Abstract

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is the most common hemorrhagic stroke subtype, and rates are increasing with an aging population. Despite an increase in research and trials of therapies for ICH, mortality remains high and no interventional therapy has been demonstrated to improve outcomes. We review known mechanisms of injury, recent clinical trial results, and newly discovered signaling pathways involved in hematoma clearance. Enthusiasm remains high for methods of minimally invasive clot removal as well as pharmacologic strategies to improve recovery after ICH, both of which are currently being evaluated in clinical trials.

Keywords: intracerebral hemorrhage, thrombin, iron, brain edema, hypertension, hematoma

1. Background

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is the most common hemorrhagic stroke subtype, with an estimated annual incidence of 16 per 100,000 worldwide, and an incidence over double that in the developed world (Sacco et al., 2009). The incidence of asymptomatic, clinically silent ICH is even higher, estimated at over 2 million cases per year in the U.S. (Greenberg et al., 2009; Leary and Saver, 2003). Both short-term and long-term outcomes for symptomatic hemorrhages are poor, with 1-month survival estimated at 60% (van Asch et al., 2010), and 5-year survival estimated at 29% (Poon et al., 2014). Outcomes are even worse when ICH extends to involve the ventricular system (Hanley, 2009). The association of ICH with advanced age means the number of new cases will likely increase with an aging population (Lovelock et al., 2007; Qureshi et al., 2009).

Spontaneous, non-traumatic ICH can be due to an underlying lesion such as a tumor, vascular lesion, or angiopathy, though the majority of cases in the adult population are not attributable to an underlying lesion. Hypertension is the most common systemic risk factor, present in up to 70% of ICH patients and associated with increased morbidity and mortality in all age groups (Mendelow et al., 2005; Ruíz-Sandoval et al., 1999). An increasing number of cases are associated with use of anticoagulant or antiplatelet medications. Cases associated with vitamin K antagonists have increased hematoma volume, rates of expansion, and ventricular extension, all of which portend worse prognosis (Biffi et al., 2011; Cervera et al., 2012; Flaherty et al., 2008; Kuwashiro et al., 2010). Amyloid angiopathy is a significant etiology of bleeding in elderly patients, with certain apolipoprotein E alleles (e2, e4) leading to beta-amyloid deposition and weakening of the arterial walls (O'Donnell et al., 2000). Amyloid-associated ICH is more often in lobar areas of the brain, while hypertensive hemorrhages are more common in deep locations (Mehndiratta et al., 2012).

Most class I evidence for treatment of ICH is for supportive care, specifically care in a facility with neuroscience expertise, blood pressure control, and normalization of coagulation parameters or platelet counts (Hemphill et al., 2015). No interventional surgical or pharmacologic therapy has been shown effective in decreasing mortality or morbidity from ICH in trials in the U.S., though decompression of posterior fossa hemorrhage is widely accepted as decreasing mortality.

There has been a growing interest however in new therapies for ICH, both pharmacologic and interventional. This review examines injury mechanisms, results of recent trials for treatment and therapy, and new discoveries in the pathogenesis and repair after ICH.

2. Injury mechanisms

2.1. Primary brain injury

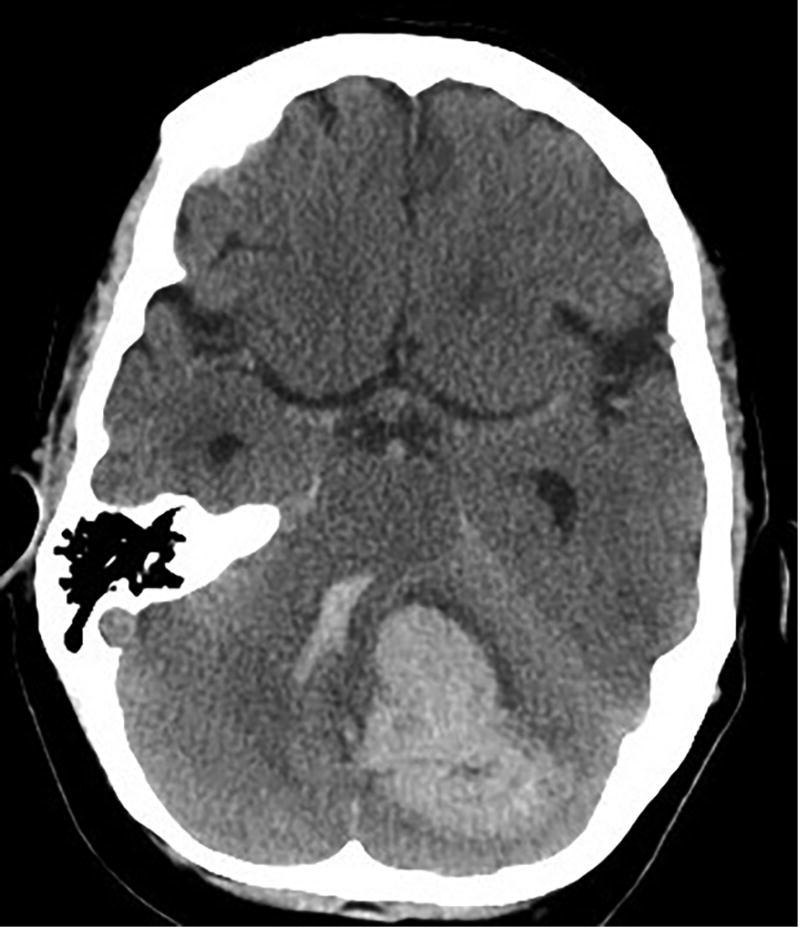

Mass effect and mechanical disruption from extravasated blood—either with initial hemorrhage or with continued hemorrhage and hematoma expansion—causes immediate primary brain injury due to both global increased pressure (increased intracranial pressure or ICP) and mechanical compression of local structures (Fig. 1). The latter can be particularly deadly when bleeds occur in the posterior fossa, where local compression of the aqueduct of Sylvius can lead to obstructive hydrocephalus, or local compression of the brainstem may lead to cardiorespiratory dysfunction. Hematoma expansion is common, and in one study was noted to occur in over one-third of patients in the first 24 hours after ictus (Brott et al., 1997). Evidence of a ‘spot sign’ on computerized tomography (CT) angiography is highly sensitive and specific for predicting hematoma expansion when noted within 3 hours of symptom onset (Wada et al., 2007).

Fig. 1.

Axial computerized tomography (CT) scan showing spontaneous cerebellar intracerebral hemorrhage with intraventricular extension causing compression of the 4th ventricle and brainstem.

