Abstract

Introduction

Odontogenic infections are the most commonly encountered orofacial infections, which may spread into the adjacent anatomical spaces along the contiguous fascial planes, leading to involvement of multiple spaces which can progress to life-threatening situations.

Materials and Methods

A prospective study was carried out on 100 consecutive cases of odontogenic infections treated at our institute over a period of 18 months by surgical intervention and intravenous antibiotics. Morphologic study of the isolates and antibiotic sensitivity testing was performed.

Results

Caries was the most frequent dental disease (53.27%), and the mandibular first molar was the most frequently involved tooth (41.9%) associated with the etiology of odontogenic infections. A total of 158 spaces were involved in 100 patients. In subjects with single space odontogenic infections (n = 61), submandibular space was most commonly affected (44.26%) followed by buccal space (27%). In subjects with multiple space infections (n = 39), submandibular space (30.19%) was most frequently involved followed by buccal space (17.92%). In the aerobic group/microaerophilic group, 17 different species were isolated in a total of 102 aerobic isolates. A total of 18 species were identified in 65 anaerobic isolates sampled.

Conclusion

Amoxicillin possess antimicrobial activity against major pathogens in orofacial odontogenic infections, but β-lactamase production has restricted the effectiveness of amoxicillin against the resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus, Bacteroides, Prevotella and Porphyromonas. For the management of orofacial infections, the use of amoxicillin/clavulanate and clindamycin is recommended because of stability against β-lactamases.

Keywords: Odontogenic infection, Antibiotic sensitivity, Drug resistance, Fascial spaces

Introduction

Orofacial odontogenic infections are mixed aerobic–anaerobic infections, and the bacteriology often excogitates the existence of commensal oral flora [1–3].

The etiology is usually a presence of decayed or non-vital teeth, postoperative infections, periodontal disease and pericoronitis [4]. If dismissed, they generally spread into the contiguous fascial spaces and may lead to adverse life-threatening consequences [5]. This mandates early recognition and prompt treatment; drainage must be established where possible [3]. Most patients recover completely after precise surgical treatment and the removal of the odontogenic focus in combination with administration of appropriate adjunctive antibiotics [6].

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the incidence of anatomical space involved in odontogenic space infections and determine the bacteriological profile and antibiotic sensitivity of the aerobically and anaerobically cultured isolates.

Material and Methods

The present study offers a prospective analysis of 100 consecutive cases of odontogenic infections treated in Department of Oral and Maxillofacial surgery, Government college of Dentistry, Indore, India, over a period of 18 months from May 2013 to October 2014. The study was carried out with the following objectives:

To assess the incidence of anatomical space involved in odontogenic infections.

To determine the predominant pathogenic organism among the isolates obtained from odontogenic orofacial infections and to analyze the antibiograms for any particular trend in antibiotic sensitivity patterns in the study population and propose a suitable antibiotic for empiric therapy in patients with orofacial odontogenic infections.

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, and informed consent was taken from the patients to participate in the study. Patients sustaining severe odontogenic infections, who required hospitalization, intravenous antibiotic therapy and incision and drainage for treatment, were included in this study. The usual criteria for hospital admission in this type of pathology included: trismus (defined as an oral aperture of less than 40 mm), dysphagia, odynophagia, dyspnea, high fever (over 38 °C). Patients with draining odontogenic abscess (intraoral/extraoral), with orofacial abscess of non-odontogenic origin or having a coexisting systemic disease were not considered for this study.

A detailed preoperative medical history of all patients was recorded. Patients were diagnosed on the basis of clinical examination and radiographic interpretation. Routine hematologic investigations were done. Periapical and panoramic X-rays were done to determine the odontogenic focus.

All patients underwent surgical incision (either through extraoral or intraoral approach) and drainage and received intravenous antibiotics. The first-line treatment consisted of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid administered as 1000/200 mg (1.2 g) i.v twice daily and metronidazole 500 mg/100 ml i.v infusion thrice daily.

