Abstract

Little is known about the psychosocial profiles of parents who have a child with an undiagnosed chronic illness. The National Institutes of Health Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN) evaluates individuals with intractable medical findings, with the objective of discovering the underlying diagnosis. We report on the psychosocial profiles of 50 parents whose children were accepted to one of the network s clinical sites. Parents completed questionnaires assessing anxiety, depression, coping self-efficacy and health care empowerment at the beginning of their child s UDN clinical evaluation. Parents of undiagnosed children had high rates of anxiety and depression (~40%), which were significantly inversely correlated with coping self-efficacy, but not with health care empowerment. Coping self-efficacy, depressive and anxiety symptoms were better in parents with older children and with longer duration of illness. Gender differences were identified, with mothers reporting greater healthcare engagement than fathers. Overall, our findings suggest that parents of children with undiagnosed diseases maintain positive coping self-efficacy, remain actively engaged in healthcare and to a lesser degree tolerance for uncertainty, but these come with a high emotional cost to the parents. As the parents psychological needs may not be obvious; these should be ascertained, and the requisite support provided.

Keywords: Undiagnosed disease, parent, depression, anxiety, coping self-efficacy, health care empowerment, tolerance of uncertainty, whole exome sequencing, diagnostic odyssey

Introduction

Approximately 30 million Americans live with undiagnosed diseases, which are associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality (Angelis, Tordrup, & Kanavos, 2015; Christianson, 2006; Eurordis, 2005). Undiagnosed diseases often present in early in life, with ~50% of undiagnosed individuals being children (https://globalgenes.org, 2015). The majority (~80%) of undiagnosed diseases are believed to have an underlying genetic basis (Chong et al., 2015). Therefore, children with undiagnosed diseases often undergo numerous evaluations and extensive genetic testing in an effort to obtain a diagnosis, leading to what has been termed a ‘diagnostic odyssey’ (Rosenthal, Biesecker, & Biesecker, 2001). This diagnostic odyssey can be a significant source of parental stress and uncertainty, the psychosocial effects of which remain poorly characterized.

The Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN), funded by the National Institutes of Health, is a nationwide network-based research study established in 2013, bringing together clinical and research experts from across the United States to solve the most challenging medical mysteries. The UDN employs deep phenotyping, pertinent clinical and laboratory testing, whole exome sequencing (WES) and advanced technologies such as whole genome sequencing (WGS), metabolomics and animal modeling in its diagnostic efforts (https://undiagnosed.hms.harvard.edu). Seven academic medical centers comprise the UDN clinical sites and receive applications undiagnosed adult and pediatric patients after extensive examinations and tests have failed to yield a diagnosis from all over the United States with a few international as well.

The parental experience of searching for a diagnosis has been described as a journey, with two distinct components: an inner emotional experience that includes the realization there is a problem, wanting a diagnosis and coping with it and the outer sociological experience which includes experiences with professionals and support networks (Lewis, Skirton, & Jones, 2010). Understandably, the focus of this diagnostic odyssey is the child’s health, with the parents worrying about worsening of symptoms and delays in treatment or inappropriate treatment, which can result in stress and frustration (Carmichael, Tsipis, Windmueller, Mandel, & Estrella, 2015; Rosenthal et al., 2001; Spillmann et al., 2017; Yanes, Humphreys, McInerney-Leo, & Biesecker, 2016; Zurynski et al., 2017). Only a few studies have aimed to study the emotional impact of this journey on the parents of a child with an undiagnosed disease. Madeo et. al. (2012) reported that the uncertainty of not having a diagnosis was related to less personal control and reduced optimism. In a comparative study of parents of children with undiagnosed genetic conditions and mothers of children with dystrophinopathies, the former had significantly less hope, perceived social support and coping self-efficacy, suggestive of worse adaptation in the undiagnosed group (Peay et al., 2016; Yanes et al., 2016). Similarly, Lingen et al. (2016) found that maternal quality of life scores were lower in children with an unconfirmed chromosome abnormality when compared to mothers whose children were diagnosed with a specific chromosome microdeletion or duplication We recently reported elements of chaos in illness narratives written by parents of children with undiagnosed disorders in the UDN (Spillmann et al., 2017). Chaos narratives are characterized by uncertainty, fear, suffering, inability to consider a future, to make plans, and loss of control, self, or purpose (Bally et al., 2014; Frank, 1995; Nettleton, Watt, O'Malley, & Duffey, 2005; Whitehead, 2006). Taken together, these reports indicate that there are high rates of emotional distress in parents of children with undiagnosed diseases. However, no study has assessed parental depression and anxiety in these parents.

Since the literature on the psychosocial impact of parenting a child with an undiagnosed disease is limited, the literature on parents of children with diagnosed disorders that result in chronic health problems can provide some additional insights. Parents of children diagnosed with rare genetic disorders also report feelings of social isolation, anxiety, fear, anger, uncertainty (Pelentsov, Laws, & Esterman, 2015), and high parental physical and emotional strain (Dellve, 2006). One third to half of parents of children with chronic health disorders (Besier et al., 2011; Driscoll, Montag-Leifling, Acton, & Modi, 2009; Guillamon et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2010; Peay et al., 2016) had symptoms of anxiety and depression, which were significantly higher than the general population (Besier et al., 2011) suggesting that the increase in depression and anxiety is related to having a child with a chronic health condition. The extent to which depression and anxiety is further increased by the additional element of parenting a child with an undiagnosed chronic health condition is unknown.

