Abstract

Religious leaders, particularly African-American pastors, are believed to play a key role in addressing health disparities. Despite the role African-American pastors may play in improving health, there is limited research on pastoral influence. The purpose of this study was to examine African-American pastors’ perceptions of their influence in their churches and communities. In-depth interviews were conducted with 30 African-American pastors and analyzed using a grounded theory approach. Three themes emerged: the historical role of the church; influence as contextual, with pastors using comparisons with other pastors to describe their ability to be influential; and a reciprocal relationship existing such that pastors are influenced by factors such as God and their community while these factors also aid them in influencing others. A conceptual model of pastoral influence was created using data from this study and others to highlight factors that influence pastors, potential outcomes and moderators as well as the reciprocal nature of pastoral influence.

Keywords: Health disparities, African Americans, church, clergy, conceptual model

Introduction

African-American (AA) communities are disproportionately affected by chronic disease and poor health outcomes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). AAs have increased mortality rates for various health conditions including heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and kidney disease (National Center for Health Statistics, 2011). In 2013, the National Institutes of Health highlighted HIV/AIDS, heart disease, cancer, and health education as necessary foci of efforts to reduce health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations (National Institute of Health, 2013). Unfortunately, addressing these health disparities in AA communities has proven difficult due to limited access to health services and resources (Klein, Nguyen, Saffore, Modlin, & Modlin, 2010; Link & McKinlay, 2009) as well as community mistrust in research and traditional medical systems (Armstrong et al., 2008; Matthews, Sellergen, Manfriedi, & Williams, 2002). These barriers have led to traditional health promotion programs having limited success in reducing the health disparities affecting AAs in the United States.

Previous studies have suggested that using community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches to design and implement health promotion programs may prove beneficial in reducing the health disparities affecting AAs (Plescia, Herrick, & Chavis, 2008; Spencer et al., 2011; Two Feathers et al., 2005). CBPR encourages researchers and members of the community to share knowledge and power equitably so that resulting health programs are more effective (Minkler, 2003). Given the importance of churches within AA communities and the leadership they provide both spiritually (Taylor & Chatters, 1986) as well as secularly (Brown & Brown, 2003), many CBPR efforts have partnered with churches to develop and implement health promotion programs (Ammerman et al., 2002; Campbell et al., 1999; Demark-Wahnefried et al., 2000; Markens, Fox, Taub, & Gilbert, 2002; Taylor, Ellison, Chatters, Levin, & Lincoln, 2000).

Previous research suggests pastor involvement and support are important factors in the successful implementation of health promotion programs, both faith-based programs as well as more general community-based programs placed within churches (Bopp, Baruth, Peterson, & Webb, 2013; Campbell et al., 2007; Catanzaro, Meador, Koenig, Kuchibhatla, & Clipp, 2007; Taylor et al., 2000). The importance of pastors may be due in part to the influence they exert on both their congregation and community (Collins, 2015). Pastoral influence has been shown to play a role in the health of their congregation members (Baruth, Bopp, Webb, & Peterson, 2014; Carroll, 2006) as well as members of the larger community they serve (Bopp et al., 2013). The willingness of AA pastors, in particular, to become personally engaged in the health-related concerns of their communities, may explain why they are often viewed as leaders both inside and outside the walls of the church (Carroll, 2006).

Diffusion of innovations theory provides a framework for how innovations are spread within a group (Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath, 2015). Research suggests group role models or opinion leaders may be best suited for beginning the diffusion of a health behavior or change in behavior through a network of connected individuals (Valente & Davis, 1999). Pastors are potentially important promoters of health due to their formal leadership position and their potential to influence their congregation members and the larger public (Baruth et al., 2014; Bopp et al., 2013). However, previous studies indicate pastors rarely participate in health promotion programs (Baruth, Wilcox, Laken, Bopp, & Saunders, 2008; Wilcox et al., 2007). This lack of participation may be due, in part, to some pastors not meeting physical activity or diet recommendations (Webb, Bopp, & Fallon, 2013b); therefore, not feeling able to serve as role models for health (Harmon, Blake, Armstead, & Hebert, 2013).

While clergy health has become of increasing interest in the literature (Baruth et al., 2014; Bopp et al., 2013; Bopp & Fallon, 2011; Bopp, Webb, Baruth, & Peterson, 2014; Webb et al., 2013; Webb et al., 2013), few studies have asked pastors about their perspective on their ability to influence both congregation members as well as the larger community they serve. This study aimed to fill this gap by examining the perceptions of AA pastors on their potential influence in their church and community. The goal of this study was to provide guidance to researchers and health practitioners engaging pastors in the diffusion of health practices within communities, especially AA communities.

Methods

A qualitative approach was used to examine characteristics of pastoral influence from the perspective of AA pastors. Details on the data collection methods and participants in this study have previously been published (Harmon et. al., 2013). In brief, 30 AA pastors of churches in South Carolina, USA were recruited between October 2010 and December 2011. Participants completed a demographic survey and participated in a one-hour interview. Of the 30 pastors recruited, 83% were male, 67% identified as Baptist, and 60% had served at their church for 10 years or less (Harmon et. al., 2013). Approval by the University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board was given before any study activities began.

