Abstract

Background/Aims

Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 21 is associated with hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. However, little is known regarding the effects of inflammation and fibrosis on the β-Klotho and FGF21 pathway in the liver.

Methods

Enrolled patients had biopsy-confirmed viral or alcoholic hepatitis. FGF19, FGF21 and β-Klotho levels were evaluated using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, real-time polymerase chain reaction, and Western blotting. Furthermore, we explored the underlying mechanisms for this process by evaluating nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway involvement in Huh-7 cells.

Results

We observed that the FGF19 and FGF21 serum and mRNA levels in the biopsied liver tissue gradually increased and were correlated with fibrosis stage. Inflammatory markers (interleukin 1β [IL-1β], IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α) were positively correlated, while β-Klotho expression was negatively correlated with the degree of fibrosis. In Huh-7 cells, IL-1β increased FGF21 levels and decreased β-Klotho levels. NF-κB and JNK inhibitors abolished the effect of IL-1β on both FGF21 and β-Klotho expression. FGF21 protected IL-1β-induced growth retardation in Huh-7 cells.

Conclusions

These results indicate that the inflammatory response during fibrogenesis increases FGF21 levels and suppresses β-Klotho via the NF-κB and JNK pathway. In addition, FGF21 likely protects hepatocytes from hepatic inflammation and fibrosis.

Keywords: Fibroblast growth factor 21, β-Klotho, Interleukin-1beta, NF-kappa B, JNK

INTRODUCTION

The fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 19 subfamily includes FGF19, FGF21, and FGF23. FGF19 subfamily members have a poor affinity for the classic heparin-binding domain,1 whereas most FGFs bind to and activate cell surface FGF receptors (FGFRs) via a high affinity interaction with heparin.2,3 This difference makes the conventional FGFs function in a paracrine/autocrine manner to induce cell proliferation and differentiation; however, members of the FGF19 subfamily are secreted into the bloodstream and function as hormones.1,2,4 FGF19 subfamily members require a coreceptor named Klotho to activate FGFRs due to their low affinity for heparin sulfate.1,5,6 Klotho is a transmembrane protein family whose members take one of two forms, α-Klotho and β-Klotho.7 β-Klotho enables FGF19 and FGF21 binding to FGFR1c, -2c, -3c and FGF19 binding to FGFR4.5,6,8

Many studies have revealed that the FGF19 subfamily is involved in various biological activities. FGF19 regulates the enterohepatic circulation of bile acid, and FGF21 regulates glucose and lipid metabolism.9 FGF23 is important for maintaining phosphate/vitamin D homeostasis.9 Among the FGF19 subfamily, FGF19 and FGF21 are known to have a role in the liver. Both β-Klotho and FGFR4 are highly expressed in the liver. This distinct feature allows FGF19 to act primarily on the liver.5,6 FGF19 is found in the liver of patients with cholestasis10 and is highly expressed in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.11 FGF21 is primarily expressed in the liver, white and brown adipose tissue, and the pancreas.12 FGF21 is increased in several liver diseases, such as alcoholic liver disease, viral hepatitis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.13–15 Recently, a few studies have shown that FGF19 and FGF21 are related to hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. However, little is known as to how FGF19, FGF21, and β-Klotho are regulated in hepatic inflammation and fibrosis.

In our study, we evaluated the levels of FGF19, FGF21, and β-Klotho according to severity of liver fibrosis in human samples. In addition, we tried to find pathways through which β-Klotho and FGF21 are regulated by hepatic inflammation in Huh-7 cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients

Liver biopsies and blood samples were obtained (n=35) from patients suspected to have fibrosis. Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of enrolled patients. Patients between 19 and 65 years of age with biopsy proven viral hepatitis or alcoholic hepatitis who visited Wonju Severance Christian Hospital between December 2008 and December 2012 were recruited for this study. Fibrosis level was determined by an expert pathologist and was classified as F0, F1, F2, F3, F4A, F4B, and F4C according to the Laennec fibrosis scoring system (Supplementary Table 1). We grouped these into three classes of G1 (F0 and F1), G2 (F2 and F3), and G3 (F4a to F4c). Liver biopsies and blood samples were collected, immediately snap-frozen, and stored at −80°C until analysis. This protocol was approved by the International Review Board for Human Research (CR107059) of Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine. Written consent was received from all patients.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristic | G1 (n=10) | G2 (n=10) | G3 (n=15) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male/female | 6/4 | 7/3 | 12/3 | 0.451 |

| Age, yr | 46 (19–63) | 50.5 (37–65) | 51 (24–70) | 0.331 |

| Etiology | 0.562 | |||

| Viral | 4 (40) | 6 (60) | 9 (60) | |

| Alcohol | 6 (60) | 4 (40) | 6 (40) | |

| AST, U/L | 65.5 (42–350) | 58.5 (24–146) | 40 (17–202) | 0.237 |

| ALT, U/L | 101 (47–312) | 58.5 (13–185) | 22 (9–338) | 0.002 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.4 (3.8–4.8) | 4.1 (3.3–4.9) | 3.4 (2.3–4.9) | 0.003 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.6 (0.3–1.4) | 0.6 (0.3–1.0) | 1.2 (0.3–17.2) | 0.013 |

| INR | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 1.0 (0.8–1.1) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | <0.001 |

| Child-Pugh score | 5 | 5 (5–6) | 7 (5–10) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as median (range) or number (%).

AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase; INR, international normalized ratio.

2. Determination of serum FGF19 and FGF21

Serum samples were stored at −80°C until analysis. Quantification of human FGF19 and FGF21 levels was performed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (BioVendor, Brno, Czech Republic), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance of each well was measured at a 450 nm wavelength using a microplate reader ELX 800 (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

3. Cell culture

Human hepatoma Huh-7 cells were cultured in DMEM (GibcoBRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were starved in serum-free medium for 12 hours before being treated with interleukin 1β (IL-1β; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), NK-κB inhibitor (Bay 11-7082; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) inhibitor (SP600125, Sigma-Aldrich), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) inhibitor (LY294002, Sigma-Aldrich), mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MAPKK) inhibitor (PD98059, Sigma-Aldrich), and FGF21 (R&D Systems).

4. Cell proliferation and MTT assay

Huh-7 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1×104 cells/well. Twenty-four hours later, IL-1β-treated cells (1 ng/mL) were cultured with or without FGF21 in a dose-dependent manner for 24 hours, and then methylthiazolyldiphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in PBS was added to each well (final 5 mg/mL) and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. MTT formazan was dissolved in 100 μL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and incubated for a further 15 minutes with shaking before the optical density of each well was analyzed at 570 nm on a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc.).

5. RNA isolation and real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from liver specimens using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific Life Sciences, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In addition, total RNA was isolated from Huh-7 cells using the Pure Link RNA mini kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). RNA purity and concentration were determined using a spectrophotometer (Ultrospec 2100 pro UV/Visible; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). cDNA was synthesized from total RNA (1 μg) using the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (TAKARA). Transcript levels were measured by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using sequence-specific primers for FGF19, FGF21, IL-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and β-Klotho (Supplementary Table 2). Amplification reactions contained SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and were performed in an ABI PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were analyzed using SDS 2.2.2 software (Applied Biosystems). The cycle threshold (Ct) values of the target genes were normalized to those of the endogenous control gene (GAPDH). Relative changes were calculated using the equation 2−ΔΔCt.

6. Western blotting

Huh-7 was lysed in 1X Laemmli sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 1% SDS, 10% glycerol, and 5% β-mercaptoethanol) and boiled for 5 minutes. The lysates were subjected to Western blotting analysis under reducing conditions using previously validated human β-Klotho antibodies (R & D Systems), anti-phospho-Erk1/2, total Erk1/2, phospho-AKT, total AKT, phospho-JNK, and total JNK antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), phospho-IκBα, total IκBα, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), and GAPDH antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and FGF21 antibody (Boster Biological Technology, Pleasanton, CA, USA).

7. Statistical analysis

All values are presented as mean±standard error of the mean. Data were analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis H test and the Mann-Whitney U test using SPSS software version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Fisher exact test was used for categorical data. Correlation was measured by Spearman rank method. For all analyses, p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

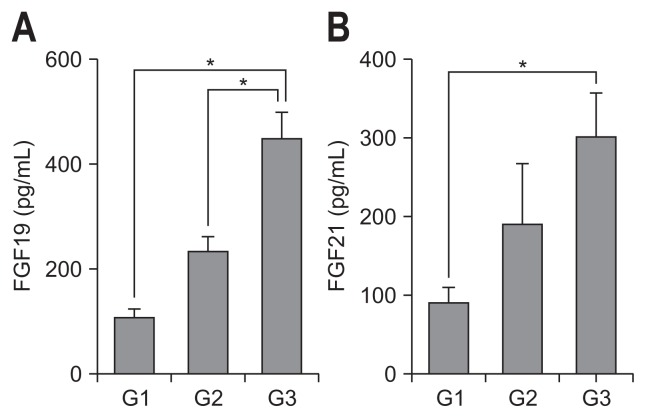

1. Analysis of serum FGF19 and FGF21

The serum levels of FGF19 and FGF21 were significantly increased in cirrhosis (G3 group) compared with G1 and G2 groups (p<0.01) (Fig. 1). We observed that the serum levels of FGF19 and FGF21 were correlated with fibrosis stage in liver biopsies.

