Abstract

Background

Sarcoidosis is believed to represent a genetically primed, abnormal immune response to an antigen exposure or inflammatory trigger, with both genetic and environmental factors playing a role in disease onset and phenotypic expression. In a population of firefighters with post-World Trade Center (WTC) 9/11/2001 (9/11) sarcoidosis, we have a unique opportunity to describe the clinical course of incident sarcoidosis during the 15 years postexposure and, on average, 8 years following diagnosis.

Methods

Among the WTC-exposed cohort, 74 firefighters with post-9/11 sarcoidosis were identified through medical records review. A total of 59 were enrolled in follow-up studies. For each participant, the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Diseases organ assessment tool was used to categorize the sarcoidosis involvement of each organ system at time of diagnosis and at follow-up.

Results

The incidence of sarcoidosis post-9/11 was 25 per 100,000. Radiographic resolution of intrathoracic involvement occurred in 24 (45%) subjects. Lung function for nearly all subjects was within normal limits. Extrathoracic involvement increased, most prominently joints (15%) and cardiac (16%) involvement. There was no evidence of calcium dysmetabolism. Few subjects had ocular (5%) or skin (2%) involvement, and none had beryllium sensitization. Most (76%) subjects did not receive any treatment.

Conclusions

Extrathoracic disease was more prevalent in WTC-related sarcoidosis than reported for patients with sarcoidosis without WTC exposure or for other exposure-related granulomatous diseases (beryllium disease and hypersensitivity pneumonitis). Cardiac involvement would have been missed if evaluation stopped after ECG, 48-h recordings, and echocardiogram. Our results also support the need for advanced cardiac screening in asymptomatic patients with strenuous, stressful, public safety occupations, given the potential fatality of a missed diagnosis.

Key Words: clinical course, firefighters, sarcoidosis, World Trade Center

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; EP, electrophysiologic; FDNY, Fire Department of the City of New York; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; MUSC, Medical University of South Carolina; WASOG, World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Diseases; WTC, World Trade Center

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease.1, 2, 3 The annual incidence varies widely among races/ethnicities: 11 per 100,000 in US white subjects and 36 per 100,000 in US black subjects.4, 5 In the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY), Prezant et al6 found that between 1985 and 1998, FDNY firefighters had a significantly higher annual incidence of sarcoidosis than FDNY Emergency Medical Services workers and historical control subjects. The average annual incidence in firefighters was estimated at 12.9 per 100,000, significantly greater than in Emergency Medical Services workers (0.0 per 100,000) and several times the expected rate (2.5-7.6 per 100,000 for white men in the United States).4

Following the World Trade Center (WTC) attack on 9/11/2001 (9/11), an increase in sarcoidosis was found in WTC-exposed populations,7, 8 including FDNY rescue/recovery workers.9 Between 2002 and 2015, we found an age-adjusted incidence rate of 25 per 100,000 in male FDNY rescue/recovery workers.10 By 2015, a total of 74 FDNY firefighters with new post-9/11 sarcoidosis were identified: 65 were diagnosed by using transbronchial or mediastinal biopsy results and nine by typical clinical or radiologic findings without alternate diagnosis. Possible triggering agents/antigens include particulate matter (calcium carbonate and silica) and fibers (asbestos, fibrous glass, gypsum), organic pollutants (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), gases, combustion byproducts from WTC fires, and metal dusts such as beryllium.11

Although its etiology is unknown, sarcoidosis is believed to represent a genetically primed abnormal immune response to an antigen exposure or inflammatory trigger,1 with both genetic and environmental factors playing a role in disease onset and phenotypic expression, including the distribution of organ involvement. Reports have described the clinical presentation at diagnosis, but few have described its clinical course over time.12, 13, 14

Given the extensive phenotyping of this group at diagnosis, via comprehensive medical evaluations and cohort maintenance through the FDNY WTC Health Program, we recognized an opportunity to describe the clinical course of incident sarcoidosis 15 years after WTC exposure, during the follow-up period of 2015 to 2016. In addition, because beryllium was found at the WTC site, and berylliosis is clinically indistinguishable from sarcoidosis, a secondary goal was to evaluate for beryllium sensitization.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

All 74 WTC-exposed FDNY firefighters with post-9/11 sarcoidosis were recruited via mailings and telephone calls. The Montefiore/Einstein Institutional Review Board approved the study, and participants provided written informed consent.

