Abstract

A single-cell assay of active and passive intracellular mechanical properties of mammalian cells could give significant insight into cellular processes. Force spectrum microscopy (FSM) is one such technique, which combines the spontaneous motion of probe particles and the mechanical properties of the cytoskeleton measured by active microrheology using optical tweezers to determine the force spectrum of the cytoskeleton. A simpler and noninvasive method to perform FSM would be very useful, enabling its widespread adoption. Here, we develop an alternative method of FSM using measurement of the fluctuating motion of mitochondria. Mitochondria of the C3H-10T1/2 cell line were labeled and tracked using confocal microscopy. Mitochondrial probes were selected based on morphological characteristics, and their mean-square displacement, creep compliance, and distributions of directional change were measured. We found that the creep compliance of mitochondria resembles that of particles in viscoelastic media. However, comparisons of creep compliance between controls and cells treated with pharmacological agents showed that perturbations to the actomysoin network had surprisingly small effects on mitochondrial fluctuations, whereas microtubule disruption and ATP depletion led to a significantly decreased creep compliance. We used properties of the distribution of directional change to identify a regime of thermally dominated fluctuations in ATP-depleted cells, allowing us to estimate the viscoelastic parameters for a range of timescales. We then determined the force spectrum by combining these viscoelastic properties with measurements of spontaneous fluctuations tracked in control cells. Comparisons with previous measurements made using FSM revealed an excellent match.

Introduction

The mechanical properties of the cytoskeleton of mammalian cells influence how the cells move, deform, adhere, and sense their mechanical environments (1), which are altered in many processes of great significance like tumorigenesis (2, 3, 4) and differentiation (5, 6). Therefore, a better understanding of these mechanical properties may lead not only to deeper insight into the fundamental cell biology of these processes but also to novel medical applications. Passive particle microrheology, which is based on analysis of the thermal motion of a tracer particle, is one such technique that can probe the mechanical properties of soft materials with relatively little perturbation of the material itself. However, the cellular cytoskeleton is an active mechanical system, being able to convert chemical energy mainly in the form of ATP into mechanical work and motion. At any given instant in a living cell, there are thousands of processes, involving polymerization and depolymerization, transport, enzymatic reactions, and global movement of cell migration or cytoskeletal reorganization, that agitate and liquidize the cytoskeleton and the cytoplasm (7, 8, 9). Thus, the spontaneous fluctuations of a particle embedded in the cytoskeleton are determined by the sum of thermal and active forces acting on the material properties of the cytoplasm. A more complete understanding of the mechanical properties of the cytoskeleton thus requires measurements of not only its viscoelastic material properties but also the spectrum of active forces (active mechanical properties) (10) that liquidize the cytoplasm. At thermal equilibrium, the viscoelastic properties can be related to the thermally driven fluctuations through the fluctuation dissipation theorem. However, it is complicated to disentangle the particle fluctuations driven by thermal agitation from the ones driven by active forces in live cells (11, 12, 13). To tackle this issue, the viscoelastic properties can be first determined by applying a known force and measuring the resulting displacement; then, the spectrum of active forces can be extracted from the spontaneous fluctuations (3, 13, 14, 15). A representative technique following this strategy is force spectrum microscopy (FSM) (3). FSM consists of two independent measurements: the viscoelastic properties are measured using active microrheology, whereas spontaneous fluctuations are measured by confocal microscopy. The active force spectrum is calculated using a generalized Hooke’s law to combine the two measurements. Though a powerful technique, FSM as it was originally developed requires access to advanced instruments such as optical tweezers, microinjectors, and confocal microscopes at the same time, which significantly limits its wider application. In addition, microinjecting fluorescent particles into single cells is not only tedious but also introduces nonphysiological disturbances to cells under study. A version of FSM that requires fewer instruments and is noninvasive would be of significant value.

A proposed alternative approach to separating the effects of thermal forces and active forces on the spontaneous fluctuations of intracellular particles is to inhibit general motor, polymerization, and other activities by depleting cellular ATP (3, 16, 17). If the inhibition level is sufficient, the remaining fluctuations are primarily driven by thermal forces, and the viscoelasticity of the cytoskeleton can be determined from the mean-square displacement (MSD) using the generalized Stokes-Einstein relationship (GSER) (16). The results were shown to be similar to measurements made by active microrheology (16, 17). Therefore, applying ATP depletion may remove the requirement for active microrheology measurements. However, this method is controversial. The major criticism is that the treatment with ATP-depleting chemicals cannot remove all ATP-dependent processes without significant cellular damage (18). To deal with this, the convergence of the MSDs of control and ATP-depleted cells over short timescales was used to test if the cell damage induced by ATP depletion is significant (3, 15, 16). However residual ATP levels and other intracellular energy sources, like GTPs, may still drive active fluctuations over long timescales and lead to inaccuracy in the viscoelastic properties measured. Indeed, residual ATP levels of 1–8% of normal were reported after ATP depletion (16), and the viscoelastic modulus and the scaling of the MSD with time were qualitatively different between short and long timescales (16), leading to possibly systematic errors in the determination of the viscoelastic modulus.

Subcellular organelles such as mitochondria have been proposed as an alternative to exogenous fluorescent particles, with the caveat that interpreting measurements may face additional challenges because of hard-to-characterize interactions with other subcellular structures (19). Mitochondria have been used as probe particles in several studies to measure the intracellular mechanical properties of several cell types (3, 20). Mitochondria have the additional benefit that they are abundant in most cell types and can be often found spatially distributed across cells, which enable the probing of intracellular mechanical properties with spatial resolutions (20). But using mitochondria also poses additional challenges compared to fluorescent particles. Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles that move, fuse, and divide (21, 22). Different activities of fusion and fission (division) result in different mitochondrial morphologies that can be roughly classified into three types: short and fragmented (punctate) ones, elongated and highly branched (filamentous) ones, and intermediate ones (21, 22, 23). As probe particles, punctate mitochondria are preferable among these three types because they are close to the shape of synthetic fluorescent particles. Even so, because of intrinsic heterogeneity, the morphologies (shapes and sizes) of punctate mitochondria are more variable than those of commercially available fluorescent particles. In previous studies that used mitochondria as intracellular probe particles, the complexity of their morphology was not addressed explicitly. It is unclear if mitochondrial morphologies are heterogeneous within these studies, if this heterogeneity plays any role in determining the mitochondrial fluctuations, and if this heterogeneity has been considered in the quantification. To make mitochondria function reliably as endogenous probe particles, we need to screen for punctate mitochondria of suitable morphologies and address their morphological heterogeneity.

In this article, we develop methods to carry out FSM using fluorescently labeled mitochondria as our probe particles, in which we tackle both issues summarized above. We first use morphological analysis to characterize those mitochondria that can be ideally used as an endogenous probe for intracellular mechanical properties. Using confocal imaging of ideal mitochondria, we calculate their MSDs as a function of lag time as well as the creep compliance and the distribution of directional change. We study the effect of various cytoskeletal drugs on the active mitochondrial motion to gain insight into its driving mechanisms. We analyze the distribution of directional change after ATP depletion and identify a thermally dominated timescale that we then use for viscoelasticity measurements. We calculate the force spectrum of active fluctuations by combining the spontaneous fluctuations tracked in control cells and viscoelastic properties measured in ATP-depleted cells. Our results are quantitatively very similar to those obtained by others using active microrheology. Visualizing mitochondrial motion, therefore, may be a noninvasive method with relatively low requirements for advanced instruments beyond a confocal microscope for characterizing intracellular mechanical properties.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

C3H-10T1/2 cells from a murine embryonic mesenchymal cell line were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and were used at their passages of 5–15. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlas Biologicals, Fort Collins, CO), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Fisher Scientific-Hyclone, Logan, UT) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells were seeded at 5 × 104 cells/mL the night before the experiments in uncoated glass-bottom 35 mm petri dishes (MatTeK, Ashland, MA). Mitochondria were fluorescently labeled with 200 nM MitoTracker Green FM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) or 500 nM MitoTracker Red FM (Molecular Probes) in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium for 30 min.