Global increases in ICP may lead to herniation syndromes causing arterial compression and resulting ischemia. In non-herniation syndromes though, both animal and clinical studies suggest that the reduced perihematoma blood flow seen with ICH is not low enough to cause a local ischemic penumbra or core (Orakcioglu et al., 2005; Schellinger et al., 2003), and may be due to reduced metabolic demand in the surrounding tissue, as evidenced by stable or decreased oxygen extraction fractions (Herweh et al., 2007; Qureshi et al., 1999; Zazulia et al., 2001). Strategies for mitigation of primary brain injury generally involve measures to prevent hematoma expansion with blood pressure control or correction of coagulopathy, or to physically remove or lyse the clot (sometimes accompanied by cerebrospinal fluid diversion), either through open surgical or minimally invasive approaches. It should be noted, however, that the benefit of surgical removal has, so far, not been proven in clinical trials in the U.S. (see below).

2.2. Secondary brain injury

Secondary brain injury is caused by the physiologic response to the hematoma (primarily edema and inflammation) as well as the toxic biochemical and metabolic effects of clot components. Strategies for prevention of secondary brain injury include not only clot removal but also pharmacologic strategies.

2.2.1. Edema

The formation of perihematomal edema can occur within hours of ICH and persist for days to weeks (Zazulia et al., 1999), with an average 75% increase in perihematomal edema within the first 24 hours after ICH (Gebel et al., 2002). A portion of edema develops due to clot retraction and serum protein accumulation around the clot with an initially intact blood-brain barrier (Wagner et al., 1996). Thrombin, an activated component of the final common pathway in the coagulation cascade that plays a prominent role in hemostasis after ICH, also plays a role in disruption of endothelial cells and the blood-brain barrier. Thrombin is implicated in the formation of vasogenic edema in experimental models (Lee et al., 1997), and its inhibition has been proposed as a way to reduce perihematomal edema after adequate hemostasis of the clot (Hamada and Matsuoka, 2000). Additionally, erythrocyte components, including hemoglobin and its degradation products (heme and iron), as well as carbonic anhydrase have been shown to contribute to brain edema in experimental models (Guo et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2002). Edema likely contributes to disruptions in cell wall ion processing, including that of K+, Cl−, and Na+, though these disruptions may persist despite resolution of edema (Patel et al., 1999).

2.2.2. Inflammation

Previous studies have described the role of inflammation in both injury and recovery from ICH (Wang, 2010). Inflammatory responses both in the local perihematomal area as well as systemically are noted after experimental ICH (Illanes et al., 2011; Xue and Del Bigio, 2000), and both can have deleterious effects. Locally, diapadesis of neutrophils occurs within days and subsequently, microglia are activated. Their inhibition reduces brain damage in animal models (Wang et al., 2003). Experimental models have shown this brain inflammation is not restricted to the local area, as a receptor highly specific for leukocytes, intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), has been noted in the contralateral hemisphere after experimental ICH (Gong et al., 2000). Aside from inflammatory cells themselves, other inflammatory mediators are upregulated with ICH, including tumor necrosis factor, adhesion molecules, and matrix metalloproteinases, and they appear to be involved in inflammation-related local brain injury (Hua et al., 2006; Ma et al., 2011; Masada et al., 2001). Hematoma size is predictive of the degree of systemic inflammatory modulation, and animals with larger hematomas are more prone to infection (Illanes et al., 2011). Clinically, systemic infection rates are high with ICH, with 31% of patients in one study having an infection following hemorrhage (Lord et al., 2014).

2.2.3. Blood product toxicity

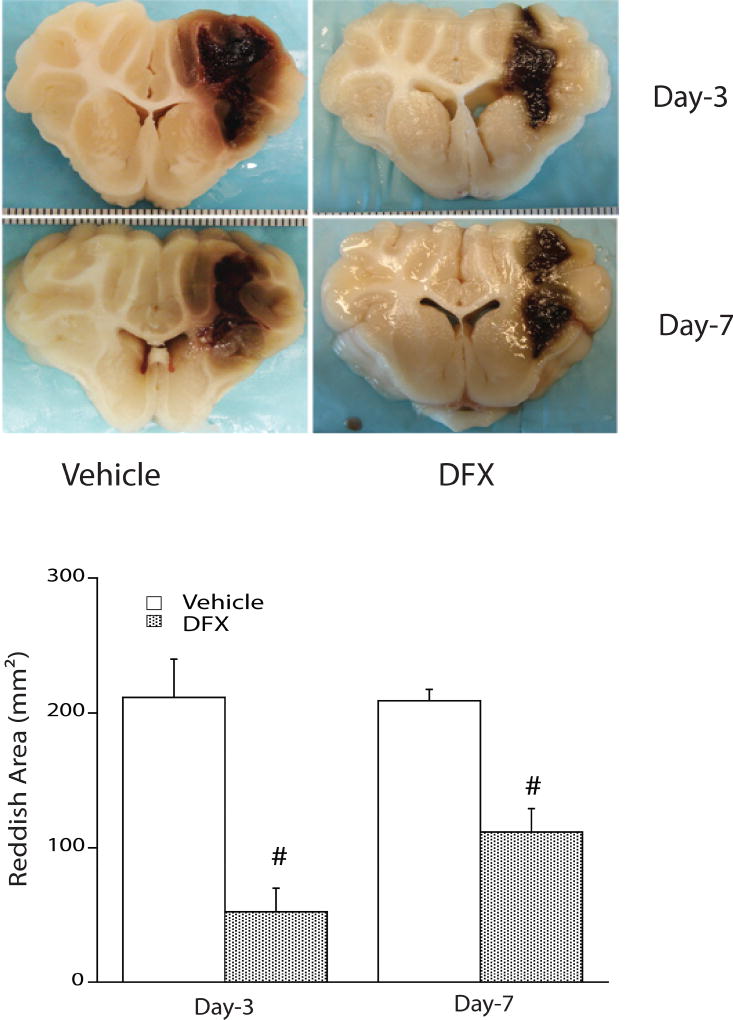

The toxic effects of hemoglobin, iron, and other blood components on surrounding brain are thought to be another driver of secondary brain injury. The injection of lysed blood cells in an experimental ICH model caused marked edema, an effect not found acutely with injection of packed erythrocytes (Xi et al., 1998), suggesting the lysed products themselves are primary contributors to brain injury. Hemoglobin plays a role in injury, as it inhibits the sodium-potassium pump and can cause neuronal depolarization and neuronal cell death in experimental models (Regan and Panter, 1993; Sadrzadeh et al., 1987; Yang et al., 1994). Iron is also implicated in ICH, and its chelation with deferoxamine reduced brain injury in animal models (Gu et al., 2009; Okauchi et al., 2010) (Fig. 2). The efficacy of iron chelation in patients is being studied in a clinical trial (Selim et al., 2011; Yeatts et al., 2013) (NCT02175225). Free-radical generation is one means by which iron may contribute to brain injury (Chen et al., 2011; Nakamura et al., 2005), though other sources also generate free radicals (Tang et al., 2005). Targeting free radicals with scavengers has been shown to reduce ICH-associated injury in experimental models (Hanley and Syed, 2007; Nakamura et al., 2008).