Clinical Criteria for Case Definition

All cases were WTC exposed and had normal chest radiographs prior to 9/11 (obtained pre-employment and biannually at medical monitoring). For biopsy-proven cases, pathology reports were reviewed to verify histologic culture-negative, noncaseating granulomas. For those without a biopsy (n = 7), charts were reviewed by two pulmonologists, and cases were included if chest CT scans showed bilateral symmetrical mediastinal/hilar adenopathy (> 1.5 cm), perilymphatic nodules, or fibrosis with bronchial distortion, without alternative etiology.15

Evaluation at Diagnosis and Follow-up

Diagnostic and follow-up evaluations were similar (Table 1) with the following additions at follow-up: serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), serum vitamin D (25-hydroxy and 1,25 dihydroxy), and urinary calcium measurements; a gadolinium-enhanced cardiac MRI; and, blood beryllium sensitization studies (IFN-γ ELISpot assay and beryllium lymphocyte proliferation test [BeLPT]) at National Jewish Health (Denver, Colorado).16, 17 If joint findings or cardiac findings were suspicious for sarcoidosis involvement, confirmation by a rheumatologist or cardiologist was required. Treatment was recorded at diagnosis and follow-up.

Table 1.

FDNY Sarcoidosis Evaluation Protocol at Diagnosis and Follow-up

| Variable | Examination Description at Diagnosis | Examination Description at Follow-up |

|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire | • Occupational, medical, family, and sarcoidosis history | • Occupational, medical, family, and sarcoidosis history |

| • Racial/ethnic background | • Racial/ethnic background | |

| • WTC exposure details | • WTC exposure details | |

| • Tobacco use history | • Tobacco use history | |

| • Review of systems | • Review of systems | |

| • Medication use | • Medication use, including current and past treatment for sarcoidosis (corticosteroids and other disease-modifying drugs) | |

| General physical examination | • Cardiac and pulmonary auscultation | • Cardiac and pulmonary auscultation |

| • Abdominal palpation | • Abdominal palpation | |

| • Lymph node, joint, and skin surveys | • Lymph node, joint, and skin surveys | |

| • Cranial nerves, motor and sensory perception assessments | • Cranial nerves, motor and sensory perception assessments | |

| Eye examination by an ophthalmologist | • Examination of eyelids | • Examination of eyelids |

| • Palpebral fissures | • Palpebral fissures | |

| • Conjunctivae for granulomas | • Conjunctivae for granulomas | |

| • Slit lamp and dilated retina exam | • Slit lamp and dilated retina exam | |

| Chest imaging | • Chest radiographs (PA and lateral) or recreated digitally from CT imaging | • Chest radiographs (PA and lateral) or recreated digitally from CT imaging |

| • Noncontrast chest CT scan | • Noncontrast chest CT scan | |

| Pulmonary function | • Spirometry | • Spirometry |

| • Lung volumes | • Lung volumes | |

| • Diffusing capacity | • Diffusing capacity | |

| Oxygen saturation | • At rest | • At rest and on exercise (6-min walk) |

| Cardiac evaluation | • 12-lead ECG | • 12-lead ECG |

| • Transthoracic echocardiogram | • Transthoracic echocardiogram | |

| • 24-h continuous recording | • 48-h continuous recording | |

| • Cardiac MRI with gadolinium | ||

| Blood analyses | • CBC count | • CBC count |

| • Metabolic panel | • Metabolic panel | |

| • Creatinine and ionized calcium | • Creatinine and ionized calcium | |

| • Liver enzyme levels | • Liver enzyme levels | |

| • Angiotensin-converting enzyme | ||

| • Vitamin D (25-hydroxy and 1,25 dihydroxy) | ||

| • Beryllium testing (IFN-γ ELISpot assay and beryllium lymphocyte proliferation test [BeLPT]) | ||

| Urinalyses | • Urinalysis (microscopic and chemistry) | • Urinalysis (microscopic and chemistry) |

| • 4-h collection for creatinine and calcium |

FDNY = Fire Department of the City of New York; PA = posterioranterior; WTC = World Trade Center.

Cardiac Studies

Advanced cardiac imaging was performed, despite the absence of symptoms or abnormal screening test results, given the potential for a cardiac fatality resulting from a missed diagnosis in firefighters and the relatively low risk of a gadolinium-enhanced cardiac MRI. Electrophysiologic (EP) studies were used for risk stratification in patients with abnormal cardiac MRIs (delayed gadolinium-enhancement of infero-lateral-basilar segments).18 Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) placement was guided by traditional primary and secondary prevention as well as consideration for the degree of abnormality on MRI. Cardiac PET scanning was performed when treatment with disease-modifying drugs was considered due to a positive EP study result or extensive disease on echocardiogram or MRI.

Organ Involvement: At Time of Diagnosis and Follow-up

For each participant, the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Diseases (WASOG) organ assessment tool19 was used to categorize sarcoidosis involvement of each organ system both at time of diagnosis and at follow-up (2015-2016). With the exception of bone/joint, a finding of “highly probable” or “at least probable” was considered diagnostic for organ involvement. For bone/joint, symptoms of arthralgias (“possible” by WASOG criterion) were upgraded to “at least probable” when there was tenderness on examination in two or more symmetrical joints, negative rheumatology serologic findings, and response to treatment with disease-modifying drugs other than corticosteroids.20 Indeterminate cardiac MRI results were considered nondiagnostic until a repeat scan was obtained 6 to 12 months later. If abnormalities were too subtle to be characterized as cardiac sarcoidosis by both radiologist and cardiologist or were no longer present or unchanged, the MRI was considered negative.

