Abstract

Recognition of Nod factors by LysM receptors is crucial for nitrogen-fixing symbiosis in most legumes. The large families of LysM receptors in legumes suggest concerted functions, yet only NFR1 and NFR5 and their closest homologs are known to be required. Here we show that an epidermal LysM receptor (NFRe), ensures robust signalling in L. japonicus. Mutants of Nfre react to Nod factors with increased calcium spiking interval, reduced transcriptional response and fewer nodules in the presence of rhizobia. NFRe has an active kinase capable of phosphorylating NFR5, which in turn, controls NFRe downstream signalling. Our findings provide evidence for a more complex Nod factor signalling mechanism than previously anticipated. The spatio-temporal interplay between Nfre and Nfr1, and their divergent signalling through distinct kinases suggests the presence of an NFRe-mediated idling state keeping the epidermal cells of the expanding root system attuned to rhizobia.

Research organism: Other

eLife digest

Microbes – whether beneficial or harmful – play an important role in all organisms, including plants. The ability to monitor the surrounding microbes is therefore crucial for the survival of a species. For example, the roots of a soil-growing plant are surrounded by a microbial-rich environment and have therefore evolved sophisticated surveillance mechanisms.

Unlike most other plants, legumes, such as beans, peas or lentils, are capable of growing in nitrogen-poor soils with the help of microbes. In a mutually beneficial process called root nodule symbiosis, legumes form a new organ called the nodule, where specific soil bacteria called rhizobia are hosted. Inside the nodule, rhizobia convert atmospheric dinitrogen into ammonium and provide it to the plant, which in turn supplies the bacteria with carbon resources.

The interaction between the legume plants and rhizobia is very selective. Previous research has shown that plants are able to identify specific signaling molecules produced by these bacteria. One signal in particular, called the Nod factor, is crucial for establishing the relationship between these two organisms. To do so, the legumes use specific receptor proteins that can recognize the Nod factor molecules produced by bacteria. Two well-known Nod factor receptors, NFR1 and NFR5, belong to a large family of proteins, which suggests that other similar receptors may be involved in Nod factor signaling as well.

Now, Murakami et al. identified the role of another receptor called NRFe by studying the legume species Lotus japonicus. The results showed that NFRe and NFR1 share distinct biochemical and molecular properties. NRFe is primarily active in the cells located in a specific area on the surface of the roots. Unlike NFR1, however, NFRe has a restricted signaling capacity limited to the outer root cell layer. Murakami et al. found that when NRFe was mutated, the Nod factor signaling inside the root was less activated and fewer nodules formed, suggesting NRFe plays an important role in this symbiosis.

NFR1-type receptors have also been found in plants outside legumes, which do not form a symbiotic relationship with rhizobia. Identifying more receptors important for Nod-factor signaling could provide a basis for new biotechnological targets in non-symbiotic crops, to improve their growth in nutrient-poor conditions.

Introduction

Perception of Nod factors by LysM receptor kinases, NFR1 and NFR5 in Lotus japonicus (Broghammer et al., 2012), triggers tightly coordinated events leading to root nodule symbiosis (Madsen et al., 2003; Radutoiu et al., 2003). Minutes after the activation of receptors, a signalling cascade (Stracke et al., 2002; Antolín-Llovera et al., 2014) leading to regular calcium oscillations in the root hair cells located in the susceptible zone is initiated (Miwa et al., 2006). These oscillations are interpreted by the Calcium Calmodulin Kinase (CCaMK) (Miller et al., 2013), which activates a set of regulators that launch transcription of symbiosis specific genes in the outer root cell layers (Yano et al., 2008; Hirsch et al., 2009). Progression of the symbiotic signalling events from epidermis into the cortex is necessary for nodule organogenesis and infection thread formation. NIN, a transcriptional regulator, and cytokinin signalling have been implicated in this epidermal to cortex signalling (Murray et al., 2007; Tirichine et al., 2007; Vernié et al., 2015).

Mutations in Nfr5 and its homologs in pea and M. truncatula eliminate all Nod factor-induced physiological, molecular and cellular responses (Madsen et al., 2003; Arrighi et al., 2006). However, some or several of these responses are retained in the Ljnfr1, Mtlyk3 and Pssym37 mutants (Radutoiu et al., 2003; Smit et al., 2007; Zhukov et al., 2008) raising the possibility that modular receptor complex formation regulated in a spatio-temporal manner might contribute to Nod factor signalling. The LysM receptor kinase family has greatly expanded in legumes through whole genome or tandem duplications (Zhang et al., 2009; Lohmann et al., 2010; Kelly et al., 2017). In L. japonicus, four genes, Lys1, Lys2, Lys6 and Lys7, are closely related to Nfr1. Lys1 and Lys2 are located in tandem and at ~10 kb distance from Nfr1 (Lohmann et al., 2010). Interestingly, a similar chromosomal organisation of NFR1-type receptors was reported in all studied legumes, as well as in genomes outside of Leguminosae clade raising the possibility that gene duplication leading to tandem NFR1-type receptors preceded the evolution of the legume family (De Mita et al., 2014). The precise role of these NFR1 paralogs and their homologs is unknown apart from the chitin receptors L. japonicus LYS6 (now CERK6) and Medicago truncatula LYK9 (Bozsoki et al., 2017). Nonetheless, key details about the signalling competencies of LYS2, LYS6 and LYS7 were obtained from functional complementation analyses in the nfr1 mutant using the LjUbiquitin promoter. Only the intracellular kinase regions of LYS6 and LYS7, but not that of LYS2, could restore nodulation and/or infection when coupled to the NFR1 Nod factor-binding domain (Nakagawa et al., 2011).

Here, we show that LYS1 is an epidermal LysM receptor contributing to the NFR1-NFR5 mediated signalling in a spatio-temporal manner. This gene is primarily expressed in epidermal cells of the susceptible zone where roots are competent for initiation of symbiosis, and has a restricted signalling capacity leading to Nin activation in the outer root cell layers. Our findings provide evidence for a complex Nod factor signalling where LYS1 activity in the outer root cell layers aids in maintaining a normal calcium spiking interval in the root hairs, integral transcript responses in the susceptible root zone, and initiation of nodule primordia on the expanding root system. The Lys1 gene is therefore renamed Nfre, in accordance with the identified role of this gene during Nod factor signalling in the epidermal layer.

Results

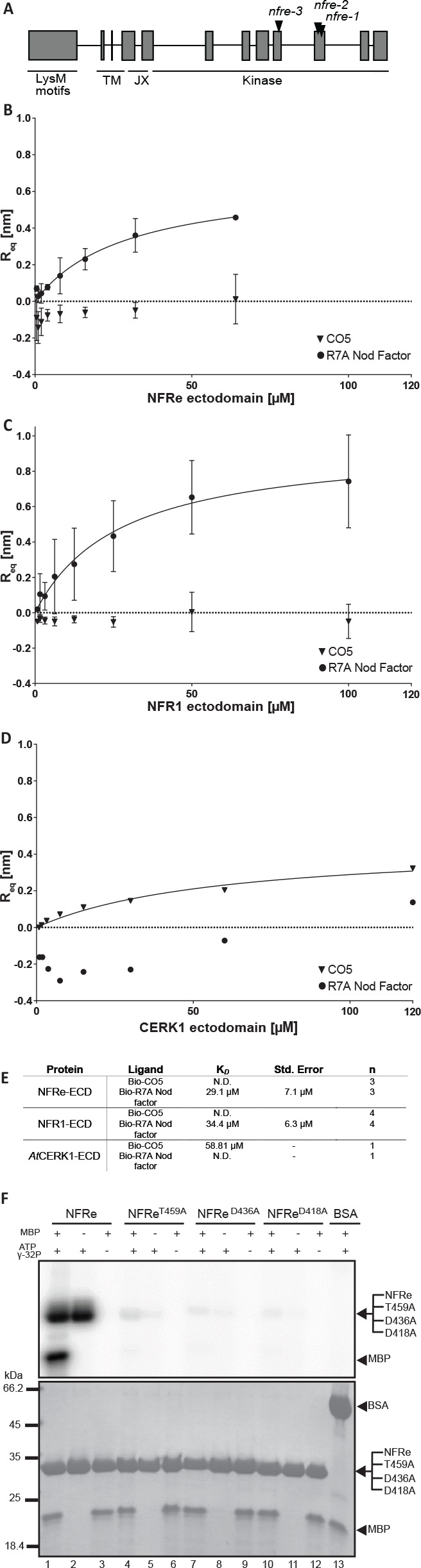

NFRe perceives Nod factor and has an active intracellular kinase

NFRe is predicted to encode a LysM receptor protein with a typical intracellular kinase domain (Figure 1A, Figure 1—figure supplement 1). Based on the close similarity to NFR1 we investigated its biochemical and molecular properties. For this, we analysed the binding capacity of NFRe towards purified pentameric M. loti R7A Nod factor ligand (Bek et al., 2010). The NFRe ectodomain was expressed in insect cells using a recombinant baculovirus induced-expression system (Kawaharada et al., 2015). Pure protein was obtained after four steps of purification and the homogeneity was confirmed by size exclusion chromatography (Figure 1—figure supplement 2). Biolayer interferometry (BLI) (Kawaharada et al., 2015) was used for receptor-ligand affinity measurements since this technique is well suited for handling sparingly soluble hydrophobic compounds like Nod factor. To enable ligand immobilization on streptavidin biosensors M. loti R7A Nod factor and chitin pentamer ((GlcNAc)5, CO5) were conjugated to a biotinylated linker using N-glycosyl oxyamine chemistry (Bohorov et al., 2006; Villadsen et al., 2017) (Figure 1—figure supplement 3). Affinity measurements showed that the ectodomain of NFRe has the capacity to bind M. loti Nod factor with an equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) of 29.1 ± 7.1 μM (Figure 1B,E). Next, we tested whether NFRe has the capacity to bind chitin but no signal was observed for CO5 ligands in this system (Figure 1B). To test our immobilised ligands, we performed the same binding experiment with purified NFR1 ectodomain (Figure 1—figure supplement 2), which gave a KD of 34 ± 6.3 μM to M. loti R7A Nod factor and no binding to CO5 (Figure 1C,E). As a positive control for our chitin ligand we additionally expressed and purified the Arabidopsis CERK1 ectodomain (Figure 1—figure supplement 2) and measured an affinity of 59 μM to the immobilized CO5 (Figure 1D,E), which is very similar to the previously reported KD of 66 μM measured by isothermal titration calorimetry (Liu et al., 2012). In short, our binding studies show that NFRe has the capacity to perceive Nod factor with comparable affinity as seen for the NFR1 and both receptor ectodomains distinguish Nod factor from pentameric chitin ligands in a BLI binding assay (Figure 1E). NFRe is a challenging and low expressed protein and further biochemical ligand competition studies are required to fully define the specificity and receptor capacity of NFRe.

Figure 1. NFRe perceives Nod factor and has an active intracellular kinase.

(A) The structure of Nfre gene (4663 bp) and predicted protein domains (600 aminoacids). The boxes indicate coding regions, lines are introns, and the location of mutations in the three alleles is indicated. The underlines indicate domains in NFRe; LysM domains, TM: transmembrane, JX: juxtamembrane, kinase. (B), (C) and (D) are binding curves obtained from the biolayer interferometry measurements of NFRe ectodomain, NFR1 ectodomain and AtCERK1 ectodomain interaction with two different ligands, R7A Nod factor and GlcNAc5. Both NFRe and NFR1 ectodomain do not bind to GlcNAc5 but show binding to R7A Nod factor. AtCERK1 ectodomain does not bind R7A Nod factor but binds GlcNAc5. (E) Binding constants of NFRe, NFR1 and AtCERK1 ectodomain to GlcNAc5 and R7A Nod factor obtained from biolayer interferometry steady state-analysis. (F) Nfre encodes an active kinase domain. Autophosphorylation and protein kinase activities of wild-type NFRe, T459A, D436A, D418A NFRe mutant versions, and bovine serum albumin as control are shown. Myelin basic protein was used as substrate for kinase activities. Autoradiogram (top), and SDS-PAGE gels (bottom) are shown. KD, Std. Error and n represent the dissociation constant, standard deviation and number of biological replicates used for the analysis. N.D. represents not detectable.

