Abstract

Male courtship in Drosophila melanogaster is a sexually dimorphic innate behavior that is hardwired in the nervous system. Understanding the neural mechanism of courtship behavior requires the anatomical and functional characterization of all the neurons involved. Courtship involves a series of distinctive behavioral patterns, culminating in the final copulation step, where sperms from the male are transferred to the female. The duration of this process is tightly controlled by multiple genes. The fruitless (fru) gene is one of the factors that regulate the duration of copulation. Using several intersectional genetic combinations to restrict the labeling of GAL4 lines, we found that a subset of a serotonergic cluster of fru neurons co-express the dopamine-synthesizing enzyme, tyrosine hydroxylase, and provide behavioral and immunological evidence that these neurons are involved in the regulation of copulation duration.

Keywords: courtship, copulation duration, Drosophila melanogaster, fruitless, serotonergic, dopaminergic

Introduction

Male courtship in Drosophila melanogaster is an innate behavior that involves several distinctive behavioral patterns. As the neural circuit responsible for courtship is hardwired genetically in the nervous system, courtship behavior is an excellent model for investigating the connection between genes, neural circuits, and behavior. Male courtship is initiated upon the recognition of a female. The male fly performs a courtship “ritual” that consists of a sequence of steps, including orientation, chasing, tapping, singing, and licking (Pavlou and Goodwin, 2013; Yamamoto and Koganezawa, 2013; Yamamoto et al., 2014). Once the female is receptive to the male, she slows down, and opens her vaginal plate (Rezaval et al., 2012, 2014). The male subsequently bends his abdomen, and attempts to copulate (Pavlou and Goodwin, 2013; Yamamoto and Koganezawa, 2013; Yamamoto et al., 2014). The final copulation step requires an intricate neuronal coordination of the copulatory muscles, an integration of sensory signals from the genitalia (Pavlou et al., 2016), and signals for ejaculation at the reproductive organs (Tayler et al., 2012). The proper coordination of these neuronal components leads to a regulated copulation duration that ensures successful mating (Pavlou and Goodwin, 2013; Yamamoto and Koganezawa, 2013; Yamamoto et al., 2014).

The duration of copulation is species-specific and multifactorial. Many genetic mutants have been reported to have abnormal copulation duration (Yamamoto et al., 1997). Indeed, the fru gene has been identified as an important regulator of copulation duration. Compared to normal males, classic semi-fertile fru mutants demonstrate marked variability in the duration of copulation, with copulation being longer on average (Lee et al., 2001). This suggests that a population of fru neurons, with heterogeneous effects, controls copulation duration. fru is well known for its role in the development of the neural circuit that controls male courtship behavior (Demir and Dickson, 2005). The transcript from one of the four promoters of fru is alternatively spliced in a sex-specific manner to produce a functional FruM protein in males (Ryner et al., 1996). The expression of FruM in approximately 2000 neurons of the fly nervous system is essential for the proper development of the male courtship neural circuit (Lee et al., 2000). While most fru-positive neurons are present in both males and females, FruM is only expressed in males (Ryner et al., 1996). Sexual dimorphisms of fru neurons include cell count (Kimura et al., 2005; Cachero et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2010), the volume of synaptic structures (Stockinger et al., 2005; Cachero et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2010), and dendritic arborization patterns (Kimura et al., 2005, 2008; Datta et al., 2008; Cachero et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2010). Anatomical descriptions of fru neurons have largely focused on the brain, while those from the ventral nerve cord and the periphery are missing or incomplete (Cachero et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2010). Functionally, evidence is emerging on the roles of subsets of fru neurons in courtship initiation (Kimura et al., 2008; Kohatsu et al., 2011), song production (Rideout et al., 2007; von Philipsborn et al., 2011), sensory integration (Datta et al., 2008; Koganezawa et al., 2010), copulation initiation (Latham et al., 2013; Pavlou et al., 2016), sperm transfer (Tayler et al., 2012), and copulation duration (Tayler et al., 2012; Latham et al., 2013).

Intersectional genetic techniques provide the opportunity to examine specific subsets of neurons, and Drosophila melanogaster has a wide range of genetic tools available (Luan et al., 2006; Bohm et al., 2010; Ting et al., 2011). In this study, we generated a library of about 200 enhancer-trap lines with specific expression of the FLP recombinase (FLP) in neuronal tissues. This FLP library was combined with fru-GAL4 to genetically dissect the circuit into smaller components, as only cells that express both GAL4 and FLP will be targeted. Using this strategy, we successfully restricted gene expression to a cluster of previously characterized sexually dimorphic serotonergic fru neurons in the abdominal ganglion. By combining the FLP library with other GAL4 lines that specifically target different neurotransmitter systems, we provide immunochemical and behavioral evidence that lead to novel insights into the neurochemistry and behavioral function of these serotonergic fru neurons.

