Abstract

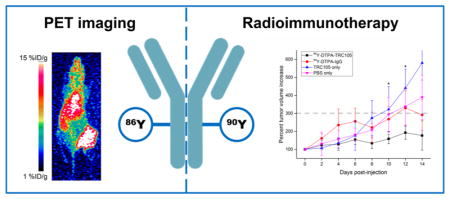

Angiogenesis is widely recognized as one of the hallmarks of cancer. Therefore, imaging and therapeutic agents targeted to angiogenic vessels may be widely applicable in many types of cancer. To this end, the theranostic isotope pair, 86Y and 90Y, were used to create a pair of agents for targeted imaging and therapy of neovasculature in murine breast cancer models using a chimeric anti-CD105 antibody, TRC105. Serial positron emission tomography imaging with 86Y-DTPA-TRC105 demonstrated high uptake in 4T1 tumors, peaking at 9.6 ± 0.3%ID/g, verified through ex vivo studies. Additionally, promising results were obtained in therapeutic studies with 90Y-DTPA-TRC105, wherein significantly (p < 0.05) decreased tumor volumes were observed for the targeted treatment group over all control groups near the end of the study. Dosimetric extrapolation and tissue histological analysis corroborated trends found in vivo. Overall, this study demonstrated the potential of the pair 86/90Y for theranostics, enabling personalized treatments for cancer.

Keywords: angiogenesis, CD105/endoglin, positron emission tomography (PET), radioimmunotherapy, yttrium-86, yttrium-90, theranostics, cancer

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Treatments targeted to angiogenic vessels have shown great promise in treating cancer, both clinically and preclinically,1 mostly targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor pathway. However, resistance often occurs when these inhibitory agents are used, therefore warranting the use of combination therapy. One such option is radioimmunotherapy, or targeted radionuclide therapy,2 using beta-emitting isotopes such as 90Y or 177Lu. As angiogenesis is a nearly universal characteristic of solid tumors, radioimmunotherapy agents that target these new blood vessels may find application in a wide range of cancer settings. CD105, or endoglin, is one of the markers that is overexpressed on angiogenic vessels in many cancers and not found on many other tissues.3

Theranostic approaches, or the combination of both therapeutic and diagnostic entities, have been gaining traction in the preclinical and clinical cancer realms in recent years.4 Additionally, the use of companion diagnostic tests for selecting patients to proper therapies has shown its value, resulting in decreased treatment discontinuation and fewer side effects for patients selected by these companion diagnostics.5,6 While the majority of these tests are biopsy-based, imaging techniques have begun to show promise for selecting patients for targeted therapies.7,8 Given the wide range of radiometals that have been reported to date, the development of companion diagnostics and treatment options using theranostic pairs is quite attractive.

One such example of a theranostic pair is 86Y and 90Y. While 86Y emits positrons with a 33% branching ratio and a 14.7 h half-life, 90Y is a pure, moderately high, beta emitter with a 64 h half-life. 90Y-based radiopharmaceuticals have demonstrated success in a number of radioimmunotherapy trials;9–11 however, the lack of quantitative imaging options with this nuclide makes dosimetric estimation and tracking of the radiopharmaceutical challenging. Therefore, the use of a separate isotope of yttrium, 86Y, allows visualization of the tracer distribution and estimation of radiation dosimetry, while utilizing the exact same chemical entity as the therapeutic agent.12 We therefore set out to develop and evaluate a theranostic pair of agents using 86/90Y and an antibody targeting overexpressed CD105 on angiogenic vessels, TRC105.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Tracer Preparation

TRC105 (TRACON Pharmaceuticals) was prepared for radiolabeling through conjugation of diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA, Macrocyclics) as reported previously.13 The binding properties of DTPA-TRC105 have been evaluated in our previous works.13 The nonspecific isotype control IgG (Invitrogen) was prepared following the same protocol.

Cell Culture and Animal Models

4T1 murine breast cancer cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured using standard procedures (RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS, 37 °C, 5% CO2). Cells were used for in vivo experiments at approximately 75% confluence. All experiments involving animals were conducted under an approved protocol by the University of Wisconsin–Madison Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Female BALB/c mice (Envigo) were inoculated with a 1:1 mixture of 4T1 cells and Matrigel (BD Biosciences) in the lower flank when they were 4–5 weeks old. Mice were used for therapeutic studies when tumors were approximately 8–10 mm in diameter.

