Abstract

Orofacial pain includes neuronal pathways that project from the trigeminal nucleus to and through the thalamus. What role the ventroposterior thalamic complex (VP) has on orofacial pain transmission is not understood. To begin to address this question an inhibitory G protein (Gi) designer receptor exclusively activated by a designer drug (DREADD) was transfected in cells of the VP using adeno-associated virus isotype 8. Virus infected cells were identified by a fluorescent tag and immunostaining. Cells were silenced after injecting the designer drug clozapine-n-oxide, which binds the designer receptor activating Gi. Facial rubbing and local field potentials (LFP) in the VP were then recorded in awake, free moving Sprague Dawley rats after formalin injection of the masseter muscle to induce nociception. Formalin injection significantly increased LFP and the nociceptive behavioral response. Activation of DREADD Gi with clozapine-n-oxide significantly reduced LFP in the VP and reduced the orofacial nociceptive response. Because DREADD silencing can result from Gi-coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium channels (GIRK), the GIRK channel blocker tertiapin-Q was injected. Injection of GIRK blocker resulted in an increase in the nociceptive response and increased LFP activity. Immunostaining of the VP for glutamate vesicular transporter (VGLUT2) and gamma-aminobutyric acid vesicular transporter (VGAT) indicated a majority of the virally transfected cells were excitatory (VGLUT2 positive) and a minority were inhibitory (VGAT positive). We conclude first, that inhibition of the excitatory neurons within the VP reduced electrical activity and the orofacial nociceptive response and that the effect on excitatory neurons overwhelmed any change resulting from inhibitor neurons. Second, inhibition of LFP and nociception was due, in part, to GIRK activation.

Keywords: pain, ventral posterior medial thalamus, GABA, glutamate, neurons, orofacial

Introduction

There is a need to determine the underlying neuronal circuitry of temporomandibular and orofacial pain (Conti et al., 2012; Giannakopoulos et al., 2010; Israel and Davila, 2014). One central pain pathway involves the ventroposterior thalamic complex (VP) which includes the ventral posterior medial (VPM) and ventral posterior lateral thalamic nuclei (VPL). The VP is innervated by orofacial pain neurons projecting from the trigeminal nucleus (Guy et al., 2005; Kobayashi, 1995; Mantle-St John and Tracey, 1987; Patrick and Robinson, 1987; Phelan and Falls, 1991; Steindler, 1977; Steindler, 1985; Voisin et al., 2002; Waite, 2004; Watson and Switzer, 1978). Information, including nociceptive signals, relayed from the face and head are processed in the thalamus (Matthews et al., 1987; Sessle, 1999). Moreover, the thalamus has been shown to have decreased volume in patients with trigeminal neuropathy (Gustin et al., 2011). The VPM has been shown to process tooth pain leading to the phenomena of central sensitization (Park et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2006). This VP region processes somatosensory information from the head and facial muscles and is therefore an ideal place to investigate orofacial pain transmission and modulation. One of the key features of the thalamus is its interconnectedness with the cerebral cortex (Yen and Lu, 2013). After synapsing in the thalamic neurons, third order neurons then project to areas such as the somatosensory cortex and cingulate cortex resulting in the sensory and affective perception of pain (Falls et al., 1985; Huerta et al., 1983).

Activation of transmembrane G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) can have various functions central to the regulation of cellular function including hormones, neurotransmitters, and many large and small molecules involved in nociception, vision, olfaction, and taste (Deupi and Kobilka, 2007; Gainetdinov et al., 2004; Katritch et al., 2013; Noseda et al., 2014; Pitcher et al., 1998; Strader et al., 1994). G proteins are involved in the modulation of pain, and notably these receptors can modulate pain responses through opioid signaling within the thalamus (Hoot et al., 2011; Ko et al., 2003). For example, Hoot et al. determined that modulation of G protein signaling within the thalamus can result in desensitization of opioid signaling (Hoot et al., 2011). In addition to opioid signaling, the cannabinoid receptors signal through G-proteins and modulation of these receptors in the thalamus can alter the pain response (Martin et al., 1996).

Neurotransmitter binding to GPCRs signal G protein activation of G protein induced inward-rectifying potassium channels (GIRK) channels (Pfaffinger et al., 1985). GIRK channels likely have a role in pain as mutations resulting in loss of K+ selectivity prevent opioid attenuation of pain (Ikeda et al., 2000; Slesinger et al., 1996). In GIRK 2 mutant mice a higher dose of opioids were needed to obtain a similar level of analgesia (Mitrovic et al., 2003) suggesting a role in opioid pain attenuation. Moreover, GIRK 1 mutant mice show a reduced response to multiple opioid agonists and tertiapin, as used in these studies, will reduce the effectiveness of mu opioid agonists (Marker et al., 2005) indicating a role of GIRK channels in pain transmission.

A technique to influence GPCR signaling is through the use of designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADD). DREADDs are a modified acetylcholine GPCR that are engineered to be selectively bound and activated by the inert chemical clozapine-n-oxide (CNO) instead of acetylcholine. The addition of CNO activates Gi, Gs or Gq causing inhibition or activation of neuronal activity. DREADD constructs have been proven to function in hippocampal neurons through activation of Gi to induce neuronal silencing (Armbruster et al., 2007). The DREADD constructs were transduced through the use of adeno-associated virus (AAV).

Immunostaining of the VP for glutamate vesicular transporter (VGLUT2) and gamma-aminobutyric acid vesicular transporter (VGAT) was completed to identify the cell type transfected with the DREADD construct. VGLUT2 is a glutamate transporter within excitatory glutamatergic cells and glutamate is a key signaling molecule in the thalamic region, relaying pain from periphery (Acher and Goudet, 2015; Bhave et al., 2001; Osikowicz et al., 2013). VGAT is a GABA transporter within inhibitory GABAergic cells. Our lab has evidence that GABAergic cells in the reticular thalamic region play a role in modulating orofacial pain (Kramer et al., 2017).

The role of thalamic signaling in modulating orofacial pain is currently unknown and our goal was to test whether inhibition of thalamic neurons, through the use of DREADDS, could attenuate nociceptive signaling in the VP. Given the demonstration of DREADDs in the hippocampus, we expected the construct should also facilitate neuronal silencing in the VP, as demonstrated by a reduction in local field potentials (LFP) in the awake, free moving rat. Given that the majority of neurons in the rat VP are excitatory glutamatergic (GLUT) neurons (Lein et al., 2007), we expect that this reduction of neuronal activity would attenuate the masseteric nociceptive response or responses due to pain induced in the masseter muscle. Acetylcholine receptor subtype hM4D activates Gi, silencing neuronal activity by either causing hyperpolarization and activation of GIRK (Armbruster et al., 2007) or by the presynaptic inhibition of GLUT release (Scanziani et al., 1997). We tested one of these pathways by adding GIRK blocker, tertiapin-Q. Our hypothesis was that the addition of the blocker would modulate activity of the DREADD construct and reverse the behavioral response and restore LFP.

Experimental Procedures

Animal Husbandry

The Texas A&M University College of Dentistry Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the experimental protocol. Procedures were conducted in compliance with all guidelines established in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Animal Welfare Act and IASP Guidelines for the Use of Animals in Research. Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (300-350 grams) from Envigo, Houston, TX were kept on a 14:10 light/dark cycle with lights on at 07:00 hours. The rats were given food and water ad libitum. Fourty-two rats were used in total to complete the experiments reported in this manuscript. After a 4 day acclimation period surgeries were performed.

