Abstract

Characterizing ensembles of intrinsically disordered proteins is experimentally challenging because of the ill-conditioned nature of ensemble determination with limited data and the intrinsic fast dynamics of the conformational ensemble. Amide I two-dimensional infrared (2D IR) spectroscopy has picosecond time resolution to freeze structural ensembles as needed for probing disordered-protein ensembles and conformational dynamics. Also, developments in amide I computational spectroscopy now allow a quantitative and direct prediction of amide I spectra based on conformational distributions drawn from molecular dynamics simulations, providing a route to ensemble refinement against experimental spectra. We performed a Bayesian ensemble refinement method on Ala–Ala–Ala against isotope-edited Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy and 2D IR spectroscopy and tested potential factors affecting the quality of ensemble refinements. We found that isotope-edited 2D IR spectroscopy provides a stringent constraint on Ala–Ala–Ala conformations and returns consistent conformational ensembles with the dominant ppII conformer across varying prior distributions from many molecular dynamics force fields and water models. The dominant factor influencing ensemble refinements is the systematic frequency uncertainty from spectroscopic maps. However, the uncertainty of conformer populations can be significantly reduced by incorporating 2D IR spectra in addition to traditional Fourier-transform infrared spectra. Bayesian ensemble refinement against isotope-edited 2D IR spectroscopy thus provides a route to probe equilibrium-complex protein ensembles and potentially nonequilibrium conformational dynamics.

Introduction

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) exhibit a variety of thermally accessible conformers reflecting basins on a complex energy landscape that are also characterized by dynamics such as conformational fluctuations and activated kinetics of interconversion between free-energy basins (1, 2, 3). As a result, structural characterization of IDPs or proteins with intrinsic disordered regions requires an ensemble description, which creates numerous experimental challenges (4, 5). In particular, ensemble-structure determination is naturally an ill-posed problem in which the degrees of freedom in relevant conformational states far exceeds the limited number of measurements and information content of experiments (6).

The dynamic nature of the ensemble also means that structural variation and conformational dynamics cannot be decoupled. Traditional structural tools are often limited by their intrinsic time resolution, which prohibits one from accessing conformational fluctuations and interconversion of conformers with timescales spanning from picoseconds to microseconds (4, 7, 8). For example, measuring chemical shifts or J-couplings in NMR spectroscopy is limited by the coalescence timescale of ms such that faster conformational dynamics are averaged (9). Optical spectroscopies do carry the advantage of femtosecond timescales for their light-matter interaction but in most cases have little or no structural information content. On the other hand, infrared (IR) and two-dimensional (2D) IR spectroscopies probe structures sensitive to molecular vibrations with fs‒ps time resolution, which can be used to carry out structural characterization on a peptide or protein structure that is essentially frozen (10, 11, 12, 13). The 2D IR spectrum represents a correlation map between different vibrational modes by spreading the spectrum onto independent excitation- and detection-frequency axes. This enhances the structural information content of vibrational spectra, providing higher contrast and characterizing inhomogeneous distributions that result from a static structural distribution.

With this goal in mind, we have been developing tools for protein and peptide structural characterization using 2D IR spectroscopy of amide I vibrations, which result primarily from the C=O stretching vibration of the protein backbone amide group. Amide I spectroscopy can be used to sense local electrostatics, hydrogen bonding to the carbonyl, and secondary structures of proteins (12). However, the vibrational lifetime of 1–1.3 ps significantly broadens the amide I peaks (14, 15), lowering the structural resolution with highly congested amide I spectra (16). Enhanced structural information can be achieved by using various polarizations of ultrafast infrared pulses (17) and introducing site-specific isotope labeling such as 13C or 13C18O on the amide carbonyl, which provides an additional frequency shift to isolate a specific C=O bond from a congested spectrum, allowing the extraction of local structural details (18, 19). The structural sensitivity of amide I vibrational and site-specific isotope labeling has assisted in addressing the conformational distributions of peptides and proteins (5, 20, 21, 22), helix-coil transition dynamics (23, 24, 25), and the ion-permeation mechanism of ion channels (26, 27).

Despite intensive experimental advances to investigating protein structures, all experimental methods are challenged to interpret their measurement. Therefore, it remains of great interest to make use of atomistic models such as molecular dynamics (MD) simulation to offer atomistic or coarse-grained descriptions of protein structures and motions, which can rationalize experimental evidence, predict experimental outcomes, and even help design suitable experiments. However, these computational tools often suffer from a separate set of challenges, including limited sampling of rare events due to the gap between computationally accessible timescales and the timescale of conformational dynamics, that hinder the accuracy of predicted ensemble distributions. Also, the recent efforts of force field (FF) developments have improved the ability to study disordered proteins (28), but the question of how much the uncertainty from FFs and water models affects the ensemble predictions of IDPs and proteins with intrinsic disordered regions quantitatively still remains (29, 30, 31, 32, 33). A practical approach using ensemble refinement, which reweights existing ensemble populations from simulations against experimental data, has proven successful for facilitating the inference of protein conformational ensembles consistent with experiments (6), including developing different frameworks such as the maximum entropy (ME) principle (34, 35, 36, 37, 38), Bayesian statistics (39, 40, 41), and biological applications against experimental data such as NMR (6, 42), small angle x-ray scattering (43, 44), and IR spectroscopy (5, 45). A recent detailed review of ensemble structure determination can be found in (4).

Making direct comparisons of a protein or peptide structure with IR experiments is now possible using computational amide I spectroscopy. This method can be used to predict IR and 2D IR spectra for a single structure or simulated conformational distributions drawn from MD trajectories, providing a route to ensemble refinement against IR experiments (46). Specifically, amide I spectroscopic maps predict amide I vibrational frequencies to high accuracy using local electrostatics calculated from MD simulations such as electrostatic potential or electric field at the site of interest (47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54). Maps for vibrational coupling between different amide I vibrations are used to calculate the interaction of multiple backbone amide groups (55, 56, 57, 58, 59). These maps have reached the point of predicting amide I spectroscopic observables to a high level of accuracy with 2 cm−1 frequency uncertainty (53) and provided a direct way to refine conformational ensembles of proteins.

As part of our effort to develop tools for refining protein and peptide conformational ensembles, we recently applied the ME method to elastin-like peptides (ELPs) to refine the ELP ensembles against isotope-edited Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (5), drawing structures from multiple FFs. Although this proved effective for describing the extension in a type-I turn in these peptides, the ME method is not readily extended to more complex features such as multiple overlapping resonances and asymmetric spectral line shapes. Additionally, the ME framework requires that the constraints are strictly satisfied after the refinement, which may lead to biased refinement or poor convergence if the experimental constraints are chosen improperly or if uncertainties exist in the experiment (such as noise or signal bias). To make use of the added information content of 2D IR spectroscopy and generalize this method to account for arbitrary spectral line shape, we have implemented a Bayesian ensemble-refinement framework against multiple experimental IR spectra using FTIR and 2D IR spectroscopy, with the ability to integrate other experimental techniques.

