Abstract

Diffusion in cellular membranes is regulated by processes that occur over a range of spatial and temporal scales. These processes include membrane fluidity, interprotein and interlipid interactions, interactions with membrane microdomains, interactions with the underlying cytoskeleton, and cellular processes that result in net membrane movement. The complex, non-Brownian diffusion that results from these processes has been difficult to characterize, and moreover, the impact of factors such as membrane recycling on membrane diffusion remains largely unexplored. We have used a careful statistical analysis of single-particle tracking data of the single-pass plasma membrane protein CD93 to show that the diffusion of this protein is well described by a continuous-time random walk in parallel with an aging process mediated by membrane corrals. The overall result is an evolution in the diffusion of CD93: proteins initially diffuse freely on the cell surface but over time become increasingly trapped within diffusion-limiting membrane corrals. Stable populations of freely diffusing and corralled CD93 are maintained by an endocytic/exocytic process in which corralled CD93 is selectively endocytosed, whereas freely diffusing CD93 is replenished by exocytosis of newly synthesized and recycled CD93. This trafficking not only maintained CD93 diffusivity but also maintained the heterogeneous distribution of CD93 in the plasma membrane. These results provide insight into the nature of the biological and biophysical processes that can lead to significantly non-Brownian diffusion of membrane proteins and demonstrate that ongoing membrane recycling is critical to maintaining steady-state diffusion and distribution of proteins in the plasma membrane.

Introduction

The plasma membrane is a complex organelle in which dynamic structural and organizational features enable processes such as receptor-mediated signaling, endocytosis and exocytosis, and intercellular interactions. Many of these processes rely on self-organizing molecular complexes whose assembly, composition, and lifetime are dictated by the diffusional behaviors of their constituent members. Membrane diffusion is a complex biophysical process that differs significantly from free Brownian diffusion (reviewed in (1, 2)). As a result, the apparent diffusional behavior of proteins in cellular membranes determined from experimental data depends on factors such as the sampling rate and the duration of the measurement. At high temporal resolution, some membrane proteins have been shown to undergo free Brownian motion over length scales of <200 nm (3), although this scale is molecule- and cell-dependent. Over longer times, their motion becomes non-Brownian, and molecules instead undergo hop-diffusion characterized by transient periods of trapping within confinement zones separated by “hops” from one confinement zone to another (3, 4, 5). This “wait-and-jump” behavior is reminiscent of continuous-time random walk (CTRW), a form of anomalous diffusion characterized by particles that move by a series of “jumps” separated by waiting periods of random duration (6, 7). Further deviations from Brownian diffusion may result from molecular crowding, interprotein interactions, and interactions of diffusing proteins with membrane microdomains (8, 9, 10). Despite the complex non-Brownian motion of individual molecules, techniques such as fluorescence recovery after photobleaching that analyze diffusion over second-to-minute timescales show Brownian-like diffusion, albeit with effective diffusion coefficients one to two orders of magnitude lower than those observed in model membranes that are free of confinement zones and have a low protein density (9).

This apparent change in diffusional behavior under different observational conditions is thought to be an emergent property reflecting the influence of multiple processes occurring over a range of time and length scales. Brownian diffusion of both proteins and lipids has been reported in simple model membranes (11, 12) and over short periods of time (nano- to milliseconds) in cellular membranes (3). Molecular modeling of protein-rich membranes suggest that Brownian-like diffusion of proteins should give way to anomalous diffusion at timescales longer than a few microseconds (13), whereas in cellular membranes the transition from Brownian to anomalous hop diffusion has been observed at timescales of a few tens of milliseconds and at spatial scales between 20 and 200 nm (14). The disagreement between the model and the observational studies may be due to cellular factors unaccounted for by current models or by the current spatial (10–20 nm) and temporal (hundreds of microseconds) limitations of single-molecule tracking systems. Hop diffusion results from interactions between diffusing molecules and barriers comprising membrane-proximal actin filament “fences” attached to “pickets” of actin-bound transmembrane proteins that form a percolation barrier in the membrane (15, 16); similar barriers comprising the cytoskeletal proteins spectrin and septin have also been reported (17, 18). These picket-fence structures create confinement zones termed “corrals,” ranging from 40 to ∼400 nm in size, that restrict the diffusion of transmembrane proteins, lipids, and lipid-anchored proteins on both the cytosolic and extracellular leaflet of the plasma membrane. Diffusing proteins and lipids are transiently trapped within corrals and then “hop” between corrals either by successfully diffusing through the percolation barrier or by diffusing through gaps created in the “picket fence” by actin turnover (4, 5). Diffusion of proteins is further modified by interactions with membrane microdomains, such as lipid rafts, and with other membrane, cytosolic, and extracellular proteins (10, 15, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24). These interactions take place on timescales ranging from submilliseconds (protein-protein and protein-lipid interactions) to tens of milliseconds (rafts), seconds (actin corrals), hours, or even days (focal contacts). A final layer of complexity is added by the cellular processes of exocytosis and endocytosis, which respectively deliver and remove material from the plasma membrane. These processes also occur over a wide range of timescales, from a few tens of milliseconds during ultrarapid membrane recycling in neurons to several minutes for recycling endosome pathways (25, 26).

A consequence of this complex environment is that measurements of diffusional behavior are highly dependent on the temporal resolution and duration of the experiments used to observe diffusion. This has made it difficult to develop a mathematical framework that realistically describes diffusion within the plasma membrane of eukaryotic cells (2, 27). Moreover, diffusion is conventionally quantified using time-averaged mean-square displacement (TAMSD), which measures changes in molecular position as a function of the lag time between observations without regard to when in real time those observations were made. Although this approach is statistically robust and sensitive to processes that operate on different timescales, it obscures processes that evolve over real time. Of greater concern is that some methods used to quantify diffusion in biological systems assume that cellular diffusion is scale invariant (i.e., that diffusion measured over one temporal or spatial range will be identical to diffusion measured over different temporal or spatial ranges), is ergodic (i.e., that every region of space is visited with equal probability), or occurs in a homogeneous environment—assumptions that recent measurements of cellular diffusion clearly demonstrate are untrue (28, 29, 30).

Several models have been developed to describe non-Brownian diffusion. These include fractional Brownian motion (FBM), CTRWs, and motion in a fractal environment, all of which have been applied to describe the anomalous diffusion of proteins in a biological context (2, 29, 31). Brownian motion, FBM, and diffusion in fractals are scale invariant and ergodic. In Brownian motion, the TAMSD as a function of lag time τ is equivalent to the ensemble-averaged mean-square displacement (MSD) (EA-MSD) as a function of measurement (real) time t. For non-Brownian systems, this equivalence may not hold. Different models predict different relationships between these quantities (reviewed in (31)). For example, simple Brownian diffusion is accurately modeled by a random walk, in which a particle moves a fixed distance in a random direction at each time step. In a CTRW, in contrast, the particle is “trapped’’ for a random waiting time before making each jump. The former process is ergodic, whereas if the waiting times are power-law distributed, the latter is not. In principle, the two models can be distinguished from each other by the lag-time and measurement-time dependence of the TAMSDs and EA-MSDs.