Second-line treatment was intravenous administration of clindamycin 600 mg 8 hourly and was used in patients who failed to improve in 48 h after receiving in-hospital treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. The causative tooth was removed whenever possible. The routine treatment also consisted of the administration of analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs. The evaluated parameters included gender, age, site of space infection, dental focus of infection, duration of hospitalization, the antibiotic administered, microbiologic spectrum and antibiograms.

Specimen for culture and sensitivity tests was procured by aspiration. Extraoral approach was preferred to eliminate contamination with oral flora. But in cases where extraoral approach was not possible, specimen was collected intraorally after proper preparation of site. The specimens were immediately transported in thioglycollate broth to the department of microbiology and were processed by smear studies of gram staining, aerobic culture and anaerobic culture.

Results

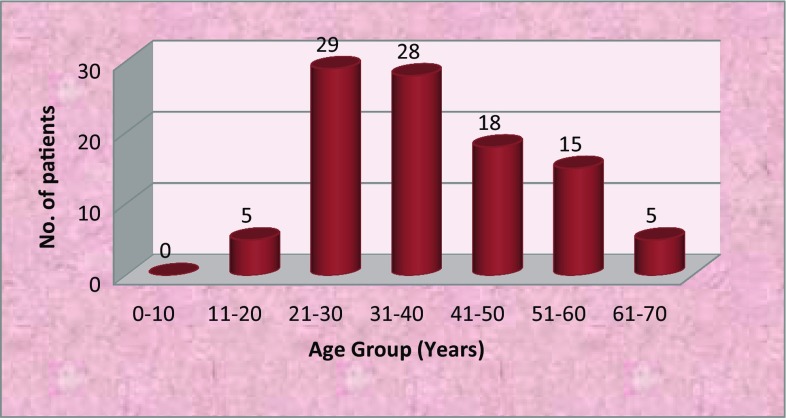

Odontogenic infections were predominantly seen in males (71%) with a male-to-female ration of 2.45:1. The age of patients ranged from 15–65 years with mean age occurrence being 37.35 years. The most commonly affected age group was 21–30 years (29%) followed by 31–40 years (28%) (Fig. 1). The most common causes of odontogenic infection were caries (65%), pericoronitis (36%) and periodontitis (21%). The most frequently involved teeth were mandibular 1st molar (41.9%) followed by mandibular 2nd (16.1%) and 3rd molars (15.3%) (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of patients according to age

Table 1.

Distribution of patients according to the frequency of the tooth causing odontogenic infections (N = 124)

| S. No. | Tooth | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lower 3rd molar | 19 | 15.3 |

| 2 | Lower 2nd molar | 20 | 16.1 |

| 3 | Lower 1st molar | 52 | 41.9 |

| 4 | Lower 1st premolar | 10 | 8.0 |

| 5 | Lower 2nd premolar | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | Lower canine | 1 | 0.08 |

| 7 | Lower lateral incisor | 2 | 1.6 |

| 8 | Lower central incisor | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | Upper 3rd molar | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | Upper 2nd molar | 1 | 0.8 |

| 11 | Upper 1st molar | 10 | 8.0 |

| 12 | Upper 2nd premolar | 5 | 4.0 |

| 13 | Upper 1st premolar | 2 | 1.6 |

| 14 | Upper canine | 2 | 1.6 |

| 15 | Upper lateral incisor | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | Upper central incisor | 0 | 0 |

In the study sample of 100 patients, 61% presented with involvement of single odontogenic space, and 39% presented with involvement of multiple odontogenic spaces, and a total of 158 spaces were involved. In patients with odontogenic infection of single space, submandibular space was most commonly affected (44.26%) followed by buccal (27%) and pterygomandibular spaces (9.83%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of patients according to the space involved in single space odontogenic infections (N = 61)

| Involved odontogenic space | No. of patients(n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Submandibular | 27 | 44.26 |

