Abstract

A practical, efficient and broadly applicable catalytic method for synthesis of easily differentiable vicinal diboronate compounds is presented. Reactions are promoted by a combination of PCy3 or PPh3, CuCl and LiOt-Bu and may be performed with readily accessible alkenyl boronate substrates. Through the use of an alkenyl–B(pin) (pin = pinacolato) or alkenyl– B(dan) (dan = naphthalene-1,8-diaminato) starting material and commercially available (pin)B– B(dan) or B2(pin)2 as the reagent, a range of vicinal diboronates, including those that contain a B-substituted quaternary carbon center, may be prepared in up to 91% yield and with >98% site selectivity. High enantioselectivities can be obtained (up to 96:4 er) through the use of commercially available chiral bis-phosphine ligands for reactions that afford mixed diboronate products.

Keywords: Allylic substitution, Boron, Catalysis, Copper, Enantioselective synthesis, Vicinal diboron compounds

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

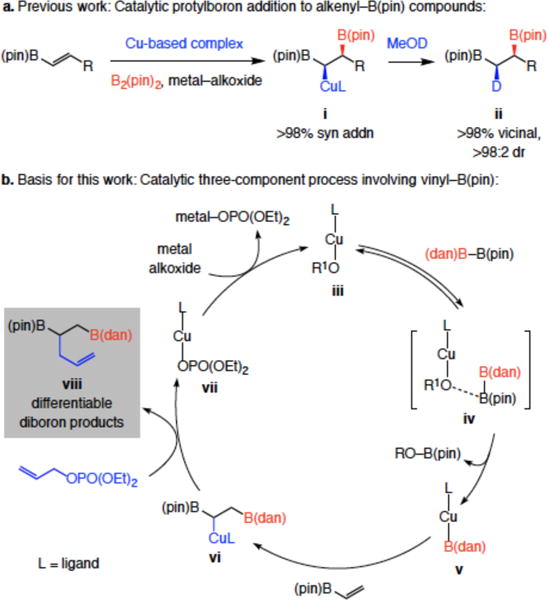

Organoboron compounds that contain vicinal C–B(pin) (pin = pinacolato) bonds are of considerable value in chemical synthesis and may be accessed through diboron additions to alkenes catalyzed by Pd- or Pt-based complexes,1 metal alkoxides2 or carbohydrate-based diboron species.3 A primary C–B bond may be induced to undergo cross-coupling reactions site selectively because of activation provided by the neighboring, more substituted C–B(pin) unit.4 In 2009 we showed that vicinal diboronate compounds may be synthesized through exceptionally site-selective (<2% geminal diboronate) and stereoselective (syn) Cu–B(pin) addition to alkenyl–B(pin) moiety; the resulting Cu–C bond was then reacted with deuterio-methanol in situ, affording ii with complete diastereoselectivity (>98% retention of stereochemistry; Scheme 1a).5 More recently, we envisioned that three-component fusion of an alkenyl–B(pin) with (dan)B–B(pin) (dan = naphthalene-1,8-diaminato)6 and an allyl electrophile (in place of MeOH) might deliver, through site-selective Cu–B(dan) addition/allylic substitution,7 valuable easy-to-differentiate vicinal diboronate products (e.g., viii, Scheme 1b). Specifically, we surmised that the intermediate copper-alkoxide (iii, Scheme 1b) should favor interaction with the more Lewis acidic B(pin) unit (iv), which would afford a Cu-B(dan) complex (v) along with products containing a terminal B(dan) and an internal B(pin) group (vi). Differentiation of a B(pin) and a B(dan) moiety would be easier [vs two B(pin) groups]; as a result, the method would offer a distinct advantage, especially when selective functionalization at the typically less reactive secondary C–B bond is desired [e.g., internal B(pin) and a terminal B(dan) group]. Alternatively, a sequence involving an alkenyl–B(dan) substrate and B2(pin)2 would furnish the complementary diboron isomer [i.e., primary C–B(pin) and secondary C–B(dan)]. Herein, we disclose the realization of these objectives.

Scheme 1.

Related previous work and the basis for the present studies.