Surgery

Rats were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane in an air flow of 2 liter per minute. Using sterile technique a Hamilton infusion needle (Neuros #7002) was stereotaxically inserted into the VP (3.6 mm posterior of Bregma, 2.8 mm from midline at a depth of 6.0 mm from the top of the skull). A Stoelting stereotaxic syringe pump system was used to infuse 0.250 μl of 2-8 ×1012 pfu/ml adeno-associated virus isotype 8 (AAV8) or no virus (350 nM NaCl, 5% D-Sorbitol in PBS) at a rate of 20 nanoliters per minute. After infusion the needle was left in place for 5 minutes and then removed. In a pilot experiment infusing India ink into the VP we observed a spread of about 1 mm from the injection site (Supplemental Figure 1). AAV8 contained a neuronal silencing construct Syn-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry (Gene Therapy Center Vector Core, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) which expressed an engineered acetylcholine Gi-protein coupled receptor that inhibits neuronal burst firing when bound by CNO. To affect change in neuronal activity, the modified acetylcholine Gi protein-coupled receptor was driven by the neuronal synapsin-1 promoter (Syn). Instead of binding to its native ligand acetylcholine, the receptor binds to CNO to induce activation of Gi. After virus infusion the Hamilton needle was removed and a permanent 22 gauge cannula/electrode (C313G-MS302-2-SPC, Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) or cannula C313G was inserted into the same stereotaxic coordinates. The recording and infusion electrode were held in place with four screws and dental cement. These injections and cannulas were placed bilaterally. After surgery the animals were given a 5 mg/kg dose of nalbuphine I.M. (Hospira, Lake Forest, IL) and housed with a soft diet until recovery. Three weeks following AAV8 infusion further testing was performed. This time period allowed for expression of the DREADD construct (Alexander et al., 2009).

Recording electrical activity

LFPs were recorded using a customized wireless recording module (Zuo et al., 2012) attached to the recording electrode which was implanted directly into the VP. LFP is the summation of extracellular currents recorded at subthreshold levels and offers a uniquely integrated view of the activity in a specific brain area (Mazzoni et al., 2008). LFP was recorded using a low pass filter of 100Hz. Standard techniques of applying a fast Fournier transform (FFT) were used (Masimore et al., 2004).

After a 30 minute acclimation to the text chamber rats were briefly (< 3 min) anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and fitted with a backpack containing the LFP customized wireless recording module (Zuo et al., 2012). The module was then connected to the recording electrode. After waking from anesthesia a 10 minute “Baseline” LFP was recorded. The “Preformalin” stage included recording for 30 minutes after intraperitoneally injecting a 0.5 ml volume of either 1 mg/kg dose of CNO in 0.9% saline or vehicle “no CNO” (0.9% saline) (Armbruster et al., 2007).

In the groups below LFP was recorded another 10 minutes (after the “Preformalin” stage) following a bilateral thalamic infusion of 0.5 μl of 100 nM or 500 nM (Kanjhan et al., 2005; Kanjhan and Bellingham, 2011) GIRK1/4 blocker tertiapin-Q (Tocris, Minneapolis, MN) or 0.5 μl of 0.9% saline (no GIRK blocker): Group 1, virus/no CNO/no GIRK blocker, n=12; Group 2, virus/no CNO/500 nM GIRK blocker, n=6; Group 3, virus/CNO/no GIRK blocker, n=6; Group 4, no virus/CNO/no GIRK blocker, n=6; Group 5, virus/CNO/100 nM GIRK blocker; Group 6, virus/CNO/500 nM GIRK blocker, n=6. The solution was infused over 5 minutes using the cannula while the rats were freely moving.

Next the rats were briefly anesthetized (less than 45 seconds) with 2% isoflurane and a 50 μl solution of 3% formalin was injected unilaterally into the rat masseter muscle on a randomly chosen side. Behavior and LFP were recorded for 45 minutes. The LFP measurement included: Phase 1, 0-9 minutes post-formalin injection; Interphase, 9-21 minutes post-formalin injection; and Phase 2, 21-45 minutes post-formalin injection.

Signals from the electrode were amplified and changed from volts to digital form by an Analog-to-Digital Converter (C8051F920, Silicon Laboratories, Austin, Texas) within the recording microcontroller module. Signals were transmitted by a receiver on a USB dongle to a laptop using customized software. The signals were saved as data in a text file and imported as a raw waveform at a sampling rate of 4096 Hz (CED Spike2 V7 software, Cambridge, UK).

The power at frequencies from 1 to 100 Hz was included in the analysis, except the power of frequencies at 50, 51, 52, 53 Hz caused by the 50 Hz ambient noise. The results from power spectrum analysis were presented in 3 min segments and were further categorized into the Delta (<4 Hz), Theta (4-8 Hz), Alpha (8-13 Hz), Beta (13-30 Hz) and Gamma (30-100 Hz) frequency bands.

Nociceptive Behaviors

Simultaneous to the recordings, signs of formalin induced orofacial nociception were measured in the same cohort of awake freely moving rats by counting hind and forepaw rubbing events of the injection area or head shaking (one shake measured as one second) (Clavelou et al., 1989). To perform these measurements the rats were placed in a 30 cm × 30 cm × 30 cm clear acrylic box (i.e., test chamber) 30 minutes before testing. Testing was completed during the light phase between 10:00 am and 3:00 pm. Lights were on at 7:00 am and off at 9:00 pm. Testing for “Baseline” was completed for 3 minutes before the “Preformalin” stage. The values are how many seconds the nociceptive response was expressed within 3 minutes bins.

Immuno-fluorescent Staining

After LFP and behavioral measurements the rats were deeply anesthetized with 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine and then perfused with 9% sucrose followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. The brain was extracted using a rongeur and stored in 25% sucrose at 4°C. Fixed whole brains stored in 25% sucrose were later frozen, cryo-sectioned and the 20 μm sections placed on Histobond slides (VWR international, Radnor, PA). The tissue was then blocked with a PBS solution containing 5% normal goat serum and 0.3% Triton-X 100 for 2 hours at room temperature. Following three rinses in PBS with 0.3% Triton-X 100 the slides were incubated in a primary antibody solution overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies consisted of the mouse monoclonal NeuN antibody at a 1:250 dilution (Millipore, Billerica, MA), a 1:300 dilution of the mouse monoclonal VGLUT2 antibody (ab79157, abcam, Cambridge, MA) or a 1:300 dilution of the rabbit polyclonal VGAT antibody (AB5062P, Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Primary antibodies were diluted with PBS, 5% BSA and 0.3% Triton X-100. After incubation in primary antibody the slides were rinsed three times in PBS and Triton-X 100 for a total of 60 min and placed for 2 hours in a 1:500 dilution of secondary antibody in PBS and 0.3% Triton X-100. Secondary antibodies were either goat anti-mouse Alexa 488 conjugate or goat anti-rabbit Alexa 488 conjugate (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After rinsing the slides three times in PBS for a total of 30 min, the slides were then mounted with Fluoromount-G mounting medium containing Hoechst 33342 stain (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). The fluorescent signal was imaged using a Nikon fluorescent microscope and NIS-Elements imaging software and a Photometrics CoolSnap K4 CCD camera (Roper Scientific, Inc., Duluth, GA).

Cell counting

Cell counts for NeuN, VGLUT2 and VGAT staining was completed by an observer blinded to the treatment group. Representative counts were obtained on a 20 micrometer section at the site of injection, where the needle path could be observed. No lesion was observed in the thalamus resulting from the injection. There were typically three sections per animal on which we could observe the needle path, one slide was used for NeuN staining, the other for VGLUT2 staining and the third for VGAT staining. Each counted field was a circle 0.35 mm in diameter or having an area of 0.1 mm2. Counts were completed in the three regions containing virus infected cells; VPM/VPL, reticular thalamus (Rt), and zona incerta (ZI). Cell counts were completed on six rats per treatment group. On each slide three randomly chosen fields adjacent to the injection site were chosen for the counting in each region. Counts were completed in tissue without any observable histological damage from the cannula or injection. Based on mCherry expression the virally transduced genes were expressed between 0.5 and 1 mm from the injection tip, consistent with a pilot experiment showing the spread of India ink (Supplemental Figure 1). Note: the same volume of virus and India ink were infused.

