Abstract

This study hypothesizes that a novel oncolytic chimeric orthopoxvirus CF33-Fluc is imageable and targets colorectal cancer cells (CRCs). A novel chimeric orthopoxvirus (CF33) was constructed. The thymidine kinase locus was replaced with firefly luciferase (Fluc) to yield a recombinant virus—CF33-Fluc. In vitro cytotoxicity and viral replication assays were performed. In vivo CRC flank xenografts received single doses of intratumoral or intravenous CF33-Fluc. Viral biodistribution was analyzed via luciferase imaging and organ titers. CF33-Fluc infects, replicates in, and kills CRCs in vitro in a dose-dependent manner. CF33 has superior secretion of extracellular-enveloped virus versus all but one parental strain. Rapid tumor regression or stabilization occurred in vivo at a low dose over a short time period, regardless of the viral delivery method in the HCT-116 colorectal tumor xenograft model. Rapid luciferase expression in virus-infected tumor cells was associated with treatment response. CRC death occurs via necroptotic pathways. CF33-Fluc replicates in and kills colorectal cancer cells in vitro and in vivo regardless of delivery method. Expression of luciferase enables real-time tracking of viral replication. Despite the chimerism, CRC death occurs via standard poxvirus-induced mechanisms. Further studies are warranted in immunocompetent models.

Keywords: extracellular enveloped virus, systemic therapy, viral therapy, gene expression, oncolytic virus

Introduction

Nearly fifty thousand people in the United States died from colorectal cancer in 2016.1 Current screening and treatment modalities have improved survival through interventions aimed at earlier stages of cancer. While the limits of what is resectable for oligometastatic disease continue to expand, the 5-year survival in disseminated metastatic disease still remains at 14%.1 Treatments for advanced disease remain dependent on cytotoxic chemotherapy.2 More robust tumor-specific systemic therapies are needed.

Oncolytic viruses offer the benefit of tumor-selective replication with a tolerable side effect profile relative to modern chemotherapeutics. Oncolytic virus researchers are now harnessing the immunomodulatory effects of viral therapies to combine the benefits of direct cancer cell killing with immunotherapy.3 Intravenous (i.v.) delivery of oncolytic viruses enables a broad distribution of virus, particularly in previously seronegative hosts, which can be attractive in disseminated disease.4 However, many pre-clinical and clinical studies with oncolytic viruses have demonstrated abscopal anti-tumor immune effects on non-injected lesions after intratumoral injections and have also demonstrated virus replication in non-injected lesions.5, 6, 7 Thus, the ideal delivery route for virus therapy is not yet established and ultimately may vary by vector and disease type. Proponents of intratumoral therapy note that smaller doses are required, which may thus result in enhanced tumor destruction and diminished side effects. Via either delivery route, the goal is to precipitate tumor cell lysis and thereby prime the adaptive immune system against tumor antigens and alter future tumor proliferation in the same way a vaccination mitigates future infection.8, 9

Whereas oncolytic virus researchers once thought of the immune system as an enemy that only served to clear virus and prevent virus replication, our understanding of the benefits of immunomodulation toward anti-tumor immunity makes vectors with immunostimulatory capacities very attractive. The poxvirus family is especially attractive as an agent of immunomodulation as the large cloning capacity of poxviruses allows for insertion of one or more immune-modulatory genes such as granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interleukin 12 (IL-12), and anti-programmed death ligand 1 (PDL1) among others. Furthermore, orthopoxviruses like vaccinia virus also exist in a host-cloaked enveloped extracellular virion (EEV) secreted as part of the their life cycle,10 which are resistant to neutralization by host’s immune system.11 This is particularly important when considering the treatment of metastatic malignancies given the potential capability of EEVs to disseminate from injected tumor to sites of distant metastases. However, previously constructed vaccinia vectors have seen challenges of diminished anti-tumor efficacy and potency in clinical settings. Our group sought to create a new, more efficient vector that could overcome limitations of prior vectors using recombination to amalgamate factors associated with enhanced anti-tumor efficacy while also maximizing immunostimulatory potential.

While cancer cell death resulting from vaccinia infection remains incompletely characterized, other investigators have demonstrated that classical apoptosis is not the primary mode of cell death, and while vaccinia interferes with the autophagic process, it does not increase autophagic flux nor does it rely on autophagy to induce cancer cell death.12 Though there are data to suggest that some vaccinia-infected cells can undergo apoptosis, most vaccinia-infected cells appear to undergo programmed necrosis (also called necroptosis).13 Thus, part of this work aimed to establish mechanisms of virus-induced cell death in order to compare behavior of this recombinant vector to known behavior patterns of parental viruses.

Efficacy of viroimmunotherapy is dependent on multiple factors, including route of delivery and replication strength of the virus, mechanisms of cell death, host immune response, and dosing strategies. This new vector seeks to optimize all of these components with the added bonus of allowing for non-invasive imaging to track viral efficacy in real time. We hypothesized that creation of a chimeric poxvirus vector would yield a vector more potent than its parent viruses that is also immunostimulatory and capable of non-invasive imaging and thus real-time monitoring of viral replication.

