Abstract

The major histocompatibility complex class I and class II human leukocyte antigens (HLA) play a central role in adaptive immunity but are also the dominant polymorphic proteins targeted in allograft rejection. Sensitized patients with high levels of panel reactive anti-HLA antibody (PRA) are at risk of early allograft injury, rejection, reduced allograft survival and often experience prolonged waiting times prior to transplantation. Xenotransplantation, using genetically modified porcine organs, offers a unique source of donor organs for these highly sensitized patients if the anti-HLA antibody, which places the allograft at risk, does not also enhance anti-pig antibody reactivity responsible for xenograft rejection. Recent improvements in xenotransplantation efficacy have occurred due to improved immune suppression, identification of additional xenogeneic glycans and continued improvements in donor pig genetic modification. Genetically engineered pig cells, devoid of the known xenogeneic glycans, minimize human antibody reactivity in 90% of human serum samples. For waitlisted patients, early comparisons of patient PRA and anti-pig antibody reactivity found no correlation suggesting that patients with high PRA levels were not at increased risk of xenograft rejection. Subsequent studies have found that some, but not all, highly sensitized patients express anti-HLA class I antibody which crossreacts with swine leukocyte antigen (SLA) class I proteins. Recent detailed antigen specific analysis suggests that porcine specific anti-SLA antibody from sensitized patients binds crossreactive groups present in a limited subset of HLA antigens. This suggests that using modern genetic methods, a program to eliminate specific SLA alleles through donor genetic engineering or stringent donor selection is possible to minimize recipient antibody reactivity even for highly sensitized individuals.

Keywords: xenotransplantation, panel reactive antibody, anti-HLA, xenoreactive antibody, non-Gal antibody

Introduction

The classical major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules are highly polymorphic glycoproteins which play a central role in adaptive immunity by capturing and presenting peptide antigens to the T-cell Receptor (TCR) expressed on T-lymphocytes (1). There are two major classes of human MHC, the Human Leukocyte Antigens (HLA) class I and class II proteins. The class I proteins are expressed widely on nucleated cells and present antigen in association with beta-2-microglobin to TCR on CD8 T-cells. The three major class I loci, A B and C, account for over 12,000 alleles. The HLA class II proteins are expressed on antigen presenting cells (B-cells, dendritic cells and macrophages) and present peptide antigen to CD4 T-cells. There are fewer class II genes with 4,802 listed in the International Immunogenetics and HLA database (IMGT/HLA) (2).

Because of a high level of polymeric amino acid variation, human class I and II proteins have long been recognized as the major transplantation antigens which stimulate allograft organ rejection (3). The majority of amino acid variation occurs in the regions of the proteins which form the peptide binding site for antigen presentation (4). This polymorphism allows for a high diversity of peptide presentation, but also creates antigenic diversity between individuals. Sensitization to HLA gene products occurs as an induced immune response when patients are challenged through blood transfusions, pregnancies or failed organ transplants. For patients awaiting kidney transplantation, sensitization is commonly due to the relatively high frequency of dialysis related blood transfusion. Highly sensitized patients remain longer on the transplant waiting list and when they are transplanted are at higher risk of early graft injury, rejection and reduced graft survival (5, 6).

