Abstract

Background

Lung cancer is a leading cause of death and hospitalization for patients with COPD. A detailed understanding of which clinical features of COPD increase risk is needed.

Methods

We performed a nested case-control study of Genetic Epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) Study subjects with and without lung cancer, age 45 to 80 years, who smoked at least 10-pack years to identify clinical and imaging features of smokers, with and without COPD, that are associated with an increased risk of lung cancer. The baseline evaluation included spirometry, high-resolution chest CT scanning, and respiratory questionnaires. New lung cancer diagnoses were identified over 8 years of longitudinal follow-up. Cases of lung cancer were matched 1:4 with control subjects for age, race, sex, and smoking history. Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to determine features predictive of lung cancer.

Results

Features associated with a future risk of lung cancer included decreased FEV1/FVC (OR, 1.28 per 10% decrease [95% CI, 1.12-1.46]), visual severity of emphysema (OR, 2.31, none-trace vs mild-advanced [95% CI, 1.41-3.86]), and respiratory exacerbations prior to study entry (OR, 1.39 per increased events [0, 1, and ≥ 2] [95% CI, 1.04-1.85]). Respiratory exacerbations were also associated with small-cell lung cancer histology (OR, 3.57 [95% CI, 1.47-10]).

Conclusions

The degree of COPD severity, including airflow obstruction, visual emphysema, and respiratory exacerbations, was independently predictive of lung cancer. These risk factors should be further studied as inclusion and exclusion criteria for the survival benefit of lung cancer screening. Studies are needed to determine if reduction in respiratory exacerbations among smokers can reduce the risk of lung cancer.

Key Words: chest imaging, COPD, lung cancer

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; HU, Hounsfield units; LAA%, percent low attenuation area; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; SCLC, small cell lung cancer

Lung cancer is one of the leading causes of death and hospitalization for individuals with COPD.1 The causal relationship between COPD and lung cancer needs to be further studied to understand the pathogenesis of lung cancer in this setting. Recent analysis of airway obstruction and emphysema in lung cancer screening cohorts has added to our knowledge of COPD and lung cancer risk. It is clear that the degree of airway obstruction is a predictor of lung cancer. This theory is true when controlled for confounding risk factors associated with cigarette smoking (ie, current smoking status, duration, intensity, years since quitting). In a subgroup analysis of subjects within the National Lung Cancer Screening Trial (NLST) with spirometric data available at the time of enrollment, a 2.15-fold increase occurred in lung cancer incidence for those with airway obstruction.2 Several meta-analyses have also found a strong correlation between degree of airway obstruction and a diagnosis of lung cancer.3, 4

The association of emphysema and lung cancer has been less clear. Early studies of quantitative emphysema and lung cancer risk were confounded by small case numbers, low-dose CT scans, and the novel technology of quantitative emphysema analysis.5, 6 However, subsequent research using visually assessed emphysema has validated this biomarker as a risk for lung cancer. Studies of the Pittsburgh Lung Screening Study identified visual emphysema on CT imaging as predictive of lung cancer independent of the severity of airway obstruction,7 and the COPD-Lung Cancer Screening Score validated the visual presence of emphysema as an independent variable for risk of lung cancer.8, 9

The risk of lung cancer associated with other clinical aspects of COPD, such as acute respiratory exacerbations, has not been thoroughly investigated. Respiratory exacerbations are characterized by lung inflammation, which is believed to be central to the pathogenesis of lung cancer in this setting.10 To further study the relationship between COPD phenotypes such as airflow obstruction, emphysema, and frequent respiratory exacerbations, we followed up subjects from the Genetic Epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) Study, one of the largest studies to date of smokers with and without COPD.11 The study enrolled older, current and former smokers, most of whom were at high risk for developing lung cancer. With longitudinal follow-up up to 8 years, we were able to analyze features of COPD that predict lung cancer.

Patients and Methods

This protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each institution, and all participants provided written informed consent. The study population was recruited from participants in the COPDGene Study (http://www.copdgene.org/).11 A detailed description of methods can be found in e-Appendix 1.

Exacerbations and Imaging

At the time of enrollment, subjects were asked on self-administered questionnaires, “Have you had a flare-up of your chest trouble in the last 12 months?” Zero exacerbations were recorded if the subject answered no. If the answer was yes, the subjects were asked how many episodes required either additional antibiotic or steroid medication, consultation with a physician, or hospital admission. The total number of such episodes was the exacerbation frequency.

A high-resolution chest CT scan was performed at the time of study enrollment. Visual analysis for centrilobular and paraseptal emphysema was performed by two trained readers, with discordant readings adjudicated by a thoracic radiologist.12 Parenchymal emphysema was scored on a scale of 0 to 5: none, trace, mild, moderate, confluent, and advanced-destructive.13 Paraseptal emphysema was scored into three categories: none, mild, and substantial.

Lung cancer cases were identified through longitudinal follow-up and collection of death certificates. During follow-up, if a subject self-reported a new diagnosis of lung cancer, this report was verified by review of medical records. Control subjects were those subjects with no lung cancer reported throughout longitudinal follow-up, and, for those with a death certificate, no recorded lung cancer.