Clinical Course

Organ involvement was considered present based on WASOG criteria at follow-up and whether treatment had occurred. If new organ involvement occurred > 1 year following diagnosis but before the follow-up study (2015-2016), it was considered a follow-up finding. This scenario included one patient with cardiac involvement and eight patients with bone/joint involvement for which treatment was initiated prior to our study. For lung involvement, the clinical course was assessed by using chest imaging and classified with the use of Scadding stages (0 = normal, 1 = bilateral hilar adenopathy with normal lung parenchyma; 2 = bilateral hilar adenopathy with pulmonary infiltrates; 3 = pulmonary infiltrates without hilar adenopathy; and 4 = pulmonary fibrosis)21; pulmonary function test as percent predicted for age, height, and race22, 23; and the need for treatment.

Statistics

Demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and pulmonary function metrics were compared by using t tests, the Fisher exact test, the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, or Pearson’s χ2 test. Analyses were conducted by using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc).

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

The incidence of sarcoidosis between 9/11 and 1/2015 was 25 per 100,000. Of the 74 WTC-exposed firefighters with post-9/11 sarcoidosis, 59 (80%) were successfully recruited. All cases with biopsy-proven disease had undergone biopsy within 3 months of presentation. At diagnosis, nonparticipants were slightly older (P = .044) but did not significantly differ from study participants in other demographic characteristics (Table 2) or organ involvement (Table 3). Follow-up occurred in late 2015 to early 2016, on average 8 years after diagnosis (interquartile range, 5-11 years).

Table 2.

Comparison of Demographic Characteristics Between Nonparticipants and Study Participants

| Characteristic | Nonparticipants (n = 15) | Study Participants (n = 59) |

|---|---|---|

| WTC exposure | ||

| Arrival on the morning of 9/11 | 3 (20%) | 13 (22%) |

| Arrival in the afternoon of 9/11 | 9 (60%) | 27 (46%) |

| Arrival on 9/12 | 1 (7%) | 15 (25%) |

| Arrival from 9/13-9/24 | 2 (13%) | 4 (7%) |

| Age at sarcoidosis diagnosis, median (IQR), y | 46 (41-55) | 43 (38-47) |

| Smoking status at the time of sarcoidosis diagnosis | ||

| Current | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Former | 5 (33%) | 9 (15%) |

| Never | 10 (67%) | 49 (83%) |

| Any treatment with sarcoidosis medicationsa | 5 (33%) | 14 (24%) |

| Sarcoidosis treatment medicationsa | ||

| Corticosteroids | 5 (33%) | 13 (22%) |

| Hydroxychloroquine/methotrexate | 2 (13%) | 9 (15%) |

| TNF-α blockers | 1 (7%) | 6 (10%) |

IQR = interquartile range; TNF = tumor necrosis factor. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

Medications filled under the FDNY WTC Health Program. None of the comparisons between nonparticipants and participants were statistically significant except age (P = .044).

Table 3.

Organ Involvement for Nonparticipants (at Diagnosis) and Study Participants (at Diagnosis and Follow-up)

| Organ Involvement | Nonparticipants (n = 15) |

Study Participants (n = 59) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| At Diagnosisa | At Diagnosisb | Follow-upb | |

| Intrathoracic involvement by CT imaging | 13 (87%) | 55 (98%) | 29 (51%) |

| Radiographic stage 1 | 0 | 8 (15%) | 6 (21%) |

| Radiographic stage 2 | 12 (92%) | 43 (78%) | 19 (66%) |

| Radiographic stage 3 | 1 (8%) | 4 (7%) | 4 (14%) |

| Radiographic stage 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cardiac | 0 | 0 | 9 (16%) |

| Eyes | 1 (8%) | 3 (5%) | 3 (5%) |

| Ears/nose/throat | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Bone/joint | 2 (13%) | 4 (7%) | 9 (15%) |

| Skin | 1 (7%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Nervous System | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Liver | 1 (7%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Spleen | 0 | 3 (5%) | 3 (5%) |

| Kidney | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Calcium | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Extrathoracic lymph nodes | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 |

Organ involvement was based on World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Diseases criteria. None of the comparisons between nonparticipants and participants were statistically significant.

Nonparticipants had complete data at diagnosis with the following exceptions: skin (n = 14); eye (n = 13); spleen (n = 7); bone/joint (n = 9); cardiac (n = 12); nervous system (n = 5); and extrathoracic lymph nodes (n = 3).

In the study cohort with follow-up, all cases had complete data at diagnosis and follow-up with the following exceptions: chest CT scan at diagnosis (n = 56), at follow-up (n = 57) and at both (n = 53); eye at follow-up (n = 58); spleen at follow-up (n = 57); cardiac at follow-up (n = 57); and ear/nose/throat at follow-up (n = 57).

