Abstract

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a rapidly expanding treatment for neurological and psychiatric conditions; however, a target-specific biomarker is required to optimize therapy. Here, we show that DBS evokes a large-amplitude resonant neural response focally in the subthalamic nucleus. This response is greatest in the dorsal region (the clinically optimal stimulation target for Parkinson disease), coincides with improved clinical performance, is chronically recordable, and is present under general anesthesia. These features make it a readily utilizable electrophysiological signal that could potentially be used for guiding electrode implantation surgery and tailoring DBS therapy to improve patient outcomes.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is an established therapy that involves surgically implanting electrodes within specific brain structures and delivering electrical pulses to alleviate symptoms.1–3 First approved for essential tremor (ET) and Parkinson disease (PD), its application has expanded to a wide range of neurological and psychiatric disorders, including dystonia, epilepsy, pain, depression, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and addiction.1–4

DBS can be remarkably effective at improving quality of life5; however, a number of clinical challenges can diminish patient outcomes. In particular, positioning errors in implanting the millimeter-sized brain targets can lead to reduced therapeutic efficacy, increased detrimental side effects, and inferior long-term outcomes.6 A robust electrophysiological biomarker recordable from the DBS electrode itself, and focal to the neural target, could improve the accuracy of the surgical procedure and also identify the ideal direction to "steer" stimulation for new generation electrodes.7

Previous research has particularly focused on low-frequency (<100Hz) spontaneous local field potential activity.8,9 In contrast, we investigated whether neural activity evoked by DBS pulses could yield an alternative and more robust biomarker. Recordings were obtained from DBS electrodes implanted in several clinical targets including the subthalamic nucleus (STN) of PD patients and the posterior subthalamic area (PSA) and ventral intermediate nucleus of the thalamus (VIM) of ET patients. A large-amplitude resonant neural response was identified that is localizable to the STN and has the potential to facilitate substantial improvement of DBS therapy.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Subjects were patients undergoing awake DBS implantation surgery. Following ethics approval, 14 PD and 5 ET patients were recruited (Table) in Melbourne, Australia, at St Vincent’s (HREC-D 071/14), St Vincent’s Private (R0236-15), and Austin (SSA/15/Austin/266) hospitals. Informed consent was obtained from all patients, and the study was registered at www.anzctr.org.au (trial # ACTRN12615001368527).

Table. Patient Demographics and Experimental Conditions.

| Subject | Age, yr | Gender | DBS Indication | DBS Target | Hemispheres Tested | Electrode(s) Stimulated | Assessed Postoperatively |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD01 | 60 | M | MF | STN | L, R | E2 (dorsal STN)a | Nob |

| PD02 | 45 | M | MF | STN | L, R | E2 (dorsal STN)a | Nob |

| PD03 | 64 | F | MF | STN | L, R | E2 (dorsal STN)a | Nob |

| PD04 | 63 | M | MF | STN | Lc | E2 (dorsal STN)a | Nob |

| PD05 | 64 | M | MF | STN | L, R | All | Yes |

| PD06 | 73 | F | MF | STN | L, R | All | Yes |

| PD07 | 61 | M | MF | STN | L, R | All | Yes |

| PD08 | 65 | F | MF | STN | L, R | All | Yes |

| PD09 | 54 | M | MF | STN | L, R | All | Yesd |

| PD10 | 55 | F | MF | STN | L, R | All | Yes |

| PD11 | 62 | M | MF | STN | L, R | All | Yes |

| PD12 | 66 | M | MF, T | STN | L, R | All | Yes |

| PD13 | 63 | F | MF, T | STN | L, R | All | Yes |

| PD14 | 53 | M | MF | STN | L, R | All | Yes |

| ET01 | 66 | M | T | PSA/VIM | L, R | E1 (PSA)a,e | No |

| ET02 | 59 | M | T | PSA/VIM | L, R | All | No |

| ET03 | 73 | F | T | PSA/VIM | L, R | All | No |

| ET04 | 74 | F | T | PSA/VIM | L, R | All | No |

| ET05 | 74 | M | T | PSA/VIM | L, R | All | No |

Only 1 electrode stimulated per hemisphere due to experiment piloting.

