Abstract

This study uses mixed-methods data and a life-course perspective to explore the role of pets in the lives of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) adults age 50 and over and addresses the following research questions: (1) How does having a pet relate to perceived social support and social network size? and (2) how do LGBT older adults describe the meaning of pets in their lives? The qualitative data (N = 59) were collected from face-to-face interviews, and the quantitative data (N = 2,560) were collected via surveys from a sample across the United States. Qualitative findings show that pets are characterized as kin and companions and provide support; we also explore why participants do not have pets. The quantitative findings show that LGBT older adults with a pet had higher perceived social support; those with a disability and limited social network size, who had a pet had significantly higher perceived social support than those without a pet.

Keywords: LGBT older adults, pets, social support, life course

The population of adults age 65 and older in the United States is becoming more diverse and growing steadily, with estimates that it will double by 2050 (Ortman, Velkoff, & Hogan, 2014). Historically, one segment of this growing population, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) adults, have been understudied, resulting in inadequate services, elevated health risks, and a need for more research (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Muraco, 2010; Institute of Medicine, 2011). Two areas that require further inquiry are the risk and protective factors associated with health and mental health outcomes and the role of social support in its various forms (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Muraco, 2010; Muraco & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2011).

In the United States, the role of companion animals, hereafter to be referred to as “pets,” is also growing. Approximately 68% of U.S. households include a pet (American Pet Products International, 2014), and pets are often considered family members (Risley-Curtiss et al., 2006). Although empirical research on human–animal interaction has shown positive health effects of having a pet, the evidence provides inconsistent results (Herzog, 2011); in theoretical works, the human–animal bond has been addressed as an important form of kinship (Haraway, 2003; McKeithen, 2017). Studies of human–animal interactions need to further examine the connection between having a pet and social support, the relationship between having a pet a physical and mental health, and the meanings that older adults subjectively ascribe to the benefits and challenges of having a pet.

This study bridges the gaps in research about LGBT older adults’ social support and the role of pets. Our mixed-methods study uses a life-course perspective and examines survey and interview data from LGBT adults, age 50 and older, to examine how pet ownership relates to social resources, including social support and networks, as well as to understand how pet owners perceive pets’ roles in their lives. The study is comprised of data from (N = 2,560) surveys from the national Aging with Pride study and in-depth face-to-face interviews (n = 59) with a subsample of survey participants. These data were collected between 2010 and 2014 and include questions about background characteristics, mental and physical health status, social networks, presence of a pet, and the significance of a pet in participants’ lives.

Background

At the theoretical foundation of the study is a life-course perspective, particularly, the understanding that aging is a process that is shaped by cumulative life experiences and dependent upon opportunities that exist within a given social context (Dannefer & Settersten, 2010). Within this framework, we consider how experiences within the life course intersect with the roles of pets in later life. Structural contexts that have shaped the lives of LGBT older adults include the history of criminalization and stigmatization of the same-sex identities and a lack of legal protections (Hammack & Cohler, 2011; Muraco & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2016) but also the construction of chosen families as a network to provide support when other forms were not readily available (Weston, 1991). The life-course perspective addresses how cumulative experience and thus the aging process itself is highly variable among individuals and groups (Dannefer & Settersten, 2010), which can affect and be affected by social ties.

The background of this study derives from three areas of inquiry: the role of social support in aging, sexual and gender minority populations in midlife and later life, and the human–animal bond. We will briefly describe each here.

Emerging literature suggests that perceived social support has direct and indirect effects on physical and mental health (Bekele, Carroll, Roux, Fitzpatrick, & Seeman, 2013). Higher levels of social support are protective against metabolic processes, such as inflammation, chronic pain, and physical aging in later life, by reducing older adults’ experience of the physiological stress response (Carroll, Roux, Fitzpatrick, & Seeman, 2013). Conversely, among older adults, depressive symptoms are positively correlated with a small social network, living alone without a partner, and low emotional support (Sonnenberg et al., 2013). In addition, results from a racially/ethnically diverse community sample of men and women found that low social support is associated with increased cellular aging in adults aged 65 and older (Carroll et al., 2013). Despite the documented risk and protective factors associated with varying levels of perceived social support, there is little consensus in the literature about how to define it. Based on the work of Sherbourne and Stewart (1991), this study draws on a multidimensional model of social support that includes tangible aspects of support (i.e., provision of material aid), emotional–informational (i.e., empathic understanding and guidance), positive social interaction (i.e., availability of others to engage in activities), and affectionate support (i.e., love).

Data from Aging with Pride: The National Health, Aging and Sexuality Study (NHAS) demonstrate that sexual and gender minorities in midlife and later life are at elevated risk for disability, poor physical health, and depression (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013; Wallace, Cochran, Durazo, & Ford, 2011). Results from a population-based study show that lesbian and bisexual women have higher odds than heterosexual women of having a disability and poor mental health; gay and bisexual men also have higher odds than heterosexual men of having disability, as well as poor physical and mental health (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013). Existing research also demonstrates that social resources play an important role in resilience and quality of life of LGBT older adults (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Shiu, Goldsen, & Emlet, 2015). Other research suggests that the social support networks of older LGBT adults are characterized by closer ties to friends and neighbors, in contrast to the reliance on biological family that is the cornerstone of social support for most heterosexual older adults (Brennan-Ing, Seidel, Larson, & Karpiak, 2014). Earlier work with a sample of 220 lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults age 50 and over demonstrated that social support, specifically from friends, was associated with less depression and less anxiety, but support from family did not have the same effect (Masini & Barrett, 2008). These findings shine a light on the ways in which sources of social support might be associated with positive health-related outcomes for LGBT older adults. However, much remains to be understood about who LGBT older adults identify as sources of support, the relationship between social resources and physical and mental health among LGBT seniors, and the factors that enhance their perceptions of social support.

