Abstract

Previous studies have shown greater fluorophore uptake during electroporation on the anode-facing side of the cell than on the cathode-facing side. Based on these observations, we hypothesized that hyperpolarizing a cell before electroporation would decrease the requisite pulsed electric field intensity for electroporation outcomes, thereby yielding a higher probability of reversible electroporation at lower electric field strengths and a higher probability of irreversible electroporation (IRE) at higher electric field strengths. In this study, we tested this hypothesis by hyperpolarizing HL-60 cells using ionomycin before electroporation. These cells were then electroporated in a solution containing propidium iodide, a membrane integrity indicator. After 20 min, we added trypan blue to identify IRE cells. Our results showed that hyperpolarizing cells before electroporation alters the pulsed electric field intensity thresholds for reversible electroporation and IRE, allowing for greater control and selectivity of electroporation outcomes.

Introduction

A pulsed electric field (PEF) applied across a cell membrane causes positive and negative charges to accumulate at opposite sides of the membrane, increasing the transmembrane voltage (1). If sufficient charge accumulates for a long enough time, pores will open in the cell membrane (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). This phenomenon is referred to as electroporation (3, 4, 5). There are three potential outcomes of electroporation. It can cause irreparable damage to the cell membrane resulting in cell death. This outcome is denoted as irreversible electroporation (IRE) (3, 4, 5). Alternatively, the pores generated during electroporation may close after a short delay, allowing the cell to remain viable (6)—an outcome known as reversible electroporation (RE) (3, 4, 5). A third possible outcome of PEF exposure occurs when the energy delivered is insufficient to open a significant number of pores or the pores opened are of negligible size. Cells under this condition are considered nonelectroporated (NEP) (3, 4, 5).

IRE and RE both have important clinical applications. IRE shows promise as a nonthermal technique for ablating tissue (7, 8, 9). In contrast to thermal ablation techniques such as radio-frequency ablation, IRE-based ablation is not impeded by the heat-sink effects of nearby veins and arteries (7, 8, 9, 10, 11). Additionally, it leaves the extracellular matrix intact (9, 12) and avoids an inflammatory response (13). It is also useful because of its short treatment time compared to radio-frequency ablation and cryosurgery (14). RE is a promising technique for delivering macromolecules such as proteins, DNA, RNA (5, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20), antibodies (21), and nanoparticles (22, 23) into a cell’s cytoplasm. In contrast to viral delivery techniques, RE does not invoke an immune response and can transfect larger DNA molecules (24, 25, 26, 27). One limitation of current RE procedures is the relatively low survival rate of the treated cells (25, 27). Improving cell viability will make RE more attractive for therapeutic applications involving the insertion of DNA, proteins, enzymes, or drugs into cells (28, 29).

There is interest in developing methods that increase the probability of RE or IRE depending on pulse parameters. In this study, we are focusing on a potential method that exploits manipulating the transmembrane potential across cell’s plasma membrane before electroporation. Previous studies have indicated a correlation between transmembrane electric potential and pore creation. One of the earliest studies reported the discovery that more fluorophores entered the cell through the membrane facing the positive electrode (anode) than through the opposing side (30). The inner portion of cells are normally negatively charged, which is balanced by charges on the external face of the plasma membrane from protons or cations, resulting in a natural anion-membrane-cation transmembrane potential (31, 32). This naturally occurring phenomenon has been attributed to the increase in pore formation near the anode (30, 33). This suggests that altering the transmembrane potential before electroporation could decrease the applied PEF threshold for electroporation and increase the probability of RE or IRE depending on pulse parameters. Kennedy et al. demonstrated that cationic peptides could be used to increase the cytoplasmic transmembrane voltage (resulting in membrane hyperpolarization) and reduce the threshold for IRE (3). However, the cationic peptides used in that study have a high toxicity and are therefore not good candidates for RE applications.

Transmembrane voltage can also be regulated by the concentration of ions and their permeability inside and outside the cell (34). The ions with the strongest effect on transmembrane potential are potassium (K+), sodium (Na+), and chloride (Cl−). Changing the concentration of ions outside the cell or activating ion pumps within the cell membrane alters the transmembrane potential. For example, Brent et al. showed that HL-60 cells exposed to the drug ionomycin, a Ca2+ ionophore, underwent membrane hyperpolarization for several minutes (35). This group observed a similar effect using ATP, with a shorter duration (35). They did not report any toxic effects from either method over the 7-day duration of their experiments, suggesting that low concentrations of ionomycin or ATP are nontoxic to HL-60 cells.

We present a comprehensive study designed to test the hypothesis that hyperpolarizing cell membranes before electroporation reduces electroporation PEF thresholds and increases electroporation outcome efficiencies. We specifically hypothesized that decreasing the threshold for electroporation would make conditions for RE more favorable at lower PEF intensities and therefore improve the ratio of RE to IRE cells in a sample, whereas at higher PEF intensities, decreasing the threshold would cause more membrane damage to occur, thereby increasing IRE outcomes without increasing the externally applied PEF intensity. Membrane hyperpolarization of HL-60 cells was achieved using ionomycin. We elected to model our experimental results with cubic-spline data fit models in anticipation of nonlinear relationships between PEF intensity or pulse duration and the three possible outcomes. An interaction between ionomycin and PEF or pulse duration was also allowed in the models. Significant effects were determined using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) procedure. We observed significant increases in RE for shorter pulse durations and lower PEF intensities and increases of IRE for all higher PEF intensities. This suggests that RE is effectively achieved over a select window of pulse durations, whereas IRE performance is pulse-duration independent.

Materials and Methods

Cell preparation, electroporation protocols, and design

HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were used for all experiments, because their spherical shape eliminates the dependency of the electroporation outcome on the cell’s orientation relative to the electric field. HL-60 cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in RPMI-1640 containing 2% glutamine supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2% penicillin and streptomycin. Propidium iodide (PI) (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) and trypan blue (TB) (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) were used as membrane-integrity indicators. PI is visible using fluorescence microscopy, fluorescing after it enters a cell. TB is visible using bright-field microscopy, staining cells with compromised membranes.