Clinical Course of Sarcoidosis From Diagnosis to Follow-up

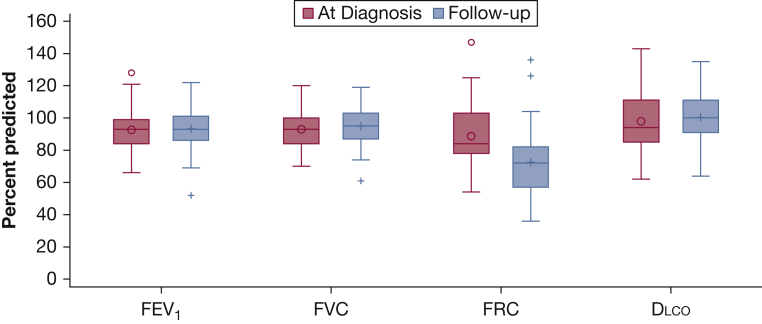

Of 59 cases, pulmonary symptoms were reported by 32 (54%) subjects at diagnosis and 35 (59%) at follow-up, whereas evidence of pulmonary disease on imaging was present in 98% at diagnosis and 51% at follow-up. Resolution of intrathoracic involvement (parenchyma and adenopathy) by follow-up occurred in 24 (45%) of 53 cases who had chest CT scans at diagnosis and follow-up (Table 3). Pulmonary function metrics were within normal limits for nearly all, changed little over time, and were not significantly different in those with or without intrathoracic involvement according to CT imaging at follow-up (all P > .05) (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Pulmonary function at diagnosis and follow-up. Average percent predicted pulmonary function among cases who had complete pulmonary data at diagnosis and follow-up: FEV1 and FVC (n = 57); Dlco (n = 41); and FRC (n = 30). All 59 cases had complete data at follow-up. Differences in pulmonary function metrics between diagnosis and follow-up were not statistically significant. Dlco = carbon monoxide diffusing capacity; FRC = functional residual capacity.

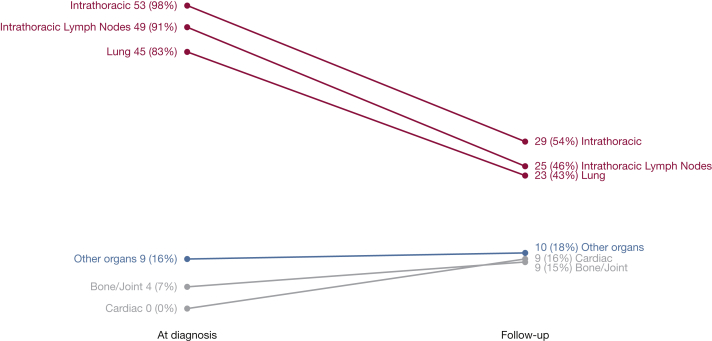

Extrathoracic involvement increased over time from 10 patients at diagnosis to 23 at follow-up (Table 3), most prominently in joints and cardiac systems, which, at follow-up affected 15% and 16% of the study population, respectively (Fig 2). Several findings at follow-up were noteworthy for not being counted as involvement according to WASOG criterion.19 These findings included 34 (58%) patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (symptoms and inflammation on sinus CT imaging but without nasal/sinus biopsy), two patients with small-fiber neuropathy (considered a para-sarcoidosis syndrome), and minor abnormalities of vitamin D/calcium homeostasis (35 cases with low 25-hydroxy- and normal 1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D levels) without hypercalcemia or hypercalciuria.

Figure 2.

Clinical course of sarcoidosis organ involvement at diagnosis and follow-up. Other organs include: eye, spleen, skin, liver, kidney, ears/nose/throat, and calcium. All 59 cases had complete data at both diagnosis and follow-up for all organs with the following exceptions: chest CT scan (n = 54); eye (n = 58); spleen (n = 57); cardiac (n = 57); and ears/nose/throat (n = 57). Serum calcium levels were assessed at diagnosis, and serum calcium and Vitamin D levels were assessed at follow-up.