All interviews were audio recorded and the transcriptions for each interview were analyzed using NVivo® 10 (NVivo). A grounded-theory approach was used in the analysis of data for this study (Charmaz, 2006). Through this approach, themes related to pastors’ ideologies of influence were allowed to emerge. Credibility and trustworthiness of the codes was achieved by two coders (SS and BEH) through: (1) reviewing transcripts and focusing on new perspectives and problematic interviews; (2) open coding for emergent themes; (3) iterative thematic coding of interviews guided by the aims of the research and review of the literature; (4) bi-weekly peer debriefing on emergent themes, refinement of the codebook, selective coding, and categorization; and (5) interpretation of findings in the context of existing conceptualizations and empirical research. The questions used in this analysis are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Questions from the Semi-structured Interview Guide Related to Pastoral Influence

|

Results

When acknowledging their influence and discussing its context, pastors used terms such as “authority,” “impact,” “leader,” and “listener.” They also spoke of being “respected” and having a “responsibility” to both their congregations and communities. Three themes related to pastoral influence emerged from the data: Role of History, Context of Influence, Influence as a Reciprocal Relationship. These themes and their subthemes are outlined below with additional quotes presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Selected Quotes Illustrating Themes

| Role of History | “The church in general, but the black church in particular, will always be a strong subject of evidence and proof for healthcare issues” |

| “It’s an altogether different experience. An African-American church is the cornerstone of the African-American culture” | |

| “…most of those traditional churches dare not call their Pastor by their first name. And I think that is indicative to where we’ve come from, to make sure that we get respect…Because it has been taken…from our forefathers in such a way that—and it’s been drilled in us that you don’t say a first name, it’s Pastor this or First Lady that…” | |

|

| |

| Context of Influence | |

| Differences by Race | “When I talk to my white brothers and pastors, yeah things have tightened up, but they’re not hurting. But when I talk to my African American brothers or sisters that may be pastoring, when they say it’s tough, it’s tough just keeping the doors open because the congregation members or congregates have lost jobs and their money has gotten tight.” |

| Differences with Other Pastors | “I would say some (pastors) that I have encountered since I’ve been here, ministry’s been about them, not about people.” |

| Differences by Denomination | “I see now that being a Baptist has its benefits in the sense that we are an autonomous body meaning that we’ve still guided by a board of people or deacons but yet we’re still able to operate under the influence of the Holy Spirit meaning that we don’t necessarily have to report to a bishop or to a priest but we only report to God.” |

| Differences by Congregation’s Age | “I feel like a lot of times – and especially with a lot of the older members that were brought up in a time that you don’t argue with the preacher. You don’t question the preacher. Whatever the preacher says, you just go along with it, whereas some of the younger people, they’re gonna question. They’re gonna ask.” |

| Differences by Church Location (rural vs urban) | “So I wasn’t received well because I was considered an outsider even by some of the members in the church that I was pastoring because I was an outsider and what I said didn’t matter.” |

| Differences by Church Size | “And one of the kicks of mega-churches is that they move out of the communities. They move into the suburbs and area so they don’t have to deal with all those community problems.” |

| Differences by Gender | “I think female pastors work harder. I think it requires more simply because the older generation kind of feels like you shouldn’t be doing that anyway or that’s not your place.” |

|

| |

| Influence as a Reciprocal Relationship | |

| Community and Congregation | “…being committed to the homeless here in the Columbia area, we’re very much into HIV ministry, and to minister to the least among us.” |

| “When they see how you moved from that church and then to a grocery store and then to that church and then the community resource center and then another church in northeast. And then a whole school, then they don’t question the program anymore. They say, “Pastor, what do you need of us?” | |

| “I’ve been here so long now that I really don’t have to put on any airs for anybody. They know who I am.” | |

| God | “…through prayer, do you know it turned totally around. I used that to teach my flock, is that you’ve gotta be patient and you’ve gotta wait on the right time for change. Change isn’t something that you rush. You cannot change many. Only God can and through prayer the change will come.” |

| “Eventually, God help me to understand I need to move more towards this is who I really – what I’m called to do as far as a pastor.” | |

| Stress | “I’m just reading an interesting book now by a pastor from New York who talks about this very – burnout, how sometimes pastors burn out and why. And one thing he talks about is lack of transparency and sometimes we just take on too much” |

| “[Family] give me support. My siblings: support. My children: support. Then I have grandchildren, and they’re supportive as well.” | |

Role of History

Pastors who noted the AA church’s historical role in their influence (n=13) spoke of the church’s influence on the community and on the pastor’s role. They also spoke of the historical context of disparities that face AA communities today and that have helped to shape the influence of AA pastors over time.

