Abstract

Objectives

The current research evaluated delivery modality and incentive as factors affecting recruitment into a personalized normative feedback (PNF) alcohol intervention for heavy drinking college students. We also evaluated whether these factors were differentially associated with participation based on relevance of the intervention (via participants’ drinking levels).

Method

College students aged 18–26 who endorsed at least one heavy drinking episode and one alcohol-related consequence in the past month (N = 2059; 59.1% female) were invited to participate in a PNF intervention study. In this 2 × 2 design, participants were randomized to: (1) complete the computer-based baseline survey and intervention procedure remotely (i.e., at a time and location of their convenience) or in-person in the laboratory, and (2) receive an incentive ($30) for their participation in the baseline/intervention procedure or no incentive.

Results

Consistent with hypotheses, students were more likely to participate when participation occurred remotely (OR = 1.87, p < .001) and when an incentive (OR = 1.64, p = .007) was provided. Moderation analyses suggested that incentives were only associated with higher recruitment rates among remote participants (OR = 2.10, p < .001), consistent with cognitive evaluation theory. Moreover, heavier drinkers were more likely to participate if doing so remotely, whereas drinking was not associated with likelihood of participation among in-person participants.

Discussion

The present results showed a strong selection bias for participation in a web-based intervention study relative to one in which participants were required to participate in-person. Results have implications for researchers recruiting college students for alcohol interventions.

Keywords: Alcohol, Drinking, College student, Brief intervention, Cognitive dissonance, Cognitive evaluation theory

1. Heavy drinking among college students

College student drinking is widespread and problematic. The Monitoring the Future study (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2012) reported that 60% of college students report having been drunk in the past year and 40% report having been drunk in the past 30 days. Additionally, more than a third of students report a heavy- drinking episode (4/5 or more drinks on one occasion for women/men) in the preceding fortnight. The negative consequences of heavy episodic drinking include poor class attendance, hangovers, engaging in risky sexual behavior, sexual assault, eating disorders, depression, trouble with authorities, injuries, and fatalities (Abbey, Clinton-Sherrod, McAuslan, Zawacki, & Buck, 2003; Dunn, Larimer, & Neighbors, 2002; Geisner, Larimer, & Neighbors, 2004; Hingson, Edwards, Heeren, & Rosenbloom, 2009; Kaysen, Neighbors, Martell, Fossos, & Larimer, 2006; Wechsler, Davenport, Dowdall, Moeykens, & Castillo, 1994; Wechsler, Kuo, Lee, & Dowdall, 2000).

2. Interventions for college student drinking

Many individually focused intervention strategies have been developed to reduce drinking among heavy drinking college students (Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & DeMartini, 2007; Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Elliott, Garey, & Carey, 2012; Cronce & Larimer, 2012; CollegeAIM: www.collegedrinkingprevention.gov/CollegeAIM). Among the interventions that are commonly studied, personalized normative feedback (PNF) interventions have emerged as highly effective (Neighbors, Dillard, Lewis, Bergstrom, & Neil, 2006). These interventions involve assessing a participant’s perceived drinking norms for an identifying group (e.g., fellow students at their university), then revealing what the actual norms are in conjunction with the participant’s own drinking behaviors.

Due to the increase in technology, a number of methods are emerging to deliver alcohol interventions online in locations of the participants’ choosing. To examine the efficacy of such interventions, several reviews and meta-analyses have been conducted (e.g., Bewick, Trusler, Mulhern, Barkham, & Hill, 2008; Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Elliott, Bolles, & Carey, 2009; Elliott, Carey, & Bolles, 2008; Rooke, Thorsteinsson, Karpin, Copeland, & Allsop, 2010), which show small but significant effects of computer-based interventions, depending on the content of the intervention and on the comparison group of the PNF.

3. Recruitment into intervention trials

3.1. Selection effects

Most alcohol intervention studies with college students have used similar recruitment strategies. This has the advantage of making findings comparable across studies. However, to the extent that recruitment strategies influence likelihood of participation, there may be systematic biases related to selection. Selection effects refer to systematic differences in respondent characteristics that may influence outcomes (Campbell & Stanley, 1963; Cook & Campbell, 1979; Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). Selection effects have a direct impact on external validity, because, in many cases, there are motivational factors associated with participating in a given study. For example, individuals who choose to participate in a study focused on alcohol are probably less likely to be abstainers. Studies often fail to take this into account, which means that many conclusions about drinking behaviors may be limited in their interpretability for the full range of human variability. While this may not be a problem for studies concerned with drinking motivations, it may be a problem for studies that aim to make conclusions about the population as a whole. Selection effects in which characteristics differ between groups in intervention studies threaten internal validity and create interpretation difficulties.

Typically, selection effects are not a problem for a given randomized trial, because random assignment ensures relatively similar characteristics among groups. In the larger literature, where recruitment efforts and/or delivery system lack variability, or variability is not empirically evaluated, selection effects have the potential to result in interpretation biases for an entire domain of studies. For example, most randomized trials for personalized feedback interventions utilize incentives. Without empirical examination of the potential effects of incentives, it is impossible to know what effects they might have on recruitment and/or intervention outcomes.