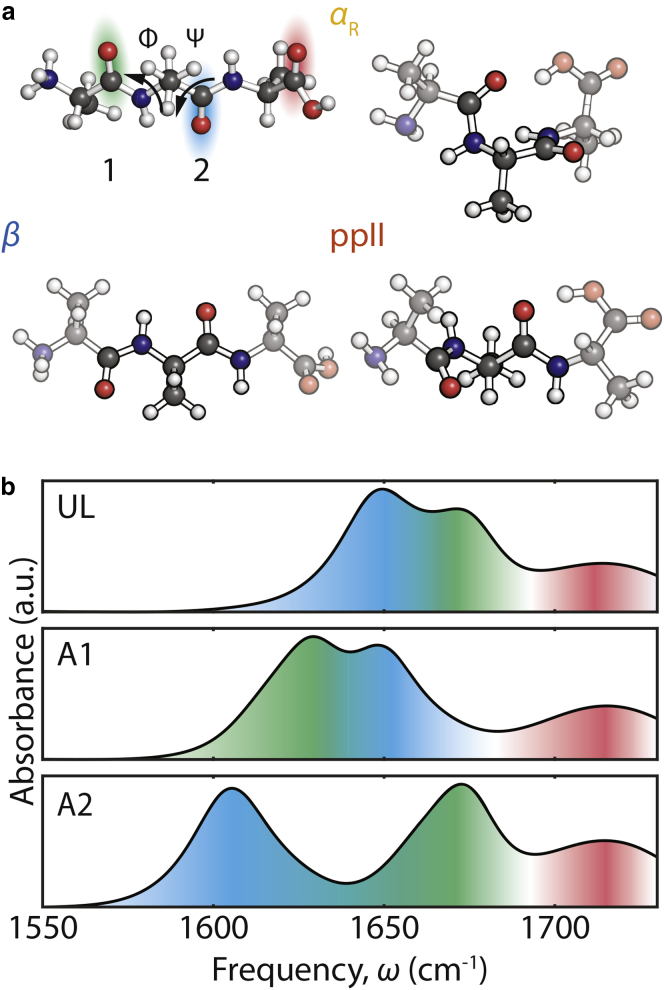

As a proof-of-principle study, ensemble refinement against isotope-edited FTIR and 2D IR spectroscopy is performed on Ala‒Ala‒Ala (AAA), because the backbone conformational variation of AAA has been well characterized to contain mostly ppII conformer (Fig. 1 a) using various experimental approaches including NMR, vibrational circular dichroism, and 2D IR spectroscopy (60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65). Additionally, ensemble determination based on a Bayesian framework has been applied on AAA using NMR data, and it has been demonstrated that sufficient experimental data can lead to converged populations of conformers from various FFs (39, 40). AAA conformational variation is simple enough to investigate the capability of ensemble refinement against 2D IR spectroscopy and the factors influencing the quality of refining conformational ensemble of peptides and proteins. This study will help us consolidate the foundation of methods of refining protein conformational ensembles against isotope-edited 2D IR spectroscopy and enable the potential of globally constraining a description of an IDP ensemble against multiple isotope-edited samples.

Figure 1.

(a) Structure of cationic AAA and the dominant conformers αR ((ϕ,ψ) = (−60°,−40°)), β ((ϕ,ψ) = (−135°,135°)), and ppII ((ϕ,ψ) = (−70°,150°)). The amide I vibrations of the A1 and A2 sites are color-coded green and blue, respectively, and the C=O stretch of the COOD group is color-coded red. (b) FTIR spectra of UL AAA, A1-labeled AAA, and A2-labeled AAA are shown using the same color coding. To see this figure in color, go online.

Materials and Methods

Solid-phase peptide synthesis of Ala-Ala-Ala

1‒13C-labeled alanine was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Tewksbury, MA) and fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc)-protected using N-(9-Fluorenylmethoxycarbonyloxy)succinimide in the presence of NaHCO3 in a dioxane-water mixture. These building blocks were used in synthesizing (1‒13C)Ala‒Ala‒Ala (A1-labeled AAA) and Ala‒(1‒13C)Ala‒Ala (A2-labeled AAA) by manual Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis. All peptides were synthesized on a 0.1 mmol scale with 5.5-fold excess of Fmoc-protected amino acids (0.55 mmol) and hexafluorophosphate benzotriazole tetramethyl uronium (0.5 mmol) in the presence of N,N-diisopropylethylamine in dimethylformamide (DMF). Nα-Fmoc protecting groups were removed by treating the resin-attached peptide with piperidine (20% v/v) in DMF. Fmoc-(1‒13C)Ala was coupled by using a minimal amount of the isotope-labeled amino acid: Fmoc-AA (0.35 mmol), hexafluorophosphate benzotriazole tetramethyl uronium (0.3 mmol), and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (0.6 mmol) in DMF for 1 h. After peptide-chain assembly was completed, the peptide resin was subjected to Nα-Fmoc deprotection by treating it with 20% v/v piperidine/DMF. The crude peptide was then cleaved from the 2-chlorotrityl-(styrene-divinylbenzene) resin by treatment with trifluoroacetic acid/triisopropylsilane/water (95:2.5:2.5 v/v) conditions at ambient temperature and worked up by precipitation from ice-cold ether. Unlabeled (UL) AAA was synthesized by the same procedure, except that UL alanine was used as building blocks. Detailed procedures for the synthesis of amino-acid building blocks, peptide synthesis, purification, and characterization by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry are provided in the Supporting Materials and Methods.

Sample preparation

Trialanines were iteratively dissolved in 1 M DCl/D2O and lyophilized to remove residual trifluoroacetic acid, whose absorption overlaps with amide I absorption. For IR measurements, AAAs were dissolved to a concentration of 130 mM (30 mg/mL) in 1 M DCl/D2O to avoid spectral overlap between amide I vibrations and H2O bend vibration and to protonate the carboxyl terminus to shift its carbonyl vibration to ∼1720 cm−1. Under this condition, AAA is cationic, or ND3+‒Ala‒Ala‒Ala‒COOD. Although we report amide I′ spectra, for simplicity, we use the terms amide I and amide I′ interchangeably throughout this study. For all of the IR measurements, samples were held between two 1-mm-thick CaF2 windows spaced by a 50-μm Teflon spacer.

FTIR spectroscopy

FTIR spectra were collected at room temperature using a Bruker Tensor 27 FTIR spectrometer (Billerica, MA) with 64 averages at 2 cm−1 resolution. A background spectrum of 1 M DCl in D2O was measured for subtracting the solvent vibrational profile from the sample spectrum. A linear baseline correction from 1550 to 1800 cm−1 was applied to flatten the baseline of the subtracted sample spectrum. For comparing spectra with simulations, we also subtracted the C=O resonance from the terminal COOD group by fitting all peaks with Gaussians and subtracting the COOD peak. To avoid bias due to baseline drift, an ∼70 cm−1 logistic window smoothing is applied on spectra from both experiments and simulations. The subtracted experimental spectra and the window function are shown in Fig. S10.

2D IR spectroscopy

Absorptive 2D IR spectra record the change of optical density at the detection frequency corresponding to a particular excitation frequency, serving as a correlation map between vibrational modes. 2D IR spectra were acquired in a pump-probe geometry 2D IR spectrometer at room temperature described elsewhere (66), and details are provided in the Supporting Materials and Methods. The waiting time was set to 0.15 ps for 2D IR spectra. The 2D IR spectra were collected with both parallel polarization and perpendicular polarization. We also present transient absorption (TA) spectra, which are obtained by projecting the absorptive 2D IR spectrum onto the detection frequency axis. The frequency resolution of the detection frequency axis is 4 cm−1.

MD simulations

Details of the MD simulations are described in the Supporting Materials and Methods. Briefly, cationic AAA simulations were performed using GROMACS 4.6.7 package (67). The FFs used were CHARMM27 (C27) (68, 69), CHARMM36 (C36) (70), CHARMM36m (C36m) (71), OPLS-AA (72, 73), OPLS-AA/M (74), AMBER99sb‒ildn (75), AMBER14sb (76), and AMBERfb15 (77). The water models used were SPC/E (78) and TIP3P (79) for all FFs. An additional TIP3Pfb (80) water model was used specifically for AMBERfb15, resulting in 17 combinations of FFs and water models. Because AMBER FFs do not have parameters for a protonated COOH group, we instead use a CONH2 group at the C-terminus, which affects the electrostatics and the frequencies of the two amide groups (see the Supporting Materials and Methods) but may not notably influence the conformational ensemble (81). 100-ns production runs using the Nose-Hoover thermostat (82, 83) were simulated with 1-fs integration step and 20-fs/frame sampling rate for amide I spectral simulations. The sampling quality is investigated by the block averaging method (see the Supporting Materials and Methods). The MD structural data analysis of backbone dihedral angles ϕ and ψ was performed using PLUMED 2 (84). The potential of mean force (PMF) of each MD trajectory is computed by using PMF(ϕ,ψ) = −kBT ln P(ϕ,ψ), in which P(ϕ,ψ) is the probability distribution of AAA as a function of (ϕ,ψ) at T = 300 K.