Results

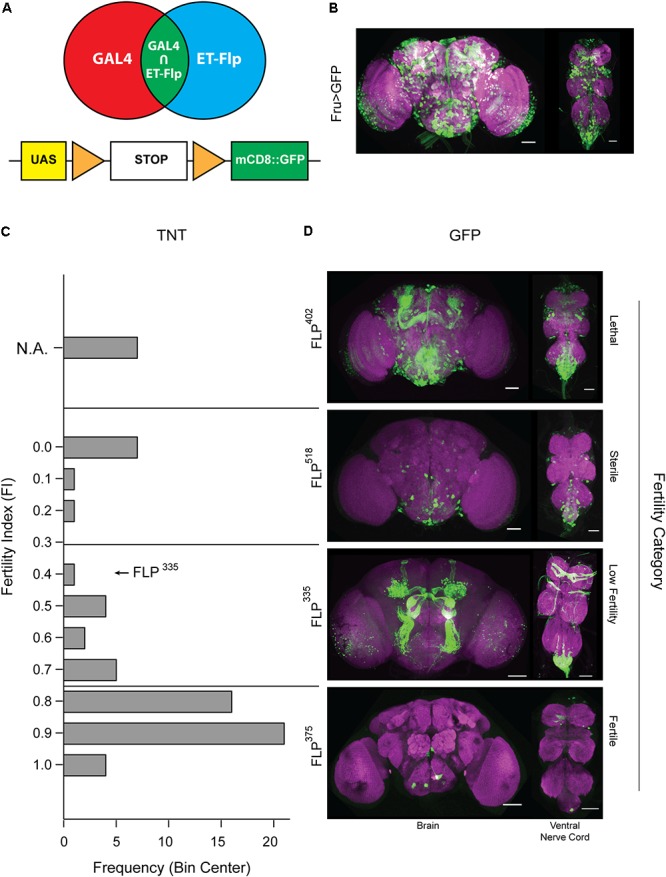

Genetic Dissection of the Fruitless Circuit

Over 2000 fru neurons are present in the adult male nervous system. These neurons have been shown to modulate nearly all aspects of the male courtship ritual. In order to identify restricted populations of fru neurons that are involved in the regulation of male copulatory behavior specifically, we used an intersectional genetic approach to combine the FLP lines that express FLP recombinase in neural tissues with a GAL4 line that labels the fru circuit (fru-GAL4) (Stockinger et al., 2005) (Figures 1A,B). A total of 67 FLP lines showed restricted GFP expression in subsets of fru neurons (Figure 1D). As fru neurons are well established in the regulation of male courtship, we asked how disrupting specific subsets of this circuit would affect courtship behavior. By combining individual FLP lines with fru-GAL4 and UAS>stop>TNT, we expressed TNT in specific subsets of fru neurons, thereby inactivating neural transmission from these neurons (Sweeney et al., 1995). All crosses produced progeny viable till eclosion. However, 7 FLP lines, that showed widespread FLP expression, produced males that died within 4 days after eclosion, suggesting that silencing the majority of fru neurons is lethal for adult males. Indeed, transgenic flies expressing TNT in all fru neurons (UAS-TNT; fru-GAL4) barely survive after eclosion (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Restrictive labeling of the fru-Gal4 line using the FLP library. (A) Schematic representation of our intersectional genetics approach using FLP and GAL4 to target fru subpopulations. (B) Expression pattern of the complete fru circuit in the CNS. (C,D) Tetanus toxin is expressed in fru neurons targeted by combining lines from the FLP library with UAS>stop>TNT and fru-GAL4. (Left Panel): Histogram depicting the fertility index distribution of the complete tetanus toxin screens containing 67 FLP lines that showed restricted GFP expression when combined with UAS>stop>mCD8::GFP and fru-GAL4. (Right Panel): Sample expression profile in each fertility category. Although the restricted fru expression profiles should be present in the full circuit image in (B), it may not be apparent due to variation in intensity and overlapping signals. Tissues were stained with anti-mCD8 (green) and anti-nC82 (magenta). Scale Bar = 50 μm.

Next, we performed a fertility screen, and tested whether males with different subsets of the fru circuit silenced display courtship defects when paired with wild-type females. We began by quantifying the percentage of pairings that successfully produced progeny, or the FI. Based on the FI values, the FLP library was divided into three distinct fertility categories (sterile, low fertility, and normal fertility). The FLP lines belonging to the normal fertility category showed GFP expression in a small number of neurons scattered throughout the central nervous system (CNS). Silencing these neurons is not expected to have a pronounced effect that could be observed in the fertility screen. On the other hand, males generated from FLP lines belonging to the sterile category showed clear locomotion defects, suggesting that their sterility is not attributable to deficiencies specific to courtship. All sterile lines showed widespread expression of GFP, indicating that these FLP lines targeted rather large portions of the fru circuit. Finally, we hypothesized that the low fertility category is likely to contain FLP lines that target subsets of fru neurons pertaining to courtship (Figures 1C,D). Within this group, we selected several lines that showed consistent restricted expression of GFP in fru neurons. With these lines, we then performed more detailed courtship assays to determine what aspect of the courtship ritual is affected when these subsets of fru neurons are silenced.

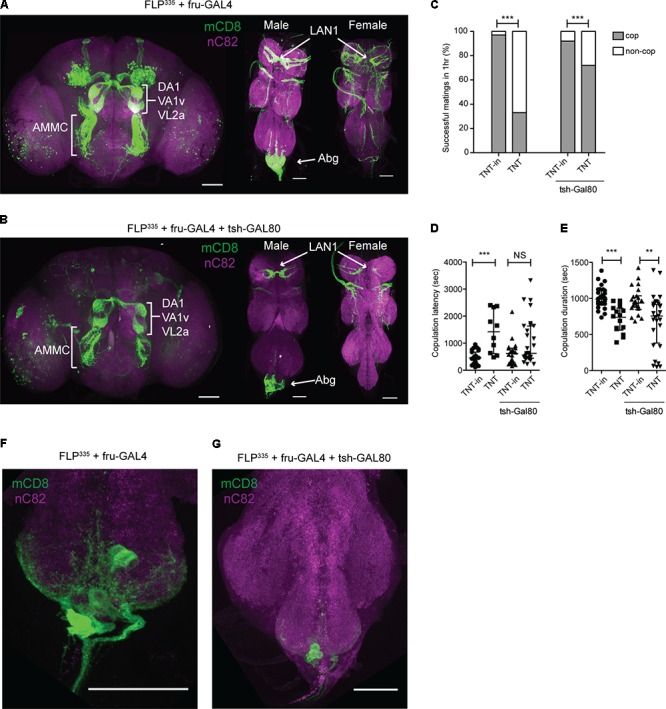

Identification of Subsets of Sexually Dimorphic fru Neurons That Impair Courtship and Copulatory Behaviors

We focused on one FLP line, FLP335, in the low fertility category that showed consistent restrictive labeling of several sexually dimorphic arborizations. Specifically, FLP335, fru>mCD8::GFP showed robust labeling of three classes of sensory projections that send sexually dimorphic projections into the CNS: (1) fru ORNs that project to the sexually dimorphic glomeruli (DA1, VA1v, and VL2a), which have been shown to be significantly larger in males (Stockinger et al., 2005); (2) fru GRNs (LAN1) that send sexually dimorphic midline crossing arbors into the contralateral prothoracic neuromere (Mellert et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2010); and (3) fru expression at the abdominal ganglion that consists of 13.4 ± 4.0 (n = 22) neurons and arborizations that may originate from the peripheral tissues (Figures 2A,F). Labeling of some neurons in the optic lobes (~67% of all dissected samples; n = 21) and a subset of Kenyon cells and their projections (~57% of all dissected samples; n = 21) was also observed, but they were less consistent (Table 1). In the ventral nerve cord, a few additional labeled neurons in the prothoracic ganglion were observed (Figure 2A). However, the labeling patterns of these neurons varied across individual preparations.

FIGURE 2.

FLP335 restricted labeling of fru-Gal4. (A) Expression profile of FLP335 fru-GAL4 UAS>stop>mCD8::GFP showing sexually dimorphic projections in the glomeruli from fru ORNs (DA1, VA1v, VL2a), projections in the antennal mechanosensory motor complex (AMMC) from fru JONs, sexually dimorphic projections in the prothoracic neuromere from fru LAN1 in the forelegs, and sexually dimorphic arbors in the abdominal neuromere (Abg). Tissues were stained with anti-mCD8 (green) and anti-nC82 (magenta). Scale Bar = 50 μm. (B) Expression profile of fru-GAL4, UAS>stop>mCD8::GFP, FLP335, tsh-GAL80. The addition of tsh-Gal80 transgene resulted in less expression in the ventral cord, particularly at the abdominal ganglion. (F,G) Magnified image of abdominal ganglion showing fru neurons. Immunofluorescence is reduced with the introduction of tsh-Gal80 (G). Tissues were stained with anti-mCD8 (green) and anti-nC82 (magenta). Scale Bar = 50 μm. (C–E) Effect of silencing FLP335 restricted labeling of fru-Gal4 with and without tsh-GAL80. (C) Percentage of successful matings in 1 h (FLP335, fru>TNTin: n = 33; FLP335, fru>TNT: n = 48; FLP335, fru>TNTin, tsh-GAL80: n = 24; FLP335, fru>TNT, tsh-GAL80: n = 40). ∗∗∗p = 0.0001, ∗∗∗p = 0.0004 by Fisher’s exact test. (D) Copulation latency (central line indicates the median; FLP335, fru>TNTin: n = 27; FLP335, fru>TNT: n = 10; FLP335, fru>TNTin, tsh-GAL80: n = 22; FLP335, fru>TNT, tsh-GAL80: n = 28). ∗∗∗p = 0.0002, n.s. = not significant by Mann–Whitney test. (E) Copulation duration (central line indicates the median; FLP335, fru>TNTin: n = 27; FLP335, fru>TNT: n = 16; FLP335, fru>TNTin, tsh-GAL80: n = 22; FLP335, fru>TNT, tsh-GAL80: n = 28). ∗∗∗p < 0.0001, ∗∗p = 0.0041 by Mann–Whitney test.