The efficacy of preclinical xenotransplantation has recently improved with heterotopic pig-to-nonhuman primate (NHP) cardiac xenotransplantation (7–10) now measured in years, encouraging early success in orthotopic cardiac transplantation (11–13) and major improvements in life-supporting renal xenotransplantation (14, 15) with recipient survival beyond 1 year. These results are spurring renewed interest in moving towards clinical xenotransplantation. In addition to increasing the overall supply of organs for transplantation, successful clinical xenotransplantation may be particularly helpful to sensitized patients if increased antibody reactivity to human HLA antigens does not also increase antibody reactivity to porcine donor organs. This review summarizes the literature which has examined the potential of anti-HLA antibody in allo-sensitized patients to crossreact with porcine cells. The body of evidence from these studies suggests that, at the current level of sensitivity, most transplant patients and patients with moderate allo-sensitization show minimal human antibody reactivity to pig cells when these cells lack the three known xenogeneic antigens galactose a 1,3 galactose (aGal), N--glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc) modified glycans and porcine B4GALNT2-dependent SDa glycans (16, 17). For highly sensitized patients, there is often, but not always, an increase in anti-pig antibody reactivity which could affect xenotransplant survival. Recent analysis suggests that stringent patient crossmatching and/or elimination of a limited set of specific porcine class I swine leukocyte antigens (SLA) alleles can further minimize anti-pig reactivity such that future clinical xenotransplantation may be appropriate even for highly sensitized patients.

Detecting HLA Sensitization and Allotransplantation

Early clinical transplantation programs screened donor and recipients for matching blood type but did not routinely screen for evidence of sensitization to other donor antigens. In a landmark study (18) Patel and Terasaki demonstrated that a complement dependent cytoxicity (CDC) test of patients serum against a panel of unrelated donor lymphocytes could be used to detect allo-sensitization. By analysing 248 renal transplants they showed that 80% of recipients with a positive panel reactive antibody (PRA) had immediate graft failure compared to only 2.4% of recipients without a donor specific antibody crossmatch. Adoption of this assay almost completely eliminated hyperacute antibody-mediated allograft rejection and quickly became the early gold standard for detecting donor specific HLA antibodies.

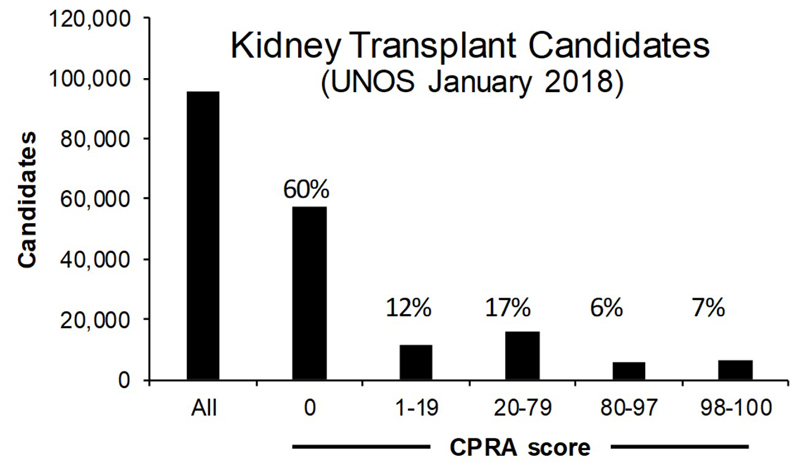

Technical improvements to the CDC assay and development of new assays using flow cytometry (19), solid phase ELISA or single antigen bead assays (20) based on HLA proteins and peptides have further increased sensitivity and specificity for detecting allo-sensitization (21). This led to the current calculated panel reactive antibody (CPRA) score used in kidney allocation which is an estimate of the percent of deceased donors that would be crossmatch incompatible based on the identification of unacceptable HLA antigens and their frequency in a large regional pool of donors. In the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) database there are currently 95,562 kidney transplant candidates on the waiting list (Figure 1). Of these 40% have some degree of sensitization with CPRA > 1. About 31% of sensitized patients however have a CPRA > 80%.

Figure 1.

UNOS data showing the number of kidney transplant candidates on the waiting list and the breakout of patients based on CPRA. There are 95,562 candidates for kidney transplantation listed in January 2018. The percentage values represent the total percentage for each CPRA grouping. 60% of candidates have a CPRC of zero. Within the sensitized patient group (n = 40,128) 31% (n = 12,532) have a CPRA > 80%.