Statistics

Changes in nociceptive behavior and LFP power data were analyzed using a non-parametric Mann-Whitney (Figure 1A and Figure 2) or Kruskal-Wallis (Figure 1B) test due to assumption violations required for ANOVA. Further testing of the main effect in Figure 1B was completed using Dunns post-hoc test. Cell count data was analyzed using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis (Prism, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). The independent variables were treatment (CNO, no CNO) and region (VPM/VPL, Rt, ZI) and the dependent variable was cell number. Significance was indicated when p<0.05.

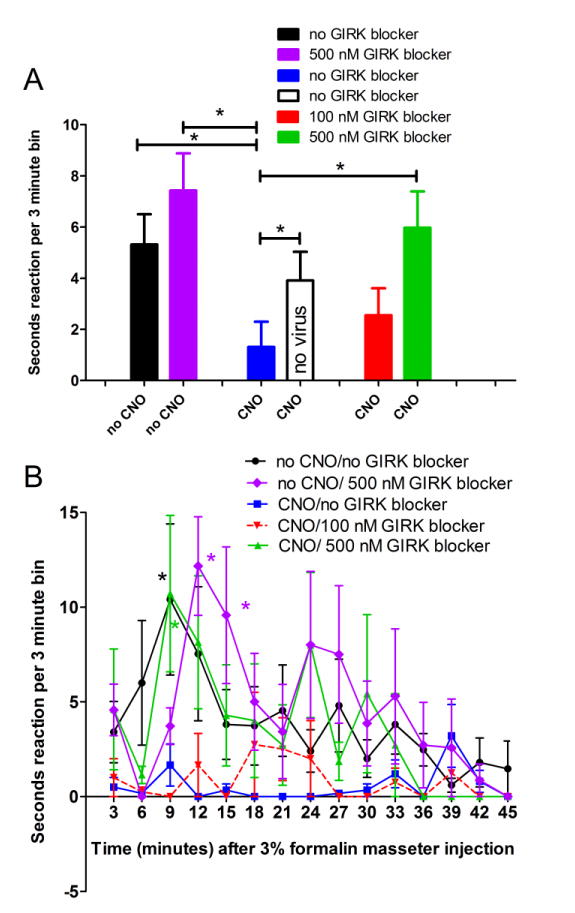

Figure 1.

The nociceptive response resulting from injecting formalin into the masseter was attenuated by activating Gi within the thalamus; this attenuation was not observed after blocking GIRK activity. Rats were infused with 0.250 μl of 2-8 ×1012 pfu/ml AAV8 or no virus (350 nM NaCl, 5% D-Sorbitol in PBS) and a cannula/electrode was placed in the VP region after injection. In panel A the nociceptive response was measured 9-21 minutes (Interphase) after formalin injection. In panel A all animals received virus or no virus and were then treated with CNO or no CNO (0.9% saline) and then GIRK blocker tertiapin-Q or no GIRK blocker (0.9% saline). At least three weeks following AAV8 injection and immediately after injecting the masseter with 50 μl of 3% formalin facial rubbing was measured in seconds or head shaking was counted (one shake measured as one second). Rubbing and shaking within a 3 minute periods (bins) was reported. In panel B the response for all the virus infected groups are shown over time. An asterisk indicates a significant difference of p<0.05. There were 6 animals per group with exception of the no CNO/no GIRK group in which there were 12 animals.

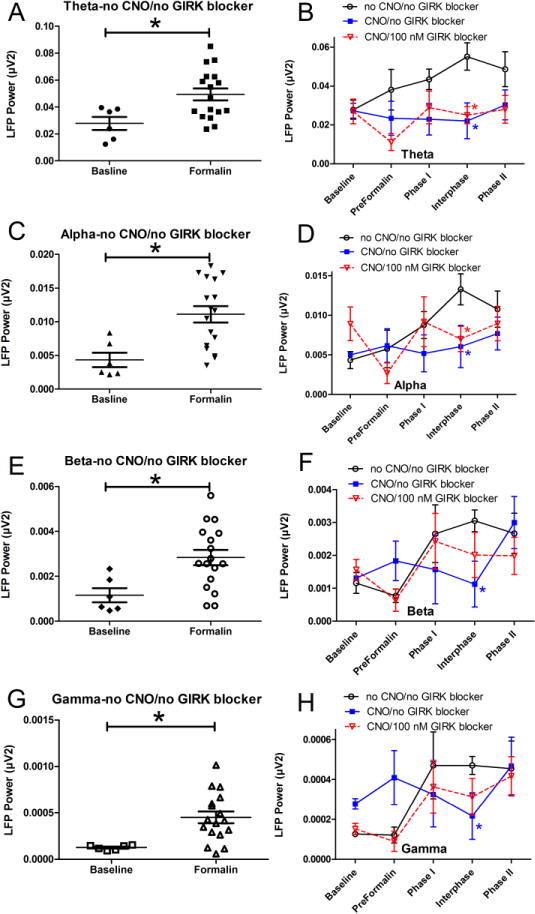

Figure 2.

Electrical activity in the VP increased after injecting formalin into the masseter and this response was attenuated by activating Gi within the thalamus; this attenuation was not observed after blocking GIRK activity. In panels A, C, E and G each symbol represents the average electrical response (LFP power) for each animal throughout the post-formalin period at four different frequency ranges; Theta (panel A), Alpha (panel C), Beta (panel E) and Gamma (panel G) wavelengths. An asterisk indicates a significant difference of p<0.05 between the baseline measurement and the averaged post-formalin measurements. In panels B, D, F and H recording after formalin injection was divided into Phase 1 (0-9min), Interphase (9-21 min), and Phase 2 (21-45 min). Baseline and Preformalin measurements were recorded before injecting formalin. In panels B, D, F and H an asterisk indicates a significant difference versus the no CNO/no GIRK blocker group for each frequency. There were 6 animals per group with exception of the no CNO/no GIRK group in which there were 12 animals. See legend to Figure 1 for drug treatment groups.

Results

When comparing the nociceptive response before injecting formalin (baseline) to 9-21 minutes after injecting formalin (interphase) there was a significant increase for all groups (p<0.05) with exception of the CNO/no GIRK blocker group. To address whether CNO alone would reduce the formalin induced nociceptive response, rats that did not have DREADDs (no virus) were given CNO (Fig. 1A). The results show CNO did not significantly decrease the formalin-induced nociceptive when no virus was present (compare the solid black bar to the open black bar, Fig. 1A). After administration of the GIRK 1/GIRK 4 blocker (tertiapin-Q) the CNO treated rats had a significant nociceptive response when comparing baseline to interphase (p<0.05). Treatment with a 500 nM dose of this GIRK blocker significantly increased the nociceptive response of the CNO treated animals (compare CNO/500 nM GIRK blocker group to the CNO/no GIRK blocker group, Fig. 1A). Note that GIRK alone does not significantly alter the nociceptive response during interphase, compare the no CNO/no GIRK blocker group (solid black bar) to the no CNO/500 nM GIRK blocker group (purple bar) (Fig. 1A).

