Abstract

Background

Heavy drinking among college students is a significant public health concern that can lead to profound social and health consequences, including alcohol use disorder. Behavioral economics posits that low future orientation and high valuation of alcohol (alcohol demand) combined with deficits in alternative reinforcement increase the likelihood of alcohol misuse (Bickel et al., 2011). Despite this, no study has examined the incremental utility of all three variables simultaneously in a comprehensive model.

Method

The current study uses structural equation modeling to test the associations between behavioral economic variables – alcohol demand (latent), future orientation (measured with a delay discounting task and the Consideration of Future Consequences (CFC) scale), and proportionate substance-related reinforcement – and alcohol consumption and problems among 393 heavy drinking college students. Two models are tested: 1) an iteration of the reinforcer pathology model that includes an interaction between future orientation and alcohol demand; and 2) an alternative model evaluating the interconnectedness of behavioral economic variables in predicting problematic alcohol use.

Results

The interaction effects in model 1 were nonsignificant. Model 2 suggests that greater alcohol demand and proportionate substance-related reinforcement is associated with greater alcohol consumption and problems. Further, CFC was associated with alcohol-related problems and lower proportionate substance-related reinforcement but was not significantly associated with alcohol consumption or alcohol demand. Finally, greater proportionate substance-related reinforcement was associated with greater alcohol demand.

Conclusions

Our results support the validity of the behavioral economic reinforcer pathology model as applied to young adult heavy drinking.

Keywords: Behavioral economics, Delay discounting, College student heavy drinking, Demand

Heavy drinking (≥ 4/5 drinks in a sitting for women/men) has been the focus of research for more than four decades, yet remains a significant public health concern (Hingson et al., 2017). College students are among the highest risk demographic group given their persistently high levels of drinking (White and Hingson, 2013), a phenomenon associated with consequences ranging from mild/moderate (e.g., embarrassment, interpersonal conflict, and hangovers) to severe (e.g., academic impairment, blackouts, driving while intoxicated, and death; Hingson et al., 2009).

Heavy Drinking as a Reinforcer Pathology

Behavioral economics combines principles and methods from microeconomics and operant behavioral psychology to understand patterns of behavior over time (Bickel et al., 2014). Two primary reinforcement processes are thought to contribute to repeated choices to drink heavily despite experiencing negative consequences (Bickel et al., 2014): 1) a tendency to devalue the future in favor of the present (delay discounting); and 2) consistent overvaluation for alcohol (greater relative reinforcing efficacy), which may be due in part to diminished availability of alternative drug-free reinforcers in one’s environment. Because increasing alcohol and drug use exacerbates these risk factors, via the direct effects of drugs on the brain and the adverse social/educational effects of frequent alcohol and drug use, this process is self-perpetuating. Thus, alcohol misuse is viewed as reinforcer pathology, wherein there is excessive motivation to engage in drinking behavior relative to other possible activities that might be associated with delayed health, social, or monetary rewards (Bickel et al., 2014, 2011).

Future Valuation

The tendency to devalue or “discount” delayed reinforcers is a widely documented, cross-species phenomenon that is especially pronounced among teens/young adults and individuals who misuse alcohol and other drugs (Olson et al., 2007). Frequent drug use appears to be one manifestation of a more general tendency to choose relatively smaller, immediate rewards (i.e., alcohol or drugs) rather than larger, delayed rewards (i.e., college graduation, career). Greater reported delay discounting is consistently associated with a range of substance use and problems (Aston et al., 2016; Kirby and Petry, 2004), significantly predicts alcohol use disorder among heavy drinking community adults (Mackillop et al., 2010), and predicts GPA and academic engagement among heavy drinking college students (Acuff et al., 2017), suggesting that delay discounting distinguishes incremental levels of risk in already heavy substance using samples.

Despite the robust relations in community and clinical samples, studies examining the relation between delay discounting and alcohol use among college students have yielded less consistent results (Dennhardt and Murphy, 2011; Lemley et al., 2016; Teeters and Murphy, 2015; Vuchinich and Simpson, 1998), as has research with adolescent and community young adult populations (Herting et al., 2010). There are several possible explanations for these differences. First, delay discounting displays a more robust relation with severe alcohol misuse (Amlung et al., 2017), possibly due to neural and genetic correlates (Mackillop, 2016), and heavy drinking among college students may be more related to social-contextual factors that encourage drinking. Second, most college students remain somewhat financially dependent on their parents and have not engaged in personal financial decisions related to saving/investing money frequently enough to adequately weigh the value of different monetary amounts distinguished by delay. They may also expect an increase in future income following graduation which could alter the relative value of immediate versus delayed monetary amounts. Consequently, their choices on these tasks may be less representative of their more general ability to consider future outcomes or delay gratification. Thus, in order to evaluate the reinforcer pathology model with college students, there is a need to consider alternate measures of the more general tendency to organize one’s behavior around future outcomes.

The Consideration of Future Consequences (CFC) scale was developed to represent the degree to which an individual considers future outcomes when making decisions about current behavior (Strathman et al., 1994) and includes items such as “My behavior is only influenced by the immediate outcomes of my actions” answered on a likert scale. The construct is conceptually similar to, but empirically only weakly related to, delay discounting (Teuscher and Mitchell, 2011) and has shown significant relations with unhealthy behaviors, including substance misuse (Daugherty & Brase, 2010; Vuchinich & Simpson, 1998), though it has not yet been evaluated as part of a comprehensive behavioral economic model predicting alcohol misuse. One study found that lower CFC scores predicted higher levels of drinking 6-months later in a sample of heavy drinking college students (Murphy et al., 2012).