86Y Production and Antibody Radiolabeling

86Y (t1/2 = 14.7 h, 31.9% β+, Eβ+ave = 660 keV) was produced using a 16 MeV GE PETtrace cyclotron via the transmutation reaction 86Sr(p,n)86Y from enriched 86SrCO3 targets of pressed powder. The subsequent radiochemical isolation of 86Y from the irradiated 86SrCO3 was carried out as previously described.14 Briefly, the target material was dissolved in concentrated HCl and then neutralized with NH4OH. The resulting 86Y(OH)3 precipitate was filtered and washed thoroughly with deionized water to remove remaining traces of strontium. The final noncarrier-added 86Y stock solution was obtained by redissolving the 86Y(OH)3 powder in 0.1 M HCl. All activity measurements were performed in a Capintec CRC-15R dose calibrator.

DTPA-TRC105 was incubated with 86YCl3 in sodium acetate buffer, following similar procedures as previously reported.13 After an hour-long incubation at 37 °C, a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare) was used for purification of the radiolabeled antibody, using PBS 1× as the mobile phase. Radiolabeling yields were measured via iTLC and were consistently above 75% for both 86Y-DTPA-TRC105 and 86Y-DTPA-IgG.

PET Imaging and Biodistribution Studies

Mice bearing subcutaneous 4T1 murine breast cancer xenografts were injected via the tail vein with 3–6 MBq of either 86Y-DTPA-TRC105 or 86Y-DTPA-IgG. PET scans of 20–30 million coincidence events per mouse were obtained using an Inveon PET/CT scanner (Siemens) at 0.5, 12, 24, and 48 h postinjection. Measurements of regions-of-interest in PET images were completed using the Inveon Research Workspace (Siemens).

Following the final imaging time point, mice were euthanized via CO2 asphyxiation, and major organs were excised, wet-weighed, and their radioactive contents were measured using a gamma counter (PerkinElmer). Results of PET ROI analysis and biodistribution studies are presented as %ID/g.

Therapeutic Administration

90Y-labeled TRC105 and IgG were prepared using similar methods as for the preparation of PET tracers. DTPA-TRC105 and DTPA-IgG were incubated with 100–150 MBq of 90YCl3 in sodium acetate buffer for 1 h at 37 °C, purified via PD-10 columns, and then prepared for injection.

All agents were prepared for administration via tail vein injection in sterile PBS 1×. Treatment groups are outlined in Table 1. Each treatment group contained 5–6 mice bearing subcutaneous 4T1 tumor xenografts, with therapeutic agent dosing determined from previous studies and literature.15

Table 1.

Groups and Doses for the Radioimmunotherapy Studya

| treatment group | therapeutic agent |

|---|---|

| 90Y-DTPA-TRC105 | ~4.4 MBq 90Y-DTPA-TRC105 |

| 90Y-DTPA-IgG | ~4.4 MBq 90Y-DTPA-IgG (human isotype IgG control) |

| TRC105 only | 45 μg of TRC105 in 50 μL of PBS 1× |

| PBS only | 50 μL of PBS 1× |

n = 5–6 per group.

Treatment Monitoring and Cherenkov Imaging

Following administration of therapeutic agents, mice were monitored every other day. Measurements of tumor dimensions were made using digital calipers, and body weight was recorded as well. Tumor volume was calculated using length × width2, and relative tumor volume increase was calculated by dividing the current tumor volume by that which was measured on the day of therapeutic administration. At the same time, Cherenkov luminescence imaging was performed using an IVIS optical imaging system (PerkinElmer) with an open filter to map the distribution of 90Y-containing agents. Mice were anesthetized and placed in the lateral decubitus position, such that the tumor was facing upward. Exposures of 60 s were recorded. Before administration of therapeutics, and at 7 and 14 days postinjection, blood samples were collected via retro-orbital bleed, and complete blood counts were analyzed using an Abaxis VetScan HM5 Hematology analyzer. Humane end points were set to a tumor volume increase of more than 300%, body weight drop of more than 20%, or if general health was deemed to be too poor to continue. The study time was set to 14 days, given the half-life of 90Y (64 h).

Tissue Analysis

Major organs, including the 4T1 tumor, heart, liver, and kidneys, were excised from the treatment group mice following the conclusion of the study. Half of each organ was frozen in Optimal Cutting Temperature Compound (Tissue-Tek) for immunofluorescent analysis, while the other half was fixed for paraffin embedding and subsequent hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining.

Immunofluorescent staining for CD105, CD31, and DAPI was performed as previously reported.13 Slides were analyzed using a Nikon A1RS confocal microscope. H&E staining followed standard procedures, and slides were examined with a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope.

Radiation Dosimetry

With the use of OLINDA/EXM software,16 the biodistribution data obtained from PET ROI analysis of 86Y-DTPA-TRC105 was used to extrapolate radiation absorbed doses to an adult female following administration of 90Y-DTPA-TRC105. The dose-to-sphere modeling capability of the software was also utilized to determine tumor doses from 90Y-DTPA-TRC105.

