Abstract

Viral infections continue to represent major public health challenges, demanding enhanced mechanistic understanding of the processes contributing to viral lifecycles for the realization of new therapeutic strategies1. Viperin, a member of the radical S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) superfamily of enzymes, is an interferon inducible protein implicated in inhibiting the replication of a remarkable range of RNA and DNA viruses, including dengue virus, West Nile virus, hepatitis C virus, influenza A virus, rabies virus2 and HIV3,4. Viperin has been suggested to elicit these broad antiviral activities through interactions with a large number of functionally unrelated host and viral proteins3,4. In contrast, herein, we demonstrate that viperin catalyzes the conversion of cytidine triphosphate (CTP) to 3′-deoxy-3′,4′-didehydro-CTP (ddhCTP), a previously undescribed biologically relevant molecule, via a SAM-dependent radical mechanism. We show that mammalian cells expressing viperin, and macrophages stimulated with IFN-α, produce substantial quantities of ddhCTP. We also establish that ddhCTP acts as a chain terminator for the RNA-dependent RNA-polymerases from multiple members of the flavivirus family, and present evidence that ddhCTP directly inhibits in vivo replication of ZIKA virus. These findings suggest a partially unifying mechanism, based on intrinsic catalytic/enzymatic properties, for the broad antiviral effects of viperin, which involves the generation of a naturally occurring replication chain terminator encoded by mammalian genomes.

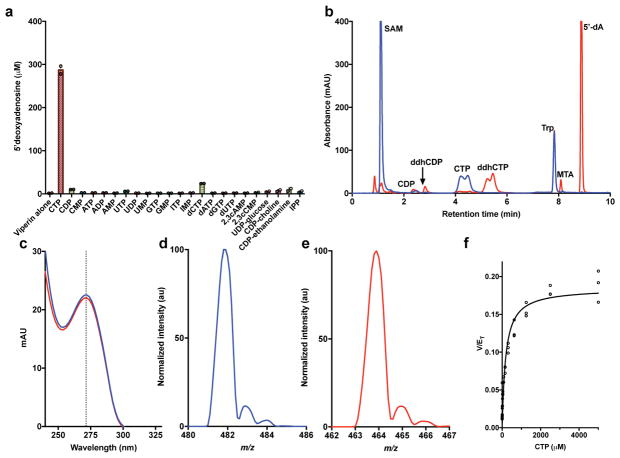

Consideration of genome context shows that in vertebrates viperin is always immediately adjacent to a gene annotated as cytidylate monophosphate kinase 2 (CMPK2) and in lower organisms these two genes are sometimes fused (Extended Data Fig. 1a). These observations suggested that viperin might modify a nucleotide. Evaluation of approximately two hundred constructs identified a Rattus norvegicus viperin spanning the radical SAM (RS) catalytic domain (Rvip: residues 51–361), which exhibited excellent solution properties (Extended Data Fig. 1b, c). We screened Rvip against a diverse set of nucleotides and deoxynucleotides, looking for enhanced 5′-deoxyadenosine (5′dA) formation as an indicator of substrate activation (See Supporting Information for details). Like most other RS proteins, when provided with dithionite as an artificial electron donor, Rvip performs reductive cleavage of SAM in the absence of substrates. As shown in Figure 1a, CTP selectively activates 5′dA production by ~130-fold relative to protein alone. Liquid chromatography (LC) shows that in addition to 5′dA (9.1 min), another product is present (5.2 min) (Fig. 1b), which exhibits a UV-visible spectrum similar to CTP (λmax = 271 nm), indicating that the pyrimidine ring is not dramatically modified by the viperin-mediated reaction (Fig. 1c). LC-coupled mass spectrometry (LC-MS) showed the new compound exhibited a negative ion mass to charge ratio (−m/z) of 464.1, which is 18 Da less than the −m/z of 482.1 of CTP (Fig. 1d,e).

Figure 1. Substrate specificity of viperin.

a, A panel of nucleotides was mixed with Rvip and SAM, and the resulting 5′-dA measured (n=2 independent experiments). b, HPLC analysis showing viperin-mediated conversion of CTP to new product (time = 0, blue; time = 45 min, red). c, UV-visible spectrum of CTP (blue) and new product (ddhCTP, red). Absorbance maximum at 271nm (dotted line). d, MS for CTP (blue, −m/z = 482.1) and e, ddhCTP (red, −m/z = 464.1). All results have been repeated at least 3 times. f, Kinetic analysis of rVIP with CTP: Km for CTP = 182.8 ± 27.6 μM and Vmax = 0.185 ± 0.007 min−1 (n = 3 independent experiments, mean ± S.D).

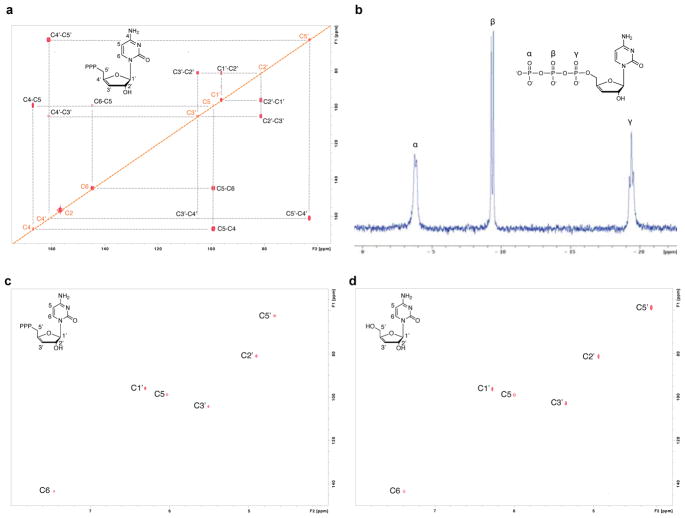

13C-13C COSY NMR on uniformly labeled 13C9,15N3-viperin product, and 1H-13C 2D HSQC chemical shift analysis and 31P NMR analysis on natural abundance viperin product were performed (see Methods for details, Extended Data Figs. 1d and 2; see Supplementary Table 1 for chemical shift data). Taken together, all available NMR and MS data are consistent with the Rvip-catalyzed conversion of CTP to 3′-deoxy-3′,4′-didehydro-cytidine triphosphate (ddhCTP), where dehydration, involving loss of both the 4′–hydrogen and the 3′ hydroxyl group, occurs without rearrangement of the carbon skeleton. It is notable that MoaA, which catalyzes the conversion of GTP to (8S)-3′,8-cyclo-7,8-dihydroguanosine 5′-triphosphate5, is the enzyme with the highest sequence similarity to viperin for which an unambiguous functional annotation exists. Additionally, the recent report of the structure of viperin from Mus musculus proposed that the presumptive catalytic site shares high amino acid conservation with MoaA and may operate on a nucleotide-like substrate6. These observations are consistent with the above data.

Rvip has a Km of 183 ± 28 μM for CTP and produces ddhCTP with a maximum velocity of 0.185 ± 0.007 min−1 (Fig. 1f). The intracellular concentration of CTP typically falls in the 1 mM range, which agrees well with the Km obtained for Rvip for CTP7, and the rate of ddhCTP formation is consistent with that of other RS enzymes with their native substrates8. 5′dA and ddhCTP production is tightly coupled, with one molecule of 5′dA generated for every ddhCTP (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Rvip also produces ddhCTP when the reaction is initiated by an enzymatic reducing system, indicating that dithionite does not direct an unanticipated side reaction between Rvip and CTP (Extended Data Fig. 3b).