Cardiac Involvement

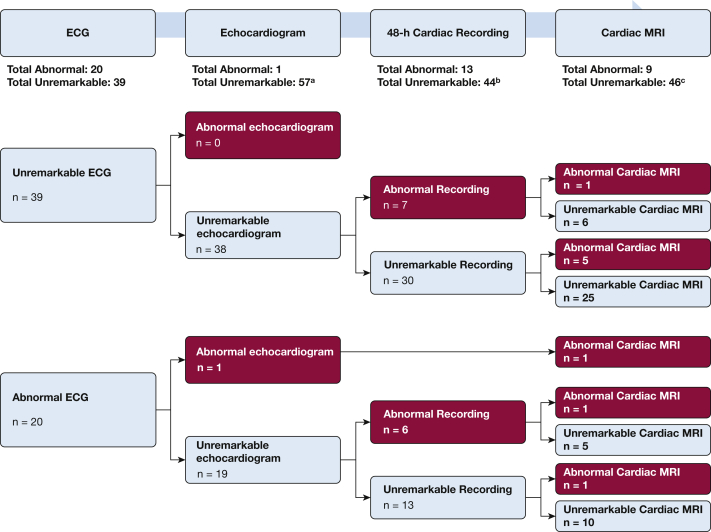

Our initial protocol at diagnosis found no evidence of cardiac involvement by symptoms, ECG, 24-h continuous recording, or echocardiogram. At follow-up, cardiac MRI was added. Thirty-one (53%) of 59 subjects reported symptoms of possible concern (eg, palpitations, dizziness/syncope), but cardiac attribution was considered likely only for one case. Figure 3 shows how many cases would have been missed at follow-up if the evaluation stopped after an earlier unremarkable test result. For example, an unremarkable ECG would have missed seven cases with abnormal continuous cardiac recording and six cases with abnormal cardiac MRI. Abnormal findings included: ECGs (eg, right ventricular strain, right bundle branch block or intermittent complete atrioventricular block); echocardiogram (left ventricular ejection fraction < 45%); 48-h recording (short runs of ectopy, usually supraventricular, and four with variable block [second-degree, right bundle branch or intermittent complete atrioventricular block]); and cardiac MRI (delayed gadolinium-enhancement of infero-lateral-basilar segments). Eight of the nine cases with abnormal cardiac MRI underwent an EP study; two had inducible ventricular tachycardia, of which one had the low ejection fraction noted on both echocardiogram and MRI but a negative cardiac PET scan. One case with a negative EP study and normal echocardiogram had extensive scarring on cardiac MRI with a positive cardiac PET scan.

Figure 3.

Cardiac assessments at follow-up examination for sarcoidosis cases. Cardiac evaluation at follow-up demonstrating how many cases would have been missed if the evaluation stopped after an earlier test result was unremarkable. For example, an unremarkable ECG would have missed seven cases with abnormal continuous cardiac recording and six cases with abnormal cardiac MRI. The same would have occurred if the evaluation stopped after both an unremarkable ECG and echocardiogram. An abnormal ECG with an unremarkable echocardiogram would have missed six cases with abnormal continuous cardiac recording and two cases with abnormal cardiac MRI. aOne case missing an echocardiogram. bTwo cases missing cardiac recordings. One case missing an echocardiogram, had an unremarkable 48-h cardiac recording (not shown) and a missing cardiac MRI. cFour cases missing cardiac MRIs.

Bone/Joint Involvement

Eight cases presented with symmetrical polyarticular arthritis involving swelling and tenderness of the small joints, of which five also involved large joints. One additional case had asymptomatic vertebral bone involvement. In all cases, serum markers for other autoimmune diseases, in particular rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, were negative on initial presentation.

Additional Studies (ACE and Beryllium)

None of the subjects had evidence of beryllium sensitization. At follow-up, mean ACE levels were 47 U/L (interquartile range, 30 U/L-62 U/L); nine (15%) had mildly elevated ACE levels (> 67 U/L).

Treatment

The average number of organs involved decreased by 0.59, from 1.88 to 1.29 organs per patient after an average of 8 years of follow-up. Five (8%) cases were treated with oral corticosteroids for dyspnea with reductions in pulmonary function. Eight cases with joint symptoms underwent a stepwise treatment algorithm to achieve adequate disease control,2 ultimately with hydroxychloroquine and methotrexate in one case and tumor necrosis factor-α blockers in seven cases. For the entire study cohort, regardless of why treatment was initiated, the course of pulmonary functions (FEV1, FVC, functional residual capacity, and carbon monoxide diffusing capacity) was similar in patients who were ever treated with any disease-modifying drug compared with those who were never treated (all P > .05). Among 24 cases who demonstrated resolution of intrathoracic involvement at follow-up, six were treated. Three cases with cardiac sarcoidosis were treated with an ICD: two for inducible ventricular tachycardia on EP study and one for severe scarring on MRI. One of the three had a positive cardiac PET scan and was treated with corticosteroids. In the three cases with ICDs, none have discharged, and all patients (study participants and nonparticipants) remain alive as of 2017.

Discussion

We described the phenotypic expression of sarcoidosis at diagnosis and follow-up in a relatively homogeneous cohort of WTC-exposed firefighters. Nearly 68% were highly exposed (present on 9/11), and none had evidence of beryllium sensitization. Consistent with recent studies in patients with sarcoidosis without WTC exposure,12, 24, 25 the median age at diagnosis was 43 years, nearly every case had intrathoracic involvement (predominantly radiographic stage I and II), and 45% had resolution of intrathoracic findings. WTC sarcoidosis differed, however, in terms of its extrathoracic manifestations, demonstrating more joint and cardiac disease and less hypercalcemia, ocular, and skin involvement than usually found in white male patients with sarcoidosis but without WTC exposure. This outcome is interesting because other exposure-related granulomatous diseases (chronic beryllium disease and hypersensitivity pneumonitis) are confined to the lungs, whereas this study shows that WTC sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease.