Table 1.

Summary of all genetic combinations, the corresponding expression pattern, and copulatory behavior discussed in this paper.

| Transgenes |

Expression Characterization with GFP | Functional Characterization by Neuronal Silencing with TNT |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAL4 | tsh-GAL80 | Percent Copulated in 1 h | Percent Change in Latency to Copulate Compared to Control (TNT vs. TNTin) | Percent Change in Copulation Duration Compared to Control (TNT vs. TNTin) | |

| fru | - | Sporadic expression in the optic lobes (~67% of all dissected samples, n = 21), MB (~57% of all dissected samples, n = 21) and, consistent expression of the glomeruli, AMMC, GRNs, Abg (13.4 ± 4.0 neurons in the abdominal ganglion, and arborizations from peripheral tissues) | ~30%∗∗∗ | ↑~300%∗∗∗ | ↓25%∗∗∗ |

| fru | + | Sporadic expression in the MB, Glomeruli, AMMC, GRNs, Abg (8.9 ± 2.5, n = 14 neurons in the abdominal ganglion and arborizations from peripheral tissues) | ~70%∗∗∗ | NS | ↓22%∗∗ |

| Orco | 80% of all ORNs (Wang et al., 2003) | 92% | NS | NS | |

| Ppk23 | GRN specific (Thistle et al., 2012) | 100% | NS | NS | |

| TRH | + | sAbg-1 (4 ± 1, n = 6 neurons in the abdominal ganglion) | 100% | NS | ↓10%∗∗ |

| TH | + | One pair of neurons in the anterior lateral protocerebral region of the brain, sAbg-1 (4 ± 2, n = 5 neurons in the abdominal ganglion) | 100% | NS | ↓9%∗ |

∗∗∗p < 0.0005, ∗∗p < 0.005, ∗p < 0.05, n.s., not significant. MB, mushroom body; AMMC, antennal mechanosensory motor complex; GRN, gustatory receptor neurons.

Consistent with the low fertility observed in our initial screen, FLP335, fru>TNT performed poorly in classical courtship assays as indicated by a significant reduction in the CI compared to controls (an inactive form of TNT, TNTin) (data not shown). Only 33% of males showed successful copulation within 1 h. Compared to controls, the latency to copulate was three times as long, and the copulation duration was significantly reduced by 25% (Figures 2C–E and Table 1). The low courtship intensity is likely due to the silencing of the sensory afferents.

To determine which targeted neurons are responsible for the observed courtship defects, we incorporated the tsh-GAL80 transgene to suppress GAL4 activity in the ventral nerve cord. tsh is an essential gene that determines the cellular identity of the ventral nerve cord (Fasano et al., 1991; Roder et al., 1992). The tsh-GAL80 was generated (Simpson, 2016) and had been used to silence GAL4 activity in the ventral nerve cord by multiple groups (Clyne and Miesenbock, 2008; Zhang et al., 2013; Andrews et al., 2014; Harris et al., 2015). The resulting males (FLP335, fru>mCD8::GFP, tsh-GAL80) retained most of the original GFP expression pattern in the central brain region. However, in the ventral nerve cord and abdominal ganglion, limited reduction in GFP expression was observed, with only 8.9 ± 2.5 (n = 14) neurons showing expression (Figures 2B,G, and Table 1). The addition of tsh-GAL80 eliminated some of the variability in GFP expression in the ventral nerve cord, particularly those outside of the posterior tip of the abdominal ganglion. Silencing these neurons (FLP335, fru>TNT, tsh-GAL80) resulted in a partial rescue of the copulation success and complete rescue of the latency phenotype, but the copulation duration was still significantly reduced (Figures 2C–E). Therefore, the copulation duration phenotype may be due to the silencing of the remaining neurons at the posterior tip of the abdominal ganglion or the peripheral neurons that project to the area.

However, FLP335, fru>TNT, tsh-GAL80 males also showed robust targeting of the fru ORNs, JONs, and GRNs. In order to rule out their contribution to the copulation phenotype, we swapped the fru-GAL4 line with other GAL4 lines that are known to specifically label these neuropils. Silencing the ORNs (FLP335, orco>TNT) (Wang et al., 2003) or GRNs (FLP335, ppk23>TNT) (Thistle et al., 2012) in males had little impact on the copulatory phenotypes (Supplementary Figure 1 and Table 1). We did not account for the effect of the antennal mechanosensory motor complex arborization projecting from the JONs, which is the auditory organ in flies, as hearing is dispensable for pre-copulation behavior (Markow, 1987), and unlikely to play a role in post-copulation behavior.

Copulation Duration Is Regulated by Sexually Dimorphic Serotonergic fru Neurons (sAbg-1) at the Posterior Tip of the Abdominal Ganglion

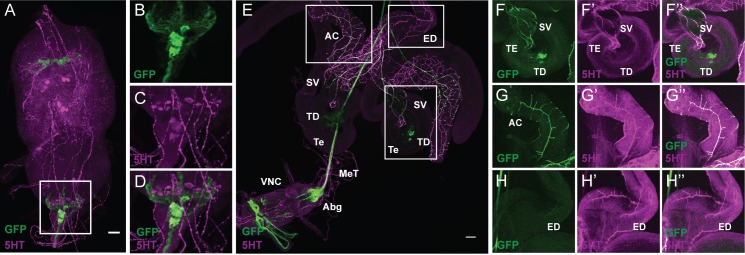

We identified a subset of fru neurons in the abdominal ganglion that are likely to be involved in the regulation of copulation duration. We next proceeded to identify the signaling mechanism of these neurons by using antibodies to label various neurotransmitters. We found that the subset of fru neurons in the abdominal ganglion are immunoreactive to antibodies against serotonin (5HT) (Figures 3A–D). Early characterization of fru neurons in the abdominal ganglion had previously identified 8–10 male-specific neurons that are immunoreactive to 5HT (s-Abg) (Lee and Hall, 2001; Lee et al., 2001; Billeter and Goodwin, 2004). With cell bodies located at the posterior tip of the abdominal ganglion, s-Abg sends axons through the MeT to the junction of the reproductive tissues that include pairs of AC, SVs, and the anterior end of the ED (Lee and Hall, 2001; Lee et al., 2001; Billeter and Goodwin, 2004). Indeed, immunostaining of FLP335, fru>mCD8::GFP, tsh-GAL80 males with anti-5HT confirmed that most of the targeted fru abdominal neurons were serotonergic (~86%, n = 6). As previously reported, these neurons send axons via the MeT to innervate the SV (Figures 3E,F) and the AC (Figures 3E,G). However, we did not observe GFP expression in the ED (Figures 3E,H). Therefore, the FLP335, fru-GAL4, tsh-GAL80 genetic combination targets a subset of s-Abg innervation at the male reproductive tissues. Hereafter, we will refer to this subset of serotonergic fru neurons as sAbg-1.