These advanced anti-HLA antibody detection methods have improved donor recipient matching and provided more detailed monitoring and analysis of the immune response in transplant recipients. Most highly sensitized patients produce anti-HLA antibody which reacts with shared public epitopes present on a variety of HLA alleles. It is now clear that these antibodies are binding defined peptide sequences and topographies shared between different HLA proteins. There is sequence homology between human and swine leukocyte antigens (SLA), and some anti-HLA monoclonal antibodies do crossreact with SLA (22). So the question arises, do patients sensitized to HLA antigens also show increased antibody reactivity to porcine cells? If this is the case then xenotransplantation may not be an advantageous source of organs for highly sensitized patients, but, if there is not a concomitant increase in anti-pig antibody in patients with HLA sensitization then xenotransplantation may be an important alternative source of organs for these patients.

Strategies for detecting HLA crossreactivity for Xenotransplantation

Xenograft rejection is recognized as an overwhelmingly antibody driven process due to the very high level of anti-pig antibodies naturally present in human serum. The bulk of these antibodies are not directed to swine SLA but bind to the major xenogeneic glycan galactose alpha 1,3 galactose (αGal) (23). With the advent of pigs engineered with a GGTA-1 mutation (24, 25), which eliminates αGal expression (GTKO), the impact of other antibodies directed to non-Gal antigen including SLA-I has become more apparent (16, 26–28). There have been a limited number of studies designed to determine whether sensitization to HLA results in enhanced antibody reactivity to pig cells (16, 29–37). These studies have been performed over a 20-year period and as such span a range of technological developments both for defining allo-sensitization and in technologies to detect xenoreactive antibody. In this review the studies are presented as four basic research strategies based on the use of whole serum (Type I), anti-Gal depleted serum (Type II) and anti-Gal and anti-Class I depleted serum (Type III). The fourth study type largely used whole human serum but measured patient antibody reactivity to genetically modified porcine cells lacking the three-known xenogeneic glycans (αGal, Neu5Gc modified glycans and SDa) with and without deletion of SLA-I genes.

Type I studies

The earliest study (29) screened 105 waitlisted patient sera against αGal expressing porcine peripheral blood lymphocytes representing the three known haplotypes for NIH miniature swine. They demonstrated that patient PRA, measured by CDC, was not correlated to the level of anti-pig antibody titre. Moreover, most human anti-pig reactivity was IgM whereas anti-HLA was dominantly IgG. Wong et al (35) extended this type of analysis by comparing antibody binding of sensitized patient sera to αGal-positive wild type (WT) and GTKO miniature swine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMNCs). There was a clear reduction in antibody reactivity and CDC to GTKO cells, consistent with the loss of the αGal antigen, but no correlation between antibody reactivity or cytotoxicity to PRA level from 88 waitlisted patient sera for either WT or GTKO cell type. Cytotoxicity to porcine GTKO cells was mainly mediated by IgM antibody in contrast to anti-human cytotoxicity which was predominantly IgG dependent. Similar results were found analysing WT and GTKO pig cells from animals with a commercial agricultural background (Large/White, Landrace, Duroc)(36). A recent study using cells from GTKO and GTKO/CMAHKO pigs expressing human CD46 also failed to find enhanced antibody reactivity in 10 highly sensitized wait listed serum samples (37). Collectively these studies concluded that patients with high PRA sera do not necessarily produce correspondingly high titre of anti-pig antibody or a high levels of anti-pig cytotoxicity. Thus allo-sensitized patients would not be at greater risk of xenograft rejection.

