Abstract

The Flavivirus genus comprises a diverse group of viruses that utilize a wide range of vertebrate hosts and arthropod vectors. The genus includes viruses that are transmitted solely by mosquitoes or vertebrate hosts as well as viruses that alternate transmission between mosquitoes or ticks and vertebrates. Nevertheless, the viral genetic determinants that dictate these unique flaviviral host and vector specificities have been poorly characterized. In this report, a cDNA clone of a flavivirus that is transmitted between ticks and vertebrates (Powassan lineage II, deer tick virus [DTV]) was generated and chimeric viruses between the mosquito/vertebrate flavivirus, West Nile virus (WNV), were constructed. These chimeric viruses expressed the prM and E genes of either WNV or DTV in the heterologous nonstructural (NS) backbone. Recombinant chimeric viruses rescued from cDNAs were characterized for their capacity to grow in vertebrate and arthropod (mosquito and tick) cells as well as for in vivo vector competence in mosquitoes and ticks. Results demonstrated that the NS elements were insufficient to impart the complete mosquito or tick growth phenotypes of parental viruses; however, these NS genetic elements did contribute to a 100- and 100,000-fold increase in viral growth in vitro in tick and mosquito cells, respectively. Mosquito competence was observed only with parental WNV, while infection and transmission potential by ticks were observed with both DTV and WNV-prME/DTV chimeric viruses. These data indicate that NS genetic elements play a significant, but not exclusive, role for vector usage of mosquito- and tick-borne flaviviruses.

Keywords: : tick-borne flavivirus, mosquito-borne flavivirus, deer tick virus, Powassan virus, West Nile virus, vector competence

Introduction

The family Flaviviridae, genus Flavivirus, comprises enveloped viruses with positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genomes of ∼11 kb. Three structural proteins, envelope (E), membrane (M), and capsid (C), and seven nonstructural (NS) proteins, NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3 (protease and helicase), NS4A, NS4B, and NS5 (methyltransferase and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase), are encoded from a single polyprotein that is co- and post-translationally cleaved by host and viral proteases into the respective viral proteins. The envelope protein acts as the primary surface antigen and mediates fusion between the virion and cellular receptors. The membrane protein is the product of proteolytic processing of the prM fragment and is essential for virus particle maturation (Lindenbach and Rice 2001). The capsid protein forms the nucleocapsid, which comprises viral genomic RNA coupled with capsid protein fragments. The entire viral genome is translated as a single polyprotein (the N terminal encodes three structural genes, and the C terminal encodes seven NS proteins) (Lindenbach et al. 2006). The open reading frame is flanked by conserved 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) that serve as cis-acting elements critical for viral replication (Lindenbach and Rice 2001).

Flaviviruses are responsible for an estimated 100 million human infections per year (Petersen and Marfin 2005). While the majority of flaviviruses are maintained in arthropod vector–vertebrate host transmission cycles, some flaviviruses have adapted to a single-host life cycle in either an arthropod or a vertebrate host. To date, flaviviruses have been separated into five groups based on host/vector-specific associations, including insect-specific flaviviruses (ISFVs), tick-borne flaviviruses (TBFVs), no known vector viruses (NKVs), mosquito-borne flaviviruses (MBFVs), and a recently described unidentified vertebrate host (UVH) group of flaviviruses (Kuno et al. 1998, Gould et al. 2003). The UVH group is unique as it phylogenetically falls within the MBFV clade, yet viruses in this clade have not demonstrated a capacity for replication in vertebrate cells (Huhtamo et al. 2009, Junglen et al. 2009, Evangelista et al. 2013, Kolodziejek et al. 2013, Lee et al. 2013, Kenney et al. 2014).

Multiple studies have been performed to characterize chimeric flaviviruses, some of which have identified specific viral genetic determinants dictating differential vector competence between viruses. For instance, chimerization between an NKV strain, Modoc virus (MODV), prME regions, and a yellow fever virus (YFV) genetic backbone has indicated that the inability of NKV viruses to infect and replicate in mosquito cells in vitro is not exclusively controlled by prME genetic elements (Charlier et al. 2010). Studies with other chimeric viruses consisting of donor prME regions from TBFVs and backbones from MBFVs support this assertion as all recombinant viruses demonstrated the ability to infect and replicate in mosquito cells, although (in some cases) in a reduced capacity (Pletnev et al. 1992, Engel et al. 2011, Wang et al. 2014). Utilizing a tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) replicon and a Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) prME helper system, Yoshii et al. (2008) were able to identify that JEV prME proteins allowed for internalization of virus-like particles in C6/36 mosquito cells, but that no replication was observed (Yoshii et al. 2008).

However, majority of studies lacked the direct comparison between reciprocal chimeric viruses to fully assess the heterotypic infection of structural versus NS components. Reciprocal chimeric viruses generated between more closely related viruses, West Nile virus (WNV) and St. Louis encephalitis viruses (SLEV), demonstrated an increased oral infectivity of Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes for the chimeric virus with NS genetic elements of SLEV (Maharaj et al. 2012). However, other in vivo studies examining chimeric viruses between distantly related flaviviruses with more divergent vector usage patterns have indicated that NS regions alone are not sufficient to allow for infection and/or replication in mosquitoes (Pletnev et al. 1992, Engel et al. 2011). This suggests that either additional structural determinants are involved in mosquito vector competence or that chimerization could have an inherent effect on vector infectivity.

In contrast to experiments designed to identify flaviviral mosquito competence determinants, very few experiments have been reported assessing the genetic basis for competence of flaviviruses in ticks, either in vitro or in vivo. Infection of Ixodes scapularis, ISE6, cells with a TBEV prME/DENV4 chimeric virus indicated that TBEV prME regions alone were not sufficient for in vitro infection. Similarly, I. scapularis larvae immersed in suspensions of chimeric TBEV prME/DENV4 viruses failed to become infected, suggesting that prME regions alone are similarly not sufficient for in vivo tick infection (Engel et al. 2011). This is the only study that has examined full-length chimeric flaviviral infection of tick cells with TBFV prME genes, and to our knowledge, there are no published accounts examining whether a TBFV backbone can sufficiently confer in vitro or in vivo growth in tick cells. As such, the studies described herein were undertaken to elucidate the in vitro and in vivo viral genetic determinants for either mosquito or tick competence of TBFVs (lineage II Powassan virus) and MBFVs (WNV).

Phylogenetic examination of flaviviruses proposes that both TBFVs and MBFVs originated in the old world (OW) and likely diverged ∼40,000 years ago. Similarly, while WNV was introduced into the western hemisphere in 1999, Powassan virus (POWV) has been estimated as having crossed the Bering land bridge into North America between 15,000 and 11,000 years ago (Pettersson and Fiz-Palacios 2014). Powassan virus was initially isolated from a human brain in Powassan, Canada, in 1958 (Mc and Donohue 1959). A phylogenetically and ecologically distinct, yet serologically indistinguishable, strain, deer tick virus (DTV), was isolated from I. scapularis, a recognized vector of a multitude of pathogens and frequent feeding on humans. Recently, strains of POWV have caused an unprecedented number of cases and mortality in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Maine, and Connecticut and are considered an emerging public health threat (Piantadosi et al. 2016, Cavanaugh et al. 2017, Hermance and Thangamani 2017, Tutolo et al. 2017).