| Buccal | 17 | 27 |

| Canine | 4 | 6.55 |

| Submental | 2 | 3.27 |

| Massetric | 3 | 4.91 |

| Pterygomandibular | 6 | 9.83 |

| Sublingual | 2 | 3.27 |

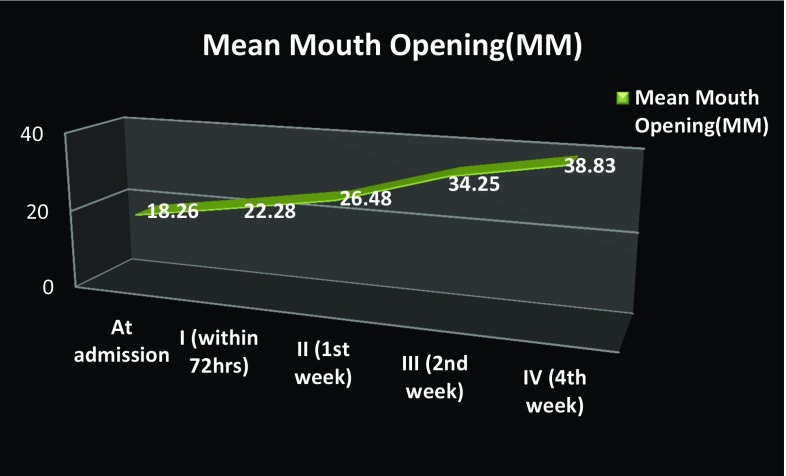

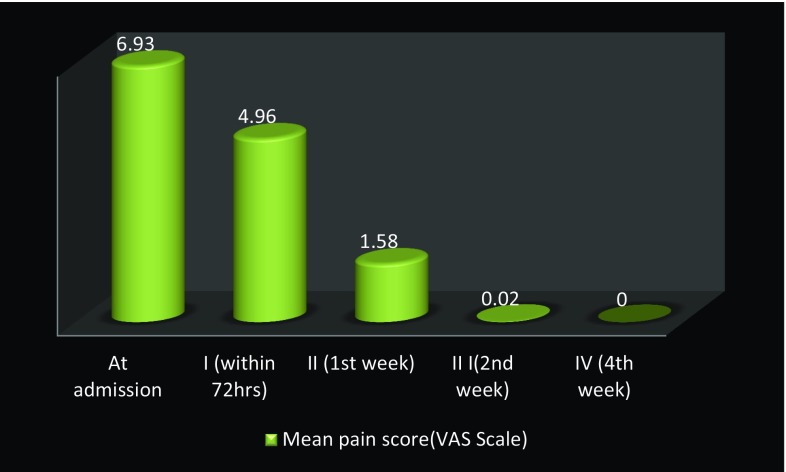

Odontogenic infections involving multiple spaces were seen in 39 patients, and a total of 106 spaces were involved (Table 3). The most commonly seen combinations of spaces involved in odontogenic infections were submandibular + submental spaces in 11 patients (28.21%) followed by bilateral submandibular + submental + sublingual spaces seen in 7 patients (17.95%) and buccal + temporal spaces in 6 patients (15.38%). Ninety-four patients (94%) were treated under local anesthesia, and 6 patients (6%) were treated under conscious sedation with local anesthesia. Forty-nine patients (49%) were operated via extraoral approach, 39 patients (39%) were operated via intraoral approach, and 12 patients (12%) were operated via combined intraoral and extraoral approach. Pus at incision and drainage was present in 98 cases (98%). Range of length of hospital stay was 3–16 days with a mean of 5.9 days. The mean duration of intravenous administration of antibiotics was 3.5 days with a range of 2–11 days, followed by oral administration for a week. The mean preoperative mouth opening was 18.26 mm, and progressive increase in the mouth opening was seen postoperatively with a mean postoperative mouth opening value of 22.28 mm at 72 h and 38.83 mm after 4 weeks (Fig. 2). There was significant decrease in pain from follow-up I to follow-up III, and no complaint about pain was noted in follow-up IV in any of the patients (Fig. 3). The mean leukocyte count of the patients at time of admission was 13.90 × 109 per liter. Progressive decrease in the leukocyte count was seen postoperatively with a mean post-value of 10.74 ± 6.05 × 109 per liter after 72 h, 9.44 × 109 per liter after 1 week and 9.34 × 109 per liter after 4 weeks.