Looking at the formalin-induced response over time there was a significant main effect (p<0.05) in the group without CNO and without tertiapin-Q (black line, Fig. 1B). Post-hoc testing demonstrated a significant response during interphase when comparing the no CNO/no GIRK blocker group (black line) to the CNO/no GIRK blocker group (blue line) or the CNO/100 nM GIRK blocker group (red line) (Fig. 1B). Post-hoc testing also indicated a significant response between the CNO/500 nM GIRK blocker group (green line) and the CNO/no GIRK blocker group (blue line) or the CNO/100 nM GIRK blocker group (red line) (Fig. 1B). At 12 and 15 minutes there was a significant difference between the no CNO/500 nM GIRK blocker group (purple line) and the CNO/no GIRK blocker group (blue line) or the CNO/100 nM GIRK blocker group (red line) (Fig. 1B).

Formalin significantly increased LFP activity in the theta, alpha, beta and gamma wavelengths (Fig. 2A, C, E, G). CNO decreased this response during the interphase period, compare the no CNO/no GIRK blocker group to the CNO/no GIRK blocker group (Fig. 2B, D, F and H). There was a significant change in the LFP response at the theta and alpha frequencies after administration of 100 nM GIRK 1/GIRK 4 blocker tertiapin-Q, compare the no CNO/no GIRK blocker group to the CNO/100 nM GIRK blocker group (Fig. 2B and D). At the beta and gamma frequencies this effect was not significant, compare no CNO/no GIRK blocker group to the CNO/100 nM GIRK blocker group (Fig. 2F and H). CNO alone did not significantly affect LFP in rats that did not receive virus (Supplemental Figure 2). Representative traces of the electrical response are shown in Supplemental Figure 3.

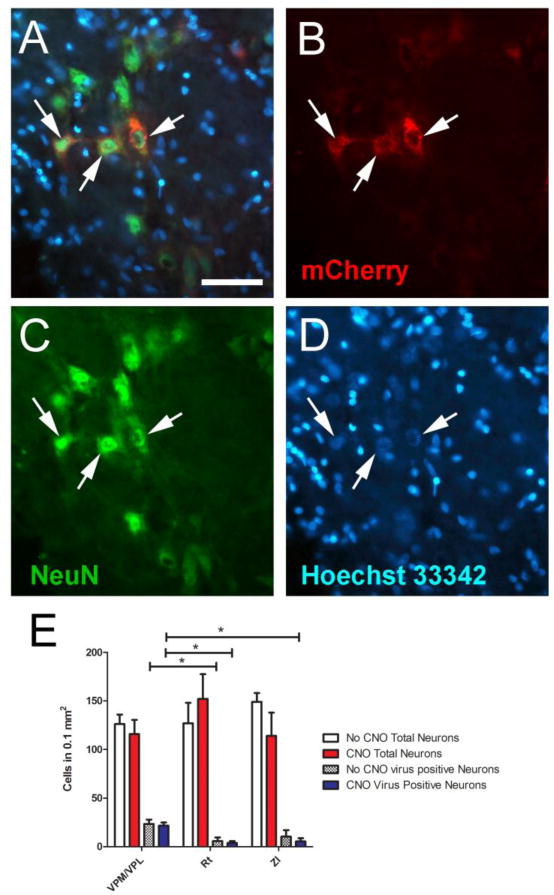

CNO treatment had a significant effect on the electrical response in the virally infected rats and to determine a potential mechanism that would alter the electrical response immunofluorescent staining for VGLUT2 and VGAT was completed. Staining within the thalamic region of virally infected rats treated with and without CNO indicated that a majority of the virus infected cells were neurons (Fig. 3A-D). Cell counts verified this result by demonstrating that 97% of the virus infected cells co-localized with the neuronal NeuN marker. Sixty-four percent of the virus infected cells were located in the VPM/VPL region, 14 percent in the Rt and 22 percent in the ZI (Fig. 3E). Thus, while the total number of neurons (NeuN positive cells) per unit area was not significantly different between the VPM/VPL, Rt or ZI, the number of virally infected neurons was significantly greater in the VPM/VPL versus the Rt and ZI (Fig. 3E). There was no significant effect of CNO treatment on the cell counts.

Figure 3.

Representative images were taken from the VP region of a rat that received CNO (panels A-D). Arrows point to NeuN positive cells (panel C, green) infected with the AAV8 virus (panel B, red); double labeled cells are shown in panel A, arrows. The slides were counter stained with the nuclear Hoechst 33342 stain (blue, panel D). Bar equals 50 micrometers. E) Cell counts were completed for each animal in fields adjacent to the injection site in each of three regions; ventral posterior medial (VPM)/ventral posterior lateral thalamic nuclei (VPL), reticular thalamic nucleus (Rt), and the zona incerta (ZI). Neurons were counted as the NeuN positive cell population. The values are the mean and SEM for 6 animals per each treatment group. Asterisk indicates a significant difference, p<0.05.

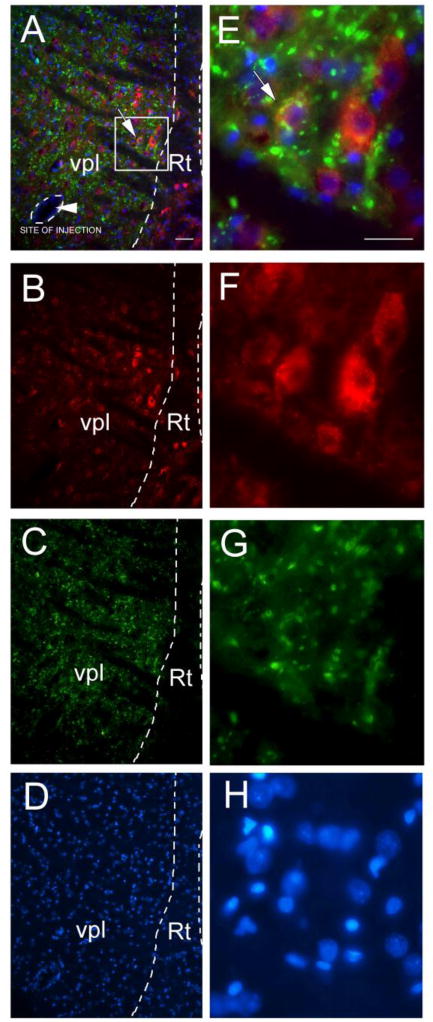

Combining CNO and no CNO treatment groups, 96% of the cells within the VPM/VPL co-localized with the excitatory neuronal marker VGLUT2 (n=12) and less than 3% of the neurons in the Rt and ZI co-expressed VGLUT2 (Fig. 4). Seventy-three percent of the virus infected cells in the Rt express VGAT (Fig 5) and few virus infected cells co-localized with VGAT in the ZI.

Figure 4.

Virally infected cells (mCherry, red) co-localize with the glutamatergic neuronal marker VGLUT2 (green), panels A and E. Figure 4 shows representative images for a rat injected with AAV8 construct hSyn-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry that did not receive CNO or tertiapin-Q. AAV8 infected cells expressed mCherry (red, panels B and F) and the tissue was immune-stained for VGLUT2 (green, panels C and G). The slides were counter stained with the nuclear Hoechst 33342 stain (blue, panels D and H). Low magnification images show the ventral posterolateral nucleus of the thalamus (VPL) and the reticular thalamic nucleus (Rt) (panels A-D). Boxed region in panel A is enlarged in panels E-H. In panel A arrowhead points to site of AAV8 injection, outlined with dotted line. Arrow points to AAV8 infected cell (red) co-localized with VGLUT2 (green). Bar= 50 μm.