Not tested as only 1 electrode stimulated intraoperatively.

Only 1 hemisphere tested due to patient fatigue.

Patient retested 560 days postoperatively.

Stimulation amplitude of 2.25mA used instead of 3.38mA.

DBS = deep brain stimulation; ET = essential tremor patient; F = female; L = left; M = male; MF = motor fluctuation; PD = Parkinson disease patient; PSA = posterior subthalamic area; R = right; STN = subthalamic nucleus; T = tremor; VIM = ventral intermediate nucleus.

Surgery

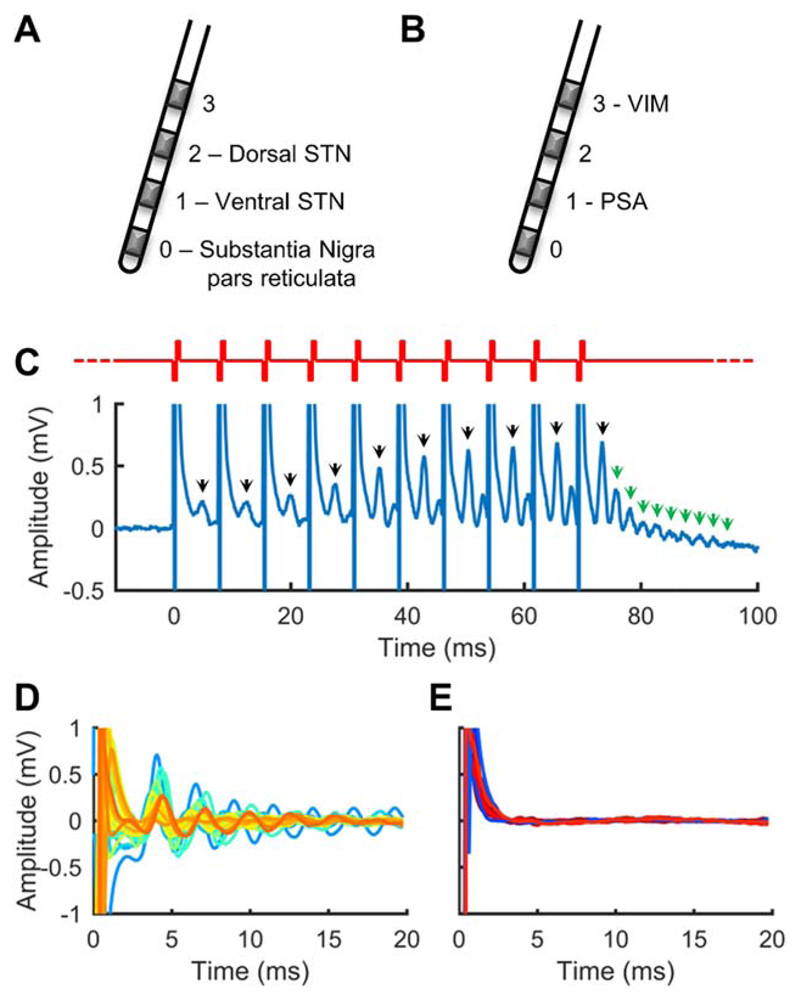

Following the surgical team’s standard clinical practice, electrode arrays (model 3387; Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) were implanted bilaterally using trajectories intended to position electrodes within multiple structures (PD: STN and substantia nigra pars reticulata; ET: PSA and VIM; Fig 1A, B). Targeting was performed using a stereotactic frame (CRW; Integra Lifesciences Corporation, Plainsboro, NJ) and preoperative 3-dimensional volumetric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) fused to a contrast-enhanced stereotactic computed tomography (CT) scan. Microelectrode recordings and therapeutic window assessments were performed to validate trajectories. Before connection to a subclavicular pulse generator (Activa, Medtronic) and with the patient still awake, the implanted electrode arrays were connected to both a biosignal amplifier (g.USBamp; g.tec Medical Engineering, Schiedlberg, Austria) and a highly controllable external neurostimulator10 to conduct experiments.