Chemical treatments

All chemical treatments (Table S1) were carried out right after the MitoTracker staining and incubated for 30 min for cytoskeleton-targeting chemicals or 2 h for ATP depletion at 37°C with 5% CO2. Imaging was completed 2–3 h after the treatments. The chemicals were maintained during imaging to prevent recovery. Jasplakinolide and cytochalasin D were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA), blebbistatin was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI), taxol was from Goldbio (St Louis, MO), and nocodazole, NaN3, and deoxy-glucose were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Imaging using confocal microscopy

We optimized a protocol consisting of imaging, image processing, mitochondrial tracking, and data analysis (Fig. S1 A). Cells were imaged in a 37°C environmental chamber in CO2-independent imaging medium, which consists of Leibovitz’s L-15 media (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 7 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich), and 4.5 g/L D-glucose (pH 7.0). Random isolated cells were imaged using an inverted spinning disk confocal microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) under a 60× oil-immersion objective. SlideBook 6 (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO) was used to control the hardware. Recording was taken at 10 frames per second for 100 s using a cascade II electron-multiplying charge-coupled device camera with a spatial resolution of 167 nm per pixel. The emission filter of 488 nm was used for MitoTracker Green FM, and the 580 nm filter was used for MitoTracker Red FM when blebbistatin was used.

Image processing and tracking mitochondrial fluctuations

Image processing was carried out by in-house codes programmed in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA), which are available upon request. The time-lapse images of mitochondria were processed using an image-processing protocol (details in Supporting Materials and Methods, Note S1) optimized based on an approach previously described (24, 25), including the following: 1) histogram matching (Fig. S1 B, c and d), 2) two-dimensional (2D) deconvolution (Fig. S1 B, e and f), 3) bandpass filtering (Fig. S1 B, g and h), 4) grayscale thresholding (Fig. S1 B, i and j), and 5) selection of mitochondria spanning the entire imaging period and with no interaction with other mitochondria (Fig. S1 B, k and l). The 2D centroid weighted by the intensities of each selected mitochondrion was recorded to generate the 2D tracks for further analysis.

Data analysis

From the 2D tracks, the ensemble-averaged, time-averaged MSD was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

where is lag time and brackets indicate the average over all possible lag times.

At thermal equilibrium, the creep compliance of a material is directly proportional to the MSD and characterizes its deformability (19, 26). The creep compliance can be calculated as follows:

| (2) |

where is the particle radius, is the Boltzmann constant, and is the absolute temperature.

For systems at thermodynamic equilibrium, the frequency-dependent viscoelasticity can be determined based on the GSER (27), which is briefly recapitulated in Supporting Materials and Methods, Note S2.

To incorporate the irregularities of mitochondrial morphologies, the hydrodynamic radius of a prolate (football-shaped) ellipsoid is used in place of to calculate creep compliance and viscoelasticity as follows:

| (3) |

where indicates the hydrodynamic radius and m and n are the major and minor axes of the ellipsoid, respectively. Basic morphological measurements were carried out to selected mitochondria in their first frame, where their areas, major and minor axes of minimal enclosing ellipses, and convex hull areas were measured. The aspect ratio is defined as the ratio of major axis to minor axis, and the solidity is defined as the ratio of convex hull area to mitochondrial area. Both parameters are larger than one.

Directional change was calculated from each set of three points along the trajectory determined by the lag time, as defined previously (28). Then, an ensemble-averaged, time-averaged distribution of directional change was obtained as a function of lag times (28). We have chosen to display the distribution in a [−π, π] window so that we can emphasize directionally persistent motions. To summarize the rich information contained in the distributions of directional change, an index of directional persistence, Pd, was calculated as the difference between the probabilities of forward and backward motions (18). If the motion is purely diffusive, the Pd is close to zero at all timescales. Negative Pd values indicate that the antipersistent motion is dominating. Positive Pd values show that persistent motion is dominating.

Force spectrum

The calculation of force spectrum proposed in (3) is based on the fundamental force-displacement relationship in elastic medium, i.e., Hooke’s law, , where f is the driving force, K is the spring constant, and x is the resulting displacement (3). To account for the frequency dependence of the material properties and the stochasticity of the intracellular forces, Hooke’s law is generalized into a quadratic form of the averaged quantities in the frequency domain . The frequency-dependent effective spring constant can be related to the complex shear modulus through a generalization of the Stokes relation , where d is the radius of the particle. The is obtained as the Fourier transform of the MSD .

In the two terms used to calculate the force spectrum, comes from spontaneous fluctuations of probe particles, and comes from the independent measurement of the viscoelasticity. In our system, an equivalent form was developed:

| (4) |

was calculated from the mitochondrial fluctuations in ATP-depleted cells, and the mitochondrial hydrodynamic radii associated were used rather than fluorescent particles of same sizes in the active microrheology using optical tweezers. was calculated from spontaneous mitochondrial fluctuations in control cells, and the Fourier transform was multiplied by the square of the corresponding mitochondrial hydrodynamic radius in the control cells. Then, the active force spectrum can be determined.

Statistics

The distribution of MSDs of diffusive particles is not Gaussian (29, 30), and our results appear log-normal distributed (Supporting Materials and Methods, Note S3), as also observed previously (17). In this study, the reported means and SDs are computed using logarithmic-transformed data (Supporting Materials and Methods, Note S3). The geometric coefficient of variance (GCV) is defined as , where is the variance of the logarithmic transformed data.

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test is a nonparametric alternative of Student’s t-test on the null hypothesis that the two samples are from continuous distributions with equal means, which does not assume the normality of the data and is generally insensitive to the actual distribution (31, 32). The MATLAB function ranksum was used, and differences are deemed as statistically significant for p-values less than 0.05.

To minimize the day-to-day variance, all the comparisons were made between control cells and chemical-treated cells imaged on the same day, which may give rise to slightly different results of control cells (Supporting Materials and Methods, Note S4).