At least 1 day before conducting experiments, slides were treated with a poly-L-lysine adhesion coating (Sigma-Aldrich, Madison, WI) and then allowed to dry. Immediately before experimentation, a sample of cells was counted, using TB to distinguish between live and dead cells. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) without phenol red, calcium, or magnesium, containing 5.3 mM KCl, 0.44 mM KH2PO4, 4.17 mM NaHCO3, 137.93 mM NaCl, 0.34 mM Na2HPO4, and 5.56 mM D-glucose (dextrose) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) (1.42 S/m conductivity) at a concentration of 2 million cells per milliliter. The cell count was used to quantify the percentage of dead cells at the beginning of each trial. An equal quantity of 60 μM PI solution (Fisher Scientific International, Pittsburgh, PA) (dissolved in HBSS) was added to the cell/HBSS mixture, resulting in a final PI concentration of 30 μM. For the treatment group (HBSS + ionomycin experiments), the control solution (PI + HBSS) was supplemented with 100 nM ionomycin (Fisher Scientific). After addition of PI (and ionomycin when applicable), cells were incubated for 10 min at 37°C and 5% CO2. After incubation, ionomycin was added again to the HBSS + PI + ionomycin samples, because under these conditions, the effects of the ionomycin on the transmembrane electric potential started to diminish after approximately 10 min. To estimate causal effects of hyperpolarization on electroporation outcome, we randomized samples of cells to treatment and control levels.

A BTX Model ECM 830 Square Wave Electroporation System (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) was used to deliver the PEF. The PEF was delivered to cells in an electroporation cuvette with a 2.0 mm gap between parallel plate electrodes. Square monopolar pulses with voltages up to 1.5 kV were used for this study. Pulse durations ranged from 20 to 100 μs. After electroporation, cells remained in the cuvettes undisturbed for 20 min to allow transient pores to close. We selected the 20 min interval based on the understanding that pore resealing in RE cells typically lasts up to a few minutes (5, 6, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41); hence, a 20 min interval allows sufficient time for transient pores to close.

TB was added 20 min after electroporation. Two minutes after TB addition, 13 μL of the cell/HBSS/PI mixture was then placed onto a poly-L-lysine-coated slide with a nylon washer placed in the middle to form a well for the cells. The cells were allowed to settle on the slide for 5 min, after which bright-field and fluorescence images were taken. PI fluorescence was monitored using fluorescence microscopy at 535 nm excitation and 617 nm emission. A Lambda DG-4 excitation lamp and high-speed wavelength switcher (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA) was used to excite the PI. Control of the lamp and CCD camera were done with custom software (Prairie Technologies, Madison, WI). A Nikon Eclipse TE200 microscope (Nikon USA, Melville, NY) equipped with a Hamamatsu C4742-95 Digital charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Bridgewater, NJ) was used to capture all images taken in this study. A timeline of the experimental procedure is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Timeline of Experimental Procedure

| Time | Task |

|---|---|

| Prep | At least 1 day before the start of the experiment, prepare poly-L-lysine coated slides. |

| 0 min | Count cells to determine the percent living. Place cells into centrifuge tube. Centrifuge until pellet forms. Re-suspend cells in HBSS at a concentration of 2 million cells per milliliter. Mix with equal parts of 2× (60 μm) PI solution. Add ionomycin for ionomycin + HBSS experiments. Incubate for 10 min. |

| 10 min | Add second dose of ionomycin for the ionomycin + HBSS experiments. Place 200 μL of cell/electroporation medium mixture into a 2 mm cuvette. Electroporate cells. Leave cells undisturbed for 20 min. |

| 30 min | Add 2 μL of TB to the cuvette. |

| 32 min | Place 13 μL of cells on slide inside the nylon washer. |

| 37 min | Take snapshots of bright-field and fluorescence images. |

We performed three sets of experiments. The first was fixing the pulse duration at 40 μs and varying the amplitude of the PEF from 0 to 7.5 kV/cm. We chose the 40-μs pulse duration because previous work in our lab had determined it is well suited for RE in HL-60 cells (unpublished data). We then repeated the experiments at a pulse duration of 100 μs, which was chosen because it is commonly used for IRE applications (14, 42, 43, 44). Lastly, we fixed the PEF amplitude at 2.06 kV/cm (which is approximately at which the peak percentage of RE was previously observed) and varied the pulse duration from 20 to 100 μs to investigate the range of pulse durations that are effective for increasing RE.

Transmembrane potential measurements

The transmembrane potential was measured using the potential-sensitive dye DiBAC4(3). We created a calibration curve to establish a direct relationship between the internalized concentration of DiBAC4(3) and the respective measured fluorescence intensity. We then used this relationship to determine the concentration of DiBAC4(3) within any cell of interest. The transmembrane potential was calculated using the Nernst equation (Eq. 1) with the fluorescence-determined intracellular dye concentration and the known extracellular dye concentration:

| (1) |

where R is the universal gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, F is the Faraday constant, Di is the concentration of DiBAC4(3) internalized by the cell, and De is the external concentration of DiBAC4(3).

The calibration curve was created by depolarizing cells with 0.5 μg/mL gramicidin (Fisher Scientific) (45) and incubating with various concentrations of DiBAC4(3) (Fisher Scientific) ranging from 1 to 15 μM. This depolarization caused the intracellular and extracellular DiBAC4(3) concentrations to be equal. The cells were incubated for 30 min after the addition of DiBAC4(3) and gramicidin. After incubation, the fluorescence of DiBAC4(3) was then sampled using the same microscope setup as described in Cell Preparation, Electroporation Protocols, and Design, using a 470 nm excitation/525 nm emission filter cube with an exposure time of 750 ms. The calibration experiments were run three times, and the internal fluorescence was calculated using MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA); thus, we were able to establish a relationship between the amount of DiBAC4(3) internalized to fluorescence intensity. Using this curve, shown in Fig. S1, we were able to calculate the concentration of DiBAC4(3) internalized for an unknown sample by measuring its fluorescence intensity. Each experiment was run as a pair of one control and one hyperpolarized, and the difference was recorded to minimize the effects of day-to-day variation. This provided improved accuracy over averaging across all recorded values. The transmembrane potential was then calculated using Eq. 1. Finally, the calibration measurements were replicated using a 10-min incubation period after addition of DiBAC4(3) and gramicidin. The results of the 10-min incubation time protocol matched the results of the 30-min incubation protocol, confirming the accuracy of calibrations and confirming that a 10-min incubation protocol was sufficient for our purposes.

When measuring the effects of ionomycin on transmembrane potential, the same (10-min) procedure was followed as described above, except no gramicidin was used, 11 μM DiBAC4(3) solution was used, and the cells were incubated in HBSS plus 0.1 μM ionomycin solution. Additional ionomycin was also added immediately after incubation to match the conditions of the electroporation experiments.

Throughout the duration of the electroporation experiments, a sample of the cells was periodically tested with 11 μM DiBAC4(3) solution to confirm that ionomycin was continuing to affect the transmembrane potential. Any experiments that were tested that resulted in negligible change in the transmembrane potential were discarded, and new ionomycin was used. The measured change in transmembrane potential across all (kept) experiments was 13.2 ± 6.1 mV (more negative).

