Abstract

The use of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine was recently approved in Mainland China. This study determined the knowledge and attitudes of young women aged 20 to 35 years in Fujian Province, China, with regard to HPV and vaccination and explored the potential factors influencing their attitudes toward HPV vaccination. This was a cross-sectional study that collected data regarding the knowledge on and attitudes toward HPV and vaccination using questionnaires. Furthermore, the prevalence of HPV was determined from the sampled participants. A total of 1001 young women were included in the survey. This study demonstrated that the HPV prevalence rate was 15.7% (157/1001). Among all patients, 44.9% (n = 449) had heard of HPV; however, detailed knowledge about HPV was lacking. The majority (83.7%) expressed a willingness to be vaccinated. Specifically, knowledge of the dangers of HPV infection was significantly associated with the willingness to be vaccinated. In this study, women cited some concerns and expressed high expectations for the HPV vaccine, but the costs of vaccination reduced their willingness to be vaccinated. This study found that most patients did not have a detailed knowledge of HPV. Thus, there is a need for continued HPV promotion and education efforts, especially on the dangers of HPV infection, among young women aged 20 to 35 years in Fujian Province, China. Furthermore, it is important to subsidize the costs of vaccination for promoting vaccination campaigns in China.

Keywords: knowledge, attitudes, human papillomavirus, HPV vaccination, young women

Background

Cervical cancer is the third most frequent cancer among women globally, and its incidence is especially high in developing countries. Roughly, 528 000 new cervical cancer diagnoses are made per year, and 265 653 cervical cancer-related deaths occurred in 2012 alone.1 Eighty-five percent of cases arise in developing countries due to the lack of cervical cancer prevention and control programs.2 China, the largest developing country, has the highest number of patients with cervical cancer, with 98 900 new cases and 30 500 deaths in 2015.3 Persistent infection with one or more high-risk (HR) genotypes of human papilloma (HPV) is essential for the development of cervical cancer and its precursors.4,5 According to our previous study, the overall HPV prevalence rate was 20.57% and HPV-16, HPV-52, HPV-58, HPV-43, and HPV-18 were the top 5 prevalent genotypes in HPV-positive women, based on the hospital population in Fujian Province, China.6 In addition, Baloch et al revealed the prevalence and genotype distribution of HPV varied among different regions and HPV-16, HPV-52, HPV-58, and HPV-18 are the leading HR-HPV genotypes in Yunnan Province, China.7

The development of vaccines that provide protection against HPV is a major step toward reducing cervical cancer rates. Approximately 75% of sexually active people will be infected with HPV at some point during their lives. Moreover, vaccination prior to sexual debut, especially before the age of 18 years, is advised to ensure protection against target HPV types.8 Many countries have implemented HPV vaccination programs to reduce the burden of HPV-associated diseases.9,10 Mainland China has just approved Cervarix (GlaxoSmithKline, Wales), a 2-valent vaccine, for girls aged 9 to 25 years in 2016 and Gardasil (Merck Inc, Whitehouse Station), a 4-valent vaccine, for women aged 20 to 45 years in 2017. Studies on awareness regarding HPV and attitudes toward HPV vaccination have been conducted in many countries, including China.11-13 However, in China, researchers have focused on college students and parents for their awareness of the HPV vaccine.14-17 As the HPV vaccine has only been recently introduced in China, studies exploring willingness to be vaccinated among the target population, women aged 20 to 35 years who are sexually active, are necessary. They are essential when developing policies on how HPV vaccination should be applied to the cervical cancer control program.

In Australia, the HPV vaccination program covered about 86% adolescent girls, aged 12 to 13 years, who received at least one vaccine dose, with 77% receiving all three doses in 2013, based on the data from the National HPV Vaccination Program Register.18 High vaccine coverage has also been achieved in some other programs internationally, for example, in the United Kingdom (school-based delivery)19 and Denmark (clinic-based delivery).20 However, the HPV vaccination coverage is lower in Asian countries. In Hong Kong, 7.5% of adolescent girls are vaccinated, while a more recent study indicated the vaccination rate for girls younger than 18 years was even lower at 2.4%.21 Although adolescent girls in Hong Kong have generally favorable attitudes toward HPV vaccination and HPV programs are widely promoted through mass media, this rate is relatively low compared to that of other developed countries.22,23 Despite the numerous published studies focusing on HPV and vaccination in recent years, there are only a few studies focusing on awareness and attitudes toward HPV and vaccination among the women aged 20 to 35 years, considering that HPV prevalence is relatively higher in Mainland China.24-27

The purpose of this study was to examine the prevalence of HPV and the awareness and attitudes associated with HPV and vaccination among young women aged 20 to 35 years, who need to be protected by HPV vaccination and were of suitable vaccination age in Fujian Province, China, and to provide recommendations for the promotion of HPV vaccination in Mainland China in the future.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

Study design

This cross-sectional survey consisted of a self-administered questionnaire based on paper and data collection in a community population from different regions of Fujian Province, China, between December 2016 and March 2017.

