Abstract

Background

Endobronchial ultrasonographically guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) of thoracic structures is a commonly performed tissue sampling technique. The use of an inner-stylet in the EBUS needle has never been rigorously evaluated and may be unnecessary.

Methods

In a prospective randomized single-blind controlled clinical trial, patients with a clinical indication for EBUS-TBNA underwent lymph node sampling using both with-stylet and without-stylet techniques. Sample adequacy, diagnostic yield, and various cytologic quality measures were compared.

Results

One hundred twenty-one patients were enrolled, with 194 lymph nodes sampled, each using both with-stylet and without-stylet techniques. There was no significant difference in sample adequacy or diagnostic yield between techniques. The without-stylet technique resulted in adequate samples in 87% of the 194 study lymph nodes, which was no different from the with-stylet adequacy rate (82%; P = .371). The with-stylet technique resulted in a diagnosis in 50 of 194 samples (25.7%), which was similar to the without-stylet group (49 of 194 [25.2%]; P = .740). There was a high degree of concordance in the determination of adequacy (84.0%; 95% CI, 78.1-88.9) and diagnostic sample generation (95.4%; 95% CI, 91.2-97.9) between the two techniques. A similar qualitative number of lymphocytes, malignant cells, and bronchial respiratory epithelia were recovered using each technique.

Conclusions

Omitting stylet use during EBUS-TBNA does not affect diagnostic outcomes and reduces procedural complexity.

Trial Registry

ClinicalTrials.Gov: No. NCT 02201654; URL:www.clinicaltrials.gov.

Key Words: EBUS-TBNA, interventional bronchoscopy, pathology, stylet

Endobronchial ultrasonographic transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) of thoracic tissues is a valuable tool that facilitates diagnosis and staging of pathologic chest conditions. Contemporary techniques demonstrate an improved safety profile and a similar diagnostic yield compared with surgical mediastinoscopy.1, 2, 3 With these benefits, there is great interest in streamlining EBUS protocols while maintaining procedural efficacy and safety. In the past 10 years, a substantial body of literature has evaluated methods to optimize EBUS-TBNA. The use of rapid on-site cytopathology (ROSE) to provide real-time feedback of sample quality improves sample adequacy and overall procedural efficiency.4 The number of optimal minimum passes at each nodal station (four passes) to obtain sufficient tissue for genomic testing has been determined.5 Two trials found no significant differences in diagnostic yield in samples obtained with a 21-gauge needle vs a 22-gauge needle, and trials of next-generation needle technology are ongoing.6, 7 Studies examining the impact of deep vs moderate sedation on diagnostic yield have reported variable results.8, 9 Finally, a recent randomized trial evaluating the need for suction during EBUS-TBNA found that foregoing suction use did not affect diagnostic outcomes.10 This suggests that the commonly used procedural step of suction may not offer benefit while prolonging procedural time.

During traditional EBUS-TBNA, the biopsy needle enters the lymph node with its inner lumen occluded with a metal stylet, which is subsequently removed after the needle enters the targeted node. This theoretically prevents airway cells, bronchial wall debris, and blood from filling the inner lumen and degrading sample quality. However, this requires the insertion and removal of an inner stylet through the biopsy needle several times during the procedure. At least two trials in the gastroenterology literature have found that omitting the use of the stylet did not affect diagnostic outcomes in endoscopic ultrasonographically guided biopsies of lesions adjacent to the gastrointestinal tract.11, 12 Additionally, conventional TBNA using a Wang cytology needle (CONMED) does not involve a stylet, establishing a precedent for this trial.

We hypothesized that inserting and removing a metal stylet in the biopsy needle may be an unnecessary procedural step during EBUS-TBNA. We subsequently performed a prospective randomized clinical trial to evaluate diagnostic outcomes of EBUS-TBNA performed without a stylet compared with a traditional with-stylet protocol.