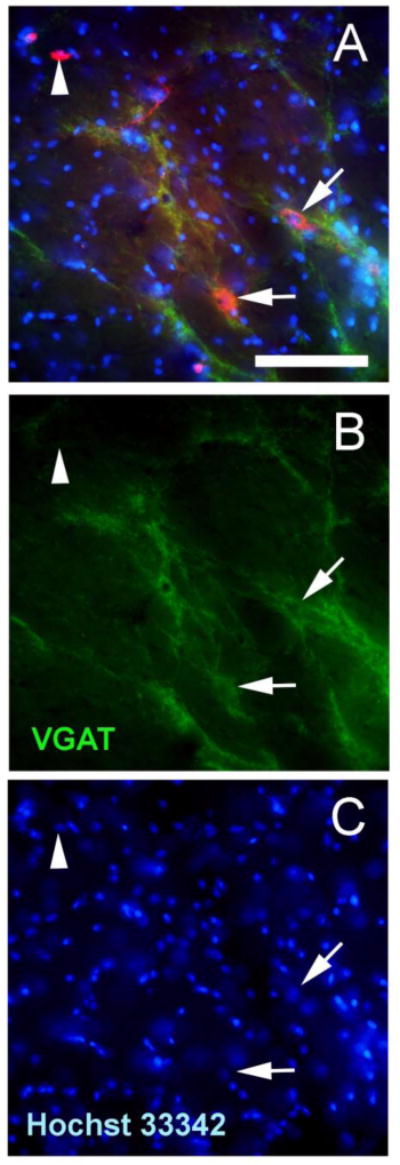

Figure 5.

Representative image taken from the reticular thalamic region of a rat that received CNO (panels A-C). In panel A, arrows point to cells infected with the AAV8 virus (red) that co-localized with VGAT (green). Arrowhead points to a cell infected with the AAV8 virus that does not contain VGAT. Panel B shows VGAT staining and panel C shows the Hoechst 3342 staining. Bar equals 50 μm.

Discussion

Injecting formalin into the masseter muscle of Sprague-Dawley rats significantly increased the orofacial nociceptive response and increased LFP activity in the thalamus. Activation of Gi in the VP through the administration of CNO attenuated the nociceptive response and reduced LFP in the thalamic region. Approximately two-thirds of the virus infected cells co-localized with the glutamatergic marker VGLUT2 and most of the remaining cells were associated with the GABA marker VGAT. From these results we conclude that Gi inhibits a glutamatergic neuronal population in the VP suppressing the orofacial nociceptive response and reducing LFP during interphase or when a significant behavioral response was measured. Previously, mice injected with formalin had decreased burst firing of typical neurons after paw injection, this firing quickly returned to baseline and then became potentiated (Huh and Cho, 2016). In contrast, burst firing of atypical neurons remained at baseline until the end of the formalin response and then increased significantly above baseline suggesting different neuronal subtypes contribute differently to the formalin response. If Gi signaling inhibited a neuronal subset within the thalamus (important to interphase) DREADD’s effects would be restricted to interphase, as observed in this study. It is unclear how this subset would be targeted by AAV, the different neuronal subtypes within the thalamus are not well characterized and may have been localized to the injection site.

Gi facilitates neuronal silencing through GIRK activation, calcium influx and kinase activation (Alexander et al., 2009; Armbruster et al., 2007). A question in this study was; do GIRK channels modulate thalamic activity and pain behavior when the Gi protein becomes activated? GIRK 1/2 are involved in nociceptive processing and are expressed in the trigeminal ganglion (Chung et al., 2014) and thalamus (Saenz del Burgo et al., 2008). However, GIRK 1 is not expressed at postsynaptic sites throughout the central nervous system in postnatally (Fernandez-Alacid et al., 2011) and cannot form channels alone but must combine with GIRK2-4 (Dhar and Plummer, 2006; Luscher and Slesinger, 2010). GIRK2 channels are found in most brain regions, including the thalamus, and in dendritic spines, shafts and presynaptic axon terminals (Filipek et al., 2003). Tertiapin-Q, derived from honey bee toxin, acts as a high affinity GIRK1/4 blocker. If Gi reduced the nociceptive response and the LFP through a GIRK1/4 dependent mechanism we would have expected that injection of tertiapin-Q would reverse the response (Jin et al., 1999; Kanjhan et al., 2005). At a concentration of 100 nM GIRK blocker tertiapin-Q partially reversed the effect of CNO on the nociceptive behavioral response and reversed CNO’s effect on thalamic LFP activity at the beta and gamma frequencies. Behaviorally, blockade of CNO was greater with 500 nM of tertiain-Q thus, it would be likely that CNO’s effect on LFP activity would be significantly affected by this higher dose. These results are consistent with the idea that the orofacial nociceptive response was attenuated by a Gi dependent pathway that involves GIRK 1 and/or GIRK 4 signaling.

Another point for further investigation is to determine if any modulators of GIRK channels such as tyrosine kinase (TK), calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 2 (CAMK2), protein kinase A (PKA), protein kinase C (PKC), or protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) are activated upon CNO treatment (Luscher and Slesinger, 2010). PLC and PKA could both be inhibited by CNO's activation of Gi. However, since they may be soluble, they may still be able to affect an increase in LFP when the GIRK channel is blocked by tertiapin-Q (Sadja et al., 2003). Activation of Gi also inhibits cAMP, and activation of Gi causes release of calcium (Rogan and Roth). Although ionic flow such as IPSP and EPSP may dominate LFP activity (Buzsaki, 2004), any transmembrane current will also contribute to the LFP. This can include activity from dendrites, soma, axons, and glial cells (Buzsaki et al., 2012; Einevoll et al., 2013). Future studies will focus on the effect thalamic GIRK pathways would have on the nociceptive response by systematically eliminating the effects of ulterior pathways through the administration of blocker cocktails.

LFP offers information about the neuronal activity of larger networks in specific brain areas and can offer us a picture of how all the cellular activity works together to process important sensory and motor functions. LFP records the summation of electrical currents in active cellular processes (Zheng et al., 2012), primarily contributed through the EPSPs and IPSPs (Buzsaki et al., 2012) but also contributed by low frequency activity such as non-synaptic calcium spikes, glial cell fluctuations and other subthreshold membrane oscillations, somatodendritic after-potentials, and GABAA receptor inhibitory input (Berens et al., 2008). The use of awake and behaving animals for LFP recording is important in capturing neuronal activity changes accurately. Studies have found that anesthesia can alter the power at multiple frequency levels in the visual system and olfactory system, so a more accurate recording of neuronal activity can be seen in awake animals (Sellers et al., 2015).

These studies are the first to demonstrate an increase in the theta, alpha, beta and gamma wavelengths within the thalamus of a awake rat after formalin injection. Thalamic LFP amplitudes have been shown to correlate to the intensity of pain perception at very low frequencies (Nandi et al., 2003) and pain relief was associated with the theta, alpha, and beta frequencies in humans (Huang et al., 2016). Inflammatory and visceral pain has been associated with changes in the low frequency LFPs, consistent with our observation that there were changes in the theta wavelength after formalin injection (Harris-Bozer and Peng, 2016; Wang et al., 2015a). An increase in gamma frequency oscillation has been measured in the somatosensory cortex of humans during an induced pain condition (Gross et al., 2007; Lau et al., 2012). Understanding of the changes in particular frequencies could give clues to the mechanism or provide a diagnostic tool for a particular type of pain disorder.