2. Results and discussion

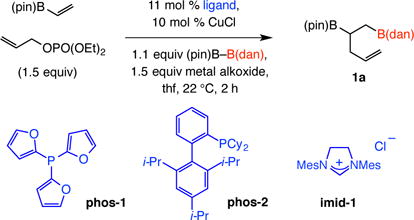

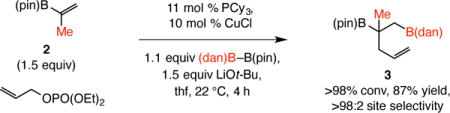

We first probed the possibility of a three-component process with vinyl–B(pin), allylphosphate and (dan)B–B(pin) (Table 1).8 With NaOt-Bu as the base but without a ligand there was near complete (~95%) disappearance of the limiting reagent [(vinyl– B(pin)] but 1a was obtained in 39% yield (entry 1). Efficiency improved substantially with the addition of 11.0 mol % PPh3, as vicinal diboronate 1a was isolated in 78% yield (entry 2). Evaluation of other alkali metal alkoxides (entries 3–4) and several mono- and bidentate phosphines with distinct steric and electronic attributes (entries 5–9) indicated that the combination of PCy3 and LiOt-Bu is optimal (>98% conv, 84% yield; entry 6, Table 1). Reactions with N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) complexes of copper were less efficient (e.g., entry 10), probably arising from competitivereaction of the Cu–B(dan) with allylphosphate to afford allyl–B(dan)9 (i.e., lower chemoselectivity).

Table 1.

Examination of different Cu complexes.a

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| entry | ligand | alkoxide | conv (%)b | yield (%)c |

| 1 | none | NaOt-Bu | 93 | 39 |

| 2 | PPh3 | NaOt-Bu | >98 | 78 |

| 3 | PPh3 | LiOt-Bu | >98 | 81 |

| 4 | PPh3 | KOt-Bu | 91 | 58 |

| 5 | P(nBu)3 | LiOt-Bu | 96 | 77 |

| 6 | PCy3 | LiOt-Bu | >98 | 84 |

| 7 | phos-1 | LiOt-Bu | 50 | 19 |

| 8 | phos-2 | LiOt-Bu | 43 | 21 |

| 9 | rac-binap | LiOt-Bu | 74 | 61 |

| 10 | imid-1 | LiOt-Bu | 86 | 18 |

Performed under N2 atm.

Determined by analysis of 1H NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures; conv. (±2%) refers to disappearance of vinyl–B(pin).

Yields of isolated and purified products (±5%). See the Supporting Information for details. Abbreviations: pin, pinacolato; Mes, 2,4,6-(Me)3C6H2, dan = naphthalene-1,8-diaminato.

A variety of 2-substituted allylic phosphates, including those that contain a versatile allyl silyl ether (1c), an alkenyl silyl group (1e), a furyl moiety (1f), or a chloride or bromide that might be used in catalytic cross-coupling (1g, 1h), may be used (Scheme 2). Products containing a primary C–B(dan) bond and a secondary C– B(pin) moiety were generated with complete selectivity: <2% of the alternative isomer could be detected based on 1H NMR spectra of the unpurified mixtures. The identity of the products was ascertained by determination of X-ray structures of 1d and 1f (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Reactions with 2-substituted allylic phosphates. See the Supporting Information for experimental and analytical details.