Fig. 2.

Deferoxamine (DFX) reduces reddish zone around hematoma at days 3 and 7 in a piglet autologous blood injection intracerebral hemorrhage model. Values are mean ± standard deviation, n = 4, cross-hatch (#) denotes p < 0.01 vs. vehicle. Reproduced with permission of Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. (Gu et al., 2009).

3. Therapeutic options—Results of recent clinical trials

An increase in the number of both preclinical and clinical studies over the past 2 decades have culminated in an increasing number of recently completed and ongoing trials (Keep et al., 2012). To summarize significant trial results from the past 4 years, a review of all clinical trials from clinicaltrials.gov was performed using the following terms: ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage, IPH, intraparanchymal hemorrhage, intracranial hemorrhage, IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage. All studies with results posted from 2013–2017 are contained in Table 1 and are summarized below.

Table 1.

Clinical trials in intracerebral hemorrhage completed since 2013

| Year | Investigator | Acronym | Intervention | Target | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | Mendelow (Mendelow et al., 2013) | STICH II | Open surgery | Multiple | No benefit |

| 2013 | Anderson (Anderson et al., 2013) | INTERACT2 | Blood pressure medications | Blood pressure, hematoma expansion | No benefit |

| 2013 | Butcher (Butcher et al., 2013) | ICH-ADAPT | Blood pressure medications | Cerebral blood flow, edema | No benefit |

| 2016 | Baharoglue (Baharoglu et al., 2016b) | PATCH | Platelets | Hematoma expansion | Worse outcome |

| 2016 | Qureshi (Qureshi et al., 2016) | ATACH-2 | Blood pressure medications | Blood pressure, hematoma expansion | No benefit |

| 2016 | Hanley (Hanley et al., 2016) | MISTIE-2 | Minimally invasive evacuation with tPA | Multiple | Safety, underpowered to determine benefit |

| 2016 | Vespa (Vespa et al., 2016) | ICES | Minimally invasive evacuation | Multiple | Safety, underpowered to determine benefit |

| 2017 | Hanley (Hanley et al., 2017) | CLEAR III | Intraventricular tPA | Multiple | No benefit |

| 2017 | Gladstone (NCT01359202) | SPOTLIGHT | Factor VIIa guided by “spot sign” | Hematoma expansion | No benefit (preliminary, unpublished) |

| 2017 | Flaherty (NCT00810888) | STOP-IT | Factor VIIa guided by “spot sign” | Hematoma expansion | No benefit (preliminary, unpublished) |

3.1. Blood pressure control

Three recently completed trials examined the safety and efficacy of rapid lowering of blood pressure after ICH. ICH-ADAPT examined the effect of tight blood pressure control (SBP <150) versus a higher threshold (SBP <180), finding no difference in the effect on perihematoma cerebral blood flow (Butcher et al., 2013), though it should be noted these were primarily small to mid-size hematomas, having an overall average volume of just over 25 cm3. The finding of a lack of association between rapid lowering of blood pressure and ischemia established the safety (at least in the short term) of aggressive treatment of blood pressure, an issue being examined by larger trials already underway comparing aggressive versus less stringent control of blood pressure. The INTERACT2 trial examined the effect of intensive blood pressure control (<140 systolic) within 6 hours after ictus in patients presenting with elevated systolic pressure (>180 systolic). Although barely not reaching significance in finding a difference in the primary outcome of death or disability between intensive and less strict blood pressure control, the trial did show a modest increase in functional outcome on ordinal analysis of modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores (Anderson et al., 2013). INTERACT2 and the earlier ICH-ADAPT study contributed the basis for the current guideline recommendations concerning blood pressure, namely that acute lowering to SBP <140 is safe (class I, level A) and may be effective for improving functional outcome (Hemphill et al., 2015). The ATACH-2 trial, however, did not support the conclusion that acute blood pressure lowering improved outcomes. It examined rapid (<4.5 hours), intensive blood pressure control (<140 systolic) in patients presenting with ICH and found no difference in death or disability compared with the standard treatment group (SBP <180). It also found a higher rate of adverse renal events seen in the intensive blood pressure control group (Qureshi et al., 2016). Despite two trials showing no significant benefit to the primary outcome of acute blood pressure lowering, the possibility of a mixed benefit/harm effect is possible, such that hematoma expansion is reduced but there can be simultaneous hypoperfusion causing local ischemia in some patients (Butcher and Selim, 2016). Additional trials are ongoing that use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess for local ischemic changes with intensive blood pressure lowering (Gioia et al., 2017).

3.2. Therapy for ICH associated with antiplatelet agents

Current recommendations are to transfuse platelets for ICH with severe thrombocytopenia, but the utility of transfused platelets in patients with a history of antiplatelet agent use is uncertain. The PATCH study showed new findings however, demonstrating that patients taking antiplatelet therapy for at least 1 week prior to ICH did worse when randomized to early platelet transfusion after diagnosis of ICH compared to those managed without platelet transfusion. Its applicability to patients taking all antiplatelet agents is limited however, as over 70% of enrolled patients were taking only aspirin, with less than 20% taking dipyridamole and less than 5% using more potent adenosine phosphate (ADP) inhibitors (Baharoglu et al., 2016a).

3.3. Open surgery

Following the original STICH trial, which found no benefit to evacuation of supratentorial hematomas but a suggestion of differences in outcome when stratified by deep bleeds or those with intraventricular extension (Mendelow et al., 2005), the STICH II trial compared conscious patients with superficial supratentorial hematomas without intraventricular hemorrhage who were randomized to early open surgical hematoma evacuation versus medical management, finding no significant difference in the primary outcome of death or disability (Mendelow et al., 2013). There was a trend towards a clinically significant survival benefit with surgery, and 21% of patients in the initial conservative treatment arm did go on to receive surgery. The current class I guidelines recommend surgery only for infratentorial hemorrhage, while stating that for most patients with supratentorial hemorrhage, the usefulness of surgery is unestablished (Hemphill et al., 2015).