Population

This study randomly selected 7 counties of the 68 counties, in Fujian Province, China. The research team first contacted each Maternity and Children’s Health Hospital in the 7 regions to request their assistance in providing 2 gynecologists to help the patients complete the questionnaire and to obtain the cervical specimens. Women aged 20 to 35 years living in Fujian Province, China, were recruited for this study, through targeted advertisements posted on communities and streets in various regions or on the local social media website. The population should satisfy the following criteria: (1) young women living in the selected regions, (2) volunteered to join the study and comply with follow-up visits, (3) aged between 20 and 35 years with an active sexual life, (4) not pregnant or breast feeding, (5) no history of cervical treatment or surgery, and (6) no sexual activity 48 hours before cervical exfoliated cell sample collection. There were 1001 young women who volunteered to participate in the study.

Ethical Considerations

Before enrollment to the study, the participants were informed of the purpose and contents of the study. All participants provided written informed consent. They were also informed that their participation was totally voluntary and that they had the right and freedom to withdraw from the study at any time without providing a reason. This study was approved by the Fujian Provincial Maternity and Children’s Hospital, affiliated hospital of Fujian Medical University (approval number: 2016-019).

Cervical Specimen Collection and Polymerase Chain Reaction–Reverse Dot Blot HPV Genotyping

Cervical cells were collected using dry swab samples, according to routine procedures, from the cervical canal of all participants and placed in a 20-mL standard test tube filled with ThinPrep PreservCyt solution (Hologic Inc, Waltham, Massachusetts) for HPV DNA testing. For HPV assays, 1 mL of the cell suspension was used for DNA extract and was stored at −20°C. The HPV testing was performed using the polymerase chain reaction-reverse dot blot Yaneng HPV Genotyping Kit (Yaneng Biotech, Shenzhen, China), which is capable of detecting 23 genotypes, including 18 HR-HPV types (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, 82, and 83) and 5 low-risk (LR)-HPV types (6, 11, 42, 43, and 81).6

Instrument

The paper-based questionnaire used in this study was modified from a study conducted by a Chinese research team that also investigated similar issues in low-resource regions11 and was designed in the Chinese language. The 3-page questionnaire was designed to collect data in 3 areas: (1) basic information on sociodemographic status (7 items), (2) knowledge of HPV (7 items), and (3) attitudes toward the HPV vaccine (6 items). Some questions had 3 possible options (Yes/No/Don’t know); the option “Don’t know” was considered an incorrect answer. The remaining questions were multiple-choice.

Data Collection

Overall, 1100 questionnaires were distributed, and 1001 participants responded. The questionnaire was self-administered, which were to be filled in individually by the participants under the strict vigilance of the research team which serves as invigilators to monitor the participants. However, if the participants encountered any problems, a team from the Maternity and Children’s Health Hospital staff in the 7 counties who received the rigorous training about the on-site questionnaire quality control were available for help, such as explaining the questions the participants found confusing, translating the questions into local language, and so on. Upon completion of the survey, we provided free HPV screening to thank them for their time and participation. A database was created using EpiData 3.1 (Odense, Denmark, in Danish: EpiData foreningen). To ensure accuracy, 2 different researchers entered the data separately.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York). Univariate analysis was used to generate frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Descriptive statistics were used to identify the general demographics of the patients, along with their knowledge and attitudes regarding HPV and vaccination. To compare the patients’ attitudes toward HPV vaccination, Pearson tests were used. A P value <.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Overall, 1001 young women were enrolled in the study, and all completed the questionnaires successfully; cervical swab specimens were obtained from all patients for the HPV DNA assay.

Prevalence of HPV Infection

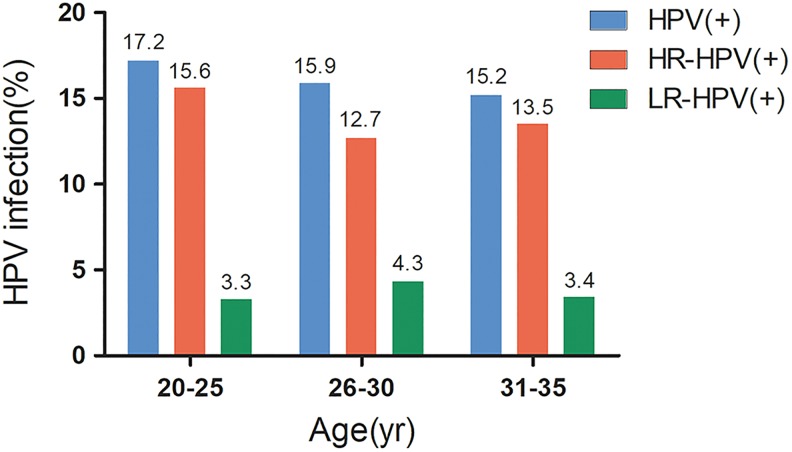

The overall HPV infection in this population was 15.7% (157/1001); the positivity for HR-HPV and LR-HPV was 13.4% (134/1001) and 3.7% (37/1001), respectively. The HPV infection for the different age groups were 17.2% (aged: 20-25 years), 15.9% (aged: 26-30 years), and 15.2% (aged: 31-35 years; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of HPV infections among different age. Noted: Some people have double infection with high-risk HPV and low-risk HPV. LR-HPV, low-risk human papillomavirus; HPV indicates human papillomavirus; HR-HPV, high-risk human papillomavirus.

