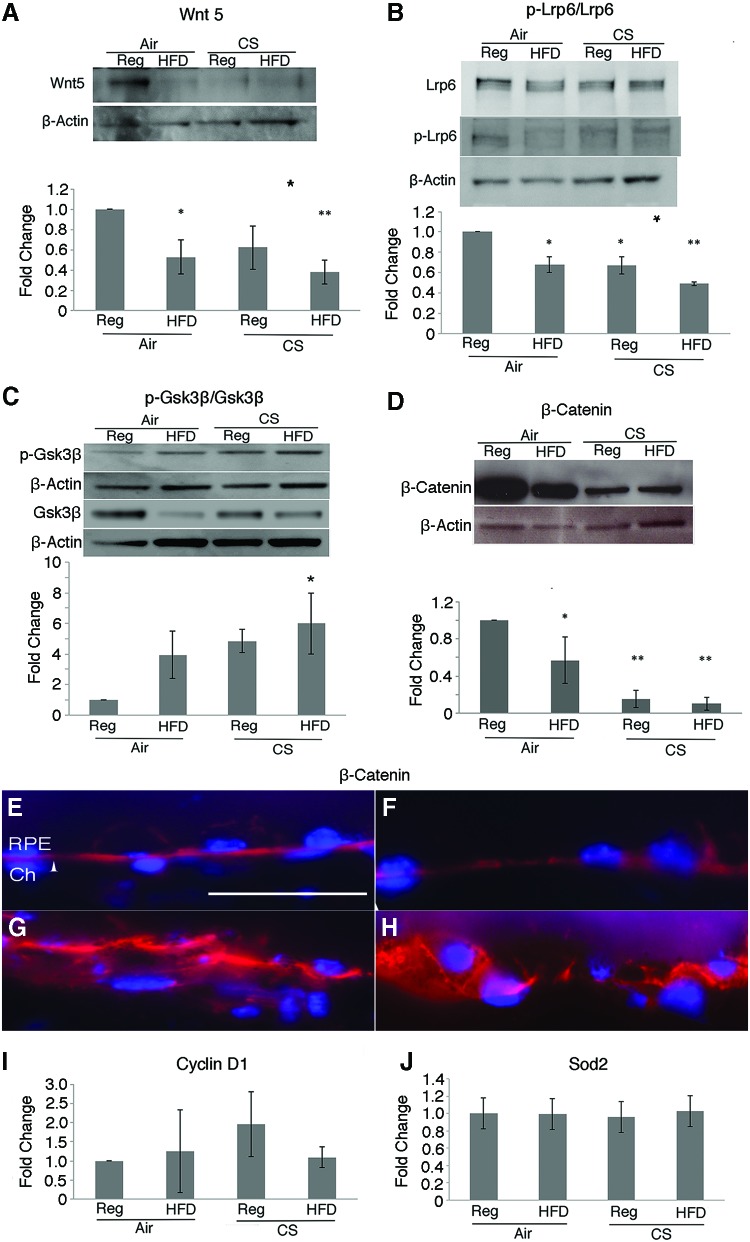

We next assessed the abundance of Wnt5 in the RPE/choroid of apoB100 mice given chronic oxidative stress. In apoB100 mice treated with CS + HFD for 6 months, Wnt5 protein in the RPE/choroid was decreased relative to apoB100 mice raised in air on a chow diet (p < 0.05; Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. S2). Lrp6 is phosphorylated after Wnt ligand binds to the Frizzled-Lrp receptor complex. The p-Lrp6/Lrp6 ratio was decreased in the RPE/choroid of apoB100 mice given CS + HFD, compared with mice treated with a normal diet and air (p < 0.05; Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. S3). p-glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (Gsk3β) (Tyr216) regulates the stability of β-catenin. The RPE/choroid of apoB100 mice given CS + HFD had increased p-Gsk3β/Gsk3β (p < 0.05; Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. S4) and decreased β-catenin, compared with mice treated with a normal diet and air (p < 0.01; Fig. 1D and Supplementary Fig. S5).

FIG. 1.

Wnt signaling is decreased in the RPE/choroid of apoB100 mice treated for 6 months with CS + HFD. Western blot and graph showing (A) decreased Wnt5, (B) decreased p-Lrp6/Lrp6, (C) increased p-Gsk3β/Gsk3β, and (D) decreased β-catenin. β-Actin was used as a loading control for (A–D). β-Catenin immunolabeling is distinct at the lateral and basal borders of the RPE from apoB100 mice raised in air and regular diet (E) or HFD (F), but became diffusely distributed and basally located in mice given CS and a regular diet (G) or HFD (H). Arrowhead points to Bruch's membrane; bar = 25 μm. mRNA expression of (I) CyclinD1 and (J) Sod2, two downstream Wnt targets, is not induced after CS + HFD. N = 4 mice per group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. apoB100, apolipoprotein B100; CS, cigarette smoke; GSK3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta; HFD, high-fat diet; Lrp6, lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6; Reg, regular diet; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; SOD2, superoxide dismutase 2; Wnt, wingless. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

The distribution of β-catenin in the RPE changed with chronic oxidative stress. β-Catenin immunolabeling was distinct at the lateral and basal borders of the RPE from apoB100 mice raised in air on either a regular or HFD, but became diffusely and basally distributed in the RPE of apoB100 mice exposed to CS with or without HFD (Fig. 1E–H).

With Wnt activation, β-catenin interacts with lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1/T cell factor (Lef1/Tcf) TFs to induce the expression of genes such as cyclinD1. Notably, cyclinD1 mRNA was not induced in the RPE/choroid after CS + HFD relative to mice treated with a normal chow diet and air (Fig. 1I). With oxidative stress, Wnt signaling can shift from Lef1/Tcf to forkhead box O (Foxo) TF cofactor mediated expression of antioxidant genes, such as superoxide dismutase 2 (Sod2) (2, 45). Similarly, Sod2 mRNA was not induced in the RPE/choroid of apoB100 mice given CS + HFD (Fig. 1J). Thus, all of the Wnt components tested were impaired by CS/HFD treatment while 50% (p-Lrp6, β-catenin) were impaired by CS/regular diet (Reg) treatment. In addition, the decrease for Wnt5 and p-Lrp6 was greater after chronic CS/HFD than CS-only exposure. Collectively, while CS impairs Wnt signaling, these results suggest that the combined stress of CS and HFD impairs Wnt signaling to a greater extent than CS treatment alone.

Nrf2 signaling is impaired in a bidirectional feedback loop with oxidative stress