3.4. Minimally invasive thrombolysis and clot removal

More recent trials have focused on minimally invasive efforts at thrombolysis, clot removal, or both. The MISTIE phase II trial, a small study designed to demonstrate safety and that minimally invasive removal with thrombolysis reduces ICH, showed equivalent outcomes between patients randomly allocated to minimally invasive surgery with alteplase thrombolysis compared with those randomized to best medical management. Asymptomatic bleeding was higher in the minimally invasive surgery plus alteplase group (Hanley et al., 2016), and a phase 3 trial is ongoing (NCT01827046). In a related study, stereotactic CT-guided endoscopic removal of hematoma without alteplase was safe and effective in a small number of patients, with a trend towards improvement in neurologic outcome (Vespa et al., 2016). Minimally invasive clot removal using a distinct endoscopic system (MISPACE) is being studied and compared with medical management, with a phase I study showing a high rate of clot removal with minimal adverse events (Labib et al., 2017), and an ongoing trial comparing with medical management (NCT02880878). Some minimally invasive strategies are already used extensively in Asia (Zhou et al., 2012). Two large clinical trials in Asia restricted to a small subset of ICH patients showed promise. A large, multicenter Chinese trial demonstrated improved functional outcomes after minimally invasive removal of a narrow group of moderately sized basal ganglia ICH (Wang et al., 2009). A second from Korea likewise found better 1-month and 3-month mRS scores after minimally invasive treatment of basal ganglia ICH with size >30cm3 compared to medical management (Kim and Kim, 2009). Additional trials in the U.S. are ongoing (NCT02654015).

Examining just the subgroup of ICH with intraventricular extension, the CLEAR III trial compared intraventricular injection of alteplase versus saline control in patients presenting with non-severe intraventricular hemorrhage and obstructive hydrocephalus, finding no difference in the primary outcome of death or disability. Mortality was higher in the saline (control) injection group, however this was tempered by a higher proportion of mRS 5 outcomes in the control group, indicating a shift from “death” to severe disability. Alteplase injection did not result in a higher rate of symptomatic bleeding (Hanley et al., 2017).

4. New pre-clinical discoveries in pathologic mechanisms of ICH

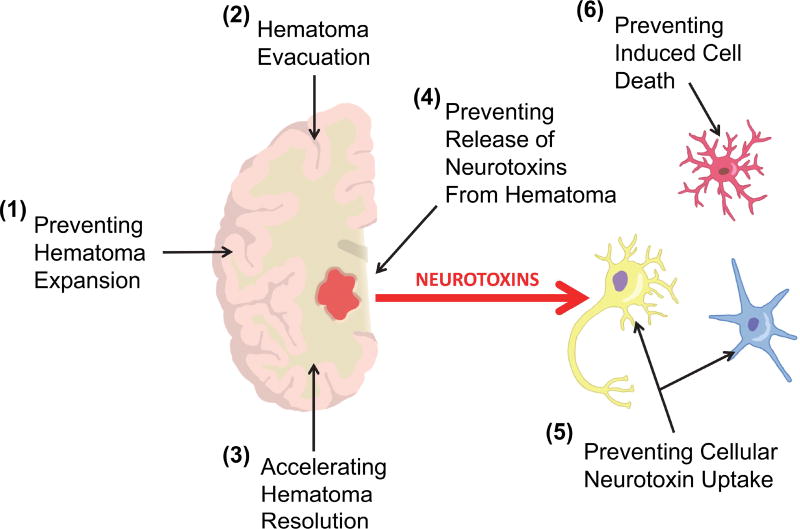

Pre-clinical studies have recently improved our understanding of the molecular basis of damage and repair in ICH and are increasingly being used to inform clinical trials (Keep et al., 2012). In this section we focus on some recent findings and particularly a developing concept that the hematoma may be a pharmacological target as well as more conventional targeting of the perihematomal tissue to induce neuroprotection. An overall schematic suggesting potential treatment modalities is outlined in Figure 3.

Fig. 3.

A schematic of potential methods for reducing the harmful effects of clot-derived neurotoxins in intracerebral hemorrhage. The hematoma contains constituents (e.g., hemoglobin and iron) that can damage perihematomal neural cells directly or indirectly (e.g., by inducing neuroinflammation) – red arrow. These damaging effects might be reduced by several approaches: (1) preventing hematoma expansion after ictus (limiting the size of the hemorrhage), (2) evacuating the hematoma (although as yet there is no definitive evidence for surgical evacuation), (3) accelerating hematoma resolution (e.g., using PPARγ agonists, CD47 blockade), (4) preventing the release of the neurotoxins from the hematoma (e.g., by promoting phagocytosis of erythrocytes over red blood cell lysis, detoxifying neurotoxin while within the hematoma), (5) preventing the uptake of the neurotoxin into perihematomal cells (e.g., potentially CD163 inhibition), (6) preventing cellular toxicity (depends on the individual neurotoxin but includes inhibiting cell injury pathways, ‘neuroprotection’, and inducing protective pathways in the cell).