FIGURE 3.

FLP335 restricted expression of fru-GAL4 with tsh-GAL80 targeted a subset of abdominal serotonergic fru neurons. (A–D) Double staining of male VNC with anti-GFP (green) and anti-5HT (magenta) of a Z-stack projection. (E) Double staining of the male reproductive organs with anti-GFP (green) and anti-5HT (magenta). (F–H) Co-localization of GFP and 5HT signal at the seminal vesicle (F), the accessory glands (G), and the absence of GFP signal at the ejaculation duct (H). AC, accessory gland; ED, ejaculation duct; SV, seminal vesicle; TD, testicular duct; Te, testes; MeT, median trunk nerve; VNC, ventral nerve cord; Abg, abdominal ganglion. Scale Bar = 50 μm. The brightness of E had been adjusted in ImageJ so that the innervation at the peripheral tissues can be visualized [B: Mean Intensity in Red/Blue Channel (displayed as magenta) = 38.06 ± 41.28, Mean Intensity in Green Channel = 6.63 ± 15.75; E: Mean Intensity in Red/Blue Channel (displayed as magenta) = 20.53 ± 31.66, Mean Intensity in Green Channel = 11.62 ± 24.89].

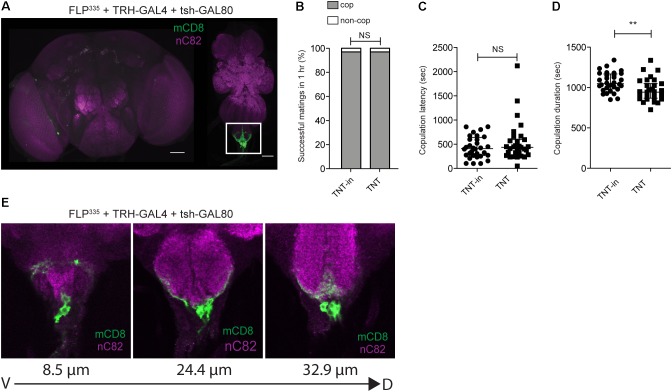

As FLP335,fru>TNT, tsh-GAL80 targets many neurons other than sAbg-1, to further confirm our hypothesis that sAbg-1 is responsible for the copulation duration phenotype, we replaced the fru-GAL4 transgene with the specific GAL4 transgene that targets the serotonergic system (TRH-GAL4). Colocalization of TRH>GFP and 5HT had been previously characterized (Alekseyenko et al., 2010). While most TRH+ cells in the abdominal ganglion do overlap with 5HT staining, we observed 7 ± 3 (n = 5) TRH- cells that stain with anti-5HT (Supplementary Figures 5E,F). The new genetic combination FLP335, TRH > mCD8::GFP, tsh-GAL80 should recapitulate the sAbg-1 expression pattern in the abdominal ganglion but demonstrate distinct patterns elsewhere. Compared to fru-GAL4, gene expression targeted by TRH-GAL4 in combination with FLP335 was much more restrictive, with no expression in the brain (Figure 4A). In the ventral cord, GFP expression was only observed in 4 ± 1 (n = 6) neurons in the abdominal ganglion (Figures 4A,E). We silenced these neurons by replacing GFP with TNT, and once again, performed copulation assays. Compared to the inactive TNT controls, FLP335, TRH>TNT, tsh-GAL80 males had a normal copulation success rate and latency, but copulation duration was still significantly reduced by ~10% (Figures 4B–D and Table 1). Collectively, these results show that the copulation duration phenotype is regulated by sAbg-1, which is a subset of the previously characterized serotonergic fru cluster in the abdominal ganglion.

FIGURE 4.

FLP335 and tsh-GAL80 restrictive labeling of the serotonergic GAL4 line. (A) Expression profile of FLP335 tsh-GAL80 TRH-GAL4 UAS>stop>mCD8::GFP showing exclusive targeting of neurons in the abdominal ganglion. (E) Magnified images of the abdominal ganglion at three different depths showing serotonergic cells. Tissues were stained with anti-mCD8 (green) and anti-nC82 (magenta). Scale Bar = 50 μm. (B–D) Effect of silencing FLP335 and tsh-GAL80 restrictive labeling of TRH-GAL4. (B) Percentage of successful matings in 1 h (FLP335, TRH>TNTin, tsh-GAL80: n = 33; FLP335, TRH>TNT, tsh-GAL80: n = 32). NS, not significant by Fisher’s exact test. (C) Copulation latency (central line indicates the median; FLP335, TRH>TNTin, tsh-GAL80: n = 32; FLP335, TRH>TNT, tsh-GAL80: n = 31). NS, not significant by Mann–Whitney test. (D) Copulation duration (central line indicates the median; FLP335, TRH>TNTin, tsh-GAL80: n = 32; FLP335, TRH>TNT, tsh-GAL80: n = 31). ∗∗p < 0.0019 by Mann–Whitney test.

The Copulation Time Regulating sAbg-1 Neurons Are Also Dopaminergic

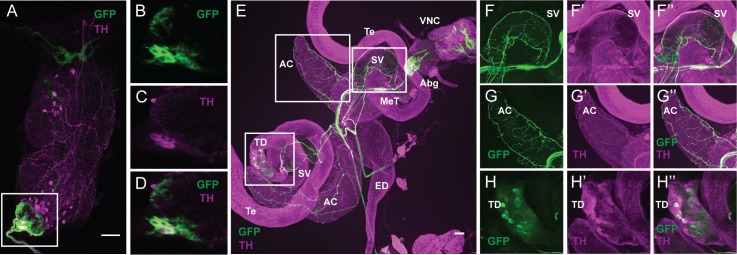

In our neurotransmitter antibody screening experiment with FLP335, fru>mCD8::GFP, tsh-GAL80 male tissues, we observed that most of the cell bodies of sAbg-1 (~79%, n = 8) are also immunoreactive to the dopamine (DA)-synthesizing enzyme, TH (Figures 5A–D). For comparison, without the FLP335 and tsh-GAL80 transgenes, TRH>GFP labels 34.3 ± 10 (n = 3) TRH+ cells in the abdominal ganglion, most (99%) of which showed colocalization with anti-TH (Supplementary Figures 5A,B). Although much weaker than 5HT staining, immunoreactivity to the TH antibody was observed at the axons of the MeT nerve (Figures 5E,F) that extended to innervate the AC (Figures 5E,G) and the SV (Figures 5E,F). Moreover, some cell-like TH+ expression was observed at the junction between the testes and SV (Figure 5E, near label TD, Figure 5H), but these cells did not co-stain with anti-5HT (Figure 3F). However, they did show GFP expression in the FLP335 restricted serotonergic reproductive tissues (FLP335, TRH>mCD8::GFP, tsh-GAL80) (Supplementary Figures 2A–D). Therefore, the negative staining of 5HT could reflect the low level of 5HT in these cells since TRH-GAL4 do target these cells. Finally as expected, all the sAbg-1 cells targeted by the FLP335 and TRH-GAL4 are also TH+ (Supplementary Figures 3A–M).