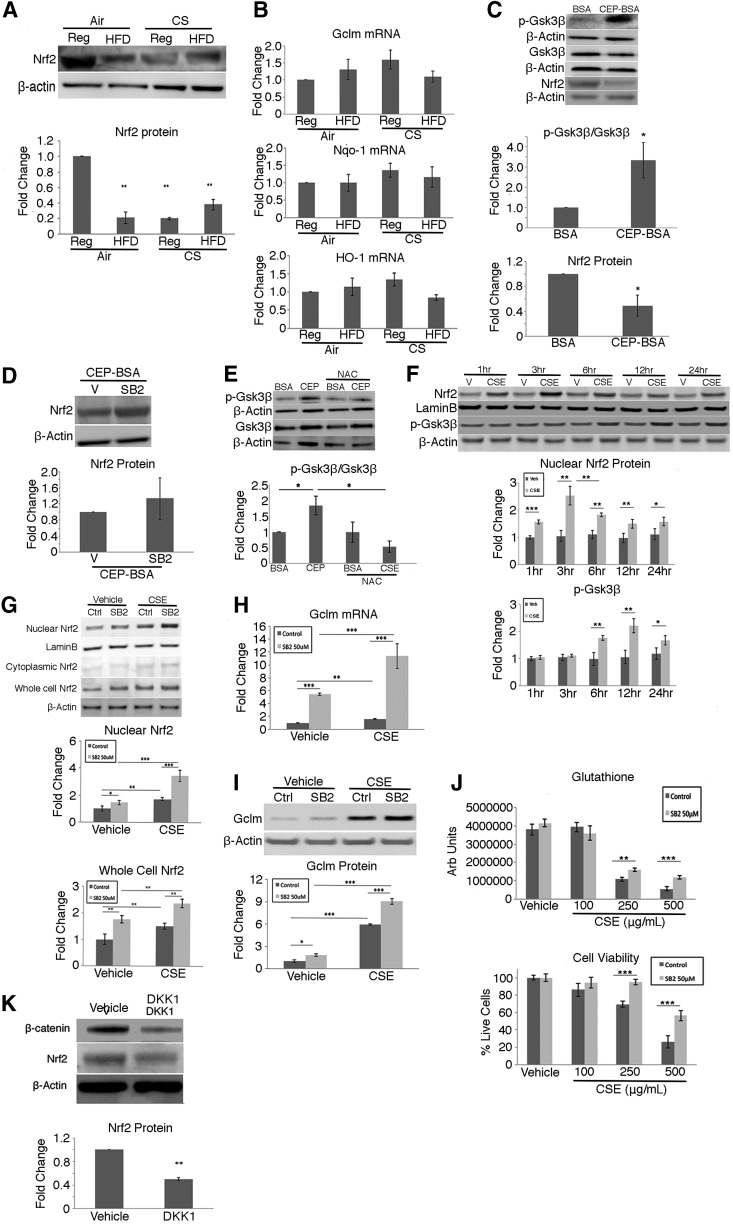

p-Gsk3β (tyr216) can phosphorylate Nrf2 to promote Nrf2 degradation by a kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1)-independent pathway (55). Given the increased p-GSK3β in apoB100 mice treated with CS + HFD, we sought to determine Nrf2 abundance in our animal model. Nrf2 protein (p < 0.01) was decreased in the RPE/choroid of apoB100 mice treated with CS + HFD compared with mice given a normal diet and air (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. S6). This decrease was associated with a blunted response of the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant genes, heme oxygenase 1 (Ho-1), glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit (Gclm), and NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (Nqo-1), and decreased Ho-1 protein (Fig. 2A) in the RPE/choroid of mice treated with CS + HFD relative to mice on a normal diet and air (p < 0.01; Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Nrf2 signaling in the RPE/choroid is decreased in a feedback loop with Wnt after oxidative stress. apoB100 mice were exposed to air or CS and given a regular chow (Reg) or high fat (HFD) for 6 months. Western blot and graph showing (A) decreased Nrf2 and Ho-1, a known Nrf2 antioxidant target, by CS and/or HFD. (B) mRNA expression of Nrf2-dependent genes, Gclm, Nqo-1, and Ho-1, is also not induced after CS + HFD. (C) apoB100 mice were Ivt injected with CEP-BSA or BSA. Western blot and graphs show increased p-Gsk3β/Gsk3β and decreased Nrf2 in CEP-BSA-treated mice. (D) apoB100 mice were then Ivt injected with CEP-BSA with SB216763, a GSK3β inhibitor, or vehicle control. Western blot and graphs showing similar Nrf2 levels. (E) apoB100 mice were Ivt injected with CEP-BSA or BSA with or without the antioxidant NAC. Western blot and graph show that p-Gsk3β/Gsk3β is reduced with NAC. (F) ARPE-19 cells were treated with 100 μg/mL CSE or vehicle control for 1–24 h. Nuclear Nrf2 protein levels peaked after 3 h and then declined, while p-Gsk3β increase started after 6 h. (G) ARPE-19 cells treated with 100 μg/mL CSE or vehicle control were also given ±50 μM SB216763 for 24 h. Western blot and graph showing increased nuclear and whole-cell Nrf2 protein after CS ± SB216763, with minimal cytoplasmic Nrf2. (H) Graph showing increased Gclm mRNA after CSE ± SB216763. (I) Western blot and graph showing increased Gclm protein after CSE ± SB216763. (J) ARPE-19 cells given 0–500 μg/mL CSE or vehicle control for 24 h show a decrease in total glutathione and cell viability by live/dead assay with some recovery after 50 μM SB216763 treatment. (K) apoB100 mice were given Ivt DKK1, a WNT inhibitor, or vehicle. Western blot and graph showing decreased β-catenin and Nrf2. N = 4 mice per group, or for ARPE-19 cells, n = 3 independent experiments. β-Actin or lamin B was used as a loading control. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. BSA, bovine serum albumin; CEP, carboxyethylpyrrole; CSE, cigarette smoke extract; Gclm, glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit; Ho-1, heme oxygenase 1; Ivt, intravitreal; NAC, N-acetyl cysteine; Nqo-1, NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1; Nrf2, nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2.

To demonstrate that p-Gsk3β influences Nrf2 signaling, apoB100 mice were given intravitreal (Ivt) cigarette smoke extract (CSE) or carboxyethylpyrrole (CEP-bovine serum albumin [BSA]), a specific oxidation product of docosahexaenoic acid that accumulates in the outer retina, RPE, and Bruch's membrane in AMD, to stress the RPE and induce Nrf2 (23). As expected, 6 h after Ivt CSE or CEP-BSA, Nrf2 protein from whole-cell lysates or nuclear extracts of RPE/choroid was increased compared to vehicle-injected mice (Supplementary Figs. S7 and S8). By 24 h, Nrf2 (p < 0.05) was decreased, while p-Gsk3β/Gsk3β (p < 0.05) was increased relative to BSA controls (Fig. 2C) and when 50 μM SB216763, a Gsk3β inhibitor, was Ivt injected with CEP-BSA, Nrf2 protein was restored to control levels that received Ivt CEP-BSA and vehicle (Fig. 2D). To demonstrate that oxidative stress mediates Gsk3β phosphorylation, after mice were injected with Ivt CEP-BSA in the presence of the antioxidant N-acetyl cysteine, the p-Gsk3β/Gsk3β was reduced (p < 0.05; Fig. 2E).

Furthermore, we were able to demonstrate similar events in an in vitro model. When human ARPE-19 cells were treated with CSE 100 μg/mL, nuclear Nrf2 protein was increased relative to vehicle-treated cells, in a time-dependent manner, peaking after 3 h, and the subsequent decline in Nrf2 (p < 0.01) coincided with induction of p-Gsk3β after 6 h (Fig. 2F). After ARPE-19 cells were treated with CSE 100 μg/mL and SB216763, Nrf2 was increased in both nuclear and whole-cell lysates, compared to controls, and this increase was magnified by cotreatment with CSE and Gsk3β inhibition (Fig. 2G). In addition, the mRNA (Fig. 2H) and protein (Fig. 2I and Supplementary Fig. S9) levels of Gclm, the rate-limiting enzyme in glutathione synthesis, were induced compared to control treated cells when Gsk3β was inhibited with SB216763, with or without CSE. Gsk3β inhibition with SB216763, as expected, increased total glutathione and protected against oxidant-induced cell death after CSE treatment (Fig. 2J).

Finally, when DKK1, a Wnt signaling inhibitor that is upstream of Gsk3β (21) was Ivt injected in one eye, and vehicle into the contralateral eye of apoB100 mice, β-catenin and Nrf2 were decreased in the RPE/choroid relative to controls (p < 0.01; Fig. 2K), suggesting that Wnt signaling can influence Nrf2 signaling.

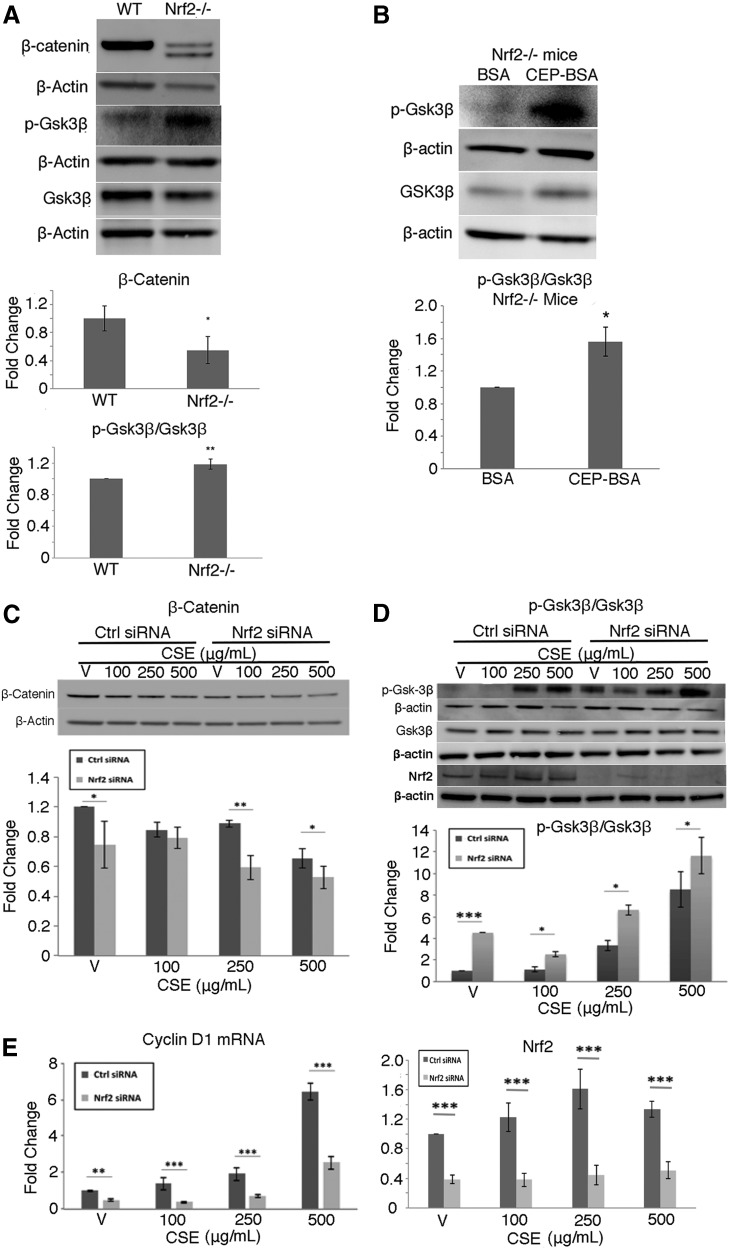

We next wanted to determine whether Nrf2 could influence Wnt signaling. In the RPE/choroid of Nrf2−/− mice compared with C57BL/6J WT mice, β-catenin protein was decreased and p-Gsk3β/Gsk3β was increased (p < 0.05; Fig. 3A). p-Gsk3β/Gsk3β was further induced in Nrf2−/− mice given Ivt CEP-BSA compared to BSA controls (p < 0.01; Fig. 3B). Likewise, in ARPE-19 cells given 0–500 μg/mL CSE, β-catenin was decreased (Fig. 3C), p-Gsk-3β/Gsk-3β was increased (Fig. 3D), and cyclin D1 mRNA was decreased (Fig. 3E) in a dose-dependent manner compared to vehicle controls, an effect that was magnified by Nrf2 knockdown. Collectively, these data identify a bidirectional feedback loop between Nrf2 and Wnt where impaired Nrf2 can decrease Wnt signaling, and decreased Wnt signaling can decrease Nrf2.

FIG. 3.

Impaired Nrf2 signaling decreases Wnt signaling in the RPE/choroid. (A) Western blot and graphs of β-catenin, p-Gsk3β/Gsk3β of Nrf2−/− and C57BL/6J (WT) mice. Note the 85 and 94 kDa bands of β-catenin in Nrf2−/− mice, which is likely due to alternative splicing (www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P35222). N = 5 mice per group. (B) Western blot and graphs showing increased p-Gsk3β/Gsk3β in the RPE/choroid of Nrf2−/− mice after Ivt CEP-BSA compared to BSA controls. ARPE-19 cells were transfected with Nrf2 or scrambled siRNA and then treated with CSE (0–500 μg/mL) for 24 h. (C) Western blot and graph showing reduced β-catenin after Nrf2 knockdown and CSE treatment. (D) Western blot and graph showing increased p-Gsk3β/Gsk3β with CSE that was magnified by Nrf2 knockdown. (E) Cyclin D mRNA expression was decreased by Nrf2 knockdown. N = 4 mice per group or for ARPE-19 cells, n = 3 independent experiments. β-Actin was used as a protein loading control. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. WT, wild type.