In this study, we carry out a careful statistical analysis of long-duration single-particle tracking (SPT) data to characterize the anomalous diffusion of the type I transmembrane protein CD93, a group XIV C-type lectin linked to the plasma membrane by a single transmembrane domain and bearing a short intracellular domain. Although CD93’s ligands and signaling pathways remain to be elucidated, it has established roles in efferocytosis, angiogenesis, and cell adhesion (32, 33, 34). Our analysis demonstrates that the diffusion of CD93 is well described by a CTRW model, evolves over real time, and is sustained by endocytosis and exocytosis.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The 12CA5 hybridoma was a gift from Dr. Joe Mymryk (University of Western Ontario, London, Canada). Lympholyte-poly, Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, and Cy3-conjugated rabbit-anti-mouse Fab fragments were purchased from Cedarlane Labs (Burlington, Canada). All tissue culture media, trypsin-EDTA 100X antibiotic-antimycotic solution, and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Wisent (St. Bruno, Canada). 18 mm, #1.5 thickness round coverslips were purchased from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Hatfield, PA). Anti-human CD93 was purchased from eBioscience (Toronto, Canada). Chamlide magnetic Leiden chambers were purchased from Quorum Technologies (Puslinch, Canada). GenJet Plus in vitro DNA transfection reagent was purchased from Frogga Bio (Toronto, Canada). Leica DMI6000B microscope, objectives, and all accessories were purchased from Leica Microsystems (Concord, Canada). The computer workstation was purchased from Stronghold Services (London, Canada). MATLAB equipped with parallel processing, statistics, image processing, and optimization toolboxes was purchased from The MathWorks (Natick, MA). Prism statistical software was purchased from Graphpad (La Jolla, CA). Fiji is Just ImageJ (FIJI) was downloaded from https://fiji.sc/. All other materials were purchased from Thermo-Fisher (Toronto, Canada). The CD93 constructs were described previously (28).

CHO cell culture and transfection

CHO cells were cultured in F-12 media + 10% FBS in a 37°C/5% CO2 incubator. Upon reaching >80% confluency, CHO cells were split 1:10 by washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), incubating for 2 min at 37°C with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA and then suspension in a 4× volume of media + 10% FBS. For microscopy, ∼2.5 × 105 cells were plated onto sterile 18 mm round coverslips placed into the wells of a 12-well tissue culture plate. 18–24 h later, the cells were transfected by adding dropwise to the cells a mixture composed of 1 μg/well of either human CD93-GFP or influenza hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged human CD93 (HA-CD93) and 2.25 μL of GenJet reagent suspended in 76 μL of serum-free Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium. Cells were imaged between 18 and 32 h after transfection.

12CA5 hybridoma culture, Fab generation, and fluorescent labeling

12CA5 hybridoma cells were maintained at 37°C/5% CO2 in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium + 10% FBS and split 1:5 once maximal cell density was reached. For antibody collection, a 60 mL culture at maximal density was pelleted by centrifugation (300 × g, 5 min), resuspended in 60 mL of serum-free hybridoma media, and cultured for 5 days. Cells and media were transferred to centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 3000 × g, 20 min, 4°C to remove cells and particulates. Antibodies were then concentrated, and the medium was replaced with 10 mM Tris + 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.4) using a 60 kDa cutoff centrifuge concentrator. Concentrated antibody was diluted to 5 mg/mL total protein, and Fab fragments were generated by adding 10 mM EDTA and 20 mM cysteine-HCl to 1 mL of antibody solution, followed by addition of 500 μL of immobilized papain and incubation at 37°C for 18 h. Papain was then removed by a 1000 × g, 15 min centrifugation. Fab fragments were then purified by separating the protein mixture using fast protein liquid chromatography equipped with a Sephacryl S100 column. Aliquots corresponding to the first (Fab fragment) peak were pooled and stored for later use at 4°C. Fab fragments were directly conjugated to Alexa 488 or Cy3 using protein conjugation kits.

SPT

SPT was performed using a Leica DMI6000B wide-field fluorescent microscope equipped with a 100×/1.40 NA objective, supplemental 1.6× in-line magnification, a Photometrics Evolve-512 delta electron-multiplying charge-coupled device camera mounted using a 0.7× C-mount, a Chroma Sedat Quad filter set, and a heated/CO2 perfused live-cell piezoelectric stage, as described previously (28). Briefly, coverslips were mounted in Leiden chambers, and the chambers were filled with 1 mL of 37°C imaging buffer (150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 100 μM EGTA, 2 mM CaCl2, 25 mM HEPES, and 1500 g/L NaHCO3). Samples were maintained at 37°C/5% CO2 on a heated/CO2 perfused microscope stage for the duration of the experiment. 30 s duration videos of the basolateral side of the cells were recorded at a frame rate of 10 frames/s, with 5–15 cells recorded per coverslip. The resulting videos were cropped to the area containing the cell and exported as tagged image file formatted image stacks. Initial analysis was performed using the MATLAB scripts of Jaqaman et al. (35) on a dual-Xeon E5-2630 chip workstation running OpenSUSI Linux and MATLAB 2014b. Custom-written MATLAB scripts were then used to remove any CD93 trajectories with a positional certainty worse than ±25 nm (SNR 2.2), and the remaining data sets containing >1000 trajectories were retained for further analysis, leading to rejection of ∼40% of trajectories. Our previous study of CD93 diffusion identified no differences in the diffusion coefficient of CD93 on the basolateral or apical cell surface, and vesicular CD93 was not detected using this method (28).

Immunolabeling of CD93

CD93 was immunolabled such that cross-linking was avoided at a labeling density that allowed resolution of individual point-spread functions, as per our previous studies (28, 36, 37). Briefly, CHO cells transfected with CD93-GFP were cooled to 10°C and blocked for 20 min in F12 media + 4% human serum and then incubated for 20 min with blocking solution containing 1:5000 antihuman CD93. Samples were washed for 3 × 5 min in PBS and blocking buffer containing 1:10,000 diluted Cy3-conjugated Fab secondary antibodies added for an additional 20 min. The samples were washed for an additional 3 × 5 min in F12 media + 10% FBS and kept at 10°C until imaged.

EA-MSDs and TAMSDs

The CD93 trajectories in each independent experiment were first classified as either freely diffusing or corralled using TAMSD and moment scaling spectrum (MSS) analysis, utilizing the software of Jaqaman et al. for these calculations (35). Data ensembles were then created by binning the CD93 tracks from all experiments based on the size of the confinement regions determined from this initial classification. Tracks from CD93 in confinement zones with diameters of 100 ± 50, 200 ± 50, 300 ± 50, 400 ± 50, and 500 ± 50 nm and from freely diffusing CD93 were placed into separate ensembles. The EA-MSD,

| (1) |

was calculated for each ensemble using a custom-written MATLAB script. Here, the ensemble average is denoted by the overbar. is the position of the nth CD93 molecule at experimental time t, measured relative to its position at t = 0, and is its magnitude. For each particle trajectory, the first frame in which the particle was detected (t′) was defined as t = 0.

A set of trajectories with a given total measurement time T was generated by selecting all trajectories within an ensemble having length T or greater and then truncating them at the chosen T (29). The squared displacement for a given lag time τ was calculated for each trajectory and then averaged over all starting times t′ to give the following TAMSD

| (2) |

where τ ≤ (T/3). The subscript k labels the trajectory, and the angle brackets denote the time average. This quantity was then averaged over all trajectories in the ensemble, yielding the ensemble-averaged and time-averaged MSD (EA-TAMSD) :

| (3) |

which is a function of both T and τ. Here, the sum is over the N′ truncated trajectories in the ensemble having length T.

The TAMSD can be reasonably well described by a power-law dependence on the lag time τ,

| (4) |

over a range of lag times. As described below, the distribution of the resulting power-law exponents ατ at a given value of T was fitted to a sum of two Gaussians using a maximal likelihood estimation method.

Mean maximal excursion

The above statistics are based on the full distribution of particle displacements. The moments of the distribution of the maximal displacement of the trajectories from their starting points can also be used to distinguish different types of anomalous diffusion (38). We first determined rM(t), the maximal displacement of each tracked CD93 molecule from its initial position at t = 0 over a measurement time t. The mean maximal excursion (MME) is the average of rM over an ensemble of particles. The second and fourth moments of the distribution of maximal displacements, referred to as MME moments, are given by

| (5) |

and

| (6) |

where the overbar indicates an average over the ensemble of N trajectories. The ratio

| (7) |

is referred to as the MME ratio. The analogous ratio for the full distribution of displacements,

where is the EA-MSD introduced above, and

| (8) |

is the fourth moment of the distribution of r, is referred to as the regular ratio.