Figure 1. Subthalamic nucleus region deep brain stimulation evokes resonant neural activity.

(A) Typical Parkinson disease (PD) subthalamic nucleus (STN) target electrode positions. (B) Typical essential tremor posterior subthalamic area (PSA)/ventral intermediate nucleus (VIM) target electrode positions. (C) Resonant neural activity evoked by a burst of stimulation applied to an electrode in the STN of a PD patient. Bursts comprised 10 pulses delivered at 130Hz (red waveform). Black arrows indicate a peak observable between pulses. Green arrows indicate resonant peaks observable at the end of the burst. Recording electrode: E1; stimulated electrode: E2. (D) Evoked responses from 27 STNs (colors represent different nuclei). Recording electrode: E1; stimulated electrode: E2. (E) Evoked responses from 10 PSAs (blue traces; recording electrode: E0; stimulated electrode: E1) and 8 VIMs (red traces; recording electrode: E2; stimulated electrode: E3). Y-axis is as per D.

Experimental Stimulation

Stimulation comprised monopolar symmetric biphasic pulses (3.38mA, 130Hz, 60-microsecond phase, negative first), as used in other DBS evoked response studies,11,12 temporally patterned into bursts of 10 consecutive pulses every second (see Fig 1C). Stimulation was sequentially applied to the electrodes specified in the Table for at least 10 seconds each.

Signal Processing

Neural activity was recorded (fs = 38.4kHz) monopolarly from the same electrode arrays used for stimulation. Recordings were postprocessed using MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) by re-referencing to an average of the 4 electrodes implanted in the other hemisphere, zero-phase forward-reverse filtering (2nd-order Butterworth high-pass [fc = 2Hz] and band-stop [fc = 50Hz] filters), and applying a 21-point moving average. After detrending to remove baseline offsets, evoked response amplitude was characterized as root mean square amplitude over 4 to 20 milliseconds after the last pulse of each stimulus burst and normalized to the sum of response amplitudes across each hemisphere to account for amplitude disparities across patients, likely due to mediolateral and anteroposterior positional variation, underlying physiology, and penetration-related stun effects. Due to stimulation artifacts, very short latency (<1 milliseconds) evoked activity was not investigated. Statistical analyses were performed using Sigma-Plot (Systat Software, San Jose, CA).

