Abstract

Purpose

To report a case of prolonged placement of a lacrimal silicone tube for 20 years, with evaluation of the lacrimal duct using lacrimal micro-endoscopy and inspection of deformation of the lacrimal tube.

Observations

This study involved a case of dacryocystitis in which a silicone tube had been placed in the patient 20-years previous and that was treated conservatively. Although granulation tissue formation due to dacryocystitis in the lacrimal duct was observed under lacrimal micro-endoscopy, subjective and objective resolution of symptoms, including granulated tissue formation, was achieved after removal of the silicone tube and conservative medical treatment. Follow-up examinations performed over a 12-month period post treatment revealed no recurrence of epiphora or anatomical obstruction. Inspection of the lacrimal tube using the tension test revealed minimal changes in the tube in situ for 20 years.

Conclusions and Importance

The findings in this case suggest both the lacrimal system and the silicone tube are tolerant to prolonged intubation, as long as the tube had been placed properly with careful observation. Our findings may encourage physicians to consider prolonged intubation for select cases of nasolacrimal duct obstruction.

Keywords: Silicone tube, Lacrimal obstruction, Deformation, Micro-lacrimal endoscopy, Prolonged tube placement, Granulation

1. Introduction

Primary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction (PANDO) is the most common cause of epiphora in adults. Dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) is the primary treatment choice for PANDO cases, however, silicone intubation has become an established alternative treatment option since first developed in 1968.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

In PANDO cases, the silicone tube should be placed in the lacrimal duct until the damaged mucosa has become re-epithelialized in order to avoid recurrence of the nasolacrimal duct obstruction; however, the appropriate time period for removal of the tube has yet to be standardized. Previously reported timing for the removal varies from 1 week to several years, with 2- to 6-months post intubation being the most common timing over the past 2 decdes.4,8, 9, 10, 11 It is a commonly held opinion that severe cases of PANDO need prolonged intubation to allow re-epithelialization and prevent recurrence.7

Here we report a case of PANDO in which the silicone tube was neglected for 20-years post intubation, which to the best of our knowledge, is the longest latency period in comparison with the previously published reports. In this present case, the surgical outcome post tube removal, along with evaluation of the lacrimal mucosa by use of a micro-lacrimal endoscope and inspection of the deformation of the removed tube, were investigated.

2. Findings

A 72-year-old male presented with epiphora and discharge in his left eye that had been occurring for 2 weeks. He had been treated for sinus surgery on his left side 20-years previous, and lacrimal intubation was simultaneously performed to prevent secondary lacrimal duct obstruction. Post surgery, the patient had never undergone follow-up examination with an ophthalmologist. Upon initial visit at our clinic, examination by computed tomography (CT), nasal endoscopy, and lacrimal micro-endoscopy revealed an open lacrimal passage and proper placement of the silicone tube (Fig. 1, Fig. 2A). Although no obvious damage to the lacrimal duct due to the previous surgery was detected, dacyrocystitis with biofilm formation around the tube, complicated with granulated tissue formation in the nasolacrimal duct, was observed (Fig. 2-B). Thus, we began a conservative treatment regimen that involved a weekly irrigation and instillation of antibiotic eye drops, which settled the inflammation within 3 weeks, followed by tube removal. The removed tube was identified as a standard-type Nunchaku-style silicone tube (NST; Kaneka Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Following the removal of the tube, the patient expressed that he felt symptom free, and lacrimal micro-endoscopy examination at 1-month after tube removal showed rapid resolution of the granulated tissue. At 6-months after tube removal, endoscopic examination revealed complete recovery of the healthy mucosa (Fig. 2-C and D). Follow-up examinations performed over a 12-month period post treatment revealed no recurrence of obstruction or dacryocystitis.

Fig. 1.

Clinical photographs of the puncta (A), including a view of the inferior nasal meatus using nasal endoscopy (B) and a computed tomography (CT) scan (C). Proper insertion of a Nunchaku-style silicone tube is shown (arrows), with slight punctal slitting of the lower puncta.