A recent report described an RS enzyme from the thermophilic fungus Thielavia terrestris (58% sequence identity to human viperin) that was capable of catalyzing the coupling of UDP-glucose and 5′dA to generate an uncharacterized product with a m/z of 818.19. In addition, a preliminary report suggested that viperin homologs from Methanofollis liminatans (Achaea, 35% sequence identity to human viperin) and Trichoderma virens (Fungi, 55% identity) catalyze the radical-based condensation of 5′dA and isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) to yield adenylated isopentyl pyrophosphate10. Substrate activation and competition assays demonstrate that mammalian viperin does not catalyze these transformations (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 3c–f). We therefore conclude that UDP-glucose and IPP are not likely physiological substrates for mammalian viperins; although it remains a possibility that lower eukaryotes utilize viperin homologs to perform distinct functions. Analogous competition experiments demonstrated that deoxyCTP is also not a substrate Rvip (Extended Data Fig. 3g).

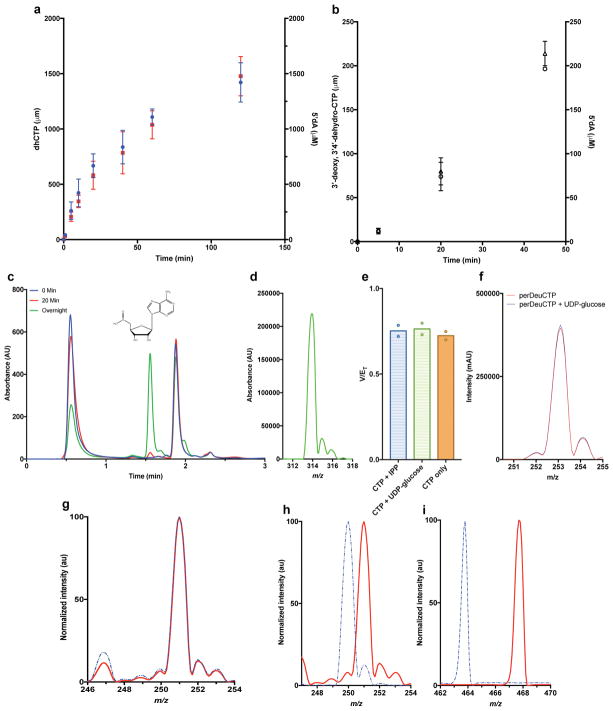

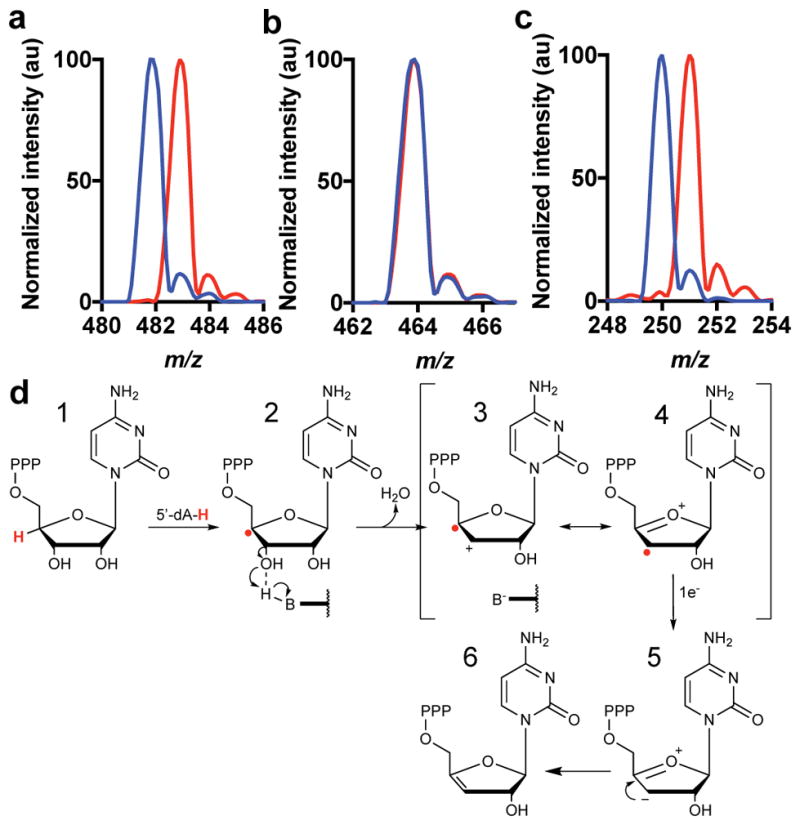

Incubation of Rvip with SAM and CTP deuterated at the 2′, 3′, 4′, 5′ and 5 positions (deuCTP), increased the −m/z of 5′dA from 250.1 to 251.1, consistent with the transfer of one deuterium from deuCTP to 5′dA. Additionally, ddhCTP from this reaction exhibited a −m/z of 468.1, indicating that the deuterium abstracted by 5′dA did not return to the product (Extended Data Fig. 3h,i). Site specifically deuterated CTP derivatives demonstrated that 5′dA• initiates chemistry by uniquely abstracting the hydrogen from the 4′-position of CTP (see Methods, Extended Data Figs. 2 and 4). Based on this observation, a provisional mechanism is outlined in Figure 2d, in which viperin utilizes the 5′dA• to abstract the hydrogen atom at the 4′-position of the ribose of CTP, subsequently allowing for loss of the 3′-hydroxyl group with general acid assistance. The resulting resonance stabilized radical cation is then reduced by one electron to yield the designated product. This mechanism has precedent from model studies of the radiolytic cleavage of single stranded DNA, wherein generation of a 4′-deoxyribosyl radical causes heterolytic dissociation of the 3′ phosphate group, resulting in a 3′-cation-4′-yl radical11. The source of the additional electron needed to reduce intermediate 3 (or 4) in the viperin-catalyzed reaction is currently unclear; however, we propose that, similar to other RS enzyme reactions12, the electron likely derives from a reduced 4Fe-4S cluster, suggesting that viperin requires two electrons to complete each turnover: one to generate the 5′dA• and another to reduce intermediate 3 (or 4).

Figure 2. Proposed mechanism for formation of ddhCTP.

a, m/z of CTP (blue) or 4′-2H -CTP (red). b, MS of ddhCTP from reactions with either CTP (blue), or 4′-2H -CTP (red) and Rvip. Deuterium from 4′-2H -CTP is not retained in ddhCTP as products have the same −m/z 464.1. c, 5′-dA derived from 4′-2H -CTP (red trace) increases by one mass unit due to the incorporation of deuterium. These experiments have been repeated at least 3 times with similar results. d, Following hydrogen atom abstraction at the 4′ position of CTP, general base-assisted loss of the 3′ hydroxyl group leads to a carbocation/radical intermediate that is reduced by 1e− to yield the ddhCTP product.