A Case-Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis (ACCESS), a multicenter study on sarcoidosis, found that white patients developed an average of 0.17 new organ involvements over a 2-year follow-up.13 In the cohort from the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), white male subjects developed an average of 0.8 new organ involvements over a 6-year follow-up.14 In contrast, in the present study, the average number of involved organs decreased by 0.59, from 1.88 to 1.29 organs per patient, after an average of 8 years of follow-up. Organ assessment in our study, however, included extensive cardiac studies that were not performed in the two aforementioned studies. If we excluded asymptomatic patients who were found to have cardiac sarcoidosis, rates of new organ involvement would have decreased by 0.74, from 1.88 to 1.13 organs per patient.

More than 76% (n = 45) of the present cohort did not receive treatment for sarcoidosis. This finding is higher than described in the MUSC cohort, in which nearly 40% did not receive treatment.14 Our percent treated (34%), however, is similar to the MUSC-treated subset of white subjects (35%). Treatment occurred due to dyspnea with declining pulmonary function, joint symptoms, or potentially life-threatening cardiac or neurologic involvement.

As far as bone/joint, although our criteria for organ involvement did not technically meet WASOG criteria (“possible” upgraded to “at least probable”), the instrument does acknowledge that multiple lesser manifestations may raise the probability of organ involvement. Therefore, joint involvement was deemed “probable” if the patient had symmetrical arthritis with swelling and morning stiffness, with the assumption that this qualified as inflammatory rather than osteoarthritis. Furthermore, if those patients with clinical inflammatory polyarthritis simultaneously demonstrated negative rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, and had radiographs without the typical erosive changes of rheumatoid arthritis at the time of initial rheumatologic evaluation, the arthritis was assumed to be related to the underlying sarcoidosis. In addition, response to treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs other than corticosteroids alone, such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, and/or anti-tumor necrosis factor biologic therapy, provided further support for sarcoidosis-related bone/joint involvement.

Our study has several limitations and strengths. First, the FDNY cohort was entirely composed of male firefighters, all but one of whom was white. This homogeneity precludes us from drawing conclusions about the clinical course of sarcoidosis in WTC-exposed female subjects, non-white subjects, and non-firefighters, although our previous findings have proven to be generalizable to more diverse WTC-exposed cohorts.7, 8 Close monitoring of this study cohort, however, did allow us to be certain that all participants were WTC exposed; had granulomatous disease that was not due to beryllium sensitization; and that sarcoidosis occurred post-exposure because we had pre-employment and pre-exposure medical examinations, including chest radiographs, on all FDNY firefighters. Second, although the majority of those affected participated, 20% of the base cohort declined follow-up. Although these patients were similar at diagnosis, we cannot determine whether their disease was stable or in which direction it evolved. An important study strength was the long-term follow-up (mean, 8 years) of participants.

Another strength was the standardization of the evaluation protocol for organ involvement at diagnosis and follow-up, which was independent of symptoms. This approach allowed us to more accurately determine the prevalence of cardiac involvement, because all patients had a full assessment, even those who were asymptomatic or had normal ECGs. Of particular significance is the relatively high percentage found to have unrecognized cardiac involvement. Clinically evident cardiac sarcoidosis has been noted in only 2% to 7% of patients with sarcoidosis with manifestations, including conduction abnormalities, ventricular arrhythmias, and heart failure, whereas the rate in asymptomatic patients is unknown.26, 27 Cardiac sarcoidosis was clinically detected in 16% of the study cohort at follow-up. We cannot comment on whether cardiac involvement was present at the initial diagnostic evaluation, or its annual incidence, because cardiac MRI was only added to the follow-up protocol. We believe that our initial diagnostic protocol likely underestimated its frequency, because in 56% of the cases with a positive cardiac MRI at follow-up, the other cardiac studies (ECG, echocardiogram, and 48-h continuous recording) repeated at follow-up remained normal. This finding is in contrast to the study by Mehta et al,27 which reported a specificity of 87% and a sensitivity of 100% for diagnosing cardiac sarcoidosis with at least one abnormal screening test (ECG, 24-h recording, or echocardiogram) and/or significant cardiac symptoms. Our data suggest that cardiac sarcoidosis may frequently be missed, even when results of screening tests are normal (Fig 3). The prognostic significance, however, of a positive cardiac MRI in this setting requires further studies with larger enrollment and longer follow-up.

Current guidelines recommend cardiac MRI only in patients with symptoms, abnormal ECG, or abnormal echocardiogram.28, 29, 30, 31 We believe that our results support the need for advanced cardiac screening in asymptomatic patients with strenuous, high-stress, public safety occupations, although additional follow-up is warranted. Firefighting is extremely stressful; firefighters operate at workloads ≥ 12 METs, in high heat and potentially toxic environments leading to maximum heart rates, high catecholamine levels, and an increased rate of myocardial infarction.28, 29, 30, 31 In addition, should a firefighter experience a cardiac event while in this environment, it would place not only that firefighter but also other firefighters on that team and civilians being rescued at grave risk. A large prospective study would be needed to determine if screening patients with sarcoidosis, with or without symptoms, by using cardiac MRI, and treating those with positive results, produces a measureable benefit on outcomes. For now, we must rely on individualized clinical risk-benefit analyses.