Statistical Analysis

Unless otherwise specified, analyses were conducted by using R version 3.3.2 (R Development Core Team). Case and control subjects were matched 1:4, for known lung cancer risk factors, including age (within 5 years), race, sex, smoking status (current/former), pack-years of smoking exposure (within 10 pack-years), and years since quitting (within 10 years). Logistic regression with age, sex, race, smoking status, smoking pack-years, years since quitting, and FEV1/FVC as covariates was used to determined which other variables collected at the time of enrollment were associated with a new lung cancer diagnosis during longitudinal follow-up. Those variables found to be significant were used to generate a single multivariate model for lung cancer diagnosis. A second model was created by using just the lung cancer cases to identify baseline variables associated with histopathologic type. Additional baseline variables considered included the following: quantitative emphysema, as a continuous variable using either percent low attenuation area (LAA%) less than –950 Hounsfield units (HU), log of LAA%, or 15th percentile of the lung density; emphysema as a dichotomized variable (normal vs abnormal [> 5% LAA]); emphysema as an ordinal variable (visual emphysema [scored as none or trace]); and those with visual emphysema (scored as mild to advanced). Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to determine time to lung cancer diagnosis. The G-rho family of tests was used to determine hazard ratios (HRs) for time remaining lung cancer free.14

Results

A total of 169 subjects were identified as being diagnosed with lung cancer during the longitudinal follow-up of the COPDGene Study, with an average follow-up of 5.7 years (±1.87 years) (e-Fig 1). These case subjects were matched (for age, race, sex, smoking status, average smoking pack-years, and years since quitting smoking) 1:4 with 671 control subjects with no reported lung cancer diagnosis; five subjects only had three matched control subjects. The characteristics of the case and control subjects at the time of study enrollment are reported in Table 1. Forty-nine percent of lung cancer cases were identified in women, and 21% of cases were in African-American subjects. Compared with the control group, subjects who were diagnosed with lung cancer had more severe airway obstruction on baseline spirometry, as measured by FEV1/FVC and percent predicted FEV1. They also had more severe emphysema on both quantitative and visual assessment. In addition, subjects with a subsequent lung cancer diagnosis had more acute respiratory exacerbations in the year prior to enrollment and a lower BMI.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Lung Cancer Case Subjects and Control Subjects

| Variable | Case Subjects (n = 169) | Control Subjects (n = 671) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age at enrollment (± SD), y | 65.5 (7.6) | 64.4 (7.6) | |

| Race (NHW/AA) | 77.5%/21.4% | 75.1%/24.9% | |

| Sex (male/female) | 50.9%/49.4% | 50.6%/49.4% | |

| Smoking status (current/former/never) | 40.7%/59.3%/0.6% | 40.8%/59.2%/0 | |

| Average pack-years | 56.1 (32.9) | 52.3 (30.5) | |

| Years since quitting | 12.1 (10) | 12.9 (9.7) | |

| Exacerbation frequency (per 12 mo) | 0.6 (1.1) | 0.3 (0.8) | .0003 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.6 (6.2) | 28.6 (5.7) | .04 |

| Spirometry | |||

| FEV1 ppd | 58.9 (25.8) | 74.8 (24) | < .0001 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.2) | < .0001 |

| No obstruction | 17.2% (29) | 36.5% (245) | < .0001 |

| PRISm | 7.7% (13) | 9.2% (62) | .64 |

| GOLD stage | |||

| 1 | 4.1% (7) | 11.5% (77) | .006 |

| 2 | 31.4% (53) | 23.2% (156) | .03 |

| 3 | 24.9% (42) | 15.5% (104) | .006 |

| 4 | 14.2% (24) | 3.8% (25) | < .0001 |

| Quantitative CT measurements | |||

| Emphysema (percent HU –950) | 11.7% (12.1%) | 7.2% (9.7%) | .0001 |

| Subjects with emphysema HU –950 > 5% | 54.6% (92) | 37.9% (254) | .001 |

| Emphysema: upper lobe/lower lobe ratio | 2 (3) | 1.9 (3.0) | .07 |

| Expiratory gas trapping (percent HU –856) | 36.2% (21.4%) | 25% (19.3%) | < .0001 |

| Pi10 | 3.7 (0.1) | 3.7 (0.1) | .001 |

| Visual emphysema: centrilobular | |||

| None/trace | 28 (16.6%) | 254 (37.9%) | < .0001 |

| Mild | 34 (20.1%) | 128 (19.1%) | .84 |

| Moderate | 52 (30.8%) | 95 (14.2%) | < .0001 |

| Confluent | 31 (18.3%) | 58 (8.7%) | .0005 |

| Advanced/destructive | 13 (7.7%) | 33 (4.9%) | .21 |

| No visual assessment | 11 (6.5%) | 103 (15.3%) | |

| Visual emphysema: paraseptal | |||

| None | 87 (51.5%) | 306 (45.7%) | .20 |

| Mild | 27 (16%) | 142 (21.2%) | .16 |

| Substantial | 44 (26%) | 120 (17.9%) | .02 |

| No visual assessment | 11 (6.5%) | 103 (15.3%) |

AA = African-American; GOLD = Global initiative for Chronic Lung Disease; HU = Hounsfield units; NHW = non-Hispanic white; Pi10 = 10-mm internal perimeter; ppd = percent predicted; PRISm = Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry.

