Abstract

Zinc is an essential trace element required for normal cell growth, development, and differentiation. It is involved in DNA synthesis, RNA transcription, and cell division and activation. It is a critical component in many zinc protein/ enzymes, including critical zinc transcription factors. Zinc deficiency/altered metabolism is observed in many types of liver disease, including alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and viral liver disease. Some of the mechanisms for zinc deficiency/ altered metabolism include decreased dietary intake, increased urinary excretion, activation of certain zinc transporters, and induction of hepatic metallothionein. Zinc deficiency may manifest itself in many ways in liver disease, including skin lesions, poor wound healing/liver regeneration, altered mental status, or altered immune function. Zinc supplementation has been documented to block/attenuate experimental ALD through multiple processes, including stabilization of gut-barrier function, decreasing endotoxemia, decreasing proinflammatory cytokine production, decreasing oxidative stress, and attenuating apoptotic hepatocyte death. Clinical trials in human liver disease are limited in size and quality, but it is clear that zinc supplementation reverses clinical signs of zinc deficiency in patients with liver disease. Some studies suggest improvement in liver function in both ALD and hepatitis C following zinc supplementation, and 1 study suggested improved fibrosis markers in hepatitis C patients. The dose of zinc used for treatment of liver disease is usually 50 mg of elemental zinc taken with a meal to decrease the potential side effect of nausea.

Keywords: zinc, liver diseases, liver diseases, alcoholic, liver cirrhosis, hepatitis

Zinc is the second most prevalent trace element in the body. It is integrally involved in the normal life cycle and has many important regulatory, catalytic, and defensive functions. Zinc was shown to be an essential trace nutrient for rodents in the 1930s and in humans in 1963, and it plays a catalytic role in a host of enzymes. Zinc plays a major role in the regulation of gene expression through metal-binding transcription factors and metal response elements in the promoter regions of the regulated genes. Zinc also plays a critical role in zinc-finger motifs. Zinc fingers typically have 4 cysteines within the protein that allow zinc to be bound in a tetrahedral complex.

Liver disease, especially alcoholic liver disease (ALD), has been associated with hypozincemia and zinc deficiency for more than half a century.1,2 These early ALD observations were confirmed by multiple investigators, and tissue concentrations of zinc have been demonstrated to be decreased in alcoholic cirrhosis as well as animal models of liver disease.3–11 This article updates these early observations on dysregulated zinc metabolism in liver disease with new advances in this area and will review (1) clinical manifestations of zinc deficiency and their relevance to liver disease, (2) zinc metabolism, (3) zinc and ALD, (4) zinc and viral liver disease, (5) zinc and other liver diseases, and (6) general recommendations concerning zinc supplementation and overall conclusions.

Much of our knowledge concerning the metabolic functions of zinc in humans is derived from manifestations of zinc deficiency in zinc-deficient animals, in patients with acrodermatitis enteropathica (a hereditary disease of impaired zinc absorption), or in patients with acquired zinc deficiency due to an underlying disease process.12 It is also becoming clear that clinical and biochemical manifestations of zinc deficiency often occur when some stress is placed on the organism.13,14 In liver disease, this stress may occur through increased gut permeability with endotoxemia, infections such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, or release of stress hormones. Selected potential clinical manifestations of zinc deficiency in liver disease are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical Manifestations of Zinc Deficiency

| 1 | Skin lesions |

| 2 | Depressed mental function, encephalopathy |

| 3 | Impaired night vision; altered vitamin A metabolism |

| 4 | Anorexia (with possible alterations in taste and smell acuity) |

| 5 | Hypogonadism |

| 6 | Depressed wound healing |

| 7 | Altered immune function |

Clinical Manifestations of Zinc Deficiency in Liver Disease

Skin Lesions

The effects of zinc deficiency are particularly obvious on the skin, as manifested by an erythematous rash or scaly plaques. Many common dermatological conditions (eg, dandruff, acne, diaper rash) have been associated with zinc deficiency or effectively treated with zinc.15 Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is a rare hereditary disease characterized by skin lesions, alopecia, failure to thrive, diarrhea, impaired immune function with frequent infections, and, in some cases, ocular abnormalities.16–19 The skin lesions (acrodermatitis) tend to occur around the eyes, nose, and mouth; over the buttocks and perianal regions; and sometimes in an acral distribution. The signs and symptoms of AE are caused by zinc deficiency due to impaired intestinal absorption of zinc. AE is caused by mutations of the SLC39A4 gene on the chromosome band 8q24.3, encoding a zinc transporter in humans (Zip4).19

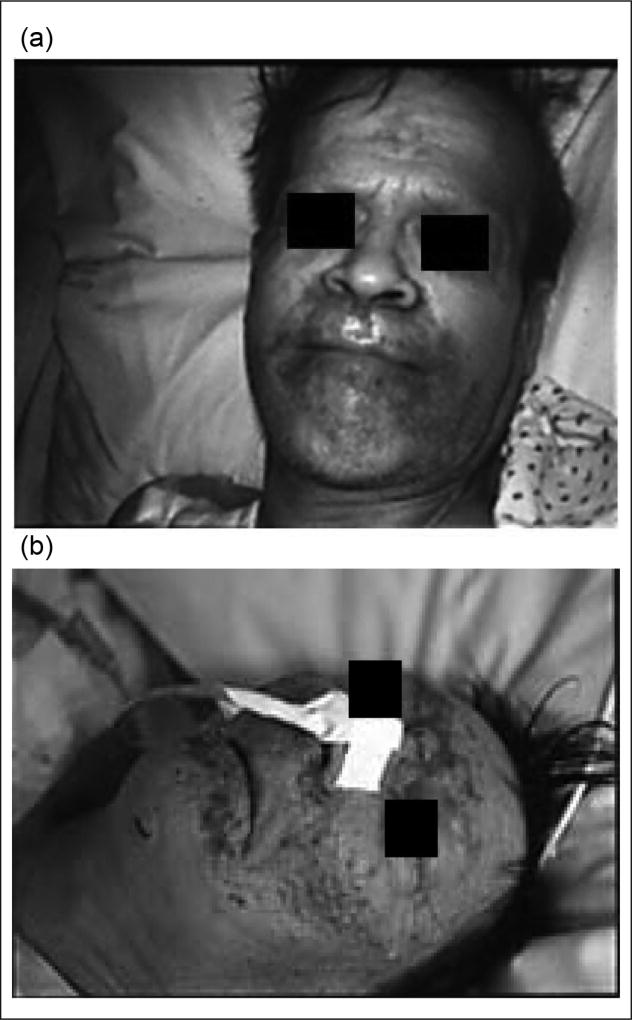

Patients with ALD and other forms of liver disease are predisposed to develop the skin lesions of zinc deficiency because of marginal underlying total body zinc stores. Several cases of acrodermatitis also have been reported in alcoholics with or without liver disease who were not receiving zinc in their hyperalimentation solutions or who had inadequate dietary intake of zinc (Figure 1).20–24

Figure 1.

Classic skin lesions around the eyes, nose, and mouth in 2 alcoholics with extremely low serum zinc levels (a, b). Skin lesions rapidly resolved in both patients with zinc supplementation. Patient 1b had encephalopathy that was initially believed to be hepatic encephalopathy. However, this resolved with zinc supplementation, documenting how zinc deficiency can cause mental disturbances. From McClain et al20 and McClain.21

Zinc deficiency is also associated with necrolytic acral erythema (NAE).25 NAE is a recently recognized dermatosis, presenting in the form of pruritic, symmetric, well-demarcated, hyperkeratotic, erythematous-to-violaceous, lichenified plaques with a rim of dusky erythema on the dorsal aspects of the feet and extending to the toes. NAE is associated with decreased serum and skin zinc levels and is almost always associated with HCV infection, thereby serving as a cutaneous marker for underlying HCV infection.26 Use of oral zinc therapy is highly effective and leads to NAE resolution in combination with treatment of the underlying HCV infection.27

Depressed Mental Function and Encephalopathy

Early studies by Henkin et al28 reported that experimentally induced zinc deficiency in humans may be accompanied by apathy or irritability, which is reversed with zinc supplementation. Similarly, children with AE may have apathy or confusion, which responds to zinc supplementation. We have observed patients receiving parenteral nutrition (PN) who developed severe depression or confusion and severe hypozincemia. Marked improvement in mental status coincided with zinc supplementation in these patients.20,21