Results

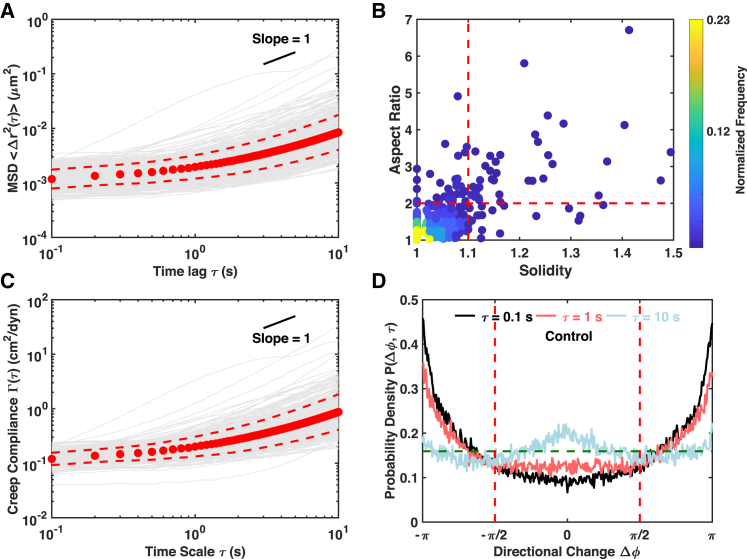

Normalizing the morphological heterogeneity of punctate mitochondria

In contrast with the relatively tight distribution of sizes of commercially available fluorescent particles, mitochondrial morphologies are very heterogeneous (Figs. 1 B and S1). A plot of the solidity against the aspect ratio shows a wide distribution of 2D projected mitochondrial morphologies, though many mitochondria were located close to the point (1,1), which corresponds to a round shape (Fig. 1 B). For simple diffusion processes, particle size heterogeneity affects the MSD through its effect on the diffusion constant, which scales as 1/a, where a is the particle size, by the Stokes-Einstein relation. The creep compliance, as shown in Eq. 2, scales out the dependence on particle size and should be able to reduce the variance contributed by morphological heterogeneity in MSD. In Eq. 2, the radius of a spherical particle is incorporated, which is not appropriate for most punctate mitochondria tracked in our cells (Fig. 1 B). We generalized the definition of creep compliance by substituting the radius of a spherical particle with the hydrodynamic radius of a prolate (football-like) ellipsoid (Eq. 3). This is analogous to the elegant work of F. Perrin in generalizing the Stokes-Einstein equation (33, 34). To make sure that this generalization is appropriate, we filtered the mitochondria close to the prolate ellipsoids as being less than 1.1 for solidity and being less than 2 for aspect ratio (Figs. 1 B and S1 B, k). At least 70% of all punctate mitochondria tracked pass this morphological filtering criteria in all data sets presented in this study (data not shown). Heterogeneity in the hydrodynamic radii is still present in the filtered mitochondria (Fig. S2). Similar to MSDs, the distribution of the hydrodynamic radii is better described by a log-normal distribution than a normal distribution (Fig. S2).

Figure 1.

Measurements based on mitochondrial fluctuations. (A and C) Individual and population mean with SDs of (A) MSDs (n = 211) and (C) creep compliance (n = 169) are shown. Gray curves are for individual mitochondria, and filled circles indicate the population mean. Dashed lines are SDs. The short black line is a visual guide of slope one. (B) A distribution of mitochondrial morphologies in a 2D space of solidity and aspect ratio is shown. Filled circles are individual mitochondria color-coded with local normalized frequencies in accordance with the colormap. The two dashed lines represent the morphological filtering criteria of solidity less than 1.1 and aspect ratio less than 2. (D) Distributions of the directional change of control cells are shown at different lag times. The dashed horizontal line indicates a uniform distribution that is characteristic of pure diffusion. To see this figure in color, go online.

The variance in creep compliance reduces significantly after the morphological filtering, especially over the short timescales (Fig. S3). To quantify and compare the variances at different levels of population means, GCVs were calculated at every lag time for both MSD and creep compliance. The GCV shows the reductions in variance by the normalization using creep compliances, and it shows even more pronounced reduction after applying the morphological filtering (Fig. S4 A). This quantification also supports the conclusions from the visual comparisons made in Fig. S3. In all the data sets reported in this study, the morphological filtering and normalization using creep compliance are able to reduce the variances (data not shown). Therefore, creep compliance after morphological filtering is reported rather than MSD in the rest of this study if not stated otherwise.

Distribution of directional change as a hypothetical signature of mechanisms underlying mitochondrial fluctuations

We observed different power-law scaling at different timescales in the control cells, similar to earlier publications (3, 14, 16, 35, 36). Over short timescales (0.5–1.5 s), the MSD curves show weak lag-time dependence with a mean power-law scaling factor of 0.35, suggesting that the mitochondrial fluctuations are dominantly subdiffusive (Fig. S4, B and C). A stronger lag-time dependence with a mean power-law scaling factor of 0.82 is observed over long timescales (6–8 s) (Fig. S4, B and C). The high variance observed in the MSDs is also significant in terms of the power-law scaling factors. Interestingly, a significant portion of the power-law scaling factors over the long timescales is larger than one (Fig. S4 C). This superdiffusive behavior is consistent with previous studies that showed that mitochondria are occasionally directly transported by molecular motors (37), thus suggesting that the mitochondrial fluctuations are also driven by active forces over long timescales in addition to thermal forces.

It has been shown using simulations that the distribution of directional change can provide more information about stochastic processes than MSD, which is essentially a one-dimensional measurement (28). In addition to the power-law scaling factors, we also calculated the distribution of directional change as a function of lag time (Fig. 1 D). Over short timescales (0.1 and 1 s), only one peak at Δø = π is present, indicating anticorrelated motion, i.e., a forward step is more likely to be followed by a backward step. This is similar to the distribution of directional change reported for subdiffusive motion in a viscoelastic environment due to caging and escape dynamics (28). Along with the increase in lag time, the peak at Δø = π gradually decays, and the peak at Δø = 0 grows and eventually becomes dominant. Thus, at the long timescales (10 s), the probability of going forward, i.e., persistent motion, dominates. The combination of “bouncing in a cage” at short timescales and persistent motion at long timescales suggests that the cage itself is drifting, probably driven by directed transport or active cytoskeletal remodeling. In fact, the distribution of directional change qualitatively matches that of a particle in a harmonic potential with drift (28). This trend is also revealed by the index of directional persistence, Pd (Fig. S4 D). The Pd of control cells starts with negative values, suggesting antipersistent motions and, in our case, the caging effects by cytoskeletal networks. With the increase in lag times, Pd gradually increases to positive values, indicating the increasing dominance of persistent motion at longer times.

Multiple ATP-dependent mechanisms are able to drive the mitochondrial fluctuations and likely to dominate over long timescales, whereas thermal forces are likely to dominate over short timescales (3, 12, 37, 38, 39). This argument is supported by our results of both power-law scaling factor and distribution of directional change. To further understand the underlying mechanisms of the mitochondrial fluctuations observed in the control cells, we carried out a series of chemical treatments targeting components of the cytoskeleton that may be involved.