Type II and III studies

Type II studies used porcine red blood cells (RBCs), which do not express SLA-I, to deplete patient serum of anti-Gal antibody and Type III studies used a combination of porcine RBCs and porcine platelets, which do express SLA-I, to deplete both anti-Gal and anti-SLA antibody. When only anti-Gal antibody is depleted, Oostingh et al (33) found that some highly sensitized patient serum shows a correlation between serum PRA and anti-pig antibody reactivity. This study of 82 patient serum samples used both CDC and more sensitive Flow Cross match with class I beads to define PRA levels, identifying 12 samples with 0% PRA, 50 samples with PRA from 11 – 84% and 20 samples with PRA > 84%. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMNCs) from 23 αGal-positive hDAF pigs with known lineage, selected to represent a broad diversity of swine SLA-I, were used as target cells. In the 1884 crossmatch combinations about 20% retained antibody reactivity to porcine PBMNCs after anti-Gal antibody depletion. When the serum samples were stratified for PRA the majority of this αGal-independent crossreactivity was present in serum with PRAs > 64%. Similar results were shown by Varela et al using nontransgenic pig cells (34). These studies concluded that human sera with broad panel reactivity (PRA > 64%) can, but do not always exhibit increased crossreactivity to porcine PBMNCs.

When allo-sensitized waitlisted patient serum is progressively absorbed with RBC and porcine platelets to deplete both anti-Gal and anti-SLA-I, it is evident that the residual αGal-independent antibody reactivity present in some highly sensitized patients reacts with swine SLA. Naziruddin et al (30) demonstrated that affinity purified anti-Gal antibody binding to pig PBMNCs was effectively blocked by saturating levels of the αGal specific lectin GSIB-4 but that antibody reactivity to pig PBMNCs in patients with medium to high PRA was αGal independent. This antibody reactivity was also depleted by porcine platelets and reacted in Western blot to porcine SLA-1 heavy chain. Likewise, platelet depletion was shown by Taylor et al (31) to eliminate antibody reactivity to porcine cells in high PRA patient serum. Importantly, they demonstrated that the loss of antibody binding after platelet absorption was specific, as porcine platelet absorption did not affect allo-specific anti-HLA binding to human cells. Similar results were observed in a unique study of ex vivo porcine kidney perfusion were both anti-Gal and anti-SLA-I antibody was recovered from the perfused organ of some but not all sera plasma samples (32). These absorption studies clearly indicate that some high PRA patient sera exhibits crossreactivity to porcine SLA-I, suggesting that at least some broadly reactive anti-HLA antibody crossreacts to a restricted number of conserved serologic groups, shared between human and porcine MHC class I. It is worth noting that porcine RBCs express the Gal antigen, but, unappreciated at the time of these studies, also express additional xenogeneic glycans. The depletion of additional anti-glycan antibody reactivity may have contributed to the success of detecting crossreactive anti-SLA antibody.

Type IV studies

The most recent studies are based on a series of genetically modified pigs which progressively eliminate expression of the known xenogeneic glycans. Tector and colleagues developed a series of pigs with mutations in GGTA-1, eliminating αGal expression (single knockouts), GGTA-1 and cytidine monophosphate-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase (CMAH) eliminating both αGal and the synthesis of Neu5Gc (double knockouts) and GGTA-1, CMAH, and B4GALNT2 eliminating expression of αGal, Neu5Gc modified glycans and SDa glycans (triple knockout) (16, 38, 39). Human serum shows progressively less antibody reactivity to PBMNCs from these pigs with approximately 60% of 820 waitlisted samples negative for IgG binding and 30% showing only background reactivity for both IgM and IgG when tested on triple knockout cells. Serum samples with residual antibody reactivity were further analysed by absorption with porcine RBCs and used to stain SLA-I positive and SLA-I negative porcine cells. A small subset of waitlisted sera (9 of 119) showed clear SLA-I specific reactivity. A similar SLA-I specific analysis of RBC absorbed serum from patients with PRA >80% identified 13 of 22 with SLA class I specific IgG and 4 of 17 with SLA class I specific IgM. When antibody from highly sensitized serum bound to human and porcine PBMNCs was recovered, single antigen bead analysis demonstrated that porcine specific IgG reactivity was limited to common epitope restricted targets present on a restricted set of HLA-I antigens. These studies confirm earlier reports that some, but not all, highly sensitized patient serum contains SLA-I reactive antibody. Importantly these latest studies identify for the first time the MHC crossreactive groups present on swine SLA-I making possible further genetic modification or selection to eliminate these alleles and minimize antibody reactivity even for highly sensitized patients.