Relative Reinforcing Efficacy

Behavioral economic models suggest that the reinforcing properties of a drug, or reinforcing efficacy, is central to understanding substance misuse, and that persistent, high valuation of a substance or commodity is a primary factor in the etiology and maintenance of addictive behaviors. Behavioral economics typically quantifies relative reinforcing efficacy using demand curve approaches that plot consumption as a function of price or response cost (Hursh and Silberberg, 2008; Murphy and MacKillop, 2006). The most common approach in applied human studies uses hypothetical alcohol purchase tasks in which participants report the number of standard alcoholic drinks they would consume across a series of escalating prices. Consumption and expenditures are then plotted as a function of price, creating demand and expenditure curves from which several demand indices can be extracted, including the consumption level when the price is free (intensity), the slope of deceleration as a function of change in price (elasticity), and the point of highest expenditure (Omax). Greater demand for alcohol is associated with greater reported alcohol and drug consumption (Aston et al., 2016; Bertholet et al., 2015), and also problems related to substance use (Bertholet et al., 2015; Teeters and Murphy, 2015).

The above research suggests that devaluation of the future and greater valuation of alcohol (demand) are both robust factors associated with alcohol misuse. These two factors have been presumed to interact to influence alcohol misuse (Bickel et al., 2014), but recent studies have not supported this interaction (Aston et al., 2016; Lemley et al., 2016). Although demand and delay discounting both seem to play an important part in the etiology and maintenance of substance misuse, these roles may be independent rather than additive.

Alternative Substance-Free Reinforcement

Laboratory and applied research suggests that preference for alcohol and other drugs is inversely related to the availability of rewarding alternatives available in the environment (Higgins et al., 2004; Murphy and Dennhardt, 2016). Individuals with limited access to alternatives, or a diminished capacity to experience reward (anhedonia), are more likely to over-value drug-rewards and subsequently engage in substance use. For example, a lack of substance-free reward predicts binge drinking among college students (Correia et al., 2003), and the ratio between substance-free and substance-related rewards predicts drinking behavior following a brief intervention (Murphy et al., 2005). Joyner and colleagues (2016) recently found evidence for increased risk for alcohol use disorder (AUD) among college students with diminished access to environmental reward. Other epidemiological research suggests that poverty is a robust risk factor for substance misuse (Galea et al., 2004), and recent research suggests that, among teens, this is at least partially due to the lack of alternative reinforcement available in economically disadvantaged environment (Andrabi et al., 2017). Despite alternative reinforcement’s potential role in the reinforcer pathology model, to our knowledge, no other study has examined delay discounting, demand, and alternative reinforcement in one cohesive model.

Current Study

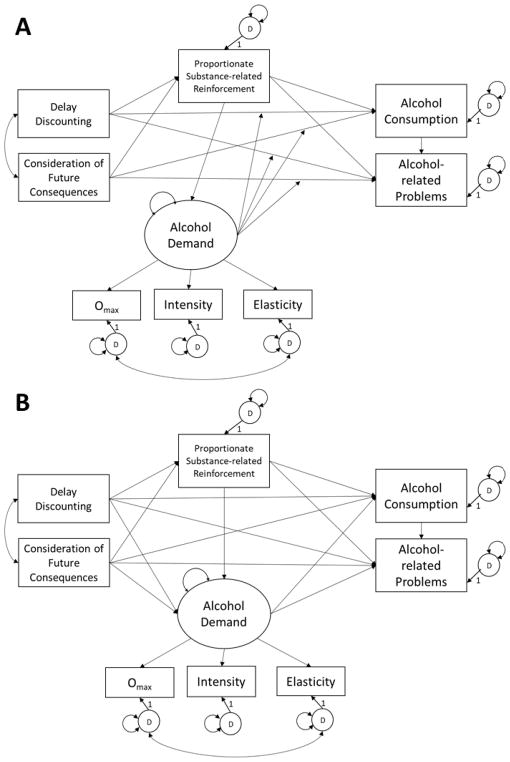

In the current study, we used a structural equation modeling SEM approach to simultaneously model the relations among the three central reinforcer pathology variables and problematic substance misuse. Further, despite consistent and robust findings between delay discounting and substance misuse among general adult samples (Amlung et al., 2017), relations are less consistent among heavy drinking college students (Dennhardt and Murphy, 2011; Teeters and Murphy, 2015). A related construct – CFC – has demonstrated more consistent relations with alcohol misuse and may be useful in measuring the valuation of future outcomes in college populations. We examined two structural regression models exploring the relations between alcohol demand, proportionate substance-related reinforcement, both delay discounting and CFC, and alcohol consumption and related problems. The first model (Model 1) parallels an iteration of the reinforcer pathology model that predicts delay discounting and/or CFC interacting with demand to predict both alcohol consumption and problems, with proportionate substance-related reinforcement included as a separate predictor of both outcomes (Figure 1a). Based on our outcome, we presented an alternative model structure. The alternative conceptual model (Model 2) is presented in Figure 1b. We expected that all behavioral economic constructs would be associated with alcohol consumption, and alcohol consumption and behavioral economic variables would be associated with alcohol-related problems. Further, we expected greater delay discounting and lower CFC would predict greater proportionate substance-related reinforcement and alcohol demand, and greater proportionate substance-related reinforcement would predict greater alcohol demand. Finally, we tested indirect effects for all pathways within the alternative model. Due to the lack of research examining mediation effects among behavioral economic variables, we did not form hypotheses regarding their indirect effects on alcohol consumption or -related problems. Although exploratory, examination of indirect effects may provide insight into how these constructs are interconnected.

Figure 1.

Conceptual models representing a) the reinforcer pathology model and b) an alternative behavioral economic structural regression model. D = Variance unaccounted for by models.

Materials & Method

Participants

Study participants were college students (N = 393) from two large public universities in the Southern and Midwestern United States who reported two or more binge drinking episodes in the last month (≥4/5 standard drinks in one occasion for women/men, respectively). Data were collected as part of the baseline assessment of a clinical trial examining the efficacy of a brief intervention in reducing alcohol consumption and related problems. Participants were 60.8% women and, on average, 18.77 years of age (SD = 1.07). The sample was 78.9% Caucasian, 8.7% Black, 5.5% Non-Black Minority, and 7.1% Multiracial, and 5.9% reported Hispanic ethnicity.