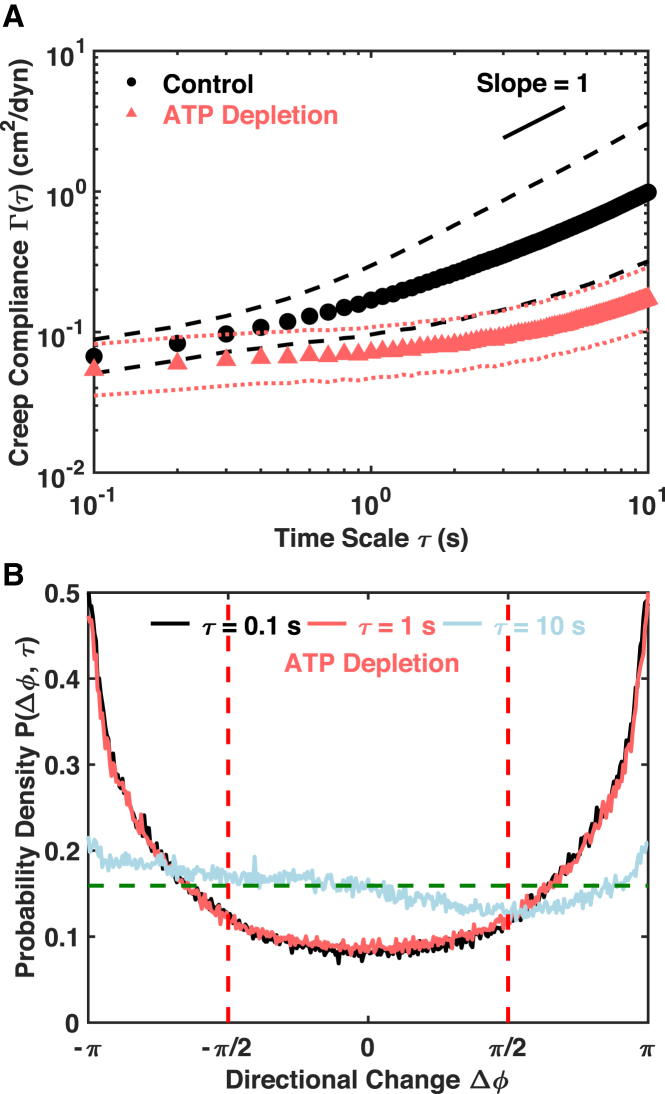

Mitochondrial fluctuations are ATP dependent over long timescales

We first tested the ATP dependence of the mitochondrial fluctuations. The C3H-10T1/2 cells were treated with 2 mM NaN3 and 2 mM deoxy-D-glucose, which inhibits ATP synthesis in the electron transfer chain and glycolysis, respectively (40, 41). Despite an overlap at the shortest timescales, the decrease in the population mean creep compliance of ATP-depleted cells is statistically significant over all timescales compared to that of the control cells (Figs. 2 A and S5 A), with significant decreases in power-law scaling factor as well (Figs. S5, C and D). The distributions of directional change remain almost the same from 0.1 s until 2 s in lag time, with the antipersistent motion dominating (Figs. 2 B and S6). Along with the increase in lag time, a decrease in antipersistent motion is observed, and the motion appears increasingly diffusive (Fig. 2 B). More importantly, no preference for persistent motion is observed at any timescales in the ATP-depleted cells. This trend is recapitulated in the Pd curve, which maintains a constant value from 0.1 s until around 2 s and then starts to approach the limit of zero (Fig. S5 E).

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial fluctuations are ATP dependent. (A) Population mean creep compliances with SDs of control (n = 169) and ATP-depleted cells (n = 156) are shown. Markers of different shapes and colors indicate population means, and the lines of the same colors are SDs. The short black line is a visual guide of slope one. (B) Distributions of directional change of ATP-depleted cells are shown at different lag times. The dashed horizontal line indicates a uniform distribution that is characteristic of pure diffusion. To see this figure in color, go online.

These results indicate that thermal forces are the dominating mechanism over the short timescale, and ATP-dependent (i.e., active) processes dominate the longer timescales in control cells. In addition, the distributions of directional change of ATP-depleted cells remain flat at Δø = 0 over timescales longer than 2 s (Fig. S6). This trend suggests that the increase in creep compliance of ATP-depleted cells over long timescales is likely due to passive escape from local “cages” due to the polymerization-depolymerization dynamics of microtubules that are driven by GTPs that are not depleted by the ATP-depletion treatment. Active yet random motion powered by residual intracellular ATP probably contributes as well. Therefore, the timescales from 0.1 to 2 s are dominated by thermal forces in ATP-depleted cells (Figs. 2 B and S5 E). The ATP dependence also implies that the creep compliance does not relate directly to the viscoelastic properties of the control cells because the system is out of thermal equilibrium. However, we will continue using creep compliance to reduce morphological heterogeneity while placing no interpretation on its physical meaning.

The cellular interior is highly heterogeneous, which is reflected in the heterogeneity of the MSD of single mitochondria and the convergence of the cell-wise creep compliance to the population mean (Fig. S14 A). The overall heterogeneity in the creep compliance is dominated by intracellular heterogeneity (Fig. S14 B). We saw no evidence of spatial correlation of intracellular mechanical properties (Fig. S14 C), possibly because the mitochondria were on average tens of microns away from each other.

We further hypothesized that the microtubule network and actin network may play important roles in forming the local cages for mitochondria. To test this, we carried out chemical treatments targeting these two important players in the cytoskeletal network.

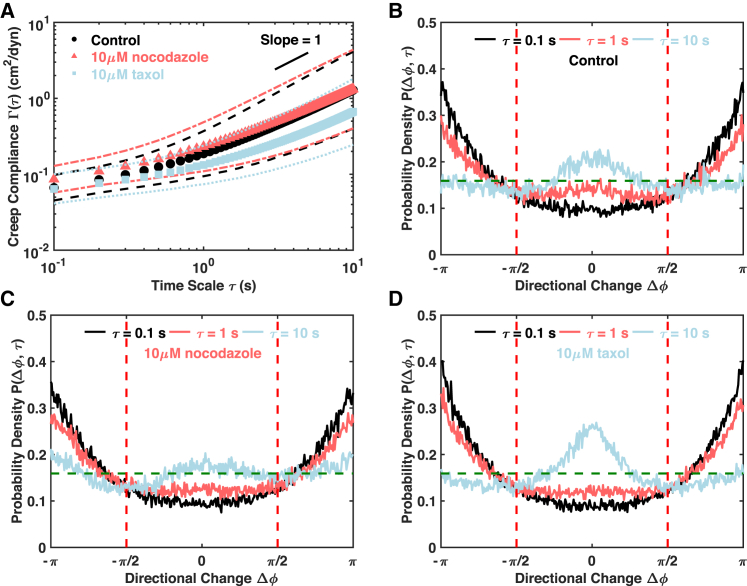

Microtubule network plays a significant role in mitochondrial fluctuations

Two widely used microtubule-targeting chemicals called nocodazole and taxol (also known as paclitaxel) were applied to the C3H-10T1/2 cells. Nocodazole destabilizes microtubule polymerization (42). Destabilizing microtubules by nocodazole statistically significantly increases the creep compliance over the short timescales, yet the changes over long timescales are not significant (Figs. 3 A and S7 A). The distribution of directional change and the Pd of the nocodazole-treated cells show reduced persistent motion, especially over the longer timescales when compared with control cells (Figs. 3, B and C and S7 C). By destabilizing microtubules, nocodazole appears to increase the effective cage size, leading to an increase in creep compliance over short times. However, nocodazole inhibits the longer time directed motion. Because mitochondria are transported along microtubules, destabilizing microtubules very likely abrogates or impedes the active motion seen in control cells. Taxol inhibits the normal dynamic reorganization of the microtubule network and leads to the formation of extensive and hyperstable parallel arrays of microtubules (38, 39, 43). Taxol treatment leads to a statistically significant decrease of creep compliance over the long timescales, which becomes insignificant in the limit of short timescales (Fig. 3 A). A decrease in directional persistence is observed over timescales shorter than 5 s, and an increase is observed thereafter compared to control cells (Figs. 3, B and D and S7 C). Despite the increase in directional persistence, a twofold decrease in creep compliance was observed (Fig. S7 B). Taxol, therefore, strengthens the confinement of the mitochondria by the microtubule network and slows network dynamics, leading to a smaller creep compliance at longer times. However, even though the extent of motion is low, directed transport is even more apparent at longer timescales, probably due to the extensive microtubule network.

Figure 3.

Microtubule network plays a significant role in mitochondrial fluctuations. (A) Population mean creep compliances with SDs of control cells (n = 87), nocodazole-treated cells (n = 106), and taxol-treated cells (n = 131) are shown. Markers of different shapes and colors indicate population means, and the lines of the same colors are SDs. The short black line is a visual guide of slope one. (B–D) Distributions of directional change are shown at different lag times for control, nocodazole-treated, and taxol-treated cells, respectively. The dashed horizontal line indicates a uniform distribution that is characteristic of pure diffusion. To see this figure in color, go online.