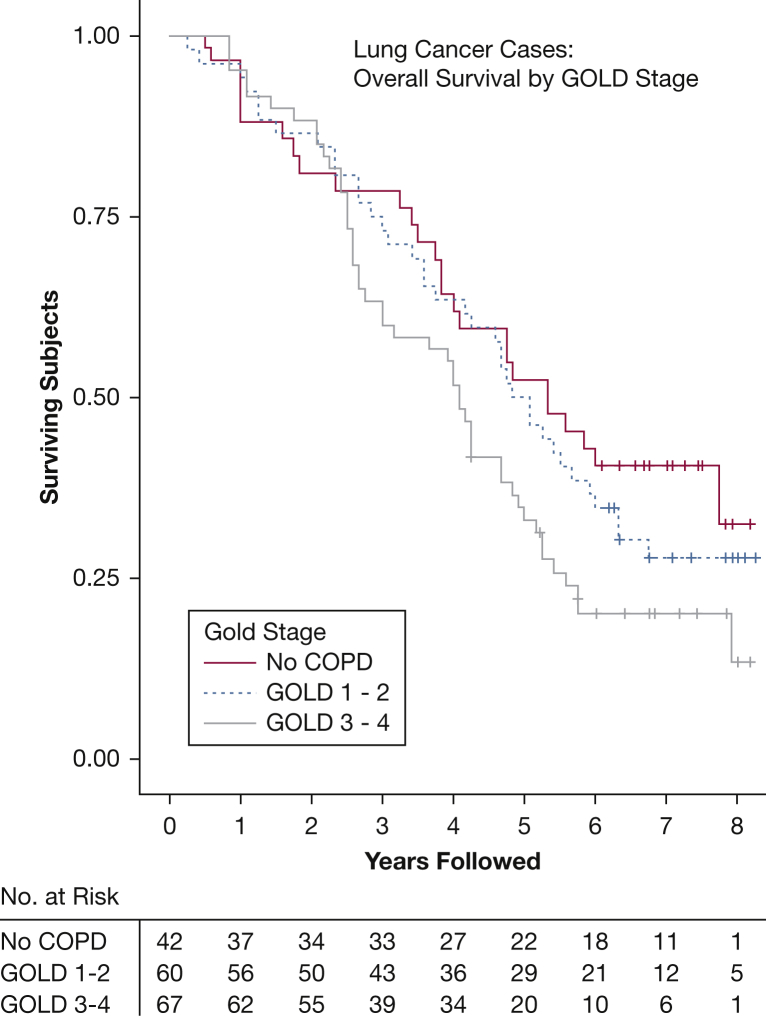

Of the 169 verified cases of lung cancer, 98 were confirmed non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and 18 were small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) (Table 2). Of the 79 NSCLC cases with staging information available, 42% were stage I at the time of diagnosis, and 18% had advanced (stage IV) disease; 62% of the NSCLC cases were adenocarcinoma. Analysis of mortality within the cases of lung cancer shows that those with an advanced Global Initiative for Chronic Lung Disease stage had inferior survival (Fig 1). Forty-six (79%) of the NSCLC cases and 10 (71%) of the SCLC cases with death certificates available for review had lung cancer listed as a cause of death.

Table 2.

Stage and Histology of Lung Cancer Cases

| Variable | NSCLC (n = 98) | SCLC (n = 18) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNM stage | IA | 35 (36%) | 2 (11%) |

| IB | 6 (6%) | 0 | |

| IIA | 7 (7%) | 0 | |

| IIB | 2 (2%) | 0 | |

| IIIA | 7 (7%) | 1 (6%) | |

| IIIB | 4 (4%) | 1 (6%) | |

| IV | 18 (18%) | 5 (28%) | |

| Unknown | 19 (20%) | 9 (50%) | |

| Histologic subtype (NSCLC) | Adenocarcinoma | 61 (62%) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 17 (17%) | ||

| Large-cell carcinoma | 1 (1%) | ||

| Large-cell neuroendocrine | 2 (2%) | ||

| Sarcomatoid | 1 (1%) | ||

| Undifferentiated | 1 (1%) | ||

| Unknown | 15 (15%) | ||

| Driver mutations (adenocarcinoma) | Cases documented | 14 | |

| KRAS mutation | 4 | ||

| EGFR mutation | 1 | ||

| ROS-1 translocation | 1 | ||

| GOLD stage | No obstruction | 8 (8.2%) | 2 (11.1%) |

| PRISm | 18 (18.5%) | 4 (22.2%) | |

| 1 | 5 (5.1%) | 1 (5.5%) | |

| 2 | 30 (30.9%) | 5 (27.7%) | |

| 3 | 24 (24.7%) | 3 (16.6%) | |

| 4 | 12 (12.3%) | 3 (16.6%) | |

| Subjects with death certificates | 58 (59% of NSCLC cases) | 14 (77% of SCLC cases) | |

| Lung cancer as COD | 46 (79% of death certificates) | 10 (71% of death certificates) | |

COD = cause of death; EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor; KRAS = Kirsten rat sarcoma virus; NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer; ROS-1 = c-ros oncogene 1, receptor tyrosine kinase; SCLC = small-cell lung cancer. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

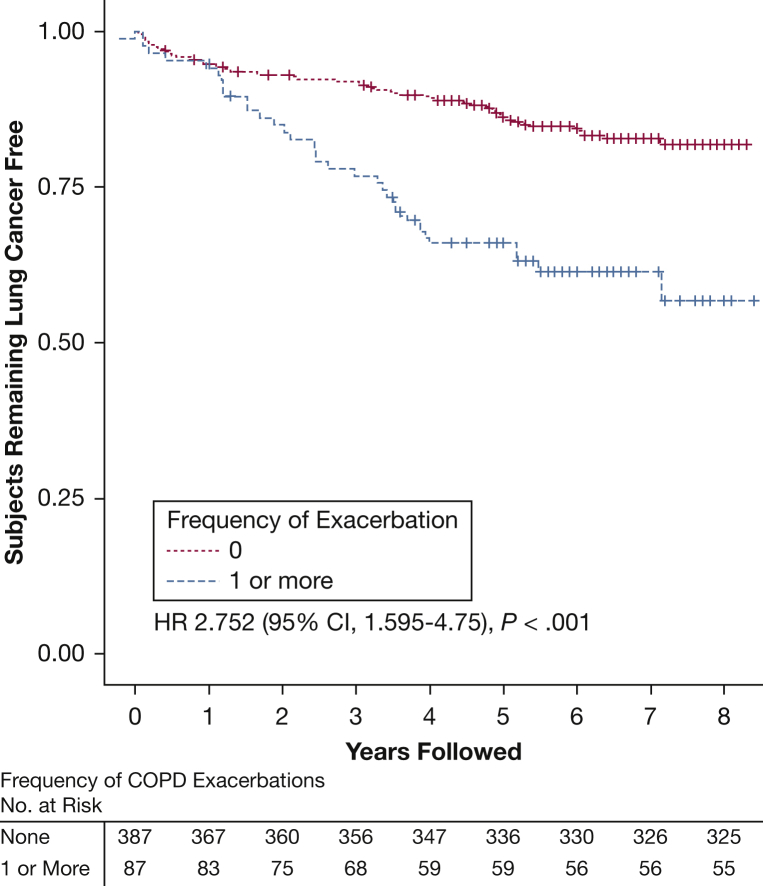

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve for lung cancer diagnosis, comparing subjects with no acute respiratory exacerbations reported in the 12 months prior to study enrollment (n = 387) vs those with one or more reported exacerbations (n = 87). Subjects were followed up for 8 years; those who died without lung cancer or were lost to follow-up were censored as marked. HRs are based on an unadjusted analysis of time to lung cancer diagnosis. This analysis was limited to cases with an annotated lung cancer diagnosis date and the matched control subjects. HR = hazard ratio.