Fig. 1.

Analysis of serum FGF19 and FGF21 levels in patients with viral or alcoholic hepatitis. Serum levels of FGF19 (A) and FGF21 (B) were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. G1 (F0–F1, n=10), G2 (F2–F3, n=10), G3 (F4A–F4C, n=15).

FGF, fibroblast growth factor. *p<0.01.

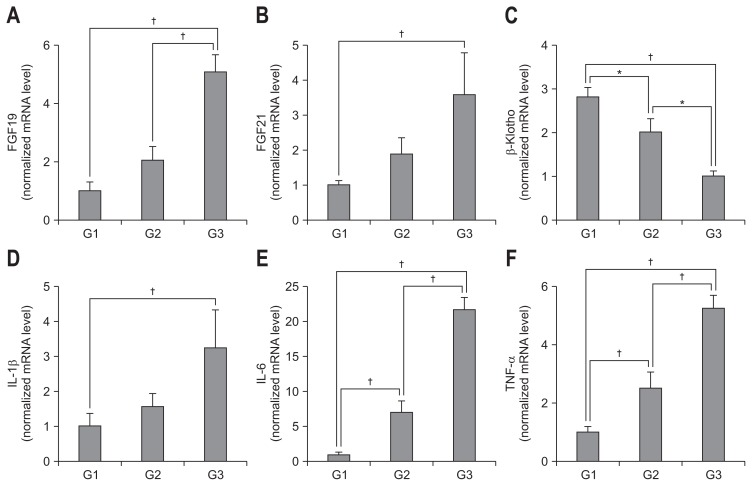

2. Analysis of FGF19, FGF21, β-Klotho, and inflammatory markers in liver tissue

FGF19 and FGF21 mRNA levels were significantly increased and associated with fibrosis stage (p<0.01) (Fig. 2A and B), whereas β-Klotho level was significantly decreased and associated with fibrosis stage (p<0.01) (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, inflammatory markers IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were positively correlated with degree of fibrosis (p<0.01) (Fig. 2D–F). The mRNA levels of FGF19, FGF21 and inflammatory markers were positively correlated with fibrosis stage and that of β-Klotho was negatively correlated with fibrosis stage (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of FGF19, FGF21, and β-Klotho expression and inflammatory markers in liver tissue. Expression levels of mRNA for FGF19 (A), FGF21 (B), β-Klotho (C), IL-1β (D), IL-6 (E), and TNF-α (F) were determined by real-time polymerase chain reaction. G1 (F0–F1, n=10), G2 (F2–F3, n=10), G3 (F4A–F4C, n=15).

FGF, fibroblast growth factor; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor. *p<0.05, †p<0.01.

Table 2.

Correlation between the Fibrosis Stage and mRNA Expression of FGF19/21, β-Klotho, and Inflammatory Markers

| Fibrosis stage | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| R | p-value | |

| FGF19 | 0.739 | <0.001 |

| FGF21 | 0.315 | 0.046 |

| β-Klotho | −0.767 | <0.001 |

| IL-1β | 0.446 | 0.007 |

| IL-6 | 0.887 | <0.001 |

| TNF-α | 0.842 | <0.001 |

Spearman rank method was used.

FGF, fibroblast growth factor; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

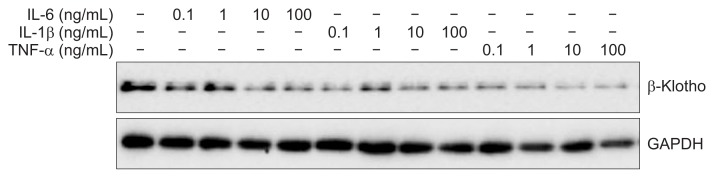

3. Effects of inflammatory cytokines on β-Klotho expression in Huh-7 cells

We investigated the effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α on hepatic β-Klotho expression. All pro-inflammatory cytokines used in this experiment inhibited β-Klotho expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Inflammatory cytokine effects on β-Klotho expression in Huh-7 cells. Huh-7 cells were incubated with increasing amounts of interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) for 6 hours. β-Klotho expression levels were determined by immunoblotting.

GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

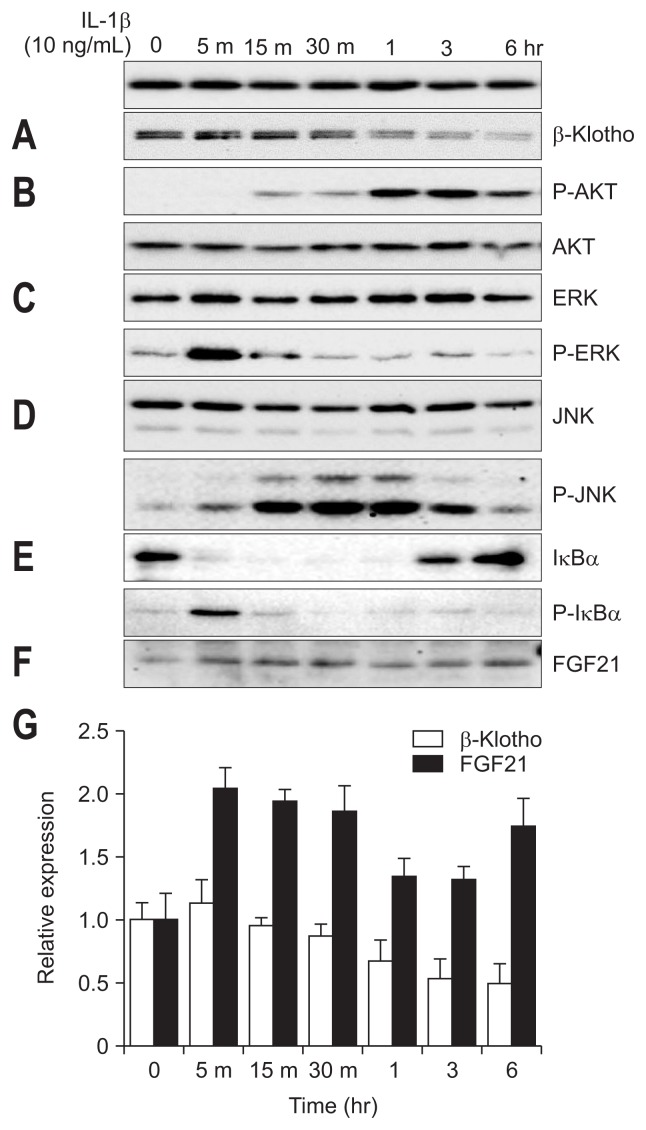

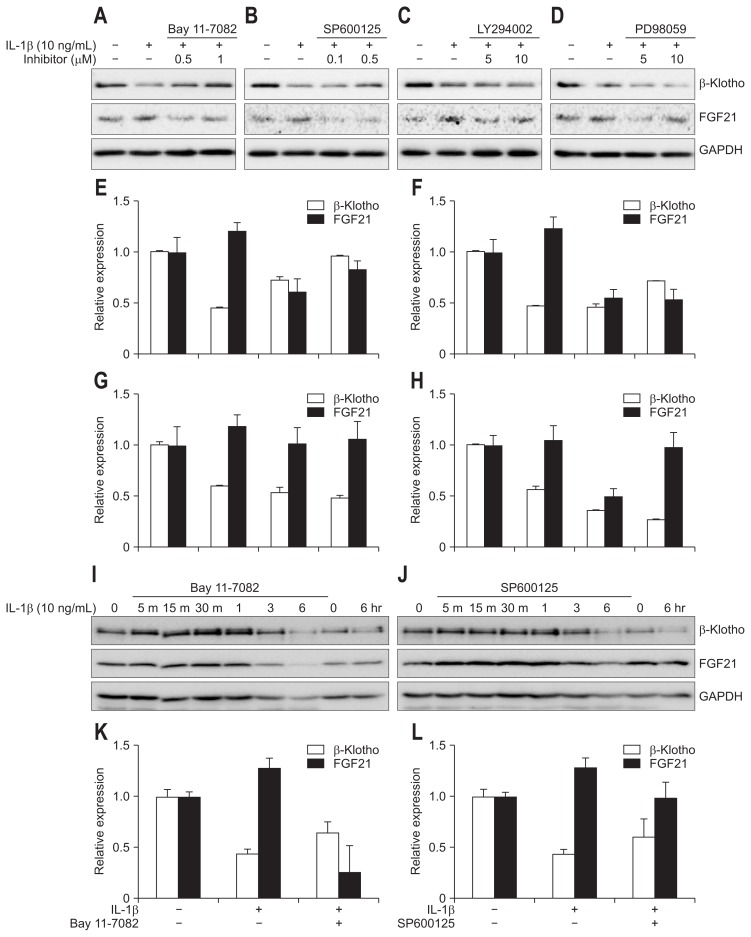

4. Signaling pathways inhibiting β-Klotho by IL-1β in Huh-7 cells

We tried to find the pathways of inhibition of hepatic β-Klotho expression by IL-1β. We incubated Huh-7 cells with IL-1β for 6 hours. IL-1β inhibited β-Klotho expression in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 4A and G). We investigated the effects of IL-1β on inflammatory signaling pathways in Huh-7 cell. IL-1β activated the AKT pathway (Fig. 4B), ERK pathway (Fig. 4C), JNK pathway (Fig. 4D) and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway (Fig. 4E). We then examined which signaling pathway mediates IL-1β-induced suppression of β-Klotho expression. We used NF-κB inhibitor (Bay 11-7082), JNK inhibitor (SP600125), PI3-K inhibitor (LY294002), and MAPKK inhibitor (PD98059). Huh-7 cells were pretreated with these four inhibitors for 20 minutes before being treated with IL-1β. The inhibitory effect of IL-1β on β-Klotho expression was attenuated by the NF-κB inhibitor (Bay 11-7082) in Huh-7 cells (Fig. 5A, E, I, and K). The same results were shown by the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (0.5 and 1 μM) (Fig. 5B, F, J, and L). These results suggest that the NF-κB pathway and the JNK pathway have inhibitory effects on IL-1β action on β-Klotho expression. However, AKT inhibitor (LY294002) and ERK inhibitor (PD98059) have no effect on IL-1β-induced inhibition of β-Klotho (Fig. 5C, D, G, and H).

Fig. 4.

Effects of IL-1β on β-Klotho and FGF21 in Huh-7 cells. Huh-7 cells were incubated with IL-1β for 6 hours. β-Klotho expression levels (A and G), protein kinase B (B), extracelluar signal-regulated kinases (C), JNK (D), IκBα (E), and FGF21 (F and G) were determined by immunoblotting.