Procedures

All study procedures were approved by both universities’ Institutional Review Boards. Heavy drinking college students were recruited through email surveys, in-class screeners, and a psychology subject pool, a secure cloud based subject pool software for launching studies and collecting data. Participants were deemed eligible if they 1) were freshmen or sophomores; 2) reported two or more binge drinking episodes in the past month; and 3) were full time students who worked less than 20 hours per week. Eligible participants were contacted by study personnel and invited to come into the lab to participate in the clinical trial. After completing the informed consent, participants completed an hour-long baseline assessment survey on a computer in a laboratory and were then randomized to one of three study conditions. This secondary analysis only utilized baseline data collected prior to exposure to any intervention elements.

Measures

Proportionate Substance-related Reinforcement

The reinforcement ratio, a measure of proportionate substance-related reinforcement, is derived from the Adolescent Reinforcement Survey Schedule-Substance Use Version (ARSS-SUV; Murphy, Correia, Colby, & Vuchinich, 2005). The ARSS-SUV asks participants about 32 activities, such as “going on a date”, “studying”, or “hanging out with siblings”. Participants rate the frequency and enjoyment of each activity in two situations: 1) when they are not under the influence of any drugs or alcohol, and 2) when they are under the influence of drugs or alcohol. Frequency is rated on a scale from 0 (0 times) to 4 (more than once a day), and enjoyment is rated on a scale from 0 (unpleasant/neutral) to 4 (extremely pleasant). Frequency and enjoyment ratings are then multiplied together to create a cross-product for both substance-related activities and substance-free activities. The substance-related reinforcement cross-product is divided by the total reinforcement (substance-free reinforcement + substance-related reinforcement) to obtain the proportion of substance-related reinforcement, or reinforcement ratio. Internal consistency in the current sample was excellent for the substance-related reinforcement cross products (α = .94) and good for the substance-free reinforcement cross products (α = .89).

Consideration of Future Consequences

We used a 9-item version of The Consideration of Future Consequences Scale (CFCS; Strathman, Gleicher, Boninger, & Edwards, 1994) to assess participants’ consideration of future outcomes in current decision making. Example items include “I consider how things might be in the future and try to influence those things with my day to day behavior” and “I only act to satisfy my immediate concerns, figuring the future will take care of itself”. Low CFC is associated with numerous unhealthy behaviors (Daugherty and Brase, 2010; Teuscher and Mitchell, 2011), including alcohol misuse (Soltis et al., 2017). Internal consistency in the current sample was adequate (α = .80).

Delay Discounting

We used a modified (60-item) version of the delay discounting task (DDT Amlung & MacKillop, 2011). In previous studies, these items have been administered twice (once in ascending and once in descending order) to check for inconsistency. Items were only presented once to reduce participant burden; however, the trial sequence was identical to the ascending order presented in previous studies. Participants made hypothetical choices between smaller, immediate monetary rewards and larger, delayed rewards. Each item was presented individually, and the items featured varying immediate monetary amounts and delays. The delayed monetary amount was always $100 at delays of 1 day, 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months or 1 year. Each choice contributed to the participant’s overall discounting parameter (k), which was fit to a hyperbolic discounting equation (Mazur and Herrnstein, 1988) using a Graphpad Prism macro. Higher k values indicate a greater preference for smaller, immediate rewards. Nonsystematic responding was identified using Johnson and Bickel’s algorithm (2008). Thirty-five participants (8.9%) met this criterion and were removed. This number is less than the average percentage of nonsystematic responders based on meta-analytic study of inconsistencies in delay discounting research (Smith et al., 2018).

Alcohol Demand

The alcohol purchase task (APT; Murphy & MacKillop, 2006) asks participants to report the number of alcoholic drinks they would purchase and consume at a party between 9:00 PM and 1:00 AM across 20 escalating price points. Although many indices can be calculated using the APT, the current study elected to focus on intensity, elasticity, and Omax, as these have shown good reliability (Acuff and Murphy, 2017; Murphy et al., 2009) and the most robust associations with substance misuse (Murphy et al., 2009; Teeters and Murphy, 2015). Further, hypothetical purchase choices have been shown to correspond to actual choices made with real monetary amounts (Amlung et al., 2012). Intensity is defined as the number of drinks one would consume if they were free, representing unrestrained consumption behavior. Omax is the maximum expenditure reported by a participant during the alcohol purchase task. Reported consumption values are multiplied by each individual price point to obtain expenditure. Elasticity is the rate at which consumption decreases as a function of increasing price. Elasticity is calculated using an exponentiated version of Hursh & Silberberg’s (2008) exponential equation, put forth by Koffarnus and colleagues (2015):

Where Q = quantity consumed, k = the range of the dependent variable (standard drinks) in logarithmic units, P = price, and α = elasticity of demand. For the current study, intensity, Elasticity, and Omax were used to create a latent factor of alcohol demand. Both intensity and Omax load onto the amplitude factor, and elasticity and Omax load onto the persistence factor (MacKillop et al., 2009). Thus, our latent variable includes aspects of both of these overlapping facets of alcohol demand. Elasticity was calculated using Graphpad Prism version 7.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA, www.graphpad.com). To calculate k, we subtracted the log10-transformed average consumption at the highest price from the log10-transformed average consumption at the lowest price. In our sample, k was held constant at 1.84.

Alcohol Consumption

Alcohol consumption was measured with the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins et al., 1985). Participants reported typical alcohol consumption for each day over a week in the last month. We then calculated typical weekly drinking by adding consumption for each day during the week.

Alcohol-related problems

Alcohol-related problems was measured using the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (Read et al., 2006), a 48-item measure that asks about common consequences associated with alcohol use. Examples of items include “I have passed out from drinking” and “while drinking, I have said harsh or cruel things to someone”. Responses (yes/no) are then added to create a total score. The current version of the YAACQ also contained an additional item: “Because of my drinking I have had sex with someone I wouldn’t ordinarily have sex with.” Internal consistency in the current sample was very good (α = .90).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using Mplus v7.4 (Muthén and Muthén, 2015). All variables were checked for outliers, and values exceeding 3.29 standard deviations above the mean were winsorized (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2013). Several cases still heavily skewed the data for Omax following winsorization; for these cases, Omax values were counted as missing and handled using robust maximum likelihood estimation in Mplus. Study variables were all modeled as continuous1 . All variables were checked for normality. Because some variables were not normal, we used robust maximum likelihood estimation (MLR). MLR is an iterative method that produces the most likely solution given the data provided and adjusts the chi-square and standard errors to account for multivariate nonnormality (Yuan and Bentler, 1998). Further, preliminary analyses suggested the presence of seven missing data patterns. Missing data was handled using Full Information Maximization Likelihood (FIML). All tested models were overidentified.