Methods

Study Recruitment and Inclusion Criterion

Consecutive adult patients with a clinical indication for EBUS-TBNA referred to the interventional pulmonology (IP) service at the Johns Hopkins Hospital were offered enrollment into this study. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, age < 18 years, standard exclusions for EBUS-TBNA (coagulopathy, clinical stability), and inability to give informed consent. Enrollment occurred from June 2014 to January 2015, with 152 patients screened and 121 patients enrolled over the 8-month study period.

Study Design

This trial analyzed the diagnostic performance of EBUS-TBNA completed with and without a stylet on a per lymph node basis. Each node in our study was sampled using both techniques, with a total of four needle passes (two passes per technique). To control for any first-pass effect, each node was randomized to technique order, and techniques were alternated for the subsequent three passes. The primary outcomes were sample adequacy and diagnostic yield between the two techniques at each lymph node. Using conservative assumptions, we calculated that 199 lymph nodes would provide sufficient power for a 10% noninferiority margin.

EBUS-TBNA

At the time of bronchoscopy, each participant was randomly assigned to technique performance order. The cytotechnologist in the room at the time of the bronchoscopy was blinded to stylet use for the entire EBUS procedure and ROSE evaluation. Patients received deep sedation and were ventilated with a laryngeal mask airway. EBUS-TBNA was performed by an IP attending physician or IP fellow under the guidance of an attending IP physician (L. Y., D. F. K., H. L., R. S., S. A.). The procedure was performed using an Olympus BF-UC180F EBUS bronchoscope. To avoid cross-contamination, each technique used its own independent 21-gauge MAJ-1414 ViziShot needle (Olympus). For without-stylet passes, the stylet was removed prior to inserting the biopsy apparatus into the working channel of the bronchoscope. With-stylet passes were performed in the standard fashion. Suction was used on all passes, with the exception of instances in which blood was aspirated into the suction syringe or the cytotechnician reported excessively bloody samples intraoperatively independent of stylet use. Lymph nodes were sampled in an appropriate order determined by the EBUS operators, starting with the N3 node in cases of lung cancer staging. Only the first two nodes sampled during a procedure were included in the study. Additional clinically indicated passes at the first two stations (if additional tissue was required for molecular markers) or subsequent stations were not analyzed. Each study node received four total needle passes (two with stylet, two without stylet in alternating order). Each pass consisted of 10 needle thrusts. Regardless of technique, a stylet was used to facilitate sample retrieval by the blinded on-site cytotechnician during ROSE for adequacy. Final determination of adequacy, diagnosis, and sample quality was made independently at a later date by a blinded off-site study pathologist (P. I.).

Pathologic Scoring

Each study pass was graded for adequacy and pathologic diagnosis. Adequate samples were defined as passes yielding sufficient lymphoid or pathologic tissue for diagnosis. Adequate samples received specific diagnoses, which were then sorted into three categories (benign lymphoid tissue, granulomatous inflammation, or malignancy). For each lymph node, the two passes of each technique were combined when determining adequacy and diagnostic results (ie, for a given technique, if only one of the two passes yielded adequate tissue, the technique was still considered adequate for that lymph node).

In addition to this basic grading, each pass was further evaluated with assessments of the quality of the sample. We analyzed each pass for the qualitative amount of lymphocytes or tumor recovered, the amount of bronchiolar or respiratory epithelia present, the presence of macrophages (presumably an airway contaminant), or grossly bloody/acellular samples.

Data Analysis

To determine the difference in both adequacy and diagnostic samples between the with-stylet and without-stylet groups, paired t test analysis was performed. The percentage of agreement between methods was calculated by adding the overall number of positive and negative test results in agreement and dividing by the total number of tests. For all variables that were dichotomous in nature, logistic regression analysis was performed to assess a difference between the with-stylet and without-stylet methods. When variables were categorical, multinomial logistic regression was used to assess the difference between methods. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata, version 14 (Stata LP).