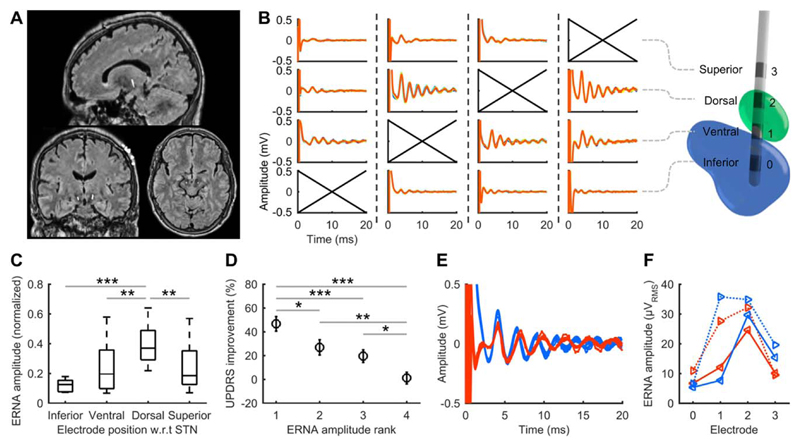

Electrode Localization

As STN architecture cannot be accurately discriminated using standard 3T MRI, and inherent variation in STN size, shape, and orientation precludes atlas-based localization, a reference system was used relative to the readily identifiable red nucleus. Preoperative MRI and postoperative CT scans (Fig 2A) were coregistered (BRAINSFit, 3D Slicer13) and electrode coordinates were visually marked by their artifacts and processed in MATLAB. Research suggests the ideal STN dorsal–ventral location to apply DBS for PD is around 2mm inferior to the superior border of the red nucleus.14 Therefore, electrodes within the region 1mm above to 2mm below the ideal coordinate were classified as dorsal STN and electrodes 2 to 5mm below as ventral STN. Electrodes beyond these regions were classified as superior or inferior to the STN.

Figure 2. Evoked resonant neural activity (ERNA) positional variation, clinical performance and presence under anesthesia.

(A) Example sagittal, coronal, and axial merged magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography scans used to classify electrode positions. The central hyperintense voxels correspond to the implanted electrodes. (B) End-of-burst ERNA resulting from each electrode being stimulated in the right subthalamic nucleus (STN) of 1 subject. A 3-dimensional reconstruction for the same subject (green: STN; blue: substantia nigra) illustrates the electrode positions. Crossed axes indicate the stimulated electrode, with dashed lines separating each stimulation condition. (C) Normalized ERNA amplitude variation with electrode position across Parkinson disease patients in whom all electrodes were stimulated (20 hemispheres; box: 25th–75th percentiles; line: median; whiskers: range; w.r.t: with respect to). (D) Mean Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) improvement from stimulation after ranking electrodes within each hemisphere according to the amplitude of ERNA measured (rank 1: largest ERNA; bars: standard error). Results from 10 PD patients tested post-surgery (20 hemispheres). (E) ERNA recorded in PD09 at electrode implantation (blue) and under general anesthesia 560 days postoperatively (red). (F) ERNA variation across the electrode array at implantation (blue) and 560 days postoperatively (red; solid: left STN; dotted: right STN). *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

Postoperative Clinical Assessments

Ten PD patients (see Table) were assessed at least 3 months postsurgery (range = 103–586 days, mean = 390 days). Motor performance was assessed by a blinded clinician using the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (part III items 20–26). All patients were assessed off-medication after overnight withdrawal, and chronic stimulation was ceased 45 minutes prior to baseline "off-therapy" assessments. Using the implanted pulse generator, standard DBS was then bilaterally applied to each of the 4 electrode positions in counterbalanced order for 30 minutes, with assessments repeated after 15 minutes. Monopolar stimulation was applied using each patient’s chronic amplitude setting (or 10% less if chronic stimulation was bipolar), or 75% or 50% of that level if not tolerated, with the chronically used pulse width and stimulation rate.

General Anesthesia Recording

Due to an infection requiring electrode extension cable replacement, 1 patient (PD09) was able to be retested 560 days postimplantation. General anesthesia was induced using propofol and maintained using remifentanil and isoflurane. The chronically implanted electrode leads were temporarily externalized and burst stimulation was applied to each electrode as described above.

Results

DBS in the vicinity of the STN (STN-DBS) was found to evoke a large-amplitude response with a peak typically ~4 milliseconds after each pulse, which tended to increase in amplitude and sharpen across the consecutive pulses of a burst (see Fig 1C). This peak was found to be the first in a series with progressively decreasing amplitude, resembling a decaying oscillation, so we describe it as evoked resonant neural activity (ERNA).

ERNA of similar morphology was observed in every STN of the PD patients, but not in the PSA of ET patients (see Fig 1D, E). Extremely low amplitude ERNA was observed in 5 of 8 VIMs (see Fig 1E); however, postoperative imaging revealed those electrodes to be located at the STN border.