A small but emerging area of inquiry has demonstrated positive effects of having a pet; however, this remains a contested hypothesis. Limited prior research suggests that the presence of a pet can improve an individual’s symptoms associated with a disability or chronic illness. Human–animal bonds appear to act in similar ways to more traditional social supports with improved outcomes documented in individuals with depression, AIDS, and dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Some studies show gender differences in attitudes toward and reasons for having animal companions. Women without children demonstrate greater levels of attachment to their companion animals and value their company, need for care, and entertainment (Herzog, 2007; Ramon, 2010); women were also more likely than men to report that they keep a companion animal to avoid loneliness and get them through hard times, though the differences between men and women were small (Staats, Wallace, & Anderson, 2008). By remaining nonjudgmental, providing an outlet for love and attachment, day-to-day comfort through their reliable presence, and imparting episode-specific support during times of heightened stress, it has been advanced that pets increase individuals’ perceived social support (Hutton, 2015; Siegel, Angulo, Detels, Wesch, & Mullen, 1999). Pets appear to make a unique contribution to helping fulfill their owners’ needs related to belongingness and meaningful existence, but this is independent of their level of human social support. In other words, pets seem to complement rather than substitute for human support (McConnell, Brown, Shoda, Stayton, & Martin, 2011). In a landmark study, Serpell (1991) showed that compared to a control group of people who did not adopt a pet, those who acquired a cat or dog showed subsequent improvement in exercise, health, and psychological well-being at 10-month follow-up.

For older adults, specifically, research examining the impacts of having a pet has produced inconsistent results. Antonacopoulos and Pychyl (2008) suggest that animals provide social support and companionship, thereby reducing participants’ experience of stress. Qualitative research with a sample (n = 12) of lesbian identified women 65 and over suggested that human–animal interaction supported specific aspects of psychological well-being including connection to others (Putney, 2014). Pet ownership has also been demonstrated to maintain or even elevate older adults’ capacities to perform activities of daily living (Raina, Waltner-Toews, Bonnett, Woodward, & Abernathy, 1999). Conversely, some research has not demonstrated physical or psychological benefits of having an animal among the elderly (Parslow, Jorm, Christensen, Rodgers, & Jacomb, 2005). For example, animals can pose hazards in the form of risk of falls and bone fractures for older adults (Pluijm et al., 2006). Additionally, among a convenience sample of community-dwelling older adults over 60 years old, pet ownership could not explain the variance is health status (Winefield, Black, & Chur-Hansen, 2008).

The following questions emerge as these findings are considered together. Specifically, given their experiences over the life course, among sexual and gender minorities in midlife and later life, does having a pet relate to perceived social support and social network size? Given the disproportionately high rate of disability among LGBT older adults, how does the presence of a pet impact the perceptions of social support among LGBT older adults with a disability as compared to those who do not have a disability? Finally, to understand how pets may influence perceptions of social support, how do LGBT midlife and older adults describe the meaning of pets in their lives?

Method

Participants

This study used qualitative and quantitative data from Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2017). In this study, the project investigators collaborated with 11 community organizations across the United States and surveyed 2,560 LGBT midlife and older adults aged 50 and older. The surveys asked questions about lifetime and current experiences, health, and well-being of LGBT older adults. Inclusion criteria were that participants were aged 50 or older, self-identified as LGBT, or engaged in sexual behavior or were in a romantic relationship with someone of the same sex or gender. For more in-depth information about the study design and methodology, see Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. (2013).

The qualitative interview data were collected in the Greater Los Angeles area in two time periods between 2011 and 2014. The total sample size for the qualitative analysis is 59 (N = 59). Trained researchers interviewed a subsample (n = 35) from the cross-sectional study in 2011–2012, Aging with Pride (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2011). Survey participants who indicated that they were willing to participate in future research were contacted by the research team via a mailed letter, and those who responded to the inquiry were screened for participation by phone via a short set of demographic questions and, during that phone call, interviews were scheduled for a later time. Inclusion criteria for interview participants were as outlined above as well as that participants live within a drivable radius (30 miles or less) of Los Angeles. Six months later, 24 additional interviews using the same set of interview questions were collected as a means of increasing the sample diversity. These second set of participants were recruited into the study through a mix of convenience and snowball sampling starting with an older lesbian community member who had worked with LGBT and HIV-related organizations in the region. This individual assisted with targeted recruitment to increase the diversity in the sample’s racial, socioeconomic, and sexual orientation representation. Additionally, the researchers sent fliers to other local organizations to recruit participants. As was the case with original participants, individuals who contacted the project were screened for participation by phone via a short set of demographic questions, and subsequently, interviews were scheduled. The inclusion criteria for the additional set of interviewees were the same as the first: age 50 and over, self-identify as LGBT, and live within a drivable radius. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards at the authors’ institutions.

Procedures

Qualitative data were collected in face-to-face interviews with LGBT adults, age 50 and older, at a time and location of their choice where privacy could be insured. Most interviews were conducted in their homes or at a local LGBT center that serves midlife and older adults. A few interviews were carried out in public locations such as shopping centers and cafes, in which cases, the researcher and interviewee sat in the location that provided the greatest level of privacy. Prior to beginning the interview, the participant reviewed and signed an informed consent form. At the end of the interview, participants were each paid US$25 as a token of appreciation for their time and participation in the study; the study and remuneration funds were supported by a federal grant from the National Institute on Aging, R01 AG026526 (Fredriksen-Goldsen, PI).