Pastors noted the history of the AA church continues to influence practices within the church. As one pastor said, “An African-American church is the cornerstone of the African-American culture.” Another pastor spoke of the multiple roles the church has played and continues to play in the lives of AAs, “when we look at the [African-American] church’s history…They were schools Monday through Friday, and then the same building was used for the church on Sunday…”

Pastors felt this history has a role in the influence of AA pastors today. It was noted that historical displays of respect include congregation and community members not addressing AA pastors by their first name, but rather by their title and last name. In addition, pastors spoke of having a broader role and level of influence due to traditions and cultural norms that have their roots in African tribal practices as well as slavery and the Civil Rights era. “The congregation looked to [pastors] for more. A pastor in an African-American church was far more than…someone who teaches and preaches. If you go back to African culture, you’re almost a tribal leader, and so that tradition sort of continues.”

Pastors also mentioned their influence in part comes from the great need faced by the communities they serve, which is rooted in historical injustices. These pastors spoke of the high rates of sickness and disease, economic disparities, and social inequalities faced by AAs and reflected in their congregations and communities served. One pastor explained, “So we’re bringing in the [health] programs, so we bring the information to where you are and you will find us [African Americans] in church.” Another pastor spoke of the economic situation facing the community and “access and availability [to social and wellness networks] as another key component that the church has to take on.”

Context of Influence

Pastors often spoke of their influence through the use of personal, social, and environmental comparisons suggesting the influence of AA pastors is contextual. They spoke most often of differences in influence based on one’s race (n=15) followed by comparisons with other pastors (n=13), differences by denomination (n=12), including tenure of the pastor (n=7), and age of congregation members (n=10). Pastors also noted their ability to be influential varied based on the church’s geographical location (rural vs. urban) (n=8), size (n=8), and a pastor’s gender (n=5).

Pastors spoke of how the influence of AA pastors differs compared to pastors of other racial or ethnic backgrounds. Pastors spoke of needing to speak the “community language” in order to be influential within the church and larger AA community. However, they also spoke of financial hardships within the AA church and community compared to churches and communities of other races/ethnicities. In this, pastors acknowledged the church may not serve the same role in other racial/ethnic groups as it does in AA communities. They also noted AA pastors often must be bi-vocational (i.e., have a job/career outside of pastoring) while White pastors can more often be financially supported by their church. However, several pastors (n=4) noted “people are people” and the “Lord has always been the same no matter what culture you’re in.” Indicating that while the social and physical environment within which AA pastors practice may differ along racial lines, the fundamental teachings and service of a pastor do not.

Pastors spoke of their influence through comparisons with other pastors. These comparisons most often included noting other pastors being more focused on material gain and prestige rather than providing the people of the church and community with their time, love, and care. As one pastor noted, “people give us a platform…what we sometimes do with our egos is stretch the platform…under the guise of we’re doing ministry.”

Differences between the Methodist tradition of itineracy and the Baptist tradition of churches selecting their pastor was discussed and believed also to impact pastoral influence. Pastors of Baptist churches reported their church’s autonomy allows them to remain at one church for a longer period of time providing them with opportunities to “build long lasting relationships.” These relationships were believed to further establish their pastoral influence within their church. As one Baptist pastor noted, “The pastor who was here before I got here was here forty years and that’s a unique opportunity to have that kind of influence on one particular congregation.”

A pastor’s ability to relate to the members of their congregation and community based on age also was a factor noted as contributing to pastoral influence. When engaging with younger individuals, pastors spoke of using words that “capture the younger people.” Pastors also reported that younger aged individuals are often a more demanding group because they are more likely to question the pastor’s teachings and influence compared to older congregation members. Alternatively, pastors spoke of needing to use proper grammar and hold more “traditional worship” services in order to engage and keep older congregation members.

Additional comparisons such as a church’s geographic location or size as well as a pastor’s gender were also believed to impact pastoral influence, but were mentioned less often. In the case of a church’s geographic location, pastors of more rural churches spoke of having to change their pastoral “approach” in order to influence the members of their church and community. Female pastors spoke of having to “work harder” and “be a little sterner” due to historical, congregational, or community biases against female compared to male pastors.

Influence as a Reciprocal Relationship

Pastors were asked both about how they influence others as well as how they are influenced in return. The responses received showed a reciprocal relationship in which pastors learn about the needs present in their congregations and communities then use their influence to find solutions and resources. In addition, pastors not only spoke of being influenced by God, but also of receiving their influence in part from God. Lastly, pastors spoke of the stress that comes with their position and how that stress influences their management of the position as well as their relationships with family.

Twenty-five pastors spoke of their congregations and communities influencing them. They reported the members of their church motivated them to “work harder” and attempt to “meet their [congregation’s] needs.” Pastors also spoke of congregation members influencing their understanding of the needs of the community, recognizing pastors do not “know it all” and must rely on members of their congregations to “introduce them to the lifestyle of the community.” Pastors often used terms such as “hurting” and “poor” when describing the communities they pastor. These characteristics inspired pastors to use their influence to serve the members of their communities. In one example, a pastor noted, “…I try to give them resources for food. So often I find myself dropping food off to them.”

