Summary

Background

Therapy targeting Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) with ibrutinib has transformed treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL). Patients who are refractory or relapse after ibrutinib experience poor outcomes. Venetoclax is a selective, orally bioavailable inhibitor of BCL-2 that has activity in heavily-pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory CLL. This phase two, multicentre, open-label study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of venetoclax for patients with CLL refractory to or who relapsed during or after ibrutinib.

Methods

Patients at least 18 years of age were eligible for study enrollment if they required therapy according to criteria from the 2008 International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (iwCLL), had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score of ≤2, adequate bone marrow function (absolute neutrophil count ≥1,000/μL irrespective of growth factor support, platelet count ≥30,000/mm3, hemoglobin ≥8 g/dL), and creatinine clearance ≥50 mL/min. At study entry, all patients were screened for Richter’s transformation by positron emission tomography and were excluded if Richter’s transformation was confirmed on biopsy. Patients received venetoclax starting at 20mg daily with stepwise dose ramp-up over five weeks to the target 400mg daily dose. For patients with rapidly-progressing disease, an accelerated schedule of administration was utilized. Treatment continued until disease progression or discontinuation due to other reasons. The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of venetoclax monotherapy. Efficacy was measured by overall response rate, defined as the proportion of patients with an overall response based on the investigator’s assessment per iwCLL criteria. Safety was evaluated via adverse event monitoring and laboratory assessments. This study is ongoing and data for this interim analysis per regulatory agency request were collected as of June 30, 2017 and included all patients who received at least one dose of venetoclax. This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT02141282.

Findings

Patients were recruited from 15 sites across the United States between September 2014 and November 2016. The study enrolled 91 patients who previously received ibrutinib, 43 in the main cohort and 48 in the expansion cohort. At the time of analysis, the median time on study (ie, follow up) was 14 months (range: 0·1–31; IQR: 8–18) for all 91 patients, 19 months (range: 0·1–26; IQR: 9–27) for 43 patients in the main cohort, and 12 months (0·1–18; IQR: 8–15) for 48 patients in the expansion cohort. An objective response was achieved in 59 (65%) of 91 patients (95% CI: 53%, 74%. Main cohort: 30 [70%] of43, 95% CI: 54%; 83%; expansion cohort: 29 [60%] of 48, 95% CI: 43%, 72%). Eight (9%) of 91 patients achieved complete remission. Common grade 3 or 4 adverse events of (occurring in more than 2 patients) included neutropenia (in 46 [51%] of 91 patients), thrombocytopenia (in 26 [29%] of 91 patients), anaemia (in 26 [29%] of 91 patients), decreased white blood cell count (in 17 [19%] of 91 patients), decreased lymphocyte count (in 14 [15%] of 91 patients), febrile neutropenia (12 [13%] of 91 patients), hypophosphataemia (in 12 [13%] of 91 patients), diarrhoea (in 6 [7%] of 91 patients), fatigue (in 6 [7%] of 91 patients), pneumonia (in 6 [7%] of 91 patients), hyponatraemia (in 6 [7%] of 91 patients), hypertension (in 6 [7%] of 91 patients), hyperglycaemia (in 5 [5%] of 91 patients), hypokalaemia (in 5 [5%] of 91 patients), abdominal pain (in 4 [4%] of 91 patients), increased lymphocyte count (in 4 [4%] of 91 patients), hypoxia (in 4 [4%] of 91 patients), cellulitis (in 3 [3%] of 91 patients), fall (in 3 [3%] of 91 patients), increased alanine aminotransferase (in 3 [3%] of 91 patients), hypocalcaemia (in 3 [3%] of 91 patients), autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (in 2 [2%] of 91 patients), cataract (in 2 [2%] of 91 patients), lung infection (in 2 [2%] of 91 patients), urinary tract infection (in 2 [2%] of 91 patients), increased aspartate aminotransferase (in 2 [2%] of 91 patients), dehydration (in 2 [2%] of 91 patients), hypercalcaemia (in 2 [2%] of 91 patients), hypoalbuminaemia (in 2 [2%] of 91 patients), syncope (in 2 [2%] of 91 patients), and dyspnoea (in 2 [2%] of 91 patients). Seventeen (19%) of 91 patients died, with 7 due to disease progression; seven deaths occurred within 30 days after the last dose of venetoclax due to disease progression, Corynebacterium sepsis, multi-organ failure, septic shock, possible cytokine release syndrome on subsequent therapy, mechanical asphyxia, and one cause of death was unknown. None of these deaths were attributed to treatment with venetoclax..

Interpretation

Venetoclax showed durable clinical activity and favourable tolerability in patients with CLL whose disease progressed during or after prior treatment with ibrutinib.

INTRODUCTION

Small molecule inhibitors of B-cell receptor (BCRi) signaling target an essential biology in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and have rapidly supplanted cytotoxic chemotherapy for both untreated and relapsed disease.1,2 The Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib has demonstrated high rates of durable response and prolonged survival and is approved for the treatment of previously-untreated or relapsed CLL.3–6

Although many patients achieve sustained disease control with continuous ibrutinib, few effective options are currently available for CLL progressing during or after therapy. Relapse in high-risk patients (ie, 17p deletion [del(17)(p13·1)] and/or complex abnormal karyotype) is more frequently observed, with a 30-month estimated progression-free survival (PFS) for patients with del(17)(p13·1) of 48% vs 87% for patients without del(17)(p13·1) or del(11)(q22·3).4,7,8 Adverse events (AEs) can further lead to discontinuation.9

Optimal therapy for patients with CLL progressing after ibrutinib has yet to be determined in prospective studies. Outcomes after discontinuing ibrutinib are poor and progression can occur rapidly, in part due to the limited efficacy of available therapies in this setting.7–9 Recent investigations have identified acquired resistance mutations in the ibrutinib binding site C481 of BTK and/or phospholipase C-γ2 (PLCG2) in the majority of patients who progressed while receiving ibrutinib.7,10 New therapies in the setting of disease progression following ibrutinib are critical.

Venetoclax is a selective, orally bioavailable small-molecule BCL-2 inhibitor that is approved in the United States for patients with del(17)(p13·1) CLL who have received at least one prior therapy and in the EU and other countries for patients who are unsuitable for or have failed BCRi therapy and for patients without del(17)(p13·1) or TP53 mutation who have failed chemoimmunotherapy and BCRi.11,12 Approval was based on trial results in which venetoclax induced objective responses in approximately 80% of patients with relapsed/refractory CLL.13,14 However, these earlier studies included an insufficient number of patients progressing during or after ibrutinib to determine the clinical activity of venetoclax in that group. Additionally, the ability of venetoclax to eliminate ibrutinib-resistant clones bearing BTK C481S or PLCG2 mutations has not been evaluated.

