Abstract

Background

Palliative care units (PCU) staffed by specialty trained physicians and nurses have been established in a number of medical centers. The purpose of this study is to review the five-year experience of a PCU at a large, urban academic referral center.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed a prospectively-collected database of all admissions to the PCU at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in the first five years of its existence, from 2012 through 2017.

Results

Over these five years, there were 3321 admissions to the PCU. No single underlying disease process accounted for the majority of the patients, but the largest single category of patients were those with malignancy, who accounted for 38% of admissions. Transfers from the ICU accounted for 50% of admissions, with 43% of admissions from a hospital floor and 7% coming from the emergency department or a clinic. Median length of stay in the PCU was 3 days. In-hospital deaths occurred for 50% of admitted patients, while 38% of patients were discharged from the PCU to hospice.

Conclusion

These data show that a successful PCU is enabled by buy-in from a wide variety of referring specialists and by a multidisciplinary palliative care team focused on care of the actively dying patient as well as pain and symptom management, advance care planning, and hospice referral since a large proportion of referred patients do not die in house.

Keywords: Terminal Care, Palliative Care Unit, Hospice, Length of Stay, Outcome Evaluation, Palliative Care Consultation

INTRODUCTION

Palliative care is increasingly recognized as an integral part of the medical care of patients with life-threatening or life-limiting illnesses, and palliative care services are increasingly common in hospitals in the United States.(1) Provision of specialist palliative care has been demonstrated to improve quality of care and reduce costs in a number of settings.(2–5) Nevertheless, palliative care is a young field and models of delivery are still evolving. For inpatients, the dominant mode of specialist palliative care delivery is through consult services. In this model, the palliative care specialist serves as a consultant to the primary physician, making recommendations for care.

Creation of specialized palliative care units (PCUs) with nursing and physician staff specifically trained in palliative care represents a complementary approach to a consult service in providing expert palliative care services to inpatients. Since PCU’s are a relatively new phenomenon, best practices for managing these units and metrics for evaluation are in evolution.(6) Developing standards for high-quality specialist PCU’s requires learning from the experience of units from multiple different settings. Previous reports have described the experience of other PCUs with specific patient populations or over short periods.(7–14) This report reviews the experience of a PCU caring for a broad range of patients at an academic referral center with over 3,000 PCU admissions over five years.

PCU EXPERIENCE AT OTHER HOSPITALS

Reports of PCU characteristics at five other hospitals help to situate the Vanderbilt PCU in the context of the larger trend toward creating PCU’s nationally. Hui et al. reported the experience of the first five years of the PCU at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.(11) The 2568 patients admitted over this time had a median ages of 59 years and were all cancer patients. Over a quarter of their patients (28%) were directly admitted to the PCU, and the median PCU length of stay was 7 days. A third of their patients (33%) died during the admission, and a further 44% were discharged with hospice. At Dana Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center, Zhang et al. reported on 74 patients admitted to their PCU.(14) These patients had a median age of 61 years and were all cancer patients. Direct admissions accounted for 43% of these patients, and the median length of stay in the PCU was 8 days. Only 11% of these pateints died in the PCU, and 39% of patients were discharged to hospice.

Outside of cancer centers, Kellar et al. reported on 100 consecutive admissions to the PCU at Northwestern Medical Center.(12) These patients had a mean age of 67 years and 45% had cancer, with AIDS and neurological disorders making up the next largest groups of patients. Direct admissions accounted for 25% of their admissions. Death in the PCU occurred in 59% of the patients, and 36% were discharged to hospice. At Virginia Commonwealth University, Smith et al. reported on 237 patients admitted to the PCU.(13) A slight majority of these patients had cancer (52%), and no other diagnosis constituted more than 10% of admissions. Finally, Eti et al. reported on 1837 patients admitted to the PCU at Montefiore Medical Center.(10) These patients had a median age of 70 years, and a median PCU stay of 4 days. Of these patients, 27% died and 28% were discharged to hospice.