While WNV has been isolated repeatedly from a multitude of both argasid and ixodid ticks (Lawrie et al. 2004, Mumcuoglu et al. 2005, Formosinho and Santos-Silva 2006, Moskvitina et al. 2008, Lwande et al. 2013, 2014), laboratory studies have yet to demonstrate ixodid ticks as competent vectors (Anderson et al. 2003, Lawrie et al. 2004, Reisen et al. 2007). However, transmission by soft ticks, which are commonly associated with avian hosts, has been demonstrated (Abbassy et al. 1993, Lawrie et al. 2004, Kokonova et al. 2013). Alternatively, DTV has never been isolated from mosquitoes and only serologically detected in avian species (Dupuis et al. 2013).

This is likely explained by pronounced differences in ecology as WNV typically cycles between Culex mosquitoes and avians, while DTV persists in a cycle between I. scapularis and rodents. However, various types of ticks are found to be associated with birds and would likely be exposed to high WNV viremia of any infected bird (>6.0 log10 plaque-forming units [PFU]/mL), thus highlighting the importance of understanding determinants of tick vector competence for WNV (Anderson and Magnarelli 1984). Similarly, while the primary vectors of WNV have a predilection for avian bloodmeals, it is possible that mosquito species with a different host preference could encounter a DTV viremic rodent or small mammal host and acquire the virus.

Herein, methods for generation of a novel infectious clone for the DTV Spooner strain necessary to conduct vector specificity studies are described. Reciprocal chimeric viruses were generated and assessed for relative in vitro growth capacity and in vivo infection of mosquito and tick models to test the hypothesis that NS genetic elements are the critical determinants defining flaviviral vector associations.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Vero (African green monkey kidney fibroblast) cells and BHK-21 (baby hamster kidney fibroblast) cells were cultured as described previously (Goodman et al. 2014). Briefly, cells were maintained at 37°C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) with 8% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlas Biologicals, Fort Collins, CO), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Life Technologies), 27 mM sodium bicarbonate (Life Technologies), 0.1 mM gentamicin (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), and 1 μM amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Aedes albopictus mosquito C6/36 cells were maintained at 28°C in DMEM (Life Technologies) with 10% FBS (Atlas Biologicals), 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (Life Technologies), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Life Technologies), 9 mM sodium bicarbonate (Life Technologies), and 0.1 mM gentamicin (Lonza). ISE6 tick cells, derived from I. scapularis embryonated eggs, were obtained from Ulrike Munderloh (University of Minnesota) and maintained at 32°C, as previously described (Munderloh et al. 1994).

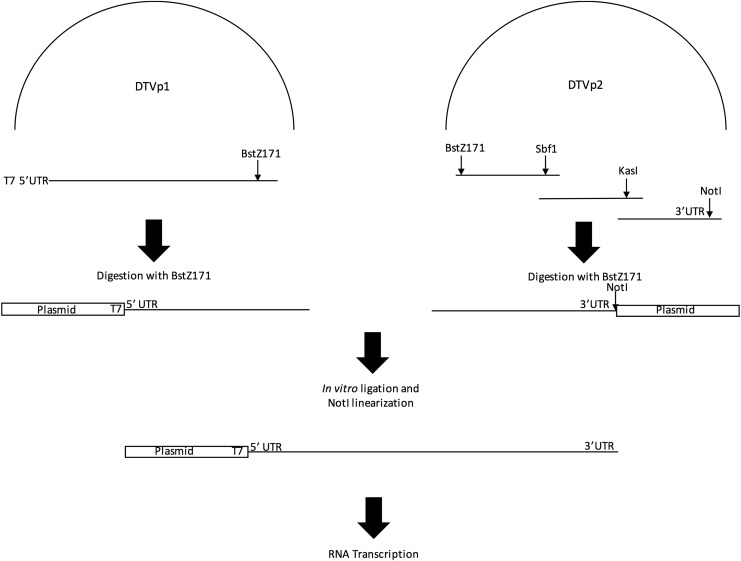

Construction of DTV Spooner strain cDNA clone

Before generating the DTV cDNA infectious clone, the initial 26 nt of the 5′ UTR and terminal 26 nt of the 3′ UTR of the Spooner DTV strain were determined by direct sequencing using 5′- and 3′-RACE Systems (Life Technologies), respectively. The viral genome was divided into four overlapping fragments spanning appropriate unique restriction sites (Fig. 1). Viral cDNAs were synthesized from RNA by using reverse transcriptase (SuperScript II; Life Technologies). RT-PCR fragments were amplified by using high-fidelity Pfu Ultra Hotstart polymerase (Agilent, La Jolla, CA). The following conditions were used for PCR: 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, primer annealing for 30 s at temperatures from 58°C to 63°C, followed by extension at 72°C for 1 min per 1-kb amplification. RT-PCR fragments of predicted size were cloned into the pCR-XL-TOPO vector (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. To clone viral cDNA into the final construction, a customized, low-copy number kanamycin-resistant vector with convenient unique restriction sites was generated. The first fragment (T7 promoter–3612 nt–BstZ17I) was cloned into this vector and denoted as DTVp1. For the second plasmid, naturally occurring restriction sites BstZ17I, SbfI, and KasI and an introduced restriction site following the final nucleotide of the viral 3′UTR, NotI, were utilized to generate the 7228-bp amplicon for remainder of the genome. The three overlapping amplicons were sequentially cloned into the pCR-XL-TOPO vector (Life Technologies). The second cDNA, denoted as DTVp2, was sequenced in its entirety and used as an in vitro ligation template in conjunction with DTVp1 following restriction endonuclease digestion, as described below (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Construction of the DTV Spooner strain infectious clone and viral rescue. A T7 promoter was added to a 3597-bp amplicon terminating at a BstZ17I, which was subsequently cloned into a low-copy number plasmid with kanamycin resistance and designated DTVp1. DTVp2 was generated by cloning overlapping fragments (7228 bp) with naturally occurring restriction sites BstZ17I, SbfI, and KasI. NotI was introduced as a ligation site following the 3′ UTR. Both DTVp1 and DTVp2 were digested with BstZ171 before in vitro ligation and linearization with NotI. The resulting linear DNA was transcribed to RNA for subsequent electroporation. DTV, deer tick virus.

Rescue of viruses from WNV and DTV cDNA clones

The two-plasmid NY99 WNV infectious clone (WNp1 and WNp2) was derived from a strain isolated from a flamingo in 1999, digested, in vitro ligated, and subjected to in vitro transcription before electroporation, as previously described (Beasley et al. 2005, Kinney et al. 2006, Maharaj et al. 2012). Briefly, 10 μg of WNp1 was digested with AscI, PCR purified, and eluted before secondary digestion with NgoMIV. A total of 20 μg of WNp2 was digested with MluI, purified, and eluted before complete digestion with NgoMIV. The digested product from WNp1 and WNp2 was PCR purified and eluted. Purified WNp1 and WNp2 were in vitro ligated at a ratio of 1:3 and subsequently linearized with XbaI. For the two-plasmid DTV clone, 10 μg of the 5′ plasmid (DTVp1) and 20 μg of the 3′ plasmid (DTVp2) were each initially digested with BstZ17I. Following PCR purification, DTVp1 and DTVp2 were in vitro ligated at a 1:3 ratio and subsequently linearized by NotI.