Given the promising activity of venetoclax in relapsed/refractory CLL13,14 and poor outcomes in patients who relapsed after or are refractory to ibrutinib, we conducted the present study to evaluate the efficacy of venetoclax in this population.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

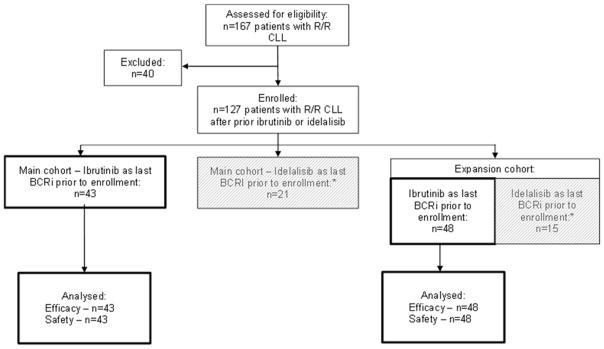

This phase two, open-label, nonrandomized, multicenter trial enrolled patients with CLL relapsed after or refractory to ibrutinib (includes discontinuation of prior ibrutinib due to AEs followed by progression off therapy). Patients were enrolled initially in the main cohort of the study and a subsequent study amendment permitted enrollment expansion to further establish the activity of venetoclax in patients with CLL relapsed/refractory to BCRi therapy (expansion cohort). Patients were enrolled in study arms based on the last BCRi received (Figure 1). Accrual of approximately 40 patients was planned initially (main cohort) and a subsequent study amendment permitted accrual of up to 60 additional patients to collect additional data and further establish the activity of venetoclax in patients with CLL relapsed/refractory to BCRi therapy (expansion cohort) (Figure 1). A separate cohort of patients with CLL relapsed/refractory to idelalisib (n=36) was also included in this study and will be reported in a separate publication. Ten patients who were previously treated with idelalisib were included in the analysis reported here because ibrutinib was the last BCRi they received prior to enrollment in this study. Patients were recruited from academic, public, and private hospitals and clinics in the United States. The washout period for prior BCRi was seven days in the main cohort and reduced to three days for the expansion cohort. The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of venetoclax monotherapy. Efficacy was measured by objective response rate (ORR) and safety was evaluated via adverse event monitoring and laboratory assessments.

Figure 1. Study Flow Diagram.

Data reported in this publication are for patients who had received ibrutinib as the last B-cell receptor pathway inhibitor (BCRi) therapy prior to enrollment (43 from the main cohort and 48 from the expansion cohort). *Data from patients who received idelalisib as their last BCRi prior to enrollment (n=36) will be reported in a separate publication and are indicated by the grey boxes in the diagram.

Patients at least 18 years of age with relapsed/refractory CLL who required therapy according to the 2008 International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (iwCLL) criteria were enrolled if their disease was refractory to treatment or progressed after discontinuation of ibrutinib.15 Per protocol, the definitions of relapse and refractory were based on iwCLL 2008 criteria.15 Relapse was defined as a patient who had previously achieved a response to treatment, but after a period of 6 or more months, demonstrated evidence of disease progression and refractory was defined as treatment failure or disease progression within 6 months to the last anti-leukemic therapy.15 Patients were evaluated for Richter’s transformation at study entry by positron emission tomography, mandatory biopsy for lesions with high standardized uptake value, and excluded if confirmed on biopsy. Patients with active and uncontrolled autoimmune cytopenias, unresolved toxicity from prior therapy, or a history of allogeneic stem cell transplantation within one year of study entry were also excluded. There was no minimum estimated life expectancy mandated for study entry, provided all protocol inclusion criteria were met. Karyotype was not assessed at the time of screening for the study and therefore data for complex karyotype are not available. Other mutational data (ie, TP53 mutation status, chromosomal abnormalities) were reported by investigators. All molecular subtypes of CLL were included in the study. All patients provided written informed consent. Complete enrollment criteria provided in the appendix (p.4).

The institutional review board at each participating site approved the study protocol. The study was conducted according to principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Guideline for Good Clinical Practice.

Procedures

Venetoclax was administered orally, once daily. Patients received venetoclax 20mg daily for one week, followed by weekly ramp up to 50mg, 100mg, 200mg, and then to the final daily dose of 400mg by week five (appendix p.7); in the expansion cohort, an accelerated dose ramp up over three weeks was permitted for patients who had high tumor burden with clinical signs of progression during screening (appendix p.8). Additionally, dose escalation of venetoclax to 600mg was allowed in the expansion cohort for patients who had not achieved an adequate response after assessment at week 12. The on-target effects of venetoclax can cause rapid reduction in tumour size (debulking) and may pose a risk of tumour lysis syndrome (TLS) during initial dosing. To mitigate this risk, prophylaxis and monitoring procedures were implemented, which are described in the appendix (p.8).

Safety was monitored through 30 days post treatment. Laboratory assessments and AE monitoring were done throughout the study and into the 30-day post-treatment period. AEs were graded according to the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for AEs, version 4·0.16 Laboratory monitoring for TLS was conducted during the 5-week dose ramp-up and TLS was assessed based on criteria established by Howard and colleagues.17

Dose adjustments were recommended for patients with grade 3 or 4 AEs. At the time of the first event, venetoclax could be interrupted and dosing resumed at the target dose following resolution of the AE. If subsequent AEs required dose interruptions, dosing could resume at a lower dose following resolution of the AE. For neutropenia, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) could be administered concurrently with venetoclax as needed and was strongly recommended for patients with grade 4 events (absolute neutrophil count <500/μL). If the patient developed febrile neutropenia or grade 4 neutropenia persisted for more than one week despite growth factor support, then venetoclax dosing was interrupted until recovery of neutrophil count >500/μL. Following dose interruption, venetoclax could then be re-initiated at a lower dose. For blood chemistry changes or symptoms suggestive of TLS, dosing on the next day was withheld unless there was resolution of changes/symptoms within 24–48 hours of the last dose; subsequently dosing resumed at the same dose. If changes or symptoms resolved more than 48 hours after the last dose, dosing was resumed at a lower dose (see also appendix p.9).

Treatment continued until disease progression or discontinuation due to other reasons and patients were removed from the study at the time of disease progression and/or discontinuation of venetoclax for other reasons.

Outcomes

The primary efficacy endpoint was ORR, defined as the proportion of patients with an overall response based on the investigator’s assessment.15 Response was assessed by the investigator based on physical exam, laboratory results, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, and bone marrow evaluation according to iwCLL criteria.15 Assessments were performed at screening and subsequent responses for patients in the main cohort were assessed by investigators at weeks eight, 24, and every 12 weeks thereafter, up to one year. For patients in the main cohort, response data upon completion of 24 weeks on venetoclax were also reviewed by an independent review committee (IRC). Patients in the expansion cohort underwent response assessments at weeks 12 and 36. Responses were confirmed by a second assessment at least two months after first assessed. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were performed at screening and within two months after other criteria for complete remission (CR) were observed. All patients, including those identified as having stable disease, received venetoclax until disease progression or discontinuation due to other reasons. This open-label phase 2 trial was a proof-of-concept study that was designed to assess the efficacy of venetoclax in ibrutinib-treated patients at earlier time points (weeks 8 and 24) in the main cohort. Responses improved over time in patients from the main cohort as they have been evaluated every 12 weeks after week 24 for up to one year. Once established that there was efficacy in this population, the expansion cohort had an increased duration of efficacy assessment to keep consistent with the pivotal trial of venetoclax monotherapy in patients with del(17)(p13·1) CLL and to allow for pooled analyses across venetoclax monotherapy trials in the future.13

Secondary endpoints included time-to-event analyses. Duration of response (DOR) was defined as the number of days from the date of first response to the earliest recurrence or disease progression. If a patient was still responding, then the patient’s data were censored at the date of the patient’s last available disease assessment. Patients who never had a response had censored data on the date of enrollment. Time to progression (TTP) was defined as the number of days from the date of first dose or enrollment if not dosed to the date of earliest disease progression. All events of disease progression were included regardless of whether progression occurred while the patient was taking venetoclax or had previously discontinued. If the patient did not experience disease progression, then the data were censored at the date of the last available disease assessment. PFS was defined as the number of days from the date of first dose to the date of earliest disease progression or death. Data were censored at the time of last tumor assessment for patients without an event or at the time of data cutoff if the assessment was done after the cutoff date. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the number of days from the date of first dose to the date of death for all dosed patients. For patients who did not die, data were censored at the date of last study visit or the last known date to be alive, whichever was later.