ERNA amplitude and morphology varied with electrode position relative to the STN (see Fig 2B), with the largest responses and most apparent decaying oscillation morphology typically occurring within the STN. Electrodes classified as being within dorsal STN had significantly higher amplitude ERNA than all other regions (Kruskal–Wallis, H3 = 24.08, p < 0.001; Dunn post hoc test; see Fig 2C).

Postoperative clinical assessments were normalized to off-therapy scores and sorted by ranking the ERNA amplitude measured at each electrode within each hemisphere (see Fig 2D). Therapeutic benefit was significantly higher at electrodes with higher ERNA amplitudes (1-way repeated measures analysis of variance, F3, 78 = 14.302, p < 0.001, Holm–Sidak post hoc test).

Despite chronic electrode implantation and the presence of general anesthesia, ERNA was observed in patient PD09 with comparable amplitude and positional variation to those recorded at implantation (see Fig 2E, F).

Discussion

These results establish that STN-DBS evokes resonant neural activity, a robust and clinically relevant electrophysiological response that is focal to the dorsal subregion where STN-DBS usually produces the greatest benefit for PD.15 ERNA was observed in all 27 PD STNs tested, indicating it is a prominent signal measurable across the patient population, and was absent in all 10 ET PSAs, implying it is a physiological response and not artifactual. Furthermore, as VIM has previously been reported not to elicit evoked activity beyond ~2 milliseconds,11 the extremely low amplitude ERNA observed in some ET patients is likely due to excitation in the vicinity of the STN by electrodes in proximity, suggesting ERNA is not specific to PD. Universal presence, along with the STN’s roles in motor, limbic, and associative function,16 may make ERNA a neuronal response relevant to a number of clinical indications in addition to PD, although PD remains the predominant indication for DBS worldwide.4

The presence of a peak evoked by STN-DBS has been reported previously in 2 PD patients12; however, the full extent and resonant morphology of ERNA is only revealed over a time window longer than that between DBS pulses delivered at a typical rate, as provided by our burst stimulation protocol. The exact mechanism underlying the resonant nature is yet to be established, and it may not necessarily arise from direct activation of the STN itself. The STN is part of the highly interconnected corticobasal ganglia–thalamocortical network that forms multiple feedback loops, providing the components of potentially multiple resonant neural circuits.1,16,17 As such, ERNA may arise from resonant interactions between the STN and other interconnected structures,1,17 such as the globus pallidus18,19 or the cortex, where resonant responses evoked by STN-DBS have previously been observed.20,21 Alternatively, ERNA may arise from periods of inhibition and excitation within the STN itself following each DBS pulse.22

ERNA’s high amplitude, orders of magnitude larger than comparable local field potential signals, and the improved clinical outcomes when stimulating on electrodes exhibiting greater ERNA amplitudes suggest it may have applications as a readily recordable feedback signal for improving DBS therapy; however, further studies are required to determine its specificity and sensitivity as a possible biomarker. ERNA could potentially be used for guiding electrode implantation surgery to the most beneficial sites for stimulation in both awake and anesthetized patients, and for selecting chronic electrode configurations that steer stimulation to the target structure. Although amplitude variation was the most apparent feature, other ERNA properties such as peak frequency, latency, or phase reversal may further prove informative in discriminating STN regions. The sharpening of the first ERNA peak across the individual pulses of each burst also suggests that resonant state is modulated by DBS and therefore ERNA may also have utility as a chronically recordable feedback signal for identifying optimal stimulation parameters, controlling closed-loop therapy, and providing deeper insight into the mechanisms underlying DBS.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Colonial Foundation, St Vincent’s Hospital Research Endowment Fund, and the National Health and Medical Research Council (project grant # 1103238). The Bionics Institute acknowledges the support it receives from the Victorian Government through its operational infrastructure program. N.C.S. is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. S.S.X and W.T. are supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council. W.T. is supported by Lions International. P.B. is supported by the Medical Research Council of Great Britain (MC_UU_12024/1).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

N.C.S., H.J.M., W.T., K.J.B., S.S.X., and T.P. contributed to the conception and design of the study; N.C.S., H.J.M., W.T., K.J.B., S.S.X., T.P., and J.B.F. contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data; all authors contributed to drafting the text.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

Nothing to report.