The values of these ratios are different for different models of diffusion. For Brownian motion, RR = 2 and RM = 1.49. Diffusion on a fractal gives RR < 2 and RM < 1.49, whereas FBM gives RR = 2 and RM < 1.49. Values of these ratios higher than those for normal Brownian motion indicate diffusion by CTRW (38).

Windowed diffusion analysis

To assess the temporal evolution of diffusion in individual CD93 trajectories over the course of the experiment in real time, the ensemble of trajectories for all corralled CD93 molecules was filtered to remove any trajectories less than 5 s in duration. A window encompassing the current time point of ±5 frames was applied to each point of each track, the average particle position was calculated for each window, and MSS analysis (35, 39) was applied to the segment of the trajectory within the window. Based on the results of this analysis as a function of time over the length of the trajectory, the corralled tracks could be classified as stably corralled (i.e., all windows were classified as corralled, with no significant change in the average particle position); undergoing hop diffusion (i.e., all segments classified as corralled but with more than one distinct particle position with no overlap of the corral area); undergoing transient escape (i.e., initially corralled tracks containing periods of free diffusion separated by periods of corralling or tracks that escaped corralling within 2 s of the end of the track), or escaped (i.e., free diffusion for ≥2 s without reconfinement for the remainder of the track).

Surface confinement and endocytosis analysis

Surface CD93 was labeled at saturation by incubating with a 1:100 dilution of a 1:10,000 mixture of unlabeled:Cy3-labeled 12CA5 Fab for 10 min at 10°C. Cells were then washed 3× with PBS and stored at 10°C until imaged, at which point they were mounted in Leiden chambers filled with 37°C imaging buffer containing 1:1000 dilution of Alexa-488 conjugated 12CA5 Fab fragments. For diffusion analysis, five random fields were selected for imaging, and short (50 frame) 488 and Cy3 channel SPT videos were collected in each field every 5 min for 30 min. Cy3-labeled and 488-labeled CD93 were individually tracked and classified as free or corralled, as described above. As controls, cells fixed for 20 min with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) before labeling or live cells pretreated for 20 min with 1 mM N-ethylmaleimide or 5 μg/mL brefeldin A were labeled as above, and the number of 488-labeled CD93 present on each cell were quantified from images taken every 5 min for 30 min. To assess colocalization with Arf6 and Rab11, cells ectopically expressing HA-CD93 plus either Arf6-GFP or Rab11-GFP were labeled with saturating concentrations (1:100 dilution) of Cy-3 labeled 12CA5 Fab fragments at 10°C. The cells were then washed 3× with PBS, a 1:1000 dilution of 647-labeled 12CA5 Fab fragments was added to label any CD93 exocytosed during the experiment, and the cells were warmed to 37°C for 1 h. The cells where then fixed with PFA and imaged as described above. The fraction of intracellular CD93 puncta colocalizing with wither Arf6 or Rab11 was then determined using FIJI.

Ground-state depletion microscopy

CD93-expressing CHO cells were treated with Brefeldin A or vehicle for 60 min and fixed with 4% PFA for 20 min at 37°C; fixation was conducted at physiological temperatures to prevent changes in CD93 distribution driven by membrane phase changes. CD93 was then immunolabeled as described above, and a second fixation was performed with 2% PFA for 10 min at room temperature. The samples were then mounted on a depression slide filled with PBS + 100 mM cysteamine, and the coverslip was sealed to the slide with Vaseline, lanolin, and paraffin. The sample was immediately transferred to a Leica SR ground-state depletion microscope, and the basolateral membrane was imaged in total internal reflection fluorescence mode. Using our MIiSR software (37), the resulting images were filtered to remove any CD93 molecules detected with >20 nm precision, and the filtered images were segmented using the Ordering Points to Identify the Clustering Structure algorithm. The roundness (40) of each segmented CD93 cluster was calculated as follows:

| (9) |

Puncta with a roundness of >0.5 (for an ellipse, equivalent to a length:width ratio <2:1) were defined as “point-like,” and any cluster not meeting this criterion was classified as “web-like.”

Statistical analyses

Unless otherwise noted, data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey correction in Graphpad Prism. The statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

CD93 undergoes anomalous diffusion

The diffusion of CD93 was recorded using SPT microscopy. CD93 trajectories were reconstructed using a robust tracking algorithm that utilizes mixture-model fitting to detect single fluorophores in dense fluorophore fields and a global combinatorial optimization approach to link particles from successive frames into tracks (35), followed by MSS analysis applied to TAMSDs calculated for individual tracks (39) to identify freely diffusing and corralled populations of CD93. As is typical of transmembrane proteins, a large fraction of CD93 underwent corralled diffusion (Fig. 1 A), indicative of trapping in membrane corrals (36, 41, 42, 43, 44). These corrals ranged in size, averaging 192 nm in diameter (Fig. 1 B). Using the conventional method of quantifying confined diffusion coefficients by calculating a TAMSD, at short lag times (τ < 0.5 s), we determined that diffusion occurs more slowly in corrals (Fig. 1 C). However, this analysis must be treated with caution, as it assumes a linear dependence of TAMSD on lag time, whereas MSS analysis identifies corralled populations based on nonlinear dependence (39). Moreover, this analysis uses only lag times, potentially obscuring subtler anomalous diffusion behavior (29).

Figure 1.

CD93 Diffusion is non-Brownian. The diffusion of CD93-GFP ectopically expressed on CHO cells was studied by single-particle tracking. (A) A portion of CD93 undergoing corralled versus free diffusion is shown. (B) The distribution of CD93 confinement zone sizes is shown. (C) Diffusion coefficients determined using lag times of less than 100 ms of freely diffusing CD93 and CD93 corralled in corrals of 100–500 nm diameter are shown. (D) The effect of time on the ensemble-averaged MSD of CD93-GFP is shown. (E) The effect of lag time on the EA-TAMSD of freely diffusing CD93 and CD93 in 100 and 200 nm corrals is shown. n = mean ± SEM of a minimum of three independent experiments (A–C) or the mean of a track ensemble containing 31,633 trajectories collected over three experiments. ∗p < 0.05. The paired t-test (A) or ANOVA with Tukey correction (B and C) is compared to freely diffusing CD93. To see this figure in color, go online.

We reanalyzed CD93 diffusion using EA-MSD, ), as the behavior of an EA-MSD model can help identify the correct diffusion model. Unlike TAMSD analysis, EA-MSD analysis calculates diffusion coefficients from particle displacements measured relative to the initial particle position using measurement time t rather than lag time τ, therefore allowing for the identification of processes that evolve over the course of the experiment. Unexpectedly, the EA-MSDs for both free and corralled CD93 displayed a biphasic dependence on t, with initially increasing, followed by a plateau after ∼2 s of experimental time (Fig. 1 D). For corralled populations, this plateau is consistent with confinement in both Brownian and non-Brownian models of diffusion, but it is unexpected for a freely diffusing population (6, 30, 45). The power-law indices for the rising (α1) and plateau (α2) segments of each EA-MSD plot were calculated (Table 1). As expected, both α1 and α2 were less than 1 for corralled CD93. For CD93 initially classified as freely diffusing, the EA-MSD was linear at low values of t (α1 ≈ 1.0), which was consistent with Brownian motion. However, for t > 2.0 s, the motion of these molecules became subdiffusive, with α2 ≈ 0.46. This behavior is inconsistent with Brownian diffusion and indicates that even those molecules initially classified as freely diffusing are in fact undergoing some form of anomalous diffusion. Next, the EA-TAMSDs were calculated for freely diffusing CD93 and CD93 in 100 and 200 nm corrals (Fig. 1 E). The nearly linear relationship between EA-TAMSD and τ observed for the free CD93 ensemble is inconsistent with FBM or motion in a fractal environment, whereas the sublinear dependence of the EA-TAMSD on τ observed for confined CD93 is consistent with several models of anomalous diffusion.