Table 3.

Distribution of patients according to the space involved in multiple space odontogenic infections (total spaces involved = 106)

| Involved space | No. of patients | Percentage | Total spaces involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Submandibular | 25 | 30.19 | 32 |

| Submental | 18 | 16.98 | 18 |

| Buccal | 19 | 17.92 | 19 |

| Sublingual | 7 | 6.60 | 14 |

| Canine | 2 | 1.89 | 2 |

| Submassetric | 3 | 2.83 | 3 |

| Pterygomandibular | 6 | 5.66 | 6 |

| Lateral Pharyngeal | 6 | 5.66 | 6 |

| Temporal | 6 | 5.66 | 6 |

Fig. 2.

Improvement in mean mouth opening (in mm) from admission to postoperative follow-ups

Fig. 3.

Improvement in pain score from admission to postoperative follow-ups

A total of 167 isolates were obtained from 100 study samples. Thirty-five different strains of microorganisms were isolated from the study group with an average of 1.7 isolates per sample (Table 4).

Table 4.

Organisms isolated from the study samples

| Aerobic isolates | Anaerobic isolates | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. No | Species | Frequency | Percentage | S. No | Species | Frequency | Percentage |

| 1. | Staphylococcus aureus | 20 | 19.60 | 1 | Fusobacterium nucleatum | 11 | 16.92 |

| 2. | E.coli | 5 | 4.90 | 2 | Prevotella | 7 | 10.77 |

| 3. | St. Viridians | 48 | 47.05 | 3 | Actinomyces israelli | 2 | 3.07 |

| 4. | Pseudomonas | 4 | 3.92 | 4 | Actinomyces israelli | 2 | 3.07 |

| 5. | Staphylococcus sp. | 2 | 1.96 | 5 | Bacteroides melaninogenicus | 3 | 4.62 |

| 6. | Actinomyces | 2 | 1.96 | 6 | Bacteroides sp. | 6 | 9.23 |

| 7. | Streptococcus Mutans | 4 | 3.92 | 7 | Bacillus sp. | 3 | 4.62 |

| 8. | Streptococci epidermidis | 4 | 3.92 | 8 | Bacteroides fragilis | 2 | 3.07 |

| 9. | Enterococcus faecalis | 8 | 7.84 | 9 | Peptostreptococcus | 5 | 7.69 |

| 10. | Streptococcus Milleri | 4 | 3.92 | 10 | Haemophilus influenza | 2 | 3.07 |

| 11. | Klebsiella | 5 | 4.90 | 11 | Veillonella | 2 | 3.07 |

| 12. | Campylobacter | 1 | 0.98 | 12 | Porphyromonas | 4 | 6.15 |

| 13. | Neisseria | 4 | 3.92 | 13 | Gemella | 4 | 6.15 |

| 14. | Corynebacterium | 2 | 1.96 | 14 | Eubacterium | 4 | 6.15 |

| 15. | Micrococcus | 1 | 0.98 | 15 | Propionibacterium | 3 | 4.62 |

| 16. | Haemophilus | 1 | 0.98 | 16 | Capnocytophaga | 3 | 4.62 |

| 17. | Unidentified | 3 | 2.97 | 17 | Eikenella corrodens | 1 | 1.54 |

| 18 | Peptococcus | 1 | 1.54 | ||||

| Total | 102 | Total | 65 | 16.92 | |||

In the aerobic group/microaerophilic group, a total 17 different species were isolated. Streptococcus species was the most frequent, and viridians streptococci was the predominant isolated organism (n = 48) followed by Staphylococcus aureus organism (n = 20) and Enterococcus feacalis (n = 8).

A total of 18 different species of anaerobic organisms (n = 65) were isolated. In this group, the most numerous isolates were of Fusobacterium nucleatum in 16.92% (n = 11) cases, followed by Prevotella species in 10.77% cases (n = 7) (Table 4). Negative cultures were reported in 13% cases, pure cultures were isolated from 12% cases, and more than one isolate was reported in 75% cases (two isolates were reported in 70% cases, and three isolates were reported in 5% cases).