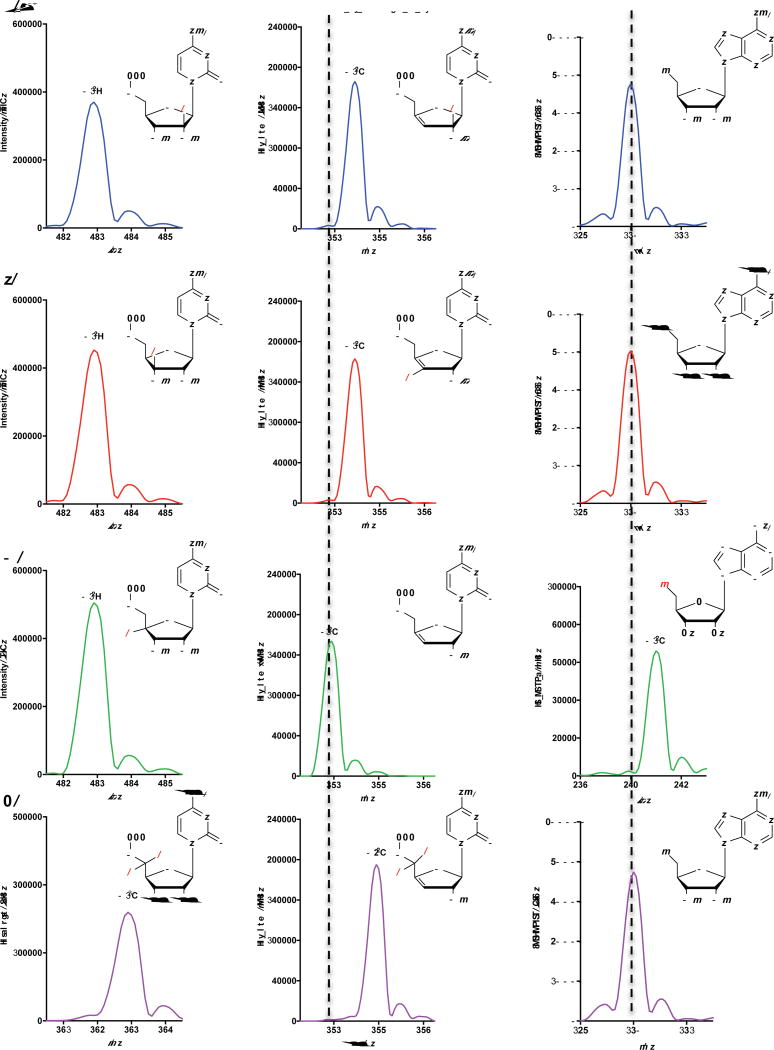

CMPK2 is always immediately adjacent to viperin in vertebrate genomes, and is cotranscribed with viperin during IFN stimulation13, suggesting a functional linkage. Human (Hs) CMPK2 was previously reported to catalyze the ATP-dependent phosphorylation of CMP, UMP, and dCMP to the corresponding diphosphates14. In contrast, we find that Hs CMPK2 exhibits significant preference for CDP and UDP as substrates, yielding CTP and UTP, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 5a). Notably, when provided ddhCDP, Hs CMPK2 displayed a 10-fold lower activity for producing ddhCTP when compared to the rate of CTP and UTP formation (Extended Data Fig. 5a, Supplementary Table 2). Therefore, based on the synteny and coordinated expression of viperin and CMPK2, and the available biochemical data, we propose that CMPK2 primarily functions to ensure sufficient substrate (i.e., CTP produced from CDP, or by CTP synthetase acting on UTP) for viperin-mediated production of ddhCTP during viral infection.

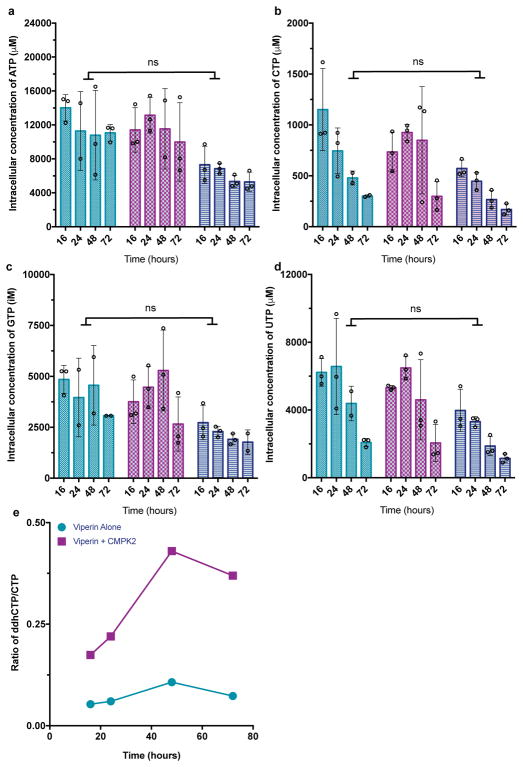

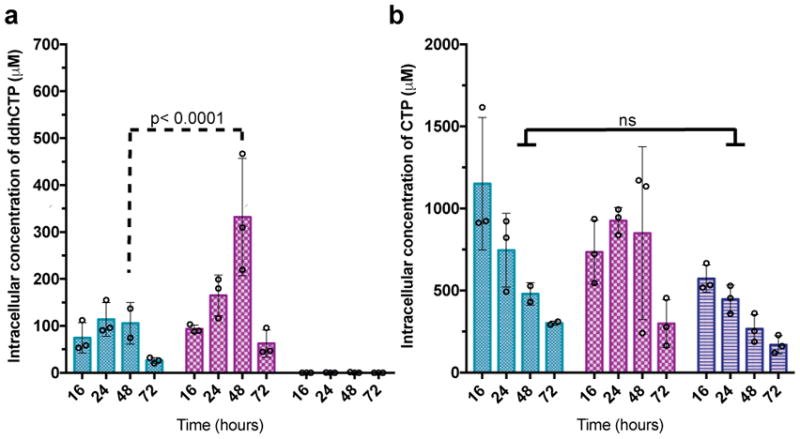

To demonstrate ddhCTP can be produced in mammalian cytosol, we generated a series of Hs viperin (83% identical to Rvip) and Hs CMPK2 expression constructs for transient transfection in HEK293T cells (Supplemenary Table 3, Extended Data Fig. 5b). As HEK293T cells do not express viperin in the presence or absence of IFN15, ddhCTP production would not be expected in the absence of exogenous viperin expression. HEK293T cells were transfected with a control plasmid, Hs viperin alone, Hs CMPK2 alone, or both Hs viperin and Hs CMPK2, and harvested at defined times for LC/MS analysis (see Methods and Supplementary Information for details). In all cases, over a 72-hr time course, the overall nucleotide pool consistently decreases, likely due to limiting nutrient levels, though the overall growth and cell viability are not impacted (Supplementary Table 4). In addition, at each time-point there are no statistically significant differences in total nucleotide concentrations between the control, Hs viperin, and Hs viperin/Hs CMPK2 treated cells (Extended Data Fig. 6a–d). Notably, HEK293T cells transfected with control plasmid exhibited ddhCTP levels below our limit of detection of ~400 fmol (Fig. 3a, right), while HEK293T cells transfected with the Hs viperin plasmid exhibited considerable intracellular ddhCTP levels: ~75 μM at 16 hr post transfection (Fig. 3a, left), which decreases to ~35 μM after 72 hr. Cotransfection with Hs viperin and Hs CMPK2 plasmids resulted in a ~4-fold increase in the amount of ddhCTP to ~330 μM at 48 hr (Fig. 3a, middle, maroon, p <0.0001). Moreover, coexpression of Hs viperin and Hs CMPK2 causes the ratio of ddhCTP to CTP concentrations to increase over time, while overexpression of Hs viperin alone results in a constant ratio of ddhCTP to CTP (Extended Data Fig. 6e). This behavior may allow viperin to continue generating ddhCTP even though ~30% of the total cellular pool of cytidine triphosphates is present as ddhCTP at 48 hr. These observations demonstrate that in vivo viperin is essential for production of ddhCTP, and suggest that CMPK2 may function to ensure that CTP is not limiting in the presence of viperin.

Figure 3. Expression of viperin in HEK293 cells produces ddhCTP.

a, Cells expressing Hs viperin (aqua), Hs viperin and Hs CMPK2 (maroon), or empty vector (dark blue). Analysis of ddhCTP formation indicates that the Hs viperin + Hs CMPK2 cells show a statistically significant increase in ddhCTP formation over viperin alone at 48 hr post transfection. In cells with empty vector, ddhCTP levels were undetectable. b, Intracellular concentrations of CTP did not differ significantly (ns) over time (n = 3 biologically independent samples, mean ± S.D., two-way ANOVA, Tukey post-hoc).