Results

CF33-Fluc Kills Colorectal Cancer Cells In Vitro and Shows Superior Viral Secretion Relative to Known Secreting Parental Viruses

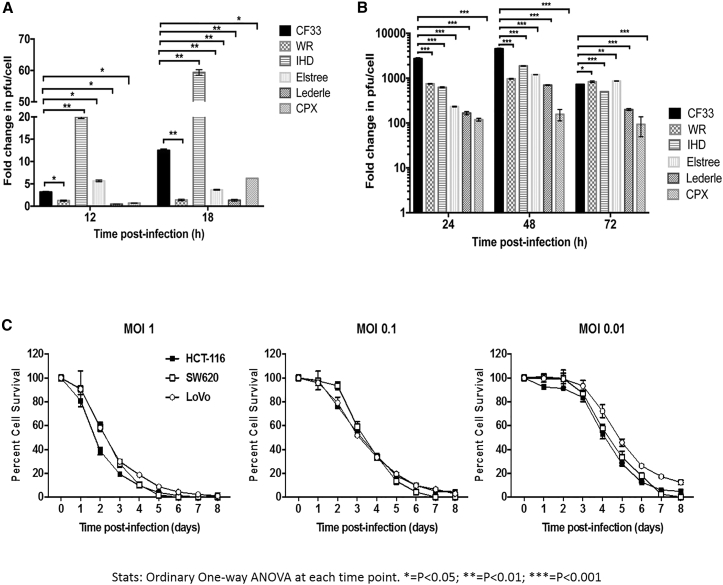

When titered from supernatants, CF33 was found to have higher EEV-forming potential than all parental viruses except the International Health Department (IHD) strain of vaccinia virus, which is known to form excessive EEV in supernatant (Figure 1A). However, the overall viral titer of CF33, including EEV and other forms of viruses in the cell lysates, was found to be higher than all parental viruses, including the IHD strain, at 48 hr and higher than or similar to all parental strains at 72 hr (Figure 1B). CF33-Fluc (firefly luciferase) showed dose-dependent cell killing in colorectal cancer cell lines HCT-116, SW620, and LoVo (Figure 1C). At MOI 1, virtually 100% cell death is noted relative to control by 120 hr post-infection. At the lower concentrations of 0.1 and 0.01, nearly all cells are dead by 6 and 8 days, respectively. Of note, DNA sequence analysis of CF33 revealed that the overall sequence matched more closely to vaccinia virus (VACV) genomes. In the absence of published sequences for some of the parental viruses, we have not performed detailed sequence comparisons to pinpoint what sequence variations make the CF33 virus superior to the parental viruses. However, in the future, we plan to perform in-depth sequence analysis for better understanding of the mechanisms through which CF33 out-performs its parental viruses.

Figure 1.

CF-33 Possesses Superior Replication versus Parental Strains and Is Robustly Cytotoxic against Colon Cancer Cells In Vitro in a Dose-Dependent Manner

Parental virus strains and CF-33-infected HCT116 cells. (A) Secreted form of external enveloped virions (EEV) were measured from supernatant at 12 and 18 hr post-infection. (B) Lysates from infected HCT116 cells were measured at 24, 48, and 72 hr. Viral titers were measured via standard plaque assays. (C) CF-33 kills colon cancer cells HCT-116, SW620, and LoVo in a dose-dependent manner. Error bars indicate SD. Ordinary one-way ANOVA was used at each time point. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Fold change in PFU/cell is in comparison to titers of uninfected cells at 0 hr immediately prior to infection.

CF33-Fluc Luciferase Expression Is Confirmed In Vitro and Corresponds with Virus Titer

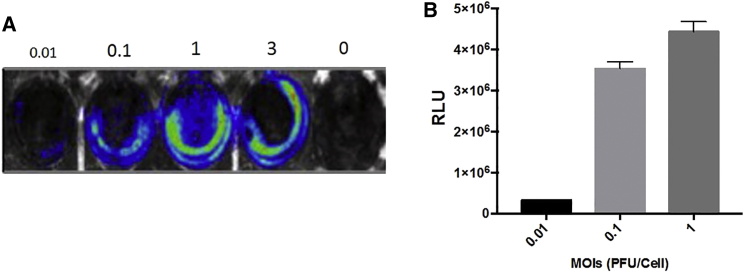

HCT-116 cells were infected for 24 hr with CF33-Fluc at MOIs 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 3. Increasing MOI corresponded with increasing relative units measured from luciferase activity (Figures 2A and 2B). Virally expressed luciferase is therefore dependent on the concentration of virus and higher viral concentrations correspond to higher viral titers in vitro.

Figure 2.

Virus-Encoded Luciferase Activity Is Dose Dependent In Vitro

(A) HCT116 cells were infected with CF33-Fluc virus at indicated MOIs in a 6-well plate format. Cells were imaged 24 hr post-infection for bioluminescence using Lago-X imaging system. (B) Cells were infected as in (A), and cell lysates were collected 24 hr post-infection. Total luciferase activity was measured in relative lumominometer units (RLU) using luciferase assay kit. The differential luciferase expression, which seems stronger on the periphery, is attributed to confluence of plated cells, which was denser on inferior periphery of the wells. Moreover, the absence of central luciferase expression at lower MOIs is likely due to decreased levels of infectivity at the 24-hr time point, whereas absence of central luciferase expression at MOI of 3 is attributed to cell death. Error bars indicate SD.

