Abstract

Chronic stress produces maladaptive pain responses, manifested as alterations in pain processing and exacerbation of chronic pain conditions including irritable bowel syndrome. Female predominance, especially during reproductive years, strongly suggests a role of gonadal hormones. However, gonadal hormone modulation of stress-induced pain hypersensitivity is not well understood. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that estradiol is pronociceptive and testosterone is antinociceptive in a model of stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity (SIVH) in rats by recording the visceromotor response to colorectal distention following a 3 day forced swim stress (FS) paradigm. FS induced visceral hypersensitivity that persisted at least 2 weeks in females, but only 2 days in males. Ovariectomy blocked and orchiectomy facilitated SIVH. Furthermore, estradiol injection in intact males increased SIVH and testosterone in intact females attenuated SIVH. Western blots indicated estradiol increased excitatory GluN1 expression and decreased inhibitory mGluR2 expression following FS in male thoracolumbar spinal cord. In addition, the presence of estradiol during stress increased spinal BDNF expression independent of sex. In contrast, testosterone blocked the stress-induced increase in BDNF expression in females. These data suggest that estradiol facilitates and testosterone attenuates stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity by modulating spinal excitatory and inhibitory glutamatergic receptor expression.

Keywords: stress, estradiol, testosterone, visceral pain, hyperalgesia

Introduction

Women disproportionately suffer from chronic pain conditions including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), fibromyalgia, migraine, and temporomandibular joint pain, many of which are comorbid with anxiety or depression disorders7, 9, 11, 29, 37, 110. During the past decades, efforts have been made to explore the mechanisms underlying sex differences in stress-induced anxiety and depression (for review, see8, 72). However, less is known about mechanisms underlying sex differences in stress-induced chronic pain conditions.

Several animal models have been established to investigate stress-induced anxiety and/or depression, some of which were adopted to examine stress-induced pain hypersensitivity. One such model, the forced swim test, was originally used to test for the efficacy of antidepressant drugs, but has been co-opted for use as a short duration sub-chronic stressor to study mechanisms underlying stress-induced pain hypersensitivity. Three consecutive days of forced swim (FS) decreased hot plate response latency, enhanced formalin- and CFA- induced hyperalgesia and increased pCREB and c-Fos expression in the cortex in male Sprague-Dawley rats49, 50, 92, 93. Previous studies in our lab indicated FS induced visceral hypersensitivity in intact female Sprague-Dawley rats and ovariectomized rats with estrogen replacement18, 107.

Changes in neurotransmitter release and/or receptor expression have been reported to account for behavioral changes such as anxiety and depression following stressful events80, 116. Chronic stress also results in neuroplasticity in areas that are closely linked to nociceptive processing39, 94. On the one hand, stress increases pain sensitivity by reducing inhibitory tone in the spinal cord (i.e. through decreasing GABA receptor function66, 91 or inhibitory glutamate receptor activity18). On the other hand, an increase in excitatory glutamate receptor activity has been reported following stress91. Previous work indicates peripheral and spinal glutamate receptors are involved in somatic and visceral nociceptive signal processing and there exists a sex difference in spinal glutamate receptor expression17, 32, 55, 104. However, the contribution of glutamate receptors to sex differences and hormonal modulation of stress-induced visceral sensitivity has not been explored.

Glutamate receptor function is closely related to brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) translation45, 46, 69, 80. BDNF is widely distributed in the spinal cord and supraspinal sites including the cortex, midbrain and cerebellum59, 75, 114 and contributes to pain hypersensitivity following injury13, 81. In males, chronic stress increased spinal BDNF expression in rats and mice, however chronic prenatal stress upregulated spinal BDNF in female, but not male offspring24, 34, 77, 117. Nevertheless, the effect of hormonal modulation on stress-induced changes in spinal BDNF expression and function has not been determined.

We hypothesize that there exists a sex difference in stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity (SIVH) and that male and female sex hormones play opposing roles in mediating the changes. The purpose of the present study was to examine visceral sensitivity in male and female rats following FS and investigate how hormonal modulation influences SIVH. The underlying molecular mechanisms in the spinal cord were also explored.

Methods

Experiments were performed on age-matched intact or gonadectomized adult male and female Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, USA; 10 weeks old on arrival at the UM School of Dentistry animal facility). Rats were acclimated to the housing facility at least 7 days prior to entering the study. Female rats were not tested for estrous cycle stage to reduce differential stressors to the animals. All protocols were approved by the University of Maryland School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conform to the guide for use of laboratory animals by the International Association for the Study of Pain.

Surgery

Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and electromyogram (EMG) electrodes made from Teflon coated 32g stainless steel wire (Cooner Wire Co., Chatsworth, CA) were implanted in the abdominal muscle 7–10 days prior to recording. Rats were subsequently single housed to avoid interfering with cagemate’s electrodes.

Forced swim stress

Rats were subject to 10–20 min forced swim (FS) for three successive days. Briefly, rats were placed in a cylinder (30 cm in diameter, 60 cm in height, filled to 20 cm of tap water, adjusted to a temperature of 26 °C). Rats were placed in the water for 10 min on the first day, and 20 min on the following two days. After each session, rats were dried in a heated area before being returned to their home cages. FS was carried out at the same time in the morning, 9:00 am-noon, to avoid any influence of circadian rhythms. In some rats the struggling behavior during the first three minutes was recorded on each day. The day after the last forced swim was designated Day 1.

Visceromotor response

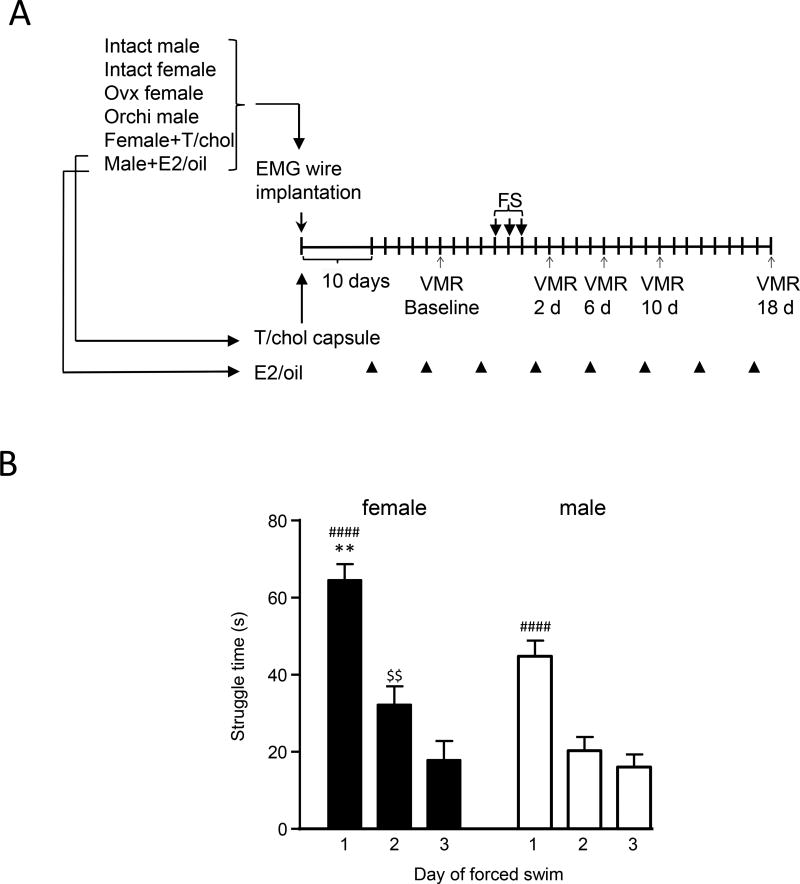

The visceromotor response (VMR) is the electromyogram (EMG) recorded from the abdominal muscles in response to colorectal distention. Starting two days before the baseline recording, rats were acclimated to acrylic rodent restrainers for two hours each day. Rats were then fasted overnight (water ad libitum) to facilitate balloon placement. On the day of the experiment, rats were briefly sedated with isoflurane and a 5–6 cm balloon (made from the finger of a surgical glove attached to Tygon tubing) was inserted through the anus into the descending colon and rectum. The distal end of the balloon was maintained 1 cm proximal to the external anal sphincter by taping the tubing to the tail. Rats were then loosely restrained in acrylic rodent restrainers and allowed 30 min to recover from the anesthesia. Colorectal distention was produced by inflating the distention balloon with air. The pressure was monitored and kept constant by a pressure controller/timing device. Three graded intensity stimulation trials (20, 20, 40, 40, 60, 60, 80, 80 mmHg colorectal distention, 20 seconds each, 3 minute inter-stimulus interval) were run, and the EMG signals were collected with a CED 1401 and analyzed using Spike 2 for windows software (Cambridge Electronic Design, UK). The EMG was rectified and integrated. The value for the 20 seconds prior to distention was subtracted from the value during the 20 second distention. The VMR to colorectal distention was recorded prior to FS (baseline) and on Day 2, 6, 10 and 18 after the last FS (Figure 1A). The data are presented as the mean response from the second and third trials on each day.