Safety Monitoring

This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB No.: NA_00082763) and was registered with Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 02201654). Scheduled follow-up calls after bronchoscopy and an electronic chart review catalogued any adverse events.

Results

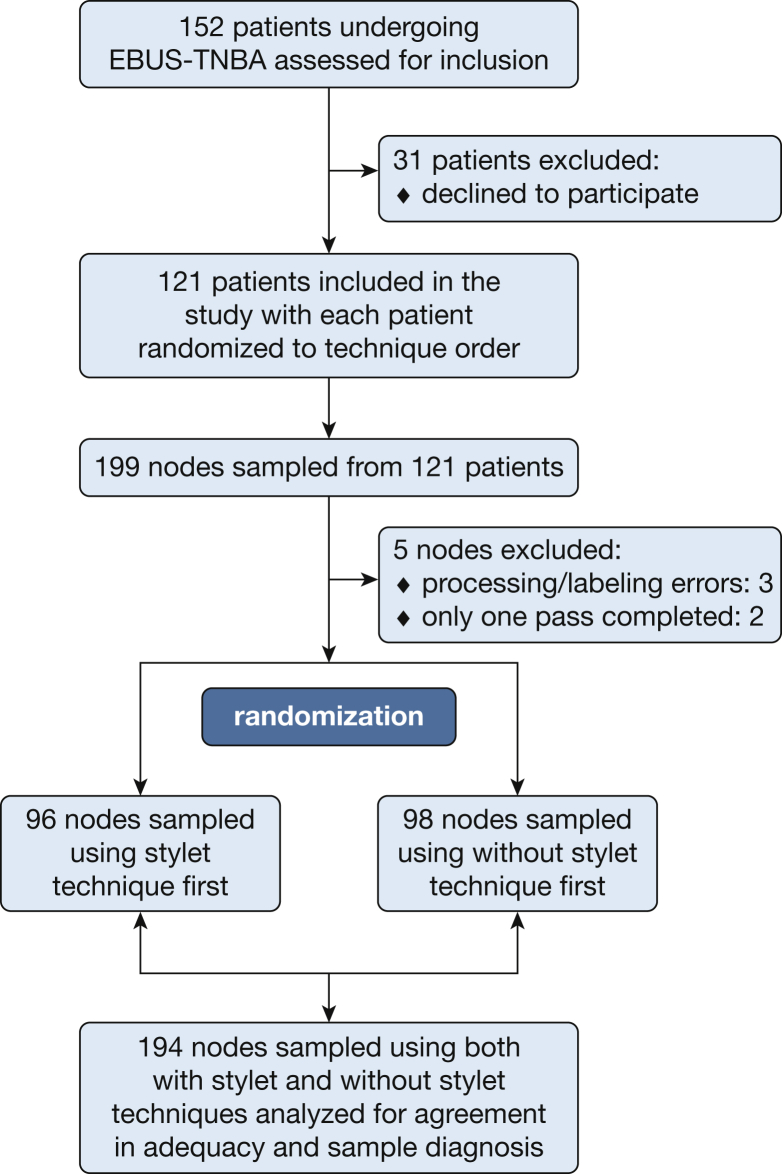

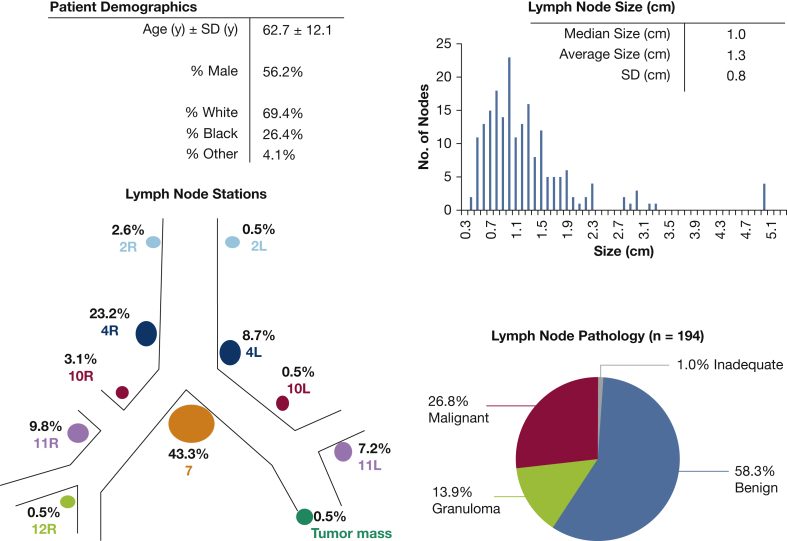

One hundred fifty-two patients were screened for inclusion, with 121 patients eventually enrolled in the study and 199 lymph nodes sampled using both with-stylet and without-stylet techniques. Patients were excluded because of refusal or inability to consent. No other patients met the exclusion criteria defined at the outset of the study. Logistical errors precluded analysis in five nodal samples, leaving 194 lymph nodes with complete data available for analysis. Study enrollment, exclusion, randomization, and analysis are summarized in a flowchart (Fig 1). Patient demographics and lymph node characteristics were typical for the population referred for EBUS-TBNA at our institution (Fig 2). Using all study data, including pooled cell block tissue, we determined a diagnosis for the study lymph nodes: 58.2% were benign, 26.8% were malignant, 13.9% had granulomatous inflammation, and 1.0% consisted of inadequate tissue (Fig 2). Randomization ensured that half the lymph nodes were sampled with the with-stylet technique first and half with the without-stylet technique first, controlling for any effect of pass order.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart detailing screening and exclusion, as well as total patients and lymph nodes included in the final analysis. EBUS-TBNA = endobronchial ultrasonographically guided transbronchial needle aspiration.