The RPE is dysfunctional and dies by apoptosis with posterior GA in apoB100 mice exposed to chronic oxidative stress

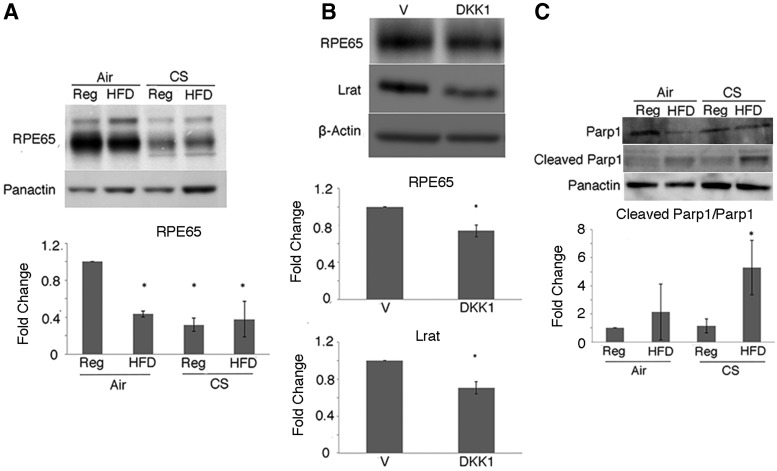

Rpe65, an integral visual cycle protein produced by the RPE that is suppressed by chronic stress, and a valuable indicator of RPE cell terminal differentiation (73), was decreased in the RPE/choroid of apoB100 mice treated with CS + HFD for 6 months relative to mice raised on a chow diet and air (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. S10).

FIG. 4.

The RPE is dysfunctional and dies by apoptosis after oxidative stress, and apoB100 mice develop GA. apoB100 mice were treated with CS or air, and a regular (Reg) or HFD for 6 months. (A) Western blot and graph showing the decreased 65 and 45 kDa fragments of Rpe65 with CS ± HFD (40). (B) apoB100 mice were given Ivt DKK1 or vehicle. Western blot and graph showing decreased Rpe65 and the 65 kDa Lrat band after DKK1. (C) Western blot and graph showing cleaved Parp (25 kDa)/Parp from the RPE/choroid of apoB100 mice treated with CS + HFD for 6 months. N = 4 mice per group. Panactin or β-actin was used as a loading control. *p < 0.05. Parp, poly-ADP ribose polymerase.

To demonstrate that RPE differentiation is impaired after reducing Nrf2 and Wnt, mice were treated with Ivt DKK1. Rpe65 and Lrat, another visual cycle component, were both decreased compared to controls (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. S11). RPE apoptosis is a reported mechanism for RPE cell death in AMD (12). Using poly-ADP ribose polymerase (Parp) cleavage as a marker of apoptosis (71), we found that the 25 kDa cleaved product was increased in the RPE/choroid of apoB100 mice exposed to CS and HFD compared with mice treated with a regular diet and air (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Fig. S12). These results suggest that chronic CS and HFD exposure induces RPE dysfunction and cell death.

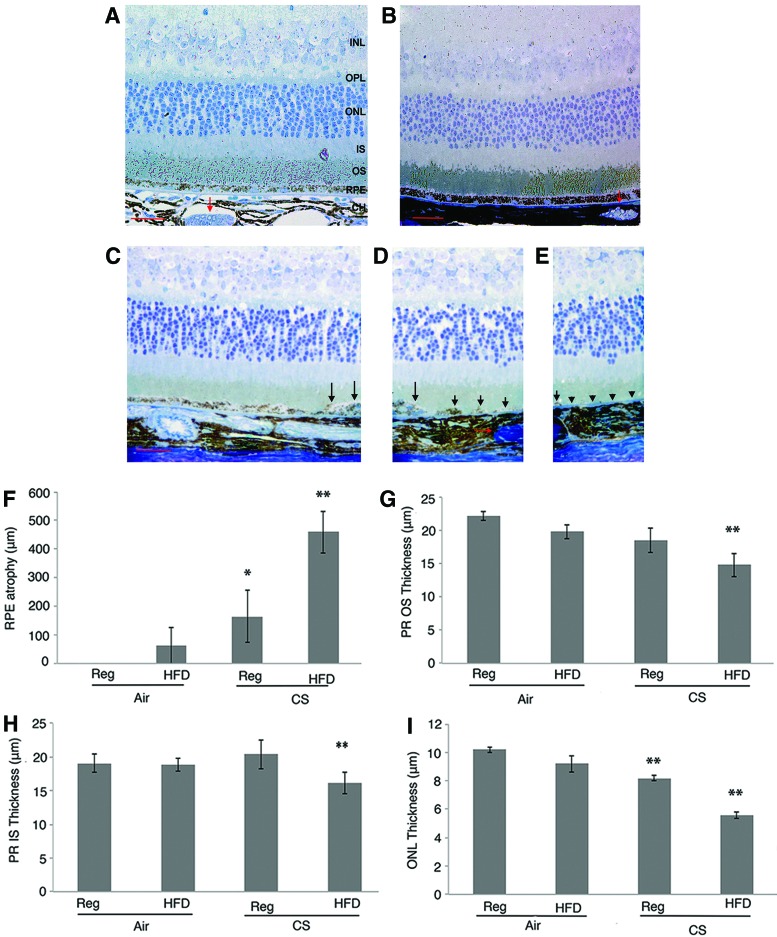

With molecular evidence of impaired Nrf2 and Wnt signaling, RPE dedifferentiation, and cell death, we next assessed the phenotype of apoB100 mice exposed to chronic CS and HFD. Mice raised in air and a normal or HFD did not show overt RPE morphologic changes. In contrast, areas of striking posterior RPE loss with an adjacent transition zone of severely dysmorphic RPE were identified from the optic nerve dorsally in 60% mice exposed to CS alone (n = 10), and 100% of mice exposed to HFD and CS (n = 10; Fig. 5A–E). The length of RPE loss from the optic nerve dorsally was significantly greater (p < 0.01; Fig. 5F), the outer nuclear layer was thinner (Fig. 5G), and the photoreceptor inner and outer segments (Fig. 5H, I) were shortened in mice treated with HFD and CS compared with mice treated with a normal diet and air.

FIG. 5.

Histology of apoB100 mice raised in air or CS, with regular or HFD diet. (A) apoB100 mouse raised in air on a chow diet has normal retina, RPE, BrM, and choriocapillaris. Occasionally, recanalized thrombus in large choroidal vessels (red arrow), was present, but without correlation with RPE or retinal abnormalities. (B) apoB100 mouse raised in air and HFD has preserved retina, RPE, BrM, and choroid. Thrombus, red arrow. apoB100 mouse given CS + HFD has GA. (C) Relatively preserved RPE distal to the transitional zone with RPE layering (long black arrows). (D) Transition zone of the same mouse with RPE layering (long black arrows) adjacent to remnants of RPE cells (short black arrows). Thrombus, red arrow. (E) Atrophic area devoid of RPE cells (arrowheads). Bar = 50 μm. (F) Quantification of posterior RPE atrophy from the optic nerve dorsally was increased. (G) Photoreceptor outer segment (POS) thickness was decreased. (H) Photoreceptor inner segment (IS) thickness was shortened, and (I) ONL thickness was decreased in mice exposed to CS + HFD compared with mice raised in air on a normal diet. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. BrM, Bruch's membrane; CC, choriocapillaris; GA, geographic atrophy; INL, inner nuclear layer; IS, photoreceptor inner segment; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; POS, photoreceptor outer segment. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

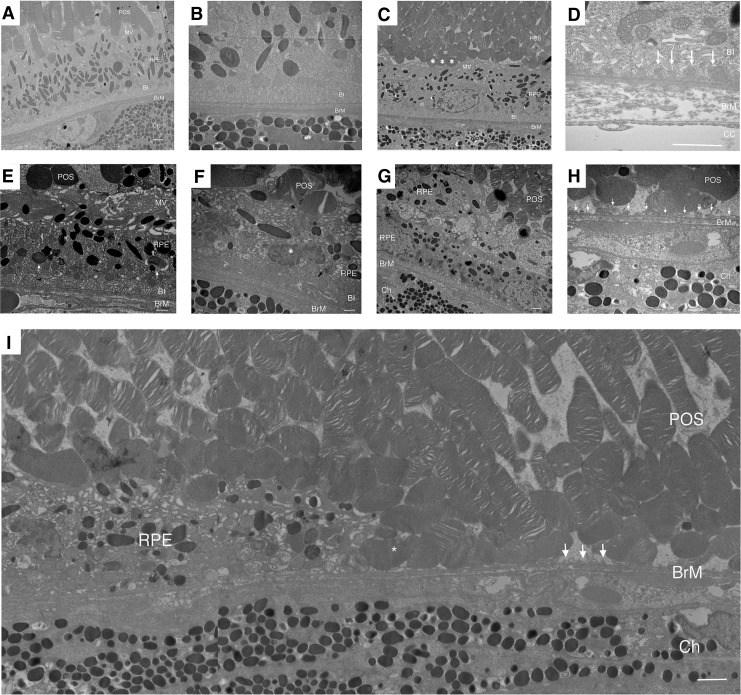

Ultrastructural changes correlated with the morphological alterations. The RPE of apoB100 mice raised in air on a chow diet appeared normal with a normal array of melanin pigment, mitochondria, and intact apical microvilli and basolateral infoldings (Fig. 6A, B). Photoreceptor outer segments were interdigitated with RPE apical microvilli. Bruch's membrane was unthickened, and the choriocapillaris appeared normal. apoB100 mice raised in air on HFD also had normal ultrastructure (Fig. 6C, D). Occasionally, photoreceptor outer segments were truncated and Bruch's membrane had thin, homogeneous basal laminar deposits, which is typical of aging but not AMD (10).

FIG. 6.

The ultrastructure of the RPE of apoB100 mice exposed to CS and HFD for 6 months. (A) apoB100 mouse raised in air on a chow diet with healthy POS, and normal RPE, including apical MV and BI. BrM is unthickened. (B) Higher magnification micrograph of an apoB100 mouse raised in air on a chow diet with normal RPE, BrM, and choroid. (C) apoB100 mouse raised in air on HFD has preserved RPE, BrM, and choroid. Occasional POS are truncated and electrodense (*) (D) Magnified view of an apoB100 mouse raised in air on HFD. The RPE has mild loss and dilated basal infoldings with thin, homogeneous basal laminar deposits (arrows). (E) apoB100 mouse treated with CS and HFD for 6 months with GA. In the distal transition zone, POS are shortened and electrodense, an RPE cell has a flattened cell shape with vacuolization in the cytoplasm, disrupted apical MV, while BI are relatively preserved. Undigested POS appear in the basal aspect of the cell (white arrows). BrM appears normal. (F) Higher magnification of a different RPE cell in the transition zone showing POS and RPE with vacuoles, and shrunken, abnormal nuclei (*), and abnormal BI. (G) Transition zone with multilayered, degenerated RPE cells. (H) Area of GA with electrodense and rounded POS adjacent to RPE remnants (arrows) on BrM. (I) At the edge of GA, RPE cell is degenerated (left) with RPE remnants (white arrows) on BrM. POS (*) are against bare BrM. N = 10 mice per condition. BI, basal infoldings; Ch, choroid; MV, microvilli.