Amide I spectral simulation

IR vibrational spectra of the two coupled amide I vibrations of the AAA peptide backbone were calculated from the Fourier transform of a dipole time-correlation function using a mixed quantum-classical model. Details of this spectral simulation strategy using a coupled oscillator (exciton) model have been described previously (15, 46, 53), and the home-built programs used in these calculations, g_amide and g_spec, are freely available (85, 86). Collective electrostatic variables are used to translate, or “map,” a series of instantaneous structures along MD trajectories into a time-dependent Hamiltonian and transition dipole moment that describe the two amide I vibrations. The two amide oscillators, or “sites,” are identified by the atomic positions of the CONH peptide backbone linkages. The vibrational frequency of each site is generated using one of two empirical frequency maps that correlate the collective variable with a specific vibrational frequency: the one-site electric field map that uses the electric field created by the local environment at the amide oxygen projected along the C=O bond, and the four-site potential map, which uses the electrostatic potential at the C, O, N, and H positions (53). Unless mentioned, the spectroscopic map used throughout this study is the one-site map, which has a frequency prediction accuracy of σ = 2 cm−1 (53). To calculate these electrostatic parameters across multiple FFs and water models, we use CHARMM FF charges with modified glycine charges and TIP3P charges in this study (53).

In addition to the frequency of each site, the vibrational coupling between the two amide oscillators is obtained with a second map. Through-bond coupling between adjacent sites is generated by the density functional theory (DFT)-based nearest-neighbor coupling map, and through-space coupling is computed by a transition charge coupling map (57). Note that our calculations do not account for the C=O stretch of the terminal COOH group.

We performed amide I spectral simulations by calculating a response function from dipole-correlation functions using a dynamic wavefunction-propagation method (87). In this study, we implemented a new Trotter expansion to reduce computation time (86, 88) while maintaining errors at less than 1% (Fig. S11). The window time for calculating response functions was set to 11 ps, equivalent to 3-cm−1 frequency resolution, which is comparable to our frequency map errors of 2 cm−1 (53). The anharmonicity of the amide I oscillator is set to 16 cm−1, determined experimentally (89). The model includes a vibrational lifetime for amide I modes, which is set as a 1.0 ps exponential decay to match the lifetime measured in our transient absorption experiment of AA (15). The 1‒13C isotope-frequency shift is set to 40 cm−1, obtained from FTIR experiments of AAA.

For ensemble refinement, we assume a separation of timescales between the large amplitude conformational dynamics of the peptide and the fast fluctuations that give rise to the spectral line shape. Spectra were calculated for 1000 conformational substates, obtained by splitting the full 100-ns trajectories into 100-ps short trajectories. For the time-averaged response function of each subensemble, a moving average was applied by separating the starting frame every 0.5 ps, resulting in 200 realizations for each subensemble.

Bayesian ensemble refinement

Under the assumption that MD simulations should provide a reasonable sampling of possible configurations, but that the corresponding distribution may deviate from the true ensemble because of inaccuracies in FFs and water models, we used a Bayesian ensemble-refinement scheme to reweight existing ensemble populations to be consistent with experimental data (90). Bayes’ theorem states that the posterior distribution based on experimental data p(x | data) follows

| (1) |

In Eq. 1, the prior distribution p(x) corresponds to a subensemble x generated from a spectral simulation with uniformly distributed probabilities. The likelihood function p(x | data) describing the probability of reproducing experimental data by x is formulated as follows.

| (2) |

| (3) |

si(x) is the spectral overlap quantifying the similarity between the simulated spectra from x, , and the spectrum from experiment, (91). Here, i refers to a specific type of experimental spectrum. We draw from a total of 15 different types of linear and nonlinear IR experimental spectra, including traditional FTIR spectra, diagonal slices through 2D IR spectra, and TA spectra (a projection of the 2D spectrum). Representative values of si(x) are 1 for identical spectra, 0 for nonoverlapping spectra, and −1 for identical but opposite-signed spectra. If is identical to , then the measure of error and p(x | data) = 1, meaning that there is no need to refine the probability at all. All the other cases would reduce p(x | data) depending on θ, an adjustable parameter expressing the level of confidence in the model, and 1/θ is equivalent to the Lagrange multiplier in the ME formalism (90). Large θ reflects high confidence in the model, whereas smaller θ would refine the prior distribution against the experimental data more. The optimal value of θ can be determined by the L-curve method (90, 92), with detailed descriptions in the Supporting Materials and Methods. The correlation between the optimal value of θ and the relative accuracy of the FFs and water models is discussed in the Supporting Materials and Methods. The uncertainty σi is set to 2 cm−1 to account for errors from the spectroscopic maps (53).

Results

Experimental amide I spectra

Infrared spectra were acquired on three isotopologues of AAA: the natural abundance unlabeled form, Ala‒Ala‒Ala (UL), and two singly 13C-labeled peptides, (1‒13C)Ala‒Ala‒Ala (A1) and Ala‒(1‒13C)Ala‒Ala (A2). At low pH in D2O, the peptides exist in the fully protonated form: ND3+‒Ala‒Ala‒Ala‒COOD. In Fig. 1 b, the experimental FTIR spectrum of UL shows two distinct amide I peaks centered at 1650 and 1671 cm−1 and a weak peak centered at 1714 cm−1 from the C=O stretch of the carboxyl group. Based on the spectra of A1 and A2 shown in Fig. 1 b, the 13C label shifts one of the amide I peaks, whereas the other amide I peak is virtually unchanged, but the relative intensities of the two peaks change upon isotopic substitutions. Based on this observation, we conclude that the peaks at 1671 and 1650 cm−1 in the UL spectrum originate from the amide I mode at the A1 and A2 positions, respectively. The frequency difference between these amide I modes in the UL spectrum results from a blue shift of A1 stemming from its proximity to the positively charged ND3+ group, as suggested by previous studies (61, 93). The slight intensity variations of these peaks can be rationalized on the basis of a coupled oscillator model, described in the Supporting Materials and Methods.

The isotopic frequency shift to the amide I vibration resulting from the 13C label can also be unambiguously determined from these spectra. From the coupled oscillator model, the 12C-to-13C isotopic frequency shift Δ can be expressed as , where and refer to the average of the two peak frequencies from the singly 13C-labeled spectrum and the UL spectrum, respectively. Both A1 and A2 spectra give a consistent isotope frequency shift of 40 cm−1 in line with previous measurements (18, 19), which is used in our spectral simulations.

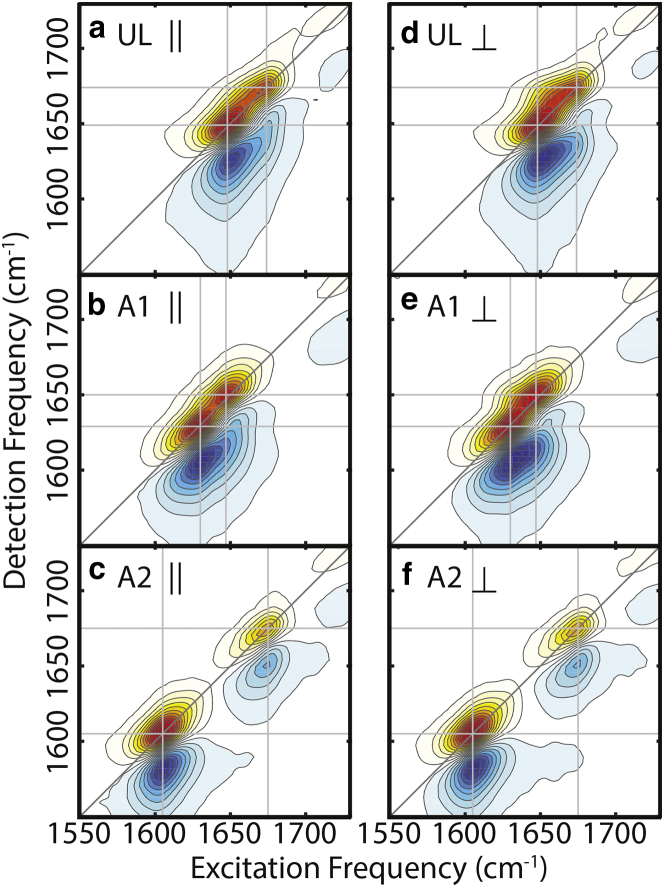

Fig. 2 a presents 2D IR spectra of the three AAA isotopologues under parallel and perpendicular polarization conditions. A 2D IR spectrum is a correlation map between the vibrational excitation frequency and detection frequency, and thus provides more information than FTIR spectra, such as a 2D line shape that reflects the underlying broadening mechanisms and crosspeaks indicating coupling between vibrational modes. Each resonance in the 2D spectrum is a positive/negative (red/blue) doublet, which represents the ground state bleach of the 0–1 quantum transition and excited-state absorption from the 1–2 quantum transition. The detection frequencies of these transitions differ as a result of the anharmonicity of vibrations. The 2D spectra in Fig. 2 a are diagonally elongated, characteristic of inhomogeneous broadening arising from variations in the conformation of AAA and the variable solvation environments around the amide groups.