For all models, we report and evaluate four model fit indices for both the measurement and structural models, as suggested by Kline (2016): the model Chi-square, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Bentler’s Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The model Chi-square provides an index of goodness of fit; nonsignificant results indicate good fit. RMSEA favors parsimony, and values with confidence intervals below 0.08 are indicative of acceptable model fit to the data (Hu and Bentler, 1999). The CFI represents the incremental improvement of a given model from a baseline model with no variables (CFI > 0.90 and 0.95 considered acceptable and good, respectively; Hu and Bentler, 1999). Finally, we report SRMR, another measure of goodness of fit, wherein smaller values indicate better fit and values below .08 suggest good model fit to the data (Hu and Bentler, 1999). All variables except proportionate substance-related reinforcement (already a ratio scaled from 0 to 1) were re-scaled to promote convergence. CFC, intensity, Omax, alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related problems were multiplied by 1/10; elasticity was multiplied by 10. The models were adjusted based on model index results, fit statistics, variances, and problems with fixed parameters. The same measurement models were used for analyses for both Models 1 and 2.

Next, we examined two structural regressions. We used one confirmatory structural regressions to test the reinforcer pathology model (Model 1). We then used confirmatory structural regression to evaluate our alternative model (Model 2). The alternative model regresses alcohol consumption onto delay discounting, CFC, proportionate substance-related reinforcement, and alcohol demand. Next, it regresses alcohol-related problems onto alcohol consumption, delay discounting, CFC, proportionate substance-related reinforcement, and alcohol demand. Per our hypotheses, we also regress alcohol demand onto proportionate substance-related reinforcement, delay discounting, and CFC. Finally, we regress proportionate substance-related reinforcement onto delay discounting and CFC. Figure 1 represents our conceptual models.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Study Variables

Demographic information, descriptive statistics, and correlations for study variables can be found in Table 1. Participants reported an average of 17.03 (SD = 13.79) alcohol drinks per typical week and 13.07 (SD = 7.93) alcohol-related problems in the past month. Alcohol consumption and related problems were positively correlated with proportionate substance-related reinforcement, intensity, and Omax. Alcohol-related problems were also negatively correlated with CFC. Proportionate substance-related reinforcement was significantly correlated with CFC and alcohol demand indices in the expected directions; however, it was unrelated to delay discounting. As expected, delay discounting was significantly negatively correlated with CFC, but was unrelated to all other study variables. Finally, all alcohol demand indices were significantly correlated with one another in the expected directions.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix of Study Variables

| N | M (SD) | % | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 381 | 18.77 (1.07) | ||||||||

| 2. Gender (% female) | 393 | 60.8 | ||||||||

| 3. Race (% White) | 393 | 78.9 | ||||||||

| 4. Alcohol consumption | 393 | 17.03 (13.79) | - | |||||||

| 5. Alcohol problems | 393 | 13.07 (7.93) | .36*** | - | ||||||

| 6. rratio | 392 | .34 (.15) | .30*** | .32*** | - | |||||

| 7. CFC | 393 | 30.40 (6.53) | −.07 | −.19*** | −.13** | - | ||||

| 8. Delay discounting | 356 | .0318 (.0573) | .02 | −.04 | .04 | −.12** | - | |||

| 9. Elasticity | 384 | .0123 (.0104) | −.15 | −.14 | −.02 | .05 | .08 | - | ||

| 10. Intensity | 388 | 8.66 (4.25) | .60*** | .32*** | .23*** | −.11* | .13 | −.27*** | - | |

| 11. Omax | 388 | 16.76 (9.67) | .27*** | .17*** | .10* | −.11* | .04 | −.66*** | .43*** |

Note. CFC = Consideration of Future Consequences; r-ratio = Proportionate substance-related reinforcement; N = Sample size; M = Mean; SD – Standard Deviation.

p< .001,

p< .01,

p< .05.

Measurement Model

The original measurement model demonstrated poor fit to the data. The Omax parameter was fixed to one and elasticity was allowed to freely vary. Further, examination of the modification indices suggested that Omax and elasticity shared some variance. Both Omax and elasticity reflect facets of willingness to expend resources to obtain a drink. For this reason, we allowed Omax and elasticity to correlate. This second model demonstrated much stronger fit indices (Table 2). The model chi-square was nonsignificant, RMSEA was below .08, CFI was at 1.00, and the SRMR value was small. Intensity and elasticity both loaded well onto the alcohol demand factor, such that the latent variable was positively associated with intensity (p < .001) and negatively associated with elasticity (p < .001; Omax was fixed to 1).

Table 2.

Model Fit Indices for the tested Measurement and Structural Models

| χ2 (df), p-value | RMSEA | CFI | SRMR | AIC | BIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Model | 9.59 (9), .38 | .01 (.00 & .06) | 1.00 | .02 | 3629.32 | 3768.40 |

| Model 1 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Model 2 | 9.76 (9), .37 | .02 (.00 & .06) | 1.00 | .02 | 3506.27 | 3645.36 |

Note. Model fit indices were not calculated for model 1 due to an interaction involving a latent variable. df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = Steiger-Lind Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; CFI = Bentler’s Comparative Fit Index; SRMR = Standardized Root Mean Square Residual.

Reinforcer Pathology Structural Regression

The reinforcer pathology structural model indicated that neither delay discounting nor CFC interacted with alcohol demand to predict alcohol consumption or problems in the full model (Figure 1). As such, we provide an alternative model of reinforcer pathology.