Antibiotics evaluated for sensitivities were penicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, clindamycin, ciprofloxacin, cefotaxime and metronidazole. Penicillin showed excellent (97.05%) activity against the aerobic isolates. The overall activity of clindamycin against aerobic isolates was excellent (99.01%), and resistance against clindamycin was noted in one case of viridans streptococcus isolate. Cefotaxime showed significant (91.18%) activity against the aerobic isolates. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid had excellent (100%) activity against all the aerobic isolates. The activity of ciprofloxacin was good against aerobes, and the only organism that exhibited considerable resistance against ciprofloxacin was S. aureus (12.5%). The inactivity of metronidazole in aerobic isolates is a known fact (Table 5).

Table 5.

Sensitivity of different antibiotics against aerobic isolates

| Organism | Penicillin | Clindamycin | Cefotaxime | Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid | Ciprofloxacin | Metronidazole |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Viridians streptococci

(n = 48) |

48/48 (100%) |

47/48 (97.92%) |

44/48 (91.66%) |

48/48 (100%) |

48/48 (100%) |

0/48 (0%) |

|

Staphylococcus aureus

(n = 20) |

19/20 (95%) |

20/20 (100%) |

19/20 (95%) |

20/20% (100%) |

19/20 (95%) |

0/20 (0%) |

|

Enterococcus feacalis

(n = 8) |

6/8 (75%) |

8/8 (100%) |

6/8 (75%) |

8/8 (100%) |

7/8 (87.5%) |

0/8 (0%) |

|

Streptococcus pneumoniae

(n = 5) |

5/5 (100%) |

5/5 (100%) |

5/5 (100%) |

5/5 (100%) |

5/5 (100%) |

0/5 (0%) |

|

Staphylococcus

epidermidis (n = 4) |

4/4 (100%) |

4/4 (100%) |

4/4 (100%) |

4/4 (100%) |

4/4 (100%) |

0/4 (0%) |

| Miscellaneous (n = 17) |

17/17 (100%) |

17/17 (100%) |

15/17 (88.23%) |

17/17 (100%) |

15/17 (88.23%) |

0/17 (0%) |

| Total | 99/102 97.05% |

101/102 (99.01%) |

93/102 (91.18%) |

102/102 (100%) |

98/102 (96.08%) |

0/102 (0%) |

Metronidazole had excellent activity (100%) against all the anaerobic isolates. ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and clindamycin also presented with good activity (90.77, 90.77 and 86.15%, respectively), whereas penicillin had poor activity (24.61%) against all the anaerobic isolates (Table 6).

Table 6.

Sensitivity of different antibiotics against anaerobic isolates

| Organism | Penicillin | Clindamycin | Cefotaxime | Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid | Ciprofloxacin | Metronidazole |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fusobacterium nucleatum

(n = 11) |

0/11 (0%) |

9/11 (36.36%) |

7/11 (63.63%) |

11/11 (100%) |

11/11 (100%) |

11/11 (100%) |

|

Prevotella

(n = 8) |

0/8 (0%) |

6/8 (0%) |

5/8 (62.5%) |

8/8 (100%) |

8/8 (100%) |

8/8 (100%) |

| Miscellaneous (n = 46) |

16/46 (34.78%) |

41/46 (39.13%) |

42/46 (100%) |

40/46 (86.95%) |

40/46 (100%) |

46/46 (100%) |

| Total | 16/65 (24.61%) |

56/65 (86.15%) |

54/65 (83.07%) |

59/65 (90.77%) |

59/65 (90.77%) |

15/15 (100%) |

Discussion

Odontogenic space infections are mixed aerobic–anaerobic infections. Odontogenic infection occurs due to complex interaction of an array of microorganisms which are non-infective in pure cultures. This connotes that an infectious milieu is created by an interdependent and synergistic metabolism between microorganisms [7, 8].