Statistical Analysis

All quantitative data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Direct comparisons between groups were made using a two-sided Student’s t test, where p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

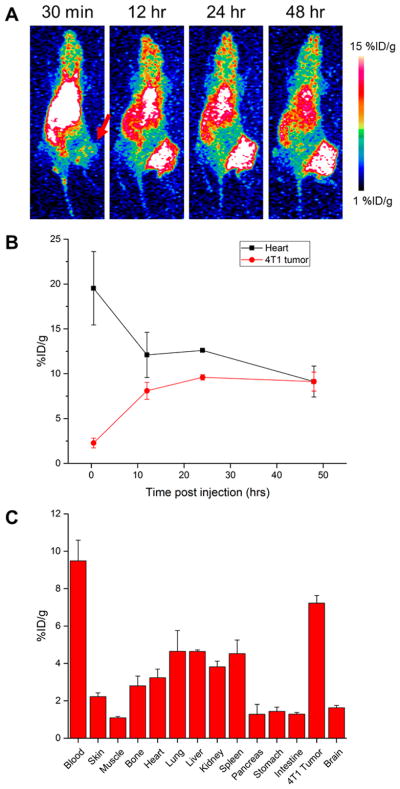

PET Imaging Visualizes 86Y-DTPA-TRC105 Uptake in Tumors

Following injection of 3–6 MBq of 86Y-DTPA-TRC105, serial PET images were acquired at 30 min as well as 12, 24, and 48 h postinjection of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice (Figure 1). Tumors were clearly visualized after 12 h, when tumor uptake was 8.1 ± 0.6 %ID/g (n = 4); additionally, this uptake further increased and peaked at 9.6 ± 0.3 %ID/g at 24 h postinjection (Figure 1B). The tracer cleared slowly from circulation, with 19.5 ± 4.1 %ID/g in the blood pool at 30 min, and 9.1 ± 1.7 %ID/g remaining at 48 h. Consistent with the clearance kinetics of antibody-based agents, the liver was the off-target organ with the highest tracer accumulation (7.1 ± 0.9 %ID/g at 48 h).

Figure 1.

PET imaging of 86Y-DTPA-TRC105. (A) Serial representative PET MIP images reveal prominent uptake in the 4T1 tumor, indicated by a red arrow. (B) ROI analysis of blood pool and tumor uptake. (C) Ex vivo biodistribution of 86Y-DTPA-TRC105 at 48 h postinjection, n = 4.

Similar studies were conducted using 86Y-DTPA-IgG, an isotype control antibody (Figure S1). Tumor uptake peaked in this group at 48 h postinjection at 8.6 ± 1.0 %ID/g. Similar clearance patterns were observed with this tracer, with liver accumulation of 8.1 ± 1.4 %ID/g observed at the last time point.

While not statistically significant, higher tumor-to-normal tissue ratios with 86Y-DTPA-TRC105 were calculated for all analyzed organs at the last time point over the nonspecific tracer (Tables S1 and S2). Tumor-to-muscle ratios peaked at 6.2 ± 1.1 for the specific tracer and 5.2 ± 1.8 for the nonspecific, both at 48 h postinjection. Similarly, the tumor-to-blood ratio for 86Y-DTPA-TRC105 was 1 ± 0.2 at 48 h, and 0.8 ± 0.2 for 86Y-DTPA-IgG at the same time point.

Ex Vivo Studies Verify PET Imaging Results

Following the last imaging time point, mice were euthanized, and main organs were excised, wet-weighed, and their radioactive contents were measured (Figure 1C). Tumor uptake of 86Y-DTPA-TRC105 was 7.22 ± 0.41% ID/g, while liver uptake was 4.64 ± 0.08 %ID/g. These values were slightly lower than those measured from ROI analysis, likely a result of the difficulty in quantifying 86Y due to the presence of many emitted gammas; however, similar trends were observed from ex vivo studies as were found from PET ROI analysis. For the nonspecific tracer, 4T1 tumor uptake was calculated as 5.67 ± 1.25 %ID/g, and the liver was calculated as 5.01 ± 0.99 %ID/g.