Portal systemic (hepatic) encephalopathy (PSE) is a derangement of mental function caused by liver disease or shunting of blood around the liver.29–31 This disordered mental state ranges in severity from intellectual impairment detectable only by careful psychometric testing to frank coma.29 Gut-derived toxins such as ammonia, mercaptans, short-chain fatty acids, false neurotransmitters, metabolites of tryptophan, and others are postulated to play an etiological role in this disordered mental status.29 Patients with cirrhosis have depressed serum zinc levels, and those with hepatic encephalopathy have statistically reduced serum zinc concentrations.32,33 Zinc is integrally involved in the metabolism of ammonia. Zinc deficiency markedly decreases activity of the urea cycle enzyme, ornithine transcarbamylase, and zinc supplementation corrects this.34 Similarly, zinc deficiency has been reported to impair activity of muscle glutamine synthetase, which causes hyperammonemia.35 Glutamine synthetase activity has also been reported to be decreased in patients with encephalopathy.36 Several trials have reported using zinc supplementation in various stages of PSE with somewhat inconsistent results. In the most recent large randomized clinical trial, polaprezinc supplementation plus standard therapy for 6 months (compared with standard therapy alone, protein-restricted diet with branched-chain amino acids and lactulose) was associated with a significant improvement in encephalopathy grade, blood ammonia levels, serum albumin levels, and a variety of psychomotor performance tests.37 Last, overt hepatic encephalopathy has been induced in a subject by creating zinc deficiency, and encephalopathy was then reversed with zinc supplementation.38

Impaired Night Vision

Impaired night vision has been recognized in alcoholic cirrhotics since the late 1930s, and this has been confirmed in recent studies in many types of cirrhosis.39–41 This is usually associated with vitamin A deficiency, and vitamin A supplementation improved night vision. Several groups, including our own, have shown that some individuals with cirrhosis require not only vitamin A but also zinc supplementation to correct or improve their dark adaptation.42,43 Zinc and vitamin A interact on many different levels, including production of retinol-binding protein and activity of retinol dehydrogenase. Studies in zinc-deficient experimental animals also demonstrated progressive anatomic deterioration of the retina.44,45 Similar retinal degeneration was observed in a patient with AE.46 Thus, there is strong clinical and experimental evidence that zinc affects retinal function, and zinc supplementation may improve dark adaptation in some patients with liver disease.

Anorexia With Altered Taste/Smell

A major and initial manifestation of zinc deficiency is anorexia with subsequent weight loss.47 The mechanism(s) by which zinc deficiency produces anorexia is unknown. Initially, alterations in taste acuity and in circulating amino acids were implicated as etiologic factors.48,49 We showed that zinc deficiency in the rat affected catecholamine levels in total brain and in specific regions of the hypothalamus. We demonstrated that zinc-deficient animals are resistant to the central administration of known inducers of food intake such as norepinephrine and muscimol.50 Zinc is extremely important for normal membrane structure and function.51 We speculated that there is a decrease in receptor responsivity in the zinc-deficient animal, possibly secondary to alterations in membrane fluidity, which may explain, at least partially, the severe anorexia noted in these animals.

Patients with alcoholic liver disease frequently complain of anorexia and have decreased food consumption.52,53 Patients with acute liver disease also frequently complain of unpleasant olfactory and gustatory sensations, and this usually improves as the liver disease resolves. Burch et al54 reported decreased taste and smell acuity in cirrhotics with hypozincemia. Smith et al55 demonstrated objective disordered gustatory acuity in both viral hepatitis patients and patients with chronic liver disease (both groups had hypozincemia).

Hypogonadism

Zinc deficiency is a well-recognized cause of hypogonadism in experimental animals and humans.56 Chronic alcoholics with and without liver disease and other patients with liver disease of multiple etiologies may have hypogonadism.57 The hypogonadism of zinc deficiency appears to be primarily a gonadal defect.56,58 Adequate levels of gonadotrophins and intact gonadotrophin response to luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone have been demonstrated in zinc-deficient animals. Zinc-deficient animals have reduced basal testosterone levels and depressed weights of testes and other androgensensitive organs compared with zinc-sufficient controls.58 Humans fed a zinc-deficient diet developed decreased libido, depressed serum testosterone levels, and marked reduction in sperm counts.59,60 Moreover, zinc supplementation significantly increased serum testosterone in elderly men with marginal zinc deficiency. Zinc is also required for maintenance of sperm cells, progression of spermatogenesis, and sperm motility.61,62

Depressed Wound Healing

The role of zinc in nucleic acid metabolism, in the synthesis of structural proteins such as collagen, and in a host of enzymatic pathways makes zinc balance important for wound healing. A clinical role for zinc in wound healing was initially postulated by Pories et al63 with the observation of improved healing of pilonidal sinuses with zinc administration. Subsequent controlled studies by Hallböök and Lanner64 demonstrated that zinc supplementation improved wound healing in patients with both venous leg ulcers and decreased serum zinc concentrations. Several investigators then reported depressed wound healing in experimental animal models (eg, thermal and excised wounds, gastric ulcers) in zinc-deficient compared to zinc-sufficient animals.65,66 Recent studies have supported the important clinical role of zinc in wound healing, especially in leg ulcers.

Hepatocyte regeneration after liver injury represents a form of wound healing. After partial hepatectomy or liver injury, hepatocytes undergo a synchronized, multistep process consisting of priming/initiation, proliferation, and termination. These steps are essential for restoring the structure and functions of the liver. The regenerating liver requires a large amount of zinc over a short period of time. This demand is met, in part, by induction of the zinc/copper binding protein metallothionein.67 Metallothionein can transfer zinc to various metalloenzymes and transcription factors, and metallothionein knockout mice have impaired liver regeneration.68 Thus, zinc is essential for wound healing at peripheral sites as well as for liver regeneration.

Altered Immune Function

The effect of zinc deficiency on immune function in humans was initially studied in children with AE.69 Leukocyte function and cell-mediated immunity were impaired in these children and corrected with zinc supplementation. Golden et al70 described thymic atrophy in children with protein energy malnutrition and zinc deficiency, and this thymic atrophy reversed with zinc supplementation. We reported 2 patients who developed severe zinc deficiency with acrodermatitis while on PN. These patients had cutaneous anergy and markedly depressed T cell response to phytohemaglutinin,71 which corrected with zinc supplementation alone.

Results from these early human studies have been supported by a variety of in vitro and animal research documenting a critical role for zinc in multiple aspects of innate and adaptive immunity. Well-established effects of zinc deficiency include thymic atrophy, alterations in thymic hormones, lymphopenia, and compromised cellular and antibody-mediated responses, which can result in increased rates and duration of infection.72–74

Recent studies in experimental animals and humans support the concepts of dysregulated zinc metabolism during infections and zinc deficiency increasing morbidity and mortality following infection. Work from Knoell’s laboratory showed that zinc deficiency increases systemic inflammation, organ damage, and mortality in a small animal model of sepsis.75 Using a cecal ligation and puncture model, they showed that zinc-deficient animals had increased bacterial burden, enhanced nuclear factor–κB (NF-κB)–binding activity, increased expression of NF-κB-targeted genes such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and ICAM-1, and increased acute-phase proteins. Similarly, genome-level expression profiling in patients with pediatric septic shock demonstrated that altered zinc homeostasis predicted poor outcome.76 Of the genes most prominently up- or downregulated, many play important roles in zinc homeostasis. We postulate that patients with liver disease who have underlying dysregulated zinc homeostasis will have this altered zinc metabolism exacerbated by infection or inflammation, potentially leading to poor outcome.

Zinc Metabolism

Zinc is an essential nutrient for a broad range of biological activities. In the United States, the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) is 8 mg/d for women and 11 mg/d for men older than age 19. Red meats, especially beef, lamb, and liver, as well as certain sea foods (eg, oysters), have some of the highest concentrations of zinc in food. Zinc and dietary protein directly correlate with each other. Patients with liver disease, especially ALD, often have poor diets that are low in protein and low in zinc. Moreover, some dietary fibers/phytates can reduce zinc absorption. Absorption of zinc is concentration dependent and occurs throughout the small intestine (mainly the jejunum). Absorption may be impaired in cirrhosis, and typically there is increased urinary excretion of zinc in cirrhosis.12

Zinc absorption, transfer, and excretion are accomplished by 2 large classes of transporters that tend to have opposing effects (ZnT proteins and Zip transporters).73,77–79 The Zip family of transporters move zinc from the extracellular space into the cellular cytoplasm. Indeed, Zip4 plays a major role in intestinal zinc absorption, and a lack of this transporter causes acrodermatitis enteropathica. The ZnT proteins generally work in opposition to the Zip transporters.