DiBAC4(3) was also used to determine the time response of ionomycin by collecting snapshots over the course of 30 min after ionomycin addition. The transmembrane potential effects of 100 nM ionomycin wore off between 10 and 15 min. However, if ionomycin was added again after 10 min, the effects lasted much longer (>20 min). Additionally, it took 5–10 min for the cells to adjust their transmembrane potential after HBSS was added. Taking these both into account, we chose to incubate the cells in HBSS (or HBSS + ionomycin) for 10 min before applying the PEF and to add a second dose of ionomycin approximately 1 min before applying the PEF.

Analysis method

PI and TB were used to distinguish between NEP, RE, and IRE outcomes. PI is normally a membrane-impermeable molecule that binds to intracellular nucleic acids when it crosses the cell membrane (either through electroporation or cell death), causing a significant increase in fluorescence. Thus, PI fluorescence is only detectable once the molecule has passed through the plasma membrane. TB stains any cells with compromised membranes, and thus, when it is added after reversible pores have had time to close, only stains IRE cells. TB is detectable using standard bright-field microscopy. Cells that internalized both TB and PI were counted as IRE, cells that internalized PI but excluded TB were counted as RE, and cells that excluded both TB and PI were counted as NEP. Cells that were dead before electroporation also internalize PI and TB and thus appear as false positive IRE cells with this method. To account for this, we determined the live/dead ratio of the samples immediately before electroporation and adjusted the IRE counts accordingly so the reported numbers reflect what happened to the living cells.

The center of each cell was identified using the bright-field images acquired during the procedure. A representative bright-field image is shown in Fig. 1 a. We also used the bright-field images to visually determine TB internalization.

Figure 1.

A representative bright-field and fluorescence image illustrating the analysis method used in this study. PI fluorescence intensity inside each cell was determined by comparing an area inside of the cell to three nearby points external to the cell (marked with x). Cells internalizing both TB and PI were considered IRE (cells 1–5), cells internalizing only PI were considered RE (6, 8, 11, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 25), and cells excluding both membrane integrity indicators were considered NEP (cells 7, 9, 10, 12, 13, 21, 23, 24, 26–28). (a) is the bright-field image and (b) is the fluorescence image. The scale bar represents 20 μm.

To distinguish between fluorescing and nonfluorescing cells, we used MATLAB (The MathWorks) to quantitatively analyze the fluorescence images by comparing each cell’s internal fluorescence intensity to several local luminescent intensities external to the individual cell. The fluorescence intensity inside the cell was measured near the center of the cell. This was compared to the average external luminescence intensity, determined by sampling the background near to the cell. To measure the background fluorescence, we sampled three external regions approximately evenly spaced around the cell. In preliminary trials, we found that using fewer than three regions created too much sensitivity in the determination of whether a cell was classified as fluorescing to the specific location of the regions (particularly near bright cells that had a visible corona surrounding them). Using more than three regions did not result in any notable benefit. The cell was determined to be fluorescing if the average measured internal fluorescence value exceeded a threshold of T times the average value of the surrounding background luminescence intensities. Unpublished work in our lab determined that, for our setup, T equal to 1.125 gave the highest accuracy (least number of false negatives and positives). We present a representative fluorescence image in Fig. 1 b.

Statistical analysis

In the 40- and 100-μs experiments described in Cell Preparation, Electroporation Protocols, and Design, we implemented a cubic-splines regression using the lm package in R (46) to estimate effects on the electroporation outcome. We modeled the treatment effect of hyperpolarization with ionomycin as linear. The effect of PEF intensity and its interaction with treatment were modeled using a nonlinear cubic-spline regression generated using the ns function in R (46). We chose cubic splines because they allow for the incorporation of nonlinear effects with more than one point of inflection using a relatively small number of parameters (47, 48). Knots were chosen to reflect known underlying trends in the results (49). Specifically, we expected the primary electroporation outcome to change depending on the applied PEF intensity. At low PEF intensity, NEP was expected to be the dominant term, followed by a region in which RE is dominant, then IRE. We selected knots to be in transition areas to allow for the best representation of the data. Prior findings establish that this approach is best for describing the expected nonlinear biological dependence of electroporation type on field strength (49, 50, 51). Specifically, the biological mechanisms that rule this relationship are highly nonlinear (52), justifying the use of splines. The interaction term was included to explore the hypothesis that the effects of membrane hyperpolarization using ionomycin would vary depending on PEF intensity. The significance of effects was determined using ANOVA. Interaction effects that were not deemed significant (meaning the effect of PEF intensity was not significantly different for different levels of ionomycin) were excluded from the model. Three separate regressions were performed, one for each possible outcome as a percent of cells (i.e., percent NEP, RE, or IRE). In the experiments in which we fixed PEF at a constant value and varied the pulse duration, the statistical model was fitted similar to the one described above but substituting PEF intensity with pulse duration. In our analysis, we considered p < 0.05 as significant. We calculated means and standard error for all combinations of treatment and PEF, shown in the figures.

Viability studies

We investigated whether the experimental conditions were toxic to cells by performing live/dead counts on groups of cells in both the control group (HBSS/PI solution) and the treatment group (HBSS/PI/ionomycin solution). For both cases, we did not detect any decrease in cell viability within the first 2 h. The treatment group resulted in 1.11 ± 0.59% SD dead, whereas the control resulted in 1.72 ± 0.65% SD. This resulted in p = 0.1508, and therefore we concluded that the percentage of dead cells is not significantly different between the two groups.

Cells in the control group did not show any increase in cell death during the 2-h duration of the experiment. At the working concentration of ionomycin, cells in the treatment group did not show any change in cell viability over the course of 2 h. Live/dead counts were comparable to cells incubated in HBSS without ionomycin at each time point sampled during the 2 h.

However, cells incubated in a solution with double the working concentration of ionomycin (i.e., 200 nM ionomycin, added at t = 0 and t = 10 min) for 2 h resulted in a twofold increase in cell death and lower proliferation rate of about half when compared to cells incubated for the same amount of time in HBSS. These samples were then washed, and the cells that were exposed to ionomycin proliferated normally (doubling approximately every 24 h) once the ionomycin was removed.