Similarly, feedback-based interventions have become increasingly administered remotely using web platforms. Much of the evidence providing initial support for feedback-based interventions was conducted in laboratory settings. Individuals who are only willing to participate in an intervention that does not require them to attend in-person or interact with lab personnel may be less motivated than those who are willing to participate in intervention studies that require in-person attendance. Thus, remotely delivered web-based intervention studies may be biased in recruiting less motivated individuals. This may account for some evidence suggesting that remotely delivered web-based personalized feedback appears to be significantly less effective than web-based personalized feedback that is delivered in a laboratory setting (Rodriguez et al., 2015).

Furthermore, individuals who are only willing to participate in intervention studies for which they are paid may be less intrinsically motivated than those who are willing to participate without payment. There is also a large body of evidence suggesting that individuals sometimes infer their motivation for engaging in a behavior to the receipt of payment (Lepper, Greene, & Nisbett, 1973). One meta-analysis demonstrated that monetary incentives doubled response rates for mailed surveys (Edwards et al., 2002). Another meta-analysis suggested small but significant effects for incentives increasing recruitment for web-based surveys (Göritz, 2010), which raises an important empirical question of whether incentives interact with delivery modality. We would expect the least motivated individuals to be most likely to participate in intervention studies which are remotely delivered by web and for which they receive payment.

3.2. Incentive effects

External factors, such as monetary incentives, are conducive for specific behaviors. Specifically, recruitment for intervention studies is often facilitated by compensation. However, widespread interventions intended to reach college populations often do not have the budgets required to compensate participants. In this way, the research community where studies are implemented is disconnected from the context in which the interventions will eventually be implemented. Previous research has found that incentives increase response rates for surveys (Brown et al., 2016; DeCamp & Manierre, 2016; Edwards et al., 2002; Göritz, 2010), but these results strictly apply to research studies. Empirical support for intervention strategies is often based on controlled studies which have recruited participants using monetary or other incentives. To the extent that incentives systematically influence recruitment in controlled trials, results may not generalize to real world settings where incentives are not feasible or desirable. Furthermore, if incentive effects turn out to also systematically influence efficacy of interventions in controlled trials, additional trials without incentives would be needed to provide confidence that interventions working in controlled trials will work similarly in the real world.

3.3. Delivery modality

Similarly, ease of participation is likely a major factor in increased recruitment numbers (Cunningham, 2009). That is, participants who can complete an intervention at their convenience online are more likely to participate than students recruited to attend in-lab intervention sessions. While one study has shown that web surveys tend to have lower rates of recruitment than in-person interviews (Lindhjem & Navrud, 2011), the in-person interviews for that study took place in the participants’ homes, unlike the current study. In-home interviews are likely much more convenient than in-lab interventions, given that the burden of travel is on the researcher instead of on the participant. Given this consideration, we expect in-lab recruitment rates to be lower than online recruitment rates. Additionally, most research on incentive effects and web-based interventions has used cross-sectional studies, and the degree to which these findings can be applied to more lasting research has yet to be explored (Göritz, 2010). And yet, motivating participation in longitudinal research is especially important in many web-based studies where follow-up data is crucial (e.g., most intervention studies).

According to cognitive evaluation theory (CET), extrinsic motivation will influence both the likelihood of participation and the effectiveness of the intervention (Deci, 1975; Deci & Ryan, 1985). CET was designed to explain the effects that extrinsic motivation might have on behavior. Brief interventions can be conducted remotely or in a lab setting. Again, likelihood of participation and effectiveness of the intervention may be affected by the location in which a participant receives their feedback. As such, we hypothesize that participants who are asked to come into the laboratory will be less likely to complete the baseline survey/feedback session.

3.4. Interest and relevance of participation

Limited research has examined how relevance effects participation in college alcohol interventions. In one study, students who reported more drinking also reported greater interest and actual participation in an intervention study (Neighbors, Palmer, & Larimer, 2004). This tendency was evident for all students with the exception of those who reported extremely high levels of alcohol. This is consistent with a broad range of motivational perspectives including the transtheoretical model, which suggests that individuals are unlikely to pursue change until they see the relevance and need for corrective behavior (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). It is also consistent with social cognitive models that emphasize the importance of motivation and confidence (i.e., self-efficacy; Bandura, 1997) in modifying health behaviors (Maisto, Carey, & Bradizza, 1999). In short, individuals who have few negative experiences with alcohol are unlikely to anticipate personal benefits from alcohol interventions and are expected to be less likely to participate.

3.5. Current research

The current study evaluated differences in recruitment into a brief PNF intervention based on the intervention delivery modality (remotely versus in-person) and the presence of an incentive (no compensation versus $30). We hypothesized that participants recruited for participation remotely would be more likely to complete the baseline and intervention procedure than those recruited to attend an in-person session (H1). Moreover, we hypothesized that participants recruited with a monetary incentive would be more likely to complete the procedure than those recruited with no incentive (H2). We were also interested in exploring the interaction between delivery modality and incentives in predicting baseline completion, although we had no specific hypotheses about this interaction. We further expected that relevance of the intervention (based on typical drinking level) would be associated with a higher likelihood of participation (H3a) and would moderate effects of delivery modality (H3b) and incentives (H3c), in that remote participation and incentives would have a stronger impact on participation among those who drank heavily.