VANDRBILT PCU BACKGROUND INFORMATION

Setting

The opening of the Vanderbilt PCU was preceded by the development of a robust palliative care consultation service, staffed by board certified palliative care physicians and nurse practitioners. Unlike at many other institutions, where palliative care is incorporated within oncology or geriatrics, the Vanderbilt palliative care service is housed within the division of general internal medicine with a broad mandate to assist in patient management across diseases. The consult service began in 2006 and has grown in volume to an average of 220 new referrals per month. The institution’s experience with the consultation service led to a request from hospital administration and from ICU leadership that the palliative care service open a dedicated PCU and begin admitting patients. Six years after the creation of the palliative care consultation service, in September of 2012 a 12 bed designated palliative care unit was opened in one of the inpatient wards. All patients in the PCU have private rooms with chairs and pull out sleepers for families. The PCU does not limit visitor hours or numbers.

A palliative care physician directs the PCU. All PCU nurses receive formal training in palliative care using an educational curriculum based on End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium materials. In addition, PCU nurses continue to participate in mandatory didactics to ensure they maintain their palliative care skill set. The PCU is a closed unit that is staffed 24-hours a day during the week by a palliative care attending physician and on the weekends by either a palliative care attending or nurse practitioner with attending back-up. In-house coverage at night is provided by the hospitalist service with back up by a palliative care fellow and attending. All patients admitted to the PCU are seen on daily multidisciplinary rounds by the providers and nurses, along with a dedicated palliative care social worker, nurse case manager, and chaplain. Other providers see PCU patients as consultants at the discretion of the PCU attending physician. Beds on the PCU that are not filled by patients on the palliative care service are released as general medical beds for other primary teams. These patients are not seen by the PCU team unless a consult is requested.

Patient to nurse ratios in the PCU are generally 4:1, but may be decreased to 2:1 for increased patient acuity. In addition to routine hospital nursing care, the PCU nurses are trained to manage patients on mechanical ventilation, non-invasive positive pressure ventilation, high-flow oxygen, and vasoactive drips as long as there is no plan to escalate these interventions. Thus, patients who would normally require ICU care can be cared for in the PCU if their goals are consistent with comfort-focused care.

Patients

Patients are most commonly admitted to the PCU via transfer from another inpatient primary team. These primary teams initially request a consultation from the inpatient palliative care consult team. Criteria for admission of patients to the PCU are not rigid and instead rely on the judgment of the consulting palliative care provider and the attending for the PCU as to whether the patient’s care needs would best be met in the PCU. Most patients transferred to the PCU have terminal diagnoses and wish to discontinue or limit aggressive life-prolonging therapy, but this is not a requirement. Patients may be admitted to the PCU directly from the emergency department and or outpatient clinics.

Subsequent to the opening of the PCU, the palliative care service opened a dedicated palliative care outpatient clinic staffed by a physician and a nurse practitioner. Currently, these providers staff 12 half-days of dedicated palliative care clinic per week and also see patients within the specialty neurology clinics. Patients with pre-existing outpatient relationships with a Vanderbilt palliative care provider are often directly admitted to the PCU from an outpatient clinic, even while receiving active treatment for their malignancy.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective analysis of a prospectively collected database of patients admitted to the PCU. As a part of clinical care and quality improvement at the study institution, clinical personnel enter data on every patient seen as a consultation or admitted to the PCU into a prospectively maintained secure, online database via REDCap. Data collected includes demographic characteristics, information regarding the palliative care provider’s estimate of the patient’s life expectancy, and primary team’s reason for consultation. For patients transferred to the PCU, information about length of stay and discharge disposition is collected along with information about the presence of advanced care directives and documentation of code status.