Participants’ Demographics and Characteristics

A summary of the respondents’ characteristics is provided in Table 1. The mean age of the 1001 participants was 29.5 ± 3.3 years. The majority (74.6%) had achieved at least high school education, including 44.9% with undergraduate degrees or higher and 25.4% went to junior school or under. There were 29.7% white-collar workers and civil servants, 24.5% professionals, 22.0% unemployed, 11.9% students, 11.2% laborers, 0.5% others, and 0.3% farmers, respectively. About 59.5% lived in the city, while the remainder lived in rural areas. The majority of patients had a monthly income of ¥3001 to 8000 (US$472.1-1258.4; 63.0%), below ¥(China)3000 (US$471.9; 22.3%), or above ¥8000 (US$1258.4; 14.7%).

Table 1.

Baseline Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants.

| Characteristics | N = 1001 n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age range (year) | |

| 20-25 | 122 (12.2) |

| 25-30 | 433 (43.2) |

| 31-35 | 446 (44.6) |

| Marital | |

| Married or previously married | 948 (94.7) |

| Unmarried | 46 (4.6) |

| Other | 7 (0.7) |

| Education | |

| Junior school or under | 254 (25.4) |

| High school | 297 (29.7) |

| Undergraduate or higher | 450 (44.9) |

| Occupation | |

| White-collar workers and civil servant | 297 (29.7) |

| Professionals | 245 (24.5) |

| Unemployed | 220 (22.0) |

| Student | 119 (11.9) |

| Laborers | 112 (11.2) |

| Domestic works | 3 (0.3) |

| Other | 5 (0.5) |

| Residence | |

| City | 596 (59.5) |

| Rural area | 405 (40.5) |

| Monthly income* | |

| Under ¥3000 (US$471.9) | 223 (22.3) |

| ¥3001-8000 (US$472.1-US$1258.4) | 630 (63.0) |

| ≥¥8001 (US$1258.4) | 148 (14.7) |

*¥=Yuan(China), US$=dollar(USA).

Knowledge and Attitudes Toward HPV

Details of the respondents’ knowledge of HPV are reported in Table 2. Only 44.9% (n = 449) of respondents had heard of HPV, and the majority (77.1%) associated HPV with cervical cancer, followed by genital warts (32.4%), sexually transmitted diseases (30.7%), and HIV (8.3%). Among those aware of the HPV, nearly 81.1% believed that the HPV infection is harmful. Furthermore, over half of the women (50.3%) knew that men could also be infected by the HPV. Unfortunately, only 39.2%, 16.3%, and 23.2% of the patients correctly responded to the questions on HPV transmission, prevalence, and symptoms, respectively. Those items were used to measure HPV awareness. When the patients were asked “To what extent is the HPV infection dangerous?” those who lived in the city, highly educated, and engaged in professional jobs, including white-collar workers and professionals, had a higher correct response rate (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in terms of the percentage of correct answers within this group for the 2 questions: “How is HPV transmitted?” and “What is the prevalence of HPV in the population?” As shown in Table 3, the higher the respondent’s education, the higher the percentage of correct answers to the following question: “Do you think that HPV infection can cause discomfort?” For the question “Do you think that men can be infected by HPV?” the respondent’s place of residence, occupation, and education level were closely associated with the percentage of correct answers (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Knowledge of HPV Among the Participants (N = 1001).a

| Item | nb = 449 (%) | Correctly Answered, nc (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Q2: Have you ever heard of the HPV (Yes)? | 449 (44.9) | - |

| Sexually transmitted diseases | 138 (30.7) | - |

| Genital warts | 144 (32.4) | |

| Cervical cancer | 346 (77.1) | |

| HIV | 39 (8.7) | |

| No knowledge of HPV | 59 (1.3) | |

| Q3: What are the risks of HPV infection? | ||

| High risk | 364 (81.1) | 364 (81.1) |

| Low risk | 22 (4.9) | |

| No risk | 1 (0.2) | |

| Not clear | 80 (17.8) | |

| Q4: How is the HPV transmitted? | ||

| Sexual contact | 185 (41.2) | 176 (39.2) |

| Indirect contact | 7 (1.6) | |

| Both | 176 (39.2) | |

| Not clear | 81 (18.0) | |

| Q5: What is the prevalence of the HPV in the population? | ||

| More than 90% | 10 (2.2) | 73 (16.3) |

| 70%-90% | 29 (6.5) | |

| 50%-70% | 68 (15.1) | |

| 30%-50% | 83 (18.5) | |

| Less than 30% | 73 (16.3) | |

| Not clear | 186 (41.4) | |

| Q6: Do you think that infection with HPV causes discomfort? | ||

| Yes | 250 (55.7) | 104 (23.2) |

| No | 104 (23.2) | |

| Not clear | 95 (21.1) | |

| Q7: Do you think that men can be infected by HPV? | ||

| Yes | 226 (50.3) | 226 (50.3) |

| No | 52 (11.6) | |

| Not clear | 171 (38.1) | |

Abbreviation: HPV, human papillomavirus.

a N is the total number of participants.

b n denotes the number of the participants who had heard of HPV.

c n denotes the number of the participants who correctly answered the below questions.