FIGURE 5.

The serotonergic sAbg-1 neurons are also dopaminergic. (A–D) FLP335 restricted expression of fru-GAL4 with tsh-GAL80. Double staining of the male VNC with anti-GFP (green) and anti-TH (magenta) of a Z-stack projection. (E) Double staining of the male reproductive organs with anti-GFP (green) and anti-TH (magenta). (F–H) Co-localization of GFP and TH signals at the seminal vesicle (F), the accessory glands (G), and some cell-like structure near the testicular duct at the junction between the testes and the seminal vesicle (H). AC, accessory gland; ED, ejaculation duct; SV, seminal vesicle; TD, testicular duct; Te, testes; MeT, median trunk nerve; VNC, ventral nerve cord; Abg, abdominal ganglion. Scale Bar = 50 μm.

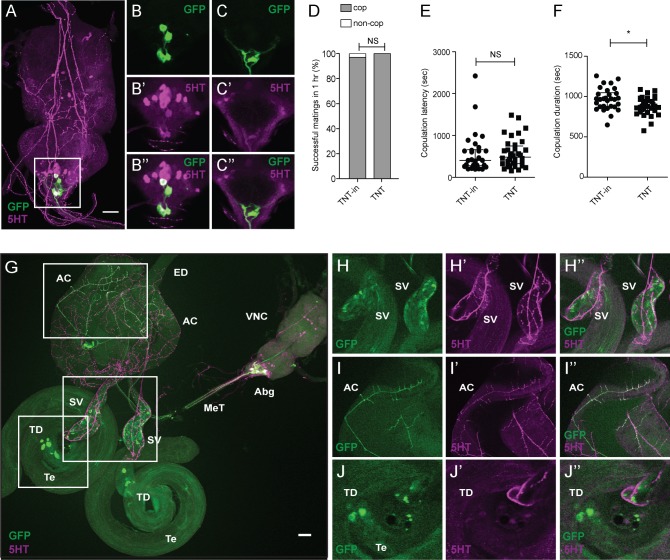

To confirm that sAbg-1 is also dopaminergic, we investigated whether the FLP335 restricted dopaminergic system would recapitulate sAbg-1 expression and lead to the same copulation phenotype when silenced by TNT. Interestingly, FLP335, TH>mCD8::GFP, tsh-GAL80 targeted only 4 ± 2 (n = 5) neurons in the ventral cord (Figure 6A). For comparison, without the FLP335 and tsh-GAL80 transgenes, TH>GFP in the abdominal ganglion showed 37.3 ± 10 (n = 4) TH+ cells, 6 ± 2 (~16%) showed colocalization with anti-5HT (Supplementary Figures 5C,D). Consistent with previous observations, these neurons showed GFP and 5HT co-localization, suggesting that they are the same population as the sAbg-1 neurons (Figures 6B,C). The expression level of 5HT in these cells is variable since cells located more posterior are weaker and cells that are more anterior show very intense staining (Figures 6A–C). As expected, co-localization was also observed in the sAbg-1 axons at the MeT, and TH+ neuronal innervation was observed at the same male reproductive tissues as described above (Figures 6G–J). Almost no expression was observed elsewhere in the nervous system (Supplementary Figure 4). When sAbg-1 restricted by TH-GAL4 and FLP335 was silenced by TNT, FLP335, TH>TNT, tsh-GAL80 males had a normal copulation success rate and latency, but copulation duration was still significantly reduced by ~9% (Figures 6D–F and Table 1). Taken together, these results show that the copulation duration phenotype we observed is regulated by sAbg-1, which utilizes both 5HT and DA as co-transmitters.

FIGURE 6.

FLP335 and tsh-GAL80 restrictive labeling of the dopaminergic GAL4 line. (A) FLP335 tsh-GAL80 TH-GAL4 UAS>stop>mCD8::GFP showing exclusive targeting of neurons that are double positive for GFP and 5HT at the abdominal ganglion. (B,C) Two different depths are shown to illustrate the co-localized signals. Tissues were stained with anti-mCD8 (green) and anti-5HT (magenta). Scale Bar = 50 μm. (D–F) Effect of silencing FLP335 and tsh-GAL80 restrictive labeling of TH-GAL4. (D) Percentage of successful matings in 1 h (FLP335, TH>TNTin, tsh-GAL80: n = 31; FLP335, TH>TNT, tsh-GAL80: n = 36). NS, not significant by Fisher’s exact test. (E) Copulation latency (central line indicates the median; FLP335, TH>TNTin, tsh-GAL80: n = 30; FLP335, TH>TNT, tsh-GAL80: n = 36). NS, not significant by Mann–Whitney test. (F) Copulation duration (central line indicates the median; FLP335, TH>TNTin, tsh-GAL80: n = 30; FLP335, TH>TNT, tsh-GAL80: n = 36). ∗p < 0.0172 by Mann–Whitney test. (G) Double staining experiment of the FLP335 tsh-GAL80 restricted GFP expression of TH-Gal4 male reproductive tissues with anti-GFP (green) and anti-5HT (magenta). (H–J) Co-localization of GFP and 5HT signals at the seminal vesicle (H), the accessory glands (I), and the cell-like structure near the testicular duct at the junction between the testes and the seminal vesicle (J). AC, accessory gland; ED, ejaculation duct; SV, seminal vesicle; TD, testicular duct; Te, testes; MeT, median trunk nerve; VNC, ventral nerve cord; Abg, abdominal ganglion.

Discussion

Classic fru mutants have different degrees of chromosomal lesions, resulting in different severity of courtship defects that correlate with the number of fru neurons expressing FruM within the fru circuit (Lee and Hall, 2001). As the expression of FruM is required for the normal development of fru neurons, different genetic combination of fru mutant heterozygotes would have defects in different regions of the fru circuit. Copulation duration of these classic fru mutant heterozygotes is on average longer, and has greater variability than that of wild-type flies (Lee et al., 2001). This suggests that the regulation of copulation time may involve a time-setting mechanism, with some neurons controlling the lengthening and others controlling the shortening of the duration. Together, these fru neurons function to ensure that copulation duration is tightly controlled. Here, we identified a small subset of ~4 fru neurons (sAbg-1) at the posterior tip of the abdominal ganglion that regulate copulation duration. When sAbg-1 is silenced by TNT, copulation duration is shortened. sAbg-1 is a subset (~50%) of the previously characterized serotonergic fru neurons at the abdominal ganglion, with similar innervation at the SV, AC, and near the testicular duct, but not the ED (Lee and Hall, 2001; Lee et al., 2001; Billeter and Goodwin, 2004). We discovered that sAbg-1 neurons are both serotonergic and dopaminergic, and confirmed this observation in four sets of experiments, making use of intersectional genetics, behavioral assays, and immunostaining.