The inclusion criterion for this analysis was admission to the PCU from the time of its opening in September 2012 until August 2017; there were no exclusion criteria. Included were 3,321 patient admissions to the PCU. Data were analyzed with Microsoft Excel to generate descriptive statistics, including counts, medians, means, and percentiles; hypothesis testing was not conducted. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Vanderbilt University with waiver of informed consent.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics

Between September of 2012 and August 2017, there were 3321 patient admissions to the PCU. A total of 83 patients were admitted two or more times. Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Mean age was 68 years. Most patients were non-Hispanic whites or African Americans.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Patients Admitted to the PCU

| Demographic Characteristic | n=3321 |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Men, no. (%) | 1730 (52%) |

|

| |

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 68 ± 24 |

|

| |

| Race and Ethnicity, no. (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 2636 (79%) |

| African American | 441 (13%) |

| Other Race/Ethnicity | 98 (3%) |

|

| |

| Married, no. (%) | 1458 (44%) |

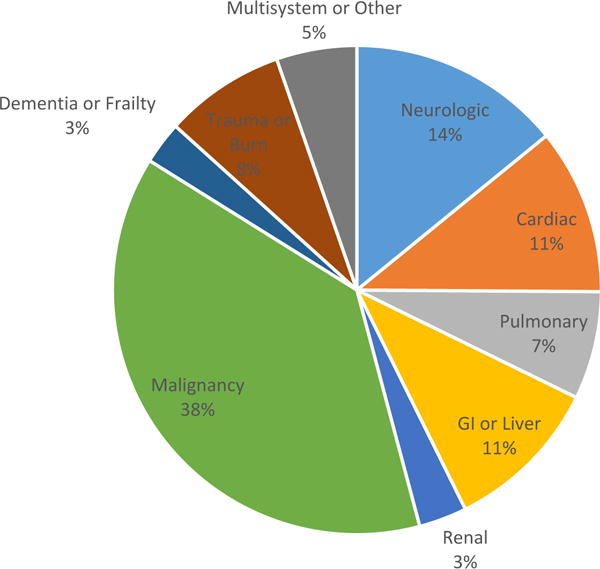

Figure 1 shows the breakdown for the primary life-limiting diagnosis for each admission to the PCU. Malignancy was the single largest primary diagnosis, accounting for 38% of all admissions. Neurologic (14%), cardiac (11%), and gastrointestinal/hepatic (11%) diagnoses each constituted over a tenth of admissions. Trauma/burn and pulmonary patients represented the next largest populations in the PCU.

Figure 1.

Primary Life Limiting Diagnoses for Patients Admitted to Palliative Care Unit

The majority of patients (74%) transferred to the PCU were completely bedbound when first evaluated by the palliative care team. Of patients transferred to the PCU, 1329 (39%) had an estimated life expectancy of under 7 days, 870 (26%) had a life expectancy of between 7 and 30 days, and 1111 (33%) had a life expectancy beyond 30 days in the estimation of the palliative care provider.