For parents of children with undiagnosed disorders, we propose that sociodemographic variables such as the child’s age, gender of the parent, and previous experiences with diagnostic testing including the length of time in search of a diagnosis may influence the parental psychosocial state. One such variable may be a prior non-diagnostic WES result. The majority of undiagnosed children will have a non-diagnostic WES (Need et al., 2012) and their parents are representative of those who have reached the ‘end of the road’ with all available diagnostic options and potentially have worse emotional distress than those without a prior WES. Few publications have specifically examined the impact of a non-diagnostic WES on the psychosocial well-being of parents. Skinner et al. (2016) reported that when parents had a non-diagnostic WES in their child, felt they had done all they could, and instead of continuing to pursue a diagnosis, they would wait for science to advance. However, in our study of parental perceptions of the WES process, we found that for some parents a non-diagnostic WES led to concerns about what direction to take next, ongoing frustration and disappointment, while for others the continued diagnostic odyssey was infused with resiliency and the hope that a better future would be possible (McConkie-Rosell et al., 2016). Both of these studies were qualitative and did not measure parental psychosocial profiles, which may be affected by a non-diagnostic WES. Similarly, there is limited research on maternal versus paternal emotional distress related to having a child with a chronic illness (Cohen, 1999; Pelchat, Levert, & Bourgeois-Guérin, 2009; Perry, Sarlo-McGarvey, & Factor, 1992). Mothers of children with diagnosed life limiting illnesses have been found to have higher rates of depressive symptoms, caregiving burden with less optimism than fathers (Schneider, Steele, Cadell, & Hemsworth, 2011) and mothers of children with undiagnosed multiple anomalies and/or developmental delay have lower quality of life scores than fathers (Lingen et al., 2016). However, mothers have also been found to utilize greater emotional and social support coping strategies (Salas, Rodríguez, Urbieta, & Cuadrado, 2017) and experience greater positive growth than fathers (Schneider et al., 2011). Such gender differences have not been comprehensively measured in parents of undiagnosed children.

The UDN offers a unique opportunity to examine the psychological characteristics of parents of children with undiagnosed diseases who are in the process of undergoing extensive clinical and laboratory evaluations, including WES and/or WGS with the goal of diagnosis. The parents’ psychosocial state is important to consider as it can have a direct effect on the parental ability to actively engage in the diagnostic process and can have long-term consequences for the child and family (Driscoll et al., 2009; Guillamon et al., 2013; Muscara, Burke, et al., 2015). These parental psychological profiles are needed to identify interventions to improve outcomes for children and their families and are especially relevant for the medical geneticist and genetic counselors who partner with parents in the search of a diagnosis.

Our primary objectives are: 1) to assess parental psychosocial profiles, by describing the parental inner emotional state associated with having an undiagnosed child and their perceived abilities related to coping self-efficacy and health care empowerment, 2) to determine if sociodemographic variables and prior non-diagnostic WES are associated with the parental psychosocial profiles. We provide for the first time, data on depressive and anxiety symptoms in parents of undiagnosed children. Our hypotheses are that there are high rates of anxiety and depression symptoms in parents of undiagnosed children and that these are associated with lower coping self-efficacy and lower health care empowerment. We also posit that the duration of illness, gender of the parents and prior non-diagnostic WES would result in differences in the parental inner emotional state and their perception of abilities to cope and act on their child’s behalf.

Materials and Methods

Sample

All data for the study were collected prospectively at the Duke UDN clinical site. The study was reviewed by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB) and approved by the central IRB at the National Institute of Health (NIH) (15-HG-0130). At the time of acceptance to the Duke UDN site, parents of children (minor child or adult child incapable of giving consent) were informed about this optional substudy and those who agreed to participate were consented during the child’s evaluation. Parents unable to complete the study measures in English were excluded. The study measures were completed on the first day of the UDN evaluation. If both parents were willing to participate, but only one parent attended the evaluation, the absent parent was sent a copy of the measures to complete, with the exception of the depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) measures. These two measures were completed only in person so that if a risk for significant self-harm or scores suggesting clinical depression or anxiety was uncovered appropriate follow up and evaluation could be arranged by the attending physician. Parents were also able to opt out of completing an individual measure.

Measures

Parental Inner Emotional State

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

This is a nine-item inventory for screening, diagnosing monitoring and measuring the severity of depression. The PHQ-9 incorporates DSM-V (www.dsm5.org) depressive diagnostic criteria and has excellent internal reliability (Cronbach alpha=0.89) (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001). The item scores are 0 to 3 (0 = “Not at all” to 3 = “Nearly every day”). Item 9 screens for the presence and duration of suicidal ideation. Higher scores on the nine items indicate higher levels of depressive symptoms. PHQ scores ≥10 have a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 88% for a clinical diagnosis of major depression. Scores of 5, 10, and 20 represent mild, moderate and severe depression.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7)

Anxiety was assessed using the GAD-7 scale, a seven-item inventory for screening, diagnosing, monitoring and measuring the severity of generalized anxiety disorder. The GAD- 7 has good reliability (Cronbach's alpha= .79–.91) (Dear et al., 2011). The scale was developed and validated based on DSM-IV criteria, but it remains clinically useful after publication of the DSM-V (www.dsm5.org). Response options range from 0 – 3 (“not at all”, “several days”, “more than half the days”, and “nearly every day”). Higher scores indicate higher levels of anxiety symptoms. Scores of ≥10 are indicative of a generalized anxiety disorder. Scores of 5, 10, and 15 are suggestive of mild, moderate, and severe anxiety disorder respectively (Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Lowe, 2006).

Perceived Abilities to take an action-Coping

Coping Self-Efficacy Scale (CSE)

This is a 26-item measure of one’s confidence in performing coping behaviors when faced with life challenges and is based on the theory of self-efficacy, a way of being able to control one’s behavior (Chesney, Neilands, Chambers, Taylor, & Folkman, 2006). It assesses three factors: problem-focused coping, stopping unpleasant emotions and thoughts, and receiving support from friends and family and was developed initially with patients with HIV infection (Bandura, 1997). The CSE has been found to be a reliable measure (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79–0.92) and can assess longitudinal changes in coping self-efficacy (Chesney et al., 2006). Response options range from 0–10 scale (“cannot do at all” to “certain can do”). A CSE total score was computed for each participant. The subscales were not computed as they have not been previously reported individually in the literature.