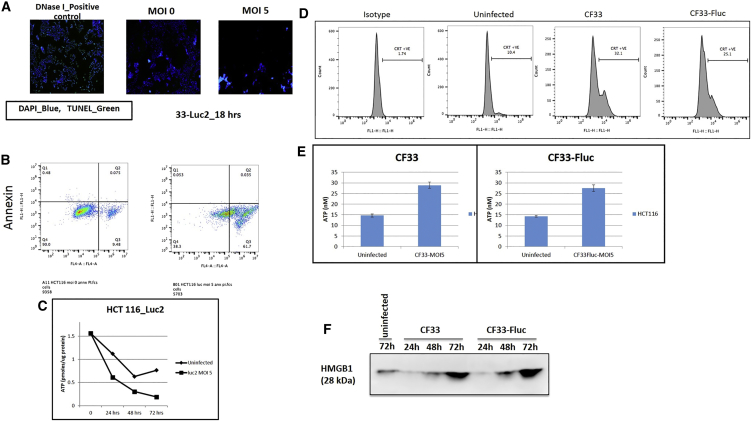

CF-33 Induces Cancer Cell Death via Necroptotic Immune Cell Death Pathways

In order to determine the mechanism through which our virus kills cancer cells, we performed a number of assays reflective of different modes of cell death. First, we stained virus-infected or mock-infected cells with annexin V, caspase-3, and propidium iodide (PI) and then analyzed the cells using flow cytometry. Eighteen hours post-infection, only a small fraction of cells (∼5%) were found to be positive for annexin V and caspase-3 (Figure 3A). However, more than 60% cells stained positive for PI, indicating that necrosis is the predominant mode through which the virus kills HCT116 cells. Furthermore, we also performed a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay, which reflects DNA degradation typically associated with apoptosis, on cells infected with CF-33. Almost complete absence of TUNEL-positive cells was observed in virus-infected cells, much like the mock-infected cells (Figure 3B). This again confirms that our virus kills HCT116 cells through pathways other than apoptosis. Lastly, to confirm if the virus induces necrosis in infected cells, we measured the levels of total adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in virus-infected cells at different time points and compared with that in mock-infected cells. It is well-known that cells undergoing necrosis demonstrate reduction in ATP levels. With increase in time after infection, reduction in total ATP was observed in virus-infected cells and the total levels of ATP at 48 and 72 hr were significantly lower in virus-infected cells than those in mock-infected cells (Figure 3C). Taken together, these data suggest that necrosis is the main mechanism through which the CF-33 kills HCT116 cells.

Figure 3.

Virally Induced Cell Death Occurs via Necroptotic Pathways

(A) Virally infected fluorescent microscopy shows TUNEL assay controls demonstrating fluorescent green DNA damage indicative of apoptosis, whereas both uninfected cells and highly infected cells at a high-dose MOI of 5 demonstrate no evidence of DNA damage. (B) FACS analysis of annexin and phosphatidyl inostitol (PI) examining non-infected cells (left) and infected cells (right) 18 hr post-infection. This indicates that while many dead cells are present (indicated by PI), none are undergoing apoptosis as a result of viral infection (annexin). (C) Infected cells demonstrate significantly lower quantities of ATP than non-infected controls at 48 and 72 hr. Error bars indicate SD. Student’s t test was used. *** indicates statistical significance defined as p < 001 for 48-hr and 72-hr time points. (D) Calreticulin was analyzed via flow cytometry with and without viral infection, demonstrating increased caltreticulin from infected cells. (E) ATP secretion in supernatants was demonstrated to be at least 1.5-fold higher in infected cells (error bars indicate SD). (F) HMGB1 protein secretion in supernatants of infected cells was substantially more pronounced in infected versus non-infected cells.

Immune cell death assays examining calreticulin, ATP and HMGB1 secretion in supernatants of infected and non-infected cells was performed. Calreticulin staining was increased 2- to 3-fold in infected cells (Figure 3D). The same effect was seen in supernatant secretion of ATP (Figure 3E), and a similar trend was seen in HMGB1 expression (Figure 3F). Taken together, these findings confirm immune cell death pathways in virally infected cells.

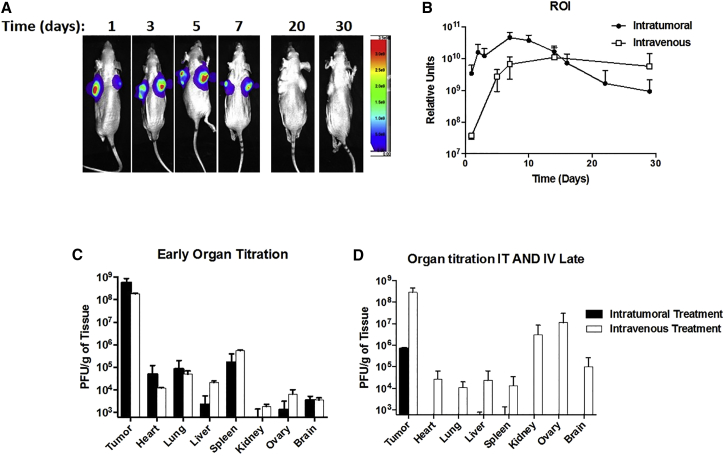

In Vivo Confirmation of Luciferase Expression via Bioluminescence Imaging Shows Intratumoral Viral Replication that Corresponds to High Intratumoral Viral Titers and Immunohistochemistry