For generation of chimeras, enzymes utilized to generate fragments for in vitro ligation and subsequent linearization were determined by the included backbone. For NY99 WNV, DTV, and DTV-prME/WNV infectious clones, the linearized product was then utilized as a template for in vitro transcription of positive-sense viral RNA from a T7 RNA polymerase promoter with an analog A cap m7G(5′)ppp(5′)A (New England Biolabs) as described for WNV cDNA. Preparation and transcription of the DTV-prME/WNV construct were performed in the same manner as the parental WN99 infectious clone, as previously described (Nofchissey et al. 2013). Briefly, prME regions of DTV were cloned into the WNp1 plasmid generating the DTVprME/WNVp1 clone, which was used in conjunction with the WNp2 clone to generate the full-length virus.

For all viruses, transcribed RNA derived from each construct was electroporated into ∼107 baby hamster kidney cells (BHK) using two pulses at 800 V, R = 25, C = 25 uF on a BTX ECM 830 (Harvard Apparatus). Supernatants were harvested when 60–70% of cells showed cytopathic effect (CPE), clarified by centrifugation at 6000 × g, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C in media with 20% FBS. At the time of harvest, 140 μL of each virus was subjected to RNA extraction and subsequent genome sequencing. RNA was extracted using QIAamp Viral RNA Mini kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and amplified using the Titan One-Tube RT-PCR kit (Roche, Germany). RT-PCR products were visualized on a 1% agarose gel and bands were gel extracted. Sequencing was performed using an ABI 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) and alignments and analysis were performed in Geneious 8 (www.geneious.com) (Kearse et al. 2012). In addition to confirming the coding sequence identity between the DTV Spooner strain and our rescued clone, we compared the phenotypes of these two viruses in C6/36 and ISE6 cells and found them to behave similarly (data not shown).

Generation of WNV-prME/DTV chimeric virus

Due to bacterial toxicity, generation of a stable 5′ plasmid of the WN-prME fragment in the DTV backbone was not achieved despite efforts to introduce alternative in vitro ligation points to stabilize the plasmid. Alternatively, a high-fidelity Phusion enzyme (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) was utilized to amplify the fragment from previous cloning intermediary fragments comprising three overlapping amplicon fragments (5′ end of DTV clone to prME, complete WNV prME, and the remainder of the DTV-1 5′ plasmid). These three amplicons, encompassing the entire 5′ plasmid region, were generated and combined into a single fragment utilizing fusion PCR, as described previously (Charlier et al. 2003). The fusion fragment was then digested and used directly as an in vitro ligation product with the digested DTV-2 plasmid. RNA was subsequently transcribed and electroporated into BHK cells, as described above. The supernatant from the original electroporation was passaged an additional time to acquire a high titer stock, and the resulting virus was sequenced.

Virus infection in cell culture

Growth kinetics of each of the parental strains and the two chimeric viruses were compared on Vero, BHK, C6/36 mosquito, and ISE6 tick cells. Monolayers of each cell type were inoculated in triplicate at multiplicities of infection (MOIs) of 0.1 and 5 and allowed to adsorb for 1 h. Following incubation, cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and overlaid with fresh cell line-appropriate media as described above. The total volume of supernatant (1 mL) was collected from each well and replaced with the same volume of fresh media at predetermined time points. Samples were frozen at −80°C until viral titers were measured by plaque assay on Vero cells. Two-way ANOVA tests with a post hoc multiple comparisons test with Bonferroni corrections were performed using Prism software to identify differences in mean daily growth, version 6. p Values ≤0.05 were considered significant.

Assessment of mosquito oral infectivity

Four cohorts of colonized adult female Culex pipiens pipiens (Chicago) mosquitoes maintained at the Division of Vector-Borne Diseases since 2010 (Kothera et al. 2010) were transferred to a BSL-3 environmental chamber and maintained at 28°C with 75% relative humidity. At ∼3–5 days postemergence, each group was offered an infectious bloodmeal (DTV, WNV, DTV-prME/WNV, or WNV-prME/DTV) with a titer of 1.0 × 107 PFU/mL at a 1:1 v:v ratio with defibrinated sheep blood (Colorado Serum Company, Boulder, CO). Artificial bloodmeals were encased in a collagen membrane and warmed in a Hemotek feeder (Discovery Workshops, Accrington, United Kingdom) before being placed on the screened lids of 0.45-L paper cartons. After feeding, mosquitoes were cold-anesthetized, sorted, and held at 28°C at a relative humidity of 70–75% for an extrinsic incubation period of 11–14 days. After the extrinsic incubation period, legs and wings were removed from cold-anesthetized mosquitoes and placed in a centrifuge (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) tube with 350 μL of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's essential medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS and amphotericin B (50 μg/mL). The proboscis of each immobilized mosquito was inserted into a 10-μL capillary tube containing Type B immersion oil (Cargille Laboratories, Cedar Grove, NJ) to induce salivation for ∼45 min. After salivation, mosquito bodies and legs were triturated for 4 min at a frequency of 24 cycles per second in 350 μL of DMEM, 10% FBS, and amphotericin B using a Mixer Mill 300 (Retsch, Newton, PA). Expectorants were added to a tube containing 100 μL of 10% FBS/DMEM and centrifuged at 5000 × g for 2 min before transfer of supernatants to fresh tubes. Collected supernatants from each sample were analyzed for the presence of virus by induction of CPEs on Vero cells.

Synchronous infection of I. scapularis ticks

Three days before synchronous infection, uninfected I. scapularis adult ticks were transferred to a 26°C environmental chamber for dehydration and desiccation. Infection was performed by a modification of an immersion feeding method previously described (Policastro and Schwan 2003). After 3 days of desiccation, ticks were divided into four groups and suspended in 1 mL of each of the four virus stocks. Each vial of virus containing submerged ticks was incubated at 34°C for 45 min. The ticks were washed twice with PBS and dried of excess moisture using filter paper. The virus-exposed ticks were transferred to glass vials where they were stored inside a desiccator at 26°C to allow extrinsic incubation of respective viruses.

Tick salivary gland dissection and RNA extraction

After 4 weeks of incubation at 26°C, salivary glands from each tick were dissected and stored in TRIzol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The midgut and Malpighian tubules were also harvested from each tick and labeled as other organs; abbreviated [OTH]. The dissected organs were homogenized in TRIzol and viral RNA extraction was performed by a combination of TRIzol reagent and QIAamp Viral RNA mini (Qiagen) protocols (Hermance and Thangamani 2015 Heinze et al. 2012).