Staining indicated that the virus localized primarily to neurons in the VPM/VPL region. A majority of these virus infected neurons co-localized with VGLUT2 suggesting virus primarily infected and attenuated glutamatergic excitatory neurons upon activation with CNO. Glutamate is a key signaling molecule in the thalamic region relaying pain from peripheral tissues (Acher and Goudet, 2015; Bhave et al., 2001; Osikowicz et al., 2013). Glutamate receptor gene expression is high in areas in which VP neurons terminate (Huntley et al., 1994). Interestingly, increased levels of thalamic glutamate are seen in varying acute and chronic pain conditions in both rodents and humans (Ghanbari et al., 2014; Likavcanova et al., 2008; Salt and Binns, 2000; Salt et al., 2014; Silva et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2015b; Zunhammer et al., 2016). Moreover, analgesic effects are related to lower levels of glutamate (Abarca et al., 2000; Naderi et al., 2014). And increased levels of glutamate in the thalamus are associated with various pain conditions (Ghanbari et al., 2014; Likavcanova et al., 2008; Salt and Binns, 2000; Salt et al., 2014; Silva et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2015b; Zunhammer et al., 2016) consistent with our results showing that inhibition of glutamatergic neurons in the thalamus attenuated the pain response. Although, neurons within the trigeminal nucleus caudalis (a main region for orofacial sensory neurons) project to the VPM (Magnusson et al., 1987) little is known about the role of thalamic glutamatergic signaling in orofacial pain. One test would be to target glutamate receptors or target VGLUT2 positive neurons with DREADDS. Injecting floxed DREADD constructs into the VPM/VPL of VGLUT2-cre transgenic animals would specifically inhibit glutamatergic neurons. Inducing pain after inhibiting glutamatergic neurons in the VPM/VPL would begin to determine these cells role in the behavioral and electrophysiological response.

The excitatory glutamatergic cells are present in the VPM/VPL thalamic nuclei (VGLUT2 positive) while most of the inhibitory neurons (VGAT positive) are in the Rt or ZI (Lein et al., 2007; Oertel et al., 1982). Injection of the virus resulted in transduction of many cells in the VP containing excitatory neurons with few transduced cells in the Rt or ZI. Thus, a disproportionate transduction of excitatory neurons likely resulted in attenuation of the excitatory neurons rather than attenuation of the inhibitory neurons. This attenuation of the excitatory neurons would then reduce the behavioral response.

We observed that the behavioral response was elevated between 9 and 15 minutes post formalin injection. This result is similar to that observed after injecting the TMJ or lip region with formalin (Clavelou et al., 1989; Roveroni et al., 2001). Of note, the facial rubbing parameter measured in this work was not affected by the location of the injection site. For example, the Tambeli lab demonstrated that facial rubbing was the same whether the injection was in the TMJ or masseter but head flinching was different for the two injection sites (Roveroni et al., 2001). The amplitude of the response in this study was about 5 fold less than previous studies using a similar concentration and volume of formalin (Clavelou et al., 1989; Clavelou et al., 1995; Roveroni et al., 2001). One possible explanation for the lower response is that our measurements were somewhat different because we did not include chewing like motions, as was included in the previous work (Roveroni et al., 2001).

In conclusion the results suggest that sensory orofacial responses are processed in the VP region through Gi signaling in excitatory neurons. By bridging molecular and cellular events to nociceptive signaling we can identify specific pathways in which to focus pharmacological intervention (Hucho and Levine, 2007).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Inhibition of excitatory neurons in thalamus by Gi activation attenuated orofacial nociceptive response

Inhibition of excitatory neurons in thalamus by Gi activation attenuated local field potentials

Inhibition of nociception was partially due to GIRK activation in thalamus

Orofacial pain is processed in the ventroposterior thalamus through excitatory neurons

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Xiaoju Zou, Priscilla Gillaspie-Hooks, Connie Tillberg and Gerald Hill for their excellent technical assistance. This study was supported by NIDCR grant DE022129 (PRKramer).

Abbreviations

- VP

ventroposterior thalamic complex

- Gi

inhibitory G protein

- LFP

designer receptor exclusively activated by a designer drug (DREADD) Local field potentials