The interviews were between 45 and 90 min and were audio-recorded with the permission of the participant. Interviewers were experienced in working with these populations and trained in methods and techniques for effective interviewing of LGBT older adults. The semistructured interview began with the interviewer building rapport with the participant and asking questions intended to elicit conversation. The interview questions addressed a range of topics about health, aging, support networks, relationships, housing, important life events, experiences of discrimination, and caregiving. In some cases, the participant discussed their pet prior to being asked any specific questions about pets. One of the questions in the interview protocol directly asked participants whether they currently had a pet and if so, what was that pet’s role in their life. If the participant did not have a pet, we asked a follow-up question about why they did not have a pet. When the interviews were conducted in the participants’ home, the interviewer often saw pets, and then asked whether the participants had other pets. The interview protocol did not include questions about the role of pets throughout participants’ lives, but some participants offered that information.

Quantitative data were collected using a set of questions that determined whether an individual had a pet, social support, and health-related measures and demographic questions. The specific questions are detailed below.

Having a pet

An item, “Do you have a pet or pets?” was asked and participants were categorized into either having or not having pets.

Perceived social support

Perceived social support was measured by the abbreviated Social Support Instrument (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991) and used four questions to assess available social support. The social support measure assesses four dimensions of support including tangible, emotional–informational, positive social interaction, and affectionate, for example, “someone to love and make you feel wanted.” The participants rated each question from 1 (never) to 4 (always). A composite score was calculated, averaging across the 4 items with higher scores representing greater support (Cronbach’s α = .85).

Social network size

Social network size was determined by participants’ self-report of the number of people they typically interacted within a month. The total size of social network was computed into quartiles to handle skewed distributions and dichotomized into the lowest quartile (≤25%) versus higher quartiles.

Disability

We followed the recommendations in Healthy People 2020 (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2010) and defined disability by participants’ affirmative response to either of the two questions: “Are you limited in any way in any activities because of your physical, mental, or emotional problems?” or “Do you now have any health problem that requires you to use special equipment?”

Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics included age (ranged 50–95), biological sex (female vs. male), education (high school and below vs. some college and above), poverty (living at or below vs. above 200% of federal poverty level), and race and ethnicity (White, Hispanic, African American, and others).

Analytic Strategies

Qualitative data

Each of the interviews was transcribed verbatim and then reviewed for accuracy by the lead author. The authors coded Word documents where data that were relevant for a theme had been copied and pasted from the full interview transcript. The lead author initially coded the transcripts by examining the participant responses to questions about pets, “Do you have a pet and what is your pet’s role in your life?,” and by searching the rest of the interview transcript for mentions of pets. The first author conducted nearly all the interviews with participants and made some initial jottings about pets in notes after leaving the interview session. A trained undergraduate research assistant also reviewed the data transcripts to identify all instances where pets were discussed throughout the interviews.

The data were coded through the process of open coding (Charmaz, 2006; Saldana, 2016), where the material was reviewed repeatedly in order to identify common themes or concepts that emerged from the interviews. The lead author initially identified the codes using In Vivo coding, which focused on the language that participants used in their discussion of pets (Saldana, 2016). Such initial codes included participants’ description of pets as “kids” or “family” and differentiated participants who had pets but did not use this terminology. The data from participants without pets were also In Vivo coded according to their responses about why did not have a pet. The first author continued the In Vivo coding process by examining what role pets as kids or family played in participants’ lives, which is how the themes of kin, companion, and support developed. While there is overlap between these three themes in that kin provide companionship and support, companionship may be characterized as a form of support, and so on, the themes were differentiated according to the language used by participants. Thus, the codes were not a priori or initially derived from the prior research on human–pet interactions rather they emerged from the words spoken by the participants.

Quantitative data

The missing data rate for the pet question was 7.5%; therefore, the final sample size for this analysis was 2,364 as we employed complete-case analysis. Next, descriptive statistics were applied to examine study sample demographics and other variables of interest. Bivariate analyses were conducted to compare those with pet versus without subsamples regarding the selected factors. Finally, stratified, multivariable linear regressions were utilized to estimate the relationships between having a pet, social network size, and perceived social support in the context of disability. To further test the potential effects of having a pet, we also included an interaction term between having a pet and social network size. Model fit indices (Akaike Information Critierion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)) as well as likelihood ratio test were used to assist decision-making regarding whether the interaction term increased model fit. Huber–White robust estimator was applied to calculate the standard errors. All the statistical analyses were conducted in Stata 14 (StataCorp, 2015).

Results

Qualitative Findings

The qualitative findings from the study provide rich data that illustrate the role of pets in participants’ lives. Of the 59 qualitative interviewees, 35 currently reported that they have pets (59.32%); there was not a distinguishable pattern by gender, sexual orientation, or race related to having a pet. The demographic profile of the sample was 36 male and 23 female participants and by sexual orientation, 35 gay men, 18 lesbians, 4 bisexual (1 woman and 3 men), and 2 other (both men). None of the participants indicated that they were gender nonbinary, meaning that all participants identified as male or female. Three participants identified as transgender (two male and one female). Participants ranged in age from 54 to 88 with a mean of 68.16 years. Twenty participants were aged 50–64, 33 aged 65–79, and 6 aged 80+. By race, the sample was 41 White and 17 people of color (including 7 Black, 8 Latino, and 2 other), and 1 declined to state. Relationship statuses were 25 partnered or married, 33 single, and 1 other. Of the sample, only five individuals (three men and two women) had children. We have divided the participants into three income categories: 20 participants under US$20,000, 17 participants at US$21,000 to US$74,000, 16 participants at $75,000 and above, and 6 decline to state. In presenting the results, we have assigned pseudonyms to the participants to preserve confidentiality.