Viral load determination from tick samples by quantitative RT-PCR

All tick salivary glands and OTH organs were screened by real-time RT-PCR. The iTaq Universal Probes One-Step assay (Bio-Rad) was performed on an iCycler iQ5 real-time PCR instrument (Bio-Rad). The master mix and reverse transcriptase from the iTaq Universal Probes One-Step assay were mixed with template RNA and primer–probe pairs. Probes contained a 5′-reporter FAM and a 3′-quencher TAMRA. The following primer and probe set was used for detection of the NS5 region of the DTV genome: 5′-GATCATGAGAGCGGTGAGTGACT-3′ (+); 5′-GGATCTCACCTTTGCTATGAATTCA-3′ (−); Probe 5′-TGAGCACCTTCACAGCCGAGCCAG-3′. For detection of the conserved region of the 5′ UTR and part of the capsid gene of the WNV genome, the following primer and probe set was used: 5′-CCTGTGTGAGCTGACAAACTTAGT-3′ (+); 5′-GCGTTTTAGCATATTGACAGCC-3′ (−); Probe 5′-CTGGTTTCTTAGACATCGAGATCT-3′. Reactions were performed in IQ PCR 96-well plates (Bio-Rad) that were sealed and run on an iCycler iQ5 real-time PCR instrument (Bio-Rad) with the following cycling protocol: 10 min at 50°C; 3 min at 95°C; 15 s at 95°C, followed by 30 s at 60°C for 45 cycles; and an 81-cycle (+0.5°C/cycle) 55–95°C melt curve. RNA was extracted from BHK transfection stocks of known titer (PFU/μg of RNA) that were used to synchronously infect the ticks. Serial dilutions were made from the resulting RNA. For each virus stock, a linear equation was generated by plotting the cycle threshold (Ct) values of the standard curve against the corresponding log titer. Viral load Ct values from the unknown salivary gland and OTH samples were determined by real-time PCR and converted to log10 PFU equivalents using the linear equation determined for the standard curve. Results were analyzed utilizing Student's t-test examining differences in mean titers between surviving ticks.

Results

Characterization of rescued viruses

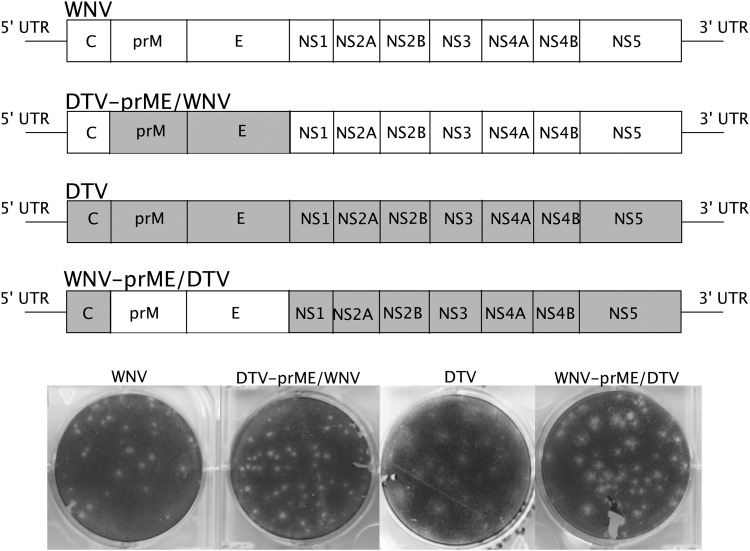

As previously described (Beasley et al. 2005, Kinney et al. 2006), clone-generated WNV showed ∼70% CPE 3 days postelectroporation (dpe) in BHKs and derived a stock of 8.8 log10 PFU/mL in Vero cells. Plaques were small and clear 4 days postinfection (dpi), following a 3-dpi overlay with neutral red (Fig. 2). Recombinant DTV derived from electroporated BHK cells showed initial signs of CPE at 4 dpe, was harvested 6 dpe, and found to have a titer of 7.0 log10 PFU/mL. On Vero cells, DTV plaques were large and poorly defined following a 7-dpi overlay on Vero cells (Fig. 2). The DTV-prME/WNV chimeric virus exhibited a similar pattern to the parental WNV and was harvested at a titer of 7.4 log10 PFU/mL 3 dpe. Plaque size and the day of overlay were the same as that for WNV (Fig. 2). Initial electroporation of WNV-prME/DTV RNA in BHK cells was blind passaged in Vero cells and CPE was observed 7 dpi and supernatant harvested 9 dpi. A titer of 7.5 log10 PFU/mL was detected in Vero cells and plaques appeared only slightly larger than those of WNV or those of the DTV-prME/WNV clone, although plaque margins were less defined (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Schematic illustration of the WNV, DTV-prME/WNV, DTV, and WNV-prME/DTV genomes and their corresponding plaque phenotypes. Clone-derived WNV was generated using in vitro ligation of WNVp1 and WNVp2 and subsequent linearization and in vitro transcription, whereas DTV-prME/WNV was generated from ligation, linearization, and in vitro transcription of DTV-prME/WNVp1 and WNVp2. DTV was generated as described with DTVp1 and DTVp2. WNV-prME/DTV was generated from ligation of a 3727-bp PCR amplicon (T7-DTVcapisd-WNVprME-DTVNS1-Bstz17I) with DTVp2 and subsequent in vitro transcription. WNV, West Nile virus.

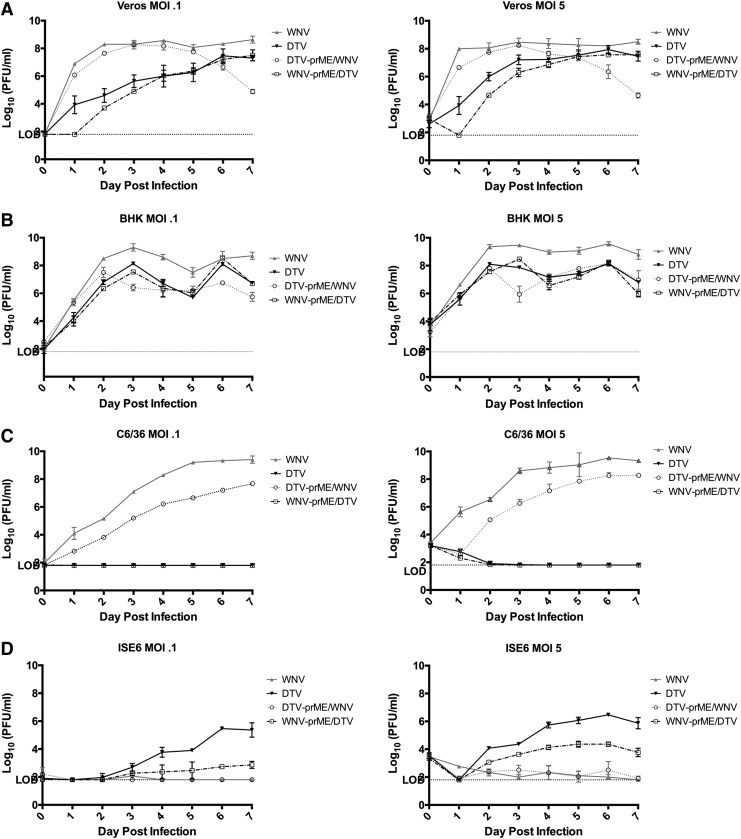

Vertebrate cell growth (Vero and BHK cells)