Table 3.

Factors Associated With the Knowledge of HPV (N = 1001, n = 449).a,b

| Q3, n1 = 346 | Q4, n2 = 176 | Q5, n3 = 73 | Q6, n4 = 104 | Q7, n5 = 226 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | |||||

| Education | |||||

| Junior school or lower | 42 (12.1%) | 20 (11.4%) | 11 (15.1%) | 11 (10.6%) | 18 (8.0%) |

| High school | 94 (27.2%) | 50 (14.5%) | 11 (15.1%) | 20 (19.2%) | 60 (26.5%) |

| Undergraduate or higher | 210 (60.7%) | 106 (60.2%) | 51 (69.2%) | 73 (70.2%) | 148 (65.5%) |

| χ2 | 17.104 | 4.764 | 6.462 | 8.746 | 23.301 |

| P | <0.001 | 0.092 | 0.04 | 0.013 | <0.001 |

| Occupation | |||||

| Unemployed | 43 (12.4%) | 21 (11.9%) | 8 (11.0%) | 12 (11.5%) | 33 (14.6%) |

| Laborer | 18 (5.2%) | 7 (4.0%) | 3 (4.1%) | 4 (3.8%) | 18 (8.0%) |

| White-collar workers and civil servants | 126 (36.4%) | 66 (37.5%) | 25 (34.2%) | 34 (32.7%) | 77 (34.1%) |

| Professional | 120 (34.7%) | 66 (37.5%) | 31 (42.5%) | 45 (43.3%) | 89 (39.4%) |

| Farmer | 3 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Student | 35 (10.1%) | 16 (9.1%) | 6 (8.2%) | 8 (7.7%) | 18 (8.0%) |

| Others | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| χ2 | 15.413 | 10.894 | 4.959 | 7.931 | 17.612 |

| P | 0.017 | 0.092 | 0.549 | 0.243 | 0.007 |

| Residence | |||||

| City | 250 (72.3%) | 129 (73.3%) | 52 (71.2%) | 79 (76.0%) | 164 (72.6%) |

| Countryside | 96 (27.7%) | 47 (26.7%) | 21 (28.8%) | 25 (24.0%) | 62 (27.4%) |

| χ2 | 11.698 | 3.529 | 0.381 | 3.804 | 4.086 |

| P | 0.001 | 0.06 | 0.437 | 0.051 | 0.043 |

| Monthly income | |||||

| Under ¥3000 (US$471.9) | 58 (16.8%) | 23 (13.1%) | 7 (9.6%) | 12 (11.5%) | 30 (13.3%) |

| ¥3001-8000 (US$472.1-1258.4) | 228 (65.9%) | 125 (71.0%) | 51 (69.9%) | 74 (71.2%) | 153 (67.7%) |

| ≥¥8001 (US$1258.4) | 60 (17.3%) | 28 (15.9%) | 15 (20.5%) | 18 (17.3%) | 43 (19.0%) |

| χ2 | 2.285 | 6.178 | 4.610 | 4.203 | 7.972 |

| P | 0.319 | 0.046 | 0.100 | 0.122 | 0.019 |

Abbreviation: HPV, human papillomavirus.

a N is the total number of participants. n denotes the number of the participants who had heard of HPV. n1, n2, n3, n4, n5 denote the number of the participants who correctly answered the Q3, Q4, Q5, Q6, Q7, respectively.

b Q3: What are the risks of HPV infection? Q4: How is HPV transmitted? Q5: What is the prevalence of HPV in the population? Q6: Do you think that infection with HPV causes discomfort? Q7: Do you think that men can be infected by HPV? χ2: differences in the correct answers of Q3, Q4, Q5, Q6, Q7 stratified according to education, profession, place of residence, and monthly income, respectively. P < .05 indicates statistically significant differences.

Attitudes Toward HPV Vaccination

The majority (83.7%) of respondents expressed their willingness to be vaccinated. With regard to the reasons for the acceptance of HPV vaccination, almost 80.2% of the women said they believed HPV vaccination would be beneficial and feared having HPV infection (47.0%), cervical cancer (46.7%), and genital warts (26.5%), respectively. About 16.3% of respondents reported not consenting to HPV vaccination, and of these, over half (68.7%) cited they worried about the lack of sufficient evidence and recent experience with the vaccine. Over one-third (35.6%) reported concerns about HPV vaccine safety, and approximately 31.3% believed that they would not be in danger of HPV infection. Only 16.6% and 11.7% commented that the source of the HPV vaccine was not very trustworthy and being vaccinated did not constitute an advantage (Table 3).