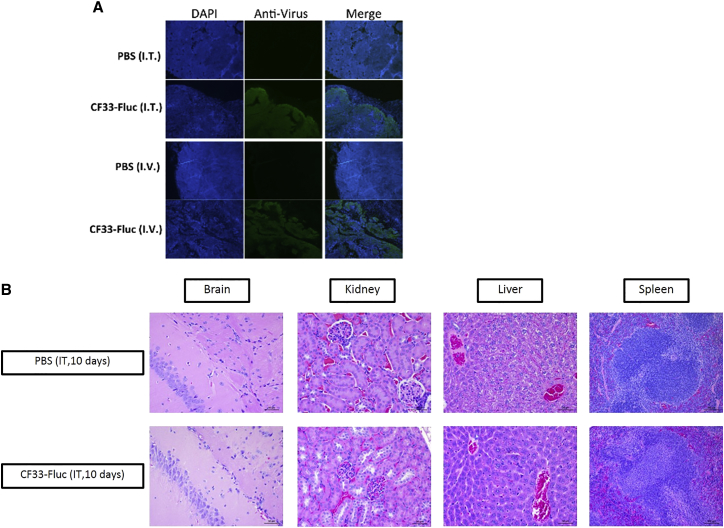

No immunohistochemical differences noted between infected and non-infected animals. Luciferase activity in vivo was detected in the intratumoral and i.v. groups as early as day 1 post-injection (Figure 4A). The intratumoral delivery of CF33-Fluc peaked higher and earlier than the intravenous delivery group, but similar ultimate sustained luciferase intensities were noted in the region of interests (Figure 4B). Day 7 post-injection had the highest relative bioluminescence units in the intratumoral group, which is the first day that tumors began to plateau. After day 14, nearly all viral replication in the intratumoral (i.t.) group had ceased, and this corresponded to the regression of tumor size. In the i.v. group, persistent expression of luciferase continued until day 28 and also corresponded with decreased speed of tumor regression. High viral titers were seen in tumors early in the treatment phase with other solid organs containing at least 3-log lower particle-forming units (PFU)/g. Similar virus titers in tumors and organs were seen in i.t versus i.v groups, 10 days post-injection (Figure 4C). As tumor regression occurred, virus titers in organs approached nil 50 days post-injection in the i.t. group, whereas persistent viral replication was seen at the later time point in the i.v. group (Figure 4D). This corresponded to more rapid tumor regression in the i.t. group. At 10 days post-injection, immunohistochemistry (IHC) of tumor sections infected with CF33-Fluc, regardless of delivery method, showed virus infection, although in a slightly different morphological distribution pattern (Figure 5A). Organs of representative infected and non-infected control mice, including brain, lung, liver, spleen, heart, kidney, and adrenal gland, were histopathologically analyzed by a small animal pathologist in our institution’s small animal pathology core facility and were found to be identical to each other in appearance. Figure 5B demonstrates representative pictures of vital organs.

Figure 4.

CF33-Fluc Bioluminescence Corresponds with Tumor Viral Titers

(A) Representative mouse received intratumoral (IT) injection of CF33-Fluc. Bioluminescence corresponds with viral titers and tumor regression. (B) Average intensity of bioluminescence in the region of interest (ROI) took longer to achieve in intravenous (IV) groups but had a sustained response that correlated with viral replication. (C) Similar IV versus IT tumor and organ titers 10 days post-infection. (D) At 50 days post-infection, prolonged tumor viral titer in IV group, but lower titer in IT group, corresponds with tumor regression and thereby decreased viral activity. Error bars indicate SD.

Figure 5.

Virus Spread in the Tumor following Intratumor or Intravenous Injection and Examination of Vital Organs in Infected and Non-infected Mice

(A) Whereas the IV group had a more infiltrative pattern of infection, the IT group had a more uniform leading edge of viral infectivity, likely indicating that efficacy was a direct function of oncolytic ability and effective viral delivery. (B) Representative slides of brain, kidney, liver, and spleen are shown demonstrating no differences in histopathological organ appearance based upon viral infection.

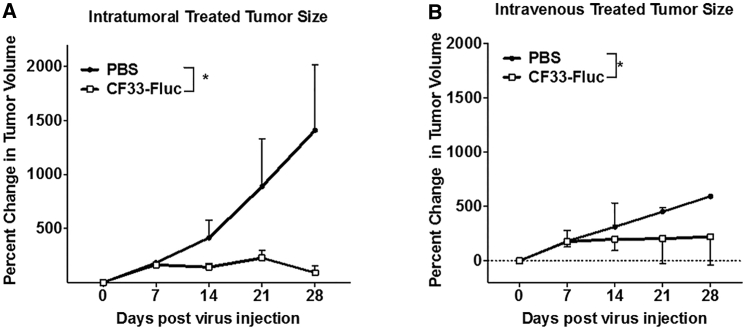

Colorectal Cancer Xenografts Regress following i.t. or i.v. Treatment with CF33-Fluc

Both i.t. and i.v. delivery of CF33-Fluc caused significant tumor regression (Figures 6A and 6B). Athymic mice bearing HCT-116 xenografts received a single dose of 105 PFUs/tumor of CF33-Fluc via i.t. injection. As mice had bilateral tumors, these mice received a total dose of 2 × 105 PFU/mouse. Significant tumor regression was observed relative to PBS-injected controls (p = 0.037). By the termination of the experiment, control mice had developed tumors meeting pre-established criteria for euthanasia. With the single 105 PFUs of CF33-Fluc injected i.v., significant tumor stabilization was noted when compared to control, and in some cases, tumor regression was noted (p = 0.034). Thus, tumor regression occurs in both i.t. and i.v. delivery of CF33-Fluc.