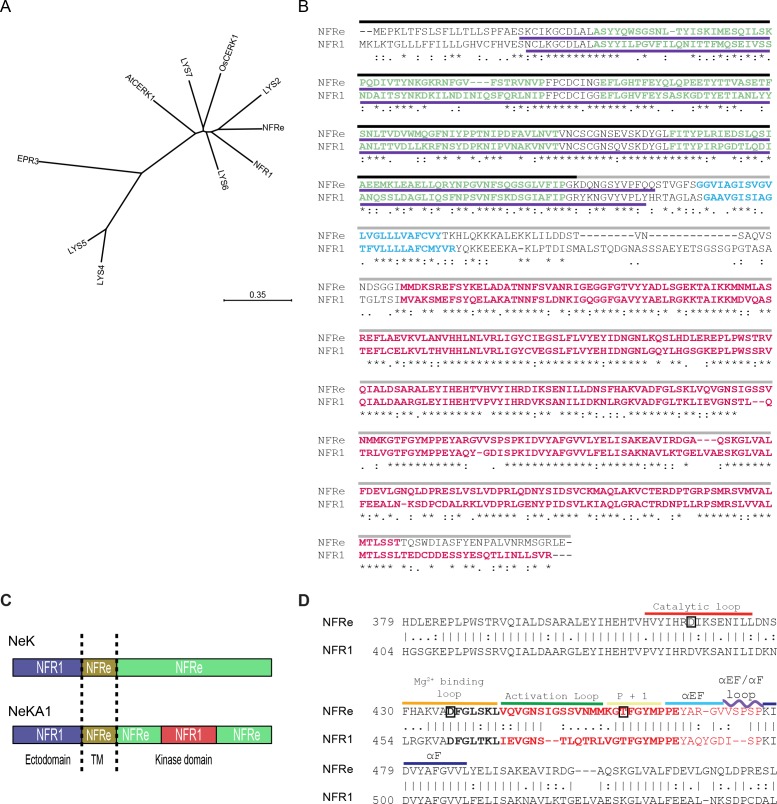

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. NFRe is an NFR1 type LysM receptor.

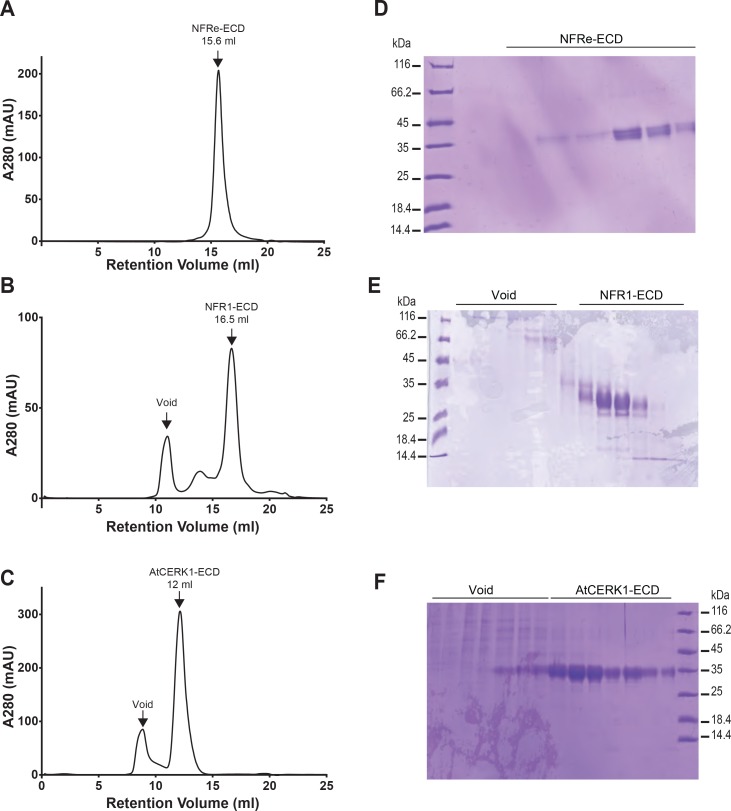

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. Purification of NFRe, NFR1 and AtCERK1 ectodomains.

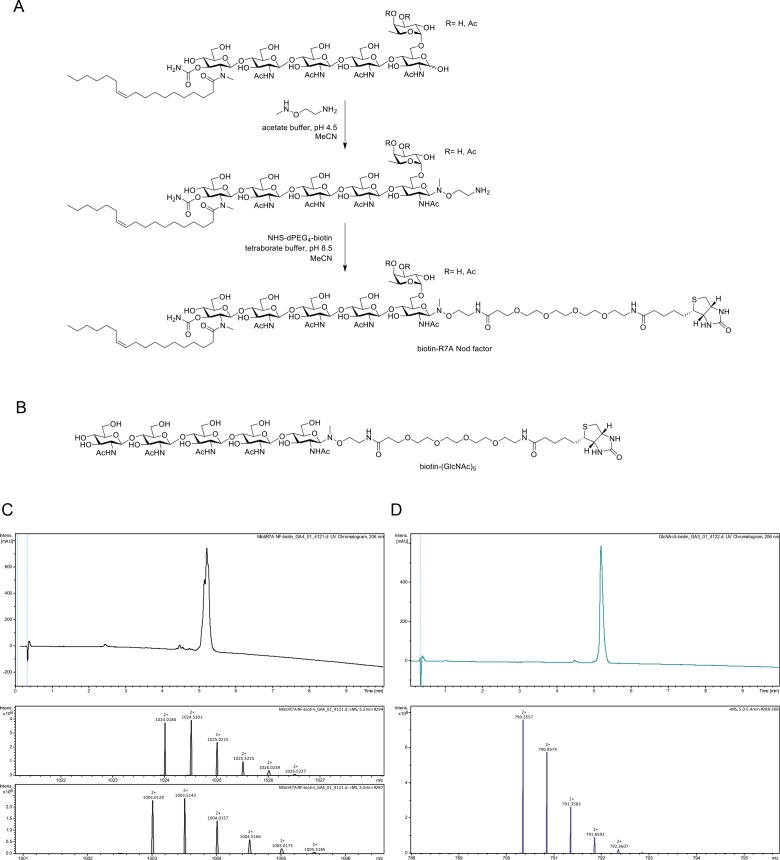

Figure 1—figure supplement 3. Chemoselective synthesis of biotinylated R7A Nod factor and chitin pentamer conjugates.

Next, we assessed the activity of the intracellular kinase domain of NFRe (Figure 1—figure supplement 1). E. coli-produced NFRe kinase transphosphorylated the myelin basic protein (MBP) substrate and autophosphorylated (Figure 1F, lanes 1–3), showing that NFRe encodes a protein kinase with in vitro activity similar to NFR1 (Madsen et al., 2011). Alanine substitutions of three critical amino acids from the catalytic loop (D418), Mg2 +binding loop (D436), or P+1 loop (T459) abolished the phosphorylation activity of NFRe (Figure 1F, lanes 4–12) showing that conserved residues from NFRe kinase are critical for its biochemical activity. Together, our results from biochemical studies demonstrate that Nfre encodes a LysM receptor kinase that can perceive Nod factor and has an active kinase.

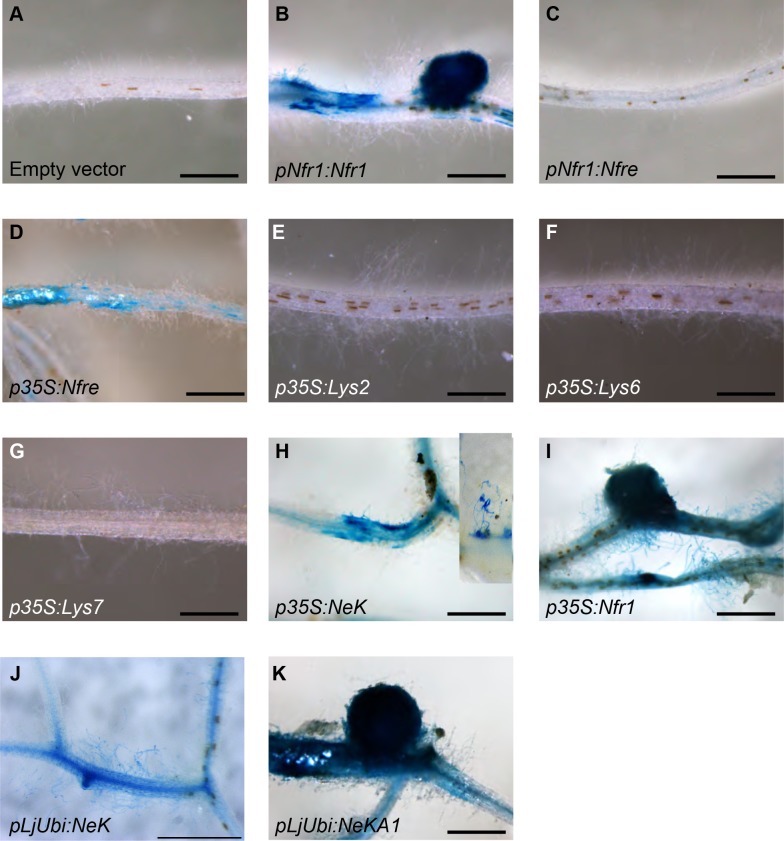

NFRe induces epidermal Nin expression

Since we now know that NFRe is an active LysM receptor with properties comparable to NFR1 in these in vitro assays, we next investigated the signalling capacities of NFRe compared to NFR1 in Lotus roots. We tested this by expressing NFRe in the nfr1-1 mutant line containing the symbiotic Nin:GUS reporter (Radutoiu et al., 2003). Activation of the Nin promoter in Nfre transformed roots of nfr1-1-Nin:GUS plants, or the development of nodule and/or infection threads would indicate activation of symbiotic signalling. While nfr1-1 roots transformed with the Nfr1 gene developed bona fide root nodules and induced Nin promoter, those transformed with the empty vector, and thus expressing the native Nfre gene did not show any responses to inoculation with rhizobia (Table 1 and Figure 2—figure supplement 1). These results indicate that Nfre, in its native status cannot replace the functions of NFR1. On the other hand, p35S-Nfre led to strong activation of the Nin promoter after inoculation with M. loti (Figure 2A and Figure 2—figure supplement 1). This symbiotic induction was however, only detected in the outer root layers (Figure 2A), and it was not followed by formation of nodules or infection threads even after 5 weeks of exposure to M. loti (Figure 2—figure supplement 1). This differed from the p35S-Nfr1-mediated signalling that induced Nin expression in both epidermal and cortical cells (Figure 2B) and led to formation of infected nodules (Figure 2—figure supplement 1). To understand whether this particular and cell layer specific activation of Nin by NFRe is a result of the expression of any LysM receptor of the NFR1-type, or specific to NFRe, Nin activation was assayed in nfr1-1-Nin:GUS plants transformed with the Lys paralogs of NFR1 (Lohmann et al., 2010). Under similar conditions, Lys2, Cerk6 or Lys7 driven by 35S promoter could not activate the Nin promoter, or induce nodule or infection thread formation in the nfr1-1 mutant. (Table 1 and Figure 2—figure supplement 1). These results demonstrate that in the presence of M. loti, NFRe, like NFR1, can initiate a symbiotic signalling cascade leading to Nin induction in Lotus roots, and that the cellular effects of this signalling are receptor-, and expression-dependent.