Figure 2.

Descriptive statistics for the patients and the 194 study lymph nodes. The pathologic data displayed here were determined using all available tissue from both techniques and the pooled cell block.

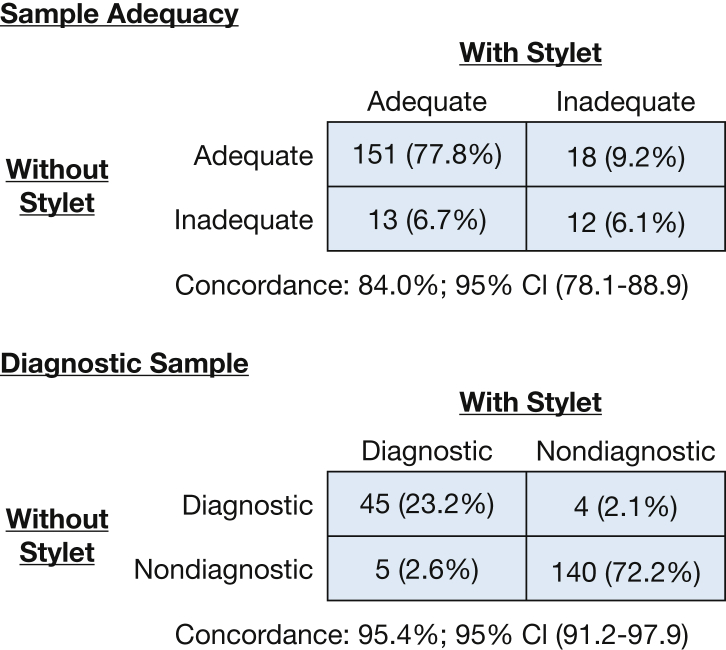

No statistically significant differences in sample adequacy or diagnostic yield were detected when comparing the two techniques. The without-stylet technique resulted in adequate samples in 87% of the 194 study lymph nodes, which was not significantly different than the with-stylet adequacy rate (82%) (P = .371). The with-stylet technique resulted in a diagnosis in 50 of 194 samples (25.7%), which was not significantly different than the without-stylet group in which 49 of 194 (25.2%) revealed a diagnosis (P = .740). There was a high degree of concordance in the determination of adequacy between the two techniques (concordance, 84.0%; 95% CI, 78.1-88.9) (Fig 3). There was similar high concordance in diagnostic sample generation between the two techniques (concordance, 95.4%; 95% CI, 91.2-97.9) (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the ability of with-stylet and without-stylet techniques to generate adequate and diagnostic samples among the 194 study lymph nodes. Each technique had excellent agreement with the complementary technique, which was reflected in the high concordance values.