4. Method

4.1. Participants

Participants included 2059 college students (59.1% female) between 18 and 26 years old (Mage = 22.14 years, SD = 2.27 years) who reported at least one episode of heavy drinking in the previous month (4/5 or more drinks on a single occasion for women/men) and at least one negative alcohol-related consequence in the previous month. Inclusion criteria were designed to identify students at risk for alcohol abuse without having to meet any diagnostic threshold. These inclusion criteria have been used in prior work to target heavy, risky drinking students (Marlatt et al., 1998; Murphy et al., 2004; Neighbors et al., 2004; Roberts, Neal, Kivlahan, Baer, & Marlatt, 2000). Based on the available data, the racial/ethnic distribution of this sample was as follows: 33.33% White, 17.13% Asian, 8.47% African American, 27.26% Hispanic, 3.81% Multiethnic, 7.55% International, and 2.46% other; 20.88% did not report their race/ethnicity.

4.2. Procedure

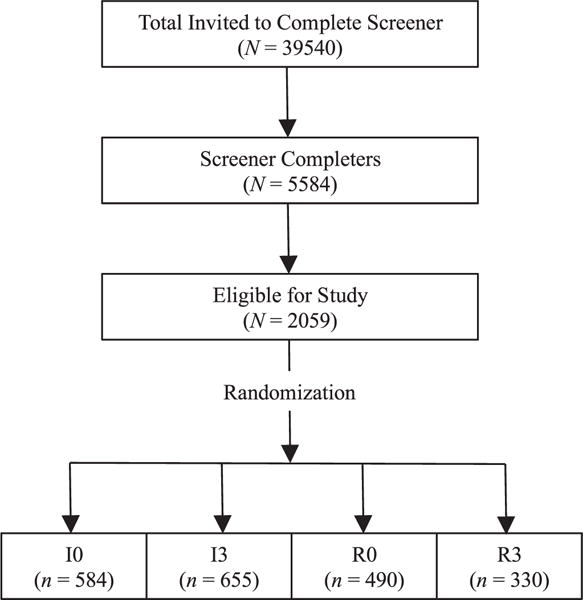

Participants were invited via email to complete a 20-min web-based screening survey to determine their eligibility for a study examining health behaviors among college students. The study was described as a longitudinal study about health behaviors among college students. It was not specifically described as an intervention study. Students were informed, however, that they might be randomly selected to view information about their drinking behavior and drinking among other college students. Upon completing the screening survey, participants deemed eligible to participate in the longitudinal study were randomized to a condition. The parent study from which these data were derived utilized a 2 (in-lab vs. remote baseline survey/intervention session) × 2 (incentive vs. no incentive) × 2 (personalized feedback on drinking vs. personalized feedback on electronic media (e.g., texting, video game) use) design. The present study sought to examine differences in treatment delivery and incentives regardless of feedback; thus, the present study employed a 2 (in-lab vs. remote baseline survey/intervention session) × 2 (incentive vs. no incentive) design. See Fig. 1 for participant recruitment.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram of recruitment into the intervention and randomization. Note: I0 = In-person, $0 Condition; I3 = In-person, $30 Condition; R0 = Remote, $0 Condition; R3 = Remote, $30 Condition.

At the end of the screening survey, participants were informed if they were randomized to an in-person or remote condition as well as to a compensated or not compensated condition. Participants were not informed about their feedback condition. Additionally, participants were not informed of the other conditions. For example, participants randomized to the no compensation condition were not informed that some participants would be compensated. Participants randomized to the in-person condition were directed to an online scheduler where they scheduled their in-person baseline assessment. Participants randomized to a remote condition were provided a link to the online baseline survey. Participants who did not either schedule their baseline appointment (i.e., in-lab participants) or complete their online baseline survey (i.e., remote participants) were emailed reminders and/or contacted by research staff. All participants provided informed consent prior to completing the baseline assessment. After completing the baseline assessment, participants were presented with their assigned intervention feedback and completed a brief post-intervention assessment. The entire baseline assessment and intervention session took approximately an hour to complete.

Following the completion of the baseline assessment and feedback, students were contacted three and six months later to complete follow-up surveys online remotely. Incentives for participation in the current study included $30 gift cards for the baseline and intervention session (for those who were randomized to the compensation condition), and $15 gift cards for 3- and 6-month follow-up surveys. To ensure all participants were offered the same compensation, participants randomized to a no-compensation condition received a $30 gift card after completing all aspects of the study; these participants were not informed that they would receive this compensation. The current study is based on screening and baseline data provided by participants who were deemed eligible for the longitudinal trial. The study protocol was approved by the University Institutional Review Board.

5. Measures

5.1. Demographics

Demographic data included gender (0 = male, 1 = female), age, and race/ethnicity. Collected demographic information was used to describe the sample.