Minimal residual disease (MRD) was an exploratory endpoint. Six-color flow cytometry (sensitivity: 10–4) performed according to ERIC protocol18,19 was used to evaluate MRD in peripheral blood for all patients beginning at week 24 and every 12 weeks thereafter for those achieving partial remission (PR) or better. Exploratory identification of BTK and PLCG2 mutations was performed for all patients enrolled to the main cohort according to published methods.20 Health economic and patient-reported outcome measures (eg, EORTC QLQ C30 and EORTC QLQ CLL16 [measure of health related quality of life specific to CLL] and EQ-5D-5L [measure of general health status with visual analogue scale]) were also exploratory assessments that will be reported in a separate publication. Methods for exploratory analyses of MRD evaluation and resistance mutation testing, as well as pharmacokinetic assessments are in the appendix (p.12).

Statistical Analysis

This study is ongoing and data for this interim analysis per regulatory agency request were collected as of June 30, 2017. Efficacy and safety analyses included all patients who received at least one dose of venetoclax. Exploratory MRD and resistance mutation analyses are included for patients with available data. Analyses were performed by using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Initial target enrollment for the main cohort of the study was approximately 60 patients, with 40 patients with ibrutinib-resistant/refractory CLL in one arm and 20 patients with idelalisib-resistant/refractory CLL in the second arm (reported in a separate publication). With the initial activity of venetoclax observed in patients in the main cohort, a subsequent study amendment permitted additional enrollment of approximately 60 patients with either ibrutinib- or idelalisib-resistant relapsed/refractory CLL in the expansion cohort, which was similar to the number of patients targeted for the main cohort. Patients who had received both agents and any additional interim therapy were enrolled into the corresponding arm on the basis of their most recent BCRi treatment. There were no planned hypotheses testing on the primary efficacy endpoint, ORR. ORR is presented by a point estimate and its corresponding 95% confidence interval. A sample size of 20 patients ensured that the distance of true rate was within 23% of the observed rate, with 95% confidence interval (CI). A sample size of 40 patients would ensure that the distance of true rate was within 17% of the observed rate, with 95% confidence. A sample size of 60 patients would ensure that the distance of true rate was within 14% of the observed rate, with 95% confidence.

ORR was defined as the proportion of patients with an overall response based on the investigator’s assessment and calculated for all patients based on iwCLL criteria.15 The 95% confidence interval based on binomial distribution was constructed for calculated ORR. DOR, TTP, PFS, and OS were key secondary endpoints based on investigator assessment and were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier methodology, with median time-to-event calculated along with the corresponding 95% CI. This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT02141282.

Role of the funding source

The study was designed jointly by the sponsors (AbbVie and Genentech) and investigators. Investigators and their research teams collected the clinical data. AbbVie confirmed and analyzed the data, and was involved in the interpretation of results. Both AbbVie and Genentech were involved in the decision to develop the publication and reviewed the publication prior to submission. The first author wrote the first draft of this manuscript. Subsequent drafts were prepared by all authors and medical writers employed by AbbVie. All authors had access to the raw data. All authors made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication and attest to the accuracy and completeness of the data reported. The corresponding author had full access to all of the data and the final responsibility to submit for publication. The full trial protocol is available in the appendix.

RESULTS

Patients

Patients were recruited from 15 sites across the United States between September 2014 and November 2016. A total of 91 patients were enrolled (main cohort, n=43; expansion cohort, n=48), with all 91 patients included in demographics, efficacy and safety analyses described below. Primary reasons for discontinuation of prior ibrutinib included disease progression (50 [55%] of 91 patients; based on iwCLL criteria15 with or without evidence of BTK or PLCG2 mutation during treatment), and AEs (30 [33%] of 91 patients; these patients subsequently progressed after discontinuing ibrutinib). The remaining patients had achieved maximal clinical benefit with ibrutinib (6 [7%] of 91 patients), completed a defined course of treatment (3 [3%] of 91 patients), and/or discontinued for other unspecified reasons (2 [2%] of 91 patients) with subsequent CLL progression. Per iwCLL criteria definitions,15 28 (31%) of 91 patients relapsed during or after discontinuation of prior ibrutinib and 62 (68%) of 91 patients were refractory to prior ibrutinib (Table 1). Screen failures occurred in 27 patients, six of whom were excluded based on biopsy-confirmed Richter’s transformation (see appendix p.14 for all reasons for screen failures).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Baseline Clinical Characteristics

| Characteristic | Patients who received ibrutinib as the last prior BCRi | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main cohort n=43 |

Expansion cohort n=48 |

Total N=91 |

|

| Age, median (range), years | 66 (48 – 80) | 65 (28 – 81) | 66 (28 – 81) |

| Male, n (%) | 33 (77) | 31 (65) | 64 (70) |

| White, n (%) | 40 (93) | 44 (92) | 84 (92) |

| ECOG grade, n (%)* | |||

| 0 | 13 (30) | 16 (33) | 29 (32) |

| 1 | 27 (63) | 27 (56) | 54 (59) |

| 2 | 3 (7) | 5 (10) | 8 (9) |

| Baseline laboratory values,† median (range) | |||

| Lymphocyte count, ×109/L | 19 (0·2 – 263) | 6·6 (0·3 – 230) | 10·1 (0·2 – 263) |

| ≥25 ×109/L, n (%) | 17 (40) | 10 (22) | 27 (30) |

| ≥100 ×109/L, n (%) | 7 (16) | 5 (11) | 12 (13) |

| Neutrophil count, ×109/L | 3·7 (0·53 – 24) | 3·4 (0·3 – 18) | 4·2 (0·53 – 24) |

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 116 (15 – 446) | 106 (26 – 336) | 110 (15 – 446) |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 11·3 (6·9 – 15·3) | 12·2 (8·6 – 16·5) | 11·7 (6·9 – 16·5) |

| Creatinine clearance, mL/min | 78·2 (39·5 – 119) | 75·7 (34·3 – 188) | 76 (34·3 – 188) |

| Bulky nodal disease, n (%) | |||

| ≥5 cm | 15 (35) | 21 (44) | 36 (40) |

| ≥10 cm | 7 (16) | 2 (4) | 9 (10) |

| Tumour lysis syndrome risk category‡ | |||

| Low | 15 (35) | 19 (40) | 34 (37) |

| Medium | 11 (26) | 20 (41) | 31 (34) |

| High | 17 (39) | 9 (19) | 26 (29) |

| Prognostic factors based on site-reported data,§ n/N (%) | |||

| Unmutated IGHV | 25/29 (86) | 25/38 (66) | 50/67 (75) |

| del(17)(p13·1) | 21/43 (49) | 21/47 (40) | 42/90 (47) |

| del(11)(q22·3) | 13/43 (30) | 17/48 (33) | 30/91 (33) |

| TP53 mutation | 15/41 (37) | 14/46 (30) | 29/87 (33) |

| CD38 positive | 21/42 (50) | 16/44 (36) | 37/86 (43) |

| ZAP-70 positive | 12/24 (50) | 17/40 (43) | 29/64 (45) |

| No. of prior therapies, median (range) | 5 (1 – 12) | 4 (1 – 15) | 4 (1 – 15) |

| Prior ibrutinib use, n (%) | 43 (100) | 48 (100) | 91 (100) |

| Time on prior ibrutinib, median (range), months | 18 (1 – 56) | 21 (1 – 61) | 20 (1 – 61) |

| Relapsed during or after ibrutinib,|| n (%) | 11 (26) | 17 (35) | 28 (31) |

| Refractory to ibrutinib,|| n (%) | 32 (74) | 30 (63) | 62 (68) |

| Prior idelalisib use¶, n (%) | 4 (9) | 7 (15) | 11 (12) |

| Time on prior idelalisib, median (range), months | 16 (2 – 31) | 9 (2 – 33) | 9 (2 – 33) |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

ECOG performance status ranges from 0 to 5, where higher numbers indicate greater disability.