In apoB100 mice given HFD and CS for 6 months, the RPE was progressively deranged in the transition zone with closer proximity to the atrophy in 100% of mice examined (n = 10). At the distal edge, the RPE had a flattened cell shape and altered apical microvilli and cytoplasmic vacuoles, but preserved basal infoldings (Fig. 6E, F). In some cells, the nuclei were condensed with dense heterochromatin, mitochondria were swollen with dilated matrices, and the cytoplasm contained multiple membranous vacuoles, which are all suggestive of apoptosis (11, 19). In addition, the RPE basal infoldings were enlarged and truncated, seen in degenerated RPE in AMD (22).

Within the transition zone, the RPE was multilayered with flattened cell shape (Fig. 6G). Within the atrophy, only RPE cell remnants remained, and degenerated photoreceptor outer segments sit on Bruch's membrane (Fig. 6H, I). Similar features were seen in apoB100 mice given a normal diet and exposed to CS for 6 months (Supplementary Fig. S13).

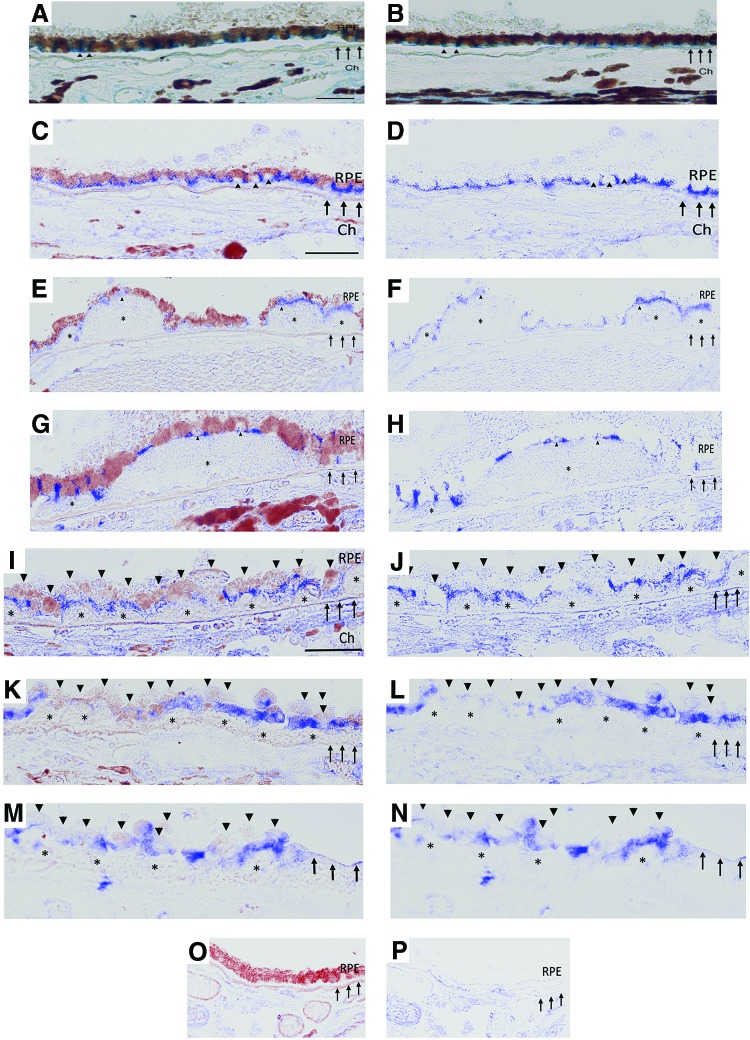

β-Catenin and Gsk3β immunolabeling are altered in AMD

To provide relevance to human AMD, the distribution of β-catenin and Gsk3β in AMD samples was assessed by immunohistochemistry using validated antibodies (29, 38, 49, 50, 68, 70). In the RPE of control eyes, β-catenin staining appeared as a regular band at the basolateral aspect of normal appearing RPE cells in the macula and periphery (Fig. 7A, B). In early AMD (Fig. 7C–H), β-catenin labeling in morphologically preserved RPE adjacent to drusen maintained a regular band at the basolateral aspect of the cell while in dysmorphic, rounded RPE, as in apoB100 mice given CS with or without HFD, was thickened and globular in the lateral cell wall, and was prominent basally or in the sub-RPE space. β-Catenin was also found in basal deposits and drusen. In GA (Fig. 7I–N), the RPE without atrophy had a similar pattern of basolateral labeling, while dysmorphic or migrating RPE cells in the transition zone and atrophic areas had minimal to no β-catenin labeling (Table 1).

FIG. 7.

Distribution of β-catenin in early and late AMD. An 83-year-old female without AMD has regular RPE in the macula (A) and periphery (B). β-Catenin has a regular pattern of immunolabeling (blue) along the lateral (arrowheads) and basal periphery of the RPE cell. (C) Uninvolved macular section from a 60-year-old male with early AMD illustrates similar, regular β-catenin immunolabeling of the lateral and basal RPE. (D) Nuance processed image from (C) with melanin subtracted to improve visualization of β-catenin labeling. (E) β-Catenin is unevenly distributed, but basally located in dysmorphic RPE overlying drusen (*). (F) Nuance processed image of (E). (G) β-Catenin labeling is preserved at the basolateral aspect of intact RPE adjacent to mildly deranged RPE overlying a drusen (*), having unevenly distributed and basally localized β-catenin. (H) Nuance processed image of (G). β-Catenin labeling in a 69-year-old female with GA. (I) β-Catenin labeling is in the basal and lateral margin of dysmorphic, multilayered RPE cells (arrowheads) in the transition zone. Confluent drusen (*) seen. (J) Nuance processed image of (I). (K) β-Catenin in transition zone is irregularly distributed in multilayered, flattened RPE cells overlying drusen (*). Migrating RPE (adjacent to the retina) has minimal to no labeling. (L) Nuance processed image of (K). (M) Irregular, basal β-catenin labeling in multilayered, dysmorphic RPE adjacent to an area of GA (right edge) where the RPE is absent. (N) Nuance processed image of (M). Ch, choroid; Arrows, Bruch's membrane. (O) IgG control. (P) Nuance processed image of (O). Bar = 25 μm. AMD, age-related macular degeneration; IgG, immunoglobulin G. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Table 1.

Summary of β-Catenin Immunostaining

| Donor | Age (years) | Gender | Race | D–E (h) | Cause of death | Normal RPE | RPE adjacent to drusen | Dysmorphic RPE | RPE over drusen | Migrating RPE | Drusen | Basal deposit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 30 | F | C | 11 | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 2 | 39 | M | C | 32 | Pulmonary embolism | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 3 | 44 | F | C | 46 | Cystic fibrosis | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 4 | 48 | F | C | 21 | Sepsis | Yes | Yes | No | No | — | No | No |

| 5 | 67 | M | C | 10 | CFH | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 6 | 78 | M | C | 10 | Prostate cancer | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 7 | 78 | F | A | 15 | Pulmonary fibrosis | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 8 | 83 | F | C | 12 | Alzheimer | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 9 | 87 | M | C | 24 | Pneumonia | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| NNV AMD | ||||||||||||

| 10 | 60 | M | B | 28 | CFH | Yes | Globular | No | No | — | No | Yes |

| 11 | 61 | M | C | 30 | Pneumonia | Yes | Diffuse | No | No | — | No | Yes |

| 12 | 61 | M | C | 20 | MI | Yes | Yes | No | No | — | No | — |

| 13 | 69 | F | C | 19 | Pneumonia | Yes | Globular | No | No | — | No | Yes |

| 14 | 83 | F | C | 14 | Ischemic bowel | Yes | Yes | No | No | — | No | — |

| 15 | 85 | M | C | 24 | Pneumonia | Yes | Yes | No | No | — | No | — |

| 16 | 87 | F | C | 20 | MI | Yes | Yes | No | No | — | No | — |

| 17 | 93 | M | C | 24 | Melanoma | Yes | Yes | No | No | — | No | — |

| 18 | 95 | F | C | 6 | CVA | Yes | Yes | No | No | — | No | Yes |

| 19 | 96 | F | C | 8 | Alzheimer | Yes | Yes | No | No | — | No | Yes |

| 20 | 96 | M | C | 5 | CFH | Yes | Globular | No | No | — | No | — |

| Geographic atrophy | ||||||||||||

| 21 | 86 | M | C | 24 | Prostate cancer | Yes | Globular | Globular | No | No | No | Yes |

| 22 | 86 | F | C | 24 | Lung cancer | N/A | Globular | No | No | No | No | — |

| 23 | 91 | F | C | 22 | Pneumonia | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

Immunolabeling was designated as “yes” when present or “no” when absent. When applicable, the immunolabeling pattern was designated as “globular” or “diffuse.”

AMD, age-related macular degeneration; CFH, Congestive Heart Failure; CVA, Cerebral Vascular accident; D–E, death to enucleation time in hours; MI, Myocardial infarction; N/A, Not available; NNV, Non-Neovascular; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium.