Figure 1.

A: experimental timeline for all groups of rats used in behavioral experiments. B: Struggle time for intact female and male rats during first 3 min of FS each day. There was an overall significant interaction effect. Intact females showed greater struggle time than intact males on day 1. ** p<0.01 vs. males; #### p<0.0001 vs. days 2,3; $$ p<0.01 vs. day 3. n=12–14 per group. Not all rats evaluated for struggle time were tested for the VMR.

Western blot

Separate groups of rats were used for western blot. Six days following the last FS rats were euthanized with CO2 and decapitated. The spinal cord was hydraulically extruded and the dorsal part of the T13-L2 (TL) and L6-S2 (LS) spinal cord was isolated. The tissue was homogenized in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The homogenate was centrifuged at 18000 rcf for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and the protein concentration was determined using Bradford assay. Protein was separated on a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel and blotted to nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). The blots were incubated with the respective primary (anti-GluN1 [sc-1467], anti-BDNF [sc-20981], Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; anti-GluN2B [73-097], NeuroMab, UC Davis, Davis, CA; anti-mGluR2 [ab-15672], Abcam, Cambridge, MA; anti-mGluR3 [NBP1-31109], Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO; anti-actin [A5441], Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and fluorescent secondary antibodies (Li-COR, Lincoln, NE). The immunofluorescent signal was detected using the Odyssey Imaging System (Li-COR, Lincoln, NE).

ELISA of serum

Blood samples were collected on day 18 following the last behavioral test. Rats were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and blood collected by cardiac puncture prior to decapitation. Select sex hormone levels in the blood serum were assayed at the University of Virginia, Center for Research in Reproduction. The Ligand Assay and Analysis Core is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD/NIH (NCTRI) Grant P50-HD28934.

Hormone administration

β-estradiol 3-benzoate (E2; Sigma E8515) was dissolved in safflower oil to a final concentration of 0.1mg/ml. Intact male rats were injected with safflower oil (control rats) or E2 (10µg in 100µl, s.c.) every fourth day to mimic the cyclic changes of female sex hormones in intact female rats. This paradigm reverses the decrease in visceral sensitivity following ovariectomy and the level of E2 decreases over several days54. Experiments were designed so E2 injections were given 24 hrs prior to the first FS session or 24 hrs prior to a VMR recording. In contrast, in ovariectomized rats steady state levels of estradiol produced by E2 pellet implants did not affect the VMR produced by bladder distention96 so was not considered for this study.

Testosterone has a short halflife and must be injected daily to reach physiological concentrations51. This is impractical since injecting a rat daily over weeks is probably stressful. However, testosterone capsules deliver a steady state concentration of testosterone for weeks76, 118. In the current study, intact female rats were implanted in the back of the neck with Testosterone (Testosterone; Sigma T1500) or cholesterol (chol; Sigma C8667) capsules made from 2 cm silastic tubing (1.57-mm I.D. × 3.18-mm O.D; Dow Corning Corporation, Midland, MI). The ends of capsules were sealed with DAP 100% silicone Household Adhesive. Capsule size was selected based on previous publications99, 111, 118. All drugs were purchased from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Statistics

The data are expressed as mean ± SEM and were analyzed in Graphpad Prizm V.6 using t-test, one–way or two-way RM ANOVA. Bonferroni multiple comparison was used to test between groups as appropriate. p< 0.05 was considered significant. The VMR data are presented two ways. The stimulus-response curves for increasing intensities of colorectal distention were plotted for each time point (day). These data were analyzed by 2 way repeated measures ANOVA with time and distention pressure as variables. In all cases there was a significant main effect of pressure (response increased with increasing distention pressure) and it is not reported in the results. If there was a significant effect of time or a time × pressure interaction, time was further analyzed by Bonferroni multiple comparison and reported in the bar graphs showing the area under the curve (AUC) for days post stress. The area under the curve is the sum of the response to the 4 distention pressures on each day.

Results

Struggle behavior during FS

Rats subjected to FS showed two major forms of behavior in the water: struggling defined as splashing with both forepaws, vigorously attempting to climb the container walls or diving; and immobility defined as floating with minimal paw movement necessary to keep the head above water. Struggle time was recorded during the first 3 minutes of FS each day. Rats remained immobile for the rest of the time during each forced swim session. During the 3 minute period there was a significant time × sex interaction (2 way RM ANOVA: F(12,118)=4.088, p=0.0192; Figure 1B). In both male and female rats, the struggle behavior lasted the longest on the first day, and then decreased on the following two days. Intact female rats had significantly longer struggle behavior than intact male rats on the first day of FS (73.4±5.3 vs. 37.3±5.5 sec., p<0.01). There was no difference in struggle time between days 2 and day 3 in males, but females struggled longer on day 2 than day 3.

Effects of stress on visceral sensitivity in intact male and female rats

In intact female rats, FS resulted in visceral hypersensitivity to noxious intensities of colorectal distention as early as 2 days (earliest time measured) and lasting at least 18 days (latest time measured; 2 way RM ANOVA, time: F(4,56)=4.285, p=0.0043; time × pressure: F(12,168)=4.797, p<0.0001; Figure 2A,B). The increase in visceral sensitivity to colorectal distention occurred at 40, 60, and 80 mmHg of distention, while responses to 20 mmHg of distention were not changed (Figure 2A). Multiple comparison of the area under the curve showed a significant increase in visceral sensitivity over time compared to baseline (Figure 2B).

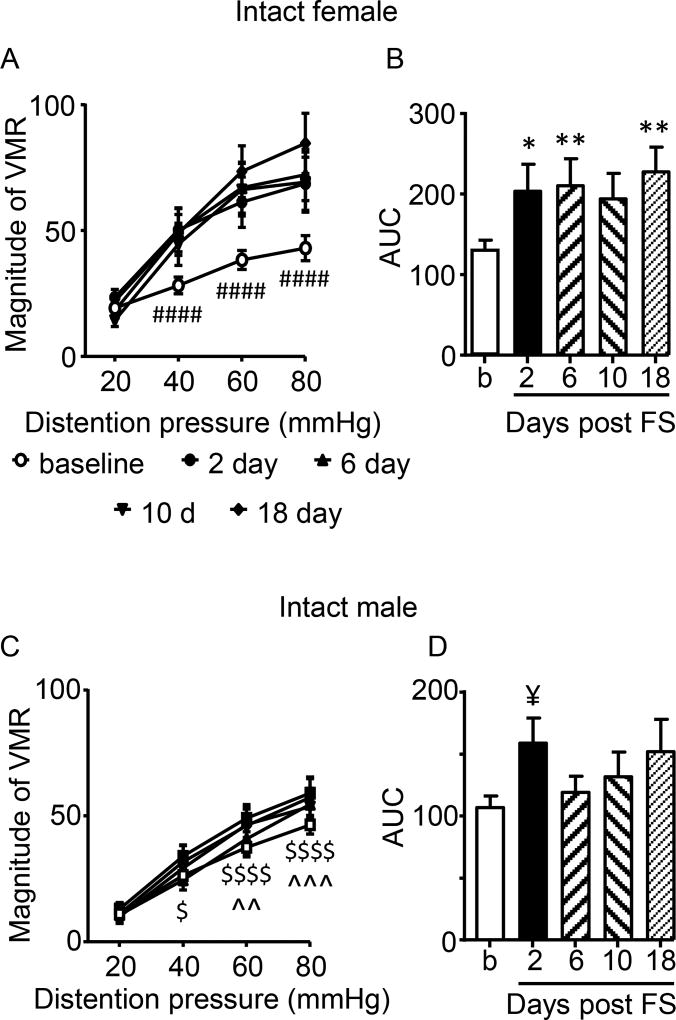

Figure 2.