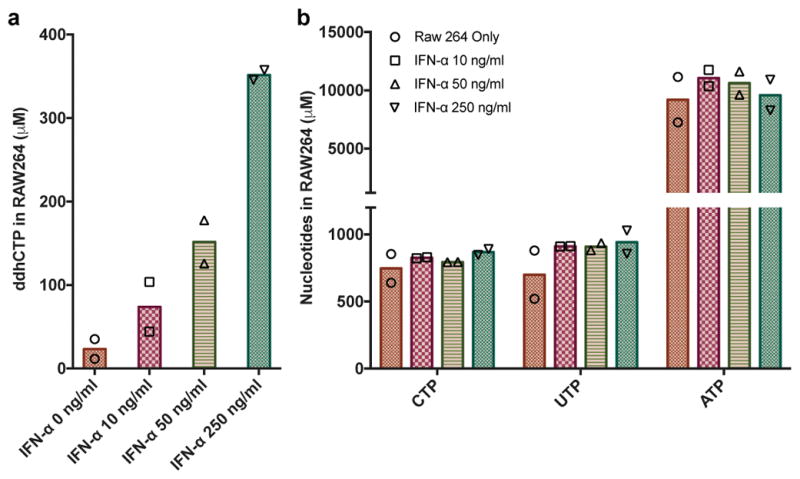

It is well documented that viperin expression can be robustly induced in immune cells by interferon, lipopolysaccharide and double-stranded RNA analogues16. Therefore, we cultured immortalized murine macrophages (RAW264.7) in the absence or presence of IFN-α in serum free media, as it has been previously shown that RAW264.7 express viperin in an IFN-α-sensitive fashion17. When harvested after 19 hr, the concentration of ddhCTP was shown to be highly dependent on the concentration of IFN-α (Extended Data Fig. 7a). RAW264.7 cells cultured in the presence of 250 ng/mL IFN-α generated intracellular concentrations of ddhCTP reaching nearly 350 μM, while the intracellular concentrations of ATP, UTP and CTP, were unaltered (Extended Data Fig. 7b). Analogous to the behavior observed in HEK293T cells cotransfected with Hs viperin and Hs CMPK2, treatment of RAW264.7 cells with 250 ng/mL IFN-α resulted in ddhCTP representing a sizable proportion (i.e., 30%) of the total cytidine triphosphate pool (ddhCTP (~350 μM) to CTP (~800 μM)), while the level of CTP remained unchanged. This behavior suggests that the viperin-mediated inhibition of viral replication is not the consequence of the limitation of the available pool of intracellular CTP, or other nucleotides, but rather is dependent on the generation of relevant concentrations of ddhCTP.