Factors Associated With Lung Cancer

When matched for age, race, sex, smoking status, pack-years, and time since quitting tobacco, univariate predictors of a lung cancer diagnosis included respiratory exacerbations in the 12 months prior to enrollment, use of inhaled corticosteroid or tiotropium or combination of corticosteroid with tiotropium, decreased percent predicted FEV1, the presence of quantitative and visual emphysema, the presence of quantitative gas trapping, and an increase in airway wall thickness (10-mm internal perimeter) (Table 3). The highest predictors for a lung cancer diagnosis were the presence of visual emphysema (OR, 1.21 [95% CI, 1.14-1.28]; P < .001), an increase in 10-mm internal perimeter (OR, 1.45 [95% CI, 1.16-1.81]; P < .001), and the use of inhaled corticosteroids as single therapy (OR, 1.29 [95% CI, 1.17-1.41]; P < .001). Similar results were found when the case and matched control subjects were limited to subjects with COPD (FEV1/FVC < 0.7) (e-Tables 1 and 2).

Table 3.

Univariate Associations With the Diagnosis of Lung Cancer

| Variable | OR (SD) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Exacerbation frequency 12 mo prior to enrollment – (0-6) | 1.07 (1.03-1.10) | < .001 |

| Inhaled corticosteroid use | 1.29 (1.17-1.41) | < .001 |

| Inhaled corticosteroid with LABA | 1.11 (1.04-1.18) | .001 |

| Any inhaled corticosteroid | 1.17 (1.05-1.24) | < .001 |

| Tiotropium use | 1.17 (1.10-1.24) | < .001 |

| BMI | 0.99 (0.99-0.99) | .03 |

| Spirometry | ||

| FEV1 ppd per 10% decrease | 1.04 (1.03-1.05) | < .001 |

| FEV1/FVC per 10% decrease | 1.07 (1.05-1.08) | < .001 |

| Bronchodilator response | 1.05 (0.98-1.12) | .10 |

| Quantitative CT measurements | ||

| Emphysema: (percent HU –950) per 10% increase | 1.06 (1.03-1.09) | < .001 |

| Emphysema: (percent HU –950) > 5% | 1.11 (1.05-1.17) | < .001 |

| Emphysema: Perc15 | 0.98 (0.97-0.99) | < .001 |

| Emphysema: log (percent HU –950) | 1.10 (1.05-1.15) | < .001 |

| Emphysema: upper lobe/lower lobe ratio per 10% | 0.98 (0.89-1.08) | .80 |

| Gas trapping (percent HU –856) per 10% increase | 1.04 (1.02-1.05) | < .001 |

| Pi10 | 1.45 (1.16-1.81) | < .001 |

| Visual emphysema | ||

| Centrilobular: none-trace vs mild-advanced | 1.21 (1.14-1.286) | < .001 |

| Paraseptal: none vs mild | 0.94 (0.88-1.01) | .13 |

| Paraseptal: none vs substantial | 1.08 (1.01-1.16) | .01 |

Case and control subjects were matched for age, race, sex, smoking status, smoking pack-years, and years since quitting. HU = Hounsfield units; LABA = long-acting beta-agonist; Perc15 = 15th percentile of lung density. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