Figure 2.

Experimental parallel-polarized (∥) 2D IR spectra of (a) UL AAA, (b) A1-labeled AAA, and (c) A2-labelled AAA. (d–f) Experimental perpendicular-polarized (⊥) 2D IR spectra of (a) UL AAA, (b) A1-labeled AAA, and (c) A2-labeled AAA. The intensity of each spectrum is normalized to the maximal peak intensity. To see this figure in color, go online.

Additional features of the 2D spectra are found in the crosspeaks between amide I modes and the C=O stretch, which are sensitive to the relative orientation of the vibrational transition dipoles and hence the conformation of the peptide backbone (60, 61). Although the crosspeaks between amide I modes at (1649, 1674 cm−1) in the UL spectra and at (1630, 1650 cm−1) in the A1-labeled spectra are not apparent in the parallel polarization between the excitation pulses and the detection pulse relative to the diagonal, they appear slightly more intense in the perpendicular polarization. From the crosspeaks, the coupling between amide I modes is estimated to be <8 cm−1, assuming the weak-coupling limit (14), consistent with previous 2D IR studies of UL and 1‒13C-labeled AAA (60, 61). Because there is no significant crosspeak between the amide I vibration and the C=O stretch of the terminal COOD in any 2D IR spectra, we conclude that this coupling is weak enough to be neglected in our amide I spectral model, consistent with our previous finding for dialanine (15).

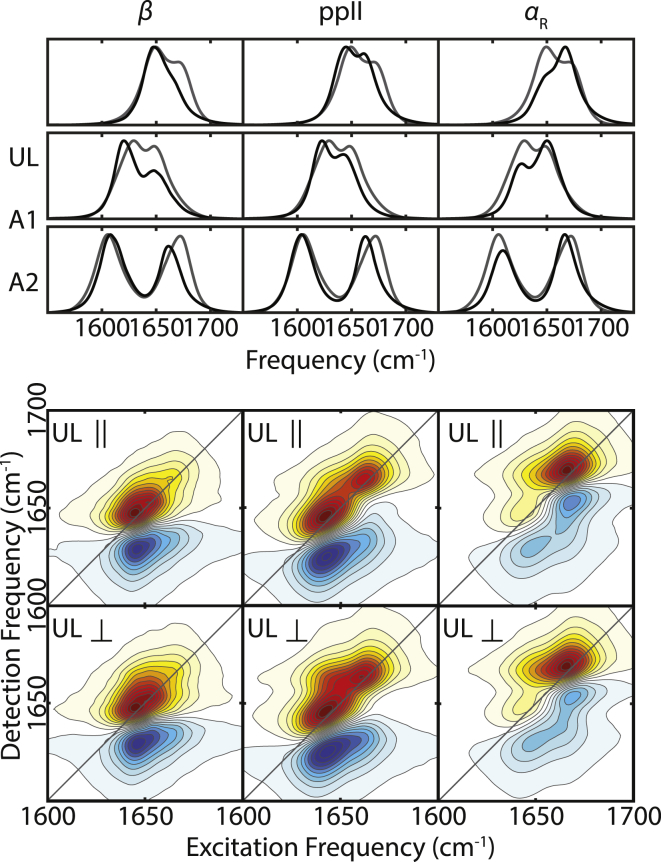

Effect of conformational variations on amide I spectra

To investigate how the variation of conformational distributions affects the amide I spectra, we simulated amide I spectra of AAA using C27, C36, and C36m FFs with SPC/E water. One difference between these FFs is the energy correction map, CMAP, which adjusts dihedral angle preferences. C27 is known for a significant bias toward α-helical conformations (29), whereas C36 corrects this bias. Additional refinement in C36m adjusts the propensity of the left-handed α-helical basin (αL) to better describe IDPs (70, 71). Thus, this series of CHARMM FFs provides a useful exploration of how differences in α-helical content affect the amide I spectra. PMFs of AAA for the three FFs are shown as a function of backbone dihedrals in Fig. 3, identifying the dominant conformational basins: β around (ϕ,ψ) = (−150°,150°), ppII around (ϕ,ψ) = (−60°,150°), αR around (ϕ,ψ) = (−70°,−50°), and αL around (ϕ,ψ) = (50°, 50°). A listing of population fractions in these states for all FF/solvent model combinations is given in Table S4. From Fig. 3, we see that α conformations are noticeably shallower in C36 relative to C27, corresponding to a decrease of αR population from 29% in C27 to 7% in C36 and 2% in C36m. Total populations of αL are always less than 4%, indicating that they contribute little to spectral simulations. Simulated IR spectra for the three isotopologues using the full trajectory from these FFs are shown in Fig. 3. Although these peak frequencies show only a subtle 1–2 cm−1 blue shift, we observe a decrease in intensity of the higher frequency peak from C27 to C36m, indicating that αR conformers contribute to the intensity of this peak and that the amide I spectra are sensitive to the underlying conformational distribution.

Figure 3.

(Left) PMF(ϕ,ψ) computed from C27 SPC/E, C36 SPC/E, and C36m SPC/E trajectories. Contours are spaced by kBT up to 6 kBT. The colored boxes represent the definitions of conformer basins β (light blue), ppII (red), and αR (green). (Right) FTIR spectra of UL, A1, and A2-labeled AAA from the experiment (gray) and from the C27, C36, and C36m trajectories are shown. The intensities of the simulated spectra are normalized to the maximal peak intensity of the experimental spectrum. To see this figure in color, go online.

To describe the correlation between AAA conformations and amide I spectra, we decomposed the ensemble-averaged spectra into spectra for conformers β, ppII, and αR. The conformational states, defined by the colored-box boundaries in Fig. 3, correspond to common definitions (17, 29, 94), with small FF-dependent shifts to the β-ppII boundary (Fig. S12). Full details are described in the Supporting Materials and Methods. The resulting averaged conformer spectra (Fig. 4) show relatively small differences in their FTIR spectra, mainly a difference in the relative intensities of the two amide I peaks. By defining the intensity ratio of the higher to the lower frequency peak, , we find a clear trend in the variation of peak-intensity ratio with structure as . The effects are much clearer in 2D IR spectra, in which the conformers are clearly distinguished either by the frequency of one dominant peak at 1648 cm−1 for β or 1669 cm−1 for αR or as the presence of two peaks for ppII. Head-to-head comparisons of peak intensities between the conformer spectra and the experimental spectra in Fig. 4 lead to the qualitative conclusion that the AAA conformational ensemble consists mostly of conformers in the ppII basin, with some population in the β basin but no substantial population in the αR state.

Figure 4.

(Top) FTIR spectra from the experiments (gray) and FTIR spectra of conformers from the C27 SPC/E simulation (black). The intensity of each conformer spectrum is normalized to the corresponding experimental spectrum. (Bottom) Parallel-polarized and perpendicular-polarized 2D IR spectra of the conformers are shown. The intensity is normalized to the maximal peak intensity. To see this figure in color, go online.

Conformers can also be distinguished through differences in their peak frequencies, as summarized in Table S2. Although the relationship of peak frequency with structure is not trivial, we observe that the peak frequency from the A2 amide follows the trend . Also, for the peak from the A1 unit, the frequency is always highest for the αR conformers.

Ensemble refinement against amide I spectroscopy

Our objective in this study is to test an ensemble refinement scheme that can be used to account for complex spectral features such as those found in FTIR and 2D IR spectra. In our recent study of ELPs, the ME refinement is proved effective for describing the extension in a type-I turn across multiple FFs (5). However, the constraints of mean frequency and variance of a spectrally isolated peak is not easily extended to more complex features such as multiple overlapping resonances and asymmetric spectral line shapes. Additionally, the ME framework requires that the constraints are strictly satisfied after the refinement, which may lead to biased refinement or poor convergence if the experimental constraints are chosen improperly or if uncertainties exist in the experiment (such as noise or signal bias). To incorporate information from multiple experiments and generalize the refinement method to arbitrary spectral line shapes, we apply a Bayesian framework using the spectral overlap function defined in Eq. 3 as the new refinement metric (91). The Bayesian framework is naturally suitable for updating the posterior probability distribution when given new experimental information, and constraints need not be matched exactly.