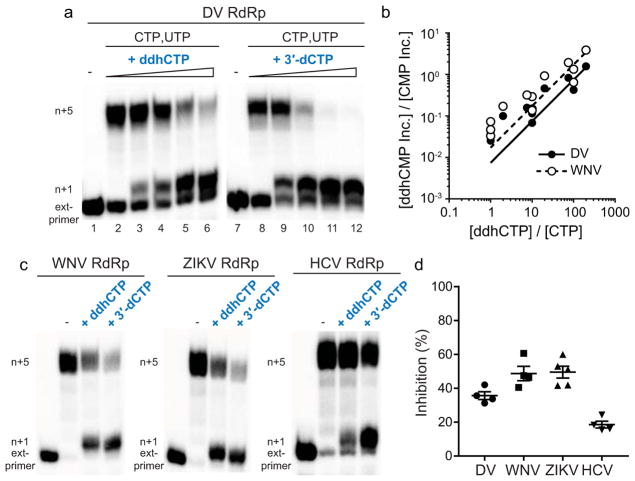

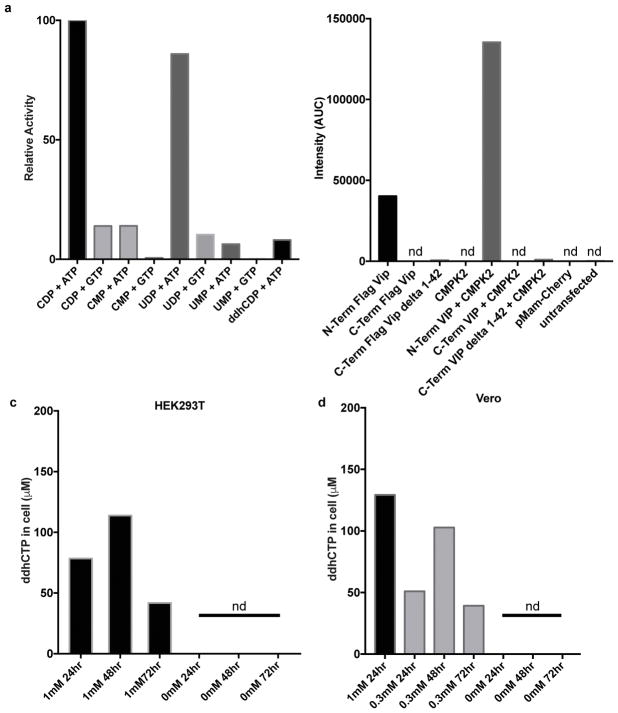

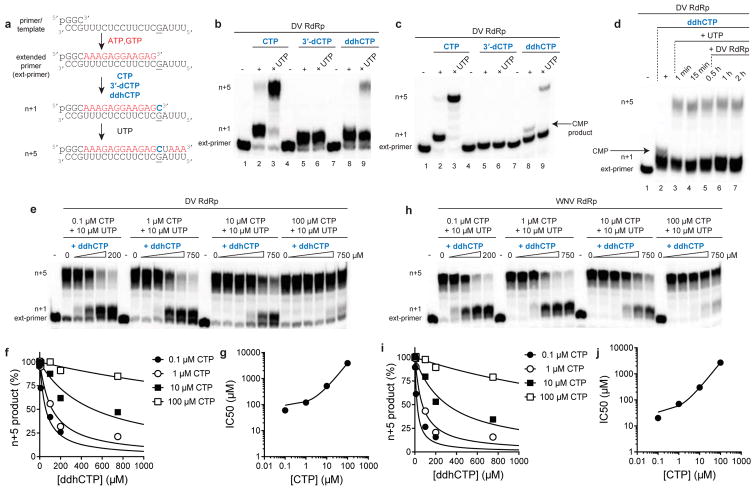

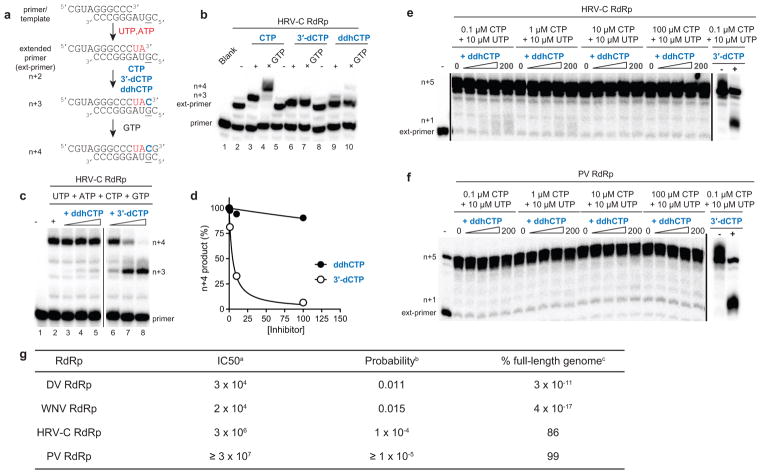

Because members of the Flavivirus family are known to be sensitive to the catalytic activity of viperin,18 and the resemblance of ddhCTP to known polymerase chain terminators, we examined the effect of ddhCTP on dengue virus (DV) RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) activity. First, we demonstrated that ddhCTP is a substrate for DV RdRp using a primed-template assay (Extended Data Fig. 8a,b)19. Addition of CTP, 3′-dCTP or ddhCTP led to incorporation of all of these nucleotides (Extended Data Fig. 8b). Addition of UTP to the CMP-incorporated RNA, as expected, led to further extension to the end of template (Extended Data Fig. 8b, c). However, addition of UTP to the 3′-dCMP- or ddhCMP-incorporated RNA did not support robust extension (Extended Data Fig. 8b,c), as expected for the action of chain terminators. A more stringent test of the effectiveness of a chain terminator is direct competition with natural ribonucleotides. Therefore, we evaluated RNA synthesis in the presence of increasing concentrations of ddhCTP or 3′-dCTP (Fig. 4a). Both ddhCTP and 3′dCTP were incorporated and inhibited production of full-length RNA (Fig. 4a). Additionally, by titrating ddhCTP at different concentrations of CTP we determined the relative efficiency of utilization of ddhCTP compared to CTP for DV RdRp, as well as the RdRp from West Nile Virus (WNV), another pathogenic flavivirus (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 8e–j). This analysis yielded a 135- and 59-fold difference in utilization of ddhCTP relative to CTP for DV and WNV RdRps, respectively. We also evaluated two additional members of the Flavivirus family, Zika virus (ZIKV) and HCV RdRps. Both of these RdRps were susceptible to inhibition by ddhCTP utilization and chain termination (Fig. 4c,d), consistent with studies demonstrating the antiviral activity of viperin against these viruses20–22. These data suggest that the flavivirus RdRps would be susceptible to inhibition by ddhCTP during replication (Extended Data Fig. 9g). Given the efficiency of utilization and genome size, it is calculated that even a ~1% probability of incorporating the ddhCTP chain terminator during replication would result in significant reduction of full-length genomes (Extended Data Fig. 9g). To determine if our observations with the flavivirus RdRps extend to RdRps from other supergroups, we evaluated members of supergroup I. Specifically, we used the RdRps from human rhinovirus type C (HRV-C) and poliovirus (PV), members of the Picornavirus family (Extended Data Fig. 9). Direct-incorporation experiments revealed utilization of both ddhCTP and 3′-dCTP by HRV-C RdRp (Extended Data Fig. 9b). However, in the presence of other rNTPs, both HRV-C and PV RdRp were poorly inhibited by ddhCTP (Extended Data Fig. 9c–f), even though both are inhibited by 3′-dCTP. Based on the above data, we conclude that not all RdRps are sensitive to ddhCTP, suggesting that different viruses will exhibit a range of susceptibilities to viperin expression in vivo.

Figure 4. ddhCTP inhibits Flavivirus RdRps by a chain termination mechanism.

a, ddhCTP (0, 1, 10, 100 and 300 μM) inhibits DV RdRp. Experiments repeated independently four times with similar results. b, Plot of [ddhCMP Inc.] / [CMP Inc.] versus [ddhCTP] / [CTP]. Data fit to a line with slope of 0.0074 ± 0.0006 (DV) and 0.017 ± 0.002 (WNV). At each ratio of [ddhCTP] /[CTP] a total of at least 3 independent experiments, with total sample size of 24. c, Inhibition of WNV, ZV and HCV RdRps with either ddhCTP or 3′-dCTP (100 μM). Experiments repeated independently four to five times with similar results. d, Percentage of inhibition shown. Error bars represent SEM (n = 4 independent experiments).

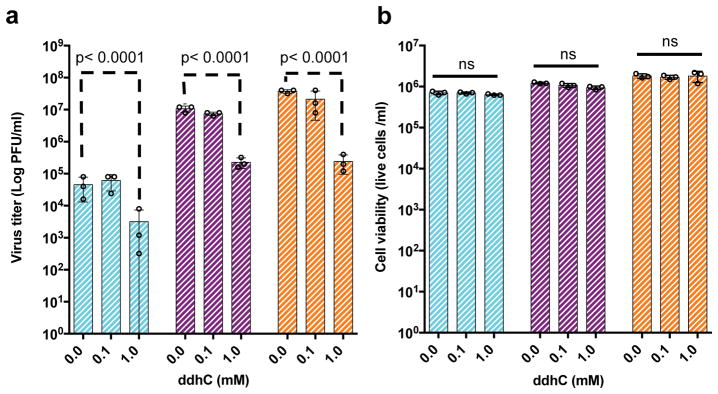

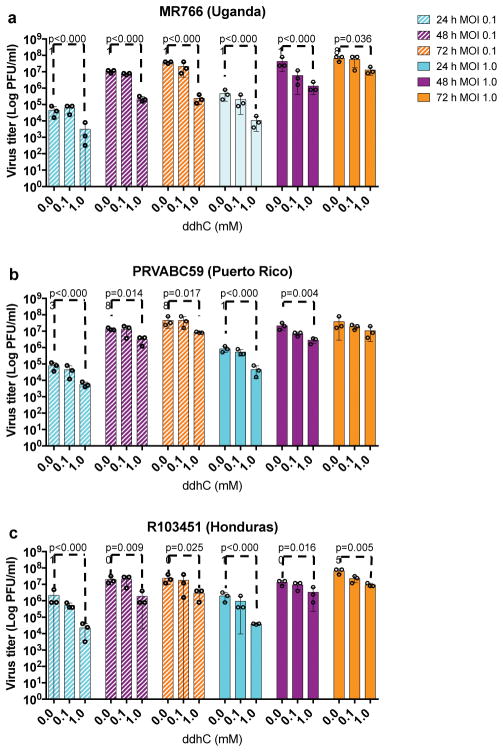

The above in vitro enzymatic characterizations suggest that ddhCTP would be sufficient for the in vivo inhibition of viral replication. First, we demonstrated that synthetic ddhC nucleoside was capable of traversing the plasma membrane of Vero and HEK293T cells and being metabolized to yield significant levels of ddhCTP (1mM synthetic ddhC resulted in the intracellular accumulation of 129 μM and 78 μM ddh-CTP after 24 hr, respectively) (Extended Data Fig. 5c,d). Next, we used the historical African strain MR766 (Uganda 1947)23 and two contemporary strains PRVABC59 (Puerto Rico; 2015)24 and R103451 (Honduras; 2016, GenBank: KX262887) to evaluate the antiviral activity of ddhC towards ZIKV replication and release from Vero cells. Treatment with ddhC resulted in a 1–2 orders of magnitude reduction in ZIKV virus titers, which was dependent on dose, MOI, duration of infection and strain (Supplementary Table 5). For example, at an MOI of 0.1, we observed 50–200-fold reduction in virus titer for ZIKV MR766 at all time points (Fig. 5a), with reductions of 5–50-fold also being observed at MOI of 1.0 (Extended Data Fig. 10a). ZIKV R103451 (Honduras) and ZIKV PRVABC59 (Puerto Rico) exhibited analogous sensitivities to ddhC treatment (Supplementary Table 5 and Extended Data Fig. 10a–c). The reduction in viral release was not a result of ddhC cytotoxicity, as incubation with 1 mM ddhC did not alter Vero cell viability (Fig. 5b, see Supplementary Information for details). These results, taken together with the above in vitro enzymatic analyses, are consistent with a model in which ddhC-derived ddhCTP inhibits viral replication through premature chain termination of RdRp products.

Figure 5. ddhC reduces ZIKV release in Vero cells.

a, Vero cells were treated with increasing concentrations of ddhC for 24 hr and infected with ZIKV MR766 (Uganda) at an MOI 0.1. b, For viability studies, Vero cells were treated with increasing concentrations of ddhC under the same culture conditions used for the antiviral experiment described in a. (n = 3 biologically independent samples, mean ± S.D., two-way ANOVA and a Dunnett post-hoc analysis).