Characteristics of Hospital Stays before Transferring to PCU

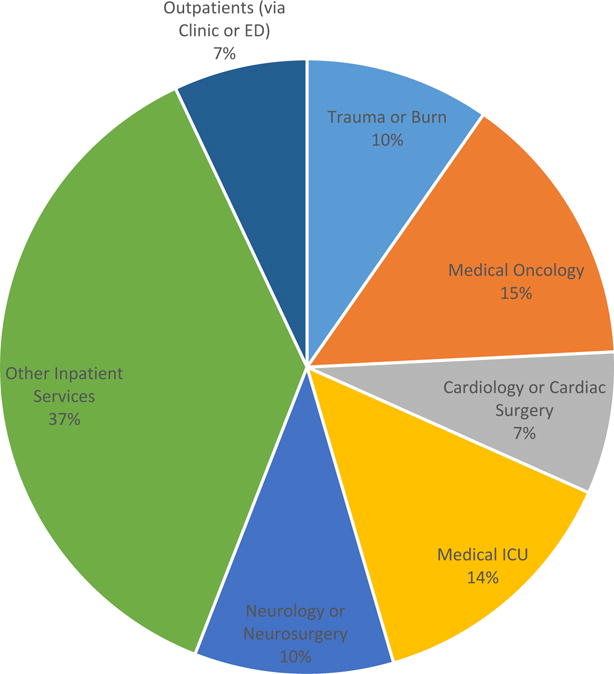

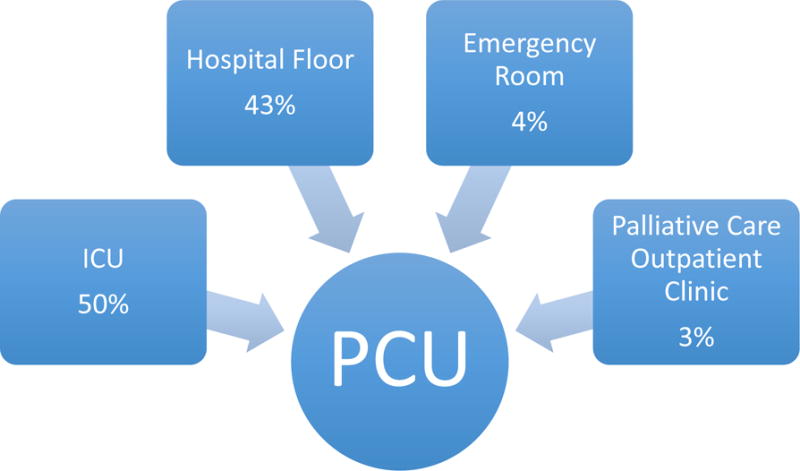

For patients admitted to the PCU, the median length of time between hospital admission and transfer to the PCU was 4 days [interquartile range, 1-8 days]. The primary services from which patients were transferred to the PCU is shown in Figure 2. Only 233 patients (7%) were admitted directly to the PCU from clinic or the emergency department, and 93% were initially admitted to another service prior to transfer to the PCU. The medical oncology and medical ICU services represented the largest referring services for patients transferred to the PCU. A total of 1675 patients (50%) were transferred to the PCU from an ICU, including the medical, surgical, cardiac, neurocare, and trauma ICUs at Vanderbilt (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Primary Services From Which Palliative Care Unit Patients Are Transferred

Figure 3.

Routes of Admission to the Vanderbilt PCU

All patients transferred to the PCU had an initial palliative care consultation initiated by the primary team. The reasons for consultation are given in Table 2. The most common reason for consultation for both floor patients and ICU patients was assistance in pain and symptom management, which was associated with 63% of the consults overall. The second most common reason for consultation (39% of overall consults) was to clarify goals of care. Almost a fifth of consults were placed for assistance with hospice placement. Only rarely did patients or family members request palliative care consultation.

Table 2.

Reasons for Initial Palliative Care Consultation

| Reason for Consultation*, no. (%) | n=3321 |

|---|---|

| Pain and Symptom Management | 2077 (63%) |

| Clarify Goals of Care | 1289 (39%) |

| Hospice Information or Referral | 626 (19%) |

| Patient or Family Request | 70 (2%) |

more than one reason could be associated with each consult

Characteristics of PCU Stay and Disposition

Patients had a median hospital length of stay of 7 days [IQR 4-12 days], of which a median of 3 days was spent in the PCU [IQR 1-4 days]. A total of 930 patients (28%) had an advance directive in place before transfer to the PCU, and during the PCU stay an additional 1546 patients (47%) completed an advance directive. Only 296 patients (9%) remained full code at the time of PCU transfer, and 209 of this 296 (71%) had code status changed to Do Not Resuscitate or Do Not Intubate/Do Not Resuscitate during their PCU admission.

Disposition from the PCU is given in Table 3. Approximately half of all patients died in the PCU. Of those alive at discharge, the majority were discharged from the hospital with hospice care, with a near even division between patients able to return home with hospice and those discharged to a facility with hospice care. Around 1% of patients were transferred from the PCU back to another inpatient service, primarily because goals changed and the patient or family preferred life-prolonging care that could not be provided in the PCU.

Table 3.