Participants with pets typically describe them in affectionate terms. In the following section, we address the primary ways in which the participants characterize the important role that pets play in their lives, which are that pets serve as kin, affect mental and physical health, and provide a sense of connection and love. Not all participants view their animal companions as having a central role in their lives, which we also address in the findings. We also address the self-reported reasons why some participants do not have pets.

Pets as kin

Participants often characterize their animal companions in familial terms. Patricia, a 77-year-old Black lesbian, who has a dog and a cat stated: “I also consider them my little family for right now, my biological family, nuclear family has died.” She continues, “the animals and my roommate comprise my little family.” Some participants characterize their pets as their children. For instance, Matthew, a 60-year-old partnered gay White man, described his and his partner’s two miniature dachshunds: “They’re just like our kids” and noted that the dogs have been an integral part of their life for the 31 years they’ve been together. Similarly, Letitia, a 72-year-old Latina lesbian who has been partnered with Miller for 37 years, noted of their two dogs, “They are like our children.” Some participants, however, expressed a different view. For example, Fred, a 78-year-old Black man, said, “They’re just dogs and cats. They’re not people. I’m not one of those people that they fulfill everything they’re not my children. They’re dogs and cats and I like them. If they die, they’re dead. I’ll bury them in the yard.”

Pets as support

Gladys, a 69-year-old White lesbian, characterized the role of her pets in her life: “Everything. They mean everything to me.” She further summarized how pets provide support:

The dog for me is God’s special gift to those of us who wouldn’t be able to survive on the planet without them. They get you through and if you have a particularly difficult life and you don’t have a dog you may not make it. It is the difference between making it and not making it, that’s what a dog is as far as I’m concerned that’s what I consider a dog to be, life-saving in every way.

Pets also contribute to social support by expanding participants’ human networks and keeping them active. Leslie, who is a 65-year-old White lesbian, stated,

I’ve met most of my friends through my dogs, actually. There was a large group of us that used to walk up in [a local] Park every Sunday morning and [my close friends] were part of that … I’ve met a lot of people through the dogs and it’s also, well, they’re good for getting you out again and, you know, exercise.

Many participants noted that they suffer from physical and mental health conditions and that their pets help them cope. Gabriel, a 69-year-old Latino gay man, has two cats and explained:

I adore them. They’re an incredible support system and we take care of each other. When I’ve had anxiety episodes, sad or cry, they are on me. They make sure that they’re right there. I couldn’t imagine walking into my environment and not having these guys there. I look forward to coming in. I talk to them like they were kids. I tell them when I’m coming back, or be a little longer. I apologize if I haven’t done something.

Alberto, a 58-year-old Latino gay man, who lives in a homeless shelter regularly visits his sister’s pets which: “[helps] me with my depression.” Cynthia, a 65-year-old White lesbian, said, “I’d be so depressed if I didn’t have a cat.” Some participants credit their pets with motivating them to stay alive. Ernest, who is a 59-year-old Black gay man with HIV disease and severe depression, explained how central a role his dog plays in his life:

If there hadn’t had been him, I would’ve had no reason to ever get out of bed, [for] many days, many weeks, but because he has to be walked twice a day, every day, that excuse is out the window. I have to get up and because I have to get up, I have to take medicine and because I have to take medicine, I have to eat. He’s been my lifeline the past three years.

Pets as companions

One of the most common interview responses was that pets are a source of companionship. Michael, a 67-year-old gay White man, explained: “My cat plays the role of someone who keeps me company a lot at home.” He noted further noted:

When I first became [HIV] positive, someone told me, why don’t you get a pet? So, I did, I always had a cat. This is the third one since then, so I think that plays an important role. Even when I was in a relationship just something to take care of; there is unconditional love from animals.

Rafael, a 72-year-old Latino gay man, characterized his three cats as “a source of love” and “companionship. [They’re] very sweet.” Kendra, a 58-year-old White bisexual woman, explained that her cats are “important to me because I live alone and they’re my companions.”

No pets

Many participants explained why they did not have pets. Frank, a 72-year-old White gay man, gave away his dog because

I was trying to train her with rope and she would run off and I’d end up with rope burns, or she would be so excited and she would walk around me and trip me or other people and I realized I was too old [to train a strong, young dog].

Others like Jack, a 63-year-old White man, explained that he “[doesn’t want to have to clean up after a dog. And I like, I live alone so I can do what I want when I want.” Several participants are renters who live in buildings that prohibit pets, which limits their ability to have a dog or cat. Marcia, who is a 52-year-old White transwoman, explained that she has a prescription for a service animal and has “wanted a dog for years” but has a troubled relationship with the owner of her building and neighbors and, therefore, “fears that the owner” would find a reason to evict her, even though she can have a pet legally.

Quantitative Findings

Table 1 summarizes the overall sample characteristics as well as the results of the bivariate analyses. Among the sample, 37% were female, 23.5% were people of color, 31% were at or below 200% of the federal poverty level, 8% had high school or less education, and 47% had a disability. Forty-four percent (43.9%, n = 1,039) of the participants had at least one pet. Compared to those without pets, participants with a pet were more likely to be younger, female, above 200% of the federal poverty level, and more likely to have a disability. Those with pets also had higher levels of social support.

Table 1.