Out of a total of 100 subjects enrolled in this study, 71 were males and 31 were females. Male preponderance evident in this study was in accordance with the other studies in the literature [5, 8–10]. The age of the patients ranged from 15 to 65 years with a mean age of 37.35 years. Similar to study by Singh et al. [11], the mandibular first molars were involved in maximum number of cases in this study population (n = 52), unlike the other studies that have reported the most frequent involvement of mandibular third molars [7, 12]. This might be because it is the first permanent tooth to erupt in the oral cavity and is apparently most susceptible to caries. The mandibular third molars were frequently associated with masticator space infections with or without buccal or submandibular space infection (multiple space infections) in this study.

The occurrence of odontogenic infection was attributed to the presence of carious teeth in 65 patients (53.27%), pericoronitis in 36 patients (29.51%) and periodontitis in 21 patients (17.2%) which correlates with the study of Flynn et al. who reported caries as the most frequent dental disease leading to severe odontogenic infection (65%), followed by pericoronitis (22%) and periodontal disease (22%) [9].

The most common space involved in single odontogenic space infections was submandibular followed by buccal and pterygomandibular which correlates with the other studies in the literature [6, 11, 13, 14]. For multiple space infections, the most common involvement of submandibular space (35.6%) followed by lateral pharyngeal space (17.4%) [12], and submandibular space 40 (28.2%) followed by submental space 21 (14.8%) [14] have been reported. However, in this study submandibular (30.19%) followed by buccal (17.92%) space was most frequently involved in multiple space infections, which was consistent with the study by Haug et al. [15].

Dysphagia was reported in 29%, trismus (mo < 40 mm) in 41%, initial raised temperature in 40% and dyspnoea by 7% patients, which was similar to the study by Mathew et al. who reported trismus in 50.4%, fever in 42.3%, dysphagia in 40.1% and dyspnea in 17.5% patients [5]. Flynn et al. demonstrated dysphagia and dyspnea in 78 and 73% cases, respectively, which was highly suggestive of severe odontogenic space infection [9].

The fatal medical complications that can occur due to spread of odontogenic space infections are airway obstruction either at presentation or secondary to postsurgical edema [16], septicemia [17], necrotizing fasciitis [18], spread to the cavernous sinus, the orbit and the mediastinum [17]. The rare complications that have been reported are mandibular osteomyelitis [19], disseminated intravascular coagulation, acute respiratory distress syndrome [17], bacterial endocarditis, mediastinitis, intracranial complications, i.e., meningitis, subdural empyema and cerebral vasculitis [20] and Lemierre’s syndrome [21].

No such complication was evident in this study except for occurrence of necrotizing fasciitis in one patient who was meticulously managed with surgical debridement and regular dressings under antibiotic coverage.

Prompt intervention is mandatory with surgical decompression of the swelling by performing incision and drainage. Debridement of the necrotic tissue, elimination of dead space during the cellulitic phase, and removal of the odontogenic focus should be done. Empiric antibiotic therapy is instituted till the culture and antibiotic sensitivity testing results are received, followed by antibiotic substitution if required [16, 22, 23].

The literature suggests that the individual species isolated from exudates in experimental animals are non-infective in pure cultures, but infectious milieu is rendered through bacterial synergism between the indigenous oral flora [24]. The bacteriologic spectrum of odontogenic space infection was found to be polymicrobial consisting of aerobes, microaerophilics and anaerobes.

Consistent with the other studies, the aerobic species outnumbered the anaerobic species [6, 12], and the most prevalent bacteria isolated were Gram-positive cocci followed by Gram-negative rods [12, 14]. In contrast, many studies have reported that anaerobes play a major role in etiology of odontogenic infections [3, 11, 25]. The literature articulates that the predominant species are aerobes when swabbing is used to obtain the pus specimen, and aspiration yields majority of anaerobic rods in culture [6, 26]. Contrarily there was a predominance of aerobes in this study even though the specimen was procured via aspiration technique.

An average of 1.7 isolates per specimen was reported from 100 patients. This finding was lesser than other studies which have shown an average of 2.6, 3.0 and 3.8 isolates per sample (obtained by aspiration), respectively [14, 25, 27].