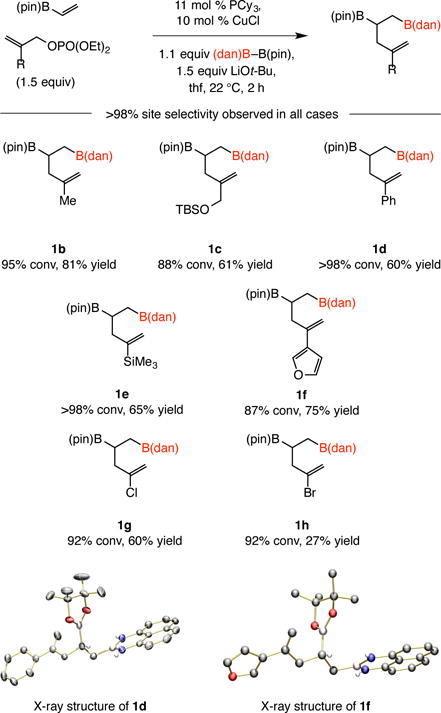

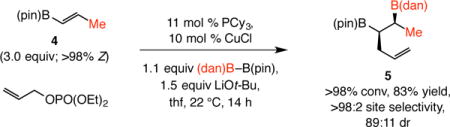

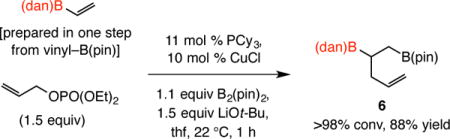

As the transformation in Eq. 1 illustrated, the method is applicable to the formation of a boron-substituted quaternary carbon center.10 Thus, diboronate 3 was obtained in 87% yield after four hours at room temperature. Conversion of the commercially available 1,2-disubstituted alkenylboronate 4 to 5, isolated in 83% yield, further highlights the utility of the method (Eq. 2). This latter transformation is especially notable; although longer reaction time was needed (14 vs 1–4 h), site- and diastereoselectivity levels were high [>98:2 vicinal:geminal, 89:11 diastereomeric ratio (dr)]. Similarly noteworthy is the transformation with vinyl–B(dan) (Eq. 3), accessible in a single step from vinyl–B(pin), leading to the formation (>98% conv, 1 h) of the transposed diboronate product 6 in 88% yield, the identity of which was confirmed by X-ray crystallography.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

Reactions are scalable, as illustrated by the example in Eq. 4. The transformations were performed with 2.5 mol % of the phosphine–copper complex (vs 10 mol % used above), although this required a longer reaction time (12 vs 2 h).

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

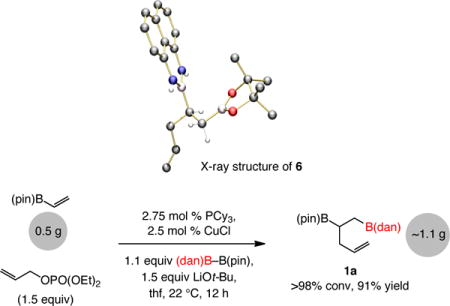

The C–B(pin) bond of the bis-boronate products can be site selectively oxidized to afford the corresponding alcohol products (e.g., 7 and 8, Scheme 3). The remaining C–B(dan) bond can then be converted to a C–C bond,11 as the examples in Scheme 3, leading to the formation of silyl ethers 10 and 12 illustrate. In these latter transformations, C–B(pin) oxidation/B(dan)-to-B(pin) exchange/silyl ether formation afforded products 9 and 11 in 71% and 65% yield, respectively, after a single purification. The state-of-the-art regarding direct conversion of a C–B(dan) to a C–C bond by catalytic cross-coupling is less advanced [vs those containing a C–B(pin)];6,12 future developments in this key area will likely elevate the utility of the approach.

Scheme 3.

Functionalization through chemoselective oxidation and cross-coupling. See the Supporting Information for experimental and analytical details.

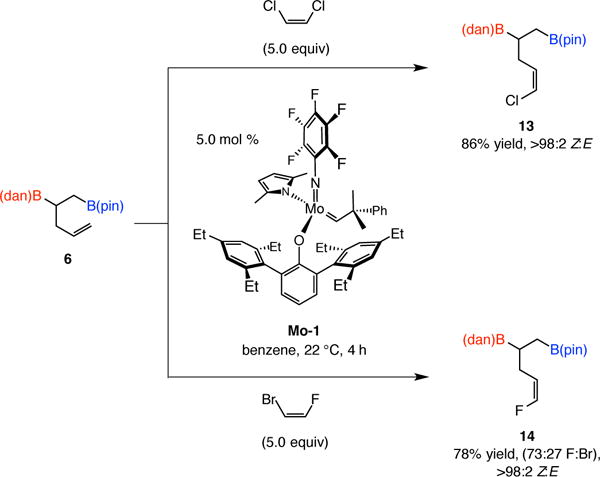

Another example of product modification takes advantage of recently developed catalyst-controlled stereoselective cross-metathesis approaches for accessing alkenyl halide compounds (Scheme 4).13 Z-Alkenyl chloride 13, offers three distinct sites for highly site-selective catalytic cross-coupling reactions, and alkenyl fluoride 14 should allow access to various other desirable organofluorine compounds.14

Scheme 4.

Functionalization through catalytic Z-selective cross-metathesis reactions. See the Supporting Information for experimental and analytical details.