Of the hundreds of genes stimulated by IFN, most appear to function as negative effectors of viral activity, though their mechanisms of action remain to be defined. Herein, we propose a new paradigm for the antiviral function of viperin, which relies on its intrinsic catalytic activity to generate ddhCTP, a previously undescribed replication chain terminator. To our knowledge, viperin is the only human protein that produces a small molecule capable of directly inhibiting viral replication machinery. Importantly, overexpression of viperin and production of ddhCTP does not appear to adversely affect the growth rate or viability of HEK293T or Vero cells. This observation indicates that the host RNA/DNA polymerases are not negatively impacted by ddhCTP and have developed protective mechanisms to exclude incorporation or excise this compound during nucleic acid synthesis; mechanistic studies on the utilization of ddhCTP by host polymerases will be an important area for future investigation. In addition to its inhibitory effect on viral RdRp activity, it is possible that viperin possesses additional antiviral functions. For example, despite reports that HRV infection induces viperin expression, ddhCTP does not appear to act as an effective chain terminator for the HRV RdRp25. Furthermore, in the case of human cytomegalovirus, viperin expression results in enhanced infectivity, possibly through alterations in cellular metabolism and disruption of the actin cytoskeleton26. It is likely that different pathogens are responsive to distinct subsets of the IFN-inducible genes, and given its range of viral modulatory effects, that viperin synergizes with other host- and pathogen-encoded genes.

Extended Data

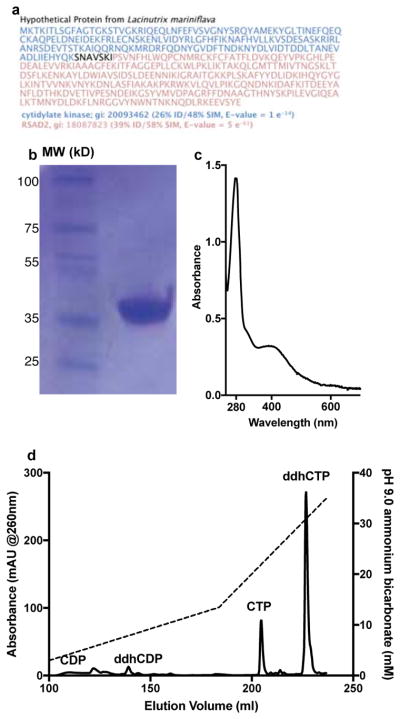

Extended data 1. Purification of Rvip and ddhCTP.

a, Amino acid sequence from Lacinutrix mariniflava fusion gene product of CMPK2- and viperin-like protein. b, SDS-PAGE analysis following affinity and size-exclusion chromatography. The protein corresponding to amino acid residues 51–361 has a predicted M.W. of 38.36 kDa. This construct was chosen because ~ 100 mg of protein could be purified from a 2 L fermentation. Also, the protein is soluble to concentration > 2 mM. c, UV-visible spectrum of purified Rvip (29.5 μM, UV 280/400 ratio of 4.2). d, Purification of ddhCTP using an ammonium bicarbonate, pH 9, with an elution gradient (dashed line) from 0.2M to 0.8M over 200 column volumes. All results have been repeated at least 3 times.

Extended data 2. NMR spectroscopy of ddhCTP.

a, 13C-13C COSY spectrum of 13C915N3-ddhCTP. The assignments for the observed correlations of the 13C-connectivities are indicated with the grey dotted lines. b, 31P NMR spectra (300MHz) of ddhCTP (1mM) in D2O at 300 K. Three resonance peaks at −19.5- (triplet), −9.5- (doublet) and −3.9- (doublet) p.p.m., correspond to the beta, alpha, and gamma phosphates of ddhCTP, respectively. c, 2D-HSQC NMR spectra collected on purified 1mM ddhCTP in D2O. d, 2D-HSQC NMR spectra collected on 1mM synthetic ddh-cytidine in D2O. All experiments have been repeated twice.

Extended data 3. Rvip produces a 1:1 stoichiometry of 5′dA and ddhCTP and reacts specifically with CTP.

a, Formation of ddhCTP (red squares) and 5′dA (blue circles) from CTP and SAM in the presence of dithionite and 100 μM RVip. ddhCTP is formed at roughly stoichiometric amounts with that of 5′dA. Error bars represent the mean ± SD of three replicates. b, Formation of ddhCTP (open triangle,) and 5′dA (open circle), from CTP and SAM in the presence of the flavodoxin, flavodoxin reductase and NADPH by 100 μM Rvip. Error bars represent the mean ± SD of three replicates. ddhCTP and 5′-dA is formed at roughly stoichiometric concentrations. The production of ddhCTP with this enzyme-driven reducing system indicates that ddhCTP formation is not the consequence of a side reaction with dithionite. c, HPLC analysis (0 minutes, blue trace; 20 minutes, red trace; 12 hours, green trace) showing the generation of a new peak at 1.55 min in the 12 hour sample corresponding to a 5′dA-dithionite adduct in the presence of 100 μM Rvip, 1mM SAM and 10 mM IPP. d, Corresponding mass spectra in ESI negative mode of peak occurring at 1.55 minutes in the 12 hours sample. The 5′dA-dithionite conjugate was calculated to have an exact mass of 315 Da and an m/z of 314.1. These results have been repeated twice. e, Rate of 5′dA formed by 100 μM Rvip in the presence of 1mM SAM, 1mM CTP and/or 10mM IPP or UDP-glucose (n = 3 independent experiments, mean ± S.D). f, Mass spectrum traces of 5′dA by ESI+. Reactions were conducted with 100 μM Rvip, 1mM SAM, 1mM deuCTP and/or 10 mM UDP-glucose. The mass spectrum of 5′dA produced during these reactions show only the presence of deuterium, which derives from deuCTP, even when UDP-glucose is present at 10 fold higher concentrations. An m/z of 252.1 represents the natural abundance peak of 5′dA, an m/z of 253.1 indicating the addition of one deuterium g, Mass spectrum trace showing −m/z of 5′-dA formed by combining 100 μM Rvip with 1mM deuCTP (dotted blue trace) or 1mM deuCTP with 1mM deoxyCTP (red trace). The y-axis of each spectrum was normalized to 100 % with arbitrary units (au) to allow direct comparison between each sample. The 5′-dA produced during this reaction has an m/z of 251.1, which is only consistent with Rvip abstracting a deuteron from deuCTP and not acting on the deoxyCTP (i.e., lack of m/z 250.1). h, Mass spectrum trace showing −m/z of 5′-dA or new product (i), formed by combining 100 μM Rvip with either 1mM CTP (dotted blue trace) or 1mM deuCTP (red trace). When Rvip was incubated with SAM and CTP deuterated at the 2′, 3′, 4′, 5′ and 5 positions (deuCTP), the negative ion m/z of 5′-dA increased from 250.1 to 251.1, consistent with the transfer of one deuterium from deuCTP to 5′-dA•. When ddhCTP from the reaction was analyzed by MS, the product exhibited a negative ion m/z of 468.1, indicating that the deuterium abstracted by 5′-dA during catalysis did not return to the product. The y-axis of each spectrum was normalized to 100 % with arbitrary units (au) to allow direct comparison between each sample. These results have been repeated at least twice.

Extended data 4. Viperin abstracts the 4′-H from CTP.

Using CTP with deuterium (2H denoted with red D) incorporated at either the a, 2′-2H, b, 3′-2H, c, 4′-2H or d, 5′-2H2 (left column), we were able to monitor the loss of deuterium from the resulting product (middle column) and gain of a deuterium in the resulting 5′dA (right column). The 5′dA −m/z increases by one only in reactions containing CTP with a 4′-2H (c, right column). Natural abundance peaks are denoted with dashed vertical lines. All experiments were repeated once.