Both of the parental clone-derived viruses and the two chimeric viruses were capable of growth in Vero and BHK vertebrate cell lines with at least 7 log10 PFU/mL titers observed. In Vero cells, WNV demonstrated a 10-fold higher peak mean titer compared with DTV (8.5 and 7.5 log10 PFU/mL, respectively). Comparison of growth profiles of the WNV-prME/DTV chimeric virus and DTV only showed growth differences in Vero cells at early time points (dpi 1 and 2 for the lower MOI and dpi 1–3 for the higher MOI); however, mean peak titers were indistinguishable (7.5 log10 PFU/mL). Similarly, the DTV-prME/WNV chimeric virus and WNV demonstrated indistinguishable mean peak titers of 8.3 and 8.5 log10 PFU/mL. However, multiple comparison analysis showed the DTV-prME/WNV chimeric virus to have a significantly lower growth potential than WNV at dpi 5–7 (p < 0.05; p < 0.0001; p < 0.001), suggesting that inclusion of heterologous DTV structural regions could affect growth at later time points in Vero cells (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Growth comparison of the DTV and WNV infectious clone-derived parental and chimeric WNV-prME/DTV and DTV-prME/WNV viruses in various vertebrate and invertebrate cell lines. Inoculations were performed at MOIs of 0.1 and 5 on (A) Vero, (B) BHK, (C) C6/36, and (D) ISE6 cells. LOD was 1.8 log10 (PFU/mL). Titers were determined by plaque assay on Vero cells. BHK, baby hamster kidney cells; LOD, limit of detection; PFU, plaque-forming units; MOIs, multiplicities of infection.

In BHK cells, no significant growth differences were observed between viruses with DTV NS genetic elements. DTV and WNV-prME/DTV reached statistically indistinguishable mean peak titers of 8.2 and 8.4 log10 PFU/mL, respectively, whereas peak mean titers of WNV (9.5 log10 PFU/mL) and DTV-prME/WNV (8.2 log10 PFU/mL) were statistically different (p < 0.01). In comparison with WNV, the DTV-prME/WNV chimera reached significantly lower titers on dpi 2–7 (p < 0.0006; p < 0.0011; p < 0.0001; p < 0.0001; p < 0.0001) at an MOI of 0.1 and on dpi 1–7 (p < 0.0057; p < 0.0001; p < 0.0001; p < 0.0001; p < 0.0001; p < 0.0001; p < 0.0001) in the MOI 5 treatment group (Fig. 3B).

Mosquito cell growth (C6/36)

In mosquito cells, viruses with NS regions derived from DTV (DTV and WNV-prME/DTV) failed to grow at or above the minimal level of detection (1.8 log10 PFU/mL), whereas constructs with WNV NS regions (WNV and DTV-prME/WNV) grew to peak mean titers of 9.6 log10 PFU/mL versus 7.6 log10 PFU/mL, respectively (p < 0.0015). Despite sharing the same NS regions, DTV-prME/WNV grew to significantly lower titers compared with WNV at all days postinfection at both MOIs (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3C).

Tick cell growth (ISE6)

Growth profiles of WNV, DTV, and the two chimeric viruses exhibited considerable variability in ISE6 tick cells (Fig. 3D). At an MOI of 5, DTV reached a peak mean titer 10,000-fold higher than the WNV peak titer. There was no evidence of WNV or DTV-prME/WNV replication on ISE6 cells at either MOI. In general, DTV showed increased replication fitness compared with WNV-prME/DTV, which was more pronounced at the higher MOI. At MOI of 5, the parental DTV strain achieved a peak mean titer of 6.5 log10 PFU/mL, while the WNV-prME/DTV chimeric virus reached a lower peak mean titer of 4.410 PFU/mL (p < 0.01). Titer differences were observed by dpi 2 at MOI of 5 and at dpi 4 at an MOI of 0.1.

In vivo mosquito infection

Culex pipiens females were orally exposed to 6–6.5 log10 PFU/mL bloodmeal of the two parental and two prME chimeric viruses and were tested for infection (bodies), dissemination (wings), and transmission potential (saliva) by CPE assay on Vero cell monolayers and verified by quantitative RT-PCR. Of the 12 mosquitoes exposed to DTV that survived the 14-day extrinsic incubation period, none demonstrated infection or dissemination. Accordingly, transmission was not assessed for any of the saliva samples from these mosquitoes (Table 1). Similarly, none of the 24 surviving C. pipiens mosquitoes exposed to chimeric WNV-prME/DTV showed evidence of infection or subsequent dissemination (Table 1). As expected, the WNV parental virus was found to have infected 50% (6/12) of orally exposed females and, of those, 83% (5/6) and 67% (4/6) demonstrated successful dissemination and transmission, respectively (Table 1). In contrast, 0 of the 20 surviving DTV-prME/WNV chimeric virus-exposed mosquitoes demonstrated infection, dissemination, or transmission potential (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of Oral Exposure of Culex pipiens Mosquitoes

| Virus | N | Inoculum stock (PFU/mL) log10 | Infection (%) | Dissemination infection (%)a | Transmission (%)b,c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTV | 12 | 6 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| WNV-prME/DTV | 24 | 6.4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| WNV | 12 | 6.3 | 6 (50) | 5 (83) | 4 (67) |

| DTV-prME/WNV | 20 | 6.5 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

No. of disseminated/no. of infected.

Transmission determined by salivation.

No. of positive transmissions/no. of infected.

DTV, deer tick virus; PFU, plaque-forming units; WNV, West Nile virus.

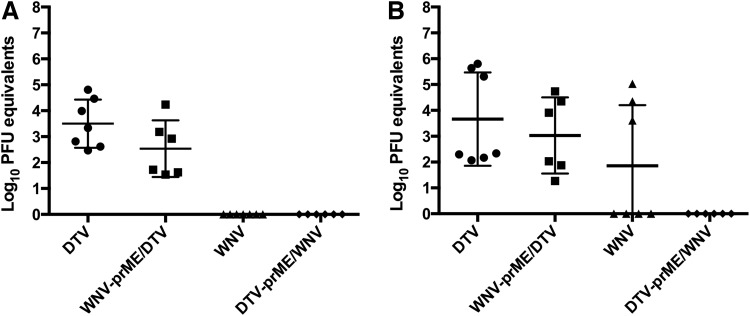

In vivo tick infection

Following immersion of adult I. scapularis with the two parental and two chimeric viruses, organs were dissected out of the ticks and viral loads were quantified by quantitative RT-PCR to estimate viral titers. Three to five females and one to four males per virus group survived submersion and incubation and were tested for viral RNA. Data by sex were combined for analysis. Both DTV and WNVprME/DTV were detected in tick salivary glands with peak titers of 4.8 log10 PFU/μg of RNA [ = 3.5 log10 (PFU/μg of RNA)] and 4.2 log10 PFU/μg of RNA [