Effect of sex on stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity. A,B: Stress increased visceral sensitivity for at least 18 days following the end of the 3 day forced swim paradigm in female rats. N=15. C,D: There was a shorter duration visceral hypersensitivity in males. N=17. *,** p<0.05, 0.01 vs. baseline; #### p<0.0001 vs. other times except 10 days at 40 mmHg (p<0.01); $, $$$$ p<0.05. 0.0001 vs. 2 days; ^^,^^^ p<0.01,0.001 vs. 18 days; ¥ p<0.05 vs. baseline (t-test).

In contrast, in males there was a much smaller change in visceral sensitivity. There was no overall effect of time (p=0.1837), but there was a pressure × time interaction (2 way RM ANOVA: F(12,192)=1.930, p=0.0330; Figure 2C). Two days post FS, there was an increase in visceral sensitivity to 40, 60 and 80 mmHg of distention. Analysis of the area under the curve revealed visceral hypersensitivity occurred only at day 2 vs. baseline (t-test (30) = 1.940, p=0.0309); Figure 2D).

Sex hormone manipulation modulates FS- induced visceral sensitivity

Two types of hormonal manipulation were employed to determine the role of gonadal hormones on SIVH. First the effect of hormone depletion on SIVH was determined. Females were ovariectomized (OVx) before the baseline response to colorectal distention was recorded. As opposed to intact females, stress failed to induce visceral hypersensitivity in OVx rats (2 way RM ANOVA, time: F(4,28)=1.886, p=0.1408; time × pressure: p=0.1019; Figure 3A,B).

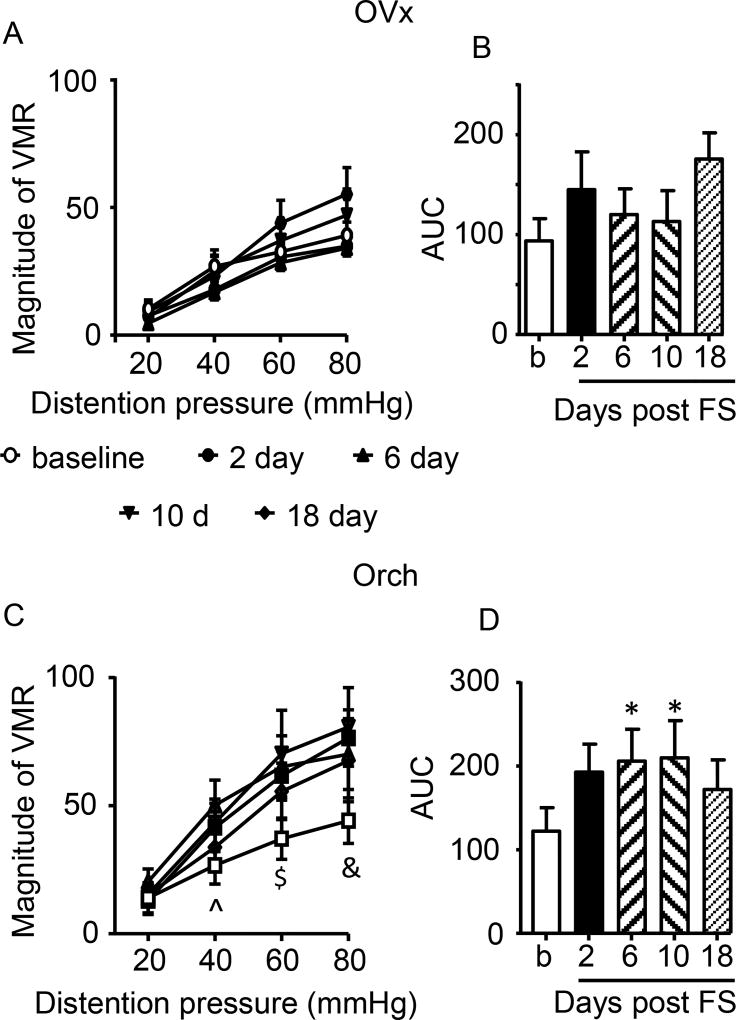

Figure 3.

Effects of hormone depletion on SIVH. A,B: Stress failed to induce visceral hypersensitivity following ovariectomy. N=8. C,D: Stress induced significant visceral hypersensitivity following orchiectomy. ^ p<0.05 (10 d), p<0.001 (6d); $ p<0.05 (18d), p<0.001 (2d), p<0.0001 (6,10d); & p<0.001 (6,18d), p<0.0001 (2,10d); * p<0.05 vs. baseline. N=8.

In contrast, following orchiectomy (Orch), stress resulted in a significant increase in visceral sensitivity to noxious, but not innocuous intensities of colorectal distention (2 way RM ANOVA, time×pressure: F(12,84)=2.484, p=0.0078; time: p=0.1721; Figure 3C,D). Analysis of the area under the curve showed a significant increase in the magnitude of the VMR at 6 and 10 days post stress, returning to baseline at 18 days (Figure 3D). These data suggest loss of E2 or other gonadal hormones in females prevents stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity, while loss of testosterone in males allows SIVH to emerge.

To further determine the role of sex hormones on SIVH, the major sex hormones were administered to intact rats of the opposite sex. Intact females were implanted with capsules containing testosterone which significantly attenuated FS-induced visceral hypersensitivity. There was no effect of time, but there was a time × pressure interaction (2 way RM ANOVA; Time × pressure: F(12,108)=2.571, p=0.0049; Time: p=0.3497; Figure 4A,B). The blood serum level of testosterone in female rats with testosterone capsules for 18 days was increased so it was not significantly different from intact male rats (t-test; t=1.783, df=19, p=0.0906; Figure 4C).

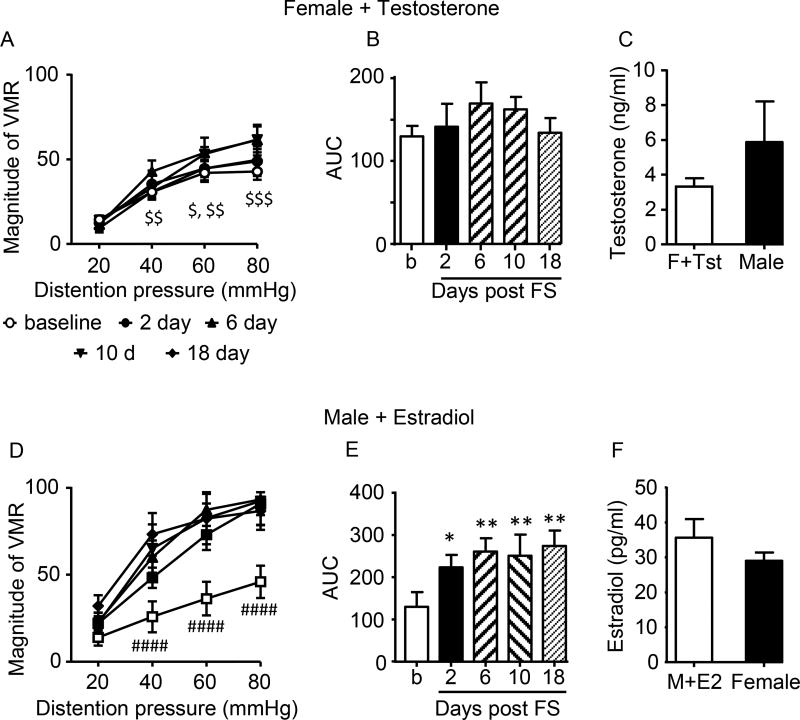

Figure 4.

Effect of hormone addition on stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity. A,B: testosterone administration to intact female rats blocked SIVH. N=10. C: serum testosterone concentration in females + testosterone vs. intact males. D,E: E2 administration to intact males facilitated SIVH. N=7. *,** p<0.05, 0.01 vs. baseline; #### p<0.0001 vs. other times except 2 days at 40 mmHg (p<0.01); $ p<0.05 vs. 10d; $$ p<0.01 vs. 6d; $$$ p<0.0001 vs. 6,10d). F: serum E2 concentration in males + E2 vs. intact females.

Intact male rats were injected with E2 every fourth day, using a paradigm of E2 replacement we previously used in ovariectomized rats54, 107. Injection of E2 increased visceral sensitivity following stress starting at day 2 (2 way RM ANOVA, Time × pressure: F(12,72)=3.668, p=0.0003; time: F(4,24)=4.844, p=0.0052; Figure 4D,E). SIVH was maintained through day 18 following the same increase in visceral sensitivity to noxious, but not innocuous, stimuli observed in the intact female rats. The plasma E2 concentration on day 18, 24 hrs following the last E2 injection, was increased in the E2 injected males and was not significantly different from intact female rats (t-test; t=1.306, df=47, p=0.1981; Figure 4F). There was no change in the VMR to colorectal distention over time in male rats that received periodic subcutaneous injection of E2 without FS (data not shown).