Ten pastors specifically spoke of being a connector to community resources as an essential factor in their being influential. This role included being a hospital board member, having political or government connections, or having the education necessary to bring specific programs to the church. As a connector, pastors bridged the gap between their church and the resources available within their community, often taking on additional responsibilities outside of their church-related tasks. As one pastor stated, “the pastor, the senior leader is not only a spiritual leader, but they’re also viewed as political leaders, community leaders by default.”

In addition to influencing and being influenced by their churches and communities, pastors spoke of being influenced by God (n=7) as well as their influence being derived from God (n=11). Pastors spoke of decisions being based on the Word of God and guided by their prayers and conversations with God. This divine influence was credited with leading both congregation and community members to follow them. As one pastor said, “my emphasis is to please God and if I please God, then God will make the people’s hearts satisfied.” While pastors spoke of God influencing their messages and actions, which in turn helped them to influence others, they also spoke of their influence being directly derived from God. As one pastor said, “But there is an authority in your word’s decree – I would say, within a position or seat of authority that God has given you.”

Despite pastors attributing their position and its divine connection to their being influential, they also spoke of the need to build relationships with their congregations and communities (n=18). As noted above, this is in part done through speaking the language of the community, but also aided by the pastor being both genuine and authentic (n=9). As one pastor noted, “You can’t be a dictator. God may have given you the vision, but you’ve gotta have sense enough to know that you need the help of others to carry it out.” Within this context, pastors spoke of the importance of getting to know the individuals they are ministering. Pastors connected taking time to learn about their congregation and community members with building acceptance and trust, which they described as necessary to being influential. Being “sincere,” “straightforward,” and “real” were noted as traits pastors need in order to gain the trust and acceptance of their congregation and community. Pastors also spoke of being open and available to their church and community as one way of being authentic and genuine. One pastor described the process of making himself available to his congregation as “allowing people to touch and venture into my comfort zone.”

However, interviewees noted, “the hats that a pastor wears are many besides just pastoring.” In making themselves available, being a connector to resources, and God’s messenger, pastors greatly increase their stress levels. Fourteen pastors spoke of the stress of their job influencing the way in which they pastor. Pastors spoke of needing to hire staff, learning to delegate, or managing the stress in other ways, but they noted “burn out” as the reason many pastors leave the ministry. One reason for burn out among AA pastors is the need for many to be bi-vocational in order to earn an adequate income and have health benefits. Due to financial hardships in both AA communities as well as AA churches, pastors often have to, “take care of a needy congregation as well as go out and feed their family.” While some pastors (n=4) reported they were able to use the skills they acquired from their secular jobs to better serve the members of their church, most pastors spoke of bi-vocationalism as adding to the stress pastors function within.

One outcome of pastors wearing many hats is a reduction in time spent with family. One pastor noted, “Cause one [of] the tragedies with pastors is that they spend so much time in the church that they neglect their very own family.” Despite this separation from family, thirteen pastors spoke of their families positively influencing them. Most pastors spoke of their spouse as being a helpmate, source of encouragement, and influence on them in their ministry. As a pastor said of his wife, “She keeps me encouraged. She looks out for my welfare – she protects me [when tired]. She reminds me I’m not Jesus.” Pastors also spoke of their children or members of their family who had been in the ministry as helping them to balance the many aspects of their lives.

Nineteen pastors felt their influence has changed both their church and community. While pastors spoke of using their influence for good, they also spoke of their influence as a very “humbling” responsibility. For this reason, pastors believed they should “be very careful and cautious how [they] use influence” as their influence, if used unwisely, could harm instead of help those they serve. As one pastor said, “there is no one who has a greater and more significant captive audience on a weekly basis than the one who resides at the pulpit. And people are very likely to listen to the voice of the pastor, than they – in the African-American community, would listen to anyone else. That’s an influence that’s scary to me.”

Discussion

This study explored how AA pastors view their influence as it relates to both their church and community. Given the potential role for churches in reducing health disparities (Bopp & Fallon, 2011; Campbell et al., 2007), it is important for social scientists to understand pastoral influence and its potential to impact health outcomes. Pastors in this study spoke about influence in a highly contextual way. They spoke of the seeds of influence being present due to the history of the church, their denomination, and their position’s divine connection, but they also spoke of influence varying based on a pastor’s current environment and individual characteristics.

Pastors reported the history of the AA church contributes to the influence of AA pastors, which matches with the current literature on the role of the AA church in AA communities (Campbell et al., 2007; Mamiya, 2006; Torrence, Phillips, & Guidry, 2005). The AA church has been noted as a driving force in areas related to political activism (Torrence et al., 2005), education (Barrett, 2010; Isaac, 2005), and health (Campbell et al., 2007; Torrence et al., 2005). Our findings suggest the historical and current prominence of the AA church elevates pastors, making them important gatekeepers within AA communities. The majority of pastors interviewed felt a pastor’s influence differs based on the race/ethnicity of the pastor, with AA pastors having potentially broader influence than White pastors. Findings from a national survey of 255 pastors supports this comparison as AA pastors in the study reported they play more of a leadership role in the social and political arenas for their communities compared to White pastors (Cohall & Cooper, 2010).