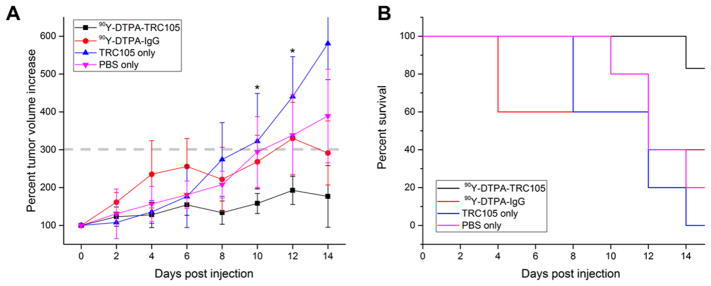

90Y Treatments Show Promising Therapeutic Effect

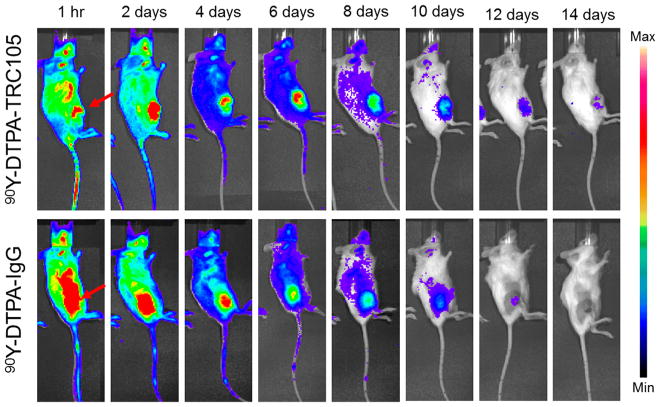

Following treatment with ~4.4 MBq of 90Y-DTPA-TRC105, tumor growth was inhibited relative to control groups, with significantly smaller tumor volume for the targeted group than all others at both 10 and 12 days postinjection (p < 0.05, n = 5–6). None of the mice in the 90Y-DTPA-TRC105 group reached the tumor volume end point criteria (>300% of initial) within the 2 week study, while 3 of the mice treated with 90Y-DTPA-IgG did, and 4/5 PBS-treated and 6/6 TRC105-treated mice did as well (Figure 2). This provided strong evidence of a therapeutic effect from radioimmunotherapy using 90Y and TRC105 to target tumor vessels. Cherenkov imaging of the 90Y-DTPA-TRC105 and 90Y-DTPA-IgG groups visualized uptake of the agent within the 4T1 tumors, which persisted slightly longer in the targeted over the nontargeted group (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Results of the therapeutic study. (A) Average (±SD) tumor volumes for all groups over the 14 day study. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival curve. *p < 0.05 for 90Y-DTPA-TRC105 group as compared to all others, n = 5–6 per group.

Figure 3.

Serial Cherenkov imaging. Tumors are indicated by red arrows.

Monitoring Therapeutic Side Effects Reveals Toxicity

While all of the mice treated with 90Y-DTPA-TRC105 showed significantly slowed tumor growth, mice in this group, as well as in the 90Y-DTPA-IgG group, demonstrated evidence of notable toxicity from the radioimmunotherapy treatments (Figure S2). At the conclusion of the study, 2/6 90Y-DTPA-TRC105-treated mice were close to the weight-loss end point (<80% of initial), and one mouse had died, presumably due to treatment complications. Similar trends were evident within the 90Y-DTPA-IgG group, although all mice reached the tumor growth end point prior to the weight-loss end point.

Complete blood count analysis was performed prior to injection and at 7 and 14 days post-therapy injection for the 90Y-DTPA-TRC105 group (Figure S2B). When compared to pretreatment values, significant drops in white blood cell, lymphocyte, monocyte, and neutrophil absolute counts were observed, which persisted throughout the study. Decreases were also noted in platelet counts; however, this value was slightly recovered at 14 days postinjection compared to day 7.

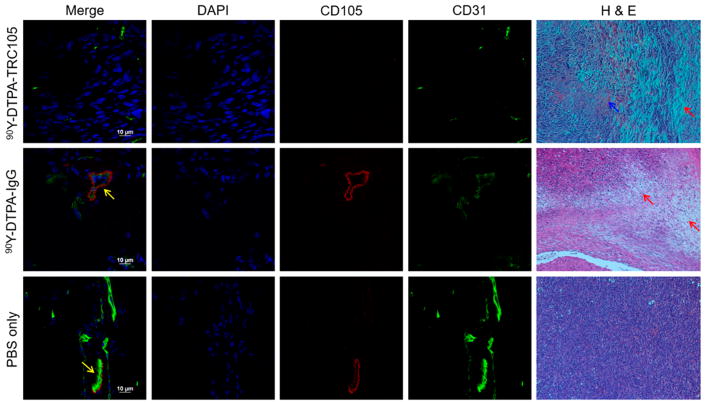

Tissue Analysis Verifies Therapeutic and Toxic Effects

Both immunofluorescent staining and H&E staining were performed on tissues excised from mice in the treatment groups (Figures 4 and S3). Immunofluorescent staining for CD31 and CD105 revealed colocalization of these signals on new blood vessels in 4T1 tumors in the PBS and 90Y-DTPA-IgG groups; however, no CD105 staining was observed in the 90Y-DTPA-TRC105 group, indicating efficient targeting to and killing of these vessels.