5.2. Heavy episodic drinking

Consistent with extant work (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2015), heavy episodic drinking was measured with the question, “In the last one month, how many times have you had at least 4/5 [women/men] drinks in one sitting?” Response options included: 0 = none, 1 = 1 time in the past month, 2 = 2 times in the past month, 3 = 3 times in the past month, 4 = 4 times in the past month, and 5 = 5 or more times in the past month.

5.3. Alcohol-related consequences

Participants reported the number of times in the past month that they experienced 10 of the most commonly reported alcohol-related consequences (Neighbors et al., 2012). Response options included: 0 = no, not in the past month, 1 = 1 time in the past month, 2 = 2 times in the past month, 3 = 3 times in the past month, 4 = 4 times in the past month, and 5 = 5 or more times in the past month. Alcohol-related consequences were operationalized in terms of total number of consequences (Barnett et al., 2014; Lee, Geisner, Patrick, & Neighbors, 2010), calculated by summing the responses (α = 0.79).

6. Analysis plan

Given that our outcome is binary (i.e., no participation [0] vs. participation [1]), to evaluate hypotheses 1–3, logistic regression analyses were run using STATA 14. Dummy codes were created for both delivery modality (i.e., in-lab [0] vs. remote [1] participation) and incentive (i.e., $0 [0] vs. $30 [1]). The outcome utilized across all models was whether participants completed the baseline/feedback session or not (i.e., no participation [0] vs. participation [1]). Moderators included past-month drinking (i.e., number of heavy drinking episodes and total alcohol-related consequences experienced), which were grand mean centered.

After reporting recruitment rates across the four conditions, we examined main effects of delivery modality and incentive on likelihood of participation using logistic regression (Hypotheses 1 and 2). As an exploratory question, we then examined a model including the two-way interaction between delivery modality and incentive. If the interaction was significant, we followed up by evaluating whether the effect of incentive on participation was significant at remote and in-lab levels. To evaluate Hypothesis 3a (i.e., that heavier drinkers would be more likely to participate in the intervention overall), we included drinking in the past month (heavy drinking episodes and consequences) as a main effect in addition to conditions on participation. Hypotheses 3b and 3c tested past-month drinking as a moderator of the effects of delivery modality and incentive on participation. If significant, we followed up by examining how consequences were related to participation among those either in-lab or remote, or among those who received some or no compensation for participating. Finally, we explored the possibility of a three-way delivery × incentive × consequences interaction.

7. Results

7.1. Effects of delivery modality and incentive on participation

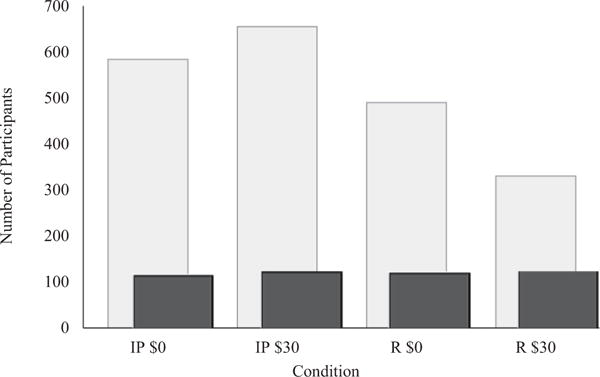

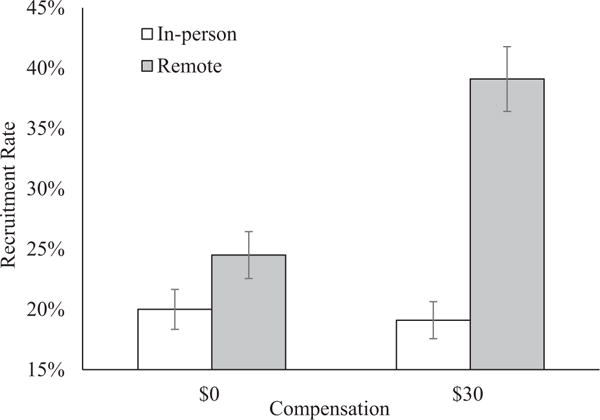

Four hundred and ninety one (23.85%) of the 2059 undergraduates recruited into baseline participated in the intervention. Fig. 2 illustrates the rates of number invited versus recruited for each of the four conditions. As expected, the number of invited participants to reach the recruitment goal was lowest for the remote, incentive condition (39.1% recruitment rate), followed by the remote, no-incentive condition (24.5%). The in-lab recruitment rates were lowest (19.7% for in-lab, incentive; 20.5% for in-lab, no-incentive). Our first two hypotheses were that invited students would be more likely to participate remotely compared with in-lab (H1) and that they would be more likely to participate if provided with an incentive compared with no incentive (H2). Table 1 presents how delivery modality and incentive affect the likelihood of participation in the intervention. Main effects were present for both delivery modality and incentive, suggesting that students were indeed more likely to participate when participation occurred remotely and when an incentive was offered.1 Further, we tested for an interactive effect of delivery modality and incentive. Indeed, a two-way interaction emerged, b = 0.743, p < .001, suggesting that the effect of incentive was differentially associated with the likelihood of participation based on delivery modality. This interaction is illustrated in Fig. 3. Results suggested that the presence of an incentive was only meaningfully associated with an increased likelihood of participation among participants invited to remote participation, b = 0.683, p < .001; for participants invited to participate in-lab, compensation was not associated with the likelihood of participation, b = −0.060, p = .674.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of invited (light gray) and recruited (dark gray) participants by condition (In-person [IP] vs. remote [R] and no incentive [$0] vs. incentive [$30]).