IL, interleukin; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase.

Fig. 5.

Signaling pathways that inhibit β-Klotho and induce FGF21 by IL-1β in Huh-7 cells. Huh-7 cells were pretreated with an NF-κB inhibitor (Bay11-7082, A and E), JNK inhibitor (SP600125, B and F), protein kinase B inhibitor (LY294002, C and G), or extracelluar signal-regulated kinases inhibitor (PD98059, D and H) for 20 minutes and then treated with 10 ng/mL of IL-1β for 6 hours to detect β-Klotho and FGF21. (I) Huh-7 cells were pretreated with 1 μM NF-κB inhibitor Bay11-7082, after which β-Klotho and FGF21 levels were determined by immunoblotting. (J) Huh-7 cells were pretreated with 0.5 μM JNK inhibitor SP600125, after which β-Klotho and FGF21 levels were determined by immunoblotting. (K) β-Klotho and FGF21 levels were assessed 6 hours after pretreatment with 1 μM NF-κB inhibitor Bay11-7082 in Huh-7 cells. (L) β-Klotho and FGF21 levels were assessed 6 hours after pretreatment with 0.5 μM JNK inhibitor SP600125 in Huh-7 cells.

FGF, fibroblast growth factor; IL, interleukin; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

5. Effect of IL-1β on FGF21 in Huh-7 cells

We investigated whether FGF21 protein level was increased by IL-1β in Huh-7 cells. We incubated Huh-7 cells with IL-1β for 6 hours. IL-1β increased the expression of FGF21 proteins, reaching the highest level 5 minutes after IL-1β treatment and gradually decreasing (Fig. 4F and G). However, FGF19 was not detected in Huh-7 cells treated with IL-1β. We then examined which signaling pathway mediates IL-1β-induced activation on FGF21 expression. Huh-7 cells were pretreated with Bay11-7082 before being treated with IL-1β. NF-κB inhibitor abolished the effect of IL-1β on FGF21 signaling (Fig. 5A, E, I, and K). Also, JNK inhibitor SP600125 suppressed the effect of IL-1β on FGF21 signaling (Fig. 5B, F, J, and L).