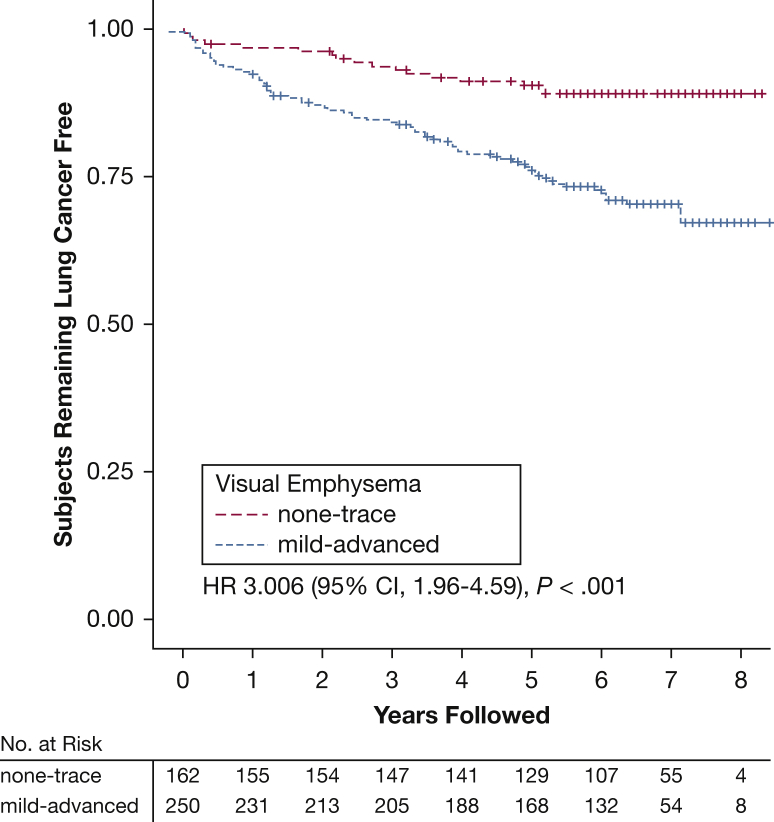

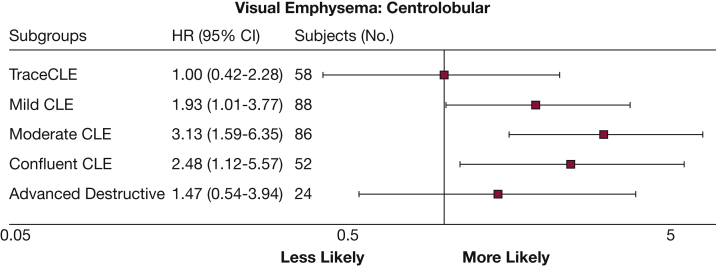

According to Kaplan-Meier analysis of lung cancer, case subjects with documented diagnosis dates (n = 94) and their matched control subjects who reported one or more respiratory exacerbations had an increased risk of lung cancer compared with subjects without a reported exacerbation (HR, 2.75 [95% CI, 1.59-4.75]; P < .001) (Fig 2). Analysis of case subjects with a diagnosis date and visual emphysema assessment (n = 82) and matched control subjects was also performed. Visual emphysema was also significantly associated with the risk of a lung cancer diagnosis (HR, 3.0 [95% CI, 1.98-4.59]; P < .001) (Fig 3), with the highest risk in those with moderate (HR, 3.13 [95% CI, 1.59-6.35]) to confluent (HR, 2.48 [95% CI, 1.12-5.57]) emphysema (Fig 4).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve comparing subjects with no to trace visual centrilobular emphysema (n = 162) vs those with mild to advanced visual emphysema (n = 250). Subjects were followed for 8 years for a lung cancer diagnosis. Subjects who died without lung cancer or were lost to follow-up were censored as marked. HRs are based on an unadjusted analysis of time to lung cancer diagnosis. This analysis was limited to those cases with annotated lung cancer diagnosis dates, complete visual emphysema assessment, and the matched control subjects. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of abbreviation.

Figure 3.

Lung cancer associations with degree of visual CLE. HRs (squares) and 95% CIs (whiskers) for the presence of each degree of visual emphysema on CT scan and study entry. GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Lung Disease. See Figure 1 and 2 legends for expansion of other abbreviation.

Figure 4.

Overall survival for lung cancer cases (N = 169) according to GOLD stage. Kaplan-Meier curve of subjects with a known lung cancer diagnosis confirmed by review of death certificates or medical records. See Figure 3 legend for expansion of abbreviation.

Factors Associated in a Multivariate Model

Multivariate analysis with logistic regression was performed on each variable with the earlier described covariates (e-Table 3). Factors that were independently associated with lung cancer during follow-up were used to generate a logistic regression model (Table 4). Model 1 included FEV1/FVC as a measure of airflow obstruction, and model 2 included percent predicted FEV1. The following factors were independently associated with lung cancer: airflow obstruction as measured by FEV1/FVC (OR, 1.28 per 10% decrease [95% CI, 1.12-1.46]; P < .001), history of acute respiratory exacerbations, per event increase(0, 1, and ≥ 2) (OR, 1.39 [95% CI, 1.04-1.85]; P = .02), and the presence of visual emphysema (OR, 2.31 [95% CI, 1.41-3.76]; P < .001). The results were similar when percent predicted FEV1 was used as the measure of airflow obstruction.

Table 4.

Factors Associated With a Lung Cancer Diagnosis in the Multivariable Model

| Factor | Lung Cancer Diagnosis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||

| OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| FEV1/FVC per 10% decrease | 1.28 (1.12-1.46) | < .001 | – | |

| FEV1 ppd per 5% decrease | … | 1.07 (1.03-1.12) | < .001 | |

| Exacerbations in year prior to enrollment per event increase (0, 1, and ≥ 2) | 1.39 (1.04-1.85) | .02 | 1.37 (1.02-1.82) | .03 |

| Visual emphysema: none-trace vs mild-advanced | 2.31 (1.41-3.76) | < .001 | 2.64 (1.66-4.30) | < .001 |

Case and control subjects were matched for age, race, sex, smoking status, smoking pack-years, and years since quitting. See Table 1 legend for expansion of abbreviation.

This analysis was also performed on case subjects and matched control subjects with COPD (FEV1/FVC < 0.7) (e-Table 4). In those with COPD, the severity of visual emphysema (OR, 5.02 [95% CI, 2.30-13.21) and the severity of obstruction as measured by FEV1 percent predicted (OR, 1.11 [95% CI, 1.05-1.17]) were independent predictors of lung cancer. Within this group, frequent exacerbations of COPD trended toward increased risk, although the number of subjects is small. Frequent exacerbations of COPD were associated with an increased likelihood of SCLC relative to NSCLC (OR, 4.0 [95% CI, 1.58-10.75]; P = .004), whereas NSCLC was increased in those with visual emphysema (OR, 0.18 [95% CI, 0.03-0.90]; P = .04) and male subjects (OR, 0.19 [95% CI, 0.03-0.75]; P = .02) (e-Table 5 and Table 5).

Table 5.

Factors Associated With Histologic Type in the Multivariable Model

| Factor | NSCLC as Reference Compared With SCLC (n = 116) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||

| OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| FEV1/FVC per 10% decrease | 1.44 (0.94-2.32) | .09 | ||

| FEV1 ppd per 5% decrease | 1.03 (0.88-1.20) | .74 | ||

| Exacerbations in year prior to enrollment per event increase (0, 1, and ≥ 2) | 3.57 (1.47-10) | .007 | 3.84 (1.58-11.11) | .005 |

| Visual emphysema: none-trace vs mild-advanced | 0.09 (0.01-0.54) | .01 | 0.18 (0.03-0.90) | .04 |

| Smoking pack-years, per 15- year increase | 0.92 (0.57-1.16) | .34 | 0.88 (0.61-1.19) | .44 |

| Smoking status, current smoking as reference | 3.03 (0.77-14.28) | .12 | 2.5 (0.66-11.11) | .18 |

| Sex, male as reference | 0.19 (0.03-0.8) | .03 | 0.19 (0.03-0.75) | .02 |

| Age, per 5-year increase | 0.59 (0.34-0.96) | .03 | 0.65 (0.39-1.05) | .08 |

Although qualitative assessment of emphysema was associated with lung cancer risk in multivariate modeling, quantitative measurements, including emphysema, gas trapping, and airway wall thickness, were not. This outcome was also true of inhaled respiratory medications, including corticosteroids and tiotropium.