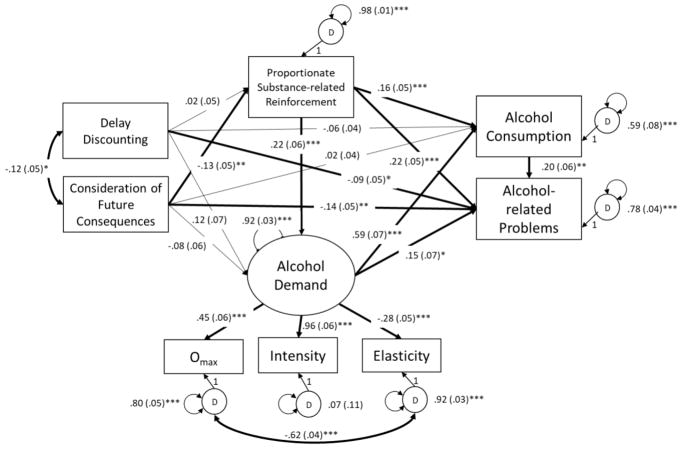

Alternative Behavioral Economic Structural Regression

We used an identical measurement model for the alternative model as described above (Table 2). Greater alcohol demand was significantly associated with greater alcohol consumption (p < .001) and alcohol-related problems (p = .03). Greater proportionate substance-related reinforcement was associated with greater alcohol consumption (p < .001) and alcohol-related problems (p < .001). Proportionate substance-related reinforcement was associated with greater alcohol demand (p < .001). Delay discounting showed non-significant trend level associations with alcohol demand in the expected direction (p = .09); however, delay discounting was not associated with proportionate substance-related reinforcement (p = .68) and was, unexpectedly, negatively associated with alcohol-related problems (p = .04)2 . CFC was negatively associated with alcohol-related problems (p < .01) and proportionate substance-related reinforcement (p = .01); however, CFC was not associated with alcohol demand (p = .17) or alcohol consumption (p = .58). As expected, alcohol consumption was also significantly associated with alcohol-related problems (p = .001)3 .

We also examined indirect effects. CFC demonstrated an indirect effect on alcohol-related problems (estimate = −.03, p = .02) and alcohol consumption (estimate = −.02, p < .03) through proportionate substance-related reinforcement. Further, CFC had an indirect effect on alcohol consumption through the pathway from CFC to proportionate substance-related reinforcement to alcohol demand to alcohol consumption (estimate = −.02, p = .03). Proportionate substance-related reinforcement had an indirect effect through alcohol demand on alcohol consumption (estimate = 1.09, p < .001) and alcohol-related problems (estimate = .19, p = .053). Finally, alcohol demand had an indirect effect on alcohol-related problems through alcohol consumption (estimate = .21, p = .003). No other possible indirect effect was significant.4

Discussion

The current study is the first to evaluate a comprehensive and integrated behavioral economic reinforcer pathology model (Bickel et al., 2014) predicting alcohol consumption and -related problems utilizing structural equation modeling in a large sample (N = 393) of heavy drinking college students. Using this statistical approach, behavioral economic variables were modeled simultaneously as predictors, allowing for direct analysis of the incremental utility of each behavioral economic variable, contrary to previous studies using simpler univariate or covariate approaches. The results support continued inquiry into the reinforcer pathology model and demonstrate the importance of the three-primary behavioral economic variables (alcohol demand, future valuation, and proportionate substance-related reinforcement) in predicting alcohol misuse among young adult heavy drinkers.

The reinforcer pathology model hypothesizes that the interaction of future valuation and alcohol demand creates synergistic risk for addiction (Bickel et al., 2014, 2011). Our findings do not support this interactive effect in predicting alcohol consumption or -related problems. The current study, as well as two others finding null results (Aston et al., 2016; Lemley et al., 2016), were conducted with college student substance users and suggest that among young adults the behavioral economic factors confer unique and independent risk for substance abuse. The interaction effect - where the risk associated with elevated alcohol reward value is greater in the presence of elevated delay discounting - may exist among more severe populations, especially considering that the relation between delay discounting and substance misuse becomes stronger as severity increases (Amlung et al., 2017).

The alternative model provided another evaluation of the predictive utility of behavioral economic variables and reflected the relations generally found in the literature. For example, greater alcohol demand was associated with greater alcohol consumption, which has been found in multiple studies (Bertholet et al., 2015; Murphy and MacKillop, 2006). Further, greater proportion of reinforcement from alcohol-related activities relative to other activities in one’s environment was associated with greater alcohol consumption, replicating previous research connecting substance use to a lack of alternative reinforcement (Andrabi et al., 2017; Correia et al., 2003; Murphy et al., 2009). Interestingly, neither delay discounting nor CFC was associated with alcohol consumption, which is also consistent with previous work finding no relation between delay discounting and alcohol consumption after controlling for alcohol demand (Lemley et al., 2016). It is possible that the relatively restricted drinking range in our heavy drinking sample may have limited the predictive utility of both measures, and the results may have been different in a sample that included lighter drinkers.

Greater proportionate substance-related reinforcement, greater alcohol demand, and lower CFC were all associated with greater alcohol-related problems. This is consistent with behavioral theories of choice and suggests that individuals receiving a high proportion of reinforcement from alcohol use may drink alcohol more often, have higher expectations for its effects, and engage in more dangerous activities under the influence of substances than those who derive more enjoyment from substance-free activities. The alcohol demand finding is also consistent with previous work elucidating this finding among heavy drinking young adults (Bertholet et al., 2015; Lemley et al., 2016; Murphy et al., 2009; Teeters et al., 2014). Finally, consistent with previous research, our results suggest that those who consider future outcomes in making current decisions about behavior are less likely to misuse substances and experience subsequent problems (Amlung et al., 2017; Mackillop et al., 2010; MacKillop and Tidey, 2011; Soltis et al., 2017). Those with lower future oriented thinking tend to only consider how their current behavior will influence them right now rather than in the future. Thus, these individuals are more likely to seek out immediate rewards (e.g., alcohol) rather than defer for prolonged, future rewards (e.g., studying, going to class, seeking internship opportunities) that are often unengaging and hold little current value but that increase opportunities for reward in the future.