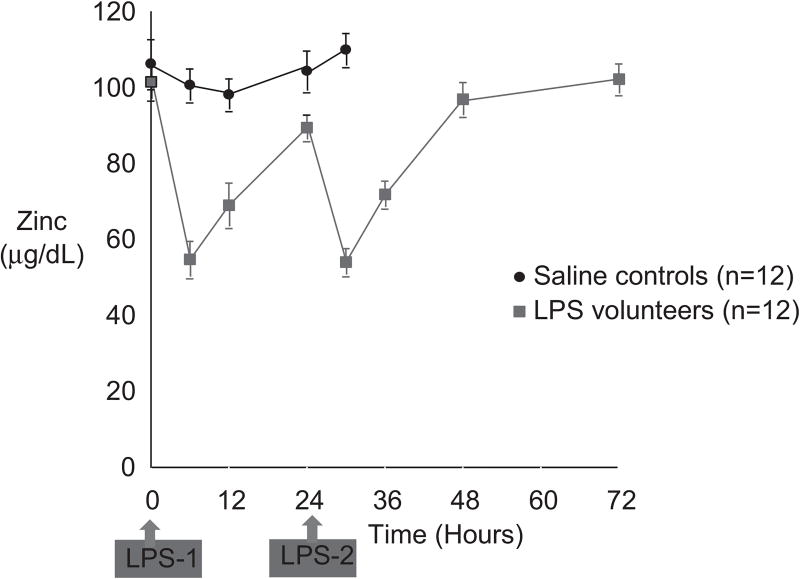

Zinc status and the serum zinc level drop with low dietary zinc intake. There normally are multiple mechanisms in place to protect against zinc deficiency, including increased absorption and decreased excretion via modification of zinc transporters.77,79 Zinc status is typically assessed by plasma/serum zinc concentration. However, inflammation/stress hormones may cause a decrease in serum zinc level, with an internal redistribution of the zinc (Figure 2).13,14,79 This stress response is often associated with hypoalbuminemia. Albumin is a major binding protein for zinc, but the serum zinc concentration will decrease with an inflammatory stimulus even in the absence of hypoalbuminemia (Figure 2).13 This is mediated at least in part by changes in zinc transporters, especially induction of Zip14 and induction of hepatic metallothionein.73 Metallothionein is a metal-binding protein that serves many functions, including zinc transport, antioxidant activity, and modulation of zinc absorption.8,77,79 Indeed, ingestion of pharmacologic amounts of zinc causes induction of intestinal metallothionein, which then inhibits intestinal copper uptake and induces negative copper balance in the treatment of Wilson disease (discussed subsequently).

Figure 2.

Healthy volunteers were injected intravenously with low-dose endotoxin or lipopolysaccharide (LPS). There was a marked reduction in the serum zinc level, which nearly normalized by 24 hours. A second dose of LPS caused a similar reduction in serum zinc. Injection of vehicle caused no significant reduction in zinc. Importantly, this very low dose of endotoxin caused no changes in the serum albumin.13 Thus, the hypozincemia was not secondary to a drop in the serum albumin level.

Although we are beginning to learn about the role of zinc transporters in experimental inflammation and in human infections, no studies to date in human cirrhosis have evaluated this important topic. Expanded knowledge of intracellular zinc metabolism and the role of zinc transporters in liver disease will enhance our understanding concerning altered zinc metabolism and zinc therapeutic effects in liver disease.

Zinc and Alcoholic Liver Disease

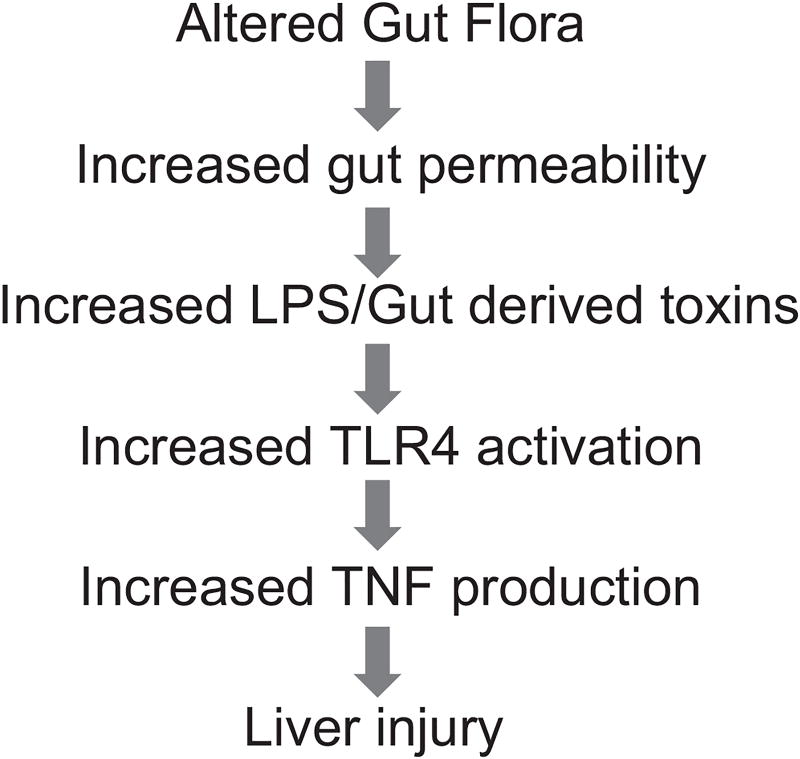

ALD continues to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. Two-thirds of Americans consume alcohol, and an estimated 14 million Americans are alcoholics.80 It has been estimated that 15%–30% of heavy drinkers develop advanced ALD. Alcoholic cirrhosis accounts for more than 40% of all deaths from cirrhosis and for 30% of all hepatocellular carcinomas.80–82 Significant advances have been made in our understanding of the pathophysiologic mechanisms of ALD. However, there is still no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapy for this common and often devastating disease. Interactions between the bowel, immune system, and the liver are critical components of ALD. In this model, chronic alcoholism results in changes to the intestinal epithelial barrier, leading to increased gut permeability.83 Subsequently, endotoxin or lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of the gram-negative bacterial cell wall, translocates across the disrupted intestinal barrier and enters the portal venous circulation to stimulate primed Kupffer cells. This results in both proinflammatory cytokine production and generation of reactive oxygen species, key mediators of ALD (Figure 3).81–83 Zinc deficiency is well documented in both humans with alcoholic cirrhosis and in animal models of ALD.8 In a representative human study, the serum zinc concentration in alcoholic patients was 7.52 µmol/L, which was significantly lower than 12.69 µmol/L in control subjects.84 Moreover, the decrease in serum zinc correlates with progression of liver damage. Patients with alcoholic cirrhosis had a lower serum zinc level (80 µg/dL) than noncirrhotic patients (97 µg/dL), decreased by –37% and –24%, respectively, compared with healthy individuals (127 µg/dL).85 We have demonstrated that zinc supplementation attenuates ethanol-induced liver injury in murine models.8,86–90 Importantly, zinc protected intestinal barrier function to prevent endotoxemia, reducing both proinflammatory cytokine production and oxidative stress (Figure 4). These data provide a strong rationale for zinc supplementation in human ALD. Below, we discuss in greater detail the effects of zinc deficiency/zinc supplementation on specific pathways for ALD.

Figure 3.

This graph depicts the gut-liver axis in alcoholic liver disease (ALD), beginning with altered gut flora and gut leakiness, leading to endotoxin-stimulated cytokine production, and, ultimately, liver injury and systemic inflammation. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; TLR, toll-like receptor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

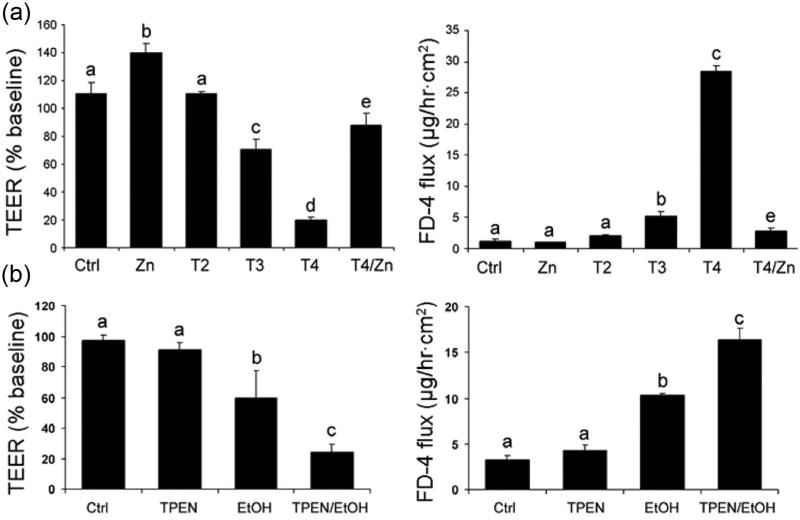

Figure 4.