Outer Sociological Experience: Perceived Abilities to take an action-Health Care

Health Care Empowerment Inventory (HCEI)

This is an 8-item inventory composed of two subscales assessing actions one can take regarding health care and tolerance of uncertainties in treatment outcomes, using a 5-point Likert scale (“Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”) (Johnson, 2011). Higher scores indicate higher levels of health care empowerment. Reliability of the HCEI is high (Cronbach’s alpha= 0.82) (Johnson, Rose, Dilworth, & Neilands, 2012). For this study, “my child” was added to the items, wherever it referred to the patient, to make the questions pertinent to the parent respondents. For example, “I prefer to get as much information as possible about treatment options” was revised to “I prefer to get as much information as possible about my child’s treatment options”. The informed, committed, collaborative, and engaged score (ICCE) was computed for each participant by summing the responses to the four items that measure actions one can take regarding health care engagement. The tolerance for uncertainty (TU) score was computed by summing the responses to the four items that measure emotional coping, defined as being tolerant or resilient to uncertainties in treatment outcomes. The HCEI was originally developed for patients with a known disorder (HIV infection) that had treatment options and it was found to be predictive of an improved health outcome with greater adherence to medical management. (Johnson, 2011; van den Berg, Neilands, Johnson, Chen, & Saberi, 2016). For the purpose of this study, the term “health care engagement” will be used to describe ICCE; tolerance of uncertainly (TU) will be used as is.

Data Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) version 24.0. The measures were scored according to the instructions. Measures that were incomplete were not utilized in the analyses for that parent. Descriptive analyses, Fisher’s exact test, chi-square and student’s t-test were used to describe the demographics, overall results on the measures and the gender differences in the measures. Z-scores were calculated for all measures based on data published in the literature: for PHQ-9 and GAD-7, these were derived from the mean ± SD from the general population (Hinz et al., 2017; Kocalevent, Hinz, & Brahler, 2013). For the CSE and the HCEI, published norms based on HIV positive patients were used (Chesney et al., 2006; Crouch, Rose, Johnson, & Janson, 2015), since these questionnaires were developed using this patient population.

Bivariate correlations were performed to examine the relation between the GAD-7, PHQ-9, age of the child, duration of illness, CSE and HCEI. Key variables with significant correlations were then entered into a multiple linear regression model, with the dependent variables of CSE and HCEI.

There were 31 affected children whose parents participated in the study and in 19 of these, both parents of the same children participated. Since we had both the mother and the father of the same child respond in some instances, we performed a mixed effects linear model to examine the effects of gender differences on the measures, with the entire cohort of 50 parents as well as with only one parent responder (who was randomly selected for the 19 duplicate responses), for each of the 31 probands. The results were not substantively different except for the HCEI health care engagement subscale, which was significantly higher in mothers when all 50 parents were included and so we present data on the 31 parents as well for this. For all other measures, we present data on all 50 parents. With no studies thus far on gender differences in parents of undiagnosed children, it was important to include the entire cohort. Additionally, the objective of the study was to study parental emotional distress, so the parsimonious approach of randomly selecting one parent only for each child would lead to us not being able to capture the extent of the psychological distress in these parents. Lastly, the children accepted to the UDN are generally severely affected with little heterogeneity in their medical manifestations and hence the demands placed on the parents and the parental experiences would be similar across these.

Results

Demographics

A total of 65 parents of 39 affected children (probands) were offered the study and 16 (9 mothers and 7 fathers) declined to participate, resulting in 31 probands whose parents participated. The demographics of the cohort of 50 parents who participated are in Table I. The racial distribution in this cohort is similar to the overall distribution in the UDN.

Table I.

Details of the demographics of the sample (n=50)

| Variable | Statistics |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Number of probands | 31 |

|

| |

| Gender of all 50 Parents | Female=30 Male=20 |

|

| |

| Ages of the 50 Parents (in years) | |

| Males | 25–39= 9, 40–54= 11 |

| Females | 25–39= 17,

40–54= 13 Fisher’s exact test p>0.05 |

|

| |

| Race/ethnicity of the 50 parents (self-reported) | Caucasian= 86%

Black= 2% Asian= 8% Other= 4% Hispanic/Latino= 10% |

|

| |

| Age of the 31 children (mean±SD and minimum-maximum in years) |

7.83±4.96 (1–18) |

|

| |

| Duration of the 31 children’s

illness (mean±SD and minimum-maximum in years) |

5.89±4.64 (1–18) |

|

| |

| Previous non-diagnostic WES in the 31 children | 15/31, 48% |

| Self-identified primary parent contact for the UDN | Mother (34/50, 68%) Father (4/50, 8%) Both parents (12/50 24%) |

Psychological Measures

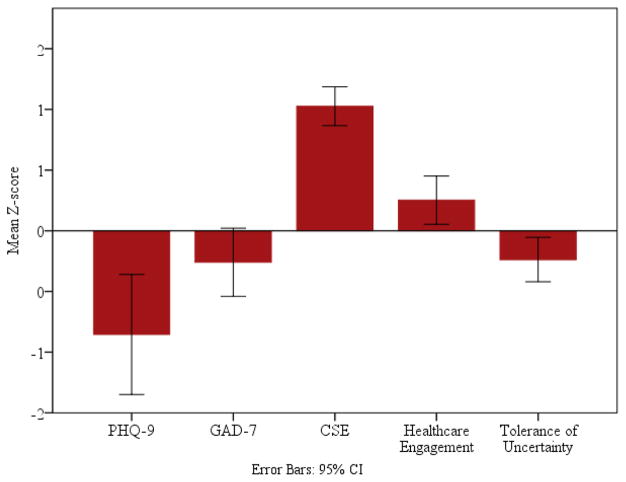

Since the norms that the Z-scores were based on differed amongst the measures, varying from the general population (Dear et al., 2011; Kroenke et al., 2001) to individuals with a specific disorder (HIV infection) (Chesney et al., 2006; Crouch et al., 2015) we present both the total scores (Table II) and the Z-scores (Figure 1) for these.

Table II.

Mean and standard deviations of all Measures of Parental Inner Emotional State and Perceived Abilities to Take an Action (Coping and Health Care Empowerment)

| Measure | Mean±SD | * Norms Mean |

Min- Max |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAD-7 (n=44) | 4.85±4.28 | 3.57±3.38 | 0–20 |

| PHQ-9 (n=44) | 4.8±4.76 | 2.91±3.52 | 0–19 |

| CSE (Total)( n=49) | 186.35±44.16 | 137.4±45.6 | 8–260 |

| HCEI Subscales ICCE-Healthcare engagement (n=47) |

17.96±2.15 | 15.93±2.6 | 12–20 |

| TU-Tolerance of uncertainty (n=47) | 16.25±2.41 | 17.35±2.33 | 11–20 |

Published norms, means ±SD (Chesney et al., 2006; Crouch et al., 2015; Hinz et al., 2017; Kocalevent et al., 2013)

Figure I.