Discussion

The COPDGene Study, one of the largest spirometry and CT imaging-based analyses of current and former smokers, evaluates multiple sub-phenotypes of COPD such as airflow obstruction, emphysema, and acute respiratory exacerbations. In the present study, we found that the severity of airflow obstruction is an independent risk factor for lung cancer, both in the larger COPDGene cohort as well as in those with COPD. We also validate several publications that report the presence and degree of visual emphysema (another marker of smoking-induced lung injury) increase the risk of lung cancer independent of airflow obstruction.7, 9, 12, 15, 16 For the first time, this study identifies that frequency of acute respiratory exacerbations also increases the risk of lung cancer independent of airflow obstruction and extent of emphysema. Whether acute respiratory exacerbations contribute to the pathogenesis of lung cancer, or are only a marker of the underlying smoking-induced injury and inflammation, is unknown. We also found that a history of acute respiratory exacerbations increased the risk of SCLC histology.

Chronic inflammation is believed to be central to the pathogenesis of lung cancer in the setting of COPD.10 The presence of chronic inflammation is associated with respiratory exacerbations, and the risks of both lung cancer and COPD exacerbations diminish with increased duration of smoking cessation.17, 18 Those with frequent exacerbations are believed to represent a unique sub-phenotype of patients with COPD. For instance, we have previously shown that prior exacerbations of COPD are predictive of future exacerbations.19 The existence of a COPD exacerbator phenotype is supported by the Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) study, which identified a subgroup of patients with COPD predisposed to frequent acute exacerbations of COPD. In a study with short longitudinal follow-up, it may be possible that subjects with a history of frequent respiratory exacerbations have a higher incidence of lung cancer diagnosis due to incidental findings on chest imaging performed in the setting of a medical evaluation of respiratory symptoms. However, the long interval of follow-up and a high rate of lung cancer as cause of death among the cases argue against overdiagnosis due to increased imaging. Also, subjects with frequent acute exacerbations of COPD were more like to have a diagnosis of SCLC, the incidence of which has not been altered by routine imaging in the setting of CT screening.20 Our analysis was performed on acute respiratory exacerbations reported for the 12-month period prior to COPDGene study enrollment. We did not analyze exacerbations during the COPDGene longitudinal follow-up period, as the association would be confounded by acute respiratory exacerbations caused by lung cancer and its treatment.

In the present study, the risk of lung cancer increased with severity of visual emphysema, although analysis of the most severe cases (advanced-destructive emphysema) was limited by small subject numbers. As seen in other studies, quantitative emphysema was not associated with a diagnosis of lung cancer. There is known discordance between visual and quantitative detection of emphysema; this discordance occurs because quantitative evaluation using LAA-950HU or other methods provides a relatively crude global index of lung density that can be affected by image noise, and may not detect mild or localized emphysema.21 Because visual emphysema grading is less sensitive to image noise, it more precisely discriminates between subjects with and without emphysema. The results of this study are congruent with several previous articles which have shown that although visual evidence of emphysema is associated with lung cancer, most have found that there is no association with quantitative emphysema.5, 7, 16, 22, 23, 24

Because the incidence of lung cancer was not a primary outcome of the COPDGene Study, this study is limited by missing clinical data and subject recall related to previous exacerbations. Although all control subjects were screened to ensure that no lung cancer was reported, false-negative findings may be present. Another limitation is that 24% of the COPDGene subjects had < 5 years of follow-up, and 10% of subjects had no follow-up. Thus, we expect that some lung cancer diagnoses are unreported, and survival outcomes of these subjects are unknown. The majority of cases in this study were identified by review of death certificates (e-Fig 2), which could explain the high mortality rate (Fig 1).

Conclusions

Following the publication of the results of the NLST showing an improvement in overall mortality from CT lung cancer screening, multiple organizations recommended lung cancer screening.20 These guidelines were predominantly based on the NLST entry criteria: age 55 to 74 years with ≥ 30 pack-years of smoking history and either currently smoking or quit within the previous 15 years.25, 26, 27, 28 The data are limited to inform screening guidelines in those with COPD,29 including those with advanced disease who should be excluded due to lack of benefit and those with high risk features who should be included. As our understanding of COPD phenotypes and lung cancer risk continues to expand, the lung cancer screening guidelines should also evolve. Our study suggests that in addition to airflow obstruction, visual emphysema and a history of acute respiratory exacerbations should also be considered in future lung cancer screening studies.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: L. L. C. confirms that the study objectives and procedures are honestly disclosed; moreover, she has reviewed study execution data and confirms that procedures were followed to an extent that convinces all authors that the results are valid and generalizable to a population similar to that enrolled in this study. L. L. C. and R. P. B. were responsible for study concept and design; L. L. C., R. P. B, D. A. L., M. G. F., E. F., C. P. H, F. C. S., and V. K. were responsible for acquisition of data; L. L. C., S. J., and R. P. B. analyzed and interpreted the data; L. L. C., S. J., and R. P. B. drafted the manuscript; D. A. L., M. G. F., E. F., C. P. H., F. C. S., D. O. W., J. S., P. M., V. K., C. M. K., and R. P. B. were responsible for critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; S. J. and R. P. B. performed the statistical analysis; and L. L. C., S. J., and R. P. B. had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: V. K. reports grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and personal fees from Medscape, CSA Medical, AstraZeneca, Concert Pharmaceuticals, the American Board of Internal Medicine, and Gala Therapeutics outside the submitted work. R. P. B. and L. L. C. report grants from Boehringer Ingelheim. J. C. S. reports grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study; and personal fees from VIDA Diagnostics outside the submitted work. M. G. F. reports grants from the COPDGene Study (R01HL089856); and grants from AstraZeneca, Pearl Therapeutics, and GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work. C. P. H. reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Concert Pharmaceuticals, and Mylan; and grants from Boehringer Ingelheim and the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. D. A. L. reports grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and personal fees from Parexel, Veracyte, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Genentech/Roche outside the submitted work. None declared (P. M., E. L. F., F. C. S., S. J., D. O. W., M. K.).