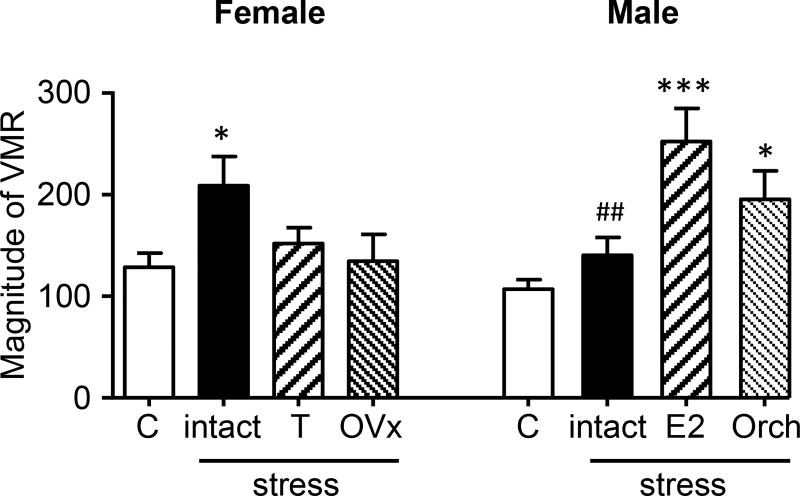

Figure 5 summarizes the SIVH data, plotting the mean response for days 2–18 following stress under the different conditions (Female, ANOVA: F(3,43)=3.040, p=0.0390; Male, ANOVA: F(3,42)=9.119; p<0.0001). The data support the hypothesis that E2 is pronociceptive and testosterone is antinociceptive. Furthermore, the effect of these hormones on visceral sensitivity is independent of sex.

Figure 5.

Summary of hormonal modulation of SIVH; data are the mean response for post-stress days 2–18. Control (C): intact female or male in the absence of stress. Intact: female or male following stress. T, E2: addition of hormone; OVx, Orch: hormone depletion. *,*** p<0.05, 0.001 vs. control; ## p<0.01 vs. male + E2.

Molecular mechanisms involved in FS- induced sensitization in the spinal cord

The L6-S2 (LS) and T13-L2 (TL) spinal segments are both innervated by colonic afferents. The LS spinal cord mediates the majority of colonic nociceptive processing to acute visceral stimuli. The TL spinal cord becomes more involved in nociceptive processing under pathological circumstances such as colonic inflammation106, 112, 113. Previous studies of stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity focused on neuronal processing in the LS spinal cord18, 117. It is unknown how the TL spinal cord contributes to colonic nociceptive processing following stress. It has been established that estrogen and stress induce changes in inhibitory and excitatory glutamate receptor expression12, 18, 91, 104, we therefore examined selective glutamatergic receptor expression six days following the end of FS in the TL and LS spinal cord of intact and hormone- treated male and female rats.

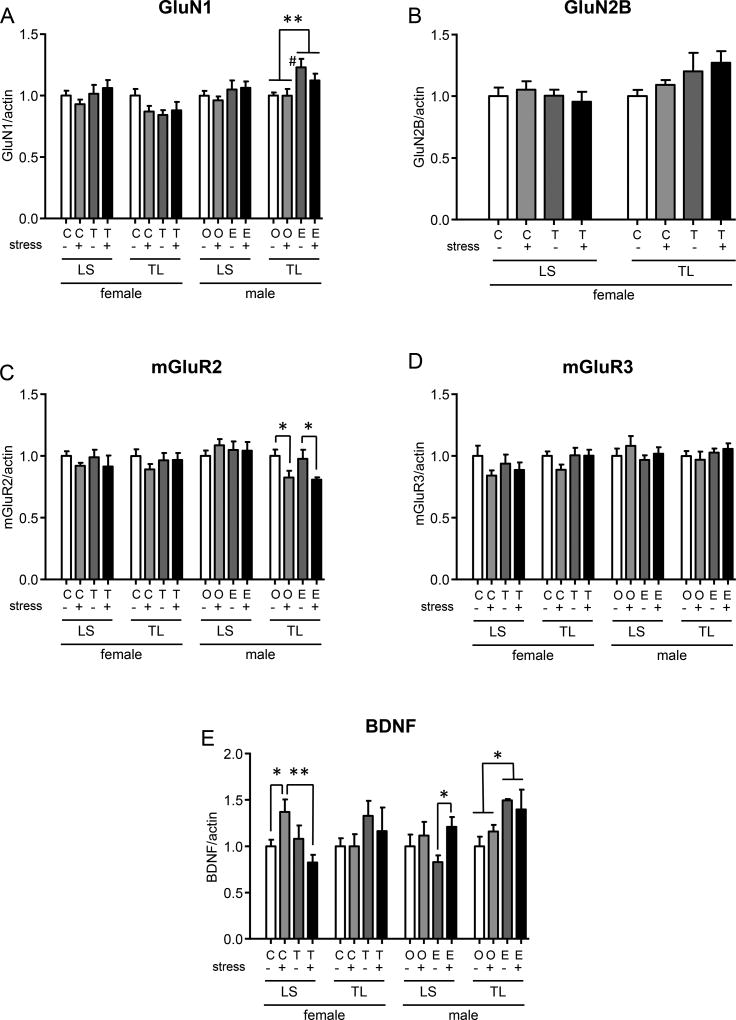

It is well acknowledged that spinal glutamate receptors are involved in painful signal processing. The ionotropic glutamate receptors GluN1 and GluN2 are generally excitatory, while the metabotropic mGluR2/3 receptors are inhibitory70, 82. In male rats, E2 increased spinal GluN1 expression in the TL, but not the LS spinal cord consistent with E2 facilitating SIVH in males, but there was no additional effect of stress (TL: 2way ANOVA, hormone: F(1,10)=10.26, p=0.0094; Figure 6A). There was no change in GluN1 or GluN2B expression in the female LS or TL spinal cord (Figure 6A,B). Stress decreased mGluR2 expression in the male TL spinal cord, but this was independent of hormone manipulation (2 way ANOVA, stress: F(1,10)=11.29, p=0.0072; Figure 6C). There was no change in mGluR3 expression.

Figure 6.

Western blots from TL and LS spinal cord segments 6 days following the end of FS. Two-way ANOVA compared the effect of stress and hormone treatment separately in the TL and LS spinal cord of male and female rats. Significant ANOVAs are reported in the text. Significant comparisons are shown. *, ** p<0.05, 0.01. # p<0.05 vs. oil without stress.

Spinal BDNF is pro-nociceptive74, 105 and the expression of BDNF and its receptors is closely related to glutamate receptor function and regulated by estrogen and stress throughout the brain45, 46, 58, 69, 80, 84. BDNF expression was increased in the LS spinal cord following FS in E2-treated males compared to E2-treated males without stress (2 way ANOVA, stress: F(1,22)=4.566, p=0.0440) (Figure 6E). In the male TL spinal cord, E2 alone increased BDNF expression (2 way ANOVA, hormone: F(1,9)=5.877, p=0.0383). Stress had no effect on BDNF expression in the absence of E2. In the female LS spinal cord there was a stress × hormone interaction, stress increased BDNF in normal females (cholesterol), but decreased BDNF in testosterone treated females (2 way ANOVA, stress × hormone: F(1,24)=7.048, p=0.0139). Taken together, the results indicate the presence of E2 during stress increases BDNF expression contributing to SIVH. In contrast, testosterone blocks the stress-induced increase in BDNF expression in males and females.

Discussion

The present study shows that FS-induced visceral hypersensitivity persisted several weeks in intact female, but not intact male Sprague-Dawley rats. Visceral hypersensitivity was not observed following ovariectomy suggesting a facilitatory effect of female gonadal hormones (likely E2) on FS-induced visceral signal processing. The pronociceptive effect of E2 was further supported by the results showing male rats injected with E2 developed visceral hypersensitivity following FS. In contrast, testosterone was found to be antinociceptive: orchiectomy increased SIVH in males and testosterone capsule implants attenuated SIVH in females. Western blot analysis indicated hormone modulation and FS induced a complex pattern of plasticity in glutamatergic signaling in spinal segments receiving colonic afferent input. In addition, FS increased the nerve growth factor BDNF in females and E2 injected males while testosterone blocked the stress-induced increase in BDNF in females. These data suggest that estradiol facilitates and testosterone attenuates stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity, possibly by modulating spinal neuronal activity.