Quantitative Data Demographic Characteristics and Bivariate Analysis.

| Background Characteristics | Total Sample | Pet(s) | No Pets | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2,364 | 1,039 | 1,326 | |

| % | 100.00 | 43.93 | 56.07 | |

| Demographic backgrounds | ||||

| Age (mean, SD) | 66.41 (9.10) | 64.56 (8.37) | 67.88 (9.37) | <.001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female (%) | 36.71 | 49.02 | 27.08 | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | .15 | |||

| White (%) | 86.50 | 88.29 | 85.11 | |

| Hispanic (%) | 3.53 | 3.68 | 5.02 | |

| Black (%) | 5.53 | 3.00 | 3.95 | |

| Others (%) | 4.43 | 5.03 | 5.93 | |

| 200% Federal poverty level (%) | ||||

| At or below | 30.66 | 28.30 | 32.57 | .03 |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less (%) | 7.54 | 7.54 | 8.40 | .45 |

| Psychosocial factors | ||||

| Perceived social support (mean, SD) | 3.08 (.79) | 3.19 (.76) | 2.99 (.80) | <.001 |

| Social network size | ||||

| Lowest quartile (%) | 24.32 | 24.45 | 24.21 | .90 |

| Health | ||||

| Disability | ||||

| Any disability (%) | 47.13 | 49.85 | 45.00 | .02 |

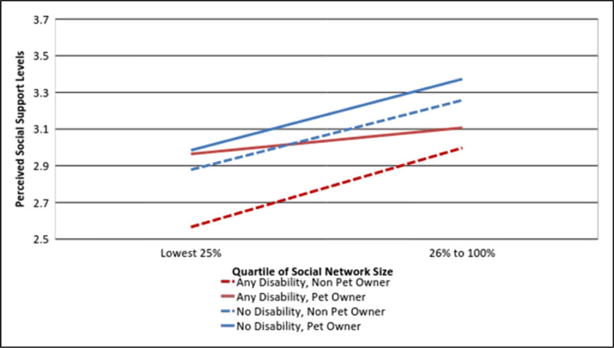

Table 2 presents the model fitting results for the stratified multivariable linear regression models. As summarized in Model 1, the results reveal that among LGBT older adults, both social network size and having a pet are independently associated with perceived social support, even after controlling for demographic characteristics and for both participants living with or without a disability. Compared to those with a larger social network size, having the smallest social network size (25% quartile) was associated with a .30 (SE = .06, p < .01) unit decrease in perceived social support for participants with a disability and a .38 (SE = .06, p < .01) unit decrease for participants without a disability. In contrast, compared with participants having no pets, having a pet was associated with a .19 (SE = .05, p < .01) unit increase in perceived social support for participants with a disability and a .11 (SE = .05, p < .05) unit increase for participants without a disability. However, as shown in Model 2, the interaction term between having a pet and social network size was significantly associated with perceived social support only among participants with a disability (β = .29, SE .11, p < .05). The model fit indices as well as the likelihood ratio test further suggested that the model fit significantly improved from Model 1 to Model 2 only for the subsample of LGBT midlife and older adults with a disability.

Table 2.

Quantitative Outcome: Social Support by Disability Status.

| Background Characteristics | Disability

|

No Disability

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1

|

Model 2

|

Model 1

|

Model 2

|

|

| β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | |

| Age | .007* (.003) | .007** (.003) | −.002 (.003) | −.002 (.003) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female (vs. male) | .20** (.05) | .20** (.05) | .17** (.06) | .17** (.05) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic (vs. White) | .06 (.13) | .07 (.13) | −.08 (.12) | −.08 (.12) |

| Black (vs. White) | .05 (.14) | .03 (.14) | −.27** (.10) | −.27** (.10) |

| Others (vs. White) | −.08 (.11) | −.10 (.11) | −.05 (.13) | −.05 (.13) |

| 200% Federal poverty level | ||||

| Above (vs. at or below) | −.30** (.05) | −.30** (.05) | −.27** (.06) | −.27** (.06) |

| Education | ||||

| > High school (vs. ≤ HS) | −.20* (.10) | −.20* (.10) | −.14 (.10) | −.14 (.10) |

| Social network size | ||||

| Lowest 25% (vs. 26–100%) | −.30** (.06) | −.43** (.08) | −.38** (.06) | −.38** (.07) |

| Pet | ||||

| Pet(s) (vs. no pet(s)) | .19** (.05) | .11† (.06) | .11* (.05) | .12* (.05) |

| Social Network Size × Pet | ||||

| Pet × Social Network Size | .29* (.11) | −.01 (.11) | ||

| Constant | 2.93** (.22) | 2.96** (.21) | 3.80** (.18) | 3.80** (.19) |

| AIC | 1,924.026 | 1,971.502 | 2,129.913 | 2,178.950 |

| BIC | 1,919.563 | 1,971.786 | 2,131.905 | 2,185.847 |

| Likelihood ratio test | χ2(1) = 6.46, p = .011 | χ2(1) = 0.01, p = .933 | ||

p< .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between having a pet, social network size, and perceived social support by disability group (those with vs. without a disability). As shown, LGBT older adults with a pet had higher perceived social support, regardless of their disability status, particularly when they had a larger social network size. However, for LGBT older adults with a disability and limited social network size, those with a pet had significantly higher perceived social support than did those without a pet.

Figure 1.

Having a pet by disability status and social network size and perceived social support.

Discussion

Both the qualitative and quantitative findings suggest that having a pet is beneficial to the LGBT older adults in our study, which is consistent with some of the past studies (Antonacopoulos & Pychyl, 2008; Putney, 2014; Raina et al., 1999). Some of the unique contributions of the study are that it expands our understanding of the lives of LGBT older adults and through the quantitative results, the role of pets in increasing their perceptions of social support. The qualitative results illustrate the ways in which the LGBT older adult participants experience their pets’ roles in their lives. In the remainder of this article, we address each of these contributions.