Table 1.

Main effects of and interaction between delivery modality and incentive on likelihood of participation.

| Step | Predictor | b | Z | p | LLCI | ULCI | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Intercept | −1.574 | −16.78 | < 0.001 | −1.758 | −1.390 | 0.207 |

| Delivery modality | 0.624 | 5.91 | < 0.001 | 0.417 | 0.832 | 1.867 | |

| Incentive | 0.287 | 2.72 | 0.007 | 0.080 | 0.494 | 1.638 | |

| 2 | Delivery modality × incentive | 0.743 | 3.53 | < 0.001 | 0.330 | 1.156 | 2.102 |

Note. OR = odds ratio. Delivery modality (0 = in-person, 1 = remote); compensation (0 = $0, 1 = $30).

Fig. 3.

Effect of compensation on likelihood of participation is moderated by delivery modality.

7.2. Drinking levels moderate effects of delivery modality and incentive

Our third research question surrounded whether recruitment would be higher among those for whom the intervention is more relevant (i.e., heavier drinkers; H3a) as well as whether the effects of incentive (H3b) and remote delivery (H3c) would be stronger among heavier drinkers. Thus, we evaluated drinking in the past month (i.e., number of heavy drinking episodes and total alcohol-related consequences experienced) on participation as well as a moderator of the effects of condition on participation.

On average, participants reported 2.47 (SD = 1.42) heavy drinking episodes (HDEs), and 5.54 (SD = 5.39) negative alcohol-related consequences in the previous month. HDEs were not associated with likelihood of participation (OR = 1.003, Z = 0.07, p = .941, 95% CI [0.934, 1.077]) when entered alone in the model, nor when included with delivery and incentive predictors (OR = 0.998, Z = −0.05, p = .964, 95% CI [0.929, 1.073]). We then examined all possible two-way interactions (i.e., delivery × incentive, delivery × HDE, incentive × HDE) on likelihood of participation; results are presented in Table 2. Neither interaction with HDE was significant, nor was the three-way interaction significant.

Table 2.

Interaction between delivery modality, compensation, and baseline drinking on likelihood of participation.

| Drinking variable | Step | Predictor | b | Z | p | LLCI | ULCI | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy drinking episodes (HDEs) | 1 | Intercept | −1.570 | −12.13 | < 0.001 | −1.823 | −1.316 | 0.208 |

| Delivery modality | 0.625 | 5.91 | < 0.001 | 0.417 | 0.832 | 1.867 | ||

| Incentive | 0.287 | 2.72 | 0.007 | 0.080 | 0.494 | 1.332 | ||

| HDEs | −0.002 | −0.05 | 0.964 | −0.074 | 0.070 | 0.998 | ||

| 2 | Delivery modality × incentive | 0.740 | 3.51 | < 0.001 | 0.327 | 1.153 | 2.096 | |

| Delivery modality × HDEs | −0.046 | −0.62 | 0.535 | −0.099 | 0.190 | 1.046 | ||

| Incentive × HDEs | 0.010 | 0.14 | 0.888 | −0.134 | 0.155 | 1.010 | ||

| 3 | Delivery modality × incentive × HDEs | −0.203 | −1.37 | 0.169 | −0.492 | 0.086 | 0.816 | |

| Alcohol-related consequences | 1 | Intercept | −1.652 | −15.46 | < 0.001 | −1.862 | −1.442 | 0.192 |

| Delivery modality | 0.624 | 5.90 | < 0.001 | 0.417 | 0.832 | 1.867 | ||

| Incentive | 0.280 | 2.65 | 0.008 | 0.073 | 0.488 | 1.324 | ||

| Consequences | 0.014 | 1.57 | 0.117 | −0.004 | 0.033 | 1.015 | ||

| 2 | Delivery modality × incentive | 0.726 | 3.43 | 0.001 | 0.312 | 1.140 | 2.067 | |

| Delivery modality × Consequences | 0.040 | 2.06 | 0.039 | 0.002 | 0.079 | 1.041 | ||

| Incentive × Consequences | 0.007 | 0.34 | 0.735 | −0.032 | 0.045 | 1.007 | ||

| 3 | Delivery modality × incentive × Consequences | −0.037 | −0.93 | 0.353 | −0.114 | 0.041 | 0.280 |