Anaerobic strains require prolonged culture time of usually up to 7–10 days and are more sensitive to milieu changes during transport [6, 26]. Since microbial culture and sensitivity results were promptly required for initiating/modifying the antibiotic therapy during the course of treatment, many anaerobes may not have survived the procedure of aspiration, transportation and culture, leading to a low average of 1.7 isolates per sample.

To assess the severity of orofacial infections, WBC count is a parameter of minor significance, but it is an important predictor to assess the improvement in patient’s status in response to treatment [12, 25]. In every case, progressive decrease in leukocyte count was seen after initiation of aggressive management suggesting the patient’s positive response to therapy.

Penicillin showed excellent activity against all aerobic microorganisms (97.05%). However, the activity of penicillin was found to be less against anaerobic isolates (24.61%). Penicillin resistance has been reported to occur primarily through the production of beta lactamase [25, 28]. Flyn et al. reported penicillin resistant organisms in 19% of all strains isolated in their study [22]. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid had excellent activity against both the aerobic isolates (100%) and the anaerobic isolates (90.76%), making it superior in activity than amoxicillin alone. Addition of clavulanic acid increases the spectrum to staphylococcus and other anaerobes by conferring beta lactamase resistance. Clindamycin also had high activity against both aerobic and anaerobic microorganisms (99.01 and 86.15%). The overall incidence of resistance against amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, clindamycin and penicillin was 3.59, 5.98 and 31.14%, respectively. In accordance with the literature, the study favors that clindamycin can serve as an effective alternate in cases not responding to amoxicillin [25, 29].

Clindamycin possess excellent activity against aerobic Gram-positive cocci, such as Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus species and most anaerobes, including penicillin resistant strains of Bacteroides, Prevotella and Porphyromonas [28]. A recent study by Tancawan reported that the efficacy and tolerability of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid were comparable to clindamycin in achieving clinical success for the treatment of odontogenic infections [30].

Conclusion

Prompt recognition and meticulous treatment of odontogenic infections by surgical drainage and adjunctive antibiotic therapy are necessary because of the risk of spread along multiple contiguous fascial spaces. Inadvertence may result in disastrous outcomes due to the proximity to the central nervous system and critical respiratory passages. The combination of amoxicillin with clavulanic acid is the first-line antibacterial of choice, effective against majority of microorganisms responsible for odontogenic infections. Alternatively, the use of clindamycin if required renders similar results because of its broad spectrum of activity and resistance to ß-lactamase degradation.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

The study was approved by institutional review board. Informed written consent was obtained from the patients for participation in the study.