Figure 6.

CF33-Fluc Shows Anti-tumor Activity in HCT116 Xenograft Model following Intratumoral and Intravenous Delivery

Both IV (B) (eight mice/group with four sacrificed at day 10) and IT (A) (five mice/group with two sacrificed at day 10) delivery methods result in tumor growth abrogation compared to controls (four mice for IV PBS control, and two mice for IT control). Both IT and IV treatment groups had individual mice with complete pathologic tumor regression. *IT p = 0.037; *IV p = 0.034.

Discussion

This study examined the efficacy of a novel chimeric poxvirus against human colon cancer. An immunodeficient animal model explored delivery routes and found that i.v., while less efficient, was no less effective. Furthermore, replication efficiency and mechanisms of cell death are explored in relationship to other parental poxvirus vectors. Lastly, this study confirms that viral replication can be monitored with real-time non-invasive imaging. We confirmed our hypothesis that our novel chimeric orthopoxvirus CF33-Fluc was more potent than parental viruses in both the total virus and EEV form. Moreover, by noting that more intense Fluc expression in vivo corresponded with increased viral titers, we confirmed that viral tumor infiltration could be monitored in real time and that viral replication is associated with tumor regression in a murine model. Finally, by examining the cell death mechanisms initiated by CF-33, we are able to further characterize the function of this new chimeric vector as similar to other poxviruses.

An encouraging finding was the superior secretion of EEV in our in vitro model compared to parental viruses. The only parental virus with superior EEV secretion was vaccinia strain IHD, which has been studied extensively for its progeny secreting capability and potency.14 Previous studies have shown that a point mutation in the A34R gene, found in the IHD strain, allows the superior secretion of EEV.15 Interestingly, the genetic sequence of CF33 does not contain the A34R mutation so the etiology of increased secretion is under investigation. Additionally, the overall viral titer of CF33, including both EEV and other infectious forms of virus in the cell lysate, was found to be higher than all parental viruses, including the IHD strain. This potency may be part of how the virus is able to maintain efficacy even via the ostensibly more dilute i.v. delivery system, which also occurred at a lower overall dose. Further in vitro analysis demonstrated that insertion of Fluc at thymidine kinase (tk) locus did not alter viral efficacy in terms of cytotoxicity or viral replication (data not shown).

This study shows that i.t. delivery enables robust production of CF33-Fluc EEV early-on prior to any clearance, which is likely to be critical to viral success in immunocompetent models. Much debate still exists about the optimal delivery routes for oncolytic viruses. Efficacy may also be squelched by prior immunity or other unforeseen effects of immune clearance through first-pass metabolism.16, 17 Interestingly, only one of three mice in the i.t. group had detectable virus in areas outside the tumor at the termination of the experiment. Those two mice without detectable virus had no residual tumors. The remaining mouse had ongoing tumor regression. Thus, it appears that in the i.t. group, once tumor cells are cleared, virus is cleared. In the i.v. group, persistent virus titers in tumors and organs were seen in the later phases of tumor regression. That said, given the slower speed of i.t. viral replication in the i.v. group, it stands to reason that slower viral clearance would be seen, and perhaps had animals been followed out past the limits of the protocol, these differences would have been overcome. Future experiments will challenge whether this is a function of delivery route, tumor destruction, or both and will also evaluate if viral clearance is a marker of anti-tumor immunity.

This study demonstrated the ability of CF33-Fluc to facilitate real-time non-invasive imaging of viral replication in a manner that also clearly correlated with anti-tumor efficacy. Previous investigators in our group have shown similar capabilities both with bioluminescence for GFP and with functional imaging secondary to use of a human sodium iodide (hNIS) symporter and have seen uptake and fluorescence correlate with viral titers.18, 19, 20 Other teams have also demonstrated that intensity of bioluminescence and functional imaging corresponds with absolute viral replication and have posited that imaging would be helpful in monitoring when an i.t. “viral threshold” has been achieved.21 In the clinical setting, this real-time evaluation of viral replication could assist in proper dosing, correlate laboratory toxicities to the clinical picture, and ultimately further our understanding of the complex interplay between the immune system and direct viral oncolysis.