Role of sponsors: This study was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (BIPI). BIPI had no role in the design, analysis, or interpretation of the results in this study; BIPI was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as it relates to BIPI substances, as well as intellectual property considerations.

COPDGene Investigators—Core Units. Administrative Center: James D. Crapo, MD (Principal Investigator); Edwin K. Silverman, MD, PhD (Principal Investigator); Barry J. Make, MD; Elizabeth A. Regan, MD, PhD. Genetic Analysis Center: Terri Beaty, PhD; Ferdouse Begum, PhD; Robert Busch, MD; Peter J. Castaldi, MD, MSc; Michael Cho, MD; Dawn L. DeMeo, MD, MPH; Adel R. Boueiz, MD; Marilyn G. Foreman, MD, MS; Eitan Halper-Stromberg, PhD; Nadia N. Hansel, MD, MPH; Megan E. Hardin, MD; Lystra P. Hayden, MD, MMSc; Craig P. Hersh, MD, MPH; Jacqueline Hetmanski, MS, MPH; Brian D. Hobbs, MD; John E. Hokanson, MPH, PhD; Nan Laird, PhD; Christoph Lange, PhD; Sharon M. Lutz, PhD; Merry-Lynn McDonald, PhD; Margaret M. Parker, PhD; Dandi Qiao, PhD; Elizabeth A. Regan, MD, PhD; Stephanie Santorico, PhD; Edwin K. Silverman, MD, PhD; Emily S. Wan, MD; Sungho Won. Imaging Center: Mustafa Al Qaisi, MD; Harvey O. Coxson, PhD; Teresa Gray; MeiLan K. Han, MD, MS; Eric A. Hoffman, PhD; Stephen Humphries, PhD; Francine L. Jacobson, MD, MPH; Philip F. Judy, PhD; Ella A. Kazerooni, MD; Alex Kluiber, BA; David A. Lynch, MB; John D. Newell Jr, MD; Elizabeth A. Regan, MD, PhD; James C. Ross, PhD; Raul San Jose Estepar, PhD; Joyce Schroeder, MD; Jered Sieren BSc; Douglas Stinson BA; Berend C. Stoel, PhD; Juerg Tschirren, PhD; Edwin Van Beek, MD, PhD; Bram van Ginneken, PhD; Eva van Rikxoort, PhD; George Washko, MD; Carla G. Wilson, MS. PFT QA Center, Salt Lake City, UT: Robert Jensen, PhD. Data Coordinating Center and Biostatistics, National Jewish Health, Denver, CO: Douglas Everett, PhD; Jim Crooks, PhD; Camille Moore, PhD; Matt Strand, PhD; Carla G. Wilson, MS. Epidemiology Core, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO: John E. Hokanson, MPH, PhD; John Hughes, PhD; Gregory Kinney, MPH, PhD; Sharon M. Lutz, PhD; Katherine Pratte, MSPH.

COPDGene Investigators—Clinical Centers: Ann Arbor, VA: Jeffrey L. Curtis, MD; Carlos H. Martinez, MD, MPH; Perry G. Pernicano, MD. Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX: Nicola Hanania, MD, MS; Philip Alapat, MD; Mustafa Atik, MD; Venkata Bandi, MD; Aladin Boriek, PhD; Kalpatha Guntupalli, MD; Elizabeth Guy, MD; Arun Nachiappan, MD; Amit Parulekar, MD. Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA: Dawn L. DeMeo, MD, MPH; Craig Hersh, MD, MPH; Francine L. Jacobson, MD, MPH; George Washko, MD. Columbia University, New York, NY: R. Graham Barr, MD, DrPH; John Austin, MD; Belinda D’Souza, MD; Gregory D.N. Pearson, MD; Anna Rozenshtein, MD, MPH, FACR; Byron Thomashow, MD. Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC: Neil MacIntyre Jr, MD; H. Page McAdams, MD; Lacey Washington, MD. HealthPartners Research Institute, Minneapolis, MN: Charlene McEvoy, MD, MPH; Joseph Tashjian, MD. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD: Robert Wise, MD; Robert Brown, MD; Nadia N. Hansel, MD, MPH; Karen Horton, MD; Allison Lambert, MD, MHS; Nirupama Putcha, MD, MHS. Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA: Richard Casaburi, PhD, MD; Alessandra Adami, PhD; Matthew Budoff, MD; Hans Fischer, MD; Janos Porszasz, MD, PhD; Harry Rossiter, PhD; William Stringer, MD. Michael E. DeBakey VAMC, Houston, TX: Amir Sharafkhaneh, MD, PhD; Charlie Lan, DO. Minneapolis, VA: Christine Wendt, MD; Brian Bell, MD. Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA: Marilyn G. Foreman, MD, MS; Eugene Berkowitz, MD, PhD; Gloria Westney, MD, MS. National Jewish Health, Denver, CO: Russell Bowler, MD, PhD; David A. Lynch, MB. Reliant Medical Group, Worcester, MA: Richard Rosiello, MD; David Pace, MD. Temple University, Philadelphia, PA: Gerard Criner, MD; David Ciccolella, MD; Francis Cordova, MD; Chandra Dass, MD; Gilbert D’Alonzo, DO; Parag Desai, MD; Michael Jacobs, PharmD; Steven Kelsen, MD, PhD; Victor Kim, MD; A. James Mamary, MD; Nathaniel Marchetti, DO; Aditi Satti, MD; Kartik Shenoy, MD; Robert M. Steiner, MD; Alex Swift, MD; Irene Swift, MD; Maria Elena Vega-Sanchez, MD. University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL: Mark Dransfield, MD; William Bailey, MD; Surya Bhatt, MD; Anand Iyer, MD; Hrudaya Nath, MD; J. Michael Wells, MD. University of California, San Diego, CA: Joe Ramsdell, MD; Paul Friedman, MD; Xavier Soler, MD, PhD; Andrew Yen, MD. University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA: Alejandro P. Comellas, MD; John Newell, Jr., MD; Brad Thompson, MD. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI: MeiLan K. Han, MD, MS; Ella Kazerooni, MD; Carlos H. Martinez, MD, MPH. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN: Joanne Billings, MD; Abbie Begnaud, MD; Tadashi Allen, MD. University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: Frank Sciurba, MD; Jessica Bon, MD; Divay Chandra, MD, MSc; Carl Fuhrman, MD; Joel Weissfeld, MD, MPH. University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX: Antonio Anzueto, MD; Sandra Adams, MD; Diego Maselli-Caceres, MD; and Mario E. Ruiz, MD.