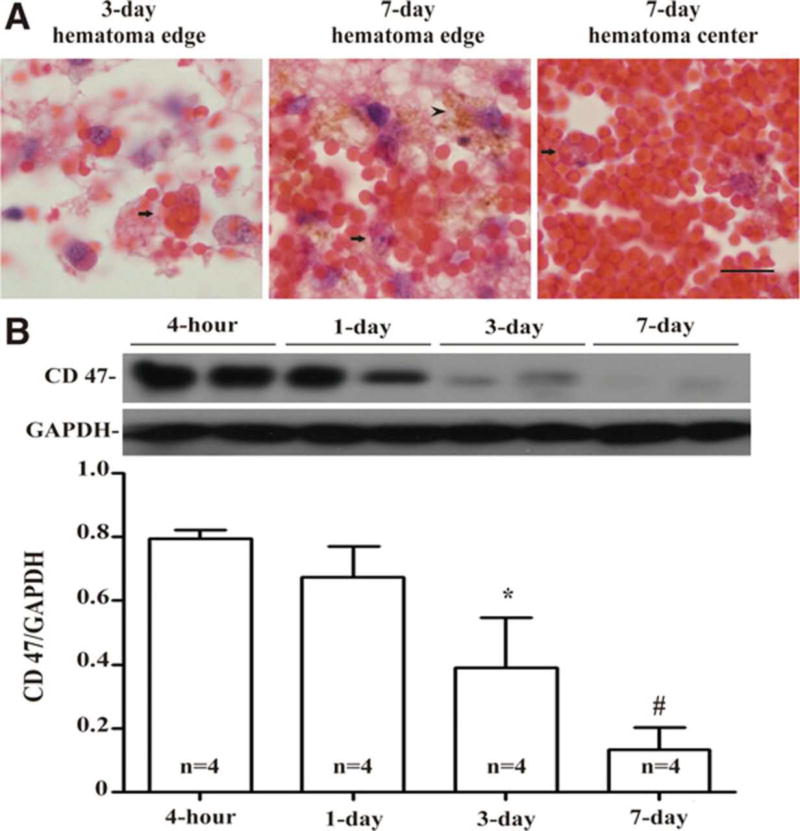

That hematoma resolution could be a pharmacological target was first suggested by the pioneering work of Zhao, Aronowski and colleagues, who found that peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ agonists could enhance the rate of resolution (Zhao et al., 2009). This has led to the current clinical trial of pioglitazone in ICH (Gonzales et al., 2013) (NCT00827892). Recent preclinical studies have also given insight on the regulation of hematoma phagocytosis. Cluster of differentiation 47 (CD47), an integrin-associated protein expressed on erythrocytes, plays a key role as a “don’t eat me” signal and decreases with time in the hematoma (Fig. 4) (Cao et al., 2016). Its absence may result in more expression of pro-clearance M2 differentiated microglia/macrophages, with an ultimate result of faster clot resolution, with less brain swelling and less neurologic deficits in mice (Ni et al., 2016). Inhibition of CD47 is already under investigation in clinical trials to enhance phagocytosis in advanced cancers (NCT02367196) (Willingham et al., 2012) and is a candidate for future study as a therapy for ICH.

Fig. 4.

(A) Erythrophagocytosis (arrows) at days 3 and 7 in a piglet autologous blood injection model of intracerebral hemorrhage, with hemosiderin deposition (arrowhead) noted at day 7. Scale bar, 10 µm. (B) Time course of CD47 levels in the hematoma. Values are mean ± standard deviation, asterisk (*) and cross-hatch (#) denote p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively, vs. 4-h. Reproduced with permission of Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. (Cao et al., 2016).

If erythrocytes within the hematoma are not phagocytosed, they may undergo lysis releasing potentially harmful hemoglobin and iron into the extracellular space. Cluster of differentiation 163 (CD163) is a known hemoglobin receptor involved in clearance of hemoglobin through microglia and differentiated macrophages, primarily through the CD163-heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) pathway. CD163 was long known as a receptor mediating the intracellular uptake of hemoglobin into macrophages (Madsen et al., 2001). Recent studies have shown that CD163 is also expressed and involved in blood product clearance not only in glia, but also in neurons where it is upregulated in ICH (Chen-Roetling and Regan, 2016; Liu et al., 2017). The involvement of neurons themselves in hemoglobin clearance may be a proximate cause of neuronal damage after ICH. Treatment with iron chelators can reduce the upregulation of CD163 and decrease cell death (Liu et al., 2017).

The relative contributions of erythrolysis versus phagocytosis in blood clearance is an area of interest, though the time course of erythrolysis in hematomas is not well understood. Recently, erythrolysis was identified occurring earlier than previously suspected, within 24 hours of ICH (Dang et al., 2017). Early erythrolysis was correlated with upregulation of perihematomal CD163, and the degree of early erythrolysis correlated with the severity of neuronal loss. The early erythrolysis was detectable by T2* MRI and was facilitated by hypertension. Early erythrolysis and clearance via the CD163 mechanism are potential areas of further investigation.

Nuclear factor-erythroid 2 p45-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a transcription factor, is another recently discovered cell-signaling regulator of microglia function and hematoma clearance (Zhao et al., 2015). Upregulation of Nrf2 improved hematoma clearance in mouse and rat models of ICH, and hematoma clearance is impaired in Nrf2 knock-out mice. In vitro experiments suggest it reduces oxidative stress through its transactivation of cytoprotective target genes essential to cellular defense such as SOD (Park and Rho, 2002) and HO-1 (Alam et al., 1999), as well as by upregulating phagocytosis, likely through upregulation of one of its target genes, CD36.

5. Conclusions

ICH is the most deadly stroke subtype, yet no intervention has demonstrated improved outcomes. In fact some measures of supportive care previously thought beneficial, including very aggressive blood pressure lowering and platelet transfusion, have failed to show benefit in recent years. However, with the recent acceleration of research into ICH, including more preclinical studies and therapeutic strategies, it is hoped that better-informed clinical trials stand a greater chance of positive findings when looking for an elusive, effective treatment for ICH.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Intracerebral hemorrhage remains a deadly hemorrhagic stroke subtype.

Trials of interventional strategies have failed to show a beneficial effect.

Multiple trials of minimally invasive clot removal strategies are underway.

Studies of hematoma clearance mechanisms may reveal pharmacologic targets.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants NS-007222, NS-073959, NS-079157, NS-090925, NS-091545, NS-093399 and NS-096917 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