Baseline values were assessed after screening but before the first dose of venetoclax was given.

Low was defined as all lymph nodes ≤5 cm with an absolute lymphocyte count <25 ×109/L. Medium was any lymph node ≥5 cm to <10 cm or an absolute lymphocyte count ≥25 ×109/L. High was any lymph node ≥10 cm or lymph node ≥5 cm and absolute lymphocyte count ≥25 ×109/L.

Data are presented for all patients with available data.

Definitions of relapse and refractory are based on iwCLL 2008 criteria.15 Relapse was defined as a patient who had previously achieved a response to treatment, but after a period of 6 or more months, demonstrated evidence of disease progression and refractory was defined as treatment failure or disease progression within 6 months to the last anti-leukemic therapy. One patient was not categorized as having CLL refractory to or relapsed during or after ibrutinib. This patient did not have available response data and discontinued ibrutinib due to an adverse event followed by disease progression.

Eleven patients had received prior idelalisib followed by ibrutinib during their previous course of treatment.

Disposition on Treatment

As of June 30, 2017, median time on study (ie, follow up) was 14 months (range: 0·1–31; IQR: 8–18); 19 months (range: 0·1–26; IQR: 9–27) for the main cohort and 12 months (range: 0·1–18; IQR: 8–15) for the expansion cohort. Forty-six (51%) of 91 patients continue venetoclax treatment (appendix p.14). The primary reason for discontinuation of venetoclax was CLL progression in 22 (24%) of 91 patients and Richter’s transformation in five (5%) of 91 patients (see appendix p.15). The remaining patients discontinued for AEs (6 [7%] of 91 patients), proceeding to allogeneic stem cell transplantation in remission (5 [6%] of 91 patients), consent withdrawn (1 [1%] of 91 patients), investigator’s request (1 [1%] of 91 patients), and other reasons (5 [6%] of 91 patients). Seventeen (19%) of 91 patients died, with seven due to CLL progression; seven deaths occurred within 30 days after the last dose of venetoclax due to disease progression, Corynebacterium sepsis, multi-organ failure, septic shock, possible cytokine release syndrome on subsequent therapy, mechanical asphyxia, and one cause of death was unknown. None of these deaths were attributed to treatment with venetoclax.

Efficacy

The investigator-assessed ORR was 59 (65%) of 91 patients (95% CI: 53%, 74%) (Table 2) and median time to first response was 2·5 months (range: 1·6–15) and median time to best response was 7·9 months (range: 3·5–19). Fifty-one (56%) of 91 patients achieved PR or nodular PR (nPR), and 8 (9%) of 91 patients achieved CR or CR with incomplete bone marrow recovery (CRi). Median time to first PR/nPR was 2·6 months (range: 1·6–16.4) and to confirmatory second assessment per protocol (at least two months after first assessed) was 7·6 months (range: 5–17·7). Median time to CR/CRi was 8·2 months (range: 3·5–19). Twenty-two (24%) of 91 patients had stable disease as best response and five (6%) had CLL progression. Nineteen (59%) of 32 patients with B symptoms at baseline reported resolution of symptoms by week eight.

Table 2.

Objective Responses With Venetoclax Monotherapy as Assessed by the Investigator

| Patients who received ibrutinib as the last prior BCRi | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main cohort n=43 |

Expansion cohort n=48 |

All patients N=91 |

|

| ORR, n (%); [95% CI] | 30 (70); [54%; 83%] | 29 (60); [43%, 72%] | 59 (65); [53%, 74%] |

| CR/CRi, n (%) | 4 (9) | 4 (8) | 8 (9) |

| nPR, n (%) | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | 3 (3) |

| PR, n (%) | 24 (56) | 24 (48) | 48 (52) |

| SD, n (%) | 8 (19) | 14 (29) | 22 (24) |

| PD, n (%) | 1* (2) | 4* (8) | 5 (6) |

| Discontinued prior to response assessment | 4 (9) | 2 (4) | 6 (7) |

BCRi, B-cell receptor pathway inhibitor; ORR, objective response rate = complete response (CR) + complete response with incomplete bone marrow recovery (CRi) + nodular partial remission (nPR) + partial remission (PR); SD, stable disease; PD, disease progression.

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia progressed, and patients discontinued because of progression.

For patients in the main cohort who had been treated for a median of 19 months, responses were observed for 30 (70%) of 43 patients (95% CI: 54%, 83%). Following a median time on venetoclax of 12 months, the response rate for patients in the expansion cohort was 29 (60%) of 48 patients (95% CI: 43%, 72%), with 13 patients having stable disease and four with progression. Two patients in the expansion cohort escalated to a daily dose of 600mg venetoclax due to clinical progression, and neither had improvement at higher dose. Of seven patients in the expansion cohort who were scheduled to receive accelerated ramp up due to rapidly progressive CLL, five were able to reach the target 400mg dose with four achieving PR and one patient discontinued due to CLL progression. The two remaining patients discontinued due to CLL progression before reaching the 400mg dose.

Response rates at 24 weeks reported by an IRC in the 43 patients in the main cohort were similar to those assessed by the investigators (IRC, 30 [70%] of 43; investigator-assessed, 29 [67%] of 43).21 Evaluations were discordant between investigators and IRC for ten patients; two with CR by investigator assessment were deemed as PR by IRC, one with investigator-assessed CR was evaluated as CRi by IRC, two with investigator-assessed nPR were PR by IRC, two with investigator-assessed PR were non-responders per IRC, and three patients with stable disease by investigator assessment were considered PR by IRC. Discrepancies were primarily due to differences in interpretation of splenomegaly by CT scan, the sum product of the lymph nodes by radiographic assessment given different nodes chosen, and timing of the CT scan.

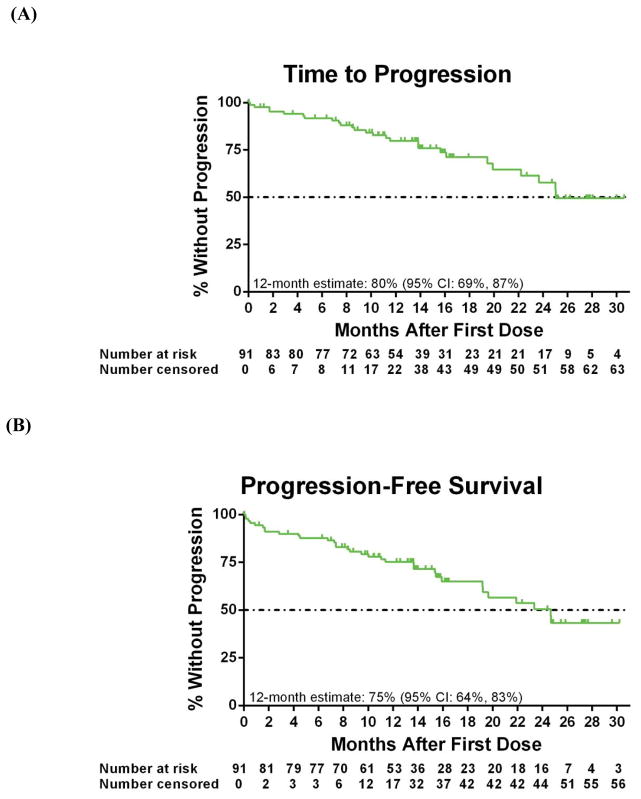

The investigator-assessed median TTP for all patients was 24·7 months (95% CI: 19·6, -), with an estimated rate at 12 month of 80% (95% CI: 69%, 87%) (Figure 2A). Median PFS was 24·7 months (95% CI: 19·2, -), with an estimated 12-month PFS rate of 75% (95% CI: 64%, 83%) (Figure 2B); the estimated 12-month OS was 91% (95% CI: 83%, 95%; Figure 2C). Among responding patients, median DOR has not yet been reached (95% CI: 17·6, -; Figure 2D), and estimated 12-month DOR was 88% (95% CI: 76%, 95%).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier curves.