Figure 4.

Immunofluorescent and H&E staining of tumor tissues. Colocalization of CD31 and CD105, indicated by yellow arrows, shows angiogenic vessels. H&E staining visualized notable damage to 90Y-treated tumors, with red arrows pointing out representative damaged areas, and blue arrows indicating hemorrhaging.

H&E staining showed significant damage to 4T1 tumors in mice injected with 90Y-DTPA-TRC105, with significant hemorrhaging throughout (Figure 4). Tumors from PBS-only mice were necrotic in the centers due to their large size, with the edges of the tumor still showing viable growing tissue. Tumors from the 90Y-DTPA-IgG group demonstrated slight damage and necrosis as well. The liver was the only off-target organ with noticeable damage evident in stained tissues (Figure S3), likely due to the clearance of the 90Y-labeled antibodies through this organ.

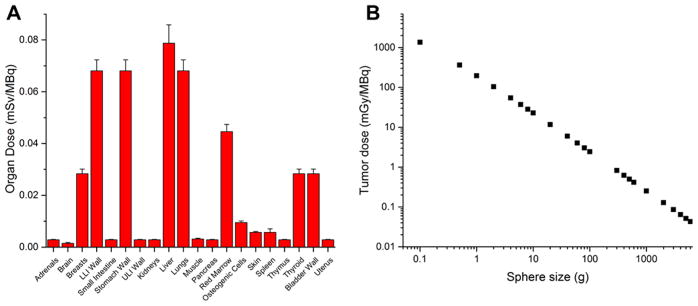

Dosimetric Extrapolation Using PET Data

With the use of OLINDA/EXM, dosimetric extrapolation to an adult human female was performed with 86Y-DTPA-TRC105 ROI data (Figure 5A), using 90Y decay data. As expected, the off-target organ with the highest dose was the liver, at 0.079 ± 0.007 mSv/MBq (n = 4). Given the high uptake of the tracer in this organ, and the long range of the beta particles from 90Y, notable doses were also calculated for the stomach wall and colon. In a similar manner, using the dose-to-sphere capabilities of OLINDA, tumor doses were estimated (Figure 5B). For example, for a 1 g tumor mass, a dose of 197 ± 11 mGy/MBq was calculated.

Figure 5.

Dosimetric evaluation of 90Y-DTPA-TRC105. (A) Doses to off-target organs. (B) Dose-to-sphere modeling of tumors of various sizes. N = 4.

DISCUSSION

The use of companion diagnostics and theranostic strategies is gaining traction in clinical cancer treatments, providing more guidance for treatment decisions and greater personalization. Most of these tests to date are based on tissue biopsies and ex vivo analysis of specific markers; however, imaging-based techniques show increased potential, as they may provide whole-body information, among other benefits.17 The theranostic pair of 86Y and 90Y thus may be promising for nuclear-medicine-based patient stratification (through PET imaging) and treatment (using radioimmunotherapy).18 Herein, we report the imaging and therapy of highly angiogenic murine breast cancer models using an antibody targeted to CD105 and labeled with various isotopes of yttrium, 86/90Y-DTPA-TRC105. As TRC105 itself has demonstrated limited therapeutic effects clinically,19,20 we hypothesized that conjugating it with a beta-emitting nuclide (90Y) would allow for efficient radioimmunotherapy. While Cherenkov imaging is possible with 90Y, since the emitted beta has high energy, this signal is limited to only superficial tissues21 and is not quantitative, necessitating the use of another means of visualizing whole-body signals. Positron emission tomography with 86Y solves the tissue penetration issue, as this nuclear imaging technique provides extremely high sensitivity at all tissue depths.

Antiangiogenic therapies have, in general, shown limited efficacy in cancer patients due to the nearly inevitable regrowth of tumors after treatment ceases and the development of resistance to the therapies.22,23 We hypothesize that combining these treatments with targeted radiotherapy will bypass some of these resistance and regrowth mechanisms by destroying the targeted cells, rather than simply inhibiting pathways.