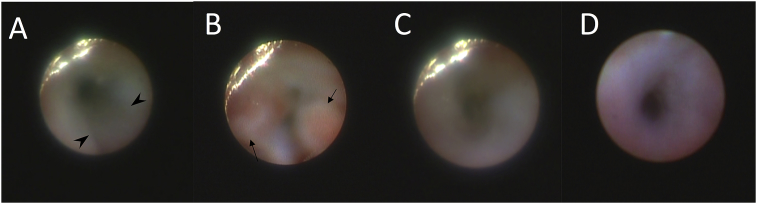

Fig. 2.

A series of photographs of the nasolacrimal duct obtained by lacrimal micro-endoscopy. The lacrimal tube (arrowhead) had been placed properly in the duct (A). Although granulated tissue (arrow) was observed on the nasolacrimal mucosa at the time of tube removal (B), follow-up observations at 1-month postoperative showed regression of the granulation tissue (C) and at 6-months postoperative showed that the treatment achieved recovery of healthy mucosa without re-obstruction (D).

2.1. Deformation of the removed silicone tube

Post removal of the silicone tube, a detailed evaluation revealed accumulation of pus inside of the lumen, however, the tube itself was undamaged and clear (Fig. 3). The length of the tube was 1mm longer than the standard length of an unused tube at one end (Table 1). However, the diameter of the removed tube was found to be the same as that of an unused tube. Degradation of the tube was measured via tension testing using a table-top tensile testing instrument (EZ Test; Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). The test findings showed that the tube was slightly stiffer than a new unused tube, yet only at the body and not at the rod (Fig. 4, Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

Detailed photographs of the removed lacrimal tube. Although accumulation of pus was seen in the inner cavity of the tube, the tube itself was clear.

Table 1.

Comparison of the dimensions between the silicone tube used in the current case and an unused tube.

| Total length (mm) | Body length (mm) (blue tip end/white tip end) | Body diameter (mm) | Rod length (mm) | Rod diameter (mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Used | 106 | 41/40 | 1.0 | 25 | 0.6 |

| Unused | 105 | 40/40 | 1.0 | 25 | 0.6~0.7 |

Fig. 4.

The results of a tension test on the body of the Nunchaku-style silicone tube is shown. The body of the used tube was found to be stiffer than that of the unused tube.

Fig. 5.

The results of a tension test on the rod of a Nunchaku-style silicone tube is shown. Te rod of the used tube was found to be not stiffer compared to the unused tube.

3. Discussion

The findings in the current case suggest the possibility that lacrimal tubes can remain implanted for decades in the nasolacrimal system with a successful outcome. The NST itself was found to be effective and in good condition, thus well-tolerating prolonged intubation.

It should be noted that there are few previous reports regarding the time period in which a lacrimal tube should be removed post intubation. To the best of our knowledge, the longest reported elapsed time post silicone nasolacrimal intubation until tube removal using a conventional Crawford-style stent was 3.5 years.7 The NST is designed as a push-to-insert lacrimal stent using a stainless inner probe to prevent false passage, with a silicone tube of 1.0mm outer diameter in the body part and 0.6mm diameter in the rod. This design enables ‘self-retaining’ in the lacrimal passage without anchoring to the nasal wall. Previous reports of lacrimal intubation using an NST had a typical timing of removal that ranged from 1- to 3-months postoperative.3,8,9,12 To achieve a successful outcome, the tube should be placed in the patient's lacrimal duct until the damaged mucosa has become re-epithelialized, however, postoperative complications and stent degradation are common concerns. Thus, the findings in this present study may encourage physicians to consider prolonged intubations for select cases of nasolacrimal duct obstructions before considering further additional invasive surgery, such as DCR, in order to achieve a successful outcome, or for cases of functional epiphora in which symptoms are likely to recur post tube removal.13,14

It should also be noted that there are few previous reports regarding the effects and outcomes of delayed tube removal after DCR. It is commonly theorized that following late removal of the tube there may be a higher incidence of inflammatory reactions, however, some studies have reported that the tube can be remain implanted for up to 5-years postoperative.15,16 In DCR cases, the implanted silicone tube does not affect the nasolacrimal duct, which is the most common area that becomes obstructed. Hence, the cases in the previous reports which support prolonged silicone intubation might, due to their nature, have less complication than intubations performed for cases of upper lacrimal system obstruction.