Through the lens of a life-course perspective, the study results illustrate how the aging process for these LGBT older adults has been shaped by the social contexts in which they have lived. For example, prohibitions on legal same-sex marriage and adoption over the course of current cohorts’ lives, in addition to the AIDS/HIV epidemic that killed and disabled many who were part of this cohort, may make pets especially meaningful forms of social support for LGBT older adults. Our qualitative findings illustrate that pets provide kinship and support in various ways. Two interviewees with HIV disease characterized their pets as a “life line” and “someone who keeps me company,” respectively. While HIV disease is not confined to LGBT populations, the historical context of HIV’s disproportionate effect on gay and bisexual men may particularly shape the importance of pets to our study participants. The qualitative results also show that having a pet, particularly a dog, can also help LGBT older adults remain physically active and engaged in their communities, which promotes mental and physical health.

The quantitative results show demographic differences within the sample: LGBT older adults who had a pet, compared to those who did not have a pet, were more likely to be younger, female, higher income, and living with a disability.

Women’s greater tendency to have pets may be related to prior research findings that show their greater desire for companionship, having someone to care for (Herzog, 2007; Ramon, 2010; Staats et al., 2008), and, as illustrated in the qualitative findings as well, to “get you through” hard times. Yet, existing studies caution the emphasis on gender differences with respect to attitudes toward or attachment to companion animals, since the effect sizes tend to be small and there is a great deal of overlap between men’s and women’s experiences (Herzog, 2007). Moreover, we do not know how conventional gender norms may be differently articulated and experienced within LGBT older adult samples.

As illustrated in both the quantitative and qualitative results, having a pet is not equally available for all LGBT older adults. The financial costs of pet care present a challenge to people living on a limited income or in poverty (Putney, 2014) or who rely on subsidized forms of housing that do not allow renters to have pets. Accordingly, the quantitative results show that those who have pets have higher incomes than those without the pets. Some older adults do not want to have a companion animal due to the inconvenience of having to care for a pet (Chur-Hansen, Winefield, & Beckwith, 2008). Mobility issues are also a consideration; for example, Frank noted that he needed to surrender his dog because he could not physically handle training him, and prior research notes that having a pet can increase the risk of falls (Pluijm et al., 2006). Thus, LGBT older adults’ decisions to have a pet are constrained by external factors.

The finding that younger participants of the study are more likely to have pets is consistent with prior research (Saunders, Parast, Babey, & Miles, 2017), though being younger was also correlated with being in better health. Having a pet may be particularly important for LGBT older adults, given their higher rates of depression, disability, and loneliness compared to heterosexual peers (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013; Wallace et al., 2011). Many LGBT older adults have different family and household structures than heterosexuals: Half of older gay men live alone, as compared to 13.4% of heterosexuals, and about 1/3 of older gay men are married or living with a partner, as compared to 3/4 of their heterosexual counterparts (Wallace et al., 2011). One quarter of older lesbians live alone, as compared to 1/5 of older heterosexual women, and about 1/2 of older lesbians are married or living with a partner, as compared to 2/3 of older heterosexual women (Wallace et al., 2011). According to the quantitative results, pets appear to make a unique contribution to helping fulfill their adopters’ needs related to belongingness and meaningful existence, but this is independent of their level of human social support. In other words, consistent with prior research findings, pets seem to complement rather than substitute for human support (McConnell et al., 2011). Given the differences in relationship status and household composition, however, having a pet may be more consequential for LGBT older adults in providing companionship, support, and affection when their networks are otherwise limited.

The study findings also illustrate the ways that some LGBT older adults exercise agency and build support by choosing to live with a pet. Many LGBT older adults have built and maintained the same-sex relationships, and some participants have partners and close friends to assist them if they need help. Yet, many of our study participants live alone, do not have children (or ongoing close relationships with them), and do not have partners; thus, many may turn to pets for companionship and affection. Some theoretical discussions of human–animal companionship characterize these bonds as “queering” family relationships, such that pets are substitute children (Haraway, 2003) and challenge expectations of heteronormativity in expressions of love (McKeithen, 2017). Nast (2006) notes, “Pets have in many ways become more salient as love objects in post-industrial contexts where fewer children are available” (p. 900), a characterization that is especially relevant for current cohorts of LGBT older adults. The qualitative finding that many of the LGBT older adults in our study compare their pets to children may represent a substitution of pets as a source and subject of love that were easier to acquire, given the structural constraints they encountered throughout their lives. Yet, while providing emotional support and companionship, they cannot assist with meal preparation, transportation to medical appointments, ensuring safety, and other types of tangible needs that emerge as people age, so LGBT older adults who rely upon pets for kinship ties may lack other types of instrumental support.

The findings also reveal that generally having a pet was independently associated with higher levels of perceived social support. However, having a pet also seemed to compensate for the negative effect of a smaller social network size on perceived levels of social support, particularly for LGBT older adults living with disability. When coupled with disability and limited social network, sexual minority adults with pets had higher perceived social support than those without pets.

One of the elements that is not clearly borne out in the quantitative findings is the role of pets for LGBT older adults in our sample who are partnered or married, as there were no statistically significant results related to relationship status. In the qualitative interviews, some coupled participants characterized their pets as children, which may reflect their shared affection and responsibility toward their animal companions. Because this finding was also evident for single participants, it is not clear, however, how being in a committed relationship may influence perceptions of pets. It is also not clear whether this finding is unique to LGBT older adults or whether it is also true of heterosexual older adults who are lifelong singles, do not have children, or are empty nesters. For example, though the total percentage has dropped over the past 25 years, an estimated 69% of older women live alone (Stepler, 2016); this population may benefit from the companionship of a pet. Future research is needed to address these issues.

Despite the findings that pets make positive contributions to the lives of LGBT older adults in our study, we must also consider the downside of pets being a source of social support. For participants who characterize their pets as companions, risks of this bond include the death of a pet or the need to surrender the pet to move into a facility or housing situation that disallows pets. Many people grieve the loss of the pet similarly to the death of a close family member and older adults who live alone may feel the loss intensely (Quackenbush, 1984; Turner, 2003); as such, it is important to consider the types of support older adults may need when faced with the death or loss of a pet.