Results

40-μs results

Cells were electroporated at ∼200–1500 V in cuvettes with a gap size of 2.0 mm. When using these cuvettes, any voltage higher than 1500 V resulted in an arc (with HBSS as the medium). Therefore, we did not perform experiments at higher voltages. All electric field strengths (PEF intensities) were calculated from the applied voltage and gap size and therefore are reported in kV/cm, calculated by dividing the gap voltage by the gap spacing of 2.0 mm. The PEF intensities for the 40-μs experiments ranged from 0 to 7.5 kV/cm. We took a minimum of 14 samples at each voltage setting. These results are shown in Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5.

Figure 2.

Percentage of sample determined to be electroporated (EP) with a 40-μs pulse duration. The control group was EP in HBSS, and the treatment group was EP in HBSS supplemented with 100 nM ionomycin. The average values of each sampled PEF intensity are depicted by “o” for control and “∗” for treatment. The error bars represent a 95% confidence interval. PEF intensities of 1.8 and 2.0 kV/cm resulted in significant differences in the percent of EP cells. Regression lines represent the fitted cubic splines.

Figure 3.

Percentage of sample determined to be RE with a 40-μs pulse duration. The control group was EP in HBSS, and the treatment group was EP in HBSS supplemented with 100 nM ionomycin. The average values of each sampled PEF intensity are depicted by “o” for control and “∗” for treatment. The error bars represent a 95% confidence interval. PEF intensities of 1.8 and 2.0 kV/cm resulted in significant increase in the percent of RE cells in the treatment samples, whereas at 6.0 and 6.9 kV/cm, we found a statistically significant reduction in RE in the treatment samples. Regression lines represent the fitted cubic splines.

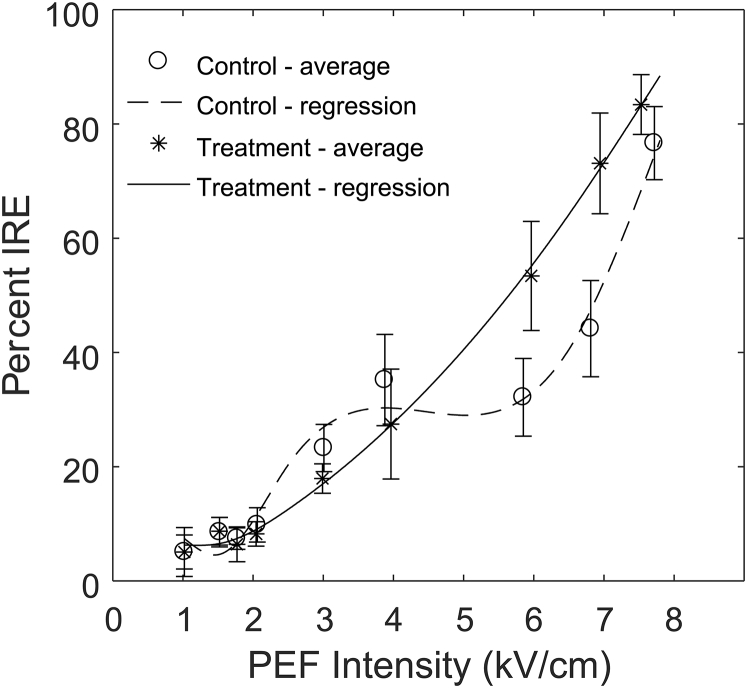

Figure 4.

Percentage of sample determined to be IRE with a 40-μs pulse duration. The control group was EP in HBSS, and the treatment group was EP in HBSS supplemented with 100 nM ionomycin. The average values of each sampled PEF intensity are depicted by “o” for control and “∗” for treatment. The error bars represent a 95% confidence interval. PEF intensities of 6.0 and 6.9 kV/cm resulted in a statistically significant increase in IRE in the treatment samples. Regression lines represent the fitted cubic splines.

Figure 5.

Percentage of sample determined to be EP with a 100-μs pulse duration. The control group was EP in HBSS, and the treatment group was EP in HBSS supplemented with 100 nM ionomycin. The average values of each sampled PEF intensity are depicted by “o” for control and “∗” for treatment. The error bars represent a 95% confidence interval. No PEF intensities resulted in a significant difference in the percent of electroporated cells. Regression lines represent the fitted cubic splines.

At low PEF intensities (1.8, 2.0, and 3.0 kV/cm), the addition of ionomycin significantly increased the percentage of RE cells while decreasing the number of NEP cells. The peak RE percentage increased from 57.5% ± 17.7 SD at 3 kV/cm to 71.85% ± 11.7 SD at 2 kV/cm. It is worth noting that the window of PEF intensities that attain close to peak RE decreased for the hyperpolarized cells. The hyperpolarized cells are close to the peak RE percentage in the range of 1.77–4 kV/cm, whereas the control cells’ peak RE range is 2–7 kV/cm. Here, we define close as overlapping 95% confidence intervals. At higher PEF intensities (6.0 and 6.9 kV/cm), the addition of ionomycin significantly increased the percentage of IRE cells while decreasing the number of RE cells.

We analyzed the results for the 40-μs pulse durations using a cubic-spline regression with three knots, located at 1.5, 2.5, and 6.5 kV/cm. These results are shown in the next three sections.

NEP regression results

Results from the regression analysis for NEP outcomes indicated that the direct effect of treatment with ionomycin, PEF intensity, and the interaction between treatment and PEF intensity were significant, meaning they all resulted in statistically significant changes in electroporation percentage. The significance of the interaction term between the electroporation spline and treatment means the effects of ionomycin change depending on the PEF intensity. This is specifically seen in the 1.75–3 kV/cm range. The results of the regression are shown in Fig. 2 (fitted lines) and Table 2. We flipped the NEP results to show the percent electroporated in Fig. 2. Results confirm that hyperpolarizing the cellular membrane decreased NEP and therefore increased the chances for electroporation at certain ranges of PEF intensities with 40-μs pulse durations.

Table 2.

40-μs NEP Regression ANOVA Results

| Degrees of Freedom | Sum of Squares | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | 1 | 2279 | <0.0001 |

| Spline of PEF | 4 | 181,169 | <0.0001 |

| Interaction | 4 | 2751 | 0.0003 |

RE regression results

Results from the regression analysis for RE outcomes indicated that the direct effect of treatment with ionomycin was not significant for the electroporation outcome. But both the effect of PEF intensity and the interaction between treatment and PEF intensity were. This suggests, respectively, that PEF intensity has an effect on electroporation outcome and that hyperpolarizing the cellular membrane changed RE outcomes differently depending on the PEF intensity (i.e., interaction). Specifically, hyperpolarizing the membrane increased the chances for RE at lower PEF intensities and decreased the chances for RE at higher PEF intensities using 40-μs pulse durations. This increase in RE was observed for a smaller range of PEF intensities in the hyperpolarized case (1.75–3 kV/cm, with between 62.3 and 71.9% fluorescing), whereas a more constant effect across PEF intensities was observed for non-hyperpolarized membranes, as seen in the window between 2 and 7 kV/cm (with between 42.7 and 57.4% fluorescing). The results of the regression are shown in Fig. 3 (fitted lines) and Table 3. We flipped the NEP results to show the percent electroporated in Fig. 3. No departures of normality or heterogeneity of variances were found in the residual and variance check.