Extended data 5. CMPK2 phosphorylates UDP or CDP and synthetic ddhC can be converted to ddhCTP by cellular machinery.

a, Formation of trinucleotide species (UTP, CTP or ddhCTP) from mono- and di-phosphate species (1mM UMP, UDP, CMP, CDP, or ddhCDP respectively) in the presence of either ATP or GTP as the phosphate donor by 5 μM Hs CMPK2. b, ddhCTP formation in HEK293T cells expressing either FLAG- Hs viperin (N- or C-terminal tags), FLAG- Hs viperin without N-terminal amphipathic region (delta 1-42), Hs CMPK2 only, FLAG-Hs viperin (N- or C-terminal tags), Hs CMPK2, FLAG- Hs viperin without N-terminal amphipathic region (delta 1-42) and Hs CMPK2, control plasmid, or cells only. Only in cases where the tag is on the N-terminus of the full length Hs viperin is produced ddhCTP at detectable levels. c, ddhCTP concentrations from HEK293T suspension cells that were incubated with synthetic ddh-cytidine (0, 1mM) for 24, 48 or 72 h (see Supplementary Information for details). d, ddhCTP concentrations from adherent Vero cells that were incubated with synthetic ddh-cytidine (0, 0.3, 1mM) for 24, 48 or 72 h (see Supplementary Information for details). nd = not detectable. All experiments were repeated once.

Extended Data 6. Cellular concentrations of nucleotides are not effected by viperin expression.

HEK293T cells expressing FLAG- Hs viperin (aqua), FLAG- Hs viperin and Hs CMPK2 (maroon), or cells only (dark blue). Samples were taken at 16 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h post infection. Extraction performed with acetonitrile/methanol/water (40:40:20 + 0.1M formic acid). Cellular concentrations were determined using 13C915N15-CTP, 13C1015N10-ATP, 13C10N5 –GTP and 13C915N2-UTP spiked into the extraction mixture at known concentrations and using equations 1 and 2 above. Analysis of nucleotides a, ATP, b, CTP, c, GTP, and d, UTP did not show statistically significant differences (ns) between FLAG- Hs viperin (aqua), FLAG- Hs viperin and Hs CMPK2 (maroon), or cells only (dark blue) for any time point. n = 3 biologically independent samples. Statistical significance was determined using a two-way ANOVA (Table S12, S13, S14 and S15). e, Ratio of cellular concentrations of ddhCTP to CTP from HEK293T cells expressing FLAG-Hs viperin (aqua) or FLAG- Hs viperin and Hs CMPK2 (maroon); samples were taken at 16 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h post transfection. The overall ratio of ddhCTP to CTP remains constant when only FLAG- Hs viperin is expressed, but the concentration of ddhCTP is boosted significantly relative to CTP when both FLAG- Hs viperin and Hs CMPK2 are co-expressed (plots are derived from c and Fig 3a data).

Extended data 7. Nucleotide concentrations are not effected during ddhCTP production.

a, ddhCTP, b, CTP, UTP and ATP in immortalized macrophage cells (RAW 264.7) grown in serum free media in the presence of increasing concentrations of murine IFN-alpha (10 ng/mL, 50 ng/mL and 250 ng/mL). n = 2 biologically independent samples.

Extended Data Figure 8.

ddhCTP is utilized as a substrate by DV and WNV RdRp and chain terminates RNA synthesis.

a, Schematic of primer extension assay for evaluating DV and WNV RdRp activity. b, DV RdRp-catalyzed nucleoside incorporation using CTP, 3′-dCTP or ddhCTP as nucleoside triphosphate substrates. Some full-length product was observed in the presence of ddhCTP (> 99 % pure), which is due to residual contaminating CTP that could not be removed). c, Reaction products resolved by denaturing PAGE containing 40% formamide showing the trace amount of CTP contaminate in the ddhCTP preparation. These experiments were repeated independently at least four times with similar results. d, Longer incubation times and more DV RdRp enzyme does not increase the yield of extended product. e, DV RdRp-catalyzed nucleoside incorporation with increasing concentrations of ddhCTP (0, 1, 10, 100, 200 and 750 μM) at varying concentrations of CTP. This experiment was repeated independently three times with similar results. f, Plot of the percentage inhibition as a function of ddhCTP concentration at varying concentrations of CTP. Data were fit to a dose response curve to obtain IC50 values of ddhCTP of 60 ± 10, 120 ± 20, 520 ± 90, 3900 ± 700 μM at 0.1, 1, 10 and 100 μM CTP, respectively. This experiment was repeated at least three times with similar results. The total sample size is 24. The error reported is the standard error from the fit of the data to a dose response curve. g, Plot of IC50 values as a function of CTP concentration. The data were fit to a line with a slope of 38 ± 1 and an intercept of 91 ±. 25. The error reported is the standard error from the fit of the data to a line. h, WNV RdRp-catalyzed nucleoside incorporation with increasing concentrations of ddhCTP (0, 1, 10, 100, 200 and 750 μM) at varying concentrations of CTP. This experiment was repeated at least three times with similar results. i, Plot of the percentage inhibition as a function of ddhCTP concentration at varying concentrations of CTP. Data were fit to a dose response curve to obtain IC50 values of ddhCTP of 20 ± 10, 70 ± 10, 300 ± 40, 2700 ± 300 μM at 0.1, 1, 10 and 100 μM CTP, respectively. The total sample size is 24. The error reported is the standard error from the fit of the data to a dose response curve. j, Plot of IC50 values as a function of CTP concentration. The data were fit to a line with a slope of 27 ± 1 and an intercept of 31 ± 8. Both of these results demonstrate that once ddhCMP is incorporated, it effectively terminates synthesis and that the small amount of extended product is from a trace amount of CTP contamination. The error reported is the standard error from the fit of the data to a line.

Extended Data Figure 9. HRV-C and PV RdRp are poorly inhibited by ddhCTP.

a, Schematic of primer extension assay for evaluating HRV-C RdRp activity. b, HRV-C RdRp-catalyzed nucleoside incorporation using CTP, 3′-dCTP or ddhCTP as nucleoside triphosphate substrates. These experiments were repeated independently at least four times with similar results. c, Increasing concentrations of ddhCTP does not efficiently inhibit HRV-C RdRp-catalyzed RNA synthesis. HRV-C RdRp-catalyzed nucleoside incorporation in the presence of increasing concentrations of either ddhCTP or 3′-dCTP. These experiments were repeated independently at least five times with similar results. d, Plot of the percentage inhibition as a function of either ddhCTP or 3′-dCTP concentration. Data were fit to a dose response curve to obtain IC50 values of 900 ± 300 μM for ddhCTP and 5 ± 1 μM for 3′-dCTP, respectively. The total sample size is 8. The error reported is the standard error from the fit of the data to a dose response curve. e–f, HRV-C (panel e) and PV (panel f) RdRp-catalyzed nucleoside incorporation with increasing concentrations of ddhCTP (0, 1, 10, 100 and 200 μM) at varying concentrations of CTP. Reactions were performed with the trinucleotide primer, 5′-pGGC, and 20-nt RNA template as described for DV and WNV RdRp in order to directly compare results with HRV-C and PV RdRp. At the highest concentration of ddhCTP, only ~2% inhibition was observed for HRV-C RdRp at 0.1 and 1 μM CTP. The IC50 values at 0.1 and 1 μM CTP are estimated to be ~10,000 and 20,000 μM ddhCTP, respectively. These values are 3-orders of magnitude higher than obtained for DV and WNV RdRp. Reactions in the presence of 3′-dCTP (200 μM) are shown as a control for inhibition. These experiments were repeated independently at least four times with similar results. g, Efficiency of incorporation and inhibition of viral RdRps. Footnotes: aCalculated for ddhCTP in direct competition with CTP (800 μM) using the linear equations obtained from the fit of data shown in panels g and j. For HRV-C, the IC50 value was estimated to be two orders magnitude greater than that calculated for DV and WNV RdRps as evidenced from the data shown in panels m, n and o. bCalculated for a ddhCTP concentration of 350 μM using the following equation: Probability = [ddhCTP]/([ddhCTP] + IC50). cCalculated using the following equation: full-length genome (%) = 100*(1− probability)^Cn; where, Cn is the number of cytidine residues in the viral genome with values of 2200, 2497,1565 and 1737, for DV, WNV, HRV-C and PV respectively.