Taken together, our results show that the microtubule network plays important roles in the mitochondrial fluctuations, probably by a dual-mechanism (Fig. 3). Over the short timescales, microtubules confine mitochondria to local “cages.” Over longer timescales, the mitochondria show a persistent drift, probably due to a combination of polymerization-depolymerization dynamics and active transport along the microtubule tracks. Destabilizing the cages using nocodazole increases the confinement volume of the mitochondria and thereby increases their creep compliances at short timescales but decreases the longer time persistent motion. Stabilizing the network using taxol leads to stronger confinement of the mitochondria and makes the longer-time drift slower and happen much later. These results also support the hypothesis that microtubule dynamics may contribute to the increase in creep compliance of ATP-depleted cells over long timescales. It is also possible that the inhibition of normal dynamics by taxol can result in a decrease in active forces generated by the uncorrelated dynamics of the microtubule network and lead to a decrease in the creep compliance. However, the increase in directional persistence after taxol treatment as compared with control cells implies that this mechanism is insignificant (Figs. 3, B and D and S7 C).

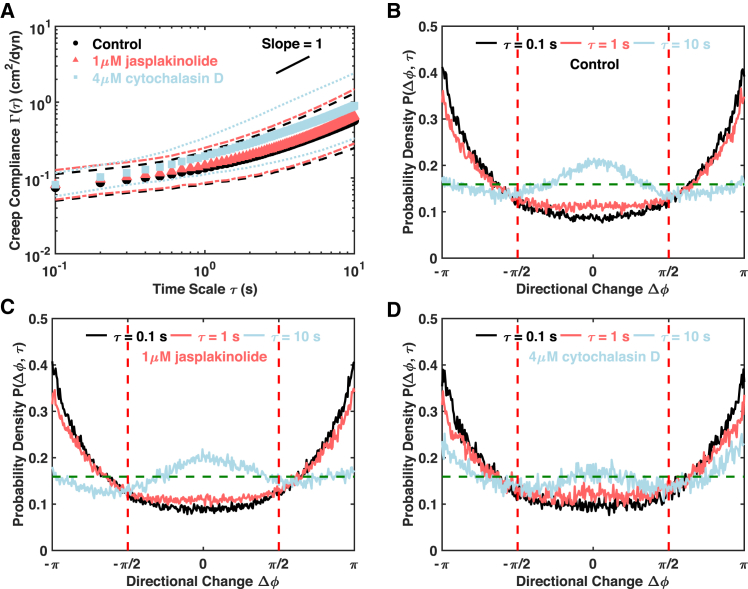

The actin network is required for active mitochondrial fluctuations in a myosin II independent manner

To test the roles played by the actin network on the mitochondrial fluctuations, the C3H-10T1/2 cells were treated with two widely used actin-targeting chemicals. Jasplakinolide is a potent inducer of actin polymerization and hyperstabilizes actin filaments (44). Jasplakinolide can be expected to increase mitochondrial confinement over short timescales and decrease the escape probability or reduce active fluctuations over longer timescales. Our data show that jasplakinolide leads to no statistically significant change at a high concentration of 1 μM in terms of both creep compliance and directional changes (Figs. 4, A–C and S8). Thus, stabilizing the actin network had no significant effect on mitochondrial fluctuations.

Figure 4.

Actin network is required for active mitochondrial fluctuations. (A) Population mean creep compliances with SDs of control cells (n = 98), jasplakinolide-treated cells (n = 141), and cytochalasin-D-treated cells (n = 44) are shown. Markers of different shapes and colors indicate population means, and the lines of the same colors are SDs. The short black line is a visual guide of slope one. (B–D) Distributions of directional change are shown at different lag times for control, jasplakinolide-treated, and cytochalasin-D-treated cells, respectively. The dashed horizontal line indicates a uniform distribution that is characteristic of pure diffusion. To see this figure in color, go online.

Cytochalasin D is a widely used inhibitor of actin dynamics that binds to the barbed ends of actin filaments and inhibits both actin polymerization and depolymerization (45, 46). Cytochalasin D has been shown to only inhibit the actin dynamics, and the net effects on the stability and density of the actin network depend on other cellular conditions (46). Therefore, cytochalasin D can specifically affect actin network dynamics as well as active driving forces generated by actin polymerization and depolymerization. Cytochalasin D statistically significantly increases the population mean creep compliance over both short and long timescales (Figs. 4 A and S8 A), which suggests a net increase in the confinement volume of the mitochondria, probably due to a reduction in the density of the actin network. However, the distributions of directional change suggest that the cytochalasin D made the confinement of the mitochondria last longer, with a significant peak at Δø = π even at the longest timescale of 10 s (Fig. 4 D). In addition, the decrease in persistent motion suggests that the actin network is also involved in active transport (Figs. 4, B and D). This is consistent with the report that the actin network could serve as tracks for active transportation over short length scales (37). Similar to earlier published studies (47), the microtubule and actin results suggest that the microtubule network is a primary local “cage” and that the actin network forms a secondary local cage, but both networks appear to be required for the active motion at long timescales.

We also tested the role of nonmuscle myosin II, which binds to the actin filaments and generates contractile forces on the actin network in an ATP-dependent manner. Myosin II had been shown to play important roles in driving active fluctuations of fluorescent particles in previous studies (3, 13, 14, 15, 16, 35, 48). We treated the C3H-10T1/2 cells with blebbistatin, which specifically binds to myosin II and inhibits its binding to actin filaments (49, 50, 51). However, our results with three different concentrations of blebbistatin show statistically insignificant changes in creep compliance (Fig. S9). Although minor decreases can be observed in the distributions of directional change (Fig. S9 D), especially in the 10 μM, this effect is small. Thus, in contrast to fluorescent particles that may become trapped in the actin network, the mitochondria are not dominantly affected by the dynamics of myosin II.

FSM using the control cells and ATP-depleted cells

To improve the accuracy of viscoelastic properties determined from ATP-depleted cells, we propose to use the distribution of directional change and Pd to make the selection of the timescales over which thermal forces are dominating. In our results, these two measurements suggest that the relevant thermally dominated timescales are up to 2 s in ATP-depleted cells (Figs. 2 B, S5 E and S6). In addition, comparing the MSDs and creep compliances of control and ATP-depleted cells shows that the population means converge at the shortest timescale, which is evidence that the ATP-depleting treatment has not altered the cytoskeleton structures in any significant way (3, 15, 16, 17).