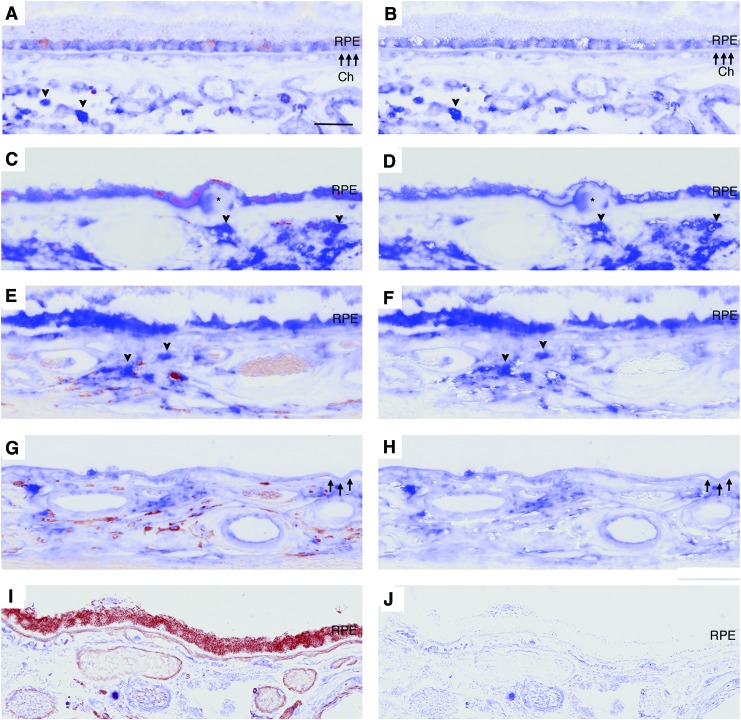

Compared to strongly labeled choroidal cells, Gsk3β immunolabeling was lightly stained and diffusely distributed in the cytoplasm of morphologically normal RPE. In dysmorphic RPE, whether adjacent to or overlying drusen, Gsk3β labeling was strong, consistent, and diffuse in the cytoplasm compared to choroidal cells in the same section. Prominent immunolabeling was observed in the RPE of early AMD, and was similar in dysmorphic and migrating RPE in the transition zone of GA (Fig. 8A–H). Strong Gsk3β staining was also observed in drusen and basal laminar deposits, as summarized in Table 2.

FIG. 8.

Distribution of Gsk3β in AMD. (A) Forty-year-old male without AMD with diffuse Gsk3β labeling in macular RPE. The staining is lighter than choroidal cells (arrowhead). (B) Nuance processed image of (A). (C) Ninety-six-year-old male with early AMD with strong, diffuse Gsk3β labeling in the RPE, including over a drusen (*) compared to strong choroidal cell labeling (arrowhead). (D) Nuance processed image of (C). (E) Eighty-six-year-old male with GA. The RPE in the transition zone has strong, diffuse cytoplasmic Gsk3β labeling that is similar in intensity to choroidal cells (arrowhead). (F) Nuance processed image of (E). (G) Area of GA of the same patient as (E) that is devoid of RPE. BrM has Gsk3β labeling. (H) Nuance processed image of (G). (I) IgG control. (J) Nuance processed image of (I). Arrowheads, BrM. Bar = 25 μm. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Table 2.

Immunolabeling for Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 Beta

| Donor | Age (years) | Gender | Race | D–E (h) | Cause of death | Normal RPE | RPE adjacent to drusen | Dysmorphic RPE | RPE over drusen | Migrating RPE | Drusen | Basal deposit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 40 | M | C | 16 | Leukemia | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 2 | 49 | M | B | 28 | Esophageal hemorrhage | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 3 | 61 | F | B | 24 | Pneumonia | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| NNV AMD | ||||||||||||

| 4 | 77 | M | C | 8 | Pulmonary hemorrhage | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | — | — |

| 5 | 77 | F | C | 24 | MI | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | — |

| 6 | 81 | M | C | 24 | MI | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | Yes | — |

| 7 | 85 | F | C | 10 | Alzheimer | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | — | — |

| 8 | 91 | F | C | 22 | Pneumonia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | — | — |

| 9 | 96 | M | C | 5 | Cardiomegaly | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | — | — |

| Geographic atrophy | ||||||||||||

| 10 | 86 | M | C | 24 | CFH | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | — |

| 11 | 86 | F | C | 20 | Lung cancer | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | — | — |

Immunolabeling was designated as “yes” when present or “no” when absent.

Discussion

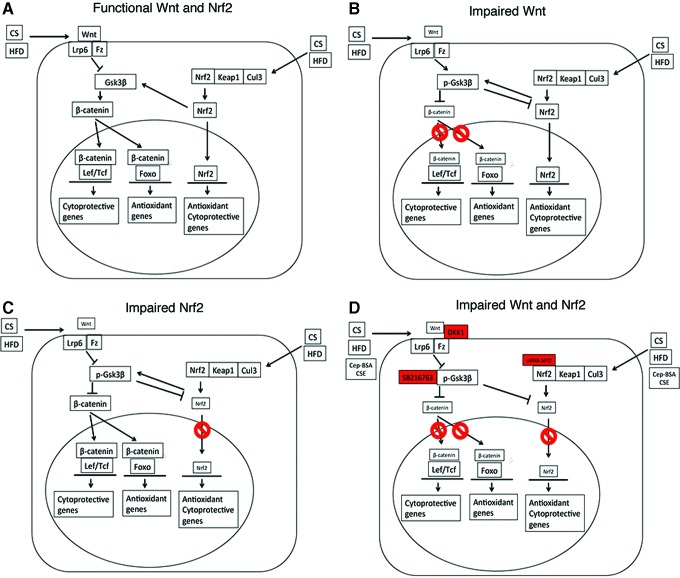

Herein, we describe a new molecular mechanism of two critical cytoprotective pathways, Wnt and Nrf2, which are impaired in a bidirectional feedback loop in the RPE after apoB100 mice were exposed to two environmental AMD risk factors (Fig. 9). Importantly, the impairment of two, rather than a single cytoprotective pathway, contributed to a phenotype that vividly mimics human GA, including consistent RPE atrophy with overlying photoreceptor loss in the posterior fundus, and a surrounding transition zone of progressive RPE degeneration and heterogeneity, which is a hallmark change seen in human AMD (24). Importantly, in the transition zone, some dysmorphic RPE were multilayered, a key finding that to the best of knowledge, has not been reported in other mouse models, yet is a unique and critical feature in GA (58). Our immunohistochemical studies of aberrant β-catenin and GSK3β labeling in human AMD samples and our prior work showing decreased Nrf2 in dysmorphic RPE of AMD samples (67) suggest that a similar mechanism is involved in human AMD.

FIG. 9.

Diagram of interactive communication between Nrf2 and Wnt signaling that, when dysfunctional, leads to RPE dysfunction and death. (A) Healthy RPE cell with functional Nrf2 and Wnt signaling. CS and/or HFD can impair either (B) Wnt or (C) Nrf2 signaling that impairs the other system through p-Gsk3β, resulting in (D) a decrease in both Wnt and Nrf2 signaling, ultimately leading to severe RPE cell function and cell death. The inhibitory reagents used in this study are indicated at their sites of inhibition. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Currently, there is no treatment for GA due to a limited understanding of the critical events that lead to RPE atrophy and the absence of a model that mimics essential phenotypic features. The identification of two impaired, interacting cytoprotective pathways provides new insights into the mechanism of RPE degeneration. Since GA progression is related to the extent of damaged RPE in the transition zone (33), this model will be helpful in delineating how and why GA develops and enlarges, and will be valuable for testing new targets intended to either slow or reverse RPE degeneration.

Cell signaling pathways are organized as intertwined communication networks, which are finely tuned by regulators, and are a critical feature of physiological signaling designed to protect any given cell against endogenous or exogenous stressors. Both Wnt and Nrf2 responded to acute stressors in our experiments. Chronic stress can impair these protective systems. Indeed, chronic CS exposure was a driving factor in suppressing Nrf2 and Wnt signaling. The added burden of chronic HFD to CS exposure also impaired Nrf2 signaling and resulted in a more global suppression of Wnt signaling than CS alone. With chronic CS and HFD, 100% of the Wnt pathway components tested (Wnt5, p-LRP6, Gsk3β, and β-catenin) were decreased, while 50% of Wnt components (p-Lrp6, β-catenin) were impaired with CS only. In addition, the decrease in Wnt5 and p-Lrp6 was greater after chronic CS/HFD than CS-only treatment. The degree of Nrf2 and Wnt suppression correlated with the GA phenotype. With Nrf2 impairment and the more complete suppression of Wnt signaling by the combined stresses of CS and HFD, 100% of mice developed GA, while 60% of mice treated with CS only developed GA. These data support our theory that impairing two rather than a single cytoprotective pathway is more likely to induce GA.

Wnt and Nrf2 impairment contributed to each other's decline in a bidirectional feedback loop. L'Episcopo et al. found that impaired Nrf2 could deregulate Wnt signaling (37), while Rada et al. found that Wnt activated Nrf2 signaling by preventing Nrf2 phosphorylation through Gsk3β and Swi4-Swi6 cell-cycle box/β-transducin repeat containing protein (SCB/β-TrCP) mediated proteasomal degradation (55, 56). In our studies, Nrf2−/− mice had reduced β-catenin in the RPE compared with WT mice, an effect that was magnified by oxidative stress. In human ARPE-19 cells, Nrf2 knockdown also reduced β-catenin, increased p-Gsk3β, and reduced the expression of cyclin D, a downstream target of WNT signaling, to collectively suggest that Nrf2 influences WNT signaling. By inhibiting Wnt with DKK1, which is upstream of Gsk3β, Nrf2 was reduced, and inhibiting Gsk3β with SB216763 restored Nrf2 in apoB100 mice. Likewise, inhibiting Gsk3β with SB216763 in ARPE-19 cells restored Nrf2 levels and expression of Gclm, a known Nrf2 responsive antioxidant after an oxidative stress challenge. These results indicate that Wnt regulates Nrf2 signaling, in part, by modulating GSK3b activity, and Nrf2 regulates Wnt signaling.

Under basal conditions, Nrf2 is bound to Keap1 and is presented to the Cullin-3/Rbx1 complex for proteasomal degradation (27). With acute oxidative stress, several cysteines interact with electrophilic compounds to induce a conformational change in Keap1, releasing Nrf2 for translocation to the nucleus and the transcription of antioxidant genes. However, chronic oxidative stress, with persistently elevated basal electrophile levels, lacks an acute electrophile rise so that Nrf2 is not released from Keap1 (27). Under these conditions, Gsk3β can be activated to phosphorylate Nrf2, leading to β-TrCP/Cullin1/Rbx1 E3 ligase-mediated ubiquitinated proteasomal degradation (55, 56), acutely raising the electrophile level to release Nrf2 from Keap1. With excessive, constitutive Gsk3β activity, Nrf2 could remain decreased at levels that will prevent a cytoprotective response. This scenario is plausible with decreased Wnt signaling and chronic Gsk3β activation as in our study.