Expectations for HPV Vaccination

Regarding the respondents’ expectation for the efficacy of HPV vaccination, nearly half the participants expected to achieve a high benefit. Approximately one-third selected the option with “some benefit,” whereas only 1.0% of the respondents thought vaccination had no benefit. When asked “How much are you willing to pay for HPV vaccination?” most respondents chose the lowest price option (<¥200, <US$31.5), and 38.0% indicated that a price of ¥200 to ¥500 (US$31.5-78.7) was acceptable, while 13.0% thought they could afford to pay ¥500 to ¥1000 (US$78.7-157) for HPV vaccination. Only 8.0% reported that they would vaccinate themselves even at a cost of over ¥1000 (US$157; Table 4).

Table 4.

Reasons for Refusal/Acceptance of HPV Vaccination and the Expectation and Accepted Cost.

| Variables | N = 1001 n (%) |

|---|---|

| Have you ever heard of HPV vaccination (Yes)? | 280 (28.0) |

| Are you willing to receive HPV vaccination (Yes)? | 838 (83.7) |

| Reasons for refusal | n = 163 |

| I do not believe that I will be in danger of HPV | 51 (31.3) |

| There is no difference in being vaccinated or not | 19 (11.7) |

| HPV vaccines have not yet been promoted in large areas | 112 (68.7) |

| HPV vaccination is associated with different degrees of risk | 58 (35.6) |

| The source of the HPV vaccine is not very trustworthy | 27 (16.6) |

| Reasons for of acceptance | n = 838 |

| I will benefit from it | 671 (80.2) |

| I fear of infection with HPV | 391 (46.7) |

| I fear of getting cervical cancer | 393 (47.0) |

| I fear of getting genital warts | 222 (26.5) |

| Expectations | |

| High benefit | 517 (51.6) |

| More or less benefit | 359 (35.9) |

| A little benefit | 42 (4.2) |

| No benefit | 11 (1.1) |

| Do not know | 72 (7.2) |

| Accepted costs | |

| <¥200 (<US$31.5) | 416 (41.6) |

| ¥200-500 (US$31.5-78.7) | 382 (38.2) |

| ¥500-1000 (US$78.7-157) | 126 (12.6) |

| >¥1000 (US$157) | 77 (7.7) |

Abbreviation: HPV, human papillomavirus.

Predictors of the Participants’ Attitudes Toward HPV Vaccination

Table 5 presents the associations between predictor variables and attitudes toward HPV vaccination. In the univariate analysis, the respondents with higher education and higher monthly income were significantly more likely to consent to vaccination (P = .002 and P = .001). Moreover, respondents who lived in the city and were engaged in professional jobs were more willing to be vaccinated (P < 0.001). Only those who thought that it is dangerous to have HPV infection were significantly associated with consenting to vaccination (P < .001), whereas the remaining questions were not significantly associated with vaccination consent.

Table 5.

Factors Associated With Consent.a

| Sociodemographic | Consent, n | Nonconsent, n | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | ||||

| Junior school or under | 199 | 55 | 15.305 | <.001 |

| High school | 240 | 57 | ||

| Undergraduate or higher | 399 | 51 | ||

| Profession | ||||

| Unemployed | 184 | 36 | 29.186 | <.001 |

| Laborers | 76 | 36 | ||

| White-collar workers and civil servants | 260 | 38 | ||

| Professionals | 213 | 32 | ||

| Domestic workers | 3 | 0 | ||

| Student | 100 | 19 | ||

| Others | 2 | 2 | ||

| Residence | ||||

| City | 530 | 66 | 29.330 | <.001 |

| Countryside | 308 | 97 | ||

| Monthly income | ||||

| Under ¥3000 (US$471.9) | 165 | 58 | 20.467 | <.001 |

| ¥3001-8000 (US$472.1-1258.4) | 548 | 82 | ||

| ≥¥8001 (US$1258.4) | 125 | 23 | ||

| Knowledge of HPVb | ||||

| Q3 | ||||

| Correct | 318 | 28 | 19.958 | <.001 |

| Incorrect | 78 | 25 | ||

| Q4 | ||||

| Correct | 157 | 18 | 0.635 | .426 |

| Incorrect | 239 | 35 | ||

| Q5 | ||||

| Correct | 66 | 7 | 0.411 | .522 |

| Incorrect | 330 | 46 | ||

| Q6 | ||||

| Correct | 96 | 300 | 2.198 | .134 |

| Incorrect | 8 | 45 | ||

| Q7 | ||||

| Correct | 202 | 194 | 0.613 | .434 |

| Incorrect | 24 | 29 | ||

Abbreviation: HPV, human papillomavirus.

aP < .05 indicates statistically significant differences.

b Q3: What are the risks of HPV infection? Q4: How is HPV transmitted? Q5: What is the prevalence of HPV in the population? Q6: Do you think that infection with HPV will cause discomfort? Q7: Do you think that men can be infected by HPV?