Table 1.

Power-Law Indices of EA-MSD Plots at Early and Late Periods of Experimental Time

| Ensemble | α1 | α2 |

|---|---|---|

| 100 nm | 0.31 | 0.00 |

| 200 nm | 0.25 | 0.03 |

| 300 nm | 0.36 | 0.28 |

| 400 nm | 0.44 | 0.07 |

| Free | 0.96 | 0.46 |

SPT/MSS analysis (39) was used to generate CD93-GFP ensembles for freely diffusing molecules and molecules in confinement zones ranging from 100 to 400 nm in diameter, and the EA-MSD plots for CD93 in all ensembles were determined. The power-law indices for the resulting EA-MSD plots were then determined at early (0.1–2.0 s) and late (2.0–12.0 s) periods of experimental time.

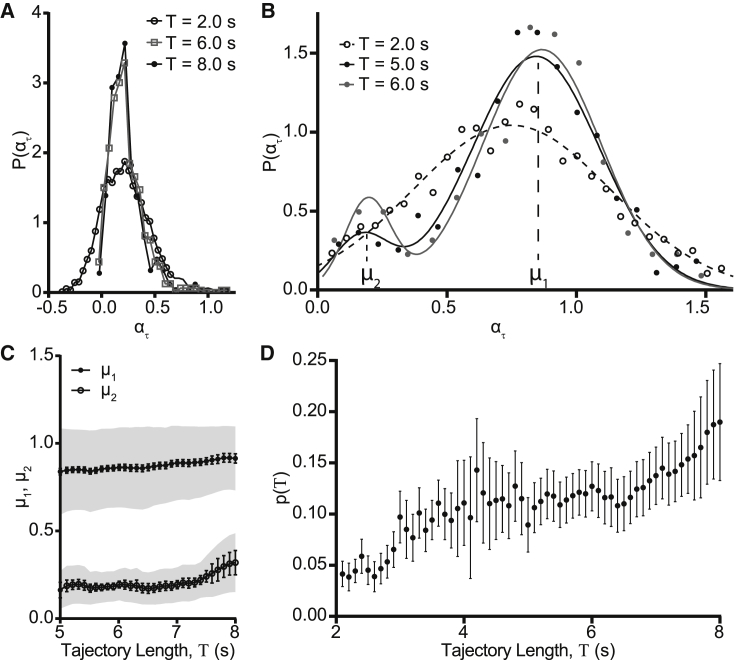

To investigate this non-Brownian behavior further, we determined the power-law index characterizing the TAMSD as a function of lag time τ for trajectories of a given length T, as in Eq. 4, in the methods. For a population undergoing Brownian diffusion, the statistical distribution of is expected to be narrow (45). Fig. 2 A illustrates the TAMSD for 40 randomly selected CD93 molecules classified as freely diffusing by MSS analysis for trajectories of length T = 2.0 s. In contrast to what is expected for a Brownian population, these molecules showed a high variation in their effective diffusion coefficient. Similar results were obtained for corralled molecules for a range of track lengths and corral sizes, as illustrated in Fig. 2 B for 200 nm corrals and T = 5.0 s. The distribution of for the freely diffusing population plotted in Fig. 2 A was approximately Gaussian, whereas the distribution for the 200 nm corralled CD93 plotted in Fig. 2 B was distinctly non-Gaussian (Fig. 2 C). Both the freely diffusing and corralled CD93 had mean power-law indices of <1.0, indicating that both populations were moving subdiffusively.

Figure 2.

CD93 diffusional anomalies revealed by time-averaged MSD. Time-averaged MSD curves were calculated for individual CD93-GFP for trajectory lengths Τ = 2.0 s (free CD93) and 5.0 s (CD93 in 200 nm corrals). (A and B) Log-log plots of time-averaged MSD curves for 40 randomly selected CD93-GFP molecules that were freely diffusing (A) or corralled in 200 nm corrals are shown (B). (C) The distribution shows the power-law index ατ of time-averaged MSD plots for freely diffusing and corralled CD93. The power-law indices of free CD93 were normally distributed with a mean slightly less than the value of 1 expected for Brownian diffusion; ατ for CD93 in 200 nm corrals was not normally distributed and had a much smaller mean value. Data are representative of (A) and (B) or are an ensemble obtained from three independent experiments (C).

CD93 diffuses by a CTRW mechanism

To distinguish between several potential models of anomalous diffusion, we evaluated the dependence of EA-TAMSD on T for a lag time of τ = 0.1 s. The lowest available value of was used to maximize the number of available data points. EA-TAMSD decreases with increasing T as a power law with a negative power-law index αT (Fig. 3 A). This behavior is consistent with both CTRWs and confined CTRWs but not with ergodic models of anomalous diffusion such as FBM (29, 45, 46). Table 2 summarizes the power-law indices α, ατ, and αΤ, which characterize the dependence of EA-MSD on t, EA-TAMSD on τ, and EA-TAMSD on T, respectively. For uncorralled CD93, these indices are in good agreement with the predictions for a subdiffusive CTRW, for which and , with . The indices found for 100 and 200 nm, corralled CD93 agree well with those expected for particles engaged in a confined, subdiffusive CTRW at long times (T≫τ, EA-TAMSD , for which and , with (6, 45, 46). To further confirm that CD93 was diffusing via CTRW, MME analysis was applied to the freely diffusing CD93 ensemble and found to be consistent with diffusion via CTRW for all t > 0.1 s (Fig. 3 B). Consistent with CTRW, the regular moment ratio RR was consistently greater than 2.0 and the MME moment ratio RM was above 1.49 for all evaluated measurement times (Fig. 3 C). In contrast, these results are not consistent with FBM or diffusion on a fractal, for which RM < 1.49, RR = 2 (FBM) and RM < 1.49, RR < 2 (fractal), respectively. Our data, therefore, indicate that freely diffusing CD93 in fact moves via a subdiffusive CTRW.

Figure 3.

CD93 diffusion is consistent with CTRW. Mean maximal excursion analysis of freely diffusing CD93 was performed to identify the model that best describes the diffusion of CD93. (A) The effect of trajectory length on the EA-TAMSD is shown. (B) The effect of experimental time on the EA-MSD (regular) and second MME (MME) moments is shown. (C) The effect of experimental time on the ratios between the second and fourth EA-MSD moments (regular) and the second and fourth MME moments (MME) is shown. Horizontal lines indicate the regular (dotted line) and MME (dashed line) moment ratios predicted for Brownian motion; ratios above these values are expected for CTRW. Data are the ensemble of three independent experiments.

Table 2.

Power-Law Indices of CD93 MSDs, Ensemble-Averaged MSDs, and Ensemble-Averaged and Time-Averaged MSDs

| Ensemble |

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| α, t ≥ 3 s | ατ, Τ ≥ 2 s | αΤ, τ = 0.1 s | |

| Free | 0.46 ± 0.02 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | -0.458 ± 0.005 |

| 100 nm | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | -0.297 ± 0.002 |

| 200 nm | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | -0.283 ± 0.002 |

SPT/MSS analysis (39) was used to generate CD93-GFP ensembles for freely diffusing molecules and molecules in 100 or 200 nm confinement zones, and the dependence of EA-MSD on t, EA-TAMSD on τ, and EA-TAMSD on T was calculated.