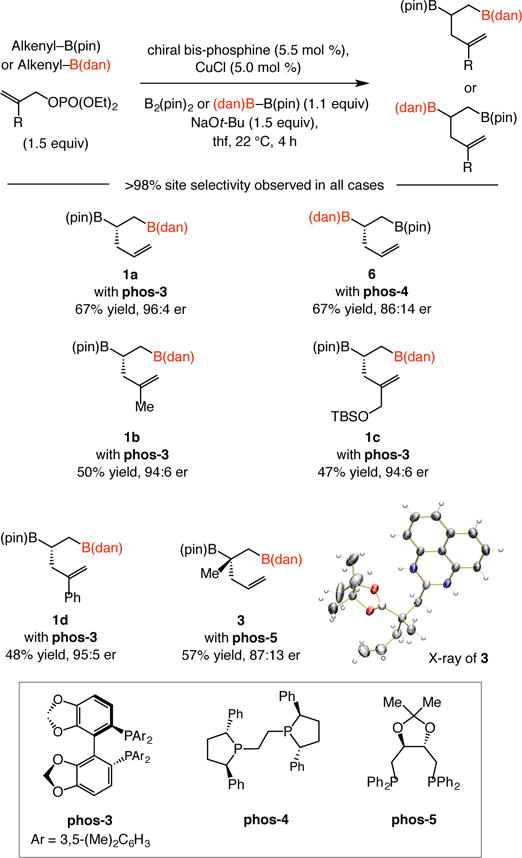

Initial studies indicate that high enantioselectivity may be achieved with this class of transformations through the use of commercially available chiral bis-phosphine ligands (Scheme 5).15 Thus, diboronates 1a and 6 were obtained in 96:4 and 86:14 er, respectively. The examples involving 1b, silyl allyl ether 1c (47% yield and 94:6 er) as well as styrene 1d, and 3, which contains a B-substituted quaternary carbon stereogenic center (57% yield, 87:13 er) represent additional promising results in regards to accessing readily differentiable vicinal diboronate products enantioselectively. The identity of diboronate product 3 was ascertained through X-ray crystallography.15

Scheme 5.

Catalytic enantioselective variants. For 3, 1.5:1 ratio of vinyl– B(pin): allylphosphate was used; see the Supporting Information for experimental and analytical details.

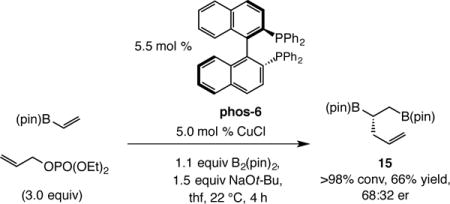

It merits note that transformations affording mixed bis–B(pin) products16 do not proceed with similarly high levels of enantomeric purity. For example, as presented in Eq. 5, the highest enantioselectivity that we were able to obtain in the formation of diboronate 15 was 68:32 (vs 96:4 and 86:14 er for 1a and 6).

|

(5) |

3. Conclusions

In summary, the catalytic multicomponent processes described here offer a practical, direct and strategically distinct entry to a variety of easily differentiable vicinal diboronate compounds. The ability for facile access to either regioisomeric product with a C– B(pin) and an adjacent C–B(dan) bond that can be site selectively modified is a noteworthy feature of the new approach. Future studies will be aimed at expanding the scope of the enantioselective variants and applications towards development of other catalytic protocols that deliver versatile and valuable organoboron compounds are in progress.

4. Experimental section

4.1. General

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the National Institutes of Health (GM-57212 and, in part, GM-59426). We thank J. del Pozo, M. J. Koh and T. T. Nguyen for helpful advice.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.xxxxx.