Discussion

There are a few studies simultaneously evaluating HPV prevalence, HPV awareness, and attitudes toward HPV vaccination among women aged 20 to 35 years in Mainland China. To the best of our knowledge, only one previous study has investigated the HPV prevalence, HPV awareness, and attitudes toward HPV vaccination among women aged 14 to 59 years, but this study was conducted 9 years ago. However, previous population-based studies have described HPV prevalence,28-34 knowledge, and attitudes regarding HPV and vaccination in women <25 years.35,27 In this study, the population consisted of women aged 20 to 35 years, and the cervical samples showed that these women had a relatively high prevalence of HPV positivity, although the rate of abnormal cervical lesions was low36; thus, vaccination would have a stronger impact on this age group in China wherein the HPV vaccine has only been recently introduced, although it is well acknowledged the best stage to get vaccinated is before sexual debut. In addition, this age group in China is sexually active, which means that these women would also be more exposed to the HPV; furthermore, they are within the recommended vaccination age. The World Health Organization has published guidelines for cervical cancer screening and care. These guidelines are mindful of the limited resources in poor regions and are pragmatically focused on women aged 30 to 50 years.37 Furthermore, cervical cancer mortality among young urban females has been increasing by 4.1% per year.38 Thus, the missed rate of cervical cancer in young women <30 years should warrant greater attention. Primary screening for cervical cancer has been limited to women >30 years, so HPV vaccination in younger women aged 20 to 30 years could be more relevant as HPV vaccines may have potential for a higher-than-average impact on this age group in China. Thus, it is important to assess the knowledge and attitudes regarding HPV and vaccination among Chinese women aged 20 to 35 years.

Our findings demonstrated that the rate of HPV infection among our sample of young women aged 20 to 35 years was 15.7%, which is consistent with previous studies. A survey based on 13 Chinese medical centers with 30 207 cases reported an HPV infection rate of 17.7%, while the age-standardized prevalence rate has been reported to be 16.8%.24 Reports from different regions of Mainland China have stated that the HPV prevalence rate was 18.4% in Shenzhen city,25 13.3% in Zhejiang Province, and 14.8% in Shanxi Province26; however, the prevalence is higher than that in neighboring countries (6.2% in Southeast Asia, 6.6% in South Central Asia, and 8.0% in other Asian countries).39,40 The reasons for the higher prevalence may be that China is a developing country with low economic levels and that HPV vaccination has more recently been approved in China compared with the other countries. In our study, nearly 44.9% of the patients were aware of HPV, which is slightly higher than the rates reported by another study from China, according to which 39.6% of patients had heard of HPV.41 In contrast, a multicenter survey revealed that only 24% had previous knowledge of HPV.42 Moreover, in a similar study among university students, only 10.3% of women had previously heard of HPV.12 Possible reasons for this inconsistency include different study populations. For example, in our study, we selected sexually active women aged 20 to 35 years who may be more sensitive to information regarding sexually transmitted diseases. It is also possible that the recent promotion of cervical cancer screening programs may have increased HPV awareness. Knowledge of HPV varies widely depending on the region of residence, sociodemographic factors, and education levels.11,12 Unfortunately, it was also clear from our study that accurate, detailed knowledge about HPV was lacking. Although almost half of the study population had heard of HPV, knowledge gaps existed regarding transmission, risks, whether or not HPV could infect male individuals and especially in terms of the HPV prevalence and symptoms of HPV infection.

Our survey found low levels of HPV-related knowledge among young women, but their high acceptance (83.7%) of HPV vaccination was promising. Zou et al surveyed the knowledge and attitudes toward HPV and vaccination among university students in Jinan, China, and found only 10.3% had previously heard of HPV, but male and female students were equally likely to accept HPV vaccination (71.8% vs 69.4%).15 In our study, the first 3 reasons for not consenting to vaccination were the limited experience with the vaccine to date (68.7%), safety concerns (35.6%), and the belief that they were in no danger of HPV infection (31.3%). Another study targeting urban employed women and female undergraduate students in China demonstrated concerns with the safety of the HPV vaccine (40.1%), its efficacy (28.9%), and the limited experience in its use to date (22.5%).13

What factors influenced attitudes toward HPV vaccination? Previous studies have indicated that an effective HPV education program addressing specific knowledge gaps and common questions among women of different regions, education levels, and cultures increased the success of large-scale vaccination programs.43 However, it is unclear what aspect in the knowledge of education programs should be addressed. Studies from the United States have indicated that educational programs should emphasize vaccine effectiveness and the high likelihood of HPV infection and address barriers to vaccination.12 In this study, education levels, different professions, different residences, monthly income levels, the knowledge of HPV, and awareness of the dangers of HPV infection seriously affected the vaccination rate among the women. Except for the knowledge of HPV, it is difficult to address the other factors in such a short period of time.