Nonsymmetric evolution of CD93 diffusion

To investigate the temporal evolution of CD93 diffusion, we investigate the dependence of on the trajectory length T for both free and corralled CD93. For corralled CD93, the probability distribution P of was roughly Gaussian with a mean that did not vary significantly with T, which was indicative of a single population whose diffusional properties do not change over time (Fig. 4 A). In marked contrast, P for freely diffusing CD93 is Gaussian with a mean of μ1 = 0.756 for short trajectories, whereas for longer tracks, a second peak centered at μ2 = 0.197 emerges (Fig. 4 B). This indicates the appearance over time of a second, distinct population of molecules with different diffusion behavior, suggesting that some of the CD93 that was initially freely diffusing became trapped in corrals as the experiment progressed (Fig. 4 B). To investigate this further, we fitted the P data for each trajectory length to a sum of two Gaussians and extracted the mean value of for the high-mobility (μ1) and low-mobility (μ2) populations. Both μ1 and μ2 were independent of T (Fig. 4 C). This indicates that the diffusional environment of the two populations did not change significantly over the duration of the experiment. The μ2 (corralled) peak was first detectable at s, and the fraction of the detected CD93 contributing to this peak increased approximately linearly with T, with 19 ± 6% of the CD93 that was originally freely diffusing becoming corralled after 8 s of observation (Fig. 4 D). This suggests that the diffusion of CD93 evolves in a nonsymmetric manner over real time: freely diffusing CD93 becomes increasingly corralled without being replenished by CD93 escaping from corrals. In the absence of other replenishment processes, this would inevitably lead to the confinement of all CD93 in corrals. Because this contradicts what is observed, replenishment of free CD93 must occur by another cellular process.

Figure 4.

Time-averaged MSDs evolve over experimental time. Power-law indices were determined from the TAMSDs of freely diffusing and corralled CD93 for trajectory lengths from 2 to 8 s. (A) The distribution shows power-law indices ατ for corralled CD93 at Τ = 2.0, 6.0, and 8.0 s. (B) The distribution shows ατ for freely diffusing CD93 at Τ = 2.0, 5.0, and 6.0 s. The two peaks centered at exponent values μ1 and μ2 indicate the presence of two distinct populations that diffuse at different rates. (C) The mean and SE of ατ values for the more diffusive (μ1) and less diffusive (μ2) populations of CD93 originally identified as uncorralled are shown, calculated by fitting the distribution of power-law indices to the sum of two Gaussians for total measurement times from 5 to 8 s. (D) The fraction of CD93 initially classified as freely diffusing appears in the less-diffusive population as a function of T. n = 3, Data are presented as mean ± SEM (error bars) or mean ± SD (shaded areas).

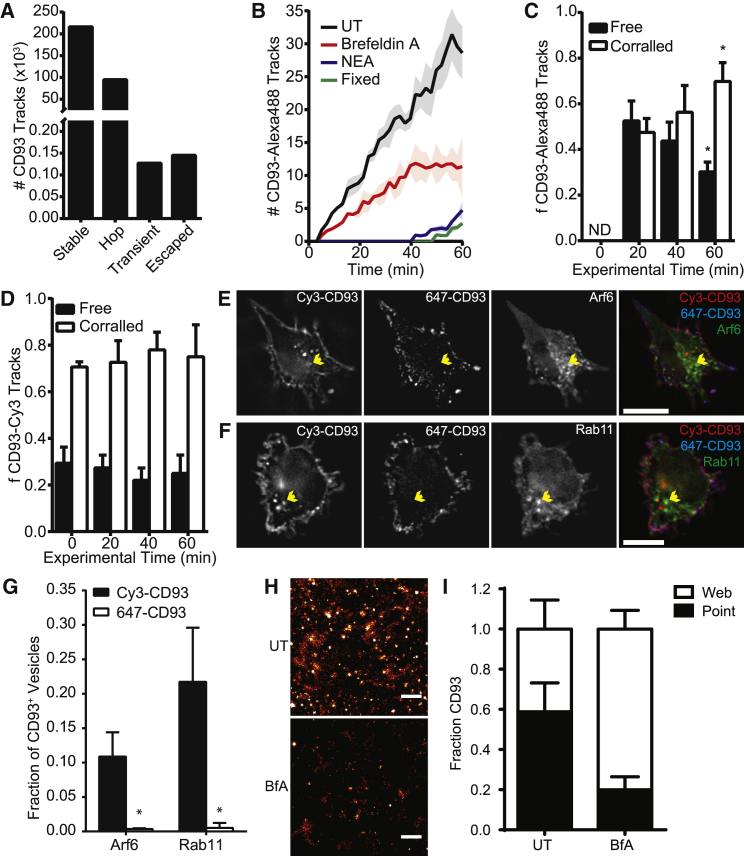

Endocytosis and exocytosis maintain freely diffusing CD93 populations

We confirmed that the observed change in diffusion behavior with track length was not an artifact of our analysis methods by breaking the trajectories of CD93 initially classified as corralled into windows 1 s in duration and investigating how the diffusional behavior and position of each trajectory changed as the window was progressively moved through the time course. The vast majority of CD93 was found to be either stably corralled or undergoing hop diffusion, with only 272 of the 311,347 analyzed CD93 trajectories undergoing transient or total escape from corrals (Fig. 5 A). This confirms that once CD93 is corralled, it remains corralled. The freely diffusing population of CD93 must therefore be replenished by a different process. The endocytic uptake of receptors from the plasma membrane followed by their replenishment through a combination of exocytosis from recycling compartments and secretion of de novo synthesized CD93 from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)/Golgi are possible mechanisms by which the freely diffusing population of CD93 could be maintained. To test this, CHO cells were transfected with CD93 bearing a single extracellular HA tag and cell-surface CD93 labeled at saturating levels with a 10,000:1 ratio of unlabeled:Cy3-labeled monoclonal anti-HA Fab fragments. SPT was then performed in a solution containing Alexa488-labeled anti-HA Fab fragments to label any CD93 exocytosed over the course of the experiment. We then recorded SPT videos of 488- and Cy3-labeled CD93, imaging the same cells every 5 min over a 60 min period. The number of Alexa-488 labeled CD93 molecules increased linearly with time. Similar increases were not observed in cells fixed before labeling or in cells in which exocytosis was blocked with 1 mM N-ethylmaleimide, whereas blocking Golgi export with brefeldin A had a partial inhibitory effect that strengthened over time (Fig. 5 B). A much larger portion of recently exocytosed (488-labeled) CD93 underwent free diffusion than did the preexisting surface (Cy3-labeled) CD93, and in accordance with the above results, the corralling of the recently released CD93 increased over time (Fig. 5 C). Interestingly, the portion of preexisting surface (Cy3-labeled) CD93 undergoing free diffusion did not change with time, suggesting that recently synthesized CD93 is not the only source of labeled free CD93 (Fig. 5 D). Consistent with this, preexisting surface (Cy3-labeled) CD93 was found to be preferentially endocytosed and to partially associate with markers of the slow (Rab11-GFP) and fast (Arf6-GFP) recycling compartments (Fig. 5, E–G), whereas recently exported (647-labeled) CD93 was not. Superresolution imaging of CD93 at 20 nm resolution determined that CD93 is normally found on the cell surface in a combination of web-like structures and small, circular puncta (Fig. 5 H), which is similar to the distribution we previously reported for CD9 (36). N-ethylmaleimide treatment caused membrane blebbing, precluding assessment of CD93 distribution in the absence of both endocytosis and exocytosis. However, brefeldin A inhibition of exocytosis from the ER/Golgi depleted ∼50% of the surface CD93 through selective depletion of the punctuate portion of surface CD93, indicating the role of exocytosis in generating the heterogeneous distribution of CD93 in the plasma membrane (Fig. 5, H and I).

Figure 5.