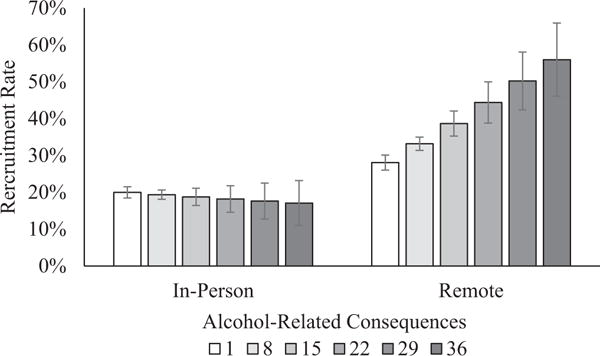

Results with the total number of alcohol-related consequences experienced showed that overall consequences were not significantly associated with likelihood of participation, neither when included alone in the model (OR = 1.015, Z = 1.67, p = .095, 95% CI [0.997, 1.034]), nor when included with delivery and incentive predictors (OR = 1.015, Z = 1.57, p = .117, 95% CI [0.996, 1.033]). In examining all possible interactions with condition, a significant interaction between delivery modality and consequences emerged, OR = 1.041, Z = 2.06, p = .039, 95% CI [1.002, 1.082]. This interaction, graphed in Fig. 4, suggests that among in-person participants, number of consequences experienced was not associated with the likelihood of participation. However, among remote participants, heavier drinkers were more likely to participate. The three-way delivery × incentive × consequences interaction was not significant.

Fig. 4.

Interaction between delivery modality and alcohol-related consequences on likelihood of participation.

8. Discussion

This research evaluates two potential sources of selection bias with significant implications for intervention studies with non-treatment-seeking participants: the impact of incentives and delivery method. Selection effects have been historically defined as cases in which experimental treatment groups include different kinds of people (Campbell & Stanley, 1963; Cook & Campbell, 1979; Shadish et al., 2002). The empirical database evaluating brief alcohol interventions in college populations consists largely of non-treatment-seeking students who receive incentives for participation: usually either money, gift cards, or course credit. If potential participants’ decisions to participate in intervention studies systematically vary as a function of receiving incentives, the results of studies in which all participants receive incentives cannot be assumed to generalize to conditions where incentives are not offered. This is important because intervention approaches supported in multiple randomized trials, which typically involve incentives for participation, are central criteria for classification as “empirically supported treatments” (Chambless & Hollon, 1998, 2012) or “empirically-supported interventions” (Chambless & Ollendick, 2001). A number of controversies regarding the sequela of classification and subsequent dissemination of empirically-supported interventions with “strong evidence” have been identified (Chambless & Hollon, 2012). While these issues include broad distinctions between efficacy studies conducted in controlled settings with high internal validity and effectiveness studies which are conducted in real-world settings, the specific issue of payment for participation has rarely been considered with respect to its potential implications on recruitment and/or attrition (Cleary, Walter, & Matheson, 2008).

In short, the effect of incentives of participation represents a selection effect, and findings from these studies cannot be logically assumed to have the same effects when disseminated broadly to campuses who administer the intervention but do not provide incentives. The main effect of incentives found in this study did support the hypothesis that potential participants were more likely to participate in an intervention study when monetary incentives were anticipated. The downside of this finding is that campus personnel considering their options regarding alcohol prevention and brief interventions, assuming they are looking for best practices, are likely to select approaches that have not been evaluated using the same kind of students they are likely to see. In essence, they are selecting approaches which have not been empirically evaluated using the kinds of students to whom they will administer them.

Fortunately, there is reason for optimism that approaches which have been supported using incentives may turn out to be more effective in the absence of incentives. According to self-perception theory, to the extent that students in intervention trials participate only to receive incentives, they place less value on the intervention itself. However, this optimistic speculation is unfortunately befouled by the results for delivery method on participation and the interaction between incentives and delivery method on participation.

The present results showed a strong selection bias for participation in a web-based intervention study Relative To One In Which Participants Were Required To Participate in-person. This effect supports some of the primary advantages which had been attributed to web-based interventions (e.g., Cunningham, 2009). Unfortunately, the relative efficacy of computer-delivered interventions administered remotely versus in-person has received limited empirical investigation. There is relatively clear evidence that interventions delivered in-person by a trained therapist are more efficacious than computer-delivered interventions (see Carey et al., 2012 for meta-analysis). This meta-analysis did not, however, distinguish between computer-delivered interventions that were administered in laboratory settings versus those that were delivered remotely. There is some evidence that computer-delivered interventions administered in-person to non-treatment-seeking heavy drinking students work relatively well, whereas computer-delivered interventions that are administered remotely may not work at all for the same population (Rodriguez et al., 2015). This is consistent with research showing that students participating in remotely-delivered web-based intervention studies are frequently engaged in multiple activities at the same time (e.g., watching television, checking email, talking or texting on phones; Lewis & Neighbors, 2015). The same study also demonstrated that the intervention effect in drinking reductions was only evident among participants who reported being attentive or not preoccupied while attending to the intervention. In short, it appears to be much easier to recruit participants for intervention studies in which they do not have to participate in-person. Unfortunately, these interventions may not work very well, especially if participants are not paying attention.