Although 2D IR spectra are sensitive to the underlying conformations, refining AAA conformational ensembles against spectra in two full frequency dimensions is computationally intensive. Therefore, for refinement, we reduced the dimensionality of the spectra in two ways: 1) taking diagonal slices through the 2D IR spectrum, in which the excitation and detection frequencies are equal; and 2) using TA spectra, a projection of the 2D IR spectrum onto the detection-frequency axis. Because the crosspeaks in this AAA case are insensitive to the underlying conformations (Fig. 4), using TA spectra and diagonal slices are reasonable simplifications. These spectra still contain constraints that are unique to the 2D IR spectrum and distinct from the FTIR spectrum, but in the cases in which crosspeaks were more pronounced, additional slices including the crosspeaks could be used.

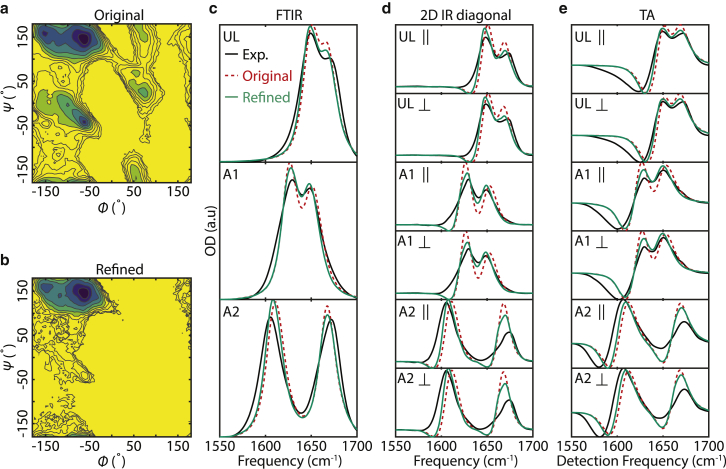

An example of ensemble refinement of the C36m TIP3P trajectory simultaneously against all forms of IR spectra for all three isotopologues is shown in Fig. 5. Qualitatively, the frequency and intensity changes in refined FTIR spectra (Fig. 5 c), 2D IR diagonal slices (Fig. 5 d), and TA spectra (Fig. 5 e) generally agree better with experiments, and this is borne out in the calculated spectral overlap changes in refinement (Fig. S13). Comparing the PMFs before and after the refinement (Fig. 5, a and b) indicates that the refined ensemble is mostly conformers in the ppII basin (86%) with a smaller fraction in the β basin (14%) and a negligibly small amount in other states. However, even with the constraints of 15 independent spectra, simulated spectra do not match the experiments exactly. There are many contributing factors to this mismatch, including errors or uncertainty in the spectroscopic map and FF and inadequate structural sampling. Although the spectral overlap values of FTIR spectra do not increase much after the refinement (Fig. S13), the overlap of simulated 2D IR diagonal slices and TA spectra with the experiments improves significantly, indicating that 2D spectra provide more stringent ensemble refinement constraints than FTIR.

Figure 5.

AAA ensemble refinement of C36m/TIP3P trajectory against infrared spectra. The PMF(ϕ,ψ) of C36m TIP3P trajectory before (a) and after (b) ensemble refinement is shown. The colored contours are spaced by kBT up to 6 kBT, whereas black contour lines extend to 10 kBT. (c–e) The spectra used for the ensemble refinement are shown, including FTIR spectra (c), diagonal slices (d), and TA spectra (e) from the experiments (black), simulation before refinement (dashed red), and simulation after refinement (solid green). To see this figure in color, go online.

The consistency of Bayesian ensemble refinement against IR spectra across different prior distributions was examined by comparing the results from 17 combinations of FFs and water models. Fig. 6 illustrates the fraction of the population in ppII, β, and αR states for all FF/water models before refinement and the corresponding population fractions obtained after refinement. Before refinement, all FFs consistently predict the highest populations in ppII, but otherwise the original ensemble populations vary by nearly 30% among these FFs and water models and predict an average of 12% of the population in the αR basin. However, the refined ensembles are more consistent, predicting ppII as the largest population (85% on average) with the rest mostly β conformer and negligible αR population in any ensemble. Thus, all FF/water combinations overestimate the population of the αR basin and underestimate the population of the ppII basin based on comparison with our IR spectra. Also, the refined distributions of populations among these FFs and water models become narrower than the original distributions, indicating that Bayesian ensemble refinement against amide I spectra gives a consistent trend across many combinations of FFs and water models. The mean populations and the standard deviations of these conformers are summarized in Table 1 with other structural studies of AAA, and a complete list of populations before and after refinement is given in Tables S4 and S5.

Figure 6.

(a–c) Histogram of the original population percentage of (a) β conformer, (b) ppII conformer, and (c) αR conformer. (d–f) A histogram of the refined population percentage of (d) β conformer, (e) ppII conformer, and (f) αR conformer is shown. The histograms are constructed from 17 combinations of FFs and water models listed in Table S4. To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 1.

Average and SD Record in Parentheses of the Conformer Population Distributions Before Refinement, After Refinement, and Other Studies of AAA

| Conformational State Populations |

Method | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | ppII | αR | αL | ||

| This study | 22% (7%) | 63% (11%) | 12% (8%) | 3% (2%) | MD simulations |

| Original | |||||

| Refined | 14% (5%) | 85% (6%) | 1% (2%) | <0.1% | Bayesian ensemble refinement against FTIR and 2D IR |

| Woutersen et al. (62) | 0% | 80% | 20% | 0% | Fitting 2D IR spectra |

| Schweitzer-Stenner (63) | 16% | 84% | 0% | 0% | Fitting VCD, Raman, FTIR, and J-coupling |

| Graf et al. (64) | 8% | 92% | 0% | 0% | Fitting to NMR |

| Oh et al. (65) | 12% | 88% | 0% | 0% | NMR with Gromos 43A1 |

| Xio et al. (40) | 2.0% (1.8%) | 85.8% (4.9%) | 5.5% (4.1%) | 3.5% (2.7%) | NMR data with integrated Bayesian approach |

| Beauchamp et al. (39) | 23% (6%) | 67% (9%) | 10% (8%) | – | Bayesian energy landscape tilting |

Discussion

We have tested a Bayesian ensemble-refinement protocol that draws from MD trajectories to simulate amide I spectra of site-specifically isotope-labeled peptides. Structure-based spectral modeling of amide I vibrations draws from MD simulations to sample structures of peptide and solvent that predict IR frequencies, intensities, and line shapes. Combining a series of linear and nonlinear IR spectra on several peptide isotopologues provides multiple constraints that can be self-consistently analyzed. Our test of this procedure on AAA shows that the changes of amide I peak frequency and intensity can distinguish conformational basins within the AAA energy landscape and be used to describe the underlying conformational distribution in heterogeneous ensembles. IR and 2D IR spectra reveal that AAA contains mostly conformations in the ppII basin and some portion of conformations in the β basin, which is consistent with many previous studies (39, 40, 62, 63, 64, 65). This is also quantitatively supported by Bayesian ensemble refinement across 17 combinations of FFs and water models. The results highlight the potential of amide I IR and 2D IR spectroscopy as a tool for ensemble refinement of peptides and proteins and provide a rigorous statistical framework for interpreting the underlying conformational distribution.

This study also identified several avenues for improvement and various challenges for describing conformational distributions quantitatively and accurately with IR spectroscopy. In implementing this refinement strategy, results may be influenced by multiple possible sources of error or bias beyond uncertainty in the experimental spectra, including inaccuracy in FFs and water models, inadequate sampling, and errors in the underlying spectroscopic models. Additionally, the outcome may also be affected by the choice of which type of experimental spectra used. In the following, we describe our analysis of how these factors affect the Bayesian ensemble refinement and interpretation of the underlying conformational ensemble.