CD93 diffusion is sustained by membrane recycling. (A) The number of particle tracks for corralled CD93 classified as stabile corralled (stable), undergoing hop diffusion (hop), transiently escaping confinement (transient), or totally escaping confinement (escaped) is shown. (B) The number of newly exocytosed CD93 tracks measured after treatment with brefeldin A, N-ethylmaleimide (NEA), or fixation of the cell with PFA (fixed) is shown. (C) A portion of CD93 exocytosed during imaging classified as freely diffusing and corralled is shown over the course of the experiment. (D) A portion of CD93 present on the cell surface before imaging is classified as freely diffusing and corralled over the course of the experiment (E–G) Representative images (E and F) and quantification (G) of colocalization of HA-CD93 present on the cell surface at the beginning of the experiment (Cy3-CD93) are shown as well as recently exocytosed CD93 (647-CD93) with Arf6-GFP or Rab11-GFP after a 1 h incubation. Arrows indicate vesicles positive for Cy3-CD93 and Arf6 or Rab11. Scale bars, 10 μm. (H) Superresolution images show the distribution of CD93 in untreated versus brefeldin-A-treated cells. Scale bars, 500 nm. Images are presented as heat maps. (I) The effect of brefeldin A on the fraction of CD93 located in puncta (point) versus web-like structures (web) is shown. Data are presented as mean (A) or mean ± SEM (B–D and G), n = 5. ∗p < 0.05 compared to the same group at 20 min (C and D, ANOVA with Tukey correction) or to Cy3-CD93 in the same cells (G, paired t-test). ND, none detected.

Discussion

Ever since the fluid-mosaic model of the plasma membrane was proposed by Singer and Nicolson (47), efforts have been made to develop a model that accurately describes molecular motion in the plasma membrane. Although early models proposed that membrane diffusion would occur as Brownian diffusion in a two-dimensional planar fluid (48), experiments on intact cells revealed that membrane diffusion is non-Brownian; moreover, they determined that the same proteins and lipids can display different diffusional behavior depending on the temporal resolution and duration over which the diffusion is measured (reviewed in (2, 44)). This complex diffusional behavior appears to be due to several factors, including molecular crowding within the membrane, the presence of diffusion-limiting cellular structures such as membrane-proximal actin corrals, and heterogeneity in membrane composition (5, 15, 23, 29, 49, 50). More recent work has led to a range of anomalous diffusion models being proposed as possible descriptors of diffusion in cellular membranes, but it remains unclear which, if any, of these models accurately describes plasma membrane diffusion (29, 51). In this study, we have demonstrated that diffusion of the single-pass membrane protein CD93 is well described by CTRW and specifically eliminated FBM and diffusion on a fractal as possible mechanisms of CD93 diffusion. Moreover, we showed that the trapping and endocytosis of CD93 in membrane corrals, in parallel with exocytosis of CD93 from the ER/Golgi and recycling pathways, are required to maintain this diffusional pattern.

The diffusional behavior of membrane proteins provides information about the underlying molecular and cellular processes producing the behavior, with different molecular and cellular interactions leading to differing relationships between molecular step size and frequency and to different behavior on different timescales. Brownian motion occurs only when diffusing molecules engage in uncorrelated, elastic collisions in a uniform environment (2). This is not a realistic description of the motion of proteins in biological membranes, given the high molecular packing and the presence of a variety of intermolecular interactions, microdomains, and diffusional barriers that act over a broad range of spatial and temporal scales. FBM, diffusion on a fractal, and CTRW have all been proposed as descriptors of diffusion in the complex environment of a biological membrane (2, 29, 52). A particle diffusing on a fractal exhibits subdiffusive motion governed by the dimension of the fractal (53). Subdiffusive FBM has been applied to characterize motion in a viscoelastic medium with long time correlation, wherein particles undergoing FBM revisit past locations (45). Temporary immobilization of membrane molecules, conversely, has been described with the aid of CTRW. The CTRW model has previously been applied to characterize the diffusion of Kv2.1 potassium channels in the plasma membrane and the motion of water molecules on the membrane surface (29, 54).

Our initial statistical analysis of CD93 motion with respect to the dependence of the EA-MSD on time revealed that CD93 diffusion is anomalous and subdiffusive, with plateaus characteristic of particle confinement for the corralled CD93 populations. The observed subdiffusive behavior is a feature of several diffusion models, including CTRWs, FBM, and diffusion on a fractal (45). The high variation in the diffusion coefficients of the TAMSDs of individual CD93 tracks is, however, more consistent with the CTRW model than with FBM (6, 30). Likewise, the nearly linear relationship of the EA-TAMSD with τ observed for free CD93 is consistent with the CTRW model but not with FBM or motion in a fractal environment (45). Furthermore, the dependence of the EA-TAMSD on trajectory length observed for all CD93 populations, indicative of system aging, is in line with the behavior predicted for CTRWs but not for ergodic processes such as FBM or motion in a fractal environment. Overall, the properties and power-law indices of freely diffusing CD93 were found to be consistent with a subdiffusive CTRW, whereas corralled CD93 was consistent with a confined subdiffusive CTRW. Indeed, CD93 trajectories defined as freely diffusing by the MSS software (35, 39) have EA-MSD and EA-TAMSD characterized by and , respectively, with , which is in good agreement with the predictions for subdiffusive CTRW (45, 46). MME analysis supported this result (38). CD93 defined as corralled by MSS analysis (MSD power-law index showed different relationships between EA-MSD, EA-TAMSD and t, and τ and Τ, with and for , which is consistent with diffusion via confined subdiffusive CTRW occurring over long timescales (6, 30).

Subdiffusive CTRWs arise when particles move by a series of random jumps interrupted by “sticking” or “trapping” events with power-law-distributed waiting times. The immobilization events underlying CD93 motion in the model of a CTRW may have several biological origins. In the plasma membrane, temporary molecular immobilization is thought to arise from transient interactions with a macromolecular complex or a cytoskeletal component (2). Most interactions possess a specific dissociation coefficient, which results in an exponentially distributed waiting-time distribution (29). Power-law-distributed waiting times can, however, arise from nonstationary or heterogeneous interactions. For example, if a particle binds to a growing macromolecular complex, its dissociation coefficient may change with time. In cases in which the probability of its escape decreases as the complex grows, the particle dissociation times have been shown to become power law distributed, resulting in an evolution toward a CTRW over time (29, 55). Alternatively, a CTRW may arise if a particle interacts with more than one binding partner or macromolecular complex, resulting in a distribution of dissociation coefficients that leads to a heavy-tailed power-law distribution of waiting times. Nothing precludes such interactions from occurring for CD93 either within or outside of confinement zones. Indeed, CD93 has been reported to interact with both moesin and GIPC through its cytosolic tail as well as with cholesterol-stabilized membrane cages independently of its intracellular domain (56, 57). In principle, these interactions could result in the power-law-distributed waiting times characteristic of CTRW and are to be investigated further. Although these studies and our data are consistent with nonergodic diffusion occurring via CTRW driven by interactions with macromolecular or cytoskeletal structures, other studies have ascribed this breaking of ergodicity by membrane proteins to diffusion in a heterogeneous diffusion environment (49, 50). Both mechanisms likely contribute to the observed diffusion patterns, potentially operating at different length and timescales. Indeed, transient structures such as lipid rafts (<20 nm, lifespans of 10–20 ms) would create a heterogeneous diffusive environment not observable at the time- and spatial-scales of our experiments but would account for the subdiffusive behaviors observed and modeled by others at these spatiotemporal scales (8, 13). Additional sources of nonergodicity may include cellular processes and structures—for example, membrane flow created by exocytosis and endocytosis, and actin barriers that form compartmentalized “corrals” in the plasma membrane (16, 58, 59, 60, 61).