Conclusions

We describe the clinical course of sarcoidosis in this WTC-exposed firefighter cohort followed for many years. Intrathoracic involvement resolved in 45% of patients. Pulmonary function was normal in nearly all subjects and remained stable in all but one. Stability of pulmonary function was not associated with radiographic stage at diagnosis or follow-up, or with treatment. Extrathoracic disease was more prevalent than reported for sarcoidosis without WTC exposure or for other exposure-related granulomatous diseases (beryllium disease and hypersensitivity pneumonitis). Treatment was most often instituted for symptomatic joint involvement or potentially life-threatening cardiac or neurologic involvement rather than for lung, ocular, or skin involvement. Given the limited number of longitudinal studies of sarcoidosis, we hope these findings will help guide the management of all patients with sarcoidosis, including those with WTC exposure.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: All authors have participated in at least one aspect of the study (design, recruitment, testing, analyses, and writing); read and approved the manuscript for submission; and accept responsibility for the manuscript’s contents.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: None declared.

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

*Writing Committee Members for the FDNY Sarcoidosis Clinical Research Group: Vasilios Christodoulou, BA (Bureau of Health Services, Fire Department of the City of New York, Brooklyn, NY); Zachary Hena, MD (Cardiology Division, Department of Pediatrics, Montefiore Medical Center and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY); Steven M. Plotycia, MD (New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai, Department of Ophthalmology, New York, NY); Israa Soghier, MD (Pulmonary & Critical Care Division, Jacobi Medical Center and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY); David Gritz, MD (Department of Ophthalmology, The Johns Hopkins Wilmer Eye Institute, Baltimore, MD); Dianne S. Acuna, MD (Bureau of Health Services, Fire Department of the City of New York, Brooklyn, NY); Michael D. Weiden, MD (Pulmonary & Critical Care Division, Department of Medicine, NYU School of Medicine, New York, NY; and Bureau of Health Services, Fire Department of the City of New York, Brooklyn, NY); Anna Nolan, MD (Pulmonary & Critical Care Division, Department of Medicine, NYU School of Medicine, New York, NY; and Bureau of Health Services, Fire Department of the City of New York, Brooklyn, NY); Keith Diaz, MD (Bureau of Health Services, Fire Department of the City of New York, Brooklyn, NY); Viola Ortiz, MD (Bureau of Health Services, Fire Department of the City of New York, Brooklyn, NY); and Kerry Kelly, MD (Bureau of Health Services, Fire Department of the City of New York, Brooklyn, NY).

Other contributions: During this study, Thomas K. Aldrich, MD, died of pancreatic cancer. He was more than just the principal investigator. He was a mentor and friend to all of us. He deeply believed in the importance of our work characterizing the health effects after the WTC attack on 9/11. He will be missed but never forgotten. We also thank Neeti Parikh, MD, for her eye examinations in this study.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: Funding for this study came from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [Grant U01-OH010993 and Contracts 200-2011-39383, 200-2011-39378, 200-2017-93326, and 200-2017-93426].

Contributor Information

David J. Prezant, Email: david.prezant@fdny.nyc.gov.

FDNY Sarcoidosis Clinical Research Group*:

Vasilios Christodoulou, Zachary Hena, Steven M. Plotycia, Israa Soghier, David Gritz, Dianne S. Acuna, Michael D. Weiden, Anna Nolan, Keith Diaz, Viola Ortiz, and Kerry Kelly