Lastly, this work demonstrates that our novel chimeric vector CF33-Fluc has similar mechanisms of cell killing as other parent orthopox viruses via necroptosis pathways as demonstrated by negative TUNEL assays, as well as fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), immunogenic cell death (ICD), and ATP analyses shown in Figure 3. Previous studies have demonstrated similar findings but have noted heterogeneity among death mechanisms in poxvirus strains.12, 13 For example, Whilding et al.12 have elegantly demonstrated that infection of ovarian cancer cells with wild-type or thymidine kinase-deleted Lister strain vaccinia virus kills cells via necrosis that is mediated by a series of programmed events not involving autocrine cytokine release. Further studies are needed in this arena to more fully characterize the cancer-killing efficacy of this novel vector. It should be noted that whereas previous studies have typically used 2 × 107 PFUs of oncolytic poxviruses and, often multiple doses, to achieve anti-tumor activities in murine models, our novel vector exerted significant anti-tumor effect with a single dose of only 1 × 105 PFUs.19

Limitations include that the absolute viral titers cannot be directly compared secondary to dosing mismatch; however, the different trends of viral tumor and organ titers between i.t. and i.v. delivery groups are notable. i.t. delivered CF33-Fluc replication led to more rapid i.t. viral replication, as seen in the luciferase expression as early as 1 day post-infection. i.v. viral delivery takes longer to peak in luciferase expression within the tumors. We are unable to say for certain if this is due to higher dose per mouse or simply due to more effective delivery of virus directly to the tumor or both. Future studies will be directed at this question in immunocompetent models.

Conclusions

Chimeric CF33 killed colorectal cancer cells in multiple cell lines in vitro. More CF33 was secreted following viral infection in vitro when compared to all but one of the parental strains of orthopoxvirus. Both i.v. and i.t. delivery of CF33-Fluc caused tumor regression when compared to mock-treated control mice. i.t. delivery of CF33-Fluc caused more rapid tumor-specific replication of virus in vivo. Initial examinations of cell death resulting from CF33-Fluc infection reveal that extra-apoptotic mechanisms of cell death are utilized by this novel vector. Future investigations will aim to understand the mechanism of improved EEV secretion in i.t. delivery, which will further improve delivery of immune-evading virus to distant disease. This will be evaluated in a metastatic model in immunocompetent mice.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Maintenance

African green monkey kidney fibroblasts (CV-1), purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in DMEM (Corning, Corning, NY). Human colorectal cell lines were all purchased from ATCC. HCT-116 was maintained in McCoy’s 5A medium (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD), SW620 was maintained in RPMI medium 1640 (Corning, Corning, NY) and LoVo was maintained in Ham’s F-12K (Kaighn’s) medium (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD). All cells were kept at 37°C and 5% CO2. No experiments were performed beyond the tenth cell passage. Unless stated otherwise, cells were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution, both purchased from Corning (Corning, NY).

CF33 Chimerization and Luciferase Insertion

Nine strains of orthopoxvirus were used to create CF33 by co-infecting CV-1 cells and fostering chimerization. These were cowpox virus strain Brighton, raccoonpox virus strain Herman, rabbitpox virus strain Utrecht, vaccinia virus strains Western Reserve, IHD, Elstree, Connaught Laboratories, Lederle-Chorioallantoic, and AS, all purchased from ATCC and grown and titrated in CV-1 cells. Following the co-infection, 100 individual plaques were chosen and then subjected to a total of three rounds of plaque purification in CV-1 cells to obtain 100 clonally purified chimeric orthopoxviruses. High-throughput screening was used to compare the cytotoxic efficacy of these chimeric clones and the parental strains against the NCI-60 panel. CF33 was selected as the chimeric isolate which demonstrated superior cell killing in the NCI-60 panel when compared to all parental viruses and other plaque-purified isolates.

To generate CF33 expressing Fluc (CF33-Fluc), the Fluc expression cassette under control of the vaccinia virus H5 promoter was inserted into the thymidine kinase locus of CF33 via transient dominant selection as described previously.22 PCR and DNA sequencing confirmed the genotype of CF33-Fluc. In vitro luciferase activity was confirmed by plating 24-well plates with HCT-116 cells. Following a 24-hr growth period, cells were infected with CF33-Fluc at varying MOIs. Rapid luciferase activity was observed after 24 hr by adding 100× luciferin solution (prepared as below) directly to wells and imaging after 10 min with Lago X optical imaging system (Spectral Instruments Imaging, Tucson, AZ).

Cytotoxicity Assay

Human colorectal cancer cell lines HCT-116, SW620 and LoVo were plated at 3 × 103 cells per well in cell-specific media supplemented with 5% FBS and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution in 96-well flat-bottom plates. The following day, cells were infected with virus at MOIs 1, 0.1, and 0.01. For the next 8 days, cell survival was determined by comparing absorption of infected cells to mock-infected cells after 1 hr incubation with CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay per manufacturer protocol (Promega, Madison, WI).

Extracellular and Cellular Viral Growth

HCT-116 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and when 70%–80% confluent, cells were counted and infected at an MOI of 0.03 particle forming unit (PFU) per cell with the chimeric virus CF33 or cowpox (CPX) or different strains of vaccinia virus (western reserve [WR], IHD, Elstree, and Lederle) in a total volume of 0.5 mL medium containing 2.5% FBS. After 1 hr, inoculum was aspirated, and fresh medium was added to each well, and plates were returned to incubator. At the indicated times, cells were scraped into the medium and subjected to three rounds of freeze-thaw to ensure complete cell lysis and virus release. Viral titers in the lysates were determined by standard plaque assay. Lysates were serially diluted and used to infect 24-well plates of CV-1 cells. One hour after infection, 500 μL of medium containing 1% methyl-cellulose was added to each well. Forty-eight hours post-infection, 1 mL 0.5% (w/v) crystal violet was added to each well and the plates were left at room temperature overnight. Next day, the plates were washed and plaques were counted.