Conclusions

The prospects for clinical xenotransplantation have improved significantly due to recent increases in preclinical nonhuman primate xenograft survival. While the ideal donor organ is not universally defined, and may be different for different organs, it seems likely that donor organs with minimal antigenicity (GGTA1/CMAH/B4GALNT2) which minimize human antibody reactivity will make a prominent contribution. Additional genetic modifications to regulate complement and coagulation may also be used, but inclusion of these human transgenes should not affect antibody reactivity or tissue antigenicity. For most human sera and waitlisted patients with zero to moderate HLA sensitization, there appears to be minimal antibody reactivity to these triple knockout pig cells suggesting that future clinical xenotransplantation will be broadly applicable to most patients. Highly sensitized patients (PRA > 80%) can produce antibody which crossreacts with swine SLA-I, but this is not an obligate condition. Whether the SLA-I crossreactive antibody in highly sensitized patients has immediate impact on xenograft survival will depend on the antibody titre, affinity and level of porcine SLA-I expression. Since recent studies suggest that crossreactive anti-HLA antibody is directed to a limited set of HLA antigens, modern genetic screening and modification methods may be used to select for pigs with minimal antibody reactivity even for highly sensitized patients. Patient crossmatching is a corner stone of successful allotransplantation and will undoubtedly play no less of a role in future clinical xenotransplantation.

Funding Source

MRC: MR/R006393/1

Abbreviations

- αGal

terminal galactose α1,3 galactose glycans

- B4GALNT2

beta-1,4-N-Acetyl-Galactosaminyltransferase 2

- CDC

complement dependent cytoxicity

- CMAH

cytidine monophosphate-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase

- CPRA

calculated panel reactive antibody

- GTKO

GGTA-1 mutated

- HLA

Human Leukocyte Antigens

- IMGT/HLA

International Immunogenetics and HLA database

- MHC

Major Histocompatibility Complex

- Neu5Gc

N-glycolylneuraminic acid

- NHP

nonhuman primate

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- PBMNC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PRA