Our results confirm the importance of health education on the safety and efficacy of vaccination. Above all, the content of health education should focus on the dangers of HPV infection. Moreover, our study found that the price that women were willing to pay for the vaccine was lower than the current price of the vaccine in China (¥580/dose). There is a requirement of 3 doses, which means that the price is a strong barrier for the promotion of HPV vaccinations. In Hong Kong, Chiang et al determined that the majority of women were inclined to pay the lowest available option (<US$500) and the price of the vaccine should be set at an affordable level in relation to its efficacy.43 This study simultaneously evaluated HPV prevalence, HPV knowledge, and attitudes toward HPV vaccination among women aged 20 to 35 years from the general population in Mainland China. Of note, we investigated current knowledge regarding HPV among women to identify specific gaps in information on HPV and what HPV information would most strongly impact women’s willingness to be vaccinated. The majority of the survey questions herein had been used several times before in China,19 and the new questions allowed gathering unique and invaluable information.

Limitations

Patients were given self-administered questionnaires, and some respondents may not have fully understood the questions, resulting in potential bias, although we provided assistance via professional staff if they required help. Regrettably, we did not investigate the form of educational programs they preferred and where they would be willing to get the vaccine. What is more, the possibility of misclassification and lack of comparability of results to those from prior relevant studies due to the use of a nonstandard instrument. Further studies should be carried out to address these issues.

Conclusions

In our study, the HPV prevalence is relatively high among women aged 20 to 35 years in Fujian Province, China. Despite 44.9% of these women being aware of HPV, detailed knowledge about HPV was lacking when compared to women from the United States and Hong Kong. The potential implications of our study are far reaching during this pivotal time of HPV vaccine being available in China. Though the introduction of the HPV prophylactic vaccine would prevent cervical cancer among Chinese women, to ensure the effectiveness of vaccination campaigns, the government and some relevant departments must first develop appropriate educational interventions for women aged 20 to 35 years, especially to emphasize the risk between HPV and cervical cancer or other related diseases, as well as determine how to subsidize the vaccine costs. Lastly, follow-up studies must be performed to determine whether increased HPV and HPV vaccine knowledge translates into higher vaccination rates and vaccine compliance within China.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Maternity and Children’s Health Hospital of Xianyou, Maternity and Children’s Health Hospital of Shaowu, Maternity and Children’s Health Hospital of Nanping, Maternity and Children’s Health Hospital of Shishi, Maternity and Children’s Health Hospital of Jinjiang, and Maternity and Children’s Health Hospital of Fuqing for helping with data collection.

Authors’ Note: Pengming Sun contributed as study coordinator and contributed to data analysis, funding acquisition, supervision, writing –review, editing, and manuscript; Yiyi Song contributed as study coordinator and contributed to funding acquisition and draft of the manuscript; Lihua Chen contributed to data analysis and drafted the manuscript; Guanyu Ruan, Qiaoyu Zhang, and Fen Li contributed to data collection and validation. Jian An and Binhua Dong contributed to data collection. Jun Zhang and Ting Wu contributed as study coordinator and contributed to data curation. All authors were involved in the critical review and approval of the manuscript. Lihua Chen and Yiyi Song contributed equally in this work.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was funded by the Fujian Provincial Key Projects in Science and Technology (Grant no. 2015YZ0002) and Provincial Natural Science Foundation of Fujian, China (2017J01232).

References

- 1. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mishra GA, Pimple SA, Shastri SS. An overview of prevention and early detection of cervical cancers. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2011;32(3):125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189(1):12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bosch FX, Lorincz A, Munoz N, Meijer CJ, Shah KV. The causal relation between human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55(4):244–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sun P, Song Y, Ruan G, et al. Clinical validation of the PCR-reverse dot blot human papillomavirus genotyping test in cervical lesions from Chinese women in the Fujian province: a hospital-based population study. J Gynecol Oncol. 2017;28(5):e50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baloch Z, Li Y, Yuan T, et al. Epidemiologic characterization of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in various regions of Yunnan Province of China. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. American Association for Cancer Research. HPV vaccine less effective in “older” women. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(4):OF6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sander BB, Rebolj M, Valentiner-Branth P, Lynge E. Introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination in Nordic countries. Vaccine. 2012;30(8):1425–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wamai RG, Ayissi CA, Oduwo GO, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of a community-based sensitization strategy in creating awareness about HPV, cervical cancer and HPV vaccine among parents in North West Cameroon. J Community Health. 2012;37(5):917–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li J, Li LK, Ma JF, et al. Knowledge and attitudes about human papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV vaccines among women living in metropolitan and rural regions of China. Vaccine. 2009;27(8):1210–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wigle J, Coast E, Watson-Jones D. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine implementation in low and middle-income countries (LMICs): health system experiences and prospects. Vaccine. 2013;31(37):3811–3817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Medina DM, Valencia A, de Velasquez A, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: a randomized, controlled trial in adolescent girls. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(5):414–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang W, Ma Y, Wang X, et al. Acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccine among parents of junior middle school students in Jinan, China. Vaccine. 2015;33(22):2570–2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zou H, Wang W, Ma Y, et al. How university students view human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination: a cross-sectional study in Jinan, China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(1):39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang Y, Wang Y, Liu L, et al. Awareness and knowledge about human papillomavirus vaccination and its acceptance in China: a meta-analysis of 58 observational studies. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang SK, Pan XF, Wang SM, et al. Knowledge of human papillomavirus vaccination and related factors among parents of young adolescents: a nationwide survey in China. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(4):231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. HPV Vaccination Coverage by Dose 2013. National HPV Vaccination Program Register. 2015. http://www.hpvregister.org.au/research/coverage-data/HPV-Vaccination-Coverage-by-Dose-20132. Updated June 2015.