Z-scores of anxiety and depression symptoms (n=44), coping self-efficacy (n-49), health care engagement and tolerance of uncertainty (n=47) in the parents. The negative Z-scores on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 indicate higher scores on the depression and anxiety measures

Parental Inner Emotional State

Anxiety and Depression

Of the 44 parents who completed the GAD-7 and PHQ-9, 29 (65.9%) did not meet criteria for depressive disorder, 8 (18.2%) had mild depression and 7 (15.9%) moderate depression. Twenty-six parents (59.1%) did not meet criteria for anxiety, 11 (25%) had mild anxiety, 6 (13.7%) moderate and 1 (2.3%) severe anxiety (Table II; Figure I).

Abilities to take an action: Coping and Health Care

Coping Self-Efficacy

The CSE scores were high in this cohort, indicative of normal coping skills and as the Z-scores in Figure 1 indicate, they are a relative strength of the parents in our study.

Health Care Empowerment

Overall, both the healthcare engagement and TU scores were normal, and when compared to each other, the healthcare engagement is higher for the total sample than TU (paired samples t=5.17, p<0.001). Health Care engagement and TU were also significantly correlated (r = .33; p < .05).

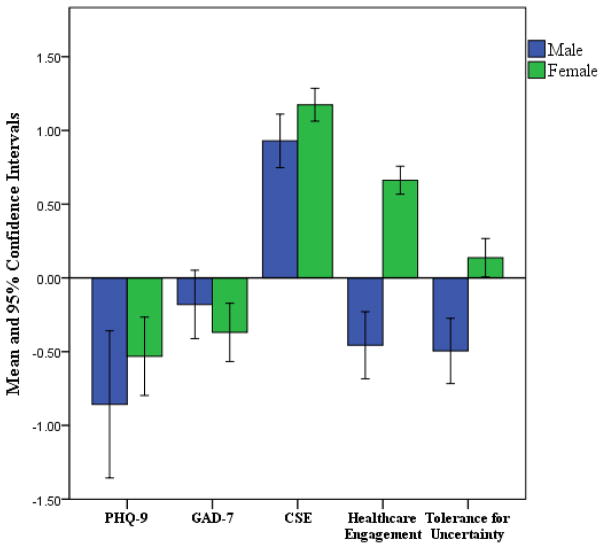

Gender differences

We examined differences between fathers and mothers on all measures to ascertain gender differences in the psychosocial profiles (Figure II and Table III). There were no gender differences in the severity (mild, moderate and severe) of both anxiety (χ2= 1.49, p>0.05) and depression (χ2=3.36, p>0.05). There were also no gender differences in the CSE, but we did see gender differences in the HCEI scores as seen in Table III. For the healthcare engagement subscale, when only one parent for each proband (n=31) was selected, the scores were 16.14 ± 2.79 for males (n=7) and 18.70 ± 1.55 for females (n=23), t= −3.13, p<0.01, with one absent parental response. Thus, gender differences were evident even in this smaller set of parents, despite the differential results on the mixed modeling linear analyses.

Figure II.

Illustrates the gender differences in Z-scores across all five measures, highlighting the higher scores in the mothers for health care engagement and the trend for tolerance for uncertainty being lower in males.

Table III.

Gender differences on scores on all measures

| Measure | Gender | Mean±SD | df | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 | Male=16 | 5.44±5.84 | 42 | t=.45,

0>0.05 Cohen’s d=0.22 |

| Female=28 | 4.25±4.46 | |||

| GAD-7 | Males=16 | 4.38±4.20 | 42 | t=.71,

p>0.05 Cohen’s d= −.11 |

| Females=28 | 4.89±4.71 | |||

| Coping Self Efficacy | Male= 19 | 168.32±67.46 | 47 | t=1.49,

p>0.05 Cohen’s d= −0.46 |

| Female= 30 | 192.87±33.51 | |||

| Healthcare Engagement | Male=17 | 16.24±2.30 | 45 | t= 4.36,

p<0.001 Cohen’s d= −1.4 |

| Female=30 | 18.93±1.43 | |||

| Tolerance of Uncertainty | Male= 17 | 14.88±2.89 | 45 | t= 1.86,

p>0.05 Cohen’s d=−0.58 |

| Female= 30 | 16.4±2.28 |

Cohen’s d effect size: 0.2= small 0.5= medium 0.8=large (Cohen, 1988)

Medium and large effect sizes are in bold

Because of the limited information reported on parental health care empowerment, we reviewed the HCEI item by item. This analysis revealed that mothers had significantly higher scores than fathers on all the four items of the healthcare engagement subscale (1) t= − 4.24 p<.001; (2) t=−2.90 p<.01; (3) t=−4.09 p<.001; (4) t=−3.96 p<.001). Mothers also had significantly higher scores, on two of the TU items (I accept that the future of my child’s health condition is unknown even if I do everything I can” (t= −2.39, p <0.05) and “I recognize that there will likely be setbacks and uncertainty in my child’s health care treatment.” (t = −2.44, p<0.05). The healthcare engagement and TU subscales were also significantly correlated for mothers (r= .49, p <0.01, but not for fathers (r= −.033, p>0.05).

Previous non-diagnostic WES and psychosocial profiles

Overall, there were no differences in anxiety, depression and CSE between parents who had experienced a non-diagnostic WES, compared to those who had not. (Table SI). Healthcare engagement showed a trend towards being higher in parents whose children had been through WES previously (t= 1.9, p=0.06, Cohen’s d effect size= 0.55) (Cohen, 1988).

Correlations between key demographics, parental inner emotional state and perceived ability to take actions

Demographic variables related to the child’s illness were overall not significantly related to the psychosocial measures, except for a positive correlation between the duration of illness and age of the child with CSE (Table IV). Since anxiety and depression were reported in a sizeable proportion of parents, we examined the correlations between these and the CSE and HCEI subscales (Table IV) and found a negative relation between CSE and anxiety as well as depression.

Table IV.