The discovery that sAbg-1 neurons are both serotonergic and dopaminergic is surprising. Although evidence of neurotransmitter co-release has been previously described, most reported cases involve fast excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters or fast neurotransmitters coupled with slow neuromodulators (Hnasko and Edwards, 2012; Saunders et al., 2015). Co-release can be due to the ability of the VMAT to take up neurotransmitters released by another neuron. For example, striatal DA terminals in mammalian brain slices have been found to co-release both DA and 5HT (Zhou et al., 2005). The availability of 5HT released by a dopaminergic neuron is due to the non-specific uptake of excess 5HT, which accumulates at the DA terminals, by DA transporters that have low affinity for 5HT (Zhou et al., 2005). In the current case, the behavioral and anatomical evidence indicates that sAbg-1 neurons have the biosynthetic enzymes to synthesize both DA and 5HT. In Drosophila, VMAT is required for the storage and release of neurotransmitters in all aminergic neurons. Interestingly, when VMAT is expressed in the serotonergic system in a VMAT-null background, an increased level of DA is observed (Chen et al., 2013), suggesting an interaction or redundancy of the two aminergic systems in Drosophila. The physiological significance of the co-release of 5HT and DA from these neurons to modulate copulation duration is unclear. It is possible that the release of 5HT or DA is initiated by different signals. The relative activation of their cognate postsynaptic receptors may be one mechanism which regulates copulation duration.

Serotonergic fru neurons, to which sAbg-1 belongs, have been reported to express the receptor for the neuropeptide corazonin (CrzR). These neurons (fru/5HT/CrzR) receive inputs from a cholinergic subset of abdominal fru neurons that express corazonin. Upon activation, fru/5HT/CrzR neurons stimulate sperm transfer (Tayler et al., 2012). The fru/5HT/CrzR neurons are proposed to set the lower time limit of copulation duration, as their activation stimulates sperm ejaculation, and shortens copulation to only ~7 min (Tayler et al., 2012). Unlike the silencing of sAbg-1, which led to a shortened copulation duration, silencing of fru/5HT/CrzR by the expression of the inward rectifying potassium channel Kir, using either CrzR-GAL4 or Tph2-GAL4 (generated the same way as our TRH-GAL4), resulted in a normal copulation duration (Tayler et al., 2012). The difference is likely because of the additional silencing of the ED or other tissues that may be innervated by the other fru serotonergic neurons not part of sAbg-1.

Intriguingly we also observed that the fru neurons targeted by FLP335 tsh-GAL80 fru-GAL4 UAS>stop>TNT, which are almost all 5HT and TH positive, are necessary for normal fertility in addition to copulation duration (data not shown). It is not surprising given that these neurons innervate most of the male reproductive organs. However, we have also observed in other FLP lines where a reduction in copulation duration does not affect fertility. Thus, copulation duration regulated by fru neurons have different physiological purposes.

Copulation duration is multifactorial, and other mutants have been found to affect this parameter. Feminizing engrailed [encoding Engrailed (En)]-expressing fru neurons in the CNS result in a wide variation of copulation duration (Latham et al., 2013). These fru/En neurons within the abdominal ganglion use γ-aminobutyric acid, and therefore, are distinct from the sAbg-1 cluster described here (Latham et al., 2013). Null mutants of the clock genes per and tim have been reported to lengthen copulation duration, independent of the core clock mechanism (Beaver and Giebultowicz, 2004). We cannot rule out the involvement of per and tim playing a non-circadian regulatory role in the copulation phenotype that we observed.

The neural regulation of copulatory behaviors involves multiple neural circuits ranging from sensory inputs to motor controls. The systematic functional characterization of the fru circuit allows us to understand the neural mechanisms underlying copulatory behaviors. Our finding contributes to a better understanding of a complex neural circuit.

Materials and Methods

Fly Stocks

The following strains were used in this study: fru-GAL4 (Stockinger et al., 2005), UAS>stop>TNTin, UAS>stop>TNT (Stockinger et al., 2005), UAS>stop>mCD8::GFP (Yu et al., 2010), FLP from Liqun Luo (Department of Biology, Stanford University, CA, United States), tsh-GAL80 from Julie Simpson, TH-GAL4 from Serge Birman (Development Biology Institute of Marseille, Marseille, France), TRH-GAL4 (Alekseyenko et al., 2010), orco-GAL4, ppk23-GAL4, elavc155-GAL4, and the Canton-S strain from the Bloomington Stock Center, Bloomington, IN, United States.

Generation of Enhancer-Trap FLP Lines

Detailed procedures for the generation of the enhancer-trap FLP library has been described in a previous publication (Alekseyenko et al., 2013). A total of 356 enhancer-trap FLP lines (FLP) were generated by randomly inserting a FLP recombinase in chromosome II and III. Individual FLP lines were subsequently crossed to elavc155-GAL4; UAS>stop>mCD8::GFP to check for GFP expression. Approximately 200 lines that showed consistent expression in the nervous system in 1–3-day-old adult males were selected.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on samples from 3 to 7-day-old adult flies. Dissection and immunohistochemistry of the adult nervous system were performed as described previously (Mundiyanapurath et al., 2009), with some modifications in the primary and secondary antibodies used. Dissection of male reproductive organs was performed on Sylgard plates (Living Systems Instrumentation, St. Albans City, VT, United States) covered with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline. Dissected samples were fixed, and immunostaining was performed as described. The following primary and secondary antibodies were used in this study: rat polyclonal anti-mCD8 (1:100; Caltag, Burlingame, CA, United States), rabbit anti-GFP (1:600; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States), mouse anti-GFP (1:500, Thermo Fisher Scientific), mouse anti-nc82 (1:10; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA, United States) (Hofbauer et al., 2009), rabbit anti-FruM (1:2000) (kindly supplied by Dickson laboratory), rabbit anti-TH (1:500; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, United States; although the immunogen was derived from rat, its fly specific immunoreactivity has been reported in at least 4 publications (Venderova et al., 2009; Alekseyenko et al., 2010, 2013; Kuo et al., 2015), rabbit anit-5HT (1:500; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States), anti-rat IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific), goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647 (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594 (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Imaging and Expression Analysis

Images of the FLP expression pattern were acquired by Eclipse 90i (Nikon, Minato, Tokyo, Japan) fluorescence microscope using a 20× water-immersion objective. Structured illumination microscopy (Optigrid) was used to obtain optical sections (1.8 μM) of the whole central brain region. ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States) was used to generate the Z-stack projection of the FLP expression pattern.

Behavioral Assays

Husbandry

Flies were raised on standard cornmeal medium, and kept in a 12 h:12 h day:night cycle at 25°C in ambient relative humidity. Each newly enclosed adult was collected and aged for 3–7 days in an isolation vial (16 × 100-mm) supplied with ~2 ml of fly food. Virgin, wild-type Canton-S females were aged in groups of 20–40 for 3–7 days. All behavioral experiments were performed at 25°C with ~50% humidity, during the first 3 h after lights on.

Fertility Screen

The fertility screen was performed by adding a virgin Canton-S female to the isolation vial where the test male had been isolated. The pairs were allowed to interact for ~30 min, after which time the males were removed. After 4 (or more) days, any progeny from the pairing was recorded. The number of pairings that successfully produced progeny over the total number of pairings for each genotype is defined as the FI (n > 10).