Counter to previous research, greater discounting of delayed rewards was associated with lower alcohol consumption (nonsignificant trend level) and alcohol-related problems. The relation between delay discounting and substance use is inconsistent in the literature among young adult samples (Dennhardt and Murphy, 2011; Lemley et al., 2016; Teeters and Murphy, 2015), despite robust evidence linking delay discounting to alcohol misuse in general, or more specifically, among severe populations (Amlung and MacKillop, 2011; MacKillop et al., 2011). It is unclear why we observed this counterintuitive finding. It is possible that heavy drinkers who are low discounters are more aware of problems or are more likely to interpret their heavy drinking, which may be largely contextually driven, in a problematic way. Further, this model accounted for many other variables, including CFC, which have not been previously included in a comprehensive model. Other factors may also influence delay discounting in this population (e.g., little financial decision making experience). The finding that CFC is related to alcohol-related problems supports the relevance of future valuation to alcohol misuse; however, our results with delay discounting, in conjunction with other inconsistent findings, cast doubt on the utility of delay discounting as a measure of this construct among heavy drinking college students, and CFC may be a more useful measure in this population.

Reinforcer pathology also suggests a strong influence of future oriented thinking on both demand and engagement with substance-free activities (Bickel et al., 2011). Our model partially supports the reinforcer pathology hypothesis, as proportionate substance-related reinforcement was associated with CFC, but alcohol demand was not. Further, delay discounting was associated with alcohol demand in the expected direction. The connection between future orientation and proportionate substance-related reinforcement is obvious, considering that college students with diminished future orientation are more likely to engage with stimuli that elicit immediate rather than delayed rewards. Thus, these individuals would likely engage in substance-related activities more often and consider them more rewarding. Although we hypothesized that greater CFC would lead to greater substance-related reinforcement, the associations are likely bidirectional. Consistent engagement with substance-related reinforcement might diminish future oriented thinking, possibly due to an increased attentional bias towards alcohol stimuli (Fadardi and Cox, 2008), increasing alcohol seeking behavior, such that people think more about how their behavior is influencing immediate rather than future outcomes. Alternatively, it may be that those with greater proportionate reinforcement may have had fewer financial resources and/or less substance-free reinforcement throughout development (Andrabi et al., 2017), which could diminish one’s interest in or pursuit of future oriented reward.

We also examined indirect effects of pathways from behavioral economic variables to alcohol consumption and -related problems. Interestingly, CFC had an indirect effect on alcohol consumption through proportionate substance-related reinforcement and alcohol demand. It is possible that those with diminished consideration of future outcomes elect to engage in activities with more immediate rewards, such as substance-related activities. This is associated with an increase in alcohol demand, which is in turn followed by increases in alcohol consumption. This case is perhaps more compelling due to the nonsignificant direct effects of CFC on alcohol demand, suggesting that diminished alternative reinforcement is a critical factor in the path towards increased alcohol consumption. There was also an indirect effect of proportionate substance-related reinforcement through alcohol demand on alcohol-related problems. The relation between diminished engagement in alternative activities and problematic alcohol use is robust (Andrabi et al., 2017; Correia et al., 2003; Murphy et al., 2007); however, mechanisms responsible for the relation have gone unexplored. Behavioral theories of choice suggest that, among heavy drinkers, decreases in reinforcement from alternatives may be coupled with an increase in valuation for alcohol that leads to problematic use. Although the directionality is ambiguous in this cross-sectional sample, the findings are consistent with theory (Murphy et al., 2007) and support longitudinal inquiry into the indirect relations between behavioral economic variables.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

The current study had several strengths. First, this is the first study to use a robust statistical technique that accounted for all variables in the behavioral economic model simultaneously. Second, our study examined indirect relations between behavioral economic predictors and problematic alcohol use. Third, previous univariate studies establishing demand, time orientation, and proportionate substance-related reinforcement as predictors of alcohol misuse did not account for their covariance, and, therefore, this is the first study to establish their independent and incremental relevance to alcohol misuse. Fourth, we modeled demand as a latent construct to reduce measurement error. Fifth, we used a large, relatively diverse sample (N=393) of high-risk emerging adult drinkers (M = 17 drinks per week) recruited from two separate universities with reliable and valid behavioral economic and alcohol misuse measures and little missing data.

Several limitations are also noted. First, the data were cross-sectional and, therefore, causal directionality of the modeled relations cannot be established. A complex longitudinal mixture model with a large sample size could demonstrate how each variable in the model evolves over time. Second, some variables were modeled as continuous despite actually being count. We did, however, initially model these variables as count, and convergence issues forced us to model them as continuous. Third, although alcohol demand was modeled as a latent variable, alternative reinforcement, time orientation, and problematic substance use were modeled as observed. Examining these constructs as latent with multiple measures and methods could increase the generalizability of these findings by decreasing measurement error. Fourth, there is evidence that, despite general stability, demand and delay discounting may be dynamic and state-dependent (MacKillop et al., 2010; Snider et al., 2016), and the current study did not capture within-person variation in these constructs. Further, the delay discounting measure restricted the larger, later reward to $100, an amount that may be too small to ideally capture variability in this construct (e.g., vs. larger delayed amounts of $1,000; Koffarnus and Bickel, 2014). This study should be replicated with other measures of delay discounting to identify a whether our null and counter intuitive results with this variable was an artifact of the measure itself or a reflection of true phenomena. Finally, our model did not include other relevant predictors, such as genetic predisposition, psychiatric comorbidity, or predictors from other theoretical perspectives, such as drinking motives. Despite these limitations, our study supports behavioral economic theory and the inclusion of alternative reinforcement into future models examining reinforcer pathology.

Implications

The primary implication of the current study is the support of behavioral economic theory as a model for understanding college student alcohol misuse. Overall, the relations that have been found in separate regression analyses do not interact to predict risk, but remain significant when controlling for other behavioral economic variables, suggesting that these constructs are unique, and that each construct contributes uniquely to the problem of alcohol misuse among college students. Behavioral economic theory posits that increasing alcohol use may also further influence behavioral economic variables, and a longitudinal study examining these relations should be a priority. It is important to note that our findings only accounted for approximately 22% and 41% of variance in alcohol-related problems and consumption, respectively. Other psychological theories, in addition to those already in use within the field of addiction, may provide insight into the factors responsible for unaccounted variance. This could be accomplished with a dynamic systems approach, which emphasizes interactions between various levels of organization (e.g., micro, meso, and macro) as an explanation for complex behavioral phenomena (Hollenstein, 2013), which may additionally explain the etiology and maintenance of problematic alcohol use and may also lead to synthetization of theoretical approaches.