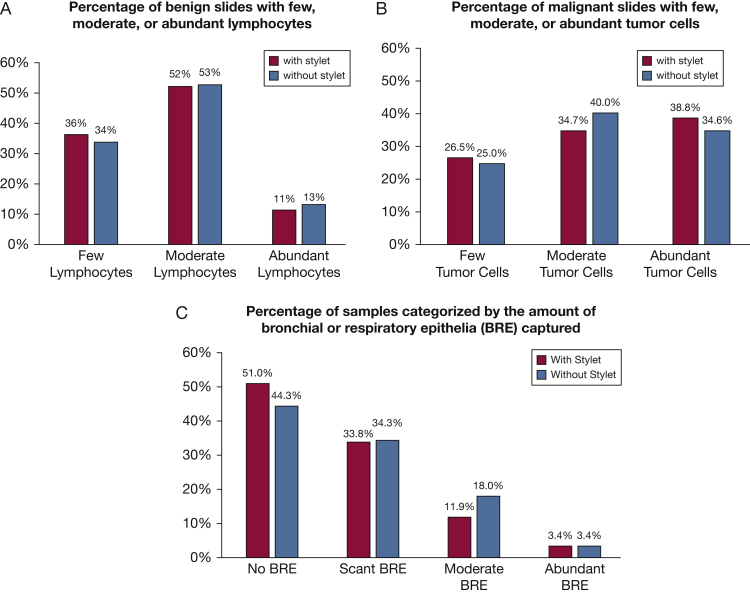

We further analyzed individual pass/slide data on a variety of quality metrics. For the subsets of slides that contained malignant or benign lymphocytes, we determined the qualitative number of the relevant cells present on each slide. We then compared the slides generated using a with-stylet technique and those generated with a without-stylet technique to determine if stylet use led to improvement in the quantity of cells recovered. Stylet use produced no significant improvement in the number of lymphocytes recovered from slides with benign lymphocytes (P = .79) (Fig 4A), the number of tumor cells recovered from slides with malignant tissue (P = .84) (Fig 4 B), or the overall number of bronchial or respiratory epithelia seen (P = .77) (Fig 4C). There was no significant difference between techniques in the generation of samples with a high number of airway macrophages (3.35% of with-stylet slides; 3.86% of without-stylet slides; P = .70) or in the generation of samples that were grossly bloody/acellular (1.54% of with-stylet slides, 1.80% of without-stylet slides, P = .78). Pass order was not associated with adequate sample generation (first-pass slide adequacy rate, 84.5%; second-pass slide adequacy rate, 86.1%; P = .67).

Figure 4.

Quality assessments of tissue obtained with each technique. A, Stylet use did not improve recovery of lymphocytes from passes categorized as benign lymphocytes (multinomial logistic regression P = .79). B, There was no improvement in the recovery of malignant cells (P = .84). C, There is also no difference in bronchial and respiratory epithelium recovered (P = .77). BRE = bronchial and respiratory epithelia.

Standard safety screening after endoscopy revealed only one procedure-related adverse event: a patient with severe COPD in whom wheezing developed after the procedure. This patient was observed for 24 hours then discharged home without further complications. There was no detected damage to the EBUS scope and working channel during the duration of the study.