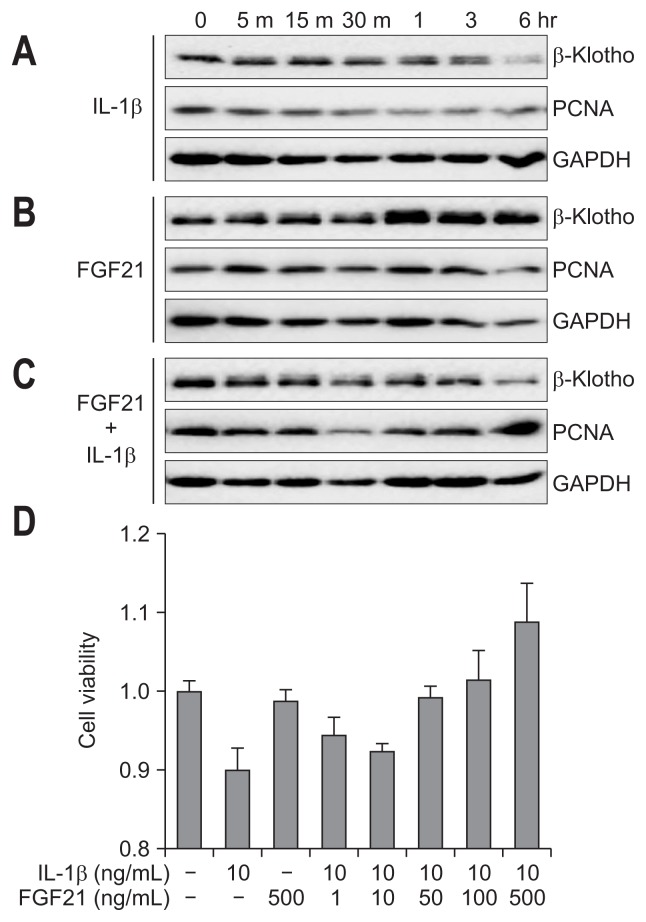

6. FGF21 inhibited IL-1β-induced growth retardation of hepatocytes

Using MTT assay and immunoblotting assay with PCNA as a marker of proliferation, we determined the effects of IL-1β and FGF21 on hepatocyte cell proliferation. Huh-7 cells were treated with IL-1β and/or FGF21. IL-1β decreased PCNA expression in Huh-7 cells in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 6A). FGF21 had no effect on PCNA expression (Fig. 6B). However, when IL-1β was co-treated with FGF21, FGF21 inhibited hepatocyte growth retardation, as determined by immunoblotting and MTT assay (Fig. 6C and D).

Fig. 6.

FGF21 inhibits IL-1β-induced growth retardation of hepatocytes. Huh-7 cells were incubated with 10 ng/mL of IL-1β (A), 500 ng/mL of FGF21 (B), or IL-1β+FGF21 (C), after which the expression of β-Klotho and PCNA was determined. (D) IL-1β-treated Huh-7 cells were incubated with or without FGF21 in a dose-dependent manner. Cell viability was measured by an methylthiazolyldiphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay.

IL, interleukin; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we observed that inflammation and fibrosis increased FGF19 and FGF21 in patients with hepatic fibrosis, with both mRNA and protein levels increasing gradually, whereas mRNA level of β-Klotho was decreased. In Huh-7 cells, pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β inhibited β-Klotho expression but increased FGF21 level. We also showed that IL-1β inhibited FGF21 expression via JNK and NF-κB pathways in Huh-7 cell. FGF21 inhibited growth retardation of hepatocytes induced by IL-1β.

Hepatocyte death or growth suppression is linked to inflammation and hepatic fibrosis.16–19 In patients with chronic viral hepatitis and alcoholic hepatitis, hepatocyte death is the initial disease driver and subsequently triggers inflammation and fibrosis.20–23 Several studies have revealed that pro-inflammatory chemokines and their receptors are positively associated with hepatic fibrogenesis in patients with hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus.16,24,25 In alcoholic hepatitis, Toll-like receptor 4 activation and natural killer cell inhibition caused by chronic ethanol exposure lead to liver inflammation and fibrosis.21,26 In our study, we enrolled patients with viral hepatitis and alcoholic hepatitis. We first verified the relationships between inflammation levels and the degree of hepatic fibrosis using the inflammatory markers IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α. In this regard, the expression of β-Klotho mRNA gradually decreased as the degree of liver inflammation increased. Previous experimental studies have shown that pro-inflammatory cytokines repress β-Klotho expression.27,28 Although heterogeneous etiology is a limitation, this is the first human data to show that the level of β-Klotho was decreased by inflammation and fibrosis.

In this study, we found that the mRNA and protein levels of FGF19 and FGF21 positively increased with the degree of liver inflammation and fibrosis. Consistent with our findings, a recent report has revealed that concentration of FGF19 was increased under cholestatic and cirrhotic conditions as an adaptive hepatic response.10 However, Zhou et al.29 reported that, while protecting the liver, prolonged exposure to FGF19 at a circulating level as low as 20 ng/mL induced hepatocellular carcinoma in mice with targeted disruption of the orthologous multidrug resistance 2 gene. FGF19 is supposed to act as a “double-edged sword” that, on the one hand, acts as an adaptive response to the liver injury and, on the other hand, induces hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver disease. FGF21 is also increased in inflammatory conditions. Patients with sepsis showed a significant elevation of plasma FGF21 level compared to healthy subjects.30 In an endotoxemic mouse model, plasma FGF21 level was also increased.31 Increase in plasma FGF21 level during inflammation might be a protective response as treatment with exogenous FGF21 reduced the rate of death in a septic mouse model.31 Rusli et al.32 reported that plasma FGF21 was negatively correlated with expression of β-Klotho in a non-alcoholic fatty liver disease mouse model. The up-regulated FGF21 level suggests to be the protective response against non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-induced adverse events.32