However, prolonged intubation might increase the risk of complications, and previous studies have reported that the formation of granulated tissue on the puncta is the most common complication upon detailed clinical examination.15, 16, 17, 18, 19 A previous study reported that lacrimal micro-endoscopy revealed that granulated tissue formation can occur not only on the puncta, but also along the entire lacrimal system, which can be caused by infection and/or mechanical stress.17 In our current case, the granulated tissue might have been caused by inflammatory reaction due to both factors, as it disappeared rapidly after the settlement of dacryocystitis and tube removal. The findings in previous reports, as well as the findings in our current case, suggest that tissue granulation is reversible with proper treatment. However, in cases of prolonged intubation, the patient should be followed and observed carefully by micro-endoscopy examination.

Punctal slitting might be another punctal-related complication after prolonged intubation.19 In our present case, minimal damage to the puncta was observed. We theorize that this might have been due to the design of the NST, as there was no need to suture the tube to the nasal wall and the rods did not stiffen over time despite being intubated in situ for 20 years.

Infection is the most serious complication associated with prolonged intubation, which resulted in our patient seeking medical care after decades of prolonged nasolacrimal intubation. Since infection might cause further mucosal damage resulting in recurrent obstruction, immediate treatment using irrigation and antibiotics is required. However, early tube removal in the middle of an ongoing inflammation might actually exacerbate the condition by causing more inflammation and obstruction, Thus, the tube should be left in place until the inflammation is fully successfully treated. In our current case, although the granulated tissue formation was complicated, we were able to achieve a successful outcome by ascertaining the correct removal time using micro-endoscopy.

Silicone is a well-tolerated material in situ and has adopted for use in various implant devices, however, a ‘foreign body’ reaction is inevitable. Silicone implants as represented by cranial, orthopedics, or aesthetic reconstruction surgery tend to be left in situ for decades without complication due to the fact that the implant is placed in a sterile condition.20, 21, 22 In contrast, a lacrimal, trachea, ureteral, or gastrostomy tube is exposed to the outside of the body. Hence, a prolonged placement may cause complications easier, such as migration, occlusion, dislodging, and infection, all of which usually require replacement or removal of the tube within 1-year postoperative.23, 24, 25 Compared to other types of exposed tubes, a lacrimal tube is completely isolated from the natural sterilization of the inner body, which might explain why the tube in the current case was tolerated for 2 decades. Silicone material, itself, has proved to be advantageous under harsh conditions, such as exposure to hydrochloric acid or irradiation, and biological inertness has been reported in the lacrimal duct using an animal model.26,27 In addition, the findings in this present study confirmed its mechanical advantage for lacrimal duct reconstruction.

4. Conclusions

Our findings reveal that lacrimal intubation can be left in situ for prolonged periods of time to allow for re-epithelization of the lacrimal mucosa in cases with high re-obstruction risks, or to relief symptoms in cases of functional epiphora. To achieve successful results with prolonged intubation, confirmation of proper intubation and careful observation by micro-endoscopy is necessary. Although the findings in this case study may encourage physicians to consider prolonged intubation, further study involving a larger number of cases is necessary.

Patient consent

Consent to publish the case report was not obtained. This report does not contain any personal information that could lead to the identification of the patient.

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Funding

No funding or grant support for this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no financial disclosures related to this study.