Table 3.

40-μs RE Regression ANOVA Results

| Degrees of Freedom | Sum of Squares | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | 1 | 364 | 0.1780 |

| Spline of PEF | 4 | 108,475 | <0.0001 |

| Interaction | 4 | 16,422 | <0.0001 |

IRE regression results

Results from the regression analysis for IRE outcomes indicated that the direct effect of treatment with ionomycin, PEF intensity, and the interaction between treatment and PEF intensity were significant, meaning they all resulted in statistically significant changes in electroporation percentage. Results of the regression are shown in Fig. 4 and Table 4. Results suggest that hyperpolarizing the cellular membrane changed IRE outcomes differently depending on the PEF intensity. Specifically, hyperpolarizing the membrane increased the chances for IRE at higher PEF intensities using 40-μs pulse durations when compared to the control. We observed a slight increase in the regression for the control compared to the treatment at around 3 kV/cm; however, this is not significant, as visualized by the overlapping 95% confidence interval bars.

Table 4.

40-μs IRE Regression ANOVA Results

| Degrees of Freedom | Sum of Squares | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | 1 | 849 | 0.0036 |

| Spline of PEF | 4 | 174,216 | <0.0001 |

| Interaction | 4 | 7858 | <0.0001 |

100-μs results

We performed the second set of experiments using 100-μs pulse durations. Cells were electroporated at ∼0–1150 V in cuvettes with a gap size of 2.0 mm. The longer pulses resulted in arcs when a voltage greater than 1150 V was supplied, and therefore, experiments were cut off at 1150 V. Electric field strengths (PEF intensities) were calculated from the applied voltage and gap size; therefore, the PEF intensities used in this part of the study ranged from 0 to 5.75 kV/cm. These results are shown in Figs. 5, 6, and 7. Unlike the 40-μs results, we did not observe any increase in overall electroporation. However, there was an increase of IRE at higher field strengths.

Figure 6.

Percentage of sample determined to be RE with a 100-μs pulse duration. The control group was EP in HBSS and the treatment group was EP in HBSS supplemented with 100 nM ionomycin. The average values of each sampled PEF intensity are depicted by “o” for control and “∗” for treatment. The error bars represent a 95% confidence interval. PEF intensities of 4.0 kV/cm had a statistically significant reduction in RE in the treatment samples. Regression lines represent the fitted cubic splines.

Figure 7.

Percentage of sample determined to be IRE with a 100-μs pulse duration. The control group was EP in HBSS, and the treatment group was EP in HBSS supplemented with 100 nM ionomycin. The average values of each sampled PEF intensity are depicted by “o” for control and “∗” for treatment. The error bars represent a 95% confidence interval. PEF intensities 4.0 kV/cm resulted in a statistically significant increase in IRE in the treatment samples. Regression lines represent the fitted cubic splines.

We analyzed the results for the 100-μs pulse durations using a cubic-spline regression with three knots, located at 1.5, 2.5, and 5 kV/cm. These results are shown in the next three sections.

NEP regression results

Results from the regression analysis for NEP outcomes indicated that only the effect of PEF intensity was significant. The results of the regression are shown in Table 5. Unlike 40 μs, there was neither a statistically significant direct effect of treatment on NEP outcomes nor a significant interaction between treatment and PEF intensity. Therefore, we conclude that ionomycin did not significantly alter the NEP outcomes for 100-μs pulse durations and that the effect of treatment was not different for different levels of PEF intensity. For this reason and being concerned about overfitting, we decided to exclude the interaction term from the model and refit the spline curve for PEF intensity without it (Fig. 5), as it is a better representation of the data. The regression results without the interaction term are shown in Table 6.

Table 5.

100-μs NEP Regression ANOVA Results

| Degrees of Freedom | Sum of Squares | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | 1 | 41 | 0.5111 |

| Spline of PEF | 4 | 140,132 | <0.0001 |

| Interaction | 4 | 285 | 0.5526 |

Table 6.

100-μs NEP Regression ANOVA Results—without Interaction

| Degrees of Freedom | Sum of Squares | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | 1 | 17 | 0.6701 |

| Spline of PEF | 4 | 140,155 | <0.0001 |

RE regression results

Results from the regression analysis for RE outcomes indicated that the direct effect of treatment with ionomycin was not significant, but the effect of PEF intensity and the interaction between treatment and PEF intensity were both significant. We conclude that hyperpolarizing the cellular membrane changes RE outcomes differently depending on the PEF intensity. Significant differences between the two curves occurred for specific portions of the plot, more precisely decreasing the chances for RE at higher PEF intensities using 100-μs pulse durations. The results of the regression are shown in Fig. 6 and Table 7.

Table 7.

100-μs RE Regression ANOVA Results

| Degrees of Freedom | Sum of Squares | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | 1 | 274 | 0.2031 |

| Spline of PEF | 4 | 63,172 | <0.0001 |

| Interaction | 4 | 4385 | 0.0001 |

IRE regression results

Results from the regression analysis for IRE outcomes indicated that the direct effect of treatment with ionomycin, PEF intensity, and the interaction between treatment and PEF intensity were significant, meaning they all resulted in statistically significant changes in electroporation percentage. Results of the regression are shown in Fig. 7 and Table 8. They confirm that hyperpolarizing the cellular membrane changed IRE outcomes differently depending on the PEF intensity, specifically increasing the chances for IRE at higher PEF intensities using 100-μs pulse durations. No departures of normality or heterogeneity of variances were found in the residual and variance check.

Table 8.

100-μs RE Regression ANOVA Results

| Degrees of Freedom | Sum of Squares | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | 1 | 522 | 0.0149 |

| Spline of PEF | 4 | 146,260 | <0.0001 |

| Interaction | 4 | 5785 | <0.0001 |

2.06 kV/cm results

In the last set of experiments, we used a fixed PEF intensity of 2.06 kV/cm and pulse durations of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 μs. Results are shown in Figs. 8, 9, and 10. Only the 40-μs pulse duration had a significant change in the electroporation outcome for both EP and RE compared to the control (no overlap in the 95% confidence interval). Overall, increased pulse duration yielded a small decrease in the percentage of EP and RE and an increase in IRE. There was no notable change in IRE between the control and treatment groups. We analyzed the results for 2.06 kV/cm experiments using a cubic-spline regression with two knots, located at 30 and 90 μs.