= 3.5 log10 (PFU/μg of RNA)] and 4.2 log10 PFU/μg of RNA [ = 3.0 log10 (PFU/μg of RNA)], respectively (Fig. 4A). Alternatively, neither WNV nor the DTVprME/WNV chimera was detected in salivary glands of exposed ticks. Interestingly, RNA from DTV, WNVprME/DTV, and WNV was detected in other organs tested, while the DTVprME/WNV chimera was not. Specifically, DTV, WNVprME/DTV, and WNV reached a peak titer of 5.8 log10 PFU/μg of RNA [

= 3.0 log10 (PFU/μg of RNA)], respectively (Fig. 4A). Alternatively, neither WNV nor the DTVprME/WNV chimera was detected in salivary glands of exposed ticks. Interestingly, RNA from DTV, WNVprME/DTV, and WNV was detected in other organs tested, while the DTVprME/WNV chimera was not. Specifically, DTV, WNVprME/DTV, and WNV reached a peak titer of 5.8 log10 PFU/μg of RNA [ = 3.7 log10 (PFU/μg of RNA)], 4.7 log10 PFU/μg of RNA [

= 3.7 log10 (PFU/μg of RNA)], 4.7 log10 PFU/μg of RNA [ = 3.0 log10 (PFU/μg of RNA)], and 5.0 log10 PFU/μg of RNA [

= 3.0 log10 (PFU/μg of RNA)], and 5.0 log10 PFU/μg of RNA [ = 2.3 log10 (PFU/μg of RNA)], respectively (Fig. 4B). Further analysis of infection observed in other organs of the WNV exposure group demonstrated that WNV RNA was only detected in males and not in females. This was the only difference observed between males and females during the tick challenge experiments. A Student's t-test examining the difference in mean titers between surviving ticks following exposure to DTV and WNV-prME/DTV showed no difference regardless of the organ tested.

= 2.3 log10 (PFU/μg of RNA)], respectively (Fig. 4B). Further analysis of infection observed in other organs of the WNV exposure group demonstrated that WNV RNA was only detected in males and not in females. This was the only difference observed between males and females during the tick challenge experiments. A Student's t-test examining the difference in mean titers between surviving ticks following exposure to DTV and WNV-prME/DTV showed no difference regardless of the organ tested.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of PFU equivalents determined by RNA loads derived from quantitative RT-PCR converted to titers based on a standard curve in (A) salivary glands and (B) other organs in between of Ixodes scapularis following immersion and synchronous infection.

Discussion

The genetic determinants for flavivirus adaptation to replication in mosquito or tick vectors form an area requiring additional investigation. Understanding genetic determinants and any adaptive constraints these factors impart on flaviviruses will enhance our ability to design attenuated, host-restricted, yet replication-competent, live-attenuated vaccine candidates. DTV and WNV were selected because of their distinct evolutionary history and ecological phenotypes. Chimeric viruses between DTV and WNV were generated to assess genetic determinants of infection and growth within in vitro and in vivo models for each virus's respective arthropod vectors. Based on limited previous studies, we hypothesized that NS regions largely determine replicative fitness for both MBFV and TBFV in their respective vectors. In support of this hypothesis, it was observed that matching NS proteins were essential for replication in each respective natural invertebrate model as viruses with a DTV backbone did not grow within in vitro or in vivo mosquito cells and chimeric viruses with a WNV NS backbone were unable to grow in ISE6 cells or infect I. scapularis. However, we did observe infection in other organs of three of four male ticks exposed to WNV. This implies that NS regions of the WNV genome are driving infection of nonsalivary organs in males as the only chimera unable to infect ticks was the chimera lacking WNV NS regions. There is an established precedent for WNV infection in ticks as previous laboratory infection studies demonstrated that I. scapularis and Ixodes pacificus became infected and maintained the virus transstadially following oral exposure to viremic host models (Anderson et al. 2003, Reisen et al. 2007). Nevertheless, further examination of the potentially sex-dependent infection of tick organs by WNV is warranted.

While the NS regions were shown to be primary predictors of replication competence, attenuation was demonstrated by each chimeric virus in Vero cells, C6/36, and ISE6 cells, suggesting that inclusion of heterologous structural regions had a mitigating effect on replication. A sequence alignment between the prME regions of DTV and WNV indicates a nucleotide identity of 50% and an amino acid identity of only 37.6%, highlighting the genomic and potentially functional divergence of these proteins. Conserved elements within this region have been implicated with playing a role in prM-E interactions and prM/M cleavage (Guirakhoo et al. 1992, Heinz et al. 1994). Similarly, the lack of conservation in the α-helical domain in the M protein has also been shown to be important for proper maturation of viral particles, viral entry, and formation of E homodimers following pr-M cleavage (Wengler and Wengler 1989, Stiasny et al. 1996, Hsieh et al. 2014).

Vector group-specific characteristics of the structural E protein have also been described that could account for attenuation of chimeric viruses described herein. Initial studies of domain III of the E protein, a region largely implicated in receptor binding, have demonstrated that characteristics of this region may be important for mediating vector-specific interactions, including the proposed receptor-binding site for TBFV. It has previously been shown that the pH-dependent conformational rearrangement of flavivirus particles from E dimers to E trimers is required for subsequent membrane fusion (Stiasny et al. 1996). Examinations of the dynamic properties of TBFV and MBFV recombinant E domain III proteins have suggested that TBFV has an increased tolerance to a wider range of environmental conditions, including low pH, which may contribute to their ability to persist in tissues and fluids such as milk and still be viable for transmission (Yu et al. 2004).

While the hypothesis that NS proteins largely drive flavivirus host association was supported in both in vivo and in vitro tick cells, in vitro mosquito cells, and Vero cells, the determinants of mosquito competence and growth in BHK cells were not fully explained. Specifically, DTV-prME/WNV growth was largely attenuated compared with WNV in mosquitoes and BHK cells, yet the WNV-prME/DTV chimera behaved no differently from DTV. BHK cells were utilized in an attempt to model the ecology of DTV that utilizes a rodent reservoir in nature. These findings could indicate different receptor-mediated effects of structural genes between WNV and DTV in BHK cells.

Alternatively, examination of the interaction between flaviviruses and host type I IFN response has indicated likely virus–host specificity. For instance, TRIM79α, an interferon-stimulated gene, has been previously shown to restrict TBFV through targeted lysosomal-dependent decay of NS5, a known type I IFN antagonist (Best et al. 2005). Interestingly, this targeted degradation of NS5 was specific to TBFV and did not act on WNV-derived NS5 (Taylor et al. 2011). However, a study comparing type I IFN restriction of multiple flaviviruses in primary cells from Peromyscus leucopus, a predicted reservoir host for DTV, and Mus musculus showed that while replication restriction as a result of IFN was limited to P. leucopus cells, both TBFV and MBFV were attenuated (Izuogu et al. 2017). This highlights the complex arms race occurring between virus replication and its reservoir host's innate immunity.