Several factors may contribute to impaired Wnt signaling in our model. First, the RPE of apoB100 mice, relative to WT mice that do not produce apoB100, had reduced expression of key Wnt molecules, notably Wnt5a and Lrp6. While inconsequential under basal conditions, their relatively suppressed expression might reduce Wnt signaling under duress. While Wnt5a was identified as the most abundantly expressed Wnt ligand, other Wnt ligands could be relevant, including Wnt5b, since the antibody used for this study, which is the only mouse Wnt5 antibody commercially available, recognizes both Wnt5a and 5b.

Second, oxidative stress can decrease Wnt transcription to blunt the Wnt signaling response (65, 74). Third, HFD itself can impair Wnt signaling (53). Fourth, the very low-density lipoprotein receptor (Vldlr) can form a heterodimer with Lrp6 to reduce Wnt signaling (41). Since either HFD or oxidative stress can induce Vldlr expression (36), it is possible that our conditions induced Vldlr, which suppressed Wnt signaling. Finally, just as impaired Wnt signaling contributed to Nrf2 decline, the decreased Nrf2 response likely contributed to decreased Wnt signaling.

Competent Wnt and Nrf2 signalings are essential for cell survival under oxidative stress because they regulate different cytoprotective networks, yet they are interconnected. β-Catenin classically binds to Tcf to induce the transcription of cell survival and differentiation genes such as cyclin D1, but oxidative stress induces a shift in cofactor activity to Foxo TF-mediated expression of antioxidant genes such as Sod2 (2, 45). While this switch is undoubtedly a cytoprotective response, in osteoblasts, the switch comes at the expense of Tcf-mediated transcription, reducing osteoblast differentiation that culminates in osteoporosis (2, 45). In our studies, neither cyclinD1 nor Sod2 was induced by chronic oxidative stress, which suggests that both Tcf and Foxo mediated gene expression, which could contribute to RPE dedifferentiation and reduce the antioxidant response, respectively, and are impaired. Furthermore, since Sod2 can also be regulated by Nrf2 (60), impaired Nrf2 signaling could also be a contributing factor. Under these conditions, the antioxidant response from two systems was inadequate to prevent RPE degeneration.

Our laboratory and other investigators have investigated the role of dysregulated complement, inflammasome activation, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and impaired autophagy in AMD (7, 13, 25, 30, 34, 35, 48, 59, 72). At present, it is unclear at what point during disease pathophysiology that these derangements contribute to AMD. Both Nrf2 and Wnt can influence complement (51) and inflammasome activation (66), ER stress (64), and autophagy (20, 52). The interaction of these systems with Wnt and Nrf2 signaling, and their impact on disease development, has not been explored to any significant extent. Given the influence of Wnt and Nrf2 on these systems, future investigation is warranted.

Research has uncovered impaired Wnt or Nrf2 signaling in a number of prominent complex diseases such as Alzheimer's (28, 31, 42), Parkinson's (3, 18, 40, 54), and Huntington's disease (62, 63), atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease (44), diabetes mellitus (32, 45), alcoholic liver disease (39), and age-related osteoporosis (2, 45). These studies have focused on one signaling system or the other. With the cross talk between Wnt and Nrf2 signaling in the RPE that resulted in impaired signaling of both cytoprotective pathways and mechanistically involved with an AMD phenotype, future research should consider the interaction and synergistic impact of impairment of both essential systems in these complex diseases.

Materials and Methods

Mice and animal care

All experiments were conducted according to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, and the IRB at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions approved the research. An equal number of male and female apoB100 mice, in a B6;129S background, and Nrf2−/− mice in a C57BL/6J background (27), without the RD8 mutation, were used for experiments. Mice were fed standard rodent chow or HFD consisting of 60% fat, 20% protein, and 20% carbohydrate (Research Diets, Inc., New Brunswick, NJ). Mice were given water ad libitum and kept in a 12-h light–12-h dark cycle. For some experiments, mice received an Ivt injection in one eye and an equal volume (1 μL) of vehicle control in the contralateral eye using a microinjection pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA).

Exposure to cigarette smoke

At 8 weeks of age, mice were kept in a filtered air environment or placed in a smoking chamber for 2.5 h/day, 5 days/week, for 6 months, using our published protocol (17).

Tissue preparation

After mice were sacrificed, eyes were enucleated and the retina and RPE/choroid were dissected to extract protein or RNA or the eyes were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and cryopreserved for immunohistochemistry or 2.5% glutaraldehyde/1% paraformaldehyde in 0.08 M cacodylate buffer for electron microscopy.

Cell culture

Human ARPE-19 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM)/F12 with 15 mM HEPES buffer, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 2 mM l-glutamine solution at 37°C until confluent, and then grown in DMEM/F12. Cells were transfected with either 30 nM Nrf2 siRNA (Applied Biosystems, Inc. Foster City, CA) or control siRNA for 24 h, serum starved for 24 h, and treated with 0–500 μg/mL CSE (Murty Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Lexington, KY) for 24 h, as described (67).

RNA extraction

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Plus-kit (Qiagen, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). RNA quality was confirmed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Reverse transcription was performed using random hexamers and MultiScribe reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analyses were performed using Assay-on-Demand primer and probe sets (Applied Biosystems) with a StepOnePlus TaqMan system (Applied Biosystems). β-Actin was used for normalization.

Subcellular protein fractionation

Cell pellets or small tissue pieces were washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed or homogenized in the cold CER I buffer, provided by the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), with an additional Sigma FAST Protease Inhibitor added. Cytoplasmic and nuclear protein fractions were prepared sequentially, following the manufacturer's protocol, and quantified using the BioRad DC Protein Assay Kit.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described (67). Membranes were incubated with the intended primary antibody (β-catenin, cleaved Parp, Lrp 6, GAPDH, p-Gsk3β [tyr216], Nrf2, Wnt3) (Abcam, Inc., San Francisco, CA) and p-Lrp6 (Ser1490), Gsk3β, Rpe65, Wnt5 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), Ho-1, Lrat (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), Gclm (Abcam, Inc.). Signal was detected with a chemiluminescence detection system (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Blots were imaged with an ImageQuant LAS4000 scanner (GE Healthcare, Inc., Piscataway, NJ), and band intensity is reported as arbitrary densitometric units using ImageJ software. β-Actin or panactin was used for signal normalization.

Light and transmission electron microscopy

The posterior segments of eyes were postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated, and embedded in Poly/Bed 812 resin (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA). Semithin sections were stained with Toluidine blue. To quantify areas of GA, semithin sections were imaged with a BX50 light microscope (Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan) and images were acquired with a digital camera (DP22; Olympus Optical Co.). Temporally, the caliper was used to measure the length of RPE atrophy from the optic nerve, or the thickness of the inner and outer photoreceptor segment layers and outer nuclear layer within 1000 μm from optic nerve. As a comparative measure of outer nuclear layer thickness, the number of nuclei in each column was counted.

Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined with a JEM-100 CX electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) in the Wilmer Core Facility.

Immunohistochemistry

Mouse cryosections (10 μm) were blocked with 5% goat serum, incubated overnight with rabbit monoclonal anti-β-catenin (Abcam), and then with Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit (Life Technologies) for 1 h, as previously described (6). Appropriate rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG; Santa Cruz Biotech) was used as isotype control. Sections were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope.

Autopsy eyes (n = 31) were obtained from the Wilmer Eye Institute Pathology Division after approval from the Human Subjects Committee at Johns Hopkins University. “Unaffected” eyes (n = 12) had no AMD history or microscopic evidence of AMD. Early AMD donors had an AMD history and macular drusen (n = 16). Small drusen had a diameter of ≤4 RPE cells (<63 μm) and large drusen as >8 RPE cells (∼125 μm). GA samples (n = 3) had a known history and microscopic evidence of RPE atrophy.

Eyes were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, paraffin embedded, and sectioned at 4 μm thickness. Antigens were retrieved with the Target Retrieval System (Dako, Inc., Carpinteria, CA). Sections were incubated with goat blocking serum and then with validated antibodies, rabbit anti-human β-catenin monoclonal antibody (38, 50, 68, 70) (1:250 dilution; Abcam, Inc.) and anti-Gsk3β (29, 49) or isotype rabbit monoclonal IgG (1:250 dilution; Epitomics, Inc.; Burlingame, CA), overnight at 4°C. Sections were incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG and then with the ABC-AP reagent (Vector Labs). Slides were developed with blue substrate working solution (Vector Labs) supplemented with levamisole. Sections were imaged with a light microscope equipped with the Cri-Nuance system (Caliper Life Sciences, Inc., Hopkinton, MA) to subtract out the melanin pigment.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the Student's two-tailed unpaired t test, or for multiple comparisons, the Kruskal–Wallis test using GraphPad software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). For in vitro experiments, each condition was tested in triplicate and each experiment was repeated at least three times. Blots are selected as the representative of the experiment, and graphs summarize the mean ± standard error of the mean of at least three independent experiments. For in vivo experiments, 3–6 mice were used for each condition, and 10 mice for transmission electron microscopy.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviation Used