References

- 1.For representative reports, see:; (a) Trudeau S, Morgan JB, Shreshta M, Morken JP. J Org Chem. 2005;70:9538–9544. doi: 10.1021/jo051651m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Coombs JR, Haeffner F, Kliman LT, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:11222–11231. doi: 10.1021/ja4041016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For processes promoted by Rh-based complexes, see:; (c) Toribatake K, Nishiyama H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:11011–11015. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Bonet A, Pubill-Ulldemolins C, Bo C, Gulyás H, Fernandez E. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:7158–7161. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Blaisdell TP, Caya TC, Zhang L, Sanz-Marco A, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9264–9267. doi: 10.1021/ja504228p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Miralles N, Cid J, Cuenca AB, Carbó JJ, Fernandez E. Chem Commun. 2015;51:1693–1696. doi: 10.1039/c4cc08743g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang L, Yan L, Haeffner F, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:2508–2511. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b13174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Mlynarski SN, Schuster CH, Morken JP. Nature. 2014;505:386–390. doi: 10.1038/nature12781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For a related observation, see:; (b) Lee Y, Jang H, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:18234–18235. doi: 10.1021/ja9089928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Ref 4b. For an application in synthesis of a biologically active molecules, see:; (b) Meek SJ, O’Brien RV, Llaveria J, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. Nature. 2011;471:461–466. doi: 10.1038/nature09957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For a related study, see:; (c) Jung HY, Yun J. Org Lett. 2012;14:2606–2609. doi: 10.1021/ol300909k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Iwadate N, Suginome M. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2548–2549. doi: 10.1021/ja1000642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For representative subsequent studies involving the use of (dan)B–B(pin), see:; (b) Sake R, Hirano K, Miura M. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:6460–6463. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b02775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Guo X, Nelson AK, Slebodnick C, Santos WL. ACS Catal. 2015;5:2172–2176. [Google Scholar]; (d) Ref 2c.; (e) Nishikawa D, Hirano K, Miura M. Org Lett. 2016;18:4856–4859. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.For related processes involving aryl olefins and promoted by a combination of a chiral bis-phosphine–Cu and an achiral bis-phosphine–Pd co-catalyst, see:; (a) Jia T, Cao P, Wang B, Lou Y, Yin X, Wang M, Liao J. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:13760–13763. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b09146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For transformations that commence with an enantioselective Cu–H addition, see:; (b) Wang YM, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:5024–5027. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Han JT, Jang WJ, Kim N, Yun J. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:15146–15149. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lee J, Torker S, Hoveyda AH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:821–826. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For previous catalytic multicomponent reactions that entail Cu–B addition to an alkenyl site followed by an allylic substitution reaction, see:; Meng F, McGrath KP, Hoveyda AH. Nature. 2014;513:367–374. doi: 10.1038/nature13735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Ito H, Ito S, Sasaki Y, Matsuura K, Sawamura M. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14856–14857. doi: 10.1021/ja076634o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Guzman-Martinez A, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10634–10637. doi: 10.1021/ja104254d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.For examples of catalytic methods for formation of boron-substituted quaternary carbon stereogenic centers, see:; (a) Chen IH, Yin L, Itano W, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:11664–11665. doi: 10.1021/ja9045839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ref 9b.; (c) O’Brien JM, Lee K-s, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10630–10633. doi: 10.1021/ja104777u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Dudnik AS, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:10693–10697. doi: 10.1021/ja304068t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Ito H, Kubota K. Org Lett. 2012;14:890–893. doi: 10.1021/ol203413w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Radomkit S, Hoveyda AH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:3387–3391. doi: 10.1002/anie.201309982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Atack TC, Leckere RM, Cook SP. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9521–9523. doi: 10.1021/ja505199u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Hu N, Zhao G, Zhang Y, Liu X, Li G, Tang W. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:6746–6749. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Wu H, Garcia JM, Haeffner F, Radomkit S, Zhugralin AR, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:10585–10602. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Li C, Wang J, Barton LM, Yu S, Tian M, Peters DS, Kumar M, Yu AW, Johnson KA, Chatterjee AK, Yan M, Baran PS. Science. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Chakrabarty S, Tackacs JM. J Am Chem Soc. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b02324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonet A, Odachowski M, Leonori D, Essafi S, Aggarwal VK. Nature Chem. 2014;6:584–589. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Noguchi H, Hojo K, Suginome M. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:758–759. doi: 10.1021/ja067975p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Iwadate N, Suginome M. Org Lett. 2009;11:1899–1902. doi: 10.1021/ol9003096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Koh MJ, Nguyen TT, Zhang H, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. Nature. 2016;531:459–464. doi: 10.1038/nature17396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For the corresponding kinetically E-selective cross-metathesis reactions, see:; (b) Nguyen TT, Koh MJ, Shen X, Romiti F, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. Science. 2016;352:569–575. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.For examples of biologically active molecules that contain a Z- or an E-alkenyl fluoride group, see:; (a) Kolb M, Barth J, Heydt JG, Jung MJ. J Med Chem. 1987;30:267–272. doi: 10.1021/jm00385a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wnuk SF, Lalama J, Garmendia CA, Robert J, Zhu J, Pei D. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:5090–5102. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For a general overview, see:; (c) Gillis EP, Eastman KJ, Hill MD, Donnelly DJ, Meanwell NA. J Med Chem. 2015;58:8315–8359. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.See the Supporting Information for results of screening studies

- 16.See the Supporting Information for the full range of reactions affording vicinal di–B(pin) compounds

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.