Table 1. Nfre expression from p35S promoter activates Nin induction in the nfr1-1-Nin:GUS plants.

| Construct (plants analysed) |

No. of plants Nin positive |

% of plants with Nin induction |

No. of nodulated plants |

% of nodulated plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empty vector (28) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| pNfr1:Nfre (21) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| p35S:Nfre (58) | 28 | 48 | 0 | 0 |

| p35S:Nfre_T459A (21) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| pNfr1:Nfr1 (19) | 19 | 100 | 19 | 100 |

| p35S:Nfr1 (26) | 25 | 96 | 25 | 96 |

| p35S:Lys2 (14) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| p35S:Lys6 (34) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| p35S:Lys7 (34) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

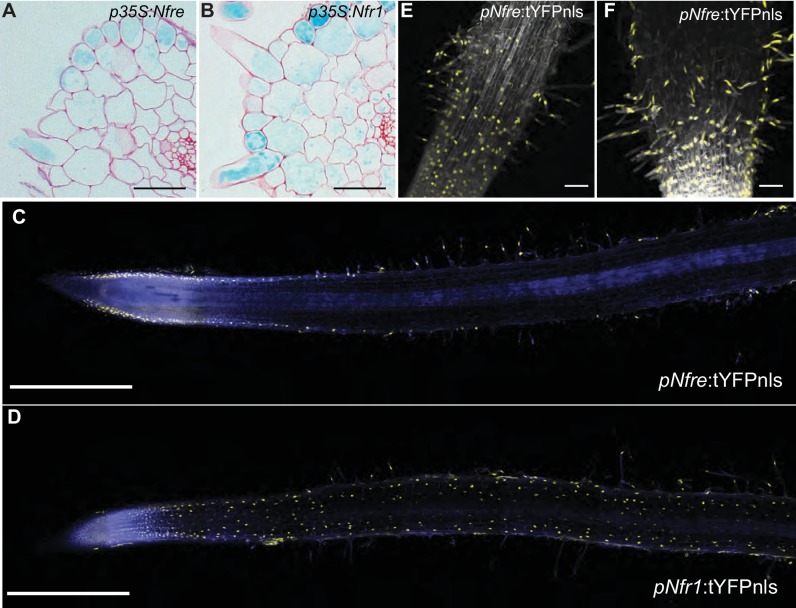

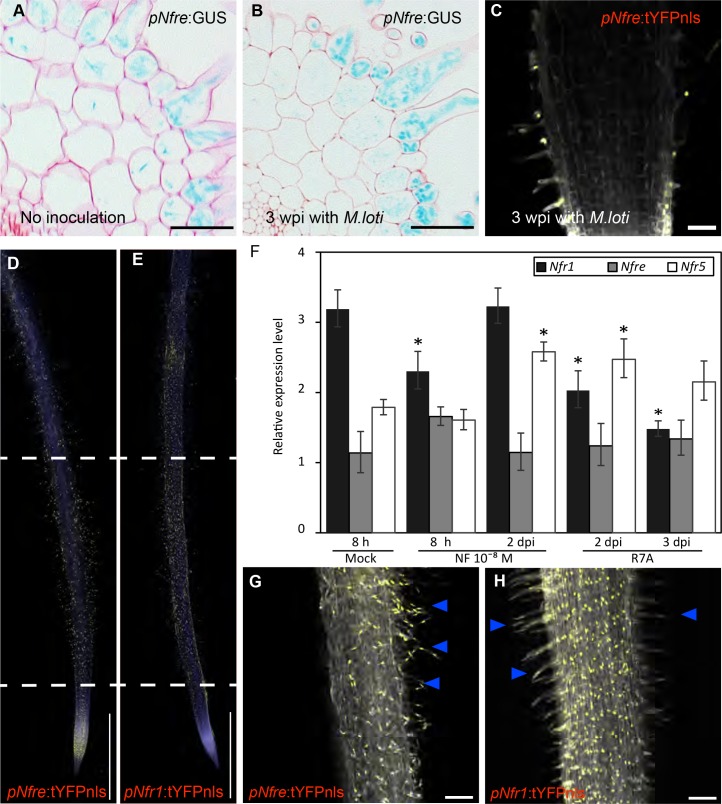

Figure 2. NFRe maintains a low, epidermal expression during root nodule symbiosis.

(A) Transversal root section of nfr1-1-Nin:GUS plants expressing p35S-Nfre shows activation of Nin promoter in the outer cell layer after M. loti inoculation. (B) Transversal root section of nfr1-1-Nin:GUS plants expressing p35S-Nfr1 shows activation of Nin promoter in all cell layers after M. loti inoculation. (C) The epidermal cells, primarily localized in the root susceptible zone, show activity of the Nfre promoter visualized by the nuclear localized triple YFP protein (tYFPnls). (D) Widespread activity of the Nfr1 promoter in the uninoculated root visualized by nuclear localized triple YFP protein (tYFPnls). (E) The expression of Nfre in the susceptible zone of the root, and in the root hairs is maintained after inoculation with M. loti (F). Scale bars, 40 μm (A, B), 0.5 mm (C, D), and 50 μm (E, F).

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Nin:GUS activation in nfr1-1-Nin:GUS plants expressing different receptor variants.

Figure 2—figure supplement 2. Expression patterns of LysM receptors in Lotus japonicus.

NFRe maintains a low, epidermal expression during root nodule symbiosis

Previous studies based on transcript measurement showed that Nfre is expressed in Lotus roots (Lohmann et al., 2010). However, our results from the nfr1-1 complementation studies revealed that expression of Nfre from p35S promoter is needed to induce observable Nin activation after rhizobia inoculation (Figure 2—figure supplement 1). To further understand the cause of this differential signalling we characterised the spatio-temporal regulation of Nfre in detail using GUS and tYFPnls (triple YFP-nuclear localised) reporter fusions, and measured the levels of Nfre transcript by quantitative RT-PCR. In uninoculated roots the Nfre promoter (2,6 kb) was preferentially active in root hair epidermal cells, in the susceptible zone of the root, and in the root tip (Figure 2C,E, and Figure 2—figure supplement 2). This differed from Nfr1 that is expressed in the whole uninoculated root (Radutoiu et al., 2003; Kawaharada et al., 2017) (Figure 2D). The expression pattern of Nfre did not change after inoculation with M. loti (Figure 2F and Figure 2—figure supplement 2), indicating that, unlike Nfr1 (Radutoiu et al., 2003; Kawaharada et al., 2017) and Figure 2—figure supplement 2), the expression of Nfre is not symbiotically regulated. Analyses of Nfre transcript levels in wild type roots either treated with Nod factor or inoculated with M. loti compared to control roots, further confirmed the unaltered expression observed from Nfre promoter studies (Figure 2—figure supplement 2). Direct comparison of Nfr1 and Nfre transcript levels in uninoculated wild type roots showed a 3-fold higher level for Nfr1. Interestingly this difference was reduced significantly after Nod factor treatment (8 hr post treatment) or M. loti inoculation (2 and 3 dpi post inoculation), where Nfr1 expression was down regulated, while Nfre maintained a low, but constant level (Figure 2—figure supplement 2). In summary, Nfre and Nfr1 differ in their expression level and pattern in uninoculated roots, and follow a differential regulation during root nodule symbiosis. These differences could therefore, at least in part, account for the differential signalling capacities of the two LysM receptors.

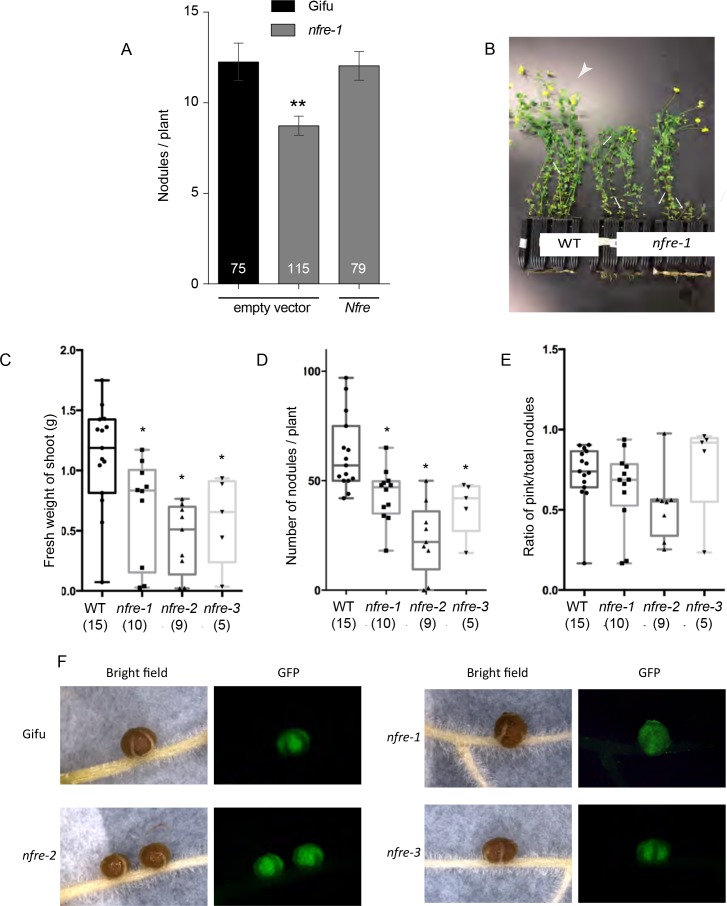

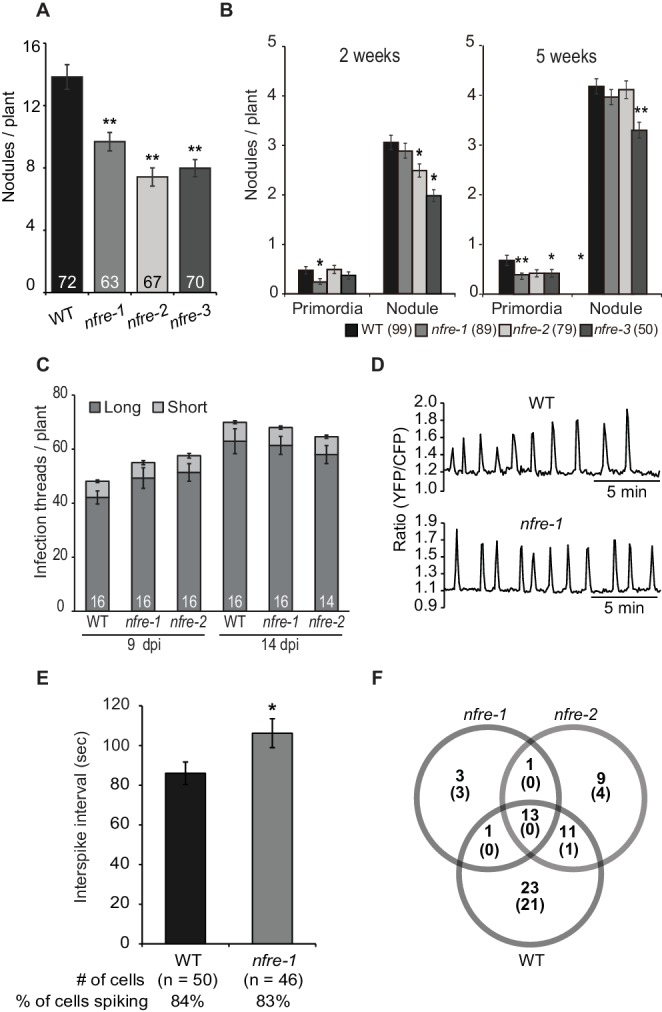

NFRe promotes nodule organogenesis

NFRe has the capacity to bind Nod factors in vitro (Figure 1B) and to induce a symbiotic signalling in planta when expressed in the nfr1-1 mutant from the 35S promoter (Figure 2A). This prompted us to ask whether NFRe plays a role in root nodule symbiosis. Homozygous mutant plants from three independent alleles with exonic insertion of LORE1 retroelement (Mun et al., 2016) (Figure 1A and Supplementary file 1) formed significantly fewer nodules compared to wild type when grown in a binary association with M. loti (Figure 3A). The contribution of NFRe to root nodule organogenesis became even more evident when wild type and nfre mutants were grown in soil and were exposed to the native bacterial community. After 9 weeks, nfre mutants developed only half the number of wild type nodules (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). The shoot biomass and the general plant fitness were significantly reduced (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). Wild type plants had well-developed green pods, while nfre mutants had only few open flowers (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). Analyses of the dynamics of nodule primordia formation on plate-grown plants, revealed that nfre mutants, besides a noticeable reduced nodulation at the early time point (two wpi), had a significantly lower ability to reinitiate nodule formation on the expanding root system (five wpi) (Figure 3B). Unlike nodule organogenesis, the formation of infection threads (IT) appeared not to be affected by mutations in the Nfre. A similar number of ITs were present in wild type and nfre root hairs at 9 or 14 dpi (Figure 3C). The mature nodules formed on nfre appeared normally infected (Figure 3—figure supplement 1), and the proportion of pink/total nodules formed by soil-grown wild type and nfre plants was similar (Figure 3—figure supplement 1), indicating a normal infection process in the nfre mutants.