Effect of experimental input on ensemble refinement

Using different experimental inputs will influence the regularization used to refine the simulated prior ensemble. To investigate the correlation between the refinement quality and experimental input, we compared ensemble refinements of C36m TIP3P and C27 SPC/E trajectories against 1) a single UL FTIR spectrum, 2) three FTIR spectra of all isotopologues, 3) six 2D IR diagonal slices for all isotopologue/polarization combinations, 4) six TA spectra of all isotopologue/polarization combinations, and 5) the full set of 15 spectra in Fig. 5. Fig. 7 summarizes the refined population ratios obtained by these five sets of restraints, showing a clear decrease in the error bars for the refined populations as more restraints are added. Refinement purely on FTIR data gave the poorest agreement, with the worst case being 55% error bars in the ppII and αR populations using the C27 SPC/E initial ensemble. However, significant improvements are obtained by using nonlinear spectra (2D diagonal slices or TA spectra), indicating that 2D IR spectroscopy provides a more stringent constraint than FTIR. TA spectra generally give a narrower uncertainty than the diagonal slice because of additional information of the excited-state absorption present in the TA spectra.

Figure 7.

Effect of different experimental information on the ensemble refinement. The refined population percentage of conformers against various inputs of experiment spectra from (left) C36m TIP3P trajectory and (right) C27 SPC/E trajectory with postfrequency correction is given. The inputs for the refining ensemble include UL FTIR, full FTIR spectra, all of the diagonal slices, all of the TA spectra, and the entire set of spectra. The colored error bars reflect the ±2σ uncertainty due to the spectroscopic map, determined by the maximal and the minimal populations with systematic frequency error ranging from −4 to 4 cm−1. To see this figure in color, go online.

Water model dependence

SPC/E, TIP3P, and TIP3Pfb are different in structure, electrostatic charges, and van der Waals parameters, which result in different intermolecular interactions and diffusion coefficients (80, 95). These differences noticeably affect the amide I frequency and spectral line shape, as illustrated in our recent study of Ala‒Ala (15). SPC/E water was shown to better reproduce dynamical behavior and spectral line shape in 2D IR spectroscopy (15, 96), whereas TIP3P water has the benefit of speeding up conformational sampling of proteins (97), and it is commonly used with many FFs.

To illustrate the effect of different water models on the amide I frequency, Fig. 8 a and Fig. S6 presents the average vibrational frequencies of the two amide vibrations as a function of peptide-backbone dihedral angles using the TIP3P and SPC/E water models with the C36m FF. One clear observation is that the frequency depends on AAA conformations, and the αR basin has the highest frequency, consistent with the comparisons of conformer spectra in Fig. 4. The other observation is that SPC/E water results in a uniform shift of −2 to −6 cm−1 relative to TIP3P. This shift is on the order of the uncertainty of our spectroscopic model but can significantly influence the ensemble refinements.

Figure 8.

(a) Mean lower peak (exciton) frequency distribution of UL AAA from C36m TIP3P ensemble (left) and C36m SPC/E ensemble (right). Note that the TIP3P atomic charges are applied to the C36m SPC/E trajectory. (b) The population percentage of conformers of the C27 SPC/E ensemble before refinement (black line) and after refinement against the entire set of the spectra (colored bars) is shown. Frequency correction is applied on the right panel. The black error bars represent the uncertainty of the original distribution estimated from block averaging. The colored error bars reflect the ±2σ uncertainty due to the spectroscopic map, determined by the maximal and the minimal populations with systematic frequency error ranging from −4 to 4 cm−1. To see this figure in color, go online.

The effect of the red shift of SPC/E water on the refined population changes of the C27 SPC/E ensemble can be seen in Fig. 8 b. Without frequency correction to have the same average site frequencies as the CHARMM TIP3P trajectories (see the Supporting Materials and Methods), the population of ppII is 74, 11% lower than the average value with the frequency correction (Table 1), and the corresponding uncertainty is as high as 17%. In contrast, the refinements with the frequency correction have better consistency against the whole set of IR spectra. Although the correction applied here is only an approximation for correcting the frequency shift due to structural difference between water models, it helps avoid false positive interpretations by using FTIR spectra as the only constraint without frequency correction (Fig. S7) and achieves better consistency among the various FFs shown in Fig. 6.

Errors in spectroscopic maps

Spectroscopic maps certainly influence the quality of ensemble refinement with sources of error such as choice of electrostatic variables used in the frequency map and errors in the frequency or coupling maps. Among these factors, we found that the most significant factor is the error due to the frequency map, as partly seen in the systematic bias present in different water models above. Taking 2σ (±4 cm−1) of the spectroscopic map error as the estimated confidence interval (5, 53), the highest uncertainty of determining the ensemble populations against the full set of spectra is found to be 18% in AMBERfb15 ensembles (Table S4). These high uncertainties indicate that the frequency error is the most influential source of degrading quality of the ensemble refinement. Increased uncertainties originate from introducing different water models and potentially the CONH2 group, but the range of uncertainty is still narrower than the ±15% reported in the ELP ensemble refinement study against FTIR spectroscopy (5), supporting the conclusion that 2D IR spectroscopy serves as an additional and stringent constraint on refining the conformational ensemble.

Errors due to the nearest-neighbor coupling map are difficult to address, because there are no experimental standards for evaluating the quality of coupling maps. However, at the DFT level calculations, the unsigned coupling map uncertainty is 1.7 cm−1 (98). Based on this value, we estimated the error bars in frequency prediction due to coupling uncertainty to be 1.3 cm−1 (see the Supporting Materials and Methods), smaller than the confidence interval of site frequency uncertainty (2 cm−1), suggesting that the coupling uncertainty may be less of a factor than the errors in the frequency map. However, we cannot conclude that the uncertainty in the coupling map is insignificant for the ensemble refinements. Also, different choices of electrostatic variables are found to give consistent ensemble refinement trends (see the Supporting Materials and Methods).

Comparison to other studies of AAA

Our refinements of 17 combinations of FFs and water models indicate that the conformational ensemble of AAA consists of 85% ppII, 14% β, and a negligible population of αR, mostly consistent with other studies shown in Table 1 except for the result from Bayesian Energy Landscape Tilting and some studies having a larger αR population than the β population. There are a few differences among these studies, such as different definitions of the conformational states, various approaches of determining structural ensembles, and different experimental techniques employed. First, how to cluster structures into conformational states varies from study to study, which would lead to different values of conformational populations. Note that our boundary of distinguishing ppII and β conformers has been shifted to a smaller value of ϕ to reside in the middle of the two basins, resulting in a larger box of ppII and a larger population compared to the Bayesian Energy Landscape Tilting study. Second, the previous studies of refining or restraining ensemble are against NMR data such as chemical shift and J-coupling, whereas in our study, we use FTIR and 2D IR spectra, which provide different information and have a different uncertainty. From the simulated conformer spectra in Fig. 4, the IR spectroscopy of AAA strongly disfavors αR, but small amounts may still be possible within the sensitivity of the experiment (29). The early 2D IR study of AAA suggested 20% αR. They excluded β conformer based on the angle derived from 3J-coupling between Cα and N protons and performed fitting based on the two-state model of ppII and αR (62). However, all of the studies suggest the dominance of the ppII conformation, and the Bayesian ensemble refinement against IR spectroscopy is consistent with most of the studies.

Conclusions

We studied a Bayesian ensemble-refinement scheme using structure-based amide I spectral modeling of site-specifically labeled peptide isotopologues against FTIR and 2D IR spectroscopy. This proof-of-principle study on AAA, drawing on multiple FFs and water models, demonstrates the practical capability of 2D IR experiments to constrain quantitative ensemble-refinement protocols and, in this case, consistently resulted in ensembles consisting of 85% population in the ppII basin, 14% in the β basin, and a negligible αR population, consistent with most previous studies on AAA. The nature of Bayesian statistics allows us to improve refinement by integrating other complementary experimental constraints. Investigating potential sources of uncertainty, we find the dominant factor influencing results is systematic frequency uncertainty from the amide I frequency spectroscopic map. However, with the structural information given by 2D IR spectroscopy, the upper bound of the uncertainty range can be narrowed down to ∼15% in the worst case. We believe this study helps lay the groundwork for general methods of refining protein conformational ensembles against isotope-edited 2D IR spectroscopy. With additional steps to advance this refinement approach, including further improvements to amide I spectroscopic models and incorporating conformational binning strategies better suited to proteins such as Markov state models (13, 21, 22), we hope to effectively describe conformational ensembles in complex, disordered systems at equilibrium and in nonequilibrium dynamic processes.