For all 91 patients, shown are the (A) time to progression (26 patients had an event), (B) progression-free survival (33 patients had an event), (C) overall survival (17 patients had an event) assessed by the investigator. (D) Duration of overall response is shown for 59 patients with a response (15 patients had an event), as assessed by the investigator. Below each curve is the number of patients at risk for the event at each time point. Tick marks represent censored data.

ORR with venetoclax for patients who had discontinued prior ibrutinib due to AEs versus disease progression was 19 (63%) of 30 patients (95% CI: 44%, 80%) and 27 (54%) of 50 patients (95% CI: 39%, 68%), respectively. Median PFS and 12-month estimates were not reached (95% CI: 15·9, -) and 76% (95% CI: 56%, 88%) for patients who discontinued for AEs and 23·4 months (95% CI: 13·7, -) and 72% (95% CI: 57%, 83%) for those who discontinued prior ibrutinib due to disease progression. The estimated 12-month OS rate for patients who had discontinued prior ibrutinib due to AEs versus disease progression was 97% (95% CI: 79%, 99%) and 86% (95% CI: 72%, 93%), respectively. Among responding patients who discontinued prior ibrutinib due to AEs, median DOR had not yet been reached (95% CI: 14·3, -), with an estimated 12-month of 89% (95% CI: 63%, 97%). For patients who discontinued prior ibrutinib due to disease progression, median DOR on venetoclax was 21·7 months (95% CI: 16·6, -), with an estimated 12-month rate of 88% (95% CI: 67%, 96%).

Response rates were similar for patients with high-risk chromosomal abnormalities compared with patients without these factors. Of patients with known del(17)(p13·1) and/or TP53 mutation, 28 (61%) of 46 patients (95% CI: 45%, 75%) achieved an objective response, including 4 CR or CRi and 23 nPR or PR. Of patients who did not have either del(17)(p13·1) and/or TP53 mutation, 30 (67%) of 45 patients (95% CI: 51%, 80%) achieved an objective response, including 4 CR and 26 nPR or PR. Median PFS was 19·6 months (95% CI: 15·4, 24·7) for patients with known del(17)(p13·1) and/or TP53 mutation, with a 12-month PFS estimate of 72% (95% CI: 56%, 83%). For patients without these chromosomal abnormalities, median PFS had not yet been reached (95% CI: 19·2, -) and 12-month estimate was 79% (95% CI: 64%, 89%). OS estimate at 12 months for both patients with or without known del(17)(p13·1) and/or TP53 mutation was 91% (95% CI: 78%, 97%). For responders, median DOR was 21·9 months (95% CI: 17·6, -), with 12-month estimate of 92% (95% CI: 73%, 98%) for patients with known del(17)(p13·1) and/or TP53 mutation. Median DOR had not been reached (95% CI: 16·6, -) for patients without these chromosomal abnormalities, and the 12-month estimate was 84% (95% CI: 63%, 94%). Efficacy analyses for patients with lymph nodes <5 cm as measured at baseline compared with ≥5 cm are described in the appendix (p.18).

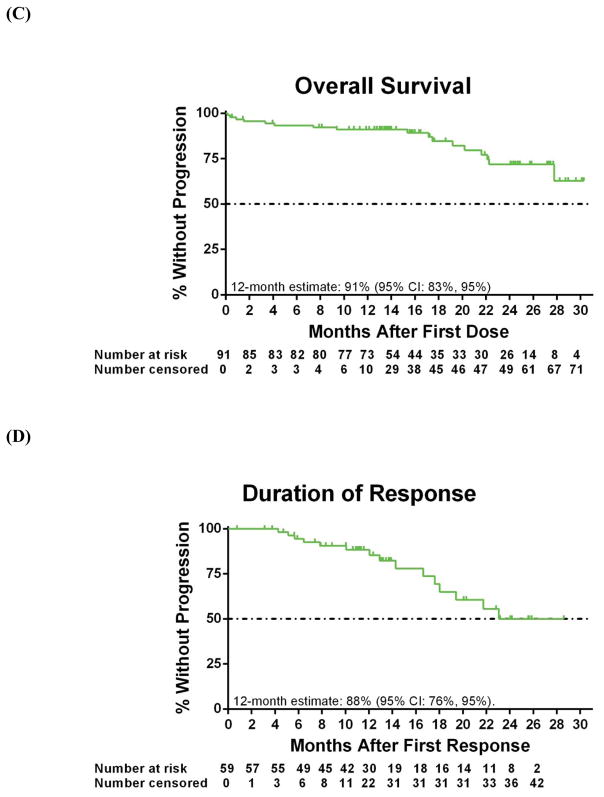

Fifty-seven patients were assessed for MRD in peripheral blood beginning at week 24, with MRD being an exploratory endpoint of the study. Twenty-four (42%) of 57 patients assessed achieved a MRD-negative result in peripheral blood (Figure 3A; 24 [26%] of all 91 patients per intent-to-treat principles), with five of 13 patients assessed demonstrating subsequent MRD-negativity in bone marrow. For the majority of patients who had an MRD-positive assessment in peripheral blood, the actual percentage of CLL cells present were low (Figure 3A). At the inception of the study, there was no plan to discontinue venetoclax so all five patients who achieved MRD-negativity in both peripheral blood and bone marrow are currently active on study and continue venetoclax treatment. One patient who achieved MRD-negativity in peripheral blood at 5 months subsequently discontinued venetoclax due to CLL progression at 13 months on therapy. Median PFS had not been reached for patients with MRD negativity in blood and was 24·7 months (95% CI: 15·4, -) for patients who were MRD positive (Figure 3B), and there was a significant difference in PFS between MRD-negative and MRD-positive patients (p=0·01 by log-rank test).

Figure 3. (A) Percentage of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) cells in peripheral blood by minimal residual disease (MRD) status.

Plot depicts the lowest percentage of MRD as assessed by six-color immunophenotyping (standardized ERIC protocol) during venetoclax treatment weeks 24 to 48. The percentage was calculated as the number of CLL cells divided by the total number of cells measured (with a minimum of 500,000 cells measured per assay). MRD-negativity (blue) was defined as <0·01% CLL cells (dashed line). Data from 45 of the 57 patients assessed for MRD are shown here as 12 patients had an atypical phenotype and the level of residual disease may be under-valued by the ERIC scoring algorithm. Orange indicates MRD positivity; Blue indicates MRD-negativity; triangle, complete response or complete response with incomplete bone marrow recovery (CR/CRi); square, partial response (PR) or nodular partial response (nPR); and circle, stable disease (SD); * indicates patients with subsequent assessments indicating MRD-negativity in bone marrow. (B) Progression-free survival (PFS) by MRD status. Shown are Kaplan-Meier curves for investigator-assessed PFS by peripheral blood MRD status. Data are shown for all 57 patients assessed for MRD, including 12 patients with an aberrant phenotype who had detectable disease and were considered MRD positive. There was a significant difference in PFS between 24 patients with MRD-negativity in blood (three patients had an event) vs 33 patients who were MRD-positive (14 patients had an event) (p=0·0093 by log-rank test). Below each curve is the number of patients at risk for the event at each time point. Tick marks represent censored data. For MRD analyses, patients with aberrant phenotype did have detectable disease present and were considered MRD positive per our assessments. These patients were excluded from Figure 3A as an actual level of % CLL cells could not be assessed due to scoring algorithm bias but were retained for the analysis shown in Figure 3B as they do have detectable disease and are MRD positive.