Figure 3. NFRe promotes nodule organogenesis in Lotus japonicus.

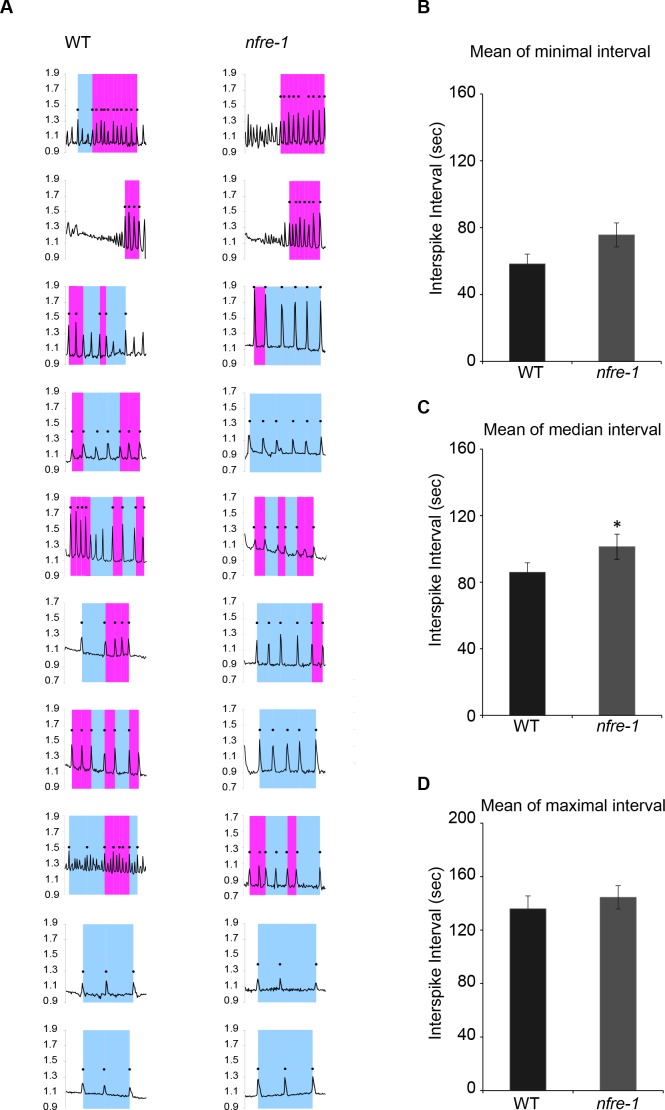

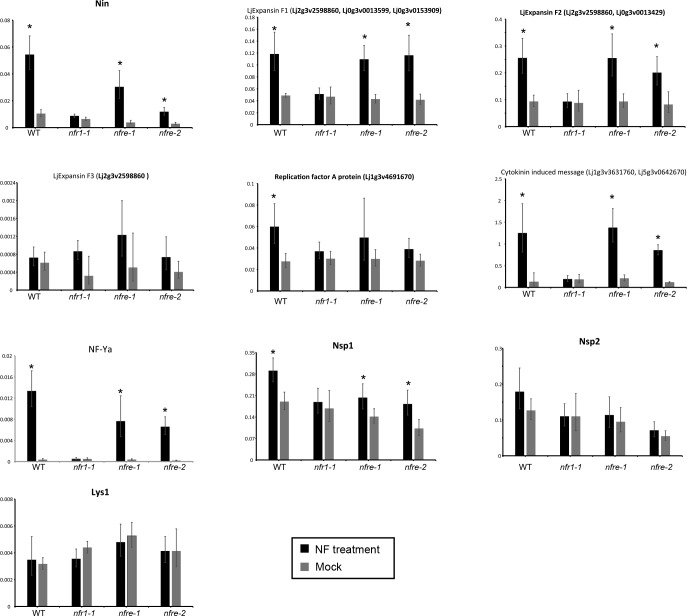

(A) Greenhouse-grown nfre plants formed fewer root nodules compared to WT when analysed at eight wpi with M. loti. (B) Agar plate-grown nfre plants form fewer primordia than WT at 5 wpi with M. loti. (C) The nfre mutants and wild type plants form similar number of short and long root hair infection threads at 9 and 14 dpi. (D) Representative nuclear calcium oscillations (spiking) induced by R7A Nod factor (10–8 M) in wild type and nfre mutant root hairs. Ca2+ oscillations are presented as ratiometric values between YFP and CFP signals detected on the basis of the NLS-YC3.6 Ca2+sensor. (E) The inter-spike interval of nfre-1 mutant is significantly longer than that of WT. (F) Venn diagrams of Nod factor up- and down-regulated (parentheses) genes detected in the susceptible zone at 24 hr after treatment. The values given at the bottom of columns in (A) and (C) represents the number of plants analysed. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01, Student´s t-test compared to wild type.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. The phenotype of wild-type and nfre plants.

Figure 3—figure supplement 2. Pattern of nuclear calcium oscillations in wild-type and nfre-1 mutant.

Figure 3—figure supplement 3. Transcript levels of selected genes measured by quantitative RT-PCR in Mock, or Nod factor-treated wild type, nfr1-1 and nfre mutant roots.

Figure 3—figure supplement 4. Chitin oligomers elicit production of similar ROS levels in nfre and wild type roots.

To further investigate the role of NFRe in Nod factor signalling we analysed its requirement for induction and maintenance of nuclear-associated calcium oscillations (spiking) after Nod factor treatment. Root hairs of wild type (n = 50) and nfre-1 (n = 46) stable transgenics expressing the nuclear localised YC3.6 (Yellow Cameleon) showed clear signs of calcium oscillations after M. loti Nod factor treatment (Figure 3D) (app. 80% of the analysed cells responded). Closer inspection of the spiking frequency revealed that the average inter-spike interval was significantly longer in the nfre cells (106 s) compared to wild type (86 s), indicating that NFRe contributes to a constant interval length of calcium oscillations (Figure 3—figure supplement 2).

Next, we used RNA sequencing to investigate the requirement for Nfre in the transcriptional changes induced by M. loti Nod factor in the susceptible zone of the root at 24 hr after treatment. Genes that were differentially expressed (DEGs adjusted p<0.05) (Materials and methods) in Nod factor treated roots compared to water control were identified in wild type, nfre-1 and nfre-2 mutants. A large proportion of these (44 out of 90), which includes Nin, expansins, nodulins, receptors, transporters and transcription factors, were regulated by Nod factor in wild type but not in the nfre roots, indicating that their appropriate regulation in the susceptible zone, at 24 hr after Nod factor treatment is dependent on an active NFRe (Figure 3—figure supplement 3 and Supplementary file 2). Other symbiosis-related genes like NFY-A, subtilase, and two genes encoding the cytokinin-induced message were found among the 13 DEGs in wild type and nfre mutants. Only one gene (an expansin) was found regulated by the Nod factor in both nfre mutants but not in wild type.

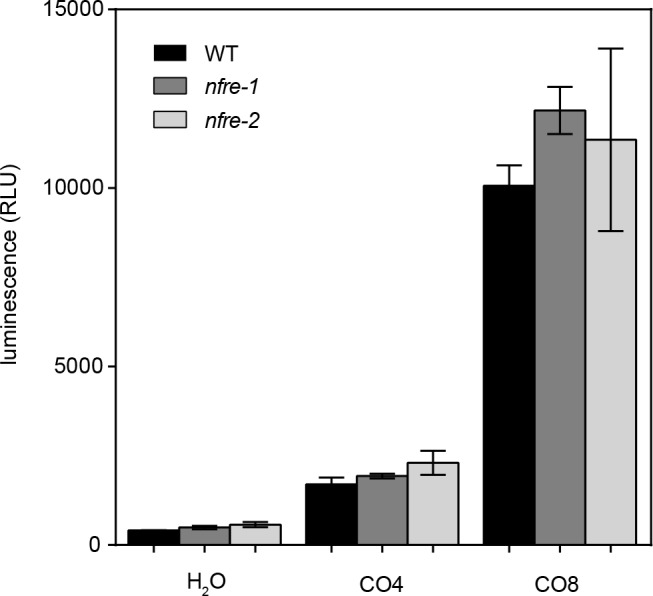

Our biochemical in vitro data based on BLI measurements shows that the NFRe ectodomain does not bind chitopentaose, suggesting that NFRe might not be involved in chitin signalling. To test this hypothesis in planta we measured the induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in response to CO8 or CO4 in the nfre mutants and wild type. We found that wild type, nfre-1 and nfre-2 mutants produced comparable levels of ROS, indicating that NFRe is unlikely to be involved in chitin signalling (Figure 3—figure supplement 4).

Together, these results show that NFRe represents an influential component of the epidermal Nod factor signalling in L. japonicus, promoting intracellular signalling that leads to optimal calcium spiking, activation of gene transcription and efficient nodule organogenesis on the expanding root system.

The activation segments of NFR1 and NFRe determine the signalling output

The clear difference observed between NFR1 and NFRe in their ability to induce Nod factor signalling and spatial activation of the Nin promoter in M. loti inoculated nfr1-1-Nin:GUS roots prompted us to identify the molecular determinants for this differential regulation. A chimeric receptor (NeK) containing the NFR1 extracellular domain followed by the transmembrane and intracellular kinase regions of NFRe (NFR1 ectodomain-NFRe kinase- NeK) (Figure 1—figure supplement 1) was constructed. This receptor was expressed in nfr1-1-Nin:GUS to test its capacity to induce activation of Nin promoter after M. loti inoculation. We observed that the signalling capacity of NeK receptor was similar to that of the NFRe, namely only epidermal induction of the Nin promoter (Table 2 and Figure 2—figure supplement 1). This provides evidence for the presence of a molecular determinant for specific Nin induction in the intracellular regions of NFR1 and NFRe receptors. Alignment of the two kinases identified several divergent regions (Figure 1—figure supplement 1), but clear differences were found in the activation segment (Figure 1—figure supplement 1). Based on these differences, and previous knowledge (Nakagawa et al., 2011) that this region is crucial for kinase signalling and substrate recognition, we hypothesised that a specific NFR1/NFRe activation segment determines the specificity of the downstream signalling. We tested this hypothesis by swapping the NFRe activation segment with the corresponding region of NFR1 in the NeK receptor (NFR1 ectodomain-NFRe kinase with the Activation segment of NFR1 -NeKA1) (Figure 1—figure supplement 1). In contrast to the NeK receptor that induced Nin in the outer root cell layers of the nfr1-1 mutant, NeKA1 led to cortical activation of Nin and nodule formation (Table 2 and Figure 2—figure supplement 1).

Table 2. The intracellular domains of NFRe and NFR1 kinases determine the signalling output.

| Construct (plants analysed) |

No. of plants Nin positive |

% of plants with Nin induction |

No. of nodulated plants |

% of nodulated plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p35S:NeK (29) | 3 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| pLjUbi:NeK (40) | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| pLjUbi:NeKA1 (40) | 26 | 65 | 14 | 35 |

| pLjUbi:Nfr1 (22) | 22 | 100 | 21 | 95 |

These results show that the activation segment in NFR1 and NFRe determines the downstream signalling output in Lotus roots after M. loti inoculation.