Additional information: The e-Appendix, e-Figures, and e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This study was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The COPDGene Study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grants R01 HL089897 and R01 HL089856]. The COPDGene project is also supported by the COPD Foundation through contributions made to an Industry Advisory Board composed of AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Siemens, and Sunovion.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Anthonisen N.R., Connett J.E., Enright P.L., Manfreda J. Hospitalizations and mortality in the Lung Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(3):333–339. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2110093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young R.P., Duan F., Chiles C. Airflow limitation and histology shift in the National Lung Screening Trial. The NLST-ACRIN Cohort Substudy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(9):1060–1067. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0894OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fry J.S., Hamling J.S., Lee P.N. Systematic review with meta-analysis of the epidemiological evidence relating FEV1 decline to lung cancer risk. BMC Cancer. 2012;12(1):146. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasswa-Kintu S. Relationship between reduced forced expiratory volume in one second and the risk of lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2005;60(7):570–575. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.037135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maldonado F., Bartholmai B.J., Swensen S.J., Midthun D.E., Decker P.A., Jett J.R. Are airflow obstruction and radiographic evidence of emphysema risk factors for lung cancer? A nested case-control study using quantitative emphysema analysis. Chest. 2010;138(6):1295–1302. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kishi K., Gurney J.W., Schroeder D.R., Scanlon P.D., Swensen S.J., Jett J.R. The correlation of emphysema or airway obstruction with the risk of lung cancer: a matched case-controlled study. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(6):1093–1098. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00264202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson D.O., Weissfeld J.L., Balkan A. Association of radiographic emphysema and airflow obstruction with lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;178(7):738–744. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200803-435OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sánchez-Salcedo P., Wilson D.O., de-Torres J.P. Improving selection criteria for lung cancer screening. The potential role of emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(8):924–931. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201410-1848OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de-Torres J.P., Wilson D.O., Sánchez-Salcedo P. Lung cancer in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Development and validation of the COPD Lung Cancer Screening Score. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(3):285–291. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201407-1210OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adcock I.M., Caramori G., Barnes P.J. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer: new molecular insights. Respiration. 2011;81(4):265–284. doi: 10.1159/000324601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regan E.A., Hokanson J.E., Murphy J.R. Genetic Epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) Study Design. COPD. 2010;7(1):32–43. doi: 10.3109/15412550903499522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halper-Stromberg E., Cho M.H., Wilson C. Visual assessment of chest computed tomographic images is independently useful for genetic association analysis in studies of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(1):33–40. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201606-427OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynch D.A., Austin J.H., Hogg J.C. CT-definable subtypes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a statement of the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2015;277(1):192–205. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015141579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrington D.P., Fleming T.R. A class of rank test procedures for censored survival data. Biometrika. 1982;69(3):553–566. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y., Swensen S.J., Karabekmez L.G. Effect of emphysema on lung cancer risk in smokers: a computed tomography-based assessment. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4(1):43–50. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de-Torres J.P., Bastarrika G., Wisnivesky J.P. Assessing the relationship between lung cancer risk and emphysema detected on low-dose CT of the chest. Chest. 2007;132(6):1932–1938. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Au D.H., Bryson C.L., Chien J.W. The effects of smoking cessation on the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(4):457–463. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0907-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuberger J.S., Mahnken J.D., Mayo M.S., Field R.W. Risk factors for lung cancer in Iowa women: implications for prevention. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30(2):158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowler R.P., Kim V., Regan E. Prediction of acute respiratory disease in current and former smokers with and without COPD. Chest. 2014;146(4):941–950. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Aberle D.R., Adams A.M. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.COPDGene CT Workshop Group. Barr R.G., Berkowitz E.A. A combined pulmonary-radiology workshop for visual evaluation of COPD: study design, chest CT findings and concordance with quantitative evaluation. COPD. 2012;9(2):151–159. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2012.654923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson D.O., Leader J.K., Fuhrman C.R., Reilly J.J., Sciurba F.C., Weissfeld J.L. Quantitative computed tomography analysis, airflow obstruction, and lung cancer in the Pittsburgh Lung Screening Study. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(7):1200–1205. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318219aa93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gierada D.S., Guniganti P., Newman B.J. Quantitative CT assessment of emphysema and airways in relation to lung cancer risk. Radiology. 2011;261(3):950–959. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oelsner E.C., Carr J.J., Enright P.L. Per cent emphysema is associated with respiratory and lung cancer mortality in the general population: a cohort study. Thorax. 2016;71(7):624–632. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood D.E., Kazerooni E., Baum S.L. Lung cancer screening, version 1.2015: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(1):23–34. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0006. quiz 34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaklitsch M.T., Jacobson F.L., Austin J.H.M. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery guidelines for lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography scans for lung cancer survivors and other high-risk groups. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moyer V.A. Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):330–338. doi: 10.7326/M13-2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wender R., Fontham E.T., Barrera E., Jr. American Cancer Society lung cancer screening guidelines. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2013;63(2):107–117. doi: 10.3322/caac.21172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanner N.T., Dai L., Bade B.C., Gebregziabher M., Silvestri G.A. Assessing the generalizability of the National Lung Screening Trial: comparison of patients with stage 1 disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(5):602–608. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201705-0914OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.