Courtship Behavior

Courtship assays were performed using a chamber wheel with four compartments made of acrylic glass. Each compartment has a diameter of 3 cm and a height of 1 mm. A test male and a virgin female was each aspirated to each compartment, and video-recorded. The CI is the percentage of time the male spent courting the female in the 10 min after the female is added to the chamber (Villella and Hall, 2008). The courtship vigor index is similar to CI except the 10-min observation period begins after the first courtship event, thus delineating courtship latency from courtship intensity (Krstic et al., 2009). Copulation duration is defined as the duration of the complete copulation event. Latency to court is the time taken when the first courtship event is observed. Latency to copulate is the time taken when copulation is successful.

Copulation Assay

Copulation assays were performed in 12-well plates (Falcon, Corning Inc., Corning, NY, United States) with ~2 ml standard fly food to maintain humidity in each well. An experimental male was paired with a virgin Canton-S female, and the courtship behavior was video-recorded for at least 1 h. Any pair that did not copulate during a 1-h period was considered unsuccessful in copulation, and was not included in the calculation of copulation latency or duration. Copulation latency was determined to be the time from the beginning of pairing to the time at which successful copulation was observed. Copulation duration was measured from the start of the first successful mounting to the dismounting of the male from the female.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 5.0b) For mating success experiments, the percentage of males of each genotype that succeeded in mating with a wild type virgin female within a 1-h window was compared using Fisher’s exact test (Figures 2C, 4B, 6D and Supplementary Figure 1A) (∗p < 0.01, ∗∗p < 0.005, ∗∗∗p < 0.0001). For all copulation latency and copulation duration tests described, values obtained for experimental males where compared with those of control males using a Mann–Whitney test (Figures 2D,E, 4C,D, 6E,F and Supplementary Figures 1B,C) (∗p < 0.01, ∗∗p < 0.005, ∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

Author Contributions

AL and YC conceived, designed, and performed the experiments. AL wrote the manuscript with support from MF. SJ performed the experiments. All authors provided critical feedback and helped design the research, analysis, and manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank our mentor Edward Kravitz for providing the resources and guidance to pursue this project. We thank Barry Dickson, Liqun Luo, Julie Simpson, and the Bloomington Stock Center for fly stocks; Kathy Siwicki for her help and advice on courtship behavior experiments; past members of the Kravitz laboratory (Olga Alekseyenko, Sarah Certel, Jill Penn, and Joanne Yew) and Darrell Mousseau for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations

- 5HT

serotonin

- AC

accessory gland

- CI

courtship index

- CrzR

corazonin receptor

- DA

dopamine

- ED

ejaculation duct

- En

engrailed

- FI

fertility index

- FLP

enhancer trap-FLP recombinase

- fru

fruitless

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GRN

gustatory receptor neuron

- MeT

median trunk nerve

- ORN

olfactory receptor neuron

- per

period

- SV

seminal vesicle

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- tim

timeless

- TNT

tetanus toxin light chain

- VMAT

vesicular monoamine transporter

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grants R01 GM099883, R01 GM074675, and R35 GM118137 [all to Edward A. Kravitz (Principal Investigator)]. These funders played no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. We also acknowledge the support of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Funding Reference No. RGPIN-2014-06012), Cette recherche a été finance par le Conseil de recherches en sciences naturelles et en genie du Canada (Numéro de Reference: RGPIN-2014-06012), Canadian Foundation for Innovation, John R. Evans Leaders Opportunity Fund, and internal funding support from the Western College of Medicine and College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan [all to Adelaine K. W. Leung (Principal Investigator)].