NFRe signalling is dependent of NFR5

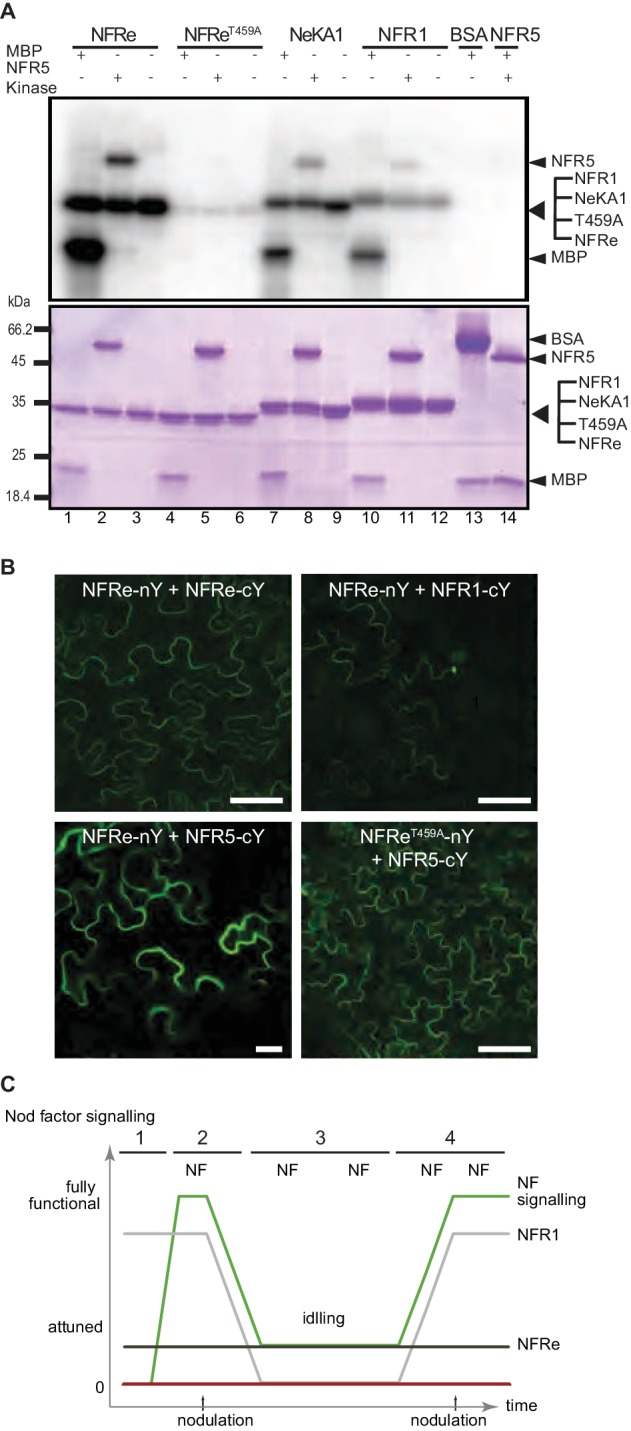

Genetic and molecular studies established that a concerted NFR1-NFR5 signalling induces the nitrogen-fixing symbiosis (Radutoiu et al., 2003; 2007). Here, we present evidence that in L. japonicus NFRe assists the development of root nodule symbiosis. Therefore, we hypothesised that NFRe-dependent signalling also involves NFR5. For this, we investigated the biochemical capacity of the NFRe kinase to transphosphorylate the intracellular NFR5 pseudokinase. The in vitro kinase assays showed that NFR5 is a substrate for the NFRe kinase. (Figure 4A, lanes 1–3) and that this transphosphorylation was dependent on the activation segment of the NFRe kinase. Mutation of T459 to A abolished the kinase activity of NFRe, while exchanging the native segment with the corresponding region of NFR1 maintained transphosphorylation (Figure 4A, lanes 4–6, 7–9). These results corroborate the observed nodule formation in the nfr1-1 expressing the NeKA1 receptor (Table 2 and Figure 2—figure supplement 1).

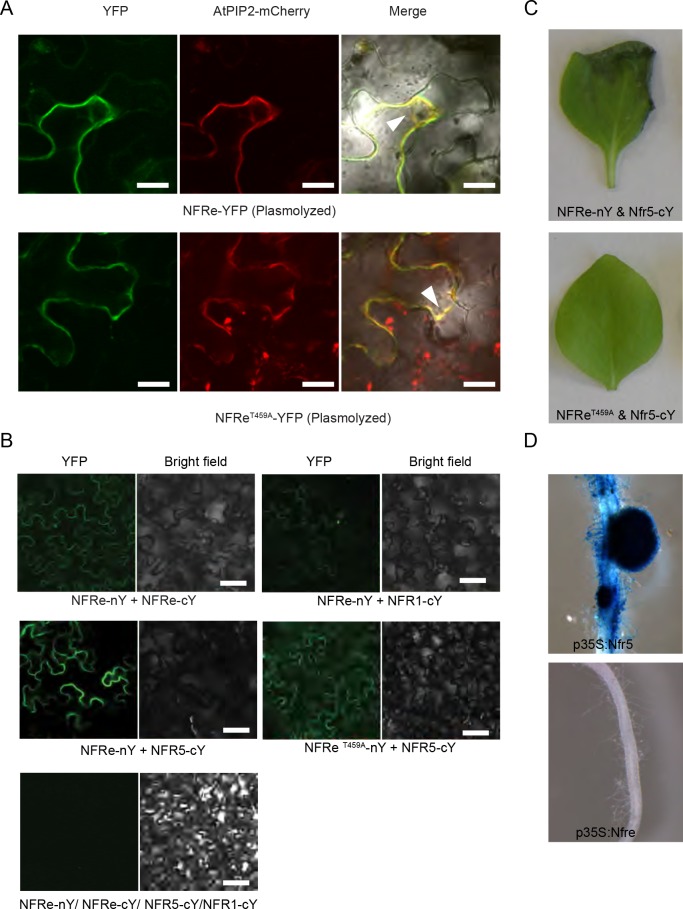

Figure 4. NFRe signalling is dependent of NFR5.

(A) The NFRe kinase phosphorylates NFR5 kinase, whereas the NFReT459A shows no phosphorylation activity. The kinase of NeKA1 receptor in which the activation segment of NFRe was swapped with the corresponding region of NFR1 also phosphorylates NFR5 kinase. NFR1 kinase serves as positive control for NFR5 kinase transphosphorylation. Bovine serum albumin and NFR5 kinase domain are negative controls. (B) Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) of YFP signal indicates protein-protein interactions in tobacco leaves. NFRe forms homomers (NFRe-nY +NFRe cY), and heteromers with NFR1 (NFRe-nY +NFR1 cY), or NFR5 (NFRe-cY +NFR5 nY). Formation of heteromeric complexes with NFR5 is not dependent on an active NFRe kinase (NFRe T459A -nY + NFR5 cY). (C) Working model of Nod factor signalling (green line) in the susceptible zone ensuring an efficient nodulation on the expanding root system. NFRe (dark grey line) has a constant expression in the epidermal cells of the susceptible zone. NFR1 (light grey line) dominates the uninoculated root in terms of expression level and spatial distribution (1). Once the symbiotic process is initiated by the Nod factor (NF), the expression of NFR1 is rapidly downscaled (2). A sustained expression of NFRe in the epidermal cells ensures an idling signalling in the susceptible zone, keeping the expanding root system tuned in to rhizobia (3). NFR1 acts as a master switch triggering recurrent symbiotic events in a fast and efficient manner from NFRe-attuned epidermal cells (4).

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. NFRe is localized on plasma membrane and signals together with NFR5.

Next, we analysed the localisation and molecular properties of full-length NFRe and NFR5 using heterologous expression in Nicotiana benthamiana. The YFP tagged NFRe protein was found to localize to the plasma membrane and to co-localise with the plasma membrane marker, AtPIP2, like previously observed for NFR1 and NFR5 (Madsen et al., 2011) (Figure 4—figure supplement 1). Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) analyses based on split YFP revealed that NFRe formed homomeric complexes alone and heteromeric complexes when co-expressed with either NFR1 or NFR5 (Figure 4B and Figure 4—figure supplement 1). The formation of heteromeric complex with NFR5 was not affected by kinase inactivation (Figure 4B). Like in the case of NFR1-NFR5 co-expression (Madsen et al., 2011), a signalling cascade leading to leaf cell death, dependent on an active NFRe kinase, was identified in N. benthamiana leaves co-expressing NFRe and NFR5 (Figure 4—figure supplement 1). Finally, we analysed whether the NFRe-dependent activation of Nin in L. japonicus roots was dependent on NFR5. Nfre driven by 35S promoter failed to induce Nin:GUS symbiotic reporter in the nfr5-2 mutant background (Figure 4—figure supplement 1 and Supplementary file 3). These results demonstrate that NFRe can interact with, and trans-phosphorylates NFR5 kinase, and induce a signalling cascade dependent on the NFR5 receptor.

Collectively, our results from biochemical studies of the extracellular and intracellular domains of NFRe, together with those obtained from mutant and functional analyses provide evidences for the involvement of NFRe ensuring a robust signalling for symbiosis with nitrogen-fixing rhizobia.

Discussion

Nod factor binding by NFR1-NFR5 LysM receptors is required to induce nodule organogenesis and infection thread formation in L. japonicus (Radutoiu et al., 2003; 2007). Here, we show that the NFR1-NFR5 signalling cascade operates on the framework provided by the epidermal LysM receptor NFRe. NFRe and NFR1 share biochemical and molecular properties that is similar Nod factor-binding affinity, and chitopentaose differentiating capacity when assessed by biolayer interferometry (Broghammer et al., 2012), functional kinases dependent on fully operative domains (Madsen et al., 2011), capacity to phosphorylate, and induce a signalling cascade dependent of NFR5 (Madsen et al., 2011). In spite of these similarities, NFR1 and NFRe have evolved distinct biological properties defined by specific spatio-temporal expression, and downstream signalling cascades controlled by diverged kinases.

The epidermis of the expanding root system is continuously exposed to Nod factors produced by rhizobia present in the rhizosphere. Nevertheless, the number and the location of primordia guiding the epidermal infection threads are precisely determined. Complex regulatory networks involving transcriptional regulators, hormones, shoot- and root-derived signals (Ferguson et al., 2010; Miyata et al., 2013; Sasaki et al., 2014; Miri et al., 2016; Roy et al., 2017), as well as tightly controlled receptor signalling (Mbengue et al., 2010; Kawaharada et al., 2017), collaborate to coordinate how many nodules the plant develops. With this framework in mind, a working model is emerging when considering our findings (Figure 4C). This model incorporates the interplay of the NFR1 and NFRe in the epidermis, ensuring efficient and robust signalling in the susceptible zone of the expanding root system. In the absence of the symbiont, Nfre has a low and constant expression in the susceptible zone, while Nfr1 outnumbers Nfre in terms of expression level and spatial distribution (Figure 4C-1). Once the symbiotic process is initiated, the expression of NFR1 is rapidly downscaled in the susceptible zone (Figure 4C-2). A sustained expression of NFRe in the epidermal cells of the susceptible zone could ensure an idling signalling, keeping the expanding root system tuned in to rhizobia (Figure 4C-3). NFR1 acts as a master switch triggering recurrent symbiotic events in a fast and efficient manner from NFRe-attuned epidermal cells (Figure 4C–4).

In general, protein-carbohydrate interactions are usually weak and low-affine (micromolar-millimolar range) (Holgersson et al., 2005) and signalling therefore, emerges as being controlled by ligand multivalency and/or by receptor multiplicity (Kiessling and Pohl, 1996; Rabinovich, 2002; Vasta et al., 2012). In line with this notion studies of receptors present at the plant and mammalian plasma membrane revealed a conserved strategy to ensure specific, instantaneous, switchable and evolvable downstream signalling; namely, increased responsiveness and specificity via combinatorial systems (Ostrom et al., 2001; Piñeyro, 2009; Bodmann et al., 2015; Bücherl et al., 2017). The signalling properties of NFRe remain to be determined, but our findings based on the properties of this LysM receptor kinase, together with the symbiotic phenotypes of nfre mutants unveil a more complex signalling operating in the epidermal cells of L. japonicus than anticipated from studies of the basic and essential receptor-components.