Zinc deficiency can disrupt intestinal-barrier function in vitro (a), and zinc deficiency can enhance alcohol-induced intestinal-barrier dysfunction (b). (a) Effect of zinc deprivation on the epithelial barrier of Caco-2 cells. Caco-2 cells were cultured on inserts and treated with N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis (2-pyridylmethyl) ethylenediamine (TPEN) at 2, 3, and 4 µM or 4 µM TPEN plus 100 µM zinc for 24 hours. The epithelial barrier function was assessed by measuring transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) and FD-4 permeability. Results are means ± SD (n = 8). Significant differences (P < .05, analysis of variance [ANOVA]) are identified by different letters, a–e. T, TPEN. (b) Sensitizing effect of zinc deprivation on alcohol-induced epithelial barrier dysfunction. Caco-2 cells were cultured on inserts and treated with TPEN at 2 µM for 24 hours, followed by treatment with 5% (vol/vol) ethanol for 5 hours. The epithelial barrier function assessed by measuring TEER and FD-4 permeability. Results are means ± SD (n = 8). Significant differences (P < .05, ANOVA) are identified by different letters, a–c. From Zhong et al.100

Alcohol, Gut Permeability, Endotoxemia, and Proinflammatory Cytokine Production

As noted above, endotoxemia plays an important role in the development of ALD through stimulating proinflammatory cytokine production.83 Disruption of the intestinal barrier has been suggested to be a leading cause of alcohol-induced endotoxemia.83 Alcoholic patients showed increased gut permeability to a variety of permeability markers, such as polyethyleneglycol, mannitol/lactulose, or 51CrEDTA.91–94 In animal studies, gut permeability to macromolecules such as horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was increased in association with alcohol-induced plasma endotoxemia and liver damage.95–98 We showed that orally administrated LPS can be detected in the plasma of alcohol-intoxicated mice but not in control mice,99 providing direct evidence that alcohol increases gut permeability to endotoxin. Animal studies also showed that preventing gut leakiness results in suppression of alcohol-associated endotoxemia and liver damage, suggesting that gut leakiness is a causal factor in the development of alcoholic endotoxemia and liver injury.96,97,99

Because of the above-noted findings, we carried out a series of studies to determine whether zinc deficiency is related to the deleterious effects of alcohol on the intestinal barrier. We fed mice an alcohol or isocaloric liquid diet for 4 weeks, and liver injury was detected in association with elevated blood endotoxin level.100 Alcohol exposure significantly increased the permeability of the ileum. Reduction of tight-junction proteins in the ileal epithelium was observed in alcohol-fed mice. Alcohol exposure significantly reduced the ileal zinc concentration in association with accumulation of reactive oxygen species. Using in vitro studies, Caco-2 cell cultures demonstrated that alcohol exposure increased the intracellular free zinc because of oxidative stress. Zinc deprivation caused epithelial barrier disruption in association with disassembling of tight junction proteins in the Caco-2 monolayer cells.100 Furthermore, minor zinc deprivation exaggerated the deleterious effect of alcohol on the epithelial barrier.100 In summary, alcohol disrupts intestinal barrier function and induces endotoxemia, in part, by causing alterations in intestinal zinc homeostasis. Zinc supplementation partially protects against this increased permeability, endotoxemia, increased cytokine production, and subsequent liver injury.

Oxidative Stress

Zinc can attenuate oxidative stress through introduction of metallothionein and through multiple other mechanisms, such as inhibiting TNF and modulating multiple enzymes. Zinc supplementation in a mouse model of ALD attenuated alcohol-induced liver injury as measured by histopathological and ultrastructural changes, serum alanine transferase activity, and hepatic TNF-α levels. Zinc supplementation inhibited accumulation of ROS as indicated by dihydroethidium fluorescence and the subsequent oxidative damage as assessed by immunohistochemical detection of 4-hydroxynonenal and nitrotyrosine and quantitative analysis of malondialdehyde and protein carbonyl in the liver.101 Zinc supplementation suppressed alcohol-elevated CYP 2E1 activity but increased the activity of alcohol dehydrogenase in the liver. Zinc supplementation also prevented alcohol-induced decreases in glutathione (GSH) concentration and glutathione peroxidase activity and increased glutathione reductase activity in the liver.8,101

Apoptosis

Apoptosis is a major mechanism of hepatocyte death in ALD. We evaluated the possible beneficial effects of zinc therapy in experimental ALD. Adult male mice fed an alcohol liquid diet for 6 months developed hepatitis as indicated by neutrophil infiltration and elevation of the chemokines, keratinocyte chemoattractant, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Apoptotic cell death was detected in alcohol-exposed mice by a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay and confirmed by the increased activities of caspase-3 and −8. Zinc supplementation attenuated alcoholic hepatitis and reduced the number of TUNEL-positive cells in association with inhibition of caspase activities.90 The mRNA levels of TNF-α, TNF-R1, FasL, Fas, FAF-1, and caspase-3 in the liver were upregulated by alcohol exposure and were attenuated by zinc supplementation.89,90 Zinc supplementation also prevented elevated serum and hepatic TNF-α levels and TNF-α R1 and Fas proteins in the liver associated with alcohol feeding. Thus, zinc supplementation attenuated the increase in factors known to be associated with hepatic apoptosis.8,90

Zinc Supplementation and Human ALD

There have been multiple studies showing that zinc supplementation reverses known manifestations of zinc deficiency in ALD, such as impaired night vision, skin lesions, and, in some cases, encephalopathy and immune dysfunction.12 Studies have been performed to determine the duration and amounts of zinc necessary to improve serum and hepatic zinc in patients with ALD. Alcoholic patients without cirrhosis received zinc sulfate at 600 mg/d for 10 days and alcoholic cirrhotics for 10, 30, and 60 days.102 Serum zinc concentrations increased to normal values in all groups of patients during 10 days to 2 months of zinc supplementation. Zinc concentrations in the liver biopsies were significantly increased in patients with cirrhosis after zinc supplementation for 10 and 60 days, but some patients remained under normal values, particularly those with cirrhosis. No adverse reactions of zinc supplementation were observed in this short-term study.

A long-term oral zinc supplementation (200 mg tid for 2–3 months) in cirrhotic patients, including alcoholics, produced beneficial effects on both liver metabolic function and nutrition parameters.103 Quantitative liver function tests, including galactose elimination capacity and antipyrine clearance, improved following oral zinc supplementation. Similarly, the Child-Pugh score, an overall clinical estimation of hepatocellular failure, was improved by zinc supplementation on average by greater than 1 point. Zinc supplementation also significantly improved nutrition parameters, such as serum prealbumin, retinol-binding protein, and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). Indeed, the serum IGF-1 increased approximately 30% after zinc therapy. However, the nutrition parameters remained on average below the lower limit of the normal range.103 Studies evaluating specific mechanisms of action of zinc in ALD and long-term outcome studies are needed.

Zinc and Viral Liver Disease

HCV

Approximately 3% (~170 million) of the world’s population has been infected with HCV. For most countries, the prevalence of HCV infection is <3% (2% in United States).104,105 Approximately 70% of acute HCV infection progresses to chronic liver disease. The current standard of care for chronic HCV infection is based on the combination of pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Approximately 40%– 50% of genotype 1, by far the most frequent HCV genotype in the United States, is cured with this type of therapy. Specific protease inhibitors, telaprevir and boceprevir, became available in 2011, and this new addition to the interferon and ribavirin regimen should substantially increase the cure rate of both naive patients and many individuals who have already been treated.104,105

Similar to ALD, the serum levels of zinc are often decreased in HCV patients, and serum levels also tend to negatively correlate with hepatic reserve and to decrease with interferon-based therapy.105–108 Serum zinc levels are not only decreased in many patients with hepatitis C, but there are functional correlations with the reduced serum zinc levels. For example, patients have reduced taste sensitivity that correlates with their reduced serum zinc levels. Moreover, it is increasingly recognized that some patients with hepatitis C have decreased skin levels of zinc as well as serum zinc levels.106 HCV patients may present with necrolytic acral erythema, which responds to zinc supplementation (discussed above).