The observed phenotypes of infection in mosquitoes also did not support the hypothesis that NS elements are the primary determinants of competent infection and replication as the DTV-prME/WNV chimera showed no infection in C. pipiens. It should be noted that this experimental finding was based on a small number of mosquitoes (N = 12), so while we are not confident saying that the DTV-prME/WNV chimera is unable to infect mosquitoes, we can conclude that the ability to infect is significantly diminished compared with the WNV parental. It is possible that this is related to the absence of the fusion loop region in the DTV-prME. Interestingly, the fusion loop region of 4 amino acids in domain III of the E glycoprotein is present and conserved in MBFV, but absent in TBFV. Mutagenesis studies have indicated that the absence of this fusion loop drastically reduced MBFV replication in Vero cells and the infection rate in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, but not growth in C6/36 cells (Erb et al. 2010). The growth characterization results demonstrate that DTV-prME/WNV was able to grow in C6/36 cells, but was unable to infect Culex mosquitoes per os, which could be explained by the absence of this fusion loop in DTV-prME regions of the chimeric virus.

Although not assessed in this study, future studies will consider the role of noncoding determinants of in vivo vector specificity. A conserved feature identified in the 3′ UTR of flaviviruses is elements that generate subgenomic flavivirus RNA (sfRNA) upon interaction with host 5′–3′ exoribonuclease. Following oral infection of sfRNA-deficient WNV mutants, reduced rates of C. pipiens infection and transmission were observed, whereas uninhibited transmission and infection rates were observed following intrathoracic inoculation in C. pipiens. This suggests that sfRNA is likely associated with viral evasion of the midgut infection or escape barrier (Goertz et al. 2016). While, the role of TBFV sfRNA for knockdown of RNAi for in vitro tick cell models has also been demonstrated (Schnettler et al. 2014), it is unclear if the sfRNA of each TBFV and MBFV is uniquely adapted to their respective vectors, thus acting as a limiting factor for infection/replication in the nontraditional insect vector.

The work described herein shows that NS regions are largely responsible for determinants of replication competence for in vitro vector models. It also highlighted different key determinants for replication in ticks and mosquitoes. Future studies will focus on in silico structural modeling and mutational analysis of 3′UTR sfRNA sequences between MBFV and TBFV, targeted site-directed mutagenesis of heterologous prME elements of interest, and detailed determination of genomic sites under selective pressures by way serial passaging and temperature sensitivity studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jason Velez for cell culture maintenance and Karen Boroughs and Janae Stovall for running the sequencing core. J.L.K. was funded by an ASM/CDC postdoctoral fellowship, M.E.H. was supported by the Kempner postdoctoral fellowship, and S.T. is supported by NIH/NIAID grants R01AI127771 and R21AI113128. Findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflicting financial interests exist.

References

- Abbassy MM, Osman M, Marzouk AS. West Nile virus (Flaviviridae:Flavivirus) in experimentally infected Argas ticks (Acari:Argasidae). Am J Trop Med Hyg 1993; 48:726–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JF, Magnarelli LA. Avian and mammalian hosts for spirochete-infected ticks and insects in a Lyme disease focus in Connecticut. Yale J Biol Med 1984; 57:627–641 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JF, Main AJ, Andreadis TG, Wikel SK, et al. Transstadial transfer of West Nile virus by three species of ixodid ticks (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol 2003; 40:528–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley DW, Whiteman MC, Zhang S, Huang CY, et al. Envelope protein glycosylation status influences mouse neuroinvasion phenotype of genetic lineage 1 West Nile virus strains. J Virol 2005; 79:8339–8347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best SM, Morris KL, Shannon JG, Robertson SJ, et al. Inhibition of interferon-stimulated JAK-STAT signaling by a tick-borne flavivirus and identification of NS5 as an interferon antagonist. J Virol 2005; 79:12828–12839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh CE, Muscat PL, Telford SR, 3rd, Goethert H, et al. Fatal deer tick virus infection in Maine. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:1043–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlier N, Davidson A, Dallmeier K, Molenkamp R, et al. Replication of not-known-vector flaviviruses in mosquito cells is restricted by intracellular host factors rather than by the viral envelope proteins. J Gen Virol 2010; 91:1693–1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlier N, Molenkamp R, Leyssen P, Vandamme AM, et al. A rapid and convenient variant of fusion-PCR to construct chimeric flaviviruses. J Virol Methods 2003; 108:67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis AP, 2nd, Peters RJ, Prusinski MA, Falco RC, et al. Isolation of deer tick virus (Powassan virus, lineage II) from Ixodes scapularis and detection of antibody in vertebrate hosts sampled in the Hudson Valley, New York State. Parasit Vectors 2013; 6:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel AR, Mitzel DN, Hanson CT, Wolfinbarger JB, et al. Chimeric tick-borne encephalitis/dengue virus is attenuated in Ixodes scapularis ticks and Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2011; 11:665–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb SM, Butrapet S, Moss KJ, Luy BE, et al. Domain-III FG loop of the dengue virus type 2 envelope protein is important for infection of mammalian cells and Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Virology 2010; 406:328–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista J, Cruz C, Guevara C, Astete H, et al. Characterization of a novel flavivirus isolated from Culex (Melanoconion) ocossa mosquitoes from Iquitos, Peru. J Gen Virol 2013; 94:1266–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formosinho P, Santos-Silva MM. Experimental infection of Hyalomma marginatum ticks with West Nile virus. Acta Virol 2006; 50:175–180 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goertz GP, Fros JJ, Miesen P, Vogels CB, et al. Noncoding subgenomic flavivirus RNA is processed by the mosquito RNA interference machinery and determines West Nile Virus transmission by Culex pipiens mosquitoes. J Virol 2016; 90:10145–10159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman CH, Russell BJ, Velez JO, Laven JJ, et al. Development of an algorithm for production of inactivated arbovirus antigens in cell culture. J Virol Methods 2014; 208:66–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould EA, de Lamballerie X, Zanotto PM, Holmes EC. Origins, evolution, and vector/host coadaptations within the genus Flavivirus. Adv Virus Res 2003; 59:277–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guirakhoo F, Bolin RA, Roehrig JT. The Murray Valley encephalitis virus prM protein confers acid resistance to virus particles and alters the expression of epitopes within the R2 domain of E glycoprotein. Virology 1992; 191:921–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz FX, Stiasny K, Puschner-Auer G, Holzmann H, et al. Structural changes and functional control of the tick-borne encephalitis virus glycoprotein E by the heterodimeric association with protein prM. Virology 1994; 198:109–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinze DM, Gould EA, Forrester NL. Revisiting the clinal concept of evolution and dispersal for the tick-borne flaviviruses by using phylogenetic and biogeographic analyses. J Virol 2012; 86:8663–8671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermance ME, Thangamani S. Tick saliva enhances Powassan virus transmission to the host, influencing its dissemination and the course of disease. J Virol 2015; 89:7852–7860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermance ME, Thangamani S. Powassan virus: An emerging arbovirus of public health concern in North America. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2017; 17:453–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh SC, Wu YC, Zou G, Nerurkar VR, et al. Highly conserved residues in the helical domain of dengue virus type 1 precursor membrane protein are involved in assembly, precursor membrane (prM) protein cleavage, and entry. J Biol Chem 2014; 289:33149–33160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhtamo E, Putkuri N, Kurkela S, Manni T, et al. Characterization of a novel flavivirus from mosquitoes in northern Europe that is related to mosquito-borne flaviviruses of the tropics. J Virol 2009; 83:9532–9540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izuogu AO, McNally KL, Harris SE, Youseff BH, et al. Interferon signaling in Peromyscus leucopus confers a potent and specific restriction to vector-borne flaviviruses. PLoS One 2017; 12:e0179781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junglen S, Kopp A, Kurth A, Pauli G, et al. A new flavivirus and a new vector: Characterization of a novel flavivirus isolated from uranotaenia mosquitoes from a tropical rain forest. J Virol 2009; 83:4462–4468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, et al. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 2012; 28:1647–1649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney JL, Solberg OD, Langevin SA, Brault AC. Characterization of a novel insect-specific flavivirus from Brazil: Potential for inhibition of infection of arthropod cells with medically important flaviviruses. J Gen Virol 2014; 95:2796–2808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney RM, Huang CY, Whiteman MC, Bowen RA, et al. Avian virulence and thermostable replication of the North American strain of West Nile virus. J Gen Virol 2006; 87:3611–3622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokonova MS, Borisevich SV, Grabarev PA, Bondarev VP. [Experimental assessment of the possible significance of argasid ticks in preserving the natural foci of West Nile virus infection]. Med Parazitol (Mosk) 2013:33–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziejek J, Pachler K, Bin H, Mendelson E, et al. Barkedji virus, a novel mosquito-borne flavivirus identified in Culex perexiguus mosquitoes, Israel, 2011. J Gen Virol 2013; 94:2449–2457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothera L, Godsey M, Mutebi JP, Savage HM. A comparison of aboveground and belowground populations of Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) mosquitoes in Chicago, Illinois, and New York City, New York, using microsatellites. J Med Entomol 2010; 47:805–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuno G, Chang GJ, Tsuchiya KR, Karabatsos N, et al. Phylogeny of the genus Flavivirus. J Virol 1998; 72:73–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrie CH, Uzcategui NY, Gould EA, Nuttall PA. Ixodid and argasid tick species and West Nile virus. Emerg Infect Dis 2004; 10:653–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Grubaugh ND, Kondig JP, Turell MJ, et al. Isolation and genomic characterization of Chaoyang virus strain ROK144 from Aedes vexans nipponii from the Republic of Korea. Virology 2013; 435:220–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenbach BD, Rice CM. Flaviviridae: The viruses and their replication. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, eds. Fundamental Virology. Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams and Wilkins, 2001:589–639 [Google Scholar]