Female rats are more sensitive to FS

FS is a sub-chronic stressor for the study of stress-induced changes in memory, cognition and pain20, 43, 48–50, 85–87, 92, 93, 95, 102. Rodents initially struggle upon introduction to forced swim, but switch to an immobility state which increases during subsequent days of FS. Originally, the immobility was thought to model depression since it was reversed by antidepressant like drugs89, 90. However, recent reports suggest the decrease in struggle time is a learned behavior with epigenetic underpinnings23, 95. Nevertheless, FS activates an HPA response increasing corticosterone release indicating it is a stressor, one consequence being development of hyperalgesia36, 87. In the present study, we observed a significantly prolonged struggle time on the first day of FS in intact female rats as compared with males, suggesting FS is more stressful to female rats. Indeed, 15 min of FS induced a significantly higher elevation of serum corticosterone in female rats compared to males6. Concomitantly, we found female rats had an enhanced VMR to colorectal distention following FS, possibly due to a more significant change in the HPA axis response.

Sex difference and hormonal modulation of FS- induced visceral hypersensitivity

During the past decades, other groups have examined the effects of stress, and to a lesser extent sex, on visceral sensitivity using different stress models in other rat strains. One of the most widely used paradigms is water avoidance stress. In female and to a lesser extent male Wistar rats, 10 day water avoidance stress results in visceral hypersensitivity15, 31, 47, 61, 63, 119. These results are partially in agreement with our findings in spite of the differences in the stress model, rat strain and the method of measuring visceral pain sensitivity. However, these studies did not evaluate the long term effects of stress, providing limited clinical relevance.

Previous studies on FS- induced changes in pain behavior were mostly carried out using somatic pain models, which demonstrated that FS- induced hypersensitivity to mechanical, thermal and chemical stimuli in male Sprague-Dawley rats49, 85, 92, 93, increased spinomedullary neuron responses to TMJ stimuli in female rats86, and exacerbated musculoskeletal pain manifested by a decrease in grip strength and tail flick latency in female mice1, 2. However, it is not known how FS influences visceral signal processing or if the effects are sexually dimorphic. This is of particular importance since visceral hypersensitivity is one of the major complaints of patients with IBS, a chronic pain condition with a clear female predominance, and stress is recognized as one of the major confounding factors in its development21, 30, 78. In the current study, we observed a significant increase in the magnitude and duration of the VMR to noxious intensities of colorectal distention following stress in female rats. In contrast, male rats only showed a modest and transient increase of visceral sensitivity, suggesting sex hormones may play important roles in stress induced changes in visceral signal processing.

Gonadal hormones modulate nociceptive sensitivity and are a contributing factor underlying sex difference in acute, inflammatory and neuropathic pain73, 79, 108. While many studies using somatic and visceral pain models indicate E2 is pronociceptive16, 57, 96, 100, 120, contradictory results have been reported38, 65, 88. This is possibly due to many factors including fluctuating or steady state hormone levels, selective activation of different receptor subtypes, the site of action and neuroimmune interactions can influence the direction of effect108. For example, in the colorectal distention model, the activation of estrogen receptor α is pronociceptive while activation of estrogen receptor β is antinociceptive19, 52. In ovariectomized rats fluctuating plasma E2 levels from a bolus injection increased visceral sensitivity, but high steady state levels from implanted pellets did not96. In contrast, testosterone has consistently been shown to be anti-nociceptive in animals4, 5, 35, 41, 62, 67, and clinical studies suggest a protective/antinociceptive action of testosterone3, 115. In a recent study, it was reported that the protective effect of endogenous testosterone on the development of TMJ nociception in male rats was mediated by the activation of central opioid mechanisms67.

Similarly, gonadal hormones modulate the effects of stress on pain sensitivity. An estrogen dependent effect of partial restraint stress- induced visceral hypersensitivity was observed in female Wistar rats14 or following early life stress in Long-Evans rats22. In human volunteers, cortisol levels were negatively correlated with pain thresholds and testosterone levels were positively correlated with pain thresholds during acute stress26. In the current study estradiol enhanced stress-induced visceral sensitivity in males, while testosterone dampened stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity in females. This modulating effect of cross hormone manipulation on stress responses in intact rats suggests the effects of the hormones were activational, supporting our previous report of activational effects of E2 and stress on visceral sensitivity in ovariectomized rats107. In addition, the plasma concentration of injected hormones achieved in this study, comparable to the naturally occurring concentration in the opposite sex, was sufficient to overcome the pro- or anti-nociceptive effects of naturally occurring E2 and testosterone, respectively. However, since the hormones were administered systemically, the site(s) where they produced the pro- or anti-nociceptive effect is unknown and it cannot be assumed that endogenous and exogenous hormones work in the same way.

Neurochemical changes in the spinal cord following FS

FS induced neurochemical changes in several brain areas including the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, which are involved in the emotional component of pain27. The spinal mechanisms of FS induced hypersensitivity remains unclear. It has been demonstrated that FS causes an imbalance of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitter release, manifested by an increase of glutamate release and a decrease of GABA release in the spinal cord49, 91, 101. Our previous studies indicate estradiol increases spinal processing of visceral nociception by increasing spinal NMDA receptor GluN1 and GluN2B subunit expression53, 56. On the other hand, the activation of group II metabotropic glutamate receptors mGluR2/3, which is predominately expressed presynaptically in primary sensory neurons, inhibits nociception33, 42. Results from our lab and others indicate epigenetic regulation of spinal mGluR2/3 may be involved in stress- and inflammation- induced visceral and somatic hypersensitivity17, 18, 25. In the current study, we focused on exploring sex differences and the effects of stress/ hormonal manipulation on glutamatergic receptors in the spinal cord.

The lumbosacral (LS) spinal cord receives colonic input over the pelvic nerve and mediates the majority of colonic nociceptive processing to acute visceral stimuli. Blocking pelvic nerve colonic afferent input eliminates the VMR to colorectal distention. Following colonic inflammation there is a partial recovery of the VMR that is attributed to nociceptive processing in the TL spinal cord106, 112, 113. Patients with abdominal pain conditions (e.g., IBS, Crohn’s disease) show regions of referred pain that expand into TL dermatomes, suggesting chronic visceral pain conditions are partially reliant on nociceptive processing in the TL spinal cord10, 97, 103. In the current study conditions that increased visceral hypersensitivity were associated with increases in excitatory NMDA receptor signaling and a decrease in inhibitory mGluR2 signaling. E2 increased GluN1 expression in the male TL spinal cord while stress decreased mGluR2 in the same segments.

BDNF belongs to the neurotrophin family which also includes nerve growth factor (NGF) and neurotrophin 3 and 4/5. It is involved in promoting the survival or regeneration of embryonic and adult sensory neurons59, 83, 98, 114. Changes of glutamate receptor function is closely related to changes of BDNF translation45, 46, 69, 80. Stress- induced changes in synaptic plasticity, cellular atrophy and loss is mediated by BDNF in the hippocampus and amygdala44, 60, 64, 71. Under inflammatory or neuropathic pain conditions, spinal sensitization and plasticity occur following increased release of BDNF from peripheral afferents and spinal microglia28, 40, 68, 109. In the present study, we observed an increase of spinal BDNF by stress in females and in the presence of E2 in males, and demonstrated the increase was diminished by administrating testosterone in female rats. This finding is consistent with a previous study showing chronic prenatal stress upregulated BDNF expression in the lumbosacral dorsal horn that correlated with the exacerbation of visceral hypersensitivity in female, but not in male offspring, due to a significant increase in RNA Pol II binding, histone H3 acetylation, and significant decrease in histone deacetylase 1 association with the core promoter of BDNF in female offspring117.

In conclusion, the present study shows a pronociceptive role for E2 and an antinociceptive role for testosterone in stress- induced visceral pain processing. This may partially due to different changes of spinal excitatory or inhibitory glutamatergic receptors by E2/testosterone in the presence or absence of stress. As the hormonal manipulations were not confined to the spinal cord, modulation in additional nuclei in the central nervous system may contribute to the changes in visceral sensitivity as well.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Stress induced visceral hypersensitivity in male and female Sprague-Dawley rats

The hypersensitivity persisted several weeks in females, a few days in males

Ovariectomy blocked and orchiectomy facilitated the hypersensitivity

E2 in males increased hypersensitivity, testosterone in females decreased it

E2 and testosterone altered glutamatergic receptor expression in the dorsal horn

Perspective.

Stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity (SIVH) is more robust in females. Estradiol facilitates while testosterone dampens the development of SIVH. This could partially explain the greater prevalence of certain chronic visceral pain conditions in women. An increase in spinal BDNF is concomitant with increased stress-induced pain. Pharmaceutical interventions targeting this molecule could provide promising alleviation of SIVH in women.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH NR015472, NS37424 and the Department of Neural and Pain Sciences.

We thank Sangeeta Pandya for technical support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures:

The authors have nothing to declare and have no conflicts of interest.

Contributions: YJ designed study, performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote manuscript; BH performed experiments and analyzed data; JL performed experiments; RJT designed study, analyzed data and wrote manuscript.

References

- 1.Abdelhamid RE, Kovacs KJ, Nunez MG, Larson AA. Depressive behavior in the forced swim test can be induced by TRPV1 receptor activity and is dependent on NMDA receptors. Pharmacol. Res. 2014;79:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdelhamid RE, Kovacs KJ, Pasley JD, Nunez MG, Larson AA. Forced swim-induced musculoskeletal hyperalgesia is mediated by CRF2 receptors but not by TRPV1 receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2013;72:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aloisi AM, Ceccarelli I, Carlucci M, Suman A, Sindaco G, Mameli S, Paci V, Ravaioli L, Passavanti G, Bachiocco V, Pari G. Hormone replacement therapy in morphine-induced hypogonadic male chronic pain patients. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2011;9:26. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aloisi AM, Ceccarelli I, Fiorenzani P. Gonadectomy Affects Hormonal and Behavioral Responses to Repetitive Nociceptive Stimulation in Male Rats. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003;1007:232–7. 232–237. doi: 10.1196/annals.1286.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aloisi AM, Ceccarelli I, Fiorenzani P, De Padova AM, Massafra C. Testosterone affects formalin-induced responses differently in male and female rats. Neurosci Lett. 2004;361:262–264. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armario A, Gavalda A, Marti J. Comparison of the behavioural and endocrine response to forced swimming stress in five inbred strains of rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1995;20:879–890. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003;163:2433–2445. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bangasser DA, Valentino RJ. Sex differences in stress-related psychiatric disorders: neurobiological perspectives. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014;35:303–319. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berkley KJ. Sex differences in pain. Behav. Brain Sci. 1997;20:371–380. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x97221485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernstein CN, Niazi N, Robert M, Mertz H, Kodner A, Munakata J, Naliboff B, Mayer EA. Rectal afferent function in patients with inflammatory and functional intestinal disorders. Pain. 1996;66:151–161. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blackburn-Munro G, Blackburn-Munro RE. Chronic pain, chronic stress and depression: coincidence or consequence? J. Neuroendocrinol. 2001;13:1009–1023. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1331.2001.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boulware MI, Weick JP, Becklund BR, Kuo SP, Groth RD, Mermelstein PG. Estradiol Activates Group I and II Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor Signaling, Leading to Opposing Influences on cAMP Response Element-Binding Protein. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:5066–5078. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1427-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyce VS, Mendell LM. Neurotrophins and spinal circuit function. Front Neural Circuits. 2014;8:59. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2014.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradesi S, Eutamene H, Garcia-Villar R, Fioramonti J, Bueno L. Stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity in female rats is estrogen-dependent and involves tachykinin NK1 receptors. Pain. 2003;102:227–234. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradesi S, Schwetz I, Ennes HS, Lamy CM, Ohning G, Fanselow M, Pothoulakis C, McRoberts JA, Mayer EA. Repeated exposure to water avoidance stress in rats: a new model for sustained visceral hyperalgesia. Am. J. Physiol Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G42–G53. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00500.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cairns BE, Sim Y, Bereiter DA, Sessle BJ, Hu JW. Influence of sex on reflex jaw muscle activity evoked from the rat temporomandibular joint. Brain Res. 2002;957:338–344. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03671-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao D-Y, Bai G, Ji Y, Traub R. Epigenetic upregulation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 2 in the spinal cord attenuates estrogen-induced visceral hypersensitivity. Gut. 2015;64:1913–1920. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao DY, Bai G, Ji Y, Karpowicz JM, Traub RJ. EXPRESS: Histone hyperacetylation modulates spinal type II metabotropic glutamate receptor alleviating stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity in female rats. Mol Pain. 2016;12 doi: 10.1177/1744806916660722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao DY, Ji Y, Tang B, Traub RJ. Estrogen Receptor beta Activation Is Antinociceptive in a Model of Visceral Pain in the Rat. J. Pain. 2012;13:685–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao J, Wang PK, Tiwari V, Liang L, Lutz BM, Shieh KR, Zang WD, Kaufman AG, Bekker A, Gao XQ, Tao YX. Short-term pre- and post-operative stress prolongs incision-induced pain hypersensitivity without changing basal pain perception. Mol. Pain. 2015;11:73. doi: 10.1186/s12990-015-0077-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cashman MD, Martin DK, Dhillon S, Puli SR. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Clinical Review. Curr. Rheumatol. Rev. 2016;12:13–26. doi: 10.2174/1573397112666151231110521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaloner A, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B. Sexually Dimorphic Effects of Unpredictable Early Life Adversity on Visceral Pain Behavior in a Rodent Model. J Pain. 2013;14:270–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandramohan Y, Droste SK, Arthur JS, Reul JM. The forced swimming-induced behavioural immobility response involves histone H3 phospho-acetylation and c-Fos induction in dentate gyrus granule neurons via activation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate/extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen- and stress-activated kinase signalling pathway. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:2701–2713. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J, Winston JH, Sarna SK. Neurological and cellular regulation of visceral hypersensitivity induced by chronic stress and colonic inflammation in rats. Neuroscience. 2013;248:469–478. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiechio S, Zammataro M, Morales ME, Busceti CL, Drago F, Gereau RW, Copani A, Nicoletti F. Epigenetic modulation of mGlu2 receptors by histone deacetylase inhibitors in the treatment of inflammatory pain. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009;75:1014–1020. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.054346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi JC, Chung MI, Lee YD. Modulation of pain sensation by stress-related testosterone and cortisol. Anaesthesia. 2012;67:1146–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2012.07267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Connor TJ, Kelly JP, Leonard BE. Forced swim test-induced neurochemical endocrine, and immune changes in the rat. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1997;58:961–967. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coull JA, Beggs S, Boudreau D, Boivin D, Tsuda M, Inoue K, Gravel C, Salter MW, De KY. BDNF from microglia causes the shift in neuronal anion gradient underlying neuropathic pain. Nature. 2005;438:1017–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature04223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craft RM, Mogil JS, Aloisi AM. Sex differences in pain and analgesia: the role of gonadal hormones. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:397–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deiteren A, de WA, van der Linden L, De Man JG, Pelckmans PA, De Winter BY. Irritable bowel syndrome and visceral hypersensitivity : risk factors and pathophysiological mechanisms. Acta Gastroenterol. Belg. 2016;79:29–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deiteren A, Vermeulen W, Moreels TG, Pelckmans PA, De Man JG, De Winter BY. The effect of chemically induced colitis, psychological stress and their combination on visceral pain in female Wistar rats. Stress. 2014;17:431–444. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2014.951034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong XD, Mann MK, Kumar U, Svensson P, Arendt-Nielsen L, Hu JW, Sessle BJ, Cairns BE. Sex-related differences in NMDA-evoked rat masseter muscle afferent discharge result from estrogen-mediated modulation of peripheral NMDA receptor activity. Neuroscience. 2007;146:822–832. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du J, Zhou S, Carlton SM. Group II metabotropic glutamate receptor activation attenuates peripheral sensitization in inflammatory states. Neuroscience. 2008;154:754–766. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duric V, McCarson KE. Neurokinin-1 (NK-1) receptor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene expression is differentially modulated in the rat spinal dorsal horn and hippocampus during inflammatory pain. Mol. Pain. 2007;3:32. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-3-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fanton LE, Macedo CG, Torres-Chavez KE, Fischer L, Tambeli CH. Activational action of testosterone on androgen receptors protects males preventing temporomandibular joint pain. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2017;152:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fereidoni M, Javan M, Semnanian S, Ahmadiani A. Chronic forced swim stress inhibits ultra-low dose morphine-induced hyperalgesia in rats. Behav. Pharmacol. 2007;18:667–672. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282f007cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL., III Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain. 2009;10:447–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fischer L, Torres-Chavez KE, Clemente-Napimoga JT, Jorge D, Arsati F, Arruda Veiga MC, Tambeli CH. The Influence of Sex and Ovarian Hormones on Temporomandibular Joint Nociception in Rats. J Pain. 2008;9:630–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fukudo S. Stress and Visceral Pain: Focusing on Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Pain. 2013;154:s63–s70. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garraway SM, Huie JR. Spinal Plasticity and Behavior: BDNF-Induced Neuromodulation in Uninjured and Injured Spinal Cord. Neural Plast. 2016;2016:9857201. doi: 10.1155/2016/9857201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gaumond I, Arsenault P, Marchand S. Specificity of female and male sex hormones on excitatory and inhibitory phases of formalin-induced nociceptive responses. Brain Res. 2005;1052:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerber G, Zhong J, Youn DH, Randic M. Group II and group III metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists depress synaptic transmission in the rat spinal cord dorsal horn. Neuroscience. 2000;100:393–406. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gray JM, Chaouloff F, Hill MN. To stress or not to stress: a question of models. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. 2015;70:8–22. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0833s70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Green CR, Corsi-Travali S, Neumeister A. The Role of BDNF-TrkB Signaling in the Pathogenesis of PTSD. J. Depress. Anxiety. 2013;2013 doi: 10.4172/2167-1044.S4-006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hare BD, Ghosal S, Duman RS. Rapid Acting Antidepressants in Chronic Stress Models: Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. Chronic. Stress. (Thousand. Oaks.) 2017;1 doi: 10.1177/2470547017697317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hildebrand ME, Xu J, Dedek A, Li Y, Sengar AS, Beggs S, Lombroso PJ, Salter MW. Potentiation of Synaptic GluN2B NMDAR Currents by Fyn Kinase Is Gated through BDNF-Mediated Disinhibition in Spinal Pain Processing. Cell Rep. 2016;17:2753–2765. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hong S, Fan J, Kemmerer ES, Evans S, Li Y, Wiley JW. Reciprocal changes in vanilloid (TRPV1) and endocannabinoid (CB1) receptors contribute to visceral hyperalgesia in the water avoidance stressed rat. Gut. 2009;58:202–210. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.157594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Imbe H, Kimura A. Repeated forced swim stress prior to complete Freund's adjuvant injection enhances mechanical hyperalgesia and attenuates the expression of pCREB and DeltaFosB and the acetylation of histone H3 in the insular cortex of rat. Neuroscience. 2015;301:12–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imbe H, Kimura A, Donishi T, Kaneoke Y. Repeated forced swim stress enhances CFA-evoked thermal hyperalgesia and affects the expressions of pCREB and c-Fos in the insular cortex. Neuroscience. 2014;259:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Imbe H, Okamoto K, Donishi T, Senba E, Kimura A. Involvement of descending facilitation from the rostral ventromedial medulla in the enhancement of formalin-evoked nocifensive behavior following repeated forced swim stress. Brain Res. 2010;1329:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.James KC, Nicholls PJ, Roberts M. Biological half-lives of [4–14C]testosterone and some of its esters after injection into the rat. J Pharm. Pharmacol. 1969;21:24–27. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1969.tb08125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ji Y, Tang B, Traub RJ. Spinal estrogen receptor alpha mediates estradiol-induced pronociception in a visceral pain model in the rat. Pain. 2011;152:1182–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ji Y, Bai G, Cao DY, Traub RJ. Estradiol modulates visceral hyperalgesia by increasing thoracolumbar spinal GluN2B subunit activity in female rats. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2015;27:775–786. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ji Y, Murphy AZ, Traub RJ. Estrogen modulates the visceromotor reflex and responses of spinal dorsal horn neurons to colorectal stimulation in the rat. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:3908–3915. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-09-03908.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ji Y, Tang B, Cao DY, Wang G, Traub RJ. Sex differences in spinal processing of transient and inflammatory colorectal stimuli in the rat. Pain. 2012;153:1965–1973. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ji Y, Traub RJ. Estrogen increases colorectal sensitivity in the rat by increasing NMDA receptor function. Soc for Neuroscience abstracts. 2002:451.4. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Joseph EK, Levine JD. Sexual dimorphism for protein kinase c epsilon signaling in a rat model of vincristine-induced painful peripheral neuropathy. Neuroscience. 2003;119:831–838. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karisetty BC, Joshi PC, Kumar A, Chakravarty S. Sex differences in the effect of chronic mild stress on mouse prefrontal cortical BDNF levels: A role of major ovarian hormones. Neuroscience. 2017;356:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Keefe KM, Sheikh IS, Smith GM. Targeting Neurotrophins to Specific Populations of Neurons: NGF, BDNF, and NT-3 and Their Relevance for Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18 doi: 10.3390/ijms18030548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lakshminarasimhan H, Chattarji S. Stress leads to contrasting effects on the levels of brain derived neurotrophic factor in the hippocampus and amygdala. PLoS. One. 2012;7:e30481. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Larauche M, Mulak A, Kim YS, Labus J, Million M, Tache Y. Visceral analgesia induced by acute and repeated water avoidance stress in rats: sex difference in opioid involvement. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2012;24:1031–e547. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01980.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee KS, Zhang Y, Asgar J, Auh QS, Chung MK, Ro JY. Androgen receptor transcriptionally regulates mu-opioid receptor expression in rat trigeminal ganglia. Neuroscience. 2016;331:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee UJ, Ackerman AL, Wu A, Zhang R, Leung J, Bradesi S, Mayer EA, Rodriguez LV. Chronic psychological stress in high-anxiety rats induces sustained bladder hyperalgesia. Physiol Behav. 2015;139:541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu W, Ge T, Leng Y, Pan Z, Fan J, Yang W, Cui R. The Role of Neural Plasticity in Depression: From Hippocampus to Prefrontal Cortex. Neural Plast. 2017;2017:6871089. doi: 10.1155/2017/6871089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ma B, Yu LH, Fan J, Cong B, He P, Ni X, Burnstock G. Estrogen modulation of peripheral pain signal transduction: involvement of P2X(3) receptors. Purinergic. Signal. 2011;7:73–83. doi: 10.1007/s11302-010-9212-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ma X, Bao W, Wang X, Wang Z, Liu Q, Yao Z, Zhang D, Jiang H, Cui S. Role of spinal GABA receptor reduction induced by stress in rat thermal hyperalgesia. Exp. Brain Res. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00221-014-4027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Macedo CG, Fanton LE, Fischer L, Tambeli CH. Coactivation of mu- and kappa-Opioid Receptors May Mediate the Protective Effect of Testosterone on the Development of Temporomandibular Joint Nociception in Male Rats. J. Oral Facial. Pain Headache. 2016;30:61–67. doi: 10.11607/ofph.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mannion RJ, Costigan M, Decosterd I, Amaya F, Ma QP, Holstege JC, Ji RR, Acheson A, Lindsay RM, Wilkinson GA, Woolf CJ. Neurotrophins: peripherally and centrally acting modulators of tactile stimulus-induced inflammatory pain hypersensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:9385–9390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mapplebeck JC, Beggs S, Salter MW. Molecules in pain and sex: a developing story. Mol. Brain. 2017;10:9. doi: 10.1186/s13041-017-0289-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Matrisciano F, Panaccione I, Grayson DR, Nicoletti F, Guidotti A. Metabotropic Glutamate 2/3 Receptors and Epigenetic Modifications in Psychotic Disorders: A Review. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2016;14:41–47. doi: 10.2174/1570159X13666150713174242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McEwen BS, Bowles NP, Gray JD, Hill MN, Hunter RG, Karatsoreos IN, Nasca C. Mechanisms of stress in the brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2015;18:1353–1363. doi: 10.1038/nn.4086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McEwen BS, Gray JD, Nasca C. 60 YEARS OF NEUROENDOCRINOLOGY: Redefining neuroendocrinology: stress, sex and cognitive and emotional regulation. J. Endocrinol. 2015;226:T67–T83. doi: 10.1530/JOE-15-0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Melchior M, Poisbeau P, Gaumond I, Marchand S. Insights into the mechanisms and the emergence of sex-differences in pain. Neuroscience. 2016;338:63–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Melemedjian OK, Tillu DV, Asiedu MN, Mandell EK, Moy JK, Blute VM, Taylor CJ, Ghosh S, Price TJ. BDNF regulates atypical PKC at spinal synapses to initiate and maintain a centralized chronic pain state. Mol. Pain. 2013;9:12. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-9-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Merighi A, Salio C, Ghirri A, Lossi L, Ferrini F, Betelli C, Bardoni R. BDNF as a pain modulator. Prog. Neurobiol. 2008;85:297–317. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moger WH. Effect of testosterone implants on serum gonadotropin concentrations in the male rat. Biol. Reprod. 1976;14:665–669. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod14.5.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moloney RD, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Strain-Dependent Variations in Visceral Sensitivity: Relationship to Stress, Anxiety and Spinal Glutamate Transporter Expression. Genes Brain Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1111/gbb.12216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Moloney RD, O'Mahony SM, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Stress-induced visceral pain: toward animal models of irritable-bowel syndrome and associated comorbidities. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:15. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mulak A, Tache Y, Larauche M. Sex hormones in the modulation of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:2433–2448. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i10.2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Niciu MJ, Ionescu DF, Richards EM, Zarate CA., Jr Glutamate and its receptors in the pathophysiology and treatment of major depressive disorder. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna.) 2014;121:907–924. doi: 10.1007/s00702-013-1130-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nijs J, Meeus M, Versijpt J, Moens M, Bos I, Knaepen K, Meeusen R. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor as a driving force behind neuroplasticity in neuropathic and central sensitization pain: a new therapeutic target? Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets. 2015;19:565–576. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2014.994506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Niswender CM, Conn PJ. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: physiology, pharmacology, and disease. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2010;50:295–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Novikova LN, Novikov LN, Kellerth JO. Survival effects of BDNF and NT-3 on axotomized rubrospinal neurons depend on the temporal pattern of neurotrophin administration. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000;12:776–780. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Numakawa T, Yokomaku D, Richards M, Hori H, Adachi N, Kunugi H. Functional interactions between steroid hormones and neurotrophin BDNF. World J Biol. Chem. 2010;1:133–143. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v1.i5.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Okamoto K, Tashiro A, Chang Z, Thompson R, Bereiter DA. Temporomandibular joint-evoked responses by spinomedullary neurons and masseter muscle are enhanced after repeated psychophysical stress. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2012;36:2025–2034. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Okamoto K, Thompson R, Katagiri A, Bereiter DA. Estrogen status and psychophysical stress modify temporomandibular joint input to medullary dorsal horn neurons in a lamina-specific manner in female rats. Pain. 2013;154:1057–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Olango WM, Finn DP. Neurobiology of stress-induced hyperalgesia. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2014;20:251–280. doi: 10.1007/7854_2014_302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pajot J, Ressot C, Ngom I, Woda A. Gonadectomy induces site-specific differences in nociception in rats. Pain. 2003;104:367–373. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Porsolt RD, Bertin A, Blavet N, Deniel M, Jalfre M. Immobility induced by forced swimming in rats: effects of agents which modify central catecholamine and serotonin activity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1979;57:201–210. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(79)90366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Porsolt RD, Le PM, Jalfre M. Depression: a new animal model sensitive to antidepressant treatments. Nature. 1977;266:730–732. doi: 10.1038/266730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Quintero L, Cardenas R, Suarez-Roca H. Stress-induced hyperalgesia is associated with a reduced and delayed GABA inhibitory control that enhances post-synaptic NMDA receptor activation in the spinal cord. Pain. 2011;152:1909–1922. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Quintero L, Cuesta MC, Silva JA, Arcaya JL, Pinerua-Suhaibar L, Maixner W, Suarez-Roca H. Repeated swim stress increases pain-induced expression of c-Fos in the rat lumbar cord. Brain Res. 2003;965:259–268. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Quintero L, Moreno M, Avila C, Arcaya J, Maixner W, Suarez-Roca H. Long-lasting delayed hyperalgesia after subchronic swim stress. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2000;67:449–458. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ren TH, Wu J, Yew D, Ziea E, Lao L, Leung WK, Berman B, Hu PJ, Sung JJ. Effects of neonatal maternal separation on neurochemical and sensory response to colonic distension in a rat model of irritable bowel syndrome. Am. J. Physiol Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G849–G856. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00400.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Reul JM. Making memories of stressful events: a journey along epigenetic, gene transcription, and signaling pathways. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:5. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Robbins MT, Mebane H, Ball CL, Shaffer AD, Ness TJ. Effect of estrogen on bladder nociception in rats. J. Urol. 2010;183:1201–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Simren M, Abrahamsson H, Bjornsson ES. An exaggerated sensory component of the gastrocolonic response in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2001;48:20–27. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sohrabji F, Lewis DK. Estrogen-BDNF interactions: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2006;27:404–414. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sommerville EM, Tarttelin MF. Plasma testosterone levels in adult and neonatal female rats bearing testosterone propionate-filled silicone elastomer capsules for varying periods of time. J Endocrinol. 1983;98:365–371. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0980365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Spooner MF, Robichaud P, Carrier JC, Marchand S. Endogenous pain modulation during the formalin test in estrogen receptor beta knockout mice. Neuroscience. 2007;150:675–680. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Suarez-Roca H, Leal L, Silva JA, Pinerua-Shuhaibar L, Quintero L. Reduced GABA neurotransmission underlies hyperalgesia induced by repeated forced swimming stress. Behav. Brain Res. 2008;189:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Suarez-Roca H, Silva JA, Arcaya JL, Quintero L, Maixner W, Pinerua-Shuhaibar L. Role of mu-opioid and NMDA receptors in the development and maintenance of repeated swim stress-induced thermal hyperalgesia. Behav. Brain Res. 2006;167:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Swarbrick ET, Hegarty JE, Bat L, Williams CB, Dawson AM. Site of pain from the irritable bowel. Lancet. 1980;2:443–446. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91885-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tang B, Ji Y, Traub RJ. Estrogen alters spinal NMDA receptor activity via a PKA signaling pathway in a visceral pain model in the rat. Pain. 2008;137:540–549. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Trang T, Beggs S, Salter MW. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor from microglia: a molecular substrate for neuropathic pain. Neuron Glia Biol. 2011;7:99–108. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X12000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Traub RJ. Evidence for thoracolumbar spinal cord processing of inflammatory, but not acute colonic pain. NeuroReport. 2000;11:2113–2116. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200007140-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Traub RJ, Cao DY, Karpowicz J, Pandya S, Ji Y, Dorsey SG, Dessem D. A clinically relevant animal model of temporomandibular disorder and irritable bowel syndrome comorbidity. J Pain. 2014;15:956–966. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Traub RJ, Ji Y. Sex differences and hormonal modulation of deep tissue pain. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2013;34:350–366. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ulmann L, Hatcher JP, Hughes JP, Chaumont S, Green PJ, Conquet F, Buell GN, Reeve AJ, Chessell IP, Rassendren F. Up-regulation of P2X4 receptors in spinal microglia after peripheral nerve injury mediates BDNF release and neuropathic pain. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:11263–11268. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2308-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Unruh AM. Gender variations in clinical pain experience. Pain. 1996;65:123–167. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Vagell ME, McGinnis MY. The role of aromatization in the restoration of male rat reproductive behavior. J Neuroendocrinol. 1997;9:415–421. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1997.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wang G, Tang B, Traub RJ. Differential processing of noxious colonic input by thoracolumbar and lumbosacral dorsal horn neurons in the rat. J. Neurophysiol. 2005;94:3788–3794. doi: 10.1152/jn.00230.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wang G, Tang B, Traub RJ. Pelvic nerve input mediates descending modulation of homovisceral processing in the thoracolumbar spinal cord of the rat. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1544–1553. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Weishaupt N, Blesch A, Fouad K. BDNF: the career of a multifaceted neurotrophin in spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 2012;238:254–264. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.White HD, Robinson TD. A novel use for testosterone to treat central sensitization of chronic pain in fibromyalgia patients. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015;27:244–248. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wilson MA, Grillo CA, Fadel JR, Reagan LP. Stress as a one-armed bandit: Differential effects of stress paradigms on the morphology, neurochemistry and behavior in the rodent amygdala. Neurobiol. Stress. 2015;1:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Winston JH, Li Q, Sarna SK. Chronic prenatal stress epigenetically modifies spinal cord BDNF expression to induce sex-specific visceral hypersensitivity in offspring. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2014 doi: 10.1111/nmo.12326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wu D, Gore AC. Changes in androgen receptor, estrogen receptor alpha, and sexual behavior with aging and testosterone in male rats. Horm. Behav. 2010;58:306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yang PC, Jury J, Soderholm JD, Sherman PM, McKay DM, Perdue MH. Chronic psychological stress in rats induces intestinal sensitization to luminal antigens. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;168:104–114. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zhang Y, Xiao X, Zhang XM, Zhao ZQ, Zhang YQ. Estrogen facilitates spinal cord synaptic transmission via membrane-bound estrogen receptors: implications for pain hypersensitivity. J Biol. Chem. 2012;287:33268–33281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.368142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.