There are many therapeutic reasons why zinc may be beneficial in the treatment of hepatitis C, including (1) anti-oxidant function, (2) regulation of the imbalance between TH1 and TH2 cells, (3) zinc enhancement of antiviral effects of interferon, (4) inhibitory effects of zinc in the HCV replicon system, and (5) hepatoprotective effects of metallothionein.105,109 Several studies have evaluated the role of zinc as an adjunct therapy for eradication of the HCV. Initial studies indicated that administration of zinc in combination with interferon was more effective than interferon alone.110,111 However, in subsequent studies, when pegylated interferon and ribavirin were used in combination, the addition of zinc generally produced limited benefits on viral clearance.112 Some of these combination studies have shown improved transaminases or fewer medication side effects while on zinc therapy.113–115

Although the beneficial effects of zinc as an adjunct antiviral therapy for hepatitis C appear to be limited, there is promising evidence that zinc may decrease liver injury and provide antifibrotic effects in patients with chronic HCV. Himoto and coworkers107 used polaprezinc as an antifibrotic therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C and showed a decrease in noninvasive fibrosis markers. Subsequently, Matsuoka and coworkers116 treated chronic HCV patients for 3 years with polaprezinc 150 mg bid. Zinc therapy was associated with improvement of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). Interestingly, patients with lower zinc concentrations showed later reduction in liver enzymes following zinc supplementation. There was also a suggestion that the risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) may also be lower in zinc-supplemented patients.

Hepatitis B Virus

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is an even more serious public health problem, with more than 350 million infected people worldwide. Serum zinc levels are significantly decreased in patients with acute hepatitis B infection and are frequently depressed with HBV cirrhosis (similar to HCV cirrhosis).117,118 Specifically designed zinc finger proteins had been used in an attempt to inhibit HBV viral transcription with some success, and this is a potential therapeutic target for new HBV drugs.119 Importantly, marginal zinc deficiency appears to impair the efficacy of hepatitis B vaccination.120 This is another example of how zinc deficiency may impair immune function with special relevance to liver disease.

Zinc and Other Liver Diseases

Wilson Disease

Wilson disease is an autosomal recessive disorder of copper metabolism. Zinc was first used to treat Wilson disease in the Netherlands as early as the 1960s. Zinc acetate was approved for maintenance therapy by the FDA in 1997, based on research that showed that zinc caused a negative copper balance, controlled urine and plasma copper levels, removed stored copper, and protected the liver, at least in part, by inducing the expression of intestinal and hepatic metallothionein.121–123

Metallothionein is mainly a cytosolic peptide with a high cysteine content that binds metals such as zinc and copper quite avidly (copper having a higher affinity). In the cytosol of enterocytes, metallothionein binds newly absorbed copper and prevents it from passing from the intestine into the circulation. Shed enterocytes with copper still bound to metallothionein then result in a high fecal copper content and loss of copper from the body.121–123 The dose that is frequently used for adults with Wilson disease is 50 mg elemental zinc 3 times a day. The multiple dosing regimen is critical to impair copper absorption. Many investigators have also used zinc therapy for primary treatment of Wilson disease. However, recent communications have suggested that some patients are resistant to zinc therapy.124–126 Moreover, compliance is often an issue, especially in asymptomatic patients on long-term therapy.124–126 Thus, if zinc is to be used for Wilson disease therapy (especially primary therapy), careful patient monitoring and documentation of compliance are critical. Zinc therapy is an attractive therapeutic agent because it is inexpensive and relatively nontoxic compared to chelation therapy.

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide and the ninth leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States.127 Its incidence and mortality rates in the United States are increasing. The survival rate continues to be dismal with an overall 5-year survival of only 13%.128 The high mortality is due to late-stage detection of this cancer when most of the therapies available are not effective. Globally, 78% of HCC can be attributed to chronic HBV and chronic HCV viral infection.129 In United States, alcoholism is the most common cause of HCC.130

Several groups have reported decreased serum levels of zinc in HCC patients. In a case-control study comparing patients with HCC, cirrhosis, and benign digestive disease, serum levels of Zn in patients with HCC were significantly lower than in those patients with benign digestive disease and similar to levels in cirrhotic patients.131 Nakayama et al132 reported depressed levels of zinc in patients with chronic hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma compared to healthy volunteers. They also tested the metallothionein levels of these individuals and found that patients with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma had levels significantly lower than those in patients with chronic hepatitis and controls. When levels of zinc in HCC tumor tissue were studied, they were found to be significantly decreased compared to surrounding nontumor tissue, and levels in nontumor tissue were significantly lower than normal liver tissue.133–141 Kubo et al142 investigated metallothionein (MT) levels by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis in resected HCC tumors, surrounding noncancerous but diseased hepatic tissue, and normal liver tissue obtained from autopsies done on patients with no liver disease. They found that MT existed mainly as Zn-MT in normal hepatic tissue, whereas in the noncancerous parenchyma surrounding HCC, the Zn-MT was replaced to a significant extent by Cu,Zn-MT. In the cancerous tissue, the Cu,Zn-MT was largely displaced by Cu-MT, and Zn-MT was undetectable.

It is unclear if these changes in serum and tissue zinc concentrations contribute to the initiation or promotion of HCC or whether they are the effects of malignant transformation. Studies are under way to try to elucidate the mechanisms underlying these phenomena. Somewhat conflicting data have emerged. Most recently, Franklin et al143 have reported a downregulation of ZIP14 gene expression and the near absence of the protein within hepatoma cells in core biopsy samples, which could explain the decrease in intracellular zinc levels in HCC. ZIP14 localizes to the cell membrane of normal hepatocytes and is a functional transmembrane transporter involved in the uptake of zinc into the cell.144,145 Thus, its downregulation may explain the decreased zinc levels in hepatoma cells. Because Zn has been proposed to have anticancer properties in multiple systems, the authors suggest that intracellular levels of zinc are downregulated early in HCC to suppress its antitumor effect. The human hepatoma cell line HepG2 does not lose the ZIP14 transporter. Interestingly, exposure of HepG2 cells to even physiologic concentrations of Zn (5 µM) inhibits their growth by about 80%.143 On the other hand, Weaver et al146 observed an upregulation of the zinc transporter ZIP4 gene expression in human and mouse HCC tissue compared with surrounding noncancerous tissue. In fact, ZIP4 protein was rarely found in noncancerous tissue, but it was abundant in the cancerous tissue. They then inhibited ZIP4 in Hepa cells (mouse hepatoma cell line) using a RNAi-expressing lentivirus vector, and this increased apoptosis and modestly slowed progression from G0/G1 to S phase when these cells were released from the hydroxyurea block into the zinc-deficient medium but not in the zinc-adequate medium. Furthermore, migration of these cells through a fibronectin-coated membrane was inhibited.146 Unfortunately, they did not measure zinc levels in these samples, so it is not known how the aberrant expression of ZIP4 in HCC tissue noted in this study affected tumor zinc levels.

Conclusions and General Recommendations

Zinc deficiency occurs in many types of liver disease, especially more advanced/decompensated disease. Zinc supplementation has been best studied in experimental models of ALD where it blocks most mechanisms of liver injury, including increased gut permeability, endotoxemia, oxidative stress, excess TNF production, and hepatocyte apoptosis. Zinc may have some limited antiviral effect in HCV therapy. Importantly, zinc therapy has shown some promising antifibrotic effects in chronic HCV. The dose of zinc we currently administer is 50 mg of elemental zinc (220 mg zinc sulfate) per day orally with a meal. Because of its effects on multiple targets and its relative lack of toxicity, we tend to give zinc long-term (months to years) or at least until the serum zinc level has normalized. Multiple forms of zinc are available, with some of the most widely used including zinc sulfate, zinc gluconate, zinc acetate, zinc picolinate, and others. To our knowledge, zinc acetate is the only zinc supplement requiring a prescription, and extensive information on these supplements, including tablet dosing, is available on the Internet.

Most forms of zinc salts have nausea and epigastric distress as potential side effects. Consuming zinc with a meal or switching types of supplements (eg, switch from zinc sulfate to zinc gluconate or acetate) may lessen these symptoms. We use a once-daily dose of 50 mg elemental zinc to not inhibit copper absorption. In Wilson disease, split doses (usually 50 mg of elemental zinc 3 times per day, separated from meals) are required to cause appropriate reduction in copper burden. Moreover, it appears that some patients may not be zinc responsive, and adherence to therapy and careful monitoring are absolutely critical.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: none reported.