The authors are grateful to M. Foldenauer for artwork.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alam J, Stewart D, Touchard C, Boinapally S, Choi AM, Cook JL. Nrf2, a Cap“n”Collar transcription factor, regulates induction of the heme oxygenase-1 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:26071–26078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CS, Heeley E, Huang Y, Wang J, Stapf C, Delcourt C, Lindley R, Robinson T, Lavados P, Neal B, Hata J, Arima H, Parsons M, Li Y, Wang J, Heritier S, Li Q, Woodward M, Simes RJ, Davis SM, Chalmers J INTERACT2 Investigators. Rapid blood-pressure lowering in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:2355–2365. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baharoglu MI, Cordonnier C, Al-Shahi Salman R, de Gans K, Koopman MM, Brand A, Majoie CB, Beenen LF, Marquering HA, Vermeulen M, Nederkoorn PJ, de Haan RJ, Roos YB PATCH Investigators. Platelet transfusion versus standard care after acute stroke due to spontaneous cerebral haemorrhage associated with antiplatelet therapy (PATCH): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016a;387:2605–2613. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30392-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baharoglu MI, Cordonnier C, Al-Shahi Salman R, de Gans K, Koopman MM, Brand A, Majoie CB, Beenen LF, Marquering HA, Vermeulen M, Nederkoorn PJ, de Haan RJ, Roos YB PATCH Investigators. Platelet transfusion versus standard care after acute stroke due to spontaneous cerebral haemorrhage associated with antiplatelet therapy (PATCH): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016b;387:2605–2613. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30392-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biffi A, Battey TWK, Ayres AM, Cortellini L, Schwab K, Gilson AJ, Rost NS, Viswanathan A, Goldstein JN, Greenberg SM, Rosand J. Warfarin-related intraventricular hemorrhage: imaging and outcome. Neurology. 2011;77:1840–1846. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182377e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brott T, Broderick J, Kothari R, Barsan W, Tomsick T, Sauerbeck L, Spilker J, Duldner J, Khoury J. Early hemorrhage growth in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1997;28:1–5. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher K, Selim M. Acute Blood Pressure Management in Intracerebral Hemorrhage: Equipoise Resists an Attack. Stroke. 2016;47:3065–3066. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher KS, Jeerakathil T, Hill M, Demchuk AM, Dowlatshahi D, Coutts SB, Gould B, McCourt R, Asdaghi N, Findlay JM, Emery D, Shuaib A ICH ADAPT Investigators. The Intracerebral Hemorrhage Acutely Decreasing Arterial Pressure Trial. Stroke. 2013;44:620–626. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S, Zheng M, Hua Y, Chen G, Keep RF, Xi G. Hematoma Changes During Clot Resolution After Experimental Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2016;47:1626–1631. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervera A, Amaro S, Chamorro A. Oral anticoagulant-associated intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Neurol. 2012;259:212–224. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6153-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y-C, Chen C-M, Liu J-L, Chen S-T, Cheng M-L, Chiu DT-Y. Oxidative markers in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: leukocyte 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine as an independent predictor of the 30-day outcome. J. Neurosurg. 2011;115:1184–1190. doi: 10.3171/2011.7.JNS11718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Roetling J, Regan RF. Haptoglobin increases the vulnerability of CD163-expressing neurons to hemoglobin. J. Neurochem. 2016;139:586–595. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang G, Yang Y, Wu G, Hua Y, Keep RF, Xi G. Early Erythrolysis in the Hematoma After Experimental Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Transl. Stroke Res. 2017;8:174–182. doi: 10.1007/s12975-016-0505-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty ML, Tao H, Haverbusch M, Sekar P, Kleindorfer D, Kissela B, Khatri P, Stettler B, Adeoye O, Moomaw CJ, Broderick JP, Woo D. Warfarin use leads to larger intracerebral hematomas. Neurology. 2008;71:1084–1089. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000326895.58992.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebel JM, Jauch EC, Brott TG, Khoury J, Sauerbeck L, Salisbury S, Spilker J, Tomsick TA, Duldner J, Broderick JP. Natural history of perihematomal edema in patients with hyperacute spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2002;33:2631–2635. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000035284.12699.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioia L, Klahr A, Kate M, Buck B, Dowlatshahi D, Jeerakathil T, Emery D, Butcher K. The intracerebral hemorrhage acutely decreasing arterial pressure trial II (ICH ADAPT II) protocol. BMC Neurol. 2017;17:100. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-0884-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong C, Hoff JT, Keep RF. Acute inflammatory reaction following experimental intracerebral hemorrhage in rat. Brain Research. 2000;871:57–65. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02427-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NR, Shah J, Sangha N, Sosa L, Martinez R, Shen L, Kasam M, Morales MM, Hossain MM, Barreto AD, Savitz SI, Lopez G, Misra V, Wu T-C, Khoury El R, Sarraj A, Sahota P, Hicks W, Acosta I, Sline MR, Rahbar MH, Zhao X, Aronowski J, Grotta JC. Design of a prospective, dose-escalation study evaluating the Safety of Pioglitazone for Hematoma Resolution in Intracerebral Hemorrhage (SHRINC) Int J Stroke. 2013;8:388–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg SM, Vernooij MW, Cordonnier C, Viswanathan A, Al-Shahi Salman R, Warach S, Launer LJ, Van Buchem MA, Breteler MM Microbleed Study Group. Cerebral microbleeds: a guide to detection and interpretation. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:165–174. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70013-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Hua Y, Keep RF, Morgenstern LB, Xi G. Deferoxamine reduces intracerebral hematoma-induced iron accumulation and neuronal death in piglets. Stroke. 2009;40:2241–2243. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.539536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F, Hua Y, Wang J, Keep RF, Xi G. Inhibition of carbonic anhydrase reduces brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage. Transl. Stroke Res. 2012;3:130–137. doi: 10.1007/s12975-011-0106-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada R, Matsuoka H. Antithrombin therapy for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2000;31:794–795. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.3.791-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley DF. Intraventricular hemorrhage: severity factor and treatment target in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2009;40:1533–1538. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.535419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley DF, Lane K, McBee N, Ziai W, Tuhrim S, Lees KR, Dawson J, Gandhi D, Ullman N, Mould WA, Mayo SW, Mendelow AD, Gregson B, Butcher K, Vespa P, Wright DW, Kase CS, Carhuapoma JR, Keyl PM, Diener-West M, Muschelli J, Betz JF, Thompson CB, Sugar EA, Yenokyan G, Janis S, John S, Harnof S, Lopez GA, Aldrich EF, Harrigan MR, Ansari S, Jallo J, Caron J-L, LeDoux D, Adeoye O, Zuccarello M, Adams HP, Rosenblum M, Thompson RE, Awad IA CLEAR III Investigators. Thrombolytic removal of intraventricular haemorrhage in treatment of severe stroke: results of the randomised, multicentre, multiregion, placebo-controlled CLEAR III trial. Lancet. 2017;389:603–611. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32410-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley DF, Syed SJ. Current acute care of intracerebral hemorrhage. Rev Neurol Dis. 2007;4:10–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley DF, Thompson RE, Muschelli J, Rosenblum M, McBee N, Lane K, Bistran-Hall AJ, Mayo SW, Keyl P, Gandhi D, Morgan TC, Ullman N, Mould WA, Carhuapoma JR, Kase C, Ziai W, Thompson CB, Yenokyan G, Huang E, Broaddus WC, Graham RS, Aldrich EF, Dodd R, Wijman C, Caron J-L, Huang J, Camarata P, Mendelow AD, Gregson B, Janis S, Vespa P, Martin N, Awad I, Zuccarello M MISTIE Investigators. Safety and efficacy of minimally invasive surgery plus alteplase in intracerebral haemorrhage evacuation (MISTIE): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:1228–1237. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill JC, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS, Becker K, Bendok BR, Cushman M, Fung GL, Goldstein JN, Macdonald RL, Mitchell PH, Scott PA, Selim MH, Woo D American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology. Guidelines for the Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015 doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herweh C, Jüttler E, Schellinger PD, Klotz E, Jenetzky E, Orakcioglu B, Sartor K, Schramm P. Evidence against a perihemorrhagic penumbra provided by perfusion computed tomography. Stroke. 2007;38:2941–2947. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.486977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Y, Wu J, Keep RF, Nakamura T, Hoff JT, Xi G. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha increases in the brain after intracerebral hemorrhage and thrombin stimulation. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:542–50. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000197333.55473.AD. discussion 5427–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F-P, Xi G, Keep RF, Hua Y, Nemoianu A, Hoff JT. Brain edema after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage: role of hemoglobin degradation products. J. Neurosurg. 2002;96:287–293. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.96.2.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illanes S, Liesz A, Sun L, Dalpke A, Zorn M, Veltkamp R. Hematoma size as major modulator of the cellular immune system after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurosci. Lett. 2011;490:170–174. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keep RF, Hua Y, Xi G. Intracerebral haemorrhage: mechanisms of injury and therapeutic targets. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:720–731. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70104-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YZ, Kim KH. Even in patients with a small hemorrhagic volume, stereotactic-guided evacuation of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage improves functional outcome. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2009;46:109–115. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2009.46.2.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwashiro T, Yasaka M, Itabashi R, Nakagaki H, Miyashita F, Naritomi H, Minematsu K. Enlargement of acute intracerebral hematomas in patients on long-term warfarin treatment. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2010;29:446–453. doi: 10.1159/000289348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labib MA, Shah M, Kassam AB, Young R, Zucker L, Maioriello A, Britz G, Agbi C, Day JD, Gallia G, Kerr R, Pradilla G, Rovin R, Kulwin C, Bailes J. The Safety and Feasibility of Image-Guided BrainPath-Mediated Transsulcul Hematoma Evacuation: A Multicenter Study. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:515–524. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MC, Saver JL. Annual incidence of first silent stroke in the United States: a preliminary estimate. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2003;16:280–285. doi: 10.1159/000071128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KR, Kawai N, Kim S, Sagher O, Hoff JT. Mechanisms of edema formation after intracerebral hemorrhage: effects of thrombin on cerebral blood flow, blood-brain barrier permeability, and cell survival in a rat model. J. Neurosurg. 1997;86:272–278. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.2.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Cao S, Hua Y, Keep RF, Huang Y, Xi G. CD163 Expression in Neurons After Experimental Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2017;48:1369–1375. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.016850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord AS, Langefeld CD, Sekar P, Moomaw CJ, Badjatia N, Vashkevich A, Rosand J, Osborne J, Woo D, Elkind MSV. Infection after intracerebral hemorrhage: risk factors and association with outcomes in the ethnic/racial variations of intracerebral hemorrhage study. Stroke. 2014;45:3535–3542. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovelock CE, Molyneux AJ, Rothwell PM Oxford Vascular Study. Change in incidence and aetiology of intracerebral haemorrhage in Oxfordshire, UK, between 1981 and 2006: a population-based study. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:487–493. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q, Manaenko A, Khatibi NH, Chen W, Zhang JH, Tang J. Vascular adhesion protein-1 inhibition provides antiinflammatory protection after an intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke in mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:881–893. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen M, Graversen JH, Moestrup SK. Haptoglobin and CD163: captor and receptor gating hemoglobin to macrophage lysosomes. Redox Rep. 2001;6:386–388. doi: 10.1179/135100001101536490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masada T, Hua Y, Xi G, Yang GY, Hoff JT, Keep RF. Attenuation of intracerebral hemorrhage and thrombin-induced brain edema by overexpression of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. J. Neurosurg. 2001;95:680–686. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.95.4.0680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehndiratta P, Manjila S, Ostergard T, Eisele S, Cohen ML, Sila C, Selman WR. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy-associated intracerebral hemorrhage: pathology and management. Neurosurg Focus. 2012;32:E7. doi: 10.3171/2012.1.FOCUS11370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelow AD, Gregson BA, Fernandes HM, Murray GD, Teasdale GM, Hope DT, Karimi A, Shaw MDM, Barer DH STICH Investigators. Early surgery versus initial conservative treatment in patients with spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral haematomas in the International Surgical Trial in Intracerebral Haemorrhage (STICH): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;365:387–397. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17826-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelow AD, Gregson BA, Rowan EN, Murray GD, Gholkar A, Mitchell PM STICH II Investigators. Early surgery versus initial conservative treatment in patients with spontaneous supratentorial lobar intracerebral haematomas (STICH II): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;382:397–408. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60986-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Keep RF, Hua Y, Hoff JT, Xi G. Oxidative DNA injury after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Brain Research. 2005;1039:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Kuroda Y, Yamashita S, Zhang X, Miyamoto O, Tamiya T, Nagao S, Xi G, Keep RF, Itano T. Edaravone attenuates brain edema and neurologic deficits in a rat model of acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2008;39:463–469. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.486654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni W, Mao S, Xi G, Keep RF, Hua Y. Role of Erythrocyte CD47 in Intracerebral Hematoma Clearance. Stroke. 2016;47:505–511. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell HC, Rosand J, Knudsen KA, Furie KL, Segal AZ, Chiu RI, Ikeda D, Greenberg SM. Apolipoprotein E genotype and the risk of recurrent lobar intracerebral hemorrhage. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;342:240–245. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001273420403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okauchi M, Hua Y, Keep RF, Morgenstern LB, Schallert T, Xi G. Deferoxamine treatment for intracerebral hemorrhage in aged rats: therapeutic time window and optimal duration. Stroke. 2010;41:375–382. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.569830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orakcioglu B, Fiebach JB, Steiner T, Kollmar R, Jüttler E, Becker K, Schwab S, Heiland S, Meyding-Lamadé UK, Schellinger PD. Evolution of early perihemorrhagic changes--ischemia vs. edema: an MRI study in rats. Experimental Neurology. 2005;193:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EY, Rho HM. The transcriptional activation of the human copper/zinc superoxide dismutase gene by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin through two different regulator sites, the antioxidant responsive element and xenobiotic responsive element. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2002;240:47–55. doi: 10.1023/a:1020600509965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel TR, Schielke GP, Hoff JT, Keep RF, Lorris Betz A. Comparison of cerebral blood flow and injury following intracerebral and subdural hematoma in the rat. Brain Research. 1999;829:125–133. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01378-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon MTC, Fonville AF, Al-Shahi Salman R. Long-term prognosis after intracerebral haemorrhage: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 2014;85:660–667. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi AI, Mendelow AD, Hanley DF. Intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet. 2009;373:1632–1644. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60371-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi AI, Palesch YY, Barsan WG, Hanley DF, Hsu CY, Martin RL, Moy CS, Silbergleit R, Steiner T, Suarez JI, Toyoda K, Wang Y, Yamamoto H, Yoon B-W ATACH-2 Trial Investigators and the Neurological Emergency Treatment Trials Network. Intensive Blood-Pressure Lowering in Patients with Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:1033–1043. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi AI, Wilson DA, Hanley DF, Traystman RJ. No evidence for an ischemic penumbra in massive experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 1999;52:266–272. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan RF, Panter SS. Neurotoxicity of hemoglobin in cortical cell culture. Neurosci. Lett. 1993;153:219–222. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90326-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruíz-Sandoval JL, Cantú C, Barinagarrementeria F. Intracerebral hemorrhage in young people: analysis of risk factors, location, causes, and prognosis. Stroke. 1999;30:537–541. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.3.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco S, Marini C, Toni D, Olivieri L, Carolei A. Incidence and 10-year survival of intracerebral hemorrhage in a population-based registry. Stroke. 2009;40:394–399. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.523209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadrzadeh SM, Anderson DK, Panter SS, Hallaway PE, Eaton JW. Hemoglobin potentiates central nervous system damage. J. Clin. Invest. 1987;79:662–664. doi: 10.1172/JCI112865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellinger PD, Fiebach JB, Hoffmann K, Becker K, Orakcioglu B, Kollmar R, Jüttler E, Schramm P, Schwab S, Sartor K, Hacke W. Stroke MRI in intracerebral hemorrhage: is there a perihemorrhagic penumbra? Stroke. 2003;34:1674–1679. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000076010.10696.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selim M, Yeatts S, Goldstein JN, Gomes J, Greenberg S, Morgenstern LB, Schlaug G, Torbey M, Waldman B, Xi G, Palesch Y Deferoxamine Mesylate in Intracerebral Hemorrhage Investigators. Safety and tolerability of deferoxamine mesylate in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2011;42:3067–3074. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.617589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Liu J, Zhou C, Ostanin D, Grisham MB, Neil Granger D, Zhang JH. Role of NADPH oxidase in the brain injury of intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Neurochem. 2005;94:1342–1350. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Asch CJ, Luitse MJ, Rinkel GJ, van der Tweel I, Algra A, Klijn CJ. Incidence, case fatality, and functional outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and ethnic origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:167–176. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vespa P, Hanley D, Betz J, Hoffer A, Engh J, Carter R, Nakaji P, Ogilvy C, Jallo J, Selman W, Bistran-Hall A, Lane K, McBee N, Saver J, Thompson RE, Martin N ICES Investigators. ICES (Intraoperative Stereotactic Computed Tomography-Guided Endoscopic Surgery) for Brain Hemorrhage: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Stroke. 2016;47:2749–2755. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada R, Aviv RI, Fox AJ, Sahlas DJ, Gladstone DJ, Tomlinson G, Symons SP. CT angiography “spot sign” predicts hematoma expansion in acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2007;38:1257–1262. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000259633.59404.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KR, Xi G, Hua Y, Kleinholz M, de Courten-Myers GM, Myers RE, Broderick JP, Brott TG. Lobar intracerebral hemorrhage model in pigs: rapid edema development in perihematomal white matter. Stroke. 1996;27:490–497. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.3.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. Preclinical and clinical research on inflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage. Progress in Neurobiology. 2010;92:463–477. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Rogove AD, Tsirka AE, Tsirka SE. Protective role of tuftsin fragment 1–3 in an animal model of intracerebral hemorrhage. Ann. Neurol. 2003;54:655–664. doi: 10.1002/ana.10750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W-Z, Jiang B, Liu H-M, Li D, Lu C-Z, Zhao Y-D, Sander JW. Minimally invasive craniopuncture therapy vs. conservative treatment for spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: results from a randomized clinical trial in China. Int J Stroke. 2009;4:11–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willingham SB, Volkmer J-P, Gentles AJ, Sahoo D, Dalerba P, Mitra SS, Wang J, Contreras-Trujillo H, Martin R, Cohen JD, Lovelace P, Scheeren FA, Chao MP, Weiskopf K, Tang C, Volkmer AK, Naik TJ, Storm TA, Mosley AR, Edris B, Schmid SM, Sun CK, Chua M-S, Murillo O, Rajendran P, Cha AC, Chin RK, Kim D, Adorno M, Raveh T, Tseng D, Jaiswal S, Enger PØ, Steinberg GK, Li G, So SK, Majeti R, Harsh GR, van de Rijn M, Teng NNH, Sunwoo JB, Alizadeh AA, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. The CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPa) interaction is a therapeutic target for human solid tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:6662–6667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121623109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi G, Keep RF, Hoff JT. Erythrocytes and delayed brain edema formation following intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. J. Neurosurg. 1998;89:991–996. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.6.0991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue M, Del Bigio MR. Intracerebral injection of autologous whole blood in rats: time course of inflammation and cell death. Neurosci. Lett. 2000;283:230–232. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00971-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang GY, Betz AL, Chenevert TL, Brunberg JA, Hoff JT. Experimental intracerebral hemorrhage: relationship between brain edema, blood flow, and blood-brain barrier permeability in rats. J. Neurosurg. 1994;81:93–102. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.1.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeatts SD, Palesch YY, Moy CS, Selim M. High dose deferoxamine in intracerebral hemorrhage (HI-DEF) trial: rationale, design, and methods. Neurocrit Care. 2013;19:257–266. doi: 10.1007/s12028-013-9861-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zazulia AR, Diringer MN, Derdeyn CP, Powers WJ. Progression of mass effect after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1999;30:1167–1173. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.6.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zazulia AR, Diringer MN, Videen TO, Adams RE, Yundt K, Aiyagari V, Grubb RL, Powers WJ. Hypoperfusion without ischemia surrounding acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2001;21:804–810. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Grotta J, Gonzales N, Aronowski J. Hematoma resolution as a therapeutic target: the role of microglia/macrophages. Stroke. 2009;40:S92–4. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.533158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Sun G, Ting S-M, Song S, Zhang J, Edwards NJ, Aronowski J. Cleaning up after ICH: the role of Nrf2 in modulating microglia function and hematoma clearance. J. Neurochem. 2015;133:144–152. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Chen J, Li Q, Ren G, Yao G, Liu M, Dong Q, Li L, Guo J, Xie P. Minimally invasive surgery for spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stroke. 2012;43:2923–2930. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.667535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.