Figure 8.

Percentage of sample determined to be EP with a 2.06 kV/cm PEF intensity. The control group was EP in HBSS, and the treatment group was EP in HBSS supplemented with 100 nM ionomycin. Only 40-μs pulses resulted in significant differences in the percentage of EP cells. Error bars represent a 95% confidence interval. Regression lines represent the fitted cubic splines.

Figure 9.

Percentage of sample determined to be RE with a 2.06 kV/cm PEF intensity. The control group was EP in HBSS, and the treatment group was EP in HBSS supplemented with 100 nM ionomycin. Only 40-μs pulses resulted in significant differences in the percent of RE cells. Error bars represent a 95% confidence interval. Regression lines represent the fitted cubic splines.

Figure 10.

Percentage of sample determined to be IRE with a 2.06 kV/cm PEF intensity. The control group was EP in HBSS, and the treatment group was EP in HBSS supplemented with 100 nM ionomycin. There were no statistically different percentages of IRE cells. Error bars represent a 95% confidence interval. Regression lines represent the fitted cubic splines.

NEP regression results

Results from the regression analysis for NEP outcomes indicated that the direct effect of treatment with ionomycin, pulse duration, and the interaction between treatment and pulse duration were significant, meaning they all resulted in statistically significant changes in electroporation percentage. These results are shown in Fig. 8 and Table 9. We observed that each instance tested resulted in at least a slightly increased percent electroporated in the treatment group. Interestingly, although individually some NP values were not significant (overlapping 95% confidence intervals), when evaluated together, they were deemed significant (i.e., the direct effect of treatment was significant). The significant interaction term suggests that the effect of treatment is different for different levels of pulse duration; in other words, certain regions (specifically lower pulse durations) had an increased effect for the treatment when compared to the control.

Table 9.

Varied-Duration NEP Regression ANOVA Results

| Degrees of Freedom | Sum of Squares | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | 1 | 1539 | 0.0006 |

| Spline of duration | 4 | 4874 | <0.0001 |

| Interaction | 4 | 1237 | 0.0228 |

RE regression results

Results from the regression analysis for RE outcomes indicated that the direct effect of treatment with ionomycin, pulse duration, and the interaction between treatment and pulse duration were significant, meaning they all resulted in statistically significant changes in electroporation percentage. These results are shown in Fig. 9 and Table 10. Similar to the EP case, there is a visual trend of increases in RE for all but one pulse duration. The direct effect of treatment being significant agrees with the visual inspection. In addition, similar to EP results, the significant interaction term suggests that the effect of treatment is different for different pulse durations; in other words, certain regions (specifically lower pulse durations) had an increased effect for treatment when compared to the control.

Table 10.

Varied-Duration RE Regression ANOVA Results

| Degrees of Freedom | Sum of Squares | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | 1 | 1865 | 0.0012 |

| Spline of duration | 4 | 11,176 | <0.0001 |

| Interaction | 4 | 1823 | 0.0165 |

IRE regression results

Results from the regression analysis for IRE outcomes indicated pulse duration had a significant effect on IRE outcomes, but treatment with ionomycin and the interaction between treatment and pulse duration did not. These results are shown, including the interaction term, in Table 11. As the interaction was not significant, we removed the interaction term and reanalyzed the regression to avoid overfitting the data. Results without the interaction term are shown in Fig. 10 and Table 12. An increased pulse duration was shown to negatively affect IRE.

Table 11.

Varied-Duration IRE Regression ANOVA Results

| Degrees of Freedom | Sum of Squares | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | 1 | 16 | 0.6046 |

| Spline of duration | 4 | 1698 | <0.0001 |

| Interaction | 4 | 108 | 0.6175 |

Table 12.

Varied-Duration IRE Regression ANOVA Results

| Degrees of Freedom | Sum of Squares | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | 1 | 16.1 | 0.6046 |

| Spline of duration | 4 | 1698 | <0.0001 |

Discussion

Our results show that hyperpolarizing HL-60 cell membranes by adding ionomycin yields a statistically significant change in electroporation outcomes. In particular, making the transmembrane electric potential more negative by 13.2 ± 6.1 mV resulted in the following:

-

1.

Increase of RE outcomes at low PEF intensities and 40-μs pulse duration (1.8, 2.0, and 3.0 kV/cm). The most significant increase was observed at 2.0 kV/cm with 62.3% RE compared to 42.7% of the control.

-

2.

Increase of IRE outcomes at high PEF intensities for both 40- and 100-μs pulse durations.

-

3.

No statistically significant difference for electroporated or RE outcomes with 100-μs pulse durations.

Finally, our results from the fixed PEF intensity and variable-pulse-duration experiments suggest a slight increase in EP and RE across all pulse durations in addition to the significant increase at 40 μs.

The most likely biological mechanism that justifies the results found in this analysis is that hyperpolarizing the cell membrane before electroporation increases the resting transmembrane electrostatic energy (7), thereby reducing the PEF intensity threshold needed to create and expand membrane pores. Because cell death (IRE) can be caused by multiple factors, such as immediate death due to substantial, irreparable plasma membrane damage or delayed death due to internal organelle damage (53, 54, 55, 56), we further hypothesize that ionomycin only alters the external transmembrane potential, leaving the internal organelles’ transmembrane potentials unaltered. Therefore, for a given externally applied PEF intensity, the plasma membrane is more likely to be electroporated when the membrane is hyperpolarized. At lower applied electric field intensities (e.g., 40 μs and lower E field strengths between 1.8 and 3.0 kV/cm), this results in increasing RE while maintaining a similar level of IRE. Other studies have reported that for 40-μs pulses, the endoplasmic reticulum, the largest organelle in most eukaryotic cells, begins to experience electroporation at PEF intensities of around 2 kV/cm (55). This is the region in which we saw an increase of RE outcomes, suggesting that the increase in RE outcomes could be related to this phenomenon. At higher energy levels, we hypothesize that the main mechanism changes and more irreparable plasma membrane damage at a given field strength occurs when cells are hyperpolarized, causing the increase in IRE. This is consistent with existing knowledge that IRE (caused by high PEF intensities) is the result of rapid irreparable damage to the cell membrane (4, 7, 57, 58).