Bivariate correlations between selected demographic variables, anxiety/depression and CSE and HCEI subscales.

| Variable | Age of Child | Duration of Illness | CSE | Healthcare Engagement | Tolerance for Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 | −0.204 | −0.082 | −0.418** | 0.107 | −0.004 |

| GAD-7 | −0.22 | −0.08 | −0.333* | 0.156 | −0.030 |

| CSE | 0.313* | 0.285* | NA | .122 | .261 |

| Healthcare Engagement | −0.178 | −0.207 | NA | NA | NA |

| Tolerance for Uncertainty | −0.167 | 0.017 | NA | NA | NA |

0.1 =small correlation 0.3= medium correlation 0.5= large correlation

Medium and large correlations are in bold

p<0.05

p<0.01

Linear Regression Analyses

In order to delineate the relation between CSE, healthcare engagement and tolerance for uncertainty and key demographic and depression and anxiety measures, linear regression analyses were performed and the results are in Table V.

Table V.

Regression analyses delineating relation between Anxiety, Depression and Demographics with CSE, Healthcare Engagement and Tolerance of Uncertainty

| R2 Change | β | f2 | R2 Change | β | f2 | R2 Change | β | f2 | R2 Change | β | f2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSE | 0.075 | 0.28* | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.30* | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.345* | 0.12 | 0.00 | −0.17 | 0.0 |

| Healthcare Engagement | 0.31 | 0.556*** | 0.45 | 0.06 | −0.26 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.09 | 0.0 |

| Tolerance for Uncertainty | 0.097 | 0.31* | 0.09 | 0.02 | −0.15 | 0.02 | 00 | −0.0 | 0.0 | 0.02 | −0.27 | 0.0 |

Effect size f2 0.02= small 0.15= medium 0.35=large

Medium and large effect sizes are in bold

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Discussion

The psychosocial profiles of parents of undiagnosed children that are being evaluated by the Duke UDN clinical site provide insights into the inner emotional distress associated with the diagnostic odyssey, as well as the commitment of the parents to improving health outcomes for their children. We found that ~35–40% of parents met criteria for mild to moderate depression and mild to moderate anxiety and while this is the first study to report the frequency of these in parents of undiagnosed children, this incidence is similar to that reported in parents of children with diagnosed chronic disorders (Besier et al., 2011; Driscoll et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2010). Given this high frequency of anxiety and depression, it is clear that these parents should be screened for both disorders and treated appropriately (Waszczuk, Zavos, Gregory, & Eley, 2016). Depression and anxiety symptoms may result in parents having difficulty in taking an active caregiving role for their children (Driscoll et al., 2009; Guillamon et al., 2013; Muscara, McCarthy, et al., 2015) and for parents of undiagnosed children, encounters with health care providers may be particularly distressing due to the anxiety and depression. The consistent finding, even with treatment, of increased rates of depression and anxiety in parents of children with chronic disorders (Driscoll et al., 2009), and findings from our study suggest that interventions for parents should include emotion and problem focused coping strategies.

Overall, coping self-efficacy was high in the parents of the UDN and they were found to be engaged in their child’s healthcare and to a lesser degree tolerant of uncertainty. We found that the coping self-efficacy in our cohort was higher than in the one previous study of parents whose children are undiagnosed (Yanes et al., 2016) and so it was interesting to note this dissimilarity. It is possible that the parents in our study, who are are taking the “next steps” on their journey through evaluation in the UDN may feel more self-efficacious due to participation in the network or they may have been more self-efficacious to begin with, given that they applied to the network. Coping self-efficacy has been shown to have a positive longitudinal association with improved psychological adaptation (Peay et al., 2016), better physical and mental health, and lower anxiety (Guillamon et al., 2013). For the parents in our study, we found this same association of better coping self-efficacy with reduced depression and anxiety. It would be interesting to determine the longitudinal trajectory of coping self-efficacy in our cohort.

The HCEI is designed to measure critical factors, which if present, have been demonstrated to improve health outcomes through actions that can be taken for healthcare engagement and tolerance of uncertainty (Johnson, 2011; van den Berg et al., 2016). In our cohort, parents reported similar levels of healthcare engagement and tolerance for uncertainty as adults managing a known diagnosis with an associated treatment (Crouch et al., 2015). Overall healthcare engagement was signficantly higher than tolerance for uncertainity and they were positively correlated. Although the tolerance for uncertainty was lower than health care engagement, it is clear that these parents are more tolerant of uncertainty than what would have been expected based on previous studies (Madeo et al., 2012; McConkie-Rosell et al., 2016; Spillmann et al., 2017; Yanes et al., 2016). Tolerance for uncertainty is an important adaptive coping strategy, and it is thought to be positively related to active engagement in the diagnostic process, investigation of treatment or management options, and commitment to following these through (Johnson et al., 2012). Although we did not formally study this, it is also possible that the participation of the UDN may have given the parents a sense of being more engaged in their children’s healthcare and being more hopeful of finding a diagnosis and this may have influenced the tolerance for uncertainty scores, as hope is an important predictor of parental adaptation to uncertainty (Truitt, Biesecker, Capone, Bailey, & Erby, 2012). Supporting this possibility are the frequent statements that parents make to the Duke UDN team during the evaluation, about the hope that the UDN offers them. Similarly, open-ended statements provided as part of a UDN-wide genetic counseling empowerment study reflected hope that participation in the UDN would lead to an end to the diagnostic odyssey; furthermore, there was appreciation for a program dedicated to individuals with undiagnosed conditions (Palmer, submitted manuscript). Contrary to our hypotheses, we did not see significant correlations between anxiety, depression and the HCEI measures; this may be that healthcare engagement and tolerance for uncertainty are more outward-oriented than coping self-efficacy and the parents may feel the need to focus on these despite their inner emotional state. Parenting children with complex medical needs, with or without a diagnosis, frequently requires the parent to learn about and provide medical interventions, act as a care coordinator, and be an advocate for their child (Cady & Belew, 2017; Spiers & Beresford, 2017) and parents in our study who are actively engaged in their children’s healthcare are reflective of this process.