Our study also supports previous research suggesting that behavioral economic concepts might be useful in enhancing already promising brief interventions for college student heavy drinkers. The Substance-free activity session (SFAS) is a single session BMI supplement intended to increase engagement in substance-free activities, future thinking, and to decrease substance demand (Murphy et al., 2012). Recent work also suggests that delay discounting and demand can be manipulated through episodic future thinking (Snider et al., 2016), which attempts to increase the salience of future rewards through vivid imagining of a positive future event. Although both intervention strategies are relatively novel and need more empirical research, both show promise and may reasonably be included with already widely disseminated interventions to increase efficacy.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

The final model with standardized estimates. D = Variance unaccounted for by model. *** p< .001, ** p< .01, *p< .05.

Table 3.

Model results for the Alternative Behavioral Economic Model

| Model Results | Unstandardized Estimate (S.E.) | Standardized Estimates (S.E.) |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Demand by | ||

| Elasticity | −.07 (.01)*** | −.28 (.05)*** |

| Intensity | .95 (.16)*** | .96 (.06)*** |

| Omax | − | .45 (.06)*** |

| Alcohol Problems on | ||

| Alcohol Demand | .28 (.12)* | .15 (.07)* |

| k | −.13 (.06) | −.090 (.05)* |

| CFC | −.17 (.06)** | −.14 (.05)** |

| Alcohol Consumption | .13 (.04)** | .20 (.06)** |

| rratio | 1.16 (.27)*** | .22 (.05)*** |

| Alcohol Consumption on | ||

| r-ratio | 1.30 (.37)*** | .16 (.05)*** |

| Alcohol Demand | 1.64 (.28)*** | .59 (.07)*** |

| k | −.13 (.08) | −.06 (.04) |

| CFC | .04 (.07) | .02 (.04) |

| rratio on | ||

| k | .01 (.01) | .02 (.04) |

| CFC | −.03 (.01)* | −.13 (.05)** |

| Alcohol demand on | ||

| r-ratio | .65 (.18)*** | .22 (.05)*** |

| k | .09 (.05) | .14 (.08) |

| CFC | −.05 (.04) | −.08 (.06) |

| Elasticity with | ||

| Omax | −.05(.01)*** | −.62 (.04)*** |

| k with | ||

| CFC | −.05 (.02)* | −.12 (.05)* |

|

| ||

| R2 values (S.E.) | ||

|

| ||

| Alcohol Demand | .08 (.04)* | |

| Elasticity | .08 (.03)** | |

| Intensity | .93 (.11)*** | |

| Omax | .20 (.05)*** | |

| Alcohol consumption | .41 (.08)*** | |

| r-ratio | .02 (.02) | |

| Alcohol Problems | .22 (.04)*** | |

Note. CFC=Consideration of Future Consequences; r-ratio=Substance-related reinforcement; k = Delay discounting; S.E. = Standard error.

p< .001,

p< .01,

p< .05.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grant R01 AA020829 (PI: James G. Murphy). The funding source had no role other than financial support.

Footnotes

In one set of analyses, we modeled alcohol consumption and related problems as count variables. These models would not estimate, even after changing the starting values. For this reason, and because these variables are commonly modeled as continuous variables in the literature, they were modeled as continuous in the main analyses.

We tested individual models that included delay discounting or CFC separately. All results remained the same.

We tested models that included gender and race (White and Non-White minority) as covariates. Although gender was a significant predictor of both alcohol consumption and problems, the findings already reported were not influenced, and for this reason gender and race were left out of the final model.

We analyzed the model using elasticity calculated with the exponential demand equation (Hursh & Silberberg, 2008). Model fit indices were nearly identical (χ2 =12.88, df = 9, p-value = .17; RMSEA = .03, CI: .00, .07; CFI = .99; SRMR = .03; AIC = 3480.34; BIC = 3619.42), and the results remained the same.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism or the National Institutes of Health.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Acuff SF, Murphy JG. Further examination of the temporal stability of alcohol demand. Behav Processes. 2017:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2017.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acuff SF, Soltis KE, Dennhardt AA, Borsari B, Martens MP, Murphy JG. Future So Bright? Delay discounting and consideration of future consequences predict academic performance among college drinkers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017 doi: 10.1037/pha0000143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlung MT, Acker J, Stojek MK, Murphy JG, Mackillop J. Is Talk “Cheap”? An Initial Investigation of the Equivalence of Alcohol Purchase Task Performance for Hypothetical and Actual Rewards. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:716–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlung MT, MacKillop J. Delayed Reward Discounting and Alcohol Misuse: The Roles of Response Consistency and Reward Magnitude. J Exp Psychopathol. 2011;2:418–431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlung MT, Vedelago L, Acker J, Balodis I, Mackillop J. Steep delay discounting and addictive behavior: A meta-analysis of continuous associations. Addiction. 2017;112:51–62. doi: 10.1111/add.13535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrabi N, Leventhal A, Khoddam R. Diminished alternative reinforcement mediates socioeconomic disparities in adolescent substance ase: A longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017:171. [Google Scholar]

- Aston ER, Metrik J, Amlung MT, Kahler CW, MacKillop J. Interrelationships between marijuana demand and discounting of delayed rewards: Convergence in behavioral economic methods. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;169:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertholet N, Murphy JG, Daeppen JB, Gmel G, Gaume J. The alcohol purchase task in young men from the general population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;146:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Gatchalian KM. The Behavioral Economics and Neuroeconomics of Reinforcer Pathologies: Implications for Etiology and Treatment of Addiction. Curr Psychiatr Reports. 2011;13:406–415. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0215-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Johnson MW, Koffarnus MN, MacKillop J, Murphy JG. The behavioral economics of substance use disorders: Reinforcement pathologies and their repair. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:641–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia CJ, Carey KB, Simons J, Borsari BE. Relationships between binge drinking and substance-free reinforcement in a sample of college students: A preliminary investigation. Addict Behav. 2003;28:361–368. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00229-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty JR, Brase GL. Taking time to be healthy: Predicting health behaviors with delay discounting and time perspective. Pers Individ Dif. 2010;48:202–207. [Google Scholar]