Results obtained in this analysis also support our initial claim that the relationship between PEF and electroporation outcome is nonlinear (4, 52). Because pore creation and thus electroporation outcomes are nonlinear (4), using piecewise cubic splines is a more recommended method for modeling outcomes than simplified linear models (48, 59). Alternative models such as low order-polynomial regressions are likely to miss important details in the fitted curves, whereas higher-order polynomial models can add artificial artifacts, potentially overfitting the model (48).

Cell-membrane hyperpolarization achieved using ionomycin combined with 40-μs pulses resulted in an increase in RE outcomes at lower PEF intensities. When the membrane was hyperpolarized, the peak percentage of RE with a 40-μs pulse (71.9%) was higher than with 100 μs (57.0%), revealing that membrane hyperpolarization can improve the efficiency of the RE procedures at select pulse durations. Increasing the likelihood of RE outcomes could be instrumental for practical applications of the results presented in this study. For example, the increase in the peak percentage of RE could increase the efficiency of RE-based drug-delivery therapies. When applying such therapies, one should also anticipate that the benefits of hyperpolarizing the cell membrane for RE applications appear to be limited to a relatively small range of pulse durations. We note that the results presented here were based on in vitro experiments, and some applications may require additional in vivo studies.

Similarly, cell-membrane hyperpolarization achieved using ionomycin showed an increase in IRE outcomes at higher field strengths for both the 40- and 100-μs pulse durations. The 100-μs experiments resulted in the highest peak percentage of IRE outcomes. The significant difference (>2×) of pulse length between these two data sets demonstrates a wide window of parameter space in which membrane hyperpolarization effects can increase IRE outcomes. These results are interesting for practical applications such as tumor ablation, for which increasing the efficiency of IRE could either increase the size of the ablation zone if keeping all the pulse parameters the same or decrease the required field strength or pulse duration to achieve a particular treatment. For example, electroporation protocols using longer pulse durations encounter problems such as heating, arcing, thermal effects, etc. at lower PEF intensities than protocols using shorter pulse durations. In fact, from analyses such as those reported by Ji et al., avoidance of thermal effects favors shorter pulses (60), and thus, decreasing thresholds for IRE reduces the likelihood of thermal effects. Additionally, similar to the idea discussed by Kennedy et al. (3), if membrane hyperpolarization can be combined with targeting methods (i.e., specifically hyperpolarizing tumor cells while not affecting noncancerous cells), techniques could be developed to improve tumor destruction while sparing nearby healthy tissues.

Conclusions

The addition of ionomycin caused a 13.2 ± 6.1 mV (more negative) difference in transmembrane potential in HL-60 cells suspended in HBSS. This change in transmembrane potential before electroporation affected electroporation outcomes at both low and high PEF intensities. The probability of RE was increased at low PEF intensities and short pulse durations (particularly 40 μs), whereas the probability of NEP outcomes decreased. At high PEF intensities, the probability of IRE increased, whereas the probability of RE decreased.

Changing the transmembrane electric potential allows for improved control and selectivity of electroporation outcomes. Controlled, selective increase of RE outcomes could improve the efficacy of electroporation for in vitro procedures and in vivo therapies involving transfection or drug delivery. Controlled, selective increase of IRE outcomes could improve the efficacy of electroporation for IRE ablation therapies.

Author Contributions

E.J.A. performed study design, data collection, cell culture, microscopy imaging, image analysis, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of manuscript. B.G.K. performed study design and data collection. S.Y. performed data collection and interpretation. S.C.H. performed study design, data analysis and interpretation, and critical revision of the manuscript. J.H.B. performed study design, data analysis and interpretation, and critical revision of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Vera Cardoso Ferreira for assistance with statistical analysis and interpretation of data.

This work was supported by the Duane H. and Dorothy M. Bluemke professorship and the Philip Dunham Reed professorship.

Editor: Ana-Suncana Smith.