Disposition from the Palliative Care Unit

| Disposition Status, no. (%) | n=3321 |

|---|---|

| Death in the Hospital | 1674 (50%) |

| Home with Hospice | 661 (20%) |

| Facility with Hospice | 590 (18%) |

| Discharge without Hospice | 351 (11%) |

| Transfer to Another Unit | 36 (1%) |

DISCUSSION

This retrospective cohort study examining over 3000 patients admitted to an inpatient PCU over five years, found that PCU patients come from a wide variety of locations and services within the hospital, and that care in the PCU includes multiple domains of palliative care, including management of active dying, pain and symptom management, hospice referral, and advance care planning. These findings have important implication for the development, staffing, and management of inpatient PCUs at academic centers across the United States.

A successful PCU requires sufficient patients to fill the beds, which in turn requires good relationships with referring services. Prior to the opening of the Vanderbilt PCU, the palliative care consult service had built up rapport and interest for palliative care among other treating specialties. Since most patients were transferred from an ICU, developing good relationships with intensivists was crucial in order to identify patients who would be well-served by PCU transfer. Our PCU has the capabilities to provide interventions such as mechanical ventilation or administration of vasoactive drips. These capabilities allow patients who elect for comfort focused care to be transferred to the PCU before withdrawal of these life-supporting interventions. Such transfers allow the PCU to free up ICU beds that would otherwise be occupied with patients who have elected comfort care but are not ready to discontinue life support. The large proportion of patients transferred from ICU’s is consistent with experience at other centers, where PCU’s have resulted in fewer patients dying in ICU’s.(7)

One feature in our experience worth highlighting is the close working relationship between the palliative care team and the nurse practitioner team of our MICU. MICU nurse practitioners function as the only consistent, non-rotating providers in this unit, and a close relationship between them and the palliative care team has promoted the smooth transfer of care between teams when appropriate. As the MICU is the largest single referring service to the PCU, close integration between the MICU and PCU teams as well as the ability to continue some critical care interventions in the PCU has been critical to the success of the PCU in caring for these patients.

The plurality of patients with malignancy speaks to the importance of maintaining close working relationships between the oncology services and the palliative care service. At our institution, palliative care consultation is a routine part of a significant portion of inpatient oncology care, and palliative care providers share outpatient clinic space with oncologists. This integration of palliative care with oncologic care reflects the larger national integration of these two specialties.(15) This collegial atmosphere has created a relationship of trust in which oncologists feel comfortable having their patients transferred to the PCU when comfort-focused care is most appropriate.

Many of the studies describing PCU’s have been conducted at dedicated cancer hospitals.(8,9,11,14) However, it should be noted that the majority of patients in our PCU do not have malignancies. In addition to working with oncology and the MICU teams, the palliative care team has developed close relationships with the trauma service as well as the neurocare services, comprising neurology, neurosurgery, and neuro critical care. These groups have been some of the biggest referrers of patients to the PCU, and they were some of the strongest advocates for the opening of the PCU. This experience speaks to the importance of the palliative care team working closely with fields beyond oncology or geriatrics, where many palliative care teams are housed.

The growth of the outpatient palliative care unit has offered an opportunity for synergy with the PCU. The population in the palliative care clinic includes many patients with life-expectancies over six months who have significant symptom burdens and who have elected to limit the aggressiveness of further medical care. When these patients require hospitalization, they can be directly admitted to the PCU and thus receive care more in line with their goals and needs. The combination of palliative care clinic and PCU allows us to provide the appropriate care for patients who are not hospice eligible or not ready for hospice, but who do not benefit from the extensive work-ups and possible escalations of care that can be associated with visits to the emergency department or admission to other inpatient teams.

These data also show that the work done in the PCU runs the gamut of palliative care. About half of admissions to the PCU ended with the patient’s death, so end-of-life care forms a significant part of the work of the PCU. However, almost as many patients survive to discharge. For these patients, pain and symptom management, advanced care planning, and discharge planning are crucial.