To compare the EEV form of viruses, HCT116 cells were infected as above and supernatants were collected from each well 12 and 18 hr post-infection. Virus titers in the supernatants were determined using plaque assay. Fold change in PFU/cell was calculated by normalizing the virus titers at different time points with the titers at 0 hours.

Xenografts In Vivo and Luciferase Imaging

Animal studies were performed under the City of Hope Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)-approved protocol. Twenty-one 6-week-old Hsd:Athymic Nude-Foxn1nu female mice (Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) were purchased and acclimatized for 1 week. Bilateral flank tumors were generated by injecting 5 × 106 HCT-116 cells in a total of 100 μL PBS containing 50% matrigel for each tumor. Mice were divided into four groups when average tumor size approached 150 mm3 to achieve approximately similar average tumor volume in each group at the onset of treatment. To analyze anti-tumor efficacy after i.t. delivery, five mice received an i.t. injection of 105 PFU per tumor of CF33-Fluc, and two mice received i.t. PBS. For i.v. treatment, eight mice received 105 PFU of CF33-Fluc, and four mice received PBS via tail-vein injection. Two and four mice treated with CF33-Fluc in the i.t. group and in the i.v. group, respectively, were sacrificed 10 days post-injection, while the remaining mice were observed to the termination of the experiment. Two mice in the i.v. group (one control and one treatment) were excluded from analysis due to severe ulceration of the tumors with weight loss requiring euthanasia. At the time of sacrifice, tumors and solid organs were harvested. Tissues were split into halves, with half snap-frozen for virus titration and the other half was formalin-fixed for immunohistochemical analysis. The remaining mice were sacrificed on day 50. In all groups, tumors were measured twice weekly with tumor volume, V (mm3) = (1/2) × A2 × B, where A is the shortest and B is the longest measurement. Percent tumor change was calculated based on initial tumor size at the time of intervention.

Fluc solution was prepared as per manufacturer’s instruction (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). Imaging was obtained after intraperitoneal delivery of luciferin in a control mouse and all mice treated with CF33-Fluc using Lago X optical imaging system (Spectral Instruments Imaging, Tucson, AZ) after 7 min incubation. Imaging was performed twice weekly and on day of sacrifice.

Immunohistochemistry

Tumors and vital organs obtained at sacrifice were formalin-fixed for 48 hr. Subsequently, paraffin embedding with 5-μm-thick sections was performed. H&E staining was done. On an abutting section, the slides were deparaffinized followed by heat-mediated antigen-retrieval per manufacturer protocol (IHC World, Ellicott City, MD). Tumor sections were then permeabilized with methanol and TNB Blocking Buffer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) was used to decrease background for 20 min. Rabbit anti-vaccinia virus antibody 1:100 in TNB blocking buffer (cat. #ab35219; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was added overnight in a humidified chamber at 4°C. The next day, tumor sections were secondarily stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (cat. #ab150077, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) for 1 hr at room temperature. Finally, DAPI was added and images were obtained using EVOS FL Auto Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (Version 7.01, La Jolla, CA). Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA were used to evaluate for statistical significance. p < 0.05 was considered significant. Where present in figures, error bars indicate SD.

Cell Death Analysis

TUNEL Assay

HCT 116 cells were plated at 2 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates. The following day, cells were infected with CF33-Fluc at MOI 5 PFU/cell. After 18 hr of infection, TUNEL assay was performed using In Situ Cell Death Detection kit (Roche; cat #11684795910) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were cultured in 60 mm Petri dish and were infected with CF33-Fluc virus at MOI 5 or mock infected. Cells were harvested 18 hr post-infection using trypsin and then stained for annexin V, PI, or Caspase-3 using the FITC Annexin V/Dead Cell apoptosis kit (cat. #V13242, Invitrogen) following manufacturer’s protocol. Stained cells were analyzed on a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

ATP Determination

Cells were infected at MOI 5 and were harvested at indicated time points. After harvesting the cells, protein was extracted and suspended in standard assay buffer containing luciferase and luciferin, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ATP Determination Kit; cat. #A22066, Invitrogen) and luminescence was measured with a TECAN microplate reader (Life Sciences). Immune cell death assays were performed as follows:

Calreticulin Staining

Cells were infected with CF33 or CF33-FLuc (MOI 5) for 16 hr.

1 × 106 cells were resuspended in PBS with 2% FBS and stained with isotype control (Abcam, EPR25A) or Anti-Calreticulin antibody (Abcam, EPR3924). After staining, FACS analysis was performed.

ATP Secretion

Cells were infected with CF33 or CF33-FLuc (MOI 5). After 16 hr incubation, supernatants were collected. ATP level in supernatant was measured by ATP Determination kit (Invitrogen) following manufacturer’s instructions.