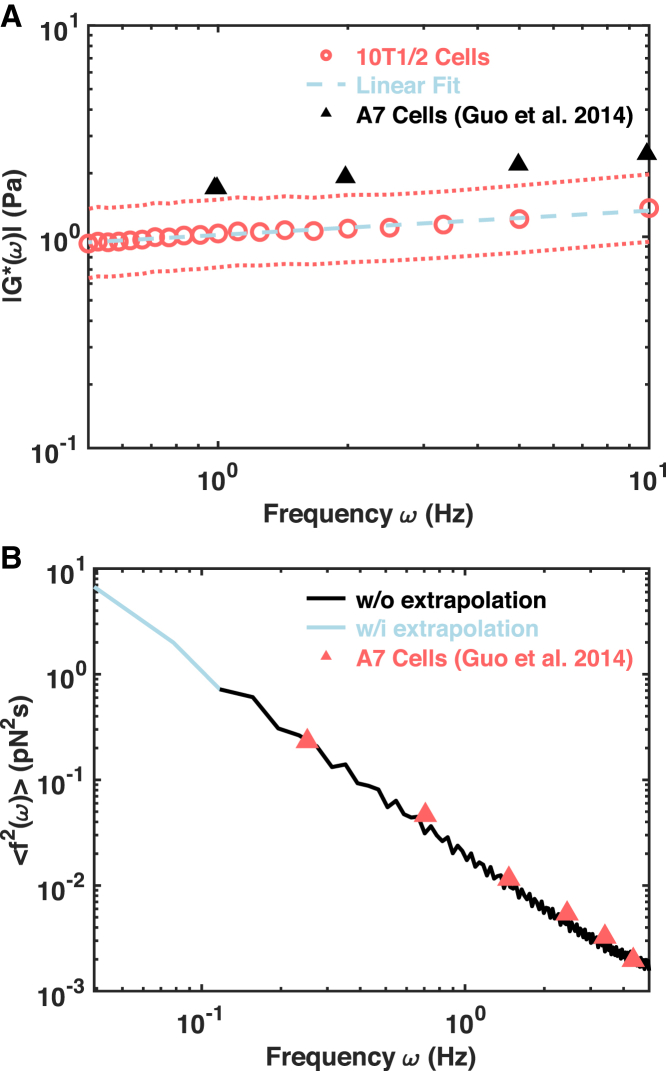

The power-law scaling factor over the timescales between 0.1 and 1 s has a mean of 0.15–0.2, which is consistent with reported values (17) and reminiscent of subdiffusive fluctuations in a nearly elastic medium (Figs. 2 A and S5, C and D). As in creep compliance, mitochondria after morphological filtering were used to determine the viscoelasticity to make sure the utilization of hydrodynamic radius is appropriate. The viscoelasticity determined using the MSDs of ATP-depleted cells under 2 s suggests that the elasticity modulus is indeed more than five times larger than the viscosity modulus (Fig. S10). The corresponding amplitude of the complex shear modulus (|G∗|) shows a temporal dependence following a power-law form with a scaling factor of 0.12 and an R2 value of 0.99 (Fig. 5 A). To test the validity of our result, we compared our values of |G∗| to those measured for A7 cells using active microrheology (a scaling factor of 0.16 and an R2 value of 0.99) (Fig. 5 A) in (3). Given the differences in cell lines, the two results are very similar and within a twofold difference, which supports the reliability of the alternative method we proposed.

Figure 5.

Mitochondrial-fluctuation-based force spectrum calculation. (A) A population mean complex shear modulus (open cycles) with SDs (dotted lines) determined from ATP-depleted cells is shown. The dashed line is a linear fit to the population mean. Black triangles indicate published measurements made on A7 cells using active microrheology (3). (B) The force spectrum is determined by combining the results from control cells and ATP-depleted cells using Eq. 4. Triangles indicate the published measurement of mitochondria using the original FSM (3). To see this figure in color, go online.

From the MSDs measured in the control cells, we calculated the corresponding Fourier transform of individual MSDs multiplied by the square of the corresponding mitochondrial hydrodynamic radius, as in Eq. 4. Finally, the force spectrum was calculated as the product of the effective spring constant determined from ATP-depleted cells and the displacement in control cells in frequency domain (Eq. 4; Fig. 5 B). We first calculated only the force spectrum over the timescales shorter than 2 s selected for ATP-depleted cells, as the black curve in Fig. 5 B. Because no obvious change in time dependence was observed for the |G∗| in the measured frequency range, we assumed linear frequency dependence for the whole frequency range covered in the MSD (3, 36) and calculated the force spectrum of the whole range, shown as the lighter curve in Fig. 5 B. Again, we compared our force spectrum results to that of mitochondrial fluctuation by the original FSM in (3). Surprisingly, our results are almost the same as those of the original FSM (Fig. 5 B) despite the differences between cell types and the differences in viscoelastic parameters.

Discussion

Spontaneous fluctuations of endogenous particles are valuable probes for measurement of intracellular mechanical properties

We show that a careful treatment of mitochondrial fluctuations along with chemical treatments, especially ATP depletion, can allow for estimation of intracellular mechanical properties. Our measurements show that the intracellular cytoskeletal network forms a weakly elastic microenvironment and that the |G∗| measured is well described by a power-law form with a scaling factor of 0.12 (Fig. 5 A). These results are consistent with those of previous studies in which spontaneously internalized fluorescent particles and vesicles were tracked (47, 52), which were probing similar mechanical microenvironments (53). Such a weak frequency dependence is also consistent with measurements made by not only active microrheology techniques (3, 54) but also other methods (including optical magnetic twisting cytometry, uniaxial stretching rheometer, and atomic force microscopy) (55, 56, 57) despite the different cell types (Table S2). The measured |G∗| in our ATP-depleted cells is ∼1 Pa, which is similar to the intracellular measurements (3, 54) and yet orders of magnitudes lower than that measured on the actin cortex (54, 55, 57). This supports the argument that the intracellular cytoskeletal network is mechanically distinct from cortical actin networks and is more dilute.

Our results also suggest that the weakly elastic microenvironment is liquidized by ATP-dependent processes. The ATP-dependent processes that exert forces on the mitochondria could arise from the polymerization-depolymerization dynamics of microtubules and actin as well as from motor-driven forces. Our data show that stabilizing the microtubule or actin network and thus repressing polymerization-depolymerization dynamics had no effect on the short-time fluctuations but intriguingly different effects at longer times. Although stabilizing actin did not significantly affect fluctuations at longer timescales, stabilizing microtubules decreased the extent of fluctuations but increased their persistence. Destabilizing microtubules increased the short-timescale fluctuations but had little effect at longer times, whereas destabilizing actin had no effect at shorter times but increased the extent of fluctuations at longer times. However, for both cases, the persistence of long-time motion was significantly reduced, which is consistent with the hypothesis that persistent motion is an effect of motor-driven transport on microtubule and actin tracks. Many published results have reported that contractile forces generated by myosin II play important roles in driving active fluctuations of fluorescent particles (3, 13, 14, 15, 16, 35, 48). However, myosin II was shown not to play a significant role in our study, which is also consistent with studies using spontaneously internalized fluorescent particles and vesicles (47, 52).

Although mitochondria can be actively transported to regions of the cell where they are required, their positioning at these regions has been shown to be mediated by protein anchors (58) that can tether them to the endoplasmic reticulum as well as the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton. Moreover, stationary mitochondria may also remain attached to the molecular motors responsible for transporting them to this location in the cell. The tethering may lead to the short timescale confined fluctuations observed in both the creep compliance and the directional persistence. The longer-timescale motion, which we show is ATP dependent, is probably associated with the movement of the tethers themselves because of remodeling of the cytoskeleton as well as motor-mediated movement, or both. The fact that destabilization of both actin and microtubules does not significantly increase the average creep compliance but decreases persistence suggests that the confinement probably involves other intracellular structures such as the endoplasmic reticulum, but active motion requires the cytoskeleton.

Active mitochondrial transport has been best studied in neurons because of its role in neurodegenerative diseases (59). Kinesin and dynein can move mitochondria toward the microtubule plus end and minus end, respectively, for a long distance. The actin network is more important for short-range transport and anchoring of mitochondria (37, 59). Myosins are responsible for moving mitochondria toward the actin filament plus end (e.g., myosin V) or minus end (e.g., myosin VI) (59). Mitochondria can also be completely released of these motor proteins and remain relatively stationary (59). We therefore hypothesize that the active forces driving mitochondrial fluctuations are generated by motor proteins like dynein, kinesin, and myosins other than myosin II (e.g., myosins V and VI).