This retrospective analysis of a single-center’s experience has obvious limitations in terms of its applicability to other centers. Certainly some of the ways we have designed our PCU are responses to idiosyncratic conditions at our center. Nevertheless, our experience, combined with that of other PCU’s reported in the literature, gives a picture of what PCU’s can accomplish and how they can be organized. This information gives valuable insight to those contemplating opening their own units, and it also can serve as preliminary data as new models of PCU organization are tested and best practices are elucidated.

References

- 1.Dumanovsky T, Augustin R, Rogers M, Lettang K, Meier DE, Morrison RS. The Growth of Palliative Care in U.S. Hospitals: A Status Report. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2016 Jan;19(1):8–15. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, Lyons KD, Hull JG, Li Z, et al. Early Versus Delayed Initiation of Concurrent Palliative Oncology Care: Patient Outcomes in the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015 May 1;33(13):1438–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morrison RS. Cost Savings Associated With US Hospital Palliative Care Consultation Programs. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008 Sep 8;168(16):1783. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison RS, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, Quill T, Sacco J, Tangeman J, et al. Palliative Care Consultation Teams Cut Hospital Costs For Medicaid Beneficiaries. Health Affairs. 2011 Mar 1;30(3):454–63. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 19;363(8):733–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Center to Advance Palliative Care Inpatient Unit Operational Metrics: Consensus Recommendations. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2009 Jan;12(1):21–5. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Digwood G, Lustbader D, Pekmezaris R, Lesser ML, Walia R, Frankenthaler M, et al. The impact of a palliative care unit on mortality rate and length of stay for medical intensive care unit patients. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2011 Dec;9(4):387–92. doi: 10.1017/S147895151100040X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drury PA-CL, Baccari PA-CK, Fang PA-CA, Mollder PA-CC, Nagus PA-CI. Providing Intensive Palliative Care on an Inpatient Unit: A Full-Time Job. Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology [Internet] 2016 Feb 1;7(1) doi: 10.6004/jadpro.2016.7.1.4. [cited 2017 Sep10]; Available from: http://advancedpractitioner.com/issues/volume-7,-number-1-%28janfeb-2016%29/providing-intensive-palliative-care-on-an-inpatient-unit-a-full-time-job.aspx. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elsayem A, Swint K, Fisch MJ, Palmer JL, Reddy S, Walker P, et al. Palliative Care Inpatient Service in a Comprehensive Cancer Center: Clinical and Financial Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004 May 15;22(10):2008–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eti S, O’Mahony S, McHugh M, Guilbe R, Blank A, Selwyn P. Outcomes of the Acute Palliative Care Unit in an Academic Medical Center. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 2014 Jun 1;31(4):380–4. doi: 10.1177/1049909113489164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hui D, Elsayem A, Palla S, De La Cruz M, Li Z, Yennurajalingam S, et al. Discharge Outcomes and Survival of Patients with Advanced Cancer Admitted to an Acute Palliative Care Unit at a Comprehensive Cancer Center. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2010 Jan;13(1):49–57. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kellar N, Martinez J, Finis N, Bolger A, von Gunten CF. Characterization of an acute inpatient hospice palliative care unit in a U.S. teaching hospital. J Nurs Adm. 1996 Mar;26(3):16–20. doi: 10.1097/00005110-199603000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith TJ, Coyne P, Cassel B, Penberthy L, Hopson A, Hager MA. A high-volume specialist palliative care unit and team may reduce in-hospital end-of-life care costs. J Palliat Med. 2003 Oct;6(5):699–705. doi: 10.1089/109662103322515202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H, Barysauskas C, Rickerson E, Catalano P, Jacobson J, Dalby C, et al. The Intensive Palliative Care Unit: Changing Outcomes for Hospitalized Cancer Patients in an Academic Medical Center. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2017 Mar;20(3):285–9. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, Alesi ER, Balboni TA, Basch EM, et al. Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Jan;35(1):96–112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]