Authorship

All authors attest that they meet the current ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Kaneka Corporation for technical support, and John Bush for editing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Gibbs D.C. New probe for the intubation of lacrimal canaliculi with silicone rubber tubing. Br J Ophthalmol. 1967;51(3):198. doi: 10.1136/bjo.51.3.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pashby R.C., Rathbun J.E. Silicone tube intubation of the lacrimal drainage system. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979;97(7):1318–1322. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1979.01020020060014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mimura M., Ueki M., Oku H., Sato B., Ikeda T. Indications for and effects of Nunchaku-style silicone tube intubation for primary acquired lacrimal drainage obstruction. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2015;59(4):266–272. doi: 10.1007/s10384-015-0381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demirci H., Elner V.M. Double Silicone tube intubation for the management of partial lacrimal system obstruction. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(2):383–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connell P.P., Fulcher T.P., Chacko E., O’ Connor M.J., Moriarty P. Long term follow up of nasolacrimal intubation in adults. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(4):435–436. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.084590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fulcher T., O'Connor M., Moriarty P. Nasolacrimal intubation in adults. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82(9):1039–1041. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.9.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Psilas K., Eftaxias V., Kastanioudakis J., Kalogeropoulos C. Silicone intubation as an alternative to dacryocystorhinostomy for nasolacrimal drainage obstruction in adults. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1993;3(2):71–76. doi: 10.1177/112067219300300204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kabata Y., Goto S., Takahashi G., Tsuneoka H. Vision-related quality of life in patients undergoing silicone tube intubation for lacrimal passage obstructions. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(1):147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inatani M., Yamauchi T., Fukuchi M., Denno S., Miki M. Direct silicone intubation using Nunchaku-style tube (NST-DSI) to treat lacrimal passage obstruction. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000;78(6):689–693. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2000.078006689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couch S.M., White W.L. Endoscopically assisted balloon dacryoplasty treatment of incomplete nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(3):585–589. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu D., Bosley T.M. Silicone nasolacrimal intubation with mitomycin-C: a prospective, randomized, double-masked study. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(2):306–310. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01751-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sasaki T., Nagata Y., Sugiyama K. Nasolacrimal duct obstruction classified by dacryoendoscopy and treated with inferior meatal dacryorhinotomy: Part II. Inferior meatal dacryorhinotomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(6):1070–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moscato E.E., Dolmetsch A.M., Silkiss R.Z., Seiff S.R. Silicone intubation for the treatment of epiphora in adults with presumed functional nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28(1):35–39. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e318230b110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong N.X., Zhao Y.Y., Jin X.M. Use of the Crawford tube for symptomatic epiphora without nasolacrimal obstruction. Int J Ophthalmol. 2016;9(2):282–285. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2016.02.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charalampidou S., Fulcher T. Does the timing of silicone tube removal following external dacryocystorhinostomy affect patients' symptoms? Orbit. 2009;28(2-3):115–119. doi: 10.1080/01676830802674342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hausler R., Caversaccio M. Microsurgical endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy with long-term insertion of bicanalicular silicone tubes. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:188–191. doi: 10.1001/archotol.124.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mimura M., Ueki M., Oku H., Sato B., Ikeda T. Evaluation of granulation tissue formation in lacrimal duct post silicone intubation and its successful management by injection of prednisolone acetate ointment into the lacrimal duct. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2016;60(4):280–285. doi: 10.1007/s10384-016-0446-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim B.M., Osmanovic S.S., Edward D.P. Pyogenic granulomas after silicone punctal plugs: a clinical and histopathologic study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139(4):678–684. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson R.L., Edwards J.J. Indications, complications and results with silicone stents. Ophthalmology. 1979;86(8):1474–1487. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(79)35374-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ström J.O., Boström S., Bobinski L., Theodorsson A. Low-grade infection complicating silastic dural substitute 32 years post-operatively. Brain Inj. 2011;25(2):250–254. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2010.542431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Motta F., Antonello C.E. Comparison between an Ascenda and a silicone catheter in intrathecal baclofen therapy in pediatric patients: analysis of complications. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2016;18(4):493–498. doi: 10.3171/2016.4.PEDS15646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu H.C., Fang H.W., Chiu Y.H. Delayed-onset edematous foreign body granulomas 40 years after augmentation rhinoplasty by silicone implant combined with liquid silicone injection. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41(3):637–640. doi: 10.1007/s00266-017-0790-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah J., Sunkara T., Yarlagadda K.S., Rawla P., Gaduputi V. Gastric outlet and duodenal obstruction as a complication of migrated gastrostomy tube: report of two cases and literature review. Gastroenterol Res. 2018;11(1):71–74. doi: 10.14740/gr954w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawrence E.L., Turner I.G. Materials for urinary catheters: a review of their history and development in the UK. Med Eng Phys. 2005;27:443–453. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White A.C. Long-Term mechanical ventilation: management strategies. Respir Care. 2012;57(6):889–899. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Branicki F.J., Ogilvie A.L., Willis M.R., Atkinson M. Structural deterioration of prosthetic oesophageal tubes: an in vitro comparison of latex rubber and silicone rubber tubes. Br J Surg. 1981;68(12):861–864. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800681210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snead J.W., Rathbun J.E., Crawford J.B. Effects of the silicone tube on the canaliculus: an animal experiment. Ophthalmology. 1980;87(10):1031–1036. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(80)35129-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]