References

- 1.Valeyre D., Prasse A., Nunes H., Uzunhan Y., Brillet P.Y., Muller-Quernheim J. Sarcoidosis. Lancet. 2014;383(9923):1155–1167. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60680-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iannuzzi M.C., Rybicki B.A., Teirstein A.S. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2153–2165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Regan A., Berman J.S. Sarcoidosis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(9) doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-9-201205010-01005. ITC5-1, ITC5-2, ITC5-3, ITC5-4, ITC5-5, ITC5-6, ITC5-7, ITC5-8, ITC5-9, ITC5-10, ITC15-11, ITC15-12, ITC15-13, ITC15-14, ITC15-15; quiz ITC15-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rybicki B.A., Major M., Popovich J., Jr., Maliarik M.J., Iannuzzi M.C. Racial differences in sarcoidosis incidence: a 5-year study in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(3):234–241. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rybicki B.A., Maliarik M.J., Major M., Popovich J., Jr., Iannuzzi M.C. Epidemiology, demographics, and genetics of sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Infect. 1998;13(3):166–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prezant D.J., Dhala A., Goldstein A. The incidence, prevalence, and severity of sarcoidosis in New York City firefighters. Chest. 1999;116(5):1183–1193. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.5.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jordan H.T., Stellman S.D., Prezant D., Teirstein A., Osahan S.S., Cone J.E. Sarcoidosis diagnosed after September 11, 2001, among adults exposed to the World Trade Center disaster. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53(9):966–974. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31822a3596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crowley L.E., Herbert R., Moline J.M. “Sarcoid like” granulomatous pulmonary disease in World Trade Center disaster responders. Am J Ind Med. 2011;54(3):175–184. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Izbicki G., Chavko R., Banauch G.I. World Trade Center “sarcoid-like” granulomatous pulmonary disease in New York City Fire Department rescue workers. Chest. 2007;131(5):1414–1423. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Webber MP, Yip JY, Zeig-Owens R, et al. Post-9/11 sarcoidosis in WTC-exposed firefighters and emergency medical service workers [published online ahead of print June 7, 2017]. Respir Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Lioy P.J., Weisel C.P., Millette J.R. Characterization of the dust/smoke aerosol that settled east of the World Trade Center (WTC) in lower Manhattan after the collapse of the WTC 11 September 2001. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(7):703–714. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baughman R.P., Teirstein A.S., Judson M.A. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Cared Med. 2001;164(10 pt 1):1885–1889. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2104046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Judson M.A., Baughman R.P., Thompson B.W. Two year prognosis of sarcoidosis: the ACCESS experience. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2003;20(3):204–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Judson M.A., Boan A.D., Lackland D.T. The clinical course of sarcoidosis: presentation, diagnosis, and treatment in a large white and black cohort in the United States. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2012;29(2):119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valeyre D., Bernaudin J.F., Uzunhan Y. Clinical presentation of sarcoidosis and diagnostic work-up. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;35(3):336–351. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1381229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreiss K., Newman L.S., Mroz M.M., Campbell P.A. Screening blood test identifies subclinical beryllium disease. J Occup Med. 1989;31(7):603–608. doi: 10.1097/00043764-198907000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin A.K., Mack D.G., Falta M.T. Beryllium-specific CD4+ T cells in blood as a biomarker of disease progression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(5) doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.022. 1100-1106.e1101-1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birnie D.H., Sauer W.H., Bogun F. HRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of arrhythmias associated with cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11(7):1305–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Judson M.A., Costabel U., Drent M. The wasog sarcoidosis organ assessment instrument: an update of a previous clinical tool. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2014;31(1):19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loupasakis K., Berman J., Jaber N. Refractory sarcoid arthritis in World Trade Center-exposed New York City firefighters: a case series. J Clin Rheumatol. 2015;21(1):19–23. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scadding J.G. Prognosis of intrathoracic sarcoidosis in England. A review of 136 cases after five years' observation. BMJ. 1961;2(5261):1165–1172. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5261.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hankinson J.L., Odencrantz J.R., Fedan K.B. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general US population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(1):179–187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller A., Thornton J.C., Warshaw R., Anderson H., Teirstein A.S., Selikoff I.J. Single breath diffusing capacity in a representative sample of the population of Michigan, a large industrial state. Predicted values, lower limits of normal, and frequencies of abnormality by smoking history. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;127(3):270–277. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.127.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ungprasert P., Carmona E.M., Utz J.P., Ryu J.H., Crowson C.S., Matteson E.L. Epidemiology of sarcoidosis 1946-2013: a population-based study. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2016;91(2):183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Girvin F., Zeig-Owens R., Gupta D. Radiologic features of World Trade Center-related sarcoidosis in exposed NYC fire department rescue workers. J Thorac Imaging. 2016;31(5):296–303. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hulten E., Aslam S., Osborne M., Abbasi S., Bittencourt M.S., Blankstein R. Cardiac sarcoidosis-state of the art review. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2016;6(1):50–63. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2015.12.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehta D., Lubitz S.A., Frankel Z. Cardiac involvement in patients with sarcoidosis: diagnostic and prognostic value of outpatient testing. Chest. 2008;133(6):1426–1435. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malley K.S., Goldstein A.M., Aldrich T.K. Effects of fire fighting uniform (modern, modified modern, and traditional) design changes on exercise duration in New York City Firefighters. J Occup Environ Med. 1999;41(12):1104–1115. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199912000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Heimburg E.D., Rasmussen A.K., Medbo J.I. Physiological responses of firefighters and performance predictors during a simulated rescue of hospital patients. Ergonomics. 2006;49(2):111–126. doi: 10.1080/00140130500435793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang C.J., Webb H.E., Garten R.S., Kamimori G.H., Acevedo E.O. Psychological stress during exercise: lymphocyte subset redistribution in firefighters. Physiol Behav. 2010;101(3):320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kales S.N., Soteriades E.S., Christophi C.A., Christiani D.C. Emergency duties and deaths from heart disease among firefighters in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(12):1207–1215. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]