Serving as a connector to a variety of resources in the community was reported by the AA pastors in this study as well. Connecting congregants and community members to resources they may not otherwise have access to places pastors in an important role as someone who can influence opinion through the programs they bring into their church as well as those they keep out. A previous qualitative study of 24, primarily White, faith leaders found they believed they have influence on issues related to health primarily by increasing awareness and being a role model (Baruth et al., 2014). However, a previous study with the same AA pastors in this study found only a small number of pastors with healthier behaviors identified themselves as role models for their church (Harmon et. al., 2013). In addition, pastors report little training in health during seminary (Bopp et al., 2014) and studies have found mixed results on whether denominational doctrine supports the promotion of health in the church (Bopp et al., 2014; Webb et al., 2013a). If we are to harness the influence of pastors, efforts are needed at multiple levels (e.g., denomination, church, personal) to increase knowledge and skills related to health promotion. Efforts such as the Annual Conference for Clergy and Congregational Leaders begun by Church Health and Methodist Le Bonheur Healthcare in Memphis, TN are a start (Church Health, 2016). However, training during seminary as well as clergy-focused interventions are needed if pastors are to capitalize on their influence to be the change agents envisioned by CBPR and diffusion of innovations theory (Bopp et al., 2014; Fallon, Bopp, & Webb, 2012; Harmon et al., 2013; Webb et al., 2013a).

The history of the church and a pastor’s ability to connect to resources provides an initial framework for pastoral influence. However, participants in this study also noted needing to speak the community’s language, connect with the needs of their congregation and community, and be genuine and authentic in these efforts in order to build trust and thereby influence. In their interviews, pastors detailed the time and work necessary to build trust and influence. While pastors can provide a gateway to communities for programs they endorse, researchers should not rely just on pastoral influence for program success. Instead, given the contextual nature of influence, researchers should engage with pastors in their community to understand the steps needed to acquire a congregation and community’s trust such that they, too, are trusted sources prior to implementing a faith-based health program (Ammerman et al., 2003; Campbell et al., 2007; Demark-Wahnefried et al., 2000).

Additionally, researchers should be cognizant of the stress most pastors work under. The multiple responsibilities associated with being a pastor can lead to negative physical and mental health outcomes (Chandler, 2009; Hall, 1997; Lee, 2007). Pastors in this study and other studies (Meek et al., 2003) note the importance of family support in reducing their stress and helping them with work-life balance. Clergy health programs have recently begun to be developed (Proeschold-Bell et al., 2013; Wallace et al., 2012). However, only one program to-date has reported outcome evaluation data indicating that although a clergy health program improved markers of physical health (e.g., metabolic syndrome), it was not effective at improving self-reported stress or depression scores among clergy (Proeschold-Bell et al., 2017). Much more work is needed to better understand stress (and depression) among clergy in order to develop more effective clergy health programs.