Limitations

While our results point to the positive effect of having a pet for LGBT older adults, the study relies on cross-sectional data and it is impossible to discern the direction of the relationship between social support and having a pet. We know little about how pets contribute to mental and physical health over time, and this is an area for future inquiry in longitudinal studies of LGBT adults. Relatedly, though we use a life-course framework for this study, the interview protocol did not address the role of pets throughout participants’ lives; the focus was solely on the experience with pets at the time of the interview, which presents a limitation to the study. The results show that among LGBT adults in midlife and older who have a disability, having a pet likely compensates for the loss of social network size. This finding suggests the need to understand more about relationships with pets for more general populations over the life course, particularly those with disabilities.

The study does not also engage with the growing body of research that examines the relationship between stress, illness, and pets. Researchers have identified the effects of cumulative stress as “allostatic load,” which occurs when a person experiences recurrent “fight or flight” responses associated with stress (Seeman, Singer, Rowe, Horwitz, & McEwen, 1997). The effects of allostatic load among older adults include physical and cognitive decline, memory loss, diabetes, and cardiac disease (Seeman et al., 1997). Given that stress hormone levels seem to decrease when people interact with their dog (Odendaal, 2000), this can help explain how human–animal interactions may relate to physical and mental health outcomes. The cumulative effects of minority stress (Meyer, 2003) could expose LGBT adults to a risk for elevated allostatic load and associated adverse health consequences. Future research with LGBT adults can collect data through biomarkers that will shed light on whether pets attenuate stress and ultimately contribute to improved physical and mental health.

Another limitation is that the study focuses only on LGBT older adults and does not provide comparative data from heterosexual older adults; as a result, it is unclear whether the findings from this study are consistent across older adult populations. There is little research about the role of pets in the lives of older adults, and the existing studies provide contradictory conclusions. Given the projected growth of the population of older adults, the role of pets is an important area of research that could contribute to our knowledge of health, social support, and other aspects of aging. Moreover, since the present study shows that having a pet is associated with social resources and that pets are often considered family members, to gain a fuller understanding of this relationship and its effects, future research about older adults, particularly longitudinal studies, should include questions about having a pet, losing a pet, and constraints to having pets over time.

Conclusion

This study contributes to the gerontological literature by considering how different forms of social support, including nonhuman ones, affect aging for LGBT older adults and address the roles that pets play in their lives. The quantitative results provide evidence that pets can enhance the feelings of social support for those with disabilities and limited social networks, while the qualitative results illustrate how LGBT older adults experience their relationships with pets. While the findings are specific to the study populations, they have implications for older adults more broadly, particularly as we see the aging segments assume a larger proportion of our overall population over time.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01 AG026526 (Fredriksen-Goldsen, PI). Additional support for this work came from the Martin Duberman Fellowship from the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies and Loyola Marymount University to Anna Muraco and from the Hartford Foundation (Fredriksen-Goldsen, PI).

Biographies

Anna Muraco is an Associate Professor of Sociology at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles.

Jennifer Putney is an Assistant Professor of Social Work at Simmons College in Boston.

Chengshi Shiu works in the School of Social Work at the University of Washington.

Karen I. Fredriksen-Goldsen is a Professor and Director of Healthy Generations Hartford Center of Excellence in the School of Social Work at the University of Washington.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The lead author would like to thank the following individuals for their contributions to this research at its various stages: Hyun-Jun Kim, Freddy Puza, Nerissa Irizarry, Christopher Duke, Kira Jatoft, Paige Vaughn, Danielle Jaime, Jill Dannis, Aaliyah Jordan, Cole Cavanaugh, and Kenneth Cavanaugh.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- American Pet Products Association. 2013–2014 APPA national pet owners survey statistics: Pet ownership & annual expenses. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.americanpetproducts.org/press_industrytrends.asp.