- GIRK

Gi-coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium channels

- VGLUT2

glutamate vesicular transporter

- VGAT

gamma-aminobutyric acid vesicular transporter

- VPM

ventral posterior medial

- VPL

ventral posterior lateral thalamic nuclei

- GPCRs

G protein coupled receptors

- CNO

clozapine-n-oxide

- AAV8

adeno-associated virus isotype 8

- Rt

reticular thalamus

- ZI

zona incerta

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abarca C, Silva E, Sepulveda MJ, Oliva P, Contreras E. Neurochemical changes after morphine, dizocilpine or riluzole in the ventral posterolateral thalamic nuclei of rats with hyperalgesia. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;403:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00502-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acher F, Goudet C. Therapeutic potential of group III metabotropic glutamate receptor ligands in pain. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;20:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GM, Rogan SC, Abbas AI, Armbruster BN, Pei Y, Allen JA, Nonneman RJ, Hartmann J, Moy SS, Nicolelis MA, McNamara JO, Roth BL. Remote control of neuronal activity in transgenic mice expressing evolved G protein-coupled receptors. Neuron. 2009;63:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL. Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5163–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700293104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berens P, Keliris GA, Ecker AS, Logothetis NK, Tolias AS. Feature selectivity of the gamma-band of the local field potential in primate primary visual cortex. Front Neurosci. 2008;2:199–207. doi: 10.3389/neuro.01.037.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhave G, Karim F, Carlton SM, Gereau RWt. Peripheral group I metabotropic glutamate receptors modulate nociception in mice. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:417–23. doi: 10.1038/86075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G. Large-scale recording of neuronal ensembles. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:446–51. doi: 10.1038/nn1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G, Anastassiou CA, Koch C. The origin of extracellular fields and currents–EEG, ECoG, LFP and spikes. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:407–20. doi: 10.1038/nrn3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung MK, Cho YS, Bae YC, Lee J, Zhang X, Ro JY. Peripheral G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channels are involved in delta-opioid receptor-mediated anti-hyperalgesia in rat masseter muscle. Eur J Pain. 2014;18:29–38. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00343.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavelou P, Pajot J, Dallel R, Raboisson P. Application of the formalin test to the study of orofacial pain in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1989;103:349–53. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavelou P, Dallel R, Orliaguet T, Woda A, Raboisson P. The orofacial formalin test in rats: effects of different formalin concentrations. Pain. 1995;62:295–301. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00273-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti PC, Pinto-Fiamengui LM, Cunha CO, Conti AC. Orofacial pain and temporomandibular disorders: the impact on oral health and quality of life. Braz Oral Res. 2012;26(Suppl 1):120–3. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242012000700018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deupi X, Kobilka B. Activation of G protein-coupled receptors. Adv Protein Chem. 2007;74:137–66. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(07)74004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar MS, Plummer HK., 3rd Protein expression of G-protein inwardly rectifying potassium channels (GIRK) in breast cancer cells. BMC Physiol. 2006;6:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einevoll GT, Kayser C, Logothetis NK, Panzeri S. Modelling and analysis of local field potentials for studying the function of cortical circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:770–85. doi: 10.1038/nrn3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falls WM, Rice RE, VanWagner JP. The dorsomedial portion of trigeminal nucleus oralis (Vo) in the rat: cytology and projections to the cerebellum. Somatosens Res. 1985;3:89–118. doi: 10.3109/07367228509144579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Alacid L, Watanabe M, Molnar E, Wickman K, Lujan R. Developmental regulation of G protein-gated inwardly-rectifying K+ (GIRK/Kir3) channel subunits in the brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;34:1724–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipek S, Stenkamp RE, Teller DC, Palczewski K. G protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin: a prospectus. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:851–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainetdinov RR, Premont RT, Bohn LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. Desensitization of G protein-coupled receptors and neuronal functions. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:107–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanbari A, Asgari AR, Kaka GR, Falahatpishe HR, Naderi A, Jorjani M. In vivo microdialysis of glutamate in ventroposterolateral nucleus of thalamus following electrolytic lesion of spinothalamic tract in rats0. Exp Brain Res. 2014;232:415–21. doi: 10.1007/s00221-013-3749-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannakopoulos NN, Keller L, Rammelsberg P, Kronmuller KT, Schmitter M. Anxiety and depression in patients with chronic temporomandibular pain and in controls. J Dent. 2010;38:369–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J, Schnitzler A, Timmermann L, Ploner M. Gamma oscillations in human primary somatosensory cortex reflect pain perception. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustin SM, Peck CC, Wilcox SL, Nash PG, Murray GM, Henderson LA. Different pain, different brain: thalamic anatomy in neuropathic and non-neuropathic chronic pain syndromes. J Neurosci. 2011;31:5956–64. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5980-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy N, Chalus M, Dallel R, Voisin DL. Both oral and caudal parts of the spinal trigeminal nucleus project to the somatosensory thalamus in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:741–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Bozer AL, Peng YB. Inflammatory pain by carrageenan recruits low-frequency local field potential changes in the anterior cingulate cortex. Neurosci Lett. 2016;632:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoot MR, Sim-Selley LJ, Selley DE, Scoggins KL, Dewey WL. Chronic neuropathic pain in mice reduces mu-opioid receptor-mediated G-protein activity in the thalamus. Brain Res. 2011;1406:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Luo H, Green AL, Aziz TZ, Wang S. Characteristics of local field potentials correlate with pain relief by deep brain stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2016;127:2573–80. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hucho T, Levine JD. Signaling pathways in sensitization: toward a nociceptor cell biology. Neuron. 2007;55:365–76. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta MF, Frankfurter A, Harting JK. Studies of the principal sensory and spinal trigeminal nuclei of the rat: projections to the superior colliculus, inferior olive, and cerebellum. J Comp Neurol. 1983;220:147–67. doi: 10.1002/cne.902200204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh Y, Cho J. Differential Responses of Thalamic Reticular Neurons to Nociception in Freely Behaving Mice. Front Behav Neurosci. 2016;10:223. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntley GW, Vickers JC, Janssen W, Brose N, Heinemann SF, Morrison JH. Distribution and synaptic localization of immunocytochemically identified NMDA receptor subunit proteins in sensory-motor and visual cortices of monkey and human. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3603–19. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-06-03603.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K, Kobayashi T, Kumanishi T, Niki H, Yano R. Involvement of G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying K (GIRK) channels in opioid-induced analgesia. Neurosci Res. 2000;38:113–6. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(00)00144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel HA, Davila LJ. The essential role of the otolaryngologist in the diagnosis and management of temporomandibular joint and chronic oral, head, and facial pain disorders. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2014;47:301–31. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W, Klem AM, Lewis JH, Lu Z. Mechanisms of inward-rectifier K+ channel inhibition by tertiapin-Q. Biochemistry. 1999;38:14294–301. doi: 10.1021/bi991206j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanjhan R, Coulson EJ, Adams DJ, Bellingham MC. Tertiapin-Q blocks recombinant and native large conductance K+ channels in a use-dependent manner. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:1353–61. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.085928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanjhan R, Bellingham MC. Penetratin peptide potentiates endogenous calcium-activated chloride currents in Xenopus oocytes. J Membr Biol. 2011;241:21–9. doi: 10.1007/s00232-011-9359-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katritch V, Cherezov V, Stevens RC. Structure-function of the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;53:531–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-032112-135923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko MC, Lee H, Harrison C, Clark MJ, Song HF, Naughton NN, Woods JH, Traynor JR. Studies of micro-, kappa-, and delta-opioid receptor density and G protein activation in the cortex and thalamus of monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:179–86. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.050625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y. Distribution and size of cerebellar and thalamic projection neurons in the trigeminal principal sensory nucleus and adjacent nuclei in the rat. Kaibogaku Zasshi. 1995;70:156–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer PR, Stinson C, Umorin M, Deng M, Rao M, Bellinger LL, Yee MB, Kinchington PR. Lateral thalamic control of nociceptive response after whisker pad injection of varicella zoster virus. Neuroscience. 2017;356:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau D, Harte SE, Morrow TJ, Wang S, Mata M, Fink DJ. Herpes Simplex Virus VectorMediated Expression of Interleukin-10 Reduces Below-Level Central Neuropathic Pain After Spinal Cord Injury. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2012;26:889–897. doi: 10.1177/1545968312445637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lein ES, Hawrylycz MJ, Ao N, Ayres M, Bensinger A, Bernard A, Boe AF, Boguski MS, Brockway KS, Byrnes EJ, Chen L, Chen L, Chen TM, Chin MC, Chong J, Crook BE, Czaplinska A, Dang CN, Datta S, Dee NR, Desaki AL, Desta T, Diep E, Dolbeare TA, Donelan MJ, Dong HW, Dougherty JG, Duncan BJ, Ebbert AJ, Eichele G, Estin LK, Faber C, Facer BA, Fields R, Fischer SR, Fliss TP, Frensley C, Gates SN, Glattfelder KJ, Halverson KR, Hart MR, Hohmann JG, Howell MP, Jeung DP, Johnson RA, Karr PT, Kawal R, Kidney JM, Knapik RH, Kuan CL, Lake JH, Laramee AR, Larsen KD, Lau C, Lemon TA, Liang AJ, Liu Y, Luong LT, Michaels J, Morgan JJ, Morgan RJ, Mortrud MT, Mosqueda NF, Ng LL, Ng R, Orta GJ, Overly CC, Pak TH, Parry SE, Pathak SD, Pearson OC, Puchalski RB, Riley ZL, Rockett HR, Rowland SA, Royall JJ, Ruiz MJ, Sarno NR, Schaffnit K, Shapovalova NV, Sivisay T, Slaughterbeck CR, Smith SC, Smith KA, Smith BI, Sodt AJ, Stewart NN, Stumpf KR, Sunkin SM, Sutram M, Tam A, Teemer CD, Thaller C, Thompson CL, Varnam LR, Visel A, Whitlock RM, Wohnoutka PE, Wolkey CK, Wong VY, Wood M, Yaylaoglu MB, Young RC, Youngstrom BL, Yuan XF, Zhang B, Zwingman TA, Jones AR. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature. 2007;445:168–76. doi: 10.1038/nature05453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likavcanova K, Urdzikova L, Hajek M, Sykova E. Metabolic changes in the thalamus after spinal cord injury followed by proton MR spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:499–506. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher C, Slesinger PA. Emerging roles for G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:301–15. doi: 10.1038/nrn2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson KR, Clements JR, Larson AA, Madl JE, Beitz AJ. Localization of glutamate in trigeminothalamic projection neurons: a combined retrograde transport-immunohistochemical study. Somatosens Res. 1987;4:177–90. doi: 10.3109/07367228709144605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantle-St John LA, Tracey DJ. Somatosensory nuclei in the brainstem of the rat: independent projections to the thalamus and cerebellum. J Comp Neurol. 1987;255:259–71. doi: 10.1002/cne.902550209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marker CL, Lujan R, Loh HH, Wickman K. Spinal G-protein-gated potassium channels contribute in a dose-dependent manner to the analgesic effect of mu- and delta- but not kappa-opioids. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3551–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4899-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WJ, Hohmann AG, Walker JM. Suppression of noxious stimulus-evoked activity in the ventral posterolateral nucleus of the thalamus by a cannabinoid agonist: correlation between electrophysiological and antinociceptive effects. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6601–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06601.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masimore B, Kakalios J, Redish AD. Measuring fundamental frequencies in local field potentials. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;138:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews MA, Hernandez TV, Liles SL. Immunocytochemistry of enkephalin and serotonin distribution in restricted zones of the rostral trigeminal spinal subnuclei: comparisons with subnucleus caudalis. Synapse. 1987;1:512–29. doi: 10.1002/syn.890010604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni A, Panzeri S, Logothetis NK, Brunel N. Encoding of naturalistic stimuli by local field potential spectra in networks of excitatory and inhibitory neurons. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:e1000239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrovic I, Margeta-Mitrovic M, Bader S, Stoffel M, Jan LY, Basbaum AI. Contribution of GIRK2-mediated postsynaptic signaling to opiate and alpha 2-adrenergic analgesia and analgesic sex differences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:271–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0136822100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naderi A, Asgari A, Zahed R, Ghanbari A, Samandari R, Jorjani M. Estradiol attenuates spinal cord injury-related central pain by decreasing glutamate levels in thalamic VPL nucleus in male rats. Metabolic Brain Disease. 2014:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11011-014-9570-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi D, Aziz T, Carter H, Stein J. Thalamic field potentials in chronic central pain treated by periventricular gray stimulation –a series of eight cases. Pain. 2003;101:97–107. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noseda R, Kainz V, Borsook D, Burstein R. Neurochemical pathways that converge on thalamic trigeminovascular neurons: potential substrate for modulation of migraine by sleep, food intake, stress and anxiety. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103929. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel WH, Tappaz ML, Berod A, Mugnaini E. Two-color immunohistochemistry for dopamine and GABA neurons in rat substantia nigra and zona incerta. Brain Res Bull. 1982;9:463–74. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(82)90155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osikowicz M, Mika J, Przewlocka B. The glutamatergic system as a target for neuropathic pain relief. Exp Physiol. 2013;98:372–84. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.069922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SJ, Zhang S, Chiang CY, Hu JW, Dostrovsky JO, Sessle BJ. Central sensitization induced in thalamic nociceptive neurons by tooth pulp stimulation is dependent on the functional integrity of trigeminal brainstem subnucleus caudalis but not subnucleus oralis. Brain Res. 2006;1112:134–45. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.06.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick GW, Robinson MA. Collateral projections from trigeminal sensory nuclei to ventrobasal thalamus and cerebellar cortex in rats. J Morphol. 1987;192:229–36. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051920305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffinger PJ, Martin JM, Hunter DD, Nathanson NM, Hille B. GTP-binding proteins couple cardiac muscarinic receptors to a K channel. Nature. 1985;317:536–8. doi: 10.1038/317536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan KD, Falls WM. A comparison of the distribution and morphology of thalamic, cerebellar and spinal projection neurons in rat trigeminal nucleus interpolaris. Neuroscience. 1991;40:497–511. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90136-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher JA, Freedman NJ, Lefkowitz RJ. G protein-coupled receptor kinases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:653–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogan SC, Roth BL. Remote control of neuronal signaling. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:291–315. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roveroni RC, Parada CA, Cecilia M, Veiga FA, Tambeli CH. Development of a behavioral model of TMJ pain in rats: the TMJ formalin test. Pain. 2001;94:185–191. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadja R, Alagem N, Reuveny E. Gating of GIRK channels: details of an intricate, membrane-delimited signaling complex. Neuron. 2003;39:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00402-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saenz del Burgo L, Cortes R, Mengod G, Zarate J, Echevarria E, Salles J. Distribution and neurochemical characterization of neurons expressing GIRK channels in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2008;510:581–606. doi: 10.1002/cne.21810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salt TE, Binns KE. Contributions of mGlu1 and mGlu5 receptors to interactions with N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated responses and nociceptive sensory responses of rat thalamic neurons. Neuroscience. 2000;100:375–80. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00265-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salt TE, Jones HE, Copeland CS, Sillito AM. Function of mGlu1 receptors in the modulation of nociceptive processing in the thalamus. Neuropharmacology. 2014;79:405–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanziani M, Salin PA, Vogt KE, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Use-dependent increases in glutamate concentration activate presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors. Nature. 1997;385:630–4. doi: 10.1038/385630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers KK, Bennett DV, Hutt A, Williams JH, Frohlich F. Awake vs. anesthetized: layer-specific sensory processing in visual cortex and functional connectivity between cortical areas. J Neurophysiol. 2015;113:3798–815. doi: 10.1152/jn.00923.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessle BJ. Neural mechanisms and pathways in craniofacial pain. Can J Neurol Sci. 1999;26(Suppl 3):S7–11. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100000135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva E, Quinones B, Freund N, Gonzalez LE, Hernandez L. Extracellular glutamate, aspartate and arginine increase in the ventral posterolateral thalamic nucleus during nociceptive stimulation. Brain Res. 2001;923:45–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03195-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slesinger PA, Patil N, Liao YJ, Jan YN, Jan LY, Cox DR. Functional effects of the mouse weaver mutation on G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channels. Neuron. 1996;16:321–31. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steindler DA. Trigemino-cerebellar projections in normal and reeler mutant mice. Neurosci Lett. 1977;6:293–300. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(77)90087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steindler DA. Trigeminocerebellar, trigeminotectal, and trigeminothalamic projections: a double retrograde axonal tracing study in the mouse. J Comp Neurol. 1985;237:155–75. doi: 10.1002/cne.902370203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strader CD, Fong TM, Tota MR, Underwood D, Dixon RA. Structure and function of G protein-coupled receptors. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:101–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.000533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisin DL, Domejean-Orliaguet S, Chalus M, Dallel R, Woda A. Ascending connections from the caudal part to the oral part of the spinal trigeminal nucleus in the rat. Neuroscience. 2002;109:183–93. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00456-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite PME. Trigeminal sensory system. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. Academic Press; San Diego: 2004. pp. 1093–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Cao B, Yu TR, Jelfs B, Yan J, Chan RH, Li Y. Theta-frequency phase-locking of single anterior cingulate cortex neurons and synchronization with the medial thalamus are modulated by visceral noxious stimulation in rats. Neuroscience. 2015a;298:200–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZT, Yu G, Wang HS, Yi SP, Su RB, Gong ZH. Changes in VGLUT2 expression and function in pain-related supraspinal regions correlate with the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain in a mouse spared nerve injury model. Brain Res. 2015b;1624:515–24. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson CR, Switzer RC., 3rd Trigeminal projections to cerebellar tactile areas in the rat-origin mainly from n. interpolaris and n. principalis. Neurosci Lett. 1978;10:77–82. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(78)90015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen CT, Lu PL. Thalamus and pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2013;51:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.aat.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Chiang CY, Xie YF, Park SJ, Lu Y, Hu JW, Dostrovsky JO, Sessle BJ. Central sensitization in thalamic nociceptive neurons induced by mustard oil application to rat molar tooth pulp. Neuroscience. 2006;142:833–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Luo JJ, Harris S, Kennerley A, Berwick J, Billings SA, Mayhew J. Balanced excitation and inhibition: model based analysis of local field potentials. Neuroimage. 2012;63:81–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zunhammer M, Schweizer LM, Witte V, Harris RE, Bingel U, Schmidt-Wilcke T. Combined glutamate and glutamine levels in pain-processing brain regions are associated with individual pain sensitivity. Pain. 2016;157:2248–56. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo C, Yang X, Wang Y, Hagains CE, Li AL, Peng YB, Chiao JC. A digital wireless system for closed-loop inhibition of nociceptive signals. J Neural Eng. 2012;9:056010. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/9/5/056010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.