Conceptual Model

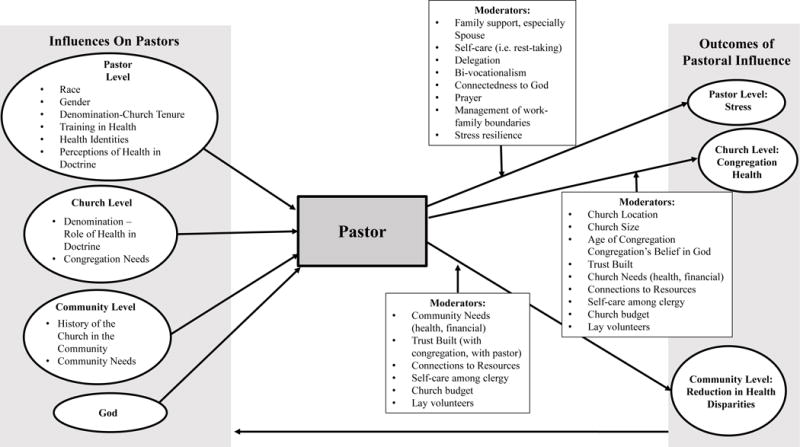

A conceptual model was constructed based on findings from this study, previous studies of pastors (Baruth et al., 2014; Bopp et al., 2013; Carroll, 2006; Webb et al., 2013a), and faith-based health programs (Bopp & Fallon, 2011; Campbell et al., 2007; Fallon et al., 2012; Lewis, Turton, & Francis, 2007; Proeschold-Bell et al., 2011; Resnicow et al., 2004; Williams, Glanz, Kegler, & Davis Jr, 2012; Yeary, 2011). The components of the conceptual model also are grounded in the socio-ecological framework (Glanz et al., 2015) (see Figure 1). We conceptualize pastoral influence as incorporating factors that influence pastors as well as outcomes related to a pastor’s influence, which are moderated by personal, social, and environmental factors. Influencing factors occur at the individual-level (or pastoral level) as well as the church, community, and spiritual levels (Bopp & Fallon, 2011; Fallon et al., 2012; Harmon et al., 2013; Lewis et al., 2007; Proeschold-Bell et al., 2011; Webb et al., 2013a; Williams et al., 2012; Yeary, 2011). We also conceptualize how outcomes related to pastoral influence can occur at the pastoral, church, and community levels. As found in this study, outcomes of a pastor’s influence are contextual. Therefore, there are potential moderators of the associations between a pastor and outcomes related to individual stress (Chandler, 2009; Ferguson, Andercheck, Tom, Martinez, & Stroope, 2015; Forney, 2010; Irwin & Roller, 2000; McMinn et al., 2005; Wells, Probst, McKeown, Mitchem, & Whiejong, 2012), congregational health (Baruth et al., 2014; Baruth et al., 2008; Bopp & Webb, 2012; Dunn, Oliver, & Lyons, 2012; Fallon et al., 2012; Greenberg, 2000; Kegler et al., 2010; Quinn & McNabb, 2001; Stewart, 2015), and a pastor’s ability to reduce health disparities at the community level (Aaron, Levine, & Burstin, 2003; Ammerman et al., 2002; Baruth et al., 2008; Campbell et al., 2007; Harmon et al., 2012; Quinn & McNabb, 2001; Resnicow et al., 2004; Stewart, 2015). An arrow connects the outcomes of pastoral influence to influences on the pastor to acknowledge the reciprocal relationship that our participants described as existing between the two sides of pastoral influence.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Pastoral Influence

This study is the first to interview AA pastors and ask them about their influence more globally versus pertaining to a subset of their position (e.g., congregation, physical health, mental health) (Baruth et al., 2014; Leavey, Loewenthal, & King, 2007; Webb et al., 2013a). In addition, this is the first study to build a conceptual model based on the current literature related to pastoral influence. Findings from this study included only AA pastors who pastored Christian churches in South Carolina, USA. However, much of the research on clergy health has included primarily White clergy so findings from this study expand our understanding of pastoral influence to another racial group. In addition, the conceptual model incorporated literature that included a variety of racial/ethnic groups, pastor-focused literature, as well as findings from faith-based interventions that reported outcomes related to pastoral influence. Additional work is needed to examine whether the factors noted as contributing to a pastor’s influence remain valid in other countries and with faith leaders outside Christianity.

This study found AA pastors’ influence is rooted in higher levels of influence such as the historical context of the AA church, their denomination, and the divine nature of their position. AA pastors then build upon this foundation by developing relationships and trust with their congregation and community members. Despite their influence and important role, pastors may still need assistance incorporating health as a focus for their church and community work as well as self-care.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants of this study for sharing their time and insight. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Center on Minority and Health and Health Disparities Grant #R24MD002769-01.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Harmon declares that she has no conflict of interest. Ms. Strayhorn declares that she has no conflict of interest. Dr. Webb declares that he has no conflict of interest. Dr. Hebert declares that he has no conflict of interest.

References

- Aaron KF, Levine D, Burstin HR. African American church participation and health care practices. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18(11):908–913. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20936.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman A, Corbie-Smith G, St George DM, Washington C, Weathers B, Jackson-Christian B. Research expectations among African American church leaders in the PRAISE! project: a randomized trial guided by community-based participatory research. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(10):1720–1727. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman A, Washington C, Jackson B, Weathers B, Campbell M, Davis G, Switzer B. The PRAISE! project: A church-based nutrition intervention designed for cultural appropriateness, sustainability, and diffusion. Health promotion practice. 2002;3(2):286–301. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong K, McMurphy S, Dean LT, Micco E, Putt M, Halbert CH, Shea JA. Differences in the patterns of health care system distrust between blacks and whites. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(6):827–833. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0561-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett BD. Faith in the inner city: The urban Black church and students’ educational outcomes. The Journal of Negro Education. 2010;79(3):249–262. [Google Scholar]