- Dennhardt AA, Murphy JG. Associations between depression, distress tolerance, delay discounting, and alcohol-related problems in European American and African American college students. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25:595–604. doi: 10.1037/a0025807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadardi JS, Cox WM. Alcohol-attentional bias and motivational structure as independent predictors of social drinkers’ alcohol consumption. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;97:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D. The social epidemiology of substance use. Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:36–52. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herting MM, Schwartz D, Mitchell SH, Nagel BJ. Abnormalities in Youth With a Family History of Alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1590–1602. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH, Lussier JP. Clinical implications of reinforcement as a determinant of substance use disorders. Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:431–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Smyth D. Magnitude and Trends in Heavy Episodic Drinking, Alcohol-Impaired Driving, and Alcohol-Related Mortality and Overdose Hospitalizations Among Emerging Adults of College Ages 18 – 24 in the United States, 1998 – 2014. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2017;78:540–548. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009:12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein T. State space grids: Depicting dynamics across development. 1. Springer; US: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model A Multidiscip J. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR, Silberberg A. Economic demand and essential value. Psychol Rev. 2008;115:186–98. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Bickel WK. Analgorithm for identifying nonsystematic delay-discounting data. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;16:264–274. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM. Heroin and cocaine abusers have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than alcoholics or non-drug-using controls. Addiction. 2004;99:461–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 4. New York: The Guilford Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Bickel WK. A 5-trial adjusted delay discounting task: Accurate discount rates in less than 60 seconds. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;22:222–228. doi: 10.1037/a0035973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Franck CT, Stein J, Bickel WK. A modified exponential behavioral economic demand model to better describe consumption data. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;23:504–512. doi: 10.1037/pha0000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemley SM, Kaplan BA, Reed DD, Darden AC, Jarmolowicz DP. Reinforcer pathologies: Predicting alcohol related problems in college drinking men and women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;167:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackillop J. The behavioral economics and neuroeconomics of Alcohol Use Disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40:672–685. doi: 10.1111/acer.13004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Amlung MT, Few LR, Ray LA, Sweet LH, Munafò MR. Delayed reward discounting and addictive behavior: A meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;216:305–321. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2229-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackillop J, Miranda R, Jr, Monti PM, Ray LA, Murphy JG, McGeary JE, Swift RM, Tidey JW, Gwaltney CJ. Alcohol Demand, Delayed Reward Discounting, and Craving in relation to Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2010;119:106–114. doi: 10.1037/a0017513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Murphy JG, Tidey JW, Kahler CW, Ray LA, Bickel WK. Latent structure of facets of alcohol reinforcement from a behavioral economic demand curve. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;203:33–40. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1367-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, O’Hagen S, Lisman SA, Murphy JG, Ray LA, Tidey JW, McGeary JE, Monti PM. Behavioral economic analysis of cue-elicited craving for alcohol. Addiction. 2010;105:1599–1607. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Tidey JW. Cigarette demand and delayed reward discounting in nicotine-dependent individuals with schizophrenia and controls: An initial study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;216:91–99. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2185-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur JE, Herrnstein RJ. On the functions relating delay, reinforcer value, and behavior. Behav Brain Sci. 1988;11:690–691. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Correia CJ, Barnett NP. Behavioral economic approaches to reduce college student drinking. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2573–2585. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Correia CJ, Colby SM, Vuchinich RE. Using behavioral theories of choice to predict drinking outcomes following a brief intervention. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;13:93–101. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.13.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA. The behavioral economics of young adult substance abuse. Prev Med (Baltim) 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Borsari BE, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Martens MP. A randomized controlled trial of a behavioral economic supplement to brief motivational interventions for college drinking. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:876–886. doi: 10.1037/a0028763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J. Relative reinforcing efficacy of alcohol among college student drinkers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;14:219–27. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J, Skidmore JR, Pederson AA. Reliability and validity of a demand curve measure of alcohol reinforcement. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;17:396–404. doi: 10.1037/a0017684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Olson EA, Hooper CJ, Collins P, Luciana M. Adolescents’ performance on delay and probability discounting tasks: Contributions of age, intelligence, executive functioning, and self-reported externalizing behavior. Pers Individ Dif. 2007;43:1886–1897. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR. Development and preliminary validation of the young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67:169–177. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Lawyer SR, Swift JK. A meta-analysis of nonsystematic responding in delay and probability reward discounting. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;26:94–107. doi: 10.1037/pha0000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider SE, LaConte SM, Bickel WK. Episodic Future Thinking: Expansion of the temporal window in individuals with alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40:1558–1566. doi: 10.1111/acer.13112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis KE, McDevitt-Murphy ME, Murphy JG. Alcohol Demand, Future Orientation, and Craving Mediate the Relation Between Depressive and Stress Symptoms and Alcohol Problems. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41:1191–1200. doi: 10.1111/acer.13395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathman A, Gleicher F, Boninger DS, Edwards CS. The consideration of future consequences: Weighing immediate and distant outcomes of behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;66:742–752. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 6. 2013. Using Multivariate Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Teeters JB, Murphy JG. The behavioral economics of driving after drinking among college drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:896–904. doi: 10.1111/acer.12695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeters JB, Pickover AM, Dennhardt AA, Martens MP, Murphy JG. Elevated alcohol demand is associated with driving after drinking among college student binge drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014:38. doi: 10.1111/acer.12448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teuscher U, Mitchell SH. Relation between time perspective and delay discounting: A literature review. Psychol Rec. 2011;61:613–632. [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich RE, Simpson CA. Hyperbolic temporal discounting in social drinkers and problem drinkers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;6:292–305. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.6.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AM, Hingson RW. The burden of alcohol use: Excessive alcohol consumption and related consequences among college students. Alcohol Res Curr Rev. 2013;35:201–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan KH, Bentler PM. Structural Equation Modeling with Robust Covariances. Sociol Methodol. 1998;28:363–396. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.