Author Contributions

C.-J. F. and A. T. designed the research. B.D. synthesized and purified the sample. C.-J. F. carried out the experiments and simulations and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to writing the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ann Fitzpatrick for her technical assistance on 2D IR spectroscopy and Paul Stevenson for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM118774). This work was completed in part with resources provided by the University of Chicago Research Computing Center.

Editor: Michele Vendruscolo.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods, thirteen figures, and five tables are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(18)30571-X.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Papoian G.A. Proteins with weakly funneled energy landscapes challenge the classical structure-function paradigm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:14237–14238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807977105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burger V.M., Gurry T., Stultz C.M. Intrinsically disordered proteins: where computation meets experiment. Polymers (Basel) 2014;6:2684–2719. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flock T., Weatheritt R.J., Babu M.M. Controlling entropy to tune the functions of intrinsically disordered regions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2014;26:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonomi M., Heller G.T., Vendruscolo M. Principles of protein structural ensemble determination. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2017;42:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reppert M., Roy A.R., Tokmakoff A. Refining disordered peptide ensembles with computational amide I spectroscopy: application to elastin-like peptides. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2016;120:11395–11404. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b08678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rieping W., Habeck M., Nilges M. Inferential structure determination. Science. 2005;309:303–306. doi: 10.1126/science.1110428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleming G.R., Wolynes P.G. Chemical dynamics in solution. Phys. Today. 1990;43:36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henzler-Wildman K., Kern D. Dynamic personalities of proteins. Nature. 2007;450:964–972. doi: 10.1038/nature06522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryant R.G. The NMR time scale. J. Chem. Educ. 1983;60:933. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zanni M.T., Hochstrasser R.M. Two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy: a promising new method for the time resolution of structures. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001;11:516–522. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamm P., Zanni M. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2011. Concepts and Methods of 2D Infrared Spectroscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baiz C.R., Reppert M., Tokmakoff A. Ultrafast Infrared Vibrational Spectroscopy. CRC Press; 2013. An introduction to protein 2D IR spectroscopy; pp. 361–404. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baiz C.R., Lin Y.S., Tokmakoff A. A molecular interpretation of 2D IR protein folding experiments with Markov state models. Biophys. J. 2014;106:1359–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamm P., Lim M., Hochstrasser R.M. The two-dimensional IR nonlinear spectroscopy of a cyclic penta-peptide in relation to its three-dimensional structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:2036–2041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng C.J., Tokmakoff A. The dynamics of peptide-water interactions in dialanine: an ultrafast amide I 2D IR and computational spectroscopy study. J. Chem. Phys. 2017;147:085101. doi: 10.1063/1.4991871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bredenbeck J., Hamm P. Peptide structure determination by two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy in the presence of homogeneous and inhomogeneous broadening. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;119:1569–1578. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng Y., Huang J., Ge N.H. Structure of penta-alanine investigated by two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy and molecular dynamics simulation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2016;120:5325–5339. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b02608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torres J., Kukol A., Arkin I.T. Site-specific examination of secondary structure and orientation determination in membrane proteins: the peptidic (13)C=(18)O group as a novel infrared probe. Biopolymers. 2001;59:396–401. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(200111)59:6<396::AID-BIP1044>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Decatur S.M. Elucidation of residue-level structure and dynamics of polypeptides via isotope-edited infrared spectroscopy. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;39:169–175. doi: 10.1021/ar050135f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baiz C.R., Peng C.S., Tokmakoff A. Coherent two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy: quantitative analysis of protein secondary structure in solution. Analyst (Lond.) 2012;137:1793–1799. doi: 10.1039/c2an16031e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith A.W., Lessing J., Knoester J. Melting of a beta-hairpin peptide using isotope-edited 2D IR spectroscopy and simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:10913–10924. doi: 10.1021/jp104017h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baiz C.R., Tokmakoff A. Structural disorder of folded proteins: isotope-edited 2D IR spectroscopy and Markov state modeling. Biophys. J. 2015;108:1747–1757. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang C.Y., Getahun Z., Gai F. Helix formation via conformation diffusion search. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:2788–2793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052700099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tucker M.J., Abdo M., Hochstrasser R.M. Nonequilibrium dynamics of helix reorganization observed by transient 2D IR spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:17314–17319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311876110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meuzelaar H., Marino K.A., Woutersen S. Folding dynamics of the Trp-cage miniprotein: evidence for a native-like intermediate from combined time-resolved vibrational spectroscopy and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2013;117:11490–11501. doi: 10.1021/jp404714c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevenson P., Götz C., Vaziri A. Visualizing KcsA conformational changes upon ion binding by infrared spectroscopy and atomistic modeling. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:5824–5831. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b02223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kratochvil H.T., Carr J.K., Zanni M.T. Instantaneous ion configurations in the K+ ion channel selectivity filter revealed by 2D IR spectroscopy. Science. 2016;353:1040–1044. doi: 10.1126/science.aag1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang J., MacKerell A.D., Jr. Force field development and simulations of intrinsically disordered proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2018;48:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Best R.B., Buchete N.V., Hummer G. Are current molecular dynamics force fields too helical? Biophys. J. 2008;95:L07–L09. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.132696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palazzesi F., Prakash M.K., Barducci A. Accuracy of current all-atom force-fields in modeling protein disordered states. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:2–7. doi: 10.1021/ct500718s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rauscher S., Gapsys V., Grubmüller H. Structural ensembles of intrinsically disordered proteins depend strongly on force field: a comparison to experiment. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:5513–5524. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henriques J., Cragnell C., Skepö M. Molecular dynamics simulations of intrinsically disordered proteins: force field evaluation and comparison with experiment. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:3420–3431. doi: 10.1021/ct501178z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levine Z.A., Shea J.E. Simulations of disordered proteins and systems with conformational heterogeneity. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2017;43:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pitera J.W., Chodera J.D. On the use of experimental observations to bias simulated ensembles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;8:3445–3451. doi: 10.1021/ct300112v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roux B., Weare J. On the statistical equivalence of restrained-ensemble simulations with the maximum entropy method. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;138:084107. doi: 10.1063/1.4792208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cavalli A., Camilloni C., Vendruscolo M. Molecular dynamics simulations with replica-averaged structural restraints generate structural ensembles according to the maximum entropy principle. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;138:094112. doi: 10.1063/1.4793625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boomsma W., Ferkinghoff-Borg J., Lindorff-Larsen K. Combining experiments and simulations using the maximum entropy principle. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olsson S., Wu H., Noé F. Combining experimental and simulation data of molecular processes via augmented Markov models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:8265–8270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704803114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beauchamp K.A., Pande V.S., Das R. Bayesian energy landscape tilting: towards concordant models of molecular ensembles. Biophys. J. 2014;106:1381–1390. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiao X., Kallenbach N., Zhang Y. Peptide conformation analysis using an integrated Bayesian approach. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2014;10:4152–4159. doi: 10.1021/ct500433d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brookes D.H., Head-Gordon T. Experimental inferential structure determination of ensembles for intrinsically disordered proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:4530–4538. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fisher C.K., Huang A., Stultz C.M. Modeling intrinsically disordered proteins with bayesian statistics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:14919–14927. doi: 10.1021/ja105832g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Różycki B., Kim Y.C., Hummer G. SAXS ensemble refinement of ESCRT-III CHMP3 conformational transitions. Structure. 2011;19:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shevchuk R., Hub J.S. Bayesian refinement of protein structures and ensembles against SAXS data using molecular dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017;13:e1005800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sethi A., Anunciado D., Gnanakaran S. Deducing conformational variability of intrinsically disordered proteins from infrared spectroscopy with Bayesian statistics. Chem. Phys. 2013;422:143–155. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphys.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reppert M., Tokmakoff A. Computational amide I 2D IR spectroscopy as a probe of protein structure and dynamics. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2016;67:359–386. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-040215-112055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bouř P., Keiderling T.A. Empirical modeling of the peptide amide I band IR intensity in water solution. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;119:11253–11262. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ham S., Kim J.-H., Cho M. Correlation between electronic and molecular structure distortions and vibrational properties. II. Amide I modes of NMA–nD2O complexes. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;118:3491. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayashi T., Zhuang W., Mukamel S. Electrostatic DFT map for the complete vibrational amide band of NMA. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2005;109:9747–9759. doi: 10.1021/jp052324l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.la Cour Jansen T., Knoester J. A transferable electrostatic map for solvation effects on amide I vibrations and its application to linear and two-dimensional spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;124:044502. doi: 10.1063/1.2148409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang L., Middleton C.T., Skinner J.L. Development and validation of transferable amide I vibrational frequency maps for peptides. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:3713–3724. doi: 10.1021/jp200745r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reppert M., Tokmakoff A. Electrostatic frequency shifts in amide I vibrational spectra: direct parameterization against experiment. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;138:134116. doi: 10.1063/1.4798938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reppert M., Tokmakoff A. Communication: Quantitative multi-site frequency maps for amide I vibrational spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 2015;143:061102. doi: 10.1063/1.4928637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Torii H. Amide I vibrational properties affected by hydrogen bonding out-of-plane of the peptide group. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:727–733. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Torii H., Tasumi M. Ab initio molecular orbital study of the amide I vibrational interactions between the peptide groups in di- and tripeptides and considerations on the conformation of the extended helix. J. Raman Spectrosc. 1998;29:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ham S., Cha S., Cho M. Amide I modes of tripeptides: Hessian matrix reconstruction and isotope effects. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;119:1451. [Google Scholar]