Discussion

This randomized trial of a simplified stylet-free EBUS-TBNA protocol demonstrated performance that was comparable to standard EBUS-TBNA. Both procedures had very similar rates of generating adequate and diagnostically useful samples and a high degree of concordance when their performance was assessed head to head on the individual lymph node level. Furthermore, we did not detect any increase in the qualitative number of lymphocytes, malignant cells, or bronchiolar and respiratory epithelia recovered from passes obtained with a stylet. These findings argue against a meaningful benefit with stylet use.

What might be gained by eliminating stylet use? Standard EBUS-TBNA sampling of lymph nodes involves at least 15 steps. Eliminating stylet use simplifies the procedure by removing one of these steps. Although each loading/unloading cycle of the stylet takes only seconds, this step is repeated at each pass and at each sampling site. Given the high costs of procedural time ($10-$60/min) and busy clinical schedules, even small reductions in procedural duration may be important.13 Additionally, the metal-metal friction that occurs with stylet insertion and removal is known to deposit microscopic metal particles in the biopsy bed.14 Although the long-term effects and clinical relevance of this finding are unclear, if no benefit accompanies stylet use, this potential exposure should be avoided. Some have raised concern that omitting stylet use may damage the working channel of the bronchoscope, as the blunt tip of the stylet does slightly protrude past the needle, theoretically offering protection to the working channel of the bronchoscope. However, we observed no instances of channel damage during the trial, likely making this theoretical concern not clinically relevant. Finally, it should also be noted that the stylet may still be required for the cytotechnician to remove the sample from the needle; thus the stylet cannot be eliminated from the needle kit. Thus, without clear benefit, eliminating stylet use could reduce procedural complexity and likely reduce endoscopy and sedation time.

Our relatively low diagnostic yield on a per lymph node basis (approximately 26% for both techniques) deserves explanation. This observation is likely explained by a relatively low prevalence of malignant lymph nodes in our analysis, stemming from the inclusion of only the first two lymph nodes from a given patient into the study. The predominant population in this study consisted of patients with known or suspected primary lung cancer undergoing mediastinal and hilar lymph node staging. In these patients, nodes routinely sampled first are the most distant from the lesion of concern (starting with the N3 node), which have the least likelihood of being positive, resulting in a lower prevalence of “diagnostic” samples. In line with this, our study’s lymph node size on average was smaller than that in EBUS trials with a high prevalence of malignancy (our median size was 1.0 cm compared with 1.9 cm in a trial with a high prevalence of malignancy).5 We chose to include only the first four passes of the first two nodes as a strategy to minimize the extra procedural costs and time an individual study participant would have to bear with enrollment. This decision (and diagnostic yield result) is comparable to other recent optimization trials of EBUS-TBNA.10 This population of low-prevalence and small-sized nodes may actually have increased our ability to detect any performance differences associated with stylet use. If only a small amount of tumor (or granuloma) was available for capture, the effects of a plugged or occluded needle lumen may have been magnified by this design. Thus, it may be encouraging that we found no benefit to stylet use under these potentially challenging conditions.

Strengths of this study are its prospective nature, the randomization of technique order, blinding of the cytology and pathology staff, and the use of each lymph node as an internal control, allowing for direct comparison between techniques. We included an unselected population of patients referred for EBUS at our institution, with a wide range of age and pathologic conditions, increasing the generalizability of our findings. Blinding and adherence to the randomization protocol were complete, and we had minimal loss of samples or recruitment issues. Although the clinical significance of metal particle deposition into the biopsy site from stylet/needle friction is of unclear significance, this potential problem is avoided in our stylet-free protocol.

There are limitations to our current analysis. Because we limited our analysis of each node to two passes with each technique, we were unable to evaluate the impact of stylet use on generating sufficient tissue for molecular diagnostic testing (this typically requires a minimum of four passes in total to gather sufficient material). However, blinded grading of the qualitative amount of malignant tissue present on individual passes showed no significant differences with stylet use, suggesting that molecular testing efficacy may be similar between techniques. As our study was performed at a single center by high-volume operators, results may be less generalizable to alternative settings.