The special nature of the confining environment of mitochondria is probably the reason why they are insensitive to the suppression of myosin-II-mediated actomyosin contractility. Passive polyethylene-glycol-coated probe particles may, in many cases, get confined by the actin meshwork and show significant sensitivity to the suppression of myosin II. Given the heterogeneity of the cytoskeletal network, mitochondrial fluctuations and fluorescent probe particles are very likely measuring cellular mechanical properties at different length scales and are possibly somewhat specialized to different components of the cytoskeleton. Future work is required to link the different aspects of the cellular cytoskeleton together, as measured by fluorescent particles as well as endogenous probes such as mitochondria as well as peroxisomes, lysosomes, and lipid vesicles (3, 52, 60).

Limitations of passive microrheology with mitochondria

Microrheology, whether active or passive, cannot provide information on the bulk rheology of the cell as a whole, which would require other assays. However, microrheology does provide insight into internal and local cytoplasmic properties, including the viscoelastic characteristics on which this study focuses. The alternative method we propose in this study has the advantages of noninvasiveness and low instrumentation requirements. However, like every technique, it also holds some limitations, some of which are shared by other particle-tracking-based methods. First, we used ensemble-averaging measurements, including MSD, creep compliance, and distribution of directional change, to characterize the mitochondrial fluctuations in this study. However, different mechanisms may dominate some specific timescales in particle motion rather than impact uniformly across all timescales, which would be obscured in the ensemble averaging. To gain deeper understanding about the underlying mechanisms, temporal analyses of individual trajectory become necessary. This field has seen rapid advances recently, including rolling-window-based methods (61) and hidden Markov-model-based methods (62). Although not included in this study, these temporal analyses will be incorporated in our future studies.

In this study, mitochondria were chosen as the probes due to their universal presence in different cell types and cellular states, yet the morphological complexity of the mitochondria may limit the applicability of this method in some cell types. As shown previously (23), the morphology of the mitochondrial network is dynamically regulated, mostly due to the important physiological roles played by mitochondria in cell biology. So the punctate mitochondria used in our study may not be abundant in some cell types. However, the fluctuating motion of intermediate and filamentous mitochondria could be included into the analysis to broaden future applications of this method. An automated classification scheme of mitochondrial morphology, like the one developed in (23), could be integrated into the analysis pipeline.

Although ATP depletion enables direct extraction of mechanical properties from passive microrheology measurements, it also poses some unique limitations. Each new cell type requires optimization of the ATP-depleting cocktail, and unintended effects may increase when different treatments are combined, for example, to measure the mechanical properties of taxol-treated cells. The treatment of ATP depletion may also introduce side effects to the “true” mechanical properties of the cytoplasm, for example, by increasing actin network density (63) and possibly by cross-linking actin filaments by inactive myosin II motors. To make sure that the side effect of the ATP depletion is not significant, the convergence on the short timescale was used in our study. Our results also showed that stabilizing the actin network does not affect the MSD of the mitochondria, suggesting that ATP-depletion side effects should be minimal in our results.

Finally, the use of microrheological techniques in living systems raises many questions that are yet to be settled and that are the subject of current research. The first overarching assumption is that the cellular cytoplasm can be treated as an isotropic continuous substance at the length scale of the probe particle. Another major assumption of the field is the use of the GSER to calculate the rheological parameters. This is an important assumption, and theoretical work has shown that the GSER is valid at best for a range of frequencies that, however, may span the physiologically relevant range for cell mechanics measurements (64, 65). The use of any type of probe particle also relies on the assumption that boundary conditions at the surface are not perturbing the results. Another important question is whether the results from the passive microrheology of ATP-depleted cells are equivalent to results from active microrheology. In particular, active microrheology using optical tweezers may be probing the nonlinear response of the cytoplasm, and theoretical articles have suggested that the nonlinear response may be strongly affected by local microstructures (65, 66, 67), though previous work has shown excellent consistency between active and passive microrheology (17). The existence of these debates is not only proof of the complexity of the cytoplasm but also an indication of the promise of microrheology in elucidating cytoplasmic properties, including but not confined to viscoelastic properties.

Noninvasive FSM

We extract the viscoelastic moduli G’ and G” using GSER in ATP-depleted cells by using a statistical test to identify thermally dominated timescales. Based on the distribution of directional change and the index of persistent motion, Pd, we identify a range of timescales over which thermal forces are dominating in the ATP-depleted cells. Even though this results in a smaller range of timescales to determine the viscoelastic properties from the ATP-depleted cells, we found that the accuracy is good compared to measurements made by active microrheology (3). We could then calculate the force spectrum based on the spontaneous fluctuations of mitochondria in control cells and the complex shear moduli measured in ATP-depleted cells. The resulting force spectrum is interestingly almost identical to the force spectrum of mitochondria measured previously (3). This relatively simple protocol should help expand the use and application of microrheology in living cells and may facilitate novel applications like measuring mechanics and motor-driven forces within cells in three-dimensional culture, in tissue models, and during embryonic development.

Author Contributions

W.X. and A.P. designed the research. W.X. performed the research. W.X. contributed analytic tools. W.X., E.A., and A.P. analyzed the data. W.X. and A.P. wrote the manuscript. All authors participated in editing, reading, and approving the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

W.X. and E.A. acknowledge the help of Dr. Keith DeLuca for cell culture and imaging protocols.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of National Science Foundation grant PHY-1151454.