References

- 1.Vallee BL, Wacker WEC, Bartholomay AF, Robin ED. Zinc metabolism in hepatic dysfunction, I: serum zinc concentrations in Laennec’s cirrhosis and their validation by sequential analysis. N Engl J Med. 1956;255:403–408. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195608302550901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vallee BL, Wacker WEC, Batholomay AF, Hoch FL. Zinc metabolism in hepatic dysfunction, II: correlation of metabolic patterns with biochemical findings. N Engl J Med. 1956;257:1056–1065. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195711282572201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahn AM, Helwig HL, Redeker AG, Reynolds TB. Urine and serum zinc abnormalities in disease of the liver. Am J Clin Pathol. 1965;44:426–435. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/44.4.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sullivan JF, Heaney RP. Zinc metabolism in alcoholic liver disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 1970;23:170–177. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/23.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker BE, Dawson JB, Kelleher J, Losowsky MS. Plasma and urinary zinc in patients with malabsorption syndromes or hepatic cirrhosis. Gut. 1973;14:943–948. doi: 10.1136/gut.14.12.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiilerich S, Dietrichson O, Lous FB, et al. Zinc depletion in alcoholic liver diseases. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1980;15:363–367. doi: 10.3109/00365528009181484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McClain CJ, Su L-C. Zinc deficiency in the alcoholic. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1984;7:5–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1983.tb05402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang YJ, Zhou Z. Zinc prevention and treatment of alcoholic liver disease. Mol Aspects Med. 2005;26(4–5):391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J, Pierson RN. Distribution of zinc in skeletal muscle and liver tissue in normal and dietary controlled alcoholic rats. J Lab Clin Med. 1975;85:50–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barak AJ, Beckenhauer HC, Kerrigah FJ. Zinc and manganese levels in serum and liver after alcohol feeding and development of fatty cirrhosis in rats. Gut. 1967;8:454–457. doi: 10.1136/gut.8.5.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahn AM, Ozeran RS. Liver and serum zinc abnormalities in rats with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1967;53:193–197. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClain CJ, Antonow DR, Cohen DA, Shedlofsky SI. Zinc metabolism in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1986;10:582–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1986.tb05149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaetke L, McClain CJ, Talwalkar R, Shedlofsky S. Effects of endotoxin on zinc metabolism in human volunteers. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:E952–E956. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.6.E952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McClain CJ, McClain ML, Boosalis MG, Hennig B. Zinc and the stress response. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1993;19(suppl 1):132–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bibi Nitzan Y, Cohen AD. Zinc in skin pathology and care. J Dermatolog Treat. 2006;17(4):205–210. doi: 10.1080/09546630600791434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moynahan EJ. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: a lethal inherited human zinc deficiency disorder. Lancet. 1973;2:399–400. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91772-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wirsching L. Eye symptoms in acrodermatitis enteropathica. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1962;40:567–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1962.tb07832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anonymous. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: hereditary zinc deficiency. Nutr Rev. 1975;33:327–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1975.tb05198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park CH, Lee MJ, Kim HJ, Lee G, Park JW, Cinn YW. Congenital zinc deficiency from mutations of the SLC39A4 gene as the genetic background of acrodermatitis enteropathica. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25(12):1818–1820. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.12.1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClain CJ, Soutor C, Steele N, Levine AS, Silvis SE. Severe zinc deficiency presenting with acrodermatitis during hyperalimentation: diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1980;2:125–131. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198006000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClain CJ. Trace metal abnormalities in adults during hyper-alimentation. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1981;5:424–429. doi: 10.1177/0148607181005005424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ecker RI, Schroeter AL. Acrodermatitis and acquired zinc deficiency. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:937–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weismann K, Roed-Petersen J, Hjorth N, Kopp H. Chronic zinc deficiency syndrome in a beer drinker with a Billroth II resection. Int J Dermatol. 1976;15:757–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1976.tb00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weismann K, Hoyer H, Christensen E. Acquired zinc deficiency in alcoholic liver cirrhosis: report of two cases. Acta Dermat Venereal (Stockh) 1980;60:447–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Najarian DJ, Majarian JS, Rao BK, Pappert AS. Hypozincemia and hyperzincuria associated with necrolytic acral erythema. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:709–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tabibian JH, Gerstenblith MR, Tedford RJ, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Abuav R. Necrolytic acral erythema as a cutaneous marker of hepatitis C: report of two cases and review. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(10):2735–2743. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel U, Loyd A, Patel R, Meehan S, Kundu R. Necrolytic acral erythema. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16(11):15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henkin RI, Patten BM, Re PK, Bronzert DA. A syndrome of acute zinc loss: cerebellar dysfunction, mental changes, anorexia, and taste and smell dysfunction. Arch Neurol. 1975;32(11):745–751. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1975.00490530067006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McClain CJ, Zieve L. Portal systemic encephalopathy, recognition and variation. In: David CS, editor. Problems in Liver Disease. New York, NY: Grune and Stratton; 1979. pp. 162–173. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bismuth M, Funakoshi N, Cadranel JF, Blanc P. Hepatic encephalopathy: from pathophysiology to therapeutic management. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23(1):8–22. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283417567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Butterworth RF. Complications of cirrhosis, III: hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol. 2000;32(1):171–180. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80424-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grngreiff K, Abicht K, Kluge M, et al. Clinical studies on zinc in chronic liver diseases. Z Gastroenterol. 1988;26(8):409–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rahelić D, Kujundzić M, Romić Z, Brkić K, Petrovecki M. Serum concentration of zinc, copper, manganese and magnesium in patients with liver cirrhosis. Coll Antropol. 2006;30(3):523–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rabbani P, Prasad A. Plasma ammonia and liver ornithine transcarbamoylase activity in zinc-deficient rats. Am J Physiol. 1978;235:E203–E206. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.235.2.E203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dejong CH, Deutz NE, Soeters PB. Muscle ammonia and glutamine exchange during chronic liver insufficiency in the rat. J Hepatol. 1994;21:299–307. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Görg B, Qvartskhava N, Bidmon HJ, et al. Oxidative stress markers in the brain of patients with cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2011;54(1):204–215. doi: 10.1002/hep.23656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takuma Y, Nouso K, Makino Y, Hayashi M, Takahashi H. Clinical trial: oral zinc in hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32(9):1080–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van der Rijt CC, Schalm SW, Schat H, Foeken K, DeJong G. Overt hepatic encephalopathy precipitated by zinc deficiency. Gastroenterology. 1991;100(4):1114–1118. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patek AJ, Haig C. The occurrence of abnormal dark adaptation and its relation to vitamin A metabolism in patients with cirrhosis of the liver. J Clin Invest. 1939;18:609–616. doi: 10.1172/JCI101075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abbott-Johnson WJ, Kerlin P, Abiad G, Claque AE, Cuneo RC. Dark adaptation in vitamin A-deficient adults awaiting liver transplantation: improvement with intramuscular vitamin A treatment. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(4):544–548. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.179176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barber C, Brimlow G, Galloway NR, Toghill P, Walt RP. Dark adaptation compared with electrooculography in primary biliary cirrhosis. Doc Ophthalmol. 1989;71(4):397–402. doi: 10.1007/BF00152766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McClain CJ, Van Thiel DH, Parker S, Badzin LK, Gilbert H. Alterations in zinc, vitamin A, and retinol-binding protein in chronic alcoholism: a possible mechanism for night blindness and hypogonadism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1979;3:135–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1979.tb05287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrison SA, Russell RM, Carney EA, Oaks EV. Zinc deficiency: a cause of abnormal dark adaptation in cirrhotics. Am J Clin Nutr. 1978;31:276–281. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/31.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leure-DuPree AE, McClain CJ. The effect of severe zinc deficiency on the morphology of the rat retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1982;23:425–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leure-DuPree AE, Bridges CD. Changes in retinal morphology and vitamin A metabolism as a consequence of decreased zinc availability. Retina. 1982;2(4):294–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cameron JD, McClain CJ. Ocular histopathology of acrodermatitis enteropathica. Br J Ophthalmol. 1986;70:662–667. doi: 10.1136/bjo.70.9.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Essatara MB, Levine AS, Morley JE, McClain CJ. Zinc deficiency and anorexia in rats: normal feeding patterns and stress induced feeding. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1984;32:469–474. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(84)90265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henkin RI, Graziadei PPG, Bradley DF. The molecular basis of taste and its disorders. Ann Int Med. 1969;71:791–819. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-71-4-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reeves PG, O’Dell BL. Short-term zinc deficiency in the rat and self-selection of dietary protein level. J Nutr. 1981;111:375–383. doi: 10.1093/jn/111.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Essatara MB, Levine AS, Morley JE, McClain CJ. Zinc deficiency and anorexia in rats: effect of central administration of norepinephrine, muscimol and bromergocryptine. Pharmacol Biochem Bheav. 