Effects of duration of illness, age of children and gender on the findings

A longer duration of illness and older age of the child were associated with higher coping self-efficacy, but were not associated with tolerance for uncertainty or healthcare engagement. This pattern suggests that parents who have been on the diagnostic odyssey longer and have older children are developing better coping and self-efficacy skills, and that irrespective of these factors, they remain actively engaged in the child’s medical care with an acceptance that some degree of uncertainty is inevitable.

We also identified gender differences on our measures. The significantly higher scores in the mothers’ healthcare engagement and the suggestion of greater tolerance for uncertainty, may be related to the traditional role that parents may take with mothers having a more active role in a child’s health care (Cohen, 1999). Indeed, mothers predominantly identified themselves as the main contact person in the UDN for their child in our cohort as well. Mothers may thus, have a greater opportunity to ask questions and develop collaborations with health care providers, possibly resulting in greater tolerance for an uncertain health outcome for their child. A larger sample size may help in determining the relationship between gender and tolerance for uncertainty. We did not identify any gender differences in depression, anxiety, or coping self-efficacy. Thus, both mothers and fathers need the same level of support for anxiety and depression symptoms.

Effects of prior non-diagnostic WES

Approximately 50% of the children had had a prior non-diagnostic WES, attesting to the intractability of their disorders to the diagnostic process. Surprisingly, we found no significant differences in any of the measures in parents whose children had prior WES, compared to those that had not. We had surmised that we would see higher rates of depression in the subset that had had a non-diagnostic WES, since they would have faced the possibility that there were no other diagnostic options available to them. We did find a medium effect size for higher healthcare engagement in those who had had prior non-diagnostic WES and this should be explored in in larger sample size. The diagnostic rate for the Duke UDN is approximately 34%, and thus the majority of children enrolled in the UDN will remain undiagnosed. It will be important to follow up with parents once the outcome of their child’s evaluation is known to determine the effect of diagnostic outcome on the parental psychosocial profiles. We have also previously reported that parents worry about the possibility that their child’s WES could identify a life limiting disorder (McConkie-Rosell et al., 2016) and that the disorder could get worse (Spillmann et al., 2017). This anticipatory concern about results from genomic sequencing may be a factor in the anxiety and depression found in the parents whose children are in the UDN. Following families through the research process of the UDN with a larger cohort of parents would clarify these issues.

Study limitations

Parents are required to take an active role in the UDN process, including filling in the application form, facilitating medical record collection, traveling to the Duke clinical site, and enduring several consultations/tests during the evaluation. This process may be a barrier to those families who do not have the emotional fortitude to continue the journey towards a diagnosis, despite the Duke UDN site providing all evaluations at no cost to the family and supporting their travel. Thus, this study may inherently be biased toward those with previously high coping self-efficacy and health care empowerment. Additionally, acceptance into the network may have also have influenced parental perceptions of these two factors. We did not collect socioeconomic indicators such as educational level and occupation, which could have had an influence on participation in the study. As this study is cross-sectional, it is not possible to determine causality nor change over time in the measures. We also did not ascertain if the parents had sought interventions for the depression and anxiety that may have affected the data we gathered. The sample size is also small and limited to English speakers, but is representative of parents whose children have been evaluated at the Duke UDN clinical site.

Conclusion

Overall our findings suggest that parents of children with undiagnosed diseases maintain positive coping self-efficacy, remain actively engaged in healthcare and are tolerant of uncertainty, but these come with a high emotional cost to the parents, with at least a third experiencing depression and anxiety. Gender differences are predominantly related to mothers being more engaged in the children’s healthcare. The high rates of anxiety and depression in the parents may not be obvious to clinicians due to their ability to act on their child’s behalf. Thus, screening for anxiety and depression and treatment if identified is essential, in addition to providing services for the children, to optimize their mental health and quality of life. It will be important to follow these parental profiles longitudinally, since if a diagnosis is made through the UDN, the prognosis and possible medical management would be expected to have an effect on the psychological well-being of the parents (Peay et al., 2016).

Supplementary Material

Table S1: Differences in psychosocial profiles in parents whose children had a prior non-diagnostic WES and those that were WES naïve

Acknowledgments

Funding: Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the NIH Common Fund, through the Office of Strategic Coordination/Office of the NIH Director under Award Numbers U01HG007672 (Shashi V and Goldstein DB) and U01HG007703 (Palmer C). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Declarations

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethics approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The data gathered for this study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the National Human Genome Research Institute (15-HG-0130) and Duke University Medical Center (Pro00056651).

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication: Not applicable

Availability of data and materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ Contributions: AMR, VS, and SH contributed equally to project in terms of design of study, analysis of study data, coordination of project, and manuscript preparation and drafting. LP, YHJ, KS, RS, CP, and HC all participated in drafting of the manuscript. KS and RS assisted in data collection. The Undiagnosed Diseases Network is responsible for application (patient) allocation to the Duke UDN site. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Undiagnosed Diseases Network Members (October 2017)