Editor: Julie Biteen.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods, fourteen figures, and two tables are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(18)30570-8.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Orr A.W., Helmke B.P., Schwartz M.A. Mechanisms of mechanotransduction. Dev. Cell. 2006;10:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cross S.E., Jin Y.S., Gimzewski J.K. Nanomechanical analysis of cells from cancer patients. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007;2:780–783. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo M., Ehrlicher A.J., Weitz D.A. Probing the stochastic, motor-driven properties of the cytoplasm using force spectrum microscopy. Cell. 2014;158:822–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spill F., Reynolds D.S., Zaman M.H. Impact of the physical microenvironment on tumor progression and metastasis. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016;40:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniels B.R., Hale C.M., Wirtz D. Differences in the microrheology of human embryonic stem cells and human induced pluripotent stem cells. Biophys. J. 2010;99:3563–3570. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Earls J.K., Jin S., Ye K. Mechanobiology of human pluripotent stem cells. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2013;19:420–430. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2012.0641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brangwynne C.P., Koenderink G.H., Weitz D.A. Cytoplasmic diffusion: molecular motors mix it up. J. Cell Biol. 2008;183:583–587. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackintosh F.C., Schmidt C.F. Active cellular materials. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2010;22:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riedel C., Gabizon R., Bustamante C. The heat released during catalytic turnover enhances the diffusion of an enzyme. Nature. 2015;517:227–230. doi: 10.1038/nature14043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed W.W., Fodor É., Betz T. Active cell mechanics: measurement and theory. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1853:3083–3094. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fakhri N., Wessel A.D., Schmidt C.F. High-resolution mapping of intracellular fluctuations using carbon nanotubes. Science. 2014;344:1031–1035. doi: 10.1126/science.1250170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mizuno D., Head D.A., Schmidt C.F. Active and passive microrheology in equilibrium and nonequilibrium systems. Macromolecules. 2008;41:7194–7202. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lau A.W., Hoffman B.D., Lubensky T.C. Microrheology, stress fluctuations, and active behavior of living cells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003;91:198101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.198101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fodor É., Guo M., van Wijland F. Activity driven fluctuations in living cells. Biol. Phys. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mizuno D., Tardin C., Mackintosh F.C. Nonequilibrium mechanics of active cytoskeletal networks. Science. 2007;315:370–373. doi: 10.1126/science.1134404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smelser A.M., Macosko J.C., Holzwarth G. Mechanical properties of normal versus cancerous breast cells. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2015;14:1335–1347. doi: 10.1007/s10237-015-0677-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman B.D., Massiera G., Crocker J.C. The consensus mechanics of cultured mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:10259–10264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510348103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gal N., Lechtman-Goldstein D., Weihs D. Particle tracking in living cells: a review of the mean square displacement method and beyond. Rheol. Acta. 2013;52:425–443. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wirtz D. Particle-tracking microrheology of living cells: principles and applications. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2009;38:301–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mak M., Kamm R.D., Zaman M.H. Impact of dimensionality and network disruption on microrheology of cancer cells in 3D environments. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003959. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giampazolias E., Tait S.W. Mitochondria and the hallmarks of cancer. FEBS J. 2016;283:803–814. doi: 10.1111/febs.13603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.da Silva A.F., Mariotti F.R., Campello S. Mitochondria dynamism: of shape, transport and cell migration. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014;71:2313–2324. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1557-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giedt R.J., Fumene Feruglio P., Weissleder R. Computational imaging reveals mitochondrial morphology as a biomarker of cancer phenotype and drug response. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:32985. doi: 10.1038/srep32985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kandel J., Chou P., Eckmann D.M. Automated detection of whole-cell mitochondrial motility and its dependence on cytoarchitectural integrity. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2015;112:1395–1405. doi: 10.1002/bit.25563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giedt R.J., Pfeiffer D.R., Alevriadou B.R. Mitochondrial dynamics and motility inside living vascular endothelial cells: role of bioenergetics. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2012;40:1903–1916. doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0568-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu J., Viasnoff V., Wirtz D. Compliance of actin filament networks measured by particle-tracking microrheology and diffusing wave spectroscopy. Rheol. Acta. 1998;37:387–398. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mason T., Ganesan K., Kuo S. Particle tracking microrheology of complex fluids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997;79:3282–3285. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burov S., Tabei S.M., Dinner A.R. Distribution of directional change as a signature of complex dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:19689–19694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319473110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saxton M.J. Single-particle tracking: the distribution of diffusion coefficients. Biophys. J. 1997;72:1744–1753. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78820-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grebenkov D.S. Probability distribution of the time-averaged mean-square displacement of a Gaussian process. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2011;84:031124. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.84.031124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gibbons J.D., Chakraborti S. Chapman & Hall/Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton, FL: 2011. Nonparametric Statistical Inference. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hollander M., Wolfe D.A., Chicken E. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2013. Nonparametric Statistical Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perrin F. Mouvement brownien d’un ellipsoide - I. Dispersion diélectrique pour des molécules ellipsoidales. J. Phys. Radium. 1934;5:497–511. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perrin F. Mouvement Brownien d’un ellipsoide (II). Rotation libre et dépolarisation des fluorescences. Translation et diffusion de molécules ellipsoidales. J. Phys. Radium. 1936;7:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gallet F., Arcizet D., Richert A. Power spectrum of out-of-equilibrium forces in living cells: amplitude and frequency dependence. Soft Matter. 2009;5:2947–2953. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta S.K., Guo M. Equilibrium and out-of-equilibrium mechanics of living mammalian cytoplasm. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 2017;107:284–293. [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacAskill A.F., Kittler J.T. Control of mitochondrial transport and localization in neurons. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horwitz S.B. Taxol (paclitaxel): mechanisms of action. Ann. Oncol. 1994;5(Suppl 6):S3–S6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kingston D.G. Tubulin-interactive natural products as anticancer agents. J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72:507–515. doi: 10.1021/np800568j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ishikawa T., Zhu B.L., Maeda H. Effect of sodium azide on the metabolic activity of cultured fetal cells. Toxicol. Ind. Health. 2006;22:337–341. doi: 10.1177/0748233706071737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wick A.N., Drury D.R., Wolfe J.B. Localization of the primary metabolic block produced by 2-deoxyglucose. J. Biol. Chem. 1957;224:963–969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vasquez R.J., Howell B., Cassimeris L. Nanomolar concentrations of nocodazole alter microtubule dynamic instability in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1997;8:973–985. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.6.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schiff P.B., Fant J., Horwitz S.B. Promotion of microtubule assembly in vitro by taxol. Nature. 1979;277:665–667. doi: 10.1038/277665a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spector I., Braet F., Bubb M.R. New anti-actin drugs in the study of the organization and function of the actin cytoskeleton. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1999;47:18–37. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19991001)47:1<18::AID-JEMT3>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cooper J.A. Effects of cytochalasin and phalloidin on actin. J. Cell Biol. 1987;105:1473–1478. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.4.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shoji K., Ohashi K., Mizuno K. Cytochalasin D acts as an inhibitor of the actin-cofilin interaction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012;424:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hendricks A.G., Holzbaur E.L., Goldman Y.E. Force measurements on cargoes in living cells reveal collective dynamics of microtubule motors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:18447–18452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215462109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MacKintosh F.C., Levine A.J. Nonequilibrium mechanics and dynamics of motor-activated gels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100:018104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.018104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shu S., Liu X., Korn E.D. Blebbistatin and blebbistatin-inactivated myosin II inhibit myosin II-independent processes in Dictyostelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:1472–1477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409528102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kovács M., Tóth J., Sellers J.R. Mechanism of blebbistatin inhibition of myosin II. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:35557–35563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramamurthy B., Yengo C.M., Sweeney H.L. Kinetic mechanism of blebbistatin inhibition of nonmuscle myosin IIb. Biochemistry. 2004;43:14832–14839. doi: 10.1021/bi0490284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldstein D., Elhanan T., Weihs D. Origin of active transport in breast-cancer cells. Soft Matter. 2013;9:7167–7173. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu P.H., Hale C.M., Wirtz D. High-throughput ballistic injection nanorheology to measure cell mechanics. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:155–170. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo M., Ehrlicher A.J., Weitz D.A. The role of vimentin intermediate filaments in cortical and cytoplasmic mechanics. Biophys. J. 2013;105:1562–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fabry B., Maksym G.N., Fredberg J.J. Scaling the microrheology of living cells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001;87:148102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.148102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Desprat N., Richert A., Asnacios A. Creep function of a single living cell. Biophys. J. 2005;88:2224–2233. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.050278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alcaraz J., Buscemi L., Navajas D. Microrheology of human lung epithelial cells measured by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 2003;84:2071–2079. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75014-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kraft L.M., Lackner L.L. Mitochondrial anchors: positioning mitochondria and more. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018;500:2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.06.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saxton W.M., Hollenbeck P.J. The axonal transport of mitochondria. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:2095–2104. doi: 10.1242/jcs.053850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gal N., Weihs D. Intracellular mechanics and activity of breast cancer cells correlate with metastatic potential. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2012;63:199–209. doi: 10.1007/s12013-012-9356-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arcizet D., Meier B., Heinrich D. Temporal analysis of active and passive transport in living cells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;101:248103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.248103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Monnier N., Barry Z., Bathe M. Inferring transient particle transport dynamics in live cells. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:838–840. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Atkinson S.J., Hosford M.A., Molitoris B.A. Mechanism of actin polymerization in cellular ATP depletion. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:5194–5199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levine A.J., Lubensky T.C. One- and two-particle microrheology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000;85:1774–1777. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Squires T.M., Mason T.G. Fluid mechanics of microrheology. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2010;42:413–438. [Google Scholar]

- 66.DePuit R.J., Khair A.S., Squires T.M. A theoretical bridge between linear and nonlinear microrheology. Phys. Fluids. 2011;23:063102. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Puertas A.M., Voigtmann T. Microrheology of colloidal systems. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2014;26:243101. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/26/24/243101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.