There have been few reports of PET imaging with 86Y in the literature,24 likely since this isotope is not yet readily commercially available; additionally, the majority of reports to date employ small molecule or peptide tracers. However, its cyclotron-based production is being optimized, and we expect this trend to change in the near future as a result. Having an imaging counterpart to the widely used 90Y is certainly invaluable; nevertheless, PET imaging with 86Y is not without its own issues. As a nonpure positron emitter, well over half of the decays from 86Y are accompanied by gamma emissions, which cause a great deal of false coincidence readings and confound imaging and quantification results. The thorough characterization of these decays and proper calibrations are thus very important.25 In our study, this high background, while well-characterized, is clearly evident in the PET images, in which minimum values for visualization were set to 1 %ID/g, rather than the typical 0 %ID/g. Even given these challenges, PET imaging with 86Y-DTPA-TRC105 was able to clearly delineate tumors in our study at all time points after 12 h postinjection. We have previously published imaging results of TRC105 in 4T1 murine breast cancer models using a variety of radioisotopes;26–28 however, this was our first experience with 86Y. The results observed in this study are consistent with those we have reported previously, further validating the use of 86Y in PET imaging of antibodies, especially in theranostic settings employing 90Y. The identical radiolabeling chemistry to that of 90Y and suitable half-life of 86Y make it a promising PET isotope, as we have demonstrated herein.

4T1 murine tumors are highly aggressive and, as such, have very high levels of angiogenesis, making them a perfect model for imaging of agents targeted to neovasculature. However, along with the high levels of angiogenic markers, an increased enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect results from the fast growth of the tumors.29,30 This may explain the relatively high accumulation of the nonspecific tracer in tumors in this study. Future studies in which the biodistribution of the IgG tracer are mapped over a greater time may be warranted to further evaluate this finding. We have previously reported specific binding of TRC105 to vasculature cells, and minimal binding of the nonspecific IgG, and are thus confident that the specific tracer is, indeed, specific.13 Additionally, the elimination of CD105 expression in tumors from the targeted treatment group provided further verification of the tracer’s specificity. An additional means to explore the impact of the EPR effect would be to use orthotopic models, wherein the 4T1 cells would be implanted in the mammary pads of the mice. This would provide a more clinically relevant situation, with more realistic vasculature properties and growth patterns, but would require more sophisticated therapeutic monitoring, such as through transfected tumor cells for optical imaging, or CT imaging.

We observed promising therapeutic trends with 90Y-DTPA-TRC105 in this study. Tumor volumes were significantly decreased as compared to control groups near the end of the experimental period, and mice thus had increased survival in this group. However, these positive therapy results came at a price—there was evidence of significant hematoxicity in the groups treated with 90Y-labeled agents. The toxicity of these treatments may be explained by a few factors. First, antibody-based tracers have long circulation half-lives. While this is beneficial for maximizing tumor uptake of agents since the exposure time can be increased, this may also result in increased exposure of normal organs to the tracer. Additionally, 90Y is a relatively high-energy beta emitter, as the emitted particle has a range of over 1 cm in water. While this long-range may be advantageous in the treatment of solid tumors in humans, in a mouse model, a 1 cm range is quite large. There thus was likely a large amount of cross-fire between organs in the mouse, both while the tracer was still in circulation and once it was cleared into the liver. Notably, 90Y-labeled antibodies are finding applications in clinical cancer patients with hematological malignancies, taking advantage of the aforementioned blood toxicity to either destroy cancerous cells in the bloodstream or prepare for stem cell transplantation.11,31

A few strategies may be employed to reduce the toxicity observed. For one, the targeting ligand may be modified. Strategies such as pretargeting32,33 or antibody fragmentation34 may decrease the circulation time of the 90Y-labeled agent and as such reduce the associated side effects. Also, a radionuclide with a shorter beta range may be more desirable in murine models, to eliminate cross-fire effects. Optimization of dosing regimens (e.g., fractionated doses) may also have an impact.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated promising results using the theranostic pair of 86Y and 90Y. PET imaging with 86Y-DTPA-TRC105 verified high uptake in tumors, which was corroborated by ex vivo gamma counting studies. In therapy experiments, we observed significantly slowed tumor growth in mice using the targeted agent, 90Y-DTPA-TRC105. Further evidence of targeted therapy was provided through immunofluorescent staining, as no staining for CD105 was evident in tumor tissues treated with 90Y-DTPA-TRC105, whereas colocalization of CD105 and CD31 staining was found throughout tumors treated with either 90Y-DTPA-IgG or PBS. With use of biodistribution data from the imaging tracer, dosimetric extrapolation to an adult female human calculated doses that matched those expected, in line with the kinetics of an antibody-based tracer. Given the promising results obtained in this study, we believe that the obstacles encountered along the way (i.e., messy decay scheme of 86Y, side effects of therapy) are minor. Being able to track a chemical twin of a therapeutic entity will prove invaluable for treatment planning and monitoring of radioimmunotherapy treatments. While complete tumor eradication was not obtained with the current dosing schedule, significant tumor growth inhibition was observed, which may be synergistic with other treatment options, such as immunotherapy.35 We expect the theranostic pair 86/90Y to have a measurable impact in cancer patient care in the near future, enabling even more personalized treatment options.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by the University of Wisconsin–Madison, the National Institutes of Health (P30CA014520, T32CA009206, T32GM008505), and the American Cancer Society (125246-RSG-13-099-01-CCE).