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2018.00780/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alekseyenko O. V., Chan Y. B., Li R., Kravitz E. A. (2013). Single dopaminergic neurons that modulate aggression in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 6151–6156. 10.1073/pnas.1303446110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alekseyenko O. V., Lee C., Kravitz E. A. (2010). Targeted manipulation of serotonergic neurotransmission affects the escalation of aggression in adult male Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS One 5:e10806. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews J. C., Fernandez M. P., Yu Q., Leary G. P., Leung A. K., Kavanaugh M. P., et al. (2014). Octopamine neuromodulation regulates Gr32a-linked aggression and courtship pathways in Drosophila males. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004356. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaver L. M., Giebultowicz J. M. (2004). Regulation of copulation duration by period and timeless in Drosophila melanogaster. Curr. Biol. 14 1492–1497. 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billeter J. C., Goodwin S. F. (2004). Characterization of Drosophila fruitless-gal4 transgenes reveals expression in male-specific fruitless neurons and innervation of male reproductive structures. J. Comp. Neurol. 475 270–287. 10.1002/cne.20177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohm R. A., Welch W. P., Goodnight L. K., Cox L. W., Henry L. G., Gunter T. C., et al. (2010). A genetic mosaic approach for neural circuit mapping in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 16378–16383. 10.1073/pnas.1004669107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachero S., Ostrovsky A. D., Yu J. Y., Dickson B. J., Jefferis G. S. (2010). Sexual dimorphism in the fly brain. Curr. Biol. 20 1589–1601. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A., Ng F., Lebestky T., Grygoruk A., Djapri C., Lawal H. O., et al. (2013). Dispensable, redundant, complementary, and cooperative roles of dopamine, octopamine, and serotonin in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 193 159–176. 10.1534/genetics.112.142042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyne J. D., Miesenbock G. (2008). Sex-specific control and tuning of the pattern generator for courtship song in Drosophila. Cell 133 354–363. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S. R., Vasconcelos M. L., Ruta V., Luo S., Wong A., Demir E., et al. (2008). The Drosophila pheromone cVA activates a sexually dimorphic neural circuit. Nature 452 473–477. 10.1038/nature06808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir E., Dickson B. J. (2005). fruitless splicing specifies male courtship behavior in Drosophila. Cell 121 785–794. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasano L., Roder L., Core N., Alexandre E., Vola C., Jacq B., et al. (1991). The gene teashirt is required for the development of Drosophila embryonic trunk segments and encodes a protein with widely spaced zinc finger motifs. Cell 64 63–79. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90209-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R. M., Pfeiffer B. D., Rubin G. M., Truman J. W. (2015). Neuron hemilineages provide the functional ground plan for the Drosophila ventral nervous system. eLife 4:e04493. 10.7554/eLife.04493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnasko T. S., Edwards R. H. (2012). Neurotransmitter corelease: mechanism and physiological role. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 74 225–243. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofbauer A., Ebel T., Waltenspiel B., Oswald P., Chen Y. C., Halder P., et al. (2009). The wuerzburg hybridoma library against Drosophila brain. J. Neurogenet. 23 78–91. 10.1080/01677060802471627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K., Hachiya T., Koganezawa M., Tazawa T., Yamamoto D. (2008). Fruitless and doublesex coordinate to generate male-specific neurons that can initiate courtship. Neuron 59 759–769. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K., Ote M., Tazawa T., Yamamoto D. (2005). Fruitless specifies sexually dimorphic neural circuitry in the Drosophila brain. Nature 438 229–233. 10.1038/nature04229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koganezawa M., Haba D., Matsuo T., Yamamoto D. (2010). The shaping of male courtship posture by lateralized gustatory inputs to male-specific interneurons. Curr. Biol. 20 1–8. 10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohatsu S., Koganezawa M., Yamamoto D. (2011). Female contact activates male-specific interneurons that trigger stereotypic courtship behavior in Drosophila. Neuron 69 498–508. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krstic D., Boll W., Noll M. (2009). Sensory integration regulating male courtship behavior in Drosophila. PLoS One 4:e4457. 10.1371/journal.pone.0004457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo S. Y., Wu C. L., Hsieh M. Y., Lin C. T., Wen R. K., Chen L. C., et al. (2015). PPL2ab neurons restore sexual responses in aged Drosophila males through dopamine. Nat. Commun. 6:7490. 10.1038/ncomms8490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham K. L., Liu Y. S., Taylor B. J. (2013). A small cohort of FRU(M) and Engrailed-expressing neurons mediate successful copulation in Drosophila melanogaster. BMC Neurosci. 14:57. 10.1186/1471-2202-14-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G., Foss M., Goodwin S. F., Carlo T., Taylor B. J., Hall J. C. (2000). Spatial, temporal, and sexually dimorphic expression patterns of the fruitless gene in the Drosophila central nervous system. J. Neurobiol. 43 404–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G., Hall J. C. (2001). Abnormalities of male-specific FRU protein and serotonin expression in the CNS of fruitless mutants in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 21 513–526. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00513.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G., Villella A., Taylor B. J., Hall J. C. (2001). New reproductive anomalies in fruitless-mutant Drosophila males: extreme lengthening of mating durations and infertility correlated with defective serotonergic innervation of reproductive organs. J. Neurobiol. 47 121–149. 10.1002/neu.1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan H., Peabody N. C., Vinson C. R., White B. H. (2006). Refined spatial manipulation of neuronal function by combinatorial restriction of transgene expression. Neuron 52 425–436. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markow T. A. (1987). Behavioral and sensory basis of courtship success in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84 6200–6204. 10.1073/pnas.84.17.6200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellert D. J., Knapp J. M., Manoli D. S., Meissner G. W., Baker B. S. (2010). Midline crossing by gustatory receptor neuron axons is regulated by fruitless, doublesex and the Roundabout receptors. Development 137 323–332. 10.1242/dev.045047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundiyanapurath S., Chan Y. B., Leung A. K., Kravitz E. A. (2009). Feminizing cholinergic neurons in a male Drosophila nervous system enhances aggression. Fly 3 179–184. 10.4161/fly.3.3.8989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlou H. J., Goodwin S. F. (2013). Courtship behavior in Drosophila melanogaster: towards a ’courtship connectome’. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 23 76–83. 10.1016/j.conb.2012.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlou H. J., Lin A. C., Neville M. C., Nojima T., Diao F., Chen B. E., et al. (2016). Neural circuitry coordinating male copulation. eLife 5:e20713. 10.7554/eLife.20713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaval C., Nojima T., Neville M. C., Lin A. C., Goodwin S. F. (2014). Sexually dimorphic octopaminergic neurons modulate female postmating behaviors in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 24 725–730. 10.1016/j.cub.2013.12.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaval C., Pavlou H. J., Dornan A. J., Chan Y. B., Kravitz E. A., Goodwin S. F. (2012). Neural circuitry underlying Drosophila female postmating behavioral responses. Curr. Biol. 22 1155–1165. 10.1016/j.cub.2012.04.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout E. J., Billeter J. C., Goodwin S. F. (2007). The sex-determination genes fruitless and doublesex specify a neural substrate required for courtship song. Curr. Biol. 17 1473–1478. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roder L., Vola C., Kerridge S. (1992). The role of the teashirt gene in trunk segmental identity in Drosophila. Development 115 1017–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryner L. C., Goodwin S. F., Castrillon D. H., Anand A., Villella A., Baker B. S., et al. (1996). Control of male sexual behavior and sexual orientation in Drosophila by the fruitless gene. Cell 87 1079–1089. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81802-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders A., Granger A. J., Sabatini B. L. (2015). Corelease of acetylcholine and GABA from cholinergic forebrain neurons. eLife 4:e06412. 10.7554/eLife.06412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J. H. (2016). Rationally subdividing the fly nervous system with versatile expression reagents. J. Neurogenet. 30 185–194. 10.1080/01677063.2016.1248761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockinger P., Kvitsiani D., Rotkopf S., Tirian L., Dickson B. J. (2005). Neural circuitry that governs Drosophila male courtship behavior. Cell 121 795–807. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney S. T., Broadie K., Keane J., Niemann H., O’kane C. J. (1995). Targeted expression of tetanus toxin light chain in Drosophila specifically eliminates synaptic transmission and causes behavioral defects. Neuron 14 341–351. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90290-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayler T. D., Pacheco D. A., Hergarden A. C., Murthy M., Anderson D. J. (2012). A neuropeptide circuit that coordinates sperm transfer and copulation duration in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 20697–20702. 10.1073/pnas.1218246109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thistle R., Cameron P., Ghorayshi A., Dennison L., Scott K. (2012). Contact chemoreceptors mediate male-male repulsion and male-female attraction during drosophila courtship. Cell 149 1140–1151. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting C. Y., Gu S., Guttikonda S., Lin T. Y., White B. H., Lee C. H. (2011). Focusing transgene expression in Drosophila by coupling Gal4 with a novel split-LexA expression system. Genetics 188 229–233. 10.1534/genetics.110.126193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venderova K., Kabbach G., Abdel-Messih E., Zhang Y., Parks R. J., Imai Y., et al. (2009). Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 interacts with parkin, DJ-1 and PINK-1 in a Drosophila melanogaster model of Parkinson’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18 4390–4404. 10.1093/hmg/ddp394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villella A., Hall J. C. (2008). Neurogenetics of courtship and mating in Drosophila. Adv. Genet. 62 67–184. 10.1016/S0065-2660(08)00603-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Philipsborn A. C., Liu T., Yu J. Y., Masser C., Bidaye S. S., Dickson B. J. (2011). Neuronal control of Drosophila courtship song. Neuron 69 509–522. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. W., Wong A. M., Flores J., Vosshall L. B., Axel R. (2003). Two-photon calcium imaging reveals an odor-evoked map of activity in the fly brain. Cell 112 271–282. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00004-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto D., Jallon J. M., Komatsu A. (1997). Genetic dissection of sexual behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 42 551–585. 10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto D., Koganezawa M. (2013). Genes and circuits of courtship behaviour in Drosophila males. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14 681–692. 10.1038/nrn3567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto D., Sato K., Koganezawa M. (2014). Neuroethology of male courtship in Drosophila: from the gene to behavior. J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sens. Neural Behav. Physiol. 200 251–264. 10.1007/s00359-014-0891-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. Y., Kanai M. I., Demir E., Jefferis G. S., Dickson B. J. (2010). Cellular organization of the neural circuit that drives Drosophila courtship behavior. Curr. Biol. 20 1602–1614. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Branch A., Shen P. (2013). Octopamine-mediated circuit mechanism underlying controlled appetite for palatable food in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 15431–15436. 10.1073/pnas.1308816110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F. M., Liang Y., Salas R., Zhang L., De Biasi M., Dani J. A. (2005). Corelease of dopamine and serotonin from striatal dopamine terminals. Neuron 46 65–74. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.