HMGB1 Secretion

Cells were infected with CF33 or CF33-FLuc (MOI 5). Supernatants were collected at different time points and concentrated using a column with 10-kDa size cutoff. The concentrated supernatants were loaded (15 μL/well) for western blotting. HMGB1 was detected using a rabbit anti-HMGB1 antibody (cat. #ab18256; Abcam) at 1:500 dilution followed by an HRP-labeled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (cat. #ab205718; Abcam) at 1:5,000 dilution.

Author Contributions

M.P.O., S.-I.K., J.L., A.H.C., A.K.P., and S.C. performed the experiments. S.G.W., N.G.C., Y.W., and Y.F. designed the experiments. S.G.W. and M.P.O. wrote the manuscript. S.C. and S.-I.K. designed selected figures and added selected methods to the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this work are supported by the American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant MRSG-16-047-01-MPC.

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen G. [Interpretation of the updates of NCCN 2017 version 1.0 guideline for colorectal cancer] Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2017;20:28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirai K., Moriguchi K., Ohno Y. [Measurements of active oxygen by cytochemical demonstration procedures] Tanpakushitsu Kakusan Koso. 1988;33:2708–2716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell S.J., Federspiel M.J., Peng K.W., Tong C., Dingli D., Morice W.G., Lowe V., O’Connor M.K., Kyle R.A., Leung N. Remission of disseminated cancer after systemic oncolytic virotherapy. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014;89:926–933. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanziale S.F., Petrowsky H., Adusumilli P.S., Ben-Porat L., Gonen M., Fong Y. Infection with oncolytic herpes simplex virus-1 induces apoptosis in neighboring human cancer cells: a potential target to increase anticancer activity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:3225–3232. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adusumilli P.S., Eisenberg D.P., Stiles B.M., Chung S., Chan M.K., Rusch V.W., Fong Y. Intraoperative localization of lymph node metastases with a replication-competent herpes simplex virus. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2006;132:1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenberg D.P., Adusumilli P.S., Hendershott K.J., Chung S., Yu Z., Chan M.-K., Hezel M., Wong R.J., Fong Y. Real-time intraoperative detection of breast cancer axillary lymph node metastases using a green fluorescent protein-expressing herpes virus. Ann. Surg. 2006;243:824–832. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000219738.56896.c0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reid T., Warren R., Kirn D. Intravascular adenoviral agents in cancer patients: lessons from clinical trials. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002;9:979–986. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiocca E.A., Rabkin S.D. Oncolytic viruses and their application to cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014;2:295–300. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts K.L., Smith G.L. Vaccinia virus morphogenesis and dissemination. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:472–479. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith G.L., Vanderplasschen A., Law M. The formation and function of extracellular enveloped vaccinia virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2002;83:2915–2931. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-12-2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whilding L.M., Archibald K.M., Kulbe H., Balkwill F.R., Oberg D., McNeish I.A. Vaccinia virus induces programmed necrosis in ovarian cancer cells. Mol. Ther. 2013;21:2074–2086. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo Z.S., Naik A., O’Malley M.E., Popovic P., Demarco R., Hu Y., Yin X., Yang S., Zeh H.J., Moss B. The enhanced tumor selectivity of an oncolytic vaccinia lacking the host range and antiapoptosis genes SPI-1 and SPI-2. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9991–9998. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blasco R., Sisler J.R., Moss B. Dissociation of progeny vaccinia virus from the cell membrane is regulated by a viral envelope glycoprotein: effect of a point mutation in the lectin homology domain of the A34R gene. J. Virol. 1993;67:3319–3325. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3319-3325.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McIntosh A.A., Smith G.L. Vaccinia virus glycoprotein A34R is required for infectivity of extracellular enveloped virus. J. Virol. 1996;70:272–281. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.272-281.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ungerechts G., Bossow S., Leuchs B., Holm P.S., Rommelaere J., Coffey M., Coffin R., Bell J., Nettelbeck D.M. Moving oncolytic viruses into the clinic: clinical-grade production, purification, and characterization of diverse oncolytic viruses. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2016;3:16018. doi: 10.1038/mtm.2016.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thorne S.H., Kirn D.H. Future directions for the field of oncolytic virotherapy: a perspective on the use of vaccinia virus. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2004;4:1307–1321. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.8.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haddad D., Zanzonico P.B., Carlin S. A vaccinia virus encoding the human sodium iodide symporter facilitates long-term image monitoring of virotherapy and targeted radiotherapy of pancreatic cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2012;53:1933–1942. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.105056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haddad D., Chen C.H., Carlin S., Silberhumer G., Chen N.G., Zhang Q., Longo V., Carpenter S.G., Mittra A., Carson J. Imaging characteristics, tissue distribution, and spread of a novel oncolytic vaccinia virus carrying the human sodium iodide symporter. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gholami S., Chen C.H., Lou E., Belin L.J., Fujisawa S., Longo V.A., Chen N.G., Gönen M., Zanzonico P.B., Szalay A.A., Fong Y. Vaccinia virus GLV-1h153 in combination with 131I shows increased efficiency in treating triple-negative breast cancer. FASEB J. 2014;28:676–682. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-237222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russell S.J., Peng K.W., Bell J.C. Oncolytic virotherapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:658–670. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Falkner F.G., Moss B. Transient dominant selection of recombinant vaccinia viruses. J. Virol. 1990;64:3108–3111. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.3108-3111.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]