- Antonacopoulos NMD, Pychyl T. An examination of the relations between social support, anthropomorphism and stress among dog owners. Anthrozoös. 2008;21:139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Bekele T, Rourke SB, Tucker R, Greene S, Sobota M, Koornstra J, Guenter D, The Positive Spaces Healthy Places Team Direct and indirect effects of perceived social support on health-related quality of life in persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2013;25:337–346. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.701716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan-Ing M, Seidel L, Larson B, Karpiak SE. Social care networks and older LGBT adults: Challenges for the future. Journal of Homosexuality. 2014;61:21–52. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2013.835235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll J, Roux A, Fitzpatrick A, Seeman T. Low social support is associated with shorter leukocyte telomere length in late life: Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) Psychosomatic Medicine. 2013;25 doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31828233bf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chur-Hansen A, Winefield H, Beckwith M. Reasons given by elderly men and women for not owning a pet, and the implications for clinical practice and research. Journal of Health Psychology. 2008;13:988–995. doi: 10.1177/1359105308097961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer D, Settersten RA. The study of the life course: Implications for social gerontology. In: Dannefer D, Phillipson C, editors. The Sage Handbook of Social Gerontology. California: Sage Press; 2010. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Emlet CA, Kim HJ, Muraco A, Erosheva EA, Goldsen J, Hoy-Ellis CP. The physical and mental health of lesbian, gay male, and bisexual (LGB) older adults: The role of key health indicators and risk and protective factors. The Gerontologist. 2013;53:664–675. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ. The science of conducting research with LGBT older adults-An introduction to aging with pride: National Health, Aging, Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS) The Gerontologist. 2017;57:S1–S14. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Emlet CA, Muraco A, Erosheva EA, Hoy-Ellis CP, Petry H. The aging and health report: Disparities and resilience among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. Seattle, WA: Institute for Multigenerational Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen K, Kim H, Shiu C, Goldsen J, Emlet CA. Successful aging among LGBT older adults: Physical and mental health-related quality of life by age group. The Gerontologist. 2015;55:154–168. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Muraco A. Aging and sexual orientation: A 25-year review of the literature. Research on Aging. 2010;32:372–413. doi: 10.1177/0164027509360355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack PL, Cohler BJ. Narrative, identity, and the politics of exclusion: Social change and the gay and lesbian life course. Sexuality Research & Social Policy. 2011;8:162–182. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway D. The companion species manifesto. Chicago, IL: Prickly Paradigm Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog HA. Gender differences in human-animal interactions: A review. Anthrozoös. 2007;20:7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog HA. The impact of pets on human health and psychological well-being: Fact, fiction or hypothesis. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2011;20:236–239. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton V. Social provisions of the human-animal relationship amongst 30 people living with HIV in Australia. Anthrozoös. 2015;28:199–214. doi: 10.1080/08927936.2015.11435397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understandin. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masini BE, Barrett HA. Social support as a predictor of psychological and physical well-being and lifestyle in lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults aged 50 and over. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2008;20:91–110. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell AR, Brown CM, Shoda TM, Stayton LE, Martin CE. Friends with benefits: On the positive consequences of pet ownership. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;101:1239–1252. doi: 10.1037/a0024506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeithen W. Queer ecologies of home: Heteronormativity, speciesism, and the strange intimacies of crazy cat ladies. Gender, Place & Culture. 2017;24:122–134. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraco A, Fredriksen-Goldsen K. “That’s what friends do”: Informal caregiving for chronically ill midlife and older lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships. 2011;28:1073–1092. doi: 10.1177/0265407511402419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraco A, Fredriksen-Goldsen KI. Turning points in the lives of lesbian and gay adults age 50 and over. Advances in Life Course Research. 2016;30:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.alcr.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nast HJ. Critical pet studies? Antipode. 2006;38:894–906. [Google Scholar]

- Odendaal JSJ. Animal-assisted therapy: Medicine or magic? Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2000;49:275–280. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An aging nation: The older population in the United States, Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2014. pp. 25–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Disparities. Healthy-People.gov. 2010 Retrieved July 13, 2017, from http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/disparitiesAbout.aspx#six.

- Parslow RA, Jorm AF, Christensen H, Rodgers B, Jacomb P. Pet ownership and health in older adults: Findings from a survey of 2,551 community-based Australians aged 60-64. Gerontology. 2005;51:40–47. doi: 10.1159/000081433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluijm SMF, Smit JH, Tromp EAM, Stel VS, Deeg DJH, Bouter LM, Lips P. A risk profile for identifying community-dwelling elderly with a high risk of recurrent falling: Results of a 3-year prospective study. Osteoporosis International. 2006;17:417–425. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney JM. Older lesbian adults’ psychological well-being: The significance of pets. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2014;26:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Quackenbush J. Social work in a veterinary hospital: Response to owner grief reactions. In: Kay WJ, Nieburg A, Hutscher AH, Grey RM, Carole E, editors. Pet loss and human bereavement. Ames: Iowa State University Press; 1984. pp. 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Raina P, Waltner-Toews D, Bonnett B, Woodward C, Abernathy T. Influence of companion animals on physical and psychological health of older people: An analysis of a one-year longitudinal study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1999;47:323–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramon ME. Companion animal knowledge, attachment and pet care and their association with demographics for residents in a rural Texas town. Preventative Veterinary Medicine. 2010;94:251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risley-Curtiss C, Holley LC, Cruickshank T, Porcelli J, Rhoads C, Bacchus DN, Murphy SB. “She Was Family”: Women of Color and Animal-Human Connections. Affilia. 2006;21(4):433–447. [Google Scholar]

- Saldana J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 3rd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J, Parast L, Babey SH, Miles JV. Exploring the differences between pet and non-pet owners: Implications for human-animal interaction research and policy. PLoS One. 2017;12:1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman T, Singer B, Rowe J, Horwitz R, McEwen BS. The price of adaptation: Allostatic load and its health consequences. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1997;157:2259–2268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpell J. Beneficial effects of pet ownership on some aspects of human health and behavior. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1991;84:717–720. doi: 10.1177/014107689108401208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel J, Angulo F, Detels R, Wesch J, Mullen A. AIDS diagnosis and depression in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study: The ameliorating impact of pet ownership. AIDS Care. 1999;11:157–170. doi: 10.1080/09540129948054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenberg C, Deeg D, van Tilberg T, Vink D, Stek M, Beekman A. Gender differences in the relation between depression and social support in later life. International Psychogeriatrics. 2013;25:61–70. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212001202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staats S, Wallace H, Anderson T. Reasons for companion animal guardianship (pet ownership) from two populations. Society & Animals. 2008;16:279–291. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata statistical software: Release 14. College Station, TX: Author; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stepler R. Smaller share of women age 65 and older are living alone. Pew Research Center Social and Demographic Trends. 2016 Retrieved Accessed July 13, 2017, from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2016/02/18/smaller-share-of-women-ages-65-and-older-are-living-alone/

- Turner WG. Bereavement counseling: Using a social work model for pet loss. Journal of Family Social Work. 2003;7:69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace SP, Cochran SD, Durazo EM, Ford CL. The health of aging lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in California. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston K. Families we choose: Lesbians, gays, kinship. New York: Columbia University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Winefield HR, Black A, Chur-Hansen A. Health effects of ownership and attachment to companion animals in an older population. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;15:303–310. doi: 10.1080/10705500802365532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]