It is possible that multiple LysM receptors assemble into functional signalling complexes where signalling specificity is the result of the nature of the complex, rather than isolated LysM receptors alone. The mechanistic details of NFR1-NFRe signalling remain to be discovered, but we envision that differences might exist among legumes, since nfr1 in Lotus and lyk3 or sym37 in Medicago and pea have different symbiotic phenotypes (Radutoiu et al., 2003; Smit et al., 2007; Zhukov et al., 2008), indicating distinct evolutionary trajectories after separation of the IRLC (Inverted Repeat-lacking clade) legumes (Sprent, 2008). Tandem NFR1-type receptors are found in all legumes and in non-legume species as well (Liang et al., 2013; De Mita et al., 2014). Ample comparative phylogenomics and trans-complementation studies targeting tandem duplicated LysM receptors will greatly help determining their evolutionary impact and their role in different plant species.

Materials and methods

Phylogenetic tree and alignment

Clustal Omega was used to prepare multiple sequence alignment for phylogenetic analysis. The region between 55 and 251 in this alignment was realignment to adjust the positions of CXC motif. This alignment was used for the phylogenetic analysis with Neighbor Joining. The distance was measured with Jukes-Cantor and the bootstrap was 1000 replicates. These alignment and phylogenetic analyses were performed in the CLC Main Workbench v7.9.1. The amino acid sequence of OsCERK1 (Os08g0538300-01) is available in The Rice Annotation Project Data Base (rap-db). The other sequences below are available in NCBI: AtCERK1 (NP_566689), NFR1 (CAE02590), NFRe (AB503681), LYS2 (AB503682), EPR3 (AB503683), LYS4 (AB503685), LYS5 (AB503686), LYS6 (AB503687), LYS7 (AB503688).

Expression and purification of NFRe, NFR1 and AtCERK1 ectodomains

NFRe and NFR1 ectodomain boundaries were defined by secondary structure prediction performed with PSIPRED (Buchan et al., 2013). Their signal peptides were predicted using the SignalP 4.1 server (Petersen et al., 2011). The AtCERK1 ectodomain boundaries were designed based on the reported crystal structure (Liu et al., 2012). The predicted ectodomain sequences were codon-optimized for insect cell expression and synthesized with an N-terminal gp67 secretion signal peptide and a c-terminal hexa-histidine tag (GenScript, Piscataway, USA) and inserted into the pOET4 transfer vector (Oxford Expression Technologies). Recombinant AcMNPV baculoviruses were produced in Sf9 cells cultured with SFX (Hyclone) or TNM-FH medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (Gibco), 1% (v/v) chemically defined lipid concentrate (Gibco) and 1% (v/v) Pen/Strep (10,000 U/ml, Life Technologies). The FlashBac Gold kit (Oxford Expression Technologies) was utilized according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Viruses were amplified until a third passage virus culture of 500 mL was obtained. For large scale protein expression Sf9 cells were infected with 5% (v/v) of the passage three virus solution and cultured in suspension with serum-free SFX insect cell medium (Hyclone) or BD BaculoGold MAX-XP medium (BD Biosciences, discontinued) supplemented with chemically defined lipid concentrate and Pen/Strep as described above. The culture was maintained in a shaking incubator at 26°C for five days, after which the medium was harvested by centrifugation in a Sorvall RC5plus centrifuge (SLA-1500 rotor) at 6000 rpm at room temperature for 25 min. Subsequently, the cleared medium was dialyzed against 10 volumes of buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 200 mM NaCl) for one day at 4°C with the buffer being exchanged at least four times. The proteins were loaded on a HisTrap excel column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer A and recirculated over 3 days at 4°C using a peristaltic pump. After a washing step with buffer W (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 500 mM NaCl and 20 mM imidazole) proteins were eluted with buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole). Imidazole was removed by dialyzing against buffer A and the purity was improved by a second IMAC purification step using a HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare). The NFRe ectodomain was dialyzed against a low salt buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl and 50 mM NaCl) before purification on a MonoQ column (GE Healthcare). The resulting flow-through containing NFRe was collected and concentrated in a Vivaspin column (10 kDa cut-off, Sartorius Stedim biotech). NFRe and NFR1 were finally purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) and AtCERK1 using a Superdex 75 10/300 GL size exclusion column (GE Healthcare) in SEC buffer (Phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.2, 500 mM NaCl). At each purification step, yield and purity were assayed by SDS-PAGE.

Synthesis of biotinylated R7A Nod factor and chitopentaose conjugates

Biotin conjugates were synthesized using a two-step procedure according to Figure 1—figure supplement 3. O-(2-Aminoethyl)-N-methyl hydroxylamine trifluoroacetic acid salt was prepared as described previously (Bohorov et al., 2006), and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification. Nod factors from Mesorhizobium loti, strain R7A, NodMl-V(C18:1Δ11Z, Cb, Me, AcFuc), containing three main species (3-O-acetylated, 4-O-acetylated, or non-acetylated fucosyl unit) were purified as described previously (Bek et al., 2010). Purified R7A Nod factor (3.6 mg, 2.29 μmol, 5 mM) was dissolved in 0.62 M NaOAc buffer, pH 4.5, containing 50% acetonitrile, and O-(2-aminoethyl)-N-methyl hydroxylamine trifluoroacetic acid salt (150 mM, 30 equiv.) was added. The resulting mixture was allowed to react at room temperature for 16 hr, after which it was concentrated under a nitrogen flow. The intermediate product was purified by semipreparative HPLC on an UltiMate 3000 instrument fitted with a Waters 996 photodiode detector, using a Phenomenex Luna 5 μm, C18(2), 100 Å, 250 × 100 mm semi-preparative column. An isocratic elution at 40% acetonitrile in water, 5 mL/min for 30 min was used. The intermediate eluted at 9.5–11.5 min. Conjugate formation was confirmed by HR-MS (ES+): calcd for [M + H, 1Ac]+ = 1573.8081, found 1573.8185. The purified intermediate was dissolved at a concentration of 10 mM in 50 mM sodium tetraborate buffer, pH 8.5, containing 50% acetonitrile. NHS-dPEG4-biotin (15 mM, 1.5 equiv.) was added. The resulting mixture was allowed to react at room temperature for 16 hr. The biotin conjugate product was purified by semipreparative HPLC as described above. A gradient of 5–100% acetonitrile in water over 40 min, running at 5 mL/min, was used. The conjugate eluted after 21 min (68% acetonitrile). The chromatogram displayed a broad product peak due to the presence of the three species differing in substitution on the fucosyl residue. The biotin-R7A Nod factor conjugate (18% yield) was quantified using the HABA/avidin biotin quantification kit (Pierce). HR-MS (ES+): calcd for [M + 2 hr, 1Ac]2 += 1024.0175, found 1024.0184, and calcd for [M + 2 hr, 0Ac]2 += 1003.0122, found 1003.0129 (Figure 1—figure supplement 3). High-resolution mass spectra (HR-MS) were obtained using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 UHPLC instrument (Thermo) coupled to a Bruker Impact HDII QTOF mass spectrometer. The synthesis of a biotin-chitopentaose (GlcNAc)five conjugate was performed essentially as for the biotin-R7A Nod factor conjugate. The product was purified by HPLC using a Phenomenex Luna 5 μm, C18(2), 100 Å, 250 × 100 mm semi-preparative column, using a gradient of 5–100% acetonitrile in water, 5 mL/min for 40 min. The product eluted after 12.7 min (35% acetonitrile). The final yield of the biotin-(GlcNAc)five conjugate was determined to be 9%. HR-MS (ES+): calcd for [M + 2 hr]2 += 790.3552, found 790.3557 (Figure 1—figure supplement 3).

Biolayer interferometry

Binding of NFRe, NFR1 and AtCERK1 ectodomains to biotin-R7A Nod factor and biotin-(GlcNAc)5 (CO5) was measured on an Octet RED biolayer interferometer (Pall ForteBio). Biotinylated R7A Nod factor and (GlcNAc)5, were immobilized on streptavidin biosensors (for kinetics, Pall ForteBio) at a concentration of 250 nM for 5 min. Immobilization levels of biotin-R7A and biotin-(GlcNAc)five were followed during immobilization and amounted to approximately 2.4 nm and 0.4 nm of saturation, respectively. Interaction with NFRe, NFR1 and AtCERK1 ectodomains was measured in dilution series at protein concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 64 μM (NFRe), 0.78–100 μM (NFR1) or 0.93–160 µM (AtCERK1) for 10 min. Subsequently, dissociation was recorded for 5 min. All steps were conducted in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 0.01% Tween20. Parallel background measurements using biosensors immobilized with free biotin were subtracted from R7A Nod factor and (GlcNAc)five curves to correct for unspecific binding. Sensorgrams were processed using ForteBio Data Analysis 7.0 (Pall ForteBio). Equilibrium dissociation constants from steady-state analysis were calculated in GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software) by nonlinear regression using the response at equilibrium (Req) plotted against protein concentration.

NFRe kinase domain expression and purification

The NFRe, NFR1 and NFR5 kinase domains were predicted using TMHMM Server v. 2.0 and PSIPRED secondary structure prediction. NFRe kinase domain was cloned into pET-30 Ek/LIC vector (Novagen), NFR1 and NFR5 kinase domains were cloned into pET-32 Ek/LIC vectors (Novagen). Three NFRe kinase domain mutants were created using the Quikchange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. For the chimeric kinase of NeKA1, cDNA fragment was assembled by PCR as described previously (Heckman and Pease, 2007). NFRe kinase was expressed into E. coli BL21-CodonPlus, NFR1 and NFR5 kinase into E. coli Rosetta 2. Cultures were grown until OD600 = 0.8 and cold-shocked for 30 min in an ice bath. Protein expression was subsequently induced with 1 mM IPTG and left overnight to shake at 20°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3300 rpm in a Sigma swing-out rotor 13855 and afterwards resuspended in 100 ml lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH8, 400 mM NaCl, 1 mM Benzamidine, 20 mM Imidazole, 5 mMβ-mercaptoethanol and 10% (v/v) glycerol). Resuspended pellets were broken by sonication and cell debris removed by centrifugation at 12000 rpm (F21S-8 × 50 y rotor, ThermoFisher). The resulting supernatant was loaded on a Ni-NTA IMAC affinity column (ThermoFisher) equilibrated with lysis buffer at 4°C using a peristaltic pump. After a wash step with buffer W-kinase (50 mM Tris-HCI pH 8, 1 M NaCl, 1 mM Benzamidine, 50 mM Imidazole, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 10% Glycerol) to remove contaminants, kinases were eluted with buffer B-kinase (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 10% Glycerol). His-tagged TEV protease (homemade) was added to the eluted proteins at a 1:100 (w:w) ratio and dialysed against a dialysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 10% Glycerol) overnight at 4°C. The cleaved kinase domain proteins were subjected to a second round of IMAC affinity column purification and collected in the flow-through. The kinase domain proteins were concentrated in a Vivaspin column (10 kDa cut-off) before being subjected to size exclusion chromatography using either a Superdex 75 or Superdex 200 10/300 GL columns on ÄKTA Purifier system (both GE Healthcare). Purification was performed by isocratic elution in Buffer GF (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 300 mM NaCl and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol). After each purification step, yield and purity were assayed using SDS-PAGE.

In vitro kinase assay

4 µg of purified kinase domain proteins were incubated in Kinase Activity Buffer (2 mM MnCl2, 2 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ZnCl2, 50 mM HEPES pH 7 and 100 µM ATP) and 2mCi ATP, [gamma-32P] (PerkinElmer) in a total reaction volume of 20 µL. 2 µg Myelin Basic Protein (Sigma Aldrich) and 4 µg NFR5 kinase domain were added to the appropriate reactions. Additionally, controls without Myelin Basic Protein, ATP [gamma-32P] were made. The reactions were left to incubate for 1 hr at room temperature before loading and running on a 15% SDS-PAGE Gel. After staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, the gel was transferred on a phosphor plate and exposed overnight before scanning on a Typhoon Scanner (GE Healthcare).

Plant material

Lotus japonicus, ecotype B–129 Gifu (Handberg and Stougaard, 1992) is the wild type used for all experiments. Homozygous nfre (previously called lys1) mutants were identified in the LORE1 collection (Fukai et al., 2012; Urbański et al., 2012) and the primers used for genotyping are listed in Supplementary file 1. Seeds were sterilized and germinated and the 3 days old seedlings were transferred to the corresponding conditions below.