Efficacy in Patients With BTK or PLCG2 Resistance Mutations

Baseline samples to evaluate for BTK or PLCG2 mutations, which are associated with resistance to ibrutinib, were evaluated in 21 patients who had developed refractory CLL while on ibrutinib. BTK or PLCG2 mutations were present in 17 (81%) of 21 patients evaluated (appendix p.18). Allele frequencies ranged from 1·2% to 98·8%. BTK mutations at C481 as the sole mutation were present in 14 (67%) of 21 patients evaluated (C481S in 12 [1 in association with C481A], C481A in 1, and C481Y in 1). One patient had a BTK C481S mutation in conjunction with a L845F mutation in PCLG2, and three patients had mutations only in PLCG2 at sites previously seen in ibrutinib resistance that have been described to be potential gain of function mutations.7,20,22–25 Responses with venetoclax were seen in 12 (71%) of 17 cases, including 11 PR and 1 CRi, where known ibrutinib resistance mutations were present at study entry (appendix p.18). There was no difference in PFS for patients with versus without mutations (median PFS for patients with mutations was 21·9 months and was 15·4 months for patients without mutations; p=0·96 by log-rank test).

In ten patients with BTK C481S mutations, samples were available at baseline and the end of the first week of therapy, with allelic frequency shown in the appendix (p.19). Additionally, in eight patients from one institution with C481S mutations, samples were available at baseline and the end of 24, 48, and 72 weeks of therapy (appendix, p.19). Of these eight patients, allelic frequency of C481S BTK decreased in all, and tended to re-emerge prior to progression (appendix, p.19).

Safety

Across all 91 patients, the most common AEs of any grade were neutropenia in 56 (62%) patients, nausea in 51 (56%) patients, anaemia in 48 (53%) patients, diarrhoea in 47 (52%) patients, and thrombocytopenia in 43(47%) patients (Table 3); the frequency of these AEs was similar for the main and expansion cohorts. Treatment-emergent grade 3/4 events were primarily hematologic and included neutropenia in 46 (51%) of 91 patients, anemia in 26 (29%) of 91 patients, thrombocytopenia in 26 (29%) of 91 patients, and lymphocytopenia in 14 (15%) of 91 patients. Median time to the first grade 3/4 event was 21 days (range: 1–723) for neutropenia and 21 days (range: 1–582) for thrombocytopenia. Twenty-four (26%) of 91 patients had pre-existing neutropenia and 54 (59%) of 91 patients had thrombocytopenia. Twenty-seven (30%) of 91 patients received G-CSF during the study for management of neutropenia and/or infections. Forty-five (50%) of 91 patients experienced a serious AE, with the most frequent serious AEs (in more than 2 patients) being febrile neutropenia in 10 (11%) and pneumonia in 5 (6%) of 91 patients. Serious AEs considered possibly related to venetoclax treatment were febrile neutropenia (n=2), pneumonia (n=1), increased potassium levels (n=1), hyperphosphatemia (n=1), and hyperkalemia (n=1). Thirty-two (35%) of 91 patients interrupted venetoclax because of AEs, with neutropenia being the most common reason for dosing interruption in 9 patients. Fifteen (16%) of 91 patients required a dosage reduction, most commonly due to nausea in 12 patients, neutropenia in 11 patients, and diarrhoea in 9 patients. All dose adjustments for laboratory abnormalities occurred during dose ramp up. Six patients discontinued venetoclax due to AEs of multi-organ failure, dysphagia and stomach ulcers, Corynebacterium sepsis, salivary gland cancer, and mechanical asphyxia. Four patients discontinued within 30 days of starting venetoclax and two patients discontinued after one year of therapy with salivary gland cancer and asphyxia. Six deaths occurred within 30 days after the last dose of venetoclax due to AEs of Corynebacterium sepsis (n=1), multi-organ failure (n=1), septic shock (n=1), possible cytokine release syndrome on subsequent therapy (n=1), mechanical asphyxia (n=1), and one cause of death was unknown (n=1) (Table 3). Electrolyte abnormalities (hyperphosphatemia and hyperuricemia or hyperkalemia, respectively) meeting Howard criteria17 for laboratory TLS were only observed in two patients with high tumour burden; both cases occurred during the 200mg dose of the standard ramp-up period.

Table 3.

Summary of Adverse Events

| n (%) | Grade 1 or 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | |||||

| Anaemia | 22 (24) | 26 (29) | 0 | 0 | 48 (53) |

| Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia | 0 | 0 | 2 (2) | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 0 | 12 (13) | 0 | 0 | 12 (13) |

| Neutropenia* | 10 (11) | 18 (20) | 28 (31) | 0 | 56 (62) |

| Thrombocytopenia† | 17 (19) | 11 (12) | 15 (17) | 0 | 43 (47) |

| Ear and labyrinth disorders | |||||

| Cataract | 0 | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | |||||

| Abdominal pain | 15 (17) | 4 (4) | 0 | 0 | 19 (21) |

| Constipation | 19 (21) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 (21) |

| Diarrhoea | 41 (45) | 6 (7) | 0 | 0 | 47 (52) |

| Nausea | 51 (56) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 52 (57) |

| Vomiting | 20 (22) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 21 (23) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | |||||

| Chills | 10 (11) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 11 (12) |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Fatigue | 33 (36) | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 0 | 39 (43) |

| Multi-organ failure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Peripheral oedema | 21 (23) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 (23) |

| Pyrexia | 17 (19) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 18 (20) |

| Immune disorders | |||||

| Cytokine release syndrome | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Infections and infestations | |||||

| Cellulitis | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 0 | 0 | 5 (5) |

| Corynebacterium sepsis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Lung infection | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 3 (3) |

| Pneumonia | 4 (4) | 5 (5) | 1 (1) | 0 | 10 (11) |

| Septic shock | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 24 (26) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 (26) |

| Urinary tract infection | 6 (7) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 8 (9) |

| Injury, poising, and procedural complications | |||||

| Bruising | 15 (17) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 (17) |

| Fall | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 0 | 0 | 5 (6) |

| Investigations | |||||

| Increased alanine aminotransferase | 11 (12) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 | 14 (15) |

| Increased aspartate aminotransferase | 16 (18) | 0 | 2 (2) | 0 | 18 (20) |

| Increased blood bilirubin | 11 (12) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 12 (13) |

| Decreased lymphocyte count | 9 (10) | 11 (12) | 3 (3) | 0 | 23 (25) |

| Increased lymphocyte count | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | 0 | 0 | 8 (9) |

| Decreased white blood cell count | 15 (16) | 14 (15) | 3 (3) | 0 | 32 (35) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | |||||

| Dehydration | 6 (7) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 8 (9) |

| Hypercalcaemia | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 6 (6) |

| Hyperglycaemia | 5 (5) | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 0 | 10 (11) |

| Hyperkalaemia | 13 (14) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 14 (15) |

| Hyperphosphataemia | 11 (12) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (12) |

| Hyperuricaemia | 12 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 (13) |

| Hypoalbuminaemia | 13 (14) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 15 (17) |

| Hypocalcaemia | 18 (20) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 | 21 (23) |

| Hypokalaemia | 15 (16) | 5 (5) | 0 | 0 | 20 (22) |

| Hyponatraemia | 11 (12) | 6 (7) | 0 | 0 | 17 (19) |

| Hypophosphataemia | 5 (5) | 11 (12) | 1 (1) | 0 | 17 (19) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | |||||