Another potential limitation is our inability to precisely quantify procedural time saved by omitting stylet use. Our trial design with multiple redundant biopsies at each node prolonged each procedure, precluding careful time analysis. Future research could also evaluate if a stylet-free EBUS protocol is learned and mastered more easily than the more complicated procedure. Finally, although our pathologist and cytotechnicians were blinded to the technique used to obtain samples, the operators were not blinded, which may have led to subconscious bias, despite the operator’s best intentions to perform the procedure in a consistent manner.

In conclusion, EBUS-TBNA performed without a stylet had similar adequacy and diagnostic yield as traditional EBUS-TBNA. The histologic quality of samples was not enhanced with stylet use. Eliminating stylet use during EBUS-TBNA will reduce procedural complexity and may save procedural time.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: L. Y. is the guarantor of this paper and takes responsibility for the content of the manuscript including the data and analysis. E. S. and L. Y. contributed to the design, planning, initiation, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. R. S. and C. M. contributed to data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing and editing of the manuscript. P. I., S. A., H. L., D. F. K., K. O. B., B. F., and R. O. A. all contributed to data collection, data analysis, and editing of the manuscript. All authors had access to the data and final manuscript for approval prior to submission.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: None declared.

Other contributions: The authors would like to acknowledge the cytotechnology staff involved in this study in the Department of Cytopathology at The Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Footnotes

Drs Scholten and Semaan are co-first authors and contributed equally to this work.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: The authors have reported to CHEST that no funding was received for this study.

References

- 1.Varela-Lema L., Fernández-Villar A., Ruano-Ravina A. Effectiveness and safety of endobronchial ultrasound-transbronchial needle aspiration: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1156–1164. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00097908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yasufuku K., Nakajima T., Fujiwara T., Yoshino I., Keshavjee S. Utility of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration in the diagnosis of mediastinal masses of unknown etiology. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91(3):831–836. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yasufuku K., Nakajima T., Waddell T., Keshavjee S., Yoshino I. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration for differentiating N0 versus N1 lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(5):1756–1760. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trisolini R., Cancellieri A., Tinelli C., et al. Randomized trial of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration with and without rapid on-site evaluation for lung cancer genotyping. Chest. 2015;148(6):1430–1437. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yarmus L., Akulian J., Gilbert C., et al. Optimizing endobronchial ultrasound for molecular analysis. how many passes are needed? Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(6):636–643. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201305-130OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakajima T., Yasufuku K., Takahashi R., et al. Comparison of 21-gauge and 22-gauge aspiration needle during endobronchial ultrasound guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Respirology. 2011;16(1):90–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oki M. Randomized study of 21-gauge versus 22-gauge endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration needles for sampling histology specimens. J Bronchol Interv Pulmonol. 2011;18(4):306–310. doi: 10.1097/LBR.0b013e318233016c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casal R.F., Lazarus D.R., Kuhl K., et al. Randomized trial of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration under general anesthesia versus moderate sedation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(7):796–803. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1615OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yarmus L.B., Akulian J.A., Gilbert C., et al. Comparison of moderate versus deep sedation for endobronchial ultrasound transbronchial needle aspiration. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(2):121–126. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201209-074OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casal R., Staerkel G., Ost D. Randomized clinical trial of endobronchial ultrasound needle biopsy with and without aspiration. Chest. 2012;142(3):568–573. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wani S., Early D., Kunkel J., et al. Diagnostic yield of malignancy during EUS-guided FNA of solid lesions with and without a stylet: a prospective, single blind, randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76(2):328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abe Y., Kawakami H., Oba K., et al. Effect of a stylet on a histological specimen in EUS-guided fine-needle tissue acquisition by using 22-gauge needles: a multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82(5):837–844. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.03.1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macario A. What does one minute of operating room time cost? J Clin Anesth. 2010;22(4):233–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gounant V., Ninane V., Janson X., et al. Release of metal particles from needles used for transbronchial needle aspiration. Chest. 2011;139(1):138–143. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]