Extended Data 10. ddhC reduces virus release of three different ZIKV isolates.

Vero cells were treated with increasing concentrations of ddhC (0, 0.1, and 1 mM) for 24 h and infected with one of three strains of ZIKV; African strain MR766 (Uganda 1947), PRVABC59 (Puerto Rico; 2015) and R103451 (Honduras; 2016, GenBank: KX262887). Viral titers at 24, 48 and 72 hpi were determined using plaque assay. a, b, and c, represent the effect of ddhC on three different ZIKV isolate; a, MR766 (Uganda 1947) b, PRVABC59 (Puerto Rico; 2015) c, and R103451 (Honduras; 2016). Analysis of ZIKV titers indicates that 1mM ddhC inhibits all three ZIKV isolates compared to 0 mM ddhC. However, reduction in virus titer is more prominent at 24 hpi and 48 hpi compared to 72 hpi when using an MOI of 1.0. The antiviral effect of ddhC is more prominent at an MOI of 0.1. (n = 3 biologically independent samples, mean ± S.D., two-way ANOVA and a Dunnett post-hoc analysis).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S.J. Booker for helpful discussions, L. Nordstroem (Chemical Synthesis & Biology Core Facility) for synthesis of ddhC, and R. Sharma and J. Perryman for assistance with construction of RdRp expression plasmids and purification of RdRp enzymes. This work was supported by NIH Grants R21-AI133329 (TLG and SCA), P01-GM118303-01 (JAG and SCA), U54-GM093342 (JAG and SCA), U54-GM094662 (SCA), R01-AI045818 (CEC), Pennsylvania State University Start-Up Funds (JJ), and the Price Family Foundation (SCA). We acknowledge the Albert Einstein Anaerobic Structural and Functional Genomics Resource (http://www.nysgxrc.org/psi3/anaerobic.html).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

A.S.G., T.L.G., J.J.A., C.E.C., and S.C.A. designed the research; A.S.G. and T.L.G. contributed equally; A.S.G. and T.L.G., prepared protein and performed experiments; J.J.A. performed polymerase biochemistry; J.J. performed ZIKV release assays; Q.D. prepared isotopologues; R.K.J. and K.C. performed statistical analysis; S.M.C. performed NMR measurements; S.J.G prepared HEK293T cells; N.G.D. prepared RAW264.7 cells; All authors analyzed data. T.L.G., J.D.L., A.R.B., C.E.C., and S.C.A. supervised research. A.S.G., T.L.G., J.J.A., C.E.C., and S.C.A. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

A.S.G., T.L.G., J.J.A., C.E.C., and S.C.A. are co-inventors on a U.S. provisional patent application (No. 62/548,425; filed by S.C.A) that incorporates discoveries described in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Molinari NAM, et al. The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the US: Measuring disease burden and costs. Vaccine. 2007;25:5086–5096. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang HB, et al. Viperin inhibits rabies virus replication via reduced cholesterol and sphingomyelin and is regulated upstream by TLR4. Scientific reports. 2016;6:30529. doi: 10.1038/srep30529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helbig KJ, Beard MR. The role of viperin in the innate antiviral response. Journal of molecular biology. 2014;426:1210–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seo JY, Yaneva R, Cresswell P. Viperin: A Multifunctional, Interferon-Inducible Protein that Regulates Virus Replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hover BM, Loksztejn A, Ribeiro AA, Yokoyama K. Identification of a cyclic nucleotide as a cryptic intermediate in molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2013;135:7019–7032. doi: 10.1021/ja401781t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenwick MK, Li Y, Cresswell P, Modis Y, Ealick SE. Structural studies of viperin, an antiviral radical SAM enzyme. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2017;114:6806–6811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705402114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennedy AD, et al. Complete nucleotide sequence analysis of plasmids in strains of Staphylococcus aureus clone USA300 reveals a high level of identity among isolates with closely related core genome sequences. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2010;48:4504–4511. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01050-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yokoyama K, Numakura M, Kudo F, Ohmori D, Eguchi T. Characterization and mechanistic study of a radical SAM dehydrogenase in the biosynthesis of butirosin. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15147–15155. doi: 10.1021/ja072481t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebrahimi KH, et al. The radical-SAM enzyme Viperin catalyzes reductive addition of a 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical to UDP-glucose in vitro. FEBS letters. 2017 doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee H. A Proposed Mechanism for the Radical SAM Enzyme Viperin. Bachelor of Science thesis, University of Illinois; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giese B, Beyrich-Graf X, Erdmann P, Petretta M, Schwitter U. The chemistry of single-stranded 4′-DNA radicals: influence of the radical precursor on anaerobic and aerobic strand cleavage. Chemistry & biology. 1995;2:367–375. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grove TL, et al. A substrate radical intermediate in catalysis by the antibiotic resistance protein Cfr. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:422–427. doi: 10.1038/NCHEMBIO.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kambara H, et al. Negative regulation of the interferon response by an interferon-induced long non-coding RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:10668–U10805. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu YJ, Johansson M, Karlsson A. Human UMP-CMP kinase 2, a novel nucleoside monophosphate kinase localized in mitochondria. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:1563–1571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teng TS, et al. Viperin restricts chikungunya virus replication and pathology. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4447–4460. doi: 10.1172/Jci63120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang B, et al. Viperin is induced following toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) ligation and has a virus-responsive function in human trophoblast cells. Placenta. 2015;36:667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang HB, et al. Viperin inhibits rabies virus replication via reduced cholesterol and sphingomyelin and is regulated upstream by TLR4. Sci Rep-Uk. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/Srep30529. Artn 30529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang D, et al. Identification of five interferon-induced cellular proteins that inhibit west nile virus and dengue virus infections. J Virol. 2010;84:8332–8341. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02199-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Slyke GA, et al. Sequence-Specific Fidelity Alterations Associated with West Nile Virus Attenuation in Mosquitoes. PLoS pathogens. 2015;11:e1005009. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panayiotou C, et al. Viperin restricts Zika virus and tick-borne encephalitis virus replication by targeting NS3 for proteasomal degradation. J Virol. 2018 doi: 10.1128/JVI.02054-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szretter KJ, et al. The Interferon-Inducible Gene viperin Restricts West Nile Virus Pathogenesis. Journal of virology. 2011;85:11557–11566. doi: 10.1128/Jvi.05519-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang SS, et al. Viperin inhibits hepatitis C virus replication by interfering with binding of NS5A to host protein hVAP-33. J Gen Virol. 2012;93:83–92. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.033860-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dick GW, Kitchen SF, Haddow AJ. Zika virus. I. Isolations and serological specificity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1952;46:509–520. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(52)90042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lanciotti RS, Lambert AJ, Holodniy M, Saavedra S, del Signor LC. Phylogeny of Zika Virus in Western Hemisphere, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:933–935. doi: 10.3201/eid2205.160065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Proud D, et al. Gene expression profiles during in vivo human rhinovirus infection: insights into the host response. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2008;178:962–968. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-670OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seo JY, Cresswell P. Viperin regulates cellular lipid metabolism during human cytomegalovirus infection. PLoS pathogens. 2013;9:e1003497. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.