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): C.P.T. is an employee of TRACON Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut. 8b00133.

Contains IgG PET images, results of toxicity monitoring, histological evaluation of nontumor tissues, and PET region-of-interest data (PDF)

References

- 1.Zhao Y, Adjei AA. Targeting Angiogenesis in Cancer Therapy: Moving Beyond Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor. Oncologist. 2015;20(6):660–673. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larson SM, Carrasquillo JA, Cheung N-KV, Press O. Radioimmunotherapy of human tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(6):347–360. doi: 10.1038/nrc3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nassiri F, Cusimano MD, Scheithauer BW, Rotondo F, Fazio A, Yousef GM, Syro LV, Kovacs K, Lloyd RV. Endoglin (CD105): A Review of its Role in Angiogenesis and Tumor Diagnosis, Progression and Therapy. Anticancer Res. 2011;31(6):2283–2290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jadvar H, Chen X, Cai W, Mahmood U. Radiotheranostics in Cancer Diagnosis and Management. Radiology. 2018;286(2):388–400. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017170346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ocana A, Ethier JL, Díez-González L, Corrales-Sánchez V, Srikanthan A, Gascón-Escribano MJ, Templeton AJ, Vera-Badillo F, Seruga B, Niraula S. Influence of Companion Diagnostics on Efficacy and Safety of Targeted Anti-Cancer Drugs: Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Oncotarget. 2015;6:39538–39549. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agarwal A, Ressler D, Snyder G. The Current and Future State of Companion Diagnostics. Pharmacogenomics Pers Med. 2015;8:99–110. doi: 10.2147/PGPM.S49493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris RT, Joyrich RN, Naumann RW, Shah NP, Maurer AH, Strauss HW, Uszler JM, Symanowski JT, Ellis PR, Harb WA. Phase II Study of Treatment of Advanced Ovarian Cancer with Folate-Receptor-Targeted Therapeutic (Vintafolide) and Companion SPECT-Based Imaging Agent (99mTc-etarfolatide) Ann Oncol. 2014;25:852–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Heertum RL, Scarimbolo R, Ford R, Berdougo E, O’Neal M. Companion diagnostics and molecular imaging-enhanced approaches for oncology clinical trials. Drug Des, Dev Ther. 2015;9:5215–5223. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S87561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dash A, Chakraborty S, Pillai MRA, Knapp FF. Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy: An Overview. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2015;30(2):47–71. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2014.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodei L, Cremonesi M, Grana C, Rocca P, Bartolomei M, Chinol M, Paganelli G. Receptor radionuclide therapy with 90Y-[DOTA]0-Tyr3-octreotide (90Y-DOTATOC) in neuroendocrine tumours. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31(7):1038–1046. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1571-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thakral P, Singla S, Vashist A, Yadav M, Gupta S, Tyagi J, Sharma A, Bal C, Snehlata, Malhotra A. Preliminary Experience with Yttrium-90-labelled Rituximab (Chimeric Anti CD-20 Antibody) in Patients with Relapsed and Refractory B Cell Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma. Curr Radiopharm. 2016;9(2):160–168. doi: 10.2174/1874471009999160625110400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nayak TK, Brechbiel MW. (86)Y based PET radiopharmaceuticals: radiochemistry and biological applications. Med Chem (Sharjah, United Arab Emirates) 2011;7(5):380–388. doi: 10.2174/157340611796799249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehlerding EB, Grodzinski P, Cai W, Liu CH. Big Potential from Small Agents: Nanoparticles for Imaging-Based Companion Diagnostics. ACS Nano. 2018;12:2106. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b07252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avila-Rodriguez MA, Nye JA, Nickles RJ. Production and separation of non-carrier-added 86Y from enriched 86Sr targets. Appl Radiat Isot. 2008;66(1):9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2007.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehlerding EB, Lacognata S, Jiang D, Ferreira CA, Goel S, Hernandez R, Jeffery JJ, Theuer CP, Cai W. Targeting angiogenesis for radioimmunotherapy with a 177Lu-labeled antibody. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45(1):123–131. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3793-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stabin MG, Sparks RB, Crowe E. OLINDA/EXM: The Second-Generation Personal Computer Software for Internal Dose Assessment in Nuclear Medicine. J Nucl Med. 2005;46(6):1023–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puranik AD, Kulkarni HR, Baum RP. Companion Diagnostics and Molecular Imaging. Cancer J. 2015;21(3):213–217. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopci E, Chiti A, Castellani MR, Pepe G, Antunovic L, Fanti S, Bombardieri E. Matched pairs dosimetry: 124I/131I metaiodobenzylguanidine and 124I/131I and 86Y/90Y antibodies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38(1):28. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1772-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duffy AG, Ulahannan SV, Cao L, Rahma OE, Makarova-Rusher OV, Kleiner DE, Fioravanti S, Walker M, Carey S, Yu Y, Venkatesan AM, Turkbey B, Choyke P, Trepel J, Bollen KC, Steinberg SM, Figg WD, Greten TF. A phase II study of TRC105 in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who have progressed on sorafenib. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2015;3(5):453–461. doi: 10.1177/2050640615583587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karzai FH, Apolo AB, Cao L, Madan RA, Adelberg DE, Parnes H, McLeod DG, Harold N, Peer C, Yu Y, Tomita Y, Lee M-J, Lee S, Trepel JB, Gulley JL, Figg WD, Dahut WL. A phase I study of TRC105 anti-endoglin (CD105) antibody in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. BJU International. 2015;116(4):546–555. doi: 10.1111/bju.12986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell GS, Gill RK, Boucher DL, Li C, Cherry SR. In vivo Cerenkov luminescence imaging: a new tool for molecular imaging. Philos Trans R Soc, A. 2011;369(1955):4605–4619. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2011.0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Husein B, Abdalla M, Trepte M, DeRemer DL, Somanath PR. Anti-angiogenic therapy for cancer: An update. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32(12):1095–1111. doi: 10.1002/phar.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson PM, LaBonte MJ, Lenz H-J. Assessing the in vivo efficacy of biologic antiangiogenic therapies. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1978-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rösch F, Herzog H, Qaim SM. The Beginning and Development of the Theranostic Approach in Nuclear Medicine, as Exemplified by the Radionuclide Pair (86)Y and (90)Y. Pharmaceuticals. 2017;10(2):56. doi: 10.3390/ph10020056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buchholz HG, Herzog H, Förster GJ, Reber H, Nickel O, Rösch F, Bartenstein P. PET imaging with yttrium-86: comparison of phantom measurements acquired with different PET scanners before and after applying background subtraction. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30(5):716–720. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-1112-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong H, Severin GW, Yang Y, Engle JW, Zhang Y, Barnhart TE, Liu G, Leigh BR, Nickles RJ, Cai W. Positron emission tomography imaging of CD105 expression with(89) Zr-Df-TRC105. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;39(1):138–148. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1930-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engle JW, Hong H, Zhang Y, Valdovinos HF, Myklejord DV, Barnhart TE, Theuer CP, Nickles RJ, Cai W. Positron Emission Tomography Imaging of Tumor Angiogenesis with a (66)Ga-Labeled Monoclonal Antibody. Mol Pharmaceutics. 2012;9(5):1441–1448. doi: 10.1021/mp300019c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong H, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Engle JW, Barnhart TE, Nickles RJ, Leigh BR, Cai W. Positron emission tomography imaging of CD105 expression during tumour angiogenesis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38(7):1335–1343. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1765-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maeda H. Toward a full understanding of the EPR effect in primary and metastatic tumors as well as issues related to its heterogeneity. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2015;91:3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maeda H, Nakamura H, Fang J. The EPR effect for macromolecular drug delivery to solid tumors: Improvement of tumor uptake, lowering of systemic toxicity, and distinct tumor imaging in vivo. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2013;65(1):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voegeli M, Rondeau S, Berardi Vilei S, Lerch E, Wannesson L, Pabst T, Rentschler J, Bargetzi M, Jost L, Ketterer N, Bischof Delaloye A, Ghielmini M. Y90-Ibritumomab tiuxetan (Y90-IT) and high-dose melphalan as conditioning regimen before autologous stem cell transplantation for elderly patients with lymphoma in relapse or resistant to chemotherapy: a feasibility trial (SAKK 37/05) Hematol Oncol. 2017;35(4):576–583. doi: 10.1002/hon.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rousseau C, Kraeber-Bodéré F, Barbet J, Chatal J-F. Pretargeted radioimmunotherapy: clinically more efficient than conventional radioimmunotherapy? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40(9):1373–1376. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2469-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van de Watering FCJ, Rijpkema M, Robillard M, Oyen WJG, Boerman OC. Pretargeted Imaging and Radioimmunotherapy of Cancer Using Antibodies and Bioorthogonal Chemistry. Front Med. 2014;1:44. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2014.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freise AC, Wu AM. In vivo Imaging with Antibodies and Engineered Fragments. Mol Immunol. 2015;67:142–152. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Formenti SC, Demaria S. Combining Radiotherapy and Cancer Immunotherapy: A Paradigm Shift. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2013;105(4):256–265. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.