References

- 1.Montgomery EB., Jr . Deep brain stimulation programming: mechanisms, principles, and practice. Oxford, UK: University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denys D, Feenstra M, Schuurman R. Deep brain stimulation: a new frontier in psychiatry. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Science + Business Media; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDermott H. Neurobionics: the biomedical engineering of neural prostheses. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2016. Neurobionics: treatments for disorders of the central nervous system; pp. 213–230. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pereira EA, Green AL, Nandi D, Aziz TZ. Deep brain stimulation: indications and evidence. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2007;4:591–603. doi: 10.1586/17434440.4.5.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diamond A, Jankovic J. The effect of deep brain stimulation on quality of life in movement disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1188–1193. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.065334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paek SH, Yun JY, Song SW, et al. The clinical impact of precise electrode positioning in STN DBS on three-year outcomes. J Neurol Sci. 2013;327:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Contarino MF, Bour LJ, Verhagen R, et al. Directional steering: a novel approach to deep brain stimulation. Neurology. 2014;83:1163–1169. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Little S, Brown P. What brain signals are suitable for feedback control of deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1265:9–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06650.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Priori A, Foffani G, Rossi L, Marceglia S. Adaptive deep brain stimulation (aDBS) controlled by local field potential oscillations. Exp Neurol. 2013;245:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slater KD, Sinclair NC, Nelson TS, et al. neuroBi: a highly configurable neurostimulator for a retinal prosthesis and other applications. IEEE J Transl Eng Health Med. 2015;3:1–11. doi: 10.1109/JTEHM.2015.2455507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kent AR, Swan BD, Brocker DT, et al. Measurement of evoked potentials during thalamic deep brain stimulation. Brain Stimul. 2015;8:42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gmel GE, Hamilton TJ, Obradovic M, et al. A new biomarker for subthalamic deep brain stimulation for patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease—a pilot study. J Neural Eng. 2015;12:066013. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/12/6/066013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30:1323–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houshmand L, Cummings KS, Chou KL, Patil PG. Evaluating indirect subthalamic nucleus targeting with validated 3-tesla magnetic resonance imaging. Stereot Funct Neurosurg. 2014;92:337–345. doi: 10.1159/000366286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herzog J, Fietzek U, Hamel W, et al. Most effective stimulation site in subthalamic deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2004;19:1050–1054. doi: 10.1002/mds.20056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Temel Y, Blokland A, Steinbusch HW, Visser-Vandewalle V. The functional role of the subthalamic nucleus in cognitive and limbic circuits. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;76:393–413. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montgomery EB., Jr Dynamically coupled, high-frequency reentrant, non-linear oscillators embedded in scale-free basal ganglia-thalamic-cortical networks mediating function and deep brain stimulation effects. Nonlinear Stud. 2004;11(3) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hashimoto T, Elder CM, Okun MS, et al. Stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus changes the firing pattern of pallidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1916–1923. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01916.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foffani G, Priori A. Deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease can mimic the 300 Hz subthalamic rhythm. Brain. 2006;129:e59. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker KB, Montgomery EB, Rezai AR, et al. Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulus evoked potentials: physiological and therapeutic implications. Mov Disord. 2002;17:969–983. doi: 10.1002/mds.10206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eusebio A, Pogosyan A, Wang S, et al. Resonance in subthalamo-cortical circuits in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2009;132:2139–2150. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meissner W, Leblois A, Hansel D, et al. Subthalamic high frequency stimulation resets subthalamic firing and reduces abnormal oscillations. Brain. 2005;128:2372–2382. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]