- Baruth M, Bopp M, Webb B, Peterson J. The role and influence of faith leaders on health-related issues and programs in their congregation. Journal of Religion and Health. 2014;54(5):1747–1759. doi: 10.1007/s10943-014-9924-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baruth M, Wilcox S, Laken M, Bopp M, Saunders R. Implementation of a faith-based physical activity intervention: Insights from church health directors. Journal of Community Health. 2008;33(5):304–312. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp M, Baruth M, Peterson J, Webb B. Leading their flocks to health? Clergy health and the role of clergy in faith-based health promotion interventions. Family & Community Health. 2013;36(3):182–192. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e31828e671c[doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp M, Fallon E. Individual and institutional influences on faith-based health and wellness programming. Health Education Research. 2011;26(6):1107–1119. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp M, Webb B. Health Promotion in Megachurches An Untapped Resource With Megareach? Health promotion practice. 2012;13(5):679–686. doi: 10.1177/1524839911433466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp M, Webb B, Baruth M, Peterson J. Clergy perceptions of denominational, doctrine and seminary school support for health and wellness in churches. International Journal of Social Science Studies. 2014;2(1):189–199. doi: 10.11114/ijsss.v2i1.274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RK, Brown RE. Faith and works: Church-based social capital resources and African American political activism. Social Forces. 2003;82(2):617–641. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M, Hudson M, Resnicow K, Blakeney N, Paxton A, Baskin M. Church-based health promotion interventions: Evidence and lessons learned. Annual Review of Public Health. 2007;28:213–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MK, Demark-Wahnefried W, Symons M, Kalsbeek WD, Dodds J, Cowan A, McClelland JW. Fruit and vegetable consumption and prevention of cancer: the Black Churches United for Better Health project. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(9):1390–1396. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll J. God’s Potters. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Catanzaro A, Meador KG, Koenig HG, Kuchibhatla M, Clipp EC. Congregational health ministries: A national study of pastors’ views. Public Health Nursing. 2007;24(1):6–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System: Prevalence and trend data. 2009 Retrieved from http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/display.asp?cat=OB&yr=2009&qkey=4409&state=UB.

- Chandler DJ. Pastoral burnout and the impact of personal spiritual renewal, rest-taking, and support system practices. Pastoral Psychology. 2009;58(3):273–287. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. London, UK: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Church Health. 15th Annual Conference for Clergy and Congregational Leaders. 2016 Retrieved from https://churchhealth.org/event/15th-annual-conference-for-clergy-and-congregational-leaders/

- Cohall KG, Cooper BS. Educating American Baptist pastors: A national survey of church leaders. Journal of Research on Christian Education. 2010;19(1):27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WL. The role of African American churches in promoting health among congregations. Social Work and Christianity. 2015;42(2):193–204. [Google Scholar]

- Demark-Wahnefried W, McClelland JW, Jackson B, Campbell MK, Cowan A, Hoben K, Rimer BK. Partnering with African American churches to achieve better health: lessons learned during the Black Churches United for Better Health 5 a day project. Journal of Cancer Education. 2000;15(3):164–167. doi: 10.1080/08858190009528686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LL, Oliver J, Lyons MA. Faith Communities and Breast/Cervical Cancer Prevention: Results of a Rural Alabama Survey. Online Journal of Rural Nursing and Health Care. 2012;5(2):83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Fallon E, Bopp M, Webb B. Factors associated with faith-based health counselling in the United States: implications for dissemination of evidence-based behavioural medicine. Health & social care in the community. 2012;21(2):129–139. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson TW, Andercheck B, Tom JC, Martinez BC, Stroope S. Occupational conditions, self-care, and obesity among clergy in the United States. Social science research. 2015;49:249–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forney DG. A Calm in the Tempest: Developing Resilience in Religious Leaders. Journal of Religious Leadership. 2010;9(1):1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice. Vol. 5. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg A. The church and the revitalization of politics and community. Political Science Quarterly. 2000;115(3):377–394. [Google Scholar]

- Hall TW. The personal functioning of pastors: A review of empirical research with implications for the care of pastors. Journal of Psychology and Theology. 1997;25(2):240–253. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon BE, Adams SA, Scott D, Gladman YS, Ezell B, Hebert JR. Dash of faith: A faith-based participatory research pilot study. Journal of Religion and Health. 2012;53(3):747–759. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9664-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon BE, Blake CE, Armstead CA, Hebert JR. Intersection of identities. Food, role, and the African-American pastor. Appetite. 2013;67:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin CE, Roller RH. Pastoral preparation for church management. Journal of ministry marketing & management. 2000;6(1):53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac EP. The future of adult education in the urban African American church. Education and Urban Society. 2005;37(3):276–291. [Google Scholar]

- Kegler M, Escoffery C, Alcantara IC, Hinman J, Addison A, Glanz K. Perceptions of social and environmental support for healthy eating and physical activity in rural southern churches. Journal of Religion and Health. 2010;51(3):799–811. doi: 10.1007/s10943-010-9394-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein JB, Nguyen CT, Saffore L, Modlin C, Modlin CS. Racial disparities in urologic health care. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2010;102(2):108–117. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30498-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavey G, Loewenthal K, King M. Challenges to sanctuary: The clergy as a resource for mental health care in the community. Social science & medicine. 2007;65(3):548–559. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. Patterns of stress and support among Adventist clergy: Do pastors and their spouses differ? Pastoral Psychology. 2007;55(6):761–771. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CA, Turton DW, Francis LJ. Clergy work-related psychological health, stress, and burnout: An introduction to this special issue of Mental Health, Religion and Culture. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2007;10(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Link CL, McKinlay JB. Disparities in the prevalence of diabetes: Is it race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status? Results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey. Ethnicity and Disease. 2009;19(3):288–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamiya L. River of struggle, river of freedom: Trends among Black churches and Black pastoral leadership. 2006 Web Page. [Google Scholar]