1984;32:479–482. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(84)90267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bettger WJ, O’Dell BL. A critical physiological role of zinc in the structure and function of biomembranes. Life Sci. 1981;28:1625–1638. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90374-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mendenhall CL, Anderson S, Weesner RE, Goldberg SJ, Crolic KA. Protein-calorie malnutrition associated with alcoholic hepatitis. Am J Med. 1984;76:211–222. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90776-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Antonow DR, McClain CJ. Nutrition and alcoholism. In: Tarter RE, Thiel DH, editors. Alcohol and the Brain. New York, NY: Plenum; 1984. pp. 81–120. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burch RE, Sackin DA, Ursick JA, Jetton MM, Sullivan JR. Decreased taste and smell acuity in cirrhosis. Arch Int Med. 1978;138:743–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith FR, Henkin RI, Dell RB. Disordered gustatory acuity in liver disease. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:568–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prasad AS. Impact of the discovery of human zinc deficiency on health. J Am Coll Nutr. 2009;28(3):257–265. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2009.10719780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Thiel DH, Gavaler JS, Schade RR. Liver disease and the hypothalamic pituitary gonadal axis. Semin Liver Dis. 1985;5:35–45. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1041756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McClain CJ, Gavaler JS, Van Thiel DH. Hypogonadism in the zinc-deficient rat: localization of the functional abnormalities. J Lab Clin Med. 1984;104:1007–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abbasi AA, Prasad AS, Ortega J, Congco E, Oberleas D. Gonadal function abnormalities in Sickle cell anemia: studies in adult male patients. Ann Int Med. 1976;85:601–605. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-85-5-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prasad AS, Mantzoros CS, Beck FW, Hess JW, Brewer GJ. Zinc status and serum testosterone levels of healthy adults. Nutrition. 1996;12(5):344–348. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(96)80058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kumari D, Nair N, Bedwal RS. Effect of dietary zinc deficiency on testes of Wistar rats: morphometric and cell quantification studies. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2010;25(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Croxford TP, McCormick NH, Kelleher SL. Moderate zinc deficiency reduces testicular Zip6 and Zip10 abundance and impairs spermatogenesis in mice. J Nutr. 2011;141(3):359–365. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.131318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pories WJ, Henzel JH, Rob CG, Strain WH. Acceleration of healing with zinc sulfate. Ann Surg. 1967;167:432–436. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196703000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hallböök T, Lanner E. Serum-zinc and healing of venous leg ulcers. Lancet. 1972;2(7781):780–782. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)92143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sandstead HH, Lanier VC, Jr, Shephard GH, Gillespie DD. Zinc and wound healing. Am J Clin Nutr. 1970;23:514–519. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/23.5.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Watanabe T, Arakawa T, Fukuda T, Higushi K, Kobayashi K. Zinc deficiency delays gastric ulcer healing in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40(6):1340–1344. doi: 10.1007/BF02065548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cherian MG, Kang YJ. Metallothionein and liver cell regeneration. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2006;231(2):138–144. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oliver JR, Mara TW, Cherian MG. Impaired hepatic regeneration in metallothionein-I/II knockout mice after partial hepatectomy. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2005;230(1):61–67. doi: 10.1177/153537020523000108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weston WL, Hutt JC, Humbert JR, Hambidge KM, Neldner KH, Walravens PA. Zinc correction of defective chemotaxis in acrodermatitis enteropathica. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:422–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Golden MHN, Jackson AA, Golden BE. Effect of zinc on thymus of recently malnourished children. Lancet. 1977;2:1057–1059. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)91888-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Allen JI, Kay NE, McClain CJ. Severe zinc deficiency in humans: association with a reversible T-lymphocyte dysfunction. Ann Int Med. 1981;95:154–157. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-95-2-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.John E, Laskow TC, Buchser WJ, et al. Zinc in innate and adaptive tumor immunity. J Trans Med. 2010;8:118–134. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lichten LA, Cousins RJ. Mammalian zinc transporters: nutritional and physiologic regulation. Annu Rev Nutr. 2009;29:153–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-033009-083312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Prasad AS. Zinc in human health: effect of zinc on immune cells. Mol Med. 2008;14(5–6):353–357. doi: 10.2119/2008-00033.Prasad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bao S, Liu M-J, Lee B, et al. Zinc modulates the innate immune response in vivo to polymicrobial sepsis through regulation of NF-kappaB. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;298(6):L744–L754. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00368.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wong HR, Shanley TP, Sakthivel B, et al. Genome-level expression profiles in pediatric septic shock indicate a role for altered zinc homeostasis in poor outcome. Physiol Genomics. 2007;30:146–155. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00024.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fukada T, Yamasaki S, Nishida K, Murakami M, Hirano T. Zinc homeostasis and signaling in health and disease. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2011;16(7):1123–1134. doi: 10.1007/s00775-011-0797-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang X, Zhou B. Dietary zinc absorption: a play of Zips and ZnTs in the gut. Life. 2010;62(3):176–182. doi: 10.1002/iub.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.King JC. Zinc: an essential but elusive nutrient. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(suppl):679S–684S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.005744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim WR, Brown RS, Jr, Terrault NA, El-Serag H. Burden of liver disease in the United States: summary of a workshop. Hepatology. 2002;36:227–242. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beier JI, Arteel GE, McClain CJ. Advances in alcoholic liver diseases. Curr Gastrol Rep. 2011;13(1):56–64. doi: 10.1007/s11894-010-0157-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Beier JI, McClain CJ. Mechanisms and cell signaling in alcoholic liver disease. Biol Chem. 2010;391(11):1249–1264. doi: 10.1515/BC.2010.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Purohit V, Bode JC, Bode C, et al. Alcohol, intestinal bacterial growth, intestinal permeability to endotoxin, and medical consequences: summary of a symposium. Alcohol. 2008;42:349–361. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.03.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Godde HF, Kelleher J, Walker BE. Relation between zinc status and hepatic functional reserve in patients with liver disease. Gut. 1990;31:694–697. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.6.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rodriguez-Moreno F, Gonzalez-Reimers E, Santolaria-Fernandez F, et al. Zinc, copper, mangan3ese, and iron in chronic alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol. 1997;14:39–44. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(96)00103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhong W, Zhao Y, McClain CJ, Kang YJ, Zhou Z. Inactivation of hepatocyte nuclear factor-4 {alpha} mediates alcohol-induced down-regulation of intestinal tight junction proteins. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299(3):G645–G651. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00515.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kang X, Liu J, Zhong W, et al. Zinc supplementation reverses alcoholic steatosis in mice through reactivating hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha and peroxisome proliferators activated receptor-alpha. Hepatology. 2009;50(4):1241–1250. doi: 10.1002/hep.23090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhou Z, Kang X, Jiang Y, et al. Preservation of hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha is associated with zinc protection against TNF-alpha hepatotoxicity in mice. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2007;232(5):622–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kang X, Song Z, McClain CJ, Kang YJ, Zhou Z. Zinc supplementation enhances hepatic regeneration by preserving hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha in mice subjected to long-term ethanol administration. Am J Pathol. 2008;172(4):916–925. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhou Z, Liu J, Song Z, McClain CJ, Kang YJ. Zinc supplementation inhibits hepatic apoptosis in mice subjected to long-term ethanol exposure. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;223(5):540–548. doi: 10.3181/0710-RM-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bjarnason I, Peters TJ, Wise RJ. The leaky gut of alcoholism: possible route of entry for toxic compounds. Lancet. 1982;1(8370):179–182. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Keshavarzian A, Fields JZ, Vaeth J, Holmes EW. The differing effects of acute and chronic alcohol on gastric and intestinal permeability. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:2205–2211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Keshavarzian A, Choudhary S, Holmes EW, et al. Preventing gut leakiness by oats supplementation ameliorates alcohol-induced liver damage in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:442–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Parlesak A, Schafer C, Schutz T, Bode JC, Bode C. Increased intestinal permeability to macromolecules and endotoxemia in patients with chronic alcohol abuse in different stages of alcohol-induced liver disease. J Hepatol. 2000;32:742–747. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80242-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Enomoto N, Takei Y, Hirose M, et al. Thalidomide prevents alcoholic liver injury in rats through suppression of Kupffer cell sensitization, and TNF-alpha production. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:291–300. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Forsyth CB, Farhadi A, Jakate SM, Tang Y, Shaikh M, Keshavarzian A. Lactobacillus GG treatment ameliorates alcohol-induced intestinal oxidative stress, gut leakiness, and liver injury in a rat model of alcoholic steatohepatitis. Alcohol. 2009;43:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Keshavarzian A, Choudhary S, Holmes DW, et al. Preventing gut leakiness by oats supplementation ameliorates alcohol-induced liver damage in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:442–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Keshavarzian A, Farhadi A, Forsyth CB, et al. Evidence that chronic alcohol exposure promotes intestinal oxidative stress, intestinal hyperpermeability and endotoxemia prior to development of alcoholic steatohepatitis in rats. J Hepatol. 2009;50:538–547. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lambert JC, Zhou Z, Wang L, Song Z, McClain CJ, Kang YJ. Prevention of alterations in intestinal permeability is involved in zinc inhibition of acute ethanol-induced liver damage in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:880–886. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.047852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhong W, McClain CJ, Cave M, Kang YJ, Zhou Z. The role of zinc deficiency in alcohol-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298(5):G625–G633. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00350.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhou Z, Wang L, Song Z, Saari JT, McClain CJ, Yang YJ. Zinc supplementation prevents alcoholic liver injury in mice through attenuation of oxidative stress. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1681–1690. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62478-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zarski JP, Arnaud J, Labadie H, Beaugrand M, Favier A, Rachail M. Serum and tissue concentrations of zinc after oral supplementation in chronic alcoholics with or without cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1987;11:856–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bianchi GP, Marchesini G, Brizi M, et al. Nutritional effects of oral zinc supplementation in cirrhosis. Nutr Res. 2000;20:1079–1089. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rosen HR. Chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2429–2438. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1006613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Grüngreiff K, Reinhold D. Zinc: a complementary factor in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Mol Med Report. 2010;3(3):371–375. doi: 10.3892/mmr_00000267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Moneib HA, Salem SA, Darwish MM. Evaluation of zinc level in skin of patients with encrolytic acral erythema. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(3):476–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Himoto T, Hosomi N, Nakai S, et al. Efficacy of zinc administration in patients with hepatitis C virus-related chronic liver disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42(9):1078–1087. doi: 10.1080/00365520701272409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kalkan A, Bulut V, Avci S, Celik I, Bingol NK. Trace elements in viral hepatitis. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2002;16(4):227–230. doi: 10.1016/S0946-672X(02)80049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yuasa K, Naganuma A, Sato K, et al. Zinc is a negative regulator of hepatitis C virus RNA replication. Liver Int. 2006;26(9):1111–1118. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Takagi H, Nagamine T, Abe T, et al. Zinc supplementation enhances the response to interferon therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 2001;8(5):367–371. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2001.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nagamine T, Takagi H, Takayama H, et al. Preliminary study of combination therapy with interferon-alpha and zinc in chronic hepatitis C patients with genotype 1b. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2000;75(1–3):53–63. doi: 10.1385/BTER:75:1-3:53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kim KI, Kim SR, Sasase N, et al. Blood cell, liver function, and response changes by PEG-interferon-alpha2b plus ribavirin with polaprezinc therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatol Int. 2008;2(1):111–115. doi: 10.1007/s12072-007-9029-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ko WS, Guo CH, Hsu GS, Chiou YL, Yeh MS, Yaun SR. The effect of zinc supplementation on the treatment of chronic hepatitis C patients with interferon and ribavirin. Clin Biochem. 2005;38(7):614–620. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Murakami Y, Koyabu T, Kawashima A, et al. Zinc supplementation prevents the increase of transaminase in chronic hepatitis C patients during combination therapy with pegylated interferon alpha-2b and ribavirin. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2007;53(3):213–218. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.53.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Suzuki H, Takagi H, Sohara N, et al. Gumma Liver Study Group. Triple therapy of interferon and ribavirin with zinc supplementation for patients with chronic hepatitis C: a randomized controlled clinical trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(8):1265–1269. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i8.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Matsuoka S, Matsumura H, Nakamura H, et al. Zinc supplementation improves the outcome of chronic hepatitis C and liver cirrhosis. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2009;45(3):292–303. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.08-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Fota-Markowska H, Przybyla A, Borowicz I, Modrzewska R. Serum zinc (Zn) level dynamics in blood serum of patients with acute viral hepatitis B and early recovery period. Ann Univ Mariae Curie Sklodowska Med. 2002;57(2):201–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ozbal E, Helvaci M, Kasirga E, Akdenizoğlu F, Kizilgvneş ler A. Serum zinc as a factor predicting response to interferon-alpha2b therapy in children with chronic hepatitis B. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2002;90(1–3):31–38. doi: 10.1385/BTER:90:1-3:31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hoeksema KA, Tyrrell DL. Inhibition of viral transcription using designed zinc finger proteins. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;649:97–116. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-753-2_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ozgenc F, Aksu G, Kirkpinar F, et al. The influence of marginal zinc deficient diet on post-vaccination immune response against hepatitis B in rats. Hepatol Res. 2006;35(1):26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hoogenraad TU. Paradigm shift in treatment of Wilson’s disease: zinc therapy now treatment of choice. Brain Dev. 2006;28(3):141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Brewer GJ, Dick RD, Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan V, Johnson V, Wang Y. Treatment of Wilson’s disease with zinc, XIII: therapy with zinc in presymptomatic patients from the time of diagnosis. J Lab Clin Med. 1994;123(6):849–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Huster D. Wilson disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24(5):531–539. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Weiss KH, Gotthardt DN, Klemm D, et al. Zinc monotherapy is not as effective as chelating agents in treatment of Wilson Disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1189–1198. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Schilsky M. Zinc treatment for symptomatic Wilson disease: moving forward by looking back. Hepatology. 2009;50(5):1341–1343. doi: 10.1002/hep.23355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Roberts EA. Zinc toxicity: from “no, never” to “hardly ever”. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(4):1132–1135. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hepatocellular carcinoma—United States, 2001–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(17):517–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Reichman ME. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States from 1975 to 2005. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1485–1491. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJ, Bell BP. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. J Hepatol. 2006;45:529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Morgan TR, Mandayam S, Jamal MM. Alcohol and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S87–S96. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Poo JL, Rosas-Romero R, Montemayor AC, Isoard F, Uribe M. Diagnostic value of the copper/zinc ratio in hepatocellular carcinoma: a case control study. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(1):45–51. doi: 10.1007/s005350300005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Nakayama A, Fukuda H, Ebara M, Hamasaki H, Nakajima K, Sakurai H. A new diagnostic method for chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma based on serum metallothionein, copper, and zinc levels. Biol Pharm Bull. 2002;25(4):426–431. doi: 10.1248/bpb.25.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Tashiro H, Kawamoto T, Okubo T, Koide O. Variation in the distribution of trace elements in hepatoma. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2003;95(1):49–63. doi: 10.1385/BTER:95:1:49. [PMID: 14555799] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Maeda T, Shimada M, Harimoto N, et al. Role of tissue trace elements in liver cancers and non-cancerous liver parenchyma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52(61):187–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Danielsen A, Steinnes E. A study of some selected trace elements in normal and cancerous tissue by neutron activation analysis. J Nucl Med. 1970;11:260–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ebara M, Fukuda H, Hatano R, et al. Relationship between copper, zinc and metallothionein in hepatocellular carcinoma and its surrounding liver parenchyma. J Hepatol. 2000;33:415–422. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Liaw KY, Lee PH, Wu FC, Tsai JS, Lin-Shiau SY. Zinc, copper, and superoxide dismutase in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2260–2263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Tashiro H, Kawamoto T, Okubo T, Koide O. Variation in the distribution of trace elements in hepatoma. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2003;95:49–63. doi: 10.1385/BTER:95:1:49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Tashiro-Itoh T, Ichida T, Matsuda Y, et al. Metallothionein expression and concentrations of copper and zinc are associated with tumor differentiation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver. 1997;17:300–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1997.tb01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Gurusamy K, Davidson BR. Trace element concentration in metastatic liver disease: a systematic review. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2007;21:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Al-Ebraheem A, Farquharson MJ, Ryan E. The evaluation of biologically important trace metals in liver, kidney and breast tissue. Appl Radiat Isot. 2009;67:470–474. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Kubo S, Fukuda H, Ebara M, et al. Evaluation of distribution patterns for copper and zinc in metallothionein and superoxide dismutase in chronic liver diseases and hepatocellular carcinoma using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28(7):1137–1141. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Franklin RB, Levy BA, Zou J, et al. ZIP14 zinc transporter downregulation and zinc depletion in the development and progression of hepatocellular cancer. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2011 Mar 5; doi: 10.1007/s12029-011-9269-x. [Epub ahead of print] [PMID: 21373779] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Taylor KM, Morgan HE, Johnson A, Nicholson RI. Structure-function analysis of a novel member of the LIV-1 subfamily of zinc transporters, ZIP14. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:427–432. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Franklin RB, Costello LC. Zinc as an anti-tumor agent in prostate cancer and in other cancers. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;463:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Weaver BP, Zhang Y, Hiscox S, et al. Zip4 (Slc39a4) expression is activated in hepatocellular carcinomas and functions to repress apoptosis, enhance cell cycle and increase migration. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013158. [PMID: 20957146] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]