David R. Adams, Mercedes E. Alejandro, Patrick Allard, Euan A. Ashley, Mahshid S. Azamian, Carlos A. Bacino, Ashok Balasubramanyam, Hayk Barseghyan, Gabriel F. Batzli, Alan H. Beggs, Hugo J. Bellen, Jonathan A. Bernstein, Anna Bican, David P. Bick, Camille L. Birch, Devon Bonner, Braden E. Boone, Bret L. Bostwick, Lauren C. Briere, Donna M. Brown, Matthew Brush, Elizabeth A. Burke, Lindsay C. Burrage, Shan Chen, Gary D. Clark, Terra R. Coakley, Joy D. Cogan, Cynthia M. Cooper, Heidi Cope, William J. Craigen, Precilla D'Souza, Mariska Davids, Jean M. Davidson, Jyoti G. Dayal, Esteban C. Dell'Angelica, Shweta U. Dhar, Ani Dillon, Katrina M. Dipple, Laurel A. Donnell-Fink, Naghmeh Dorrani, Daniel C. Dorset, Emilie D. Douine, David D. Draper, Annika M. Dries, David J. Eckstein, Lisa T. Emrick, Christine M. Eng, Gregory M. Enns, Ascia Eskin, Cecilia Esteves, Tyra Estwick, Liliana Fernandez, Paul G. Fisher, Brent L. Fogel, Noah D. Friedman, William A. Gahl, Emily Glanton, Rena A. Godfrey, David B. Goldstein, Sarah E. Gould, Jean-Philippe F. Gourdine, Catherine A. Groden, Andrea L. Gropman, Melissa Haendel, Rizwan Hamid, Neil A. Hanchard, Lori H. Handley, Matthew R. Herzog, Ingrid A. Holm, Jason Hom, Ellen M. Howerton, Yong Huang, Howard J. Jacob, Mahim Jain, Yong-hui Jiang, Jean M. Johnston, Angela L. Jones, David M. Koeller, Isaac S. Kohane, Jennefer N. Kohler, Donna M. Krasnewich, Elizabeth L. Krieg, Joel B. Krier, Jennifer E. Kyle, Seema R. Lalani, C. Christopher Lau, Jozef Lazar, Brendan H. Lee, Hane Lee, Shawn E. Levy, Richard A. Lewis, Sharyn A. Lincoln, Allen Lipson, Sandra K. Loo, Joseph Loscalzo, Richard L. Maas, Ellen F. Macnamara, Calum A. MacRae, Valerie V. Maduro, Marta M. Majcherska, May Christine V. Malicdan, Laura A. Mamounas, Teri A. Manolio, Thomas C. Markello, Ronit Marom, Julian A. Martínez-Agosto, Shruti Marwaha, Thomas May, Allyn McConkie-Rosell, Colleen E. McCormack, Alexa T. McCray, Jason D. Merker, Thomas O. Metz, Matthew Might, Paolo M. Moretti, John J. Mulvihill, Jennifer L. Murphy, Donna M. Muzny, Michele E. Nehrebecky, Stan F. Nelson, J. Scott Newberry, John H. Newman, Sarah K. Nicholas, Donna Novacic, Jordan S. Orange, J. Carl Pallais, Christina GS. Palmer, Jeanette C. Papp, Neil H. Parker, Loren DM. Pena, John A. Phillips III, Jennifer E. Posey, John H. Postlethwait, Lorraine Potocki, Barbara N. Pusey, Chloe M. Reuter, Amy K. Robertson, Lance H. Rodan, Jill A. Rosenfeld, Jacinda B. Sampson, Susan L. Samson, Kelly Schoch, Molly C. Schroeder, Daryl A. Scott, Prashant Sharma, Vandana Shashi, Edwin K. Silverman, Janet S. Sinsheimer, Kevin S. Smith, Ariane G. Soldatos, Rebecca C. Spillmann, Kimberly Splinter, Joan M. Stoler, Nicholas Stong, Jennifer A. Sullivan, David A. Sweetser, Cynthia J. Tifft, Camilo Toro, Alyssa A. Tran, Tiina K. Urv, Zaheer M. Valivullah, Eric Vilain, Tiphanie P. Vogel, Daryl M. Waggott, Colleen E. Wahl, Nicole M. Walley, Chris A. Walsh, Michael F. Wangler, Patricia A. Ward, Katrina M. Waters, Bobbie-Jo M. Webb-Robertson, Monte Westerfield, Matthew T. Wheeler, Anastasia L. Wise, Lynne A. Wolfe, Elizabeth A. Worthey, Shinya Yamamoto, Yaping Yang, Guoyun Yu, Diane B. Zastrow, Chunli Zhao, Allison Zheng

References

- Angelis A, Tordrup D, Kanavos P. Socio-economic burden of rare diseases: A systematic review of cost of illness evidence. Health Policy. 2015;119(7):964–979. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bally J, Holtslander L, Duggleby W, Wright K, Thomas R, Spurr S, Mpofu C. Understanding Parental Experiences Through Their Narratives of Restitution, Chaos, and Quest: Improving Care for Families Experiencing Childhood Cancer. J Fam Nurs. 2014;20:287–312. doi: 10.1177/1074840714532716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Besier T, Born A, Henrich G, Hinz A, Quittner AL, Goldbeck L. Anxiety, depression, and life satisfaction in parents caring for children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011;46(7):672–682. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cady RG, Belew JL. Parent Perspective on Care Coordination Services for Their Child with Medical Complexity. Children. 2017;4(6) doi: 10.3390/children4060045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael N, Tsipis J, Windmueller G, Mandel L, Estrella E. “Is it Going to Hurt?”: The Impact of the Diagnostic Odyssey on Children and Their Families. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2015;24(2):325–335. doi: 10.1007/s10897-014-9773-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney M, Neilands T, Chambers D, Taylor J, Folkman S. A validity and reliability study of the coping self-efficacy scale. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11(Pt 3):421–437. doi: 10.1348/135910705x53155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong JX, Buckingham KJ, Jhangiani SN, Boehm C, Sobreira N, Smith JD, … Bamshad MJ. The Genetic Basis of Mendelian Phenotypes: Discoveries, Challenges, and Opportunities. Am J Hum Genet. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson A, Howson CP, Modell B. March of Dimes Global Report on Birth Defects: The hidden toll of dying and disabled children. March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation; 2006. http://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/globalreport-on-birth-defects-the-hidden-toll-of-dying-and-disabledchildren-executive-summary.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M. Families coping with childhood chronic illness: A research review. Families, Systems & Health. 1999:149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch PC, Rose CD, Johnson M, Janson SL. A pilot study to evaluate the magnitude of association of the use of electronic personal health records with patient activation and empowerment in HIV-infected veterans. PeerJ. 2015;3:e852. doi: 10.7717/peerj.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dear BF, Titov N, Sunderland M, McMillan D, Anderson T, Lorian C, Robinson E. Psychometric comparison of the generalized anxiety disorder scale-7 and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire for measuring response during treatment of generalised anxiety disorder. Cogn Behav Ther. 2011;40(3):216–227. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.582138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellve L. Stress and well-being among parents of children with rare diseases: a prospective intervention study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006;53(4):392–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll KA, Montag-Leifling K, Acton JD, Modi AC. Relations between depressive and anxious symptoms and quality of life in caregivers of children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44(8):784–792. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eurordis. Rare Diseases: Understanding this Public Health Priority. 2005 www.eurordis.org.