| Arthralgia | 16 (18) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 (18) |

| Back pain | 16 (18) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 (18) |

| Extremity pain | 12 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 (13) |

| Neoplasms benign, malignant, and unspecified | |||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma of skin | 5 (5) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 6 (6) |

| Nervous system disorders | |||||

| Dizziness | 12 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 (13) |

| Headache | 18 (20) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 19 (21) |

| Syncope | 0 | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | |||||

| Asphyxia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Cough | 24 (26) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 (26) |

| Dyspnoea | 12 (13) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 14 (15) |

| Hypoxia | 0 | 4 (4) | 0 | 0 | 4 (4) |

| Oropharyngeal pain‡ | 11 (12) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (12) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | |||||

| Rash | 11 (12) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (12) |

| Vascular disorders | |||||

| Hypertension | 5 (5) | 6 (7) | 0 | 0 | 11 (12) |

Table shows treatment-emergent grade 1 – 2 adverse events occurring in 10% of patients or more, grade 3 or 4 adverse events in two or more patients, and all grade 5 events. Appendix p.20 provides the complete list of all grade 3 or 4 adverse events reported.

Neutropenia included the preferred terms of neutropenia and decreased neutrophil count.

Thrombocytopenia included the preferred terms of thrombocytopenia and decreased platelet count.

Sore throat or throat pain due to upper respiratory tract infection.

DISCUSSION

Ibrutinib therapy has transformed the management of both untreated and relapsed CLL. However, acquired resistance to ibrutinib, most commonly observed in the setting of previously treated and high-risk genomic disease, has been associated with poor outcomes.8,10,26 Effective management and treatment for these patients represents an unmet need. Here, we report results of the first prospective study of any therapy for patients who were previously treated with ibrutinib, of whom 50 (55%) of 91 patients discontinued ibrutinib due to disease progression and 30 (33%) of 91 patients due to AEs. The rate of response to venetoclax was high, with an investigator-assessed ORR of 59 (65%) of 91 patients (95% CI: 53%, 74%). Responses were also observed for patients with historically poor outcomes, including those who discontinued prior ibrutinib due to disease progression and those with high-risk chromosomal abnormalities del(17)(p13·1) and/or TP53 mutation. Safety data are consistent with previous reports of single-agent venetoclax in relapsed/refractory CLL, with the frequency of adverse events reported for this heavily pre-treated population of patients with CLL refractory to or relapsed after ibrutinib being similar to that reported for venetoclax in a broader relapsed/refractory CLL population.13,14 Despite observations of highly proliferative disease in relapsed CLL upon discontinuation of ibrutinib, venetoclax was not associated with an elevated risk for TLS when recommended dose ramp up, prophylaxis, and monitoring were applied. As expected in this heavily-pretreated population, cytopenias and febrile neutropenia were commonly observed. All cases were effectively managed with dosage adjustment and/or supportive care and did not lead to discontinuation of venetoclax.

Per secondary Kaplan-Meier analyses, responses have been durable. Additionally, four of five patients who initiated venetoclax via accelerated dose ramp up due to high tumour burden and signs of rapid progression at screening achieved PR on venetoclax. Across efficacy and safety results, the outcomes on venetoclax reported for these patients who were previously treated with ibrutinib are similar to results with venetoclax monotherapy in broader relapsed/refractory CLL patients.14

Venetoclax acts as a BH3-mimetic, targeting BCL-2 in mitochondria independent of BCR signaling, and as such we hypothesized that BTK mutant clones would not confer resistance to venetoclax.26 In the subset of patients for whom available mutation data were available, we observed responses with venetoclax in 12 (71%) of 17 of cases where known ibrutinib resistance mutations were present at study entry, which supports the hypothesis based on mechanism of action. Furthermore, the allelic frequency of C481S BTK decreased for eight patients with serial data available up to 72 weeks on venetoclax, suggesting the potential for venetoclax to eradicate ibrutinib-resistant CLL clones.

A number of studies evaluating a broad range of therapeutic approaches have assessed the relationship between MRD and outcomes, and available evidence suggests that patients with MRD-negative status at the end of treatment have improved survival, independent of clinical response.27 In the current study, patients achieving MRD-negative responses experienced superior PFS, despite the fact that most achieved an objective response no better than PR. The majority of these patients with MRD-negative PR had low-volume residual nodal disease by imaging criteria.

This study has the following limitations including that this was a proof-of-concept study to first evaluate the activity of venetoclax in this population so was designed to be an open-label study. Furthermore, the wide confidence intervals for the ORR reported due to the number of patients in each cohort. Efficacy analyses were limited by mutational status (eg, IGHV) and karyotype status as data collection was not uniform; data for complex karyotype was not available and IGHV testing was incomplete as accessible historic data were reported by investigators at study start. Additionally, longer follow up will be needed to better establish the durability of response to venetoclax in this patient population.

This publication only reports on the patients who received ibrutinib as their last BCRi prior the enrollment on the study. As ibrutinib and idelalisib are approved for different indications and in different regions, the patients who received idelalisib as their last BCRi prior the enrollment will be reported in a separate publication to provide adequate attention to each patient population. Additionally, patient-reported outcomes have not yet been fully analyzed and will be reported at a later time.

In conclusion, venetoclax achieved a high rate of response among patients progressing after ibrutinib, including a subset with ibrutinib-resistance mutations, many of whom have heavily pre-treated disease harboring high-risk genetic aberrations. Venetoclax has demonstrated durable clinical activity and favourable tolerability across high-risk patient groups, including results from this prospective study of treatment for patients with CLL progression following ibrutinib.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Evidence before this study

Evidence accumulated prior to the study suggested that signaling via B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling pathway could play an important role in the development of CLL. The advent of BCR inhibitors (BCRi) transformed treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL), though patients who are refractory or relapse after these therapies experience poor outcomes. We searched PubMed for clinical trial reports up to end of 2014 (year of study start), to identify novel agents for treatment of CLL, using the terms: “chronic lymphocytic leukemia” and “CLL” in addition to “targeted therapy” “novel” “agent.” For the timeframe searched, 42 articles were identified.

The Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor, ibrutinib, demonstrated high rates of durable response and was approved for previously-treated patients with CLL. Though many patients can have sustained disease control on ibrutinib, patients with high-risk prognostic factors (eg, chromosome 17p deletion) often relapse and some developed resistance mutations even after achieving an initial response to therapy. Effective treatment options for patients who relapsed or were refractory to ibrutinib had not been well characterized at the time of this study initiation.

At the time of study initiation in 2014, optimal therapy for patients with CLL relapsed/refractory to ibrutinib had yet to be determined in prospective studies and represented a critical unmet need in CLL treatment.

Venetoclax is an orally bioavailable BCL-2 inhibitor, with a mechanism of action that is independent of the BCR pathway.

Added value of this study

To the best of our knowledge, this phase 2 study was the first prospective trial to evaluate treatment for patients progressing on or following ibrutinib. Based on prior data of venetoclax monotherapy for patients with relapsed/refractory CLL, we hypothesized that venetoclax would be tolerable and achieve responses in patients with CLL relapsed/refractory to ibrutinib. Venetoclax had an acceptable safety profile, consistent with other clinical studies of venetoclax monotherapy, and is highly active in patients with CLL relapsed/refractory to ibrutinib.. Moreover, responses to venetoclax were reported among patients with baseline ibrutinib-resistance mutations, with allelic frequency of mutations decreasing with time on therapy for patients with serial assessments, suggesting the potential for venetoclax to eradicate ibrutinib-resistant CLL clones.