Bacterial strains and constructs

Mesorhizobium loti, strain R7A labelled with GFP or dsRed, and NZP2235 were used for phenotypic analyses. An inoculum density of OD600 = 0.02 was used for all studies. Agrobacterium rhizogenes AR1193 (Stougaard et al., 1987) was used for hairy root transformation. A. tumefasiens AGL1 was used for the transient expression in leaves of N. benthamiana.

The various constructs used for L. japonicus transformation were assembled using Golden Gate Cloning (Engler et al., 2014), and constructs for N. benthamiana were assembled using Gateway system with 35S promoter driving the expression. The details of each construct and primers for cloning are presented in Supplementary file 1. All constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

Complementation and promoter analysis using hairy root

The seedlings for hairy root transformation were moved to half-strength B5 media and transformed as described previously (Stougaard, 1995). The composite plants were transferred to Magenta boxes containing sterile clay granule substrate or to sterile agar plates supplemented with ¼ B and D media and inoculated.

GUS staining and cross section

Transformed roots were incubated in GUS staining buffer [0.5 mg/mL X-Gluc, 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH7.0), 5% methanol, 1 mM K4(Fe(CN)6), 1 mM K3(Fe(CN)6), 0.05% Triton X-100] at 37°C for 18 hr in dark. The samples were washed with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH7.0) and stored in 70% ethanol at 4°C. GUS stained roots and nodules were observed using a Leica M165FC stereomicroscope and Leica DFC 310 FX camera system. Three to five representative samples were used for generating transversal sections, as described previously (Gavrilovic et al., 2016).

Microscopic observations for promoter analysis using tYFPnls

For promoter activity using tYFPnls, transformed roots were fixed with paraformaldehyde and cleared as described previously (Warner et al., 2014). The samples were analysed on a ZEISS confocal microscope LSM780. The whole root images were obtained using Z-stack and tail scan tools, the images of root surface were obtained using Z-stack tool. Final images were generated by Maximum Intensity Projection in ZEN software (ZEISS) or ImageJ.

Quantitative RT-PCR

For transcript measurement by quantitative RT-PCR, 3 days seedlings were moved to agar plates supplemented with 1/4 B and D media and whole roots of 12 days-old (Figure 2—figure supplement 2) or 14 days old (Figure 3—figure supplement 3) plants were harvested after specific treatment as specified in each experiment. The mRNA was isolated from whole roots (Figure 2—figure supplement 2) or the susceptible zone (Figure 3—figure supplement 3) using Dynabeads mRNA DIRECT TM kit (Invitrogen). RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase (Fermentas) was used for cDNA synthesis. The quantitative RT-PCR was performed with LightCycler 480 II and LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master mix (Roche). ATP-synthase (ATP), Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (UBC) and Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) were used as reference genes. The three biological (each consisting of 40 plants in Figure 2—figure supplement 2 or 30 plants in Figure 3—figure supplement 3) and three technical repetitions were used to calculate the geometric mean of the relative transcript levels and the corresponding upper and lower 95% confidence.

Plant phenotyping

Sterile agar plates or clay granule substrate supplemented with ¼ B and D media was used for phenotypic analysis in laboratory and greenhouse conditions (Figure 3A,B). Cologne soil (Zgadzaj et al., 2016) with no additional nutrients or inoculum was used for plant phenotyping in Figure 3—figure supplement 1.

Observation of infection threads (IT)

The 3 day old seedlings were transferred to agar plates supplemented with ¼ B and D media. After 3 days growth, the plants were inoculated with M. loti R7A labelled with dsRed. The infection threads were counted at 9 and 14 days after inoculation.

Nuclear calcium oscillation in root hairs

Seedlings were grown on agar plates supplemented with 1/4 B and D with 12.5 µg/mL AVG for 1–2 weeks. One seedling was transferred to a glass slide and Nod factor treatment was performed using 10–8 M M. loti R7A Nod factor solution. The samples were analysed on a confocal microscope LSM780 (ZEISS) and a water lens (W plan-Apochromat 40x/1.0 DIC M27, ZEISS). YC3.6 was excited at 458 nm, and emissions from ECFP and cpVenus were split into different detectors and collected at 463 to 509 and 519 to 621 nm. Calcium spiking was monitored for up to 3 hr after the Nod factor treatment on each root. Several regions of the same root were monitored for 10 to 30 min, and minimum five nuclei were monitored on each root. In total, 50 nuclei from wild type and 46 nuclei from nfre-1 root hairs were monitored. The fluorescence intensity data collected in the first 10 min for each nucleus was analysed by CaSA software (Russo et al., 2013). For calculation to the mean time between Ca2+ spikes (inter spike interval, ISI) for each genotype, the mean of ISI for one cell was used.

RNA sequencing

For RNA sequencing, 3 days seedlings were moved to agar plates supplemented with 1/4 B and D media and susceptible zone of 14 days-old plants was harvested after specific treatment as specified in Figure 3F. The total RNA was isolated from the susceptible zone (15 mm root pieces) using Nucleo spin RNA plant (Macherey-Nagel). Total RNA (>0.8 µg) from two biological replicas per sample was used by GATC Biotech (Germany) to prepare random primed cDNA library and for sequencing with Illumina HiSeq: read length 1 × 50 bp. For the analysis of the RNA sequencing data the read trimming and mapping were performed by CLC genomics workbench 9.5.3 using Lotus japonicus v3.0 at Lotus base (https://lotus.au.dk/) (Mun et al., 2016), as reference. Differentially expressed genes (log2 fold change >0 or<0, adjusted p value < 0,05) were determined using the DESeq2 R package, with the ‘fittype’ parameter set to ‘local’ and the ‘betaprior’ parameter to ‘true’. The HTS filter R package was integrated in the DESeq2 pipeline before calling for differentially expressed genes, in order to remove from the analysis the genes with low read counts. Venn diagrams were generated with the VennDiagram R package (Chen and Boutros, 2011).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) measurements

Seedlings were germinated and grown on a stack of wet filter paper in upright position at 21°C under 16/8 hr light/dark conditions. Roots of 7 day old seedlings were cut to 0.5 cm pieces, collected to white 96 well flat bottom polystyrene plates (Greiner Bio-One) and kept overnight in sterile water in darkness at room temperature to recover from stress before the treatment. ROS measurements were conducted in a Varioskan Flash Multimode Reader (Thermo Scientific) in luminometric measurement mode. The reaction mixture consisted of the respective elicitor, 20 µM luminol (Sigma) and 5 µg/ml horseradish peroxidase (Sigma). As elicitor 1 µM tetra-N-acetyl-chitotetraose, CO4 (Megazyme) or octa-N-acetyl-chitooctaose, CO8 (IsoSep) was used. In the negative control wells water was replacing the elicitor. In one measuring well six roots (10 mg root material) was used. In one repetition three wells were measured for every treatment for every genotype. At least two repetitions were conducted with similar results.

Protein localization and BIFC studies in N. benthamiana leaves

N. benthamiana, infiltrated leaves were analysed after 3 days using a Zeiss LSM510 MetaConfocal microscope. The leaves were infiltrated with 0.8 M mannitol to induce plasmolysis. The samples were mounted in 30% glycerol on the slide. For cell death in N. benthamiana, infiltrated leaves were observed after 4 days.

Data availability

RNA-seq reads were deposited at ArrayExpress (accession: E-MTAB-5855).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Rebecca Fitchett for proofreading the manuscript, Terry Mun for computational analysis support, Mette Hofmann Asmussen for technical assistance and Finn Pedersen for taking care of the plants. This work was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation grant no. DNRF79, and by The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, as part of Engineering the Nitrogen Symbiosis for Africa.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Contributor Information

Simona Radutoiu, Email: radutoiu@mbg.au.dk.

Thorsten Nürnberger, University of Tübingen, Germany.

Funding Information

This paper was supported by the following grants:

Danmarks Grundforskningsfond DNRF 79 to Jeryl Cheng, Kira Gysel, Zoltan Bozsoki, Yasuyuki Kawaharada, Christian Toftegaard Hjuler, Kasper Kildegaard Sørensen, Simon Kelly, Mikkel Boas Thygesen, Maria Vinther, Knud Jørgen Jensen, Michael Blaise, Lene Heegaard Madsen, Kasper Røjkjær Andersen.

Engineering Nitrogen Symbiosis for Africa Engineering Nitrogen Symbiosis for Africa to Eiichi Murakami, Noor de Jong, Jens Stougaard, Simona Radutoiu.

Additional information

Competing interests

No competing interests declared.

Author contributions

Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation, Investigation, Visualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Investigation, Visualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft.

Data curation, Investigation, Methodology.

Data curation, Investigation, Methodology.

Data curation, Investigation, Methodology.

Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology.

Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology.

Data curation, Validation, Investigation, Visualization, Methodology.

Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Methodology.

Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology.

Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology.

Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology.

Formal analysis, Supervision, Methodology.

Formal analysis, Supervision, Methodology.

Formal analysis, Supervision, Investigation, Visualization, Methodology.

Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Project administration, Writing—review and editing.

Additional files

Data availability

Sequencing data have been deposited under code: E-MTAB-5855

The following dataset was generated:

Murakami, author. Lotus japonicus response to Nod factor: wild type and nfre mutants. 2017 https://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/experiments/E-MTAB-5855/ Publicly available at the European Nucleotide Archive (accession no: E-MTAB-5855)