The interaction between delivery method and incentives may exacerbate concerns. The incentive effects were relatively strong in the remote condition. This suggests that participation was especially likely when potential respondents were offered payment to participate in a study requiring little effort on their part and one in which their activities during the procedure would not be monitored. In contrast, while there were fewer of them, individuals who were willing to participate in an intervention study that would require them to attend in-person were relatively unaffected by the presence or absence of monetary incentive. Thus, it is not only easier to recruit participants for intervention studies that are likely to be less effective, it is even easier to recruit them using monetary incentives. This sets up a potential theoretical and practical conundrum. Remotely delivered web-based interventions, with few exceptions, already appear to have very small, if any, effects on non-treatment seeking students. What might we expect when there are no external incentives for the same interventions?

Finally, we were interested in testing whether or not the relevance of the intervention might motivate students to participate. The number of heavy drinking episodes and number of alcohol problems experienced were used as proxies for relevance assuming that students who experience more problems would be more interested in learning ways they might reduce consequences. Neither variable alone was associated with likelihood of participation. There was, however, an interaction between number of alcohol problems and delivery method in predicting participations. In particular, differences in the recruitment rate for remote delivery versus in-person delivery were particularly evident among participants who reported more alcohol-related problems. While this finding does not completely eradicate some of the concerns raised above, to the extent that experiencing more alcohol problems is an indicator of relevance with respect to alcohol interventions, it raises hope for the potential effectiveness of remote interventions among students in greatest need of intervention. If students experiencing problems are interested in reducing problems, it would seem reasonable to expect that they would be most likely to pay attention during the remote intervention procedures, and as noted above, attentiveness appears to be a key factor in the efficacy of remote interventions for non-treatment seeking students.

9. Limitations and conclusions

The present study is limited to one public campus with a very diverse population and a relatively high proportion of students living off campus. Thus, it may not be representative of colleges in other regions with different characteristics. The $30 payment may not have been strong enough to motivate commuters to come in. In retrospect, a higher incentive (e.g., $50) might have been more effective. It is also worth noting that the target population was a heavy drinking sample. While this is consistent with most intervention studies in this population, the specific findings related to recruitment might differ in a general college sample. Beyond the basic demographic characteristics, we did not assess personality or motivational variables that might provide a more nuanced examination of factors contributing to participation. Despite these limitations, the present study offers unique contributions in considering selection effects in intervention studies.

In conclusion, results suggest that researchers and practitioners should be aware that the representative of samples in web-based interventions for non-treatment seekers depends on whether incentives are offered and perhaps by the perceived value of incentives as well as the number of problems they have experienced. No evidence was found to suggest that the same influences on recruitment for in-person interventions, although it seems clear that fewer people are willing to access intervention that requires in-person attendance. Additional work examining the effects of incentives, ease of access, and extent of alcohol problems on intervention efficacy will allow for more complete conclusions and suggestions regarding the influences of different motivational formats and structures.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Evaluated how incentives affect participation in a personalized normative feedback intervention

Evaluated delivery modality as a factor affecting recruitment

Recruitment rates differed as a function of both delivery modality and incentive.

Students were more likely to participate when remotely and with an incentive.

Incentives were only associated with higher recruitment among remote participants.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding sources

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R21AA022369. Work on this manuscript was supported, in part, by funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse through award F31DA043390-01. Neither NIAAA nor NIDA had a role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Ancillary analyses examined effects of delivery modality and incentive on participation after controlling for gender, age, and race/ethnicity. Results were unchanged and no covariates were significantly associated with participation. Interaction results below were also unchanged.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This research received approval from the University of Houston Institutional Review Board. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

All participants provided informed consent by indicating their agreement to participate after reading the informed consent document before beginning the study. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Additional informed consent was obtained from all individual participants for whom identifying information is included in this article.

Contributors

This research was funded by Author A and Author B’s NIAAA grant. Author A generated the idea for this in the specific aims of the grant and wrote the discussion. Author B ran analyses and wrote the results section. Authors C and D collaborated in writing the introduction, methods section. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

References

- Abbey A, Clinton-Sherrod AM, McAuslan P, Zawacki T, Buck PO. The relationship between the quality of alcohol consumed and the severity of sexual assaults committed by college men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18(7):813–833. doi: 10.1177/0886260503253301. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260503253301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY, US: W. H. Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Clerkin EM, Wood M, Monti PM, O’Leary Tevyaw T, Corriveau D, Kahler CW. Description and predictors of positive and negative alcohol-related consequences in the first year of college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75(1):103–114. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewick BM, Trusler K, Mulhern B, Barkham M, Hill AJ. The feasibility and effectiveness of a web-based personalised feedback and social norms alcohol intervention in UK university students: A randomised control trial. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(9):1192–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.05.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JA, Serrato CA, Hugh M, Kanter MH, Spritzer KL, Hays RD. Effect of a post-paid incentive on response to a web-based survey. Survey Practice. 2016;9(1) [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DT, Stanley JC. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP, DeMartini KS. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LA, Elliott JC, Bolles JR, Carey MP. Computer-delivered interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analysis. Addiction. 2009;104(11):1807–1819. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LA, Elliott JC, Garey L, Carey MP. Face-to-face versus computer-delivered alcohol interventions for college drinkers: A meta-analytic review, 1998 to 2010. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32(8):690–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2015. (HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH Series H-50). [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(1):7–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Treatment validity for intervention studies. APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology. 2012;2:529–552. [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52(1):685–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary M, Walter G, Matheson S. The challenge of optimising research participation: Paying participants in mental health settings. Acta neuropsychiatrica. 2008;20(6):286–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5215.2008.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis for field settings. Rand McNally; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Cronce JM, Larimer ME. Brief individual-focused alcohol interventions for college students. In: White HR, Rabiner DL, White HR, Rabiner DL, editors. College drinking and drug use. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 161–183. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA. Internet evidence-based treatments. Evidence-based addiction treatment. 2009:379–397. [Google Scholar]