- AMD

age-related macular degeneration

- apoB100

apolipoprotein B100

- BI

basal infoldings

- BrM

Bruch's membrane

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CC

choriocapillaris

- CEP

carboxyethylpyrrole

- Ch

choroid

- CS

cigarette smoke

- CSE

cigarette smoke extract

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified eagle medium

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- Foxo

forkhead box O

- GA

geographic atrophy

- Gclm

glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit

- GSK3β

glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta

- HFD

high-fat diet

- Ho-1

heme oxygenase 1

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- Ivt

intravitreal

- Keap1

kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- Lef1/Tcf

lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1/T cell factor

- Lrp6

lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6

- MV

microvilli

- Nqo-1

NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1

- Nrf2

nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2

- Parp

poly-ADP ribose polymerase

- POS

photoreceptor outer segments

- Reg

regular diet

- RPE

retinal pigment epithelium

- SCB/β-TrCP

Swi4-Swi6 cell-cycle box/β-transducin repeat containing protein

- SOD2

superoxide dismutase 2

- TF

transcription factor

- Vldlr

very low-density lipoprotein receptor

- WB

Western blot

- Wnt

wingless

- WT

wild type

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen Chan, Sonny Dike, Natalia Vergara, Christian Gutierrez, and Gillian Shaw for their technical expertise and guidance, and Akrit Sodhi, MD, PhD, and Debasish Sinha, PhD, for carefully critiquing the article. We thank Victor Perez, MD, for providing CEP-BSA. Supported by the NIH EY019904 (J.T.H.), EY14005 (J.T.H.), EY027691 (J.T.H.), EY 01765 (Wilmer Imaging Core grant), K12 EY108198 (K.B.E.), RPB Senior Scientist Award (J.T.H.), unrestricted grant from RBP, and gifts from the Merlau family and Aleda Wright.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Alder VA. and Cringle SJ. The effect of the retinal circulation on vitreal oxygen tension. Curr Eye Res 4: 121–129, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almeida M, Han L, Martin-Millan M, O'Brien CA, and Manolagas SC. Oxidative stress antagonizes Wnt signaling in osteoblast precursors by diverting beta-catenin from T cell factor- to forkhead box O-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem 282: 27298–27305, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson ER, Salto C, Villaescusa JC, Cajanek L, Yang S, Bryjova L, Nagy II, Vainio SJ, Ramirez C, Bryja V, and Arenas E. Wnt5a cooperates with canonical Wnts to generate midbrain dopaminergic neurons in vivo and in stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: E602–E610, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boren J, Veniant MM, and Young SG. Apo B100-containing lipoproteins are secreted by the heart. J Clin Invest 101: 1197–1202, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown GC, Brown MM, Sharma S, Stein JD, Roth Z, Campanella J, and Beauchamp GR. The burden of age-related macular degeneration: a value-based medicine analysis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 103: 173–184; discussion 184–186, 2005 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cano M, Wang L, Wan J, Barnett BP, Ebrahimi K, Qian J, and Handa JT. Oxidative stress induces mitochondrial dysfunction and a protective unfolded protein response in RPE cells. Free Radic Biol Med 69C: 1–14, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen C, Cano M, Wang JJ, Li J, Huang C, Yu Q, Herbert TP, Handa JT, and Zhang SX. Role of unfolded protein response dysregulation in oxidative injury of retinal pigment epithelial cells. Antioxid Redox Signal 20: 2091–2106, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Congdon N, O'Colmain B, Klaver CC, Klein R, Munoz B, Friedman DS, Kempen J, Taylor HR, and Mitchell P. Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol 122: 477–485, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cruess AF, Zlateva G, Xu X, Soubrane G, Pauleikhoff D, Lotery A, Mones J, Buggage R, Schaefer C, Knight T, and Goss TF. Economic burden of bilateral neovascular age-related macular degeneration: multi-country observational study. Pharmacoeconomics 26: 57–73, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curcio CA. and Millican CL. Basal linear deposit and large drusen are specific for early age-related maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 117: 329–339, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doonan F. and Cotter TG. Morphological assessment of apoptosis. Methods 44: 200–204, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunaief JL, Dentchev T, Ying GS, and Milam AH. The role of apoptosis in age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 120: 1435–1442, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards AO, Ritter R, 3rd, Abel KJ, Manning A, Panhuysen C, and Farrer LA. Complement factor H polymorphism and age-related macular degeneration. Science 308: 421–424, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farese RV, Jr, Veniant MM, Cham CM, Flynn LM, Pierotti V, Loring JF, Traber M, Ruland S, Stokowski RS, Huszar D, and Young SG. Phenotypic analysis of mice expressing exclusively apolipoprotein B48 or apolipoprotein B100. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93: 6393–6398, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman DS, O'Colmain BJ, Munoz B, Tomany SC, McCarty C, de Jong PT, Nemesure B, Mitchell P, and Kempen J. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol 122: 564–572, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujihara M, Cano M, and Handa JT. Mice that produce ApoB100 lipoproteins in the RPE do not develop drusen yet are still a valuable experimental system. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55: 7285–7295, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujihara M, Nagai N, Sussan TE, Biswal S, and Handa JT. Chronic cigarette smoke causes oxidative damage and apoptosis to retinal pigmented epithelial cells in mice. PLoS One 3: e3119, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galli S, Lopes DM, Ammari R, Kopra J, Millar SE, Gibb A, and Salinas PC. Deficient Wnt signalling triggers striatal synaptic degeneration and impaired motor behaviour in adult mice. Nat Commun 5: 4992, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galluzzi L, Maiuri MC, Vitale I, Zischka H, Castedo M, Zitvogel L, and Kroemer G. Cell death modalities: classification and pathophysiological implications. Cell Death Differ 14: 1237–1243, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao C, Cao W, Bao L, Zuo W, Xie G, Cai T, Fu W, Zhang J, Wu W, Zhang X, and Chen YG. Autophagy negatively regulates Wnt signalling by promoting Dishevelled degradation. Nat Cell Biol 12: 781–790, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glinka A, Wu W, Delius H, Monaghan AP, Blumenstock C, and Niehrs C. Dickkopf-1 is a member of a new family of secreted proteins and functions in head induction. Nature 391: 357–362, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green WR. and Enger C. Age-related macular degeneration histopathologic studies. The 1992 Lorenz E. Zimmerman lecture. Ophthalmology 100: 1519–1535, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu X, Meer SG, Miyagi M, Rayborn ME, Hollyfield JG, Crabb JW, and Salomon RG. Carboxyethylpyrrole protein adducts and autoantibodies, biomarkers for age-related macular degeneration. J Biol Chem 278: 42027–42035, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guidry C, Medeiros NE, and Curcio CA. Phenotypic variation of retinal pigment epithelium in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43: 267–273, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haines JL, Hauser MA, Schmidt S, Scott WK, Olson LM, Gallins P, Spencer KL, Kwan SY, Noureddine M, Gilbert JR, Schnetz-Boutaud N, Agarwal A, Postel EA, and Pericak-Vance MA. Complement factor H variant increases the risk of age-related macular degeneration. Science 308: 419–421, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haines JL, Schnetz-Boutaud N, Schmidt S, Scott WK, Agarwal A, Postel EA, Olson L, Kenealy SJ, Hauser M, Gilbert JR, and Pericak-Vance MA. Functional candidate genes in age-related macular degeneration: significant association with VEGF, VLDLR, and LRP6. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47: 329–335, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Itoh K, Chiba T, Takahashi S, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Katoh Y, Oyake T, Hayashi N, Satoh K, Hatayama I, Yamamoto M, and Nabeshima Y. An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 236: 313–322, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jo C, Gundemir S, Pritchard S, Jin YN, Rahman I, and Johnson GV. Nrf2 reduces levels of phosphorylated tau protein by inducing autophagy adaptor protein NDP52. Nat Commun 5: 3496, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juhlin CC, Haglund F, Villablanca A, Forsberg L, Sandelin K, Branstrom R, Larsson C, and Hoog A. Loss of expression for the Wnt pathway components adenomatous polyposis coli and glycogen synthase kinase 3-beta in parathyroid carcinomas. Int J Oncol 34: 481–492, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaneko H, Dridi S, Tarallo V, Gelfand BD, Fowler BJ, Cho WG, Kleinman ME, Ponicsan SL, Hauswirth WW, Chiodo VA, Kariko K, Yoo JW, Lee DK, Hadziahmetovic M, Song Y, Misra S, Chaudhuri G, Buaas FW, Braun RE, Hinton DR, Zhang Q, Grossniklaus HE, Provis JM, Madigan MC, Milam AH, Justice NL, Albuquerque RJ, Blandford AD, Bogdanovich S, Hirano Y, Witta J, Fuchs E, Littman DR, Ambati BK, Rudin CM, Chong MM, Provost P, Kugel JF, Goodrich JA, Dunaief JL, Baffi JZ, and Ambati J. DICER1 deficit induces Alu RNA toxicity in age-related macular degeneration. Nature 471: 325–330, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanninen K, Heikkinen R, Malm T, Rolova T, Kuhmonen S, Leinonen H, Yla-Herttuala S, Tanila H, Levonen AL, Koistinaho M, and Koistinaho J. Intrahippocampal injection of a lentiviral vector expressing Nrf2 improves spatial learning in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 16505–16510, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitamura T, Nakae J, Kitamura Y, Kido Y, Biggs WH, 3rd, Wright CV, White MF, Arden KC, and Accili D. The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 links insulin signaling to Pdx1 regulation of pancreatic beta cell growth. J Clin Invest 110: 1839–1847, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein ML, Ferris FL, 3rd, Armstrong J, Hwang TS, Chew EY, Bressler SB, and Chandra SR. Retinal precursors and the development of geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 115: 1026–1031, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klein RJ, Zeiss C, Chew EY, Tsai JY, Sackler RS, Haynes C, Henning AK, Sangiovanni JP, Mane SM, Mayne ST, Bracken MB, Ferris FL, Ott J, Barnstable C, and Hoh J. Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science 308: 385–389, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kunchithapautham K, Atkinson C, and Rohrer B. Smoke exposure causes endoplasmic reticulum stress and lipid accumulation in retinal pigment epithelium through oxidative stress and complement activation. J Biol Chem 289: 14534–14546, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kysenius K. and Huttunen HJ. Stress-induced upregulation of VLDL receptor alters Wnt-signaling in neurons. Exp Cell Res 340: 238–247, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.L'Episcopo F, Tirolo C, Testa N, Caniglia S, Morale MC, Impagnatiello F, Pluchino S, and Marchetti B. Aging-induced Nrf2-ARE pathway disruption in the subventricular zone drives neurogenic impairment in parkinsonian mice via PI3K-Wnt/beta-catenin dysregulation. J Neurosci 33: 1462–1485, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lade A, Ranganathan S, Luo J, and Monga SP. Calpain induces N-terminal truncation of beta-catenin in normal murine liver development: diagnostic implications in hepatoblastomas. J Biol Chem 287: 22789–22798, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lamle J, Marhenke S, Borlak J, von Wasielewski R, Eriksson CJ, Geffers R, Manns MP, Yamamoto M, and Vogel A. Nuclear factor-eythroid 2-related factor 2 prevents alcohol-induced fulminant liver injury. Gastroenterology 134: 1159–1168, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lastres-Becker I, Ulusoy A, Innamorato NG, Sahin G, Rabano A, Kirik D, and Cuadrado A. alpha-Synuclein expression and Nrf2 deficiency cooperate to aggravate protein aggregation, neuronal death and inflammation in early-stage Parkinson's disease. Hum Mol Genet 21: 3173–3192, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee K, Shin Y, Cheng R, Park K, Hu Y, McBride J, He X, Takahashi Y, and Ma JX. Receptor heterodimerization as a novel mechanism for the regulation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. J Cell Sci 127: 4857–4869, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu CC, Tsai CW, Deak F, Rogers J, Penuliar M, Sung YM, Maher JN, Fu Y, Li X, Xu H, Estus S, Hoe HS, Fryer JD, Kanekiyo T, and Bu G. Deficiency in LRP6-mediated Wnt signaling contributes to synaptic abnormalities and amyloid pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 84: 63–77, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu H, Fergusson MM, Castilho RM, Liu J, Cao L, Chen J, Malide D, Rovira II, Schimel D, Kuo CJ, Gutkind JS, Hwang PM, and Finkel T. Augmented Wnt signaling in a mammalian model of accelerated aging. Science 317: 803–806, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mani A, Radhakrishnan J, Wang H, Mani A, Mani MA, Nelson-Williams C, Carew KS, Mane S, Najmabadi H, Wu D, and Lifton RP. LRP6 mutation in a family with early coronary disease and metabolic risk factors. Science 315: 1278–1282, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manolagas SC. and Almeida M. Gone with the Wnts: beta-catenin, T-cell factor, forkhead box O, and oxidative stress in age-dependent diseases of bone, lipid, and glucose metabolism. Mol Endocrinol 21: 2605–2614, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mares-Perlman JA, Brady WE, Klein R, VandenLangenberg GM, Klein BE, and Palta M. Dietary fat and age-related maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 113: 743–748, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mikels AJ. and Nusse R. Purified Wnt5a protein activates or inhibits beta-catenin-TCF signaling depending on receptor context. PLoS Biol 4: e115, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mitter SK, Song C, Qi X, Mao H, Rao H, Akin D, Lewin A, Grant M, Dunn W, Jr., Ding J, Bowes Rickman C, and Boulton M. Dysregulated autophagy in the RPE is associated with increased susceptibility to oxidative stress and AMD. Autophagy 10: 1989–2005, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miyashita K, Kawakami K, Nakada M, Mai W, Shakoori A, Fujisawa H, Hayashi Y, Hamada J, and Minamoto T. Potential therapeutic effect of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta inhibition against human glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res 15: 887–897, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Montalbano M, Curcuru G, Shirafkan A, Vento R, Rastellini C, and Cicalese L. Modeling of hepatocytes proliferation isolated from proximal and distal zones from human hepatocellular carcinoma lesion. PLoS One 11: e0153613, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naito AT, Sumida T, Nomura S, Liu ML, Higo T, Nakagawa A, Okada K, Sakai T, Hashimoto A, Hara Y, Shimizu I, Zhu W, Toko H, Katada A, Akazawa H, Oka T, Lee JK, Minamino T, Nagai T, Walsh K, Kikuchi A, Matsumoto M, Botto M, Shiojima I, and Komuro I. Complement C1q activates canonical Wnt signaling and promotes aging-related phenotypes. Cell 149: 1298–1313, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pajares M, Jimenez-Moreno N, Garcia-Yague AJ, Escoll M, de Ceballos ML, Van Leuven F, Rabano A, Yamamoto M, Rojo AI, and Cuadrado A. Transcription factor NFE2 L2/NRF2 is a regulator of macroautophagy genes. Autophagy 12: 1902–1916, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Palomera-Avalos V, Grinan-Ferre C, Puigoriol-Ilamola D, Camins A, Sanfeliu C, Canudas AM, and Pallas M. Resveratrol protects SAMP8 brain under metabolic stress: focus on mitochondrial function and Wnt pathway. Mol Neurobiol 54: 1661–1676, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parish CL, Castelo-Branco G, Rawal N, Tonnesen J, Sorensen AT, Salto C, Kokaia M, Lindvall O, and Arenas E. Wnt5a-treated midbrain neural stem cells improve dopamine cell replacement therapy in parkinsonian mice. J Clin Invest 118: 149–160, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rada P, Rojo AI, Chowdhry S, McMahon M, Hayes JD, and Cuadrado A. SCF/{beta}-TrCP promotes glycogen synthase kinase 3-dependent degradation of the Nrf2 transcription factor in a Keap1-independent manner. Mol Cell Biol 31: 1121–1133, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rada P, Rojo AI, Offergeld A, Feng GJ, Velasco-Martin JP, Gonzalez-Sancho JM, Valverde AM, Dale T, Regadera J, and Cuadrado A. WNT-3A regulates an Axin1/NRF2 complex that regulates antioxidant metabolism in hepatocytes. Antioxid Redox Signal 22: 555–571, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rozanowska M, Jarvis-Evans J, Korytowski W, Boulton ME, Burke JM, and Sarna T. Blue light-induced reactivity of retinal age pigment. In vitro generation of oxygen-reactive species. J Biol Chem 270: 18825–18830, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rudolf M, Vogt SD, Curcio CA, Huisingh C, McGwin G, Jr., Wagner A, Grisanti S, and Read RW. Histologic basis of variations in retinal pigment epithelium autofluorescence in eyes with geographic atrophy. Ophthalmology 120: 821–828, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tarallo V, Hirano Y, Gelfand BD, Dridi S, Kerur N, Kim Y, Cho WG, Kaneko H, Fowler BJ, Bogdanovich S, Albuquerque RJ, Hauswirth WW, Chiodo VA, Kugel JF, Goodrich JA, Ponicsan SL, Chaudhuri G, Murphy MP, Dunaief JL, Ambati BK, Ogura Y, Yoo JW, Lee DK, Provost P, Hinton DR, Nunez G, Baffi JZ, Kleinman ME, and Ambati J. DICER1 loss and Alu RNA induce age-related macular degeneration via the NLRP3 inflammasome and MyD88. Cell 149: 847–859, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thimmulappa RK, Mai KH, Srisuma S, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, and Biswal S. Identification of Nrf2-regulated genes induced by the chemopreventive agent sulforaphane by oligonucleotide microarray. Cancer Res 62: 5196–5203, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tomany SC, Wang JJ, Van Leeuwen R, Klein R, Mitchell P, Vingerling JR, Klein BE, Smith W, and De Jong PT. Risk factors for incident age-related macular degeneration: pooled findings from 3 continents. Ophthalmology 111: 1280–1287, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tourette C, Farina F, Vazquez-Manrique RP, Orfila AM, Voisin J, Hernandez S, Offner N, Parker JA, Menet S, Kim J, Lyu J, Choi SH, Cormier K, Edgerly CK, Bordiuk OL, Smith K, Louise A, Halford M, Stacker S, Vert JP, Ferrante RJ, Lu W, and Neri C. The Wnt receptor Ryk reduces neuronal and cell survival capacity by repressing FOXO activity during the early phases of mutant huntingtin pathogenicity. PLoS Biol 12: e1001895, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Roon-Mom WM, Pepers BA, ‘t Hoen PA, Verwijmeren CA, den Dunnen JT, Dorsman JC, and van Ommen GB. Mutant huntingtin activates Nrf2-responsive genes and impairs dopamine synthesis in a PC12 model of Huntington's disease. BMC Mol Biol 9: 84, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Verras M, Papandreou I, Lim AL, and Denko NC. Tumor hypoxia blocks Wnt processing and secretion through the induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Cell Biol 28: 7212–7224, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang F, Fisher SA, Zhong J, Wu Y, and Yang P. Superoxide dismutase 1 in vivo ameliorates maternal diabetes mellitus-induced apoptosis and heart defects through restoration of impaired Wnt signaling. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 8: 665–676, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang L, Cano M, Datta S, Wei H, Ebrahimi KB, Gorashi Y, Garlanda C, and Handa JT. PTX3 recruits complement factor H to protect against oxidative stress-induced complement and inflammasome overactivation. J Pathol 240:495–506, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang L, Kondo N, Cano M, Ebrahimi K, Yoshida T, Barnett BP, Biswal S, and Handa JT. Nrf2 signaling modulates cigarette smoke-induced complement activation in retinal pigmented epithelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med 70: 155–166, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang WY, Hsu CC, Wang TY, Li CR, Hou YC, Chu JM, Lee CT, Liu MS, Su JJ, Jian KY, Huang SS, Jiang SS, Shan YS, Lin PW, Shen YY, Lee MT, Chan TS, Chang CC, Chen CH, Chang IS, Lee YL, Chen LT, and Tsai KK. A gene expression signature of epithelial tubulogenesis and a role for ASPM in pancreatic tumor progression. Gastroenterology 145: 1110–1120, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ye X, Zerlanko B, Kennedy A, Banumathy G, Zhang R, and Adams PD. Downregulation of Wnt signaling is a trigger for formation of facultative heterochromatin and onset of cell senescence in primary human cells. Mol Cell 27: 183–196, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yu DH, Zhang X, Wang H, Zhang L, Chen H, Hu M, Dong Z, Zhu G, Qian Z, Fan J, Su X, Xu Y, Zheng L, Dong H, Yin X, Ji Q, and Ji J. The essential role of TNIK gene amplification in gastric cancer growth. Oncogenesis 2: e89, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yu SW, Andrabi SA, Wang H, Kim NS, Poirier GG, Dawson TM, and Dawson VL. Apoptosis-inducing factor mediates poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) polymer-induced cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 18314–18319, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zareparsi S, Branham KE, Li M, Shah S, Klein RJ, Ott J, Hoh J, Abecasis GR, and Swaroop A. Strong association of the Y402H variant in complement factor H at 1q32 with susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Am J Hum Genet 77: 149–153, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhao C, Yasumura D, Li X, Matthes M, Lloyd M, Nielsen G, Ahern K, Snyder M, Bok D, Dunaief JL, LaVail MM, and Vollrath D. mTOR-mediated dedifferentiation of the retinal pigment epithelium initiates photoreceptor degeneration in mice. J Clin Invest 121: 369–383, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhuang B, Luo X, Rao H, Li Q, Shan N, Liu X, and Qi H. Oxidative stress-induced C/EBPbeta inhibits beta-catenin signaling molecule involving in the pathology of preeclampsia. Placenta 36: 839–846, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.