Footnotes

One figure is available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(18)30620-9.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Weaver J.C. Electroporation: a general phenomenon for manipulating cells and tissues. J. Cell. Biochem. 1993;51:426–435. doi: 10.1002/jcb.2400510407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abidor I.G., Arakelyan V.B., Tarasevich M.P. Electric breakdown of bilayer lipid membranes. I. The main experimental facts and their qualitative discussion. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1979;104:37–52. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy S.M., Aiken E.J., Murphy W.L. Cationic peptide exposure enhances pulsed-electric-field-mediated membrane disruption. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weaver J.C. Electroporation of cells and tissues. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2000;28:24–33. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neumann E., Sowers A.E., Jordan C.A. Plenum Press; New York: 1989. Electroporation and Electrofusion in Cell Biology. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shirakashi R., Sukhorukov V.L., Zimmermann U. Measurement of the permeability and resealing time constant of the electroporated mammalian cell membranes. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2004;47:4517–4524. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Sakere B., André F., Mir L.M. Tumor ablation with irreversible electroporation. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubinsky B., Onik G., Mikus P. Irreversible electroporation: a new ablation modality--clinical implications. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2007;6:37–48. doi: 10.1177/153303460700600106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillips M., Maor E., Rubinsky B. Nonthermal irreversible electroporation for tissue decellularization. J. Biomech. Eng. 2010;132:091003. doi: 10.1115/1.4001882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu D.S., Raman S.S., Lassman C. Effect of vessel size on creation of hepatic radiofrequency lesions in pigs: assessment of the “heat sink” effect. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2002;178:47–51. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.1.1780047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg M.D., Kim C.Y., Nelson R.C. Percutaneous cryoablation of renal lesions with radiographic ice ball involvement of the renal sinus: analysis of hemorrhagic and collecting system complications. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2011;196:935–939. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arena C.B., Szot C.S., Davalos R.V. A three-dimensional in vitro tumor platform for modeling therapeutic irreversible electroporation. Biophys. J. 2012;103:2033–2042. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badylak S.F. Xenogeneic extracellular matrix as a scaffold for tissue reconstruction. Transpl. Immunol. 2004;12:367–377. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang C., Davalos R.V., Bischof J.C. A review of basic to clinical studies of irreversible electroporation therapy. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2015;62:4–20. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2014.2367543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.André F., Mir L.M. DNA electrotransfer: its principles and an updated review of its therapeutic applications. Gene Ther. 2004;11(Suppl 1):S33–S42. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishi T., Yoshizato K., Ushio Y. High-efficiency in vivo gene transfer using intraarterial plasmid DNA injection following in vivo electroporation. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1050–1055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang L., Howdyshell M., Sooryakumar R. Magnetic tweezers-based 3D microchannel electroporation for high-throughput gene transfection in living cells. Small. 2015;11:1818–1828. doi: 10.1002/smll.201402564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konishi M., Kawamoto K., Yamashita T. Gene transfer into guinea pig cochlea using adeno-associated virus vectors. J. Gene Med. 2008;10:610–618. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin H., Kanasty R.L., Anderson D.G. Non-viral vectors for gene-based therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014;15:541–555. doi: 10.1038/nrg3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haberl S., Kandušer M., Pavlin M. Effect of different parameters used for in vitro gene electrotransfer on gene expression efficiency, cell viability and visualization of plasmid DNA at the membrane level. J. Gene Med. 2013;15:169–181. doi: 10.1002/jgm.2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gehl J. Electroporation: theory and methods, perspectives for drug delivery, gene therapy and research. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2003;177:437–447. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin J., Chen R., Zeng H. Rapid delivery of silver nanoparticles into living cells by electroporation for surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009;25:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schelly Z.A. Subnanometer size uncapped quantum dots via electroporation of synthetic vesicles. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2007;56:281–284. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo D., Saltzman W.M. Synthetic DNA delivery systems. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:33–37. doi: 10.1038/71889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt-Wolf G.D., Schmidt-Wolf I.G. Non-viral and hybrid vectors in human gene therapy: an update. Trends Mol. Med. 2003;9:67–72. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(03)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun L., Li J., Xiao X. Overcoming adeno-associated virus vector size limitation through viral DNA heterodimerization. Nat. Med. 2000;6:599–602. doi: 10.1038/75087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinbrunn T., Chatterjee M., Stühmer T. Efficient transient transfection of human multiple myeloma cells by electroporation--an appraisal. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsong T.Y. Electroporation of cell membranes. Biophys. J. 1991;60:297–306. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82054-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimmermann U., Pilwat G., Riemann F. Effects of external electrical fields on cell membranes. Bioelectrochem. Bioenerg. 1976;3:58–83. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tekle E., Astumian R.D., Chock P.B. Electro-permeabilization of cell membranes: effect of the resting membrane potential. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990;172:282–287. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee J.W. Proton-electrostatic localization: explaining the bioenergetic conundrum in alkalophilic bacteria. Bioenergetics. 2015;4:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saeed H.A., Lee J.W. Experimental demonstration of localized excess protons at a water-membrane interface. Bioenerg. Open Access. 2015;4:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wegner L.H., Frey W., Silve A. Electroporation of DC-3F cells is a dual process. Biophys. J. 2015;108:1660–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stock J.T., Ora M.V. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 1989. Electrochemistry, Past and Present. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brent L.H., Rubenstein B., Wieland S.J. Transmembrane potential responses during HL-60 promyelocyte differentiation. J. Cell. Physiol. 1996;168:155–165. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199607)168:1<155::AID-JCP19>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kinosita K., Jr., Tsong T.Y. Formation and resealing of pores of controlled sizes in human erythrocyte membrane. Nature. 1977;268:438–441. doi: 10.1038/268438a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hibino M., Shigemori M., Kinosita K., Jr. Membrane conductance of an electroporated cell analyzed by submicrosecond imaging of transmembrane potential. Biophys. J. 1991;59:209–220. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82212-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neumann E., Kakorin S., Toensing K. Fundamentals of electroporative delivery of drugs and genes. Bioelectrochem. Bioenerg. 1999;48:3–16. doi: 10.1016/s0302-4598(99)00008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leontiadou H., Mark A.E., Marrink S.J. Molecular dynamics simulations of hydrophilic pores in lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 2004;86:2156–2164. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74275-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tarek M. Membrane electroporation: a molecular dynamics simulation. Biophys. J. 2005;88:4045–4053. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.050617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teissie J., Golzio M., Rols M.P. Mechanisms of cell membrane electropermeabilization: a minireview of our present (lack of? ) knowledge. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1724:270–280. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Charpentier K.P., Wolf F., Dupuy D.E. Irreversible electroporation of the liver and liver hilum in swine. HPB. 2011;13:168–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin R.C.G. Irreversible electroporation: a novel option for treatment of hepatic metastases. Curr. Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2013;9:191–197. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maor E., Ivorra A., Rubinsky B. Vascular smooth muscle cells ablation with endovascular nonthermal irreversible electroporation. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2010;21:1708–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pittet D., Di Virgilio F., Lew D.P. Correlation between plasma membrane potential and second messenger generation in the promyelocytic cell line HL-60. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:14256–14263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.R Core Team. 2013. R Core Team. R A Lang. Environ. Stat. Comput. R Found. Stat. Comput. Vienna, Austria, http://www.R-project.org/.

- 47.Albrektsen G., Heuch I., Kvåle G. Breast cancer risk by age at birth, time since birth and time intervals between births: exploring interaction effects. Br. J. Cancer. 2005;92:167–175. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Durrleman S., Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat. Med. 1989;8:551–561. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Friedman J.H., Roosen C.B. An introduction to multivariate adaptive regression splines. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 1995;4:197–217. doi: 10.1177/096228029500400303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aggrey S.E. Comparison of three nonlinear and spline regression models for describing chicken growth curves. Poult. Sci. 2002;81:1782–1788. doi: 10.1093/ps/81.12.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bates D., Mächler M., Walker S.C. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015;67:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Talele S., Gaynor P. Non-linear time domain model of electropermeabilization: effect of extracellular conductivity and applied electric field parameters. J. Electrost. 2008;66:328–334. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piñero J., López-Baena M., Cortés F. Apoptotic and necrotic cell death are both induced by electroporation in HL60 human promyeloid leukaemia cells. Apoptosis. 1997;2:330–336. doi: 10.1023/a:1026497306006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Joshi R.P., Schoenbach K.H. Mechanism for membrane electroporation irreversibility under high-intensity, ultrashort electrical pulse conditions. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2002;66:052901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.66.052901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weaver J.C., Smith K.C., Gowrishankar T.R. A brief overview of electroporation pulse strength-duration space: a region where additional intracellular effects are expected. Bioelectrochemistry. 2012;87:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gowrishankar T.R., Esser A.T., Weaver J.C. In silico estimates of cell electroporation by electrical incapacitation waveforms. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2009;2009:6505–6508. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5333138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miller L., Leor J., Rubinsky B. Cancer cells ablation with irreversible electroporation. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2005;4:699–705. doi: 10.1177/153303460500400615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rubinsky B. Irreversible electroporation in medicine. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2007;6:255–260. doi: 10.1177/153303460700600401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suits D.B., Mason A., Chan L. Spline functions fitted by standard regression methods. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1978;60:132–139. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ji Z., Kennedy S.M., Hagness S.C. Experimental studies of persistent poration dynamics of cell membranes induced by electric pulses. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2006;34:1416–1424. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.