panel reactive antibody

- RBC

red blood cell

- SDa

glycans with terminal GalNAc β1,4 (Neu5Ac α2,3) Gal β-R groups

- SLA

Swine Leukocyte Antigens

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- WT

standard pigs with functional GGTA-1 alleles

References

- 1.Rudolph MG, Stanfield RL, Wilson IA. How TCRs bind MHCs, peptides, and coreceptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:419–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson J, Mistry K, McWilliam H, Lopez R, Parham P, Marsh SG. The IMGT/HLA database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D1171–1176. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehra NK, Baranwal AK. Clinical and immunological relevance of antibodies in solid organ transplantation. Int J Immunogenet. 2016;43:351–368. doi: 10.1111/iji.12294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reche PA, Reinherz EL. Sequence variability analysis of human class I and class II MHC molecules: functional and structural correlates of amino acid polymorphisms. J Mol Biol. 2003;331:623–641. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00750-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bostock IC, Alberu J, Arvizu A, Hernandez-Mendez EA, De-Santiago A, Gonzalez-Tableros N, et al. Probability of deceased donor kidney transplantation based on % PRA. Transpl Immunol. 2013;28:154–158. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loupy A, Lefaucheur C, Vernerey D, Prugger C, Duong van Huyen JP, Mooney N, et al. Complement-binding anti-HLA antibodies and kidney-allograft survival. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1215–1226. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohiuddin MM, Corcoran PC, Singh AK, Azimzadeh A, Hoyt RF, Jr, Thomas ML, et al. B-cell depletion extends the survival of GTKO.hCD46Tg pig heart xenografts in baboons for up to 8 months. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:763–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03846.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohiuddin MM, Singh AK, Corcoran PC, Hoyt RF, Thomas ML, 3rd, Ayares D, et al. Genetically engineered pigs and target-specific immunomodulation provide significant graft survival and hope for clinical cardiac xenotransplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:1106–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.06.002. discussion 1113-1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohiuddin MM, Singh AK, Corcoran PC, Hoyt RF, Thomas ML, 3rd, Lewis BG, et al. One-year heterotopic cardiac xenograft survival in a pig to baboon model. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:488–489. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohiuddin MM, Singh AK, Corcoran PC, Thomas ML, III, Clark T, Lewis BG, et al. Chimeric 2C10R4 anti-CD40 antibody therapy is critical for long-term survival of GTKO.hCD46.hTBM pig-to-primate cardiac xenograft. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11138. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byrne GW, Du Z, Sun Z, Asmann YW, McGregor CG. Changes in cardiac gene expression after pig-to-primate orthotopic xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2011;18:14–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2010.00620.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGregor CGA, Byrne GW, Vlasin M, Walker RC, Tazelaar HD, Davies WR, Chandrasekaran K, Oehler EA, Boilson BA, Wiseman BS, Logan JS. Cardiac function after preclinical orthotopic cardiac xenotransplanation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:380. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGregor CGA, Davies WR, Oi K, Tazelaar HD, Walker RC, Chandrasekaran K, et al. Recovery of cardiac function after pig-to-primate orthotopic heart transplant. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:205–206. (Abstr 98) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwase H, Hara H, Ezzelarab M, Li T, Zhang Z, Gao B, et al. Immunological and physiological observations in baboons with life-supporting genetically engineered pig kidney grafts. Xenotransplantation. 2017;24 doi: 10.1111/xen.12293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higginbotham L, Mathews D, Breeden CA, Song M, Farris AB, 3rd, Larsen CP, et al. Pre-transplant antibody screening and anti-CD154 costimulation blockade promote long-term xenograft survival in a pig-to-primate kidney transplant model. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:221–230. doi: 10.1111/xen.12166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martens GR, Reyes LM, Butler JR, Ladowski JM, Estrada JL, Sidner RA, et al. Humoral Reactivity of Renal Transplant-Waitlisted Patients to Cells From GGTA1/CMAH/B4GalNT2, and SLA Class I Knockout Pigs. Transplantation. 2017;101:e86–e92. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang ZY, Li P, Butler JR, Blankenship RL, Downey SM, Montgomery JB, et al. Immunogenicity of Renal Microvascular Endothelial Cells From Genetically Modified Pigs. Transplantation. 2016;100:533–537. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel R, Terasaki PI. Significance of the positive crossmatch test in kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1969;280:735–739. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196904032801401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cicciarelli J, Helstab K, Mendez R. Flow cytometry PRA, a new test that is highly correlated with graft survival. Clin Transplant. 1992;6:159–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pei R, Wang G, Tarsitani C, Rojo S, Chen T, Takemura S, et al. Simultaneous HLA Class I and Class II antibodies screening with flow cytometry. Hum Immunol. 1998;59:313–322. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(98)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gebel HM, Bray RA. The evolution and clinical impact of human leukocyte antigen technology. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2010;19:598–602. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32833dfc3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulder A, Kardol MJ, Arn JS, Eijsink C, Franke ME, Schreuder GM, et al. Human monoclonal HLA antibodies reveal interspecies crossreactive swine MHC class I epitopes relevant for xenotransplantation. Mol Immunol. 2010;47:809–815. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper DKC, Good AH, Koren E, Oriol R, Malcolm AJ, Ippolito RM, et al. Identification of alpha-galactosyl and other carbohydrate epitopes that are bound by human anti-pig antibodies: relevance to discordant xenografting in man. Transplant Immunol. 1993;1:198–205. doi: 10.1016/0966-3274(93)90047-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai L, Kolber-Simonds D, Park K-W, Cheong H-T, Greenstein JL, Im G-S, et al. Production of α-1,3-galactosyltransferase knockout pigs by nuclear transfer cloning. Science. 2002;295:1089–1092. doi: 10.1126/science.1068228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phelps CJ, Koike C, Vaught TD, Boone J, Wells KD, Chen SH, et al. Production of alpha 1,3-galactosyltransferase-deficient pigs. Science. 2003;299:411–414. doi: 10.1126/science.1078942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padler-Karavani V, Varki A. Potential impact of the non-human sialic acid N-glycolylneuraminic acid on transplant rejection risk. Xenotransplantation. 2011;18:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2011.00622.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Byrne GW, Stalboerger PG, Du Z, Davis TR, McGregor CG. Identification of new carbohydrate and membrane protein antigens in cardiac xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 2011;91:287–292. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318203c27d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Byrne GW, Du Z, Stalboerger P, Kogelberg H, McGregor CG. Cloning and expression of porcine beta1,4 N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferase encoding a new xenoreactive antigen. Xenotransplantation. 2014;21:543–554. doi: 10.1111/xen.12124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartholomew A, Latinne D, Sachs D, Am J, Gienello P, De Bruyere M, et al. Utility of xenografts: Lack of correlation between PRA and natural antibodies to swine. Xenotransplantation. 1997;4:34–39. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naziruddin B, Durriya S, Phelan D, Duffy BF, Olack B, Smith D, et al. HLA antibodies present in the sera of sensitized patients awaiting renal transplant are also reactive to swine leukocyte antigens. Transplantation. 1998;66:1074–1080. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199810270-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor CJ, Tang KG, Smith SI, White DJ, Davies HF. HLA-specific antibodies in highly sensitized patients can cause a positive crossmatch against pig lymphocytes. Transplantation. 1998;65:1634–1641. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199806270-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barreau N, Godfrin Y, Bouhours J-F, Bignon J-D, Karam G, Leteissier E, et al. Interaction of Anti-HLA antibodies with pig xenoantigens. Transplantation. 2000;69:148–156. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200001150-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oostingh GJ, Davies HFS, Tang KCG, Bradley JA, Taylor CL. Sensitisation to swine leukocte antigens in patients with broadly reactive HLA specific antibodies. American Journal of Transplantation. 2002;2:267–273. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diaz Varela I, Sanchez Mozo P, Centeno Cortes A, Alonso Blanco C, Valdes Canedo F. Cross-reactivity between swine leukocyte antigen and human anti-HLA-specific antibodies in sensitized patients awaiting renal transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2677–2683. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000088723.07259.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong BS, Yamada K, Okumi M, Weiner J, O'malley PE, Tseng YL, et al. Allosensitization does not increase the risk of xenoreactivity to alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout miniature swine in patients on transplantation waiting lists. Transplantation. 2006;82:314–319. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000228907.12073.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hara H, Ezzelarab M, Rood PP, Lin YJ, Busch J, Ibrahim Z, et al. Allosensitized humans are at no greater risk of humoral rejection of GT-KO pig organs than other humans. Xenotransplantation. 2006;13:357–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2006.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Z, Hara H, Long C, Hayato I, Qi H, Macedo C, et al. Immune Responses of Hla-Highly-Sensitized and Nonsensitized Patients to Genetically-Engineered Pig Cells. Transplantation. 2017 doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002060. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Estrada JL, Martens G, Li P, Adams A, Newell KA, Ford ML, et al. Evaluation of human and non-human primate antibody binding to pig cells lacking GGTA1/CMAH/beta4GalNT2 genes. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:194–202. doi: 10.1111/xen.12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang ZY, Martens GR, Blankenship RL, Sidner RA, Li P, Estrada JL, et al. Eliminating Xenoantigen Expression on Swine RBC. Transplantation. 2017;101:517–523. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]