- Frank A. The wounded storyteller. The University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Guillamon N, Nieto R, Pousada M, Redolar D, Munoz E, Hernandez E, … Gomez-Zuniga B. Quality of life and mental health among parents of children with cerebral palsy: the influence of self-efficacy and coping strategies. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(11–12):1579–1590. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz A, Klein AM, Brahler E, Glaesmer H, Luck T, Riedel-Heller SG, … Hilbert A. Psychometric evaluation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener GAD-7, based on a large German general population sample. J Affect Disord. 2017;210:338–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.012. https://globalgenes.org. (2015). Rare Disease Statistics. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. The shifting landscape of health care: toward a model of health care empowerment. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(2):265–270. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2009.189829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M, Rose C, Dilworth S, Neilands T. Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of Health Care Empowerment: development and validation of the Health Care Empowerment inventory. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KR, Lee E, Namkoong K, Lee YM, Lee JS, Kim HD. Caregiver's Burden and Quality of Life in Mitochondrial Disease. Pediatric Neurology. 2010;42(4):271–271. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocalevent RD, Hinz A, Brahler E. Standardization of the depression screener patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(5):551–555. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C, Skirton H, Jones R. Living without a diagnosis: the parental experience. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2010;14(6):807–815. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingen M, Albers L, Borchers M, Haass S, Gärtner J, Schröder S, … Zirn B. Obtaining a genetic diagnosis in a child with disability: impact on parental quality of life. Social and Behavioural Research in Clinical Genetics. 2016;89:2258–266. doi: 10.1111/cge.12629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeo AC, O'Brien KE, Bernhardt BA, Biesecker BB. Factors Associated With Perceived Uncertainty Among Parents of Children With Undiagnosed Medical Conditions. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2012;158A(8):1877–1884. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConkie-Rosell A, Pena LD, Schoch K, Spillmann R, Sullivan J, Hooper SR, … Shashi V. Not the End of the Odyssey: Parental Perceptions of Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) in Pediatric Undiagnosed Disorders. J Genet Couns. 2016;25(5):1019–1031. doi: 10.1007/s10897-016-9933-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscara F, Burke K, McCarthy MC, Anderson VA, Hearps SJ, Hearps SJ, … Nicholson JM. Parent distress reactions following a serious illness or injury in their child: a protocol paper for the take a breath cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1):153. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0519-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscara F, McCarthy M, Woolf C, Hearps S, Burke K, Anderson V. Early psychological reactions in parents of children with a life threatening illness within a pediatric hospital setting. European Psychiatry. 2015;30(5) doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Need AC, Shashi V, Hitomi Y, Schoch K, Shianna KV, McDonald MT, … Goldstein DB. Clinical application of exome sequencing in undiagnosed genetic conditions. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2012;49(6):353–361. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nettleton S, Watt I, O'Malley L, Duffey P. Understanding the narratives of people who live with medically unexplained illness. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56(2):205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peay HL, Meiser B, Kinnett K, Furlong P, Porter K, Tibben A. Mothers' psychological adaptation to Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24(5):633–637. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelchat D, Levert M-J, Bourgeois-Guérin V. How do mothers and fathers who have a child with a disability describe their adaptation/transformation process? Journal of Child Health care. 2009;13(3):239–259. doi: 10.1177/1367493509336684. doi:0.1177/1367493509336684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelentsov LJ, Laws TA, Esterman AJ. The supportive care needs of parents caring for a child with a rare disease: A scoping review. Disability and Health Journal. 2015;8(4):475–491. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry A, Sarlo-McGarvey N, Factor DC. Stress and Family Functioning in Parents of Girls with Rett Syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1992;22(2):235–248. doi: 10.1007/BF01058153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal ET, Biesecker LG, Biesecker BB. Parental attitudes toward a diagnosis in children with unidentified multiple congenital anomaly syndromes. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2001;103(2):106–114. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas BL, Rodríguez VY, Urbieta CT, Cuadrado E. The role of coping strategies and self-efficacy as predictors of life satisfaction in a sample of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Psicothema. 2017;29(1):55–60. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2016.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M, Steele R, Cadell S, Hemsworth D. Differences on psychosocial outcomes between male and female caregivers of children with life-limiting illnesses. J Pediatr Nurs. 2011;26(3):186–199. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner D, Raspberry KA, King M. The nuanced negative: Meanings of a negative diagnostic result in clinical exome sequencing. Sociol Health Illn. 2016;38(8):1303–1317. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiers G, Beresford B. “It goes against the grain”: A qualitative study of the experiences of parents’ administering distressing health- care procedures for their child at home. Health Expectations: an International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy. 2017 doi: 10.1111/hex.12532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillmann RC, McConkie-Rosell A, Pena L, Jiang YH, Schoch K, Walley N, … Shashi V. A window into living with an undiagnosed disease: illness narratives from the Undiagnosed Diseases Network. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):71. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0623-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truitt M, Biesecker B, Capone G, Bailey T, Erby L. The role of hope in adaptation to uncertainty: The experience of caregivers of children with Down syndrome. Patient Education and Counseling. 2012;87(2):233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg JJ, Neilands TB, Johnson MO, Chen B, Saberi P. Using Path Analysis to Evaluate the Healthcare Empowerment Model Among Persons Living with HIV for Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30(11):497–505. doi: 10.1089/apc.2016.0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waszczuk MA, Zavos HM, Gregory AM, Eley TC. The stability and change of etiological influences on depression, anxiety symptoms and their co-occurrence across adolescence and young adulthood. Psychol Med. 2016;46(1):161–175. doi: 10.1017/s0033291715001634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead LC. Quest, chaos and restitution: living with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(9):2236–2245. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanes T, Humphreys L, McInerney-Leo A, Biesecker B. Factors Associated with Parental Adaptation to Children with an Undiagnosed Medical Condition. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10897-016-0060-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurynski Y, Deverell M, Dalkeith T, Johnson S, Christodoulou J, Leonard H E. J. E. a. A. R. D. I. o. F. S group. Australian children living with rare diseases: experiences of diagnosis and perceived consequences of diagnostic delays. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2017;12(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0622-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: Differences in psychosocial profiles in parents whose children had a prior non-diagnostic WES and those that were WES naïve