Implications of all the available evidence

Few effective options are currently available for CLL progressing during or after ibrutinib, and our data support the use of venetoclax monotherapy in this patient population. Importantly, data on ibrutinib resistance mutations indicate that venetoclax may potentially eradicate ibrutinib-resistant CLL clones, which has not yet been reported in the context of a prospective clinical trial and represents an important advance in the management of ibrutinib-resistant CLL. As novel targeted agents become more widely available, continued study of treatment following progression during or after BCRi is critical to advance of treatment for CLL.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the patients and their families, study investigators, coordinators, and support staff. Venetoclax is being developed in collaboration between AbbVie and Genentech. AbbVie and Genentech provided financial support for the study and participated in the design, study conduct, analysis and interpretation of data, as well as the writing, review, and approval of the publication. Medical writing support was provided after generation of the initial draft by Sharanya Ford, PhD, and Deborah Eng, MS, ELS. Data programming support was provided by Baodong Xing, Jing Xu, Joseph Beason, Ming Zhu, and Vinay Tavva. All are employees of AbbVie.

Funding Source: AbbVie Inc. and Genentech Inc. JCB receives support from NIH R35 CA197734 and JCB/JAW receive support from R01 CA177292-03 for the resistance studies described.

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTORS

Conception and design: JB, JJ, JP, RH; Provision of patients and patient care: JJ, AM, WW, MD, MC, BDC, RF, NL, PB, SC, JW, JB; Data analysis, collection, and interpretation: all authors; JJ and JB wrote the first draft and all authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

J Jones: Advisory board member for Genentech, Abbvie, Pharmacyclics; Institutional research funding from Abbvie, Pharmacyclics, Genentech.

A Mato: Institutional research funding: Pharmacyclics, Gilead, Abbvie, TG therapeutics, Acerta; Consultant for Pharmacyclics, Abbvie, Janssen.

W Wierda: Research funding from AbbVie, Genentech; Consultant and speaker bureau for Genentech.

M Davids: Advisory board member for Genentech, Pharmacyclics, TG Therapeutics, Gilead, Incyte; Institutional research funding from AbbVie, Genentech, Pharmacyclics, TG Therapeutics, Infinity; Consultant for Genentech, AbbVie, Pharmacyclics, Janssen, Merck.

M Choi: Advisory board/consultancy for AbbVie, Gilead, and PCYC; Institutional research funding from AbbVie; Speakers bureau for Gilead, Abbvie, PCYC, and Genentech.

B Cheson: Paid consultancy for AbbVie, Roche-Genentech, Pharmacyclics, Gilead, Acerta; Institution receives research support from Acerta, Pharmacyclics, Gilead, Roche-Genentech, AbbVie.

R Furman: Consultant for AbbVie, Pharmacyclics, Janssen, Gilead, Genentech.

N Lamanna: Advisory board member for Abbvie, Celgene, Roche-Genentech, Janssen, Pharmacyclics; Institutional research funding from AbbVie, Roche-Genentech, Gilead, Infinity, Acerta.

P Barr: Consultancy for AbbVie.

S Coutre: Research funding from AbbVie.

J Woyach: Clinical trial support from Morphosys, Acerta, Karyopharm.

J Byrd: Clinical trial support from Pharmacyclics and Acerta; Unpaid consultant for Genentech, AbbVie, Acerta, Pharmacyclics, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society LLC.

B Chyla, L Zhou, A Salem, M Verdugo, R Humerickhouse, J Potluri: AbbVie employees and own stock.

References

- 1.Jain N, O’Brien S. Targeted therapies for CLL: Practical issues with the changing treatment paradigm. Blood Rev. 2016;30:233–44. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byrd JC, Jones JJ, Woyach JA, Johnson AJ, Flynn JM. Entering the era of targeted therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: impact on the practicing clinician. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3039–47. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.8262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, et al. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Eng J Med. 2015;373:2425–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Eng J Med. 2013;369:32–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrd JC, Brown JR, O’Brien S, et al. Ibrutinib versus ofatumumab in previously treated chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Eng J Med. 2014;371:213–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.IMBRUVICA. Prescribing Information. Janssen Biotech Inc; Horsham, PA, USA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maddocks KJ, Ruppert AS, Lozanski G, et al. Etiology of ibrutinib therapy discontinuation and outcomes in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:80–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2014.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jain P, Keating M, Wierda W, et al. Outcomes of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia after discontinuing ibrutinib. Blood. 2015;125:2062–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-603670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mato AR, Nabhan C, Barr PM, et al. Outcomes of CLL patients treated with sequential kinase inhibitor therapy: a real world experience. Blood. 2016;128:2199–2205. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-05-716977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woyach JA, Furman RR, Liu TM, et al. Resistance mechanisms for the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib. N Eng J Med. 2014;370:2286–2294. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.VENCLEXTA. Prescribing Information. AbbVie Inc; North Chicago, IL, USA: Genentech USA Inc; South San Francisco, CA, USA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.VENCLYXTO. [Summary of Product Characteristics] AbbVie Ltd; Maidenhead, United Kingdom: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stilgenbauer S, Eichhorst B, Schetelig J, et al. Venetoclax in relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia with 17p deletion: a phase 2, open label, multicenter study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;7:768–778. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts AW, Davids MS, Pagel JM, et al. Targeting BCL2 with venetoclax in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Eng J Med. 2016;374:311–322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111:5446–5456. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. [accessed December 18 2014];Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), Version 4.03. 2009 http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf.

- 17.Howard SC, Jones DP, Pui CH. The tumor lysis syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1844–1854. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0904569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rawstron AC, Villamor N, Ritgen M, et al. International standardized approach for flow cytometric residual disease monitoring in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Leukemia. 2007;21:956–964. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rawstron AC, Bottcher S, Letestu R, et al. Improving efficiency and sensitivity: European Research Initiative in CLL (ERIC) update on the international harmonised approach for flow cytometric residual disease monitoring in CLL. Leukemia. 2013;27:142–149. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Guinn D, et al. BTKC481S-mediated resistance to ibrutinib in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1437–1443. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones JA, Choi MY, Mato AR, et al. Venetoclax (VEN) monotherapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who relapsed after or were refractory to ibrutinib or idelalisib. Blood. 2016;128:637. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Everett KL, Bunney TD, Yoon Y, et al. Characterization of phospholipase C gamma enzymes with gain-of-function mutations. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:23083–23093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.019265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu TM, Woyach JA, Zhong Y, et al. Hypermorphic mutation of phospholipase C, gamma2 acquired in ibrutinib-resistant CLL confers BTK independency upon B-cell receptor activation. Blood. 2015;126:61–68. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-626846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burger JA, Landau DA, Taylor-Weiner A, et al. Clonal evolution in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia developing resistance to BTK inhibition. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11589–11602. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones D, Woyach JA, Zhao W, et al. PLCG2 C2 domain mutations co-occur with BTK and PLCG2 resistance mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia undergoing ibrutinib treatment. Leukemia. 2017;31:1645–1647. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cervantes-Gomez F, Lamothe B, Woyach JA, et al. Pharmacological and protein profiling suggest ABT-199 as optimal partner with ibrutinib in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:3705–3715. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovacs G, Robrecht S, Fink AM, et al. Minimal residual disease assessment improves prediction of outcome in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who achieve partial response: comprehensive analysis of two phase III studies of the German CLL study group. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3758–3765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Brien S, Jones JA, Coutre S, et al. Efficacy and safety of ibrutinib in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic leukemia with 17p deletion: results from the phase II RESONATE-17 trial. Blood. 2014;124:327. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.