The system aging associated with CTRW implies the eventual caging of all freely diffusing particles unless the pool of freely diffusing particles is somehow replenished. Indeed, in this study, we directly observed a gradual reduction in the diffusion coefficient of free CD93. The short-term reduction in the diffusion coefficient of free CD93 over time was found to be due to their motion by a subdiffusive CTRW. The reduction in the diffusion coefficient of free CD93 at longer measurement times (> s) is, however, due to another biological process: the capture of freely diffusing CD93 into membrane corrals. The capture of freely diffusing molecules into membrane corrals has been previously reported for several proteins and is believed to be a major component of hop diffusion within cellular membranes (4, 5, 15). Contrary to the hop diffusion model of membrane diffusion, in which trapping in corrals is generally on the scale of milliseconds, we observed this trapping to be stable, with corralled CD93 rarely escaping from corrals over periods of many seconds. Indeed, our data suggest that corralling is a prelude to endocytosis, with the endocytosis of corralled CD93 and subsequent exocytosis of de novo synthesized and recycled CD93 maintaining the freely diffusing population of CD93. Consistent with our observations, it has been shown that sites of endocytosis restrict diffusion and that actin (and therefore, actin-dependent corrals) must be cleared from secretory vesicle fusion sites before exocytosis (62, 63, 64). The colocalization of CD93 with the Rab11 and Arf6 recycling compartments and the observation that blocking Golgi export only blocked ∼50% of CD93 exocytosis indicate the importance of both recycling and de novo CD93 synthesis for maintaining normal CD93 diffusion. This is likely a process ubiquitous for most cell surface receptors—indeed, several receptors, including phagocytic Fc receptors and the endocytic receptor CD36, are known to require ongoing recycling and maintenance of an appropriate diffusional environment for their activity. This is consistent with processes analogous to the caging-endocytosis-exocytosis process that we have observed here being required for the maintenance of proteins other than CD93 (26, 41, 65, 66, 67). Moreover, our data demonstrate that CD93 is nonuniformly distributed in the plasma membrane, with exocytosis from the ER/Golgi responsible for maintaining highly punctuate CD93 clusters in the plasma membrane. These data are consistent with the model proposed by Gheber et al., which predicted that the delivery and removal of membrane proteins by vesicular trafficking would be required to form and maintain stable membrane domains (68) and demonstrated that both vesicular trafficking and diffusion barriers determine the size and lifetime of protein clusters on the cell surface (58, 59, 60).

In summary, we have demonstrated that the type 1 membrane protein CD93 diffuses in the plasma membrane via a CTRW mechanism or by a similar nonergodic diffusive process and that the aging and continued functioning of this CTRW process is dependent on a sequential process comprising the trapping of freely diffusing CD93 into corrals, endocytosis of corralled CD93, and regeneration of the freely diffusing pool of CD93 by the exocytosis of both de novo synthesized and recycled CD93. Although our investigation was limited to CD93, the motion of other membrane proteins, including the multispan Kv2.1 potassium channel, has been ascribed to CTRW (29), suggesting that these processes regulating CD93 diffusion identified in this study may represent a general model of protein diffusion in the plasma membrane.

Author Contributions

M.G. performed all the experiments except those in Fig. 5. M.G. and J.R.d.B. developed the framework for the diffusion analysis. B.H. performed the experiments in Fig. 5 and oversaw the study. All authors contributed to the design and analysis of the experiments and to the writing of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jessica Ellins for generating the CD93-GFP and HA-CD93 constructs.

This study was funded by National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery grants to B.H. and J.R.d.B. and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Operating grant (MOP-123419) to B.H. M.G. was funded by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council postgraduate scholarship. The funding agencies had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Editor: Joseph Falke.