- DeCamp W, Manierre MJ. “Money will solve the problem”: Testing the effectiveness of conditional incentives for online surveys. 2016;9(1) 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL. Intrinsic motivation. New York, NY, US: Plenum Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality. 1985;19(2):109–134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(85)90023-6. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EC, Larimer ME, Neighbors C. Alcohol and drug-related negative consequences in college students with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2002;32(2):171–178. doi: 10.1002/eat.10075. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/eat.10075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, DiGuiseppi C, Pratap S, Wentz R, Kwan I. Increasing response rates to postal questionnaires: Systematic review. BMJ [British Medical Journal] 2002;324(7347):1183–1185. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7347.1183. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7347.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott JC, Carey KB, Bolles JR. Computer-based interventions for college drinking: A qualitative review. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(8):994–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.03.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisner IM, Larimer ME, Neighbors C. The relationship among alcohol use, related problems, and symptoms of psychological distress: Gender as a moderator in a college sample. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(5):843–848. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göritz AS. Using lotteries, loyalty points, and other incentives to increase participant response and completion. In: Gosling SD, Johnson JA, Gosling SD, Johnson JA, editors. Advanced methods for conducting online behavioral research. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Edwards EM, Heeren T, Rosenbloom D. Age of drinking onset and injuries, motor vehicle crashes, and physical fights after drinking and when not drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33(5):783–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00896.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00896.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings. Vol. 2011. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Neighbors C, Martell J, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Incapacitated rape and alcohol use: A prospective analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(10):1820–1832. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Geisner IM, Patrick ME, Neighbors C. The social norms of alcohol-related negative consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(2):342–348. doi: 10.1037/a0018020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0018020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepper MP, Greene D, Nisbett RE. Undermining children’s intrinsic interest with extrinsic reward: A test of the “overjustification” hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1973;28(1):129–137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0035519. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. An examination of college student activities and attentiveness during a web-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2015;29(1):162–167. doi: 10.1037/adb0000003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/adb0000003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindhjem H, Navrud S. Are Internet surveys an alternative to face-to-face interviews in contingent valuation? Ecological Economics. 2011;70(9):1628–1637. [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey KB, Bradizza CM. Social learning theory. Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. 1999;2:106–163. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, Williams E. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a 2-year follow-up assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(4):604–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.604. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Benson TA, Vuchinich RE, Deskins MM, Eakin D, Flood AM, Torrealday O. A comparison of personalized feedback for college student drinkers delivered with and without a motivational interview. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(2):200–203. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.200. http://dx.doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2004.65.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Dillard AJ, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL, Neil TA. Normative misperceptions and temporal precedence of perceived norms and drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(2):290. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Atkins DC, Lewis MA, Kaysen D, Mittmann A, Larimer ME. A randomized controlled trial of event-specific prevention strategies for reducing problematic drinking associated with 21st birthday celebrations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(5):850–862. doi: 10.1037/a0029480. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0029480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Palmer RS, Larimer ME. Interest and participation in a college student alcohol intervention study as a function of typical drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(6):736–740. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.736. http://dx.doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2004.65.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist. 1992;47(9):1102. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LJ, Neal DJ, Kivlahan DR, Baer JS, Marlatt GA. Individual drinking changes following a brief intervention among college students: Clinical significance in an indicated preventive context. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(3):500–505. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.3.500. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LM, Neighbors C, Rinker DV, Lewis MA, Lazorwitz B, Gonzales RG, Larimer ME. Remote versus in-lab computer-delivered personalized normative feedback interventions for college student drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(3):455–463. doi: 10.1037/a0039030. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0039030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooke S, Thorsteinsson E, Karpin A, Copeland J, Allsop D. Computer-delivered interventions for alcohol and tobacco use: A meta-analysis. Addiction. 2010;105(8):1381–1390. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02975.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Statistical conclusion validity and internal validity. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. 2002:45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B, Castillo S. Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college: A national survey of students at 140 campuses. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;272(21):1672–1677. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.272.21.1672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Kuo M, Lee H, Dowdall GW. Environmental correlates of underage alcohol use and related problems of college students. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;19(1):24–29. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00163-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00163-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]