- Lindenbach BD, Theil H-J, Rice CM. Flaviviridae: The viruses and their replication. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, eds. Fields' Virology. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007, 2006:1102–1152 [Google Scholar]

- Lwande OW, Lutomiah J, Obanda V, Gakuya F, et al. Isolation of tick and mosquito-borne arboviruses from ticks sampled from livestock and wild animal hosts in Ijara District, Kenya. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2013; 13:637–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lwande OW, Venter M, Lutomiah J, Michuki G, et al. Whole genome phylogenetic investigation of a West Nile virus strain isolated from a tick sampled from livestock in north eastern Kenya. Parasit Vectors 2014; 7:542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharaj PD, Anishchenko M, Langevin SA, Fang Y, et al. Structural gene (prME) chimeras of St Louis encephalitis virus and West Nile virus exhibit altered in vitro cytopathic and growth phenotypes. J Gen Virol 2012; 93:39–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean LD, Donohue WL. Powassan virus: Isolation of virus from a fatal case of encephalitis. Can Med Assoc J 1959; 80:708–711 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskvitina NS, Romanenko VN, Ternovoi VA, Ivanova NV, et al. [Detection of the West Nile Virus and its genetic typing in ixodid ticks (Parasitiformes: Ixodidae) in Tomsk City and its suburbs]. Parazitologiia 2008; 42:210–225 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumcuoglu KY, Banet-Noach C, Malkinson M, Shalom U, et al. Argasid ticks as possible vectors of West Nile virus in Israel. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2005; 5:65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munderloh UG, Liu Y, Wang M, Chen C, et al. Establishment, maintenance and description of cell lines from the tick Ixodes scapularis. J Parasitol 1994; 80:533–543 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nofchissey RA, Deardorff ER, Blevins TM, Anishchenko M, et al. Seroprevalence of powassan virus in new England deer, 1979–2010. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013; 88:1159–1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen LR, Marfin AA. Shifting epidemiology of Flaviviridae. J Travel Med 2005; 12 Suppl 1:S3–S11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson JH, Fiz-Palacios O. Dating the origin of the genus Flavivirus in the light of Beringian biogeography. J Gen Virol 2014; 95:1969–1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piantadosi A, Rubin DB, McQuillen DP, Hsu L, et al. Emerging cases of Powassan virus encephalitis in New England: Clinical presentation, imaging, and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:707–713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletnev AG, Bray M, Huggins J, Lai CJ. Construction and characterization of chimeric tick-borne encephalitis/dengue type 4 viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992; 89:10532–10536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Policastro PF, Schwan TG. Experimental infection of Ixodes scapularis larvae (Acari: Ixodidae) by immersion in low passage cultures of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Med Entomol 2003; 40:364–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisen WK, Brault AC, Martinez VM, Fang Y, et al. Ability of transstadially infected Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae) to transmit West Nile virus to song sparrows or western fence lizards. J Med Entomol 2007; 44:320–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnettler E, Tykalova H, Watson M, Sharma M, et al. Induction and suppression of tick cell antiviral RNAi responses by tick-borne flaviviruses. Nucleic Acids Res 2014; 42:9436–9446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiasny K, Allison SL, Marchler-Bauer A, Kunz C, et al. Structural requirements for low-pH-induced rearrangements in the envelope glycoprotein of tick-borne encephalitis virus. J Virol 1996; 70:8142–8147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RT, Lubick KJ, Robertson SJ, Broughton JP, et al. TRIM79alpha, an interferon-stimulated gene product, restricts tick-borne encephalitis virus replication by degrading the viral RNA polymerase. Cell Host Microbe 2011; 10:185–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tutolo JW, Staples JE, Sosa L, Bennett N. Notes from the Field: Powassan virus disease in an infant—Connecticut, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017; 66:408–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HJ, Li XF, Ye Q, Li SH, et al. Recombinant chimeric Japanese encephalitis virus/tick-borne encephalitis virus is attenuated and protective in mice. Vaccine 2014; 32:949–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wengler G, Wengler G. Cell-associated West Nile flavivirus is covered with E+pre-M protein heterodimers which are destroyed and reorganized by proteolytic cleavage during virus release. J Virol 1989; 63:2521–2526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshii K, Goto A, Kawakami K, Kariwa H, et al. Construction and application of chimeric virus-like particles of tick-borne encephalitis virus and mosquito-borne Japanese encephalitis virus. J Gen Virol 2008; 89:200–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Wuu A, Basu R, Holbrook MR, et al. Solution structure and structural dynamics of envelope protein domain III of mosquito- and tick-borne flaviviruses. Biochemistry 2004; 43:9168–9176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]