References

- 1.Kusumi A., Nakada C., Fujiwara T. Paradigm shift of the plasma membrane concept from the two-dimensional continuum fluid to the partitioned fluid: high-speed single-molecule tracking of membrane molecules. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2005;34:351–378. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.34.040204.144637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krapf D. Mechanisms underlying anomalous diffusion in the plasma membrane. Curr. Top. Membr. 2015;75:167–207. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctm.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wieser S., Moertelmaier M., Schütz G.J. (Un)confined diffusion of CD59 in the plasma membrane determined by high-resolution single molecule microscopy. Biophys. J. 2007;92:3719–3728. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.095398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujiwara T., Ritchie K., Kusumi A. Phospholipids undergo hop diffusion in compartmentalized cell membrane. J. Cell Biol. 2002;157:1071–1081. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murase K., Fujiwara T., Kusumi A. Ultrafine membrane compartments for molecular diffusion as revealed by single molecule techniques. Biophys. J. 2004;86:4075–4093. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.035717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neusius T., Sokolov I.M., Smith J.C. Subdiffusion in time-averaged, confined random walks. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2009;80:011109. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.80.011109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bel G., Barkai E. Weak ergodicity breaking in the continuous-time random walk. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;94:240602. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eggeling C., Ringemann C., Hell S.W. Direct observation of the nanoscale dynamics of membrane lipids in a living cell. Nature. 2009;457:1159–1162. doi: 10.1038/nature07596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammond G.R.V., Sim Y., Irvine R.F. Reversible binding and rapid diffusion of proteins in complex with inositol lipids serves to coordinate free movement with spatial information. J. Cell Biol. 2009;184:297–308. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munguira I., Casuso I., Scheuring S. Glasslike membrane protein diffusion in a crowded membrane. ACS Nano. 2016;10:2584–2590. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sonnleitner A., Schütz G.J., Schmidt T. Free Brownian motion of individual lipid molecules in biomembranes. Biophys. J. 1999;77:2638–2642. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77097-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaz W.L., Criado M., Jovin T.M. Size dependence of the translational diffusion of large integral membrane proteins in liquid-crystalline phase lipid bilayers. A study using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. Biochemistry. 1982;21:5608–5612. doi: 10.1021/bi00265a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeon J.-H., Javanainen M., Vattulainen I. Protein crowding in lipid bilayers gives rise to non-Gaussian anomalous lateral diffusion of phospholipids and proteins. Phys. Rev. X. 2016;6:21006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kusumi A., Fujiwara T.K., Suzuki K.G. Dynamic organizing principles of the plasma membrane that regulate signal transduction: commemorating the fortieth anniversary of Singer and Nicolson’s fluid-mosaic model. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012;28:215–250. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100809-151736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujiwara T.K., Iwasawa K., Kusumi A. Confined diffusion of transmembrane proteins and lipids induced by the same actin meshwork lining the plasma membrane. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2016;27:1101–1119. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-04-0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sadegh S., Higgins J.L., Krapf D. Plasma membrane is compartmentalized by a self-similar cortical actin meshwork. Phys. Rev. X. 2017;7:011031-1–011031-10. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevX.7.011031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheetz M.P., Schindler M., Koppel D.E. Lateral mobility of integral membrane proteins is increased in spherocytic erythrocytes. Nature. 1980;285:510–511. doi: 10.1038/285510a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt K., Nichols B.J. A barrier to lateral diffusion in the cleavage furrow of dividing mammalian cells. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:1002–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saka S.K., Honigmann A., Rizzoli S.O. Multi-protein assemblies underlie the mesoscale organization of the plasma membrane. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4509. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Espenel C., Margeat E., Milhiet P.E. Single-molecule analysis of CD9 dynamics and partitioning reveals multiple modes of interaction in the tetraspanin web. J. Cell Biol. 2008;182:765–776. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Möckl L., Horst A.K., Bräuchle C. Microdomain formation controls spatiotemporal dynamics of cell-surface glycoproteins. ChemBioChem. 2015;16:2023–2028. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201500361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murakoshi H., Iino R., Kusumi A. Single-molecule imaging analysis of Ras activation in living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:7317–7322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401354101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Zanten T.S., Gómez J., Garcia-Parajo M.F. Direct mapping of nanoscale compositional connectivity on intact cell membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:15437–15442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003876107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang X.H., Mirchev R., Hemler M.E. CD151 restricts the α6 integrin diffusion mode. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:1478–1487. doi: 10.1242/jcs.093963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe S., Rost B.R., Jorgensen E.M. Ultrafast endocytosis at mouse hippocampal synapses. Nature. 2013;504:242–247. doi: 10.1038/nature12809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox D., Lee D.J., Greenberg S. A Rab11-containing rapidly recycling compartment in macrophages that promotes phagocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:680–685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kusumi A., Fujiwara T.K., Suzuki K.G.N. Membrane mechanisms for signal transduction: the coupling of the meso-scale raft domains to membrane-skeleton-induced compartments and dynamic protein complexes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012;23:126–144. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goiko M., de Bruyn J.R., Heit B. Short-lived cages restrict protein diffusion in the plasma membrane. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:34987. doi: 10.1038/srep34987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weigel A.V., Simon B., Krapf D. Ergodic and nonergodic processes coexist in the plasma membrane as observed by single-molecule tracking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:6438–6443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016325108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burov S., Jeon J.-H., Barkai E. Single particle tracking in systems showing anomalous diffusion: the role of weak ergodicity breaking. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13:1800–1812. doi: 10.1039/c0cp01879a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Otten M., Nandi A., Heinrich D. Local motion analysis reveals impact of the dynamic cytoskeleton on intracellular subdiffusion. Biophys. J. 2012;102:758–767. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.12.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norsworthy P.J., Fossati-Jimack L., Botto M. Murine CD93 (C1qRp) contributes to the removal of apoptotic cells in vivo but is not required for C1q-mediated enhancement of phagocytosis. J. Immunol. 2004;172:3406–3414. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kao Y.-C., Jiang S.-J., Wu H.-L. The epidermal growth factor-like domain of CD93 is a potent angiogenic factor. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galvagni F., Nardi F., Orlandini M. CD93 and dystroglycan cooperation in human endothelial cell adhesion and migration adhesion and migration. Oncotarget. 2016;7:10090–10103. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaqaman K., Loerke D., Danuser G. Robust single-particle tracking in live-cell time-lapse sequences. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:695–702. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heit B., Kim H., Grinstein S. Multimolecular signaling complexes enable Syk-mediated signaling of CD36 internalization. Dev. Cell. 2013;24:372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caetano F.A., Dirk B.S., Heit B. MIiSR: molecular interactions in super-resolution imaging enables the analysis of protein interactions, dynamics and formation of multi-protein structures. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015;11:e1004634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tejedor V., Bénichou O., Metzler R. Quantitative analysis of single particle trajectories: mean maximal excursion method. Biophys. J. 2010;98:1364–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferrari R., Manfroi A.J., Young W.R. Strongly and weakly self-similar diffusion. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2001;154:111–137. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Solomon C., Breckon T. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; Chichester, UK: 2010. Fundamentals of Digital Image Processing. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaqaman K., Kuwata H., Grinstein S. Cytoskeletal control of CD36 diffusion promotes its receptor and signaling function. Cell. 2011;146:593–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong H.S., Jaumouillé V., Robinson L.A. Cytoskeletal confinement of CX3CL1 limits its susceptibility to proteolytic cleavage by ADAM10. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2014;25:3884–3899. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-11-0633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flannagan R.S., Harrison R.E., Grinstein S. Dynamic macrophage “probing” is required for the efficient capture of phagocytic targets. J. Cell Biol. 2010;191:1205–1218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jaumouillé V., Farkash Y., Grinstein S. Actin cytoskeleton reorganization by Syk regulates Fcγ receptor responsiveness by increasing its lateral mobility and clustering. Dev. Cell. 2014;29:534–546. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Metzler R., Jeon J.-H., Barkai E. Anomalous diffusion models and their properties: non-stationarity, non-ergodicity, and ageing at the centenary of single particle tracking. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014;16:24128–24164. doi: 10.1039/c4cp03465a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He Y., Burov S., Barkai E. Random time-scale invariant diffusion and transport coefficients. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;101:058101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.058101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singer S.J., Nicolson G.L. The fluid mosaic model of the structure of cell membranes. Science. 1972;175:720–731. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4023.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saffman P.G., Delbrück M. Brownian motion in biological membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1975;72:3111–3113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.8.3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Charalambous C., Muñoz-Gil G., García-March M.A. Nonergodic subdiffusion from transient interactions with heterogeneous partners. Phys. Rev. E. 2017;95:032403. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.95.032403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manzo C., Torreno-Pina J.A., Garcia Parajo M.F. Weak ergodicity breaking of receptor motion in living cells stemming from random diffusivity. Phys. Rev. X. 2015;5:11021. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Espinoza F.A., Wester M.J., Steinberg S.L. Insights into cell membrane microdomain organization from live cell single particle tracking of the IgE high affinity receptor FcϵRI of mast cells. Bull. Math. Biol. 2012;74:1857–1911. doi: 10.1007/s11538-012-9738-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Höfling F., Franosch T. Anomalous transport in the crowded world of biological cells. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2013;76:046602. doi: 10.1088/0034-4885/76/4/046602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meroz Y., Sokolov I.M., Klafter J. Subdiffusion of mixed origins: when ergodicity and nonergodicity coexist. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2010;81:010101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.81.010101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamamoto E., Akimoto T., Yasuoka K. Origin of subdiffusion of water molecules on cell membrane surfaces. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4720. doi: 10.1038/srep04720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weigel A.V., Tamkun M.M., Krapf D. Quantifying the dynamic interactions between a clathrin-coated pit and cargo molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:E4591–E4600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315202110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang M., Bohlson S.S., Tenner A.J. Modulated interaction of the ERM protein, moesin, with CD93. Immunology. 2005;115:63–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bohlson S.S., Zhang M., Tenner A.J. CD93 interacts with the PDZ domain-containing adaptor protein GIPC: implications in the modulation of phagocytosis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2005;77:80–89. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0504305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lavi Y., Edidin M.A., Gheber L.A. Dynamic patches of membrane proteins. Biophys. J. 2007;93:L35–L37. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.111567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lavi Y., Gov N., Gheber L.A. Lifetime of major histocompatibility complex class-I membrane clusters is controlled by the actin cytoskeleton. Biophys. J. 2012;102:1543–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blumenthal D., Edidin M., Gheber L.A. Trafficking of MHC molecules to the cell surface creates dynamic protein patches. J. Cell Sci. 2016;129:3342–3350. doi: 10.1242/jcs.187112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bae H.-B., Tadie J.-M., Zmijewski J.W. Vitronectin inhibits efferocytosis through interactions with apoptotic cells as well as with macrophages. J. Immunol. 2013;190:2273–2281. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mitchell T., Lo A., Eitzen G. Primary granule exocytosis in human neutrophils is regulated by Rac-dependent actin remodeling. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C1354–C1365. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00239.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vitale M.L., Rodríguez Del Castillo A., Trifaró J.M. Cortical filamentous actin disassembly and scinderin redistribution during chromaffin cell stimulation precede exocytosis, a phenomenon not exhibited by gelsolin. J. Cell Biol. 1991;113:1057–1067. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.5.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van der Schaar H.M., Rust M.J., Smit J.M. Dissecting the cell entry pathway of dengue virus by single-particle tracking in living cells. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000244. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Freeman S.A., Goyette J., Grinstein S. Integrins form an expanding diffusional barrier that coordinates phagocytosis. Cell. 2016;164:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Treanor B., Depoil D., Batista F.D. The membrane skeleton controls diffusion dynamics and signaling through the B cell receptor. Immunity. 2010;32:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Takahashi S., Kubo K., Nakayama K. Rab11 regulates exocytosis of recycling vesicles at the plasma membrane. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:4049–4057. doi: 10.1242/jcs.102913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gheber L.A., Edidin M. A model for membrane patchiness: lateral diffusion in the presence of barriers and vesicle traffic. Biophys. J. 1999;77:3163–3175. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77147-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]