- 19. Annual HPV Vaccine coverage 2013 to 2014: by PCT, local authority and area team. Public Health England. 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/annual-hpv-vaccine-coverage-2013-to-2014-by-pct-local-authority-and-area-team. Updated December 2, 2014.

- 20. Slåttelid Schreiber SM, Juul KE, Dehlendorff C, Kjær SK. Socioeconomic predictors of human papillomavirus vaccination among girls in the Danish Childhood Immunization Program. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(4):402–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li SL, Lau YL, Lam TH, Yip PS, Fan SY, Ip P. HPV vaccination in Hong Kong: uptake and reasons for non-vaccination amongst Chinese adolescent girls. Vaccine. 2013;31(49):5785–5788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Choi HC, Leung GM, Woo PP, Jit M, Wu JT. Acceptability and uptake of female adolescent HPV vaccination in Hong Kong: a survey of mothers and adolescents. Vaccine. 2013;32(1):78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kwan TT, Chan KK, Yip AM, et al. Barriers and facilitators to human papillomavirus vaccination among Chinese adolescent girls in Hong Kong: a qualitative-quantitative study. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84(3):227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hu SY, Hong Y, Zhao FH, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and attitudes towards HPV vaccination among Chinese women aged 18–25 in Jiangsu Province. Chin J Cancer Res. 2011;23(1):25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wu RF, Dai M, Qiao YL, et al. Human papillomavirus infection in women in Shenzhen City, People’s Republic of China, a population typical of recent Chinese urbanisation. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(6):1306–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jin Q, Shen K, Li H, Zhou XR, Huang HF, Leng JH. Age-specific prevalence of human papillomavirus by grade of cervical cytology in Tibetan women. Chin Med J (Engl). 2010;123(15):2004–2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wu E, Tiggelaar SM, Jiang T, et al. Cervical cancer prevention-related knowledge and attitudes among female undergraduate students from different ethnic groups within China, a survey-based study. Women Health. 2017;22:1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhao FH, Forman MR, Belinson J, et al. Risk factors for HPV infection and cervical cancer among unscreened women in a high-risk rural area of China. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(2):442–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li LK, Dai M, Clifford GM, et al. Human papillomavirus infection in Shenyang City, People’s Republic of China: a population-based study. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(11):1593–1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Belinson J, Qiao YL, Pretorius R, et al. Shanxi province cervical cancer screening study: a cross-sectional comparative trial of multiple techniques to detect cervical neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;83(2):439–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dai M, Bao YP, Li N, et al. Human papillomavirus infection in Shanxi Province, People’s Republic of China: a population-based study. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(1):96–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shi JF, Wu RF, Liu ZH, et al. [Distribution of human papillomavirus types in Shenzhen women]. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2006;28(6):832–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhang X, Wang CY, Shi JF, Gao Y, Li LK. [Study on the prevalence of human papillomavirus infection and distribution of types in Shenyang city]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2007;28(10):954–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhao R, Zhang WY, Wu MH, et al. Human papillomavirus infection in Beijing, People’s Republic of China: a population-based study. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(9):1635–1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tung IL, Machalek DA, Garland SM. Attitudes, knowledge and factors associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake in adolescent girls and young women in Victoria, Australia. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0161846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li X, Zheng R, Li X, et al. Trends of incidence rate and age at diagnosis for cervical cancer in China, from 2000 to 2014. Chin J Cancer Res. 2017;29(6):477–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goodman A. HPV testing as a screen for cervical cancer. BMJ. 2015;350:h2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhao FH, Hu SY, Zhang SW, Chen WQ, Qiao YL. [Cervical cancer mortality in 2004 - 2005 and changes during last 30 years in China]. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2010;44(5):408–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. de Sanjose S, Diaz M, Castellsague X, et al. Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(7):453–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sukvirach S, Smith JS, Tunsakul S, et al. Population-based human papillomavirus prevalence in Lampang and Songkla, Thailand. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(8):1246–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhao FH, Tiggelaar SM, Hu SY, et al. A multi-center survey of HPV knowledge and attitudes toward HPV vaccination among women, government officials, and medical personnel in China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(5):2369–2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brewer NT, Fazekas KI. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: a theory-informed, systematic review. Prev Med. 2007;45(2-3):107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chiang VC, Wong HT, Yeung PC, et al. Attitude, acceptability and knowledge of HPV vaccination among local university students in Hong Kong. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(5): E486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]