- 57.la Cour Jansen T., Dijkstra A.G., Knoester J. Modeling the amide I bands of small peptides. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;125:44312. doi: 10.1063/1.2218516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hayashi T., Mukamel S. Vibrational-exciton couplings for the amide I, II, III, and A modes of peptides. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:11032–11046. doi: 10.1021/jp070369b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maekawa H., De Poli M., Ge N.H. Toward detecting the formation of a single helical turn by 2D IR cross peaks between the amide-I and -II modes. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:11775–11786. doi: 10.1021/jp9045879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Woutersen S., Hamm P. Structure determination of trialanine in water using polarization sensitive two-dimensional vibrational spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2000;104:11316–11320. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Woutersen S., Hamm P. Isotope-edited two-dimensional vibrational spectroscopy of trialanine in aqueous solution. J. Chem. Phys. 2001;114:2727–2737. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Woutersen S., Pfister R., Stock G. Peptide conformational heterogeneity revealed from nonlinear vibrational spectroscopy and molecular-dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2002;117:6833–6840. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schweitzer-Stenner R. Distribution of conformations sampled by the central amino acid residue in tripeptides inferred from amide I band profiles and NMR scalar coupling constants. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:2922–2932. doi: 10.1021/jp8087644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Graf J., Nguyen P.H., Schwalbe H. Structure and dynamics of the homologous series of alanine peptides: a joint molecular dynamics/NMR study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:1179–1189. doi: 10.1021/ja0660406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oh K.I., Lee K.K., Cho M. Circular dichroism eigenspectra of polyproline II and β-strand conformers of trialanine in water: singular value decomposition analysis. Chirality. 2010;22(Suppl 1):E186–E201. doi: 10.1002/chir.20870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Deflores L.P., Nicodemus R.A., Tokmakoff A. Two-dimensional Fourier transform spectroscopy in the pump-probe geometry. Opt. Lett. 2007;32:2966–2968. doi: 10.1364/ol.32.002966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pronk S., Páll S., Lindahl E. GROMACS 4.5: a high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:845–854. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mackerell A.D., Jr., Feig M., Brooks C.L., III Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields: limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1400–1415. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bjelkmar P., Larsson P., Lindahl E. Implementation of the charmm force field in GROMACS: Analysis of protein stability effects from correction maps, virtual interaction sites, and water models. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010;6:459–466. doi: 10.1021/ct900549r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang J., MacKerell A.D., Jr. CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: validation based on comparison to NMR data. J. Comput. Chem. 2013;34:2135–2145. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huang J., Rauscher S., MacKerell A.D., Jr. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:71–73. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jorgensen W.L., Maxwell D.S., Tirado-Rives J. Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:11225–11236. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kaminski G.A., Friesner R.A., Jorgensen W.L. Evaluation and reparametrization of the OPLS-AA force field for proteins via comparison with accurate quantum chemical calculations on peptides †. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105:6474–6487. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Robertson M.J., Tirado-Rives J., Jorgensen W.L. Improved peptide and protein torsional energetics with the OPLSAA force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:3499–3509. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lindorff-Larsen K., Piana S., Shaw D.E. Improved side-chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins. 2010;78:1950–1958. doi: 10.1002/prot.22711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maier J.A., Martinez C., Simmerling C. ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:3696–3713. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang L.P., McKiernan K.A., Pande V.S. Building a more predictive protein force field: a systematic and reproducible route to AMBER-FB15. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121:4023–4039. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b02320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Berendsen H.J.C., Grigera J.R., Straatsma T.P. The missing term in effective pair potentials. J. Phys. Chem. 1987;91:6269–6271. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jorgensen W.L., Chandrasekhar J., Klein M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang L.P., Martinez T.J., Pande V.S. Building force fields: an automatic, systematic, and reproducible approach. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014;5:1885–1891. doi: 10.1021/jz500737m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Toal S., Meral D., Schweitzer-Stenner R. pH-Independence of trialanine and the effects of termini blocking in short peptides: a combined vibrational, NMR, UVCD, and molecular dynamics study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2013;117:3689–3706. doi: 10.1021/jp310466b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nosé S. A unified formulation of the constant temperature molecular dynamics methods. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:511–519. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hoover W.G. Canonical dynamics: Equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys. Rev. A Gen. Phys. 1985;31:1695–1697. doi: 10.1103/physreva.31.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tribello G.A., Bonomi M., Bussi G. PLUMED 2: new feathers for an old bird. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2014;185:604–613. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Reppert, M. 2017. g_amide. https://github.com/mreppert/g_amide/tree/v1.0.0, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.582688.

- 86.Reppert, M., and C.-J. Feng. 2017. g_spec. https://github.com/mreppert/g_spec/tree/v1.0.0, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.582690.

- 87.Torii H. Effects of intermolecular vibrational coupling and liquid dynamics on the polarized Raman and two-dimensional infrared spectral profiles of liquid N,N-dimethylformamide analyzed with a time-domain computational method. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2006;110:4822–4832. doi: 10.1021/jp060014c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liang C., Jansen T.L. An efficient N(3)-scaling propagation scheme for simulating two-dimensional infrared and visible spectra. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;8:1706–1713. doi: 10.1021/ct300045c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hamm P., Lim M., Hochstrasser R.M. Structure of the amide I band of peptides measured by femtosecond nonlinear-infrared spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:6123–6138. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hummer G., Köfinger J. Bayesian ensemble refinement by replica simulations and reweighting. J. Chem. Phys. 2015;143:243150. doi: 10.1063/1.4937786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kruiger J.F., van der Vegte C.P., Jansen T.L. Suppressing sampling noise in linear and two-dimensional spectral simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2015;142:054201. doi: 10.1063/1.4907277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hansen P.C., O’Leary D.P. The Use of the L–curve in the regularization of discrete Ill-posed problems. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 1993;14:1487–1503. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sieler G., Schweitzer-Stenner R., Asher S.A. Different conformers and protonation states of dipeptides probed by polarized raman, UV−resonance Raman, and FTIR spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;103:372–384. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Best R.B., Zhu X., Mackerell A.D., Jr. Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone φ, ψ and side-chain χ(1) and χ(2) dihedral angles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;8:3257–3273. doi: 10.1021/ct300400x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mahoney M.W., Jorgensen W.L. Diffusion constant of the TIP5P model of liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 2001;114:363. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schmidt J.R., Roberts S.T., Skinner J.L. Are water simulation models consistent with steady-state and ultrafast vibrational spectroscopy experiments? Chem. Phys. 2007;341:143–157. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Florová P., Sklenovský P., Otyepka M. Explicit water models affect the specific solvation and dynamics of unfolded peptides while the conformational behavior and flexibility of folded peptides remain intact. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010;6:3569–3579. doi: 10.1021/ct1003687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Carr J.K., Zabuga A.V., Skinner J.L. Assessment of amide I spectroscopic maps for a gas-phase peptide using IR-UV double-resonance spectroscopy and density functional theory calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2014;140:224111. doi: 10.1063/1.4882059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.