We also investigated the mechanisms involved in inflammation-induced suppression of β-Klotho expression and increase of FGF21 expression using Huh-7 cells. IL-1β, which is a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine, is related to toxicity-, ethanol-, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis-induced fibrosis.33,34 First, we verified that IL-1β phosphorylates the IκBα pathway and activates the JNK pathway. These pathways produce transcription factors that act as regulators of inflammation and fibrosis.35,36 These two pathways are also the main pathways that transduce IL-1β signaling.37 IL-1β inhibited β-Klotho expression in a time-dependent manner. Zhao et al.27 reported that IL-1β signaling directly inhibits β-Klotho transcription. Simultaneous inhibition of both the NF-κB and JNK inhibitor pathways suppressed the role of IL-1β to inhibit β-Klotho expression. Interestingly, in our study, each NF-κB and JNK inhibitor alone suppressed the ability of IL-1β to inhibit β-Klotho expression.

We further investigated whether IL-1β has an effect on FGF21 expression in Huh-7 cells. FGF21 expression increased after IL-1β treatment. We again applied NF-κB inhibitor or JNK inhibitor to determine whether the NF-κB and JNK pathways affect the inhibitory effect of IL-1β on FGF21 expression. Along with the result of IL-1β on β-Klotho, each inhibitor abolished the ability of IL-1β to increase FGF21 expression. One previous study showed that the JNK pathway is involved in the inhibition of β-Klotho expression and FGF21 signaling by TNF-α in 3T3-L1 adipocytes.28 Our results showed that the NF-κB pathway is also involved in IL-1β induced FGF21 expression.