References

- 1.Hostetter MK. Handicaps to host defense. Effects of hyperglycemia on C3 and Candida albicans. Diabetes. 1990;39:271–275. doi: 10.2337/diab.39.3.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joshi N, Caputo GM, Weitekamp MR, et al. Infections in patients with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1999;16(341):1906–1912. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912163412507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill Y, Scully C. Orofacial odontogenic infections: review of microbiology and current treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;70(2):155–158. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90109-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ylijoki S, Suuronen R, Jousimies-Somer H, Meurman JH, Lindqvist C. Differences between patients with or without the need for intensive care due to severe odontogenic infections. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59(8):867–872. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.25017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathew GC, Ranganathan LK, Gandhi S, Jacob ME, Singh I, Solanki M, Bither S. Odontogenic maxillofacial space infections at a tertiary care center in North India: a five-year retrospective study. Int J Infect Dis. 2012;16(4):e296–e302. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poeschl PW, Spusta L, Russmueller G, Seemann R, Hirschl A, Poeschl E, Klug C, Ewers R. Antibiotic susceptibility and resistance of the odontogenic microbiological spectrum and its clinical impact on severe deep space head and neck infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;110(2):151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moenning JE, Nelson CL, Kohler RB. The microbiology and chemotherapy of odontogenic infections. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47(9):976–985. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(89)90383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fating NS, Saikrishna D, Vijay Kumar GS, Shetty SK, Raghavendra Rao M. Detection of bacterial flora in orofacial space infections and their antibiotic sensitivity profile. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2014;13(4):525–532. doi: 10.1007/s12663-013-0575-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flynn TR, Shanti RM, Levi MH, Adamo AK, Kraut RA, Trieger N. Severe odontogenic infections, part 1: prospective report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1093–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang TT, Tseng FY, Liu TC, Hsu CJ, Chen YS. Deep neck infection in diabetic patients: comparison of clinical picture and outcomes with nondiabeticpatients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132(6):943–947. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh M, Kambalimath DH, Gupta KC. Management of odontogenic space infection with microbiology study. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2014;13(2):133–139. doi: 10.1007/s12663-012-0463-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.William Storoe, Richard Haug. The changing face of odontogenic infections. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:739–748. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.24285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Opitz D, Camerer C, Camerer DM, Raguse JD, Menneking H, Hoffmeister B, Adolphs N. Incidence and management of severe odontogenic infections—a retrospective analysis from 2004 to 2011. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015;43(2):285–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rega AJ, Aziz SR, Ziccardi VB. Microbiology and antibiotic sensitivities of head and neck space infections of odontogenic origin. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1377–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haug RH, Hoffman MJ, Indresano AT. An epidemiologic and anatomic survey of odontogenic infections. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49(9):976–980. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90063-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jundt JS, Gutta R. Characteristics and cost impact of severe odontogenic infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114:558–566. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2011.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bali RK, Sharma P, Gaba S, Kaur A, Ghanghas P. A review of complications of odontogenic infections. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2015;6(2):136–143. doi: 10.4103/0975-5950.183867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chunduri NS, Madasu K, Tammannavar PS, Pushpalatha C. Necrotising fasciitis of odontogenic origin. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2012008506. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-008506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gams K, Freeman P. Temporomandibular joint septic arthritis and mandibular osteomyelitis arising from an odontogenic infection: a case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;74(4):754–763. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cariati P, Cabello-Serrano A, Monsalve-Iglesias F, Roman-Ramos M, Garcia-Medina B. Meningitis and subdural empyema as complication of pterygomandibular space abscess upon tooth extraction. J Clin Exp Dent. 2016;8(4):e469–e472. doi: 10.4317/jced.52916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noy D, Rachmiel A, Levy-Faber D, Emodi O. Lemierre’s syndrome from odontogenic infection: review of the literature and case description. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2015;5(2):219–225. doi: 10.4103/2231-0746.175746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flynn TR. What are the antibiotics of choice for odontogenic infections, and how long should the treatment course last? Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2011;23(4):519–536. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishnan V, Johnson JV, Helfrick JF. Management of maxillofacial infections: a review of 50 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51(8):868–873. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(10)80105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aderhold L, Knothe H, Frenkel G. The bacteriology of dentogenous pyogenic infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1981;52(6):583–587. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(81)90072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heimdahl A, von Konow L, Satoh T, et al. Clinical appearance of orofacial infections of odontogenic origin in relation to microbiological findings. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;22(2):299–302. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.2.299-302.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakaguchi M, Sato S, Ishigama T, Katsuno S, Taguchi K. Characteristics and management of deep neck infections. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;26:131–134. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80835-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sabiston CB, Grigsby WR, Segerstrom N. Bacterial study of pyogenic infections of dental origin. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1976;41(4):430–435. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(76)90269-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinder SA, Holt SC, Korman KS. Penicillin resistance in subgingival microbiota associated with adult periodontitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;23(6):1127–1133. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.6.1127-1133.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Von Konow L, Köndell PA, Nord CE, Heimdahl A. Clindamycin versus phenoxymethylpenicillin in the treatment of acute orofacial infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;11(12):1129–1135. doi: 10.1007/BF01961131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tancawan AL, Pato MN, Abidin KZ, Mohd Asari AS, Thong TX, Kochhar P, et al. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid for the treatment of odontogenic infections: a randomised study comparing efficacy and tolerability versus clindamycin. Int J Dent. 2015;2015:472470. doi: 10.1155/2015/472470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]