References

- Antolín-Llovera M, Ried MK, Parniske M. Cleavage of the symbiosis receptor-like kinase ectodomain promotes complex formation with nod factor receptor 5. Current Biology. 2014;24:422–427. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrighi JF, Barre A, Ben Amor B, Bersoult A, Soriano LC, Mirabella R, de Carvalho-Niebel F, Journet EP, Ghérardi M, Huguet T, Geurts R, Dénarié J, Rougé P, Gough C. The Medicago truncatula lysin [corrected] motif-receptor-like kinase gene family includes NFP and new nodule-expressed genes. Plant Physiology. 2006;142:265–279. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.084657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bek AS, Sauer J, Thygesen MB, Duus JØ, Petersen BO, Thirup S, James E, Jensen KJ, Stougaard J, Radutoiu S. Improved characterization of nod factors and genetically based variation in LysM Receptor domains identify amino acids expendable for nod factor recognition in Lotus spp. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2010;23:58–66. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-23-1-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodmann EL, Wolters V, Bünemann M. Dynamics of G protein effector interactions and their impact on timing and sensitivity of G protein-mediated signal transduction. European Journal of Cell Biology. 2015;94:415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohorov O, Andersson-Sand H, Hoffmann J, Blixt O. Arraying glycomics: a novel bi-functional spacer for one-step microscale derivatization of free reducing glycans. Glycobiology. 2006;16:21C–27. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwl044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozsoki Z, Cheng J, Feng F, Gysel K, Vinther M, Andersen KR, Oldroyd G, Blaise M, Radutoiu S, Stougaard J. Receptor-mediated chitin perception in legume roots is functionally separable from Nod factor perception. PNAS. 2017;114:E8118–E8127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706795114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broghammer A, Krusell L, Blaise M, Sauer J, Sullivan JT, Maolanon N, Vinther M, Lorentzen A, Madsen EB, Jensen KJ, Roepstorff P, Thirup S, Ronson CW, Thygesen MB, Stougaard J. Legume receptors perceive the rhizobial lipochitin oligosaccharide signal molecules by direct binding. PNAS. 2012;109:13859–13864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205171109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan DW, Minneci F, Nugent TC, Bryson K, Jones DT. Scalable web services for the PSIPRED Protein Analysis Workbench. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013;41:W349–W357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bücherl CA, Jarsch IK, Schudoma C, Segonzac C, Mbengue M, Robatzek S, MacLean D, Ott T, Zipfel C. Plant immune and growth receptors share common signalling components but localise to distinct plasma membrane nanodomains. eLife. 2017;6:e25114. doi: 10.7554/eLife.25114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Boutros PC. VennDiagram: a package for the generation of highly-customizable Venn and Euler diagrams in R. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mita S, Streng A, Bisseling T, Geurts R. Evolution of a symbiotic receptor through gene duplications in the legume-rhizobium mutualism. New Phytologist. 2014;201:961–972. doi: 10.1111/nph.12549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler C, Youles M, Gruetzner R, Ehnert TM, Werner S, Jones JD, Patron NJ, Marillonnet S. A golden gate modular cloning toolbox for plants. ACS Synthetic Biology. 2014;3:839–843. doi: 10.1021/sb4001504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson BJ, Indrasumunar A, Hayashi S, Lin MH, Lin YH, Reid DE, Gresshoff PM. Molecular analysis of legume nodule development and autoregulation. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology. 2010;52:61–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukai E, Soyano T, Umehara Y, Nakayama S, Hirakawa H, Tabata S, Sato S, Hayashi M. Establishment of a Lotus japonicus gene tagging population using the exon-targeting endogenous retrotransposon LORE1. The Plant Journal. 2012;69:720–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilovic S, Yan Z, Jurkiewicz AM, Stougaard J, Markmann K. Inoculation insensitive promoters for cell type enriched gene expression in legume roots and nodules. Plant Methods. 2016;12:4. doi: 10.1186/s13007-016-0105-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handberg K, Stougaard J. Lotus japonicus, an autogamous, diploid legume species for classical and molecular genetics. The Plant Journal. 1992;2:487–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.1992.00487.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman KL, Pease LR. Gene splicing and mutagenesis by PCR-driven overlap extension. Nature Protocols. 2007;2:924–932. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch S, Kim J, Muñoz A, Heckmann AB, Downie JA, Oldroyd GE. GRAS proteins form a DNA binding complex to induce gene expression during nodulation signaling in Medicago truncatula. The Plant Cell Online. 2009;21:545–557. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holgersson J, Gustafsson A, Breimer ME. Characteristics of protein-carbohydrate interactions as a basis for developing novel carbohydrate-based antirejection therapies. Immunology and Cell Biology. 2005;83:694–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaharada Y, Kelly S, Nielsen MW, Hjuler CT, Gysel K, Muszyński A, Carlson RW, Thygesen MB, Sandal N, Asmussen MH, Vinther M, Andersen SU, Krusell L, Thirup S, Jensen KJ, Ronson CW, Blaise M, Radutoiu S, Stougaard J. Receptor-mediated exopolysaccharide perception controls bacterial infection. Nature. 2015;523:308–312. doi: 10.1038/nature14611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaharada Y, Nielsen MW, Kelly S, James EK, Andersen KR, Rasmussen SR, Füchtbauer W, Madsen LH, Heckmann AB, Radutoiu S, Stougaard J. Differential regulation of the Epr3 receptor coordinates membrane-restricted rhizobial colonization of root nodule primordia. Nature Communications. 2017;8:14534. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S, Radutoiu S, Stougaard J. Legume LysM receptors mediate symbiotic and pathogenic signalling. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2017;39:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiessling LL, Pohl NL. Strength in numbers: non-natural polyvalent carbohydrate derivatives. Chemistry & Biology. 1996;3:71–77. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(96)90280-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, Cao Y, Tanaka K, Thibivilliers S, Wan J, Choi J, Kang C, Qiu J, Stacey G. Nonlegumes respond to rhizobial nod factors by suppressing the innate immune response. Science. 2013;341:1384–1387. doi: 10.1126/science.1242736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Liu Z, Song C, Hu Y, Han Z, She J, Fan F, Wang J, Jin C, Chang J, Zhou JM, Chai J. Chitin-induced dimerization activates a plant immune receptor. Science. 2012;336:1160–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.1218867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann GV, Shimoda Y, Nielsen MW, Jørgensen FG, Grossmann C, Sandal N, Sørensen K, Thirup S, Madsen LH, Tabata S, Sato S, Stougaard J, Radutoiu S. Evolution and regulation of the Lotus japonicus LysM receptor gene family. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2010;23:510–521. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-23-4-0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen EB, Antolín-Llovera M, Grossmann C, Ye J, Vieweg S, Broghammer A, Krusell L, Radutoiu S, Jensen ON, Stougaard J, Parniske M. Autophosphorylation is essential for the in vivo function of the Lotus japonicus Nod factor receptor 1 and receptor-mediated signalling in cooperation with Nod factor receptor 5. The Plant Journal. 2011;65:404–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen EB, Madsen LH, Radutoiu S, Olbryt M, Rakwalska M, Szczyglowski K, Sato S, Kaneko T, Tabata S, Sandal N, Stougaard J. A receptor kinase gene of the LysM type is involved in legume perception of rhizobial signals. Nature. 2003;425:637–640. doi: 10.1038/nature02045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbengue M, Camut S, de Carvalho-Niebel F, Deslandes L, Froidure S, Klaus-Heisen D, Moreau S, Rivas S, Timmers T, Hervé C, Cullimore J, Lefebvre B. The Medicago truncatula E3 ubiquitin ligase PUB1 interacts with the LYK3 symbiotic receptor and negatively regulates infection and nodulation. The Plant Cell. 2010;22:3474–3488. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.075861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JB, Pratap A, Miyahara A, Zhou L, Bornemann S, Morris RJ, Oldroyd GE. Calcium/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase is negatively and positively regulated by calcium, providing a mechanism for decoding calcium responses during symbiosis signaling. The Plant Cell. 2013;25:5053–5066. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.116921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miri M, Janakirama P, Held M, Ross L, Szczyglowski K. Into the root: how cytokinin controls rhizobial infection. Trends in Plant Science. 2016;21:178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa H, Sun J, Oldroyd GE, Downie JA. Analysis of Nod-factor-induced calcium signaling in root hairs of symbiotically defective mutants of Lotus japonicus. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2006;19:914–923. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata K, Kawaguchi M, Nakagawa T. Two distinct EIN2 genes cooperatively regulate ethylene signaling in Lotus japonicus. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2013;54:1469–1477. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mun T, Bachmann A, Gupta V, Stougaard J, Andersen SU. Lotus base: an integrated information portal for the model legume Lotus japonicus. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:39447. doi: 10.1038/srep39447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JD, Karas BJ, Sato S, Tabata S, Amyot L, Szczyglowski K. A cytokinin perception mutant colonized by Rhizobium in the absence of nodule organogenesis. Science. 2007;315:101–104. doi: 10.1126/science.1132514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Kaku H, Shimoda Y, Sugiyama A, Shimamura M, Takanashi K, Yazaki K, Aoki T, Shibuya N, Kouchi H. From defense to symbiosis: limited alterations in the kinase domain of LysM receptor-like kinases are crucial for evolution of legume-Rhizobium symbiosis. The Plant Journal. 2011;65:169–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom RS, Gregorian C, Drenan RM, Xiang Y, Regan JW, Insel PA. Receptor number and caveolar co-localization determine receptor coupling efficiency to adenylyl cyclase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:42063–42069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105348200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nature Methods. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñeyro G. Membrane signalling complexes: implications for development of functionally selective ligands modulating heptahelical receptor signalling. Cellular Signalling. 2009;21:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovich G. Role of galectins in inflammatory and immunomodulatory processes. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 2002;1572:274–284. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4165(02)00314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radutoiu S, Madsen LH, Madsen EB, Felle HH, Umehara Y, Grønlund M, Sato S, Nakamura Y, Tabata S, Sandal N, Stougaard J. Plant recognition of symbiotic bacteria requires two LysM receptor-like kinases. Nature. 2003;425:585–592. doi: 10.1038/nature02039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radutoiu S, Madsen LH, Madsen EB, Jurkiewicz A, Fukai E, Quistgaard EM, Albrektsen AS, James EK, Thirup S, Stougaard J. LysM domains mediate lipochitin-oligosaccharide recognition and Nfr genes extend the symbiotic host range. The EMBO Journal. 2007;26:3923–3935. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S, Robson F, Lilley J, Liu CW, Cheng X, Wen J, Walker S, Sun J, Cousins D, Bone C, Bennett MJ, Downie JA, Swarup R, Oldroyd G, Murray JD. MtLAX2, a functional homologue of the Arabidopsis auxin influx transporter AUX1, is required for nodule organogenesis. Plant Physiology. 2017;174:326–338. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo G, Spinella S, Sciacca E, Bonfante P, Genre A. Automated analysis of calcium spiking profiles with CaSA software: two case studies from root-microbe symbioses. BMC Plant Biology. 2013;13:224. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-13-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Suzaki T, Soyano T, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Kawaguchi M. Shoot-derived cytokinins systemically regulate root nodulation. Nature Communications. 2014;5:4983. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit P, Limpens E, Geurts R, Fedorova E, Dolgikh E, Gough C, Bisseling T. Medicago LYK3, an entry receptor in rhizobial nodulation factor signaling. Plant Physiology. 2007;145:183–191. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.100495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprent JI. 60Ma of legume nodulation. What's new? What's changing? Journal of Experimental Botany. 2008;59:1081–1084. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stougaard J, Abildsten D, Marcker KA. The Agrobacterium rhizogenes pRi TL-DNA segment as a gene vector system for transformation of plants. MGG Molecular & General Genetics. 1987;207:251–255. doi: 10.1007/BF00331586. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stougaard J. Agobacterium rhizogenes as a Vector for Transforming Higher Plants. In: Jones H, editor. Plant Gene Transfer and Expression Protocols. Totowa, NJ: Springer New York; 1995. pp. 49–61. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stracke S, Kistner C, Yoshida S, Mulder L, Sato S, Kaneko T, Tabata S, Sandal N, Stougaard J, Szczyglowski K, Parniske M. A plant receptor-like kinase required for both bacterial and fungal symbiosis. Nature. 2002;417:959–962. doi: 10.1038/nature00841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirichine L, Sandal N, Madsen LH, Radutoiu S, Albrektsen AS, Sato S, Asamizu E, Tabata S, Stougaard J. A gain-of-function mutation in a cytokinin receptor triggers spontaneous root nodule organogenesis. Science. 2007;315:104–107. doi: 10.1126/science.1132397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbański DF, Małolepszy A, Stougaard J, Andersen SU. Genome-wide LORE1 retrotransposon mutagenesis and high-throughput insertion detection in Lotus japonicus. The Plant Journal. 2012;69:731–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasta GR, Ahmed H, Bianchet MA, Fernández-Robledo JA, Amzel LM. Diversity in recognition of glycans by F-type lectins and galectins: molecular, structural, and biophysical aspects. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2012;1253:E14–E26. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06698.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernié T, Kim J, Frances L, Ding Y, Sun J, Guan D, Niebel A, Gifford ML, de Carvalho-Niebel F, Oldroyd GE. The NIN transcription factor coordinates diverse nodulation programs in different tissues of the Medicago truncatula root. The Plant Cell. 2015;27:3410–3424. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villadsen K, Martos-Maldonado MC, Jensen KJ, Thygesen MB. Chemoselective reactions for the synthesis of glycoconjugates from unprotected carbohydrates. ChemBioChem. 2017;18:574–612. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201600582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner CA, Biedrzycki ML, Jacobs SS, Wisser RJ, Caplan JL, Sherrier DJ. An optical clearing technique for plant tissues allowing deep imaging and compatible with fluorescence microscopy. Plant Physiology. 2014;166:1684–1687. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.244673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano K, Yoshida S, Müller J, Singh S, Banba M, Vickers K, Markmann K, White C, Schuller B, Sato S, Asamizu E, Tabata S, Murooka Y, Perry J, Wang TL, Kawaguchi M, Imaizumi-Anraku H, Hayashi M, Parniske M. CYCLOPS, a mediator of symbiotic intracellular accommodation. PNAS. 2008;105:20540–20545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806858105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zgadzaj R, Garrido-Oter R, Jensen DB, Koprivova A, Schulze-Lefert P, Radutoiu S. Root nodule symbiosis in Lotus japonicus drives the establishment of distinctive rhizosphere, root, and nodule bacterial communities. PNAS. 2016;113:E7996–E8005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616564113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XC, Cannon SB, Stacey G. Evolutionary genomics of LysM genes in land plants. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2009;9:183. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhukov V, Radutoiu S, Madsen LH, Rychagova T, Ovchinnikova E, Borisov A, Tikhonovich I, Stougaard J. The pea Sym37 receptor kinase gene controls infection-thread initiation and nodule development. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2008;21:1600–1608. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-12-1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]