FGF21 protein is known to be highly expressed in a variety of liver disease, such as viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma.14,15 In the present study, we showed that both mRNA and protein of FGF21 increased with the degree of fibrosis in patients with viral hepatitis and alcoholic liver disease. Furthermore, in Huh-7 cells, IL-1β increased FGF21 expression. Elevation of FGF21 level is thought to be a protective effect in liver disease by removing systemic lipids and enhancing insulin sensitivity.13 In our study, FGF21 inhibited the growth retardation of hepatocytes induced by IL-1β. In this view, FGF21 is considerable as a therapeutic agent for anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrosis roles.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that expression of FGF19 and FGF21 increased in serum and liver tissue in patients with viral hepatitis and alcoholic hepatitis, whereas the expression of β-Klotho decreased. IL-1β inhibited β-Klotho expression via NF-κB and JNK pathways. On the other hand, IL-1β increased FGF21 expression by the NF-κB and JNK pathways. FGF21 showed a protective effect on IL-1β-induced growth retardation of hepatocytes. This mechanism will help to better understand FGF21 signaling and can be applied as a therapeutic agent in inflammatory and fibrotic conditions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI15C2364, HI17C1365), and a Basic Science Research Program and a Medical Research Center Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2017R1D1A1A02019212, -2017R1A5A2015369, -2017R1A2B4009199 and -2016R1A6A3A11932575).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goetz R, Beenken A, Ibrahimi OA, et al. Molecular insights into the klotho-dependent, endocrine mode of action of fibroblast growth factor 19 subfamily members. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3417–3428. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02249-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beenken A, Mohammadi M. The FGF family: biology, pathophysiology and therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:235–253. doi: 10.1038/nrd2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potthoff MJ, Kliewer SA, Mangelsdorf DJ. Endocrine fibroblast growth factors 15/19 and 21: from feast to famine. Genes Dev. 2012;26:312–324. doi: 10.1101/gad.184788.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurosu H, Kuro OM. Endocrine fibroblast growth factors as regulators of metabolic homeostasis. Biofactors. 2009;35:52–60. doi: 10.1002/biof.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin BC, Wang M, Blackmore C, Desnoyers LR. Liver-specific activities of FGF19 require Klotho beta. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27277–27284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704244200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurosu H, Choi M, Ogawa Y, et al. Tissue-specific expression of betaKlotho and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor isoforms determines metabolic activity of FGF19 and FGF21. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:26687–26695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704165200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kharitonenkov A, Dunbar JD, Bina HA, et al. FGF-21/FGF-21 receptor interaction and activation is determined by betaKlotho. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215:1–7. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogawa Y, Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, et al. BetaKlotho is required for metabolic activity of fibroblast growth factor 21. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7432–7437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701600104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukumoto S. Actions and mode of actions of FGF19 subfamily members. Endocr J. 2008;55:23–31. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.KR07E-002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaap FG, van der Gaag NA, Gouma DJ, Jansen PL. High expression of the bile salt-homeostatic hormone fibroblast growth factor 19 in the liver of patients with extrahepatic cholestasis. Hepatology. 2009;49:1228–1235. doi: 10.1002/hep.22771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyeon J, Ahn S, Lee JJ, Song DH, Park CK. Expression of fibroblast growth factor 19 is associated with recurrence and poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1916–1922. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2609-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fon Tacer K, Bookout AL, Ding X, et al. Research resource: comprehensive expression atlas of the fibroblast growth factor system in adult mouse. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:2050–2064. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu WY, Huang S, Shi KQ, et al. The role of fibroblast growth factor 21 in the pathogenesis of liver disease: a novel predictor and therapeutic target. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2014;18:1305–1313. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2014.944898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu C, Gilroy R, Taylor R, et al. Alteration of hepatic nuclear receptor-mediated signaling pathways in hepatitis C virus patients with and without a history of alcohol drinking. Hepatology. 2011;54:1966–1974. doi: 10.1002/hep.24645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang C, Lu W, Lin T, et al. Activation of Liver FGF21 in hepatocarcinogenesis and during hepatic stress. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:67. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seki E, Schwabe RF. Hepatic inflammation and fibrosis: functional links and key pathways. Hepatology. 2015;61:1066–1079. doi: 10.1002/hep.27332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eom YW, Shim KY, Baik SK. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for liver fibrosis. Korean J Intern Med. 2015;30:580–589. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2015.30.5.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim G, Kim MY, Baik SK. Transient elastography versus hepatic venous pressure gradient for diagnosing portal hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2017;23:34–41. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2016.0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim G, Shim KY, Baik SK. Diagnostic accuracy of hepatic vein arrival time performed with contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut Liver. 2017;11:93–101. doi: 10.5009/gnl16031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luedde T, Schwabe RF. NF-kappaB in the liver: linking injury, fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:108–118. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao B, Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1572–1585. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suk KT, Yoon JH, Kim MY, et al. Transplantation with autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for alcoholic cirrhosis: phase 2 trial. Hepatology. 2016;64:2185–2197. doi: 10.1002/hep.28693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim G, Huh JH, Lee KJ, Kim MY, Shim KY, Baik SK. Relative adrenal insufficiency in patients with cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1067–1079. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langhans B, Krämer B, Louis M, et al. Intrahepatic IL-8 producing Foxp3+CD4+ regulatory T cells and fibrogenesis in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2013;59:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao J, Zhang Z, Luan Y, et al. Pathological functions of interleukin-22 in chronic liver inflammation and fibrosis with hepatitis B virus infection by promoting T helper 17 cell recruitment. Hepatology. 2014;59:1331–1342. doi: 10.1002/hep.26916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeong WI, Park O, Gao B. Abrogation of the antifibrotic effects of natural killer cells/interferon-gamma contributes to alcohol acceleration of liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:248–258. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao Y, Meng C, Wang Y, et al. IL-1beta inhibits beta-Klotho expression and FGF19 signaling in hepatocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2016;310:E289–E300. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00356.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Díaz-Delfín J, Hondares E, Iglesias R, Giralt M, Caelles C, Villarroya F. TNF-alpha represses beta-Klotho expression and impairs FGF21 action in adipose cells: involvement of JNK1 in the FGF21 pathway. Endocrinology. 2012;153:4238–4245. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou M, Learned RM, Rossi SJ, DePaoli AM, Tian H, Ling L. Engineered fibroblast growth factor 19 reduces liver injury and resolves sclerosing cholangitis in Mdr2-deficient mice. Hepatology. 2016;63:914–929. doi: 10.1002/hep.28257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gariani K, Drifte G, Dunn-Siegrist I, Pugin J, Jornayvaz FR. Increased FGF21 plasma levels in humans with sepsis and SIRS. Endocr Connect. 2013;2:146–153. doi: 10.1530/EC-13-0040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feingold KR, Grunfeld C, Heuer JG, et al. FGF21 is increased by inflammatory stimuli and protects leptin-deficient ob/ob mice from the toxicity of sepsis. Endocrinology. 2012;153:2689–2700. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rusli F, Deelen J, Andriyani E, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 reflects liver fat accumulation and dysregulation of signalling pathways in the liver of C57BL/6J mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30484. doi: 10.1038/srep30484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gieling RG, Wallace K, Han YP. Interleukin-1 participates in the progression from liver injury to fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G1324–G1331. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90564.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petrasek J, Bala S, Csak T, et al. IL-1 receptor antagonist ameliorates inflammasome-dependent alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3476–3489. doi: 10.1172/JCI60777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luedde T, Kaplowitz N, Schwabe RF. Cell death and cell death responses in liver disease: mechanisms and clinical relevance. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:765–783.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seki E, Brenner DA, Karin M. A liver full of JNK: signaling in regulation of cell function and disease pathogenesis, and clinical approaches. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:307–320. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weber A, Wasiliew P, Kracht M. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) pathway. Sci Signal. 2010;3:cm1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3105cm1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.