- Markens S, Fox SA, Taub B, Gilbert ML. Role of Black churches in health promotion programs: lessons from the Los Angeles Mammography Promotion in Churches Program. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(5):805–810. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews AK, Sellergen SA, Manfriedi C, Williams M. Factors influencing medical information seeking among African American cancer patients. Journal of Health Communication. 2002;7(3):205–219. doi: 10.1080/10810730290088094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMinn MR, Lish RA, Trice PD, Root AM, Gilbert N, Yap A. Care for pastors: Learning from clergy and their spouses. Pastoral Psychology. 2005;53(6):563–581. [Google Scholar]

- Meek KR, McMinn MR, Brower CM, Burnett TD, McRay BW, Ramey ML, Villa DD. Maintaining personal resiliency: Lessons learned from evangelical protestant clergy. Journal of Psychology and Theology. 2003;31(4):339–347. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler MWN. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States 2011 With Special Feature on Socioeconomic Status and Health. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus11.pdf#glance. [PubMed]

- National Institute of Health. Fact Sheet-Health Disparities. 2013 Retrieved from http://report.nih.gov/NIHfactsheets/ViewFactSheet.aspx?csid=124.

- NVivo. QSR Version 2.0.161. Melbourne, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Plescia M, Herrick H, Chavis L. Improving health behaviors in an African American community: the Charlotte Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health project. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(9):1678–1684. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.125062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proeschold-Bell RJ, LeGrand S, James J, Wallace A, Adams C, Tool D. A theoretical model of the holistic health of United Methodist clergy. Journal of Religion and Health. 2011;50(3):700–720. doi: 10.1007/s10943-009-9250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proeschold-Bell RJ, Swift R, Moore HE, Bennett G, Li XF, Blouin R, Toole D. Use of a randomized multiple baseline design: rationale and design of the Spirited Life holistic health intervention study. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2013;35(2):138–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proeschold-Bell RJ, Turner EL, Bennett GG, Yao J, Li XF, Eagle DE, Moore HE. A 2-Year Holistic Health and Stress Intervention: Results of an RCT in Clergy. American Journal Of Preventive Medicine. 2017;53(3):290–299. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn MT, McNabb WL. Training lay health educators to conduct a church-based weight-loss program for African American women. The Diabetes educator. 2001;27(2):231–238. doi: 10.1177/014572170102700209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Campbell MK, Carr C, McCarty F, Wang T, Periasamy S, Stables G. Body and soul. A dietary intervention conducted through African-American churches. American Journal Of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27(2):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MS, Rosland AM, Keiffer EC, Sinco BR, Valerio M, Palmisano G, Heisler M. Effectiveness of a Community Health Worker Intervention Among African American and Latino Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(12):1–17. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JM. A developing framework for the development, implementation and maintenance of HIV interventions in the African American church. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2015;26(1):211–222. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2015.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Church-based informal support among elderly Blacks. The Gerontologist. 1986;26(6):637–642. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Ellison CG, Chatters LM, Levin JS, Lincoln KD. Mental health services in faith communities: The role of clergy in black churches. Social work. 2000;45(1):73–87. doi: 10.1093/sw/45.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrence WA, Phillips DS, Guidry JJ. The assessment of rural African-American churches’ capacity to promote health prevention activities. American Journal of Health Education. 2005;36(3):161–164. [Google Scholar]

- Two Feathers J, Kieffer EC, Palmisano G, Anderson M, Sinco B, Janz N, James SA. Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) Detroit partnership: improving diabetes-related outcomes among African American and Latino adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(9):1552–1560. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW, Davis RL. Accelerating the diffusion of innovations using opinion leaders. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1999;566(1):55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace AC, Proeschold-Bell RJ, Legrand S, James J, Swift R, Toole D, Toth M. Health programming for clergy: An overview of protestant programs in the United States. Pastoral Psychology. 2012;61(1):113–143. [Google Scholar]

- Webb B, Bopp M, Fallon EA. Factors associated with obesity and health behaviors among clergy. Journal of Health Behavior and Public Health. 2013a;3(1):20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Webb B, Bopp M, Fallon EA. A qualitative study of faith leaders’ perceptions of health and wellness. Journal of Religion and Health. 2013b;52(1):235–246. doi: 10.1007/s10943-011-9476-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells CR, Probst J, McKeown R, Mitchem S, Whiejong H. The relationship between work-related stress and boundary-related stress within the clerical profession. Journal of Religion and Health. 2012;51(1):215–230. doi: 10.1007/s10943-011-9501-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox S, Laken M, Anderson T, Bopp M, Bryant D, Carter R, Yancey A. The Health-e-AME faith-based physical activity initiative: Description and baseline findings. Health promotion practice. 2007;8(1):69–78. doi: 10.1177/1524839905278902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RM, Glanz K, Kegler MC, Davis E., Jr A study of rural church health promotion environments: leaders’ and members’ perspectives. Journal of Religion and Health. 2012;51(1):148–160. doi: 10.1007/s10943-009-9306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeary K. Religious Authority in African American Churches: A Study of Six Churches. Religions. 2011;2(4):628–648. [Google Scholar]